clock This article was published more than 10 years ago

Six questions on China’s one-child policy, answered

What is China’s one-child policy?

For more than three decades, this strictly enforced rule has meant that many Chinese couples could only have one child. They risked huge fines and varying degrees of harassment from local authorities if they had more than one.

China’s Communist Party leaders enacted the policy in 1980 to curb runaway population growth. It has been one of history’s biggest experiments in state-mandated demographic engineering and has been heavily debated.

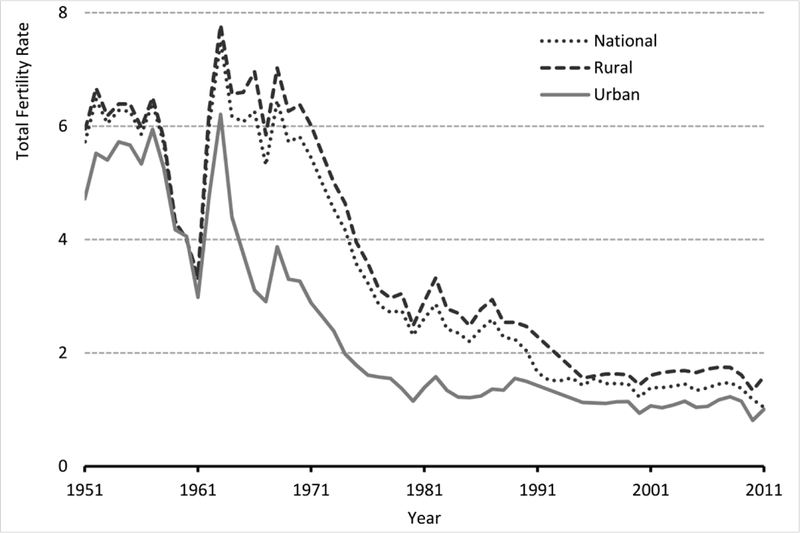

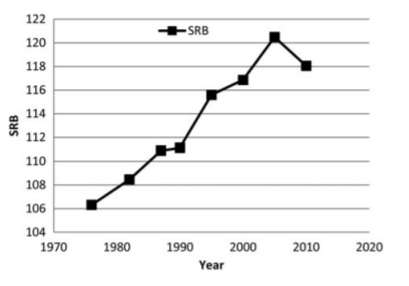

The policy reshaped Chinese society, with birthrates plunging from 4.77 children per woman in the early 1970s to 1.64 in 2011, according to estimates by the United Nations . It also contributed to the world's most unbalanced sex ratio at birth, with boys far outnumbering girls.

What part of the policy is being changed?

China announced Friday that couples can have a second child if either of the parents is an only child. The change affects a limited group of only-child adults of child-bearing age, many of whom were born under the current policy.

But the rest of the policy remains in place — as does the vast, powerful family-planning bureaucracy, with offices in every city, town and village, that was created to enforce the original decree. The leaders are likely changing the policy because of an aging population and a possible future labor shortage.

What will the change mean?

Don’t necessarily expect a sudden surge in population. A lot of people in China were already allowed to have a second child under existing exceptions to the policy. For years, rural peasants whose first child was a girl were permitted to have a second child. In addition, couples who are both ethnic minorities and couples who are both only children were already allowed to have a second child.

Wang Feng, director of the Brookings-Tsinghua Center for Public Policy, offered what he called “an estimation” that at most “1 or 2 million births a year” might occur as a result of the policy change. That would be on top of the current level of 15 million annual births.

He and other experts said that even if given the option of having a second child, many urban couples will still choose to have only one because of the rising costs of housing and education in China’s cities.

How many people does this actually affect?

In China, good, hard numbers on a topic this sensitive are hard to come by. State-run media sometimes say that China has 150 million families with only one child, but some experts think the real number is larger. Even if that is true, no public statistics exist for how many of those only children have spouses with at least one sibling, the group that will now be permitted to have a second child.

Why is the one-child policy so hated and criticized?

Human rights groups have exposed forced abortions , infanticide and involuntary sterilizations, all banned in theory by the government.

The policy has also left quieter devastation in its wake in the form of childless parents — couples too old when their only child suddenly dies to have another.

Much resentment also stems from the huge fines the government collects for violations, estimated to total billions of dollars. No one knows the precise amount because it is kept secret, and the public is not told exactly where the money goes.

Lastly, critics say, there’s something disturbing and wrong with the government infringing on people’s sexual and family decisions by telling them whether they can have children and how many.

Has the policy done any good?

The government says the policy has prevented about 400 million births, which it sees as beneficial for a country whose enormous population poses social, economic and environmental challenges. On the global scale, China claimed in 2011 that its policy single- handedly delayed by five years the date by which the world's population reached 7 billion .

Li Qi contributed to this report.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Understanding the One-Child Policy

Enforcement

- Implications

Does China Still Have the One-Child Policy?

- Did China's One-Child Policy Increase Its Economic Growth?

Is China Encouraging the Birthrate Today?

What happened if you broke the one-child policy, the bottom line.

- International Markets

What Was China's One-Child Policy? Its Implications and Importance

Adam Hayes, Ph.D., CFA, is a financial writer with 15+ years Wall Street experience as a derivatives trader. Besides his extensive derivative trading expertise, Adam is an expert in economics and behavioral finance. Adam received his master's in economics from The New School for Social Research and his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in sociology. He is a CFA charterholder as well as holding FINRA Series 7, 55 & 63 licenses. He currently researches and teaches economic sociology and the social studies of finance at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/adam_hayes-5bfc262a46e0fb005118b414.jpg)

Investopedia / Jiaqi Zhou

The Chinese government implemented the one-child policy mandating that the vast majority of couples in the country could only have one child. The phrase “one-child policy,” used often outside China, can be a bit misleading: the one-child rule didn't apply to all, exceptions were frequently made, and local officials had discretion over how population limits were achieved. These collective efforts were nevertheless intended to alleviate the social, economic, and environmental problems associated with the country's rapidly growing population. The rule was introduced in 1979 and phased out in 2015.

Key Takeaways

- The “one-child policy” is a name given to Chinese government laws for controlling population growth. According to estimates, it prevented about 400 million births in the country.

- Introduced in 1979 and discontinued in 2015, the policy was enforced through a mix of incentives and sanctions.

- The one-child policy has had three important consequences for China's demographics: it reduced the fertility rate considerably, it skewed China's gender ratio because people preferred to abort or abandon their female babies, and resulted in a labor shortage given the increasing proportion of the population who were older adults.

Understanding China's One-Child Policy

The one-child policy refers to a set of laws implemented beginning in 1979 in response to explosive population growth that government officials feared would lead to a demographic disaster. China has a long history of encouraging birth control and family planning. In the 1950s, when population growth started to outpace the food supply, the government started promoting birth control.

However, by the late 1970s, China’s population was quickly approaching 1 billion, and the Chinese government considered ways to curb population growth. This effort began in 1979 with mixed results but was implemented more seriously and uniformly in 1980, as the government standardized the practice nationwide.

There were, however, exceptions for ethnic minorities, for those whose firstborn was labeled as disabled, and for rural families whose firstborn was not a boy. The policy was most effective in urban areas since those in China’s agrarian communities resisted it to a greater extent.

Initially, the one-child policy was meant to be a temporary measure, though, in the end, it may have prevented up to 400 million births. Ultimately, China ended its one-child policy after it became apparent that it might have been too effective: many Chinese were heading into retirement, and the nation’s population had too few young people to provide for the older population’s retirement and healthcare while sustaining continued economic growth.

The government-mandated policy was formally ended Oct. 29, 2015, after its rules had been slowly relaxed to allow more couples fitting certain criteria to have a second child. Now, all couples are allowed to have two children.

There were different methods of enforcement, including incentives and sanctions, that varied across China. For those who complied, there were financial incentives and preferential employment opportunities. For those who violated the policy, there were sanctions, economic and otherwise. At times, the government employed more draconian measures, including forced abortions and sterilization.

The one-child policy was officially discontinued in 2015. The efficacy of the policy itself, though, has been challenged, as it's typical that population growth generally slows as societies gain in income, as happened in China during this time. In China's case, as the birthrate declined, the death rate declined, too, and life expectancy increased.

One-Child Policy Implications

The one-child policy had serious implications for China's demographic and economic future. In the early 2020s, China's fertility rate stands at 1.6, among the lowest in the world. (The U.S. is at 1.7.)

China now has a considerable gender skew—there are roughly 3 to 4% more males than females in the country. With the implementation of the one-child policy and the preference for male children, China had a rise in the abortion of female fetuses, the number of baby girls left in orphanages, and even in infanticides of baby girls.

This continues to affect marriage and birthrates around the country. Fewer females means there were fewer women of childbearing age in China. The drop in birthrates meant fewer children, which occurred as death rates dropped and longevity rates rose. It is estimated that the share of adults ages 65 and older will have risen from just 12% to a projected 26% by 2050. Thus, older parents will be relying on their children to support them, and have fewer children to do so. This is compounded by the massive urbanization of China since 1980, with those living in urban areas increasing from 19% in 1980 to 60% in recent years. China is also facing a potential labor shortage and will have trouble supporting this aging population through its state services.

Finally, the policy led to the proliferation of undocumented, non-first-born children. Their status as undocumented makes it impossible to leave China legally, as they cannot register for a passport. They have no access to public education. Oftentimes, their parents were fined or removed from their jobs.

One-Child Policy FAQs

No. China reverted to a two-child policy after its one-child policy ended in 2015, and the restrictions were gradually loosened before its official end.

Did China's One-Child Policy Increase Its Economic Growth?

There's a chicken or egg quality to any answer: China's one-child policy, by initially reducing population growth, could have contributed to economic gains by creating a larger working-age population relative to children, which would have boosted productivity and savings. However, it's also the case that countries with increases in national wealth tend to have population growth that slows down. Thus, the increase in economic growth in China may have helped reduce the number of Chinese newborns over this time, not the other way around. Whatever the case, the long-term effects of these demographic shifts from about 1979 to 2015 include a shrinking labor force and a greater proportion of the population that is retired, posing challenges for continued economic growth and the social safety net.

Yes. China has implemented or increased parental tax deductions, family leave, housing subsidies for families, and spending on reproductive health and child care services to increase the national birthrate since ending the one-child policy formally in 2015. The Chinese government also promotes flexible work hours and work-from-home options for parents. Most interesting are policies one wouldn't consider related to the birthrate at first glance, such as banning private tutoring companies from profiting off teaching core subjects during weekends or holidays. By lowering educational pressure on children and this often costly financial load on parents, China is attempting to lower the burdens of parenting. With greater financial security, parents may feel better able to handle additional children. Another upshot? By reducing pressure academically, especially on weekends and holidays, families can spend more time together, thus fostering greater family connections.

Violators of China's one-child policy could be fined, forced to have abortions or sterilizations or lose their jobs.

China's one-child policy, a phrase used for a set of laws related to population growth implemented starting in 1979, represented one of the more draconian modern attempts to intervene in a country's rising demographics. While the population did slow, the policy also resulted in unintended consequences, such as an aging population, gender imbalance, and a shrinking workforce. Its discontinuation in 2015 and subsequent measures to encourage higher birth rates reflect China's complex challenges in balancing population control with sustainable economic and social development.

J.N. Wasserstrom. "China in the 21st Century: What Everyone Needs to Know." Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018. Pages 81-84.

Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. " China’s One Child Policy ." Page 1.

National Library of Medicine. " The Effects of China’s Universal Two-Child Policy ."

Library of Congress. " China’s One Child Policy. "

David Howden and Yang Zhou. “ China’s One-Child Policy: Some Unintended Consequences .” Economic Affairs. 34/3. Pages 353-69.

The World Bank. " Fertility Rate, Total (Births per Woman) - China ."

Pew Research Center. " Without One-child Policy, China Still Might Not See Baby Boom, Gender Balance ."

Gao, Fang., Li, Xia. " From One to Three: China’s Motherhood Dilemma and Obstacle to Gender Equality ." Women. (2021.) Pages 252-266.

Population Reference Bureau. " What Can We Learn From the World’s

Largest Population of Older People? "

United Nations. " Revision of World Urbanization Prospects ."

World Health Organization. " Ageing and Health in China ."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/children-428909_1280-5bfc37e04cedfd0026c45dc6.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

China's Former 1-Child Policy Continues To Haunt Families

The legacy of China's one-child rule is still painfully felt by many of those who suffered for having more children. Ran Zheng for NPR hide caption

The legacy of China's one-child rule is still painfully felt by many of those who suffered for having more children.

Editor's note: This story contains descriptions that may be disturbing.

LINYI, China — Outside, rain falls. Inside, a middle-school student completes his homework. His mother watches him approvingly.

She is especially protective of him. He's the youngest of three children this mother had under China's one-child policy.

Giving birth to him was a huge risk — and she took no chances. She carried her son to term while hiding in a relative's house. She wanted to avoid the "family planning officials" in her home village, just outside Linyi, a city of 11 million in China's northern Shandong province, where the policy's enforcement was especially violent.

What was she hiding from? What could the family planning officials have done to her? She demurs, her voice growing quiet. "All we can do is go on living," she says. "There is no use in trying to make sense of society."

A mother and a grandmother take care of a child in Beijing on Jan. 1, 2016. Married couples in China in 2016, were allowed to have two children, after concerns over an aging population and shrinking workforce ushered in an end to the country's controversial one-child policy. Fred Dufour/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Her son is part of the last generation of children in China whose births were ruled illegal at the time. Anxious that rapid population growth would strain the country's welfare systems and state-planned economy, the Chinese state began limiting how many children families could have in the late 1970s.

The limit in most cases was just one child. Then in 2016, the state allowed two children. And in May, after a new census showed the birth rate had slowed, China raised the cap to three children. State media celebrated the news.

But the legacy of the one-child rule is still painfully felt by many parents who suffered for having multiple children. For some, the pain is still too much to bear.

"It has been so many years, and I have let the pain go," the mother of three says, eyes downcast. "If you carry it with you all the time, it gets too tiring."

A mother's quandary

One night in August 2008, the mother made a fateful decision. Her body was giving her all the telltale signs that she was pregnant — again.

She already had two children and had gone through four abortions afterward, to avoid paying the ruinously high "social maintenance fee" demanded from families as penalty when they contravened birth limits.

Medical staff massage babies at an infant care center in Yongquan, in Chongqing municipality, in southwest China, on Dec. 15, 2016. China had 1 million more births in 2016 than in 2015, following the end of the one-child policy. AFP via Getty Images hide caption

But this time she felt differently.

"I had already had two children but my heart just did not feel right," says the woman, now in her 50s, who works part time in a canning factory. NPR isn't using her name to protect her identity because of the trauma she suffered. "I thought this is it — if I do not have this child, my body will not be able to have any more."

Officials in her village were actively policing families under the one-child policy. Enforcement of the policy had begun to loosen by the early 2000s, as horrific stories of forced abortions and botched sterilizations caused policymakers to rethink the rule. But starting in 2005, the authorities began enforcing the policy with a renewed ferocity in Linyi.

So the mother went into hiding to carry her son to term. One night, family planning officials approached her husband, intending to pressure him and his wife into ending the pregnancy. He used a pickax to drive them off and was imprisoned for that for half a year.

An old friend of hers, the blind lawyer Chen Guangcheng , knows full well what she and tens of thousands of other women in Linyi city went through.

Chinese parents, who have children born outside the country's one-child policy, protest outside the family planning commission in an attempt to have their fines canceled in Beijing, on Jan. 5, 2016. For decades, China's family planning policy limited most urban couples to one child and rural couples to two if their first was a girl. Ng Han Guan/AP hide caption

"The doctors would inject poison directly into the baby's skull to kill it," Chen says, drawing on recordings he made of interviews with hundreds of women and their families in Linyi. "Other doctors would artificially induce labor. But some babies were alive when they were born and began crying. The doctors strangled or drowned those babies."

The terror of such enforcement of birth limits was widespread in Linyi, even if residents were not themselves planning on giving birth.

"Officials would kidnap you if you tried to have two children. If you were hiding and they could not find you, they would kidnap your elder relatives and make them stand in cold water, in the winter," remembers Lu Bilun, a resident.

Lu says the harassment became so savage that elderly residents of Linyi became afraid to leave their homes out of fear they might be kidnapped. Lu says he paid a 4,000 yuan fine to have his second son in 2006 (about $500 at the time), after hiding his wife for months. "This was not your average level of policy enforcement. It was vicious," he says.

Chen, the lawyer, mounted a class action lawsuit on behalf of Linyi's women. The suit led to an apology from the authorities in Linyi and a reduction in the kidnappings, beatings and forced abortions.

Children ride a toy train at a shopping mall in Beijing, on Oct. 30, 2015. China's decision to abolish its one-child policy offered some relief to couples and to sellers of baby-related goods, but the government hasn't lifted birth limits entirely. Andy Wong/AP hide caption

But the Chinese government punished Chen for his activism by imprisoning him, then trapping him for nearly three years in his home , in a village just outside Linyi.

In 2012, Chen escaped by scaling a wall and running to the next village, despite being blind and having broken his foot during the escape. There, he was picked up by supporters and driven to the U.S. Embassy in Beijing. He was able to fly to the U.S . after weeks of tense negotiation. Today, he lives in Maryland with his family.

The price of defiance

"The policy was wrong and what we did with Chen was right," says a neighbor of Chen, the lawyer who sued the city of Linyi. The man wants to remain unnamed because he believes he could be harassed again for speaking of that time.

In the 1990s, he says, family planning officials ambushed him in his home at night and beat him with sticks in an effort to convince his wife to abort their third son.

Chinese lawyer Chen Guangcheng attends a rally to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre June 4, 2019, at the West Lawn of the U.S. Capitol. Chen had been persecuted and detained in China after his work advising villagers and speaking out official abuses under the one-child rule. Alex Wong/Getty Images hide caption

"Our country's leaders did not want us to have children and I didn't know why, but we could not do anything about it," he sighs.

He and his wife persevered and had three sons. They did not officially register the last two to avoid paying a fine, but the father says he still paid a bribe to family planning officials to avoid further harassment. These economic penalties depleted his life savings, a financial impact that compounded over the ensuing years.

The policy permeates through Chinese society in other, sometimes unexpected ways. Because many prioritized having a son over a daughter, orphanages experienced a surge in baby girls who were abandoned or put up for adoption. Single's Day, China's biggest online shopping holiday — akin to Black Friday in the U.S. — is a recognition of the many bachelors who are unable to find partners in a gender-skewed society.

"A very unbalanced population gender-wise has also led to a rise in property prices in major cities because families of men have bought apartments to make their sons eligible in a marriage market where there are millions of missing women," says Mei Fong , who wrote a book on the one-child rule. "These effects will be felt in the generation ahead."

A child walks near government propaganda one of which reads "1.3 billion people united" on the streets of Beijing, China, Tuesday, March 8, 2016. Ng Han Guan/AP hide caption

According to the census conducted last year, the population is aging and there are fewer young children and working-age people, a major demographic shift that comes with its own economic strains. That's pushing policymakers to consider raising the official retirement age — currently 60 for men and 55 for women — for the first time in 40 years.

Yet the authorities still only allow couples to have three children. Why won't China remove all caps?

"Despite all the overwhelming demographic evidence, they're saying, 'We need to control you,'" says the author, Fong. Anxious about already strained public education and health care systems, China's leadership is reportedly considering ditching limits entirely. It has been slow to completely dismantle its massive family planning bureaucracy built up over the past four decades. And according to an Associated Press investigation , it continues to impose stricter controls over births — including forced sterilizations — among ethnic minorities, like the Turkic Uyghurs.

Some demographers in China argue that instituting birth limits was necessary for keeping birth rates low. But Stuart Gietel-Basten, a demographer at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, cautions there is no definitive answer. "There is only one China and there is only one one-child policy, so it is kind of impossible to say the real effect of that was [of the policy]," he says.

Families were already having fewer children in the 1970s, before the policy took force in 1979. "The one-child policy was not the only thing that happened in China in the 1980s and 1990s," Gietel-Basten says. "There was also rapid urbanization, economic growth, industrialization, female emancipation and more female labor force participation."

A man and a child are reflected on a glass panel displaying a tiger at the Museum of Natural History in Beijing, Dec. 2, 2016. Andy Wong/AP hide caption

It was worth the cost

The fact that the children are alive at all makes Chen, the lawyer, feel his seven years in prison and house arrest were all worth it.

"I really feel happy. Even if I had to go to prison and endure beatings, in the end, these children were able to survive. They must be in middle school or high school by now."

The mother of one of these middle schoolers holds her son close. Part of the reason she demurred when first speaking to NPR was because of how dearly her family fought for his birth.

Her worries these days are more mundane. She wants to start preparing for her son's marriage — a costly endeavor as rural families expect the husband to provide a material guarantee for any future wife.

"That requires buying them a car, an apartment. No one can afford that," she complains.

Her job at a nearby canning factory refuses to hire her full time, she says, because she is a mother of three and needs to leave every afternoon to pick up her son from school.

And so, ironically, now that people are allowed to have more children, they are increasingly reluctant to, because of the high cost of child care and education.

"Women have it all figured out now — they won't have more kids even when they're told to have more!" the mother laughs helplessly.

"People act in funny ways," she says. "There is no point in controlling them."

- Chinese population

- Chinese law

- Chinese society

- one-child policy

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

One Child Policy, Essay Example

Pages: 6

Words: 1728

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

In the early 20 th century, Chinese government was baffled about the fast rate at which the population was growing. The one child policy was enacted in 1979 and is currently in effect. The policy is enforced through incentives such as health care, educational opportunities, job and housing opportunities, and disincentives for violators of the policy. Violators face fines, loss of educational access, and other privileges. Nonetheless, the policy has never been uniformly enforced throughout China. Initially, the goal of this policy was to ensure that the Chinese population remained under 1.2 billion. This goal was intended to be met by promotion of contraception and forced sterilizations. After carefully examining the risks and benefits China’s one child policy, it is believed that a new two-child approach is the best alternative for the future of China.

The one child policy has caused negative demographic consequences. The one child policy had estimated that China’s population would be reduced by more than 300 million in the first twenty years (Mosher, 2006). Although it has decreased the population, it has created a high sex imbalance with males unequally outnumbering females. The one child policy has also been linked to sex-selective abortions, infanticide, and other social safety problems. There are many speculations about what is happening to the girls in Chinese society. For example,

“Medical advancements and technology have played a key role in creating this surplus of boys. The Chinese government contracted with GE to provide cart-mounted ultrasound that could be run on generators so that the most obscure village had access to fetal sex determination. Given the ability to know the sex of their unborn children, many parents aborted female fetuses. Sadly, such abortions do not account for all of the missing girls in China” (Short, 2000).

Many regulations attempt to guard against sex determination abortion, but evidence shows that there has been an increase in the use of ultrasound B machines, which determines the sex of fetuses (Short, 2000). The use of ultrasound technology for abortion purposes is illegal, but it is speculated that sex selected abortions account for the great decline in female births (Wan, Fan, & Lin, 1994). In rural areas, many families simply hide their female children or give them to nearby families in order to avoid reporting the births. Sadly, some girls are just abandoned and left to die (Zilberberg, 2007).

There are several negative side effects of the one-child policy. China does not have a national social security plan. Taking care of the older generations will fall upon the one-child generation. Persons over the age of 65 currently make up about 25 percent of the population. Consequently, a one child will be responsible for taking care of four grandparents and two parents. This has become known as the “4:2:1 problem”. Another negative consequence is what has grown to be called the “Little Emperor Syndrome”, which discusses the psychological effects the one-child policy has on the children. These children have been called the spoiled generation because they are doted by parents and grandparents. The rise in childhood obesity has been linked to this syndrome. One in every five Chinese children is obese (Zhan, 2004). China has been traditionally known for great health and dietary practices. A final consequence of the one-child policy has been the difficulty of men to find a woman to marry. A direct result of this scenario is the increase in trade and sell of kidnapped women. To date, about 110,000 have been freed during crackdowns by Chinese government in Vietnamese and North Korea. It is believed that this increase in sex ratio imbalance will lead to the increase in sex related crimes and violence (Fong, 2002).

There are several steps that the Chinese government can take to remedy the many problems that the one-child policy has created. One immediate remedy would be the elimination of the use of the ultrasound B machine to determine fetuses’ sex before birth. This would eliminate mothers aborting female children. Another remedy for the problem is to relax or eliminate the one-child policy. Relaxing the policy would allow families in certain areas to have more than one child to help balance the sex ratio. In other words, in areas where men greatly outnumber women, parents would be able to have more than one child. Yet, eliminating the policy could possibly fix the problem. This would allow nature to take its course and over time the problem would be eliminated. Finally, enacting a two-child policy would help increase the decreasing female population. There is no quick remedy that will fix this problem overnight for the Chinese countries. When couples are allowed to have two children, it might discourage them from discriminating against female babies (Fong, 2002). A two child policy will allow will double the birth rate and close the gap of children to parent to grandparent gap. This will take time and will require some drastic changes in the way Chinese society views females. Through education, women will continue to fight for equality and hopefully, parents will one day value female children just as much as they value male children. Finally, an incentive program could be implemented. First time parents who have a female child could be given some type of monetary incentives and allowed to have a second child. However, the second child will not receive the monetary incentive regardless to its sex. However, if the parents have a boy the first time and a girl the second time, they could still receive the monetary incentive. This would encourage a balance between the sexes and parents would not prefer one sex over the other.

Stories of forced abortions and sterilizations are common in China. For example,

“Enforcement of the one-child policy during the early 1980s was controversial not only in China but around the globe. Early stories emerging from the rural villages focused on coercive practices, including forced late-term abortions and involuntary sterilization, as well as the “neighborly” snitching on pregnant couples who dared to conceive a second child. Backlash in rural communities throughout China prompted the government to modify the rule in the mid-1980s, allowing a second child in families whose first child was either a girl or disabled” (Liu, Wyshak, and Larsen, 2004).

Many have accused the Chinese government performing forced abortions on women who were past the abortion cut off limit. Many of the forced abortions are carried out on unmarried women. The family is the basic unit of society and shapes the individual’s behaviors and ideology. Ones interaction and time spent with siblings produce memories that last a life time. Lack of this connection will definitely affect the dynamics of family life. Much research has been done to determine how sibling structure, or the lack of structure, affects individuals in adulthood. China is under the direct influence of Confucian ideology, which teaches that a person’s life is continued through his family. According to this ideology, when a person dies, his spirit and blood remain in the word within his offspring. Traditionally, Chinese families desire large families and emphasis male dominance. Consequently, gender inequality is deep rooted in Chinese culture. Males are expected to fulfill filial duty by inheriting their parents’ estates and performing religious ceremonies. China, along with many other societies, constrains women to the home. Men are the primary source of income for their families (Wong, 1997). Women were not considered as descendants, so they were not given the same opportunities for education and other privileges as males were. Consequently, Chinese society has produced women who are not well equipped to operate society. However, under the one child policy, women are being given opportunities they have never had before. According to data, these girls are receiving education that is equivalent to boys and they are inheriting estates of their families (Liu, Wyshak, & Larsen, 2004). Nonetheless, for the few females that are able to reach such a status, there are countless others who were aborted and abandoned.

Mental and emotional health are issues that are commonly ignored in Chinese society because disclosure of personal problems publicly has been frowned upon for years. Consequently, data on the mental health of adolescents is very scarce. However, in recent years studies have emerged documenting mental issues that children of the one child policy are encountering. A study was conducted on 266 Chinese adolescents who were products of the one child policy. The researchers used the Beck Depression Inventory and discovered that about 65 percent of the children screened meet the criteria for depressed. About 10 percent of them were in the severely depressed range. Girls were also more likely to show traits of depression than only child’s who were male (Chen, Rubin, & Li, 1995).Psychologists believe that the increased incidences of depression and anxiety can be directly linked to the increased pressure that is placed upon female only children. According to Fong, gender directly affects a person’s experience in society. This idea is based upon feminist perspective. Accordingly, females experience the world in a different manner than males do. From birth, females have been expected and taught to behave a certain way due to cultural norms. However, due to the one child policy, many women are expected to confront the unwritten rules they have been taught to live by.

Works Cited

Chen, X., Rubin, K.H., & Li, D. (1995). Depressed mood in Chinese children: Relations with school performance and family environment. J ournal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63 , 938-947.

Fong, Vanessa L. 2002. China’s One-Child Policy and the Empowerment of Urban Daughters. American Anthropologist 104 (4): 1098-1109.

Liu, J., G. Wyshak, and U. Larsen. (2004). Physical Well-Being and School Enrollment: A Comparison of Adopted and Biological Children in One-Child Families in China. Social Science and Medicine 59 : 609-623.

Mosher, S. W. (2006). Winter. China’s One-Child Policy: Twenty-Five Years Later. The Human Life Review : 76-101.

Short, S. E., M. Linmao, et al. (2000). Birth Planning and Sterilization in China. Population Studies 54 (3): 279-291.

Wan, C., C. Fan, and G. Lin. (1994). A Comparative Study of Certain Differences inIndividuality and Sex-Based Differences Between 5- And 7-Years Old Only Children andNon Only Children. Acta Psychological Sinica 16 : 383-391.

Wong, Y. L. R. (1997). Dispersing the ‘Public’ and the ‘Private’: Gender and the State in the Birth Planning Policy of China. Gender and Society 11 (4): 509-525.

Zhan, H. J. 2004. “Socialization or Social Structure: Investigating Predictors of Attitudes Toward

Filial Responsibility Among Chinese Urban Youth From One and Multiple ChildFamilies.” International Journal of Aging and Human

Zilberberg, J. (2007). Sex Selection and Restricting Abortion and Sex Determination. Bioethics 21 (9):517-519.

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

On Being Here and on Going Home, Essay Example

Pell Grants, Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

Cookie settings

These necessary cookies are required to activate the core functionality of the website. An opt-out from these technologies is not available.

In order to further improve our offer and our website, we collect anonymous data for statistics and analyses. With the help of these cookies we can, for example, determine the number of visitors and the effect of certain pages on our website and optimize our content.

Selecting your areas of interest helps us to better understand our audience.

- Subject areas

How does the one child policy impact social and economic outcomes?

A strict policy on fertility affects every aspect of economic life

National University of Singapore, Singapore, and IZA, Germany

Elevator pitch

The 20th century witnessed the birth of modern family planning and its effects on the fertility of hundreds of millions of couples around the world. In 1979, China formally initiated one of the world’s strictest family planning programs—the “one child policy.” Despite its obvious significance, the policy has been significantly understudied. Data limitations and a lack of detailed documentation have hindered researchers. However, it appears clear that the policy has affected China’s economy and society in ways that extend well beyond its fertility rate.

Key findings

Due to large variation in how the one child policy was implemented across regions and ethnicities, researchers are able to exploit natural variation in their analyses, which makes empirical results reliable.

Strictness of policy implementation is associated with promotion incentives for local leaders.

The one child policy significantly curbed population growth, though there is no consensus on the magnitude.

Under the policy, households tried to have additional children without breaking the law; some unintended consequences include higher reported rates of twin births and more Han-minority marriages.

There is no solid evidence that the one child policy contributed to human capital accumulation through the traditional “quantity–quality” trade-off channel.

Current economic studies mainly focus on short-term effects, while the long-term or lagged effects are substantially understudied; thus, statements about consequences and suggestions for policy designs are still missing.

The one child policy is associated with significant problems, such as an unbalanced sex ratio, increased crime, and individual dissatisfaction toward the government.

Author's main message

China’s one child policy is possibly the largest social experiment in the history of the human race. The behavior responses to the policy offer important insights for other studies in labor, development, and public economics. To date, researchers have found that a series of outcomes, such as a lower fertility rate, an unbalanced sex ratio at birth, and higher human capital, are potentially associated with the policy. However, the answers to many important questions are far from satisfactory, and some (e.g. the long-term effects on lifecycle outcomes) have received little attention.

The 20th century included the inception of modern family planning, which restricted the fertility of hundreds of millions of couples around the world. Due to concerns about the world’s unprecedented rate of population growth in the mid-20th century, some aid agencies and international organizations began to support the establishment of family planning programs. About 40 years later, in the mid-1990s, large-scale family planning programs were active in 115 countries.

China’s “one child policy” (OCP) is the largest among the world’s family planning programs. In the 1970s, after two decades of explicitly encouraging population growth, policymakers in China began enacting a series of measures to curb it. The OCP was formally initiated in 1979 and firmly established across the country in 1980. It was the first time that family planning policy became formal law in China. Differing from birth control policies in many other countries, the OCP assigned a compulsory general “one-birth” quota to each couple, though its implementation has varied considerably across regions for different ethnicities at different times. The policy affected millions of couples and lasted more than 30 years. According to the World Bank, the fertility rate in China dropped from 2.81 in 1979 to 1.51 in 2000. The reduced fertility rate is likely to have affected the Chinese labor market profoundly.

Despite its grand scope, due to data limitations, the literature on the OCP is relatively small. This article reviews some of the recent studies on the topic, with a focus on the policy’s potential social and economic consequences, including consequences related to fertility, sex ratios, and education, as well as individual behavior responses, such as changes to reported twin births and interethnic marriages. By comparing the results of the existing literature and ongoing studies in China to those in other countries, it appears that the OCP has had a large and persistent impact on many aspects of society. Investigating these impacts may shed light on related issues in other realms of research, such as economics, demographics, and sociology.

Discussion of pros and cons

Variations in ocp implementation.

In 1979, the Chinese government formally initiated the OCP to alleviate social, economic, and environmental problems such as the high unemployment rate and scarcity of land resources. In recognition of diverse demographic and socio-economic conditions across China, the central government issued “Document 11” in February 1982 which allowed provincial governments to issue specific and locally adjusted regulations. Two years later, the central government issued “Document 7” which further stipulated that regulations regarding birth control were to be made in accordance with local conditions and were to be approved by the provincial Standing Committee of the People’s Congress and provincial-level governments. This document devolved responsibility from the central government to the local and provincial governments.

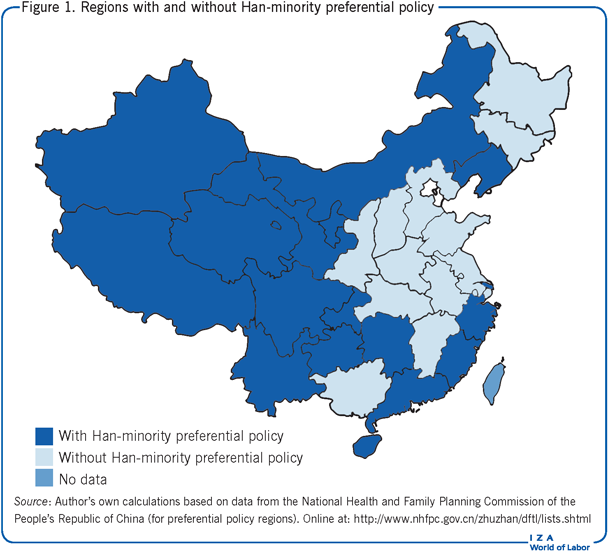

As opposed to many family planning policies in other countries, the OCP was compulsory rather than voluntary. As the name suggests, the policy restricted a couple to having only one child. However, there were some exemptions. The birth quota varied according to residence (urban/rural) and ethnicity (Han/non-Han). Since Han ethnicity is by far the largest in China, accounting for 93% of the population, the policy mainly restricted the fertility of people with Han ethnicity. In general, Han households in urban regions were only allowed to have one child, while most households in rural areas could have a second child if their first was female (this exception is called the “one-and-a-half-child policy”). Meanwhile, in most regions, households of non-Han ethnicity were allowed to have two or three children, regardless of gender.

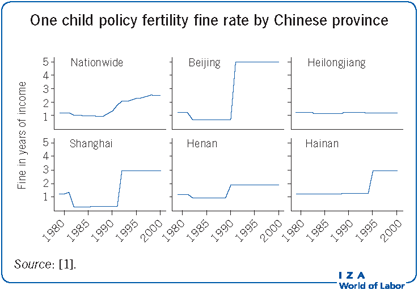

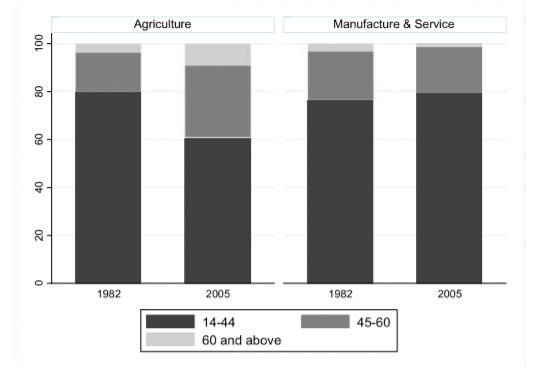

A frequently used measure in studies of the OCP is the average monetary penalty rate for one unauthorized birth in the province-year from 1979 to 2000. The OCP regulatory fine (which is called the “social child-raising fee” in China, and for brevity is referred to as the “policy fine” in this article) is formulated in multiples of annual income. Though the monetary penalty is only one aspect of the policy, and the government may take other administrative actions (e.g. loss of party membership or employment), it is still a good proxy for the policy because an increase in fines is usually associated with other stricter policies. The Illustration shows the pattern of policy fines from 1980 to 2000 in selected provinces and nationwide.

At the very beginning of the OCP, Vice Premier Muhua Chen proposed that it would be necessary to pass new legislation imposing penalties on unauthorized births. However, subnational leaders faced practical difficulties in collecting penalties in addition to resistance and complaints from the populace. For example, Guangdong province received more than 5,000 letters complaining about the implementation of the OCP in 1984. In response, the central government fully authorized the provincial governments to determine their own “tax rates” for excessive births with the issuance of Document 7 in 1984. Because local governments were more concerned about social stability than the central government, they had little incentive to design a high penalty rate. Consistent with the Illustration , some local governments even lowered penalty rates after 1984, and, until 1989, there were few changes in fertility penalties.

A major change in fine rates occurred at the end of the 1980s though, when the central government linked the success of fertility control to promotions for local officials. As stated in the book Governing China’s Population : “Addressing governors in spring 1989 Li Peng (current premier) said that population remained in a race with grain, the outcome of which would affect the survival of the Chinese race. To achieve subnational compliance, policy must be supplemented with more detailed management by objectives (ME 890406). At a meeting on birth policy in the premier’s office, Li Peng explained that such targets should be ‘evaluative’” [2] .

In March 1991, to show resoluteness, the central government listed family planning among the three basic state policies in China’s Eighth Five-Year Plan passed by the National People’s Council. The Eighth Five-Year Plan explicitly set a goal of reducing the natural growth rate of the country’s population to less than 1.25% on average during the following decade. To achieve such a challenging objective, national leaders employed a “responsibility system” to induce subnational or provincial officials to set high fine rates.

During the short period between 1989 and 1992, over half of the country’s provinces (16 out of 30) saw a significant increase in their fine rate, with the average rate increasing from 1.0 to 2.8 times a household’s yearly income. Indeed, 16 of the 21 significant increases in the policy’s history (i.e. increases of more than one times a household’s income) occurred during this period.

There is a strong correlation between increases in fine rates and the incidence of government successions. Among the 16 significant increases, 12 happened during the first two years of new provincial governors’ tenures. Governors who instituted fine increases had higher chances of being promoted than their peers, and several rose to significant heights within the central government. In addition, provincial governors who increased fertility fines tended to be younger. The average age of these 16 provincial governors was 56, which was significantly lower than the average age of other provincial governors (59 years). These numbers suggest that the promotion incentive for provincial governors could be a major driving force for the changes in fertility fines. This is also consistent with the premise that the incentive to raise fine rates depends on a governor’s personal characteristics, such as inauguration time and age.

The amount collected via the policy fine was not made public until recently: the total was about 20 billion RMB yuan (US$ 3.3 billion) among 24 provinces that reported fine rates in 2012. For example, Guangdong, one of the richest provinces in China, collected 1.5 billion yuan in 2012. Meanwhile, as a comparison, total local government expenditure on compulsory schooling in the province was 10.5 billion.

Empirical approaches to identify the effects of the OCP

A recent review of the literature summarizes four empirical approaches to identify the effects of the OCP [3] .

The first approach uses the initial year of the policy, 1979, as a cutoff and compares the birth behaviors of women before and after implementation of the OCP. Under this approach, observations before 1979 form the control group and those after 1979 the treatment group. In general, this approach assumes there would be no change in the outcome variable (e.g. birth rate) after 1979 if there was no fertility restriction.

The second approach compares the outcomes of Han Chinese and minorities before and after policy implementation in a difference-in-differences framework. Under this approach, minorities are used as the control group and Han people as the treatment group. This methodology requires that the changes in outcome variables of Han and minorities be the same without the OCP and assumes that minorities’ outcomes are not affected by the OCP. However, this requires a case-by-case analysis and one needs to be careful when drawing causal interpretations. For example, because Han-minority couples are allowed to give birth to a second child in certain regions (as shown in Figure 1 ), Han people have stronger incentives to marry minorities to obtain the extra birth quota. One direct consequence is a higher Han-minority marriage rate in regions with this preferential policy, as shown in Figure 2 .

The third approach exploits the cross-sectional and temporal variations on fines for an illegal birth. As noted before, the fines change over time; it is thus plausible to exploit these variations to identify the effects of the fines. Unfortunately, there is no formal or accurate documentation for why the fines change. Furthermore, these changes may only reflect one aspect of the policy’s effects. Therefore, further justification is required to validate the use of fines as the main independent variable.

The fourth approach explores variation between the intensity of OCP implementation across different regions in combination with the differential length of exposure of different birth cohorts to the OCP. Specifically, this approach constructs a measure based on excess births to Han women over and above the one child rule in each region while controlling for pre-existing fertility and community socio-economic status. However, as noted in one recent study, this approach relies on the strong assumption that any unobserved region-specific shocks to fertility or other family outcomes over time are uncorrelated with the cross-sectional measure of the OCP enforcement intensity [3] .

It should be noted that these four approaches are not exclusive. Some ongoing projects are employing several of them at once. Given that official documentation on the policy is limited, researchers are likely to develop more empirical approaches in the future to address the current issues, such as data limitations, and gain a more complete understanding of the OCP.

Effects of the OCP on fertility and the sex ratio

Since the primary goal of the OCP was to restrict population growth, the first question to ask is whether it has been successful in this respect. The answer is generally yes, though the magnitude of its success varies according to different studies.

Some early studies investigated how fertility responded to the policy’s restrictions [4] . Their findings are consistent, in general. For example, it was found that a one standard deviation increase in the prevalence of contraceptives led to a 0.5 standard deviation decrease in the total fertility rate.

However, the findings in the more recent literature are mixed. For instance, one study used improved measures of policy to suggest that if earlier family planning policies had not been replaced by the OCP, fertility would still have declined below the replacement level, and that the additional effects of the OCP were fairly limited [5] . By contrast, a study from 2011 used two rounds of the Chinese Population Census and found that the OCP has had a large negative effect on fertility; the average effect on post-treatment cohorts’ probability of having a second child is as large as -11 percentage points [6] . Therefore, while scholars tend to agree that the OCP has had significant effects on fertility, determining the magnitude of these effects remains an important and unanswered question.

Another demographic outcome commonly investigated in the literature is sex ratio. Incidentally correlated with the introduction of the OCP, the sex ratio at birth (i.e. males to females) increased by 0.2 over the course of 25 years, from 0.95 in 1980 to 1.15 in 2005. This phenomenon has been termed “missing women” by Amartya Sen. Since there is a strong preference for male children in China, restrictions have led to parents selecting to have/not have a child based on the results of ultrasonography technology [7] . Because parents have been able to choose abortion instead of having a girl, many researchers argue that the OCP has contributed to the high sex ratio in China. One study exploited the regional and temporal variation in fines levied for unauthorized births and found that higher fine regimes are associated with higher ratios of males to females [1] . The results are especially true for the second or third births: a 100% increase in the fine rate is associated with a 0.8 and 2.3 percentage point increase in the probability of having a male child in the second and third births, respectively. One of the previously mentioned studies used a different methodology, but reached a similar finding [6] . The study suggests that the effect of the OCP accounts for about 57% and 54% of the total increase in sex ratios for the 1991–2000 and 2001–2005 birth cohorts, respectively.

The imbalanced sex ratio may help to explain some puzzling phenomena in China, such as a high saving rate. In turn, this can be viewed as a possible consequence of the OCP. For example, one study found that as the sex ratio rises, Chinese parents with a son increase their savings rate in order to improve their son’s relative attractiveness for marriage [8] . They find that the increase in the sex ratio from 1990 to 2007 can explain about 60% of the actual increase in the household savings rate during the same period.

Furthermore, the imbalanced sex ratio may lead to other serious social consequences, including increased crime. One study used the exogenous variation in sex ratio caused by the OCP to see its effect on crime and found an elasticity of crime with respect to the sex ratio of 16- to 25-year-olds of 3.4, suggesting that male sex ratios can account for one-seventh of the rise in crime [7] . The study proposes that one possible mechanism for this increase could be the adverse marriage market due to the unbalanced sex ratio.

Effects of the OCP on human capital accumulation

One established relationship between fertility and human capital accumulation is the child quantity–quality trade-off. However, many empirical economists have examined the relationship in the case of China and found mixed evidence. The OCP used birth quotas to control population growth. As such, it provides a potential external shock to the size of families and thus enables one to study causality between family size and children’s education.

One analysis used the plausibly exogenous changes in family size caused by relaxations in the OCP to estimate the effect of the number of children in a family on school enrollment for the first child [9] . Surprisingly, the results show that having an additional child increased the likelihood of school enrollment of the first child by about 16 percentage points, implying the relationship between quantity and quality is not a “trade-off,” but rather “complementary.” The author provides several explanations, including greater economies of scale, enhanced permanent income, and increased labor supply of mothers.

Taking an alternate approach, another study exploited the exogenous variation in twin births in different birth orders to estimate the potential gain in human capital by policy-induced compressed family size [10] . The authors used the policy’s characteristics to tell the story: producing twins on the first birth results in an exogenous shock to family size in urban regions, whereas having twins on the second birth represents an exogenous shock to family size in rural regions because parents in these areas are already allowed to have a second child. The results show a modest but positive effect of compressed family size induced by the OCP on human capital, as measured by health and education.

The above findings suggest that the effects of the OCP on human capital are not well established when only considering the quality–quantity trade-off. For example, a study from 2010 investigated the impact of fertility policies on the socio-economic status and labor supply of women aged 15–49 years in Colombia. The results suggest that women impacted by birth control policy during their teenage years are more likely to have higher education. One possible explanation is that people are more incentivized to achieve higher education if they expect to have lower fertility. As opposed to the quality–quantity trade-off, which only affects post-policy birth cohorts, the effects from lower fertility expectations may be present among those who were born before the policy’s implementation, but grew up during its tenure. This finding calls for further examination of the OCP’s impact on human capital accumulation. This is important because it suggests another explanation for how fertility affects economic growth.

Discussion on the OCP’s effects on human capital is still ongoing. The varied findings imply that the answer to the human capital question may depend on the individuals/cohorts examined and on the model specification employed. Although it is difficult to answer whether and to what extent the OCP increased human capital, the policy itself provides plausibly exogenous variations for future studies to examine.

Effects of the OCP on other family outcomes

Other outcomes, such as divorce, labor supply, and rural-to-urban migration have received less attention in the literature, though they are investigated in a recent study [3] . The results suggest that regions with stricter fertility policy enforcement tend to have a greater likelihood of divorce, higher male labor force participation rates, and more rural-to-urban migration; however, these effects are modest. A one standard deviation increase in policy enforcement (measured by excess fertility, as mentioned in the fourth approach presented previously) leads to a 0.015 percentage point higher divorce rate, a 0.12 percentage point higher male labor force participation rate, and a 0.8 percentage point higher rural-to-urban migration rate. The results suggest that lower birth rates may have some unintended consequences that scholars and policymakers need to consider.

Another interesting phenomenon is the increased rate of twin births. When a couple is allowed one child, the only legitimate way to have two children is to give birth to twins, which is largely out of the control of the couple. For those who do not give birth to twins, an alternative is to report fake twins, that is, to register two consecutive siblings as twins. Interestingly, the rate of twin births reported in population censuses more than doubled between the late 1960s and the early 2000s, from 3.5 to 7.5 per 1,000 births. A recent study suggests that at least one-third of the increase in twins since the 1970s can be explained by the OCP [11] . Since couples can intentionally have twin births to bypass the OCP (i.e. by reporting fake twins or taking fertility drugs to have multiple births), the distribution of reported twins in China may not be random.

Limitations and gaps

One limitation of studying the impact of the OCP may be the measures employed. Because this policy was implemented essentially at once across the entire country, little variation exists in the timing. Because of this, many scholars have relied on the differential treatment of Han and minority ethnicities to evaluate the policy’s effects. However, this is not a perfect approach because different characteristics across the ethnicities may be correlated with the time trends, thereby biasing the results.

In addition, local governments usually had a “policy package” when implementing the OCP, which often included different penalties for illegal births for people from different backgrounds. For example, when an illegal birth is observed, those with party membership may lose it, and those hired by the public sector or collective firms may lose their jobs. These measures may go hand in hand with policy fines, but they are hard to quantify.

Furthermore, since the literature relates behavior response to social welfare, economists usually examine individuals’ behavioral responses to government policies to estimate the corresponding social welfare loss. However, no study has so far examined the corresponding welfare loss for fertility policies. To do this, researchers may need to build up a model and then analyze rich data sets to provide relevant empirical evidence. However, the difficulty in this regard originates from the lack of official documentation or details regarding the implementation of China’s OCP.

Finally, the current literature on the OCP mainly investigates the simultaneous or short-term effects. Specifically, it compares how individual behaviors differ before and after the implementation of the policy. However, there is little evidence on the long-term or lagged effects of the OCP. Take the study from 2010 as an example, whose results suggest that women growing up under birth restrictions may have higher socio-economic status [12] . Considering this, the lower fertility expectations resulting from the OCP may lead to higher education, and this potentially has profound and long-lasting effects on productivity and economic growth. However, this is largely unknown in the current literature.

Summary and policy advice

As the largest social experiment in human history, the OCP has restricted the fertility of millions of couples in China for more than three decades. This article has reviewed outcomes presented in the literature about the OCP, with a focus on its intended and unintended consequences, including fertility, sex ratio, human capital, twin births, and interethnic marriages. The results suggest that the policy has had large and long-lasting impacts on many aspects of both the economy and society, though debates persist on certain topics. The current findings also provide possible directions for insightful future studies.

It is hard to conclude whether the OCP has been good or bad in general. It has curbed the potentially problematic population boom in China, though researchers disagree as to how much of that should be attributed to the OCP, and it has possibly increased human capital accumulation. But, it has also brought with it problems, such as an unbalanced sex ratio, increased crime, and individual dissatisfaction toward the government. Since 2010, the government has loosened the policy restrictions. In late 2013, China’s government started the “selective two child policy.” This policy allows couples to have two children if one member of the couple has no siblings. In November 2015, the government ended the OCP and started the “universal two child policy.” Although the OCP has now been terminated, there are many important questions that have yet to be answered. Until considerable further research is done, it is difficult to extrapolate lessons from China’s experience to inform future policy decisions.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the author contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [11] .

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity . The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Wei Huang

evidence map

- show one-pager

Full citation

Data source(s), data type(s).

How can we improve IZA World of Labor? Click here to take our 5-minute survey and enter a prize draw.

One-Child Policy and Its Influence on China Essay

Introduction, background and concept of one-child policy, the effects of china’s one-child policy, populace growth, the sex ratio, rights to life, proportion of old age dependency, the future of the policy, works cited.

China’s one-tyke family strategy has affected the lives of almost a fourth of the world’s populace. The Chinese government guaranteed that it was a transient measure to move toward a little intentional family culture. Thus, we will analyze the influence of China’s one-tyke policy, its accomplishment, and recommendations. This paper will discuss why the approach was presented and how it is actualized. We will analyze the results of the arrangement about populace development, the proportion amongst men and women, and the proportion between grown-up kids and elderly guardians. Finally, we will examine the significance of the strategy in contemporary China. As China rose out of the social interruptions and monetary stagnation of the Cultural Revolution, its government dispatched market changes to revive the economy. In 1979, perceiving that populace control was vital to raise expectations for everyday comforts, the one-tyke family approach was presented (Kang and Wang 91). The one-child policy has exposed the challenges of human freedom. It is morally unsuitable to take a human life, be it by homicide, capital punishment, or premature birth. Numerous social orders acknowledged premature birth to safeguard the mental and social prosperity of the mother.

This strategy restricts family estimate, empowers a late marriage, childbearing, and the dividing of kids when second kids are allowed. Family spacing panel at neighborhood levels created immediate techniques to support the policy. However, the one-tyke principle applies to urban inhabitants and government workers (Hao 171). In rustic zones, a second child is permitted following five years, if the first is a woman. A third kid is authorized in some ethnic minorities and in remote, under-populated regions. Financial motivations for consistence, significant fines, seizure of property and loss of employment, were utilized to authorize the approach. The strategy depends on general access to contraception and premature birth. By implication, Eighty-seven for each penny of wedded women used contraception. Most women acknowledged the technique suggested by the family physician, which supported one-child policy (Hao 172). Dependence on long haul contraception kept the premature birth rate low (25 for every penny of Chinese ladies of regenerative age have had no less than one fetus removal, as contrasted 43 for each penny in the United States). Premature births are authorized when contraceptives are ineffective or when the pregnancy is not affirmed. However, Unattended and unsanctioned conveyances do happen.

In 1979, the Chinese government left with an aspiring system of business change taking after the financial stagnation of the Cultural Revolution. Sixty-six percent of the populace was under the age of 30 years, and the children of postwar America of the 1950s and 1960s were entering their regenerative years. The administration saw strict populace control as key to monetary change and a change in living standards. As a result, the Chinese government presented the one-kid family arrangement. The strategy comprises of an arrangement of directions administering the affirmed size of Chinese families. These controls incorporate limitations on family measure, late marriage, and childbearing, and the separating of kids (where second kids are allowed). Family-arranging advisory groups as common and regional levels devise immediate systems for execution. Despite its name, the one-kid principle applies to a minority of the populace; for urban occupants and government workers, the arrangement are upheld, with a couple of exemptions (Festini and de Martino 360). Special cases incorporate families in which the main kid has an inability or both guardians work in high-hazard occupations, (for example, mining) or are themselves from one-youngster families (in a few zones). In areas where 70 percent of the general population lives, a second child permitted following five years, yet this arrangement occasionally applies if the main youngster is a woman (an unmistakable affirmation of the conventional inclination for boys). The influence of China’s one-tyke policy affected the sex ratio and population growth. However, the policy increased abortion to astronomical heights.

The one-child policy is a standout amongst the most critical social approaches ever executed in China. The approach, set up in 1979, restricted couples to just having one tyke. The policy was influenced by China’s amazingly vast populace development, which was seen as a danger to the nation’s future monetary development and expectations for everyday comforts of the general population (Festini and de Martino 359). At the season of being actualized, China’s populace was around 970 million (Festini and de Martino 360), thus, it was the Chinese government’s objective to enforce populace development to keep the aggregate populace focused around 1.2 billion for the year 2000 (Hao 170). China’s aggregate populace was around 1.26 billion in 2000 (Hu 5), so the objective was accomplished, yet maybe was marginally higher than what the legislature estimated. For the arrangement to be effectively executed, the administration presented motivating forces so that the populace would follow the directions.

These impetuses have been monetary, including duties and fines for the individuals who do not go with the policy. For instance, families have favored access to lodging, social insurance and instruction (Festini and de Martino 368). There have been both positive and negative effects connected with the one-tyke policy in China. It has been effective in avoiding between 250 million and 300 million births (Festini and de Martino 370), and in addition, diminishing the aggregate ripeness rate (TFR) from 2.7 youngsters for every woman in 1980 to 1.7 in 2011 (Festini and de Martino 369). This figure in TFR has prompted the diminishing of the aggregate populace of China accordingly dodging a populace blast, keeping up monetary development, and enhancing expectation of everyday comforts. Nonetheless, there are worries that the current TFR that is underneath the substitution level of 2.1 may bring a different demographic circumstance. This low TFR may decrease to lower level, potentially prompting a populace decrease that supports ‘minimal low’ richness (TFR of 1.3 or beneath). By implication, there will be an absence of individuals in the working age populace and the prospect of a maturing populace (Kang and Wang 91). This would influence the reliance proportion of the nation and put gigantic weight on the administration to give monetary and social backing to the elderly populace.

A standout amongst the impacts of the one child policy has been China’s sex proportion and the “missing young ladies” marvel. China has encountered a skewed sex proportion for quite a while, before tyke policy was presented. This issue has been exacerbated subsequent to the presentation of the approach. In China, having male kids is favored over girls. This inclination is particularly present in rustic territories because male children are in charge of supporting relatives once they have achieved maturity. As a result, the child inclination has prompted an expanded skew in the sex proportion during childbirth. Prior to the strategy in 1979, the sex proportion was 115 boys per 96 girls marginally higher than the world sex proportion of 109 boys per 90 females. The amazingly skewed sex proportion in China has prompted the “missing young ladies” wonder, which means many young women are “lost” from China’s populace registers. There are four fundamental clarifications for this: female child murder, disregard, or relinquishment; underreporting of female births; reception of female kids; and sex-particular premature births (Riley 34). Abortion, which is the primary driver of China’s sex proportion, was an aftereffect of the policy. Through the presentation of ultrasound machines in the mid-1980s, Chinese couples could illicitly discover the sex of their tyke and after that could complete a fetus removal if their first kid was a female, making it workable for them to have a child (Kaiman14).

Lately, there have been arrangements with the Chinese government to unwind the policy. Notwithstanding, there is levelheaded discussion whether this will make a populace blast inside China. The monetary weight of having a kid has deflected numerous couples from having a second tyke; subsequently this unwinding of the arrangement might not affect the populace development of China. Consequently, numerous couples from provincial regions will probably have a second tyke as they depend more on their sons to bolster the family. There could even be a plausibility of the policy being suspended by 2020 (Kaiman14), however this will rely on upon future demographic patterns and if the legislature will surrender one of the greatest strategies ever presented in China.