An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Orthop

- v.50(6); Nov-Dec 2016

What is plagiarism and how to avoid it?

Ish kumar dhammi.

Department of Orthopaedics, UCMS and Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, New Delhi, India

Rehan Ul Haq

Writing a manuscript is an art. Any clinician or an academician, has a hidden desire to publish his/her work in an indexed journal. Writing has been made mandatory for promotions in certain departments, so the clinicians are more inclined to publish. Often, we note that we (Indian Journal of Orthopaedics) receive more articles from China, Turkey, and South Korea (abroad) instead of from our own country though the journal is an official publication of Indian Orthopaedic Association. Therefore, we have decided to encourage more and more publications, especially from our own country. For that reason, we have decided to educate our members by publishing an editorial on “How to write a paper?,” which is likely to be published soon. In one of our last editorials, we discussed indexing. In this issue, we will be discussing the plagiarism. In forthcoming issues, we are planning to discuss “Ethics in publication,” How to write Introduction, Materials and Methods, Results, Discussion, Referencing, Title, Abstract, and Keywords, and then how to write case report which is acceptable. The editorial team tries to help out our readers, so that their hidden instinct of writing their own work could be made true.

D EFINITION OF P LAGIARISM

Plagiarism is derived from Latin word “ plagiarius ” which means “kidnapper,” who abducts the child. 1 The word plagiarism entered the Oxford English dictionary in 1621. Plagiarism has been defined by the Encyclopedia Britannica as “the act of taking the writings of another person and passing them off as ones own.” 2 It is an act of forgery, piracy, and fraud and is stated to be a serious crime of academia. 3 It is also a violation of copyright laws. Honesty in scientific practice and in publication is necessary. The World Association of Medical Editors 4 (WAME) defines plagiarism as “… the use of others’ published and unpublished ideas or words (or other intellectual property) without attribution or permission and presenting them as new and original rather than derived from an existing source.”

In 1999, the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) 5 , 6 defined plagiarism as “Plagiarism ranges from the unreferenced use of others’ published and unpublished ideas including research grant applications to submission under new authorship of a complex paper, sometimes in a different language. It may occur at any stage of planning, research, writing or publication; it applies to print and electronic versions.”

F ORMS OF P LAGIARISM

- Verbatim plagiarism: When one submits someone else's words verbatim in his/her own name without even acknowledging him publically. Copy and paste from a published article without referencing is a common form of verbatim plagiarism. Most commonly, it is seen in introduction and discussion part of manuscript 2 , 7

- Mosaic plagiarism: In this type of plagiarism each word is not copied but it involves mixing ones own words in someone else's ideas and opinions. This is copying and pasting in patchy manner 2

- Paraphrasing: If one rewrites any part/paragraph of manuscript in his/her own words it is called paraphrasing. Paraphrasing is a restatement in your own words, of someone else's ideas. Changing a few words of the original sentences does not make it your writing. Just changing words cannot make it the property of borrower; hence, this should be properly referenced. If it is not referenced, it will amount to plagiarism

- Duplicate publication: When an author submits identical or almost identical manuscript (same data, results, and discussion) to two different journals, it is considered as duplicate (redundant) publication. 9 As per COPE guidelines, this is an offense and editor can take an action as per the COPE flowchart

- Augmented publication: If the author adds additional data to his/her previously published work and changes title, modifies aim of the study, and recalculates results, it amounts to augmented publication. Plagiarism detection software usually do not pick it because it is not same by verbatim. This self plagiarism is as such technical plagiarism and is not considered with same strictness as plagiarism. The editor may consider it for publication in the following three situations: If author refers to his/her previous work; if ’methods’ cannot be written in any other form; and if author clearly states that new manuscript contains data from previous publication 10

- Segmented publication: Also called “Salami-Sliced” publication. In this case, two or more papers are derived from the same experimental/research/original work. Salami-sliced papers are difficult to detect and usually are pointed out by reviewers or readers. The decision regarding such manuscript is again on editor's shoulder. The author must be asked to refer to his/her previously published work and explain reasonably the connection of the segmented paper to his/her previously published work

- Text recycling: If the author uses large portions of his/her own already published text in his/her new manuscript, it is called text recycling. It can be detected by plagiarism software. It can be handled as per the COPE guidelines.

- Cyber plagiarism: “Copying or downloading in part or in their entirety articles or research papers and ideas from the internet and not giving proper attribution is unethical and falls in the range of cyber plagiarism” 2

- Image plagiarism: Using an image or video without receiving proper permission or providing appropriate citation is plagiarism. 7 “Images can be tampered on support findings, promote a specific technique over another to strengthen the correctness of poorly visualized findings, remove the defects of an image and to misrepresent an image from what it really is”? 11

H OW TO D ETECT P LAGIARISM ?

It is generally difficult to detect plagiarism, but information technology has made available few websites which can detect/catch plagiarism. Few of them are www.ithentical.com , www.turnitin.com , www.plagiarism.org , etc. 12

Besides this, learned and watchful reviewers and readers can detect it due to his/her familiarity with published material in his/her area of interest.

H OW TO A VOID P LAGIARISM ?

Practice the ethical writing honestly. Keep honesty in all scientific writings. Crediting all the original sources. When you fail to cite your sources or when you cite them inadequately, you commit plagiarism, an offense that is taken extremely seriously in academic world and is a misconduct. Some simple dos and don’ts 5 are outlined in Table 1 .

Dos and don’ts of plagiarism

In the following situation, permission is required to use published work from publisher to avoid plagiarism. 8

- Directly quoting significant portion of a published work. How much text may be used without approaching publisher for permission is not specified. The best approach is whenever in doubt, ask for permission

- Reproducing a table

- Reproducing a figure/image.

H OW TO D EAL W ITH P LAGIARISM

Plagiarism is considered academic dishonesty and breach of ethics. Plagiarism is not in itself a crime but can constitute copyright infringement. 7 In academia, it is a serious ethical offense. Plagiarism is not punished by law but rather by institutions. Professional associations, educational institutions, and publishing companies can pose penalties, suspensions, and even expulsions of authors. 7

As per the COPE guidelines, “If editors suspect misconduct by authors, reviewer's editorial staff or other editors then they have a duty to take action. This duty extends to both published and unpublished papers. Editors first see a response from those accused. If the editors are not satisfied with the response, they should ask the employers of the authors, reviewers, or editors or some other appropriate body to investigate and take appropriate action.” 6

If the editor is satisfied that the act of plagiarism has taken place, minimum he should do is “reject” the manuscript if it is in different stage of editorial process and “retract” if it is already published.

To conclude, we must increase awareness about plagiarism and ethical issues among our scientists and authors. We must be honest in our work and should not violate copyright law. There should be serious steps against authors, which should bring disrespect to author and even loss of his academic position.

We will end it by quote of Albert Einstein “Many people say that it is the intellect which makes a great scientist, they are wrong, it is the character.”

R EFERENCES

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Factors influencing plagiarism in higher education: A comparison of German and Slovene students

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Personnel and Education, Faculty of Organizational Sciences, University of Maribor, Kranj, Slovenia

Roles Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, University of Maribor, Maribor, Slovenia; School of Electronic and Information Engineering, Beihang University, Beijing, China

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Economics and Law, Frankfurt University of Applied Sciences, Frankfurt, Germany

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft

Affiliation Department of Methodology, Faculty of Organizational Sciences, University of Maribor, Kranj, Slovenia

Roles Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – original draft

Roles Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

- Eva Jereb,

- Matjaž Perc,

- Barbara Lämmlein,

- Janja Jerebic,

- Marko Urh,

- Iztok Podbregar,

- Polona Šprajc

- Published: August 10, 2018

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252

- Reader Comments

Over the past decades, plagiarism has been classified as a multi-layer phenomenon of dishonesty that occurs in higher education. A number of research papers have identified a host of factors such as gender, socialisation, efficiency gain, motivation for study, methodological uncertainties or easy access to electronic information via the Internet and new technologies, as reasons driving plagiarism. The paper at hand examines whether such factors are still effective and if there are any differences between German and Slovene students’ factors influencing plagiarism. A quantitative paper-and-pencil survey was carried out in Germany and Slovenia in 2017/2018 academic year, with a sample of 485 students from higher education institutions. The major findings of this research reveal that easy access to information-communication technologies and the Web is the main reason driving plagiarism. In that regard, there are no significant differences between German and Slovene students in terms of personal factors such as gender, motivation for study, and socialisation. In this sense, digitalisation and the Web outrank national borders.

Citation: Jereb E, Perc M, Lämmlein B, Jerebic J, Urh M, Podbregar I, et al. (2018) Factors influencing plagiarism in higher education: A comparison of German and Slovene students. PLoS ONE 13(8): e0202252. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252

Editor: Andreas Wedrich, Medizinische Universitat Graz, AUSTRIA

Received: May 21, 2018; Accepted: July 6, 2018; Published: August 10, 2018

Copyright: © 2018 Jereb et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: MP was supported by the Slovenian Research Agency (Grant Nos. J1-7009 and P5-0027), http://www.arrs.gov.si/ . The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Many of those who teach in higher education have encountered the phenomenon of plagiarism as a form of dishonesty in the classroom. According to the Oxford English Dictionary online 2017, the term plagiarism is defined as ‘the practice of taking someone else's work or ideas and passing them off as one's own’. Perrin, Larkham and Culwin define plagiarism as the use of an author's words, ideas, reflections and thoughts without proper acknowledgment of the author [ 1 – 3 ]. Koul et al. define plagiarism as a form of cheating and theft since in cases of plagiarism one person takes credit for another person’s intellectual work [ 4 ]. According to Fishman, ‘Plagiarism occurs when someone: 1) uses words, ideas, or work products; 2) attributable to another identifiable person or source; 3) without attributing the work to the source from which it was obtained; 4) in a situation in which there is a legitimate expectation of original authorship; 5) in order to obtain some benefit, credit, or gain which need not be monetary’ [ 5 ]. But why do students use someone else's words or ideas and pass them on as their own? Which factors influence this behaviour? That is the main focus of our research, to discover the factors influencing plagiarism and see if there are any differences between German and Slovene students.

Koul et al. pointed out that particular circumstances or events should be considered in the definition of plagiarism since plagiarism may vary across cultures and societies [ 4 ]. Hall has described Eastern cultures (the Middle East, Asia, Africa, South America) and Western cultures (North America and much of Europe) using the idea of ‘context’, which refers to the framework, background, and surrounding circumstances in which an event takes place [ 6 ]. Western societies are generally ‘low context’ societies. In other words, people in Western societies play by external rules (e.g., honour codes against plagiarism), and decisions are based on logic, facts, and directness. Eastern societies are generally ‘high context’ societies, meaning that people in Eastern societies put strong emphasis on relational concerns, and decisions are based on personal relationships. Nisbett et al. have suggested that differences between Westerners and Easterners may arise from people being socialised into different worldviews, cognitive processes and habits of mind [ 7 ]. In Germany, there has been ongoing reflection on academic plagiarism and other dishonest research practices since the late 19th century [ 8 ]. However, according to Ruiperez and Garcia-Cabrero, in Germany, 2011 became a landmark year with the appearance of an extensive public debate about plagiarism—brought back into the limelight because of an investigation into the incumbent German Defence Minister’s doctoral thesis [ 9 ]. Aside from the numerous cases of plagiarism detected in academic work since 2011, several initiatives have enriched the debate on academic plagiarism. For example, the development of a consolidated cooperative textual research methodology using a specific Wiki called ‘VroniPlag’ has made Germany one of the most advanced European countries in terms of combating these practices. Similar to Germany, Slovenia has also paid increased attention to plagiarism in recent years. The debate about plagiarism became public after it was discovered that certain Slovene politicians had resorted to academic plagiarism. Today, universities in Slovenia use a variety of tools (Turnitin, plagiarism plug-ins for Moodle, plagiarisma.net, etc.) in order to detect plagiarism. The focus of this research is to investigate the factors influencing plagiarism and if there are any differences between Slovene and German students’ factors influencing plagiarising. The research questions (RQ) of the study were divided into three groups:

- RQ group 1: Which factors influence plagiarism in higher education?

- RQ group 2: Are there any differences between male and female students regarding factors influencing plagiarism? Are the factors influencing plagiarism connected with specific areas of study (technical sciences, social sciences, natural sciences)?

- RQ group 3: Does the students’ motivation affect their factors influencing plagiarism? Are there any differences between male and female students regarding this?

In addition, for all three research question groups, we also wanted to know if there were any differences between the German and Slovene students.

Theoretical background

Plagiarism is a highly complex phenomenon and, as such, it is likely that there is no single explanation for why individuals engage in plagiarist behaviours [ 10 ]. The situation is often complex and multi-dimensional, with no simple cause-and-effect link [ 11 ].

McCabe et al. noted that individual factors (e.g. gender, average grade, work ethic, self-esteem), institutional factors (e.g., faculty response to cheating, sanction threats, honour codes) and contextual factors (e.g., peer cheating behaviours, peer disapproval of cheating behaviours, perceived severity of penalties for cheating) influence cheating behaviour [ 12 ]. Giluk and Postlethwaite also related individual characteristics and situational factors to cheating—individual characteristics such as gender, age, ability, personality, and extracurricular involvement; and situational factors such as honour codes, penalties, and risk of detection [ 13 ]. The study of Jereb et al. also revealed that specific individual characteristics pertaining to men and women influence plagiarism [ 14 ]. Newstead et al. suggested that gender differences (plagiarism is more frequent among boys), age differences (plagiarism is more frequent among younger students), and academic performance differences (plagiarism is more frequent among lower performers) are specific factors for plagiarism [ 15 ]. Gerdeman stated that the following five student characteristic variables are frequently related to the incidence of dishonest behaviour: academic achievement, age, social activities, study major, and gender [ 16 ].

One of the factors influencing plagiarism could be that students do not have a clear understanding of what constitutes plagiarism and how it can be avoided [ 17 , 18 ]. According to Hansen, students don’t fully understand what constitutes plagiarism [ 19 ]. Park states genuine lack of understanding as one of the reasons for plagiarism. Some students plagiarise unintentionally, when they are not familiar with proper ways of quoting, paraphrasing, citing and referencing and/or when they are unclear about the meaning of ‘common knowledge’ and the expression ‘in their own words’ [ 11 ].

Furthermore, it is important to remember that, in our current day and age, information is easily accessed through new technologies. In addition, as Koul et al. have stated, the belief that we as people have greater ownership of information than we have paid for may influence attitudes towards plagiarism [ 4 ]. Many other authors have also stated that the Internet has increased the potential for plagiarism, since information is easily accessed through new technologies [ 14 , 20 , 21 , 22 ]. Indeed, the Internet grants easy access to an enormous amount of knowledge and learning materials. This provides an opportunity for students to easily cut, paste, download and plagiarise information [ 21 , 23 ]. Online resources are available 24/7 and enable a flood of information, which is also constantly updated. Given students' ease of access to both digital information and sophisticated digital technologies, several researchers have noted that students may be more likely to ignore academic ethics and to engage in plagiarism than would otherwise be the case [ 24 ].

In a study of the level of plagiarism in higher education, Tayraukham found that students with performance goals were more likely to indulge in plagiarism behaviours than students who wanted to achieve mastery of a particular subject [ 25 ]. Most of the students plagiarised in order to provide the right responses to study questions, with the ultimate goal of getting higher grades—rather than gaining expertise in their subjects of study. Anderman and Midgley observed that a relatively higher performance-oriented classroom climate increases cheating behaviour; while a higher mastery-oriented classroom climate decreases cheating behaviour [ 26 ]. Park also claimed that one of the reasons that students plagiarise is efficiency gain, that is, that students plagiarise in order to get a better grade and save time [ 11 ]. Songsriwittaya et al. stated that what motivates students to plagiarise is the goal of getting good grades and comparing their success with that of their peers [ 27 ]. The study of Ramzan et al. also revealed that the societal and family pressures of getting higher grades influence plagiarism [ 21 ]. Such pressures sometimes push students to indulge in unfair means such as plagiarism as a shortcut to performing better in exams or producing a certain number of publications. Engler et al. and Hard et al. tended to agree with this idea, stating that plagiarism arises out of social norms and peer relationships [ 28 , 29 ]. Park also stated that there are many calls on students’ time, including peer pressure for maintaining an active social life, commitment to college sports and performance activities, family responsibilities, and pressure to complete multiple work assignments in short amounts of time [ 11 ]. Šprajc et al. agreed that students are under an enormous amount of pressure from family, peers, and instructors, to compete for scholarships, admissions, and, of course, places in the job market [ 30 ]. This affects students’ time management and can lead to plagiarism. In addition to time pressures, Franklin-Stokes and Newstead found another six major reasons given by students to explain cheating behaviours: the desire to help a friend, a fear of failure, laziness, extenuating circumstances, the possibility of reaping a monetary reward, and because ‘everybody does it’ [ 31 ].

Another common reason for plagiarism is the poor preparation of lecture notes, which can lead to the inadequate referencing of texts [ 32 ]. Šprajc et al. found out that too many assignments given within a short time frame pushes students to plagiarise [ 30 ]. Poor explanations, bad teaching, and dissatisfaction with course content can also drive students to plagiarise. Park exposed students’ attitudes towards teachers and classes [ 11 ]. Some students cheat because they have negative attitudes towards assignments and tasks that teachers believe to have meaning but that they don’t [ 33 ]. Cheating tends to be more common in classes where the subject matter seems unimportant or uninteresting to students, or where the teacher seemed disinterested or permissive [ 16 ].

Park mentioned students’ academic skills (researching and writing skills, knowing how to cite, etc.) as another reason for plagiarism [ 11 ]. New students and international students whose first language is not English need to transition to the research culture by understanding the necessity of doing research, and the practice and skills required to do so, in order to avoid unintentional plagiarism [ 21 ]. According to Park to some students, plagiarism is a tangible way of showing dissent and expressing a lack of respect for authority [ 11 ]. Some students deny to themselves that they are cheating or find ways of legitimising their behaviour by passing the blame on to others. Other factors influencing plagiarising are temptation and opportunity. It is both easier and more tempting for students to plagiarise since information has become readily accessible with the Internet and Web search tools, making it faster and easier to find information and copy it. In addition, some people believe that since the Internet is free for all and a public domain, copying from the Internet requires no citation or acknowledgement of the source [ 34 ]. To some students, the benefits of plagiarising outweigh the risks, particularly if they think there is little or no chance of getting caught and there is little or no punishment if they are indeed caught [ 35 ].

One of the factors influencing plagiarism could be also higher institutions’ attitudes towards plagiarism, that is, whether they have clear policies regarding plagiarism and its consequences or not. The effective communication of policies, increased student awareness of penalties, and enforcement of these penalties tend to reduce dishonest behaviour [ 36 ]. Ramzan et al. [ 21 ] mentioned the research of Razera et al., who found that Swedish students and teachers need training to understand and avoid plagiarism [ 37 ]. In order to deal with plagiarism, teachers want and need a clear set of policies regarding detection tools, and extensive training in the use of detection software and systems. According to Ramzan et al., Dawson and Overfield determined that students are aware that plagiarism is bad but that they are not clear on what constitutes plagiarism and how to avoid it [ 21 , 38 ]. In Dawson and Overfield’s study, students required teachers to also observe the rules set up to avoid plagiarism and be consistently kept aware of plagiarism—in order to enforce the university’s resolve to control this academic misconduct.

According to this literature review and our experiences in higher education teaching, we determined that the following factors influence plagiarism: students’ individual factors, information-communication technologies (ICT) and the Web, regulation, students’ academic skills, teaching factors, different forms of pressure, student pride, and other reasons. The statements used in the instrument we developed, and the results of our research are presented in the following chapters.

Participants

The paper-and-pencil survey was carried out in the 2017/18 academic year at the University of Maribor in Slovenia and at the Frankfurt University of Applied Sciences in Germany. Students were verbally informed of the nature of the research and invited to freely participate. They were assured of anonymity. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee for Research in Organizational Sciences at Faculty of Organizational Sciences University of Maribor.

A sample of 191 students from Slovenia (SLO) (99 males (51.8%) and 92 (48.2%) females) and 294 students from Germany (GER) (115 males (39.1%) and 171 (58.2%) females) participated in this study. Slovene students’ ages ranged from 19 to 36 years, with a mean of 21 years and 1 months ( M = 21 . 12 and SD = 1 . 770 ) and German students’ ages ranged from 18 to 40 years, with a mean of 22 years and 10 months ( M = 22 . 84 and SD = 3 . 406 ). About half (49.2%) of the Slovene participants were social sciences students, 34.9% were technical sciences students, and 15.9% were natural sciences students. More than half (58.5%) of the German participants were social sciences students, 32% were technical sciences students and 2% were natural sciences students. More than half of the Slovene students (53.4%) attended blended learning, and 46.6% attended classic learning. The majority of German students (87.8%) attended classic learning, and 6.8% attended blended learning. More than half of the Slovene students (61.6%) were working at the time of the study, and 39.8% of all participants had scholarships. In addition, in Germany, more than half the students (65.0%) were working at the time of the study, but only 10.2% of all the German participants had scholarships. More than two thirds (68.9%) of the Slovene students were highly motivated for study and 31.1% less so; 32.6% of the students spend 2 or fewer hours per day on the Internet, 41.6% spend between 2 and 5 hours on the Internet, and 25.8% spend 5 or more hours on the Internet per day. Also, more than two thirds (73.1%) of the German students were highly motivated for study and 23.8% less so; 33.3% of the students spend 2 or fewer hours per day on the Internet, 32.3% spend between 2 and 5 hours on the Internet, and 27.9% spend 5 or more hours on the Internet per day. The general data can be seen in S1 Table .

The questionnaire contained closed questions referring to: (i) general/individual data (gender, age, area of study, method of study, working status, scholarship, motivation for study, average time spent on the internet), and factors influencing plagiarism (ii) ICT and Web, (iii) regulation, (iv) academic skills, (v) teaching factors, (vi) pressure, (vii) pride, (viii) other reasons. The items in the groups (ii) to (viii) used a 5-point Likert scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5), with larger values indicating stronger orientation.

The statements used in the survey were as follows:

- 1.1 It is easy for me to copy/paste due to contemporary technology

- 1.2 I do not know how to cite electronic information

- 1.3 It is hard for me to keep track of information sources on the web

- 1.4 I can easily access research material using the Internet

- 1.5 Easy access to new technologies

- 1.6 I can easily translate information from other languages

- 1.7 I can easily combine information from multiple sources

- 1.8 It is easy to share documents, information, data

- 2.1 There is no teacher control on plagiarism

- 2.2 There is no faculty regulation against plagiarism

- 2.3 There is no university regulation against plagiarism

- 2.4 There are no penalties

- 2.5 There are no honour codes relating to plagiarism

- 2.6 There are no electronic systems of control

- 2.7 There is no systematic tracking of violators

- 2.8 I will not get caught

- 2.9 I am not aware of penalties

- 2.10 I do not understand the consequences

- 2.11 The penalties are minor

- 2.12 The gains are higher than the losses

- 3.1 I run out of time

- 3.2 I am unable to cope with the workload

- 3.3 I do not know how to cite

- 3.4 I do not know how to find research materials

- 3.5 I do not know how to research

- 3.6 My reading comprehension skills are weak

- 3.7 My writing skills are weak

- 3.8 I sometimes have difficulty expressing my own ideas

- 4.1 The tasks are too difficult

- 4.2 Poor explanation—bad teaching

- 4.3 Too many assignments in a short amount of time

- 4.4 Plagiarism is not explained

- 4.5 I am not satisfied with course content

- 4.6 Teachers do not care

- 4.7 Teachers do not read students' assignments

- 5.1 Family pressure

- 5.2 Peer pressure

- 5.3 Under stress

- 5.4 Faculty pressure

- 5.5 Money pressure

- 5.6 Afraid to fail

- 5.7 Job pressure

- 6.1 I do not want to look stupid in front of peers

- 6.2 I do not want to look stupid in front of my professor

- 6.3 I do not want to embarrass my family

- 6.4 I do not want to embarrass myself

- 6.5 I focus on how my competences will be judged relative to others

- 6.6 I am focused on learning according to self-set standards

- 6.7 I fear asking for help

- 6.8 My fear of performing poorly motivates me to plagiarise

- 6.9 Assigned academic work will not help me personally/professionally

- 7.1 I do not want to work hard

- 7.2 I do not want to learn anything, just pass

- 7.3 My work is not good enough

- 7.4 It is easier to plagiarise than to work

- 7.5 To get a better/higher mark (score)

All statistical tests were performed with SPSS at the significance level of 0.05. Parametric tests (Independent–Samples t-Test and One-Way ANOVA) were selected for normal and near-normal distributions of the responses. Nonparametric tests (Mann-Whitney Test, Kruskal-Wallis Test, Friedman’s ANOVA) were used for significantly non-normal distributions. Chi-Square Test was used to investigate the independence between variables.

The average values for the groups (and standard deviations) of the responses referring to the factors influencing plagiarism can be seen in Table 1 (descriptive statistics for all statements can be seen in S2 Table ), shown separately for Slovene and German students. An Independent Samples t-test was conducted to obtain the average values of the responses, and thus evaluate for which statements these differed significantly between the Slovene and German students.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.t001

According to the Friedman’s ANOVA (see Table 2 ), the Slovene students’ factors influencing plagiarism can be formed into four homogeneous subsets, where in each subset, the distributions of the average values for the responses are not significantly different. At the top of the list is the existence of ICT and the Web (group 1). The second subset consists of teaching factors (group 4). The third subset is composed of academic skills, other reasons, and pride, in order from highest to lowest (groups 3, 7 and 6). The fourth subset is composed of other reasons, pride, pressure, and regulation, respectively (groups 7, 6, 5 and 2).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.t002

For the Slovene students, ICT and the Web were detected as the dominant factors influencing plagiarism and, as such, we investigated them in greater detail. A Friedman Test ( Chi-Square = 7.180, p = .066) confirmed that the distributions of the responses to the statements 1.1, 1.4, 1.5 and 1.8—those with the highest sample means—are not significantly different. Consequently, the average values (means) of the responses to the statements 1.1, 1.4, 1.5 and 1.8 are not significantly different. The average values of the responses for all the other statements (1.7, 1.6, 1.2, and 1.3 listed in the descending order of sample means) are significantly lower. A Mann-Whitney Test showed that there is no statistically significant difference between the distributions of the responses in the group of ICT and Web reasons considering gender (male, female) and motivation for study (lower, higher). For statement 1.2, a Kruskal-Wallis Test ( Chi-Square = 7.466, p = .024) confirmed that there are different distributions for the responses when the area of study is considered (technical sciences, social sciences, natural sciences).

According to the Friedman’s ANOVA (see Table 3 ), the German students’ factors influencing plagiarism can be formed into five homogeneous subsets, where in each subset, the distributions of the average values for the responses are not significantly different. At the top of the list is the existence of ICT and the Web (group 1). The second subset is composed of pressure and pride, in order from highest to lowest (groups 5 and 6). The third subset consists of pride, teaching factors and other reasons, respectively (groups 6, 4 and 7). The fourth subset is composed of teaching factors, other reasons and academic skills, in order from highest to lowest (groups 4, 7 and 3). Finally, the last subset consists of regulation (group 2).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.t003

Just like the Slovene students, for the German students ICT and the Web were detected as the dominant factors influencing plagiarism. That the distributions of the responses to the statements 1.4, 1.5 and 1.8—those with the highest sample means—are not significantly different was confirmed by Friedman Test ( Chi-Square = 5.815, p = .055). Consequently, the average values (means) of the responses to the statements 1.4, 1.5 and 1.8 are not significantly different. The average values of the responses for all the other statements (1.1, 1.7, 1.6, 1.2, and 1.3 listed in the descending order of sample means) are significantly lower. A Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Tests also confirmed that the distributions of the responses to the statements 1.6 and 1.7 are not statistically significantly different ( Z = -0.430, p = .667). The same holds for statements 1.2 and 1.3 ( Z = -0.407, p = .684). A Mann-Whitney Test showed that there is no statistically significant difference between the distributions of the responses in the group of ICT and Web reasons considering gender (male, female), area of study (technical and social sciences (students of natural sciences were omitted due to the small sample size)) and motivation for study.

ICT and Web reasons were detected as the dominant factors influencing plagiarism for Slovene and German students. As can be seen in Table 1 , there are significant differences ( t = 4.177, p = .000 ) between the Slovene and German students regarding this factor. It seems that the Slovene students ( M = 3.69, SD = 0.56) attribute greater importance to the ICT and Web reasons than the German students ( M = 3.47, SD = 0.55). There are also significant differences ( t = 5.137, p = .000 ) between the Slovene and German students regarding regulation. It seems that the Slovene students ( M = 2.35, SD = 0.63) attribute greater importance to regulation reasons than the German students ( M = 2.05, SD = 0.61). Both, however, consider this factor to have the lowest impact on plagiarism overall. There are no significant differences ( t = 1.939, p = .053 ) between the Slovene students ( M = 2.56, SD = 0.67) and the German students ( M = 2.44, SD = 0.68) regarding academic skills. The Slovene students ( M = 2.87, SD = 0.68) attribute greater importance to teaching factors than the German students ( M = 2.56, SD = 0.72). The differences are significant ( t = 4.827, p = .000 ) . There are significant differences ( t = -3.522, p = .000 ) between the Slovene and German students regarding pressure, whereas the German students ( M = 2.71, SD = 0.91) attribute greater importance to this reason than the Slovene students ( M = 2.42, SD = 0.86). The same goes for pride. The German students ( M = 2.67, SD = 0.80) attribute greater importance to pride reasons than the Slovene students ( M = 2.43, SD = 0.84). The differences are significant ( t = -3.032, p = .003 ) . There are no significant differences ( t = - 0.836, p = .404 ) between the Slovene students ( M = 2.47, SD = 0.82) and the German students ( M = 2.54, SD = 0.94) regarding other factors influencing plagiarism.

We conducted an Independent Samples t-test to compare the average time (in hours) spent per day on the Internet by the Slovene students with that of the German students. The test was significant, t = -2.064, p = .004. The Slovene students on average spent less time on the Internet ( M = 3.52, SD = 2.23) than the German students ( M = 4.09, SD = 3.72).

The average values of the responses for individual statements according to gender (male, female) and the significances for the t-test of equality of means are shown in S3 Table for the Slovene students and in S4 Table for the German students. The average values of the responses for these statements are significantly different. They are higher for males than for females (except in the case of statement 3.8 for the Slovene students and 4.1 for the German students). Slovene and German male students think that they will not get caught and that the gains are higher than the losses. Both also think that teachers do not read students’ assignments.

The average values of the responses for individual statements according to area of study (technical sciences, social sciences, natural sciences) and the results for ANOVA for the Slovene students are shown in S5 Table . Gabriel's post hoc test was used to confirm the differences between groups. The significant difference between the students of technical sciences and the students of social sciences was confirmed for all statements listed in S5 Table . There were higher average values of responses for the students of technical sciences. The only significant difference between the students of technical sciences and the students of natural sciences was confirmed for statement 5.6 (there were higher average values of responses for the students of technical sciences). No other pairs of group means were significantly different.

The average values of the responses for individual statements according to area of study (technical sciences, social sciences) and the significances for the t-test of equality of means for German students are shown in S6 Table . For German students, only technical and social sciences were considered because of the low number of natural sciences students. The average values of responses for these statements are significantly different. They were higher for the students of technical sciences than for the students of social sciences.

The average values of the responses for individual statements according to the motivation of the students (lower, higher) and the significances for t-Test of equality of means are shown in S7 Table for the Slovene students and in S8 Table for the German students. The average values of the responses for these statements are significantly different. They were higher for students with lower motivation for both groups of students, except in the case of statements 2.1 and 6.6 for Slovene students.

We conducted an Independent Samples t-test to compare the average time (in hours) spent per day on the Internet by groups of low motivated students with groups of highly motivated students. For Slovene students, the test was not significant, t = -1.423, p = .156. For German students, the test was significant, t = 2.298, p = .024. Students with lower motivation for study ( M = 5.24, SD = 4.84) on average spent more time on the Internet than those with higher motivation for study ( M = 3.76, SD = 3.27).

The Chi-Square Test of Independence was used to determine whether there is an association between gender (male, female) and motivation for study (lower, higher). There was a significant association between gender and motivation for the Slovene students ( Chi-Square = 4.499, p = .034). Indeed, it was more likely for females to have a high motivation for study (76.9%) than for males to have a high motivation for study (61.6%). For the German students, the test was not significant ( Chi-Square = 0.731, p = .393).

In this study, we aimed to explore factors that influence students’ factors influencing plagiarism. An international comparison between German and Slovene students was made. Our research draws on students from two universities from the two considered countries that cover all traditional subjects of study. In this regard the conclusions are representative and statistically relevant, although we of course cannot exclude the possibility of small deviations if other or more institutions would be considered. Taken as a whole, there are no major differences between German and Slovene students when it comes to motivation for study and working habits. In both cases, more than two thirds of the students were highly motivated for study and more than 60% were working during their time of study. About 33% of the surveyed students spend on average two or less hours a day on the Internet, and about one quarter spend on average more than five hours a day on the Internet.

When it comes to explaining plagiarism in higher education, the German and Slovene students equally indicated the ease-of-use of information-communication technologies and the Web as the top one cause for their behaviour. Which does not lag behind other notions of current contributions to the topic of plagiarism in the world. Indeed, our findings reinforce the notion that new technologies and the Web have a strong influence on students and are the main driver behind plagiarism [ 20 , 21 , 22 ]. An academic moral panic has been caused by the arrival in higher education of a new generation of younger students [ 39 ], deemed to be ‘digital natives’ [ 40 ] and allegedly endowed with an inherent ability for using information-communication technologies (ICT). This younger generation is dubbed ‘Generation Me’ [ 41 ], and it is believed that their expectations, interactions and learning processes have been affected by ICT. Introna, et al., Ma et al., and Yeo, agree that the understanding of the concept of plagiarism through the use of ICT is the main contributor to it being a problem [ 42 , 43 , 44 ]. The effortless use of ICT such as the Internet has made it easy for students to retrieve information with a simple click of the mouse [ 45 , 46 ].

The Slovene students in our study nominated the teaching factor as the second most important reason for plagiarism. This result is also found in other studies, namely those of Šprajc et al. [ 30 ] and Barnas [ 47 ]. Young people in Slovenia are, like in other Western societies, given a prolonged period of identity exploration and self-focus, i.e., freedom from institutional demands and obligations, competence, and freedom to decide for themselves [ 48 , 49 ]. The results of the German students however, contradict this finding that teaching factors are one of the most important factors influencing plagiarism. Indeed, the top two factors influencing plagiarism for the German students are actually pressure and pride—and not teaching factors. Overall though, the findings for both the German students and the Slovene students are in line with e.g. Koul et al., who suggest that factors influencing plagiarism may vary across cultures [ 4 ]. Among German students, the pressure and pride in the second and third places in terms of importance are mostly reflected, which does not lag behind the mention of the author Rothenberg stated that in Germany today ‘pride could be expressed for individual accomplishments’ [ 50 ]. As far as the Slovene students are concerned, the authors Kondrič et al. presumed that there is a specific set of values in Slovenia, which perhaps intensify the distinction between the collectivist culture of former socialist countries and the individualism of Western countries [ 51 ]. This might shed light on why the Slovene students consider teaching factors as being one of the most important factors influencing plagiarism.

Furthermore, several studies have implied that individual characteristics, especially gender, play an important role when it comes to plagiarism [ 12 , 13 , 15 , 16 ]. A number of studies from around the world have shown that men more frequently plagiarise than women do. For example, Reviews of North American’s research into conventional plagiarism has indicated that male students cheat more often than female students [ 12 ]. The results we found are basically in line with these findings. Since the average values of responses are significantly different for male and female students, gender seems to play an important role in terms of plagiarism.

Park pointed out that one reason for plagiarism is efficiency gain [ 11 ]. About 15 years after this statement, the study at hand is empirical evidence that efficiency gain due to different forms of pressure is still a factor that influences students’ behaviour in terms of plagiarism. Lack of knowledge and uncertainties about methodologies are additional factors that are frequently recognized as reasons for plagiarism [ 11 , 17 , 18 ]. The results at hand support these studies since the responses about e.g. academic skills demonstrate students’ lack of knowledge.

Another interesting finding of our study shows that students with a lower motivation for study spend more time on the Internet, which complements our finding that the Internet is one of the simplest solutions for studying. The German students showed a somewhat higher level of motivation to study than the Slovene students, but the difference is not statistically significant.

We would nevertheless like to draw attention to the perceived difference, which refers to the perception of the factors influencing the plagiarism of the teacher factors and academic skills (Slovene students) and pride and pressure (German students). The perceived difference between students is one of the social dimensions that represents a tool to promote true motivation for study and proper orientation without ethically disputable solutions (such as plagiarism). In all this, it makes sense to direct students and educate them from the beginning of education together with information technology, while also builds responsible individuals who will not take technology and the Internet as a negative tool for studying and succeeding, but to help them to solve and make decisions in the right way. The main aim of this research into Slovene and German students was to increase understanding of students’ attitudes towards plagiarism and, above all, to identify the reasons that lead students to plagiarise. On this basis, we want to expose the way of non-plagiarism promotion to be developed in a way that will be more acceptable and more understandable in each country and adequately controlled on a personal and institutional level.

Conclusions

In contrast to a number of preliminary studies, the major findings of this research paper indicate that new technologies and the Web have a strong and significant influence on plagiarism, whereas in this specific context gender and socialisation factors do not play a significant role. Since the majority of the students in our study believe that new technologies and the Web have a strong influence on plagiarism, we can assume that technological progress and globalisation has started breaking down national frontiers and crossing cultural boundaries. These findings have also created the impression that at universities the gender gap is not predominant in all areas as it might be in society.

Nevertheless, some minor results in our study indicate that there are still some differences between Slovene and German students. For example, it seems like in Slovenia, teaching factors have a greater influence on plagiarism than in Germany. Indeed, in Germany, the focus should rest on the implementation and publication of a code of ethics, and on training students to deal with pressure.

This research focuses on only two countries, Slovenia and Germany. Thus, the findings at hand are not necessarily generalizable, though they do manifest a certain trend in terms of the reasons why students resort to plagiarism. Furthermore, the results could be a starting point for additional comparative studies between different European regions. In particular, further research into the influence of digitalization and the Web on plagiarism, and the role of socialisation and gender factors on plagiarism, could contribute to the discourse on plagiarism in higher education institutions.

Understanding the reasons behind plagiarism and fostering awareness of the issue among students might help prevent future academic misconduct through increased support and guidance during students’ time studying at the university. In this sense, further reflection on preventive measures is required. Indeed, rather than focusing on the detection of plagiarism, focusing on preventive measures could have a positive effect on good scientific practice in the near future.

Supporting information

S1 table. frequency distributions of the study variables..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.s001

S2 Table. Descriptive statistics for items referring to the factors influencing plagiarism, by nationality and results of the t-Test.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.s002

S3 Table. Descriptive statistics for items referring to the factors influencing plagiarism, by gender and results of the t-Test (SLO).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.s003

S4 Table. Descriptive statistics for items referring to the factors influencing plagiarism, by gender and results of the t-Test (GER).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.s004

S5 Table. Descriptive statistics for items referring to the factors influencing plagiarism, by area of study and results of the One-Way ANOVA (SLO).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.s005

S6 Table. Descriptive statistics for items referring to the factors influencing plagiarism, by study area and results of the t-Test (GER).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.s006

S7 Table. Descriptive statistics for items referring to the factors influencing plagiarism, by motivation and results of the t-Test (SLO).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.s007

S8 Table. Descriptive statistics for items referring to the factors influencing plagiarism, by motivation and results of the t-Test (GER).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.s008

S1 File. Individual data.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.s009

- 1. Perrin R. Pocket guide to APA style. 3 rd ed. Boston, MA: Wadsworth; 2009.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 5. Fishman T. We Know it When We See it is not Good Enough: Toward a Standard Definition of Plagiarism that Transcends Theft, Fraud, and Copyright. Paper presented at the 4th Asia Pacific Conference on Educational Integrity, NSW, Australia. 2009. Available from: http://www.bmartin.cc/pubs/09-4apcei/4apcei-Fishman.pdf

- 6. Hall TE. Beyond culture. New York: Anchor Books; 1979.

- PubMed/NCBI

- 8. Schwinges RC. (Ed.). Examen, Titel, Promotionen. Akademisches und Staatliches Qualifikationswesen vom 13. bis zum 21. Jahrhundert [Examinations, Titles, Doctorates, Academic and Government Qualifications from the 13th to the 21th Century]. Basilea: Schwabe; 2007. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199694-044.003.0009

- 16. Gerdeman RD. Academic dishonesty and the community college, ERIC Digest, ED447840; 2000. Available from: https://www.ericdigests.org/2001-3/college.htm

- 27. Songsriwittaya A, Kongsuwan S, Jitgarum K, Kaewkuekool S, Koul R. Engineering Students' Attitude towards Plagiarism a Survey Study. Korea: ICEE & ICEER; 2009.

- 37. Razera D, Verhage H, Pargman TC, Ramberg R. Plagiarism awareness, perception, and attitudes among students and teachers in Swedish higher education-a case study. Paper Presented at the 4th International Plagiarism Conference-Towards an authentic future. Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK. 2010. Available from http://www.plagiarismadvice.org/researchpapers/item/plagiarism-awareness

- 39. Bennett S, Maton K. Intellectual field or faith-based religion: moving on from the idea of ‘digital natives’. In Thomas M, editor. Deconstructing digital natives. London: Routledge; 2011. pp. 169–185.

- 40. Prensky M. Digital wisdom and homo sapiens digital. In Thomas M, editor. Deconstructing digital natives. London: Routledge; 2011. pp. 15–29.

- 42. Introna L, Hayes N, Blair L, Wood E. Cultural attitudes towards plagiarism. Lancaster: University of Lancaster; 2003.

- 48. Puklek-Levpušček M, Zupančič M. Slovenia. In Arnett JJ, editor. International encyclopedia on adolescence. New York: Routledge; 2007. pp. 866–877. 10.1007/s10734-011-9481-4 .

- 49. Zupančič M. Razvojno obdobje prehoda v odraslost—temeljne značilnosti. [Developmental period of transition to adulthood—basic characteristics]. In Puklek-Levpušček M, Zupančič M, editors. Študenti na prehodu v odraslost [Students in transition to adulthood]. Ljubljana: Znanstveno raziskovalni inštitut Filozofske fakultete; 2011. pp. 9–38.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free plagiarism check.

- Knowledge Base

How to Avoid Plagiarism | Tips on Citing Sources

Published on October 10, 2021 by Tegan George . Revised on November 21, 2023.

Plagiarism means using someone else’s words or ideas without properly crediting the original author. Sometimes plagiarism involves deliberately stealing someone’s work, but more often it happens accidentally, through carelessness or forgetfulness.When you write an academic paper, you build upon the work of others and use various credible sources for information and evidence. To avoid plagiarism, you need to correctly incorporate these sources into your text.

You can avoid plagiarism by :

- Keeping track of the sources you consult in your research

- Paraphrasing or quoting from your sources (by using a paraphrasing tool and adding your own ideas)

- Crediting the original author in an in-text citation and in your reference list

- Using a plagiarism checker before you submit

- Use generative AI tools responsibly (outputs may be detected by an AI detector )

Even accidental plagiarism can have serious consequences , so take care with how you integrate sources into your writing.

Table of contents

Keeping track of your sources, avoiding plagiarism when quoting, avoiding plagiarism when paraphrasing, citing your sources correctly, using a plagiarism checker, using ai tools responsibly, checklist: plagiarism prevention, free lecture slides, frequently asked questions.

One of the most common ways that students commit plagiarism is by simply forgetting where an idea came from and unintentionally presenting it as their own. You can easily avoid this pitfall by keeping your notes organized and compiling a list of citations as you go.

Clearly label which thoughts are yours and which aren’t in your notes, highlight statements that need citations, and carefully mark any text copied directly from a source with quotation marks.

In the example below, red indicates a claim that requires a source, blue indicates information paraphrased or summarized from a source, and green indicates a direct quotation.

Notes for my paper on global warming

- Greenhouse gas emissions trap heat and raise global temperatures [cite details]

- Causes more severe weather: hurricanes, fires, water scarcity [cite examples]

- Animal habitats across the world are under threat from climate change [cite examples]

- Just this year, 23 species have been declared extinct (BBC News 2021)

- “Animals are changing shape… some are growing bigger wings, some are sprouting longer ears and others are growing larger bills” in order to cool off (Zeldovich 2021)

Managing sources with the Scribbr Citation Generator

To make your life easier later, make sure to write down the full details of every source you consult. That includes not only books and journal articles, but also things like websites, magazine articles, and videos. This makes it easy to go back and check where you found a phrase, fact, or idea that you want to use in your paper.

Scribbr’s Citation Generator allows you to start building and managing your reference list as you go, saving time later. When you’re ready to submit, simply download your reference list!

Generate accurate citations with Scribbr

Prevent plagiarism. run a free check..

Quoting means copying a piece of text word for word. The copied text must be introduced in your own words, enclosed in quotation marks , and correctly attributed to the original author.

In general, quote sparingly. Quotes are appropriate when:

- You’re using an exact definition, introduced by the original author

- It is impossible for you to rephrase the original text without losing its meaning

- You’re analyzing the use of language in the original text

- You want to maintain the authority and style of the author’s words

Long quotations should be formatted as block quotes . But for longer blocks of text, it’s usually better to paraphrase instead.

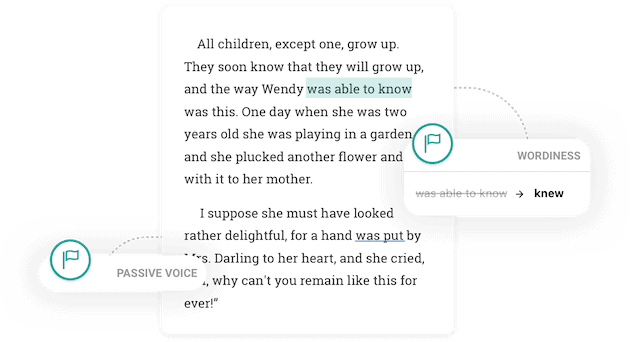

Paraphrasing means using your own words to explain something from a source.

Paraphrasing does not mean just switching out a few words from a copy-pasted text. To paraphrase properly, you should rewrite the author’s point in your own words to show that you have fully understood it.

Every time you quote or paraphrase, you must include an in-text or footnote citation clearly identifying the original author. Each citation must correspond to a full reference in the reference list or bibliography at the end of your paper.

This acknowledges the source of your information, avoiding plagiarism, and it helps your readers locate the source for themselves if they would like to learn more.

There are many different citation styles, each with its own rules. A few common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago . Your instructor may assign a particular style for you to use, or you may be able to choose. The most important thing is to apply one style consistently throughout the text.

The examples below follow APA Style.

Citing a single source

Citing multiple sources.

If you quote multiple sources in one sentence, make sure to cite them separately so that it’s clear which material came from which source.

To create correctly formatted source citations, you can use our free Citation Generator.

APA Citation Generator MLA Citation Generator

And if you’re citing in APA Style, consider using Scribbr’s Citation Checker , a unique tool that scans your citations for errors. It can detect inconsistencies between your in-text citations and your reference list, as well as making sure your citations are flawlessly formatted.

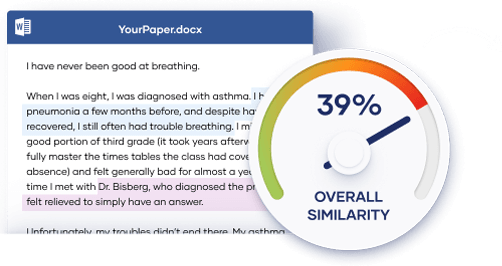

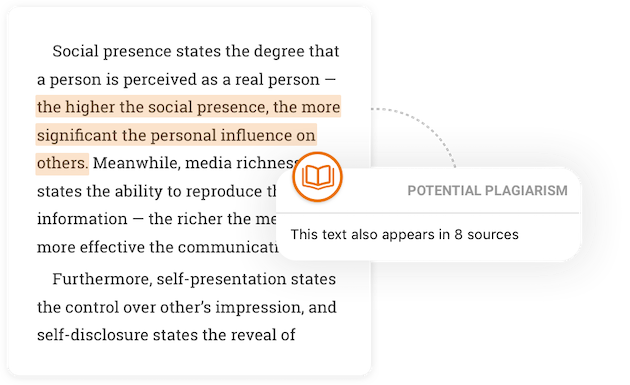

Most universities use plagiarism checkers like Turnitin to detect potential plagiarism. Here’s how plagiarism checkers work : they scan your document, compare it to a database of webpages and publications, and highlight passages that appear similar to other texts.

Consider using a plagiarism checker yourself before submitting your paper. This allows you to identify issues that could constitute accidental plagiarism, such as:

- Forgotten or misplaced citations

- Missing quotation marks

- Paraphrased material that’s too similar to the original text

Then you can easily fix any instances of potential plagiarism.

There are differences in accuracy and safety between plagiarism checkers. To help students choose, we conducted extensive research comparing the best plagiarism checkers .

Generative AI tools like ChatGPT can be helpful at different stages of the writing and research process. However, these tools can also be used to plagiarize in various ways (whether intentionally or unintentionally). When using these tools, it’s important to avoid the following:

- AI-assisted plagiarism: Passing off AI-generated text as your own work (e.g., research papers, homework assignments)

- Plagiarism : Using the tool to paraphrase content from another source and passing it off as original work

- Self-plagiarism : Using the tool to rewrite a paper you previously submitted

It’s important to use AI tools responsibly and to be aware that AI-generated outputs may be detected by your university’s AI detector .

When using someone else’s exact words, I have properly formatted them as a quote .

When using someone else’s ideas, I have properly paraphrased , expressing the idea completely in my own words.

I have included an in-text citation every time I use words, ideas, or information from a source.

Every source I cited is included in my reference list or bibliography .

I have consistently followed the rules of my required citation style .

I have not committed self-plagiarism by reusing any part of a previous paper.

I have used a reliable plagiarism checker as a final check.

Your document should be free from plagiarism!

Are you a teacher or professor who would like to educate your students about plagiarism? You can download our free lecture slides, available for Google Slides and Microsoft PowerPoint.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

Accidental plagiarism is one of the most common examples of plagiarism . Perhaps you forgot to cite a source, or paraphrased something a bit too closely. Maybe you can’t remember where you got an idea from, and aren’t totally sure if it’s original or not.

These all count as plagiarism, even though you didn’t do it on purpose. When in doubt, make sure you’re citing your sources . Also consider running your work through a plagiarism checker tool prior to submission, which work by using advanced database software to scan for matches between your text and existing texts.

Scribbr’s Plagiarism Checker takes less than 10 minutes and can help you turn in your paper with confidence.

To avoid plagiarism when summarizing an article or other source, follow these two rules:

- Write the summary entirely in your own words by paraphrasing the author’s ideas.

- Cite the source with an in-text citation and a full reference so your reader can easily find the original text.

Plagiarism can be detected by your professor or readers if the tone, formatting, or style of your text is different in different parts of your paper, or if they’re familiar with the plagiarized source.

Many universities also use plagiarism detection software like Turnitin’s, which compares your text to a large database of other sources, flagging any similarities that come up.

It can be easier than you think to commit plagiarism by accident. Consider using a plagiarism checker prior to submitting your paper to ensure you haven’t missed any citations.

Some examples of plagiarism include:

- Copying and pasting a Wikipedia article into the body of an assignment

- Quoting a source without including a citation

- Not paraphrasing a source properly, such as maintaining wording too close to the original

- Forgetting to cite the source of an idea

The most surefire way to avoid plagiarism is to always cite your sources . When in doubt, cite!

If you’re concerned about plagiarism, consider running your work through a plagiarism checker tool prior to submission. Scribbr’s Plagiarism Checker takes less than 10 minutes and can help you turn in your paper with confidence.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, November 21). How to Avoid Plagiarism | Tips on Citing Sources. Scribbr. Retrieved April 8, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/plagiarism/how-to-avoid-plagiarism/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, consequences of mild, moderate & severe plagiarism, types of plagiarism and how to recognize them, what is self-plagiarism | definition & how to avoid it, what is your plagiarism score.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

Plagiarism and duplicate publication

On this page, plagiarism and fabrication, due credit for others' work, nature portfolio journals' policy on duplicate publication, nature portfolio journals' editorials.

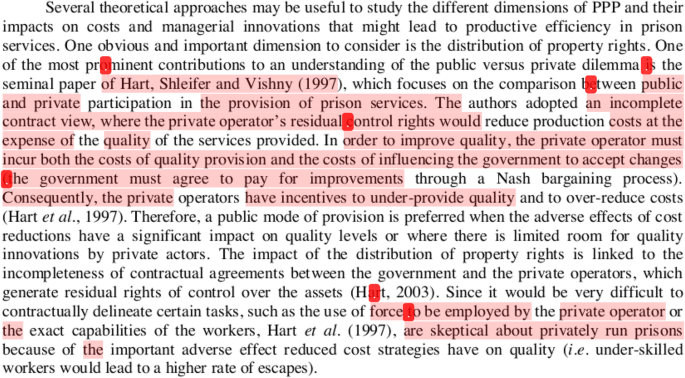

Plagiarism is unacknowledged copying or an attempt to misattribute original authorship, whether of ideas, text or results. As defined by the ORI (Office of Research Integrity), plagiarism can include, "theft or misappropriation of intellectual property and the substantial unattributed textual copying of another's work". Plagiarism can be said to have clearly occurred when large chunks of text have been cut-and-pasted without appropriate and unambiguous attribution. Such manuscripts would not be considered for publication in a Nature Portfolio journal. Aside from wholesale verbatim reuse of text, due care must be taken to ensure appropriate attribution and citation when paraphrasing and summarising the work of others. "Text recycling" or reuse of parts of text from an author's previous research publication is a form of self-plagiarism. Here too, due caution must be exercised. When reusing text, whether from the author's own publication or that of others, appropriate attribution and citation is necessary to avoid creating a misleading perception of unique contribution for the reader.

Duplicate (or redundant) publication occurs when an author reuses substantial parts of their own published work without providing the appropriate references. This can range from publishing an identical paper in multiple journals, to only adding a small amount of new data to a previously published paper.

Nature Portfolio journal editors assess all such cases on their individual merits. When plagiarism becomes evident post-publication, we may correct,retract or otherwise amend the original publication depending on the degree of plagiarism, context within the published article and its impact on the overall integrity of the published study. Nature Portfolio is part of Similarity Check , a service that uses software tools to screen submitted manuscripts for text overlap.

Top of page ⤴

Discussion of unpublished work

Manuscripts are sent out for review on the condition that any unpublished data cited within are properly credited and the appropriate permission has been attained. Where licenced data are cited, authors must include at submission a written assurance that they are complying with originators' data-licencing agreements.

Discussion of published work

When discussing the published work of others, authors must properly describe the contribution of the earlier work. Both intellectual contributions and technical developments must be acknowledged as such and appropriately cited.

Material submitted to a Nature Portfolio journal must be original and not published or concurrently submitted for publication elsewhere.

Authors submitting a contribution to a Nature Portfolio journal who have related material under consideration or in press elsewhere should upload a clearly marked copy at the time of submission, and draw the editors' attention to it in their cover letter. Authors must disclose any such information while their contributions are under consideration by a Nature Portfolio journal - for example, if they submit a related manuscript elsewhere that was not written at the time of the original Nature Portfolio journal submission.

If part of a contribution that an author wishes to submit to a Nature Portfolio journal has appeared or will appear elsewhere, the author must specify the details in the covering letter accompanying the Nature Portfolio submission. Consideration by the Nature Portfolio journal is possible if the main result, conclusion, or implications are not apparent from the other work, or if there are other factors, for example if the other work is published in a language other than English.

Nature Portfolio will consider submissions containing material that has previously formed part of a PhD or other academic thesis which has been published according to the requirements of the institution awarding the qualification.

The Nature Portfolio journals support prior publication on recognized community preprint servers for review by other scientists in the field before formal submission to a journal. More information about our policies on preprints can be found here .

Nature Portfolio journals allow publication of meeting abstracts before the full contribution is submitted. Such abstracts should be included with the Nature Portfolio journal submission and referred to in the cover letter accompanying the manuscript.

In case of any doubt, authors should seek advice from the editor handling their contribution.

If an author of a submission is re-using a figure or figures published elsewhere, or that is copyrighted, the author must provide documentation that the previous publisher or copyright holder has given permission for the figure to be re-published. The Nature Portfolio journal editors consider all material in good faith that their journals have full permission to publish every part of the submitted material, including illustrations.

- There are tools to detect non-originality in articles, but instilling ethical norms remains essential. Nature . Plagiarism pinioned, 7 July 2010.

- Scientific plagiarism—a problem as serious as fraud—has not received all the attention it deserves. Nature Medicine . The insider’s guide to plagiarism , July 2009.

- Tackling plagiarism is becoming an easier fight. Nature Physics. The truth will out , July 2009.

- Accountability of coauthors for scientific misconduct, guest authorship and deliberate or negligent citation plagiarism, highlight the need for accurate author contribution statements. Nature Photonics. Combating plagiarism , May 2009.

- Plagiarism is on the rise, thanks to the Internet. Universities and journals need to take action. Nature . Clamp down on copycats , 3 November 2005.

Fraud and replication

- When it comes to research misconduct, burying one's head in the sand and pretending it doesn't exist is the worst possible plan. Nature Chemistry. They did a bad bad thing, May 2011.

- Commit to promoting best practice in research and education in research ethics. Nature Cell Biology . Combating scientific misconduct, January 2011.

- Scientific misconduct may be more prevalent than most researchers would like to admit. The solution needs to be wide-ranging yet nuanced. Nature . Solutions, not scapegoats, 19 June 2008.

- Related Commentary by S. Titus et al. in the same issue of Nature: Repairing research integrity .

- The use of electronic laboratory notebooks should be supported by all concerned. Nature . Share your lab notes, 3 May 2007.

- Record-keeping in the lab has stayed unchanged for hundreds of years, but today's experiments are putting huge pressure on the old ways. Nature News Feature. Electronic notebooks: a new leaf, 7 July 2005.

- The true extent of plagiarism is unknown, but rising cases of suspect submissions are forcing editors to take action. Nature special report. Taking on the cheats , 19 May 2005.

Duplicate publication

- Clarifying journal policies on overlapping or concurrent submissions and embargo. Nature Neuroscience . Navigating issues of related submission and embargo, July 2014.

- Duplicate publication dilutes science. Nature Photonics. Quality over quantity , September 2011.

- On fragmenting one coherent body of research into as many publications as possible. Nature Materials . The cost of salami slicing , January 2005.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Original article

- Open access

- Published: 07 January 2021

Plagiarism in articles published in journals indexed in the Scientific Periodicals Electronic Library (SPELL): a comparative analysis between 2013 and 2018

- Marcelo Krokoscz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6869-864X 1

International Journal for Educational Integrity volume 17 , Article number: 1 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

30k Accesses

6 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

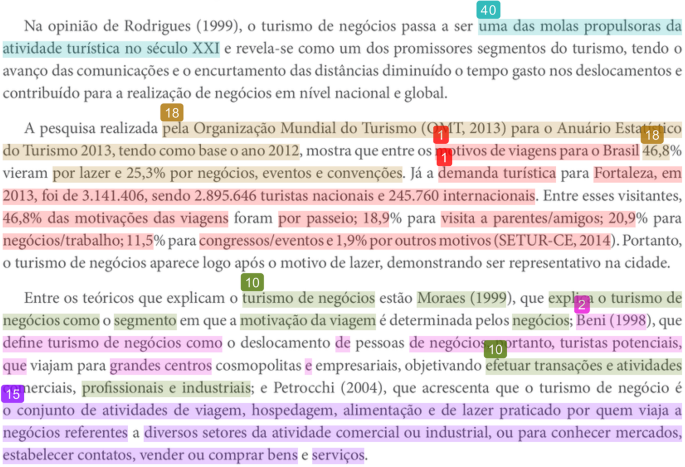

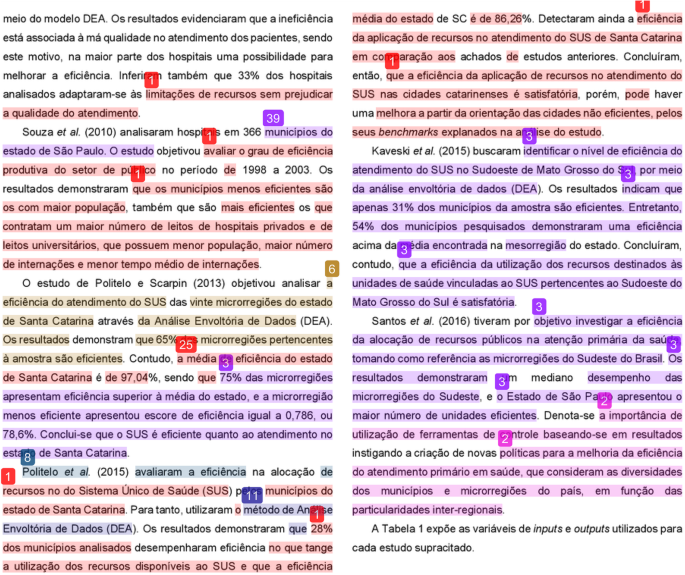

This study analyzes the possible occurrence of plagiarism and self-plagiarism in a sample of articles published in the Scientific Periodicals Electronic Library (SPELL), an open database that indexes business journals in Brazil. The author compared one sample obtained in 2013 ( n = 47 articles) and another selected from 2018 ( n = 118 articles). In both samples, we verified the guidelines that each of the journals provided to authors regarding plagiarism and the adoption of software to detect textual similarities. In the analysis conducted in 2013, it was found that only one journal (2%) mentioned the word “plagiarism” in its policies, although the majority of the directives required guarantees that no type of violation of authors’ rights was contained in the manuscript. In the analysis conducted in 2013, it was determined that there were literal reproductions in 31 published articles (65.9%), and no relevant similarities with other publications were encountered in 16 articles (34.1%). In the 2018 analysis, 69 of the publications (58%) included observations and guidelines related to plagiarism and self-plagiarism. In the analysis conducted in 2018, it was found that similarities (plagiarism and self-plagiarism) occurred in 52 articles (44%), and no relevant evidence of plagiarism or self-plagiarism was found in 66 (56%) manuscripts. Although a reduction in the index of the occurrence of plagiarism was observed, as was an increase in the instructions on the prevention of plagiarism by authors, practices directed at guiding authors by means of directives concerning the importance of preventing plagiarism in manuscripts submitted for publication can be recommended.

Introduction

It has been reported in the literature that studies marred by a lack of scientific integrity due to scientific misconduct such as plagiarism or redundant publication (self-plagiarism) and works containing gift or ghost authorship are a recurring problem, which has intensified as of late (Amos 2014 ; Associação Nacional de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação e Pesquisa em Administração (ANPAD) 2017 ; Committee On Publication Ethics (COPE) 2011 ; Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) 2011 ; Council of Science Editors (CSE) 2018 ; Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) 2011 ; Koocher and Keith-Spiegel 2010 ; Van Nordeen 2011 ).