Our apologies for intruding. Please spare a couple of minutes.

'The India Forum' is an experiment in reader-supported publication. It is free to read; it carries no ads and it is free of commercial backing.

To make this work though and to continue to bring you informed analysis and thoughtful comment on a range of contemporary issues, we need your help.

We need your support to grow into a publication you will continue to want to read. Please begin by making a donation to the Vichar Trust.

Donations enjoy tax exemption under Section 80G of the Income Tax Act.

Before you go...

Sign up for 'the india forum' newsletter.

Get new articles delivered to your inbox as soon as they are published every Friday.

Click here if already registered

Children in Kashmir studying under a tree (September 2008). The school building was shelled in December 2006 | Flickr ( CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 )

The English Education of a Kashmiri

Ashaq Hussain Parray

Share this article

Two educated Kashmiri men picked up a quarrel. They began with English, then resorted to Urdu, and when even that did not work, threw a mouthful of invectives at each other in eloquent Kashmiri.

When class and power are performed publicly, Kashmiris show off their English: while fighting, at birthday parties, marriage ceremonies, and academic conferences. Being fluent in English is synonymous with being an intellectual, and speaking one's mother tongue a sign either of a backward villager or idiocy. But English is not a panin — our own — language for most Kashmiris. The early beneficiaries of English-medium education were the Kashmiri Pandits and, later, elite Kashmiri Muslims, who controlled most of the administration. Modern schools like Tyndale Biscoe, set up by missionaries in the late 19th century, continue to be a space for the elite. For working-class Kashmiri students like me, battling poverty and political conflict while pursuing academic ambitions, there are few avenues to access English and aspire for a better life.

A child of parents who never went to school and were illiterate, not speaking fluent English became a preoccupation for me. During my MA days in the University of Kashmir, when I worked on the side as a labourer, cleaning muck from the flood-hit state secretariat in Srinagar, I would try to read the English-language Greater Kashmir newspaper during tea breaks. But when the malik saw that a labourer had dared to read English, he immediately snatched away the paper and chided me: None among seven generations of your family will be able to understand it.

I felt choked. I wanted to teach him a lesson, but the spectacle of my tattered shoes and my blistered hands held me back. I sought his forgiveness and went back to work.

I was born in December 1992, though my parents don't know when exactly, in a remote hamlet in north Kashmir. It was in an attic, I am told, where my mother's spinning wheel and her body jostled for space to welcome me. My parents did not record my birth date and time; pen and paper had never been seen in our ancestral mud house.

My primary schooling was in Urdu. Kashmiri, our mother tongue, did not figure in the scene.

My father, a carpet weaver, entrusted me to a sarkari school to rid himself of my constant childish skirmishes around his workplace. These schools were a dumping ground, for working-class parents to cast off their children during the day. My primary schooling was in Urdu. Kashmiri, our mother tongue, did not figure in the scene. A particular teacher from the city would make fun of us: You village wretches, why don't you get a proper haircut and nice shoes. You fart in the class. Stinking bloody rascals! Our homework sometimes included fetching corn, cereal, cucumbers, and tomatoes for demanding teachers to pass us in exams.

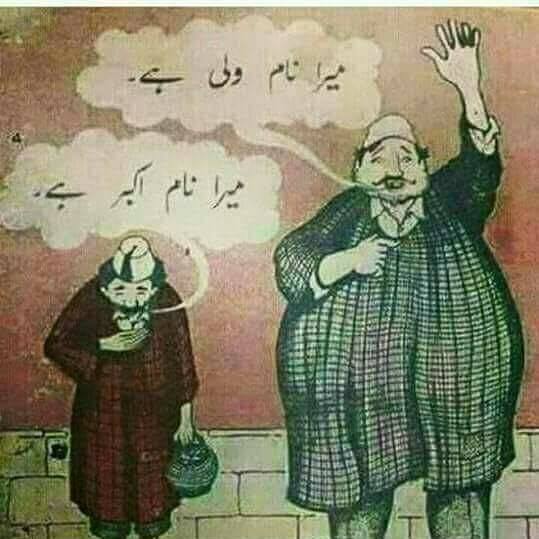

Our teachers would draw a rat or a hare on the black-painted cement board and write the description below in Urdu. “Chooha”; “Khargoesh” — we would repeat after them. The only lesson I remember from my school textbook read Mera nam Wali hai, mera nam Akbar hai (My name is Wali; my name is Akbar). Akbar and Wali, two men depicted in illustrations with their hands up in the air, one fat and the other thin as a stick. I did not know who Wali and Akbar were or why their curious faces pestered us. What were they trying to say? Did it matter, I asked myself, that they did not exist in real life? Were their hands, pointed upwards to the sky, an early lesson for the performance security forces would subject us to later in life, when villagers would be marched through the streets, their Hands Up! like Akbar’s and Wali’s, into open fields where 'suspected’ ones received blows with gun butts on their jaws?

A world ambushed by English

The spectre of English began to haunt me in high school and infused a sense of inferiority in me. Earlier, I had understood everything taught in Urdu and bridged through Kashmiri. Now I was forced to peer into an unfamiliar world that bamboozled me by its elusive nature. I could not understand anything in a ninth standard textbook. Our teachers too were baffled by the surfeit of English in their lives. That they had never been trained was an undeniable truth, the festering sore of a system of misgovernance. They themselves had sent their children to elite English medium schools.

Jumhuriyat felt easy to bellow out in a place where no shards of it were left anymore. But democracy would not reveal itself to our imagination even after regularly thrashings.

Simple additions and subtractions became too abstruse for me. Hisaab, tafreek, jamah, takseem, kenchi-zarab metamorphosed into mathematics , subtraction , addition , division, multiplication . It was as if Wali and Akbar's old world of Urdu had been attacked and colonised by soldiers bearing the ammunition of the English language: pronunciation, accent, grammar. Known felt like the Kashmiri word kanoon, law , but had to be pronounced without ‘k’. We had heard of kanoon on Doordarshan, but never on the streets. The 'k' in known would be silent forever, like the Kashmiris; assumed to have been spoken without being ever allowed to speak for itself. We would giggle at the word Jumhuriyat because it had some semblance with Jum Khan, our popular Kashmiri anti-hero. Jumhuriyat felt easy to bellow out in a place where no shards of it were left anymore. But democracy would not reveal itself to our imagination even after regularly thrashings on our buttocks. All we had were years of funeral processions of democracy in Kashmir, sometimes led by gun-toting soldiers and sometimes carried out under curfewed nights.

We had a grammar textbook that I parroted without understanding anything about the workings of language. English grammar, with its many tenses and verb forms and adjectives and adverbs, tossed me about like our big-horned bull. She was a third-person singular pronoun but felt like my identity as a Shia Muslim, called Sh’ii in Kashmir. The idea of active and passive voice was slippery like the Dal's frozen waters. Why was John killed a rat made out to be different from A rat was killed by John ? I began to wonder about John because we would occasionally kill the rats who would steal the walnuts and the corn we stored at home for the winter, lining their stores even though we would many a times go to bed hungry. But I did not know who John was or why he had to kill the rat. What crime had the rat committed to be killed remained a haunting question. It would take me years to realise that in Kashmir one could be killed without any crime.

How are vegetables dried and used during winters in Kashmir? I knew the answer. I had helped my mother on many occasions […] But I didn't know enough English to express it.

The matriculation exams drew near. Sitting up late at night in our single-room home, the flickering flame of the kerosene lamp would accompany me through December nights whilst I wrestled with knowledge cloaked in English. I failed at this prospect of early enlightenment and resorted to rote learning without any effort to articulate my ideas.

In the Biology exam, they asked a very simple question: How are vegetables dried and used during winters in Kashmir? I knew the answer. I had helped my mother on many occasions to dry out tomatoes and bottle gourd slices on a tin sheet during the summers. But I didn't know enough English to express it on the answer sheet. I mustered courage and managed to write some words in a chutney of English, Urdu, and Urdu-fied Kashmiri: First, we get vegetable , and then you cutting it tukde tukde . I wrote a note at the end: sir, please pass karna, jawab ata hai magar English nahi ata hai , I beseech you, sir, please mark me pass. I know the answer, but I don't know English . When I checked my results, I showered a bucketful of blessings to the evaluator who had understood my agony.

The saddest lines

For college, I had to choose an area of study, something I would be interested in life long. I had gone fishing and asked my friend to fill the college application on my behalf. To my surprise, he had opted English Literature as my future hell.

The Kashmiri language has no quick way of falling in love; we had to borrow the English I love you to fall in love.

When term began, our professor taught us Pablo Neruda's Tonight I Can Write the Saddest Lines . For an hour, we did not raise our head to face her. We were blushing adolescents, trying hard to give the impression that we were not enjoying what appeared as erotica. We were scandalised that the poet talked about how he kissed his beloved and how he missed her and how he felt about love and forgetting. Not that we were strangers to love or emotions — most of us had had some love history. But the way Neruda talked about kissing and hugging was too much for us. We had never seen a man and a woman kiss, save the masculine attempts at indecent kissing in old Bollywood movies.

We were brought up in a culture where erotic love and its expression were policed. Love was carried out in whispers or best scribbled on little pieces of paper thrown in the beloved's way. “Mujy tum achi lgti ho” — she would blush at this sight of the love exposed on a piece of paper as she read the message late night away from her family. It was love, and its peak expression mostly unexpressed but understood in our language. The Kashmiri language has no quick way of falling in love; we had to borrow the English I love you to fall in love. It would never convey what we wanted to convey and felt worn out and fake like a politician’s promise.

Our roads were war zones, our homes were torched, our people were taken to torture chambers, and we were busy studying Shelley's Ode to the West Wind .

We were in love with the idea of love and rarely caught a glance of our more imaginary than real beloveds during religious gatherings or in institutions. Teachers ensured gender segregation and put surveillance on our emotional history. As if all this was not enough to alter our sense of expressing love and desire, we had John Donne's poem Go and Catch a Falling Star in our syllabus. The cynical Donne was saying that a fair and a faithful woman was an impossibility. I mistook poetry as objective truth, which distorted my view of women. The boredom and ennui of learning Greco-Roman mythology and about Victorian women full of coquetry and mannerisms brought me down, even as my land seethed with anger and political strife. The experience of studying English and American culture that had nothing to do with my context, of a Kashmiri Muslim caught in a war zone, felt like the poet-saint Wahab Khar praising Chetan Bhagat for his mystical insights. Our roads were war zones, our homes were torched, our people were taken to torture chambers, and we were busy studying Shelley's Ode to the West Wind . My father’s bedtime dastaans and daleels felt closer to home. Laila and Majnun, Gul Bakawali, Ajab Malik, Nosh Lab, and Aknandun were our neighbours.

An impossible grammar

One day, while I was helping my father to weave carpets, I came across an advertisement for interviews for a contractual assistant professor position at a local university. I gazed at the offered salary of 25,000 rupees, like a child beggar would at an elite family feasting in a restaurant. Like a wretched gamester, I went to try my luck. During the interview, I faced the old crisis of English. Why was this language, defying my pursuits, and refusing to let me speak? Why was I not able to speak fluently? I had no faith in me because poverty had taken everything from me- the faith in my stars and the faith in life.

My students were more concerned about where the next encounter […] would break out and whether we would live to see the next day or not. I had no grammar to offer them to safeguard their lives.

A miracle happened and I was selected for the job. Now I had to deliver lectures to MA English students, a job I was least prepared for. It made no sense to teach English and American literature to students who like me did not even know whether Europe and the US were the same or different territories. Like me, my students were more concerned about where the next encounter between security forces and militants would break out and whether we would live to see the next day or not. I had no grammar to offer them to safeguard their lives from the violence. The present tense would not melt away their fear; the past tense would not erase their violence-filled past, and my lessons on the future tense would not offer them hope of a better tomorrow. One day while I was teaching English Communication Skills, which I hardly possessed myself, there was an encounter between security forces and militants nearby. When the students protested, they received shells in response. We were caught inside a classroom, fearing that it was the end. I didn't want to be killed by a 'stray' bullet. It terrified me. I could see and feel the anger and fright in my students’ eyes too.

We were all caught up in a grammar of violence with no route of escape in view. They Sent Smoke Shells to the Sky would have been a perfect tongue twister for a teacher like me trying to teach English to learners whose survival was at stake. Somehow, we survived.

Of neither the yarbal nor the academy

Meanwhile, the gulf between me and my family and villagers kept stretching to a point of no return. Nursing dreams of a better life, English took me far away from my family and my roots. It mixed my memory and desire while playing with the mud of history that I carried with me. My father looked up to me with much hope that I would someday be able to remove the curse of poverty from our lives. I longed to stroll with my school-dropout village friends and talk about stuff that mattered to us most: whether we were prepared for next harsh winter; whether the electricity would be consistent in the coming winter; whether there would be nocturnal raid in a nearby village; and whether we could smoke after dusk on the yarbal, the ghat steps along the river.

My education had undone me; its violence had seeped deep into the inner parts of my being. It had separated me from myself, from my family, my childhood friends and my village.

It had become impossible. My friends felt too reserved to talk with whom they considered an 'enlightened' man like me. They imagined I had moved far beyond them; that they were not worth me: that I was hallowed and not to be soiled by their gossip and their everyday. While I longed to be with them, my education had undone me; its violence had seeped deep into the inner parts of my being. It had separated me from myself, from my family, my childhood friends, and my village.

My intellectual curiosity was satiated by reading and failed attempts at engaging the academic world, but my emotional ties with my family, friends, and villagers would be strained. Even the academy, which I had looked up to as a haven of knowledge and enlightenment, was a space of invisible violence, full of people who had imposed self-styled intellectual postures. It expected you to generate research without ever training you properly. It was bound to end up in self-destruction because the system made you believe that you were not worthy enough if you didn't produce quality publications.

Academic prestige lay in publishing papers in top-tier journals. The cruel irony was that most of those journals belonged to the west and expected you to emulate them. This academic colonialism would ensure to produce subjectivities mimicking and expressing the world through someone else's lenses. After a reviewer of an article I submitted to a journal wrote that my language read as if a child had scribbled lines, I began to descend into despair and depression, doubting my worth.

English kept me tied even when I wanted it to let me go. They would not educate us in our own culture and language, and instead exiled us into a universe that was not ours. In a conflict-ridden space like Kashmir, can there be an articulation of a subject produced by the intersection of the violent effects of class, political conflict, and academic research? Can working-class people express and understand the world in a language that is not their own, while simultaneously aspiring to be upwardly mobile?

Is that desire worth the struggle it takes to reach there?

The Household Consumption Expenditure Survey 2022-23

Essential Work, Dispensable Workers

An Insightful Account of the Life and Work of B.R. Ambedkar

How I Defected from Vegetarianism

Register here for a weekly email about new articles; Donate here to support ‘The India Forum’

Ashaq Hussain Parray is a PhD student of English at Aligarh Muslim University writing a dissertation on Mirza Ghalib. He has published poems and translations in Bombay Literary Magazine, nether Quarterly, Punch Magazine, and Inverse Journal.

The India Forum welcomes your comments on this article for the Forum/Letters section. Write to: [email protected]

Right to Healthcare in Times of Universal Health Coverage

Two visions for india, sign up for the india forum updates.

Get new articles delivered to your inbox every Friday as soon as fresh articles are published.

The India Forum seeks your support...

to sustain its effort to deliver thoughtful analysis and commentary that is without noise, abuse and fake news.

Vedic Origin

Grierson's views, kashmiri and pishachi, is kashmiri a dardic language.

English Shina Kashmiri Sanskrit acid churko tsok chukra after phatu pati pashchat army sin sina sena aunt pafi (Hindi fufi) poph pitushvasr autumn sharo harud sharad be bo- bov bhu beard dei daer danshtrika between maji (Pkt. majjh, Hindi manjh) manz madhya blue nilo (Hindi nila) nyul nila Bone atoi aedij asthi bow danu duny dhanush break put phut sphot cold shidalo shital (the actual Kashmiri word is 'shihul') shital cow go gav gau, gav dance nat nats nrtya day dez doh divas death maren mara (marun) maranam dog shu hun shun or shwan dry shuko (Hindi sukha) hokh shushka ear kon kan karna eat ko- khe khad escape much mwkal much, mukti face mukh mwkh mukham far dur dur duram feet pa pad pada finger agul ongijy anguli fortnight pach pachh paksha give di (the actual word is doiki) di dada gold son swan swarna grape jach dachh draksha hand hat athi hasta leaf (of a tree) pato (Hindi 'pat') patir patra learn sich (Hindi sikh) hechh shikasha lip onti wuth oshtha man manuzho mohnyuv manushya meat mos maz mamsa milk dut dwd dugdha naked nanno non nagna name nam nav nama new nowu nov nava night rati rat(h) ratri old prono pron puranam plough hal ala- hala receive lay lab- labh right dashino dachhin dakshina rise uth woth utishtha sand sigel syakh sikta seed bi byol bijam silver rup rop(h) raupya sing gai gyav- gayanaga smoke dum dh dhuma smooth pichhiliko pishul pichhala sweet moro modur madhuram today acho az adya tongue jip (Hindi jibh) zyav jivha tooth don dand dantah vein nar nar nadi village girom gam (Pkt. gamo) gramah weep ro- riv- rodan/ruv woman chai triy stri write lik- lekh likha yes awa ava ava

The Sanskrit Factor

Shina Hindi English agar angar a live coal, cinder, spark agut angutha thumb ashatu ashakt powerless, helpless ash ashru, ansu a tear bago bhag part, portion, division bar var husband baris baras year bachhari bachhri female calf bish vis (note the cerebrals) poison biz khiti fear burizoiki burna to dip, be immersed charku charkha a spinning wheel chilu chir cloth choritu chor thief chushoiki chusna to suck dugunia dugna double dut dudh milk eklu akela alone gant (note the cerebral) ghanta hour gur gur molasses halizi haldi turmeric hanz hans a swan hiu hiya heart jaru jara- old age jinu jivit, jina alive/to live kali kalah-kari querrelsome kriye kiri anant khen kshan an instant, glamoment lash ajja shame manuk mendhak a frog manu manushya, manav a man mos mans meat, flesh musharu mishra mixed mushtake mushti, mutthi fist on anna grain, food paku pakka ripe pochi poti grand-daughter rog rog disease rong rang colour sand sand a bull sheur shvasur, sasur father-in-law sheu shvet white shing sing, shring horn shish shis head sioki sina to stitch, sew tal tal bottom teru terha crooked, bent jo jo which, who that

Kashmiri and Shina: Phonetic Dissimilarities:

Morphological differences.

(i) ai disher (in that place); hier, in (my, his, your) heart. (ii) mecizh, generally used with azhe, as mecezh azhe, upon the table; (iii) anu manuzezh (it ibareh nush, I have no faith in this man.

(i) ko, (who): ko mush, there was no one, mutu ko (someonel (ii) jeh (what): jega nush, (nothing at all), mutu jek (something else). (iii) kos thai buti daulat naye gub (the man who lost all your wealth), main jek daulat haniek, (whatever wealth there may be of mine).

Kashmiri a Sanskritic Language

Morphological features.

Kashmiri English Sanskrit yeli when yarhi teli then tarhi kar when, at what time karhi az today adya (Pkt. ajja) rath yesterday, yesternight ratrih suli early sakae (saka+ika) tsiry late chiram pati afterwards pashchat adi after that ada (Vedic) prath dohi everyday prati+divase prathryati everymonth prati+rituh prath vari every year prati+varse gari-gari every now and then ghatika (Pkt. ghatia, Hindi gari ghari) yuthuy as soon as yathapi tyuthuy at that very moment tathapi totany till then tavat yotany till such time until yavat, as

Kashmiri English Sanskrit yeti here, wherever yatra yetyath at this place tati there tatra tatyath at that place ati at that place/from that place atra kati at which placet (interrogative) kutra yot to this place/to whichever place itah tot to that place tatah kot to which place kutah, kutra tal under, below tale manz in, inside madhye (Pkt. majjhe, Hindi manjh) manzbag in the middle madhya+bhage dur far dura duri from far dure yapari on this side iha+pare

Kashmiri English Sanskrit yithi in which manner, as in this manner yatha tithi in that manner, like/that tatha kithi in what manner (interrogative) katham yithi-tithi somehow yatha+tatha

Order of words

Kashmiri English Hindi yot yi ti bati khe come here and eat your food yahan a aur khana kha humis adkas nishi beh sit near that boy us larke ke pas baith yim palav chhal wash these clothes ye kapre dho chay chyath gatsh leave after taking tea chay pikar ja guris (pyath) khas mount the horse ghore par charh vwazul posh an get the red flower lal phul la kuthis manz par Read inside the room kamre mein parh yitsi kathi ma kar Don't talk so much itni baten mat kar tot dwad ma che Don't take hot milk garam dudh mat pi nyabar ma ner Don't go out Bahar mat nikal gyavun ma gyav Don't sing a song gana mat ga vuni ma shong Don't sleep yet abhi mat so

Kashmiri English Sanskrit ati ma par Don't read there atra ma patha gari ma gatsh Don't go home ghriham ma gachchha az ma lekh Don't write today adya ma likha krud ma kar Don't be angry krodham ma kuru

Kashmiri English Hindi tse kya gatshi? What do you want? tumhe kya chahiye? su kot gav? Where di he go? voh kahan gaya? yot kar-ikh? When will you come here? yahan kab aoge? chany kur kati chhe? Where is your daughter? tumhari beti kahan hai? yi kamysund gari chhu? Whose house is this? yeh kiska ghar hai? bati kus kheyi? Who will take food? khana kaun khayega?

Kashmiri English Hindi su ladki yus yeti rozan os kot gav? Where has the boy who lived here gone? voh larka jo yahan rahta tha kahan gaya? su hun yus tse onuth tsol rath The dog which you brought, ran away yesterday voh kutta jo tumne laya tha, kal bhag gaya yosi kath taemy vaeneyi so drayi paez What he had said came out to be true jo bat usne kahi thi voh sach nikali yosi kath gaeyi, so gaeyi what is past is past jo bat gayi so gayi

Written Evidence: Kashmiri and MIA

Kashmiri English Sanskrit/Prakrit val hair vala kali head kapalah buth, mkh face mukh shondi (archaic) shunda aes mouth asya dyak forehead Pkt. dhika (Guj-daka-throat; doku-head) gal cheek galla aechh eye akshi nas/nast nose nasa/nast vuth lip oshtha dand teeth danta bum eyebrow bhru kan ear karna zyav tongue jivha tal palate talu hongany chin hanu vachh chest vaksha katsh armpit kakshah (Hindi kankh) yad belly Pkt. Dhidh (Panj. tid) mandal buttocks mand, alah naf navel nabhi athi hand hastah khonivath elbow kaphoni+vatah (c.f. Hindi kohni) ongij finger anguli nyoth thumb angustha (c.f. Sh. aguto) zang leg jangha khwar feet khurah / kshurah (-a cloven hoof- Note the change in meaning) pad feet pada tali-pod sole of a foot padatala nam nails nakham tsam skin charma rath blood rakta aedij bone adda daer beard danstrika naer vein, artery, blood vessel nadika maz flesh mamsah aendram intestines antram bwakivaet kidney vrikka+vatah (c.f. Hindi bukka) rum hair of the body roma nal tibia nalah, nalam (Pkt nalo) ryadi heart hrday

Kashmiri English Sanskrit zuv life jiva zyon to take birth Vedic jayate asun to laugh hasam rivun to weep rodana mandachh shyness manda+akshi volisun to feel joy, alacrity ullasah bwachhi hunger bubhuksha (c.f. Hindi 'bukh') shwangun to sleep shayanam nendir sleep nidra tresh thirst trsa

Kashmiri English Sanskrit pot(h)ur son putrah gobur garbharupah kur daughter kumari/kaumari (Pkt. kunwari, Kauri, Panj. kudi, Kaur) boy brother bhrataka (Hindi: bhai) beni sister bhagini petir uncle (father's brother) pitravya (Guj.pirai pitrayun) mas aunt (mother's sister) matushvasa (Pkt. Mausi, Hindi mausi, masi) pwaph aunt (father's sister) pitushvasa (Hindi phuphi) mam maternal uncle mamakah (Hindi mama) mamany wife of maternal uncle mamika nwash daughter-in-law snusa (Panj. nuh) zamtur son-in-law jamatr (Pali jamatar, Hindi jamai) hyuhur father-in-law shvasur (note the change of 'sh' to 'h') bemi brother-in-law (sister's husband) bhama zam sister-in-law (husband's sister) jama (Pk. jami) zaemi sister-in-law's husband jamipati zaemizi sister-in-law's daughter jameya benthir sister's son (wife's sister) bhagniputra syali run husband ramanah (Pkt. ramano ravannu) ranu, ravan (dialect) vyas female friend vayasi methir friend mitrah shaethir foe shatruh

Kashmiri English Sanskrit sih a lion, tiger simha (Pkt. siha) hos (t) an elephant hasti shal a jackal shrigalah (Pkt. siala) sor a pig shukarah gav a cow gau (gava) votsh a calf vatsah hun a dog shvanah, shun vandur a monkey vanarah gur (rural dialect gud) a horse ghotakah bachheri a colt vats+ika+ra tshavul a he-goat chhagalah haput a bear shvapadah vunth a camel ustrah hangul a stag shrgalah maesh a buffalo mahisah nul mongoose nakulah kaechhavi a tortoise, a turtle kachhapah krim a tortoise, a turtle kurmah vodur a weasel udrah sarup(h) a snake sarpah tsaer a sparrow chatkah (Hindi chiriya) kav a crow kakah kukil a cuckoo kokil kwakur a rooster, cock kukkutah aenz a swan hamsah har starling, mynah shari kakuv the muddy goose chakravakah grad a vulture grdrah brag a heron bakah titur a patridge tittirah byuch a scorpion vrschikah maech a housefly makshika kyom a worm krmi pyush a flea plushi (Hindi pissu) bumaesin earthworm bhumisnu

Kashmiri English Sanskrit chhot white, bleached shvet kruhun black krisnah (cf. Hindi kanha) shyam black shyamah nyul blue nilah lyodur yellow haridra vwazul red ujjvalah katsur brown karchurah gurut fair gaura

Kashmiri English Sanskrit athvar Sunday adityavarah (Hindi itvar, Sh. adit) tsandrivar Monday chandravarah bomvar Tuesday bhaumavarah bodvar Wednesday budhavarah brasvar Thursday brhaspativarah shokrivar Friday shukravarah batavar Saturday bhattarakavarah

Kashmiri English Sanskrit nun salt lavanam til oil tailam tomul rice tandulam danyi paddy dhanyam kinikh wheat kanikah bati cooked rice bhaktam dwad milk dugdham (Hindi dudh) gyav ghee ghrtarn pony water pamyam hakh pot-herb shakam vangun brinjal, egg-plant vangan oluv potatoe alukah muj radish mulika gazir carrot garjaram (Pkt. gajjaram) palak(h) spinach palankah ruhun garlic lashunam mithy fenugreek methika kareli bittergourd karvellakah al the bottle-gourd alabu hyambi beans shimbi (c.f. Hindi chhimi) nyom lime, lemon nimbukah kel bannana kadali (Pkt. kelao, Hindi kela) amb mangoe amram (Pkt. ambam) aeen pomegranate dadim dachh grapes draksha tang pear tanka khazir datepalm kharjurah (Pkt. khajjuro) narjil coconut narikelah ael cardamom aila tel sesamum seed tila rong clove lavang marits black pepper maricha martsivangun chilli maricha+vangana mong a species of pulse mudgah (Pkt. muggo) chani gram, chick-pea chanakah mah a bean masha muth a kind of pulse, vetch mayasthah, makushthah makey corn, maize markaka (Pkt. makka+ika) machh honey maksha khyatsir a dish of rice and split pulse krsharah (Hindi khichari) ras juice, gravy rasah layi parched grain laja shakkar unrefined sugar sharkara shonth dried ginger shunthi zyur cumin seed jirakah yangi asfoetida hingu gor molasses gudah (Hindi gur) rot a sweet cake offered to a god rotah

Kashmiri English Sanskrit swan gold swarna (Hindi sona) rwap(h) silver raupya tram copper tamra shastir iron shastrakah parud mercury pardah kenz brass, bellmetal kansya

Kashmiri English Sanskrit kapur cloth kalpatah (Pkt. kappado, Hindi kapra) pot woollen cloth patah sitsan needle suchika raz rope rajju sithir cotton thread sutrah trakir balance tarkari parmani weights parimana prang/palang couch paryankah bani utensils bhajana (Pkt. bhayana, Guj. bhanun, bhanen, Sindh banu) vokhul mortar ulukhalah kazul collyrium kajjalam kath wood kastham kammal blanket kambalam (Pkt. kammal) mokhti pearls mukta nav boat nava (Vedic) dungi a canoe, a large boat drona+kah (c.f. Hindi donga) shup winnower shurpa baehaets a large boat vahitra, vohittha (c.f. Hindi bohit) thal a large plate of metal sthalam (c.f. Hindi thal) gasi grass ghasam (Hindi ghas) kangir a portable fire-pot, brazier kastha+angari+ka, ka+angari+ka dand a staff dandam zal a net jalam baji a musical instrument vadya+kah (Hindi baja) vaejy a ring valaya kofur camphor karpuram gadvi a water vessel gadukah sranipath a loincloth snanapattam ganti bell ghanta sendir vermilion sindurah kapas cotton karpasam (Pkt. kappasam) toh chaff tusa turi claironet turya bin lute vina (Hindi bin) vaenk braid venika vag bridle valga (Hindi bag) baety wick vartika kangany comb kankatika mal garland necklace mala bungir bangle, bracelet vank+diminutive affix ri (c.f. Hindi bangri, bangri; Marathi bangrya) pulihor a shoe of grass or straw pula+kah (Hindi pula)

Name of the season Kashmiri Sanskrit spring sont(h) vasanta summer grishim gris, ma rainy season vaehrat varsa+ rituh (Hindi 'barsat') autumn harud sharad winter vandi varsant

Kashmiri English Sanskrit siri (Muslim Kashmiri 'akhtab') sun suryah tsaendir, tsaendram moon chandra, chandra+mas (Hindi 'chandrama') tarak(h) stars tarakah nab sky nabhah samsar the universe, world samsarah thal land sthalah vav air vayuh tap(h) sunlight atapah gash/pragash light prakash anigati darkness andha-ghata obur cloud abhra vuzimali lightening vidyut+mala gagiray rumbling, thunder gargara saedir sea, ocean samudrah sar lake sarah kval stream kulya van forest van sangar shrnga mountain sangarmal shrnga+mala peaks bunyul earthquake bhu+chala (Hindi bhuchal)

Kashmiri numerals

Numeral Kashmiri Sanskrit one akh ekah two zi dvi three tre tri four tsor chatur five pantsh pancha six she sastha seven sat(h) sapta eight aeth asta nine nnv nava ten daeh dash twenty vuh vimsha thirty trih trimsha forty tsatiji(h) chaturvimshata fifty pantsah panchashata sixty sheth shastih seventy satat(h) saptatih eighty shith ashitih ninety namath navatih hundred hath/shath shata thousand sas sahasra lakh lachh laksha crore karor kotih

APPENDIX II

Some examples of conjunction.

(1) k+t > tt: shakti > shatta, bhakti > bhatta, rakta > ratta; Mod. Kaihmiri: rakta 'rath', 'bhakta (-rice) > bati, saktum > (parched rice) > sot. (2) p+t tt/t: sapta > satta, avaptam > vato. Mod. ksh.: sapta > sath, avaptam > vot, tapta > tot. (3) t+y ch: nrtya- > nachha - Mod. Ksh nrtya > nats, atyeti > Pkt. achei > Ksh. ats (4) d+y jj: adya > ajja, vadyanti vajjan, Mod. Ksh: adya > az, vadyanti vazan. (5) g+dh > dh: dagdha > dadho, dadhos. Mod. Ksh. dagdha > dod, dodus. (6) dh+y > jj: madhya > majj (Pkt. majh, Hindi manjh); budhyate > bujje (Pali bujjhati, Pkt. bujjhai). Mod. Ksh: Madhya > manz, budhyate > bozi. (7) h+v > jj: dahyati > dajji Mod. Ksh: dahyati > dazi (8) d+v > b: dwitiva > Pkt. belya, bhiya, Mod. Ksh. beyi, dwadash > bah (Hindi barah) dwar > bar (Punjabi bari) (9) g+n > gg: lagnah > laggo Mod. Ksh. lagnah > lagun, log (10) g+n > nn: naghah > nanno Mod. Ksh. nagnah > non (11) t+m > p: atman > pan (Pkt. appa, Hindi ap, Sindhi, pan, u)

(1) s+t > th, tth: stana > than, hastat > attha Mod. Ksh: stana > than, stabmbh > tham, hasta > athi (2) s+th > th: sthal > thal (Pali thal', Pkt. 'thal', Punj. 'thal' Assamese 'thal', Guj, 'thal', Marathi 'thal', Hindi 'thal' Skt. stha piyitva > thavet, sthan > than, Mod. Ksh: 'sthal' > thal, sthapanam > thavun, sthal > thal. (3) s+ph > ph: 'sphotayah > photiy; Mod. Ksh: 'sphotyati' > phuti (4) s+m > s: 'smar' > sar, saret (Pali 'sar' -, Pkt. 'sar'-, Mod. Ksh: 'smar' > sar (5) sh+t/th > ttha: drstva dittho (Pali dittha, Pkt. datt,ha, dittha, Guj. Dithun, Awadhi: ditha), pristha > pittha, nistha > nittha, upavista > bittha; Mod. Ksh: dristwa dyut,h; prishtha > pyath, pith; kostha > kuth; oshtha > wuth; asta > ae: th kashtha > kath (Hindi kath) musti > mvath pusta > puth, jyestha > zyuth (Hindi jetha), bhrasta breth; upavista > byuth.

(1) k+r > k. krodhe > kodhe, krur > kur, Mod. Ksh: krur > kur (2) k+k > kk: chakra > chakka, shakra > shakka; Mod. Ksh: chukra > tsok, nakrashira > Pkt. nakkasira- > Mod. Ksh. naser (3) t+r > t: > tatra tatte, tati; yatra > yatti, yati; atra > ati, trasen > trase, tri- > ti. Mod. Ksh. tatra > tati; yatra > yeti, atra > ati, ratri > rath, kutra > kati (4) r+n/n, > n (n): varna > vanna; suvarna > suvanna, varnaya > vanno, (a) karne > akannet. Mod. Ksh.: karna > kan, swarna > swan, parna > pan, churna > tsin, (5) r+m > mm; m; karma > kamma, marma > mamma charma > chamma Mod. Ksh: karma > k aem, charma > tsam (6) r+p > pp: darpa > dappa; arpit > appu; Mod. Ksh: shurpa > shup; karpasa > kayas (7) r+h > ll, 1: yarhi > yille, tarhi > tille, Mod. Ksh: yarhi > yeli, tarhi > teli

(1) Agre > agari, agra; abhrat > abhra; sahasra > sass; nirgatah > niret, niri, nirim; sparsa > parshet, Mod. Ksh: abhra > obur, sahasra > sas, nirgatah > ner; sparsha > phash (Pkt. phassa)

(1) Ksh > chchh/chh: kshut. > chchot; akshi > achchi Mod. Ksh: kshut > tshot, akshi > achh, mandakshi > mandachh, bubhuksha > bochhi, laksha > lachh, vaksha > vachh, raksha > rachh, paksha > pachh, kaksha > kachh, taksha > tachh, yaksha > yachh, draksha > dachh, maksha > machh, kshalava > chhal, shiksha > hechh, veksha > vuchh (Punj. vekh) (2) ksh > kkh/kh: tikshna > tikkho Mod. Ksh: Lakshmi > lakhymi, sukshma > sikhim, paksha > (-wing) > pakh, kshama > khyama

(1) sh/s > h: dasha > daeh, ekadasha > kah, chaturdasha > chuddah, nashan > nahen Mod. Ksh: dasha > clah, ekadasha > kah, chaturdasha > tsodah, nashan > nahvun, sharad > harud, shat > hath, shuska > hokh, krisna > kruhun, chusana > tsihun, pesanam > pihun, vestana > vatun, visam > veh, tus > toh, manusya > mohnyuv, upavisha > beh; shun/shwan > hun; shari > haer, mashkah > moh. (2) sh/s remains unchanged: shobha > shub, maihisa mash, shurpa > shup, pusa/puspa > posh, asha > ash, tris. > tresh, mris. mash-, lesha > lish, prakash > gash. Initial 'h' changes to 'a' in Kashmiri. There are only a few examples of this in M.P. B.K. aild S.D.C.: hastat > attha, hasti > asis Mod. Ksh: hasta > athi, hasan > asun, ha,dda > adda

(1) a > a: sahara > sass, saphal > saphul, nibhrit > nibhara, rakshaka > rakshe, sahit > sate, priya > piya, nashya > nah. Mod. Ksh: sahasra > sas, raksha > rachh-,. nashya- > nah; (2) a > u: Medial 'a' often changes to 'u' in Kashmiri nominative singular. This tendency is equally strong in M.P., B.K. and S.D.C. Examples: Janaka > januk, anal > anul, varsana > varshun, tapodhana > tapodhun, sanrakshaka > sanrakshuk, Narad > Narud, Madhava > Madhuv. Mod. Ksh.: balak > baluk, varsan, a > varshun, rakshaka > rakhyuk, takshaka > takhyuk, Narada > Narud, sarpah > sarup, bhramrah > bombur (3) a > a: Like Maharashtri, Jain Maharashtri, Ardha- Magdhi Prakrits and Apabhramshas, a > a in fem. nom. sing. in M.P., B.K., and S.D.C. Modern Kashmiri also exhibits this tendency. Examples: Puja > puj, katha > kath, bala > bal, Usha (proper name) > Ush, mata > mat Mod. Ksh.: Puja > puz, katha > kath, bala > bal, Usa (proper name) > Ushi, mala > mal, sthala > thal (4) i > a: narpati > narpat, dinapati > dinapat, nayika > nayak, rishi > rish, rashi > rash, rashmi > rashm, buddhi > buddh, shakti > shatta, bhakti > bhatta, agni > agna. Mod. Ksh.: rsi > ryosh, ganapati > ganapat, rashi > rash, budcdhi > bwadh, gati > gath, prati > prath. (5) i > u: jiva > juv (Sindhi jiu, Panj, jiu, Kumanoni jyu, ziu, Bengali jiu, Marathi jiu, Hindi jiu) Mod. Ksh.: zuv (6) u > a: tribhuvan > tibhavan, Shambhu > Shambh, ashru > asra, kutah > katto, asur > asar, shatru > shatra, Visnu > vi,sn,a. Mod. Ksh.: ashru > osh, kutah > kati, shatru > shathir Vishnu > veshin

APPENDIX III

Abbreviations.

Skt. Sanskrit Pkt. Prakrit Ksh. Kashmiri Mod.Ksh. Modern Kashmiri IA Indo-Aryan OIA Old Indo-Aryan MIA Mid Indo-Aryan Panj. Panjabi Guj. Gujrati M.P. Mahanay Prakash B.K. Banasur Katha S.D.C. Sukha-Dukha Charit

1. Siddheshwal Verma, The Antiquities of Kashmiri: An Approach. p. 7. 2. See his Detailed Report of a Tour in Search of Sanskrit Manuscripts Made in Kashmir, Rajputana and Central Asia p. 89. 3. Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal, p. 280. 4. Tour in Search of Sanskrit Manuscripts, p. 83. 5. Monier Williams, Sanskrit Dictionary, p. 844. 6. The Antiquities of Kashmiri: An Approach, p. 4. 7. S.K. Toshkhani, "Some Important Aspects of Kashmiri as a Language", The Lala Rookh, August 1967, p. 50. 8. G.A. Grierson, "The Linguistic Classification of Kashmiri", Indian Antiquary XLIV, p. 257. 9. The Linguistic Survey of India Vol. VIII. Part II. p. 259. 10. S.K. Chatterji, Languages and Literatures of Modern India. p. 256. 11. The Lingusitic Survey of India Vol. VIII, Part IV: The Introduction p. 8. 12. Quoted by Murray B. Emenau in AnL VIII. No. 8, p. 282-83. 13. Ibid. 14. G.A. Grierson, The Linguistic Survey of India Vol. VIII, Part II, 251- 2. 15. See T. Grahame Bailey, Grammar of the Shina Language, Royal Asiatic Society, London, 1924. 16. Help has been taken of Turners' Comparative Dictionary of Modern Indo-Aryan Languages' for etymology of most of the words. 17. Siddheshwar Verma, The Antiquities of Kashmiri: An Approach, p. 5-6. 18. Beams, A Comparative Grammar of the Modern Languages of India. p. 291. 19. Tour in Search of Sanskrit Manuscripts, p. 86. 20. Ibid. p. 86. 21. G. A. Grierson, The Language of Mahanay Prakash, Para 274.

Your browser does not support iframes.

Greater Kashmir

Kashmiri Language: Essence & Culture

Language is what makes us human. it is how people communicate. by learning a language, it means you have mastered a complex system of words,….

Mohammad Hanief

Language is what makes us human. It is how people communicate. By learning a language, it means you have mastered a complex system of words, structure, and grammar to effectively communicate with others. To most people, language comes naturally.

We learn how to communicate even before we can talk and as we grow older, we find ways to manipulate language to truly convey what we want to say with words and complex sentences.

Of course, not all communication is through language, but mastering a language certainly helps speed up the process. This is one of the many reasons why language is important.

Language is one of the most important parts of any culture. It is the way by which people communicate with one another, build relationships, and create a sense of community. There are roughly 6,500 spoken languages in the world today, and each is unique in a number of ways.

Communication is the core component of any society, and language is an important aspect of that.

As language began to develop, different cultural communities put together collective understandings through sounds. Over time, these sounds and their implied meanings became commonplace and language was formed.

Intercultural communication is a symbolic process whereby social reality is constructed, maintained, repaired and transformed. As people with different cultural backgrounds interact, one of the most difficult barriers they face is that of language.

Language is an indispensable component of the culture of a nation or people. Language, rather culture, make the identity of a nation. The value systems of western society are different from the eastern society. Values are so deep rooted in societies that it is difficult to isolate or destabilize them.

The identity of Kashmiri people is their language, Kashur. Kashmiri is the mother tongue of more than one crore people of Jammu and Kashmir. Kashmiri is the language that is blossomed with one of the richest literatures in India.

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 has advocated that the medium of instruction is home language/mother tongue /local language/regional language for schools, until at least Grade 5, but preferably till Grade 8 and beyond.

All students will learn three languages in their school under the ‘formula’. Mother tongue use in worship is very essential in communicating the gospel to the deepest level.

About Kashmir and its core language, a recent entrant into the list of the official languages of Jammu and Kashmir, Kashmiri is a language from the Dardic subgroup of Indo-Aryan languages, spoken by about 50 % of the population of Jammu and Kashmir region.

Around 7 million Kashmiris in the Kashmir region speak this language, and it is among the 22 scheduled languages of India. Kashmiri is considered as one of the oldest languages used in the Indian subcontinent. It is widely considered as a Sanskrit language which sounds valid considering the fact that before its conversion to Islam, most of the Kashmir Valley was inhabited by Brahmins.

Kashmiri literature is as old as 750 years; this is the age of the emergence of many modern languages’ literatures such as English. It is one of the oldest spoken languages of India and the constitution of India has recognized it as an official language under Schedule-VIII.

The Kashmiri language has uniqueness of secularism and delicacy of communal harmony. It has the spiritual poetry of Nund Reshi and Lalleshwari (Lal Ded) which is brimmed with mysticism in effect and a true philosophy of life for all irrespective of region or religion.

Indo-European language family is native to western and southern Eurasia, consisting of languages of Europe, northern Indian subcontinent and the Iranian plateau. One of the branches of the Indo-European family is Indo-Iranian.

Indo-Aryan languages, also called Indic languages, are a branch of Indo-Iranian languages. Indo-Aryan languages are spoken by more than 800 million people, mainly in India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Nepal. There are more than 200 known Indo-Aryan languages. Dardic is a subgroup of these languages.

Dardic languages are spoken in Gilgit-Baltistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in Pakistan, some parts of Afghanistan, and in the Kashmir Valley and Chenab Valley in India. Kashmiri, Shina, Chitral, Kohistani, Pashayi and Kunar are the subfamilies of Dardic languages. The Kashmiri subfamily includes the languages Kashmiri, Kishtwari and Poguli.

Sanskrit influences can be easily seen in Kashmiri. When Muslims ruled Kashmir, the Kashmiri language borrowed many Persian words. In the recent years, Hindustani and Punjabi have influenced Kashmiri vocabulary. Three scripts are used in Kashmiri.

They include Perso-Arabic, Devanagari and Sharada. Roman script is also sometimes used. Since the 8th century AD, Kashmiri was written in the Sharada script. This script is not used today, except for religious ceremonies of Kashmiri Pandits.

Today, Perso-Arabic and Devanagari scripts are used, wherein Perso-Arabic is recognized as the official script of the Kashmiri language and it is used by Kashmiri Hindus and Kashmiri Muslims alike. Unlike other Indo-Aryan languages, many old features of the Old Indo-Aryan have been retained in the Kashmiri language.

Kashmiri has two dialects, namely, Kishtwari and Pogali. Kishtwai is a conservative dialect, used mostly in the Kishtwar Valley. Pogali is an Indo-Aryan language spoken in some parts of Jammu, and is intermediate between Kashmiri and Western Pahari.

Thus, we can see that Kashmiri is a very old and a rich language having its own unique characteristics due to which it stands out from other languages. Spoken by a majority of people in Jammu and Kashmir, Kashmiri got the special status of official language of Jammu and Kashmir in 2020. This decision was greeted by Kashmiris all across the world over and has served as an important step in promoting this language.

When one develops an interest in the Kashmiri language one is tempted to delve deep into history in order to get to know the origins of this ancient language. Least research rather scientific research is conducted and only few commentaries are provided in this direction to provide an empirical treatise with an inquisitive insight on the origin and development of Kashmiri language. The perspectives regarding the discourse of ‘power and language’, which George Orwell explicitly describes in ‘Power and English Language’, in case of Kashmiri language are naive if not absent.

Professor Rehman Rahi, a celebrated Kashmiri poet who devoted his life to promoting and preserving the Kashmiri language and gave its poetry a distinct identity, published more than a dozen books of poetry and prose in Kashmiri and is credited with restoring the language spoken by more than six million people to the realm of literature, lifting it out of the shadow of Persian and Urdu, which once dominated the literary scene in Kashmir.

In the 1950s, he attended a poetry reading session in the village of Raithan in central Kashmir, where a Kashmiri poem was greeted with tremendous applause. Rahi then went onstage and read his work in Urdu, then the region’s official language. That was the beginning of his long love affair with the language, which he described in his 1966 poem “Hymn to a Language”. He also promoted Kashmiri in more concrete ways. He was one of the biggest supporters of a campaign to restore the language to schools, an effort that finally succeeded in 2000. He helped recruit teachers and scholars to teach Kashmiri and created a course to teach it to children.

The evolution of its script and development of Kashmiri language is an important and interesting area of study. The role played by Sufis and Rishis in the development of Kashmiri language is also exemplary and must be documented.

(The author is a regular contributor. )

DISCLAIMER: The views and opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author.

The facts, analysis, assumptions and perspective appearing in the article do not reflect the views of GK.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Please enter an answer in digits: 17 + ten =

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Meet top uk universities from the comfort of your home, here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- School Education /

Essay on Kashmir: History and Beauty in 600+ Words

- Updated on

- Jan 20, 2024

Essay on Kashmir for Students: Kashmir is a region situated between India and Pakistan in South Asia. It is believed that the name Kashmir originated from the word ‘Ka’ which means water, and ‘shimera’ to desiccate.

The story of Kashmir is complex and has historical, cultural, and political dimensions. Over the years, many rulers and empires, like the Mauryas , Kushans , and Mughals have influenced the paradise of the Earth. The region especially had the special influence of Mauryan ruler Ashoka who contributed to the cultural as well as the architectural heritage of the region.

Cultural Diversity of Kashmir

Kashmir is a region that has a rich history and ancient roots. The place has witnessed the rise and fall of many dynasties, such as the Mauryas , Kushnas , and Guptas . On top of that, these dynasties contributed to the cultural and geographic location of Kashmir, which includes the influence of the Silk Road and the blend of Hindu, Buddhist, and later Islamic influences.

Kashmir Issue

The dispute related to the sharing of borders didn’t stop after Independence. Whether it was India, Pakistan, or China, tensions related to the disputes of the region always created a heat of fire between the countries that led to wars. The list of some important wars are as follows:

1. First Indo-Pak War (1947-1948) : Fought for Jammu Kashmir shortly after India’s independence.

2. Sino-Indian War (1962): A conflict between India and China for the territorial region Aksai Chin.

3. The War of (1965): Fought mainly over Kashmir.

4. Kargil War (1999): A conflict between India and Pakistan in the Kargil district of Jammu and Kashmir.

Article 370 Scrapped

Geographically, Kashmir lies in the northwestern region of the Indian continent. Its total area is around 225,000 square kilometers, which is comparatively larger than the member countries of the United States.

Out of the total area, 85,800 square kilometers have been subject to dispute between India and Pakistan since 1947. It is important to note that the areas with conflict consist of major portions called the Northern, Southern, and Southeastern portions. The 30 percent of the northern part comprises Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan and is administered by Pakistan.

India controls the portion which is more than 55 percent of the area of the land. The area consists of Jammu and Kashmir, Ladakh, Kashmir Valley, and Siachen Glacier which is located in the southern and southeastern portions of India. The area is divided by a line of control and has been under conflict since 1972.

Also Read: Speech on Article 370

Sadly, the people living near the International Border and the Line of Control (LoC) in Jammu and Kashmir pose not only a life threat but also do not have a stable life. Replacement and relocation affect the people living in the line of control not affect the people physically but also psychologically and socially aspects. In a survey conducted by the National Library of Medicine 94 percent of the participants recognize stress. Furthermore, the youth population was facing stress and anxiety regularly.

However, a historic decision from the Supreme Court of India that nullified Articles 370 and 35A and permitted the state to have its constitution, flag, and government except in defense, foreign affairs, and communications decisions. After the decision, many initiatives were taken by the government of India to strengthen the democratic rule of the state. Schools, colleges, and universities were opened regularly in the union territories to develop the youth academically, socially, and as well as physically.

Furthermore, strict measures to control criminal assaults such as stone pelting have started showing positive impacts on the continuance use of technologies such as mobile networks, and internet activities. Further, the discontinuity of Technology has started showing positive impacts on the lifestyle of people. Regular opening of schools, colleges, and universities, on the one hand, is helping the students to have good career prospects.

Additionally, the fear-free environment that further increases tourist activities will further improve the local economy and contribute to the local as well as the national economy of the country.

Also Read: Essay on Indian Independence Day

Kashmir is also called the Paradise on Earth. The region is blessed with natural beauty, including snow-capped mountains and green and beautiful valleys. The region is surrounded by two countries, which are Pakistan and China.

Kashmir is famous for Dal Lake, Pashmina Shawls, beautiful Mughal gardens and pilgrimage sites of Amarnath and Vaishno Devi.

According to a traditional story, Ka means water and shimira means Desiccate.

Kashmir is known as the ‘Paradise on Earth.’

Related Blogs

This was all about the essay on Kashmir. We hope this essay on Kashmir covers all the details for school students. For more information on such interesting topics, visit our essay writing page and follow Leverage Edu.

Deepika Joshi

Deepika Joshi is an experienced content writer with expertise in creating educational and informative content. She has a year of experience writing content for speeches, essays, NCERT, study abroad and EdTech SaaS. Her strengths lie in conducting thorough research and ananlysis to provide accurate and up-to-date information to readers. She enjoys staying updated on new skills and knowledge, particulary in education domain. In her free time, she loves to read articles, and blogs with related to her field to further expand her expertise. In personal life, she loves creative writing and aspire to connect with innovative people who have fresh ideas to offer.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Connect With Us

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today.

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

January 2024

September 2024

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Have something on your mind?

Make your study abroad dream a reality in January 2022 with

India's Biggest Virtual University Fair

Essex Direct Admission Day

Why attend .

Don't Miss Out

Kashmiri is the language of the Vale of Kashmir or the Kashmir Valley, as it is also known. It is an Indo-Aryan language with a rich literary history going as far back as the fourteenth century and is spoken by the majority of the inhabitants of this region of Kashmir and the neighboring district of Kishtwar, as well as by the diasporic Kashmiri community. Kashmiri is one of India’s official languages, recognized in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution of India, and is the official language of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Kashmiri is conventionally written in a modified form of the Perso-Arabic script. It also used to be written in a form of the Brahmi script called Sharada, however the use of this script has become extremely rare. Kashmiri is offered as a part of the department’s language tutorials according to the academic needs of students. Students who study Kashmiri can also take part in the American Institute of Indian Studies Kashmiri programs offered in the summer months.

Subject to FAS language tutorial guidelines; enrollment is by petition and statements of academic need are due by June 1, 2023. To submit a petition please use this link to the Language Tutorial Petition online form .

- Constructed scripts

- Multilingual Pages

Kashmiri (कॉशुर / كٲشُر )

Kashmiri is a member of the Dardic subgroup of the Indo-Aryan language family. In 2011 there were 6.7 million speakers of Kashmiri in India, and there were about 143,000 in Pakistan in 2016. In India it is spoken in the states of Jammu and Kashmir, and in Himachal Pradesh, especially in the Kashmir valley. In Pakistan it is spoken in Azad Kashmir province.

Kashmiri is also known as Cashmeeree, Cashmiri, Kacmiri, Kaschemiri, Keshur or Koshur.

Kashmiri first appeared in writing during the 8th century AD in the Sharda alphabet, which is still used in religious ceremonies by Kashmiri Pandits. After the arrival of Islam in Kashmir during the 15th century, the Arabic script was adapted to write Kashmiri. Today Kashmiri Muslims write their language with the Arabic script, and Kashmiri Hindus used the Devanagari alphabet.

Kashmiri is one of the official languages of India, and is taught in schools in the Kashmir valley. It is also used in literature, newspapers, on the radio, and in other media.

Arabic script for Kashmiri

Devanagari alphabet for kashmiri.

Sources: http://koshur.org/pdf/Let Us Learn Kashmiri.pdf and http://www.geocities.ws/michaelpeterfustumum/kashmiri_latin_alphabet.htm

Download an alphabet chart for Kashmiri (Excel)

Details provided by Biswajit Mandal (biswajitmandal[dot]bm90[at]gmail[dot]com)

Sample texts in Kashmiri

Source: http://www.kashmirilanguage.com/PDF's/Manikaman_1.pdf

IPA transcription

/səːriː insaːn t͡ʃʰi aːzaːd zaːmɨtʲ . wʲakaːr tɨ hokuːk t͡ʃʰi hiwiː . timan t͡ʃʰu soːt͡ʃ samad͡ʒ ataː karnɨ aːmut tɨ timan pazi bəːj baraːdəriː hɨndis d͡ʒazbaːtas tahat akʰ əkis akaːr bakaːr jun/

Transliteration

Sə̄rī insān čhi āzād zāmytj. Vjakār ty hokūk čhi hivī. Timan čhu sōč samaž atā karny āmut ty timan pazi bə̄i barādərī hyndis žazbātas tahat akh əkis akār bakār jun.

Transcription and transliteration by Sammy Silvers

Hear a recording of this text by Waqar Shah

Translation

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. (Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights)

Additions and amendments provided by Waqar Shah

Sample videos in Kashmiri

Information about Kashmiri | Phrases | Numbers

Information about Kashmiri http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kashmiri_language https://www.ethnologue.com/language/kas http://www.kashmirilanguage.com http://www.koshur.org/pdf/BasicReader.pdf http://www.koausa.org/Reader/intro.html

Kashmiri lessons http://www.koshur.org https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCeT7AmIHhzfP9bSGODIVYPA/videos https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCEKwZpQZZaAkvvFLF1i20pg

Online Kashmiri dictionary http://dsal.uchicago.edu/dictionaries/grierson/

Koshurakhbar - the online Kashmiri newspaper http://www.koshurakhbar.com

Dardic languages

Gawri , Indus Kohistani , Kalkoti , Kashmiri , Khowar , Palula , Sawi , Shina , Torwali

Languages written with the Devanāgarī alphabet

Aka-Jeru , Angika , Athpare , Avestan , Awadhi , Bahing , Balti , Bantawa , Belhare , Bhili , Bhumij , Bilaspuri , Bodo , Bhojpuri , Braj , Car , Chamling , Chhantyal , Chhattisgarhi , Chambeali , Danwar , Dhatki , Dhimal , Dhundari , Digaro Mishmi , Dogri , Doteli , Gaddi , Garhwali , Gondi , Gurung , Halbi , Haryanvi , Hindi , Ho , Jarawa , Jaunsari , Jirel , Jumli , Kagate , Kannauji , Kham , Kangri , Kashmiri , Khaling , Khandeshi , Kharia , Khortha , Korku , Konkani , Kullui , Kumaoni , Kurmali , Kurukh , Kusunda , Lambadi , Limbu , Lhomi , Lhowa , Magahi , Magar , Mahasu Pahari , Maithili , Maldivian , Malto , Mandeali , Marathi , Marwari , Mewari , Mundari , Nancowry . Newar , Nepali , Nimadi , Nishi , Onge , Pahari , Pali , Pangwali , Rajasthani , Rajbanshi , Rangpuri , Sadri , Sanskrit , Santali , Saraiki , Sirmauri , Sherpa , Shina , Sindhi , Sunwar , Sylheti , Tamang , Thakali , Thangmi , Wambule , Wancho , Yakkha , Yolmo

Languages written with the Arabic script

Adamaua Fulfulde , Afrikaans , Arabic (Algerian) , Arabic (Bedawi) , Arabic (Chadian) , Arabic (Egyptian) , Arabic (Gulf) , Arabic (Hassaniya) , Arabic (Hejazi) , Arabic (Lebanese) , Arabic (Libyan) , Arabic (Modern Standard) , Arabic (Moroccan) , Arabic (Najdi) , Arabic (Syrian) , Arabic (Tunisian) , Arwi , Äynu , Azeri , Balanta-Ganja , Balti , Baluchi , Beja , Belarusian , Bosnian , Brahui , Chagatai , Chechen , Chittagonian , Comorian , Crimean Tatar , Dargwa , Dari , Dhatki , Dogri , Domari , Gawar Bati , Gawri , Gilaki , Hausa , Hazaragi , Hindko , Indus Kohistani , Kabyle , Kalkoti , Karakalpak , Kashmiri , Kazakh , Khowar , Khorasani Turkic , Khwarezmian , Konkani , Kumzari , Kurdish , Kyrgyz , Lezgi , Lop , Luri , Maguindanao , Malay , Malay (Terengganu) , Mandinka , Marwari , Mazandarani , Mogholi , Morisco , Mozarabic , Munji , Noakhailla , Nubi , Ormuri , Palula , Parkari Koli , Pashto , Persian/Farsi , Punjabi , Qashqai , Rajasthani , Rohingya , Salar , Saraiki , Sawi , Serer , Shabaki , Shina , Shughni , Sindhi , Somali , Soninke , Tatar , Tausūg , Tawallammat Tamajaq , Tayart Tamajeq , Torwali , Turkish , Urdu , Uyghur , Uzbek , Wakhi , Wanetsi , Wolof , Xiao'erjing , Yidgha

728x90 (Best VPN)

Why not share this page:

If you like this site and find it useful, you can support it by making a donation via PayPal or Patreon , or by contributing in other ways . Omniglot is how I make my living.

Get a 30-day Free Trial of Amazon Prime (UK)

If you're looking for home or car insurance in the UK, why not try Policy Expert ?

- Learn languages quickly

- One-to-one Chinese lessons

- Learn languages with Varsity Tutors

- Green Web Hosting

- Daily bite-size stories in Mandarin

- EnglishScore Tutors

- English Like a Native

- Learn French Online

- Learn languages with MosaLingua

- Learn languages with Ling

- Find Visa information for all countries

- Writing systems

- Con-scripts

- Useful phrases

- Language learning

- Multilingual pages

- Advertising

Kashmiri language is an Indo-Aryan language with its core vocabulary drawn from 'proto-Sanskrit' and 'Sanskrit'. Kashmir has been a seat of highest learning in South and Central Asia for several centuries. Shaivism and Buddhism, the major religions, flourished in this area. The 14th century paved the way for Islam Invaders into the valley, which in turn resulted in the increase in Muslim population. The oldest record of Kashmiri language dates back to the 9th century, when poetry of Chumma Sampraday was in vogue. The followers of this sect wrote verses in old Kashmiri or Apabhramsa. This is followed by Shitikanth’s Mahanaya Prakash, which is a philosophical work on Kashmir Shaivism. Its language is similar to that of Chumma pads. Avtar Bhat in Banasurvadh katha of 15th century employed old Kashmiri and the same was followed by Ruupa Bhawani in her verses which owes its origin to 17th century. But Laleshwari in the 14th century and her disciple Nund Rishi alias Sheikh-ul-Alam used common man’s language in their poetry, which are the first attested forms of modern Kashmiri. In the 16th and 18th centuries, Habba khatoon alias Zoon and Arnimaal employed modern Kashmiri in their love songs.

From the 14th century onwards- Sufi poetry brought in a large body of Perso-Arabic lexis into the language, which eventually enriched the Kashmiri language.

In the 20th-21st centuries devotional songs, love songs, modernist poetry , short stories, plays, essays, novels and other literary genres enriched the language further.

It was during the 14th century that Laleshwari, the first modern Kashmiri poetess provided the native tongue to Kashmir Shaivism. Her hymns (Vak h ) are the first attested poetic rendering in Kashmiri language. Persian gradually made its way into the king’s court and Islam spread to remote villages. Consequently, Perso-Arabic vocabulary made its way into the native tongue. Kashmiri, thus, has borrowed extensively from Persian and Arabic and its vocabulary is rich with synonyms, antonyms, idioms and proverbs drawn from these sources.

Linguistic studies of the language began in the 19th century when European scholars studied and analyzed indigenous languages and cultures. Edgworth (1841), Leech(1844) did the pioneering work with regard to Kashmiri. However, the first descriptive grammar of Kashmiri was prepared by Ishwara Kaula. His Kashmirashabdamrita is the first Kashmiri grammar written in Sanskrit in 1879. It is written in the Paninian grammatical format. George A. Grierson calls it ‘an excellent grammar of Kashmiri’. Based upon this work, Grierson published his Standard Manual of Kashmiri Language in 1911. He has given a sketch of kashmiri grammar in his monumental Linguistic Survey of India, Vol.8, Part 2 (1919).

Braj B. Kachru’s Reference Grammar of Kashmiri published from the University of Illinois, USA in 1969 was followed by a host of scholars who worked out various aspects of the language.

Omkar N. Koul, Kashi Wali, Peter E.Hook, Roop Krishen Bhat, Boris Zakharyan etc. have published books and articles on various aspects of Kashmiri phonology, morphology and syntax. They have also prepared a series of teaching materials in the language. Somnath Raina, M.L.Sar, J.L. Handoo, Lalita Handoo, Rakesh Mohan Bhatt, Achala Misri Raina, Ashok Koul, Satyabhama Razdan, R.L.Talashi, Raj Nath Bhat, Vijay Koul, Maharaj Koul, Adil Kak, Shafi Shauk, Nazir Dar, A. Indrabi etc. are the other scholars who have made notable contribution to the study of Kashmiri language.

Various attempts have been made, from the early 19 th century, to present grammars and grammatical studies related to different aspects of Kashmiri. The grammatical literature of Kashmiri comprises a variety of materials written in the form of brief notes, articles, monographs, dissertations and independent grammatical sketches and grammars. A Brief survey of some of the prominent works is presented below.

Some of the earlier works on Kashmiri grammar are important and deserve attention of scholars. They include Edgeworth (1841) and Leech (1844). Leech is a first complete sketch of Kashmiri grammar, written by an European scholar, from pedagogical point of view.

A first serious attempt was made by Ishvara Kaul to present a complete grammatical description of Kashmiri in his Kashmira Shabdamritam (Grammar of Kashmiri Language) written in Sanskrit in 1879. This grammar was edited by George A. Grierson and published by the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1889.

Grierson describes this work as 'an excellent grammar of Kashmiri'. This book is now available in a new edition with Hindi translation by Anatan Ram Shastri (Delhi, 1985).

Grierson has contributed to Kashmiri by his numerous works. He has written articles entitled On pronominal suffixes in the Kashmiri language, (JASB, Vol. 64, No.1), On secondary suffixes in Kashmiri (JASB Vol. 67, No.1), based on the work of Ishvara Kaul. Grierson has also written Standard manual of the Kashmiri language (2 Volumes) comprising grammar, English-Kashmiri sentences and Kashmiri-English vocabulary.

This was originally published in Oxford in 1911 and reprinted by Light and Life Publishers, Rohtak in 1973. It presents a brief grammatical sketch of Kashmiri. He has also provided a brief grammatical sketch of Kashmiri in his Linguistic Survey of India (originally) published in 1919), Vol 8, Part 2.

Burkhand (1887-1889) has written on different grammatical aspects of Kashmiri in German. Some of his works have been translated into English by Grierson. Grierson’s articles on different aspects of Kashmiri linguistics published earlier were also published in a book form under the title Essays on Kashmiri language in 1899 in the present Kolkata.

It is only for the last three decades or so that some serious work on grammatical studies in Kashmiri has been carried out. This work is available in the form of research articles, dissertations and independent grammatical sketches or grammars. Trissal’s doctoral dissertation (1964) provides a first descriptive grammar of Kashmiri written in Hindi. It describes Kashmiri phonology, morphology and syntax in the traditional descriptive framework.

Kachru (1969) provides a detailed grammatical description of Kashmiri. This grammar contains an introduction and chapters dealing with phonetics, phonology, word formation, word clauses, the noun phrase, the verb phrase, the adverbial phrase, and sentence types. It is the first attempt at a comprehensive treatment of Kashmiri. It is mimeographed and has a very limited circulation. Kachru (1968) provides a description of some syntactic and semantic aspects of copula verb in Kashmiri. His Kashmiri and other Dardic language (In Sebeok(ed), Current trends in linguistics Vol. 5. The Hague : Mouton), mainly reviews earlier classifications of Kashmiri and other Dardic languages and mentions some linguistic characteristics of Kashmiri. Another important work of Kachru (1973) primarily contains lessons for learning Kashmiri as a second or foreign language. It has grammatical and cultural notes on Kashmiri. He has elaborated the discussion of various grammatical aspects which was done by him earlier. This book also has a limited circulation.

Koul (1977) provides a first detailed description of certain morphological and syntactic aspects of the Kashmiri language. It has chapters on the noun phrase, the adjective phrase, the auxiliary, the verb phrase, questions, coordinate conjunction, reduplication, kinship terms and lexical borrowings. Koul (1985, 1987) provides description of all the basic grammatical structures of Kashmiri along with lessons. These courses have been prepared and are being used for teaching Kashmiri as a second language to in-service teachers at the Northern Regional Language Centre, Patiala, and also to the civil service officers at the LBS National Academy of Administration, Mussoorie.

So far, two grammars on Kashmiri, have been written by Naji Munawar and Shafi Shauq (1976), and Nishat Ansari(1979). Both these grammars provide a very brief description of traditional grammatical terms in Kashmiri. Their main contribution has been in introducing Kashmiri terms for the traditional grammatical terms used in Urdu.

A few doctoral dissertations submitted to various universities are devoted to different grammatical aspects of Kashmiri. R.K. Bhat’s doctoral dissertation (1980) now published in book-form (1986) describes phonology and morphology of Kashmiri in detail. Mohan Lal Sar 1981) describes verbal inflections of Kashmiri in detail. Sushila Sar (1977) critically examines the description of the Kashmiri language as made by Ishvar Kaul. Raj Nath Bhat (1981) describes pragmatic aspects of Kashmiri. Maharaj Krishen Koul’s dissertation (1982) now available in book form (1986) provides description on certain grammatical aspects of Kashmiri. Andrabi (1984) presents description of reference and co-reference in Kashmiri. Dar (1984) provides the discussion of certain phonological and grammatical aspects of Kashmiri spoken in the district of Baramulla in the Kashmir valley and makes comparison of certain grammatical characteristics of Kashmiri from sociolinguistic point of view. Vijay Kumar Koul (1985) attempts to provide the description of compound verbs in Kashmiri. Kartoo (1985) provides the contrastive study of certain grammatical features with special reference to certain minority languages of Kashmiri. Somnath Raina’s dissertation (1985) now available in print form (1990) has discussed pedagogical problems in the teaching of Kashmiri as a second language. Rakesh Mohan Bhatt (1994) has worked on Word Order and Case in Kashmiri with comprehensive details. As may be seen from the titles and contents of these dissertations, various grammatical aspects related to Kashmiri have attracted the attention of research scholars. Most of these dissertations are unpublished. The topics dealt by the researchers have been pursued by other scholars as well.

Besides various dissertations completed on various aspects of Kashmiri, the scholars have independently worked on various grammatical aspects of Kashmiri following different theoretical frameworks. Most of these works are published in different journals or are compiled in certain volumes devoted to linguistic studies of Kashmiri. These papers raise various significant issues and seek solutions to various problems. Hook (1976) has argued for V2 word order for Kashmiri. This paper has generated great interest among various scholars who chose to discuss the word order of Kashmiri in their works. Certain works have supported the argument. Koul and Hook have co-edited a volume on Kashmiri (1984) which includes research articles on different grammatical aspects of Kashmiri.

Wali and Koul (1997) have provided a detailed description of Kashmiri grammar covering syntax, morphology, phonology etc. The syntax is dealt in detail. Hook and Koul (2001) also dealt with various syntactic aspects. Most of the earlier works on Kashmiri are out of print and are not easily available, they need to be reprinted. There is no comprehensive or pedagogical grammar of Kashmiri to cater to the needs of the second language learners of the language.

Linguistic Classification

The Kashmiri language is primarily spoken in the Kashmir valley of the state of Jammu & Kashmir in India. It is called kA:shur or kA:shir zaba:n by its native speakers and the valley is called kAshi:r. As per the census figures of 1981 there were 30,76,398 native speakers of the language. No census was conducted in 1991.

Grierson has placed Kashmiri under the Dardic group of languages. He has classified Dardic languages under three major groups: 1. The Kafir Group, 2. The Khowar or Chitrali Group and 3. The Dard Group. According to his classification the Dard Group includes Shina, Kashmiri, Kashtawari, Poguli, Siraji, Rambani and Kohistani – the last comprising Garwi, Torwali and Maiya. Grierson considered the Dardic languages to be a sub-family of the Aryan languages "neither of Indian nor or Iranian origin, but (forming) a third branch of the Aryan stock, which separated from the parent stem after the branching forth of the original of the Indian languages, but before the Iranian languages had developed all their peculiar characteristics" (1906:4). He has further observed that ‘Dardic’ is only a geographical convention. Morgenstierne (1961) has placed Kashmiri under the Dardic Group of Indo-Aryan languages along with Kashtawari and other dialects, which are strongly influenced by Dogri. Fussman (1972) has based his work on that of Morgenstierne’s classification. He has also emphasized that the Dardic is a geographic and not a linguistic expression. According to Chatterjee (1963:256) Kashmiri has developed like other Indo-Aryan languages out of the Indo-European family of languages and is to be considered as a branch of Indo-Aryan like Hindi, Punjabi etc. There has been little linguistically oriented dialect research on Kashmiri.

Dialects are of two types : (a) Regional dialect, and (b) Social dialect. Regional dialects are of two types (1) those regional dialects or variations which are spoken within the valley of Kashmir, and (2) those which are spoken in the regions outside the valley of Kashmir.

Kashmiri speaking area in the valley of Kashmir is divided into three regions: (1) Maraz (southern and south eastern region), 2. Kamraz (northern) and northern-western region), and 3. Srinagar and its neighboring areas. There are some minor linguistic variations in Kashmiri spoken in these areas. The main variations are, being phonological and the usage of certain vocabulary items.

Since Kashmiri spoken in Srinagar has gained some social prestige, very frequent style switching takes place from Marazi or Kamarazi styles to the style of speech spoken in Srinagar. This phenomena of 'style switching' is very common among the educated speakers of Kashmiri. Kashmiri spoken in Srinagar and surrounding areas continues to hold the prestige of being the standard variety and is used in education, mass media and literature.

Copyright CIIL-India Mysore

essay on my school in kashmiri language

- essay analysis

- essay examples

- essay format

- essay online

- essay samples

- essay template

Essay on Kashmir in English 100, 200, 300, 500 Words PDF

Essay on kashmir.

Short & Long Essay on Kashmir – The essay on Kashmir has been written in simple English and easy words for children and students. This English essay mentions Kashmir its beautiful land and places, Why is Kashmir beautiful? What are the challenges to the beauty of Kashmir, and why everyone should go and discover it? Students are often asked to write essay on Kashmir in their schools and colleges. If you are also looking for the same, then we have given essays on this topic in 100-word, 200-word, 300-word, and 500-word.

Short & Long Essay on Kashmir

Essay (100 words).

Kashmir is a beautiful state of India and is considered the most important part of India which is called heaven on earth, it is said that there is no place more beautiful than Kashmir, it is also called Switzerland of India.

The capital of Jammu and Kashmir is Srinagar. There are many high Himalayan peaks, glaciers, valleys, rivers, evergreen forests, hills, etc., and many other places. Snowfall occurs throughout the year in Kashmir.