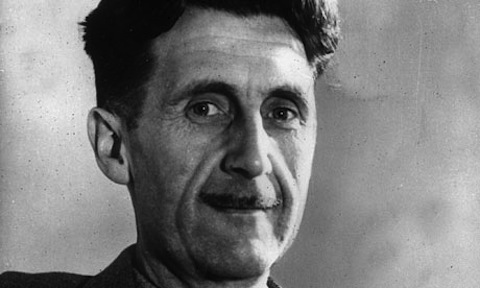

- About George Orwell

- Partners and Sponsors

- Accessibility

- Upcoming events

- The Orwell Festival

- The Orwell Memorial Lectures

- Books by Orwell

Essays and other works

- Encountering Orwell

- Orwell Live

- About the prizes

- Reporting Homelessness

- Enter the Prizes

- Previous winners

- Orwell Fellows

- Introduction

- Enter the Prize

- Terms and Conditions

- Volunteering

- About Feedback

- Responding to Feedback

- Start your journey

- Inspiration

- Find Your Form

- Start Writing

- Reading Recommendations

- Previous themes

- Our offer for teachers

- Lesson Plans

- Events and Workshops

- Orwell in the Classroom

- GCSE Practice Papers

- The Orwell Youth Fellows

- Paisley Workshops

The Orwell Foundation

- The Orwell Prizes

- The Orwell Youth Prize

- The Orwell Council

The Orwell Foundation is delighted to make available a selection of essays, articles, sketches, reviews and scripts written by Orwell.

This material remains under copyright in some jurisdictions, including the US, and is reproduced here with the kind permission of the Orwell Estate . All queries regarding rights should be addressed to the Estate’s representatives at A. M. Heath literary agency.

The Orwell Foundation is an independent charity – please consider making a donation to help us maintain these resources for readers everywhere.

Sketches For Burmese Days

- 1. John Flory – My Epitaph

- 2. Extract, Preliminary to Autobiography

- 3. Extract, the Autobiography of John Flory

- 4. An Incident in Rangoon

- 5. Extract, A Rebuke to the Author, John Flory

Essays and articles

- A Day in the Life of a Tramp ( Le Progrès Civique , 1929)

- A Hanging ( The Adelphi , 1931)

- A Nice Cup of Tea ( Evening Standard , 1946)

- Antisemitism in Britain ( Contemporary Jewish Record , 1945)

- Arthur Koestler (written 1944)

- British Cookery (unpublished, 1946)

- Can Socialists be Happy? (as John Freeman, Tribune , 1943)

- Common Lodging Houses ( New Statesman , 3 September 1932)

- Confessions of a Book Reviewer ( Tribune , 1946)

- “For what am I fighting?” ( New Statesman , 4 January 1941)

- Freedom and Happiness – Review of We by Yevgeny Zamyatin ( Tribune , 1946)

- Freedom of the Park ( Tribune , 1945)

- Future of a Ruined Germany ( The Observer , 1945)

- Good Bad Books ( Tribune , 1945)

- In Defence of English Cooking ( Evening Standard , 1945)

- In Front of Your Nose ( Tribune , 1946)

- Just Junk – But Who Could Resist It? ( Evening Standard , 1946)

- My Country Right or Left ( Folios of New Writing , 1940)

- Nonsense Poetry ( Tribune , 1945)

- Notes on Nationalism ( Polemic , October 1945)

- Pleasure Spots ( Tribune , January 1946)

- Poetry and the microphone ( The New Saxon Pamphlet , 1945)

- Politics and the English Language ( Horizon , 1946)

- Politics vs. Literature: An examination of Gulliver’s Travels ( Polemic , 1946)

- Reflections on Gandhi ( Partisan Review , 1949)

- Rudyard Kipling ( Horizon , 1942)

- Second Thoughts on James Burnham ( Polemic , 1946)

- Shooting an Elephant ( New Writing , 1936)

- Some Thoughts on the Common Toad ( Tribune , 1946)

- Spilling the Spanish Beans ( New English Weekly , 29 July and 2 September 1937)

- The Art of Donald McGill ( Horizon , 1941)

- The Moon Under Water ( Evening Standard , 1946)

- The Prevention of Literature ( Polemic , 1946)

- The Proletarian Writer (BBC Home Service and The Listener , 1940)

- The Spike ( Adelphi , 1931)

- The Sporting Spirit ( Tribune , 1945)

- Why I Write ( Gangrel , 1946)

- You and the Atom Bomb ( Tribune , 1945)

Reviews by Orwell

- Anonymous Review of Burmese Interlude by C. V. Warren ( The Listener , 1938)

- Anonymous Review of Trials in Burma by Maurice Collis ( The Listener , 1938)

- Review of The Pub and the People by Mass-Observation ( The Listener , 1943)

Letters and other material

- BBC Archive: George Orwell

- Free will (a one act drama, written 1920)

- George Orwell to Steven Runciman (August 1920)

- George Orwell to Victor Gollancz (9 May 1937)

- George Orwell to Frederic Warburg (22 October 1948, Letters of Note)

- ‘Three parties that mattered’: extract from Homage to Catalonia (1938)

- Voice – a magazine programme , episode 6 (BBC Indian Service, 1942)

- Your Questions Answered: Wigan Pier (BBC Overseas Service)

- The Freedom of the Press: proposed preface to Animal Farm (1945, first published 1972)

- Preface to the Ukrainian edition of Animal Farm (March 1947)

External links are being provided for informational purposes only; they do not constitute an endorsement or an approval by The Orwell Foundation of any of the products, services or opinions of the corporation or organisation or individual. The Foundation bears no responsibility for the accuracy, legality or content of the external site or for that of subsequent links. Contact the external site for answers to questions regarding its content.

We use cookies. By browsing our site you agree to our use of cookies. Accept

“Politics and the English Language.” By George Orwell.

LITERATURE MATTERS

In his 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language,” George Orwell poses a thoughtful question: Does language experience “natural growth” or is it shaped “for our own purposes”? In other words, does the English language organically evolve over time or is it purposefully manipulated in order to affect the social order? Anyone familiar with Orwell’s body of work can probably guess at the trajectory of his response. Although one could argue that this seminal essay on 20th-century linguistics was written merely to lament the “general collapse” of language as a reflection of the general collapse of civilization following the Second World War, Orwell’s ultimate purpose is to show that social activists can unduly manipulate language for their own ends by obscuring meaning, corrupting thought, and rendering language a minefield in the political landscape. Why? Orwell says: to effect changes in thought and affections and to shame those who somehow prove impervious to manipulation.

Orwell dramatizes this assertion in Nineteen Eighty-Four . Published three years after “Politics and the English Language,” the iconic dystopic novel imagines a futuristic government that manipulates language so that its citizens conform in thought, word, and deed to a narrow political orthodoxy. Language, in fact, is the primary change agent, assisted by government-engineered fearmongering and savage punishments for language dissidents.

Just as language matters in the world of Nineteen Eighty-Four , it matters in our world too. Consider, for example, the basics of “inclusive language.” Back when Orwell was writing, and throughout much of the 20th century, the accepted universal singular pronouns were he , him , and his , a reality codified in every English grammar text published before 1999. These pronouns referred to any individual, whether male or female, as in “Every student should bring his book to class.” The meaning was clear, the convention was understood, and because it was an accepted grammatical convention, no one was denounced as sexist for applying its usage. Some years later, in an effort to be “inclusive,” language handlers in academia and the publishing industry pointed out that the convention itself was sexist and reinforced sexism in society. If they could change the convention, they reasoned, they could change society.

The language handlers first promoted the alternative “inclusive” usage of he or she , him or her , and his or hers — and soon thereafter demanded it. Those who continued using traditional grammatical constructions that included the universal pronouns he , him , and his (especially men) were often branded, on the basis of their grammar alone, as sexists. But mere social stigma later gave way to punitive actions. For example, in 2013, California State University, Chico, revised its definition of sexual harassment and sexual violence to include “continual use of generic masculine terms such as to refer to people of both sexes.” Thus, Chico profs who say, “Every student should bring his book to class” are susceptible to disciplinary actions, up to and including dismissal. As you might imagine, Chico is not alone in this. Rather, this is the norm on most college campuses.

But now, in 2020, it is no longer acceptable to use he or she or him or her . What was once promoted and then demanded by language handlers as inclusive has now been deemed verboten by the same people! Who are these language handlers? In brief, they are the engineers of the English-language style manuals used by academia, the media, and the publishing industry, all easy prey to special-interest lobbyists who demand language changes to promote their sociopolitical agendas. Last year, for example, the American Psychological Association (APA) announced a change to its stylebook, advocating for the singular they because it is “inclusive of all people and helps writers avoid making assumptions about gender.” The APA style guide makes it clear that using his or her is no longer inclusive and no longer acceptable. This could not have happened without the proponents of transgenderism pushing for the manipulation of language. In order for the APA’s statement to make any sense — “they…is inclusive of all people and helps writers avoid making assumptions about gender” — one is forced to accept the premises of transgenderism, including the theory of so-called nonbinary gender. If one is to accept the usage of the singular they , one must also accept the fantasy that an infinite number of genders exists and that language is tied to something called “gender expression” rather than to sex, which is binary (i.e., male and female).

In 2018 the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) released a “Statement on Gender and Language,” promoting the use of the singular they as the only inclusive universal pronoun. In its position statement, the NCTE actually spells out the premises one must accept in order to make sense of the singular they . This is not about language clarity or precision; this is about advancing a sociopolitical agenda that requires everyone — yes, everyone — to accept the following terms:

Gender identity: an individual’s feeling about, relationship with, and understanding of gender as it pertains to their sense of self. An individual’s gender identity may or may not be related to the sex that individual was assigned at birth.

Gender expression: external presentation of one’s gender identity, often through behavior, clothing, haircut, or voice, which may or may not conform to socially defined behaviors and characteristics typically associated with being either masculine or feminine.

Cisgender: of or relating to a person whose gender identity corresponds with the sex they were assigned at birth.

Transgender: of or relating to a person whose gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth. This umbrella term may refer to someone whose gender identity is woman or man, or to someone whose gender identity is nonbinary (see below).

Nonbinary: of or relating to a person who does not identify, or identify solely, as either a woman or a man. More specific nonbinary identifiers include but are not limited to terms such as agender and gender fluid (see below).

Gender fluid: of or relating to individuals whose identity shifts among genders. This term overlaps with terms such as genderqueer and bigender, implying movement among gender identities and/or presentations.

Agender: of or relating to a person who does not identify with any gender, or who identifies as neutral or genderless.

The NCTE, like the APA, the Chicago Manual of Style , and the Associated Press, not only advocates using the singular they , it also prohibits “using he as a universal pronoun” and “using binary alternatives such as he/she , he or she , or (s)he .” And, in case you don’t understand the prohibition, the NCTE provides an example of the forbidden “exclusionary (binary)” language: “Every cast member should know his or her lines by Friday” must be rephrased as “Every cast member should know their lines by Friday.” But the new convention presents an offense against the dignity of traditional grammar usage, as the plural pronoun, their, does not agree with its singular subject, cast member . (Really now, a simpler rewrite would render the sentence both grammatically correct and “inclusive”: All cast members should know their lines by Friday .) And, according to NCTE, in the case of a student named Alex, who declares that his preferred pronouns are they , them , and their, a teacher should say, “Alex needs to learn their lines by Friday.” Yes, seriously, this is the example given by the NCTE. (And whose lines, one may ask? Everyone’s lines? This phrasing is lacking in precision and clarity, and this from the organization that exerts enormous influence over our nation’s high-school English teachers!) To be sure, teachers and students will be forced to utter the ridiculous: Alex needs to learn their lines by Friday . Failing to do so could, in the near future, be construed as gender harassment and be cause for expulsion or sacking.

So, why does it matter what the APA or the Chicago Manual of Style or the NCTE has to say on the matter of nonbinary, gender-inclusive language and the singular they ? Well, the APA sets the writing style and format conventions for academic essays for many college and high-school students, as well as for scholarly articles and books. The Chicago Manual of Style (published by the University of Chicago) sets the editorial standards and conventions that are widely used in the publishing industry. And the NCTE, as mentioned above, sets the tone for high-school English teachers across the nation, those who will teach our children to read, write, and speak.

In “Politics and the English Language,” Orwell calls this “an invasion of one’s mind” — again, the purposeful manipulation of language in order to corrupt one’s thoughts and affections. Thus, the choice of academia, the media, and the publishing industry to adopt the singular they is not simply about word choice — as silly and illogical as it may be: Alex needs to learn their lines by Friday! — it is about forcing students and others to accept the language of transgenderism and the ideological corollaries behind the vocabulary. It is asking us all to accept something that is less than reality. Pronouns, we are told, are no longer related to the body (male and female) but to the mind, how one “identifies” or “expresses” the social construct of gender. Reality is denied, and the fluid world of one’s nonbinary fancy replaces it.

It is worth noting that last year the Vatican’s Congregation for Catholic Education published a 30-page document, “Male and Female He Created Them,” on this very topic. Quoting Pope Francis, it explains that gender theory “denies the difference and reciprocity in nature of a man and a woman and envisages a society without sexual differences, thereby eliminating the anthropological basis of the family.” This ideology, Pope Francis explains, promotes “a personal identity and emotional intimacy radically separated from the biological difference between male and female. Consequently, human identity becomes the choice of the individual, one which can also change over time.” Thus, in the case of the Catholic educator or the Catholic student, one must compromise one’s religious principles in order to conform to the industry standards of language.

This attempt to transplant pronouns from the body to the mind, Orwell might say, is an attempt to destroy our ability to communicate. According to this new norm, one can now choose from a multitude of “gender identities” — or simply make up a new one — none of which has any fixed link to a specific set of pronouns. (Some recently emerging gender pronouns include zir, ze, xe, hir, per, ve, ey, hen , and thon . And there are more! Facebook, for example, offers 50 options. Fifty!) In fact, following this reasoning, gender expressionists may, at any time and for any reason, decide to change their preferred personal pronouns but without changing their gender identity; they may also decide to change their gender identity without changing their preferred pronouns — or they may choose to change both.

This is the kind of linguistic pretension that, as Orwell warns, obscures meaning, corrupts thought, and renders language a minefield in the political landscape. Why a minefield? As Orwell illustrated in Nineteen Eighty-Four , language-engineering is an attempt to shame or punish those who disagree with the ascribed linguistic orthodoxy. And, again, to what end? As Chicago-based community activist Saul Alinsky famously wrote in his manifesto Rules for Radicals (1971), “He who controls the language controls the masses.” (Note his use of “sexist language” by way of the universal singular pronoun he. ) Alinsky, an enthusiastic advocate of manipulating language for political purposes, agrees with Orwell: It’s all about thought control; it’s about superimposing a sociopolitical ideology on the masses; it’s about altering our understanding of the world; it’s about customizing the language to effect whimsical social change. It’s ultimately about altering reality so that, as Orwell dramatized in Nineteen Eighty-Four , we come to accept that “war is peace,” that “freedom is slavery,” and that two plus two equals five.

Orwell, as evidenced by “Politics and the English Language,” believes that language should reflect reality. If it doesn’t, what possible limits could be placed on misleading, manipulative language, whether in grade-school textbooks, government documents, or political campaign literature? If language is “always evolving,” as many commentators have reasoned in their recent support of so-called nonbinary, gender-inclusive language (including the singular they ), what is stopping anyone from using this as an excuse to effect any change in any language for any reason at any time?

©2020 New Oxford Review. All Rights Reserved.

To submit a Letter to the Editor, click here: https://www.newoxfordreview.org/contact-us/letters-to-the-editor/

Enjoyed reading this?

READ MORE! REGISTER TODAY

Choose a year

- Language & Its Destruction

- Literature & Literary Criticism

- Literature Matters by Michael S. Rose

- Political Correctness

- Transgenderism & Conflation of the Sexes

"Catholicism's Intellectual Prizefighter!"

- Karl Keating

Strengthen the Catholic cause.

SUPPORT NOR TODAY

You May Also Enjoy

Hillary Rodham Clinton may need the assistance of a spirit-guide to invoke the ghost of…

The reservation of the priesthood to men is not a matter of "discipline" or Church law that may be rescinded but is "theologically certain" and a "doctrine of faith."

The NEW OXFORD REVIEW is over 20 years old now, and we’ve always operated on…

George Orwell's 'Politics and the English Language'

George Orwell published his famous essay "Politics and the English Language" in 1946, and we mostly wish he hadn't.

Hosted by Emily Brewster, Ammon Shea, and Peter Sokolowski.

Produced in collaboration with New England Public Media.

Download the episode here .

Emily Brewster: Coming up on Word Matters, things get Orwellian in the narrowest sense of the word. I'm Emily Brewster, and Word Matters is produced by Merriam-Webster in collaboration with New England Public Media. On each episode, Merriam-Webster editors Ammon Shea, Peter Sokolowski, and I explore some aspect of the English language from the dictionary's vantage point. In 1946, George Orwell published his now-famous essay, "Politics and the English Language." Ammon sincerely wishes he hadn't.

Ammon Shea: One of the questions I feel like when you work in dictionaries that you often get from people, is that people always want to know what words are there that you hate, or that one hates or would banish from the language, and what words do you like. I feel like most lexicographers I know are pretty studious in trying to avoid having favorites or certainly about having dis-favorite words. But what I do have a distaste for is writings about words. My least favorite words are just peeves about language. I have to say perhaps foremost among my personal peeves is a piece of writing that is beloved by many. I like to think this is not just my contrarian nature that makes it so despised by me. It's that I think it's a bad piece of writing. I am speaking, of course, of George Orwell's "Politics and the English Language." Have you two feelings on this?

Peter Sokolowski: I've only just read it recently. It's one of those things that is referred to so frequently. I'm embarrassed to say, I don't think I ever studied it in school, so I took some of it kind of secondhand, for granted, the way lots of intellectual movements, someone didn't have to study Derrida to know what deconstruction is or to at least know that word is used often by other people. So I often took this to be a reference to the idea that politicians use words in a deliberately manipulative way. So I took it not as a linguistic document at all, but as a more philosophical or a political idea. I usually saw it in the context of names of political parties or movements or laws, something like the Clean Air Act, which I think was criticized for also helping fossil fuels. So people said, "Well, that's Orwellian," because you call it one thing but you really mean something else. So I interpreted it in that very filtered way through the culture.

Emily Brewster: I think I read it about five years after I read ) Animal Farm , so Animal Farm , eighth grade; freshman year of college maybe, "Politics and the English Language." I think I loved them both and believed them both completely. Thought they were just both absolutely brilliant. I didn't actually read this 1946 essay again until last night. I see some problems with Orwell's assertions at this stage, but I can also defend some of them, so.

Ammon Shea: Okay, great. What is this if not an argument. As you pointed out, it was published in 1946. It came out in the journal, "Horizon." When we talk about this particular essay, it is always important to note, and right at the beginning, that Orwell himself is claiming that he's not speaking about language in general. He's talking about political language, the language used by politicians. He specifically says, "I have not here been considering the literary use of language." If we're generous, we can give him that, but I think it's kind of a dodge because I feel like he does kind of broaden his scope. But also I feel like one of the things that has happened with this particular essay is that it is used as kind of a club by many people today in talking about language, and it is almost never used in the context of political language. People just talk out Orwell's views on English, and they don't say, "This is what Orwell had to say about politicians using the language. It's just used as a kind of general thing."

Ammon Shea: To me, one of the main problems is that Orwell seems to have very little idea of how language in general and English in particular actually works. It almost is farcically bad. I remember reading it as a kid and thinking, "Oh, this must be great. He's laying down these rules." We all love rules. We want rules about language. We want language to make sense. It feels very comforting to think that these are concrete steps that I can take to make my language use better, but they're not true. To say that the messenger is flawed is really being over-kind.

Emily Brewster: What does he say that's not true?

Ammon Shea: Well, he has a lot of things about, "Use short words. Never use a long word where a short word will do," which is this longstanding bugaboo with many people. Before Fowler wrote Modern English Usage , his famous book in 1926, he wrote a book with his brother, The King's English . They said you should always prefer the Saxon word to the Romance. E.B. White in The Elements of Style actually wrote, "Anglo-Saxon is a livelier tongue than Latin so use Anglo-Saxon words." Winston Churchill is quoted, whether he said it or not, as saying, "Short words are best, and the old words, when short are best of all." We've long had this feeling that you should go with the short Anglo-Saxon words rather than these fancy, flowery, long Latin words, which to me is just kind of a silly thing to say. I like long words, and when long words are appropriate, they're totally fine. So I think saying, "Never use a long word when a short one will do," is a little bit awkward considering that Orwell uses plenty of long words.

Emily Brewster: I'm looking at the essay. In the second paragraph he uses the word slovenliness . There's some significant letters in there.

Ammon Shea: What he's very good at doing, though, is breaking his own rule in the same sentence that he gives it. In this particular essay, he says, "There is a long list of fly-blown metaphors which could similarly to be got rid of." This is the section where he says, "Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print." Fly-blown is, of course, a metaphor. Unless the actual words here have the larva of flies growing out of them, they are not actually a fly-blown metaphor. They're metaphorical metaphors that he's talking about. The essay also has plenty of similes: "like cavalry horses answering the bugle," "a mass of Latin words," "falls upon the facts like soft snow." He talks about like a cuttlefish spreading out ink. He uses these similes and metaphors liberally. So it's kind of odd to me that he exhorts us to not use them. I think perhaps his most egregious mistake is when he says, "Never use the passive voice where you can use the active."

Emily Brewster: Except, Ammon, he doesn't say it like that. This stuck out to me also. He says-

Ammon Shea: It's the very first sentence. "Most people who bother with the matter at all would admit that the English language is in a bad way," and then he says, "it is generally assumed," passive voice here, "that we cannot by conscious action do anything about it." He's using the passive voice to tell you not to use the passive voice. So either he doesn't believe his own advice, or he doesn't understand it.

Emily Brewster: Then later in the same essay, he says, "In addition, the passive voice is wherever possible used in preference to the active." That itself is in the passive voice. "The passive voice is used," not "writers used the passive voice." Just to refresh people, if you wanted to say "the passive voice is wherever possible used in preference to the active," you would say "writers use the passive voice wherever possible, rather than preferring the active voice." So he is actively doing the things he says writers should not do in his own writing over and over again.

Ammon Shea: He does it in almost all cases. In fact, some people connected with language have found fault with this essay over the years. My favorite was, some while ago, some people went through and actually counted the number of instances in which he used the passive rather than the active voice and found that he was about twice as much as your average college essay at the time. He's using it in 20% of the cases as opposed to 10% of the time when people usually use it in this setting.

Emily Brewster: Wow.

Ammon Shea: He says, "Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent." He gives a list of phrases to avoid: deus ex machina , mutatis mutandis , status quo , ancien régime . If you go through any of his writing, he uses most of these in his other writings. He doesn't actually use them in this essay. So this is one that he's not okay with, but he does use them regularly. Overall, my favorite is his sixth rule, which is "Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous." I like this so much because it is the one rule that he actually adheres to in his own writing. He breaks all of his own rules so much that it raises the question of why he thought that this should happened in the first place.

Peter Sokolowski: To me, it's the first sentence of the second paragraph that caught my eye because he identifies himself as being a member of a kind of club and invites us to join that club. He says, "Now it is clear that the decline of a language must ultimately have political and economic causes." Now, first of all, I don't think that's clear at all. Second of all, he's announcing himself as declinist, that "kids today" basically is what he's saying and that "everything must be worse today because I remember when it was better." That is basically the same exact argument we hear all the time. It's the exact same argument that was put against Webster's Third . It's declinism. It's that everything is going to pot and everything is terrible. The weird thing about Orwell is that he makes the same mistake that everyone with a declinist argument makes, which is that he expects language to provide logic. That's just not how writing works. He insists that the decadent culture has produced a collapse of language and that that collapsed language then perpetuates this decline, which is an intellectual race to the bottom, which was exactly the argument against Webster's Third , blaming the dictionary for a perceived drop in quality of standardized test results or something. But the difference is he often seems to be blaming the words rather than the writing.

Ammon Shea: I think he does blame the words rather than writing. He also thinks that if we all just steel ourselves, we can change this. We can stem the flow of bad language by just being conscious of the words that we use. We're going to set a good example. There's a great point in this where he talks about how "the jeers of a few journalists" have done away with a number of phrases that he doesn't like, like "explore every avenue" and "leave no stone unturned." I think he's really overstating the effect that jeers of a few journalists can have on the language use of hundreds of millions of people. If you look at "explore every avenue" and "leave no stone unturned," in the decades following the 1940s, they actually increased dramatically. They're not going away. If they did go away, it wouldn't be because a few journalists like George Orwell jeered at them. It would be because people just stopped using these phrases.

Emily Brewster: You're listening to Word Matters. I'm Emily Brewster. We'll be right back with more on Orwell's "Politics and the English Language." Word Matters is produced by Merriam-Webster in collaboration with New England Public Media.

Peter Sokolowski: Word Matters listeners get 25% off all dictionaries and books at shop.merriam-webster.com by using the promo code "matters" at checkout. That's "matters," M-A-T-T-E-R-S at shop.merriam-webster.com.

Ammon Shea: I'm Ammon Shea. Do you have a question about the origin, history, or meaning of a word? Email us at [email protected].

Peter Sokolowski: I'm Peter Sokolowski. Join me every day for the Word of the Day, a brief look at the history and definition of one word, available at merriam-webster.com or wherever you get your podcasts. For more podcasts from New England Public Media, visit the NEPM podcast hub at nepm.org.

Emily Brewster: The conversation about George Orwell's "Politics and the English Language" continues. I do think, though, that the writing that he objects to, and he starts out by giving five examples I think, it is bad writing. He is pointing out that there are real problems. Here is his first example, which I found just mind-numbing. It was by Professor Harold Lasky. The example says, "I am not indeed sure whether it is not true to say that the Milton who once seemed not unlike a 17th century Shelley had not become out of an experience ever more bitter in each year more alien to the founder of that Jesuit sect which nothing could induce him to tolerate." I'm really good at reading opaque text, and this is really, really hard to follow.

Ammon Shea: I agree with you, absolutely. But I would point out that almost nothing in that would be fixed by any of the rules in Orwell's essay. He's using lots of short Saxon words in that piece. He's not using any metaphors or similes that I can see of. He's not using foreign expressions or phrases. I agree. That is a horrible piece of writing. I would not myself enjoy reading writing like that. Anyway, I'm with Orwell when he says that there is some bad writing out there, when he says there's bad political writing. Absolutely. But I feel that what he's kind of saying is let's make it better. Sure, I agree with that. That's where my agreement ends.

Emily Brewster: You agree with none of his advice?

Ammon Shea: I kind of agree with some of it a little bit. If it's possible to cut a word out, always cut it out? No, I don't agree with that. I think that's just a stylistic difference. I think if you look at writing in the 19th century, it's different than writing in the 20th century. It's just stylistically changed. I don't think that one is better for length than the other, or one is better for its brevity than the other.

Emily Brewster: I also have a problem with these kind of absolute statements: never use the passive voice, always use the fewest words possible. I think any kinds of absolutes are problematic. To always avoid any particular thing in writing is unhelpfully narrowing.

Ammon Shea: A great example of this kind of absolutism gone wrong is, we're all familiar with the "never end a sentence with a preposition." Of course, that's a meaningless thing. We end sentences with a preposition all the time. A lot of times the sentence construction demands ending a sentence with a preposition. Terminal prepositions are fine even though we've been hearing for hundreds of years that they're not. Every once in a while, somebody will come up with a variant on that. I used to occasionally see the rule in old uses books, "never end a sentence with a preposition or some other less meaningful word or insignificant word," I think was the way that they used to phrase it.

Ammon Shea: We're starting to make a little more sense if you don't want to end a sentence with a little blip, if you don't want to end your sentence with "of." Now, I don't think of prepositions as less meaningful or less significant personally, but that's just me. But I could see if somebody had the exhortation to end your sentence on an emphatic, meaningful, significant word, it's fine with me. I like that as a general rule of advice. But when you turn that into "Don't end it with a word that's less meaningful or significant," and that somehow becomes "Don't end it with a preposition or don't end it with this kind of thing," that's the kind of absolutism that just doesn't carry water.

Emily Brewster: This makes me think about the motivation for writing an essay such as this and the motivation for sharing an essay like this. This essay was written a long time ago now, in 1946. It is still something that people are talking about and are using in the aid of their own writing, and to try to get other people to be better writers. There is a desire among users of the English language to do that better, to become a better writer, and clearly Orwell thought that he had some important things as a skilled writer. This man was clearly a skilled writer of the English language. He published books. He knew how to use the English language. He was an expert in language use as much as anyone else who writes so many books or spend so much time using language. Any native speaker is actually also an expert. But he had a very specific kind of expertise, and he wanted to share this expertise with people. But he generalized his own expertise in a way that, as you point out, Ammon, was not even an accurate assessment of his own use. Why did he do that? What was he thinking?

Ammon Shea: I don't know why Orwell would write this. The lack of introspection here is stunning to me in that it comes up again and again and again. In the section on "Never use a long word where a short word one will do," he almost immediately says, "A speaker who uses that kind of phraseology has got..." This phraseology? That's a pretty damn long word there. I'm sure I could cut phraseology down by at least two or three syllables. Shorter than phraseology? I don't know why he was so lacking in introspection about his own writing.

Ammon Shea: I do think I know why people are still so adamant in sharing this because I think people just want tools. They want to reduce this glorious mess that is English to a series of concrete steps that you can take to make it definably better. Should I use a long word? Never. How about, should I use this simile that I know? Never. These are things that you can say to yourself. When should I use a simile that I'm used to seeing in print? You should never a simile. No, I'm going to never use a simile, and my writing will therefore be better. But I don't think that language responds well to this kind of absolutism. It gives us a sense of comfort. It must be better because I'm following these rules that were set down in the journal, Horizon, and that our results will be better. I don't think that's the way that it works.

Peter Sokolowski: He's completely ignorant on matters of the scientific study of language, on what we would call linguistics. He's not a linguist, but he's a good writer. That is the problem here, which is that so many people and especially declinists or language change deniers, people who say "kids today," they often want language to be like math. They want it to be logical, and they want to find a formula. I think what this all points to for me is that good prose style is much more art than science, and it requires, dare I say it, humanities exposure, the kind of general exposure to good writing and lots of it that you can only get if you read a lot. That's really the club to join. Join the readers who then can identify, "Oh, yes. That is a nicely turned phrase."

Peter Sokolowski: The fact is Orwell writes this in 1946, and he has nothing but contempt and scorn for all political discourse. Yet, he's within a couple of years of Churchill saying, "We shall meet them on the beaches. We shall meet them on the landing grounds." He's within a couple of years of FDR saying, "We have nothing to fear but fear itself." Some of the greatest political utterances in the history of the language were made just a couple of years before this essay was written. So he's kind of deliberately putting his thumb on the scale, which is what a lot of essayists do. He's got the right reflex but the wrong tools. He's not equipped to help others write. All he really is doing is listing his peeves.

Emily Brewster: But Peter, of those examples that you cite, Churchill and FDR, I think Orwell would have given the thumbs up to. He would've said, "Yes, these are good examples."

Ammon Shea: But those are following his rules. There is something to be said for that. Those are well written, and I think they're very effective particularly as political discourse. Again, if we're going to be kind to Orwell we can say that, yes, a lot of what he's saying will apply to the current political language that was being used.

Ammon Shea: Something that Peter said a few minutes ago, and I'm going to disagree with that, which is that you said, "People want language to be like math." I think in some ways they do, but actually I think people want language to be like religion more than they want it to be like math. There's a comfort that people get from certain religious structures that some other people try to get from certain linguistic structures, that there are things which are done by the righteous, and there are things that are done by the unrighteous in a way. And that a lack of adherence to this set of structure betokens a lack of moral fiber in a way because we make these value judgments of people based on their language use which have nothing to do with anything a lot of the time. It's not a one-to-one comparison between religion and language, but I am often reminded of religious fervor when I hear the way that certain people talk about how language use should be.

Peter Sokolowski: A big part of the conversations that we've all had with members of the public or strangers, people who correspond with a dictionary in one way or another, is some kind of membership of a club. "You care about language in the way that I do." There is absolutely a huge moral component that is imposed upon that. We always are judging others by their use of language. We are always judged by our use of language, by the way we spell, by the way we pronounce words. That's just a simple human fact. It's easier for us as professionals to separate that from culture.

Peter Sokolowski: So what you just said, Ammon, which is so true, which is that these things have nothing to do with drawing moral conclusions, whether you end a sentence with a preposition or whether you don't put an apostrophe in "you're." Yet, it becomes a shorthand for the kind of person that I want to know or the kind of person that I grew up with or the kind of person my parents raised me to be. That's very extra-linguistic, isn't it? That's why I think, Ammon, your analysis is brilliant. That takes you into something like religion, like culture, that goes way beyond what a language can do, but we extrapolate so much from it.

Emily Brewster: Language does indeed do that. It is one of the things that a language does, the different ways that language are used. It generates these in-groups and out-groups. But I think it is really important to reflect back on that and to recognize that good grammar does not mean ethical. You can have by-the-book grammar and never conjugate a verb incorrectly and be a horribly unethical person. That is wholly possible.

Peter Sokolowski: Exactly.

Ammon Shea: If we go back to Orwell, I don't want to be too harsh in my assessment of him, though I don't think he had any business writing about language, but this was just an essay that he wrote. I think the real problem here was that it's been then kept alive by other people who are trying to turn it into something that it's not and that it's not equipped to handle. I think insofar as these kinds of exhortatory writing advice pieces go, I'm willing to go as far as "you should write better; you should consider your language; you should write carefully." I think these are all fine things to say. I start to shut down when I see the linguistic absolutism: "never do this," and "never do that." There are very few cases that I can think of in which you should never do something. I'm not going to say you should never, of course, because that would contraindicate myself. But there are very few cases in which I would feel comfortable saying, "Never do this."

Peter Sokolowski: If you remove politics from this essay, I find it hard to distinguish it from Strunk & White, another famous book that also offers advice that is poorly constructed from a linguistics point of view.

Ammon Shea: I think there are a lot of problems with Strunk & White, but I feel that Strunk & White is actually more forgiving than this. I mean, Strunk & White, I don't think they say things like, "Never start a sentence with 'and' and 'but.'" They actually have some flexibility, not much. I think Strunk & White is a horrible, dated document that should be burned in a trash heap. It's not as bad as this.

Peter Sokolowski: I can't help but quote our friend Geoffrey Pullum, the great grammarian who refers to Strunk & White as "a toxic little compendium of nonsense."

Ammon Shea: Yes.

Emily Brewster: Yes, and "grammarian," as in a linguist.

Peter Sokolowski: A linguist and professor of grammar and author of maybe the definitive grammar of the English language today but also someone who has a great flare.

Emily Brewster: Yeah, that's a fantastic quote. The reason that this essay, of course, has been promulgated and is the reason we are talking about it today is because people are still talking about it, because people still want guidance on how to write better. I am wondering, Ammon, as a writer, how do you think people should learn to write better? Putting aside, for a minute, the writers who think that they have all this advice to offer to the rest of us, how should people who want to improve their writing do so?

Ammon Shea: Read more. Read writers you like is the way to go about it. For me, one of the main issues with a lot of the standard writing books is even writers that we enjoy, like many people enjoy Stephen King, I think he has some fine characteristics in his writing. When he starts giving writing advice, he had this great passage where he talked about all the times you shouldn't use adverbs. People went through and found dozens and dozens of adverbs in the page that he was talking about, "you shouldn't use adverbs in your writing." It quickly became apparent that he didn't really know what an adverb was in a lot of cases. That kind of writing advice, I think, doesn't work.

Ammon Shea: Now, I know a number of other writers who have read Stephen King and talked about the way that they've been influenced by his writing, the ways that he develops plot, maybe his character development, any number of things, which he does phenomenally well. I think that's a great way to learn writing. If for nothing else, one of my biggest peeves about this kind of language writing is that almost inevitably it is focusing on the negative. Why when we hear people say, "Oh, I care about language," why is that so often synonymous with saying, "I like to talk trash about the way that other people use language"? Why, when people say, "I care about language and let me share with you some of the things that I think are really beautiful about it. These are some fine examples of well-turned phrases," why is that so infrequently something that we come across?

Ammon Shea: I think if you care about language, if you love language, you should be embracing the kind of delectability of it, the fine use of language. Look at some of the nice ones. There's so much beautiful language around us that I think we're really doing ourselves a disservice, not to mention the people who have to listen to us, but doing them a much greater disservice if all we do is focus on the negative.

Emily Brewster: That's totally true. But it's easier to point out the ugliness than it is to quote the sublime. There is gorgeous writing out there that can just be staggering. I think the other thing is that if you want to improve your writing, it's really nice to think that there are some distinct steps that you can take that will then result in you being an improved writer. That's really comforting and much simpler than read, read, read, read, read, read good writers, read over and over and over again, and identify things you really like, and then read something aloud that you have written and see how it feels.

Emily Brewster: Writing well is not about following distinct steps. It's about getting a feel for it. It is an art form. But the really tricky thing about it is that we all use language. Painters have paint as their territory. That's their medium. I don't even have to dabble in it. I mean I paint my bathroom, whatever. I don't have mastery, and I don't think that I have mastery of paint at all, and I don't need to. But as a speaker of English and as somebody who has to write an occasional email or whatever, even if I weren't a lexicographer, all of us, as native speakers, we use this tool, and then some people use it professionally. It's a very tricky territory. Some people use it artistically, and some people use it solely for jargon, and some people use it for political purposes. We need the language to do so much, and it does do all these different things.

Emily Brewster: To get really good at writing creatively or writing in a way that moves people or that convinces people, it feels like it should be simple because you know the tools, you know the words, you know the prepositions, you know the basic sentence structure. But to actually do it in a way that is compelling takes a lot of practice.

Emily Brewster: Let us know what you think about Word Matters. Review us wherever you get your podcasts or email us at [email protected]. You can also visit us at nepm.org. For the Word of the Day and all your general and dictionary needs, visit merriam-webster.com. Our theme music is by Tobias Voigt, artwork by Annie Jacobson. Word Matters is produced by John Voci. For Ammon Shea and Peter Sokolowski, I'm Emily Brewster. Word Matters is produced by Merriam-Webster in collaboration with New England Public Media.

Word of the Day

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Games & Quizzes

Politics and the English Language

George orwell, everything you need for every book you read..

George Orwell ’s central argument is that the normalization of bad writing leads to political oppression. Orwell starts with the premise that the distortion of “language” reflects a “corruption” of “civilization.” But Orwell objects to the conclusion he believes readers usually draw from this initial premise. Specifically, Orwell claims that most readers—even those who think language and politics are in a bad state—presume that language is merely a mirror of society. That is, language only reflects the state of the world. Orwell claims language doesn’t just reflect the condition society. Language, he argues, also shapes society. He contends that language is both prescriptive and descriptive of civilization’s decline.

Orwell then takes a step back to what explain constitutes bad writing. He begins by listing a series of passages. Reading each passage, it’s difficult (if not impossible) to make out the writer’s point. Orwell uses these passages to identify the elements of bad writing, such as “inflated prose” or a “mixture of vagueness and sheer incompetence.” In describing the features of “inflated prose,” Orwell posits that laziness is the primary driver of “inflated style.” That is, instead choosing words and phrases carefully, lazy writers use inflated style to grab whatever smart-sounding words and phrases they have on hand. In the process, bad writers lose their grip on reality, allowing junked-up prose to create a “gap between one's real and one's declared aims.” These writers, he explains, exchange truth for convincing as they pull together words without “really thinking.”

According to Orwell, inflated style circulates through society like a disease, rotting the brains of writers and readers. Once the normalized, Orwell warns, aspiring dictators can more easily engage in linguistic trickery. Manipulative governments can “make lies sound truthful and murder respectable” by using the same “inflated style” of lazy writers. In other words, dictatorships merely capitalize on the linguistic vagueness normalized by lazy writers.

Thus, as means of resisting oppression, Orwell encourages readers to adopt more careful reading and writing practices. To help a writer “change his own habits” as means to resists government manipulation, Orwell outlines eight guidelines for writers geared towards more honesty and concision. He explicitly warns against relying on “readymade phrases” which he describes as like “a packet of aspirins always at one's elbow.” Instead, Orwell encourages readers to exercise more imagination and create more vivid metaphors. Likewise, Orwell recommends concision: using as few syllables and words as possible.

The Language of George Orwell pp 19–34 Cite as

Orwell’s Views on Language

- Roger Fowler

78 Accesses

Part of the book series: The Language of Literature ((LOL))

In 1946, toward the end of his career but with one great novel still to be written, Orwell published an essay called ‘Why I Write’, reflecting on his aims and motives. This paper is helpfully reprinted right at the beginning of the otherwise chronologically arranged four volumes of Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters ( CEJL , I, pp. 23–30), and it gives valuable insights into Orwell’s artistic and linguistic goals. At its climax we find the often-quoted comment that ‘Good prose is like a window pane.’ Clarity is the prime requirement in prose writing. ‘Of later years,’ he writes, ‘I have tried to write less picturesquely and more exactly.’ And again in this essay: ‘So long as I remain alive and well I shall continue to feel strongly about prose style, to love the surface of the earth, and to take pleasure in solid objects and scraps of useless information.’ Prose is to be clear, exact, precise. Orwell’s essays contain many other references to precision and clarity, and in the later years, repeated analyses of what he felt to be abuses of language which worked against this quality of transparency.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

See J. Milroy and L. Milroy, Authority in Language (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1985), Ch. 2.

Book Google Scholar

A readable modern textbook on sociolinguistics is M. Montgomery, An Introduction to Language and Society (London: Routledge, 1986).

M. A. K. Halliday, Language as Social Semiotic (London: Arnold, 1978)

Google Scholar

On dialect in fiction, see N. Page, Speech in the English Novel (London: Longman, 1973)

G. N. Leech and M. H. Short, Style in Fiction (London: Longman, 1981).

H. Adams (ed.) Critical Theory since Plato (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1971) p. 434.

For extensive samples of transcribed conversational data, see J. Svartvik and R. Quirk (eds) A Corpus of English Conversation (Lund: C. W. K. Gleerup, 1980).

Orwell saw clearly the need to describe the speech/writing distinction. In ‘Propaganda and Demotic Speech’ he advocates collecting sample recordings of speech in order to ‘formulate the rules of spoken English and find out how it differs from the written language’ ( CEJL , III, 166). For modern work on the distinction, see M. A. K. Halliday, Spoken and Written Language (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989)

M. A. K. Halliday, ‘Spoken and Written Modes of Meaning’, in R. Horowitz and S. Jay Samuels (eds) Comprehending Oral and Written Language (San Diego: Academic Press, 1987) pp. 55–82

D. Tannen (ed.) Spoken and Written Language: Exploring Orality and Literacy (Norwood New Jersey: Ablex, 1982).

M. Maclure, T. Phillips and A. Wilkinson (eds) Oracy Matters (Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1988).

F. de Saussure, trans. Wade Baskin, Course in General Linguistics [1916], reprinted with an introduction by J. Culler (Glasgow: Fontana, 1974) pp. 71ff.

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Copyright information

© 1995 Roger Fowler

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Fowler, R. (1995). Orwell’s Views on Language. In: The Language of George Orwell. The Language of Literature. Palgrave, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-24210-8_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-24210-8_3

Publisher Name : Palgrave, London

Print ISBN : 978-0-333-54908-7

Online ISBN : 978-1-349-24210-8

eBook Packages : Palgrave Literature & Performing Arts Collection Literature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

The Best George Orwell Essays Everyone Should Read

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

George Orwell (1903-50) is known around the world for his satirical novella Animal Farm and his dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four , but he was arguably at his best in the essay form. Below, we’ve selected and introduced ten of Orwell’s best essays for the interested newcomer to his non-fiction, but there are many more we could have added. What do you think is George Orwell’s greatest essay?

1. ‘ Why I Write ’.

This 1946 essay is notable for at least two reasons: one, it gives us a neat little autobiography detailing Orwell’s development as a writer; and two, it includes four ‘motives for writing’ which break down as egoism (wanting to seem clever), aesthetic enthusiasm (taking delight in the sounds of words etc.), the historical impulse (wanting to record things for posterity), and the political purpose (wanting to ‘push the world in a certain direction’).

2. ‘ Politics and the English Language ’.

The English language is ‘in a bad way’, Orwell argues in this famous essay from 1946. As its title suggests, Orwell identifies a link between the (degraded) English language of his time and the degraded political situation: Orwell sees modern political discourse as being less a matter of words chosen for their clear meanings than a series of stock phrases slung together.

Orwell concludes with six rules or guidelines for political writers and essayists, which include: never use a long word when a short one will do, or a specialist or foreign term when a simpler English one should suffice.

We have analysed this classic essay here .

3. ‘ Shooting an Elephant ’.

This is an early Orwell essay, from 1936. In it, he recalls his (possibly fictionalised) experiences as a police officer in Burma, when he had to shoot an elephant that had got out of hand. Orwell extrapolates from this one event, seeing it as a microcosm of imperialism, wherein the coloniser loses his humanity and freedom through oppressing others.

We have analysed this essay here .

4. ‘ Decline of the English Murder ’.

In this 1946 essay, Orwell writes about the British fascination with murder, focusing in particular on the period of 1850-1925, which Orwell identifies as the golden age or ‘great period in murder’ in the media and literature. But what has happened to murder in the British newspapers?

Orwell claims that the Second World War has desensitised people to brutal acts of killing, but also that there is less style and art in modern murders. Oscar Wilde would no doubt agree with Orwell’s point of view!

5. ‘ Confessions of a Book Reviewer ’.

This 1946 essay makes book-reviewing as a profession or trade – something that seems so appealing and aspirational to many book-lovers – look like a life of drudgery. Why, Orwell asks, does virtually every book that’s published have to be reviewed? It would be best, he argues, to be more discriminating and devote more column inches to the most deserving of books.

6. ‘ A Hanging ’.

This is another Burmese recollection from Orwell, and a very early work, dating from 1931. Orwell describes a condemned criminal being executed by hanging, using this event as a way in to thinking about capital punishment and how, as Orwell put it elsewhere, a premeditated execution can seem more inhumane than a thousand murders.

We discuss this Orwell essay in more detail here .

7. ‘ The Lion and the Unicorn ’.

Subtitled ‘Socialism and the English Genius’, this is another essay Orwell wrote about Britain in the wake of the outbreak of the Second World War. Published in 1941, this essay takes its title from the heraldic symbols for England (the lion) and Scotland (the unicorn). Orwell argues that some sort of socialist revolution is needed to wrest Britain out of its outmoded ways and an overhaul of the British class system will help Britain to defeat the Nazis.

The long essay contains a section, ‘England Your England’, which is often reprinted as a standalone essay, written as the German bomber planes were whizzing overhead during the Blitz of 1941. This part of the essay is a critique of blind English patriotism during wartime and an attempt to pin down ‘English’ values at a time when England itself was under threat from Nazi invasion.

8. ‘ My Country Right or Left ’.

This 1940 essay shows what a complex and nuanced thinker Orwell was when it came to political labels such as ‘left-wing’ and ‘right-wing’. Although Orwell was on the left, he also held patriotic (although not exactly fervently nationalistic) attitudes towards England which many of his comrades on the left found baffling.

As with ‘England Your England’ above, the wartime context is central to Orwell’s argument, and lends his discussion of the relationship between left-wing politics and patriotic values an urgency and immediacy.

9. ‘ Bookshop Memories ’.

As well as writing on politics and being a writer, Orwell also wrote perceptively about readers and book-buyers – as in this 1936 essay, published the same year as his novel Keep the Aspidistra Flying , which combined both bookshops and writers (the novel focuses on Gordon Comstock, an aspiring poet).

In ‘Bookshop Memories’, reflecting on his own time working as an assistant in a bookshop, Orwell divides those who haunt bookshops into various types: the snobs after a first edition, the Oriental students, and so on.

10. ‘ A Nice Cup of Tea ’.

Orwell didn’t just write about literature and politics. He also wrote about things like the perfect pub, and how to make the best cup of tea, for the London Evening Standard in the late 1940s. Here, in this essay from 1946, Orwell offers eleven ‘golden rules’ for making a tasty cuppa, arguing that people disagree vehemently how to make a perfect cup of tea because it is one of the ‘mainstays of civilisation’. Hear, hear.

3 thoughts on “The Best George Orwell Essays Everyone Should Read”

Thanks, Orwell was a master at combining wisdom and readability. I also like his essay on Edward Lear, although some of his observations are very much of their time: https://edwardleartrail.wordpress.com/2018/10/16/george-orwell-on-edward-lear/

The Everyman edition of Orwell’s essays (1200 pages !) is my desert island book. I like Shooting the Elephant altho Julian Barnes seems to believe this is fictitious. Is this still a live debate ?

- Pingback: The Best George Orwell Essays Everyone Should Read

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from interesting literature.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

You Must Read This

Orwell on writing: 'clarity is the remedy'.

Lawrence Wright

Lawrence Wright is an author and screenwriter, and a staff writer for The New Yorker magazine. His most recent book is The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11 .

Wright Appearances on NPR

Book explores latest jihadi thinking, building a terror network: 'the road to 9/11', al qaeda using internet to spread terrorist message.

Call them buttonhole books, the ones you urge passionately on friends, colleagues and passersby. All readers have them -- and so do writers. All Things Considered talks with writers about their favorite buttonhole books. And the series continues all summer long on NPR.org.

Most people these days think of George Orwell as a writer for high-school students, since his reputation rests mostly on two late novels -- Animal Farm and 1984 -- that are seldom read outside the classroom. But through most of his career, Orwell was known for his journalism and his rigorous, unsparing essays, which documented a time that seems in some ways so much like our own.

At the end of World War II, one form of totalitarianism -- fascism -- had been defeated; but another -- communism -- was spreading across Europe and Asia. Orwell's own country, England, was suffering through a political crisis, as it struggled to find the will to resist the new threat. It was then, in 1946, that Orwell wrote his great essay, "Politics and the English Language," which I first read as a freshman at Tulane University and immediately adopted as my guide. Over the years, I've gone back to it repeatedly, like a student visiting an old professor who always has something new to reveal.

Orwell's proposition is that modern English, especially written English, is so corrupted by bad habits that it has become impossible to think clearly. The main enemy, he believed, was insincerity, which hides behind the long words and empty phrases that stand between what is said and what is really meant.

A scrupulous writer, Orwell notes, will ask himself: What am I trying to say? What words will express it? What fresh image will make it clearer? Could I put it more shortly? Have I said anything that is avoidably ugly? The alternative is simply "throwing your mind open and letting the ready-made phrases come crowding in. They will construct your sentences for you -- even think your thoughts for you -- concealing your meaning even from yourself. It is at this point that the special connection between politics and the debasement of language becomes clear."

Orwell was a supremely political writer himself, having waged a lifelong campaign against totalitarianism; and indeed, for him, all issues were political issues, "and politics itself is a mass of lies, evasions, folly, hatred and schizophrenia."

Orwell's candor, his steadiness, his stern and scrupulous impartiality are qualities that make this essay still sound contemporary and urgent, at a time when the reputation of so many of his contemporaries has faded. I think the secret of Orwell's timelessness is that he doesn't seek to please or entertain; instead, he captures the reader with a style as intimate and frank as a handshake. It is that quality of common humanity that makes his essay so luminous and his voice so familiar.

Orwell optimistically sets forward six simple rules to improve the state of the English language: guidelines that anyone, not just professional writers, can follow.

But I'm not going to tell you what they are. You'll have to re-read the essay yourself. I'm only going to speak about Rule No. 1, which is never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech that you are used to seeing in print.

For me, that's the hardest rule and no doubt the reason that it's No. 1. Cliches, like cockroaches in the cupboard, quickly infest a careless mind. I constantly struggle with the prefabricated phrases that substitute for simple, clear prose. We are still plagued by toe the line, stand shoulder to shoulder with, no axe to grind -- meaningless images that every reader subconsciously acknowledges represent the opposite of real thought -- but it is dismaying to read that two exhausted metaphors, leave no stone unturned and explore every avenue, had been jeered out of common usage in Orwell's day by journalists who took the trouble to dismiss them.

"Political language," Orwell reminds us, "is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind. One cannot change this all in a moment, but one can at least change one's own habits."

Orwell wasn't interested in decorative writing, but his straightforward, declarative style has a snap in it that few other writers have ever approached. In a time when politics and the English language once again seem to be at odds, perhaps his essay can make us remember that clarity is the remedy.

NPR's Ellen Silva produced and edited this series.

Buy Featured Book

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Politics And The English Language

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

15,900 Views

26 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

For users with print-disabilities

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by bomonomo on March 23, 2015

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

The PhD Experience

- Call for Contributions

George Orwell’s Six Rules for Writing: A Reassessment

https://unsplash.com/photos/FHnnjk1Yj7Y

By Daniel Adamson |

In April 1946, George Orwell published a short essay entitled “Politics and the English Language”. Orwell’s clear intention was to remedy the pervasive ‘ugly and inaccurate’ written English in contemporary literature.

Modern English, especially written English, is full of bad habits which spread by imitation and which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble.

Ultimately, Orwell’s efforts were underpinned by political concerns, in an era where propaganda had become the arme de choix of a range of oppressive political movements.

“Politics and the English Language” has become best known for its suggested six rules of writing, which might be employed in order to avoid poor writing. Since their publication, these guidelines have become much loved from amateur literary blogs to self-help websites.

Nonetheless, Orwell’s rules deserve reassessment. Much has changed since 1946: the map of Europe has been redrawn, 140-character tweets have become a primary mode of communication, and a global health crisis has brought the world to a standstill. Do Orwell’s rules, therefore, still hold firm? And what lessons might a PhD student garner from reading them?

Rules for writing or rules for life?

Let us take Orwell’s six rules in turn, and consider the resonance each recommendation could carry for a PhD researcher in the twenty-first century

1. Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print

Originality is certainly a watchword of many PhD projects. The ability to break new ground within a dissertation is admirable. However, the quest to express oneself in an unprecedented way should not obscure the clear presentation of research findings. In some cases, certain metaphors or similes have become integrated into the English language precisely because they capture a sentiment in a particularly effective manner. In this case, their replication in a passage of PhD prose could be justified. A preoccupation with originality of prose has the converse potential to lead to the creation of phrases which are simply inappropriate. If writers cannot bring themselves to use an established figure of speech, the best advice might be to avoid elaborate language altogether: simply state an idea in plain terms.

2. Never use a long word where a short one will do.

Concision is essential in PhD research. A reader must be able to take away a clear picture of research findings. Equally, in the time-pressed academic world, accessible prose is a valued characteristic. The academic community is also global. English may not be the first language of any given reader. As such, the avoidance of archaic or obscure vocabulary is a sensible measure.

3. If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

Orwell’s prioritisation of economical prose will speak to many PhD students. A limit of 100,000 words is, at first, daunting for many researchers when starting to write a dissertation. Often, however, the eventual challenge will be deciding which words to omit from a final draft. As such, the implications of Orwell’s advice are sound. If a long phrase can be substituted for a shorter one, it creates more room for the inclusion of useful insights.

4. Never use the passive where you can use the active.

Of all Orwell’s rules, this is perhaps the recommendation which is most dependent on personal preference. As long as the use of the passive voice does not obscure the clarity of prose (see rules 2 and 3), it seems somewhat drastic to forbid its use altogether. Rule number 4 might better be adapted to provide advice for life, rather than writing: ‘never be passive where you can be active’. The COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated how opportunities can be snatched away in a tragically short period of time. As such, PhD students must take initiative in maximising their chances when they become available. Seek out what can be done given contextual circumstances, rather than waiting for opportunities to present themselves unprompted.

5. Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

The fifth rule in Orwell’s list is perhaps only partially applicable to PhD research publications. Particularly in scientific subjects, the use of technical vocabulary is unavoidable. Even in the arts and humanities, foreign words frequently can capture a notion that eludes the boundaries of the English language: glasnost , zeitgeist , détente and so forth. Once again, the use of specified words should not be pretentious, nor detract from the lucidity of research. One potential strategy is to include approximate English translations or explanations for more esoteric language.

6. Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

In all areas of academic life, the avoidance of barbarity should be encouraged. There is often little to gain from cruelty towards the work of others. Commonly, such conduct is merely a way of exerting power over those less senior, and is almost never constructive. Criticism is a necessary element of the PhD experience. However, it is most effective when it is used to improve research, rather than to belittle work. ‘Be kind’ has emerged as a maxim of the Coronavirus-era, and it is a motto which all academics should observe.

Respect, not rigidity

Overall, few would argue that Orwell’s six rules of writing do not provide a solid base around which to centre prose. Orwell did not intend his guidelines to be used by postgraduates, but PhD students can find value in several different aspects of the guidelines, particularly in relation to the economy and clarity of writing.

Orwell’s recommendations command respect, even in the twenty-first century. However, it is also rather tyrannical to suggest that a rigid set of rules should dictate universal writing habits. In this blog alone, Orwell’s rules have probably been broken in various ways.

The deployment of the English language is a highly-personalised action, and one which lends human beings a sense of individual character. PhD projects can benefit from a stamp of personality. If it takes breaking some of Orwell’s rules to achieve this in a dissertation, PhD students should proceed with confidence. Moderation, as always, is key.

Daniel Adamson is a PhD student in the History Department at Durham University. He tweets at @DanielEAdamson.

Image 1 (open copyright): https://www.vautiercommunications.com/blog/6-rules-for-writing-george-orwell

Share this post:

September 10, 2020

academia , Phd , writing

academia , politics , research , thesis , writing , writing up

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Search this blog

Recent posts.

- Seeking Counselling During the PhD

- Teaching Tutorials: How To Mark Efficiently

- Prioritizing Self-care

- The Dream of Better Nights. Or: Troubled Sleep in Modern Times.

- Teaching Tutorials – How To Make Discussion Flow

Recent Comments

- sacbu on Summer Quiz: What kind of annoying PhD candidate are you?

- Susan Hayward on 18 Online Resources and Apps for PhD Students with Dyslexia

- Javier on My PhD and My ADHD

- timgalsworthy on What to expect when you’re expected to be an expert

- National Rodeo on 18 Online Resources and Apps for PhD Students with Dyslexia

- Comment policy

- Content on Pubs & Publications is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.5 Scotland