Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

Free will is the idea that humans have the ability to make their own choices and determine their own fates. Is a person’s will free, or are people's lives in fact shaped by powers outside of their control? The question of free will has long challenged philosophers and religious thinkers, and scientists have examined the problem from psychological and neuroscientific perspectives as well.

- Does Free Will Exist?

- Why Beliefs About Free Will Matter

Scientists have investigated the concept of human agency at the level of neural circuitry, and some findings have been taken as evidence that conscious decisions are not truly “free.” Free will skeptics argue that the subjective sense of free will is an illusion. Yet many scholars, as well as ordinary people, still profess a belief in free will, even if they acknowledge that choices are partly shaped by forces outside of one's control.

Behavioral science has made plain that individuals’ behavioral tendencies are influenced by genetics , as well as by factors in the environment that may be outside of a person’s control. This suggests that there are, at least, some constraints on the range of decisions and behaviors a person will be inclined to make (or even to consider) in any given situation. Challengers of the idea that people act the way they do due to conscious, unconstrained choices also point to evidence that unconscious brain activity can partly predict a choice before a conscious decision is made. And some have sought to logically refute the argument that choices necessarily demonstrate free will.

While there are many reasons to believe that a person’s will is not completely free of influence, there is not a scientific consensus against free will. Some use the term “free will” in a looser sense to reflect that conscious decisions play a role in the outcomes of a person’s life—even if those are shaped by innate dispositions or randomness. (Critics of the concept of free will might simply call this kind of decision-making “will,” or volition.) Even when unconscious processes help determine a person’s conscious behavior, some argue, such processes can still be thought of as part of an individual’s will.

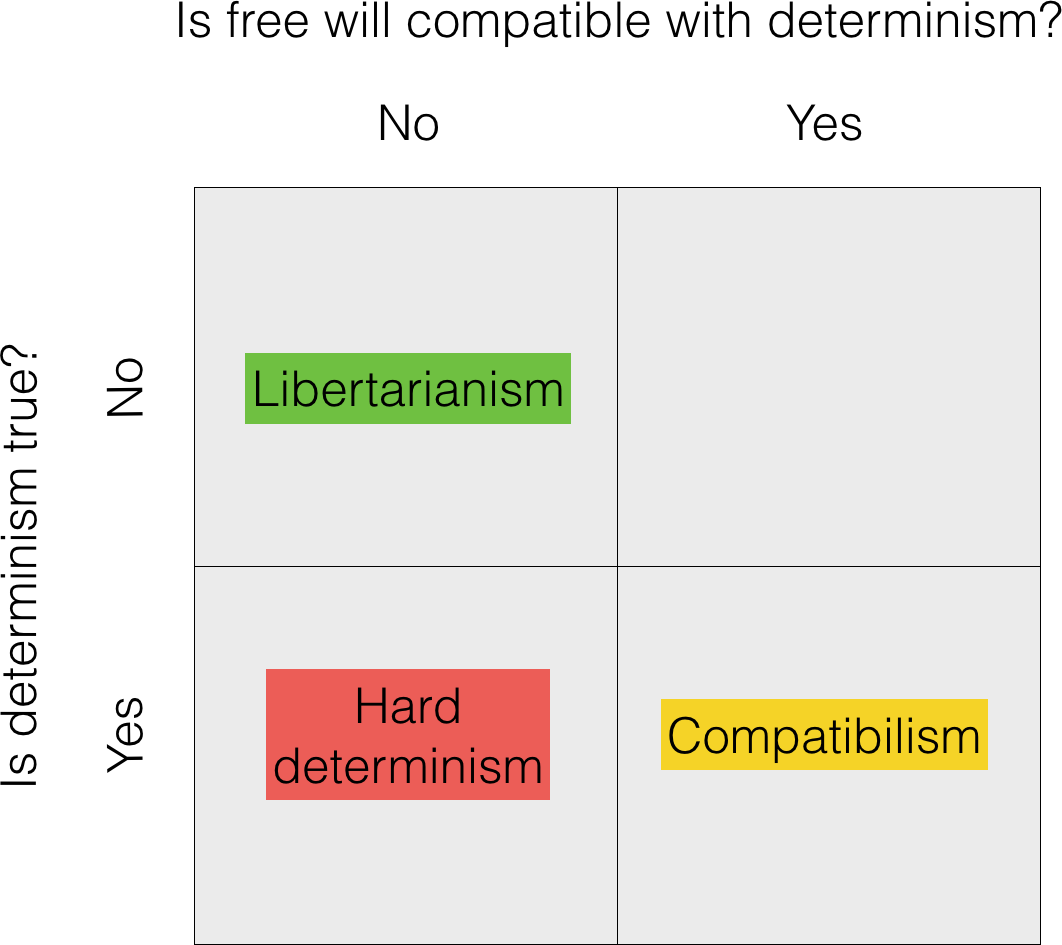

Determinism is the idea that every event, including every human action, is the result of previous events and the laws of nature. A belief in determinism that includes a rejection of free will has been called “hard determinism.”

From a deterministic perspective, there is only one possible way that future events can unfold based on what has already occurred and the rules that govern the universe—though that doesn’t mean such events can necessarily be predicted by humans. Someone who believes in free will because they do not take determinism for granted is called, in philosophy , a “libertarian.”

Yes. This is called “compatibilism” or “soft determinism.” A compatibilist believes that even though events are predetermined, there is still some version of free will at work in decision-making . An incompatibilist argues that only determinism or free will can be true.

Whether free will exists or not, belief in free will is very real. Does it matter if a person believes that her choices are completely her own, and that other people’s choices are freely made, too? Psychologists have explored the connections between free will beliefs—often gauged by agreement with statements like “I am in charge of my actions even when my life’s circumstances are difficult” and, simply, “I have free will”—and people’s attitudes about decision-making, blame, and other variables of consequence.

The more people agree with claims of free will , some research suggests, the more they tend to favor internal rather than external explanations for someone else’s behavior. This may include, for example, learning of someone’s immoral deed and agreeing more strongly that it was a result of the person’s character and less that factors like social norms are to blame. (A study of whether reducing free-will beliefs influenced sentencing decisions by actual judges, however, did not show any effect. )

One idea proposed in philosophy is that systems of morality would collapse without a common belief that each person is responsible for his actions—and thus deserves reward or punishment for them. In this view, there is value in maintaining belief in free will, even if free will is in fact an illusion. Others argue that morality can exist in the absence of free-will belief, or that belief in free will actually promotes harmful outcomes such as intolerance and revenge-seeking. Some psychology research has been cited as suggesting that disbelief in free will increases dishonest behavior, but subsequent experiments have called this finding into question.

Mental illness can be thought of, in a sense, as involving additional constraints on the freedom of a person’s will (in the form of rigid thought patterns or compulsions, for instance), beyond the usual factors that shape thinking and behavior. Belief in free will, it has been argued, may contribute to the stigma attached to mental illness by obscuring the role of underlying biological and environmental causes.

There is limited evidence that people who believe more strongly in free will may tend to perceive at least some kinds of choices—such as buying electronics or deciding what to watch on TV—as easier to make, and that they may enjoy making choices more.

Two concepts from psychology that bear similarity to belief in free will are “ locus of control ” and “ self-efficacy .” Locus of control refers to a person’s belief about how much power he has over his life—how important factors like intentions and hard work seem to be compared to external forces such as good luck or the actions of others. Self-efficacy is a person’s sense of her ability to perform at a certain level so as to influence events that affect them. While all of these concepts relate to the factors that steer a person’s life, they are distinct—one can doubt that humans have free will, for example, and still be confident in her ability to win a competition .

As initiatives are discussed surrounding involuntary psychiatric care, an important element is ignored. The quality of treatment in the hospital is often poor.

Individuals with serious and persistent mental illnesses are held to a different standard in physician-assisted dying.

Kierkegaard's philosophy offers insights into living authentically and finding fulfillment amidst the distractions and pressures of the modern world.

If the days of bettering oneself through a liberal arts education have transformed into simply “making more money,” then let’s just teach kids to write ransom notes.

As brains evolved in complexity, they acquired top-down control systems, such that bottom-up inputs cannot completely predict behavioral outputs. Does this mean we have free-will?

New theoretical work helps us understand which aspects of emotional processing can and cannot be controlled.

To help ensure you actually reach your New Year's resolutions (or any goal), here is an essential technique you need in your repertoire.

The "mysteries" of concern to Freud and Jung were restricted to semantic processes, which today are not a mystery. But consciousness remains a true mystery.

Is it possible for a tiny decision to make a big impact? Surprisingly, infinitesimal self-help practices can be effective, when bigger commitments will fail.

Dopamine is the molecule that makes us feel good about expending effort. Motivation neurobiology reveals ways to enhance effort without extra calories, drugs, or risk.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Philosophy, One Thousand Words at a Time

Free Will and Free Choice

Author: Jonah Nagashima Category: Metaphysics Word Count: 997

An auctioneer opens the bidding on a painting. A moment later, your hand raises.

Now, consider three backstories:

- You had no intention to bid, but a spasm caused your hand to raise.

- You don’t value the painting, but someone put a gun to your head, telling you to bid “or else.” Wanting to live, you raised your hand.

- You wanted the painting, and so you raised your hand to bid.

Were any of these bids made on your own free will? Were they free choices? [1]

This depends on what free will is and whether or not we ever have it. [2] This essay surveys the major positions on these issues.

1. Determinism

Suppose that the fundamental physical laws determine every event such that, at the moment of the big bang, it was already settled that you’d read this essay because the laws and initial conditions of the world necessitate that you’d do so; given their presence, it was guaranteed that you would.

This describes physical determinism , which is a kind of determinism , the view that every event is necessitated by prior events: current and future events must happen as they happen. [3]

Alternatively, if indeterminism is true, then not everything is determined: some things that happen aren’t necessitated by prior events; there’s some chance in the picture. [4]

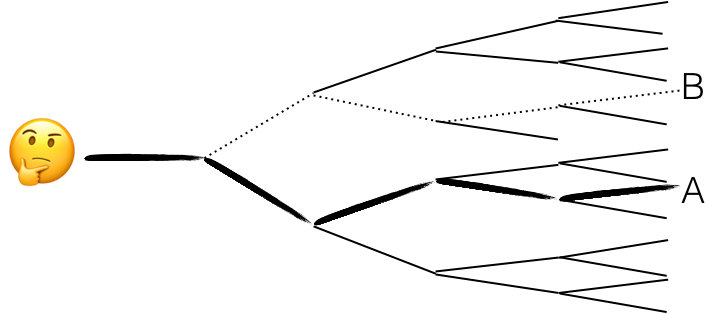

Either free choice is compatible with determinism (“ compatibilist ” theories of freedom) or it isn’t (“ incompatibilist ” theories). [5] Let’s explore both options, starting with incompatibilism.

2.1. Incompatibilism: Libertarianism

Libertarians believe that free will is incompatible with determinism and argue that we have free will. Let’s motivate both, starting with incompatibilism.

Two incompatibilist theories of free will are these:

(A) a free choice is one where the person is able to choose other than what she, in fact, chooses : she didn’t have to do what she actually did; [6]

(B) a free choice is one where the person is the ultimate source of her choice. [7]

Story (3) provides some support for these theories: we might say that you freely bid on the painting because you could have refrained from bidding or because you were the sole source of the choice to bid.

These theories are incompatibilist theories: having free will in these senses is incompatible with determinism. If determinism is true, events that happened long before we were born are the ultimate source of our choices, not us, so we lack free will according to theory (B). And, if determinism is true, the past necessitates our choices, making it impossible that we do anything other than what we actually do, so we lack free will according to theory (A). [8]

Libertarians [9] accept theories of free will like these. They argue, however, that we sometimes do have free will, often in the senses of (A) or (B), and so that shows that determinism is false: sometimes we can do other than what we actually do and we are the ultimate source of our choices.

A worry. Libertarians say that free choice requires indeterminism, but indeterminism doesn’t seem hospitable for free choice. Consider backstory (3) again: if this action is not determined, then you could’ve had the exact same desires and reasons for bidding and refrained from bidding. Indeterminism then seems to introduce randomness , which looks inhospitable to free will, as the muscle spasm example (1) suggests: the spasm wasn’t a freely-made bid. Explaining why undetermined actions aren’t ultimately random is a challenge for libertarians. [10]

2.2. Incompatibilism: Hard Determinism

Hard determinists agree with libertarians that free will is incompatible with determinism, but deny that we have free will. They agree that free will requires something like (A) or (B) but argue that, since our world is deterministic, nobody has free will: nobody can do other than what they actually do and nobody is the ultimate source of their actions. [11]

A concern. Many think that we are morally responsible for our actions only when we act from our free will. So hard determinists have the challenge of explaining what justifies practices like punishment and reward, and praise and blame, if we lack free will. [12]

3. Compatibilism

Consider some compatibilist theories of free choice:

(C) a person chooses freely when she acts in accordance with her own desires and values ; [13]

(D) a person chooses freely just when the source of her choice is responsive to reasons . [14]

Backstory (3) was a free action on either of these theories because you did what you wanted to do or what you had reason to do. Backstory (2) we could judge as not free, since you bid because of coercion and someone else’s desire for the painting, not your own. We could say, however, that you freely chose to avoid being shot, since you didn’t want that!

These judgments are compatible with your action’s being determined. If determinism is true, then your will, values, and desires are determined. But you can do what you want to do, act on your own reasons, and yet be determined to act that way. Proposals (C) and (D) then are compatibilist theories of free will: actions can be free and determined. This would be welcome news should we discover that our world is deterministic: our freedom wouldn’t hang on the falsity of determinism. [15]

A problem. Suppose that a covert manipulator subtly manipulates Eleanor into having certain desires, which determine Eleanor to choose in certain ways, based on reasons she’s responsive to, all of which are conducive to the manipulator’s ends. [16] Would Eleanor be acting freely? It seems doubtful, since she isn’t the source of her actions – the manipulator is. Furthermore, because of the efficacy of the manipulation, Eleanor is unable to do other than what she in fact does. Theories (C) and (D) however, imply she chooses freely. Not great. Compatibilists thereby either need to amend their theories or explain why this kind of manipulation doesn’t undermine freedom. [17]

4. Conclusion

Each theory above attempts to answer the question of whether we have free will. Which overall position we should accept depends both upon what free will is and what we, and the world, are like. [18]

[1] Some argue that a free choice is one made of one’s own free will , taking the will to be most fundamental. See Robert Kane’s The Significance of Free Will for arguments for this position. We’ll address both here, given the close relations between the will and choices.

[2] What something is , or how it is accurately defined, and whether something exists are distinct questions. E.g., we can ask what witches are , what the definition of a witch is, but deny they exist. Atheists argue, “The concept of God is this . . ., but I think that God does not exist.” Eliminativists about race say, “Races are this . . , but races do not exist,” and so on. So, to define something, or explain what it is , does not commit one to claiming that the thing in question exists. So, the questions of what free will is and whether actually we have free will are distinct.

[3] Physical determinism is one kind of determinism. Another kind of determinism is theological determinism , which comes in varieties. Suppose God exists and infallibly knows the future from the creation of the world. If so, then it seems that God’s knowledge determines that future. Or suppose instead that God willed before the creation of the world that you’d read this essay, and that everything God wills must come to pass: could you avoid reading this essay? For discussion, see Attributes of God by Bailie Peterson. A related, but distinct, view is fatalism , the view that, very roughly, present truths about the future determine that future or make that future inevitable. You might think that some of these types of determinisms, but not others, rule out free will.

[4] Indeterminism is consistent with some events or actions being determined: indeterminism simply denies that all events are determined.

[5] There is also the question of which theories of free will are compatible with indeterminism , which relates to the worry for libertarians below.

[6] See Peter van Inwagen’s An Essay on Free Will for such a view.

[7] Eleonore Stump develops such a view in chapter 9 of Aquinas , and Robert Kane develops such a view in his The Significance of Free Will.

[8] Peter van Inwagen provides a detailed argument for this claim in chapter 3 of An Essay on Free Will . See also further developments by Alicia Finch and Ted Warfield in “The Mind Argument and Libertarianism.” Kadri Vihvelin provides a compatibilist reply in “How to Think About the Free Will/Determinism Problem.”

[9] This view has no relation whatsoever to the political theory called libertarianism .

[10] See chapter 3 of Neil Levy’s Hard Luck more a more careful statement of the problem and see chapters 6-7 of Helen Steward’s A Metaphysics for Freedom for an incompatibilist reply.

[11] Derk Pereboom’s Living Without Free Will defends a view he calls “hard incompatibilism” that agrees with hard determinism’s conclusion that we lack free will, but comes at it in a different way. Rather than hold that determinism is true and that is why we lack free will, they argue that we lack free will for other reasons, e.g., that we lack evidence that any of us satisfy the requirements in (A) or (B), or that concerns about moral luck give us reason to think that nobody has the kind of free will required for moral responsibility.

There are few explicit defenses of hard determinism, although many incompatibilists fear that they might end up becoming hard determinists since, for all we know, physicists could announce tomorrow that they have discovered that our world is deterministic. In light of worries like these, Manuel Vargas makes an alternative proposal in Building Better Beings : we should acknowledge that we have some incompatibilist intuitions, but we should revise those intuitions in light of the fact that we lack evidence we have the kind of free will incompatibilists want.

[12] For discussion, see Free Will and Moral Responsibility by Chelsea Haramia. Here we have focused on whether free will is compatible with determinism (and indeterminism) or not, with compatiblist and incompatiblist theories of free will, but there are distinct, but very much related, questions of whether moral responsibility is compatible with determinism (and indeterminism) or not, with compatiblist and incompatiblist theories of moral responsibility. And there are still further questions about the relationship between moral responsibility and free will: many think that we are morally responsible only when we act on free will, but some argue that moral responsibility does not require free will.

[13] Gary Watson’s “Free Agency” and Susan Wolf’s Freedom Within Reason develop theories in this vein. So does Harry Frankfurt in The Importance of What We Care About , although he focuses on coherence between a person’s actual desires, and the desires she wishes to have : when they match, a person identifies with her desires.

[14] See John Marin Fischer and Mark Ravizza’s Responsibility and Control for a such a view, and Dana Nelkin’s Making Sense of Freedom and Responsibility for a proposal in a similar spirit.

[15] Although the most widely accepted interpretation of quantum mechanics (the Copenhagen interpretation) is indeterministic, some live competitors, like the many worlds interpretation or the de Broglie-Bohm interpretation, are deterministic. For discussion, see Quantum Mechanics and Philosophy III: Implications by Thomas Metcalf.

[16] Coercion involves an unwilling subject, but here we can suppose that our subject did not will one way or another prior to the manipulation.

[17] For discussion, see Alternate Possibilities and Moral Responsibility by Rachel Bourbaki . See also chapter 4 (especially pages 110-117) of Derk Pereboom’s Living Without Free Will for a fuller statement of this kind of problem, as well as Kristin Demetriou’s “The Soft-Line Solution to Pereboom’s Four-Case Argument” and Tomis Kapitan’s “Autonomy and Manipulated Freedom” for compatibilist responses to this worry.

[18] Thanks to Andrew Chapman, Nathan Nobis and Chelsea Haramia for helpful comments which improved this essay.

Demetriou, Kristin (2010). “The Soft-Line Solution to Pereboom’s Four-Case Argument.” Australasian Journal of Philosophy 88(4): 595-617.

Finch, Alicia and Ted A. Warfield (1998). “The Mind Argument and Libertarianism.” Mind 107(427): 515-528.

Fischer, John Martin and Mark Ravizza (1998). Responsibility and Control . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Frankfurt, Harry (1988). The Importance of What We Care About . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kapitan, Tomis (2000). “Autonomy and Manipulated Freedom.” Philosophical Perspectives 14: 81-104.

Kane, Robert (1998). The Significance of Free Will . Oxford University Press.

Levy, Neil (2011). Hard Luck . New York: Oxford University Press.

Nelkin, Dana (2011). Making Sense of Freedom and Responsibility . New York: Oxford University Press.

Pereboom, Derk (2001). Living Without Free Will . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Steward, Helen (2012). A Metaphysics for Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press.

Stump, Eleonore (2003). Aquinas . New York: Routledge.

van Inwagen, Peter (1983). An Essay on Free Will . New York: Oxford University Press.

Vargas, Manuel (2013). Building Better Beings. New York: Oxford University Press.

Vihvelin, Kadri (2011). “How to Think About the Free Will/Determinism Problem.” In Michael O’Rourke, Joseph Keim Campbell and Matthew H. Slater (eds.), Carving Nature at Its Joints , 314- 340. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Watson, Gary (1975). “Free Agency.” Journal of Philosophy 72(8): 205-220.

Wolf, Susan (1990). Freedom Within Reason . New York: Oxford University Press.

Related Essays

Free Will and Moral Responsibility by Chelsea Haramia

Praise and Blame by Daniel Miller

Alternate Possibilities and Moral Responsibility by Rachel Bourbaki

Manipulation and Moral Responsibility by Taylor W. Cyr

Attributes of God by Bailie Peterson

Quantum Mechanics and Philosophy III: Implications by Thomas Metcalf

Moral Luck by Jonathan Spelman

Possibility and Necessity: An Introduction to Modality by Andre Leo Rusavuk

The Problem of Evil by Thomas Metcalf

Theories of Punishment by Travis Joseph Rodgers

Revision History

This essay, posted 12/24/18, is a revised version of an essay originally posted 4/3/2014.

PDF Download

Download this essay in PDF .

About the Author

Jonah is a graduate student at the University of California, Riverside. He is a graduate of Northern Illinois University (M.A.) and Biola University (B.A.), and has interests in metaphysics, especially the metaphysics of free will. http://philosophy.ucr.edu/jonah-nagashima

Follow 1000-Word Philosophy on Facebook , Twitter and subscribe to receive email notice of new essays at the bottom of 1000WordPhilosophy.com

Share this:, 8 thoughts on “ free will and free choice ”.

- Pingback: Free Will and Moral Responsibility | 1000-Word Philosophy

- Pingback: Quantum Mechanics and Philosophy II: Measurement and Interpretations | 1000-Word Philosophy

- Pingback: Attributes of God – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Ignorance and Blame – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Online Philosophy Resources Weekly Update - Daily Nous

- Pingback: The Problem of Evil – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Praise and Blame – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Kant’s Theory of the Sublime – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Comments are closed.

Discover more from 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

30 Existence of Free Will

Determinism and freedom.

Determinism and free will are often thought to be in deep conflict. Whether or not this is true has a lot to do with what is meant by determinism and an account of what free will requires.

First of all, determinism is not the view that free actions are impossible. Rather, determinism is the view that at any one time, only one future is physically possible. To be a little more specific, determinism is the view that a complete description of the past along with a complete account of the relevant laws of nature logically entails all future events. 1

Indeterminism is simply the denial of determinism. If determinism is incompatible with free will, it will be because free actions are only possible in worlds in which more than one future is physically possible at any one moment in time. While it might be true that free will requires indeterminism, it’s not true merely by definition. A further argument is needed and this suggests that it is at least possible that people could sometimes exercise the control necessary for morally responsible action, even if we live in a deterministic world.

It is worth saying something about fatalism before we move on. It is really easy to mistake determinism for fatalism, and fatalism does seem to be in straightforward conflict with free will. Fatalism is the view that we are powerless to do anything other than what we actually do. If fatalism is true, then nothing that we try or think or intend or believe or decide has any causal effect or relevance as to what we actually end up doing.

But note that determinism need not entail fatalism. Determinism is a claim about what is logically entailed by the rules/laws governing a world and the past of said world. It is not the claim that we lack the power to do other than what we actually were already going to do. Nor is it the view that we fail to be an important part of the causal story for why we do what we do. And this distinction may allow some room for freedom, even in deterministic worlds.

An example will be helpful here. We know that the boiling point for water is 100°C. Suppose we know in both a deterministic world and a fatalistic world that my pot of water will be boiling at 11:22am today. Determinism makes the claim that if I take a pot of water and I put it on my stove, and heat it to 100°C, it will boil. This is because the laws of nature (in this case, water that is heated to 100°C will boil) and the events of the past (I put a pot of water on a hot stove) bring about the boiling water. But fatalism makes a different claim. If my pot of water is fated to boil at 11:22am today, then no matter what I or anyone does, my pot of water will boil at exactly 11:22am today. I could try to empty the pot of water out at 11:21. I could try to take the pot as far away from a heating source as possible. Nonetheless, my pot of water will be boiling at 11:22 precisely because it was fated that this would happen. Under fatalism, the future is fixed or preordained, but this need not be the case in a deterministic world. Under determinism, the future is a certain way because of the past and the rules governing said world. If we know that a pot of water will boil at 11:22am in a deterministic world, it’s because we know that the various causal conditions will hold in our world such that at 11:22 my pot of water will have been put on a heat source and brought to 100°C. Our deliberations, our choices, and our free actions may very well be part of the process that brings a pot of water to the boiling point in a deterministic world, whereas these are clearly irrelevant in fatalistic ones.

Three Views of Freedom

Most accounts of freedom fall into one of three camps. Some people take freedom to require merely the ability to “do what you want to do.” For example, if you wanted to walk across the room, right now, and you also had the ability, right now, to walk across the room, you would be free as you could do exactly what you want to do. We will call this easy freedom.

Others view freedom on the infamous “Garden of Forking Paths” model. For these people, free action requires more than merely the ability to do what you want to do. It also requires that you have the ability to do otherwise than what you actually did. So, If Anya is free when she decides to take a sip from her coffee, on this view, it must be the case that Anya could have refrained from sipping her coffee. The key to freedom, then, is alternative possibilities and we will call this the alternative possibilities view of free action.

Finally, some people envision freedom as requiring, not alternative possibilities but the right kind of relationship between the antecedent sources of our actions and the actions that we actually perform. Sometimes this view is explained by saying that the free agent is the source, perhaps even the ultimate source of her action. We will call this kind of view a source view of freedom.

Now, the key question we want to focus on is whether or not any of these three models of freedom are compatible with determinism. It could turn out that all three kinds of freedom are ruled out by determinism, so that the only way freedom is possible is if determinism is false. If you believe that determinism rules out free action, you endorse a view called incompatibilism. But it could turn out that one or all three of these models of freedom are compatible with determinism. If you believe that free action is compatible with determinism, you are a compatibilist.

Let us consider compatibilist views of freedom and two of the most formidable challenges that compatibilists face: the consequence argument and the ultimacy argument.

Begin with easy freedom. Is easy freedom compatible with determinism? A group of philosophers called classic compatibilists certainly thought so. 2 They argued that free will requires merely the ability for an agent to act without external hindrance. Suppose, right now, you want to put your textbook down and grab a cup of coffee. Even if determinism is true, you probably, right now, can do exactly that. You can put your textbook down, walk to the nearest Starbucks, and buy an overpriced cup of coffee. Nothing is stopping you from doing what you want to do. Determinism does not seem to be posing any threat to your ability to do what you want to do right now. If you want to stop reading and grab a coffee, you can. But, by contrast, if someone had chained you to the chair you are sitting in, things would be a bit different. Even if you wanted to grab a cup of coffee, you would not be able to. You would lack the ability to do so. You would not be free to do what you want to do. This has nothing to do with determinism, of course. It is not the fact that you might be living in a deterministic world that is threatening your free will. It is that an external hindrance (the chains holding you to your chair) is stopping from you doing what you want to do. So, if what we mean by freedom is easy freedom, it looks like freedom really is compatible with determinism.

Easy freedom has run into some rather compelling opposition, and most philosophers today agree that a plausible account of easy freedom is not likely. But, by far, the most compelling challenge the view faces can be seen in the consequence argument. 3 The consequence argument is as follows:

- If determinism is true, then all human actions are consequences of past events and the laws of nature.

- No human can do other than they actually do except by changing the laws of nature or changing the past.

- No human can change the laws of nature or the past.

- If determinism is true, no human has free will.

This is a powerful argument. It is very difficult to see where this argument goes wrong, if it goes wrong. The first premise is merely a restatement of determinism. The second premise ties the ability to do otherwise to the ability to change the past or the laws of nature, and the third premise points out the very reasonable assumption that humans are unable to modify the laws of nature or the past.

This argument effectively devastates easy freedom by proposing that we never act without external hindrances precisely because our actions are caused by past events and the laws of nature in such a way that we not able to contribute anything to the causal production of our actions. This argument also seems to pose a deeper problem for freedom in deterministic worlds. If this argument works, it establishes that, given determinism, we are powerless to do otherwise, and to the extent that freedom requires the ability to do otherwise, this argument seems to rule out free action. Note that if this argument works, it poses a challenge for both the easy and alternative possibilities view of free will.

How might someone respond to this argument? First, suppose you adopt an alternative possibilities view of freedom and believe that the ability to do otherwise is what is needed for genuine free will. What you would need to show is that alternative possibilities, properly understood, are not incompatible with determinism. Perhaps you might argue that if we understand the ability to do otherwise properly we will see that we actually do have the ability to change the laws of nature or the past.

That might sound counterintuitive. How could it possibly be the case that a mere mortal could change the laws of nature or the past? Think back to Quinn’s decision to spend the night before her exam out with friends instead of studying. When she shows up to her exam exhausted, and she starts blaming herself, she might say, “Why did I go out? That was dumb! I could have stayed home and studied.” And she is sort of right that she could have stayed home. She had the general ability to stay home and study. It is just that if she had stayed home and studied the past would be slightly different or the laws of nature would be slightly different. What this points to is that there might be a way of cashing out the ability to do otherwise that is compatible with determinism and does allow for an agent to kind of change the past or even the laws of nature. 4

But suppose we grant that the consequence argument demonstrates that determinism really does rule out alternative possibilities. Does that mean we must abandon the alternative possibilities view of freedom? Well, not necessarily. You could instead argue that free will is possible, provided determinism is false. 5 That is a big if, of course, but maybe determinism will turn out to be false.

What if determinism turns out to be true? Should we give up, then, and concede that there is no free will? Well, that might be too quick. A second response to the consequence argument is available. All you need to do is deny that freedom requires the ability to do otherwise.

In 1969, Harry Frankfurt proposed an influential thought experiment that demonstrated that free will might not require alternative possibilities at all (Frankfurt [1969] 1988). If he’s right about this, then the consequence argument, while compelling, does not demonstrate that no one lacks free will in deterministic worlds, because free will does not require the ability to do otherwise. It merely requires that agents be the source of their actions in the right kind of way. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Here is a simplified paraphrase of Frankfurt’s case:

Black wants Jones to perform a certain action. Black is prepared to go to considerable lengths to get his way, but he prefers to avoid unnecessary work. So he waits until Jones is about to make up his mind what to do, and he does nothing unless it is clear to him (Black is an excellent judge of such things) that Jones is going to decide not to do what Black wants him to do. If it does become clear that Jones is going to decide to do something other than what Black wanted him to do, Black will intervene, and ensure that Jones decides to do, and does do, exactly what Black wanted him to do. Whatever Jones’ initial preferences and inclinations, then, Black will have his way. As it turns out, Jones decides, on his own, to do the action that Black wanted him to perform. So, even though Black was entirely prepared to intervene, and could have intervened, to guarantee that Jones would perform the action, Black never actually has to intervene because Jones decided, for reasons of his own, to perform the exact action that Black wanted him to perform. (Frankfurt [1969] 1988, 6-7)

Now, what is going on here? Jones is overdetermined to perform a specific act. No matter what happens, no matter what Jones initially decides or wants to do, he is going to perform the action Black wants him to perform. He absolutely cannot do otherwise. But note that there seems to be a crucial difference between the case in which Jones decides on his own and for his own reasons to perform the action Black wanted him to perform and the case in which Jones would have refrained from performing the action were it not for Black intervening to force him to perform the action. In the first case, Jones is the source of his action. It the thing he decided to do and he does it for his own reasons. But in the second case, Jones is not the source of his actions. Black is. This distinction, thought Frankfurt, should be at the heart of discussions of free will and moral responsibility. The control required for moral responsibility is not the ability to do otherwise (Frankfurt [1969] 1988, 9-10).

If alternative possibilities are not what free will requires, what kind of control is needed for free action? Here we have the third view of freedom we started with: free will as the ability to be the source of your actions in the right kind of way. Source compatibilists argue that this ability is not threatened by determinism, and building off of Frankfurt’s insight, have gone on to develop nuanced, often radically divergent source accounts of freedom. 6 Should we conclude, then, that provided freedom does not require alternative possibilities that it is compatible with determinism? 7 Again, that would be too quick. Source compatibilists have reason to be particularly worried about an argument developed by Galen Strawson called the ultimacy argument (Strawson [1994] 2003, 212-228).

Rather than trying to establish that determinism rules out alternative possibilities, Strawson tried to show that determinism rules out the possibility of being the ultimate source of your actions. While this is a problem for anyone who tries to establish that free will is compatible with determinism, it is particularly worrying for source compatibilists as they’ve tied freedom to an agent’s ability to be source of its actions. Here is the argument:

- A person acts of her own free will only if she is the act’s ultimate source.

- If determinism is true, no one is the ultimate source of her actions.

- Therefore, if determinism is true, no one acts of her own free will. (McKenna and Pereboom 2016, 148) 8

This argument requires some unpacking. First of all, Strawson argues that for any given situation, we do what we do because of the way we are ([1994] 2003, 219). When Quinn decides to go out with her friends rather than study, she does so because of the way she is. She prioritizes a night with her friends over studying, at least on that fateful night before her exam. If Quinn had stayed in and studied, it would be because she was slightly different, at least that night. She would be such that she prioritized studying for her exam over a night out. But this applies to any decision we make in our lives. We decide to do what we do because of how we already are.

But if what we do is because of the way we are, then in order to be responsible for our actions, we need to be the source of how we are, at least in the relevant mental respects (Strawson [1994] 2003, 219). There is the first premise. But here comes the rub: the way we are is a product of factors beyond our control such as the past and the laws of nature ([1994] 2003, 219; 222-223). The fact that Quinn is such that she prioritizes a night with friends over studying is due to her past and the relevant laws of nature. It is not up to her that she is the way she is. It is ultimately factors extending well beyond her, possibly all the way back to the initial conditions of the universe that account for why she is the way she is that night. And to the extent that this is compelling, the ultimate source of Quinn’s decision to go out is not her. Rather, it is some condition of the universe external to her. And therefore, Quinn is not free.

Once again, this is a difficult argument to respond to. You might note that “ultimate source” is ambiguous and needing further clarification. Some compatibilists have pointed this out and argued that once we start developing careful accounts of what it means to be the source of our actions, we will see that the relevant notion of source-hood is compatible with determinism.

For example, while it may be true that no one is the ultimate cause of their actions in deterministic worlds precisely because the ultimate source of all actions will extend back to the initial conditions of the universe, we can still be a mediated source of our actions in the sense required for moral responsibility. Provided the actual source of our action involves a sophisticated enough set of capacities for it to make sense to view us as the source of our actions, we could still be the source of our actions, in the relevant sense (McKenna and Pereboom 2016, 154). After all, even if determinism is true, we still act for reasons. We still contemplate what to do and weigh reasons for and against various actions, and we still are concerned with whether or not the actions we are considering reflect our desires, our goals, our projects, and our plans. And you might think that if our actions stem from a history that includes us bringing all the features of our agency to bear upon the decision that is the proximal cause of our action, that this causal history is one in which we are the source of our actions in the way that is really relevant to identifying whether or not we are acting freely.

Others have noted that even if it is true that Quinn is not directly free in regard to the beliefs and desires that suggest she should go out with her friends rather than study (they are the product of factors beyond her control such as her upbringing, her environment, her genetics, or maybe even random luck), this need not imply that she lacks control as to whether or not she chooses to act upon them. 9 Perhaps it is the case that even though how we are may be due to factors beyond our control, nonetheless, we are still the source of what we do because it is still, even under determinism, up to us as to whether we choose to exercise control over our conduct.

Free Will and the Sciences

Many challenges to free will come, not from philosophy, but from the sciences. There are two main scientific arguments against free will, one coming from neuroscience and one coming from the social sciences. The concern coming from research in the neurosciences is that some empirical results suggest that all our choices are the result of unconscious brain processes, and to the extent choices must be consciously made to be free choices, it seems that we never make a conscious free choice.

The classic studies motivating a picture of human action in which unconscious brain processes are doing the bulk of the causal work for action were conducted by Benjamin Libet. Libet’s experiments involved subjects being asked to flex their wrists whenever they felt the urge to do so. Subjects were asked to note the location of a clock hand on a modified clock when they became aware of the urge to act. While doing this their brain activity was being scanned using EEG technology. What Libet noted is that around 550 milliseconds before a subject acted, a readiness potential (increased brain activity) would be measured by the EEG technology. But subjects were reporting awareness of an urge to flex their wrist around 200 milliseconds before they acted (Libet 1985).

This painted a strange picture of human action. If conscious intentions were the cause of our actions, you may expect to see a causal story in which the conscious awareness of an urge to flex your wrist shows up first, then a ramping up of brain activity, and finally an action. But Libet’s studies showed a causal story in which an action starts with unconscious brain activity, the subject later becomes consciously aware that they are about to act, and then the action happens. The conscious awareness of action seemed to be a byproduct of the actual unconscious process that was causing the action. It was not the cause of the action itself. And this result suggests that unconscious brain processes, not conscious ones, are the real causes of our actions. To the extent that free action requires our conscious decisions to be the initiating causes of our actions, it looks like we may never act freely.

While this research is intriguing, it probably does not establish that we are not free. Alfred Mele is a philosopher who has been heavily critical of these studies. He raises three main objections to the conclusions drawn from these arguments.

First, Mele points out that self-reports are notoriously unreliable (2009, 60-64). Conscious perception takes time, and we are talking about milliseconds. The actual location of the clock hand is probably much closer to 550 milliseconds when the agent “intends” or has the “urge” to act than it is to 200 milliseconds. So, there’s some concerns about experimental design here.

Second, an assumption behind these experiments is that what is going on at 550 milliseconds is that a decision is being made to flex the wrist (Mele 2014, 11). We might challenge this assumption. Libet ran some variants of his experiment in which he asked subjects to prepare to flex their wrist but to stop themselves from doing so. So, basically, subjects simply sat there in the chair and did nothing. Libet interpreted the results of these experiments as showing that we might not have a free will, but we certainly have a “free won’t” because we seem capable of consciously vetoing or stopping an action, even if that action might be initiated by unconscious processes (2014, 12-13). Mele points out that what might be going on in these scenarios is that the real intention to act or not act is what happens consciously at 200 milliseconds, and if so, there is little reason to think these experiments are demonstrating that we lack free will (2014, 13).

Finally, Mele notes that while it may be the case that some of our decisions and actions look like the wrist-flicking actions Libet was studying, it is doubtful that all or even most of our decisions are like this (2014, 15). When we think about free will, we rarely think of actions like wrist-flicking. Free actions are typically much more complex and they are often the kind of thing where the decision to do something extends across time. For example, your decision about what to major in at college or even where to study was probably made over a period of months, even years. And that decision probably involved periods of both conscious and unconscious cognition. Why think that a free choice cannot involve some components that are unconscious?

A separate line of attack on free will comes from the situationist literature in the social sciences (particularly social psychology). There is a growing body of research suggesting that situational and environmental factors profoundly influence human behavior, perhaps in ways that undermine free will (Mele 2014, 72).

Many of the experiments in the situationist literature are among the most vivid and disturbing in all of social psychology. Stanley Milgram, for example, conducted a series of experiments on obedience in which ordinary people were asked to administer potentially lethal voltages of electricity to an innocent subject in order to advance scientific research, and the vast majority of people did so! 10 And in Milgram’s experiments, what affected whether or not subjects were willing to administer the shocks were minor, seemingly insignificant environmental factors such as whether the person running the experiment looked professional or not (Milgram 1963).

What experiments like Milgram’s obedience experiments might show is that it is our situations, our environments that are the real causes of our actions, not our conscious, reflective choices. And this may pose a threat to free will. Should we take this kind of research as threatening freedom?

Many philosophers would resist concluding that free will does not exist on the basis of these kinds of experiments. Typically, not everyone who takes part in situationist studies is unable to resist the situational influences they are subject to. And it appears to be the case that when we are aware of situational influences, we are more likely to resist them. Perhaps the right way to think about this research is that there all sorts of situations that can influence us in ways that we may not consciously endorse, but that nonetheless, we are still capable of avoiding these effects when we are actively trying to do so. For example, the brain sciences have made many of us vividly aware of a whole host of cognitive biases and situational influences that humans are typically subject to and yet, when we are aware of these influences, we are less susceptible to them. The more modest conclusion to draw here is not that we lack free will, but that exercising control over our actions is much more difficult than many of us believe it to be. We are certainly influenced by the world we are a part of, but to be influenced by the world is different from being determined by it, and this may allow us to, at least sometimes, exercise some control over the actions we perform.

No one knows yet whether or not humans sometimes exercise the control over their actions required for moral responsibility. And so I leave it to you, dear reader: Are you free?

Chapter Notes

- I have hidden some complexity here. I have defined determinism in terms of logical entailment. Sometimes people talk about determinism as a causal relationship. For our purposes, this distinction is not relevant, and if it is easier for you to make sense of determinism by thinking of the past and the laws of nature causing all future events, that is perfectly acceptable to do.

- Two of the more well-known classic compatibilists include Thomas Hobbes and David Hume. See: Hobbes, Thomas, (1651) 1994, Leviathan , ed. Edwin Curley, Canada: Hackett Publishing Company; and Hume, David, (1739) 1978, A Treatise of Human Nature , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- For an earlier version of this argument see: Ginet, Carl, 1966, “Might We Have No Choice?” in Freedom and Determinism, ed. Keith Lehrer, 87-104, Random House.

- For two notable attempts to respond to the consequence argument by claiming that humans can change the past or the laws of nature see: Fischer, John Martin, 1994, The Metaphysics of Free Will , Oxford: Blackwell Publishers; and Lewis, David, 1981, “Are We Free to Break the Laws?” Theoria 47: 113-21.

- Many philosophers try to develop views of freedom on the assumption that determinism is incompatible with free action. The view that freedom is possible, provided determinism is false is called Libertarianism. For more on Libertarian views of freedom, see: Clarke, Randolph and Justin Capes, 2017, “Incompatibilist (Nondeterministic) Theories of Free Will,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/incompatibilism-theories/ .

- For elaboration on recent compatibilist views of freedom, see McKenna, Michael and D. Justin Coates, 2015, “Compatibilism,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/compatibilism/ .

- You might be unimpressed by the way source compatibilists understand the ability to be the source of your actions. For example, you might that what it means to be the source of your actions is to be the ultimate cause of your actions. Or maybe you think that to genuinely be the source of your actions you need to be the agent-cause of your actions. Those are both reasonable positions to adopt. Typically, people who understand free will as requiring either of these abilities believe that free will is incompatible with determinism. That said, there are many Libertarian views of free will that try to develop a plausible account of agent causation. These views are called Agent-Causal Libertarianism. See: Clarke, Randolph and Justin Capes, 2017, “Incompatibilist (Nondeterministic) Theories of Free Will,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/incompatibilism-theories/ .

- As with most philosophical arguments, the ultimacy argument has been formulated in a number of different ways. In Galen Strawson’s original paper he gives three different versions of the argument, one of which has eight premises and one that has ten premises. A full treatment of either of those versions of this argument would require more time and space than we have available here. I have chosen to use the McKenna/Pereboom formulation of the argument due its simplicity and their clear presentation of the central issues raised by the argument.

- For two attempts to respond to the ultimacy argument in this way, see: Mele, Alfred, 1995, Autonomous Agents , New York: Oxford University Press; and McKenna, Michael, 2008, “Ultimacy & Sweet Jane” in Nick Trakakis and Daniel Cohen, eds, Essays on Free Will and Moral Responsibility , Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing: 186-208.

- Fortunately, no real shocks were administered. The subjects merely believed they were doing so.

Frankfurt, Harry. (1969) 1988. “Alternative Possibilities and moral responsibility.” In The Importance of What We Care About: Philosophical Essays , 10th ed. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Libet, Benjamin. 1985. “Unconscious Cerebral Initiative and the Role of Conscious Will in Voluntary Action.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 8: 529-566.

McKenna, Michael and Derk Pereboom. 2016. Free Will: A Contemporary Introduction. New York: Routledge.

Mele, Alfred. 2014. Free: Why Science Hasn’t Disproved Free Will . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mele, Alfred. 2009. Effective Intentions: The Power of Conscious Will. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Milgram, Stanley. 1963. “Behavioral Study of Obedience.” The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 67: 371-378.

Strawson, Galen. (1994) 2003. “The Impossibility of Moral Responsibility.” In Free Will, 2nd ed. Edited by Gary Watson, 212-228. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

van Inwagen, Peter. 1983. An Essay on Free Will. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Further Reading

Deery, Oisin and Paul Russell, eds. 2013. The Philosophy of Free Will: Essential Readings from the Contemporary Debates . New York: Oxford University Press.

Mele, Alfred. 2006. Free Will and Luck. New York: Oxford University Press.

Attribution

This section is composed of text taken from Chapter 8 Freedom of the Will created by Daniel Haas in Introduction to Philosophy: Philosophy of Mind , edited by Heather Salazar and Christina Hendricks, and produced with support from the Rebus Community. The original is freely available under the terms of the CC BY 4.0 license at https://press.rebus.community/intro-to-phil-of-mind/ . The material is presented in its original form, with the exception of the removal of introductory material Introduction: Are We Free?

A Brief Introduction to Philosophy Copyright © 2021 by Southern Alberta Institution of Technology (SAIT) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- Home ›

- Reviews ›

Thinking about Free Will

Peter van Inwagen, Thinking about Free Will , Cambridge University Press, 2017, 232pp., $99.99 (hbk), ISBN 9781316617656.

Reviewed by Peter A. Graham, University of Massachusetts Amherst

No one writes more sensibly about the traditional philosophical problem of free will than does Peter van Inwagen. This book, a collection of his essays on free will, ought to join his An Essay on Free Will , the best modern treatment of the topic, on the shelf of anyone seriously considering the cluster of issues which constitute the traditional philosophical problem of free will. It is an excellent volume.

In what follows I’ll first very briefly canvas some of the main issues touched upon in the essays and then discuss one of them -- the most important, in my view -- in a bit more depth.

Among that which is defended in Thinking about Free Will are the theses that:

- Frankfurt’s famous counterexample notwithstanding, whether being able to do otherwise than one in fact does is compatible with determinism is relevant to the question whether blameworthiness and determinism are compatible (chapters 1 and 6),

- because of the joint plausibility of the Consequence Argument and the Mind Argument, free will remains a mystery (chapters 7 and 10),

- the terminology used in much of the contemporary free will debate (including the phrase “free will” itself) obscures the real philosophical issues at play in the traditional philosophical problem of free will (chapters 12 and 13),

- the notion of ability central to the traditional philosophical problem of free will is one intimately connected with a certain conception of a defective promise (chapters 7, 11, and 14),

- rarely are we ever in a situation such that we are able to do otherwise than we in fact do (chapter 5), and

- David Lewis’s response to the Consequence Argument in his “Are We Free to Break the Laws?” fails (chapter 9).

This is not all that is defended in the essays, but it constitutes, in my view, that of what is defended therein which is most interesting. There is indeed a fair amount of overlap across the various essays, but this is a feature rather than a bug, for much of what is repeated bears repeating. Aside from the last of them, I don’t propose to explore in any detail van Inwagen’s arguments for the above-listed theses. I do, however, want to push back on van Inwagen’s response to Lewis’s reply to the Consequence Argument, and I’ll spend the rest of this review doing just that.

I share van Inwagen’s admiration for David Lewis’s “Are We Free to Break the Laws?”. (I concur with him in his assessment that it is “the finest essay that has ever been written in defense of compatibilism -- possibly the finest essay that has ever been written about any aspect of the free will problem” (p. 152)). In what follows I shall reiterate the reply to the Consequence Argument Lewis presents in that paper [1] and offer a rebuttal on behalf of Lewis to van Inwagen’s response to it in his “Freedom to Break the Laws” (chapter 9).

The Consequence Argument, in whichever form one considers, derives the incompatibility of determinism and our having the ability to act otherwise than we in fact act from our inabilities both to affect the past and to affect the laws of nature. The essence of Lewis’s reply to this argument is to point out that there is a sense -- and, importantly, a nonstandard sense -- of having the ability to affect the past and having the ability to affect the laws of nature which is such that it is not at all counterintuitive to suppose that we have those abilities, and that it is only our having those abilities in such a nonstandard sense that our having the ability to do otherwise in a deterministic world entails.

It most certainly is intuitive that I’m unable to affect or change the past. For instance, I’m not able to change or affect the fact that Anne Boleyn was beheaded. It’s also quite plausible that I’m unable to affect or change the laws of nature. For instance, I’m unable to change or affect the fact that angular momentum is conserved. Lewis concurs. But Lewis also points out that my being able to affect or change something, in its standard sense, is my having the ability to make it the case that the thing in question is otherwise than it in fact is. And this notion of making something the case, as we ordinarily understand it, is one that has either a causal or a constitutive sense. I am able to make it the case that a certain window is broken -- i.e., I am able to break the window -- only in virtue of my being able to do something such that were I to do it my doing it would cause the window’s breaking. I am able to make it the case that my arm rises -- i.e., I am able to raise my arm -- only in virtue of my being able to do something such that were I to do it my doing it would be my raising my arm. Whenever we make it the case that something happens, we do so by doing something that either causes that thing to happen or constitutes that thing’s happening, and so our having the ability to make something happen is our having the ability to do something that causes or constitutes that thing’s happening.

What is intuitive about our inabilities with respect to the laws of nature and the past is that we aren’t able to make it the case that these things are otherwise than they actually are. But, and here’s Lewis’s point, we needn’t be able to make it the case that a law of nature is broken, or that the past is different from how it actually was for us, to be able to have the ability to do otherwise than we in fact do in a deterministic world.

Suppose the actual world, @, is deterministic and that I fail to raise my hand at t 1 . Supposing also that I have the ability to raise my hand at t 1 , though it does entail that I have the ability to do something such that, were I to do it, a law of nature would be broken, [2] needn’t entail that I have the ability to make it the case that a law of nature is broken. Remember, my having the ability to make it the case that a law of nature is broken would be for me to have the ability to do something such that, were I to do it, my doing it either would be or would cause a law-breaking event. But we can suppose that I am able to raise my hand at t 1 in @ without supposing that I am able to do something such that, were I to do it, my doing it either would be or would cause a law-breaking event. All we need suppose is that were I to exercise the ability I have in @ to raise my hand at t 1 , the miraculous event, m , in non-actual possible world, w , that would indeed occur were I to exercise my ability to raise my hand would occur sometime shortly prior to t 1 , at t 0 , say, and not be caused by my raising of my hand at t 1 in w . So long as the event of my raising my hand, r , is neither identical with, nor causes, m in w (rather, it would be m which causes r in w ), my having the ability in @ to raise my hand at t 1 doesn’t entail that I am able to make it the case that m , or any other law-breaking event, occurs.

Van Inwagen complains of this reply that it is, in effect, to attribute to us, ordinary everyday agents such as you and me, the ability to perform miracles. And no one has the ability to perform a miracle. Lewis would agree that no one has the ability to perform miracles. But, he’d go on to note, having the ability to perform a miracle is the ability to make it the case that a miracle happens, and as he’s shown, one can have the ability to do something other than what one actually does in a deterministic world without thereby having the ability to make it the case that a miracle happens. On Lewis’s view having the ability to do otherwise than one in fact does in a deterministic world also entails having the ability to do something such that, were one to do it, the recent (though not the distant) past would have been different from how it actually was. But again, as m would occur prior to, and not be caused by, r in w , this ability would not be an ability to make it the case that the past is different from how it actually was.

I imagine van Inwagen would respond to this as follows: “Fine. Having the ability to do otherwise than one in fact does in a deterministic world doesn’t entail having the ability to make it the case that a miracle occurs. Nevertheless, it does entail that one have the ability to do something such that were one to do it a miracle would occur. And that -- just that! -- is implausible.” Here, Lewis would demur. “No, it’s not implausible that one have such an ability. All that’s intuitive is that we’re unable to make it the case that a miracle occurs. And that’s because our ordinary and intuitive notion of being able to do something -- the only notion we can be said to have any robust intuitions with respect to -- is the constitutive/causal notion of being able to make something be the case. We have no robust intuitions (if we have any intuitions at all) as regards other purely counterfactual relations between our abilities to do things and the laws of nature and the past.”

What’s more, we can even give some support to Lewis’s contention that we have the ability to do something such that, were we to do it, the past would have been different from how it in fact was, and thereby support the claim that we have the ability to do something such that, were we to do it, the laws of nature would have been different from how they in fact are. Consider the following. In front of Alice is a button. She has no desire whatsoever to press the button at or before t 1 . In fact, she has no desire whatsoever that could rationalize (to use Davidson’s phrase) her pressing the button at or before t 1 . And so, she doesn’t press the button at t 1 . But then we ask her: “Hey Alice, were you able to press the button at t 1 ?” Her reply: “Of course! In fact, I was indeed musing about pressing the button right up until t 1 , but, having no desire whatsoever to press it, opted against it.” We say: “You say you had no desire to press the button leading up to t 1 ?” “True enough,” she replies. “So would you have wanted to press the button at t 1 just prior to t 1 had you pressed the button at t 1 ?” “Yeah, I would. Why would I press it if I didn’t?” “So you’re saying you had the ability to do something such that, were you to have done it, the past prior to your doing it would have been slightly different than it actually was -- you would have had a desire which you in fact lacked?” “Yeah. That seems right. I guess I did have that ability.”

In our story above we conclude that Alice has the ability to do something, namely press the button, such that, were she to do it, the (very recent) past would have been different from how it actually was. And we reasoned our way to that conclusion from some innocuous assumptions: that she was able to press the button at t 1 and that she lacked a desire to press it at and before t 1 . [3] (Note, in our story, nowhere did we assume either that determinism was true or that it was false.) But if we can support the thought that Alice might indeed have the ability to do something such that, were she to do it, the (recent) past would have been different from how it actually was despite the utter obviousness that she doesn’t have the ability to make it the case that the past (even the recent past) is different from how it actually was, then so too can we see how we might have the ability to do something such that, were we to do it, a law of nature would have been broken, even despite the sheer obviousness of our being unable to make it the case that a law of nature is broken.

(We can most certainly describe the ability to do something such that, were one to do it, a miracle would occur, as a way of being able to perform a miracle, if we like. But so describing it would not be the ordinary, standard understanding of what it is to have the ability to perform a miracle. And so, as that’s the case, Lewis can grant the proponent of the Consequence Argument that being able to do otherwise than one in fact does in a deterministic world entails having the ability to perform a miracle in that sense. But granting that is not a serious cost, because it isn’t intuitive that people lack the ability to perform miracles in that nonstandard sense of the phrase.)

Lewis’s reply to the Consequence Argument is subtle, but it is decisive. He has located its Achilles heel and shot an arrow straight through it. Does the demise of the Consequence Argument establish Compatibilism? Certainly not. At most, the Lewisian reply merely undermines the best argument for Incompatibilism extant. That’s no small feat, however. And in the absence of any argument for Incompatibilism, Compatibilism’s prospects are no worse than that of its denial. [4]

Lewis gets the better of van Inwagen when it comes to the Consequence Argument. This notwithstanding, van Inwagen’s defenses of the Consequence Argument and of all the theses for which he advocates in Thinking about Free Will are significant and very important. For anyone interested in the traditional philosophical problem of free will, one can do no better, aside from reading Lewis’s “Are We Free to Break the Laws?”, than study closely van Inwagen’s An Essay on Free Will and Thinking about Free Will .

[1] Though I shall do this using terminology somewhat different from that used by Lewis in his presentation of the reply, I take it that what I shall present is his reply in its essence. To the degree that I fail to do it justice, that is more a reflection of my own limited philosophical acumen than it is of the merits of the Lewisian reply itself.

[2] More precisely, it entails that I have the ability to do something such that, were I to do it, either a law would be broken or the entire past would have been different from how it in fact was. But if we also suppose (as Lewis does) that I don’t have the ability to do something such that, were I to do it, the entire past would have been different from how it in fact was, we can grant that having the ability to do otherwise than one in fact does in a deterministic world does entail having the ability to do something such that were one to do it a law of nature would be broken.

[3] This is not the conclusion van Inwagen would draw from our story. In fact, he’d say that because she had no desire to press the button, Alice was not able at t 1 to press the button. This, after all, is one of the conclusions of his “When Is the Will Free?” (chapter 5). But here we’ve reached an important philosophical decision point. Which is more plausible: that a person have the ability to do something even when they lack a desire to do it, or that one not be able to do something such that were she to do it the (recent) past would have been slightly different from how it actually was? Because it seems quite plausible that having the ability to do something at a time does not simply vanish when one lacks a desire to do it, reasoning from that to the claim that one sometimes is able to act in such a way that the (recent) past would have been slightly different from how it actually was (an ability it is not intuitive that we don’t have) is on surer ground than is arguing the other way around from the impossibility of being able to act in such a way that the (recent) past would have been slightly different from how it actually was to its being impossible to have the ability to do something when one lacks a desire to do it.

[4] In fact, one might think that in the absence of an argument for Incompatibilism, Compatibilism’s prospects are even slightly better than those of its denial. For, on very general philosophical grounds, you might think, in the absence of a reason to think that two things are incompatible, it’s more plausible to think that they’re compatible rather than not.

There’s No Such Thing as Free Will

But we’re better off believing in it anyway.

F or centuries , philosophers and theologians have almost unanimously held that civilization as we know it depends on a widespread belief in free will—and that losing this belief could be calamitous. Our codes of ethics, for example, assume that we can freely choose between right and wrong. In the Christian tradition, this is known as “moral liberty”—the capacity to discern and pursue the good, instead of merely being compelled by appetites and desires. The great Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant reaffirmed this link between freedom and goodness. If we are not free to choose, he argued, then it would make no sense to say we ought to choose the path of righteousness.

Today, the assumption of free will runs through every aspect of American politics, from welfare provision to criminal law. It permeates the popular culture and underpins the American dream—the belief that anyone can make something of themselves no matter what their start in life. As Barack Obama wrote in The Audacity of Hope , American “values are rooted in a basic optimism about life and a faith in free will.”

So what happens if this faith erodes?

The sciences have grown steadily bolder in their claim that all human behavior can be explained through the clockwork laws of cause and effect. This shift in perception is the continuation of an intellectual revolution that began about 150 years ago, when Charles Darwin first published On the Origin of Species . Shortly after Darwin put forth his theory of evolution, his cousin Sir Francis Galton began to draw out the implications: If we have evolved, then mental faculties like intelligence must be hereditary. But we use those faculties—which some people have to a greater degree than others—to make decisions. So our ability to choose our fate is not free, but depends on our biological inheritance.

Explore the June 2016 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Galton launched a debate that raged throughout the 20th century over nature versus nurture. Are our actions the unfolding effect of our genetics? Or the outcome of what has been imprinted on us by the environment? Impressive evidence accumulated for the importance of each factor. Whether scientists supported one, the other, or a mix of both, they increasingly assumed that our deeds must be determined by something .

In recent decades, research on the inner workings of the brain has helped to resolve the nature-nurture debate—and has dealt a further blow to the idea of free will. Brain scanners have enabled us to peer inside a living person’s skull, revealing intricate networks of neurons and allowing scientists to reach broad agreement that these networks are shaped by both genes and environment. But there is also agreement in the scientific community that the firing of neurons determines not just some or most but all of our thoughts, hopes, memories, and dreams.

We know that changes to brain chemistry can alter behavior—otherwise neither alcohol nor antipsychotics would have their desired effects. The same holds true for brain structure: Cases of ordinary adults becoming murderers or pedophiles after developing a brain tumor demonstrate how dependent we are on the physical properties of our gray stuff.

Many scientists say that the American physiologist Benjamin Libet demonstrated in the 1980s that we have no free will. It was already known that electrical activity builds up in a person’s brain before she, for example, moves her hand; Libet showed that this buildup occurs before the person consciously makes a decision to move. The conscious experience of deciding to act, which we usually associate with free will, appears to be an add-on, a post hoc reconstruction of events that occurs after the brain has already set the act in motion.

The 20th-century nature-nurture debate prepared us to think of ourselves as shaped by influences beyond our control. But it left some room, at least in the popular imagination, for the possibility that we could overcome our circumstances or our genes to become the author of our own destiny. The challenge posed by neuroscience is more radical: It describes the brain as a physical system like any other, and suggests that we no more will it to operate in a particular way than we will our heart to beat. The contemporary scientific image of human behavior is one of neurons firing, causing other neurons to fire, causing our thoughts and deeds, in an unbroken chain that stretches back to our birth and beyond. In principle, we are therefore completely predictable. If we could understand any individual’s brain architecture and chemistry well enough, we could, in theory, predict that individual’s response to any given stimulus with 100 percent accuracy.

This research and its implications are not new. What is new, though, is the spread of free-will skepticism beyond the laboratories and into the mainstream. The number of court cases, for example, that use evidence from neuroscience has more than doubled in the past decade—mostly in the context of defendants arguing that their brain made them do it. And many people are absorbing this message in other contexts, too, at least judging by the number of books and articles purporting to explain “your brain on” everything from music to magic. Determinism, to one degree or another, is gaining popular currency. The skeptics are in ascendance.

This development raises uncomfortable—and increasingly nontheoretical—questions: If moral responsibility depends on faith in our own agency, then as belief in determinism spreads, will we become morally irresponsible? And if we increasingly see belief in free will as a delusion, what will happen to all those institutions that are based on it?