Seminar Paper Research

- Topic Selection

- Preemption Checking

- Guides to Academic Legal Writing

- Interdisciplinary Research

- Evaluating Authority

- Writing the Abstract

- Problems in Constitutional Law Seminar Resources

- Food Law and Policy

- Gender and Criminal Justice Resources

- Equality and Sports

Tips for Writing an Abstract

The abstract is a succinct description of your paper, and the first thing after your title that people read when they see your paper. Try to make it capture the reader's interest.

Outline of Abstract:

Paragraph 1

- Sentence 1: One short sentence, that uses active verbs and states the current state of things on your topic.

- Sentence 2: Describe the problem with the situation described in sentence one, possibly including a worst-case-scenario for what will happen if things continue in their current state.

- Sentence 3: In one sentence, describe your entire paper--what needs to be done to correct the problem from Sentence 1 and avoid the disaster from Sentence 2?

- Sentence 4: What has been written about this? If there is a common consensus among legal scholars, what is it? (Note any major scholars who espouse this vision).

- Sentence 5: What are those arguments missing?

Paragraph 2 :

- Sentence 1-3: How would you do it differently? Do you have a theoretical lens that you are applying in a new way?

- Sentence 4: In one sentence, state the intellectual contribution that your paper makes, identifying the importance of your paper.

(from " How to Write a Good Abstract for a Law Review Article ," The Faculty Lounge, 2012).

Sample Student Abstracts

The following abstracts are from student-written articles published in Law Reviews and Journals. These abstracts are from articles that were awarded a Law-Review Award by Scribes: The American Society of Legal Writers . You can find more examples of student-written articles by searching the Law Journal Library in HeinOnline for the phrase "J.D. Candidate."

Mary E. Marshall, Miller v. Alabama and the Problem of Prediction, 119 Colum. L. Rev. 1633 (2019) .

Joseph DeMott, Rethinking Ashe v. Swenson from an Originalist Perspective, 71 Stan. L. Rev. 411 (2019)

Julie Lynn Rooney, Going Postal: Analyzing the Abuse of Mail Covers Under the Fourth Amendment, 70 Vand. L. Rev. 1627 (2017).

Michael Vincent, Computer-Managed Perpetual Trusts, 51 Jurimetrics J. 399 (2011).

Other research guides.

NYU Researching & Writing a Law Review Note or Seminar Paper: Writing

The Writing Process

- << Previous: Evaluating Authority

- Next: Outline >>

- Last Updated: Jan 25, 2024 3:32 PM

- URL: https://guides-lawlibrary.colorado.edu/c.php?g=1112479

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

Published on February 28, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 18, 2023 by Eoghan Ryan.

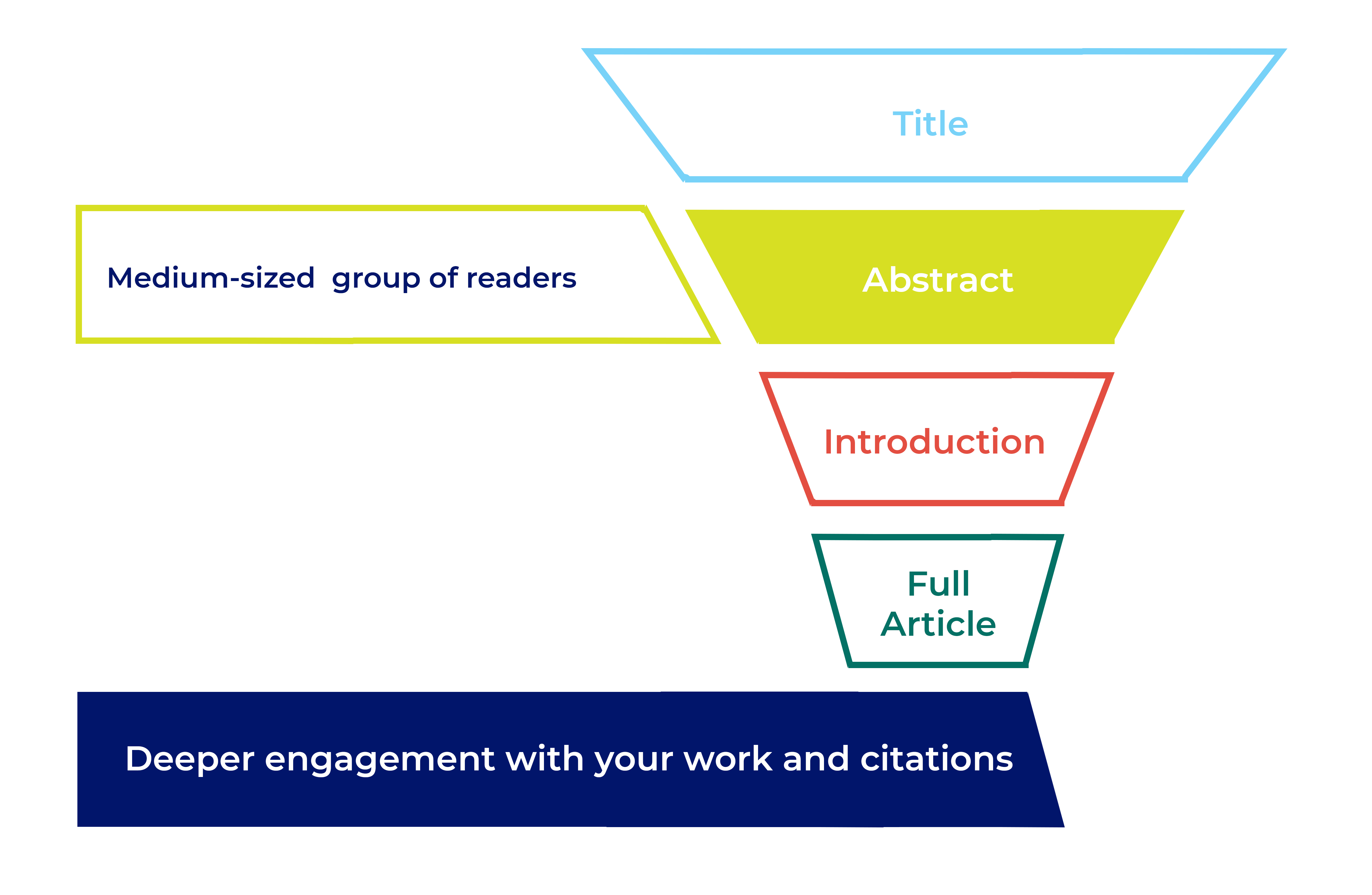

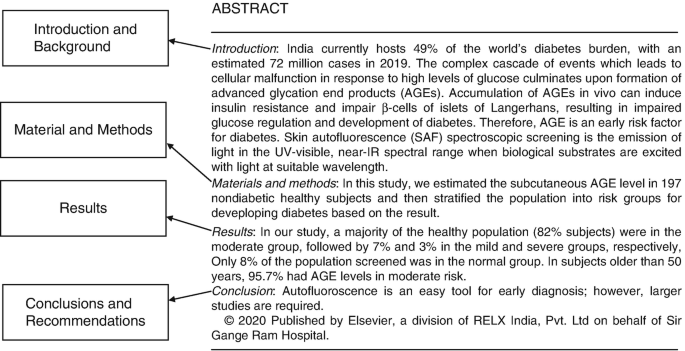

An abstract is a short summary of a longer work (such as a thesis , dissertation or research paper ). The abstract concisely reports the aims and outcomes of your research, so that readers know exactly what your paper is about.

Although the structure may vary slightly depending on your discipline, your abstract should describe the purpose of your work, the methods you’ve used, and the conclusions you’ve drawn.

One common way to structure your abstract is to use the IMRaD structure. This stands for:

- Introduction

Abstracts are usually around 100–300 words, but there’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check the relevant requirements.

In a dissertation or thesis , include the abstract on a separate page, after the title page and acknowledgements but before the table of contents .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Abstract example, when to write an abstract, step 1: introduction, step 2: methods, step 3: results, step 4: discussion, tips for writing an abstract, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about abstracts.

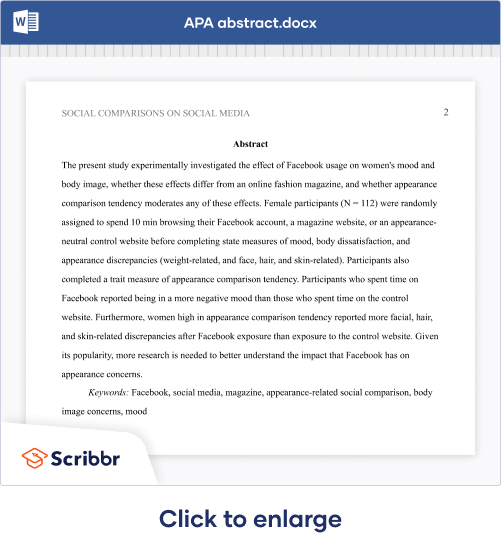

Hover over the different parts of the abstract to see how it is constructed.

This paper examines the role of silent movies as a mode of shared experience in the US during the early twentieth century. At this time, high immigration rates resulted in a significant percentage of non-English-speaking citizens. These immigrants faced numerous economic and social obstacles, including exclusion from public entertainment and modes of discourse (newspapers, theater, radio).

Incorporating evidence from reviews, personal correspondence, and diaries, this study demonstrates that silent films were an affordable and inclusive source of entertainment. It argues for the accessible economic and representational nature of early cinema. These concerns are particularly evident in the low price of admission and in the democratic nature of the actors’ exaggerated gestures, which allowed the plots and action to be easily grasped by a diverse audience despite language barriers.

Keywords: silent movies, immigration, public discourse, entertainment, early cinema, language barriers.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

You will almost always have to include an abstract when:

- Completing a thesis or dissertation

- Submitting a research paper to an academic journal

- Writing a book or research proposal

- Applying for research grants

It’s easiest to write your abstract last, right before the proofreading stage, because it’s a summary of the work you’ve already done. Your abstract should:

- Be a self-contained text, not an excerpt from your paper

- Be fully understandable on its own

- Reflect the structure of your larger work

Start by clearly defining the purpose of your research. What practical or theoretical problem does the research respond to, or what research question did you aim to answer?

You can include some brief context on the social or academic relevance of your dissertation topic , but don’t go into detailed background information. If your abstract uses specialized terms that would be unfamiliar to the average academic reader or that have various different meanings, give a concise definition.

After identifying the problem, state the objective of your research. Use verbs like “investigate,” “test,” “analyze,” or “evaluate” to describe exactly what you set out to do.

This part of the abstract can be written in the present or past simple tense but should never refer to the future, as the research is already complete.

- This study will investigate the relationship between coffee consumption and productivity.

- This study investigates the relationship between coffee consumption and productivity.

Next, indicate the research methods that you used to answer your question. This part should be a straightforward description of what you did in one or two sentences. It is usually written in the past simple tense, as it refers to completed actions.

- Structured interviews will be conducted with 25 participants.

- Structured interviews were conducted with 25 participants.

Don’t evaluate validity or obstacles here — the goal is not to give an account of the methodology’s strengths and weaknesses, but to give the reader a quick insight into the overall approach and procedures you used.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Next, summarize the main research results . This part of the abstract can be in the present or past simple tense.

- Our analysis has shown a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

- Our analysis shows a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

- Our analysis showed a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

Depending on how long and complex your research is, you may not be able to include all results here. Try to highlight only the most important findings that will allow the reader to understand your conclusions.

Finally, you should discuss the main conclusions of your research : what is your answer to the problem or question? The reader should finish with a clear understanding of the central point that your research has proved or argued. Conclusions are usually written in the present simple tense.

- We concluded that coffee consumption increases productivity.

- We conclude that coffee consumption increases productivity.

If there are important limitations to your research (for example, related to your sample size or methods), you should mention them briefly in the abstract. This allows the reader to accurately assess the credibility and generalizability of your research.

If your aim was to solve a practical problem, your discussion might include recommendations for implementation. If relevant, you can briefly make suggestions for further research.

If your paper will be published, you might have to add a list of keywords at the end of the abstract. These keywords should reference the most important elements of the research to help potential readers find your paper during their own literature searches.

Be aware that some publication manuals, such as APA Style , have specific formatting requirements for these keywords.

It can be a real challenge to condense your whole work into just a couple of hundred words, but the abstract will be the first (and sometimes only) part that people read, so it’s important to get it right. These strategies can help you get started.

Read other abstracts

The best way to learn the conventions of writing an abstract in your discipline is to read other people’s. You probably already read lots of journal article abstracts while conducting your literature review —try using them as a framework for structure and style.

You can also find lots of dissertation abstract examples in thesis and dissertation databases .

Reverse outline

Not all abstracts will contain precisely the same elements. For longer works, you can write your abstract through a process of reverse outlining.

For each chapter or section, list keywords and draft one to two sentences that summarize the central point or argument. This will give you a framework of your abstract’s structure. Next, revise the sentences to make connections and show how the argument develops.

Write clearly and concisely

A good abstract is short but impactful, so make sure every word counts. Each sentence should clearly communicate one main point.

To keep your abstract or summary short and clear:

- Avoid passive sentences: Passive constructions are often unnecessarily long. You can easily make them shorter and clearer by using the active voice.

- Avoid long sentences: Substitute longer expressions for concise expressions or single words (e.g., “In order to” for “To”).

- Avoid obscure jargon: The abstract should be understandable to readers who are not familiar with your topic.

- Avoid repetition and filler words: Replace nouns with pronouns when possible and eliminate unnecessary words.

- Avoid detailed descriptions: An abstract is not expected to provide detailed definitions, background information, or discussions of other scholars’ work. Instead, include this information in the body of your thesis or paper.

If you’re struggling to edit down to the required length, you can get help from expert editors with Scribbr’s professional proofreading services or use the paraphrasing tool .

Check your formatting

If you are writing a thesis or dissertation or submitting to a journal, there are often specific formatting requirements for the abstract—make sure to check the guidelines and format your work correctly. For APA research papers you can follow the APA abstract format .

Checklist: Abstract

The word count is within the required length, or a maximum of one page.

The abstract appears after the title page and acknowledgements and before the table of contents .

I have clearly stated my research problem and objectives.

I have briefly described my methodology .

I have summarized the most important results .

I have stated my main conclusions .

I have mentioned any important limitations and recommendations.

The abstract can be understood by someone without prior knowledge of the topic.

You've written a great abstract! Use the other checklists to continue improving your thesis or dissertation.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Anchoring bias

- Halo effect

- The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- The placebo effect

- Nonresponse bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

An abstract is a concise summary of an academic text (such as a journal article or dissertation ). It serves two main purposes:

- To help potential readers determine the relevance of your paper for their own research.

- To communicate your key findings to those who don’t have time to read the whole paper.

Abstracts are often indexed along with keywords on academic databases, so they make your work more easily findable. Since the abstract is the first thing any reader sees, it’s important that it clearly and accurately summarizes the contents of your paper.

An abstract for a thesis or dissertation is usually around 200–300 words. There’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check your university’s requirements.

The abstract is the very last thing you write. You should only write it after your research is complete, so that you can accurately summarize the entirety of your thesis , dissertation or research paper .

Avoid citing sources in your abstract . There are two reasons for this:

- The abstract should focus on your original research, not on the work of others.

- The abstract should be self-contained and fully understandable without reference to other sources.

There are some circumstances where you might need to mention other sources in an abstract: for example, if your research responds directly to another study or focuses on the work of a single theorist. In general, though, don’t include citations unless absolutely necessary.

The abstract appears on its own page in the thesis or dissertation , after the title page and acknowledgements but before the table of contents .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, July 18). How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 8, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/abstract/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis or dissertation introduction, shorten your abstract or summary, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Writing for & Publishing in Law Reviews

- General: Texts & Advice

- Follow New Developments

- Mine Others' Ideas

- Shape Your Topic

- Search for Published Articles

- Search for Books & Book Chapters

- Search for Working Papers, Upcoming Symposia

- Using AI Tools

- Type of Journal

- Measuring Quality

Submission Guides

Law review mailing addresses, electronic submission, writing an abstract, how to format the paper, when to submit, simultaneous submission & expedited review, responding to calls for papers, article selection process, publication agreements.

- Guide Authors

Two authors maintain a journal-by-journal guide to law review submission policies and post it on SSRN : Allen K. Rostron & Nancy Levit, Information for Submitting Articles to Law Reviews & Journals . Note: covers each U.S. law school's general law review; does not cover specialized journals.

Another useful article for students (by Levit et al.), is Submission of Law Student Articles for Publication (updated Aug. 30, 2016). Chart indicates which law reviews do and do not accept submissions from students at other schools. Again, covers general law reviews, not specialized journals.

Colin Miller annually updates and posts his Submission Guide for Online Law Review Supplements (the version from July 22, 2013, covers 49 general law review online supplements).

- Washington & Lee, Law Journals: Submissions & Ranking Links to journals' submission policies; provides email addresses.

- Scholastica Founded by a group of Chicago graduate students in March 2012, Scholastica now includes over 700 law reviews and journals.

Your abstract will be the first thing most editors see when they review your paper. Remember that the editors have not been thinking about your topic as much as you have—in fact, as third-year law students, they might know nothing about your topic. Your abstract is your first chance to explain why your topic is interesting and important and how your paper makes a contribution to the field. Make sure that it is well-crafted and clear. Proofread it carefully: there's no need to turn off editors before they even start skimming the article!

Later, the abstract will help researchers find your article and entice them to read it—more good reasons to put some effort into it!

Eugene Volokh, Writing an Abstract for a Law Review Article , Volokh Conspiracy, Feb. 8, 2010.

Mary A. Dudziak (USC law): How (Not to) Write an Abstract , Legal History Blog, Oct. 23, 2007.

Patrick Dunleavy, Writing Informative Abstracts for Journal Articles , Writing for Research, Feb. 16, 2014.

Optimizing Your Article for Search Engines , Wiley-Blackwell Author Services. Includes examples of abstracts that do better and worse jobs helping users find a paper using a search engine like Google. Also from Wiley: Search Engine Optimization (SEO) for your article .

Colorado State University's Writing Center has a very thorough online tutorial . It is not focused on law, but its techniques can be used in any field.

Advice for computer science papers (adaptable to law with a little thought): Philip Koopman, How to Write an Abstract (1997).

First, read the journal's submission guidelines or instructions for authors. The editors often specify whether they want single- or double-spaced, Word or PDF, footnotes or endnotes, and so on. (Footnotes are standard in U.S. law journals, but some cross-disciplinary journals use a format common in social sciences.)

Some editors might look past odd formatting, typographical errors, and sloppy citations to see the brilliance of a paper. But why make them? Faced with two papers that are comparable in content, most editors will choose the one that will be easier to edit. Take the time and care to make your paper look good.

See the Gallagher guide Bluebook 101 .

The Academic Legal Writing website includes a Word template .

Peak submission times for student journals are February-March (as new editorial boards are looking toward the next volume) and August (as student editors are returning from their summer jobs). Authors who submit after these peaks may still place their papers, but it might be harder because some journals will have already filled their issues.

- Scholastica Law Review Submission Insights Includes data and information about the submission cycles.

It is common for authors to submit papers to many law journals at once. When one journal makes an offer to publish, the author may ask more desirable journals to expedite review, hoping to "trade up."

For example, suppose an author submits to 26 journals, A through Z, with A being the most attractive (most prestigious) and the rest falling along a spectrum of desirability. Journal M makes an offer and gives the author two weeks to decide. The author contacts journals A-L, tells them about the deadline, and asks the editors to make a decision quickly (i.e., to "expedite review"). Journal G makes an offer. The author contacts Journals A-F. None of them make an offer, so the author publishes with Journal G.

Some people don’t like this practice, because it takes advantage of the work of the student editors of lower-ranked journals. In this example, the editors of journal M put in the work to decide that the article was worth publishing, and the author just used that work to get more attention from other journals. These critics suggest that authors should submit to their preferred journals—those where they would published if offered the chance. If they don’t get offers, then they can submit to their next preferred journals. See Joseph Scott Miller, Essay, The Immorality of Requesting Expedited Review , 21 Lewis & Clark L. Rev. 211 (2017), HeinOnline .

Some journals have specific policies about expedited review. For example here is the Harvard Journal of Law & Technology 's policy:

We will conduct expedited reviews for articles with publication offers from other journals. So that we are able to appropriately respond to such requests, authors submitting an expedited review request should specify: (1) their need for consideration on an expedited basis, and (2) the offer deadline from the other journal(s). As with standard submissions, we have a strong preference for expedite requests submitted via Scholastica . If you email us regarding an expedite, please include "expedite" in the subject line of the email.

Some peer-reviewed journals do not participate in this process. Be sure to read the submission guidelines for the journals you are interested in. For example, The Journal of Law and Economics states:

Papers submitted to the Journal of Law and Economics must not have been published and must not be under consideration elsewhere.

The Journal of Empirical Legal Studies states:

Simultaneous submission policy: Simultaneous submission of papers to JELS and other journals is permitted. JELS , however, requires that if a submission is accepted for publication in JELS before acceptance by another journal, the author commits to publishing the article in JELS . Thus, if JELS accepts an article before other journals have acted, the author must publish in JELS . If an author receives an acceptance before JELS has acted, the author is free to withdraw the submission from JELS , or to request an expedited review from JELS . Please contact JELS for details.

A call for papers is an announcement by editors of a journal or organizers of a conference that they are seeking papers on a given theme. Some calls for papers ask authors to send an abstract or proposal; others seek finished papers. When you respond to a call for papers, be sure to read carefully all of the instructions (deadlines, word count, citation style, etc.).

The Legal Scholarship Blog lists conferences, symposiums, and calls for papers. You can search by topic, you can use the calendar to find upcoming paper deadlines, or you can simply browse the listings. Posts usually link to the journals' or conferences' websites for more information.

Many student writing competitions lead to publication. See links.

Leah M. Christensen & Julie A. Oseid, Navigating the Law Review Article Selection Process: An Empirical Study of Those with all the Power—Student Editors , 59 S. C. L. Rev. 175 (2007). HeinOnline

Jason P. Nance & Dylan J. Steinberg, The Law Review Article Selection Process: Results from a National Study , 71 Alb. L. Rev. 565 (2008). HeinOnline

As an author, consider whether you will still have the right to use your article in future works, to distribute it to your students, and to post it on the web (for instance, on SSRN ). You can negotiate with the journal if you don't agree with all the provisions in the journal's form contract.

See Benjamin J. Keele, Advising Faculty on Law Journal Publication Agreements (2012), for a discussion of the issues to consider.

A good starting point is the model publication agreement (1998) from the Association of American Law Schools . See also Model Copyright Agreements from Copyright Experiences Wiki . The Copyright Experiences Wiki also has information about individual law journals' policies.

- << Previous: Measuring Quality

- Next: Selected Works About Law Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Apr 8, 2024 5:40 PM

- URL: https://lib.law.uw.edu/writinglawreview

Writing an Abstract for a Law Review Article

Here’s a draft of the new section on Writing an Abstract, to be published in the fourth edition of my Academic Legal Writing book. There’s still plenty of time to improve it, so I’d love to get feedback. (By the way, the abstracts I give as examples are my own, but I’d prefer to use someone else’s abstracts, especially if they are very effective. So if you have any recommendations for very good abstracts, please pass them along.)

An abstract is a short summary — one to three paragraphs — of an article. Some journals include an abstract at the start of the article, or put all the abstracts from an issue on the issue’s table of contents, or put the abstracts on the journal’s Web site. These journals will either require you to write the abstract, or will offer to write it for you. Reject their offer, and write the abstract yourself: It’s your article, and you’ll know better how to summarize it effectively.

But even if the journal doesn’t publish an abstract, you should write one anyway. Services such as the Social Science Research Network (see p. 265) maintain e-mail distribution lists through which hundreds or thousands subscribers get abstracts of forthcoming articles. These distribution lists are invaluable tools for you to get readers for your work.

Whether in a law review or on a distribution list, the abstract is an advertisement for your article. True, you don’t want money from your “customers” (the audience) — you want their time and attention. But their attention is scarce, and lots of authors are competing for it. You want readers to “buy” your article in one of two ways:

- by reading the article (or at least the Introduction) right away, or

- by remembering it (even if just vaguely) for the future, so that when the underlying issue becomes important to them, they can find and read the article then.

And the audience for your advertisement is quite demanding. They’ve generally found the abstract just through a quick skim of an SSRN e-mail or a law review table of contents. (People who find the article through a citation or a Westlaw or Lexis search are probably more likely to skim the Introduction, which is immediately available to them, rather than starting with the abstract.) Readers of your abstract therefore aren’t at all sure the article will be of any value to them.

You need to quickly show them this value. You need to clearly and tersely tell the reader (1) what problem the article is trying to solve, and (2) what valuable original observations the article offers. Naturally, the abstract can’t go into much detail. But it has to at least give the reader a general idea of what the article contributes.

Here, for instance, is an adequate abstract, adequate because it quickly captures the essence of the value added by the article:

People often argue that symbolic expression — especially flag burning — isn’t really “speech” or “press,” and that the Court’s decisions protecting symbolic expression are thus illegitimate. But it turns out that the original meaning of the First Amendment likely includes symbolic expression. Speech restrictions of the Framing era routinely treated symbolic expression the same as literal “speech” and “press.” Constitutional speech protections of that era did so as well, though the evidence on this is slimmer. And the drafting history of the phrase “the freedom of speech, or of the press,” coupled with the views of leading commentators from the early 1800s, suggests that the First Amendment’s text was understood as protecting “publishing,” a term that at the time covered communication of symbolic expression and not just printing. Though the Court has never relied on this evidence, even originalists ought to accept the Court’s bottom line conclusion that the First Amendment covers symbolic expression.

The first sentence does three things. First, it notes the general topic of the article — the First Amendment and symbolic expression generally. Second, the sentence identifies the specific focus of the article, which is whether the text of the First Amendment must be read as protecting only “speech” and “press” and not symbolic expression. Third, the sentence very quickly provides a concrete illustration (flag burning) for the abstraction (symbolic expression).

The second sentence explains the article’s claim: The original meaning of the First Amendment likely covers symbolic expression. Readers who stop reading there will at least remember something like “There’s an article that says that even originalists should approve of the Court’s flagburning decisions.”

That would be an oversimplification of the article’s claim, but that’s fine — any one-sentence summary that lingers in people’s minds will inevitably be an oversimplification. The important thing is that if the issue comes up for readers in the future, they might well search for the article, find it, read it, and use it. And, if the author is lucky, maybe some readers will be interested enough to actually read the article right away, or at least move from reading the abstract to reading the Introduction.

The next three sentences quickly summarize the main arguments that the article uses to support its claim. These arguments — here, historical assertions, though for another article they might be normative arguments or empirical findings — are part of the contribution that the article offers. Again, the summary is an oversimplification, and as a result may not be entirely clear to all readers. But it should at least give the reader a glimpse of the observations that the article makes.

Finally, the last sentence ties the argument to the caselaw: The sentence explains that this is an article that offers historical support for the Court’s precedents, rather than arguing against the Court’s precedents.

Many authors try to fit an abstract into one paragraph, and some journals seem to prefer that. I advise against this, unless the abstract is very short. Shorter paragraphs tend to be more readable, and longer paragraphs tend to be alienating to many readers. And the reader of the abstract will likely be the sort of reader who is especially unmotivated to read further. The more you can do to make the abstract appealing, within the space constraints you’re given, the better.

Likewise, I like including numbering, for instance in this abstract:

How should state and federal constitutional rights to keep and bear arms be turned into workable constitutional doctrine? I argue that unitary tests such as “strict scrutiny,” “intermediate scrutiny,” “undue burden,” and the like don’t make sense here, just as they don’t fully describe the rules applied to most other constitutional rights. Rather, courts should separately consider four different categories of justifications for restricting rights: (1) Scope justifications, which derive from constitutional text, original meaning, tradition, or background principles; (2) burden justifications, which rest on the claim that a particular law doesn’t impose a substantial burden on the right, and thus doesn’t unconstitutionally infringe it; (3) danger reduction justifications, which rest on the claim that some particular exercise of the right is so unusually dangerous that it might justify restricting the right; and (4) government as proprietor justifications, which rest on the government’s special role as property owner, employer, or subsidizer. I suggest where the constitutional thresholds for determining the adequacy of these justifications might be set, and I use this framework to analyze a wide range of restrictions: “what” restrictions (such as bans on machine guns, so-called “assault weapons,” or unpersonalized handguns), “who” restrictions (such as bans on possession by felons, misdemeanants, noncitizens, or 18-to-20-year-olds), “where” restrictions (such as bans on carrying in public, in places that serve alcohol, or in parks, or bans on possessing in public housing projects), “how” restrictions (such as storage regulations), “when” restrictions (such as waiting periods), “who knows” regulations (such as licensing or registration requirements), and taxes and other expenses.

Though it’s unusual to number individual clauses in normal prose, here the numbering quickly shows the hurried reader how the sentence is structured, and what the four elements of the proposed framework are. It might have even been helpful to do something similar in the last paragraph. But on the other hand too much numbering might have annoyed readers — a bit of departure from standard prose style is fine, but too much would make the abstract look odd. And the quotation marks surrounding the key items in the last paragraph probably provide some internal delimiters that can serve as alternatives to numbering.

Researching and Writing a Law Review Note or Seminar Paper: Writing

- Outline & Guide Information

- Research Tips

- Resources You Can Use for Topic Selection

- Advice for Preemption & Research

- Secondary & Primary Sources for Preemption & Research

- Citation Management Tools

- Law Library Logistics

- Citation Manuals

- Hard-to-Find and Hard-to-Cite-Sources

- Bluebook Guides

- Advice: Choosing Journals, Submission Process, Evaluating Offers, Retaining Author Rights

- Choosing Journals Resources

- Submission Services & Information for NYU Students

- Legal Writing Competitions

Books in Law Library

- Scholarly Writing: Ideas, Examples, and Execution, NYU Law Library

- Scholarly Writing for Law Students - Seminar Papers, Law Review Notes and Law Review Competition Papers, NYU Law Library

- Academic Legal Writing: Law Review Articles, Student Notes, Seminar Papers, and Getting on Law Review, NYU Law Library

- Effective Lawyering: A Checklist Approach to Legal Writing and Oral Argument See 'Chapter 7. Academic Writing Checklist'

Articles & Book Chapters

- Article Writing for Attorneys, 17 Conn. Law. 30 (2007)

- How (Not to) Write an Abstract, Legal History Blog

- How to Write a Good Abstract for a Law Review Article, Faculty Lounge

- How To Write a Law Review Article, 20 U. San Francisco L. Rev. 445 (1986)

- In Search of the Read Footnote: Techniques for Writing Legal Scholarship and Having It Published, 6 Legal Writing: J. Legal Writing Inst. 229 (2000)

- Law Students as Legal Scholars: An Essay/Review of Scholarly Writing for Law Students and Academic Legal Writing, 7 N.Y. City L. Rev. 195 (2004) A review of the the two leading books on scholarly legal writing.

- Legal Research & Writing for Scholarly Publication, AALL Website

- The Redbook: A Manual on Legal Style, NYU Law Library See 'Part 4: Scholarly Writing'

- The Three-Act Argument: How to Write a Law Article That Reads Like a Good Story (May 28, 2015). 64 J. Legal Educ. 707 (2015)

- Tips for Better Writing in Law Reviews (and Other Journals), Mich. B.J.,Oct. 2012, at 46

- Write on! A Guide to Getting on Law Review, SSRN

- Writiing Process: Student Writing, NYU Law Website

- Writing an Abstract for a Law Review Article, The Volokh Conspiracy Website

- Writing a Student Article, 48 J. Legal Ed. 247 (1998)

- How to Love Writing About Tax Without Falling in Love With Your Own Tax Writing, Tax Notes

NYU Law Advice: Click on the Text to Read in Full

- << Previous: Law Library Logistics

- Next: Citation >>

- Last Updated: Jan 16, 2024 5:03 PM

- URL: https://nyulaw.libguides.com/lawreviewarticle

Scholarly Publishing Resources

- Introduction

- Where to Submit

- Formatting Your Submission

- How to Submit

- When to Submit

- Author's Agreements

- Tracking and Expediting Submissions

- Non-Law Journal Submission

- Book Proposals

Cover Letters

- Sample Law Review Cover Letters In this blog post from Concurring Opinions , Lawrence Cunningham provides multiple examples of cover letters to accompany law review submissions.

- Pimps, Prostitutes, and Placements: Drafting the Cover Letter to Law Journals

- Writing an Abstract for a Law Review Article

- Lee Petherbridge & Christopher Anthony Cotropia, Should Your Law Review Article Have an Abstract and Table of Contents? The authors studied the impact of articles in top 100 law reviews and found that the presence of abstracts and tables of contents correlated with increased impact.

- Writing an Effective Abstract: An Audience-Based Approach The authors, editors at two non-law journals, discuss the elements of an effective abstract and provide examples of effective and ineffective abstracts.

Submission Template

- Eugene Volokh's Law Review Template

- << Previous: Where to Submit

- Next: How to Submit >>

- Last Updated: Sep 7, 2021 2:43 PM

- URL: https://libguides.law.gsu.edu/scholarlypublishing

Editorial Manager, our manuscript submissions site will be unavailable between 12pm April 5, 2024 and 12pm April 8 2024 (Pacific Standard Time). We apologize for any inconvenience this may cause.

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write an Abstract

Expedite peer review, increase search-ability, and set the tone for your study

The abstract is your chance to let your readers know what they can expect from your article. Learn how to write a clear, and concise abstract that will keep your audience reading.

How your abstract impacts editorial evaluation and future readership

After the title , the abstract is the second-most-read part of your article. A good abstract can help to expedite peer review and, if your article is accepted for publication, it’s an important tool for readers to find and evaluate your work. Editors use your abstract when they first assess your article. Prospective reviewers see it when they decide whether to accept an invitation to review. Once published, the abstract gets indexed in PubMed and Google Scholar , as well as library systems and other popular databases. Like the title, your abstract influences keyword search results. Readers will use it to decide whether to read the rest of your article. Other researchers will use it to evaluate your work for inclusion in systematic reviews and meta-analysis. It should be a concise standalone piece that accurately represents your research.

What to include in an abstract

The main challenge you’ll face when writing your abstract is keeping it concise AND fitting in all the information you need. Depending on your subject area the journal may require a structured abstract following specific headings. A structured abstract helps your readers understand your study more easily. If your journal doesn’t require a structured abstract it’s still a good idea to follow a similar format, just present the abstract as one paragraph without headings.

Background or Introduction – What is currently known? Start with a brief, 2 or 3 sentence, introduction to the research area.

Objectives or Aims – What is the study and why did you do it? Clearly state the research question you’re trying to answer.

Methods – What did you do? Explain what you did and how you did it. Include important information about your methods, but avoid the low-level specifics. Some disciplines have specific requirements for abstract methods.

- CONSORT for randomized trials.

- STROBE for observational studies

- PRISMA for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Results – What did you find? Briefly give the key findings of your study. Include key numeric data (including confidence intervals or p values), where possible.

Conclusions – What did you conclude? Tell the reader why your findings matter, and what this could mean for the ‘bigger picture’ of this area of research.

Writing tips

The main challenge you may find when writing your abstract is keeping it concise AND convering all the information you need to.

- Keep it concise and to the point. Most journals have a maximum word count, so check guidelines before you write the abstract to save time editing it later.

- Write for your audience. Are they specialists in your specific field? Are they cross-disciplinary? Are they non-specialists? If you’re writing for a general audience, or your research could be of interest to the public keep your language as straightforward as possible. If you’re writing in English, do remember that not all of your readers will necessarily be native English speakers.

- Focus on key results, conclusions and take home messages.

- Write your paper first, then create the abstract as a summary.

- Check the journal requirements before you write your abstract, eg. required subheadings.

- Include keywords or phrases to help readers search for your work in indexing databases like PubMed or Google Scholar.

- Double and triple check your abstract for spelling and grammar errors. These kind of errors can give potential reviewers the impression that your research isn’t sound, and can make it easier to find reviewers who accept the invitation to review your manuscript. Your abstract should be a taste of what is to come in the rest of your article.

Don’t

- Sensationalize your research.

- Speculate about where this research might lead in the future.

- Use abbreviations or acronyms (unless absolutely necessary or unless they’re widely known, eg. DNA).

- Repeat yourself unnecessarily, eg. “Methods: We used X technique. Results: Using X technique, we found…”

- Contradict anything in the rest of your manuscript.

- Include content that isn’t also covered in the main manuscript.

- Include citations or references.

Tip: How to edit your work

Editing is challenging, especially if you are acting as both a writer and an editor. Read our guidelines for advice on how to refine your work, including useful tips for setting your intentions, re-review, and consultation with colleagues.

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

LAW COLLOQUY

You Must Know Yourself, To Grow Yourself

How To Write an Abstract | Abstract for Research Paper & Conference & Presentation

How To Write an Abstract | Abstract for Research Paper

WHAT IS AN ABSTRACT?

* An abstract is the gist or essence of your paper or article, which reflects your idea of research,

* It provides detailed information, analysis, and arguments of your complete research concisely and concretely,

* It also helps readers to remember key points from your research.

WHEN TO WRITE AN ABSTRACT?

* Even though it is the first section of your paper, the abstract should be written at the end because it summarizes the contents of your entire research.

* You must take important sentences or key points from each section of the research and arrange them in a sequence that sums up the idea of the work.

* Then write the helping or connecting points or words to make the flow clear, smooth and comprehensive.

* Before submitting your final research/manuscript, cross-check whether the information in the abstract entirely agrees with what you have written in the research.

* Lastly, always remember your abstract should justify your topic correctly.

* An abstract is usually between 150-500 words; that is why it should be written in a very precisely but concretely.

WHAT SHOULD BE INCLUDED IN AN ABSTRACT?

* The main topic/heading of your submission is the essential thing which should reflect in your abstract.

* The background information or the context of your research must be covered.

* The objective(s) of your study and research problem(s) is the next important category.

* Research methodology must be mentioned.

* It must include your findings, key results or arguments.

* Lastly, the significance/implication of your research and conclusion

WHAT SHOULD NOT BE INCLUDED IN AN ABSTRACT?

* It should not contain lengthy background and repetitive information.

* It should avoid unnecessary adverbs, adjectives and redundant phrases.

* There must not be any use of acronyms or abbreviations, ellipticals (i.e., ending with "...") or incomplete sentences.

* The abstract should reflect your research that is why references to other literature must be avoided.

* Never use jargon or terms that may confuse the reader.

* Do not give citations, footnotes and reference in the abstract.

* Should not use any image, illustration, figure, or table, or references to them.

Also See - Top Thirty Supreme Court Judgement of India in 2020-2021

Do Share if you find useful on how to write an abstract for research Paper

- How To Write An Abstract

- Abstract For Research Paper

- How To Write An Abstract For A Project

- How To Write An Abstract For A Conference

- How To Write An Abstract For A Presentation

- ##gender #pay Gap

- #Womenempowerment

- #Womenrights

- ##law #solicitor #lawadvocate

- #Advocateonrecord

- #Attorneygeneralinindia

- #Attorneygeneralinengland

- #Attorneygeneralinus

- #Solicitorsolicitorgeneral

- #Abortioninindia

- #Human Rights

- #International Law

- #Differences

- #Amicuscuriae

- #Supremecourt

- #Arbitration

- #Conciliation

- #Consumerprotection

- #Lawcolloquy

- #Legalprocedure

- #Career In Law

- # Law School

- # Legal News

- # Law Colloquy

- # Legal Updates

- #Childrights

- # Governance

- # Governmentality

- # Historicity

- # Enactment

- # Normatively

- # Conversion

- # Legal Blog

- # Law Students

- #Commonintention

- #Commonobject

- #Section149

- #Constitution

- # Indian Constitution

- # Constitutional Law

- # Article 19(1)

- #Legalsystem

- #Coronavirus

- #Criminology

- #Punishment

- #Theoriesofpunishment

- #Indianpenalcode

- #Expiatorytheory

- #Reformativetheory

- #Preventivetheory

- #Retributivetheory

- #Deterrenttheory

- #Custody#lawcolloquy

- #Criminallaw

- #Dihonestly

- #Fraudulently

- #Indianpnalcode

- #Exceptionsinipc

- #Privatedefence

- #Triflingact

- #Criminalintend

- #Volentinonfiitinjuria

- #Actdonebyconsent

- #Justifiedact

- #Excusableact

- #Actofanintoxicatedperson

- #Actofaninsaneperson

- #Doliincapax

- #Mistakeoffact

- #Burdenofproof

- # Female Genital Mutilation

- # Hervoicematters

- # Zero Tolerance

- # First Information Report

- # Code Of Criminal Procedure

- # Investigation

- #Fundamental Rights

- # Human Rights

- # Difference

- # Constitution

- # Similarities

- #Manusmriti

- #Legislation

- #How To Write An Abstract

- # Abstract For Research Paper

- # How To Write An Abstract For A Project

- # How To Write An Abstract For A Conference

- # How To Write An Abstract For A Presentation

- # International Humanitarian Law

- # Geneva Convention

- # Armed Conflict

- # United Nations

- # Un Charter

- #Intraterritorial

- #Extraterritorial

- #Investigation

- #Jurisprudence

- # Categories Of Law

- # Sources Of Law

- # Constitutionalism.

- #Kerala Development Model

- #Higher Literacy Rate

- #Kidnapping

- #Wrongfullyconceals

- #Importationofgirl

- #Procuration

- #Law Colloquy

- # Marriage Certificate

- # Court Marriage

- # Hindu Marriage Act

- # Special Marriage Act

- # No Confidence Motion

- # Parliament

- # Constitution Of India

- # Structure Of Parliament

- #Law Of Crime

- # General Exceptions

- # Sections Of Code

- #Good Faith

- # Mental Element

- # Cyber Crime

- # International Law

- # Law Career

- # Pranshu Yadav

- # Cyber Bulling

- # Awareness

- # Women Impresario

- # Amendment

- # Criminal Law

- # Proposed Bill Criminal Law

- # Election Process

- # Election In India

- # Suo Moto Cognizance

- # Manipur Violence

- # Supreme Court

- # Women Empowerment

- # Amendmen For Female

- # Women Supporting Women

- # Supreme Court Of India

- # New Legal Terminology For Women In The Court

- #Formal Sources Of Law

- # Informal Sources Of Law

- # Legislation

- # Precedent

- #Awcolloquy

- #Lawstudents

- #Registration

- #Artificial Intelligence

- #Intellectual Property

- #Healthcare

- #Educationpolicy

- #Lawstudent

- #Womenabuse

- #Unitednation

- #Hinduschooloflaw

- #Schooloflaw

- #Succesionact

- #Succestion

- #Daughtersright

- #Propertyrights

- #Biologicalage

- #Mentalillness

- #Criminaljusticesystem

- #Parliament

- #Parliamentaryssystem

- #Government

- #Selfreliantindia

- #Aatmnirbharbharat

- #Onlinearbitration

- #Insolvency

- #Bankruptcycode

- #Interimrelief

- #Emergencyarbitration

- #Internationalarbitration

- #Convertiontheory

- #Homosexuality

- #Consumerprotectionact

- #Pecuniaryjurisdiction

- #Constitutionallaw

- #Probationofoffender

- #Guiltymind

- #Rapevictim

- #Reservation

- #Stockexchange

- #Investment

- #Transgender

- #Genderbias

- #Gendersensitivity

- #Genderissue

- #Legal Entity

- # Legal Entity Identifier

- # What Is Legal Entity

- # Legal Entity Meaning

- #Legal Method

- # Dissenting Opinions

- # Distinguishing Opinions

- # Concurring Opinions

- #Legal News

- # Legal Headlines

- # High Court

- # Judiciary

- # Decisions

- # Judgements

- # Headlines

- # Same Sex Marriage

- #Mental Illness

- # Mental Health

- # Psychopaths

- # Schizophrenia

- #Misuse Of Laws

- # Gender Oriented Laws

- # Sexual Harassment

- # Dowry Harassment

- # Eve-teasing

- # Loopholes

- # Indian Legal System

- #Moblynching

- # Censor Board Of India

- # Certificate

- #High Court

- #Supreme Court

- #Organisedcrime

- #Racketeering

- #Syndicatecrime

- #Whitecollarcrime

- #Pedagogy Model

- # Ukraine Lawyer

- # Anatoliy Kosturb

- # Pedagogy Model Of Lawyer

- # Ukraine Law Professor

- #Police Commissioner Sysytem

- # Collector

- #Presumption

- #Evidenceact

- #Maypresume

- #Shallpresume

- #Conclusiveproof

- #Presumptionoffact

- #Presumptionoflaw

- #Mixedpresumption

- #Public Interest Litigation

- # Legal Education

- # Frivolous Pil

- #Reformatory

- #Rehabilitation

- #Research Papers

- # How To Write Legal Research Paper

- # Research Requirements

- #Right To Information

- # Transparency

- # E-government

- # Accountability

- #Right To Know

- # Right To Information

- # Public Disclosure

- # Judicial Independence

- #Sc Verdict

- # Supreme Court Today Judgement

- # Judgement Order

- # Supreme Court Of India Judgements

- #Socieconomicoffences

- # Lawcolloquy

- #Publichealth

- #Criminaljustice

- #Coronavirusindia

- #Covid19lockdown

- #Criminalprocdurecode

- #Dissertation

- #Lawoftorts

- #Breachofcontract

- #Breachoftrust

- #Briefoftorts

- #Meaningoftorts

- #Wrongfulrestraint

- #Wrongfulconfinement

- #Distinction

Not a member? Sign Up

Forgot Password?

Already have an account? Log In

- Forgot Password

Login/Signup?

- Member Login

Become Member

- Directories

Writing an abstract

Although it is usually brief (typically 150-300 words), an abstract is an important part of journal article writing (as well as for your thesis and for conferences). Done well, the abstract should create enough reader interest that readers will want to read more!

Whereas the purpose of an introduction is to broadly introduce your topic and your key message, the purpose of an abstract is to give an overview of your entire project, in particular its findings and contribution to the field. An abstract should be a standalone summary of your paper, which readers can use to decide whether it's relevant to them before they dive in to read the paper.

Usually an abstract includes the following.

- A brief introduction to the topic that you're investigating.

- Explanation of why the topic is important in your field/s.

- Statement about what the gap is in the research.

- Your research question/s / aim/s.

- An indication of your research methods and approach.

- Your key message.

- A summary of your key findings.

- An explanation of why your findings and key message contribute to the field/s.

In other words, an abstract includes points covering these questions.

- What is your paper about?

- Why is it important?

- How did you do it?

- What did you find?

- Why are your findings important?

To see the specific conventions in your field/s, have a look at the structure of a variety of abstracts from relevant journal articles. Do they include the same kinds of information as listed above? What structure do they follow? You can model your own abstract on these conventions.

Dealing with feedback >>

Journal article writing

Targeting a journal

Turning a chapter into an article

Planning your paper

Dealing with feedback

- ANU Library Academic Skills

- +61 2 6125 2972

- OU Homepage

- OU Social Media

- The University of Oklahoma

Publication Opportunities for Law Students

This libguide aims to be a helpful tool for those whose articles may not have been selected by their home journal or who have written papers for their graduation writing requirement or other courses and wish to see them published. Within this page, students will find articles and guidance focused on the considerations involved in submitting their scholarly work for publication. From strategies to effectively target law reviews open to student-authored pieces, to exploring the potential of specialty journals and writing competitions, this guide seeks to demystify the submission process. Additionally, it offers links to useful databases designed to aid in determining the most fitting venues for their articles.

- Levit, Nancy and MacLachlan, Lawrence Duncan and Rostron, Allen K. and Greaves, Drew, Submission of Law Student Articles for Publication (August 30, 2016). This article provides a concise overview of issues law students should consider when pursuing publication outside of a law review at the law school where they are enrolled. The article includes a table in Appendix A that is regularly updated noting the policies of 194 law reviews, including whether the law review allows external student authors to publish.

- Crawford, Bridget J., Information for Submitting to Online Law Review Companions (August 14, 2023). This regularly updated working paper provides a table of the online companions of main law reviews at the top 60 schools, including information about limitations and submission requirements.

- Eugene Volokh, Writing an Abstract for a Law Review Article, Volokh Conspiracy (Feb. 10, 2010 6:21 PM). This blog entry, by the author of Academic Legal Writing, offers a concise overview of how to effectively draft an abstract for your law review article, which may be required by law reviews.

- Brian Galle, The Law Review Submission Process: A Guide for (and by) the Perplexed, SSRN (Aug. 12, 2016) This tongue-in-cheek article provides a Q&A style of various considerations regarding the publication process including the ideal time to submit a piece for consideration and related issues.

Scholastica

- Scholastica Scholastica is a platform through which authors can submit there articles for publication to hundreds of law reviews. The manuscript submission portal also provides access to relevant law review guidelines. Creation of an account is free, but article submissions are $6.60 per submission. In an effort to support law student scholarship, the OU Law Library has adopted the following policy: “Law students may submit law journal articles to Scholastica under and funded by the College of Law’s institutional account under these conditions: o The article must have been written as part of (1) a course requirement, (2) the graduation writing requirement, or (3) as a requirement of law journal service during a student’s enrollment at the College of Law. o The article must be reviewed by a faculty member who is either the (1) professor of record for a course requirement, (2) the advisor or supervisor of a graduation writing requirement, or (3) an expert in the relevant field of law. The faculty member must approve the submission of the article for publication and submission to Scholastica. Students who meet these conditions may use the College of Law’s institutional Scholastica account to submit up to two unique and distinct articles per academic year for publication to a maximum of 25 law journals per article. Students may submit their article to additional journals but at the expense of the student.” For questions about funding through the College of Law's Institutional account, please contact Elaine Bradshaw ([email protected]).

- Boston College Law Library - Law Review Companions This database provides a list of 111 online companions to major U.S. law reviews. The table lists whether student work is accepted, the preferred submission method, and other relevant information.

- Washington & Lee Law Journal Rankings This database provides rankings (largely based on cite counts on Westlaw) for law reviews and journals. Use the Subjects filter to identify law reviews relevant to particular areas of law. Also useful as a tool for linking you to the website for each law review listed.

- HeinOnline Bar Journal Library This HeinOnline database contains a list of bar journals by state. Note, HeinOnline includes historical coverage of bar journals that have discontinued publication, so further research may be required.

- Oklahoma Bar Journal Submission information This website contains information about the different kinds of submissions authors can make and the requirements for such submissions to the Oklahoma Bar Journal.

- American Bar Association Writing Competitions and Contests This website contains a list of various ABA writing competitions which generally include awards for winners including cash prizes, comped conference trips, and potential selection for publication.

- AccessLex Law School Scholarship Databank – Writing Competitions This databank lists over 800 scholarship and writing competition opportunities. You can filter these opportunities by Application Deadline Month to quickly identify relevant results.

- Association of American Law Schools – Upcoming Symposia This website provides an extensive list of upcoming symposia which can be cross-referenced with the above list of law reviews that accept student-authored pieces to identify potential symposia issues of interest for purposes of publication.

- Last Updated: Apr 2, 2024 12:08 PM

- URL: https://guides.ou.edu/lawstudentpublishing

- OU Libraries Facebook

- OU Libraries Twitter

- OU Libraries Youtube

- OU Libraries Instagram

University Libraries 401 W. Brooks St Norman, OK 73019 (405) 325-3341

Important links

- About This Site

- Libraries Jobs

- Accessibility

- OU Policies

- Legal Notice

How to Write an Abstract

- Research Process

Abstracts are the first thing people read when they come across your manuscript on online databases. It's also a deciding factor in peer reviews. Do not overlook its importance.

Updated on March 24, 2022

You've finished your entire paper. All those hours put into your research have finally paid off. Research writing can be tough .

But hold on; you're not quite finished yet. You forgot to write your abstract!

The abstract can sometimes be overlooked, but that does not mean it's unimportant. In fact, some researchers argue that the abstract is the most important part of your manuscript. It's the first thing people read when they come across your manuscript on online databases. Depending on how well written it is, it could also be the first and last thing your audience reads.

It's also what publications and journals use to determine whether they want to publish your research. Continue reading to learn how to write an abstract and how AJE can help you with your writing.

What is an abstract?

An abstract is a concise summary of the major findings in your research paper. It is usually found at the beginning of your research paper. A good abstract should be able to give the average lay reader a strong sense of the main findings within your full-text paper.

Abstracts are typically one paragraph depending on how you decide to structure it. Your target publication could have specific guidelines that determine the structure of your abstract. However, all abstracts have the commonality of being brief summaries of your longer research.

Types of abstracts

Informative abstracts.

A good informative abstract acts as a thorough summary for your full paper. It should be a structured abstract. It includes sections for the introduction, methods, results, discussion and conclusion. Each section should only be a couple sentences each. The total number of words should typically be around 250, but they can be longer, too.

Informative abstracts are typically meant for psychology, science, and engineering papers.

Components of an informative abstract

Introduction.

The introduction should only be one or two sentences. This is where you state your thesis and why your research is important. The introduction should state:

- Your paper's purpose

- The problems your research solves

- Historical references

Start writing your methods sections by explaining what you did in the experiment. Begin by setting the scene. The methods section should only be a couple sentences long.

Who/what was involved in the study?

- State who or what was used in the experiment. Include the population studied; mention any plants, animals, or humans and how many were involved.

When did the experiment take place?

- State the time frame or duration of the experiment.

Where did the experiment take place?

- Give the geographical location of the experiment.

Tips for writing the methods section

- Write your research methods section as you are doing your experimentation. Some details of your experiment could be left out if you wait too long between the experiment and writing an abstract.

- If you're having trouble structuring your methods, look at what others have done. Look at an abstract from a study in your target publication.

The results section should describe your most important findings with the data to back it up. Write this section in the past tense.

Conclusions

Your conclusions section should only be two to three sentences. In this short amount of space, you should include your interpretation of the experiment to answer the main question of your research. It should answer this question: How do these results have an effect on my area of study or the wider population?

Descriptive abstracts

A descriptive abstract is also called a limited abstract for a good reason. It's much shorter than an informative abstract - about half the size. It's a very brief summary.

It should include background information, the study's purpose, the focus of the paper, and an optional overview of the contents.

A descriptive abstract is generally used for psychology, social sciences, and humanities papers.

Tip for writing a descriptive abstract

If you're having trouble writing a descriptive abstract, take your main headings from your table of contents and write them into a paragraph format.

Critical abstracts

A critical abstract is less common than the other abstracts, but it's still worth knowing. It still includes your general findings, but it also has a section devoted to the completeness, validity, and readability of your paper. In a critical abstract, your work is compared with other studies on your subject matter.

Incorporate keywords found in your research paper

It is wise to list the key phrases and words in your research paper for Search Engine Optimization (SEO) purposes. Your key terms section helps search engines like Google and Bing direct readers and other researchers to your work. The key words section comes at the bottom of your abstract. It can be formatted as follows:

Keywords: example 1, example 2, example 3

How to format the abstract

Some researchers make their abstract a single paragraph that looks like one giant block of text. If you wish to make it easier on your readers, you can break your abstract into sections depending on your target journal's specifications.

It should immediately follow the title page. There should be no page number on the abstract page.

When should you write your abstract?

Since the abstract is the first thing your audience reads, it would make sense to write an abstract first, right?

Not exactly.

Trying to summarize your research before you've written your research paper can be incredibly challenging.

Instead, the abstract should be the last thing you write. Your research should still be fresh in your mind and you should have no problem summarizing the important findings.

There are plenty of other tips for writing your abstract as well.

Final Thoughts

Abstract writing can be difficult. Luckily, AJE's editing staff can edit your abstract . If your target journal requests a graphic abstract, our Figure Formatting team can make you one for you.

Jonny Rhein, BA

See our "Privacy Policy"

How to Write Law/Legal Articles (Structure & Format to Use)

How to Write Law Articles : Writing law article is a very demanding undertaking. Law is not a general field; therefore there are some peculiarities ascribable to it. A writer who seeks to write law article must be well grounded in law, particularly on the topic or area intended to be written on. Just like every other article, a law article must have purpose and direction. It must as well have a target audience. These two preliminaries are the crossways to a good law article.

Recommended: How to answer Law questions excellently.

Table of Contents

How to Write a Legal/Law Article (Structure and Format to Follow)

The Preliminaries: A writer is usually motivated to write on a particular topic by a reason or reasons. These reasons constitute the purpose and direction of the article. This raises the question as to what exactly the writer intends to achieve by the writing. The writer may have been motivated to develop an appraisal on a particular topic, and this is usually the case, because an appraisal permits the writer to assess the totality an applicability of the intended principles and then develop their personal opinion on them, after which the writer recommends solutions or alternatives if any.

All these are firstly considered in the preliminary stage. Another important consideration in the preliminary stage is the audience. Every piece of writing has a targeted audience. It is the category of audience borne in mind by the writer that inspires the language of the article and sometimes the purpose and direction too.

Also see: How to become a successful lawyer

Abstract: An abstract is an abridgement or summary of a longer publication. A proper law article must have an abstract. The abstract should come immediately after the title. It is under the abstract that the writer gives a brief overview of the content and purpose of the article. The abstract must bear the readers in mind in such a way that after perusing through the abstract, the reader should have a clue of the article’s purpose and direction.

An abstract must not be long. It is necessary to draft an abstract before writing the rest of the article. The draft abstract can always be reviewed from time to time before publication. Some writers may however find it more preferable to complete the article first before writing the abstract. This is also not a bad practice.

Here is an example of what an abstract should look like. – “ In this article the writer considered the relevance of adoption laws in protecting the interest of the adopted child. The article went further to highlight areas which though may have been intended by the legislature to sanctify the adoption procedures, actually occasions in justice against the adoptive parents. Relevant case laws and statutory authorities were cited to juxtapose the positions, and finally, the writer thereon proffers solutions which stand a better practice in the contemporary human existence” .

Recommended: Best time to read and understand effectively

The body/content of the article: In a law article, an abstract do not qualify as an introduction. The introduction should come first under the body of the article. It is under the introductory stage that the writer lays adequate foundation on the topic being written on. The introduction may include definition of terms, prior and present positions of the law, identification of issues, etc.

After the introductory stage, the analysis stage follows. It is under this stage that the writer begins to tackle the issues raised during the introduction. The analysis must be presented smoothly, systematically and logically in order to carry the audience along. The analysis stage should discuss the relevant principles of the law in details. The analysis stage can as well include statistics gathered by the writer which can be used to illustrate the practicality of principles or for any purpose relevant to the article.

Recommended: Differences Between a Law and a Policy

The use of Authorities: in law, it is the practice that salient principles of law must be backed up with authorities. A law principle not supported by an authority is viewed as a mere opinion and as such, weight is attached to it at the discretion of the reader. In the order of strength and precedence, legal authorities include; the provisions of any domestic or domesticated enactment, case laws, law dictionaries, foreign laws and cases, obiter dictum and comments by legal authors.

These authorities can be employed by the writer in any stage of writing; whether the introductory stage, analysis stage or conclusion. Every legal article must be backed up with authorities. Where authorities are cited by the writer, their citations must be provided correctly and positioned appropriately. For the case laws, the proper citation should include the case’s citation in the law report (the report name, volume, and year).

Comments made by legal authors should be cited with the name of the author together with the occasion or the piece where the comment was made, and also the year or edition. The authorities cited must wear a different body from other contents of the article. Authorities are to be specifically highlighted either by Capitalization, italics, bold, or the combination of any.

Recommended: Top 10 Law firms in the world

Conclusion: Having shown full working in the analysis stage, the conclusion stage warps up the entire piece of work. At the conclusion stage, the writer provides the answer to the issues raised in the introductory stage. It is under this stage that the writer proffer solutions to the problems identified. Also it is under this stage that the writer makes clear his own view or position on the topic discussed.

This stage must as well resolve the questions raised in the mind of the readers in the course of their reading the article. The conclusion stage need not necessarily be long. At the conclusion stage, readers will always refer back to the title of the article to observe whether the purpose and direction of the article was actually achieved. The conclusion stage is not optional for a law article; it is compulsory.

Also see: Advantages and Disadvantages Of Being A Famous/Popular Person

Other contemporary issues

Language : it is best for the language of a law article to be simple. This is especially if the target audience includes the larger society. Simplicity in language enhances readability and clarity, and the attainment of the purpose and direction of the article.

Simplicity of language does not extinguish the use of legal jargons. When legal jargons are used, it should be specifically highlighted by the use of italics. Where the jargon employed is not a regular one, it may be necessary to add its meaning to the footnote. In all, it would be a very stressful task for your readers to frequently consult the dictionary while reading your article.

Paragraphing: a law article must observe the rule of paragraphing. Proper paragraphing is very important in law writing. Paragraphing improves the readability of the work, makes the work neat, and also steers and sustains the interest of the reader. In law articles, the writer’s main points are highlighted in paragraphs.

Also see: Most Capitalist Countries In The World

Plagiarism: just like in every other academic piece, plagiarism must be totally avoided. Plagiarism is an academic offence of copying another’s work or ideas and presenting them as one’s own without acknowledging the original owner or source.

To avoid plagiarism, all the writer is required to do is to properly cite the source of the information presented.

Review: a law article must undergo several revisions before publication. The review should relate to the general context, grammar, choice of words, professionalism, citation, structure, readability, purpose attainment actualization of the target audience and perception.

Recommended: Countries with the best judicial system in the world

Writing a legal article is a tedious exercise. It demands intensive and extensive research, and then several drafts upon drafts of the article’s compilation. Purpose and direction is very much emphasized on in a law article because its relevance is a sustenance technique which permeates through all of the stages.

Edeh Samuel Chukwuemeka, ACMC, is a lawyer and a certified mediator/conciliator in Nigeria. He is also a developer with knowledge in various programming languages. Samuel is determined to leverage his skills in technology, SEO, and legal practice to revolutionize the legal profession worldwide by creating web and mobile applications that simplify legal research. Sam is also passionate about educating and providing valuable information to people.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

1 thought on “How to Write Law/Legal Articles (Structure & Format to Use)”

Thank you very much for this. It really is easy to understand and full of knowledge.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.