History Cooperative

Who Invented Paper? The History of Paper and Paper Making

The invention of paper is attributed to ancient China. Papermaking is traditionally believed to have been invented by Cai Lun, a Chinese eunuch and official during the Eastern Han Dynasty, around 105 CE. Cai Lun’s contribution to papermaking involved the refinement of the process, making it more consistent and practical for widespread use.

This invention had a profound impact on the world as it made written information more accessible, leading to advancements in education, communication, and the preservation of knowledge. Papermaking technology eventually spread to other parts of the world and played a pivotal role in the dissemination of information and culture.

Table of Contents

Who Invented Paper?

Cai Lun, a Chinese eunuch and government official during the Eastern Han Dynasty (around 105 CE), is often credited with inventing a more standardized form of paper. He is known for refining the papermaking process by using a mixture of mulberry tree bark, old fishing nets, and other materials to create a pulp that could be formed into sheets.

READ MORE: A Full Timeline of Chinese Dynasties in Order

Cai Lun’s innovations marked a crucial step in the evolution of paper as a writing and printing medium. However, it’s important to note that papermaking was a gradual process that evolved over time , and Cai Lun’s work represents a significant milestone rather than the sole invention of paper. Different forms of early paper and writing materials were used in various parts of the world before the widespread adoption of paper as we know it today.

Earlier Forms and Uses of Paper-Like Substances

Before the craft heralded by Cai Lun, ancient civilizations had embarked on their quests to document the intangible, inscribing their stories upon a myriad of surfaces, from the rigid constraints of clay tablets to the perishable papyrus of the Egyptians. The predecessor of paper, papyrus, was a medium primarily reserved for the elite and the sacred, given its labor-intensive process and the scarcity of materials. This thirst for a more versatile and accessible medium was, to a remarkable extent, quenched by the advent of paper, transcending boundaries in how knowledge was created, preserved, and shared.

READ MORE: Ancient Egypt Timeline: Predynastic Period Until the Persian Conquest

Recognition and Adaptation of Paper Invention Across the World

Paper, with its boundless potential, did not remain an exclusive secret of the Chinese empire for long. Through the Silk Road, explorations, and conquests, the knowledge of papermaking began to seep into the expansive terrains of the world beyond. The gradual percolation of this technology into the Middle East, and subsequently into the heart of Europe, symbolizes not merely the migration of an invention, but the ushering in of an epoch where ideas could be immortalized and disseminated with hitherto unimagined ease and efficacy.

When Was Paper Invented?

Paper was invented around 105 AD, under the auspices of the Han Dynasty, when Cai Lun unveiled his refined method of papermaking. Although ostensibly novel, Cai Lun’s method was an enhancement of existing knowledge, coalescing diverse practices into a unified, scalable methodology that metamorphosed isolated practices into a wide-reaching industry.

READ MORE: Ancient Chinese Inventions

Spread and Adaptation of Papermaking Technique Through the Centuries

As centuries unfurled, so did the craft of papermaking, intricately intertwining with the fates of empires and the aspirations of scholars, merchants, and artisans. By the 8th century, the technique infiltrated the sophisticated realms of the Islamic world, particularly in places like Samarkand and Baghdad, becoming synonymous with the illustrious academic and artistic achievements of the epoch. This subtle convergence of craft and intellect propelled the methodology westward, where it would eventually anchor in the scientific and cultural environments of Europe.

Notable Milestones in Early Paper Production

The introduction of water-powered paper mills in Spain during the 12th century signified a tangible departure from manual labor, unleashing a cascade of possibilities for mass production and broader accessibility. Likewise, the advent of the printing press in the 15th century intertwined with the availability of paper, propelling an unprecedented proliferation of knowledge, and scribing indelible marks upon the unfolding narrative of humanity.

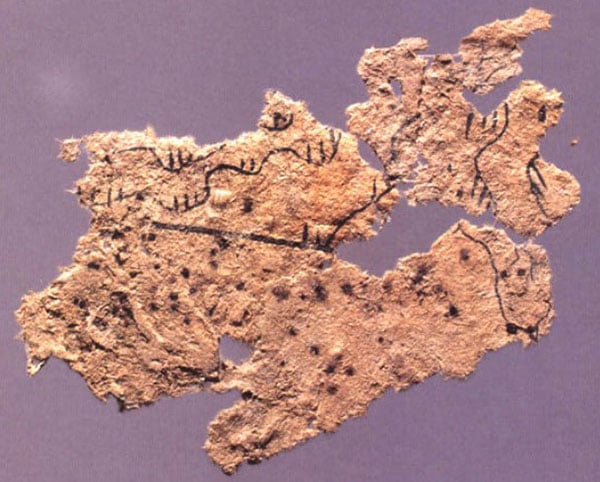

Historical Documentation and Evidence

Submerging into the reservoirs of historical documents, tangible artifacts narrate the intricate journey of paper through time and space. From the delicately inscribed scrolls safeguarded within the cavernous folds of ancient libraries to the meticulous records of merchants traversing the serpentine trails of the Silk Road, historical documentation enshrines the migration and adaptation of papermaking. Diverse evidence, such as the resilient manuscripts of the Islamic Golden Age and the voluminous tomes of European scholars, not only validate the chronology of the paper’s journey but also offer glimpses into the transformative influence it wielded across varied domains of human endeavor.

The Process of Ancient Papermaking

Early paper creation involved using various organic and natural materials. Unlike the sturdy yet pliable papyrus plant, early Chinese paper incorporated raw materials and resources such as mulberry bark, hemp fibers, worn fishing nets, and old rags. This amalgamation of materials was macerated into a pulp, setting the stage for a process that delicately balanced artistry and practicality, leading to a material that was at once durable, malleable, and elegantly fine.

Techniques and Steps in the Original Paper Production

Initially, the collected materials, enriched by their varied origins, were submerged in water, transforming into a homogenized pulp through a meticulous process of fermentation and maceration. This pulp was then suspended in water and carefully ladled onto a flat, woven surface to form a thin layer. Nature’s own elements, air, and sunlight, caressed this fragile layer, coaxing it gently into a form that was robust yet whisper-thin, ready to cradle the ink and embody the thoughts of countless generations.

READ MORE: Who Invented Water? History of the Water Molecule

Innovations and Variations in Different Regions

There were various adaptations of this creation and each region had its own version. In the Islamic world, for example, craftsmen embraced the abundant flax and linen, diverging from the traditional Chinese materials, yet paralleling the essential techniques. Whereas, in medieval Europe, the introduction of mechanized mills and the adoption of various locally available materials, such as cotton and linen rags, reshaped the craft, tailoring it to their own technological abilities and needs.

READ MORE: Who Invented the Cotton Gin? Eli Whitney and Cotton Gin Impact on America

The Transition to Modern Papermaking

With the European introduction of the paper mill, driven by the inexorable currents of flowing water, the craft began to intertwine with industrialization. As centuries cascaded forward, further innovations, such as the invention of the papermaking machine and the adaptation of wood pulp in the 19th century, symbolized a stark divergence from the manual, artisanal practices of the past, melding the craft into the ever-accelerating pulse of the industrial age.

The Global Spread and Evolution of Papermaking

The knowledge about the techniques of papermaking found their way into civilizations far removed from the rich landscapes of China and Chinese papermakers. The agents of this dissemination were myriad: traders, explorers, and conquerors traversing the sinuous paths of the Silk Road.

Adaptation and Enhancements in the Middle East

When the gentle echo of papermaking reached the vibrant, intellectual arenas of the Middle East, it was embraced, nurtured, and included in their academic and artistic pursuits. The Islamic world, with its inherent reverence for knowledge and script, nurtured and enhanced the craft, introducing new materials and refining techniques to produce finer, more exquisite paper that became a coveted medium for the prolific scholarly and creative outputs of the time.

Introduction and Development in Europe

Europe welcomed paper as a harbinger of connectivity and knowledge dissemination. Paper mills, exploiting the energetic torrents of European rivers, breathed life into an industrial approach to papermaking. As time meandered through the Renaissance and into the Enlightenment, the proliferation of paper became synonymous with the dispersion of knowledge, creativity, and the inexorable forward march of innovation and discovery.

The Role of Paper in the Proliferation of Knowledge and Communication

With making paper, knowledge was no longer a fleeting whisper, tethered to the ephemeral. It could now traverse time and space, leaping from the vibrant minds of scholars, artists, and thinkers into the collective consciousness of entire civilizations. From the meticulous scrolls of medieval scribes to the mass-produced pages of enlightenment literature, and further into the hearty newspapers of the modern era, paper became an unassuming yet powerful catalyst, propelling societies into new realms of collective knowledge, awareness, and cultural evolution.

Impact of Paper on Society and Culture

Paper, in its humble existence, fortified the preservation and dissemination of knowledge, allowing the intellectual pursuits of one epoch to whisper wisdom into the ears of subsequent generations, and enabling the perennial flow of understanding that shaped the contours of society and thought through time.

Artistic Expression Through Paper

Beyond mere communication, paper tenderly cradled the artistic soul of humanity, offering a canvas where imaginations danced free and emotions found form. Calligraphy, painting, and origami, these delicate articulations of human creativity, found a welcoming space upon the accommodating expanse of paper.

The Economic Implications of Paper Production

The emergence of paper subtly yet irrevocably altered the economic landscapes of societies. Its pivotal role in facilitating complex bureaucracies, enabling expansive trade networks, and propelling the proliferation of printed material, erected an unseen yet foundational pillar upon which the economic dynamics of civilizations found stability and mobility. Further, the interplay between paper money and economic stratification surfaced, allowing for a nuanced and multifaceted medium of exchange, altering the economic interactions and hierarchies within society.

The Role of Paper in Education and Government

Paper was an unassuming accomplice in the evolution of educational and governmental structures. The educational realm, now enriched with textbooks, research papers, and written examinations, blossomed into a more accessible and structured entity, democratizing knowledge across various strata of society. Meanwhile, governmental machinations, facilitated by the written record, policy documentation, and bureaucratic correspondence, became more intricate and accountable.

The invention of paper is traditionally attributed to ancient China, with Cai Lun often recognized for his significant contributions to the development of papermaking around 105 CE during the Eastern Han Dynasty.

While paper as we know it has evolved and improved over time, Cai Lun’s innovations marked an important milestone in the history of papermaking. However, it’s essential to recognize that papermaking was a gradual process that involved the refinement of techniques and materials over centuries, and various forms of writing materials were used in different parts of the world before paper became the dominant medium for writing and printing.

How to Cite this Article

There are three different ways you can cite this article.

1. To cite this article in an academic-style article or paper , use:

<a href=" https://historycooperative.org/who-invented-paper/ ">Who Invented Paper? The History of Paper and Paper Making</a>

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

The History of Paper

The fascinating history of paper, from its ancient origins to the modern-day process.

Before paper as we know it existed, people communicated through pictures and symbols carved into tree bark, painted on cave walls, and marked on papyrus or clay tablets.

About 2,000 years ago, inventors in China took communication to the next level, crafting cloth sheets to record their drawings and writings. And paper, as we know it today, was born!

Paper was first made in Lei-Yang, China by Ts'ai Lun , a Chinese court official. In all likelihood, Ts'ai mixed mulberry bark, hemp and rags with water, mashed it into pulp, pressed out the liquid and hung the thin mat to dry in the sun.

During the 8th century , about 300 years after Ts’ai’s discovery, the secret traveled to the region that is now the Middle East. Yet, it took another 500 years for papermaking to enter Europe . One of the first paper mills was built in Spain , and soon, paper was being made at mills all across Europe.

Then, with paper easier to make, paper was used for printing important books, bibles, and legal documents.

England began making large supplies of paper in the late 15th century and supplied the colonies with paper for many years.

Finally, in 1690, the first U.S. paper mill was built in Pennsylvania .

At first American paper mills used the Chinese method of shredding old rags and clothes into individual fibers to make paper.

But, as the demand for paper grew, the mills changed to using fiber from trees because wood was less expensive and more abundant than cloth.

Talking Sustainability With Young Innovators

Explore forest product industry innovations and research from the 2022-2023 U.S Blue Sky Young Researchers Innovation Award winners.

The Paper Industry Today

Today, paper is made from trees grown in sustainably managed forests and from recycled paper.

Recycling has always been a part of papermaking.

When you recycle your used paper, paper mills will use it to make new notebook paper, paper grocery bags, cardboard boxes, envelopes, magazines, cartons, newspapers and other paper products.

Everything You Need to Know About Paper Recycling

Paper is one of the most widely recycled materials in the U.S. Nearly 50 million tons of paper was recovered for recycling in 2022. That amount could fill rail cars stretching from New York to Los Angeles nearly 3 times!

And, the paper recycling rate has met or exceeded 63% every year since 2009!

The paper industry uses recycled paper the make the essential products millions of people rely on every day. In fact, about 80% of U.S. paper mills use some recycled paper to make new and innovative products.

Dive deeper into how the paper industry is improving paper recycling.

Dive Into Recycling Innovations

Learn more about AF&PA member projects aimed at improving recycling technology and using more recycled fiber.

Paper Recycling Facts

Learn more about the paper and cardboard recycling rates, where recycled paper goes and more resources.

Learn How to Recycle Paper

Want to know how to recycle address window envelopes or paper-padded mailers? We've got you covered.

Get to Know the People Behind Our Industry

The forest products industry is a major national employer. While employing about 925,000 in the industry, more than 2 million indirect jobs are supported.

Hear more from the people driving innovation and helping shape future generations of industry leaders.

Hong Wilcoxon

Dive into what Wilcoxon does as a quality manager at Domtar's Engineered Absorbent Materials facility in Jesup, Georgia.

Lisa Berghaus

Explore the paper-based packaging design process with Lisa Berghaus of Monadnock Paper Mills.

Learn how Jenny Tang of Essity uses her STEM background to advance the industry.

Learn why Tony Diaz of Graphic Packaging International thinks sustainable forestry takes constant vigilance from everyone involved.

Tony Murphy

Find out what gets Tony Murphy of International Paper excited about the industry's future.

Rafael Garcia

Explore why Rafael Garcia of Georgia-Pacific believes environmental stewardship requires creating more value while using fewer resources.

History of Paper

Paper is a thin material produced from natural (or very rarely artificial) fibers, pressed together into solid structure after they were loosened in a hot water. This recipe was established more than 2000 years ago in Ancient China, and from that time it changed very little, only being enhanced by occasional advances of chemistry which caused creation of countless variations of paper types. Today, we are using paper all around us, and not only to write or paint on it, but also as a widely versatile material that can be used almost anywhere. Asian cultures use it as food ingredient, we interact with it any time when we buy something in stores, building materials for houses and various installations, cleaning products and much more.

Paper History

We could not imagine world today without paper, but if we look only few centuries to the past, its presence was significantly less noticeable. Here you can read more about origins of paper and its journey through history.

Paper Invention

Paper was invented in ancient china some 2200 years ago, but was popularized by one inventor – Cai Lun. Here you can learn much more about his life, work, and his legacy that is still impacting our daily lives.

Paper Facts

Paper is an extremely versatile material that has managed to infiltrate all facets of our modern culture – from being a writing surface to industrial construction material. Read more about interesting paper facts.

Making Paper

If you have ever wondered how paper is made today, here is the perfect place to get all the information about papermaking production process, raw materials and chemicals that are used by the paper industry.

Brief History

Being used in Ancient China since 2nd century BC, paper made a little impact until inventor Cai Lin managed to refine its production process, enabling the beginning of the true revolution of paper products all across the china. His technique could be used to reliable and quickly create small sheets of paper from heated wood chips, rags, cotton and fishnets (all natural materials rich in fibers), but they prevented creation of large paper sheets. The largest possible paper sizes were created rarely, and were used as writing or painting scrolls for Chinese royalty and nobility, and later on Japanese nobility where paper was truly accepted in every facet of their culture (most famously, as a building material of their houses that had parts of walls made from strong paper).

By 8th century, recipe of paper production arrived into the hands of Arabs, who quickly created their networks of paper mills all across their territories – from western border of China to the Northwestern Africa. During the time when Europeans did not have contact with the Arab paper (8th – 11th century), Islamic inventors, artists and book artisans managed to create widely accepted fashion culture around paper, making this still very expensive product used only in exclusive objects, such as paintings, extravagant decorations and off course books that were rarely made because of complexity of art and man-hours that had to be invested to create them. However, by early 11th century Crusades disrupted main centers of paper production in the Holy Land, shifting that production to other areas and pushing it closer toward Europe.

Spain and Sicily were the first countries that started using paper produced by Muslim paper mills in 11th century, and slowly as decades went paper mills started springing up all across Europe. First they appeared in France and Italy, moved northern to Germany, Holland and England, and after that they could be found everywhere. However, this did not mean that paper was suddenly cheaper and more available to everyone. On the contrary, paper was then still expensive, and less durable than parchment – paper-like structure created form the skin of animals. Even when Gutenberg created his moveable type machine for printing books, he continued using parchment because he and his compatriots feared that paper is will not be able to withstand the effects of long term exposure to air and moisture (they knew for certain that parchment and vellum papers could be stored for thousand years in right conditions).

Paper become widely available only after Fourdrinier paper machine became widespread across Europe and North America during 19th century. Ability to create continuous roll of paper powered by the steam machinery revolutionized paper industry completely, enabling it to become integral part of our modern history.

Today, United States and China produce the majority of paper used today, and many governments try desperately to regulate its production, recycling, reduce effects of pollution, deforestation and other environmental hazards that accompany industrial paper production.

The history of paper: from its origins to the present day

- Get inspired

Sarah Cantavalle Published on 4/5/2019

The history of paper is inextricably linked with that of culture and science .

The spark that set off the invention of paper was simple but extremely significant.

Humans had an urgent need: to communicate certain information to each other in written form. The information had to be set on a lightweight and durable medium that was easily transportable. The invention of paper allowed papyrus and parchment to be replaced with a material that was easier and, with the advent of new production techniques, cheaper to make.

The arrival of digital media has perhaps obscured the fundamental role that paper has played in spreading knowledge : it should not be forgotten that, until a few decades ago, the dissemination of any idea required a sheet of paper .

It’s interesting to note that the first definition of paper provided by the Treccani children’s encyclopaedia in Italy is: “A material that is essential for spreading ideas in everyday life. Over the centuries, paper has made an enormous contribution to progress, from enabling citizen participation in democratic life to raising levels of knowledge and education.”

The history of paper has mirrored the evolution of human society over the centuries: from the dissemination of scientific and philosophical knowledge to the spread of education right up to the creation of the kind of political and historical consciousness which gave birth of the modern nation state.

The history of paper: Chinese origins

Historical sources credit the invention of paper to Cai Lun, a dignitary serving the imperial Chinese court who, in AD 105, began producing sheets of paper from scraps of old rags , tree bark and fishing nets . The Chinese guarded the secret of paper making jealously for many centuries until, in the 6th century, their invention was brought to Japan by Buddhist monk Dam Jing. The Japanese immediately learned papermaking techniques and began using pulp derived from mulberry bark to produce this precious material themselves.

The history of paper: reaching the Arab world

The Arab world discovered the secrets of papermaking in AD 751, when the governor-general of the Caliphate of Bagdad captured two Chinese papermakers in Samarkand and, with their help, founded a paper mill in the Uzbek city. From here, aided by an abundance of hemp and linen , two high-quality raw materials perfect for making paper, production spread to other cities in Asia, particularly Baghdad and Damascus.

The process for making paper employed by the Arabs involved garnetting and macerating rags in water to obtain a homogenous pulp, which was then sifted to separate the macerated fibres from the water. The sheets thus obtained were subsequently pressed, dried and finally covered with a layer of rice starch to make them more receptive to ink. In the same period, people in Egypt and North Africa also started to make paper using the same techniques employed in the Arab world.

Paper reaches Europe

It wasn’t until the 11th century that paper arrived in Europe, with the Arab conquest of Sicily and Spain . However, paper was quickly considered an inferior-quality material compared to parchment, so much so that, in 1221, Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II prohibited its use for public documents. Rice starch, in fact, was an attractive food source for insects, which meant sheets of paper did not last long.

The history of paper owes much to the paper makers of Fabriano , a small town in the Marche region of Italy, who started producing paper using linen and hemp in the 12th century. By using new equipment and production techniques, these papermakers introduced important innovations :

- They mechanised rag grinding by using hydraulic hammer mills , significantly reducing the time it took to produce pulp.

- They started gluing sheets with gelatine, an additive that insects didn’t like.

- They created different paper types and formats .

- They invented watermarking .

Watermarking involved using metal wires to add decorations to paper which became visible when the sheet was held up to the light, allowing hallmarks, signatures, ecclesiastical emblems and other symbols to be inserted.

From the 14th century, papermaking began to spread to other European countries and, at the end of the 15th century, with the invention of movable-type printing , production really took off. The discovery of America and the subsequent European colonisation brought papermaking to the New World. Interestingly, in his book “ Paper: Paging Through History ”, Mark Kurlansky tells a curious anecdote: when the North American colonies rebelled, they boycotted all British goods, except the fine paper produced by London’s paper mills.

Paper as a means of mass communication

The industrial manufacture of paper began in the 19th century with the expansion of mass-circulation newspapers and the first best-selling novels, which required enormous quantities of cheap cellulose. In 1797, Louis Nicolas Robert created the first Fourdrinier machine, which was able to produce a 60-cm-long sheet. As demand for papermaking rags outstripped supply, alternative materials were sought, like wood pulp . With the development of new techniques for extracting fibres from trees, the price of paper fell dramatically, and paper soon became a product of mass consumption . In Britain alone, paper output soared from 96,000 tonnes a year in 1861 to 648,000 tonnes in 1900.

Once again, the history of paper and the history of humankind were closely intertwined: with the spread of cheap paper, books and newspapers became accessible to all, leading to an explosion of literacy among the middle classes . But it wasn’t until the turn of the century that paper would be employed for other uses, like toilet and wrapping paper, toys and interior decoration.

The environmental impact of paper and environmental choices

Paper manufacturing uses significant amounts of natural resources : between 2 and 2.5 tonnes of timber and 30-40 cubic metres of water are required to make one tonne of paper. What’s more, electricity and methane gas are needed to power the industrial machines used in the various production phases and, depending on the type of paper, a host of polluting chemical additives . That’s why, whenever possible, it’s important to choose sustainable or recycled paper to reduce the environmental impact of paper production.

Sustainable paper is made out of wood cellulose originating from Forest Stewardship Council-certified forests , where strict environmental, social and economic standards apply. Recycled paper , on the other hand, is made out of recovered paper. However, the chlorine used to bleach it, as well as other chemical additives used, mean that recycled paper is often not as environmentally friendly as commonly thought. To be sure that you are choosing a genuinely eco-friendly product, opt for paper with the Ecolabel certification , the European ecological quality label awarded to environmentally sustainable products.

Alternatives to paper

An excellent alternative to traditional paper is Crush paper, produced by venerable Italian papermakers Favini, made out of fruit and vegetable by-products . Production of this paper releases 20% fewer CO2 emissions and uses up to 15% less cellulose than traditional paper, and is suitable for many applications, from food and wine labels to premium-quality invitation cards, catalogues and brochures.

The latest innovation from Favini is Remake , paper made from 25% leather off-cuts , 40% recycled cellulose and 35% FSC-certified virgin cellulose fibres. It’s a fine-quality recyclable and compostable material, perfect for printing sophisticated publications and luxury packaging.

Another great substitute is hemp , a highly durable material that has been used to make paper since ancient times, first by the Chinese and later by the Arabs. Cultivation of this plant does not require pesticides and provides a quantity of fibre per hectare that is 3-4 times greater than traditional forests. Its main drawback is the cost of processing hemp pulp, which is much higher than conventional cellulose extraction.

Our article on the history of paper finishes here, but we’re sure that, thanks to continued technical innovation, many more surprises lie ahead! The history of paper is far from over, and this fascinating and useful material will remain with us for years to come.

- American History

- Ancient History

- European History

- Military History

- Medieval History

- Latin American History

- African History

- Historical Biographies

- History Book Reviews

- Sign in / Join

The First Paper: The Papyrus of Ancient Egypt

Though the manufacturing of paper has changed considerably over the years, the papyrus invented by the Egyptians was not altogether dissimilar from modern paper.

With the advent of modern computer systems and the popularity of electronic media, doesn’t it seem as if the world’s use of paper should be steadily decreasing as older forms of media are gradually phased out? As it turns out, over the past twenty years, paper use in the U.S. (the world’s largest consumer of paper) has increased by about 126%.

Things, in other words, seem to be working in a direction contrary to logic. Now, there are lots of answers as to why this may be, and surely there is a great deal of comfort to be gained from the fact that about half of all material used to make paper is recycled, and that number will surely rise even further as people are encouraged to recycle their waste paper.

So who was it, exactly, that started mankind on this journey toward the printed page and landfills full of waste paper?

The Earliest Paper

Like so many other things, we can blame (or credit) the ancient Egyptians for inventing paper.

In fact, the first paper known to historians does not actually seem all that antiquated, even compared to today’s world of micro-fiber security checking paper. While it does seem somewhat uneconomical and horribly time consuming to produce (at least, looking at it through modern eyes), the production and use of Papyrus in Egypt more than one thousand years B.C. appeared to be a fairly well-established system, and one which lasted for more than two thousand years as the primary source of paper in the world.

It wasn’t until the last century B.C. and first century A.D. that an additional form of paper, parchment (animal skins), began to give papyrus a run for its money as the primary writing surface of the time. Even then, papyrus remained invaluable for use in scrolls, while codices (ancient forms of bound books) were generally made using parchment.

Interestingly, the word papyrus (named for the plant from which it is produced) is the word from which the modern word paper was derived. Furthermore, most of the ancient papyrus plants were shipped through the Lebanese Mediterranean port-city of Byblos, which as a result was named for the Greek word for book, which is also the word which is the basis for such English words as Bible, Bibliography and Bibliophile.

The Ancient Paper-Making Process

In order to fashion a piece of papyrus paper out of papyrus plants, the following steps were taken by those ancient paper-makers: the stem of the plant, containing a sticky, fibrous stalk, was cut into long, thin strips, then laid down slightly overlapping each other on a hard surface after having been soaked in water for some time in order to aid in adhesion.

Another layer was then placed on top, perpendicular to the first. From here, the layers were hammered together until it was thin, smooth, and a single surface. Pressure was applied to the papyrus as it dried (a weight was often placed on top of it with a flat surface on the bottom), which takes several days. Lastly, the dried paper is smoothed and polished with whatever tools were available – usually stones or some other smooth object. And that’s it. To make a scroll, the process was similar, though obviously just a little more complicated and time consuming, as the pages then had to be joined end to end to make one long piece.

The Upside and the Downside

Papyrus was the ideal form of paper in the locations where it was originally used – Egypt and throughout the Middle East, for these are dry climates, and therefore the paper could hold up and be preserved for a considerable amount of time (such as in the famous case of the Dead Sea Scrolls, which held up more than two thousand years in such a climate. With the addition of any humidity, however, papyrus is not at all resistant to mold, which will quickly eat away and destroy the organic paper.

Needless to say, while papyrus was good while it lasted, and quite ingenious for its time, modern society has made such difficulties a thing of the past with our modern paper processing plants which churn out billions of pages every year.

While the process of paper making has changed considerably over the three thousand year history of paper, the product has remained surprisingly similar. Give an ancient Egyptian a piece of modern paper, and they would surely have no trouble figuring out its purpose, for their invention has truly withstood the test of time.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

The Babylonian Captivity: The Influence of King Nebuchadnezzar II on the Jewish Exiles

The Domestic Roots of Ancient Alchemy: Women’s Work and their Role in the Science of Alchemy

The Legend of Dido: How the Myth of Carthage’s Legendary Queen Evolved

Amazons – Who Were the Ancient Female Warriors?

The Kyrenia Ship: Her Last Voyage

Elephant Warriors in the Ancient World: Roman, Persian, Carthagenian and Mughal Armies with War Elephants

- Pantone Colors

Robert C. Williams Museum of Papermaking

Papermaking moves to the united states, the first mill in america.

The first paper mill in America was established in 1690 by William Rittenhouse near Germantown, Pennsylvania. In 1688, Rittenhouse left Holland, where he had been an apprentice papermaker, and settled in Philadelphia, near the print shop of William Bradford. The Rittenhouse mill remained the only mill in America until 1710, when William DeWees, brother-in-law to William Rittenhouse's son Nicholas, established his own mill.

Most early mills in the American colonies were started by transplanted papermakers, like Rittenhouse, who modeled their operations on European mills of the day. These mills had to be located near populated areas that could provide a reliable supply of rags, the main raw material at that time. A generous supply of fresh water was also a requirement, both for washing the fibers and turning the mill machinery.

Paper for Printing in the Colonies

Many colonial paper mills, such as the Rittenhouse mill, were also located near print shops. Even before they had a reliable supply of paper, however, the colonies had begun to publish newspapers. The first newspaper in the colonies was the Boston News Letter , which appeared in 1705; the second was the Boston Gazette , first published in 1719. The third, also dating from 1719, was Bradford's Mercury , which was published by Andrew Bradford, the son of printer William Bradford. To supply paper for the New York Gazette , William Bradford started a paper mill in New Jersey around 1726.

With the Stamp Act of 1765, Great Britain tried to raise revenue by taxing all colonial commercial and legal papers, newspapers, and pamphlets. Because of the export trade in paper, Britain attempted to restrict papermaking in the colonies, but due to the shortage of paper in America, these restrictions were not rigorously applied. It was only when colonial printers began to express their discontent with British rule that Britain really tried to control the production of paper.

Mold Making in the Colonies

Although some of the machinery used in early mills was imported from Europe, much of the machinery was constructed in the colonies. A high degree of craftsmanship was also required to create a paper mold; however, the lack of skilled mold makers in the colonies meant that many paper molds were imported from England.

Nathan Sellers of Pennsylvania was a skilled wire drawer who applied his craft to the manufacture of paper molds. Between 1776 and 1820, he supplied the molds for hundreds of American papermakers. This ability was so rare that, when Sellers joined the American army in the fall of 1776, he was soon discharged by a special resolution of the Contiental Congress, which sent him home to create the molds that were so desparately needed to make the paper used for powder wrappers and written orders during the Revolutionary War.

Paper Mill Construction After the Revolutionary War

By 1810, there were some 185 paper mills in the new United States. Ream wrappers were used to identify a mill's products, and they were often printed with a picture of the mill. As existing mills expanded and new mills began production, rags for making paper became scarce, and the search for more plentiful raw materials began.

American papermakers began experimenting with alternative raw materials as early as the 1790's, and many mills tested local sources of fiber as substitutes for rag pulp, including tree bark, bagasse (sugarcane waste), straw, and cornstalks. Wood pulp became a viable option thanks to the work of Mathias Koops in England and the increasing availability of mechanical wood grinders. The first US newspaper to be printed on paper made from ground wood pulp was the edition of the Boston Weekly Journal that appeared on January 14, 1863.

The Modern Paper Mill

The modern paper mill is a highly complex industrial facility. Although the principles of papermaking have not fundamentally changed for many years, a papermaker from Imperial China or pre-industrial Europe would be hard pressed to recognize his craft amongst all the equipment of a modern mill. To explore how a present-day paper mill operates, let's follow the path of an individual wood fiber from its arrival at the mill to its departure.

Delivery and Preparation

Most of the mill's raw material arrives by truck or rail in the form of logs. The logs are soaked in water and tumbled in slatted metal drums to remove the bark. The debarked logs are then fed into a chipper, a device with a rotating steel blade that cuts the wood into pieces about 1/8" thick and 1/2" square. (In some cases, the wood may have been chipped, bark and all, when it was harvested.) The wood chips are stored in a pile outside the mill; as new chips are added to the top of the pile, others are withdrawn from the bottom and carried by conveyor to the digester.

Digesting is the process of removing lignin and other components of the wood from the cellulose fibers which will be used to make paper. Lignin is the "glue" which holds the wood together; it rapidly decomposes and discolors paper if it is left in the pulp (as in newsprint, which is usually made from groundwood pulp with little or no chemical treatment). Since this is a "kraft" mill, the lignin is removed by the action of sodium hydroxide ("caustic soda") and sodium sulfate under heat and pressure. The chips are fed into the top of a digester and mixed with the cooking chemicals, which are called "white liquor" at this point. As the chips and liquor move down through the digester, the lignin and other components are dissolved, and the cellulose fibers are released as pulp. At the bottom of the digester, the pulp is rinsed, and the spent chemicals (now known as "black liquor") are separated and recycled.

Bleaching and Refining

At this point, the "brownstock" pulp is free of lignin, but is too dark to use for most grades of paper. The next step is therefore to bleach the pulp by treating it with chlorine, chlorine dioxide, ozone, peroxide, or any of several other treatments. A typical mill uses multiple stages of bleaching, often with different treatments in each step, to produce a bright white pulp. Chlorine bleaching generally provides the best performance with the least damage to the fibers, but concerns about dioxins and other byproducts have led the industry to move towards more environmentally friendly alternatives.

At this point, the individual cellulose fibers are still fairly hollow and stiff, so they must be broken down somewhat to help them stick to one another in the paper web. This is accomplished by "beating" the pulp in the refiners, vessels with a series of rotating serrated metal disks. The pulp will be beaten for various lengths of time depending on its origin and the type of paper product that will be made from it. At the end of the process, the fibers will be flattened and frayed, ready to bond together in a sheet of paper.

Forming the Sheet

Once the pulp has been bleached and refined, it is rinsed and diluted with water, and fillers such as clay or talc may be added. This "furnish", containing 99% water or more, is pumped into the headbox of the paper machine. From the headbox, the furnish is dispensed through a long, narrow "slice" onto the "wire", a moving continuous belt of wire or plastic mesh. As it travels down the wire, much of the water drains away or is pulled away by suction from underneath. The cellulose fibers, trapped on the wire as the water drains away, adhere to one another to form the paper web. From the wire, the newly formed sheet of paper is transferred onto a cloth belt (or "felt") in the press section, where rollers squeeze out much of the remaining water.

Coating, Drying, and Calendering

After leaving the press section, the sheet encounters the drying cylinders. These are large hollow metal cylinders, heated internally with steam, which dry the paper as it passes over them. The sheet will be wound up and down over many cylinders in the drying process. Between dryer sections, the paper may be coated with pigments, latex mixtures, or many other substances to give it a higher gloss or to impart some other desirable characteristic. After another round of drying, the paper sheet is passed through a series of polished, close-stacked metal rollers known as a "calender" where it is pressed smooth. Finally, the sheet is collected on a take-up roll and removed from the paper machine. From the headbox, it may have traveled half a mile or more in less than a minute.

Cutting and Packaging

In many cases, the new paper roll is simply rewound on a new core, inspected, and shipped directly to the customer. Other paper grades, however, may be further smoothed by passing them through a "supercalender" where the sheet is polished by passing between steel and hard cotton rollers (much like ironing fabric), or they may be embossed with a decorative pattern. The paper may also be cut into sheets at the mill, often by automatic equipment which accepts a roll of paper at one end and delivers packages of cut sheets at the other, already boxed and wrapped for shipping.

Papermaking today is one of North America's most capital-intensive industries, devoting large sums of money to the development and construction of newer and more efficient equipment and processes. Although we ourselves might not recognize the paper mills of three hundred years from now, the same basic processes will almost certainly be in use to produce a product that will still be in demand far into the future.

< Invention of Papermaking

Watermarks >.

The Story of Paper

- Apple Podcasts

Christy VanArragon and Joshua Leo look at the history and future of paper – one of the most important materials in history.

Welcome to Spotlight. I’m Christy VanArragon

And I’m Joshua Leo. Spotlight uses a special English method of broadcasting. It is easier for people to understand, no matter where in the world they live.

Every day more people in the world use computers and other technology to communicate. Many books are now available on the internet. People write emails, and text messages, instead of letters. In many places, people do not even use physical money to pay for things any more. All these technologies are replacing one of the most important materials in history: paper. Today’s Spotlight is on paper, its history and its importance in the world today.

Many people believe that paper started with the ancient Egyptians. However, this is not exactly true. Instead, 5000 years ago, Egyptians used a material called papyrus. They made papyrus from the stems of river plants. They put these flat pieces together, to create a larger flat sheet. Ancient Egyptians wrote on these sheets like paper.

But the paper we know today did not exist until 3000 years later. It was created in China. Before the invention of paper, people in China would write on pieces of bone, bamboo or costly cloth. No one knows who first invented paper. But history does tell us about one man who improved the process. It was in the year 105. A man named Cai Lun began to experiment. He used many materials to make paper. He took bark from the outside of trees, pieces of net normally used to catch fish, and pieces of cloth rags. He broke these materials down into very small pieces. He put all these materials into a large container of water, to mix them. Then he removed this material, using a screen. When he pressed out the water, all that was left was a thin sheet of paper. He presented this new way of making paper to the Emperor. The Emperor was very happy and gave Cai Lun much money.

Paper quickly spread to other areas of the world. In the Middle East, people made paper thicker. They also made it easier to produce quickly. From the Middle East, paper travelled to Europe and then the Americas. For many years paper cost a lot of money and time to create. But in the 19th century, people began to use steam powered machines to create paper from wood. Paper is still made from wood today in large factories around the world.

Paper changed the way people lived. Long ago, when paper was difficult to make, people only used paper for special purposes. Religious leaders would write holy words on it. Government officials would write important laws on it. Explorers drew maps of the world on it. But normal, common people did not use it. As paper became easier to make, it was used for more things. People wrapped it around gifts. Anyone could use paper to make notes and write down information. Paper was also used as money.

Today people use paper for even more things. Paper cloths clean up dirt. Many products are sold in cardboard boxes made from paper. People drink water and other drinks out of paper cups.

But this creates a new problem – the problem of waste. When we are done using paper, it does not just disappear. Some paper can be recycled – it can be made into new paper. But a lot of paper simply becomes waste, or garbage. It is burned for energy, or stored in large landfills. Paper does biodegrade, or break down over time but it does not happen quickly. As the paper breaks down it releases harmful gasses into the air. In the United States, paper makes up one third of all waste. In just that country, that is 85 million tons per year!

But this is not the only problem that paper can cause. In the past, paper included materials from cloth, waste paper, and other fibres from plants. But today, most paper comes from trees. Many of these trees come from very old forests around the world. Today, only 20 percent of the world’s ancient forests still exist. Around the world, every two seconds, people cut down more than 4,000 square meters of trees. And many of those trees became paper.

These ancient forests cannot be replaced. Forests provide oxygen for animals and humans. They store the gas carbon dioxide, which can cause global warming. Cutting down trees can also destroy environmental systems. The birds, plants and animals that live there may also die. Some companies plant new trees when they cut down forests. But it takes a long time for new trees to grow. Often, these newly planted trees are all the same kind of tree. This is called a monoculture. A monoculture forest can get diseases easier. If one tree gets sick, all the same kind of trees get sick. When forests have many different kind of trees, they can resist disease easier.

Creating the paper can also cause environmental problems. Large paper factories use chemicals to make paper white. They also use a lot of water to create the paper. The chemicals pollute the water. If the factories release the water without removing the chemicals, the water can then pollute rivers and lakes. The chemicals in the water can also cause health problems.

So what can be done to help reduce the number of trees being cut down for paper? What can a person do to change their paper impact on the world?

The first step is to try to use less paper. Could you clean with a cloth instead of paper? Can you use less paper in your office or home? Can you re-use the paper used to cover a gift?

Next, look at the kind of paper you use. Most paper can be reused in some way. Old paper can be turned into new paper through recycling. By recycling paper like this, less trees have to be cut down. It takes less energy to recycle paper than it does to make new paper from trees. Are there ways to recycle paper where you live?

Many companies make products from post-consumer materials. This means that instead of cutting down trees to make the paper products, they use recycled paper. Buying these recycled paper products can save a lot of trees, water and energy.

In many places, people can also buy paper that comes from forests that are sustainably harvested. This means that when the trees in these forests are cut down, people make sure that it will not damage the environment of the forest.

Paper has been an important part of history. It has made many things possible. And even though people are using less paper, it is still very important to us today. But it is up to us to make sure that paper does not harm the world. It is our responsibility to give it a positive future.

The writer and producer of this program was Joshua Leo. The voices you heard were from the United States. You can find our programs on the Internet at www.radioenglish.net . This program is called ‘The Story of Paper’.

We hope you can join us again for the next Spotlight program. Goodbye.

What kinds of paper do you use every day? Do you use a lot or a little? Write your answer in the comments below.

Join the discussion Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

27 comments

I use thin paper and always try to economize with it.

I have a great desire to write , so I consume a lot of a paper. fortunately in my country . The Paper ist recycling.

I use PDF instead of the paper and use a little it I love forests I hobe forests and jungle be an important thing in our live

1_colored pepars

2_Iam use pepars a lot but not use evry day

We should love trees because it cleans the air we breathe.

I use white papers, I used a lot of paper before reading this article I will try to reduce the use of paper in my life, thanks for this beautiful article

Hello. I try to use recycled papers but sometimes I use new papers, unfortunately. But all kinds of papers which I usually use I try to recycle.

Thanks a lot Sportlight!

I used a lot of things by paper , like : paper cups , toilet paper, and my books it made by paper

I use paper but not very much, I buy two or Three books and I use it for study, but now usually I use phone or computer to study but I still use paper.

until now i use white paper for my assessment insted of laptop because i have not. I’m a university student who is not own laptop or computer. i use a lot of paper when i draw the pictures more than study in my spare time.

I use a little paper everyday. I usually use white paper. When I don’t use paper anymore, I usually collect and sell it to the soaring iron collectors for the purpose of recycling.

thank you! that was informative!!

i will use less paper, thanks spotlight

I used to fine art paper and white paper everyday. fine art paper is quite expensive so i use it sparingly. White paper is cheaper than fine art paper, i usually use it. But now, when i need to write something i choose work on laptop, It’s more convenient and saves moneybuy paper.

Thanks spotlights on this bod cast I well lighten use paper

Before I became a university student, I was still a high school student, and I used a lot of paper to learn or write whatever I wanted to write. White paper is the type of paper that I use on adaily because it is very popular. And then I already became a university student, and I use less paper now that I have a laptop and a smartphone to read ebooks online or take notes on something

I uses a paper little but is important for life

Actually, I don’t know any kind paper used .But I know that I used a lot paper a specially when clean the house or use bathroom .I am trying when go the store choose producer of paper recycle. This best way can.Any person does it. This way help in reducing pollution environment

I used the recycle papers. I used paper a little .

when I was student is I use alot of papers in studying books and copy book but now I’m not use any paper thank you for this episode

usually l use thin paper just when i studying and do the homework, and I always try to used a little of paper.

This is beg proplem

I use alot of papers to make summaries

I often use tissues papers everyday. In my company, we always use white paper for printing documents, but recently we are using less paper, only printing these necessary things. If we are change to use recycle paper, we will save a lot of money, trees, water and energy every month.

I using the normal paper. Yes i using a lot of paper everyday because the natural of my work is I am civil engineer and I requires to print the drawing during I am in my site office.

I use a lot of white paper evey day ,that’s because I need them for my studying, but from now on I will try to use the digital papers.

Are there digital papers ?

More from this show

The Town that Lost its Cheese

Colin Lowther and Marina Santee talk about cheddar cheese, where it came from and its interesting history.

Stones for Remembering

In recognition of the UN’s “International Day of Commemoration of the Victims of the Holocaust” Ryan Geertsma and Robin Basselin look at...

Famous Bells Around the World

Have you heard of the idiom, ‘ringing in the new year’? It used to be the custom to ‘ring out’ the old year with bells. There’s an 1850...

Truth and Reconciliation for Canada

In Canada, there is a long, sad history of abuse towards native people. Bruce Gulland and Megan Nollet look at this terrible history, and...

The East-West Position Clock

Mike Procter and Liz Waid tell about clockmaker John Harrison. He invented a way for ships to know their East-West position at sea.

History of the Bicycle

Christy VanArragon and Bruce Gulland tell the history of one of the most important inventions in history - the bicycle!

- Android App

Recent Posts

- World Health Day | Why Being Kind Can Make You Healthy

- The Easter Story, Part 2

- The Easter Story, Part 1

- World Meteorological Day | The First Time Ever

- World Poetry Day | The Life and Art of William Carlos Williams

- 10 Ways to Fight Hate Series

- English Learning

- Film & Television

- Food & Drink

- Good Stories

- Health & Medicine

- International UN Days

- Relationships

- Science and Technology

- Staff Favorites

- The Environment

- The Internet

- Tips for Health Series

- Uncategorized

- Work and Business

- About Spotlight

- New to Spotlight

- Privacy Policy

- Recommended Resources

- Spotlight Advanced

- Testimonials

- We are sorry!

The History and Invention of the Paperclip

B_Me/Pixabay

- Famous Inventions

- Famous Inventors

- Patents & Trademarks

- Invention Timelines

- Computers & The Internet

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

Historical references describe fastening papers together as early as the 13th century. During this time, people put ribbon through parallel incisions in the upper left-hand corner of pages. Later, people started to wax the ribbons to make them stronger and easier to undo and redo. This was the way people clipped papers together for the next six hundred years.

In 1835, a New York physician named John Ireland Howe invented the machine for mass-producing straight pins, which then became a popular way to fasten papers together (although they were not originally designed for that purpose). Straight pins were designed to be used in sewing and tailoring, to temporally fasten cloth together.

Johan Vaaler

Johan Vaaler, a Norwegian inventor with degrees in electronics, science, and mathematics, invented the paperclip in 1899. He received a patent for his design from Germany in 1899, as Norway had no patent laws at that time.

Vaaler was an employee at a local invention office when he created the paperclip. He received an American patent in 1901. The patent abstract says, "It consists of forming same of a spring material, such as a piece of wire, that is bent to a rectangular, triangular, or otherwise shaped hoop, the end parts of which wire piece form members or tongues lying side by side in contrary directions." Vaaler was the first person to patent a paperclip design, although other unpatented designs might have existed first.

American inventor Cornelius J. Brosnan filed for an American patent for a paperclip in 1900. He called his invention the "Konaclip."

A History of Paperclips

It was a company called the Gem Manufacturing Ltd. of England that first designed the double oval-shaped, standard paperclip. This familiar and famous paperclip was and still is referred to as the "Gem" clip. William Middlebrook of Waterbury, Connecticut, patented a machine for making paperclips of the Gem design in 1899. The Gem paperclip was never patented.

People have been re-inventing the paperclip over and over again. The designs that have been the most successful are the Gem with its double oval shape, the "non-skid" which held in place well, the "ideal" used for thick wads of paper , and the "owl" paperclip that does not get tangled up with other paperclips.

World War II Protest

During World War II, Norwegians were prohibited from wearing any buttons with the likeness or initials of their king on them. In protest, they started wearing paperclips, because paperclips were a Norwegian invention whose original function was to bind together. This was a protest against the Nazi occupation and wearing a paperclip could have gotten them arrested.

A paperclip's metal wire can be easily unfolded. Several devices call for a very thin rod to push a recessed button which the user might only rarely need. This is seen on most CD-ROM drives as an "emergency eject" should the power fail. Various smartphones require the use of a long, thin object such as a paperclip to eject the SIM card. Paperclips can also be bent into a sometimes effective lock-picking device. Some types of handcuffs can be unfastened using paper clips.

- History of the Sewing Machine

- The History of the Jet Engine

- The History of Radio Technology

- Biography of Thomas Adams, American Inventor

- Today in History: Inventions, Patents, and Copyrights

- The History of the ENIAC Computer

- Who Invented Peanut Butter?

- Introduction to Pop: The History of Soft Drinks

- History of Computer Printers

- Samuel Morse and the Invention of the Telegraph

- Reading Comprehension for Beginners - My Office

- May Themes and Holiday Activities for Elementary School

- A Brief History of the Invention of Plastics

- The Failed Inventions of Thomas Alva Edison

- Inventions and Inventors of the Agricultural Revolution

- The Invention of the Coat Hanger

On The Site

John Coventry (1943), active 1971 – . Marbled collage, early 1970s. Oil - marbled, spray - painted motifs and collage astronaut figure, on upcycled binders’ board , 19 ¼ x 23 ¼ in. (48.9 x 59.1 cm).

Documenting History: The Paper Legacy Project

January 17, 2023 | tlb76 | American History , Art & Architecture

Mindell Dubansky —

Who in my field had received the attention they deserve; and whose artistic contributions might disappear from the history of the book in the near future? How can I utilize my own half-century experience as an artist, book conservator and preservation librarian to collect, contextualize and share the chosen subject with the public, researchers and artists? These are the questions I asked myself as I pondered my desire to pay homage to the book and paper artists who have contributed to our culture for the last fifty years. This is what motivated me to build a collection of modern American hand-decorated papers and to document their commercial uses and the professional lives of their makers. The result of this project came to be known as the Paper Legacy Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Thomas J. Watson Library. Upon completion of the collection, Pattern and Flow. A Golden Age of American Decorated Paper, 1960s to 2000s , the first monograph published by the Museum’s library, was created to share this special resource with all of you.

The Paper Legacy Collection began in 2017. My objective was to assemble original materials relating to the most notable American artists active from the midpoint to the turn of the twentieth century, centered around a collection of full sheets of decorated paper in various techniques, as selected and described by the makers themselves. I also endeavored to document the cultural and economic conditions that allowed the artists to flourish during this period. A resource of this kind, I knew, would serve historians and practicing artists long into the future. As it stands today, the collection represents over fifty artists who worked in many styles and techniques, and in all regions of the United States; two of which have worked principally in Canada. Further, it records details of their lives and published writings, and includes examples of their custom tools and archival materials that illustrate the world of paper arts they created.

I began to shape the project by developing a list of makers whose reputations I knew from working as a hand bookbinder in New York since the late 1970s. I scanned the literature of the period noting additional possible participants and consulted with artists and vendors about the people and events they felt were influential on a national level. The cultural map that emerged indicated that professional decorated paper making occurred in loosely connected pockets around the United States, and that the artists involved by the early 1980s were largely responsible for the international conferences, research, publications, workshops, and equipment that helped the craft to prosper. With my list complete, I reached out to the artists with the aim of learning how decorated paper was transformed from a dying art in the late 1960s to a flourishing, nationwide phenomenon by the late 1980s.

In the course of creating the Paper Legacy Collection, I learned that the artists are a collaborative, and industrious group. Because they are experimenters and accustomed to viewing their work as something to be used by others, humility and a pragmatic orientation are common attributes. Professional paper artists and artisans are found in all regions of the US. Many artists included in Pattern and Flow were aesthetically influenced by their home environments, whether natural or urban. They did not adopt the styles of contemporary art movements, apart from a few drawn to the graphic art of the American counterculture or mid-century abstract art. Rather, most found inspiration in their direct encounters with the decorative processes, materials, and methods. All were motivated by beauty and technical perfection. Some took a historical approach, creating traditionally patterned papers with paints made from traditional, often organic, ingredients; others preferred to create modern versions of patterns using modern materials. Each of these groups created both one-of-a-kind papers and multiple sheets with a similar design, or so-called production papers. Other artists took a highly experimental approach, making one-of-a-kind papers using nontraditional materials—such as industrial paints and cooking condiments—to create unusual visual effects. Many of the artists defy categorization and worked, or are still working, in a variety of techniques and styles. The techniques used to create the papers include marbling, paste paper, and other various painting and printmaking approaches. While these methods are grounded in the traditional decorated paper techniques practiced globally for centuries, this new generation both rediscovered and reinvented paper decoration and surface design with a fresh vitality and freedom of expression. The result has been an efflorescence of new and glorious designs which found their way into the daily fabric of our lives.

The decorated paper phenomenon coincided with a proliferation of the book arts in North America—a natural connection, given that hand bookbinding has traditionally incorporated decorated paper s as covering material and endpapers. Yet, over the ensuing decades, decorated paper arts grew far beyond their role in service to books, with the papers beautifying objects from boxes to walls, including commercial products, and the techniques applied to fabrics and other materials. For example, Paper Legacy artists created package designs for Coty and Kimberly-Clark Corporation, giftwrap for Hallmark, bed sheets for Martex, and home furnishings for Ethan Allen.

The same artists also produced beautiful hand-marbled papers for use by the country’s finest small press publishers, such as the Arion Press in San Franciso, California and Walter Hamady’s Perishable Press in Madison, Wisconsin, as well as commercial publishers, such as Alfred A. Knopf and Harper Collins. Many also created small editions of papers for prestigious institutions, including the White House.

Many artists in the Paper Legacy Collection remain active, and new artists are still entering the field. Others have retired or passed away. In the US, most papers are now sold online as brick-and-mortar outlets have decreased. There is also an apparent shift away from making production papers toward creating one-of-a-kind or small-edition graphic art using the same techniques as before. An example of this is Robert Wu’s Daisy Garden . The decorated paper arts have survived for centuries, through cycles of popularity and disinterest. The Watson Library’s Paper Legacy Collection preserves and documents works made by the most prominent artists working since the 1960s. We encourage you to explore the collection in person and online at https://www.metmuseum.org/paperlegacy .

Mindell Dubansky is museum librarian for preservation, Sherman Fairchild Center for Book Conservation, Thomas J. Watson Library, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Recent Posts

- The High-Tech Revolution is Transforming the Very Foundations of Human Existence

- Provincials, Light and Grass

- Earth Month Reading List 2024

- The Women, Men, and Children of the 1984–85 UK Miners’ Strike

- Ep. 133 – The Search for a Forgotten Architect

- Making the World at Home

Sign up for updates on new releases and special offers

Newsletter signup, shipping location.

Our website offers shipping to the United States and Canada only. For customers in other countries:

Mexico and South America: Contact TriLiteral to place your order. All Others: Visit our Yale University Press London website to place your order.

Shipping Updated

Learn more about Schreiben lernen, 2nd Edition, available now.

Advertisement

What Solar Eclipse-Gazing Has Looked Like for the Past 2 Centuries

Millions of people on Monday will continue the tradition of experiencing and capturing solar eclipses, a pursuit that has spawned a lot of unusual gear.

- Share full article

By Sarah Eckinger

- April 8, 2024 Updated 12:37 p.m. ET

For centuries, people have been clamoring to glimpse solar eclipses. From astronomers with custom-built photographic equipment to groups huddled together with special glasses, this spectacle has captivated the human imagination.

Creating a Permanent Record

In 1860, Warren de la Rue captured what many sources describe as the first photograph of a total solar eclipse . He took it in Rivabellosa, Spain, with an instrument known as the Kew Photoheliograph . This combination of a telescope and camera was specifically built to photograph the sun.

Forty years later, Nevil Maskelyne, a magician and an astronomy enthusiast, filmed a total solar eclipse in North Carolina. The footage was lost, however, and only released in 2019 after it was rediscovered in the Royal Astronomical Society’s archives.

Telescopic Vision

For scientists and astronomers, eclipses provide an opportunity not only to view the moon’s umbra and gaze at the sun’s corona, but also to make observations that further their studies. Many observatories, or friendly neighbors with a telescope, also make their instruments available to the public during eclipses.

Fredrik Hjalmar Johansen, Fridtjof Nansen and Sigurd Scott Hansen observing a solar eclipse while on a polar expedition in 1894 .

Women from Wellesley College in Massachusetts and their professor tested out equipment ahead of their eclipse trip (to “catch old Sol in the act,” as the original New York Times article phrased it) to New London, Conn., in 1922.

A group from Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania traveled to Yerbaniz, Mexico, in 1923, with telescopes and a 65-foot camera to observe the sun’s corona .

Dr. J.J. Nassau, director of the Warner and Swasey Observatory at Case School of Applied Science in Cleveland, prepared to head to Douglas Hill, Maine, to study an eclipse in 1932. An entire freight car was required to transport the institution’s equipment.

Visitors viewed a solar eclipse at an observatory in Berlin in the mid-1930s.

A family set up two telescopes in Bar Harbor, Maine, in 1963. The two children placed stones on the base to help steady them.

An astronomer examined equipment for an eclipse in a desert in Mauritania in June 1973. We credit the hot climate for his choice in outfit.

Indirect Light

If you see people on Monday sprinting to your local park clutching pieces of paper, or with a cardboard box of their head, they are probably planning to reflect or project images of the solar eclipse onto a surface.

Cynthia Goulakos demonstrated a safe way to view a solar eclipse , with two pieces of cardboard to create a reflection of the shadowed sun, in Lowell, Mass., in 1970.

Another popular option is to create a pinhole camera. This woman did so in Central Park in 1963 by using a paper cup with a small hole in the bottom and a twin-lens reflex camera.

Amateur astronomers viewed a partial eclipse, projected from a telescope onto a screen, from atop the Empire State Building in 1967 .

Back in Central Park, in 1970, Irving Schwartz and his wife reflected an eclipse onto a piece of paper by holding binoculars on the edge of a garbage basket.

Children in Denver in 1979 used cardboard viewing boxes and pieces of paper with small pinholes to view projections of a partial eclipse.

A crowd gathered around a basin of water dyed with dark ink, waiting for the reflection of a solar eclipse to appear, in Hanoi, Vietnam, in 1995.

Staring at the Sun (or, How Not to Burn Your Retinas)

Eclipse-gazers have used different methods to protect their eyes throughout the years, some safer than others .

In 1927, women gathered at a window in a building in London to watch a total eclipse through smoked glass. This was popularized in France in the 1700s , but fell out of favor when physicians began writing papers on children whose vision was damaged.

Another trend was to use a strip of exposed photographic film, as seen below in Sydney, Australia, in 1948 and in Turkana, Kenya, in 1963. This method, which was even suggested by The Times in 1979 , has since been declared unsafe.

Solar eclipse glasses are a popular and safe way to view the event ( if you use models compliant with international safety standards ). Over the years there have been various styles, including these large hand-held options found in West Palm Beach, Fla., in 1979.

Parents and children watched a partial eclipse through their eclipse glasses in Tokyo in 1981.

Slimmer, more colorful options were used in Nabusimake, Colombia, in 1998.

In France in 1999.

And in Iran and England in 1999.

And the best way to see the eclipse? With family and friends at a watch party, like this one in Isalo National Park in Madagascar in 2001.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 01 April 2024

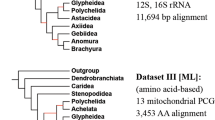

Complexity of avian evolution revealed by family-level genomes

- Josefin Stiller ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6009-9581 1 ,

- Shaohong Feng ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2462-7348 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ,

- Al-Aabid Chowdhury 6 ,

- Iker Rivas-González ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0515-0628 7 ,

- David A. Duchêne ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5479-1974 8 ,

- Qi Fang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9181-8689 9 ,

- Yuan Deng 9 ,

- Alexey Kozlov ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7394-2718 10 ,

- Alexandros Stamatakis ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0353-0691 10 , 11 , 12 ,

- Santiago Claramunt ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8926-5974 13 , 14 ,

- Jacqueline M. T. Nguyen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3076-0006 15 , 16 ,

- Simon Y. W. Ho ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0361-2307 6 ,

- Brant C. Faircloth ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1943-0217 17 ,

- Julia Haag ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7493-3917 10 ,

- Peter Houde ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4541-5974 18 ,

- Joel Cracraft ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7587-8342 19 ,

- Metin Balaban 20 ,

- Uyen Mai 21 ,

- Guangji Chen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9441-1155 9 , 22 ,

- Rongsheng Gao 9 , 22 ,

- Chengran Zhou ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9468-5973 9 ,

- Yulong Xie 2 ,

- Zijian Huang 2 ,

- Zhen Cao 23 ,

- Zhi Yan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2433-5553 23 ,

- Huw A. Ogilvie ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1589-6885 23 ,

- Luay Nakhleh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3288-6769 23 ,

- Bent Lindow ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1864-4221 24 ,

- Benoit Morel 10 , 11 ,

- Jon Fjeldså ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0790-3600 24 ,

- Peter A. Hosner ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7499-6224 24 , 25 ,

- Rute R. da Fonseca ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2805-4698 25 ,

- Bent Petersen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2472-8317 8 , 26 ,

- Joseph A. Tobias ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2429-6179 27 ,

- Tamás Székely ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2093-0056 28 , 29 ,

- Jonathan David Kennedy 30 ,

- Andrew Hart Reeve ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5233-6030 24 ,

- Andras Liker 31 , 32 ,

- Martin Stervander ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6139-7828 33 ,

- Agostinho Antunes ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1328-1732 34 , 35 ,

- Dieter Thomas Tietze ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6868-227X 36 ,

- Mads Bertelsen 37 ,

- Fumin Lei ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9920-8167 38 , 39 ,

- Carsten Rahbek ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4585-0300 25 , 30 , 40 , 41 ,

- Gary R. Graves ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1406-5246 30 , 42 ,

- Mikkel H. Schierup ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5028-1790 7 ,

- Tandy Warnow 43 ,

- Edward L. Braun ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1643-5212 44 ,

- M. Thomas P. Gilbert ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5805-7195 8 , 45 ,

- Erich D. Jarvis 46 , 47 ,

- Siavash Mirarab ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5410-1518 48 &

- Guojie Zhang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6860-1521 2 , 3 , 5 , 49

Nature ( 2024 ) Cite this article

9377 Accesses

866 Altmetric