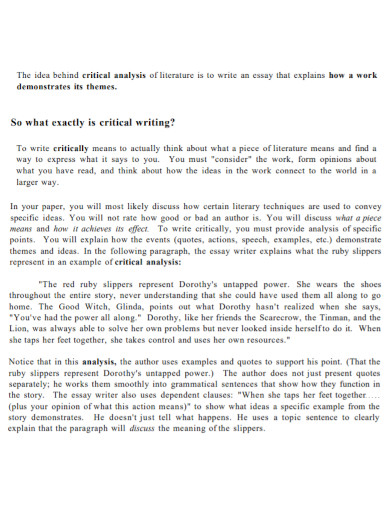

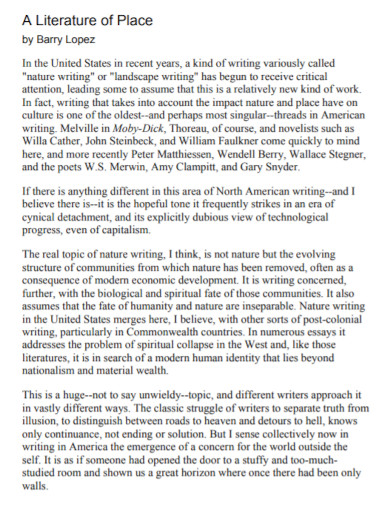

Essay on the connection between literature and life

The connection between literature and life is intimate and vital. Literature is the expression of individual and social life and thought through language. While the subject matter and treatment must be such as are of general human interest, the expression must be emotive; the form must give aesthetic pleasure and satisfaction.

Literature must not be confounded with sociology, philosophy, religion or psychology, though these give substance and depth to literature. It may or may not impart knowledge or religious or moral instruction directly. Its theme may be social problem or political revolution or religious movement; but it may, with equal justification, be an individual’s passion, problem or fantasy. But the object is not so much to teach as to delight.

Books are literature when they bring us into some relation with real life. Herein lies its power and universal appeal. While there are some who take perfection of form to be the chief pre-occupation of literature, many more are inclined to the view that the primary value of literature is its human significance. Literature must be woven out of the stuff of life as its mirror. Its value depends on the depth and breadth of the life that it paints.

It was used to be believed at one time that the deepest things in life are those that deal with what were called the eternal varieties of life. The ideas of God, for example, or of certain moral virtues, were supposed to be eternal. But experience and a wider knowledge of the changing conditions of social life have shaken man’s faith in the unchangeableness of such concepts.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Ideas change with those conditions, which are never static. Thus, peoples have different ideas of the Godhead. There are many who believe in a persona/ God; others worship an all-pervasive Presence in this Universe. The laws of morality, again, undergo changes from country to country and from age to age.

Hence, in modern times, our conception of the depth of literature is not related to this doctrine of eternal truths. We try rather to understand the forces behind these social changes. Therefore with regard to literature, our ideas of its value depends on the extent to which is has been able to express the changing conditions of social life. Great literature always grasps and reflects these truths of life that emerge triumphant out of the ruins of the past.

Literature is great because of its universality. It does not deal with the particular society of a particular community but with society as a whole or in its entirety. For this reason, the literature that appealed to the people through the spoken word had a greater appeal than that which appeals through the written word—which may not reach all men.

The recited epics of Homer, the acted plays of Shakespeare, the chanted songs of Chandidas or the communal reading of Mangala Kavya had a more extended appeal than our modern poets and novelists who express only segments of social life. Poetry that expresses intensely individual views and sentiments, novels that depict the manners of a limited class of community or deal with highly specialised problems, cannot surely be of the same level as are Tulsidas’s Ramcharitmanas or Kritibas’s Ramayana, which had and still have a mass appeal. This led Aristotle to affirm that the proper subject of poetry is human action.

The restricted appeal of modern literature resulted from the dependence of writers on the patronage of high-born persons. Necessarily such writers had to produce work that would appeal to their patrons primarily. As a result, their range became limited; Chaucer was a much richer artist; his insight into life was also profound; but he lacked the spontaneity, the range, the popular appeal of the ballad-writers, that of the ballads of “Mymansingha Gitika”.

Modern writers have developed a flair for expression, feelings and situation that are subtle and complex in language, Wordsworth realized this and advocated that poetry should be the language of common speech, the heightened speech of the rustics. The more literature is free from its class limitations, and becomes the vehicle of the thoughts and feeling of the common man, the working people, the more will it tend to become popular and public.

Literature mast has social functions. Art for art’s sake, pursuit of pure beauty through art, the creation of a literary or artist’s masterpiece as an end in itself—are now falling into disfavor. Great literature must always serve the need of the people. It must voice their inmost desires, their noblest aspirations.

In the second place, by drawing the attention of the people to the emerging truths of life, literature should lead the people forward to a higher plane of life and thought. That is what Walt Whitman meant when he said that the object of literature is “to free, arouse and dilate the human mind”. Literature, in this sense, must emancipate the mind from its limitations; arouse it to a consciousness of the dynamic urge of life.

Related Articles:

- Essay on the connection between literature and society

- What was the impact of the revival of ancient Greco-Roman culture on the life and literature during Renaissance period

- Essay on the Role of Press and Literature for the independence of India

- Essay on the connection between Art and Mortality

How Literature Can Change Your Life

- March 10, 2024

If you’re reading this, you likely already know that literature is amazing. Think back to all the experiences you’ve had curling up with a book, the people you’ve known in these fictional worlds, the places the tales have taken you, the memories you have implanted in your brain all because someone put pen to paper.

Literature is about creating something purely out of words. And in that way, it’s magic .

But while you can know all this deep down, have you ever really asked yourself the question: how can literature change your life?

For book lovers and writers, the question makes you stop for a second. How can you even ask that?

Well, we’re asking. Why? Because taking time to really think about it makes us fall in love all over again with the written word. We won’t cover everything, but let’s look at some of the major ways that literature can change your life.

Reading Makes You More Empathic

It’s true. Reading, and reading fiction in particular, makes us better at working out what other people are thinking and feeling. A 2015 study by Diana Tamir at the Princeton Social Neuroscience Lab showed that reading fiction exercises the part of the brain we use to empathize with others.

So in a way, all you beautiful readers out there are gaining ESP with every novel you pick up.

In the complex and multicultural world we live in, empathy is more important than ever. But it’s the core of the human experience, even in the best of times. As long as we are lucky enough to be on earth, we share it with others. Reading literature makes that a joy rather than a burden.

What You Read Is Also About What You Aren’t Reading

Here is one of the newest benefits to reading literature: it keeps us away from other forms of pastimes that are making us more anxious and depressed . The biggest one is social media, the place where confidence and attention spans go to die.

It can be hard to parse out whether social media causes depression or people who are depressed tend to use social media more. But growing evidence is pointing to the idea that these platforms are hurting our life satisfaction.

Reading not only helps us avoid the dreaded FOMO and endless comparison to others that social media brings, it also helps keep our attention spans.

By not entering into the dopamine-hacking scroll that is your feed, you are protecting your ability to think about the same thing for a prolonged period of time. So yeah, you beautiful readers are also becoming geniuses.

Reading Literature Expands Your Mind

Maybe the most important part of literature is its ability to transport us into the mind of another person. You can pull out your phone and take a video of the room around you, and it will almost perfectly document what the room looks and sounds like right now.

But it won’t tell someone else what it was like for you to be in the room.

Literature is a portal into other people. It allows us to break down the doors of our culture, identity, and personal past. It brings us into close connection with others — allowing us to see all the horror, honor, and awe lurking in the human experience.

It shuttles you off into different time periods (even the future!) and places. A library card is free, and it unlocks the ability to expand your mind into the cosmos, hopping around like a mystical being able to inhabit the minds of others. That’s truly psychedelic.

Ultimately, if reading fiction did nothing but engross us in beautiful language and fantastic tales, we’d still do it. But when we recount only a few of the benefits literature provides, it reminds us just how amazing it is we get to read at all.

So what are you waiting for? Get reading!

Solutions by Litwise

Leave the first comment (cancel reply).

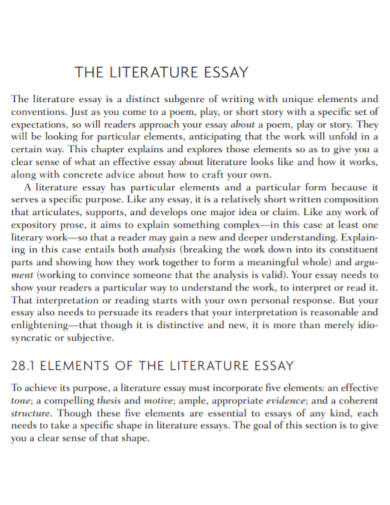

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 What Is Literature and Why Do We Study It?

In this book created for my English 211 Literary Analysis introductory course for English literature and creative writing majors at the College of Western Idaho, I’ll introduce several different critical approaches that literary scholars may use to answer these questions. The critical method we apply to a text can provide us with different perspectives as we learn to interpret a text and appreciate its meaning and beauty.

The existence of literature, however we define it, implies that we study literature. While people have been “studying” literature as long as literature has existed, the formal study of literature as we know it in college English literature courses began in the 1940s with the advent of New Criticism. The New Critics were formalists with a vested interest in defining literature–they were, after all, both creating and teaching about literary works. For them, literary criticism was, in fact, as John Crowe Ransom wrote in his 1942 essay “ Criticism, Inc., ” nothing less than “the business of literature.”

Responding to the concern that the study of literature at the university level was often more concerned with the history and life of the author than with the text itself, Ransom responded, “the students of the future must be permitted to study literature, and not merely about literature. But I think this is what the good students have always wanted to do. The wonder is that they have allowed themselves so long to be denied.”

We’ll learn more about New Criticism in Section Three. For now, let’s return to the two questions I posed earlier.

What is literature?

First, what is literature ? I know your high school teacher told you never to look up things on Wikipedia, but for the purposes of literary studies, Wikipedia can actually be an effective resource. You’ll notice that I link to Wikipedia articles occasionally in this book. Here’s how Wikipedia defines literature :

“ Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction , drama , and poetry . [1] In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include oral literature , much of which has been transcribed. [2] Literature is a method of recording, preserving, and transmitting knowledge and entertainment, and can also have a social, psychological, spiritual, or political role.”

This definition is well-suited for our purposes here because throughout this course, we will be considering several types of literary texts in a variety of contexts.

I’m a Classicist—a student of Greece and Rome and everything they touched—so I am always interested in words with Latin roots. The Latin root of our modern word literature is litera , or “letter.” Literature, then, is inextricably intertwined with the act of writing. But what kind of writing?

Who decides which texts are “literature”?

The second question is at least as important as the first one. If we agree that literature is somehow special and different from ordinary writing, then who decides which writings count as literature? Are English professors the only people who get to decide? What qualifications and training does someone need to determine whether or not a text is literature? What role do you as the reader play in this decision about a text?

Let’s consider a few examples of things that we would all probably classify as literature. I think we can all (probably) agree that the works of William Shakespeare are literature. We can look at Toni Morrison’s outstanding ouvre of work and conclude, along with the Nobel Prize Committee, that books such as Beloved and Song of Solomon are literature. And if you’re taking a creative writing course and have been assigned the short stories of Raymond Carver or the poems of Joy Harjo , you’re probably convinced that these texts are literature too.

In each of these three cases, a different “deciding” mechanism is at play. First, with Shakespeare, there’s history and tradition. These plays that were written 500 years ago are still performed around the world and taught in high school and college English classes today. It seems we have consensus about the tragedies, histories, comedies, and sonnets of the Bard of Avon (or whoever wrote the plays).

In the second case, if you haven’t heard of Toni Morrison (and I am very sorry if you haven’t), you probably have heard of the Nobel Prize. This is one of the most prestigious awards given in literature, and since she’s a winner, we can safely assume that Toni Morrison’s works are literature.

Finally, your creative writing professor is an expert in their field. You know they have an MFA (and worked hard for it), so when they share their favorite short stories or poems with you, you trust that they are sharing works considered to be literature, even if you haven’t heard of Raymond Carver or Joy Harjo before taking their class.

(Aside: What about fanfiction? Is fanfiction literature?)

We may have to save the debate about fan fiction for another day, though I introduced it because there’s some fascinating and even literary award-winning fan fiction out there.

Returning to our question, what role do we as readers play in deciding whether something is literature? Like John Crowe Ransom quoted above, I think that the definition of literature should depend on more than the opinions of literary critics and literature professors.

I also want to note that contrary to some opinions, plenty of so-called genre fiction can also be classified as literature. The Nobel Prize winning author Kazuo Ishiguro has written both science fiction and historical fiction. Iain Banks , the British author of the critically acclaimed novel The Wasp Factory , published popular science fiction novels under the name Iain M. Banks. In other words, genre alone can’t tell us whether something is literature or not.

In this book, I want to give you the tools to decide for yourself. We’ll do this by exploring several different critical approaches that we can take to determine how a text functions and whether it is literature. These lenses can reveal different truths about the text, about our culture, and about ourselves as readers and scholars.

“Turf Wars”: Literary criticism vs. authors

It’s important to keep in mind that literature and literary theory have existed in conversation with each other since Aristotle used Sophocles’s play Oedipus Rex to define tragedy. We’ll look at how critical theory and literature complement and disagree with each other throughout this book. For most of literary history, the conversation was largely a friendly one.

But in the twenty-first century, there’s a rising tension between literature and criticism. In his 2016 book Literature Against Criticism: University English and Contemporary Fiction in Conflict, literary scholar Martin Paul Eve argues that twenty-first century authors have developed

a series of novelistic techniques that, whether deliberate or not on the part of the author, function to outmanoeuvre, contain, and determine academic reading practices. This desire to discipline university English through the manipulation and restriction of possible hermeneutic paths is, I contend, a result firstly of the fact that the metafictional paradigm of the high-postmodern era has pitched critical and creative discourses into a type of productive competition with one another. Such tensions and overlaps (or ‘turf wars’) have only increased in light of the ongoing breakdown of coherent theoretical definitions of ‘literature’ as distinct from ‘criticism’ (15).

One of Eve’s points is that by narrowly and rigidly defining the boundaries of literature, university English professors have inadvertently created a situation where the market increasingly defines what “literature” is, despite the protestations of the academy. In other words, the gatekeeper role that literary criticism once played is no longer as important to authors. For example, (almost) no one would call 50 Shades of Grey literature—but the salacious E.L James novel was the bestselling book of the decade from 2010-2019, with more than 35 million copies sold worldwide.

If anyone with a blog can get a six-figure publishing deal , does it still matter that students know how to recognize and analyze literature? I think so, for a few reasons.

- First, the practice of reading critically helps you to become a better reader and writer, which will help you to succeed not only in college English courses but throughout your academic and professional career.

- Second, analysis is a highly sought after and transferable skill. By learning to analyze literature, you’ll practice the same skills you would use to analyze anything important. “Data analyst” is one of the most sought after job positions in the New Economy—and if you can analyze Shakespeare, you can analyze data. Indeed.com’s list of top 10 transferable skills includes analytical skills , which they define as “the traits and abilities that allow you to observe, research and interpret a subject in order to develop complex ideas and solutions.”

- Finally, and for me personally, most importantly, reading and understanding literature makes life make sense. As we read literature, we expand our sense of what is possible for ourselves and for humanity. In the challenges we collectively face today, understanding the world and our place in it will be important for imagining new futures.

A note about using generative artificial intelligence

As I was working on creating this textbook, ChatGPT exploded into academic consciousness. Excited about the possibilities of this new tool, I immediately began incorporating it into my classroom teaching. In this book, I have used ChatGPT to help me with outlining content in chapters. I also used ChatGPT to create sample essays for each critical lens we will study in the course. These essays are dry and rather soulless, but they do a good job of modeling how to apply a specific theory to a literary text. I chose John Donne’s poem “The Canonization” as the text for these essays so that you can see how the different theories illuminate different aspects of the text.

I encourage students in my courses to use ChatGPT in the following ways:

- To generate ideas about an approach to a text.

- To better understand basic concepts.

- To assist with outlining an essay.

- To check grammar, punctuation, spelling, paragraphing, and other grammar/syntax issues.

If you choose to use Chat GPT, please include a brief acknowledgment statement as an appendix to your paper after your Works Cited page explaining how you have used the tool in your work. Here is an example of how to do this from Monash University’s “ Acknowledging the Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence .”

I acknowledge the use of [insert AI system(s) and link] to [specific use of generative artificial intelligence]. The prompts used include [list of prompts]. The output from these prompts was used to [explain use].

Here is more information about how to cite the use of generative AI like ChatGPT in your work. The information below was adapted from “Acknowledging and Citing Generative AI in Academic Work” by Liza Long (CC BY 4.0).

The Modern Language Association (MLA) uses a template of core elements to create citations for a Works Cited page. MLA asks students to apply this approach when citing any type of generative AI in their work. They provide the following guidelines:

Cite a generative AI tool whenever you paraphrase, quote, or incorporate into your own work any content (whether text, image, data, or other) that was created by it. Acknowledge all functional uses of the tool (like editing your prose or translating words) in a note, your text, or another suitable location. Take care to vet the secondary sources it cites. (MLA)

Here are some examples of how to use and cite generative AI with MLA style:

Example One: Paraphrasing Text

Let’s say that I am trying to generate ideas for a paper on Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s short story “The Yellow Wallpaper.” I ask ChatGPT to provide me with a summary and identify the story’s main themes. Here’s a link to the chat . I decide that I will explore the problem of identity and self-expression in my paper.

My Paraphrase of ChatGPT with In-Text Citation

The problem of identity and self expression, especially for nineteenth-century women, is a major theme in “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (“Summarize the short story”).

Works Cited Entry

“Summarize the short story “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Include a breakdown of the main themes” prompt. ChatGPT. 24 May Version, OpenAI, 20 Jul. 2023, https://chat.openai.com/share/d1526b95-920c-48fc-a9be-83cd7dfa4be5

Example Two: Quoting Text

In the same chat, I continue to ask ChatGPT about the theme of identity and self expression. Here’s an example of how I could quote the response in the body of my paper:

When I asked ChatGPT to describe the theme of identity and self expression, it noted that the eponymous yellow wallpaper acts as a symbol of the narrator’s self-repression. However, when prompted to share the scholarly sources that formed the basis of this observation, ChatGPT responded, “As an AI language model, I don’t have access to my training data, but I was trained on a mixture of licensed data, data created by human trainers, and publicly available data. OpenAI, the organization behind my development, has not publicly disclosed the specifics of the individual datasets used, including whether scholarly sources were specifically used” (“Summarize the short story”).

It’s worth noting here that ChatGPT can “ hallucinate ” fake sources. As a Microsoft training manual notes, these chatbots are “built to be persuasive, not truthful” (Weiss &Metz, 2023). The May 24, 2023 version will no longer respond to direct requests for references; however, I was able to get around this restriction fairly easily by asking for “resources” instead.

When I ask for resources to learn more about “The Yellow Wallpaper,” here is one source it recommends:

“Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper: A Symptomatic Reading” by Elaine R. Hedges: This scholarly article delves into the psychological and feminist themes of the story, analyzing the narrator’s experience and the implications of the yellow wallpaper on her mental state. It’s available in the journal “Studies in Short Fiction.” (“Summarize the short story”).

Using Google Scholar, I look up this source to see if it’s real. Unsurprisingly, this source is not a real one, but it does lead me to another (real) source: Kasmer, Lisa. “Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s’ The Yellow Wallpaper’: A Symptomatic Reading.” Literature and Psychology 36.3 (1990): 1.

Note: ALWAYS check any sources that ChatGPT or other generative AI tools recommend.

For more information about integrating and citing generative artificial intelligence tools such as ChatGPT, please see this section of Write What Matters.

I acknowledge that ChatGPT does not respect the individual rights of authors and artists and ignores concerns over copyright and intellectual property in its training; additionally, I acknowledge that the system was trained in part through the exploitation of precarious workers in the global south. In this work I specifically used ChatGPT to assist with outlining chapters, providing background information about critical lenses, and creating “model” essays for the critical lenses we will learn about together. I have included links to my chats in an appendix to this book.

Critical theories: A targeted approach to writing about literature

Ultimately, there’s not one “right” way to read a text. In this book. we will explore a variety of critical theories that scholars use to analyze literature. The book is organized around different targets that are associated with the approach introduced in each chapter. In the introduction, for example, our target is literature. In future chapters you’ll explore these targeted analysis techniques:

- Author: Biographical Criticism

- Text: New Criticism

- Reader: Reader Response Criticism

- Gap: Deconstruction (Post-Structuralism)

- Context: New Historicism and Cultural Studies

- Power: Marxist and Postcolonial Criticism

- Mind: Psychological Criticism

- Gender: Feminist, Post Feminist, and Queer Theory

- Nature: Ecocriticism

Each chapter will feature the target image with the central approach in the center. You’ll read a brief introduction about the theory, explore some primary texts (both critical and literary), watch a video, and apply the theory to a primary text. Each one of these theories could be the subject of its own entire course, so keep in mind that our goal in this book is to introduce these theories and give you a basic familiarity with these tools for literary analysis. For more information and practice, I recommend Steven Lynn’s excellent Texts and Contexts: Writing about Literature with Critical Theory , which provides a similar introductory framework.

I am so excited to share these tools with you and see you grow as a literary scholar. As we explore each of these critical worlds, you’ll likely find that some critical theories feel more natural or logical to you than others. I find myself much more comfortable with deconstruction than with psychological criticism, for example. Pay attention to how these theories work for you because this will help you to expand your approaches to texts and prepare you for more advanced courses in literature.

P.S. If you want to know what my favorite book is, I usually tell people it’s Herman Melville’s Moby Dick . And I do love that book! But I really have no idea what my “favorite” book of all time is, let alone what my favorite book was last year. Every new book that I read is a window into another world and a template for me to make sense out of my own experience and better empathize with others. That’s why I love literature. I hope you’ll love this experience too.

writings in prose or verse, especially : writings having excellence of form or expression and expressing ideas of permanent or universal interest (Merriam Webster)

Critical Worlds Copyright © 2024 by Liza Long is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Essays About Literature: Top 6 Examples and 8 Prompts

Society and culture are formed around literature. If you are writing essays about literature, you can use the essay examples and prompts featured in our guide.

It has been said that language holds the key to all human activities, and literature is the expression of language. It teaches new words and phrases, allows us to better our communication skills, and helps us learn more about ourselves.

Whether you are reading poems or novels, we often see parts of ourselves in the characters and themes presented by the authors. Literature gives us ideas and helps us determine what to say, while language gives form and structure to our ideas, helping us convey them.

6 Helpful Essay Examples

1. importance of literature by william anderson, 2. philippine literature by jean hodges, 3. african literature by morris marshall.

- 4. Nine Questions From Children’s Literature That Every Person Should Answer by Shaunta Grimes

5. Exploring tyranny and power in Macbeth by Tom Davey

6. guide to the classics: homer’s odyssey by jo adetunji, 1. the importance of literature, 2. comparing and contrasting two works of literature , 3. the use of literary devices, 4. popular adaptations of literature, 5. gender roles in literature, 6. analysis of your chosen literary work, 7. fiction vs. non-fiction, 8. literature as an art form.

“Life before literature was practical and predictable, but in the present-day, literature has expanded into countless libraries and into the minds of many as the gateway for comprehension and curiosity of the human mind and the world around them. Literature is of great importance and is studied upon as it provides the ability to connect human relationships and define what is right and what is wrong.”

Anderson writes about why an understanding of literature is crucial. It allows us to see different perspectives of people from different periods, countries, and cultures: we are given the ability to see the world from an entirely new lens. As a result, we obtain a better judgment of situations. In a world where anything can happen, literature gives us the key to enacting change for ourselves and others. You might also be interested in these essays about Beowulf .

“So successful were the efforts of colonists to blot out the memory of the country’s largely oral past that present-day Filipino writers, artists and journalists are trying to correct this inequity by recognizing the country’s wealth of ethnic traditions and disseminating them in schools through mass media. The rise of nationalistic pride in the 1960s and 1970s also helped bring about this change of attitude among a new breed of Filipinos concerned about the “Filipino identity.””

In her essay, Hodges writes about the history of Philippine literature. Unfortunately, much of Philippine literary history has been obscured by Spanish colonization, as the written works of the Spanish largely replaced the oral tradition of the native Filipinos. A heightened sense of nationalism has recently led to a resurgence in Filipino tradition, including ancient Philippine literature.

“In fact, the common denominator of the cultures of the African continent is undoubtedly the oral tradition. Writing on black Africa started in the middle Ages with the introduction of the Arabic language and later, in the nineteenth century with introduction of the Latin alphabet. Since 1934, with the birth of the “Negritude.” African authors began to write in French or in English.”

Marshall explores the history of African literature, particularly the languages it was written over time. It was initially written in Arabic and native languages; however, with the “Negritude” movement, writers began composing their works in French or English. This movement allowed African writers to spread their work and gain notoriety. Marshall gives examples of African literature, shedding light on their lyrical content.

4. Nine Questions From Children’s Literature That Every Person Should Answer by Shaunta Grimes

“ They asked me questions — questions about who I am, what I value, and where I’m headed — and pushed me to think about the answers. At some point in our lives, we decide we know everything we need to know. We stop asking questions. To remember what’s important, it sometimes helps to return to that place of childlike curiosity and wonder.”

Grimes’ essay is a testament to how much we can learn from literature, even as simple as children’s stories. She explains how different works of children’s literature, such as Charlotte’s Web and Little Women, can inspire us, help us maximize our imagination, and remind us of the fleeting nature of life. Most importantly, however, they remind us that the future is uncertain, and maximizing it is up to us.

“This is a world where the moral bar has been lowered; a world which ‘sinks beneath the yoke’. In the Macbeths, we see just how terribly the human soul can be corrupted. However, this struggle is played out within other characters too. Perhaps we’re left wondering: in such a dog-eat-dog world, how would we fare?”

The corruption that power can lead to is genuine; Davey explains how this theme is present in Shakespeare’s Macbeth . Even after being honored, Macbeth still wishes to be king and commits heinous acts of violence to achieve his goals. Violence is prevalent throughout the play, but Macbeth and Lady Macbeth exemplify the vicious cycle of bloodshed through their ambition and power.

“Polyphemus is blinded but survives the attack and curses the voyage home of the Ithacans. All of Odysseus’s men are eventually killed, and he alone survives his return home, mostly because of his versatility and cleverness. There is a strong element of the trickster figure about Homer’s Odysseus.”

Adetunji also exposes a notable work of literature, in this case, Homer’s Odyssey . She goes over the epic poem and its historical context and discusses Odysseus’ most important traits: cleverness and courage. As the story progresses, he displays great courage and bravery in his exploits, using his cunning and wit to outsmart his foes. Finally, Adetunji references modern interpretations of the Odyssey in film, literature, and other media.

8 Prompts for Essays About Literature

In your essay, write about the importance of literature; explain why we need to study literature and how it can help us in the future. Then, give examples of literary works that teach important moral lessons as evidence.

For your essay, choose two works of literature with similar themes. Then, discuss their similarities and differences in plot, theme, and characters. For example, these themes could include death, grief, love and hate, or relationships. You can also discuss which of the two pieces of literature presents your chosen theme better.

Writers use literary devices to enhance their literary works and emphasize important points. Literary devices include personification, similes, metaphors, and more. You can write about the effectiveness of literary devices and the reasoning behind their usage. Research and give examples of instances where authors use literary devices effectively to enhance their message.

Literature has been adapted into cinema, television, and other media time and again, with series such as Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter turning into blockbuster franchises. Explore how these adaptations diverge from their source material yet retain the key themes the writer composed the work with in mind. If this seems confusing, research first and read some essay examples.

Literature reflects the ideas of the period it is from; for example, ancient Greek literature, such as Antigone, depicts the ideal woman as largely obedient and subservient, to an extent. For your essay, you can write about how gender roles have evolved in literature throughout the years, specifically about women. Be sure to give examples to support your points.

Choose a work of literature that interests you and analyze it in your essay. You can use your favorite novel, book, or screenplay, explain the key themes and characters and summarize the plot. Analyze the key messages in your chosen piece of literature, and discuss how the themes are enhanced through the author’s writing techniques.

Literature can be divided into two categories: fiction, from the writer’s imagination, and non-fiction, written about actual events. Explore their similarities and differences, and give your opinion on which is better. For a strong argument, provide ample supporting details and cite credible sources.

Literature is an art form that uses language, so do you believe it is more effective in conveying its message? Write about how literature compares to other art forms such as painting and sculpture; state your argument and defend it adequately.

Tip: If writing an essay sounds like a lot of work, simplify it. Write a simple 5 paragraph essay instead.

For help picking your next essay topic, check out the best essay topics about social media .

Martin is an avid writer specializing in editing and proofreading. He also enjoys literary analysis and writing about food and travel.

View all posts

- Science & Math

- Sociology & Philosophy

- Law & Politics

- Importance of Literature: Essay

Literature is the foundation of life . It places an emphasis on many topics from human tragedies to tales of the ever-popular search for love. While it is physically written in words, these words come alive in the imagination of the mind, and its ability to comprehend the complexity or simplicity of the text.

Literature enables people to see through the lenses of others, and sometimes even inanimate objects; therefore, it becomes a looking glass into the world as others view it. It is a journey that is inscribed in pages and powered by the imagination of the reader.

Ultimately, literature has provided a gateway to teach the reader about life experiences from even the saddest stories to the most joyful ones that will touch their hearts.

From a very young age, many are exposed to literature in the most stripped-down form: picture books and simple texts that are mainly for the sole purpose of teaching the alphabet etc. Although these are not nearly as complex as an 800-page sci-fi novel, it is the first step that many take towards the literary world.

Progressively, as people grow older, they explore other genres of books, ones that propel them towards curiosity of the subject, and the overall book.

Reading and being given the keys to the literature world prepares individuals from an early age to discover the true importance of literature: being able to comprehend and understand situations from many perspectives.

Physically speaking, it is impossible to be someone else. It is impossible to switch bodies with another human being, and it is impossible to completely understand the complexity of their world. Literature, as an alternative, is the closest thing the world has to being able to understand another person whole-heartedly.

For stance, a novel about a treacherous war, written from the perspective of a soldier, allows the reader to envision their memories, their pain, and their emotions without actually being that person. Consequently, literature can act as a time machine, enabling individuals to go into a specific time period of the story, into the mind and soul of the protagonist.

With the ability to see the world with a pair of fresh eyes, it triggers the reader to reflect upon their own lives. Reading material that is relatable to the reader may teach them morals and encourage them to practice good judgment.

This can be proven through public school systems, where the books that are emphasized the most tend to have a moral-teaching purpose behind the story.

An example would be William Shakespeare’s stories, where each one is meant to be reflective of human nature – both the good and bad.

Consequently, this can promote better judgment of situations , so the reader does not find themselves in the same circumstances as perhaps those in the fiction world. Henceforth, literature is proven to not only be reflective of life, but it can also be used as a guide for the reader to follow and practice good judgment.

The world today is ever-changing. Never before has life been so chaotic and challenging for all. Life before literature was practical and predictable, but in the present-day, literature has expanded into countless libraries and into the minds of many as the gateway for comprehension and curiosity of the human mind and the world around them.

Literature is of great importance and is studied upon as it provides the ability to connect human relationships and define what is right and what is wrong. Therefore, words are alive more than ever before.

Related Posts

- What are Archetypes in Literature

- Literary Essay: Peer Editing Guidelines

- Tips for Essay Writing

- Dystopian Literature Essay: The Hunger Games

- Essay Analysis Structure

Author: William Anderson (Schoolworkhelper Editorial Team)

Tutor and Freelance Writer. Science Teacher and Lover of Essays. Article last reviewed: 2022 | St. Rosemary Institution © 2010-2024 | Creative Commons 4.0

17 Comments

Indeed literature is the foundation of life, people should know and appreciate these kind of things

its very useful info thanks

very helpful…..tnx

Hi, thanks!

First year student who wants to know about literature and how I can develop interest in reading novels.

Fantastic piece!

wonderful work

Literature is anything that is artistically presented through writtings or orally.

you may have tangible wealth untold, caskets of jewels and coffers of gold, richer than i you could never be, i know someone who told stories to me.

there’s a great saying that “the universe isn’t made up of at atoms, its made of stories” i hope none will argue this point, because this is the truest thing i have ever heard and its beautiful…….

I have learnt alot thanks to the topic literature.Literature is everything.It answers the questions why?,how? and what?.To me its my best and I will always treasure and embress literature to death.

I agree with the writer when says that Literature is the foundation of life. For me, reading is the most wonderful experience in life. It allows me to travel to other places and other times. I think that also has learnt me to emphathize with others, and see the world with other´s eyes and from their perspectives. I really like to read.

This is the first time i am presenting on a literature and i am surprised by the amount of people who are interested on the same subject. I regret my absence because i have missed much marvelous thing in that field.In fact literature is what is needed by the whole world,it brings the people of different culture together and by doing so it breaks the imposed barriers that divided people.My address now goes to the people of nowadays who prefer other source of entertainment like TV,i am not saying that TV is bad but reading is better of.COME BACK TO IT THEN.

literature is a mirror; a true reflection of our nature. it helps us see ourselves in a third persons point of view of first persons point of view. it instills virtues and condones vices. literature forms a great portion of fun and entertainment through plays, comedies and novels. it also educates individuals on life’s basic but delicate and sacred issues like love and death. it informs us of the many happenings and events that we would never have otherwise known about. literature also forms a source of livelihood to thousands of people, starting from writers,characters in plays, editors, printers,distributors and business people who deal with printed materials. literature is us and without it, we are void.

I believe that life without Literature would be unacceptable , with it i respect myself and loved human life . Next week i am going to make presentation about Literature, so i benefited from this essay.

Thanks a lot

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post comment

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a literary analysis essay | A step-by-step guide

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide

Published on January 30, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on August 14, 2023.

Literary analysis means closely studying a text, interpreting its meanings, and exploring why the author made certain choices. It can be applied to novels, short stories, plays, poems, or any other form of literary writing.

A literary analysis essay is not a rhetorical analysis , nor is it just a summary of the plot or a book review. Instead, it is a type of argumentative essay where you need to analyze elements such as the language, perspective, and structure of the text, and explain how the author uses literary devices to create effects and convey ideas.

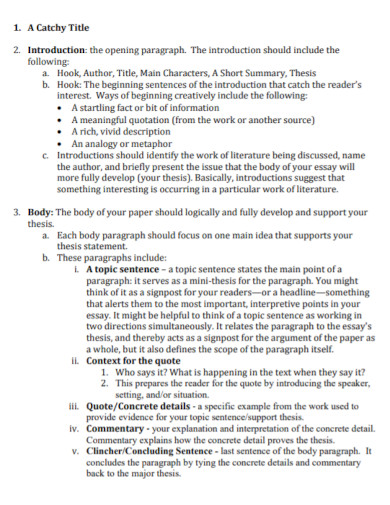

Before beginning a literary analysis essay, it’s essential to carefully read the text and c ome up with a thesis statement to keep your essay focused. As you write, follow the standard structure of an academic essay :

- An introduction that tells the reader what your essay will focus on.

- A main body, divided into paragraphs , that builds an argument using evidence from the text.

- A conclusion that clearly states the main point that you have shown with your analysis.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: reading the text and identifying literary devices, step 2: coming up with a thesis, step 3: writing a title and introduction, step 4: writing the body of the essay, step 5: writing a conclusion, other interesting articles.

The first step is to carefully read the text(s) and take initial notes. As you read, pay attention to the things that are most intriguing, surprising, or even confusing in the writing—these are things you can dig into in your analysis.

Your goal in literary analysis is not simply to explain the events described in the text, but to analyze the writing itself and discuss how the text works on a deeper level. Primarily, you’re looking out for literary devices —textual elements that writers use to convey meaning and create effects. If you’re comparing and contrasting multiple texts, you can also look for connections between different texts.

To get started with your analysis, there are several key areas that you can focus on. As you analyze each aspect of the text, try to think about how they all relate to each other. You can use highlights or notes to keep track of important passages and quotes.

Language choices

Consider what style of language the author uses. Are the sentences short and simple or more complex and poetic?

What word choices stand out as interesting or unusual? Are words used figuratively to mean something other than their literal definition? Figurative language includes things like metaphor (e.g. “her eyes were oceans”) and simile (e.g. “her eyes were like oceans”).

Also keep an eye out for imagery in the text—recurring images that create a certain atmosphere or symbolize something important. Remember that language is used in literary texts to say more than it means on the surface.

Narrative voice

Ask yourself:

- Who is telling the story?

- How are they telling it?

Is it a first-person narrator (“I”) who is personally involved in the story, or a third-person narrator who tells us about the characters from a distance?

Consider the narrator’s perspective . Is the narrator omniscient (where they know everything about all the characters and events), or do they only have partial knowledge? Are they an unreliable narrator who we are not supposed to take at face value? Authors often hint that their narrator might be giving us a distorted or dishonest version of events.

The tone of the text is also worth considering. Is the story intended to be comic, tragic, or something else? Are usually serious topics treated as funny, or vice versa ? Is the story realistic or fantastical (or somewhere in between)?

Consider how the text is structured, and how the structure relates to the story being told.

- Novels are often divided into chapters and parts.

- Poems are divided into lines, stanzas, and sometime cantos.

- Plays are divided into scenes and acts.

Think about why the author chose to divide the different parts of the text in the way they did.

There are also less formal structural elements to take into account. Does the story unfold in chronological order, or does it jump back and forth in time? Does it begin in medias res —in the middle of the action? Does the plot advance towards a clearly defined climax?

With poetry, consider how the rhyme and meter shape your understanding of the text and your impression of the tone. Try reading the poem aloud to get a sense of this.

In a play, you might consider how relationships between characters are built up through different scenes, and how the setting relates to the action. Watch out for dramatic irony , where the audience knows some detail that the characters don’t, creating a double meaning in their words, thoughts, or actions.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Your thesis in a literary analysis essay is the point you want to make about the text. It’s the core argument that gives your essay direction and prevents it from just being a collection of random observations about a text.

If you’re given a prompt for your essay, your thesis must answer or relate to the prompt. For example:

Essay question example

Is Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law” a religious parable?

Your thesis statement should be an answer to this question—not a simple yes or no, but a statement of why this is or isn’t the case:

Thesis statement example

Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law” is not a religious parable, but a story about bureaucratic alienation.

Sometimes you’ll be given freedom to choose your own topic; in this case, you’ll have to come up with an original thesis. Consider what stood out to you in the text; ask yourself questions about the elements that interested you, and consider how you might answer them.

Your thesis should be something arguable—that is, something that you think is true about the text, but which is not a simple matter of fact. It must be complex enough to develop through evidence and arguments across the course of your essay.

Say you’re analyzing the novel Frankenstein . You could start by asking yourself:

Your initial answer might be a surface-level description:

The character Frankenstein is portrayed negatively in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein .

However, this statement is too simple to be an interesting thesis. After reading the text and analyzing its narrative voice and structure, you can develop the answer into a more nuanced and arguable thesis statement:

Mary Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as.

Remember that you can revise your thesis statement throughout the writing process , so it doesn’t need to be perfectly formulated at this stage. The aim is to keep you focused as you analyze the text.

Finding textual evidence

To support your thesis statement, your essay will build an argument using textual evidence —specific parts of the text that demonstrate your point. This evidence is quoted and analyzed throughout your essay to explain your argument to the reader.

It can be useful to comb through the text in search of relevant quotations before you start writing. You might not end up using everything you find, and you may have to return to the text for more evidence as you write, but collecting textual evidence from the beginning will help you to structure your arguments and assess whether they’re convincing.

To start your literary analysis paper, you’ll need two things: a good title, and an introduction.

Your title should clearly indicate what your analysis will focus on. It usually contains the name of the author and text(s) you’re analyzing. Keep it as concise and engaging as possible.

A common approach to the title is to use a relevant quote from the text, followed by a colon and then the rest of your title.

If you struggle to come up with a good title at first, don’t worry—this will be easier once you’ve begun writing the essay and have a better sense of your arguments.

“Fearful symmetry” : The violence of creation in William Blake’s “The Tyger”

The introduction

The essay introduction provides a quick overview of where your argument is going. It should include your thesis statement and a summary of the essay’s structure.

A typical structure for an introduction is to begin with a general statement about the text and author, using this to lead into your thesis statement. You might refer to a commonly held idea about the text and show how your thesis will contradict it, or zoom in on a particular device you intend to focus on.

Then you can end with a brief indication of what’s coming up in the main body of the essay. This is called signposting. It will be more elaborate in longer essays, but in a short five-paragraph essay structure, it shouldn’t be more than one sentence.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is often read as a crude cautionary tale about the dangers of scientific advancement unrestrained by ethical considerations. In this reading, protagonist Victor Frankenstein is a stable representation of the callous ambition of modern science throughout the novel. This essay, however, argues that far from providing a stable image of the character, Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as. This essay begins by exploring the positive portrayal of Frankenstein in the first volume, then moves on to the creature’s perception of him, and finally discusses the third volume’s narrative shift toward viewing Frankenstein as the creature views him.

Some students prefer to write the introduction later in the process, and it’s not a bad idea. After all, you’ll have a clearer idea of the overall shape of your arguments once you’ve begun writing them!

If you do write the introduction first, you should still return to it later to make sure it lines up with what you ended up writing, and edit as necessary.

The body of your essay is everything between the introduction and conclusion. It contains your arguments and the textual evidence that supports them.

Paragraph structure

A typical structure for a high school literary analysis essay consists of five paragraphs : the three paragraphs of the body, plus the introduction and conclusion.

Each paragraph in the main body should focus on one topic. In the five-paragraph model, try to divide your argument into three main areas of analysis, all linked to your thesis. Don’t try to include everything you can think of to say about the text—only analysis that drives your argument.

In longer essays, the same principle applies on a broader scale. For example, you might have two or three sections in your main body, each with multiple paragraphs. Within these sections, you still want to begin new paragraphs at logical moments—a turn in the argument or the introduction of a new idea.

Robert’s first encounter with Gil-Martin suggests something of his sinister power. Robert feels “a sort of invisible power that drew me towards him.” He identifies the moment of their meeting as “the beginning of a series of adventures which has puzzled myself, and will puzzle the world when I am no more in it” (p. 89). Gil-Martin’s “invisible power” seems to be at work even at this distance from the moment described; before continuing the story, Robert feels compelled to anticipate at length what readers will make of his narrative after his approaching death. With this interjection, Hogg emphasizes the fatal influence Gil-Martin exercises from his first appearance.

Topic sentences

To keep your points focused, it’s important to use a topic sentence at the beginning of each paragraph.

A good topic sentence allows a reader to see at a glance what the paragraph is about. It can introduce a new line of argument and connect or contrast it with the previous paragraph. Transition words like “however” or “moreover” are useful for creating smooth transitions:

… The story’s focus, therefore, is not upon the divine revelation that may be waiting beyond the door, but upon the mundane process of aging undergone by the man as he waits.

Nevertheless, the “radiance” that appears to stream from the door is typically treated as religious symbolism.

This topic sentence signals that the paragraph will address the question of religious symbolism, while the linking word “nevertheless” points out a contrast with the previous paragraph’s conclusion.

Using textual evidence

A key part of literary analysis is backing up your arguments with relevant evidence from the text. This involves introducing quotes from the text and explaining their significance to your point.

It’s important to contextualize quotes and explain why you’re using them; they should be properly introduced and analyzed, not treated as self-explanatory:

It isn’t always necessary to use a quote. Quoting is useful when you’re discussing the author’s language, but sometimes you’ll have to refer to plot points or structural elements that can’t be captured in a short quote.

In these cases, it’s more appropriate to paraphrase or summarize parts of the text—that is, to describe the relevant part in your own words:

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

The conclusion of your analysis shouldn’t introduce any new quotations or arguments. Instead, it’s about wrapping up the essay. Here, you summarize your key points and try to emphasize their significance to the reader.

A good way to approach this is to briefly summarize your key arguments, and then stress the conclusion they’ve led you to, highlighting the new perspective your thesis provides on the text as a whole:

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

By tracing the depiction of Frankenstein through the novel’s three volumes, I have demonstrated how the narrative structure shifts our perception of the character. While the Frankenstein of the first volume is depicted as having innocent intentions, the second and third volumes—first in the creature’s accusatory voice, and then in his own voice—increasingly undermine him, causing him to appear alternately ridiculous and vindictive. Far from the one-dimensional villain he is often taken to be, the character of Frankenstein is compelling because of the dynamic narrative frame in which he is placed. In this frame, Frankenstein’s narrative self-presentation responds to the images of him we see from others’ perspectives. This conclusion sheds new light on the novel, foregrounding Shelley’s unique layering of narrative perspectives and its importance for the depiction of character.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, August 14). How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved April 4, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/literary-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, how to write a narrative essay | example & tips, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- African Literatures

- Asian Literatures

- British and Irish Literatures

- Latin American and Caribbean Literatures

- North American Literatures

- Oceanic Literatures

- Slavic and Eastern European Literatures

- West Asian Literatures, including Middle East

- Western European Literatures

- Ancient Literatures (before 500)

- Middle Ages and Renaissance (500-1600)

- Enlightenment and Early Modern (1600-1800)

- 19th Century (1800-1900)

- 20th and 21st Century (1900-present)

- Children’s Literature

- Cultural Studies

- Film, TV, and Media

- Literary Theory

- Non-Fiction and Life Writing

- Print Culture and Digital Humanities

- Theater and Drama

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Life writing.

- Craig Howes Craig Howes Department of English and Center for Biographical Research, University of Hawai'i at Mānoa

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.1146

- Published online: 27 October 2020

Since 1990, “life writing” has become a frequently used covering term for the familiar genres of biography, autobiography, memoir, diaries, letters, and many other forms of life narrative. Initially adopted as a critical intervention informed by post-structuralist, postmodernist, postcolonial, and especially feminist theory of the 1970s and 1980s, the term also refers to the study of life representation beyond the traditional literary and historical focus on verbal texts, encompassing not only other media—film, graphic narratives, online technologies, performance—but also research in other disciplines—psychology, anthropology, ethnic and Indigenous studies, political science, sociology, education, medicine, and any other field that records, observes, or evaluates lives.

While many critics and theorists still place their work within the realms of autobiography or biography, and others find life writing as a discipline either too ideologically driven, or still too confining conceptually, there is no question that life representation, primarily through narrative, is an important consideration for scholars engaged in virtually any field dealing with the nature and actions of human beings, or anything that lives.

- autobiography

- autofiction

- life narrative

As Julie Rak noted in 2018 , Marlene Kadar’s essay “Coming to Terms: Life Writing—from Genre to Critical Practice,” although written in 1992 , still offers a useful account of life writing’s history as a term, and is still a timely reminder to examine constantly the often-buried theoretical assumptions defining and confining it. After noting that because “life writing” was in use before “biography” or “autobiography,” it “has always been the more inclusive term,” Kadar supplies a taxonomy in the form of a progressive history. Until the 1970s, “life writing” referred to “a particular branch of textual criticism” that subjected some biographies and autobiographies, and a scattering of letters and diaries, to the same literary-critical scrutiny commonly focused upon poetry, drama, or fiction. Kadar cites Donald J. Winslow’s Life-Writing as a locus for this understanding. 1 The problem lurking here is what Kadar elsewhere refers to as “the New Critical wolf”: theoretical assumptions that are “androcentric” and privilege notions of “objective truth and narrative regularity.” Clearly wanting to label this as residual, she turns to the then-current “more broadened version” of life writing. Its champions are primarily, though not exclusively, feminist literary critics devoted to “the proliferation, authorization, and recuperation” of autobiographical texts written by “literary,” but also “ordinary,” men and women. While the “ordinary” allows “personal narratives, oral narratives and life testimonies” and even “anthropological life histories” to enter the realm of life writing, this now-dominant understanding is nevertheless problematic, because it still tends to uncritically draw such binary distinctions as fiction/autobiography, literary/non-literary non-fiction, and even male/female. Heavily influenced by postmoderism, Kadar proposes a third, emergent vision of life writing that moves beyond a desire for fixity and canonization—“with laws and law-making”—by embracing a dynamic, constantly questioning methodology: “From Genre to Critical Practice.” 2

This approach gestures toward a focus upon intersectionality in “unofficial” writing—Kadar’s example is Frederick Douglass—and toward an expansive yet politically engaged life-writing practice that can “appreciate the canon, revise it where it sees fit, and forget it where it also sees fit.” 3 The same approach should be adopted toward such terms as “the autobiographical” or “life writing itself.” After describing life writing “as a continuum that spreads unevenly and in combined forms from the so-called least fictive narration to the most fictive,” she offers her own “working definition.” Life-writing texts “are written by an author who does not continuously write about someone else”—note how biography has at best been relegated to the fringes of the realm—and “who also does not pretend to be absent from the [black, brown, or white] text himself/herself.” Neither an archive nor a taxonomy of texts, life writing employs “an imperfect and always evolving hermeneutic,” where “classical, traditional, or postmodern” approaches coexist, rather than always being set against each other. 4

Kadar’s early-1990s assessment and prophecy will serve here as loose organizational principles for describing how the move “from Genre to Critical Practice” in the ensuing years has proved to be an astonishing, though contested, unfolding of life writing as a term encompassing more initiatives by diverse communities in many locations and media that even the far-sighted Marlene Kadar could have anticipated. Even so, her insistence that life-writing critics and theorists must continue to “resist and reverse the literary and political consequences” produced by impulses toward “ʻdepersonalization’ and unrelenting ʻabstraction’” still stands. 5

From Biography to Autobiography to Life Writing

Kadar’s support for life writing as the umbrella term came in the wake of an energetic focus on autobiography as the most critically and theoretically stimulating life-narrative genre. The academic journal Biography had begun appearing in 1978 , but for all its claims to be An Interdisciplinary Quarterly , it was assumed to be largely devoted to traditional biography criticism and theory. In 1980 , James Olney noted the “shift of attention from bios to autos —from the life to the self,” which he credited with “opening things up and turning them in a philosophical, psychological and literary direction.” 6 Biography scholars would have begged to differ. Discussions of psychology, with an emphasis on psychoanalysis, and of the aesthetics of literary biography, with special attention paid to affinities with the novel, had been part of biography’s critical and theoretical environment for a century. 7 Olney however was not just arguing for autobiography’s legitimacy, but for the primacy of autos within literature itself—a key claim of his landmark monograph Metaphors of Self . 8 Olney was a convener as well as a critic and theorist. Ricia Chansky identifies the “International Symposium on Autobiography and Autobiography Studies” Olney held in 1985 as “the moment when contemporary auto/biography studies emerged as a formal discipline within the academy”—not least because it led to the creation of a newsletter that soon became the journal a/b: Auto/Biography Studies . Although the slashes in the title—credited to Timothy Dow Adams—suggested that a/b would not privilege “self-life writing over life writing,” the variety and sheer number of critical and theoretical works devoted to autobiography in the ensuing years made it clear that for many, it was the more interesting genre. 9

Institutionalization and professional assertion soon followed. Sidonie Smith recalls “those heady days” of creating archives and bibliographies, but also of “writing against the grain, writing counterhistories, writing beyond conventional plots and tropes.” 10 As Olney had predicted, autobiography became a flash point for critical and theoretical writing in women’s studies—a trend heavily influencing Kadar’s thoughts on life writing, and canonized in Sidonie Smith and Julia Watson’s Women, Autobiography, Theory: A Reader , whose introduction is still the most detailed account of how women critics and theorists from the 1970s to the late 1990s drew upon the most compelling feminist, post-structuralist, cultural, and political writing in their encounters with autobiographical texts. 11

This interest in autobiography—with or without the slash—produced an entire generation of influential writers. Because of their general eminence, Paul de Man’s and Roland Barthes’s comments on and experiments with autobiography were closely examined, but other theorists made autobiography their central attention. 12 Philippe Lejeune’s profoundly influential essay “The Autobiographical Pact” complemented Olney’s book on metaphors of self, and so did Paul John Eakin’s volumes Fictions of Autobiography and Touching the World as arguments for the genre’s legitimacy within literary studies. 13 A host of important books, collections, and anthologies soon followed, many with a strongly feminist approach. Sidonie Smith’s A Poetics of Women’s Autobiography was an important intervention into literary aesthetics, and Smith and Watson’s edited collection De/Colonizing the Subject forged important links between autobiography and feminist and postcolonial theory. 14 Many other feminist critics and theorists in Europe and North America in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s directed their attention as writers and editors to autobiography, among them collection editors Shari Benstock and Bella Brodsky and Celeste Schenk; monograph writers Elizabeth Bruss, Leigh Gilmore, Caroline Heilbrun, Françoise Lionnet, Nancy K. Miller, and Liz Stanley; and essayists Susan Stanford Friedman and Mary G. Mason. Following in the tradition of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own , other feminist literary and cultural historians sought out forgotten or yet-to-be-discovered women autobiographers—Patricia Meyer Spacks for the 18th century ; Mary Jean Corbett, Regenia Gagnier, Linda H. Peterson, and Valerie Sanders for the long 19th century ; Estelle C. Jelinek from the time of antiquity; and collection editor Domna C. Stanton from the medieval period to the 20th century . 15

Often viewed through the lens of literary and cultural theory, autobiography therefore became the most-discussed life-writing genre in the 1980s, and has largely remained so ever since. But from the time of Kadar’s Essays on Life Writing , the term “life writing” became increasingly employed as the umbrella term for representing the lives of others, or of one’s self. The key intervention here was Margaretta Jolly’s landmark two-volume Encyclopedia of Life Writing . Published in 2001 , the title term encompasses Autobiographical and Biographical Forms , and through her contributors, Jolly accounts in 1,090 large double-column pages not just for the genres that could be considered life writing, but for life-writing practices in a host of world regions and historical periods. She emphasizes her subject’s interdisciplinary nature. Although the “writing of lives is an ancient and ubiquitous practice,” and the term “life writing” can in England be traced back to the late 17th or early 18th century , it has only gained “wide academic acceptance since the 1980s.” While noting that “the study of autobiography is the most-long-standing and sophisticated branch of analysis in the field”—a claim that biography scholars would dispute, at least with regard to duration—Jolly grants Kadar’s wish to expand beyond the literary by including entries grounded in “anthropology, sociology, psychology, history, theology, cultural studies, and even the biological sciences,” and in forms of life narrative “outside of the written form, including testimony, artifacts, reminiscence, personal narrative, visual arts, photography, film, oral history, and so forth.” 16

The Encyclopedia also provides “international and historical perspective through accounts of life writing traditions and trends from around the world, from Classical times to the present,” and covers “popular and everyday genres and contexts—from celebrity and royal biography to working-class autobiography, letter writing, interviews, and gossip”—a continuation of work, epitomized by Smith and Watson’s Getting a Life , that pays close attention to how “ordinary” lives are produced in a variety of public and institutional settings. 17 Like Kadar, Jolly notes the “crucial influence” of “Women’s Studies, Cultural Studies, African-American, and Post-Colonial Studies” upon autobiography studies’ emergence in the 1980s, and she also observes that many contributors use the term “auto/biography” to point toward a more capacious sense of the field. But also like Kadar, in an “effort to balance the emphasis on autobiography,” Jolly chooses “life writing” as her preferred term, because it can more easily accommodate “many aspects of this wide-ranging field, not to mention regions of the world, where life-writing scholarship remains in its infancy, or has yet to emerge.” 18 This ambitious and expansive reference work anticipates most of the ensuing developments in life writing.

In the same year appeared the first edition of Smith and Watson’s Reading Autobiography . Although retaining autobiography as the covering term—describing it as “a particular generic practice” that “became definitive for life writing in the West”—they share Jolly’s commitment to generic, historic, and geographical inclusivity, and take a highly detailed approach to clarifying terminology. 19 Echoing Kadar, they note that autobiography “has been vigorously challenged in the wake of postmodern and postcolonial critiques of the Enlightenment subject”—an entity whose “politics is one of exclusion.” In response, they grant that “life writing” is a more expansive term, because it can refer to “writing that takes a life, one’s own or another’s, as its subject,” whether “biographical, novelistic, historical, or explicitly self-referential.” But, always sensitive to new developments and dimensions, Smith and Watson suggest that “life narrative” is even more capacious, because it refers to “autobiographical [and presumably biographical] acts of any sort.” 20 With the added perspective of nine years, and then eighteen years for their second edition, Smith and Watson update Kadar’s 1992 account of the profound impact that feminist, postmodernist, and postcolonial theory have had upon life writing—although they still direct readers to their own Women, Autobiography, Theory for a more detailed “overview of representative theories and work up to the late 1990s.” 21 Their main point is that the theoretical work Kadar called for has been taking place: “the challenges posed by postmodernism’s deconstruction of any solid ground of selfhood and truth outside of discourse,” when coupled with “postcolonial theory’s troubling of established hierarchies of authority, tradition, and influence,” led life-writing critics and theorists to examine “generic instability, regimes of truth telling, referentiality, relationality, and embodiment,” which not only undermined “the earlier critical period’s understanding of canonical autobiography” but also “expanded the range of life writing and the kinds of stories critics may engage in rethinking the field of life narrative.” 22