- Become a member

- The Montessori Event

- AMS Learning

- Administration

- Early Childhood

- Global Initiatives

- Infant & Toddler

- Professional Development

- Public Policy

- Public Schools

- Special Needs

- Toggle Search

Growing Up Gay

Montessori life, summer 2017, by geoffrey bishop and mirko sever, a baby boomer voice: geoffrey bishop.

I grew up in the 1960s and 1970s in Australia, a country that was itself coming out of the closet, although the closet was heavily fortified and for a long time quite impenetrable when it came to its acceptance of gay people. Growing up gay is very different from growing up straight; your sexuality defines you in a larger way. The sexuality of straight children is not dwelt upon to the same degree, because straight is “normal.” It is what you see every day: your parents, people on TV, your teachers, and the majority of the people around you. On the other hand, growing up gay starts with a small seed, a feeling that you do not understand, and an attraction to the same sex you at first think is normal. Soon, however, you discover the meaning and the reality of this attraction—that being gay is something you should be ashamed of, and, from a religious perspective, something seen as evil. And from the moment of that discovery, this awareness and what you are hiding start to define, and even take over, your whole being.

I knew I was gay from a very young age, probably 7 or 8, or even earlier, though I didn’t know the word gay. At that time, the word poofta (or poofter) was a commonly used Australian term for a gay male. I understood that in some ways this term meant me. I was also very aware that, for many people, being gay was akin to being a prostitute or being immoral. It was also very clear to me that being gay only meant sex; it had nothing to do with love, as I had no gay role models and I had never met a gay person.

At age 11, I left home to attend an all-boys boarding school. This saved me but also drove me deeper into the darkness of the closet. It saved me because it opened a whole world that I did not know about, exposing me to students from all over the South Pacific, along with cultures and ideas that were not available during my life on a sheep station. It also opened a door to a darker side; I was so terrified of being outed that I sometimes acted as the loudest bully toward others suspected of being gay. Every day I wore a mask to hide who I really was. This inner battle became a daily struggle: Deep down, I knew that everything about the way in which I presented my identity was a lie. When I had crushes on other boys, I had to keep them hidden, unfulfilled, when all around me, peers were getting so excited about romance and love. All I could do is dream that one day I would have friends who would be happy when I had my first boyfriend.

My experience was a long time ago, and though much has changed in the world, not much is different for many young people who are trying to define who they are. Many adults presume that every child is straight; for many parents, the thought that one day their child will turn to them and say, “Mom, Dad, I’m gay” is terrifying. This may be the hardest sentence a young person will ever have to utter, and, for many, it has terrifying consequences. Some gay children are lucky enough to have parents who love and support them as they come out of the closet, but, for others, it is a huge gamble, as the thoughts that echo in their mind are, What will their reaction be? Will they still love me? I wish I were normal.

It is 2017, and I still have friends who are not out at work or to family members. Even at my age, this is a treacherous road for them. To have a voice, you need to be supported, and you need to have confidence that that voice will not destroy you. This takes an enormous amount of courage that many LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer) individuals are unable to summon.

A MILLENNIAL VOICE: MIRKO SEVER

Growing up, I knew I was different, but I could not explain why. Most of my male peers were interested in soccer, Power Rangers, and girls. I was not. At a young age, I realized I was attracted to other boys, but acting on that did not come till adulthood. Growing up in a religious family, I was surrounded by images, comments, and information that contradicted what I felt inside. This was confusing and also made me feel that expressing what was inside me was a great risk. I could not relate to other boys, and, because of that, I was left out and made fun of. I felt invisible. I had no friends, so I turned to my teachers and other adults, hoping they would understand and accept me. Unfortunately, I also found them intolerant, unsupportive, and unable to see the real me. I got used to being alone.

Without anyone to confide in, my self-image took a huge beating. I constantly put myself down. I believed that since others did not see the value in me, I must not have any value to provide. Very dark thoughts entered my mind. I began to treat myself the way others treated me: with disrespect, discouragement, indifference, and carelessness. Nobody cared how I felt, no one cared how I was doing, no one cared that I needed help, and no one remembered my birthday. Feeling great anxiety about whether I was living in sin ate at me daily. I longed for nights where I didn’t have to cry myself to sleep. I longed for love without the condition of being gay.

But deep down, I knew I was here for a reason, even if I could not figure it out. I knew I had to pull myself out of the feeling of uselessness that had come over me. I began to spend all my time studying or working, in an attempt to keep my mind from focusing on the sad reality of my life. I knew that there would be light at the end of the tunnel. I believed God had a greater plan for me and that I was on Earth to make the world a better place. But I still didn’t know why I was created this way or what I could do about it.

As I pondered these thoughts, I came to understand that the world was filled with hatred—the same hatred that had been directed toward me and the same self-loathing I had developed as a result. What I had experienced was horrible; I made it my mission to ensure that no other child would have to go through it. I believe I was put through so much pain because I was strong enough to overcome it and help others overcome. Instead of remaining bitter, I chose to adopt a lifestyle of kindness.

In many of the world’s countries, being gay is punishable by death (Bearak and Cameron, June 16, 2016). And in the United States, there has been recent political opposition to gay marriage and gay rights. It is no wonder that, in today’s world, a small but important percentage of our young people grow up confused, scared, and unsupported. A CDC study found that 43% of LGB (lesbian, gay, bisexual) students in grades 9–12 had seriously considered suicide. Questioning youth attempt suicide at a rate two times greater than that of straight youth; for LGB youth, the rate is four times that of straight youth (thetrevorproject.org). In this article, we offer two perspectives on how growing up gay affected our lives and propose our thoughts on how schools and teachers can try to normalize what society often overlooks, misunderstands, ignores, or even considers to be outside the realm of reality.

I also realized that being gay is how I was born, not something I chose. I began to understand that I needed to accept myself. I needed to make myself happy.

I needed to love myself. I needed to set myself free. Once I came out to myself, I was able to do those things, and life became easier and more enjoyable. I began to love who I was and who I could be. And when I gained the courage to come out to others, I found that, for most of my friends, it made no difference. True friends love you for who you are and accept all the things that make you you.

I realized I had been trying to fit into the mold that society had created for me—the middle-class white man who excelled in school and career, and eventually met, married, and started a family with the woman of his dreams. But this wasn’t what I wanted. Attempting to conform to these standards caused me to think twice about every decision I made, every word I said, and every truth I accepted or conveyed. I came to understand that my journey wasn’t about becoming anything but rather about un-becoming everything that wasn’t really me so I could be who I was meant to be. When I began to understand myself and understand why I was to make the world a better place, I realized that I didn’t have to fit society’s mold; I could create my own. I could take the shell that surrounded me, squeezed me, and kept my wings from spreading, and I could shatter it.

Though this realization was a relief, it brought me to an extremely difficult decision: I could either continue living a lie and living in fear, or I could come out of the closet. Taking everything that provided me “comfort” for so long and destroying it provoked as much anxiety as living the lie. In the end, I decided that coming to terms with being gay was more important and more conducive to removing hatred from the world and making it a better place to live. Immediately I was able to breathe more easily. I didn’t have to think twice about what I said anymore; I could live in real truth. As a result, I created new friendships with people who loved and accepted me for who I was. These new friends cared about me. They cared enough to ask if I needed help; they cared enough to get together and celebrate my birthday. I could finally be free and feel loved. I could finally go to bed happy. All of the things I had once prayed for I was now living.

I believe that every adult in charge of children should keep these mantras in mind:

- In everything I do, I will strive to include everyone;

- I will strive to listen to those who have no one to listen to them;

- I will strive to encourage others and support their dreams and desires;

- I will strive to uplift others.

For much of my life, I knew what it was like to feel left out, ignored, and unsupported, and so I told myself if no one could be or do those things for me, I could at least do them for someone else.

What can Montessori schools do to aid LGBTQ students? The first and most important thing an adult can do is not to presume anything about a student. It is so easy for us as teachers to create an image in our heads of who we believe a child to be. But we must remember that the child is the only person who truly knows who he or she is inside, and many LGBTQ children are still working that out for themselves. Montessorians already strive to create environments designed to foster self-direction and independence. Let us also work to ensure that these environments are safe and comfortable places for children who are coming to grips with their own identities.

The media and politicians often reduce gay people to the act of sex with someone of the same gender. Sex is only one small part of who humans are, and at our schools we must broadcast that this goes for LGBTQ students and adults as well as for straight students and adults. Being gay is about loving someone of the same gender. Beyond that, gay people’s dreams, goals, and aspirations often are not distinguishable from those of straight people.

As educators, we should never assume that the parents of a gay or lesbian student who has confided in us are as open or understanding as we are. It is not our role to “out” children to their parents or to anyone else, including our peers. No one has the right to declare another’s sexuality.

We can use books and other materials to present and normalize various kinds of relationships and families. Exposure to positive and open representations of all types of families will plant seeds in even the youngest children that can support healthy relationships with their own sexuality, whatever it may be.

We should be proactive about sex education, creating programs that are reflective of and positive about LBGTQ relationships and straight relationships alike. The best sex education programs should always include parents; creating an avenue for open dialogue between parents and students can lead to healthy, mature, and well-adjusted young adults. As Montessori said, the parent is the first educator.

The statistics on LGBTQ suicides across the country are astounding, and it is such a waste of human potential. All of us have great talents and so much to give to society. Who we love is a beautiful thing and should be celebrated, not driven into the dark, creating an endless cycle of self-hatred. We all have a role to play in raising and educating children. One positive word from a teacher, one story of inclusion, or a few minutes empathically listening can save the life of an LGBTQ child. As teachers and Montessori professionals, we want to discover the inner child in our students, to see who they are as humans; along with everything else, this includes their sexuality. We are all created as individuals, with various needs, desires, and aspirations. It is through a caring community, accepting adults, and the encouragement of our peers that we are able to release our true potential. It’s up to all of us.

About the Author

GEOFFREY BISHOP is the founder of Nature’s Classroom Institute and Montessori School, a 140-acre campus in Mukwonago, WI. Contact him at [email protected] .

MIRKO SEVER is the marketing and program director for Nature’s Classroom Institute, California. Contact him at [email protected] .

Bearak, M. & Cameron, D. (2016, June 16). Here are the 10 countries where homosexuality may be punishable by death. Washington Post. Retrieved from www.washingtonpost.com .

The Trevor Project. Retrieved from www.thetrevorproject.org/blog/entry/cdc-study-reveals-lgb-youth-three-times-more-likely-to-experience-sexual-ph

AMS Recommends

Gender Diversity and Inclusivity in the Classroom

Elementary writing certificate program.

Critical Race Theory: Talking through the Confusion

Ams diversity, equity, & inclusion scholarship.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

https://www.nist.gov/blogs/taking-measure/reflections-growing-gay-and-solace-science

Taking Measure

Just a Standard Blog

Reflections on Growing Up Gay and the Solace of Science

Typical day in my lab.

I was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in the mid-’70s into a blue-collar family. My father was a carpenter and my mother was a homemaker. My family was of modest means, but we always had enough food to eat and always had a roof over our heads.

On the occasional summer weekend, my parents would scrape enough money together for us to go on a road trip to a neighboring lake town, memories I cherish to this day. My early childhood years were mostly those of a typical happy-go-lucky boy. I was usually in good spirits and I had everything that I needed. Despite that, I didn’t really fit in with my “peer” group of pre-teen boys. I didn’t like sports, I didn’t particularly care for outdoor activities, and most of my friends were girls. The few male friends I did have as a child, I would learn later in life were also gay (more on that later).

Throughout my childhood, this lack of fitting in persisted. I just didn’t want to do what other boys wanted to do. And I didn’t have this peculiar attraction to girls that other boys had. I recognized that it is was only peculiar to me. I understood what the attraction was, and I looked for it within myself. I looked a lot, but couldn’t find it.

The only place I found peace and solace was in studying, so that is what I did and did it pretty intensely. I used those pursuits to distract myself from all the pain associated with not fitting into the pre-made social machinery around me. I didn’t have to go to the weekend school dance, because I was too busy studying for the chemistry exam on the following Monday. This paid other dividends with my peers at school. Since I worked so hard to fully understand the materials, it became easy for me to explain them to other students who needed help. I had found a way to be accepted by my peers; I could be the best nerd in the class!

In high school, I was lucky enough to receive a scholarship to the University of Tulsa that covered most of my tuition costs and ultimately resulted in a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering. During my undergraduate days, I reunited with some of my elementary school friends and they introduced me to the local gay scene. There were a handful of gay bars that we would frequent, and for the first time in my life, I found a community where I was accepted and not judged. I was finally ready to come out to the world in general, and I didn’t care anymore who knew I was gay. (Before this time, I held this secret very tightly—only my closest friends knew and they were sworn to secrecy.)

After earning my degree, I was not ready to get a “real” job, since the only options that seemed available to me were entry-level corporate engineering jobs in the petrochemical industry. Sure the pay was good, but the work was not that interesting. So, I ended up applying to graduate programs across the country, ultimately deciding to attend Northwestern University. I earned a Ph.D. in the early 2000s, and that led to a National Research Council postdoctoral fellowship at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and ultimately a staff position, where I now have an amazing career and work life.

Throughout my grade-school, undergraduate and graduate education, I would hear the occasional off-color “gay” comment from peers and I had more or less grown to accept it as an unfortunate fact of life. Now, as I approach the 20th year of my career at NIST, I cannot imagine my sexuality being any part of how my peers evaluate me or my abilities; to them it is only as important as the color of the (very little) hair on my head or the color of the pigments in the irises of my eyes. That is to say, it is something that is a part of me, but it is not what defines my abilities.

It is a true asset to NIST that everybody is appreciated and acknowledged for the skills and integrity they bring to their work, while the other qualities that describe them as a person only serve to enhance their contribution to the community. We still have a long way to go in completely accepting everybody. But that little boy born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, 44 years ago, would never have imagined that our society would have progressed so much toward fully accepting the beautiful diversity that makes up our world.

About the author

Wyatt Vreeland

Wyatt Vreeland graduated magna cum laude from the University of Tulsa in May of 1997. In 1997 he began his doctoral studies at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. During his time at...

Thanks for sharing your story, Wyatt.

Beautifully written. So glad to call you my friend.

Thank you for helping make NIST (and the world) a better place and for sharing parts of your journey with us. They're lucky to have you.

Thank you, Wyatt!

Your story is an inspiration. I am so glad you have found a true home and inclusive community at NIST, where pursuit of excellence is our shared commitment.

Walt Copan NIST Director

This is a great story. Thank you for sharing it. It makes me think back of my high school days in the 1970s when people even suspected of being gay were treated unkindly. Now I wish I would have done more at the time in their defense. I've lost track of them but hope they have found the support you have including at NIST.

Thanks so much for sharing your story! I am very grateful to be your colleague and friend.

That was nice. Proud of you Wyatt!

Add new comment

- No HTML tags allowed.

- Web page addresses and email addresses turn into links automatically.

- Lines and paragraphs break automatically.

Listen Live

Get a fresh perspective of people, events and trends that shape our world. A mix of news, features, interviews and music from around the world presents an engaging portrait of the global community.

- Home & Family

The unexpected joys of learning from my younger gay brother

Traditionally, you are supposed to learn from your older siblings. however, sometimes, learning goes in the other direction..

The author is shown with his younger brother Marcus (foreground) on his 21st birthday. (Image courtesy of James Jones)

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

Brought to you by Speak Easy

Thoughtful essays, commentaries, and opinions on current events, ideas, and life in the Philadelphia region.

Part of the series

Lgbtq pride.

Through the month of June, we are asking LGBTQ readers to submit essays about experiences in their lives that have brought them pride, happiness, and triumph.

You may also like

Drag story hour at Pa. library canceled after suspicious package and threats, authorities say

A state police bomb squad later cleared the library, but police said “additional reported threats” were still being investigated.

Amid growing demand, a new bilingual child care center is opening in New Castle

With the Latino population on the rise, more families are seeking support for first-generation Spanish-speaking children.

2 weeks ago

University of Delaware junior named finalist in NPR’s College Podcast Challenge

Trinity Hunt’s podcast explores her relationship with her sister through letters and phone calls.

Want a digest of WHYY’s programs, events & stories? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Together we can reach 100% of WHYY’s fiscal year goal

- Canada Edition

- Fader Radio

Growing Up Gay Without Shame

As a kid, i embraced my femininity unquestioningly. later in life, i learned how powerful that truly was..

My stepfather said he had something he wanted to show me. I was eight years old in Houston, Texas, and I hurried to the living room couch, plopped down, and curled my legs up. The older man’s face was smug, and a smile stained the corners of his mouth as he pressed a button on the remote. Grainy footage from my final summer theater recital started playing on the television. On the screen was Ethan, one of the boys in my class. He had the kind of voice that some boys spent their lives praying for — deep and thundering, all baritone. When he finished his monologue there was a moment of silence, the camera shifted out of focus, and the sound of a higher voice wafted through the television. There was no depth that throttled its throat. The camera snapped into focus and zoomed in on me. I stood beneath the stage’s spotlight, tall and glowing, the only boy with the voice of a girl.

I realized that my stepfather wanted me to feel the same disgust with my femininity that he did. But I felt no shame, instead letting out a rib-cracking laugh and focusing on my performance. This reaction was not my stepfather’s intention — and he shook his head with contempt and rewound the footage — but I simply walked away, leaving him on the couch with a remote in his hand. My mother had taught me to remain upright and firm no matter how I felt. “Carry yourself with pride,” she’d usher anytime I was nervous. So I never had a coming out story. Unlike children who are forced to hide their true selves from their parents and friends because of fear, there was nothing that could veil who I was. I knew I identified with femininity; I knew my sexuality was as natural as breathing.

Even so, I had to contend with the cruelty of playground bullies. It began in elementary school, with taunts that my handwriting was “girlish.” The boy who criticized my writing couldn’t have paid me to entertain him, though. I watched him stutter through simple words during reading hour and never saw his name on the Accelerated Reader chart. Of course, acting in a “feminine” manner doesn’t make someone gay. But at my close-minded school, my sexuality — while always private — was visible through things like my handwriting. I learned that it didn’t stop there. Critiques of my clothing came next, followed by the way I walked, or how my hands rested on my hips.

It never weakened my resolve. When I was signed up against my will for flag football, one tackle was all it took for me to know this was a game I was not willing to play. In my world, winter scarves became bundles of hair that rivaled Pocahontas. I was an unruly child, incredibly firm and self-possessed. I did not question my interests, and through this sense of self, I allowed no one to question me . When teasing became a daily occurrence, I sometimes cried at home and always fought at school. Soon, no hand swung as fast as mine and no comeback was as stinging.

I knew I identified with femininity; I knew my sexuality was as natural as breathing.

Fights were frequent, brutal, and bloody. Once, when I went to the bathroom, a classmate emptied my backpack, chained it to a desk, and scattered its contents around the room like a treasure hunt. I grabbed a chair, crossed my legs, and took a seat in front of the door. No one left that room until my backpack was delivered to me as it once was. Another time, my high school’s Christian Coalition, a group that weaponized tenets of Christianity, surrounded me during lunch. They came to pray for me and ask the Lord for guidance. I smiled politely and then said, “Let’s pray I find a man.” Their faces burst in anger, and they never approached me again. It didn’t get better, I forged it.

I always knew the world belonged to me. How could it not? All I had to do was breathe and the world quivered. There were those who wanted me to atrophy; many still want me to. They want me to slouch my shoulders and drag my feet, to feel uncomfortable in every space. Even now, at times when I open my mouth and speak, I hear gasps or snickers. Occasionally, as I walk down the street in my new home of New York City, epithets and insults that never held weight to me are occasionally tossed my way. I do the same thing I did when I was eight. I hold my head high. I let my height and beauty glow, and I tilt back my head, giggling. And if you look carefully, down my rigidly straight spine, my hands are still flexed, ready.

10 LGBTQ memoirs to read for National Memoir Writing Month

Memoirs offer a window into the most personal aspects of a person’s life.

In their 2019 memoir “Sissy: A Coming of Gender Story,” for example, Jacob Tobia lays bare their journey, from coping with bullying to becoming a prominent nonbinary LGBTQ rights activist — a story that Showtime is developing into a series, Variety reported today .

Whether they’re written by the successful celebrities we already admire or ordinary people who’ve encountered and overcome extraordinary circumstances, memoirs remind us we are not isolated in our hopes, desires, dreams and struggles, but rather, connected. This National Memoir Writing Month, here’s a primer on some of the most notable queer memoirs from the last few years.

1. " In the Dream House: A Memoir " by Carmen Maria Machado

In the Dream House

Intimate partner violence, which can include physical, emotional and psychological abuse, affects more than 12 million people each year , according to the National Domestic Violence Hotline . Yet despite the prevalence of this serious issue, such violence remains a taboo topic. Carmen Maria Machado tackles this stigma in “ In the Dream House ,” a harrowing memoir about the abuse she endured at the hands of a partner in graduate school. While the work is technically a memoir, it also incorporates elements of romance, science fiction, westerns, etc. But the memoir’s genre-bending form is only one way in which Machado — who also penned “ Her Body and Other Parts ” — unsettles the reader in this story when it comes to reclaiming the parts of yourself that have grown most alien.

2. " Over The Top: A Raw Journey to Self-Love " by Jonathan Van Ness

Over the Top

Jonathan Van Ness rose to fame as the optimistic grooming expert on Netflix’s “Queer Eye” in 2018. Now, he’s taking readers on a journey through the triumphs and trials of his life in his vulnerable “ Over the Top .” In it, Van Ness shares the difficulties he’s overcome and still grapples with, including childhood sexual abuse, depression, drug use and an HIV-positive diagnosis . Van Ness told NBC’s TODAY Show he hopes he can make others feel less alone with his memoir. “I think it is really important for me to speak about things I talk about in this book, so I think it was the right thing to do,” he said.

3. “ A Year Without a Name: A Memoir ” by Cyrus Grace Dunham

A Year Without a Name

Cyrus Grace Dunham, Lena Dunham’s younger sibling, provides an intimate portrait of gender, queerness and desire in “ A Year Without a Name .” Dunham writes about his gender transition and the uncertainty that accompanied it. Dunham told Them that he wanted to provide an alternative story — to those often seen in “more palatable” trans narratives distributed to the public — by expressing the doubt he still grapples with post-transition.

“It felt important to me to try to communicate my ambivalence and hesitations around those themes,” Cyrus told Them. “Any time I reached a point in writing where I felt like I was better, I would just go back to a place of extreme doubt again. I think that’s something that a lot of trans people deal with.”

4. “ How We Fight for Our Lives ” by Saeed Jones

How We Fight for Our Lives

In, “ How We Fight for Our Lives ,” award-winning poet Saeed Jones writes about growing up in the South as a black, gay man and grappling with the complexities of his identity. The memoir, which was released in October, unfolds through a series of vignettes following Jones as he navigates the relationships in his life and ultimately claims ownership and autonomy of himself.

5. “ Mama’s Boy ” by Dustin Lance Black

Mama's Boy

Activist and Oscar-winning gay filmmaker Dustin Lance Black chronicles how he and his deeply conservative Mormon mother found common ground in the midst of great idealogical conflict. Black, who wrote the Oscar-winning screenplay for “ Milk ,” came out to his mother when he was 21. His mother responded that being gay was a sinful choice, but through the course of the memoir — which stretches from the steps of the Supreme Court to San Antonio, Texas — Black and his mother manage to heal their fractured relationship.

6. " Becoming Eve: My Journey from Ultra-Orthodox Rabbi to Transgender Woman " by Abby Stein

Becoming Eve

Abby Stein is thought to be the first openly transgender woman raised in a Hasidic community . Stein chronicles her experience her memoir “ Becoming Eve ,” which was released Nov. 12. Stein said she always felt different but concurrently faced pressures to keep her identity secret and to follow the more traditional path: living as a man, getting married and becoming a rabbi. In her memoir, she shares the experience of sneaking onto the internet for the very first time in 2011 in a mall bathroom. There, she discovered what the word transgender meant. In her memoir, Stein also lays out the journey of coming out to her religious family.

“At the end of the day, I am who I am today, of which I am very proud and happy and comfortable, because of the sum total of my experiences,” Stein told TODAY .

7. “ A Wild and Precious Life: A Memoir ” by Edie Windsor

A Wild and Precious Life

Edie Windsor gained international acclaim after she sued the U.S. government in an attempt to achieve federal recognition for her marriage to Thea Spyer, her partner for more than 40 years. The Supreme Court ruled in Windsor’s favor in the landmark case that paved the way for marriage equality in the U.S.

In the posthumously released “ A Wild and Precious Life ,” which Windsor began writing before she died in 2017 and which was completed by Joshua Lyon, Windsor chronicles how she became a gay icon. From participating in Greenwich Village’s underground gay scene during the 1950s to becoming a trailblazing leader at IBM, Windsor’s story fighting for what she believed in is one that will leave readers inspired.

8. “ Sissy: A Coming of Gender Story ” by Jacob Tobia

As a child, Jacob Tobia was often called a “sissy” because of their penchant for glitter and Barbies. Now, the gender nonconfirming artist has reclaimed the term in their book “ Sissy: A Coming of Gender Story .” In this candid guidebook, Tobia offers their story of transforming from a shy, closeted gender noncomforming child to a proud genderqueer activist, and, in doing so, reflects on the limitations of the gender binary. And today, Variety reported that Showtime is developing a dramedy of the same name based on the memoir.

9. " Boy Erased: A Memoir " by Garrard Conley

In “ Boy Erased ,” Garrad Conley tells a haunting account about his childhood in a fundamentalist Arkansas family that forced him to undertake conversion therapy. After Conley was outed as gay in college, he was given a choice: be disowned or go through complete conversion therapy — a practice widely discredited as ineffective and harmful by medical practioners . Conley recounts his participation in the months-long program in this 2016 memoir, with the hope of spreading awareness about the psychological warfare inflicted on those subjected to the practice. “ Boy Erased ” was adapted into a 2018 film, starring Lucas Hedges and Nicole Kidman.

10. “ Forward ” by Abby Wambach

While you wait for Megan Rapinoe to release her book, settle in with the memoir of retired U.S. soccer icon Abby Wambach. Called an inspiration and “badass” by President Obama , Wambach is not only a world-class athlete, but an activist for equal rights. In “ Forward ,” Wambach records how she went from joining an all-boy’s soccer team at age seven, to becoming the highest goal scorer — male or female — in the history of soccer by age 35.

Looking for more books to read?

- 16 must-read books for LGBTQ History Month 2019

- New children's book tells story of the 1969 Stonewall uprising

- The rise of young adult books with LGBTQ characters — and what's next

Follow NBC Out on Twitter , Facebook & Instagram .

Gwen Aviles is a trending news and culture reporter for NBC News.

Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Chapter 3: the coming out experience.

For lesbians, gay men, bisexuals and transgender people, realizing their sexual orientation or gender identity and sharing that information with family and friends is often a gradual process that can unfold over a series of years. This section looks at the process of coming out—when and how it happens, how difficult it is, and what impact it has on relationships.

This section also explores the interactions LGBT adults have outside of their circles of family and close friends—in their communities and workplaces. Some seek out neighborhoods that are predominantly LGBT, but most do not. A majority of employed LGBT adults say their workplaces are accepting of people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender. Still, about half say only a few or none of their co-workers know about their sexual orientation or gender identity.

Ultimately, these journeys are personal and hard to quantify. Survey respondents were invited to elaborate on their experiences, and many of their stories are captured in an interactive feature on the Pew Research Center website.

Interactive: LGBT Voices

Explore some 300 quotes from LGBT survey respondents about their coming out experiences.

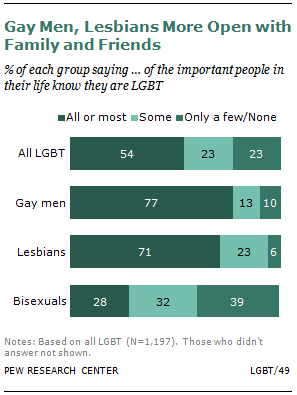

How Many of the Important People in Your Life Know?

There are large differences here across LGB groups. Lesbians and gay men are more likely than bisexuals to have told at least one close friend about their sexual orientation (96% of gay men and 94% of lesbians, compared with 79% of bisexuals). And they are much more likely to say that most of the people who are important to them know about this aspect of their life: 77% of gay men and 71% of lesbians say all or most people know, compared with 28% of bisexuals. Among bisexuals, there are large differences between men and women in the share who say the people closest to them know that they are bisexual. Roughly nine-in-ten bisexual women (88%) say they have told a close friend about their sexual orientation; only 55% of bisexual men say they have told a close friend. Similarly, while one-third of bisexual women say most of the important people in their life know they are bisexual, only 12% of bisexual men say the same. Furthermore, 65% of bisexual men say that only a few or none of the important people in their life know they are bisexual.

Among all LGBT adults, those with a college degree are more likely than those who have not graduated from college to say all or most of the important people in their life know they are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (64% vs. 49%). There are no significant differences across age groups. Similar shares of young, middle-aged and older LGBT adults say most of the important people in their life are aware of their sexual orientation or gender identity. There is an age gap among bisexuals, however, with bisexuals under the age of 45 much more likely than those ages 45 or older to say most of the important people in their life know that they are bisexual (32% and 18%, respectively).

Growing Up LGBT

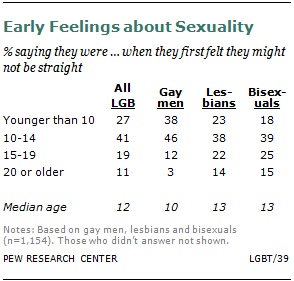

Among gay men, about four-in-ten (38%) say they were younger than 10 when they first felt they were not heterosexual. By comparison 23% of lesbians and 18% of bisexuals say they were younger than 10 when they first started to question their sexuality.

The vast majority of lesbians, gay men and bisexuals say they were in their teens or younger when they first started to feel they might not be straight. Only 7% were in their twenties, and 4% were 30 or older. Gay men are the least likely to report first having these feelings in their twenties or beyond: 3% say they were 20 or older, compared with 14% of lesbians and 15% of bisexuals.

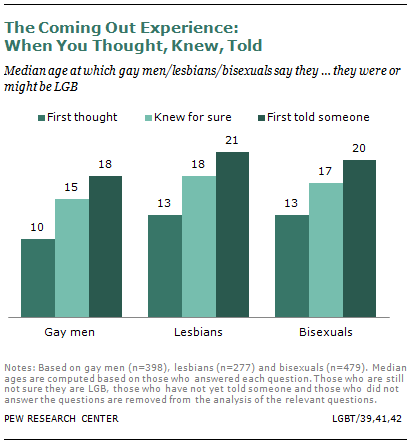

After these initial feelings, it took some time for most LGBT adults to be sure of their sexual orientation or gender identity. 15 Among LGBT adults who say they know for sure that they are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (92%), 17 is the median age at which they say they knew.

Relatively few LGBT adults (5%) say they were sure about their sexual orientation or gender identity before they were age 10. A majority (59%) say they knew between the ages of 10 and 19. One-in-five say they knew for sure they were lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender when they were in their twenties, and 8% say it wasn’t until they were 30 or older. Some 6% say they still aren’t entirely sure.

Again, gay men reached this milestone, on average, sooner than lesbians and bisexuals. The median age at which gay men say they were sure they were gay is 15. For lesbians, the median age when they were certain about their sexual orientation was 18, and for bisexuals it was 17.

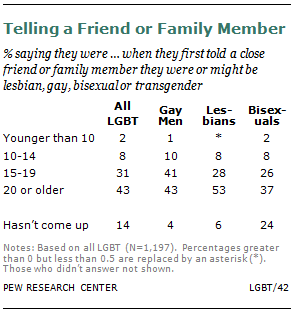

Telling Friends and Family

Among those who have told a friend or family member about their sexual orientation or gender identity, the median age at which they did this was 20. The median age is slightly lower for gay men (18) than lesbians (21) or bisexuals (20).

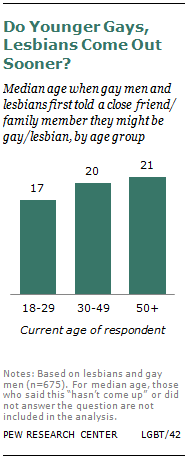

Among gay men and lesbians under age 30, 24% say they first told a friend or family member that they were gay or lesbian before the age of 15. This compares with 8% of gay men and lesbians between the ages of 30 to 49 and 3% of those ages 50 and older. Fully two-thirds of gay men and lesbians under age 30 say they shared their sexual orientation with a friend or family member before they were 20 years old. This compares with 47% of those ages 30 to 49 and 35% of those ages 50 and older.

It is important to note that many LGBT adults followed a different sequence in coming to realize their sexual orientation or gender identity and beginning to share it with others. Some individuals first felt they might be something other than straight, then told someone about it, but are still not entirely sure. Others may know for certain that they are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender but may have never shared this information with anyone.

Telling Mom and Dad

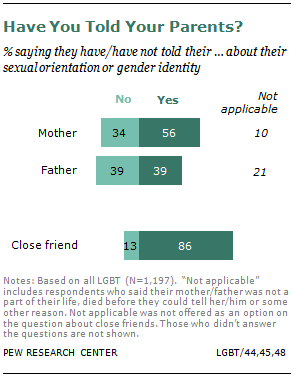

An important milestone for many lesbians, gay men, bisexuals and transgender people is telling their parents about their sexual orientation or gender identity. Overall, LGBT adults are more likely to have shared this information with their mothers than with their fathers. Most say telling their parents was difficult, but relatively few say it damaged their relationship.

Roughly four-in-ten LGBT adults (39%) say they have told their father about their sexual orientation or gender identity. The same share say they have not told their father. An additional 21% say that their father is deceased or that they have no relationship with him.

Overall, LGBT adults are much more likely to have told a close friend that they are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender than they are to have told one of their parents. Fully 86% say they have shared this information with a close friend.

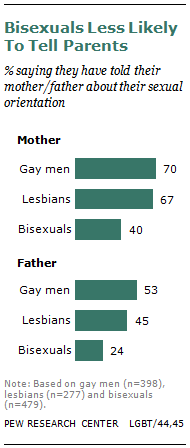

Across LGB groups, gay men and lesbians are much more likely than bisexuals to have told their parents about their sexual orientation. Fully 70% of gay men and 67% of lesbians have told their mother, compared with 40% of bisexuals. Similarly, 53% of gay men and 45% of lesbians have told their father, compared with only 24% of bisexuals.

LGBT respondents who said that they have not told their parents about their sexual orientation or gender identity were asked in an open-ended question why they had not shared this information. Two main reasons emerged. First, many respondents say it was not important to tell their parent or that the subject never came up. About one-in-four respondents (27%) who have not told their mother gave this as a reason, as did 21% who have not told their father.

Bisexuals are much more likely than gay men and lesbians to say their sexual orientation never came up with their parents or that raising the subject was not important to them. Among those who have not told their mothers, 34% of bisexuals and 16% of gay men and lesbians gave this type of explanation when asked why they hadn’t told her. 17 The pattern is similar among LGB adults who said they have not told their father about their sexual orientation.

The second-most common response given by LGBT adults in explaining why they did not tell their mother or father about their sexual orientation or gender identity was that they assumed their parent would not be accepting or understanding of this, or they worried about how it would affect their relationship with their parent. Among LGBT respondents who have not told their mother, 22% gave this type of explanation; 20% of those who haven’t told their father gave a similar reason. There are no significant differences here between gay men, lesbians and bisexuals.

One-in-five gay men and lesbians who have not told their mother about their sexual orientation say they never told her because she already knew or someone else told her. A much smaller share of bisexuals says this—only 7% say they didn’t tell their mother, but that she already knew. Among LGB adults who have not told their father about their sexual orientation, 13% of gay men say this is because he already knew, as well as 17% of lesbians and 5% of bisexuals.

For LGBT adults who have not told their father that they are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender, about one-in-ten (12%) say they didn’t tell him because they do not have a close relationship with him. This is less of a factor with mothers: Only 4% of LGBT respondents say they haven’t told their mother about their sexual orientation because their relationship is not close.

Voices: Why Didn’t You Tell Your Mother or Father?

“My mom strongly upholds all of the views of her church and one of those is being totally anti-gay. She is very conservative and not very accepting.” – Lesbian, age 65

“It was experimentation. I didn’t think it was any of her business, as it was none of her business how many men partners I had.” – Bisexual woman, age 61

“Don’t want to stress her out. Her oldest brother was casualty of the AIDS epidemic in the early 90s.” – Gay man, age 43

“I always felt she already knew. I always meant to have ‘the conversation’ but the time never seemed right.” – Gay man, age 57

“It’s just never come up. I rarely discuss details of my love life with anyone since I am a deeply private person. If I were to make a serious commitment to another woman, I would tell my mother about it” – Bisexual woman, age 39

“This is not a subject to discuss or tell anyone about, ever, except those with whom I may enjoy having sex with. It’s not my identity. It is an activity – like bowling, or gardening, or pick-up basketball games in the neighborhood, or joining the PTA – except that it’s more intimate & personal, as a matter of discretion and respect for proper behavior in polite society.” – Bisexual woman, age 54

“I doubt he would have any clue what I was talking about or why I was bringing it to him or what it meant.” – Transgender person, age 19

“He’s very religious and he observed my orientation before I outwardly expressed it. It was like a silent acknowledgement but not acceptance.” – Lesbian, age 58

“Unless I decide to be with a girl long term, there is no reason for him to know.” – Bisexual woman, age 25

“He was homophobic, plus we had a rocky relationship. I was very conflicted about him. I wanted his love.” – Gay man, age 86

“He’s not as open minded as my mother, so [I’m] waiting.” – Bisexual man, age 26

LGBT/44new,45new

It Was Hard, but It Was Worth It

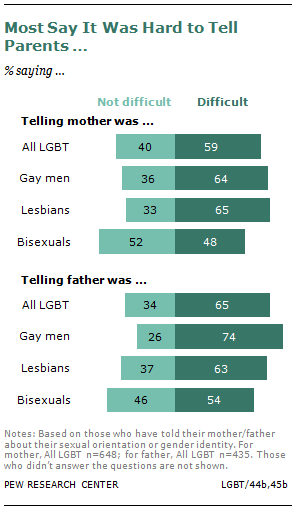

Among those respondents who say they have told their mother, 59% say it was difficult to tell her; 40% say it was not difficult. Gay men and lesbians are more likely than bisexuals to say telling their mother about their sexual orientation was a difficult thing (64% of gay men and 65% of lesbians say it was difficult, vs. 48% of bisexuals).

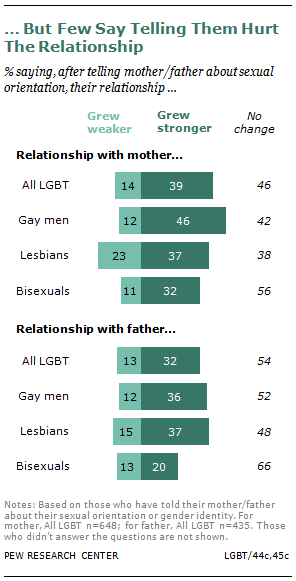

Four-in-ten LGBT adults (39%) who say they have told their mother about their sexual orientation say, since telling her, that their relationship has grown stronger. An additional 46% say their relationship with their mother has not changed, and 14% say their relationship has grown weaker. Lesbians are twice as likely as gay men to say telling their mother about their sexual orientation hurt their relationship (23% of lesbians say the relationship grew weaker, compared with 12% of gay men).

For those who have told their father that they are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender, the pattern is much the same. About two-thirds (65%) say it was difficult to tell their father about their sexual orientation or gender identity, while 34% say it was not difficult. Gay men are about as likely as lesbians to say it was hard to share this information with their father (74% of gay men vs. 63% of lesbians).

Brothers and Sisters

Among lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender adults who have a sibling, roughly six-in-ten say they have told their siblings about their sexual orientation or gender identity. Two-thirds (65%) have told a sister, and 59% have told a brother.

Gay men and lesbians are more likely than bisexuals to have shared this information with a sister or brother. Among gay men and lesbians who have at least one sister, large majorities say they have told a sister about their sexual orientation (75% of gay men and 80% of lesbians). By contrast, only 50% of bisexuals say they have told a sister that they are bisexual. Similarly, roughly three-quarters of gay men (74%) and lesbians (76%) with at least one brother say they have told a brother about their sexual orientation, compared with 42% of bisexuals.

Voices: Tell Us More About Your Coming Out Experience

“It is always nerve-wracking when I come out to someone, but I have had a positive reaction from everyone I have told, except for my dad. My mom and I were already very close, so it didn’t affect our relationship. Nearly everyone in my life knows, and if someone new comes into my life, I tell him or her. If this person cannot accept that I am gay, then he or she does not need to be a part of my life.” –Lesbian, age 25, first told someone at age 13

“There were two friends from my high school days who I lost after coming out to them. That was painful. They had always said they believed in everyone being their own person and living their own life, so this was a surprise when they trotted out the “see a shrink” line and wouldn’t talk to me anymore. Plus, we’d just been through the ’60s and the Summer of Love and all that – I expected more open minds. Everyone else has been great, and for 40+ years I have never hesitated about or regretted being out.” –Lesbian, age 58, first told someone at age 17

“Coming from a strong evangelical Christian upbringing, and still applying that to my life, it’s been difficult. A lot of people (some or most of my family included) don’t approve or want to have anything to do with it, and choose to ignore my partner.” –Lesbian, age 28, first told someone at age 16

“I wish I would have told people sooner. I came of age when AIDS first emerged and homophobia was acceptable. I wasted too many years being afraid of my sexuality and making choices that allowed me to hide in the background of life. I was sort of a professional wallflower.” –Gay man, age 43, first told someone at age 22

“The most difficult part was acknowledging this in myself. Telling my best friend wasn’t too hard. I was nervous, even though he told me afterwards that he had known for a while. None of my other friends or family members know and I don’t plan on telling them unless absolutely necessary. I’m comfortable with myself, but am afraid of the reactions that I will receive should I divulge this information to those with whom I am closest.” –Bisexual woman, age 20, first told someone at age 20

“In the beginning, it was difficult, but always ended up positive. Nowadays, there really is no decision. I simply have a sexual orientation the same as anyone else, and talk about my partner, etc., the same way anyone mentions their opposite-sex spouse, and there’s no “event” associated with it.” –Gay man, age 57, first told someone at age 21

“The hardest thing is just… there’s really no good way to bring it up. You almost hope people will ask, because it’s just sort of a burden, carrying around a secret. For my parents, I was mostly worried that they wouldn’t take it seriously and treat it as a phase. For my friends, I was scared they would think I was hitting on them. I come from a pretty Catholic, Midwestern town, so it was rough.” -Bisexual woman, age 20, first told someone at age 14

“It was extremely difficult to come out to my family. I didn’t do so until I was in my 30’s. Thankfully, my family said they loved me no matter what. Many of my friends weren’t as fortunate to have such a positive response. It’s still not something my family really discusses but I am happy that I was finally able to share my orientation with them.” -Bisexual woman, age 41, first told someone at age 17

“It’s always on a case by case basis. Those who love me and truly care for me have, of course, been the most understanding. My brother has actually taken the news the best; much better than I even expected. He’s met the current guy I’m dating and they hit it off well.” -Bisexual man, age 31, first told someone at age 18

“My first ‘coming out’ was in a Facebook post. My friends have been cool; they generally use the right pronouns once that was explained and they all call me my chosen name now which is just wonderful. Now on the internet and in association with peers and fan culture, I am out. The people I am not out to generally include adults, such as coworkers or friends parents, and my own family – I don’t feel that, as the average person (and not in a more accepting youthful age), they would really ‘believe’ in nonbinary genders or understand me saying that I am one.” –Transgender person, age 19

Cities, Towns, Neighborhoods

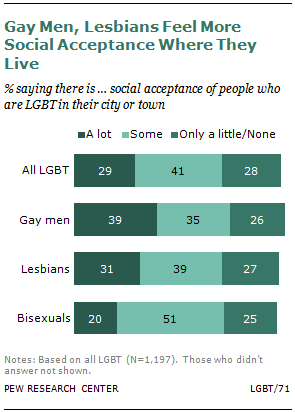

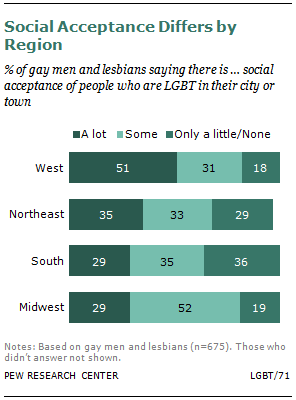

Gay men and lesbians are more likely than bisexuals to say there is a lot of social acceptance of the LGBT population in their city or town. Four-in-ten gay men (39%) and 31% of lesbians, compared with 20% of bisexuals, say there’s a lot of acceptance where they live.

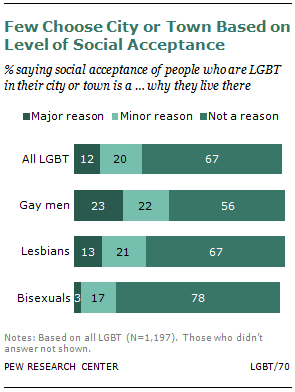

Regardless of how they feel about the level of social acceptance in their city or town, most LGBT adults say this is not a reason why they live in that particular place. Only 12% say the level of social acceptance in their city or town is a major reason for living there. One-in-five say this is a minor reason. Fully two-thirds (67%) say this is not a reason at all.

Overall, gay men and lesbians are more likely than bisexuals to say the level of social acceptance in the city or town where they live is an important reason why they live there. Some 23% of gay men say this is a major reason, and 13% of lesbians say the same. Only 3% of bisexuals say the level of social acceptance of LGBT adults is a major reason for living in their city or town.

Among gay men and lesbians, there is a significant age gap on this measure. Gay men and lesbians under age 45 are much more likely than those ages 45 and older to say the level of social acceptance in their city or town is a reason why they live there. Among those ages 18 to 44, about half (48%) say the level of social acceptance is at least a minor reason why they live in their city or town. This compares with only 33% of gay men and lesbians who are 45 and older. Among the older age group, 67% say this is not a reason why they live in their community.

Gay men and lesbians with a college degree are more likely than those who have not completed college to say the level of social acceptance in their city or town is one reason for living there (49% of college graduates say this is a major or minor reason, compared with 35% of non-college graduates).

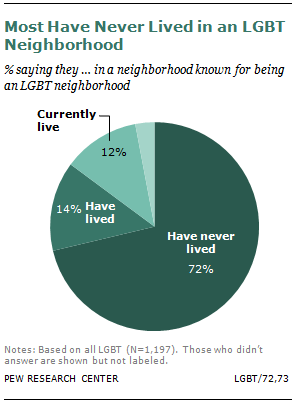

LGBT Neighborhoods

Gay men are more likely than lesbians to have lived in an LGBT neighborhood at some point in their life. Three-in-ten gay men (32%), compared with 18% of lesbians, either live in this type of neighborhood now or did in the past. Among bisexuals, 26% live or have lived in an LGBT neighborhood. Bisexual women (29%) are much more likely than bisexual men (17%) to have done this.

Among gay men and lesbians, the more important they say their sexual orientation is to their overall identity, the more likely they are to have lived in an LGBT neighborhood. Fully one-third (35%) of those who say being gay or lesbian is extremely or very important to their overall identity either live in an LGBT neighborhood now or have lived in one in the past. This compares with only 21% of those who say their sexual orientation is less important to their overall identity. Some 78% of this group have never lived in an LGBT neighborhood.

Among all LGBT adults, non-whites are more likely than whites to have lived in an LGBT neighborhood (31% of non-whites vs. vs. 23% of whites say they have ever lived in this type of neighborhood). There is no significant difference by age in the share of LGBT adults who either live in an LGBT neighborhood or have done so in the past, but LGBT adults ages 45 and older are more likely than younger LGBT adults to say they did this in the past, but are not currently living in this type of neighborhood. There are no differences by relationship status either. LGBT adults who are married or living with a partner are just as likely as those who are not in a relationship to say they have lived in an LGBT neighborhood.

Friends and Co-Workers

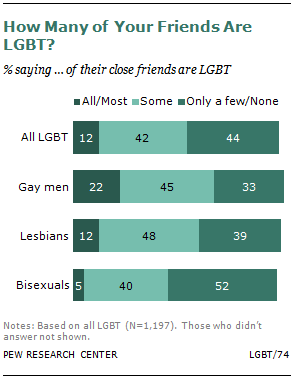

There are significant differences across LGB groups. Gay men are more likely than lesbians or bisexuals to have a lot of LGBT friends. Some 22% of gay men say all or most of their close friends are LGBT, compared with 12% of lesbians and 5% of bisexuals. Among bisexuals, fully half say only a few (41%) or none (12%) of their friends are LGBT. Bisexual men are much more likely than bisexual women (67% vs. 47%) to say only a few or none of their close friends are LGBT.

Not surprisingly, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender adults who have lived in an LGBT neighborhood are more likely than those who have not to have a lot of LGBT friends. Among those who live in an LGBT neighborhood now or have in the past, 21% say all or most of their friends are LGBT. Among those who haven’t lived in this type of neighborhood, only 10% say the same.

Finding Acceptance at Work

Gay men find their workplaces somewhat more accepting than do bisexuals. Among employed gay men, 60% say their workplace is very accepting of gay men. Half of working lesbians say that their workplace is very accepting of lesbian employees, and 44% of bisexuals say their workplace is very accepting of bisexual employees.

Although they seem to find at least some acceptance at work, only one-third of employed LGBT adults say all or most of the people they work closely with at their job are aware of their sexual orientation or gender identity. An additional 18% say some of the people they work closely with know they are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender. Some 22% say only a few of their co-workers know this, and 26% say no one at work knows.

There are big gaps here across LGB subgroups. About half of gay men (48%) and lesbians (50%) who work say all or most of the people they work with closely at their job know that they are gay or lesbian. Among bisexuals, only 11% say most of their closest co-workers know they are bisexual. Fully seven-in-ten bisexuals who work say only a few or none of the people they work closely with at their job know they are bisexual.

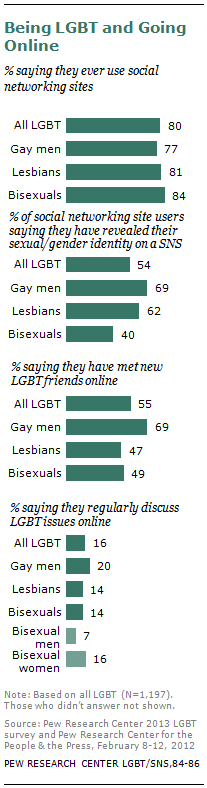

Going Online

Some 54% of LGBT social networking site users say they have referred to being LGBT or revealed their sexual orientation or gender identity on a social networking site. Gay men (69%) and lesbians (62%) are more likely to say they have done this than bisexuals (40%). Younger LGBT social networking site users are also more likely to be open about their sexual or gender identities online than older users. Some 58% of those ages 18 to 44 say they have revealed their identity on a social networking site compared with 46% of those ages 45 and older.

Overall, about half (55%) of LGBT adults say they have made new LGBT friends online or through a social networking site. Gay men are more likely to say they have met new LGBT friends online (69%) than either lesbians (47%) or bisexuals (49%).

Though social networking sites are popular among LGBT internet users and many have made LGBT friends online, using the internet to discuss LGBT issues is less common. According to the Pew Research survey, only 16% of LGBT adults say they regularly discuss LGBT issues online or on a social networking site. Gay men (20%) are more likely to do this compared with bisexual men (7%). Some 16% of bisexual women and 14% of lesbians also say they regularly discuss LGBT issues online.

There is no significant difference across LGBT groups in the share saying they are very happy. Roughly one-in-five gay men (18%), lesbians (20%) and bisexuals (16%) are very happy.

Among all LGBT adults, there is some variation in happiness across age groups. Nearly equal shares of young, middle-aged and older LGBT adults say they are very happy. However, those under age 50 are much more likely than those ages 65 and older to say they are not too happy (19% vs. 6%).

There are bigger gaps by income. LGBT adults with annual family incomes of $75,000 or higher are about twice as likely as those with lower incomes to say they are very happy (32% vs. 15%). LGBT adults at the lowest end of the income scale (with annual incomes of less than $30,000) are about twice as likely as those in the middle- and highest-income brackets to say they are not too happy (23% vs. 12% for middle and high-income LGBT adults).

There is a similar income gap in happiness among the general public. Among all adults, about one-in-four (25%) of those with annual household incomes of less than $30,000 say they are not too happy with their lives overall. This compares with 13% of those making between $30,000 and $74,999 and only 6% of those making $75,000 or more. LGBT adults are more likely than all adults to fall into the lowest income category (with annual family incomes of less than $30,000). This is due in part to the fact that fewer of them are married and living in dual income households (see Chapter 1 for more details).

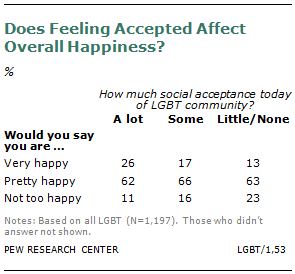

Perceptions of how much social acceptance there is of gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people these days is also related to personal happiness. A large majority of LGBT adults (77%) say that there is at least some social acceptance of the LGBT population today. Those who say there is a lot of acceptance are happier than those who say there is little or no acceptance. Among those who see a lot of social acceptance, 26% are very happy. This compares with 13% of those who see little or no acceptance. Among those who say there is some acceptance, 17% are very happy.

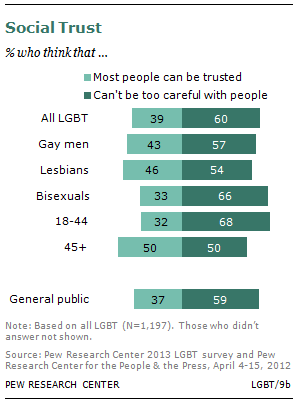

Trust in Others

Bisexuals are somewhat less likely than lesbians and gay men to say that most people can be trusted. There are big differences in trust between bisexual men (45% say most people can be trusted) and women (29%).

Both in the general public and among LGBT adults, younger people are less likely than others to say that most people can be trusted.

- Transgender respondents were asked, “How old were you when you first felt your gender was different from your birth sex?” The sample size, however, is too small to report this separately. ↩

- All LGBT adults were asked, “How old were you when you first knew for sure that you were (L/G/B/T), or are you still not sure?” As a result, transgender respondents are included in the LGBT total, but still cannot be shown separately. ↩

- This analysis is limited to gay men and lesbians, because of the high share of bisexual respondents who have not told a close friend or family member about their sexual orientation. ↩

- Gay men and lesbians are combined here because of the small number of lesbian respondents who said they have not told their mother about their sexual orientation (n=64). ↩

- Respondents were asked specifically about their own sexual orientation or gender identity. i.e., gay men were asked how accepting their workplace is of gay employees. ↩

- General public results are from a national survey of 1,081 adults conducted May 10-13, 2013. Interviews were conducted online through the random sample panel of households maintained by GfK Knowledge Networks. ↩

- This includes those who are in a civil union. ↩

Social Trends Monthly Newsletter

Sign up to to receive a monthly digest of the Center's latest research on the attitudes and behaviors of Americans in key realms of daily life

Report Materials

Table of Contents

Striking findings from 2021, public sees black people, women, gays and lesbians gaining influence in biden era, economy and covid-19 top the public’s policy agenda for 2021, 20 striking findings from 2020, our favorite pew research center data visualizations of 2019, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Growing Up With Gay Parents

Guests: Abigail Garner * Wrote, MyTurn column in Newsweek about growing up with Gay parents * Founder, familieslikemine.com Jesse Gilbert * Raised by two mothers and several other women in an urban compound Charlotte Patterson * Professor of Psychology, University of Virginia Jakii Edwards * Author, Like Mother, Like Daughter?: The Effects of Growing Up in a Homosexual Home (Unknown, 2001) Noelle Howey * Editor Out of The Ordinary: Essays on Growing Up With Gay, Lesbian and Transgender Parent (St. Martin's Press, 2000) * Author of the forthcoming book Dress Codes: Of Three Girlhoods, My Mother's, My Father's and Mine (Picador USA, May 2002) Kids of all ages and backgrounds would probably agree that simply having parents is enough to fuel teenage angst. So, what if one or both of your parents is openly gay? Does this make growing up even more difficult? On the next Talk of the Nation , Neal Conan talks with young adults who were raised by openly gay parents.

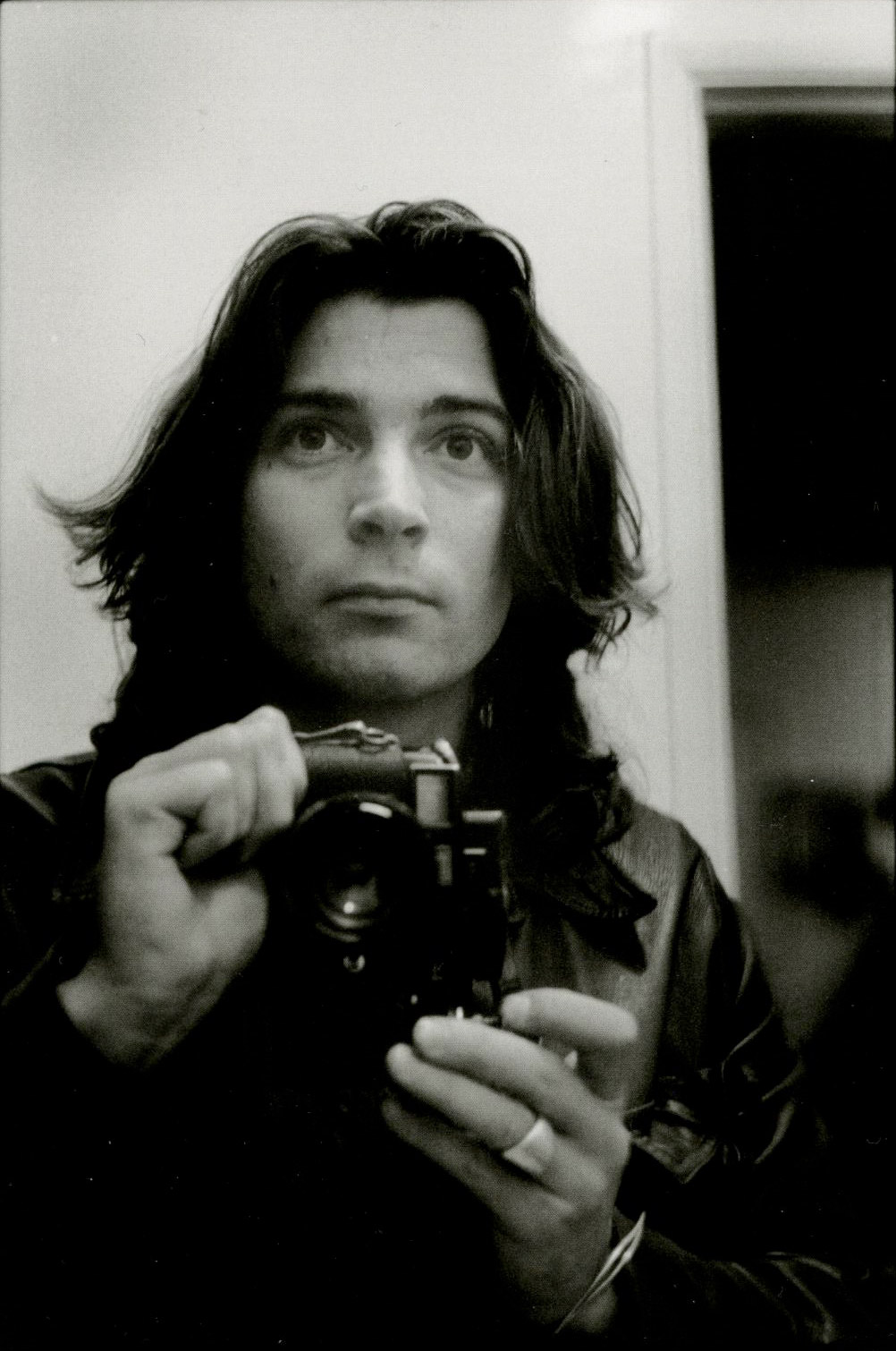

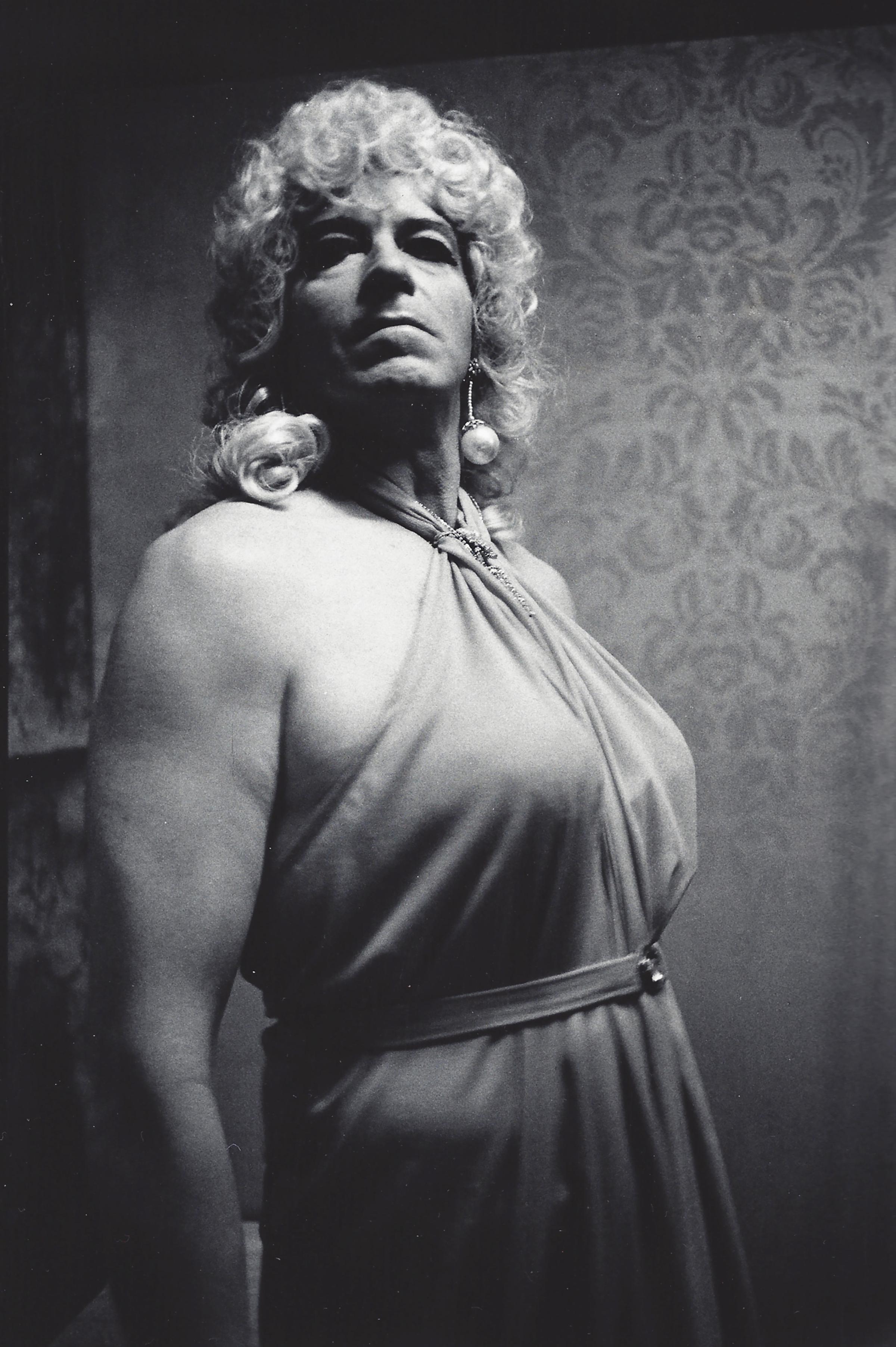

Pioneering Photographs of Gay Life in the 1960s

“I was 19, vulnerable, young and putting my own identity together,” says photographer Anthony Friedkin when reflecting on his first project, The Gay Essay , which documents gay culture in Los Angeles and San Francisco between 1969-1972. What started, as a self-assigned project for a young photographer growing up in Hollywood has now become one of the most authentic portraits of gay life in America from this period.

In 1969, the same year as the Stonewall riots in New York City, a gay cultural revolution was growing in America. At the time, most depictions of gay men and women in mainstream media were found in salacious newspaper and tabloid articles, all of them reported from a murky distance. LIFE’s two-part series Homosexuality in America from 1964, featured dark and shadowy photographs by Bill Eppridge. They capture a dark tension and fear that Friedkin’s work moves past with a tender intimacy.

While growing up in Hollywood, Freidkin’s parents worked in the film industry and had close friends that led full openly gay lives. He saw that world as a “refuge” and a place where gays were “allowed to be themselves” more than in any other place.

But The Gay Essay really began while he explored the Los Angeles Gay Community Services Center where he met Morris Kight and Don Kilhefner, two men who ran the programs there and founded the Gay Liberation Front in Los Angeles in 1969 where they mobilized the community against the LAPD’s harassment of homosexuals. They acted as Freidkin’s guides. “They just helped me all around,” he recalls. “They especially helped me in learning how to listen, and really allowing people’s energy to come to me and through the lens of my camera.”

For Friedkin, the goal was to move past many stereotypes and deepen the representation of gay individuals of all types. “It was more about my desire to create a great set of pictures with a heartfelt determination to honor gay people, respect them and their freedom,” he says. “In The Gay Essay I wanted to celebrate the gays that were living openly,” especially at a time, in the early days of the gay movement, following the Stonewall riots. “It upset me tremendously to see the ways gays were being treated,” he adds. “I had friends that got beat up in bars. I was furious about it. Even now, when I look through the book, it gets very emotional for me.”

All along, Friedkin worked slowly, closely documenting hustlers, teens at Trouper’s Hall, drag performers and the first parades in West Hollywood. He also recorded the violence of vice cops at the time. “I was kind of like a racehorse with blinders on and a Leica around my neck,” he says. “I was just going to do this for me as the way I wanted to do it. In a way I think it was probably good that I had a certain innocence in that way that I didn’t overly academically try to predetermine what it was I might do, or why I should do it. I just wanted to go out and become part of it, and be it. I really, really wanted to come out on the other side of this with a very admirable, important set of photographs.”

As a photographer making work since the age of eight, he admired Henri Cartier-Bresson and developed exercises to try and capture what Cartier-Bresson termed as the “decisive moment”. “I used to pack my ears with wax and cotton and all kinds of stuff so I would go deaf. I would do that so I could just look at the world that was changing and moving around me in the sense of the ‘decisive moment’ and just look for moments amongst people, places, things, light that would strike me strong enough to want to make a photograph of it.” He was drawn to the work of many photographers documenting the social landscape of the 1960s with humanistic intent for change. “I was educated to the worlds of W. Eugene Smith, Robert Frank, Bruce Davidson and Danny Lyon,” he says. “I think by really committing yourself to something and really trying to understand it deeply, than the photographs themselves become more intimate and have more depth to them.”

It took many years for his photographs to be seen. “When I first did this, a lot of the American publications wouldn’t go near it,” he says. “They were afraid they’d lose their advertisers, because of the idea of showing two men kissing each other and showing intimacy toward each other. It was just mind-blowing to them. They were so afraid.”

In 2014, The Gay Essay was first shown in its entirety at the De Young Museum in San Francisco and was published as a book by the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco and Yale University Press.

At a time of when photography’s ability to affect social change is in question, Friedkin’s work shows that taking the slow route and connecting with subjects will usually make the most lasting impression, even 40 years later. Today, as he looks back on his life’s work, Freidkin feels proud. “Everything I love about photography is in the gay essay: the sense of the event, capturing the soul of the people, the journey, the process, the unknowns,” he says. “And then really making sense out of it and putting it together, it gives me great strength actually.”

Anthony Friedkin ‘s The Gay Essay is on view at Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York City until March 4.

Paul Moakley is the Deputy Director of Photography and Visual Enterprise at TIME. Follow him on Twitter .

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Why We're Spending So Much Money Now

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- Breaker Sunny Choi Is Heading to Paris

- Why TV Can’t Stop Making Silly Shows About Lady Journalists

- The Case for Wearing Shoes in the House

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

You May Also Like

We use cookies to help better serve your experience. Accept Cookies

- Receive Emails

I Wanted to Like that NYT Photo Essay About Growing up with Gay Parents

I wanted to like the photo essay “What Could Gay Marriage Mean for the Kids?” in the recent New York Times Sunday Review. I really did. For one thing, I have a personal investment in the question: my partner and I—gay married until the Supreme Court says otherwise—are raising a toddler, and I’d like to believe she’s going to be okay. On the whole , the studies I’ve seen suggest that she will be. And, visually, maybe I’ve gotten a little too used to the sappy-sweet celebrations of gay family life that have become standard fodder on liberal social media feeds.

So, I wasn’t prepared for the gut punch that came along with Gabriela Herman’s fourteen portraits featuring adult children of gay parents. Taken one-by-one, the photographs capture strong, thoughtful young adults in moments of solitude. Cumulatively, though, the series takes on an inescapable sense of sorrow and isolation, and not just because of captions that frequently emphasize the subjects’ struggles with their parents’ identities. As a [gay] parent viewing the photo essay, I felt a rush of defensiveness and worry. As a scholar of visual rhetoric, I wanted to understand why. What was it about these photographs that so set me on edge?

After a hard look, it finally came clear to me: This photo essay explores the difficulty of having a gay parent in the 80s, 90s, and early 00s. As a reflection on what gay marriage means for today’s generation of kids, though, it is (I hope) rather out of date.

Herman’s photo essay combines therapeutic personal narrative, incipient activism, and social analysis. Of the three, the theme of therapy is the strongest. More often than not, the portraits frame their adult subjects as in recovery, using all the conventions of post-trauma photography: solitary figures, haunted gazes, romantic lighting, sparse domestic spaces. As a viewer, I ache for these adults and for the children they once were. Ache, however, is not the feeling I want to have in response to the title’s loaded question about the future, “What could gay marriage mean for the kids?”

The disjunction between the title’s forward-looking question and the trope of past trauma is perhaps most palpable in the first portrait after the essay’s opening text. In it, Zach Wahls—the young man whose impassioned speech in defense of his family went viral in 2011—lies on a blue couch, his head propped on a rust-colored pillow. Wahls gazes mournfully at the camera, his hands clasped on his stomach, his scant beard elegantly untrimmed. The room behind him is dark, and a warm light falls on the couch and across his body. So much about the photograph evokes a psychoanalytic encounter, and it sets the tone for the essay’s larger visual therapy session.

The melancholy of Wahls’ portrait is only enhanced by its contrast with the other public picture we have of him: that of a clean-shaven college student in an almost-tailored suit, speaking confidently before the Iowa House of Representatives. For all their strength and dignity, there’s little doubt that Wahls and the other men and women in the NY Times Magazine essay have painful stories that have shaped their past and their present. Still, that earlier media image had Wahls closing his speech with the words:

“The sexual orientation of my parents has had zero effect on the content of my character.”

If character and mental health are not perfectly correlated, it’s still not a statement that lends one to visualize a treatment situation.

Taken as a whole, the portraits show isolated adults in empty rooms, abandoned playgrounds, and vacant streets, sometimes half-hidden by curtains or shadows. Some stare resolutely at the camera as if to demand recognition and redress, like the photo leading this post.

Others look into the distance, starkly alone with their memories. Soft light highlights faces and hands—these are gentle people who have emerged whole from challenging childhoods. They clearly have the photographer’s sympathy, and gain the viewer’s as well.

While sympathy is a powerful emotion, however, it sits awkwardly with the task this photo essay sets for itself with its provocative title and subtitle:

“What could Gay Marriage Mean for the Kids?: When courts consider same-sex unions, they often ask about what life is like for children with gay parents. Here are some answers.”

These photographs are answers, but not to the title as written. Instead, they answer the question, “what was it like to be the child of a gay parent at the end of the twentieth century, well before gay marriage was a viable possibility in the United States?” The photographs give a clear and sad answer to that question. They emphasize the trauma of social isolation and discrimination; they highlight the challenge of growing up different from your peers.

Ultimately, then, the photo essay shares the experiences of a generation of kids born after LGBT people started coming out en masse but well before the recent wave of public acceptance (for lesbians and gay men who don’t rock the societal boat too much). These aren’t pictures of the children of gay marriage; they’re pictures of people who grey up in a world hostile to gay people and their families. That hostility isn’t entirely gone, and marriage rights won’t make it magically disappear. Still, these photographs are reminders of how important it is to work toward a better future, not predictions of gay marriage’s future.

So now I understand the gut-punch a bit better: In these photographs, we see strong, self-possessed adults who are also deeply haunted by their experiences as part of gay families. If that is what gay marriage could mean for kids today, that gives Justice Scalia rounds of ammunition that I’d prefer he not have.

— Christa Olson

( photos : Gabriela Herman for the New York Times Sunday Review)

Christa Olson See other posts by Christa here.

Follow us on Instagram ( @readingthepictures ) and Twitter ( @readingthepix ), and subscribe to our newsletter.

A curated collection of pieces related to our most-popular subject matter.

- Christa Olson

- Culture Focus

- Photography/Photojournalism

Comments Powered by Disqus

Orion Magazine

America's Finest Environmental Magazine

Six Questions for Taylor Brorby, author of ‘Boys and Oil’

S et against the prairies and coalfields of North Dakota , Taylor Brorby’s Boys and Oil: Growing Up Gay in a Fractured Land is a lyrical coming-of-age memoir about the loneliness of a gay childhood in the rural West, the legacy of extractive industries, and the making of an environmental activist.

Kathleen Yale: While researching, you found incredibly few gay narratives in the pantheon of literature of the American West, Annie Proulx’s short story Brokeback Mountain (and the lauded Hollywood film of the same name) being the only one most people can name. Can you speak a little about any feelings of obligation, and perhaps resulting pressure, to be a pioneer of sorts in this genre?