- Search Menu

- Themed Collections

- Editor's Choice

- Ilona Kickbusch Award

- Supplements

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Online

- Open Access Option

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Health Promotion International

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, supplementary material.

- < Previous

Promoting lung cancer awareness, help-seeking and early detection: a systematic review of interventions

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Mohamad M Saab, Serena FitzGerald, Brendan Noonan, Caroline Kilty, Abigail Collins, Áine Lyng, Una Kennedy, Maidy O’Brien, Josephine Hegarty, Promoting lung cancer awareness, help-seeking and early detection: a systematic review of interventions, Health Promotion International , Volume 36, Issue 6, December 2021, Pages 1656–1671, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daab016

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Lung cancer (LC) is the leading cause of cancer death. Barriers to the early presentation for LC include lack of symptom awareness, symptom misappraisal, poor relationship with doctors and lack of access to healthcare services. Addressing such barriers can help detect LC early. This systematic review describes the effect of recent interventions to improve LC awareness, help-seeking and early detection. This review was guided by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Electronic databases MEDLINE, CINAHL, ERIC, APA PsycARTICLES, APA PsycInfo and Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection were searched. Sixteen studies were included. Knowledge of LC was successfully promoted in most studies using educational sessions and campaigns. LC screening uptake varied with most studies successfully reducing decision conflicts using decision aids. Large campaigns, including UK-based campaign ‘Be Clear on Cancer’, were instrumental in enhancing LC awareness, promoting help-seeking and yielding an increase in chest X-rays and a decrease in the number of individuals diagnosed with advanced LC. Multimodal public health interventions, such as educational campaigns are best suited to raise awareness, reduce barriers to help-seeking and help detect LC early. Future interventions ought to incorporate targeted information using educational resources, face-to-face counselling and video- and web-based decision aids.

Lung cancer (LC) is the leading cause of cancer incidence and mortality in men and women globally, with 2.1 million new cases (11.6% of the total cancer cases) and 1.8 million deaths (18.4% of the total cancer deaths) in the year 2018 alone ( Bray et al. , 2018 ). More than half of LC cases (53%) are diagnosed among men and women aged 55–74 years (median age = 70 years) ( Torre et al. , 2016 ). In contrast to the increase in survival rates for most cancers, LC is typically diagnosed at advanced stages with a five‐year survival rate of 5% ( Siegel et al. , 2018 ).

Screening individuals at risk for LC with low dose computed tomography (LDCT) has been shown to reduce LC mortality by up to 20% ( National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, 2011 ; Marcus et al. , 2016 ). The European Union stressed the importance of starting LC screening using LDCT throughout Europe ( Oudkerk et al. , 2017 ). However, to date, very few countries possess screening programs for LC ( Siegel et al. , 2018 ), and the uptake of LC screening in countries like the United States of America (USA) remains low, with only 4% of 6.8 million eligible individuals reporting having undergone LDCT ( Jemal and Fedewa, 2017 ). This highlights the importance of raising awareness of LC, supporting at-risk individuals in making a decision regarding LC screening and promoting early presentation for symptoms indicative of LC.

A persistent cough, a change in a pre-existing cough, and shortness of breath are common symptoms of early-stage LC ( Chowienczyk et al. , 2020 ). Haemoptysis remains the strongest symptom predictor of LC, yet it occurs in only a fifth of patients ( Walter et al. , 2015 ). Patients with LC can also be asymptomatic until systemic symptoms, such as unexplained weight loss and fatigue occur, signalling advanced disease ( American Cancer Society, 2019 ). Therefore, the symptom signature of LC is considered to be broad ( Koo et al. , 2018 ) in comparison to cancers that have a narrow symptom signature with single identifiable symptoms, such as breast ( O'Mahony et al. , 2013 ) and testicular ( Saab et al. , 2017a ) cancers. This may lead to delay in early presentation and LC diagnosis ( Holmberg et al. , 2010 ).

Early help-seeking for symptoms indicative of LC is key for timely and early diagnosis and improved survivorship. However, patients diagnosed with LC experience, on average, a 6-month delay between symptom onset and initiation of treatment ( Ellis and Vandermeer, 2011 ). This is known to have detrimental effects on early diagnosis, quality of life, cost of healthcare, and patients’ eligibility for curative treatment ( Walter et al. , 2015 ; World Health Organisation, 2020 ). Several barriers to help-seeking and early detection of LC exist, such as lack of symptom awareness, poor relationship with physicians and lack of healthcare access ( Carter‐Harris, 2015 ; Koo et al. , 2018 ; Cassim et al. , 2019 ; Cunningham et al. , 2019 ). Symptom misappraisal is another key contributor to help-seeking delay, especially in the presence of risk factors like smoking ( Smith et al. , 2016 ) and comorbidities, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) ( Cunningham et al. , 2019 ). For instance, a survey of 2042 participants found that being a smoker was associated with a reduced likelihood of help-seeking for symptoms indicative of LC, potentially due to pre-existing respiratory symptoms associated with chronic smoking ( Smith et al. , 2016 ). Similarly, in their qualitative study, Cunningham et al. (2019) found that individuals with COPD attributed changes in their respiratory symptoms to their COPD and failed to mention LC, despite having a significantly greater risk for LC. LC stigma also impacts negatively on help-seeking for LC ‘alarm’ symptoms. Indeed, a survey of 93 symptomatic individuals found that higher levels of perceived LC stigma were associated with a median waiting time of 41 days prior to seeking medical help for symptoms of concern ( Carter‐Harris, 2015 ). Therefore, raising awareness and promoting early presentation for symptoms indicative of LC can help detect LC early and improve survival.

The international literature has highlighted the importance of interventions that target awareness, symptom evaluation and early help-seeking for LC ( Dlamini et al. , 2019 ). For example, a national campaign in the UK entitled ‘Be Clear on Cancer’ resulted in a significant increase in LC awareness, respiratory consultations, number of physician-prescribed chest X-rays and CT scans, and number of LC cases diagnosed at early stages ( Ironmonger et al. , 2015 ). Interventions often vary in terms of modalities, intended mechanisms, theoretical basis and target area/groups. This systematic review aims to describe the effect of recent interventions to improve (i) knowledge and/or awareness of LC; (ii) help-seeking intentions and/or behaviours for LC and (iii) early detection of LC.

This systematic review was guided by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions ( Higgins et al. , 2019 ) and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses checklist ( Moher et al. , 2009 ).

Eligibility criteria

The review eligibility criteria were predetermined using the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes) framework ( Moher et al. , 2009 ). Population: conducted among individuals of any age including at-risk populations; Intervention: included any intervention, programme, or campaign; Comparison: incorporated within- or between-group comparison; and Outcomes: reported on at least one of the review outcomes (i.e. knowledge/awareness of LC, help-seeking intentions/behaviours for LC and/or early detection of LC). Studies were excluded if they included patients with LC, used LC screening as the intervention, did not incorporate a comparator, and used any nonexperimental design.

Search strategy

A search was conducted using the electronic databases MEDLINE, CINAHL, ERIC, APA PsycARTICLES, APA PsycInfo and Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection. Keywords were truncated and combined using Boolean operators ‘OR’ and ‘AND’ and the proximity indicator ‘N.’ The following keywords were searched on title or abstract: (lung* OR pulmo*) N3 (cancer* OR neoplas* OR malignan* OR tumo*) AND (know* OR aware* OR detect* OR help-seek*) AND (interven* OR program* OR campaign* OR trial* OR experiment* OR educat*).

The search was conducted on 15 January 2020 and, for pragmatic reasons, was limited to studies published in English between January 2015 and January 2020. Of note, there is no gold standard for limiting the search by year of publication, though studies published within a 10-year timeframe are broadly considered to be recent ( Wilhelm and Kaunelis, 2005 ). However, knowledge decay is common in public health interventions and is one of the reasons researchers frequently develop and refine health promotion interventions, whilst older interventions and campaigns become increasingly obsolete over time ( Nimmons et al ., 2017 ; Saab et al ., 2018 ). Therefore, it had been agreed a priori to limit the current search to evidence published within a five-year timeframe in order to source and synthesize the most up-to-date evidence relating to the latest interventions and educational LC campaigns.

Study selection

Records were transferred to Covidence, an online software used to produce systematic reviews of interventions ( The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020 ). Titles and abstracts were screened, and irrelevant records were excluded. The full text of potentially eligible records was then screened and reasons for exclusion were recorded. Title, abstract and full-text screenings were conducted in pairs. For a screening decision to be made, each record was screened twice by two independent reviewers. Screening conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data were extracted using a standardized data extraction table ( Supplementary Table 1S ) as follows: author(s); year; country; aim(s); design; theoretical underpinning; sample; setting; relevant outcomes; intervention; procedures; instruments; follow-up times and findings. Data extraction was conducted by one reviewer. Each extracted study was then cross-checked by the rest of the review team.

A meta-analysis with summary measures of intervention effect requires that the included studies be sufficiently homogenous ( Higgins et al. , 2019 ). Therefore, given the heterogeneity of the studies in terms of design, outcomes and outcome measures, a meta-analysis was not plausible. Instead, a narrative synthesis of study findings was conducted, and findings were synthesized and discussed according to the review aims under the headings (i) knowledge and awareness, (ii) help-seeking and (iii) early detection.

Quality and level of evidence

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) helps appraise the methodological quality of five study categories: qualitative studies, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), nonrandomized studies, quantitative descriptive studies and mixed methods studies ( Hong et al. , 2018 ). In line with the current review aim and eligibility criteria, the methodological quality of three study categories was appraised, namely RCTs (seven quality appraisal items), nonrandomized studies (seven quality appraisal items) and mixed methods studies (17 quality appraisal items). Each of the quality appraisal items was judged on a ‘Yes’, ‘No’ and ‘Can’t tell’ basis. The clarity of research questions and the use of appropriate data collection methods to address those were assessed for all study categories. For RCTs and nonrandomized studies, sample representativeness and similarities between participant groups at baseline were assessed. Other items related to blinding the outcome assessor, reporting of complete outcome data, accounting for confounders, and ensuring that interventions have been administered as intended. For mixed methods studies, additional items assessed the integration of quantitative and qualitative methods and explored whether divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results have been adequately addressed.

The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network’s ( Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2019 ) guidelines were used to assess the level of evidence per study. This assesses the study design and how well a study was carried out and helps judge whether research conclusions are accurate. Level of evidence scores range from 1 ++ , 1 + , 1 – , 2 ++ , 2 + , 2 – , 3, to 4. A score of 1 ++ corresponds to high quality meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a very low risk of bias, whereas a score of 4 is assigned to expert opinions ( Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2019 ).

Level of evidence and quality assessments were conducted by one reviewer and verified independently by the review team. Discrepancies in quality appraisal ratings and level of evidence assessment scores were then discussed among the review team until consensus was reached. When consensus was not reached between two reviewers, a third reviewer was asked to resolve conflicts. Studies were included in the present review regardless of their methodological quality and level of evidence to minimize the risk of study selection and reporting bias ( Higgins et al. , 2019 ).

Database searching yielded 4362 records. Following deletion of duplicates, 3270 records were screened on title and abstract and 3222 irrelevant records were excluded. Full texts of the remaining 48 records were screened. Of those, 16 studies were included in this review ( Figure 1 ).

Study identification, screening and selection process.

Study characteristics

Most studies were conducted in the USA ( n = 8) and the UK ( n = 6), with the majority being uncontrolled before–after studies ( n = 8) and RCTs ( n = 4). Half of the studies ( n = 8) used multiple researcher-designed instruments to collect data and collected data from rural/underprivileged areas. Five studies were underpinned by theory including the Health Belief Model ( Fung et al. , 2018 ; Williams et al. , 2021 ); elements of Self-Regulation Theory, Theory of Planned Behaviour, and Implementation Intentions ( Emery et al. , 2019 ); Ottawa Decision Support Framework ( Lau et al. , 2015 ) and Theory of Planned Behaviour ( Mueller et al. , 2019 ). Six studies used large or national multimodal campaigns as their intervention with three studies reporting on the same campaign namely the ‘Be Clear on Cancer’ UK-based campaign ( Ironmonger et al. , 2015 ; Moffat et al. , 2015 ; Power and Wardle, 2015 ) ( Table 1 ).

Study characteristics ( n = 16)

n = 5 studies underpinned by theory.

n = number of times an outcome was measured.

n = number of times an instrument was used.

All 16 studies had clear research questions and used appropriate data collection methods. RCTs ( n = 4) performed appropriate randomization, had comparable groups at baseline, presented complete data outcomes, and had participants adhere to the assigned intervention; however, only one RCT reported on blinding the outcome assessor ( Emery et al. , 2019 ) ( Supplementary Table 2S ). As for non-RCTs ( n = 11), only three studies reported that participants were representative of the target population ( Power and Wardle, 2015 ; Sakoda et al. , 2020 ; Williams et al. , 2021 ), and one study accounted for confounders ( Williams et al. , 2021 ). Otherwise, all non-RCTs met the remaining MMAT criteria ( Supplementary Table 3S ). The only mixed methods study ( Cardarelli et al. , 2017 ) met most of the MMAT criteria; however, it was unclear as to how data were synthesized and whether there were divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results ( Supplementary Table 4S ).

Half of the studies ( n = 8) scored 2 + on the SIGN level of evidence criteria, indicating well-conducted non-RCTs with a low risk of confounding or bias and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal. Only one RCT ( Emery et al. , 2019 ), and one non-RCT ( Williams et al. , 2021 ) had a low risk of bias.

Findings from individual studies are reported in Table 2 .

Findings from individual studies ( n = 16)

CG, control group; CI, confidence interval; CT, computed tomography; CXR, chest X-ray; DA, decision aid; GP, general practitioner; IG, intervention group; LC, lung cancer; LCS, lung cancer screening; LDCT, low dose computed tomography; M, mean; MD, mean difference; NR, not reported; O, objective; ODSF, Ottawa decision support framework; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RR, relative rate; SD, standard deviation; SRT, self-regulation theory; TPB, theory of planned behaviour; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America; χ 2 , chi-square test.

Findings according to review objectives: O1: knowledge and/or awareness of LC; O2: help-seeking intentions and/or behaviours for LC; O3: early detection of LC, including clinical outcomes.

Knowledge and awareness

Subjective and objective knowledge of LC were promoted in 12 studies using approaches, such as decision aids ( Lau et al. , 2015 ; Mazzone et al. , 2017 ; Housten et al. , 2018 ); film and booklet ( Ruparel et al. , 2019 ) and educational sessions ( Williams et al. , 2021 ; Sakoda et al. , 2020 ). Lau et al. (2015) evaluated the effectiveness of a web-based decision aid ( www.shouldiscreen.com ) among 60 at-risk individuals and found that knowledge of risk factors, benefits and harms of screening, screening eligibility and percentage of benign lumps increased significantly 4 months post-test [pre-test: mean = 7.52/14, standard deviation (SD) = 1.89; post-test: mean = 10.93/14, SD = 2.19; p < 0.001]. A second study used the same decision aid and also reported statistically significant increases in knowledge of screening-eligible ages ( p < 0.0001), smoking history eligibility criteria ( p < 0.0001), benefits ( p = 0.03) and harms ( p < 0.0001) of LC screening 1 month post-test ( Mazzone et al. , 2017 ).

An information film and booklet (intervention group [IG]) compared with booklet only (control group [CG]) yielded a statistically significant increase in knowledge in both groups, with a greater improvement among IG ( p < 0.001) ( Ruparel et al. , 2019 ). Educational interventions in the form of LC screening classes ( Sakoda et al. , 2020 ) and a 4-week educational intervention ( Williams et al. , 202 1) were also instrumental in increasing objective knowledge of LC screening immediately post-test and 3 months post-test (both p < 0.001).

As for knowledge of LC signs, symptoms, and risk factors, a 90-min educational session significantly increased awareness of warning signs for LC and LC risk factors 1 month, 3 months and 6 months post-test ( p < 0.001) ( Meneses-Echávez et al. , 2018 ). Three before–after studies evaluated the impact of the UK campaign ‘Be Clear on Cancer’ on knowledge of LC signs and symptoms ( Ironmonger et al. , 2015 ; Moffat et al. , 2015 ; Power and Wardle, 2015 ). The campaign was successful in increasing awareness of cough ( p < 0.001), breathlessness ( p = 0.024), haemoptysis ( p < 0.001), chest pain ( p = 0.015) and unexplained weight loss ( p < 0.001) as symptoms of LC ( Ironmonger et al. , 2015 ). Recall and recognition of a persistent cough or hoarseness as signs of LC also increased significantly from 67% pre-campaign to 78% post-campaign ( p < 0.001) ( Power and Wardle, 2015 ). The increase in unprompted awareness of cough/hoarseness was significantly lower among men as compared with women (45% vs 55%; p = 0.001) ( Moffat et al. , 2015 ), and there was no statistically significant change in pre- and post-campaign results for individuals aged 75 years or more ( p = 0.721) as compared with 11% increase for the 55–74 years age group ( p = 0.001). As for prompted awareness, the proportion of participants identifying a ‘cough for 3 weeks or more that doesn’t go away’ as definite warning sign of LC increased from 18% pre-campaign to 33% post-campaign ( p < 0.001), with no statistically significant difference between men and women pre-campaign ( p = 0.389) and post-campaign ( p = 0.587) ( Moffat et al. , 2015 ).

In contrast, a spirometry, self-help manual, action and coping plans and tailored monthly prompts (SMS, emails, post-cards, phone calls, and fridge magnets) (IG) yielded no statistically significant changes in knowledge in comparison to spirometry and brief general discussion about lung health (CG) 1 and 12 months post-test (mean difference = -0.2, p = 0.3954 vs. mean Difference = –0.1, p = 0.6083, respectively) ( Emery et al. , 2019 ). Similarly, a four-day research education seminar on cancer prevention (IG) and biospecimen collection (CG) did not yield a statistically significant increase in awareness of LC early detection immediately post-education ( p = 0.18 and p = 0.49, respectively; group comparison p = 0.13) ( Fung et al. , 2018 ).

Help-seeking

Ten studies addressed help-seeking for LC including seeking help from a General Practitioner (GP) and deciding to undertake LC screening. Spirometry, self-help manual, action and coping plans, and tailored monthly prompts which initially failed to raise LC awareness, were successful in increasing respiratory consultations by 40% among the IG [95% Confidence Interval (CI) IG 0.57 (0.47–0.70), CG 0.41 (0.32–0.52), Relative Rate 1.40 (1.08–1.82); p = 0.0123] ( Emery et al. , 2019 ).

Mueller et al. (2019) conducted a feasibility RCT with block randomization to four groups: tailored information and Theory of Planned Behaviour components (IG); untailored information with Theory of Planned Behaviour components; tailored information without Theory of Planned Behaviour components; and usual care (CG). It was found that the four groups differed significantly in scores on the help-seeking intention variable, ( χ 2 (3) = 8.14, p = 0.04), with the highest intention reported in the IG ( Mueller et al. , 2019 ). In contrast, an uncontrolled before–after study using the Health Belief Model reported no statistically significant changes in intent and cue to action immediately and 3 months following a 4-week educational intervention ( Williams et al. , 2021 ).

The campaign ‘Be Clear on Cancer’ was instrumental in increasing help-seeking for LC symptoms and reducing barriers to help-seeking ( Ironmonger et al. , 2015 ; Moffat et al. , 2015 ; Power and Wardle, 2015 ). Help-seeking for cough increased by 63% during the campaign and by 46% 8 weeks later among at-risk groups ( p < 0.001) ( Ironmonger et al. , 2015 ). The campaign was also associated with a 63% increase in GP attendances for symptoms linked to the campaign, with no difference between genders ( p = 0.107) ( Moffat et al. , 2015 ). The largest increase was seen in the 50–59-year age group in comparison to older age groups (88%, p < 0.001). As for perceived barriers to help-seeking, there was no statistically significant change in barriers targeted by the campaign, such as being ‘worried about wasting the doctor’s time’ (26% in 2010 and 24% in 2012, p = 0.158) or believing that the ‘doctor would be difficult to talk to’ (14% in 2010 and 13% in 2012, p = 0.617). However, barriers not targeted by the campaign, such as being ‘too scared’ ( p = 0.016), being ‘worried about what the doctor might find’ ( p = 0.002), ‘difficulty arranging transport’ ( p = 0.002), ‘difficulty making an appointment’ ( p = 0.025) and being ‘too busy’ ( p = 0.009) were less endorsed post-campaign ( Power and Wardle, 2015 ).

In terms of screening decisions, Cardarelli et al. (2017) conducted a multimodal campaign titled ‘Terminate Lung Cancer’ and found that, out of 145 high-risk individuals, 73 (50.3%) came across the campaign. Of those, 5 (3.4%) thought about getting an LDCT and 2 (1.4%) sought information about LDCT. Three studies used the Decision Conflict Scale ( Lau et al. , 2015 ; Ruparel et al. , 2019 ; Sakoda et al. , 2020 ). A web-based decision aid yielded a decrease in Decision Conflict Scale scores indicating lower decisional conflict (pre-test mean = 46.33, SD = 29.69; post-test mean = 15.08, SD = 25.78; p < 0.001) ( Lau et al. , 2015 ). In contrast, participants who watched an information film and read a booklet (IG) had higher decisional conflict (mean = 8.5/9, SD = 1.3) in comparison to those who read a booklet only (CG) (mean = 8.2/9, SD = 1.5; p = 0.007) ( Ruparel et al. , 2019 ). Moreover, an LC screening class led to a decrease in the proportion of at-risk participants who wanted to be screened from 80% pre-test to 65% immediately post-test ( Sakoda et al. , 2020 ).

Early detection

The effect of interventions on early detection of LC (i.e. screening uptake and clinical outcomes) was addressed in seven studies. LDCT uptake varied widely between 38% after a 4-week educational intervention ( Williams et al. , 2021 ) and 94.6% following face-to-face counselling and shared web-based decision-making ( Mazzone et al. , 2017 ). The multimodal ‘Terminate Lung Cancer’ campaign yielded a significant uptake of LDCT in the two intervention regions as compared with the control region ( p -value not reported) ( Cardarelli et al. , 2017 ). Another social media-based campaign was linked to a 3% increase in LDCT per week immediately post-campaign and a further 5.8% increase a week later ( p = 0.001) ( Jessup et al. , 2018 ). In contrast, LDCT completion rates showed no statistical significance between those who watched an information film and read a booklet (IG) and those who read a booklet only (CG) ( p = 0.66) ( Ruparel et al. , 2019 ).

Clinical outcomes reported following large campaigns included the number of chest X-rays and CT scans ordered, new LC cases, stage at diagnosis and LC treatments ( Ironmonger et al. , 2015 ; Kennedy et al. , 2018 ). The ‘Be Clear on Cancer’ campaign was associated with an increase in GP-referred chest X-rays and CT scans by 18.6% and 15.7%, respectively ( p < 0.001) ( Ironmonger et al. , 2015 ). Moreover, LC diagnosis increased by 9.1% ( p < 0.001) for IG and 1.5% for the CG ( p = 0.373) and the proportion of nonsmall cell LC diagnosed at stage I increased from 14.1% to 17.3% ( p < 0.001) and decreased from 52.5% to 49% ( p < 0.001) for stage IV. As for treatments, there was a 2.3%-point increase ( p < 0.001) in resections for patients seen (IG), with no evidence that these proportions changed in CG pre-campaign ( p = 0.404) and post-campaign ( p = 0.425) ( Ironmonger et al. , 2015 ). A local UK campaign which overlapped with ‘Be Clear on Cancer’ also resulted in an 80.8% increase in community-ordered chest X-rays between the 3 years pre-campaign and 3 years post-campaign and yielded an 8.8% increase in patients diagnosed with stage I/II LC as opposed to a 9.3% reduction in cases of stage III/IV LC ( χ 2 (1) = 32.2, p < 0.0001) ( Kennedy et al. , 2018 ).

A wide range of educational interventions were implemented across the reviewed studies, with several studies testing large national and multimodal campaigns. Most interventions explored knowledge and awareness of LC and its screening, while others examined help-seeking behaviours and early detection of LC, including screening uptake and clinical outcomes, such as stage of LC at diagnosis and treatments received.

Overall, participants were poorly informed about LC at baseline. However, web-based decision aids ( Lau et al. , 2015 ; Mazzone et al. , 2017 ; Housten et al. , 2018 ), information resources ( Ruparel et al. , 2019 ) and educational sessions ( Sakoda et al. , 2020 ; Williams et al. , 2021 ) yielded a significant increase in knowledge and awareness of LC risk factors, warning signs, benefits and harms of screening, and screening eligibility. Notably, tailored monthly prompts (i.e. SMS, emails, post-cards, phone calls, fridge magnets) did not significantly increase LC awareness, detection, or screening uptake ( Emery et al. , 2019 ).

In terms of participants’ sociodemographic profiles, men demonstrated lower awareness than women ( Moffat et al. , 2015 ). Gender disparity in knowledge is well documented in other malignancies including colorectal ( Clarke et al. , 2016 ) and skin ( Christoph et al. , 2016 ) cancers. Age also played a role in increased LC awareness, with a significant improvement in unprompted awareness in the 55–74 years age group ( Moffat et al. , 2015 ). This finding is encouraging since LC is mainly diagnosed in older generations. In the USA, for example, LC is most common among those aged 65 years or older, with a median age of 71 years at diagnosis ( National Cancer Institute, 2020 ). In an Irish study, Ryan et al. (2015) emphasized the importance of age as a significant risk factor in cancer diagnosis and highlighted that, even though age is a nonmodifiable risk factor, researchers must target information to increase LC awareness and promote consultation among at-risk age groups ( McCutchan et al. , 2019 ).

In keeping with high-risk groups, half of the studies were conducted in rural/underprivileged areas. A pooled analysis of case–control studies found that socioeconomic deprivation and lack of healthcare access among at-risk populations were associated with advanced LC at diagnosis ( Hovanec et al. , 2018 ). Therefore, McCutchan et al. (2019) identified the need for multi-faceted community-based interventions to encourage high-risk individuals, living in deprived areas, to seek LC information outside of the GP setting. This may promote better relationships between high-risk groups and trained intervention facilitators, subsequently improving engagement in LC screening and help-seeking ( McCutchan et al. , 2019 ).

Interventions aiming to increase help-seeking intentions ought to consider incorporating tailored information based on, for example, the components of the Theory of Planned Behaviour ( Mueller et al. , 2019 ). Such theory-based interventions should address individuals’ attitudes, social norms, and perceived behaviour control as well as integrating measures to ensure effective decision-making skills ( Ruparel et al. , 2019 ). Moreover, at-risk individuals should be encouraged to consider the benefits and harms of health screening in order to make informed decisions and improve health outcomes ( Bell et al. , 2017 ). Current evidence suggests that the use of decision aids can increase knowledge of the benefits and harms of LC screening, whilst providing a better understanding of the nature of screening ( Reuland et al. , 2018 ). Therefore, methods to help dissipate LC screening decisional conflicts, such as video- and web-based decision aids should be considered ( Lau et al. , 2015 ; Mazzone et al. , 2017 ; Housten et al. , 2018 ). Notably, the use of such aids proved successful in reducing decision conflict and cancer-related distress among individuals at risk for breast ( Metcalfe et al. , 2017 ), prostate ( Reidy et al. , 2018 ) and colorectal ( Perestelo-Perez et al. , 2019 ) cancers, inclusive of those with low literacy and health literacy levels.

Three studies reported on a successful national campaign in the UK titled ‘Be Clear on Cancer’ which resulted in a significant increase in awareness of LC symptoms ( Ironmonger et al. , 2015 ; Moffat et al. , 2015 ; Power and Wardle, 2015 ). This campaign also helped reduce barriers to help-seeking, increase GP consultations for at-risk individuals, increase in individuals requesting chest X-rays, and increase in GP-referred chest X-rays and CT scans. Moreover, there was an encouraging increase in early-stage LC diagnosis as a result of this campaign ( Ironmonger et al. , 2015 ). Alternative strategies, such as the use of social media campaigns could be modified to drive engagement with health services in people with minor/early symptoms ( Jessup et al. , 2018 ). Freeman et al. (2015) reported on lessons learned from the use of social media in public health campaigns and identified positive changes in motivation and action. The use of social media makes it easier to connect with specific population cohorts, increase information visibility, and potentially deliver successful health promotion campaigns. It is worth noting, however, the age profile of at-risk individuals and the learning strategies that appeal to high-risk age groups ( Chelf et al. , 2002 ; Saab et al. , 2017b ).

There are several complex barriers that can affect an individual’s understanding of a disease and impede decision-making and help-seeking. It is evident from this review that multimodal public health campaigns would best suit high-risk populations. Approaching health from a population perspective, future interventions and campaigns should consider including a structured theoretical framework, such as the Theory of Planned Behaviour ( Ajzen and Manstead, 2007 ). Moreover, future interventions ought to incorporate targeted information through the use of educational resources, face-to-face counselling, and video- and web-based decision aids, while being cognizant of the preferred learning strategies and the key characteristics of health-promoting messages that would appeal to at-risk groups.

Limitations

Rigour was sought in the conduct and reporting of this systematic review. However, several threats to generalizability are worthy of note. While some of the review team members were multilingual, none of the languages used in non-English language papers was spoken by the research team and no resources were available to professionally translate non-English papers to English, which resulted in excluding those. Moreover, while the five-year search limit helped source the latest evidence, older interventions were omitted. Generalizability of findings is also hindered by the small number of studies included and the fact that almost half of the reviewed studies ( n = 7) did not meet two key quality assessment criteria namely ‘participants representative of target population’ and ‘confounder accounted for in the design and analysis’ and only two studies had a low risk of bias ( Emery et al. , 2019 ; Williams et al. , 2021 ). Study selection bias could have occurred, since only outcomes that were in line with the review aims were reported and no records were sought from the grey literature.

Despite this being a systematic review of interventions, a meta‐analysis was not plausible primarily due to heterogeneity in study designs, outcomes and outcome measures. The reliability and generalizability of the review results are limited further by the presence of three sources of bias: (i) study designs: the included studies used six different study designs; (ii) study instruments: half of the studies ( n = 8) used researcher-designed instruments and failed to report on the validity and reliability of those instruments and (iii) follow-up periods: diverse follow-up periods of data collection were evident, with some studies not having baseline data and others measuring outcomes either immediately post-test or at multiple points post-test. The implication is that findings relating to subjective data measured objectively would change over time and repeat measures at different points in time give different results. Hence, a consistent prepost repeat measures approach is key to minimizing this bias in future research.

Supplementary material is available at Health Promotion International online.

This study was funded by the National Cancer Control Programme, Health Service Executive, Ireland.

Ajzen I. , Manstead A. S. ( 2007 ) 4 Changing health-related behaviours . The Scope of Social Psychology , 43- , 43 – 63 .

Google Scholar

American Cancer Society ( 2019 ) Signs and symptoms of lung cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/lung-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/signs-symptoms.html (last accessed 7 June 2020).

Bell N. R. , Grad R. , Dickinson J. A. , Singh H. , Moore A. E. , Kasperavicius D. et al. ( 2017 ) Better decision making in preventive health screening: balancing benefits and harms . Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien , 63 , 521 – 524 .

Bray F. , Ferlay J. , Soerjomataram I. , Siegel R. L. , Torre L. A. , Jemal A. ( 2018 ) Cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries . CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians , 68 , 394 – 424 .

Cardarelli R. , Roper K. L. , Cardarelli K. , Feltner F. J. , Prater S. , Ledford K. M. et al. ( 2017 ) Identifying community perspectives for a lung cancer screening awareness campaign in Appalachia Kentucky: the Terminate Lung Cancer (TLC) study . Journal of Cancer Education , 32 , 125 – 134 .

Carter‐Harris L. ( 2015 ) Lung cancer stigma as a barrier to medical help‐seeking behavior: practice implications . Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners , 27 , 240 – 245 .

Cassim S. , Chepulis L. , Keenan R. , Kidd J. , Firth M. , Lawrenson R. ( 2019 ) Patient and carer perceived barriers to early presentation and diagnosis of lung cancer: a systematic review . BMC Cancer , 19 , 25 .

Chelf J. H. , Deshler A. , Thiemann K. , Dose A. M. , Quella S. K. , Hillman S. ( 2002 , June) Learning and support preferences of adult patients with cancer at a comprehensive cancer center . Oncology Nursing Forum , 29 , 863 – 867 .

Chowienczyk S. , Price S. , Hamilton W. ( 2020 ) Changes in the presenting symptoms of lung cancer from 2000–2017: a serial cross-sectional study of observational records in UK primary care . British Journal of General Practice , 70 , e193 – e199 .

Christoph S. , Cazzaniga S. , Hunger R. E. , Naldi L. , Borradori L. , Oberholzer P. A. ( 2016 ) Ultraviolet radiation protection and skin cancer awareness in recreational athletes: a survey among participants in a running event . Swiss Medical Weekly , 146, w14297 .

Clarke N. , Gallagher P. , Kearney P. M. , McNamara D. , Sharp L. ( 2016 ) Impact of gender on decisions to participate in faecal immunochemical test‐based colorectal cancer screening: a qualitative study . Psycho-oncology , 25 , 1456 – 1462 .

Cunningham Y. , Wyke S. , Blyth K. G. , Rigg D. , Macdonald S. , Macleod U. et al. ( 2019 ). Lung cancer symptom appraisal among people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A qualitative interview study . Psycho‐oncology , 28 , 718 – 725 .

Dlamini S. B. , Sartorius B. , Ginindza T. ( 2019 ) Mapping the evidence on interventions to raise awareness on lung cancer in resource poor settings: a scoping review protocol . Systematic Reviews , 8 , 1 – 5 .

Ellis P. M. and , Vandermeer R. ( 2011 ) Delays in the diagnosis of lung cancer . Journal of Thoracic Disease , 3 , 183 .

Emery J. D. , Murray S. R. , Walter F. M. , Martin A. , Goodall S. , Mazza D. et al. ( 2019 ) The Chest Australia Trial: a randomised controlled trial of an intervention to increase consultation rates in smokers at risk of lung cancer . Thorax , 74 , 362 – 370 .

Freeman B. , Potente S. , Rock V. , McIver J. ( 2015 ) Social media campaigns that make a difference: what can public health learn from the corporate sector and other social change marketers . Public Health Research & Practice , 25 , e2521517 .

Fung L. C. , Nguyen K. H. , Stewart S. L. , Chen , Jr M. S. , Tong E. K. ( 2018 ) Impact of a cancer education seminar on knowledge and screening intent among Chinese Americans: results from a randomized, controlled, community‐based trial . Cancer , 124 , 1622 – 1630 .

Higgins J. P. , Thomas J. , Chandler J. , Cumpston M. , Li T. , Page M. J. , Welch V. A. (eds) ( 2019 ). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions . John Wiley & Sons, Chichester UK .

Google Preview

Holmberg L. , Sandin F. , Bray F. , Richards M. , Spicer J. , Lambe M. et al. ( 2010 ) National comparisons of lung cancer survival in England, Norway and Sweden 2001–2004: differences occur early in follow-up . Thorax , 65 , 436 – 441 .

Hong Q. N. , Fàbregues S. , Bartlett G. , Boardman F. , Cargo M. , Dagenais P. et al. ( 2018 ) The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers . Education for Information , 34 , 285 – 291 .

Housten A. J. , Lowenstein L. M. , Leal V. B. , Volk R. J. ( 2018 ) Responsiveness of a brief measure of lung cancer screening knowledge . Journal of Cancer Education , 33 , 842 – 846 .

Hovanec J. , Siemiatycki J. , Conway D. I. , Olsson A. , Stücker I. , Guida F. et al. ( 2018 ) Lung cancer and socioeconomic status in a pooled analysis of case–control studies . PLoS One , 13 , e0192999 .

Ironmonger L. , Ohuma E. , Ormiston-Smith N. , Gildea C. , Thomson C. S. , Peake M. D. ( 2015 ) An evaluation of the impact of large-scale interventions to raise public awareness of a lung cancer symptom . British Journal of Cancer , 112 , 207 – 216 .

Jemal A. , Fedewa S. A. ( 2017 ) Lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography in the United States—2010 to 2015 . JAMA Oncology , 3 , 1278 – 1281 .

Jessup D. L. , Glover , IV M. , Daye D. , Banzi L. , Jones P. , Choy G. et al. ( 2018 ) Implementation of digital awareness strategies to engage patients and providers in a lung cancer screening program: retrospective study . Journal of Medical Internet Research , 20 , e52 .

Kennedy M. P. , Cheyne L. , Darby M. , Plant P. , Milton R. , Robson J. M. et al. ( 2018 ) Lung cancer stage-shift following a symptom awareness campaign . Thorax , 73 , 1128 – 1136 .

Koo M. M. , Hamilton W. , Walter F. M. , Rubin G. P. , Lyratzopoulos G. ( 2018 ) Symptom signatures and diagnostic timeliness in cancer patients: a review of current evidence . Neoplasia , 20 , 165 – 174 .

Lau Y. K. , Caverly T. J. , Cao P. , Cherng S. T. , West M. , Gaber C. et al. ( 2015 ) Evaluation of a personalized, web-based decision aid for lung cancer screening . American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 49 , e125 – e129 .

Marcus P. M. , Doria-Rose V. P. , Gareen I. F. , Brewer B. , Clingan K. , Keating K. et al. ( 2016 ) Did death certificates and a death review process agree on lung cancer cause of death in the National Lung Screening Trial? Clinical Trials: Journal of the Society for Clinical Trials , 13 , 434 – 438 .

Mazzone P. J. , Tenenbaum A. , Seeley M. , Petersen H. , Lyon C. , Han X. et al. ( 2017 ) Impact of a lung cancer screening counseling and shared decision-making visit . Chest , 151 , 572 – 578 .

McCutchan G. , Hiscock J. , Hood K. , Murchie P. , Neal R. D. , Newton G. et al. ( 2019 ) Engaging high-risk groups in early lung cancer diagnosis: a qualitative study of symptom presentation and intervention preferences among the UK’s most deprived communities . BMJ Open , 9 , e025902 .

Meneses-Echávez J. F. , Alba-Ramírez P. A. , Correa-Bautista J. E. ( 2018 ) Raising awareness for lung cancer prevention and healthy lifestyles in female scholars from a low-income area in Bogota, Colombia: evaluation of a national framework . Journal of Cancer Education , 33 , 1294 – 1300 .

Metcalfe K. A. , Dennis C. L. , Poll A. , Armel S. , Demsky R. , Carlsson L. et al. ( 2017 ) Effect of decision aid for breast cancer prevention on decisional conflict in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation: a multisite, randomized, controlled trial . Genetics in Medicine , 19 , 330 – 336 .

Moffat J. , Bentley A. , Ironmonger L. , Boughey A. , Radford G. , Duffy S. ( 2015 ) The impact of national cancer awareness campaigns for bowel and lung cancer symptoms on sociodemographic inequalities in immediate key symptom awareness and GP attendances . British Journal of Cancer , 112 , S14 – S21 .

Moher D. , Liberati A. , Tetzlaff J. , Altman D. G. , Grp P. ( 2009 ) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement (Reprinted from Annals of Internal Medicine) . Physical Therapy , 89 , 873 – 880 .

Mueller J. , Davies A. , Jay C. , Harper S. , Blackhall F. , Summers Y. et al. ( 2019 ) Developing and testing a web‐based intervention to encourage early help‐seeking in people with symptoms associated with lung cancer . British Journal of Health Psychology , 24 , 31 – 65 .

National Cancer Institute ( 2020 ) Cancer stat facts: lung and bronchus cancer. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html (last accessed 5 June 2020).

National Lung Screening Trial Research Team ( 2011 ) Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening . New England Journal of Medicine , 365 , 395 – 409 .

Nimmons K. , , Beaudoin C. E. and , St. John J. A. ( 2017 ) The outcome evaluation of a CHW cancer prevention intervention: testing individual and multilevel predictors among hispanics living along the Texas-Mexico Border . Journal of Cancer Education , 32 , 183 – 189 .

O'Mahony M. , McCarthy G. , Corcoran P. , Hegarty J. ( 2013 ) Shedding light on women's help seeking behaviour for self discovered breast symptoms . European Journal of Oncology Nursing , 17 , 632 – 639 .

Oudkerk M. , Devaraj A. , Vliegenthart R. , Henzler T. , Prosch H. , Heussel C. P. et al. ( 2017 ) European position statement on lung cancer screening . The Lancet Oncology , 18 , e754 – e766 .

Perestelo-Perez L. , Rivero-Santana A. , Torres-Castaño A. , Ramos-Garcia V. , Alvarez-Perez Y. , Gonzalez-Hernandez N. et al. ( 2019 ) Effectiveness of a decision aid for promoting colorectal cancer screening in Spain: a randomized trial . BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making , 19 , 8 .

Power E. , Wardle J. ( 2015 ) Change in public awareness of symptoms and perceived barriers to seeing a doctor following Be Clear on Cancer campaigns in England . British Journal of Cancer , 112 , S22 – S26 .

Reidy M. , Saab M. M. , Hegarty J. , Von Wagner C. , O’Mahony M. , Murphy M. et al. ( 2018 ) Promoting men’s knowledge of cancer risk reduction: a systematic review of interventions . Patient Education and Counseling , 101 , 1322 – 1336 .

Reuland D. S. , Cubillos L. , Brenner A. T. , Harris R. P. , Minish B. , Pignone M. P. ( 2018 ) A pre-post study testing a lung cancer screening decision aid in primary care . BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making , 18 , 5 .

Ruparel M. , Quaife S. L. , Ghimire B. , Dickson J. L. , Bhowmik A. , Navani N. et al. ( 2019 ) Impact of a lung cancer screening information film on informed decision-making: a randomized trial . Annals of the American Thoracic Society , 16 , 744 – 751 .

Ryan A. M. , Cushen S. , Schellekens H. , Bhuachalla E. N. , Burns L. , Kenny U. et al. ( 2015 ) Poor awareness of risk factors for cancer in Irish adults: results of a large survey and review of the literature . The Oncologist , 20 , 372 – 378 .

Saab M. M. , , Landers M. , , Cooke E. , , Murphy D. , , Davoren M. and , Hegarty J. ( 2018 ) Enhancing men’s awareness of testicular disorders using a virtual reality intervention . Nursing Research , 67 , 349 – 358 .

Saab M. M. , Landers M. , Hegarty J. ( 2017a ) Exploring awareness and help-seeking intentions for testicular symptoms among heterosexual, gay, and bisexual men in Ireland: a qualitative descriptive study . International Journal of Nursing Studies , 67 , 41 – 50 .

Saab M. M. , Landers M. , Hegarty J. ( 2017b ) Exploring men's preferred strategies for learning about testicular disorders inclusive of testicular cancer: a qualitative descriptive study . European Journal of Oncology Nursing , 26 , 27 – 35 .

Sakoda L. C. , Meyer M. A. , Chawla N. , Sanchez M. A. , Blatchins M. A. , Nayak S. et al. ( 2020 ) Effectiveness of a patient education class to enhance knowledge about lung cancer screening: a quality improvement evaluation . Journal of Cancer Education , 35 , 897 – 890 .

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network ( 2019 ) SIGN 100: a handbook for patients and carer representatives. https://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign100.pdf (last accessed 7 June 2020).

Siegel R. L. , Miller K. D. , Jemal A. ( 2018 ) Cancer statistics, 2018 . CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians , 68 , 7 – 30 .

Smith C. F. , Whitaker K. L. , Winstanley K. , Wardle J. ( 2016 ) Smokers are less likely than non-smokers to seek help for a lung cancer ‘alarm’ symptom . Thorax , 71 , 659 – 661 .

The Cochrane Collaboration ( 2020 ) About Covidence. https://community.cochrane.org/help/tools-and-software/covidence/about-covidence (last accessed 6 June 2020).

Torre L. A. , Siegel R. L. , Jemal A. ( 2016 ) Lung cancer statistics . Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology , 893 , 1 – 19 .

Walter F. M. , Rubin G. , Bankhead C. , Morris H. C. , Hall N. , Mills K. et al. ( 2015 ) Symptoms and other factors associated with time to diagnosis and stage of lung cancer: a prospective cohort study . British Journal of Cancer , 112 , S6 – S13 .

Wilhelm W. J. , Kaunelis D. ( 2005 ) Literature reviews: analysis, planning, and query techniques . Delta Pi Epsilon Journal , 47- , 91 – 106 .

Williams L. B. , Looney S. W. , Joshua T. , McCall A. , Tingen M. S. ( 2021 ) Promoting community awareness of lung cancer screening among disparate populations: results of the cancer-community awareness access research and education project . Cancer Nursing, , 44, 89–97.

World Health Organisation ( 2020 ) WHO report on cancer: setting priorities, investing wisely and providing care for all. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/who-report-on-cancer-setting-priorities-investing-wisely-and-providing-care-for-all (last accessed 20 October 2020).

Supplementary data

Email alerts, citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1460-2245

- Print ISSN 0957-4824

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Lung Cancer Prevention (PDQ®)–Patient Version

What is prevention.

Cancer prevention is action taken to lower the chance of getting cancer. By preventing cancer, the number of new cases of cancer in a group or population is lowered. Hopefully, this will lower the number of deaths caused by cancer.

To prevent new cancers from starting, scientists look at risk factors and protective factors . Anything that increases your chance of developing cancer is called a cancer risk factor; anything that decreases your chance of developing cancer is called a cancer protective factor.

Some risk factors for cancer can be avoided, but many cannot. For example, both smoking and inheriting certain genes are risk factors for some types of cancer, but only smoking can be avoided. Regular exercise and a healthy diet may be protective factors for some types of cancer. Avoiding risk factors and increasing protective factors may lower your risk but it does not mean that you will not get cancer.

Different ways to prevent cancer are being studied, including:

- Changing lifestyle or eating habits.

- Avoiding things known to cause cancer.

- Taking medicines to treat a precancerous condition or to keep cancer from starting.

General Information About Lung Cancer

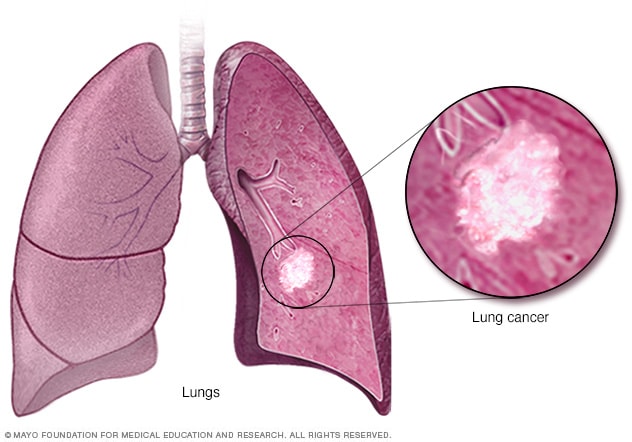

Lung cancer is a disease in which malignant (cancer) cells form in the tissues of the lung., lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in both men and women..

There are two types of lung cancer: small cell lung cancer and non-small cell lung cancer .

For more information about lung cancer, see the following:

- Lung Cancer Screening

- Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment

- Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment

- Cigarette Smoking: Health Risks and How to Quit

Lung cancer causes more deaths per year in the United States than do colon cancer , breast cancer , and prostate cancer combined.

Lung cancer rates are highest in Black men, while lung cancer deaths are highest among Black, American Indian, and Alaska Native men, compared with other racial and ethnic groups in the United States.

Lung Cancer Prevention

Avoiding risk factors and increasing protective factors may help prevent lung cancer., cigarette, cigar, and pipe smoking, secondhand smoke, family history, hiv infection, environmental risk factors, beta carotene supplements in heavy smokers, not smoking, quitting smoking, lower exposure to workplace risk factors, lower exposure to radon, physical activity, beta carotene supplements in nonsmokers, vitamin e supplements, cancer prevention clinical trials are used to study ways to prevent cancer., new ways to prevent lung cancer are being studied in clinical trials..

Avoiding cancer risk factors may help prevent certain cancers. Risk factors include smoking, having overweight , and not getting enough exercise. Increasing protective factors such as quitting smoking and exercising may also help prevent some cancers. Talk to your doctor or other health care professional about how you might lower your risk of cancer.

The following are risk factors for lung cancer:

Tobacco smoking is the most important risk factor for lung cancer . Cigarette , cigar , and pipe smoking all increase the risk of lung cancer. Tobacco smoking causes about 9 out of 10 cases of lung cancer in men and about 8 out of 10 cases of lung cancer in women.

Studies have shown that smoking low tar or low nicotine cigarettes does not lower the risk of lung cancer.

Studies also show that the risk of lung cancer from smoking cigarettes increases with the number of cigarettes smoked per day and the number of years smoked. People who smoke have about 20 times the risk of lung cancer compared to those who do not smoke.

Being exposed to secondhand tobacco smoke is also a risk factor for lung cancer. Secondhand smoke is the smoke that comes from a burning cigarette or other tobacco product, or that is exhaled by smokers. People who inhale secondhand smoke are exposed to the same cancer -causing agents as smokers, although in smaller amounts. Inhaling secondhand smoke is called involuntary or passive smoking.

Having a family history of lung cancer is a risk factor for lung cancer. People with a relative who has had lung cancer may be twice as likely to have lung cancer as people who do not have a relative who has had lung cancer. Because cigarette smoking tends to run in families and family members are exposed to secondhand smoke, it is hard to know whether the increased risk of lung cancer is from the family history of lung cancer or from being exposed to cigarette smoke.

Being infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the cause of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), is linked with a higher risk of lung cancer. People infected with HIV may have more than twice the risk of lung cancer than those who are not infected. Since smoking rates are higher in those infected with HIV than in those not infected, it is not clear whether the increased risk of lung cancer is from HIV infection or from being exposed to cigarette smoke.

- Atomic bomb radiation: Being exposed to radiation after an atomic bomb explosion increases the risk of lung cancer.

- Radiation therapy: Radiation therapy to the chest may be used to treat certain cancers, including breast cancer and Hodgkin lymphoma . Radiation therapy uses x-rays , gamma rays , or other types of radiation that may increase the risk of lung cancer. The higher the dose of radiation received, the higher the risk. The risk of lung cancer following radiation therapy is higher in patients who smoke than in nonsmokers.

- Imaging tests: Imaging tests, such as CT scans , expose patients to radiation. Low-dose spiral CT scans expose patients to less radiation than higher dose CT scans. In lung cancer screening , the use of low-dose spiral CT scans can lessen the harmful effects of radiation.

- Radon: Radon is a radioactive gas that comes from the breakdown of uranium in rocks and soil. It seeps up through the ground, and leaks into the air or water supply. Radon can enter homes through cracks in floors, walls, or the foundation, and levels of radon can build up over time.

Studies show that high levels of radon gas inside the home or workplace increase the number of new cases of lung cancer and the number of deaths caused by lung cancer. The risk of lung cancer is higher in smokers exposed to radon than in nonsmokers who are exposed to it. In people who have never smoked, about 26% of deaths caused by lung cancer have been linked to being exposed to radon.

- Tar and soot.

These substances can cause lung cancer in people who are exposed to them in the workplace and have never smoked. As the level of exposure to these substances increases, the risk of lung cancer also increases. The risk of lung cancer is even higher in people who are exposed and also smoke.

- Air pollution: Studies show that living in areas with higher levels of air pollution increases the risk of lung cancer.

Taking beta carotene supplements (pills) increases the risk of lung cancer, especially in smokers who smoke one or more packs a day. The risk is higher in smokers who have at least one alcoholic drink every day.

The following are protective factors for lung cancer:

The best way to prevent lung cancer is to not smoke.

Smokers can decrease their risk of lung cancer by quitting. In smokers who have been treated for lung cancer, quitting smoking lowers the risk of new lung cancers. Counseling , the use of nicotine replacement products, and antidepressant therapy have helped smokers quit for good.

In a person who has quit smoking, the chance of preventing lung cancer depends on how many years and how much the person smoked and the length of time since quitting. After a person has quit smoking for 10 years, the risk of lung cancer decreases 30% to 60%.

Although the risk of dying from lung cancer can be greatly decreased by quitting smoking for a long period of time, the risk will never be as low as the risk in nonsmokers. This is why it is important for young people not to start smoking.

See the following for more information on quitting smoking:

- Tobacco (includes help with quitting)

Laws that protect workers from being exposed to cancer-causing substances, such as asbestos, arsenic, nickel, and chromium, may help lower their risk of developing lung cancer. Laws that prevent smoking in the workplace help lower the risk of lung cancer caused by secondhand smoke.

Lowering radon levels may lower the risk of lung cancer, especially among cigarette smokers. High levels of radon in homes may be reduced by taking steps to prevent radon leakage, such as sealing basements.

It is not clear if the following decrease the risk of lung cancer:

Some studies show that people who eat high amounts of fruits or vegetables have a lower risk of lung cancer than those who eat low amounts. However, since smokers tend to have less healthy diets than nonsmokers, it is hard to know whether the decreased risk is from having a healthy diet or from not smoking.

Some studies show that people who are physically active have a lower risk of lung cancer than people who are not. However, since smokers tend to have different levels of physical activity than nonsmokers, it is hard to know if physical activity affects the risk of lung cancer.

The following do not decrease the risk of lung cancer:

Studies of nonsmokers show that taking beta carotene supplements does not lower their risk of lung cancer.

Studies show that taking vitamin E supplements does not affect the risk of lung cancer.

Cancer prevention clinical trials are used to study ways to lower the risk of developing certain types of cancer. Some cancer prevention trials are conducted with healthy people who have not had cancer but who have an increased risk for cancer. Other prevention trials are conducted with people who have had cancer and are trying to prevent another cancer of the same type or to lower their chance of developing a new type of cancer. Other trials are done with healthy volunteers who are not known to have any risk factors for cancer.

The purpose of some cancer prevention clinical trials is to find out whether actions people take can prevent cancer. These may include eating fruits and vegetables, exercising, quitting smoking, or taking certain medicines , vitamins , minerals , or food supplements.

Information about clinical trials supported by NCI can be found on NCI’s clinical trials search webpage. Clinical trials supported by other organizations can be found on the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

About This PDQ Summary

Physician Data Query (PDQ) is the National Cancer Institute's (NCI's) comprehensive cancer information database. The PDQ database contains summaries of the latest published information on cancer prevention, detection, genetics, treatment, supportive care, and complementary and alternative medicine. Most summaries come in two versions. The health professional versions have detailed information written in technical language. The patient versions are written in easy-to-understand, nontechnical language. Both versions have cancer information that is accurate and up to date and most versions are also available in Spanish .

PDQ is a service of the NCI. The NCI is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH is the federal government’s center of biomedical research. The PDQ summaries are based on an independent review of the medical literature. They are not policy statements of the NCI or the NIH.

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary has current information about lung cancer prevention. It is meant to inform and help patients, families, and caregivers. It does not give formal guidelines or recommendations for making decisions about health care.

Reviewers and Updates

Editorial Boards write the PDQ cancer information summaries and keep them up to date. These Boards are made up of experts in cancer treatment and other specialties related to cancer. The summaries are reviewed regularly and changes are made when there is new information. The date on each summary ("Updated") is the date of the most recent change.

The information in this patient summary was taken from the health professional version, which is reviewed regularly and updated as needed, by the PDQ Screening and Prevention Editorial Board .

Clinical Trial Information

A clinical trial is a study to answer a scientific question, such as whether one treatment is better than another. Trials are based on past studies and what has been learned in the laboratory. Each trial answers certain scientific questions in order to find new and better ways to help cancer patients. During treatment clinical trials, information is collected about the effects of a new treatment and how well it works. If a clinical trial shows that a new treatment is better than one currently being used, the new treatment may become "standard." Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Clinical trials can be found online at NCI's website . For more information, call the Cancer Information Service (CIS), NCI's contact center, at 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237).

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. The content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text. It cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless the whole summary is shown and it is updated regularly. However, a user would be allowed to write a sentence such as “NCI’s PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks in the following way: [include excerpt from the summary].”

The best way to cite this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Screening and Prevention Editorial Board. PDQ Lung Cancer Prevention. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/lung/patient/lung-prevention-pdq . Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389497]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use in the PDQ summaries only. If you want to use an image from a PDQ summary and you are not using the whole summary, you must get permission from the owner. It cannot be given by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the images in this summary, along with many other images related to cancer can be found in Visuals Online . Visuals Online is a collection of more than 3,000 scientific images.

The information in these summaries should not be used to make decisions about insurance reimbursement. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website’s E-mail Us .

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Hosted content

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 57, Issue 11

- Lung cancer • 1: Prevention of lung cancer

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- G E Goodman

- Correspondence to: G E Goodman, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Swedish Medical Center Cancer Institute, Seattle, Washington, USA; gary.goodman{at}swedish.org

Cancer of the lung causes more deaths from cancer worldwide than at any other site. The environmental, genetic, and dietary risk factors are discussed and progress in chemoprevention is reviewed. A better understanding of the molecular events that occur during carcinogenesis has opened up new areas of research in cancer prevention and a number of biochemical markers of high risk individuals have been identified. It is predicted that greater success in chemoprevention will be achieved in the next decade than in the last.

- lung cancer

- risk factors

- biochemical markers

https://doi.org/10.1136/thorax.57.11.994

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

THE PROBLEM

In 1990 cancer caused an estimated six million deaths worldwide and, of these, lung cancer was the most frequent site with an estimated 945 000 deaths. 1 In 2002 the death rate from lung cancer in the USA in both men and women is estimated at 134 900, exceeding the combined total for breast, prostate, and colon cancer. 2 Lung cancer is also the leading cause of cancer death in all European countries and is rapidly increasing in the developing world. Of 40 countries worldwide, the countries with the highest rates are Hungary (81.6/100 000 person years), the Czech Republic, the Russian Federation, Poland, and Denmark. 3 Among women the highest rates were in the US (25.6/100 000 person years), Denmark, Canada, the UK, and New Zealand.

ENVIRONMENTAL RISK FACTORS

In addition to being the biggest cancer killer, lung cancer is one of the few cancers with a well defined aetiology—namely, the inhalation of tobacco smoke. In the USA the death rate from lung cancer parallels the 1965 peak and subsequent decline in cigarette smoking rates. The incidence of lung cancer peaked in 1990 with 41.4 deaths per 1000 person years and has since fallen, reaching a rate of 39.8 in 1995. 4 Shopland et al 5 determined the prevalence of smoking in each of the 50 states from surveys conducted in 1992 and compared these rates with 1985. Kentucky and West Virginia were the highest rates with 32.29% and 30.59% of the adult population 20 years or older being current smokers. Utah had the lowest rate at 17.1%. Forty nine of the 51 areas had a decrease in smoking between 1985 and 1992–93. Rhode Island experienced the greatest decline at –30.7%. Only Utah (+16.3%) and Wisconsin (+1.9%) showed increases. Nationally, the prevalence of smoking declined 17% overall from 1985 to 1992–93. Among subgroups, African American men experienced the highest rates (31.3%) followed by White men (26.4%) and Hispanic mens (25.0%). Among women, Whites and African Americans were similar (22.9% and 22.5%, respectively) whereas smoking among Hispanic women was significantly less (12.7%).

While there have been similar declines in the incidence of smoking in Canada and western Europe, there is concern about the rising rates of smoking in developing countries. 6– 8 China, the world’s most populous country, has tripled cigarette consumption between 1978 and 1987. 9 It is estimated that 70% of Chinese men and 2% of women smoke. 10 Given the 20–30 year lag between exposure and peak incidence of cancer, the potential coming epidemic stresses the urgent need to develop effective prevention strategies.

In addition to the hazard of first hand smoke, the 1986 US Surgeon General’s report concluded that cigarette smoke was a health risk to non-smokers. This has subsequently been supported by over 24 studies showing that exposed non-smokers have an increased relative risk of developing cancer ranging from 1.41 to 2.01. 11– 14

Clearly, cigarette smoking remains the most prevalent and uncontrolled environmental carcinogen in our society. The continued burden of current and ex-smokers in the US and western Europe (the majority of Americans developing lung cancer are ex-smokers 15– 17 ), the increasing incidence of smokers in Asia, and the recruitment of new smokers worldwide guarantee that lung cancer will remain the major cause of cancer death worldwide for the next 25–50 years.

Over the past 10 years there have been advances in our understanding of the epidemiology and genetics of nicotine addiction. 18 These findings have opened new areas of smoking prevention and cessation research using pharmacological interventions with both pharmacological agents and nicotine replacement. 19 As health professionals concerned about lung cancer, we must vigorously support smoking prevention and cessation programmes. 20 We must champion efforts to make tobacco abuse a socially and culturally unacceptable habit and support all governmental actions 21 to eliminate tobacco as an environmental carcinogen.

GENETIC RISK FACTORS

Not all cigarette smokers go on to develop lung cancer. Investigators are working to identify factors which can predict individual susceptibility. 22 One area of study is the family of enzymes responsible for carcinogen activation, degradation, and subsequent DNA repair. 23 These enzymes display gene deletions and polymorphisms which can affect enzyme activity. It has been hypothesised that an individual’s enzyme profile is associated with lung cancer risk. This profile could be used to counsel individuals and could be used to select high risk individuals for specific chemoprevention agents. These enzymes and the metabolic pathways they regulate also have the potential to become targets for preventive agents.

To illustrate this point, benzo[a]pyrene, one of the many carcinogens found in cigarette smoke, is metabolically activated by the P450 family of hepatic enzymes (mainly CYP1A1). 24– 27 The intermediate metabolites are chemically active and can bind to DNA and cause gene dysfunction. Glutathione-S-transferase (GST), epoxide hydrolase (EH) and N-acetytransferase (NAT) detoxify these products. Polymorphisms and/or gene deletions result in modified metabolic activity. 18, 28– 32 Enzymes responsible for DNA repair also display polymorphisms. 33– 35 Studies suggest that genetic alterations in each of these enzyme families can have small effects on an individual’s risk of developing lung cancer.

Gene-diet interaction will also require careful investigation. Studies suggest that low levels of vitamin E can increase the GSTM1 associated risk. 36 Interactions with dietary enzyme factors such as folate and subsequent folate metabolism have also been suggested. 37 Although it is possible that a single polymorphism or dietary interactions may significantly alter the relative risk, it is likely that many interactions, each having a subtle effect, can result in synergistic interactions that greatly affect the overall risk. Determining the risk profile of an individual based on their inherited polymorphisms and their potential dietary interaction will be a complex undertaking. Testing these hypotheses will require studies with a very large sample size to achieve the statistical power.

DIETARY RISK FACTORS

Numerous studies have shown that the incidence of cancer can be inversely related to the intake of many food groups. 38– 41 The serum concentration of many micronutrients is also inversely related to the incidence of cancer. 42– 46 Based on these epidemiological studies, it has been suggested that micronutrients and macronutrients present in our diet may act as cancer inhibiting substances.

Dietary carotenoids were one of the first micronutrients suggested as risk factors for lung cancer. 38 Epidemiological studies reported that individuals with a diet low in β-carotene-rich foods had a higher incidence of lung cancer. 39, 40, 47, 48 Retrospective case-control trials of serum obtained from individuals who later developed lung cancer confirmed that the serum concentrations of β-carotene were lower in cases than in controls. 43, 48 Those in the highest category had a relative risk of 0.5–0.7 compared with those in the highest. Another carotenoid, lycopene, a simple hydrocarbon precursor of β-carotene, has been studied. 49 Lycopene is an effective antioxidant (25% better than β-carotene) and is the second most common dietary carotenoid. The most common source of lycopene in the diet is cooked or processed tomatoes which contain about 30 mg/kg. Like β-carotene, epidemiological studies of the dietary intake or serum concentration of lycopene found an inverse relationship with cancer of the bladder, lung and prostate. 49, 50

Other dietary micronutrients may also be associated with lung cancer risk. Knekt et al reported that dietary flavonoids (found in high concentration in apples) were a strong predictor of lung cancer risk. In a population of 9959 Finnish men and women, those with the highest intake of dietary flavonoids had an incidence of lung cancer that was 59% of those in the lowest quartile. 51 Isothiocyanates, which are widely distributed in cruciferous vegetables, have also been shown to have an inverse relationship with the incidence of lung cancer. 52, 53 In vivo animal model systems have shown that isothiocyanates have activity in decreasing the incidence of cancer of the lung, oesophagus, liver, colon, and bladder.

CHEMOPREVENTION

The pragmatic acceptance that tobacco abuse cannot be easily and rapidly eliminated has given emphasis to the field of lung cancer chemoprevention. Chemoprevention is defined as the use of agents to prevent, inhibit, or reverse the process of carcinogenesis. 54 The underlying hypothesis of prevention is that carcinogenesis is the stepwise accumulation of genetic and epigenetic changes that result in a cell with a malignant phenotype. The goal of cancer prevention scientists is to develop interventions that can interrupt, arrest, or reverse this process. 55

Historically, two major categories of compounds have been investigated for cancer prevention activity. One group consists of naturally occurring dietary micronutrients and their synthetic analogues which have been discussed above. Although epidemiological associations cannot prove a cause and effect relationship, they show strong associations and suggest hypotheses to be tested. The goal is to determine which, if any, of these dietary substances (or combination of substances) are important factors in modifying the incidence of cancer, 56 and whether supplementation of the diet with these micronutrients is an effective method of cancer prevention.

The other group of compounds currently being investigated are synthetic agents. 57 These include a large number of compounds with varying mechanisms including, for example, the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDS) which are potent in vivo inhibitors of colon carcinogenesis 58– 60 and agents such as DFMO (difluoromethyl ornithine), a polyamine synthase inhibitor, which has a broad spectrum of preventive activity in vitro and in vivo. 61– 63

Vitamin A and its family of compounds (the retinoids) were the first dietary constituents to have extensive in vitro and in vivo evidence of chemopreventive activity. 64 The retinoids have been found to be active in many animal model systems using different organ sites as well as different inducing carcinogens. 65 When Sporn et al first discussed the concept of chemoprevention, his work focused on the retinoids. 54

Retinol, its palmitic acid ester, the trace retinoids all-trans-retinoic acid and 13-cis-retinoic acid, together with the synthetic retinoids etretinate and 4-hydroxy phenyl retinamide have all been studied in vitro as well as in human intervention trials. Trials with these agents were started in the early 1980s and a number of them have matured and reported results.