Karachi, Pakistan: Exploring The City of Lights

- Author david

- Date October 30th, 2021

Situated on Pakistan’s Arabian Sea coast in the country’s Sindh province is the capital city of Karachi. Pakistan’s largest city and the twelfth-largest city in the world, Karachi the city of lights is considered a beta-global city. It’s also an ethnically and religiously diverse city, as well as the country’s most cosmopolitan city in southern pakistan. That makes the best things to do in Karachi, Pakistan equally varied and unique!

Karachi has been inhabited for over a thousand years, though it was officially founded in 1729 as Kolachi. Then a fortified village, Kolachi’s importance grew rapidly after the British East Indian Company arrived in the mid-19 th century.

The British transformed the city into a transportation hub by connecting it to the rail system (Karachi Cantonment Station) and the extensive rail network they’d built throughout the Indian subcontinent, and turning it into a prominent port city.

Over the years, Karachi has played a crucial role in the political landscape, becoming a focal point for major political parties.

After Pakistan won its independence in 1947, Karachi, now recognized as the seventh most prominent city, grew further as hundreds of thousands of Muslim refugees from India flooded the city during the Partition. It continued its economic growth in the years that followed, as Muslim immigrants arrived from across South Asia.

Now Pakistan’s top financial and industrial center, and a vibrant nightlife destination, Karachi is known as karachi the city of lights. I loved my time in this incredible city, which really is world-class in many aspects. To explore the city, I teamed up with the amazing people at Manaky , a curated travel marketplace dedicated to creating unforgettable experiences for people traveling through Pakistan. They were a dream to work with and really made my time in Karachi truly special.

The people in Karachi are among the friendliest I’ve ever met in my life and the cuisine blew me away. It’s a true traveler’s dream and a city I think everyone should experience at least once. These are the top 20 things you must do in Karachi, Pakistan!

Go on a Breakfast Street Food Tour

You can’t talk about the top things to do in Karachi, Pakistan without mentioning a breakfast food tour. Early on my first morning in the city, my guide Furqan took me on a diverse and wide-reaching tour, starting with Karachi’s King of Parathas at Quetta Alamgir Hotel!

Quetta Alamgir Hotel

This famous cook is known for cooking up hundreds of lachha parathas in a massive, circular pan just feet from the street. These flaky, layered, pan-fried flatbreads pair well with omelets and a chickpea and masala mixture called chana.

These flaky, crispy, golden-brown parathas are quite similar to the parottas you’ll find in southern India. I recommend tearing off a bit and eating it with the fiery, fluffy omelet and hearty chana.

It’s honestly a mixture you can’t beat. The mix of contrasting textures and mouthwatering flavors is the best way to kick off your day. Add some chai for a scorching and frothy treat!

Quetta Alamgir Hotel Alamgir Rd, Delhi Mercantile Society Karachi, Karachi City Sindh, Pakistan +92 21 34926333

Sialkot Milk Centre

After your spicy breakfast, you’ll probably need some dairy to cool down the fire lingering in your mouth. For that, head over to a popular spot called Sialkot Milk Centre, which offers baked goods, milkshakes, and yes, lassi.

Lassi is a yogurt-based drink that’s often enjoyed after a spicy meal in Pakistan and India. It comes in many different flavors, thicknesses, and styles across the subcontinent. The lactose helps temper the heat on your tongue and coats your stomach to aid in digestion. Plus, the creamy texture is just plain delicious!

Sialkot Milk Centre Apartment, West Land Apartments Ismail Naineetalwala Chowrangi Bahadurabad Bahadur Yar Jang CHS Karachi, Karachi City Sindh, Pakistan

Visit Frere Hall

If you’re a history buff like me, you may want to break up your food adventures with a visit to one of Karachi’s most notable landmarks. In the colonial-era Saddar Town in the center of the city, you’ll find Frere Hall, a British colonial building that dates back to 1865.

Frere Hall was built in the Venetian-Gothic architectural style, but blends elements of local and British architecture. It was initially was built to serve as the town hall, but it now operates as a library and exhibition space. The library inside, Liaquat National Library, is one of the largest in Karachi. It’s home to over 70,000 books, including rare manuscripts.

Frere Hall is surrounded by a large park with lots of benches and street food vendors. The vendors sell chaats and a delicious cross between ice cream and sorbet called kulfi. The kulfi is dense and creamy, and contains caramel and nuts. It’s a great way to cool off in the Pakistani heat and one of my favorite things to do in Karachi, Pakistan!

Frere Hall Fatima Jinnah Road Saddar Civil Lines Karachi, Karachi City Sindh, Pakistan

Eat a Bun Kabab at Super Foods & Biryani Center

As you explore the streets of Karachi, you may come across a number of cooks preparing and stacking a massive number of fluffy, pancake-like egg patties on the edge of a grill. The egg patties are for a dish called bun kababs, which is a small sandwich consisting of kebab meat, egg, onions, and green chili chutney inside a white bun.

One of the best city to see this spectacle—and try a bun kabab—is Super Foods & Biryani Center. You can take your food to go if you wish, or you can eat in their dining area upstairs. I recommend sitting down and eating them.

The bun kababs are essentially slider-like breakfast sandwiches. The crispy and airy bun, coupled with the fluffy eggs, and the kick of heat from the chutney is outstanding. If you wish, you can add more onions and chutney, which are provided on the side. The onions add a nice touch of acidity and help bring the whole dish together! Having one is another thing you must do in Karachi, Pakistan!

Super Foods & Biryani Center Plot R 1340 Federal B Area Block 15 Gulberg Town, Karachi, Karachi City Sindh, Pakistan

Visit the Shrine of Abdullah Shah Ghazi

When you travel to Karachi, one of the must-visit localities is the Clifton neighborhood. It’s a bustling, wealthy seaside area full of restaurants and street vendors. It’s also home to the Shrine of Abdullah Shah Ghazi, a Muslim mystic and Sufi from the 8 th century.

Ghazi was a descendent of the prophet Mohammed and visited the area to spread Islam. After being killed by his enemies in the interior of the Sindh Province, Ghazi’s devotees buried him on a hill near Clifton Beach. The present-day shrine, the most visited in the country, was built around his grave 1,000 years later.

Keep in mind that, while the shrine is beautiful, you can only film and take photographs of the exterior. Cameras are not allowed inside, but phones are. If you visit, remember to be respectful of the rules as you marvel at the building’s beauty.

Shrine of Abdullah Shah Ghazi Block 4 Block 3 Clifton Karachi, Karachi City Sindh, Pakistan

Explore the Street Food on Burns Road

If you don’t explore the Pakistani street food on Burns Road while you’re in Karachi, you didn’t experience Karachi properly. From small holes-in-the-wall selling kachori, potato curry, dal, and achar to vendors grilling chargha (chicken stacked vertically on spits and arranged in a circle) to much more, you can find it all there!

The great thing about Burns Road is that they close half of the road to traffic nightly after 6 p.m. At that time, each restaurant along the road extends its seating out into the street to allow for the bustling dinner rush. It’s a great concept and one I personally enjoyed a lot!

New Delhi Gola Kebab House

My guide Furqan and I were sure to stop at New Delhi Gola Kebab House, an incredible spot that sells some of the best kebabs I ate in Pakistan. We ordered chicken kebabs, dhaga kebabs (a type of soft, minced seekh kebab), kebab fry, and a tender and smoky dish called khiri with parathas and chili chutney.

With so many dishes, I barely knew where to begin! I loved the flavors of the dhaga kebab and kebab fry. The kebab fry was particularly tender and buttery, with a delicious minced texture. Eat them with the parathas for a real treat!

The chicken kebabs were also phenomenal. They had been nicely marinated in a beautiful spice mixture. I recommend dipping them into the chili chutney for some heat, but be warned—it’s very spicy!

My favorite dish there was the khiri. I couldn’t get enough of the smoky flavor and fatty, juicy texture. Together with the parathas and the chili chutney, it was heaven on my palate. I highly recommend this dish when you go to New Delhi Gola Kebab House. It’s one of my favorite dishes I ate in Karachi!

New Delhi Gola Kebab House Shahrah-e-Liaquat Burns Road Karachi, Pakistan

Delhi Rabri House

Another spot along Burns Road you cannot miss is Delhi Rabri House. This dessert spot is the perfect place to grab something sweet and creamy after a heavy and spicy meal elsewhere on the street.

I recommend the restaurant’s namesake, rabri, which is a pudding-like sweet made from condensed milk and millet flour, and then topped with nuts. If you have a sweet tooth, it’s the perfect dish for you, as it’s full of sugar! You can get it plain or topped with pistachios. I recommend the latter, as the pistachios add a nice crunch and a delicious nutty flavor!

Delhi Rabri House Sadiq Heights, 108/3 Alamgir Road Bihar Muslim Society BMCHS Sharafabad Karachi, Karachi City Sindh, Pakistan +92 333 3839507

Eat Pakistani Sindh Biryani at Biryani Wala

One of the most popular and most desirable neighborhoods in Karachi is the Clifton Neighborhood, which borders the ocean. There are a number of things to see there, but one of its best restaurants is Biryani Wala, which offers a number of varieties of the famous rice dish, biryani .

Biryani is a layered rice dish that’s made up of basmati rice, various proteins, vegetables, herbs, and masalas. It’s extremely popular throughout South Asia and can contain chicken, beef, fish, eggs, paneer, prawns, and more.

Furqan and I went with their chicken and beef varieties. As is customary throughout the region, we dug in with our hands. The chicken biryani was full of texture and flavor despite being relatively light on spices. It also contained potatoes. Adding a yogurt dish called raita made it creamier and even more delicious!

The beef biryani was my favorite, though. It had a heavier and heartier feel than the chicken, and the spices cooked into it really made the biryani come to life! I’ve eaten biryani all over the world, and I can say that this is one of the best I’ve ever had!

Biryani Wala Shop No 1 Tai Zainab Arcade Plot No 35/358 main Dhoraji Karachi, 74200, Pakistan +92 21 34851112

Explore the Clifton Neighborhood

The Clifton neighborhood is Karachi’s wealthiest neighborhood. This seaside neighborhood is home to Clifton Beach, as well as a bustling commercial area where you can find a number of fantastic street vendors. Exploring the neighborhood was one of my favorite things to do in Karachi, Pakistan!

These vendors sell everything from biryani to pani puri to a tangy, citrusy mosambe juice with black salt. But my favorite shop in the area is Sohny Sweet & Bakery, which sells dozens of different South Asian sweets. They include kalakand, barfi, halwa, and numerous cakes.

One thing you’ll learn in Pakistan and India is that they love their sweets, and boy do they love them to be extra sweet! If you’re like me and don’t have a massive sweet tooth, I recommend the walnut halwa, which was nutty and sweet without being overbearing. Their herbal baklava and rasgulla are other great options!

Sohny Sweet & Bakery Zone A – Block 7 Clifton, Karachi, Sindh 75600 Pakistan +92 21 35838140

Visit Clifton Beach

Clifton Beach is the most prominent beach and port city in Karachi and stretches from the city, all the way to the town of Ormara in Balochistan. Located along the Arabian Sea coast in the Clifton neighborhood, the beach also goes by the name Sea View.

The beach is famous for its picturesque black sand, as well as recreational activities like camel, horse, and buggy rides. Visitors also don’t have to go far for food, as the beach is home to street food vendors and a number of restaurants, including a McDonald’s.

When I visited the beach, I was amazed by the width of the beach at low tide and its striking black sands. I also met a man who offers 15-minute-long camel rides for 100 rupees each. It’s very touristy but is still one of the top things to do in Karachi, Pakistan!

Eat Nihari at Javed Nihari

There are a number of hearty, meaty, and mouthwatering dishes in Pakistan, but the one called nihari has to be my favorite. This unbelievable dish consists of beef, bone marrow, and beef brains in a thick, rich, and oily stew. To try some of the best nihari Karachi has to offer, head over to Javed Nihari.

From the street, you can see the cooks preparing this Pakistani comfort food in gigantic pots along with freshly baked naan. You eat the nihari with the naan, and it is one of the most incredible flavor explosions I’ve ever experienced.

The beef is unbelievably soft and tender, and falls apart in your mouth. The buttery bone marrow, flavorful broth and oil, garlic, and green chilies in the dish only add to its amazing flavor profile. Combining it with the crispy, fresh naan elevates the entire dish and adds even more pleasing textures!

My mouth would not stop watering as I devoured this mind-blowing stew. It’s one of my favorite breakfasts I ate during my time in Pakistan. And it’s also one of the top things you must do in Karachi, Pakistan!

Javed Nihari Dastagir Road Federal B Area Block 15 Gulberg Town, Karachi Sindh, Pakistan +92 333 3411029

Try Halwa Puri

Another popular breakfast item you must try when you visit Pakistan is halwa puri. To be fair, the dish is so common, it’ll probably be offered to you at some point without you even trying! The dish consists of a puri—a leavened, hollow flatbread that puffs up when it’s fried—along with a flavorful pickled dish called achar, chana (chickpeas), aloo (potatoes), and a sugary semolina dish called halwa.

I ate this dish multiple times over my twelve days in Pakistan, and one of my favorites was at Dilpasand Sweets, Bakers & Nimkoz in Karachi. Just watching the puris be prepared is a spectacle—roughly a dozen guys flatten the puri dough and toss them into a huge vat of bubbling oil, one after another!

The puris puff up and cook in just ten to fifteen seconds. They’re flaky and soft, as opposed to the crispier puris many people may be used to. The texture works well for this variation, which combines the sweet halwa, savory chana and aloo, and sour achar.

I suggest trying the puri with each dish separately and then start mixing and matching to see which combinations you enjoy the most. They were all extremely tasty, but the halwa was a step above the others. It’s one of my favorite sweets on Earth, and having some is one of the best things to do in Karachi, Pakistan.

Dilpasand Sweets, Bakers & Nimkoz Shahrah-e-Jahangir Road Federal B Area Block 7 Gulberg Town, Karachi, Karachi City Sindh, Pakistan +92 21 111376376

Explore the Biggest Fish Market in Karachi

Clifton Beach isn’t the only point of interest along Karachi’s Arabian Sea coast. There, you’ll also find Karachi Fish Natural harbour, the largest fish market in the city. Roughly 90% of the seafood and exports in Pakistan pass through this bustling, chaotic seaside marketplace.

You can go for a ride on a boat if you want, but the real action is on dry land. That’s where you’ll see the fish vendors, who sell freshly caught kingfish, red snapper, barracuda, grouper, prawns, crabs, tuna, and more.

Best of all, you can either buy the fish to take home with you, or you can take it to one of the karachi harbour area’s restaurants for them to cook for you!

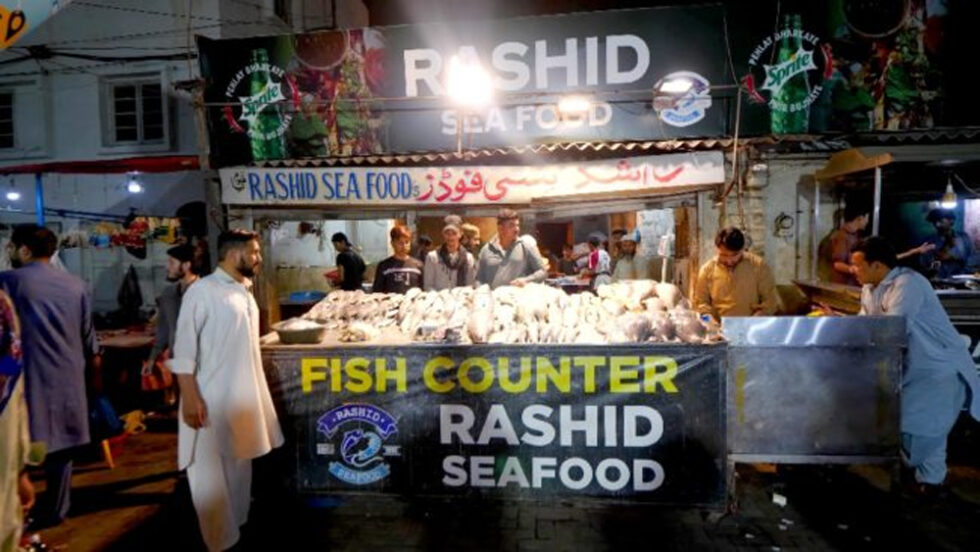

My guides Furqan and Shehroze and I bought a dhotar fish and kingfish and some prawns. We took them to Rashid Sea Food Fish Counter, where they made kebabs out of the kingfish, grilled the dhotar, and made two prawn dishes: grilled prawns and prawn karahi.

To say these were some of the best south asian seafood dishes I’ve ever eaten wouldn’t do them justice. The prawn karahi was spicy, oily, and succulent, with a kick of ginger, fresh vegetables, and hot peppers. It was perfect with the roti they gave us on the side.

I also adored the chunky, meaty kingfish kebabs with the pepper sauce. The dhotar, or gunter fish, had a deceptively spicy masala on it, which crept up on me after a few bites. Even though it was grilled, it was still perfectly juicy and tender.

Trust me, Karachi Fish Harbour is a must for any foodie. It’s one of the best things you can do in Karachi, Pakistan, and is one of the best places to have a true local experience!

Try Anda Parathas at Dhamthal Sweets, Bakers and Nimco

The world of Indian and Pakistani flatbread is nearly as diverse as South Asian cuisine itself. Most Westerners know about naan, but remain at least somewhat unfamiliar with roti, kulcha, chapati, appam, and one of my personal favorites, parathas. Parathas also come in many varieties, and one I fell in love with in Karachi is the anda paratha at Dhamthal Sweets, Bakers and Nimco.

Located just a few blocks from Dilpasand, this is another favorite haunt among locals. Anda parathas are essentially egg parathas—parathas baked with an egg and masala mixture brushed on top. The result is a crispy, flavorful, and golden brown flatbread, which they serve with fried eggs.

The anda-paratha-and-egg combination is remarkable. The different textures of the egg with the chewy, flaky paratha are absolutely mouthwatering. Enjoying it with the creamy, milky, spice-filled chai was the perfect way to cap off a breakfast tour. Easily one of the top things you must do in Karachi, Pakistan!

Dhamthal Sweets, Bakers and Nimco Gulshan-E-Ali ، No 2 Ayesha manzil Federal B Area Block 7 Karachi, 75950, Pakistan +92 21 36330775

Enjoy Haleem at Karachi Haleem

There are a number of places in Karachi where you can enjoy a local favorite called haleem. This thick, pasty stew typically contains meat, lentil, and grains, but has many variations throughout Southern Asia and the Middle East. The best spot in town to try some is Karachi Haleem, a local favorite on Burns Road.

At Karachi Haleem, you can get two different varieties—chicken and beef—so, naturally, I got both! They came with naan; a sweet rice dish called zarda; and several toppings including mint, chilies, and fried onions.

I recommend trying the haleem by itself first, so you can get a sense of its flavor and texture before adding the toppings and naan. The chicken haleem with the mint and chilies was unique, tasty, and satisfying, and the crispy fried onions added a nice acidity.

The beef haleem, which Furqan told me is his favorite, was even thicker and richer than the chicken. It was full of chilies and masalas that all worked in conjunction with one another. I honestly couldn’t get enough of it. As much as I enjoyed the chicken, I liked the beef even more!

The orange-hued zarda was very sweet but also had a nice herbal flavor. It was a nice dessert and palate cleanser. Best of all, this delicious meal for two only cost 440 rupees, or about $3 USD. It’s a cheap way to fill yourself up and among the top things to do in Karachi, Pakistan!

Karachi Haleem Pak Mansion, Burns Road Shahrah-e-Liaquat, Saddar Karachi, 75950, Pakistan +92 21 32633584

Explore Empress Market

As you may already know, Pakistan was once part of India before it broke off and became its own country. Before then, India was occupied and controlled by Great Britain from 1858 until 1947—the year India gained its independence and the year Pakistan was formed. Landmarks from this period, known as the British Raj, still remain throughout both countries. One of them is Empress Market in the Saddar Town locality.

This bustling, old-school bazaar resides in a large, beautiful British-style building and dates back to 1889. There, you’ll find vendors selling vegetables, fruits, spices, chilies, pickled achar, clothing, cooking oils, children’s toys, and much more.

The vendors are incredibly warm and friendly and may even let you sample some of their goods before you buy them. One of the most unique vendors there will extract oil from any seeds, nuts, or coconuts you bring him!

And while Empress Market is actually quite small compared to others I’ve visited, it’s a must. Visiting is a fascinating peek into local life and will give you a greater understanding of what Karachi is all about. It’s definitely one of my favorite things to do in Karachi, Pakistan!

Empress Market Saddar near Rainbow Center Karachi, Karachi City Sindh 74400, Pakistan

Eat Dahi Baray at Fresco

The number of incredible dishes available in Karachi is seemingly never-ending. I ate dozens of incredible dishes during my time in the city, but one I highly recommend is dahi baray. Also known as dahi bhalla or dahi vada, this dish consists of fried lentil balls served in sweet yogurt with crispy, fried dough on top.

To try this dish, head over to Fresco Sweets on Burns Road, where you’ll find cooks preparing this snack in a monstrous vat. The sweet and creamy yogurt, combined with the savory lentil balls, was exceptional. It’s cold and refreshing and is a great way to cool down after a heavy or spicy meal! One of my favorite things to do in Karachi, Pakistan, for sure!

Fresco Sweets Shahrah-e-Liaquat, near Aram Bagh Park Aram Bagh Burns Road Karachi, Karachi City Sindh, Pakistan +92 21 32218926

Try Fire Paan

When you travel to Southern Asia, you’ll come across a number of curious treats that may seem odd or surprising to you if you’re a Westerner. None are more curious than fire paan, a version of the street food called paan.

Regular paan consists of nuts, dried fruit, betel nut, and sometimes chocolate wrapped in a betel leaf. It serves as a palate cleanser, digestive, and breath freshener. Fire paan takes it a step further, as the vendor lights the mixture inside on fire and shoves the whole thing into your open mouth!

If you’re brave enough, head over to Panwaari to try this flaming treat. This version also contained ice and coconut, which made it very crunchy and cold. The flame gets extinguished the moment it enters your mouth, and within minutes of you chewing, you get an intense rush of energy! I’ve had it many times before and it never gets old. No list of the things to do in Karachi, Pakistan is complete without fire paan!

Panwaari 3rd St D.H.A Phase 6 Rahat Commercial Area Phase 6 Defence Housing Authority Karachi, Karachi City Sindh 75500, Pakistan +92 324 2336464

Enjoy Stuffed Naan at Cloud Naan

Nearly everyone in the Western world knows about naan, the soft, fluffy flatbread often eaten with butter chicken and chicken tikka masala. But how many of you know about stuffed naan? That’s what you’ll get if you head over to Cloud Naan, a fusion restaurant that has tons of inventive recipes on their menu.

I highly recommend their creamy tikka naan. This savory dish takes the naan you know and love, and stuffs it with a hearty, creamy mixture of chicken, mozzarella cheese, mushrooms, onions, and spicy cream cheese. It’s crispy on the outside, doughy on the inside, and full of flavor. If that wasn’t enough, it also comes with a rich garlic mayo dipping sauce!

But if you’re more in the mood for dessert, never fear. Their hazelnut chocolate oreo naan is like a decadent dessert pizza you’ll get in Rome! It’s topped with a Nutella-like chocolate and hazelnut spread, and the Oreo cookie pieces inside are beyond amazing. Whatever you order, go there with an appetite!

Cloud Naan Shop No 4 & 5, Plot 5-E Bokhari Commerical No 1, Street 1 D.H.A Phase 6 Phase 6 Defence Housing Authority Karachi, Karachi City Sindh 75500, Pakistan +92 21 35850174

Dine at Kolachi Restaurant

Although street food reigns supreme in Karachi, there are also some incredible fine dining options. One of them is Kolachi Restaurant, an enormous beachside restaurant with a massive, multi-level outdoor terrace.

You’ll find spectacle after spectacle inside, from the chicken chargha stacked vertically to the over 200 cooks in the kitchen. But my favorite thing about the restaurant is their outdoor seating, which overlooks the Arabian Sea.

Food-wise, it’s hard to go wrong. Whether you go with their creamy chicken makhani handi with roghni naan, the mutton chops, the Afghani boti, or something else, you will leave satisfied. The Afghani boti, in particular, was fatty, meaty, and one of the best lamb dishes I’ve ever eaten.

You can also try savory potatoes and vegetables, as well as grilled chilies. Pair the carrots, zucchini, and asparagus with the meat dishes for a meaty and fresh bite with some naan. Don’t forget to wash it all down with their pure, fresh apple juice. It’s the perfect way to cap off your meal!

Kolachi Restaurant Ocean Towers, 5 Th Khayaban-e-Iqbal Block 9 Clifton Karachi, Karachi City Sindh 75600, Pakistan +92 21 111 111 001

Stay at the Hotel Excelsior Karachi

I recommend staying in Karachi for at least three days. Of course, to make the most of your visit and ensure convenient access to the city’s attractions, you’ll need a place to lay your head at night. There’s no better spot in town than the Hotel Excelsior Karachi in Saddar Saddar Town, conveniently located not only for exploring the vibrant city but also offering easy accessibility to Jinnah International Airport for a seamless and stress-free travel experience.

The hotel is centrally located in the shopping district, so it’s within just a few minutes’ walk from malls, shopping streets, parks, museums, and movie theatres. You can also enjoy local, Chinese, and Continental favorites in their on-site restaurant.

The rooms inside are spacious and modern. They come decked out with a workstation, couch, TV, mini-fridge, and a lockbox. You’ll also have a large, comfortable bed and a clean, sleek bathroom. Staying there is one of the best things to do in Karachi, Pakistan!

Hotel Excelsior Karachi 4, Plot Number SB 21 Sarwar Shaheed Rd Saddar Saddar Town Karachi, Karachi City Sindh, Pakistan +92 21 35631751

Try Gappa Ghotala

If you get hungry while you’re out exploring the Clifton neighborhood, stop inside Mirchili. This popular chain has several locations in the city and sells a number of snack food favorites. My guide Furqan took me there specifically to try their gappa ghotala, which is a giant, crispy puri stuffed with lentils, chickpeas, yogurt, cilantro, three different chutneys, and crispy noodles called sev.

It’s similar to dahi puri, the creamier cousin of pani puri, which contains yogurt instead of pani. The gappa ghotala is sweet, bitter, and salty all at the same. The crunch of the sev and fried dough, and the velvety smoothness of the yogurt, are incredible.

If you still have some room in your belly after the gappa ghotala, you can also build your own dahi puris there as well. I highly recommend it! You get to fill them to your specifications. I personally loved the tamarind chutney with the yogurt. The savory coriander, masala, and chickpeas balanced it out perfectly. A must-try when you’re in Karachi!

Mirchili Plot 10, Zone C – Block 7 Zone C Block 7 Clifton Karachi, Karachi City Sindh 75600, Pakistan +92 300 8150831

BONUS: Have a Pani Puri Challenge

It’s not a trip to South Asia without some pani puri! Probably my favorite street food dish of all-time, pani puri consists of a small, hollow ball of fried, leavened dough called a puri. The ball is then punctured and filled with a mixture of potatoes, chickpeas, vegetables, chutneys, and a spice-rich water called pani.

Because pani puri is a bite-sized snack, it makes it perfect for eating challenges. I had attempted a few pani puri challenges—both against myself and against friends—before and had a great time with them. So my friend Alizeh from Manaky set up another for me and my guides Furqan and Shehroze in her backyard!

The pani puris themselves were incredible, from the aloo filling to the chickpeas to the crispy puri. The pani was also extremely flavorful and made it one of my favorite challenges so far! If you’d like to see who won our challenge, please check it out below.

Having a pani puri challenge is among the top things you can do in Karachi, Pakistan. It’s a fun way to immerse yourself in the food culture of the region with a delicious snack!

BONUS: Enjoy a Pakistani Haircut Experience

I’ve gotten my hair cut in many places around the world, from my hometown of Miami to the city I called home for over a year, Barcelona. But the haircuts in South Asia are on another level, as they usually also include full shaves, a washing, and relaxing back and head massages. You can’t beat them!

If you’re in need of some pampering in Karachi, head over to King’s Hair Dresser in the center of town near Empress Market. My barber there gave me the experience of a lifetime, starting with a head massage and giving me a clean head shave.

Then, he applied oil to my head and used his fingertips to massage deep into my skull. He then worked his way down to the tight and tense muscles in my neck, shoulders, and back. Before he finished up, he even massaged my arms, hands, and even my eyebrows.

The whole experience only cost me 300 rupees, or $1.94 USD, which is over $20 less than what I’d pay at home in Miami for just a haircut. It’s an amazing bargain, and you’ll leave with any tenseness in your head, body, and hands gone!

I had heard many positive things about Karachi long before I touched down there. Everything I’d heard from fellow travelers turned out to be true. The city is bustling and alive, and the locals are some of the friendliest people I’ve met while traveling. The hospitality was on another level and was only eclipsed by the quality of the food, which makes my mouth water every time I think about it. If you want to experience the best things to do in Karachi, book a trip to Pakistan today!

NOTE: If you need to check the visa requirements of a particular country, click here . To apply for a visa, find up-to-date visa information for different countries, and calculate the cost of a particular visa, click here !

Become a member for $5/month!

Connect with me, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Related Posts

Places in pakistan every traveler must experience, lahore, pakistan: a street food mecca, gujranwala, pakistan: the city of wrestlers.

Transforming Karachi, Pakistan into a livable and competitive megacity

Jon kher kaw, annie gapihan, peter ellis, jaafar sadok friaa.

Senior Urban Development Specialist

Senior Urban Specialist

Lead Urban Economist

Practice Manager

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

- nawaiwaqt group

- Roznama Nawaiwaqt

- Waqt News TV

- Sunday Magazine

- Family Magazine

- Nidai Millat

- Mahnama Phool

- Today's Paper

- Newspaper Picks

- Top Stories

- Lifestyle & Entertainment

- International

- Editor's Picks

- News In Pictures

- Write for Us

Karachi, the city of lights

Karachi is the largest city of Pakistan and the seventh major city in the world and is also known as the city of lights. It is now under the darkness of its spoiled infrastructure. Karachi the cosmopolitan and metropolitan city of Pakistan generates almost 70 percent of the federal revenue of Pakistan and it is the economic hub of the country having an estimated GDP of $114 billion in 2014.

Karachi also has geographical importance as besides the Arabian sea and the two major ports Bin Qasim and Port of Karachi. It has one of the busiest airports in the world Jinnah International Airport. The infrastructure of Karachi is getting worst every day. The broken roads and traffic jam is the most concerning issue in Karachi. The worst situation of traffic makes

it impossible for one to reach the destination on time and broken roads cause serious road accidents. Karachi needs serious attention and proper management to urbanize and build the proper infrastructure for the metropolis.

Biden quietly signs off on more bombs, warplanes for Israel

GHULAM MUSTAF,

Related News

New education policy, icj directive, digital freedom, the third tranche, digitalise to curb corruption, abettors of electricity theft will be given exemplary punishment, ..., abettors of electricity theft will be given exemplary punishment, warns pm, icj orders israel to take action to address famine in gaza, inflation-hit power consumers to pay rs125b extra as adjustments, supreme court allows military courts to announce reserved verdicts, pakistan aims to bring perpetrators of bisham attack to justice: fo, full court takes up judges’ claims of meddling by spy agencies, peshawar’s mohabat khan mosque: a cultural gem, khyber sports gala concludes, sacm kp directs to solve problems of miners, crush plants, govt, lender banks conclude pia’s commercial debt negotiations, tehsil chairman opposes tmo’s posting , perimeters of security, genetic engineering & food security, global rss fundraising.

The Orange Crow: Preparing to spread its ...

The orange crow: preparing to spread its vibrant wings, the solution, citizenship amendment act - muslims under ..., citizenship amendment act - muslims under threat in modi's ..., game of kings and the king of games: polo, textile exports earn $11.14 billion for ..., textile exports earn $11.14 billion for pakistan in eight ..., no bowing down, judicial accountability, teacher tribute, karachi’s air pollution, strength in gaza, endless tragedies, addressing nepotism, epaper - nawaiwaqt.

Newsletter Subscription

Advertisement.

NIPCO House, 4 - Shaharah e Fatima Jinnah,

Lahore, Pakistan

Tel: +92 42 36367580 | Fax : +92 42 36367005

- Advertise With Us

- Privacy Policy

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2024

‘He needs our votes’: In Karachi, Pakistan election tests old loyalties

The city has seen power shift – Imran Khan’s PTI won it over in 2018 after decades of dominance by the MQM. But Karachi’s challenges – cleanliness, sewage, water and cooking gas – remain the same.

![an essay about karachi Polling booth in Clifton, Karachi [Alia Chughtai/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/First-image-1707528829.jpg?resize=770%2C513&quality=80)

Karachi, Pakistan – These are the fourth general elections I’m covering in Pakistan over the past 16 years. In a city where colours, music and ethnicities change from neighbourhood to neighbourhood, every one of those previous elections has been confusing.

This one has been the same: chaotic and confusing. I started the day by voting at my neighbourhood polling station. It’s something I’ve always struggled with: Should journalists vote?

Keep reading

What shapes turkey’s municipal elections, senegal’s fishermen pin hopes on new president to help them fill their nets, senegal’s top court confirms bassirou diomaye faye’s election victory, how wisconsin advocates hope to use ‘uncommitted’ votes to pressure biden.

Then, as I reported from Pakistan’s largest city – home to 22 seats, more than the entire province of Balochistan – on Thursday, I realised that not only was Pakistan’s democracy on trial but so too were the city’s loyalties.

Former Prime Minister Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party had won 14 National Assembly seats in the 2018 election from Karachi, breaking voters away from the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), which has traditionally dominated the city’s political landscape. With the MQM split into multiple factions since 2016, its disenchanted voters found solace in Khan’s party, from the affluent southern areas of Karachi all the way to the city’s north.

I was standing outside my polling station in Clifton, barely 1km (0.6 miles) away from Bilawal House, which is the Karachi home of the Bhutto-Zardari family, which leads the Pakistan People’s Party. The PPP has historically been the most dominant political force in the province of Sindh, whose capital is Karachi.

Yet, on Thursday, most people streaming out to vote in this upscale part of Karachi were PTI supporters, many of them women who had stepped out at 8am to be among the first to cast their ballot.

N Tariq, a 50-year-old who did not want to share her full name, said she came first in the morning to ensure she caught the polling staff in a good mood and in the hope the voting process would be smooth and without long queues.

“I’m voting for the person who is in trouble right now. He needs our votes”, said Tariq. She laughed as she said this, referring to Khan, who received multiple sentences in a range of cases last week.

My next stop was one of the largest polling stations in Defence Phase 4, a cantonment housing area, run by Pakistan’s powerful military, which Khan’s supporters blame for derailing the party – its leaders are in jail, and candidates can’t even use the party symbol.

An upscale neighbourhood, the polling station was already getting busy – but it was missing the celebratory atmosphere of the 2018 election, when I had spent a few hours outside this venue.

By this time, my cellular and data connection had been cut and I could no longer contact anyone. As a native Karachite, losing cellular connectivity isn’t new to me but this was a day when law and order could be compromised and it was very unnerving.

![an essay about karachi Lyari, a stronghold of the Pakistan People's Party, was eerily quiet on Thursday, February 8, 2024 [Alia Chughtai/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Lyari1-1707528935.jpg?resize=770%2C433)

I headed towards Lyari, a PPP stronghold. As I drove through Lyari’s Cheel Chowk – the usually very noisy and congested area, home to decades-long gang wars, was eerily calm. It was so quiet that it made me uncomfortable.

The flags and banners were up but there was no music, no dancing, no blaring of Dilan Teer Bija – the PPP’s viral anthem.

As I began going through different polling stations, I came across many elderly women voters.

Rehmat, 75, and Kulsom, 60, came together to the polling station – where I wasn’t allowed in despite having accreditation. Kulsom said she was only voting for the PPP because it was the party of former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, who was assassinated in 2007.

![an essay about karachi Left: Kulsom, right, Rehmat, residents of Lyari [Alia Chughtai/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Rehmat-Kulsoom-1707529106.png?w=770&resize=770%2C433)

“Bilawal is her son and they have given us everything. Water, gas, and brought peace to this area, PPP has given us everything. What else do we need? I will always stand by PPP till my last breath,” said Kulsom. She was referring to Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari, the 36-year-old leader of the PPP.

Rehmat said her children don’t have jobs but the PPP is her choice too.

She voted for Bilawal’s grandfather – former Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto – in 1970, and then for Benazir, and now she is determined to vote for Bilawal.

“They work for us and they take care of us – how can we not love the Bhuttos?”, she said.

This wasn’t the sentiment shared by everyone in Lyari. A first-time voter, 18-year-old Mohammed Yazdan said promises are made before elections but never fulfilled.

![an essay about karachi First time voter, Mohammed Yazdan [Alia Chughtai/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Mohammed-Yazdan-1707529270.jpg?w=770&resize=770%2C429)

“I’m voting for Imran Khan, PTI, because those who do work are always pulled down by them. Look at what they’ve done to him. I will continue supporting him.”

I went into the heart of the city, in the old Golimar area, a working-class neighbourhood. There were small pockets of Tehreek-e-Labbaik, MQM and Jamaat-e-Islami supporters in the streets helping voters.

Tehreek-e-Labbaik , a far-right party formed in 2017, rallies support by focusing its politics around religion. Jamaat-e-Islami, also a religious right-wing party, is among Pakistan’s most organised political forces, with a charity wing, the Al Khidmat Foundation.

I found that voters were hesitant to admit they were going to be voting for PTI-affiliated candidates who have had to contest as independents.

One female voter who wished to remain anonymous said: “I’m sitting in the MQM tent to get my polling numbers sorted but my vote is always for the leader of the nation I can’t name. I wanted to come today to be a polling agent but we were told there would be security issues for those affiliated with PTI candidates.”

In the Pakistan Employees Cooperative Housing Society, an old neighbourhood known locally by its acronym PECHS, one of the larger polling stations is a college campus that has an unpaved dirt entrance and steps that go down into the main courtyard. After crossing it, voters had to climb up to the first and second floors to access polling booths, making the venue hard to reach for the elderly and people with limited ability to walk and climb stairs.

![an essay about karachi Dr Raza, a longtime voter at PECHS, whonhas repeatedly complained to the election commission about his booth not being accessible for elderly people or those with disabilities [Alia Chughtai/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Dr-Raza-1707529348.png?w=770&resize=770%2C513)

Dr Raza, 60 who lives in this constituency and only shared his last name, said that this college is always allotted as a polling station. He said he had written to the Election Commission of Pakistan many times asking them to reconsider the location due to its inaccessibility for those with physical limitations.

“Whether these are fair or not, it’s my duty to show up. But not everyone can. This polling station isn’t accessible for everyone,” he said.

In Gulshan-e-Iqbal, near the city’s biggest cricket venue, the National Stadium, voters at polling booths in a school campus complained that they had been there since 8am but election commission staff had arrived only at 11am and that, too, without ballot papers.

The long queue snaked around the building and was barely moving. As I shuffled through the crowd, at least eight men and women leapt out of their places in line to ask me to report what was happening there and how voters were effectively being dissuaded from casting their ballots.

![an essay about karachi The snaking queue around the Gulshan-e-Iqbal polling booth in Karachi on Thursday, February 8, 2024 [Alia Chughtai/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/NA238-crowded-line-2-1707529552.png?w=770&resize=770%2C433)

It was hard to push through the crowd and the presiding officer who sat in an empty room on the same floor told me there was nothing he could do and that yes, staff had arrived late.

I headed to an area packed with apartment complexes next to Gulistan-e-Johar. Though it was a public holiday, most people were getting on with daily work. Shops were open, there were daily wage workers and painters waiting to be contracted and shops were busy selling flowers and street food.

At a polling station within an apartment complex, the queue for women moved rapidly and Rehana Razi, 81, was one of those lined up to cast her vote.

“I’m older than Pakistan,” Razi said with a twinkle in her eye. “I’m here to vote and everything has been very systematic. It’s a secret who I’m here to vote for.”

![an essay about karachi Rehana Razi, senior citizen voter in Gulistan-e-Johar [Alia Chughtai/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Rehana-Razi-1707529681.png?w=770&resize=770%2C432)

Zohaib Khan, 36, was waiting outside the polling station with his toddler daughter, while his wife had lined up to vote. He had voted in Malir, more than 14.5km (9 miles) away but his wife was allotted the polling station in Gulistan-e-Johar.

“So we’ve come all the way here, because we have to vote for our PTI candidates. We want PTI to get more time to prove they can do real work for Karachi,” he said.

Karachi’s voters clearly have changed. Yet, the poorer neighbourhoods of the city remain as they were decades ago. Water, cooking gas, a cleaner city, proper sewage – these remain central concerns for the city of 17 million people.

Will those ever be addressed? And in a city as complex as this, can any one party really claim Karachi as its own?

![an essay about karachi Zohaib Khan, voter from Malir who had to travel to Gulistan-e-Johar [Alia Chughtai/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Zohaib-Khan-1707529743.jpg?w=770&resize=770%2C428)

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Daily Times

Your right to know Sunday, March 31, 2024

Perspectives

An Aerodrome — a forgotten Glory

June 29, 2020

Karachi has a fascinating aviation history to be proud of, with its airfields contributing to world records. Many eminent adventurous aviators, such as Amy Johnson, Amelia Earhart and Alan Cobham, from the early decades of flying, took to Karachi with historical journeys. The first plane to arrive at Karachi, on December 10, 1918, was the original Handley-Page biplane. Major MacLaren flew the second one from Britain, in the following month. The birthplace of the colonial era Royal Indian Air Force was RAF Drigh Road. Soon, Karachi aerodrome became the gateway to India and the largest in Asia. Here is how it grew with a glorious past …..

Drigh Road Airfield was founded in 1920, soon after Royal Air Force India Command was formed in 1918. The first aerodrome at Drigh Road was completed in 1924. Four years later, Karachi became the port of entry into India for Imperial Airways. In 1929, it became the first airport in South Asia where the Imperial Airways aircrafts landed from London. Thus, it was the first airport in the region for a commercial flight.

Imperial Airways Limited was formed on March 31, 1924, with the merger of British Marine Air Navigation Company Ltd, the Daimler Airway, Handley Page Transport Ltd and the Instone Air Line Ltd. It took the initial survey of flying between England and India. That journey to Karachi commenced on November 10, 1924, with Alan Cobham, accompanied by Air Vice-Marshal Sir Sefton Brancker and Arthur Elliot.

On December 27, 1926, Imperial Airways De Havilland Hercules left Croydon for a test flight to India. The flight reached Karachi on January 6, 1927. Sir Samuel Hoare (Secretary for Air), Lady Maud Hoare, and Air Vice-Marshal Sir Geoffrey Salmond landed at Karachi at 5.25 p.m. This was the first long-distance passenger flight ever carried out to a pre-arranged time table of hours and minutes. Capt Neville Stack and Barnard Leete made that first De Havilland Hercules light plane flight with passengers from London to Karachi. The journey took 11 days.

A separate department of Civil Aviation was created in 1927 with the appointment of Lt Col F C Shelmerdine as its first director. A nucleus of four controlled aerodromes at Karachi, Delhi, Allahabad and Calcutta was set up in 1931. A foundation of Air Traffic Control services was laid with the appointment of four Indian Aerodrome Officers trained in the UK. In those formative years, Commander HW Watt was appointed the commander of Karachi Airport in 1929.

Aviation circles were impressed by another remarkably short flight in 1927 when Flying Officer Keppen and Pilot Fryne, arrived at Karachi in three days from Amsterdam.

Regular London to Karachi service of Imperial Airways commenced on March 30, 1929, taking seven days. It became the airport of entry into India, connecting East and West. The oldest airline, still operating under its original name is KLM Royal Dutch Airlines (the flag carrier of the Netherlands), was founded on October 7, 1919. Its regular scheduled services between Amsterdam and Batavia (now called Jakarta) commenced in September 1929, operating via Karachi as en-route stop.

In October 1925, the Air Ministry issued orders and contract to build a huge hangar in Karachi, one of the three in the world. The construction of Kala Chapra commenced in 1926 and took two years to complete. Associated with it, a large mooring mast was also built. It was never used as the airship 101 was destroyed by fire in France on its maiden flight to Karachi in October 1930.

Karachi became the airport of entry into India, connecting East and West

The Royal Air Force commenced Karachi-Bombay airmail service on January 23, 1920. That was the first of the airmail in India. Mr P R Cadell, the commissioner in Sind, inaugurated the flight and among the passengers was Mr Lupton, Editor of the “Daily Gazette” Karachi, invited by the Governor of Bombay. The mail was carried in twelve cases. Those operations were terminated in six weeks in view of heavy losses. It only resumed years later in March 1929 when Imperial Airways commenced in Karachi for services to India.

To encourage local Indian pilots, Aga Khan arranged a competition for solo flight between India (Karachi) and England (London) in April 1930. The person to win the first prize was an 18-year-old student of DJ College Aspy Engineer, who was the son of a railway worker from Karachi. On return, he was cheered by a large crowd and garlanded by Mayor Jamshed Nusserwanji, while Cowasjee Variawa’s Own, the BVS School band, played tunes. Subsequently, he joined Royal Indian Air Force and was based at Drigh Road. Following partition, he rose to become Chief of the Indian Air Staff. One of the other competitors was JRD Tata from Bombay.

In 1932, Tata Airlines came to being as a division of Tata Sons Limited. On October 15, 1932, J R D Tata flew a single-engine De Havilland Puss Moth carrying air mail from Karachi’s Drigh Road Aerodrome to Bombay’s Juhu Airstrip via Ahmedabad.

In 1935, work commenced on the construction of a tower to carry a huge floodlight to make continuous day and night flying possible on the England-Australia route. Prior to that, there were not enough facilities for night landings.

The provision of additional new buildings and facilities for the emergency landing was announced in March 1936.

In December 1938, the Karachi Airport and its Terminal building (presently HQCAA Terminal-I) was reconstructed and It was officially opened for flight operations. During World War-II Karachi Airport (Terminal-I) was a major transhipment base for US Forces units. Personnel and equipment of the United States Army Air Forces littered the entire facility through during of the war. Air Technical Service Command had extensive facilities built where aircraft were received, assembled and tested prior to being flown to their combat units at forward airfields. Karachi Airport also functioned as major maintenance and supply depot for both air forces. The USAAF’s Air Transport Command also used Karachi Airfield as a staging point for supply runs to eastern India and China. The airport was handed back for civil aviation in 1945.

The Karachi Aero Club was established on July 28, 1928, and was the subcontinent’s first flying institution. Civil Air Service Training School commenced in 1944, with one of the sections being Aerodrome School for the training of officers both in administrative and flying control. All the new entrants to the service received a six-month course. After the war, the school trained specialist subordinate grades, including Signallers, Airfield Supervisors and Traffic Foremen.

Despite a decline in absolute airfares during the 1930s, the overseas middle class did not take to the air as much for recreational travel. The exorbitant cost was one factor. Another deterrent was the perception of risks including accidents, noise and the uncomfortable environment associated with flights. The advertised one-way fare between London and Karachi fell from £120 (equivalent to £7680 now) in 1929, to £85 in 1938.

The aerial geography bestowed Karachi with the largest and best-known airport in Asia. It became the major air function, particularly during the Second World War, when the Americans used it as a base and rebuilt the airport on a lavish scale. After the partition of India, Pakistan inherited an equipped and well-established aerodrome connecting East and West with major airlines landing at the port.

The writer is a consultant physician at Southend University Hospital, the UK

Submit a Comment

Home Lead Stories Latest News Editor’s Picks

Culture Life & Style Featured Videos

Editorials OP-EDS Commentary Advertise

Cartoons Letters Blogs Privacy Policy

Contact Company’s Financials Investor Information Terms & Conditions

Ilmlelo.com

Enjoy The Applications

Problems of Karachi essay in English

Is writing problems of Karachi essay giving you a headache? Don’t worry! Our Problems of Karachi Essay in English is here for you. Professionally written, this essay is perfect for students of grades 6 to 10 and college. Available in 150, 200, 250 and 300 words and in 10 lines, get yours today and impress your professor!

Karachi is the largest city in Pakistan and is home to a population of more than 17 million people. It is one of the most vibrant and rapidly-growing cities in the world. However, this population growth and urbanization have come with a number of problems, ranging from environmental issues to crime, to poor infrastructure. In this blog post, we will explore the various problems that Karachi faces and discuss potential solutions. We will examine the causes of these issues and how they can be addressed in order to create a better and more sustainable future for the city’s inhabitants.

Problems of Karachi essay in 150 words

Karachi is the biggest city in Pakistan, but it has some big problems. One big problem is bad roads, which make it hard to drive and can cause problems with water and electricity. The city also has bad sewage systems, which can make the sea and underground water dirty.

Safety is also a big worry, with a lot of crime and bad things happening to people. Plus, many people in Karachi don’t have jobs and are very poor. They also don’t have access to things like good healthcare and schools.

Many people are living in very crowded, bad places called slums. It is important that the leaders and other people in charge take action and try to fix these problems and make the city a better place to live.

Problems of Karachi city essay 250 words

Karachi is the biggest city in Pakistan, but it has a lot of problems. These problems are affecting the people who live there and also the city’s growth. One of the major challenges the city is facing is the lack of proper infrastructure. The roads and transportation in Karachi are not good, so it’s hard for people to move around and there’s a lot of traffic. It’s also common for people to have problems with getting water and electricity, which makes it hard for them to do things they need to do every day.

Another significant problem that the city is facing is the poor sewage system. The sewage water is not disposed of, resulting in pollution of the sea and groundwater. This not only harms the environment but also poses a threat to the health of the citizens.

Security is also a major concern in Karachi. The city has a high crime rate, and incidents of targeted killings, extortion, and kidnappings are common. The presence of various armed groups and political parties is also a major issue, as it causes instability and fear among the residents.

Karachi’s economy is also struggling, with high unemployment and poverty rates. Many residents are unable to access basic services such as healthcare and education. The city’s slums are also growing at an alarming rate, further exacerbating the problem of poverty and lack of proper housing.

In summary, Karachi is facing many challenges that are hindering its growth and affecting the daily lives of its residents. It’s vital that the government and other key stakeholders take immediate action to tackle these issues and enhance the city’s infrastructure, security, and economy, to improve the living conditions for the residents of Karachi. This will make the city a better place to live for the residents. Only through collective efforts can we see a better future for Karachi.

Karachi is a big city in Pakistan, but it has some problems that make life hard for the people who live there. One big problem is that the city doesn’t have good roads and public transportation. This makes it hard for people to get around and causes traffic. Also, the power and water often don’t work well, which makes it hard for people to do things they need to do.

Another big problem in Karachi is that the sewage system is not good. This causes pollution in the sea and in the water people to drink. This is bad for the environment and also makes people sick. Also, people in Karachi don’t get rid of their trash. This makes the streets dirty and clogged drains.

Safety is another big worry in Karachi. The city has a lot of crime and people get hurt or killed a lot. Bad things like being kidnapped, threatened for money and targeted killings happen often. There are also many groups with weapons and different political parties, which makes the city feel unsafe and scary for the people who live there.

The economy of Karachi is also struggling, with high unemployment and poverty rates. Many residents are unable to access basic services such as healthcare and education. The city’s slums are also growing at an alarming rate, further exacerbating the problem of poverty and lack of proper housing.

To sum up, Karachi has many problems that make it hard for the city to grow and for the people who live there. The government and other important people need to take action now to fix these problems. They need to make the city’s roads, public transportation, and housing better. They also need to make sure people have clean water and power. Furthermore, they need to make sure the city is clean and safe. Only by working together can we make Karachi a better place to live. The government should also focus on sustainable solutions for waste management, transportation, and housing. Also, they should take action against criminal groups to improve the security situation and promote peace in the city.

10 problems of Karachi

- Lack of proper infrastructure

- Inadequate transportation system

- Severe traffic congestion

- Frequent power outages

- Water shortages

- Inadequate sewage system leading to pollution

- Poor disposal of waste

- High crime rate

- Incidents of targeted killings, extortion, and kidnappings

- The presence of various armed groups and political parties causes instability.

Related Posts

Crm software products enable organizations to grow and manage businesses more effectively.

December 27, 2023 February 2, 2024

My aim in life essay in English for class 12,10 and others

December 28, 2022

Liaquat Ali Khan Essay In English

December 25, 2022

About Admin

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Recent Articles

- Journal Authors

- El Centro Main

- El Centro Reading List

- El Centro Links

- El Centro Fellows

- About El Centro

- Publish Your Work

- Editorial Policy

- Mission, Etc.

- Rights & Permissions

- Contact Info

- Support SWJ

- Join The Team

- Mad Science

- Front Page News

- Recent News Roundup

- News by Category

- Urban Operations Posts

- Recent Urban Operations Posts

- Urban Operations by Category

- Tribal Engagement

- For Advertisers

Blood on the street: violence, crime, and policing in Karachi

Vanda Felbab-Brown

Introduction

With 56 percent of the world’s population today living in urban spaces and 70 percent projected to do so by 2050,[1] major cities of the world play an ever-larger role in the 21 st century global system, power distribution, and public policies. Decisions of city governments significantly influence major transnational issues—from climate change, global financial and trade patterns, to poverty alleviation, disease mitigation and refugee flows. More than ever, a country’s governing capacity and the legitimacy of its government are shaped by how it suppresses crime and delivers order in urban areas, a major challenge for many countries.[2] Many cities in Africa and Latin America struggle to deliver effective public security, despite receiving significant international assistance. Much less policy and academic focus has been devoted to urban public order management in Asia, including specifically Karachi, even though the city is a major world megapolis, a significant global hub of legal and illegal trade, and source of transnational and local violence, including terrorism.

Based on fieldwork I conducted in Karachi in 2016 and supplemented by subsequent remote interviews, this article analyzes the sources of insecurity and violence in Karachi since the 1990s, focusing especially on the period between 2008 and 2023. Through interviews with security and police officials, military and paramilitary forces officers, politicians, civil society and business community representatives, members of criminal gangs, and security experts, the article assesses the effectiveness of anti-crime measures adopted in the city. Examining what has worked well and what policies have been deficient is a valuable source of lessons for other countries. It is also important because crime and terrorism are again rising in Karachi, the city’s residents are demanding better public safety.

For decades, and intensely so over the past twenty years, Karachi has struggled with violence, insecurity, and criminality. The city governments as well as Pakistan’s national authorities have at times either yielded or purposefully outsourced the delivery of order, safety, and other public goods to nonstate armed actors. The provision of these essential services by Karachi’s criminal and militant groups has thus regularly outcompeted their provision by the state, with the city’s nonstate armed actors hence acquiring significant political capital with Karachi’s residents.

From 2008 to 2015, the megapolis of between 20 million and 25 million people and Pakistan’s most important economic engine, experienced a particularly intense wave of violence. Homicides surpassed 2,000 a year, with war-like firearm exchanges on the streets. Extortions and kidnappings skyrocketed. Both the poor and the affluent were significantly affected. Many businesses shut down, and wealthy elites moved away. The local and federal government scrambled for a response.

For decades, police forces in Karachi have been under-resourced, incompetent, corrupt, politicized, and infiltrated by criminal groups. The justice system in the city—as well as nationally—suffers many deficiencies. Thus, to bring violence down, the local, state, and federal governments have repeatedly deployed official paramilitary forces to address the violence.

And indeed, in important ways, government policies did manage to suppress crucial aspects of violence, most importantly homicides. But other types of crime, terrorism, and militancy continue to be a challenge, and policing remains problematic and inadequate.[3] Moreover, the costs of the adopted law enforcement patterns have been severe in terms of civil liberties and human rights. The paramilitary forces, the Sindh Rangers, like the police in the city, turned out to be highly violent and perpetrated extensive and serious human rights violations.

In response to the criminal, political, ethnic, and terrorist violence, Karachi’s business community and civil society also mobilized. Going far beyond the civil society assistance to police forces found, for example, in Colombia’s Medellín, Brazil’s Sao Paulo, or Mexico’s Ciudad Juárez, Karachi’s business community established an essentially private police force with an extraordinary scope of activities. In contrast, the civil society activism emerged primarily against and as a result of the state repression of the Pashtun minority that suffered from law enforcement’s dragnets.

Yet a decade later, the paramilitary forces remain the principal policing force in the city. And their activities have gone far beyond their official mandate to combat violence. Supported by other law enforcement actors in the city, the Rangers have completely redesigned the political landscape of Karachi, selectively dismantling some political parties through the arrests of their members, while extra-legally empowering and privileging other parties. They have also increased their involvement in the city’s public management as well as its illegal economies, such as land grabbing and the criminalized delivery of services, including water.

Armed Security Karachi, Credit: Benny Lin , CC BY-NC 2.0

The Context

Between 2010 and 2015, violence in Karachi reached dramatic levels. In 2012, 2,174 were reported killed;[4] escalating to a record 2,700 in 2013. These deaths included targeted killings by political parties; warfare by and among jihadists; and murders by organized crime groups, often linked to politicians and political parties. Compounding the sense of insecurity was a dramatic terrorist attack on Karachi’s airport in July 2014.[5] By 2017, homicides, targeted killings, terrorist attacks, kidnappings, and extortions perpetrated by non-state actors declined by as much as 90 percent in the various categories. What explains the decline?

For decades, Karachi has been experiencing a dramatic, uncontrolled population growth, expanding from a mere 435,0000 residents in the early 1940s to some 25 million today.[6] The city’s historic and changing ethnic composition and demographics have shaped its economic development, urban planning, and governance—as well as its instability, violence, and organized crime.

One facet of Karachi is its economic power. With its large financial, textile, and manufacturing sectors, Karachi generates approximately 50 percent of Pakistan’s economic revenue (about $290 billion annually) and 90 percent of the province of Sindh.[7] It also handles 95 percent of Pakistan’s foreign trade and 30 percent of its manufacturing. It is the seat of Pakistan’s economic elite, with 90 percent of the headquarters of Pakistani banks, financial institutions, and multinational corporations located in Karachi.[8]

Another facet of Karachi is its privation: Some 70 percent of Karachi residents are poor, with half of the population living in squatter settlements known as katchi abadis .[9] These informal settlements mostly lack pumped water, sewage, and formal legal electricity hookups.[10]

Karachi’s decades-long poor exclusionary governance has eviscerated the city’s planning, organizational capacities, and provision of public goods. Instead, the delivery of public goods has, to a large extent, become privatized. Both in the public and private domains, or when delivered by what Karachi residents call mafias —a combination of organized crime groups and politicians—the delivery of essential services is politicized. The deep ethnic rivalries generating community competition over legal and illegal rents and bureaucratic appointments have resulted in and often purposefully generated and utilized criminal and street violence.

Drivers of violence

Waves of violence in Karachi, including the 2010-2013 iteration, have been driven by multiple factors: inter-communal hostility provoked and exploited by the campaigns of ethnically-oriented politicians and political parties; violence by the state, exacerbated by the weakness of the city’s police; organized crime and political competition over illicit economies and the provision of public services in the city; and the belligerence of jihadi militants and terrorists.

Political Parties

Much of Karachi’s violence results from the strategic use of violence by ethnically-based political parties to secure electoral votes, government appointments, and economic rents. Between 2007 and 2013, almost all of the city’s ethnic groups and their political parties engaged in violence against their political, ethnic, and business opponents, resulting in the deaths of over 7,000 people.[11]

The political-ethnic violence has often taken place between the Mohajirs and the Sindhis and between the Mohajirs and the Pashtuns and Baloch. The Mohajirs (literally refugees) are the Urdu-speaking migrants from India and their descendants. The 1947 partition of India that gave birth to Pakistan resulted in millions of Mohajirs arriving in the city. Almost overnight their influx reversed the ethnic balance in the city, shrinking the percentage of the previously dominant Sindhis from 60 to 14 percent (and less than 10 percent today) and increasing the presence of the Mohajirs from a mere 6 percent to well over 54 percent.[12] The Mohajirs stacked the city’s government institutions and bureaucratic appointments with their ethnic brethren, creating deep-seated resentment of the Sindhis and setting up a perpetual battle between the city’s government and the Sindhi-dominated provincial government. The Sindhis are still dominant in the rural areas of the Sindh Province of which Karachi is the capital.

Federal politics have shaped Karachi’s endless ethnic rivalries. The 1970s government of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, with his Pakistan People Party (PPP), favored the Sindhis, while the military regime of General Zia-ul-Haq (1977-1988) sought to weaken the PPP by supporting the creation of a Mohajir political party, the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM).[13] General Pervez Musharraf similarly sought to use the MQM to subjugate the PPP.[14] Indeed, Pakistan’s military has applied the same rule-and-divide strategy in Karachi that it uses throughout the country—at various times using the MQM to undermine the PPP’s attempt to weaken the military’s dominance of Pakistan’s politics and governance and at other times, such as in the 2010s and 2020s, turning on the MQM.

The political competition unleashed repeated violence in Karachi during the 1980s and 1990s as the Mohajirs sought to control governing structures and appointments – including, the lucrative Karachi Port Trust, Karachi Municipal Corporation and Karachi Development Authority—and the resulting patronage and votes. To obtain these rents and political capital, they often used street violence by armed wings.[15]

Since the 1980s, many Pakistani Pashtun migrants and Afghan refugees further altered Karachi’s ethnic balance and its power conflicts. By 2025, Pashtuns are projected to outnumber the Mohajirs,[16] yet they are the most politically and economically marginalized ethnic group in Karachi. While the Mohajir-Sindhi violence declined in the 1990s, ethnic violence escalated between the Mohajirs and Pashtuns and Balochs, particularly after the 2008 elections.[17]

In addition to having their own armed wings, the political parties established clientelistic relationships and alliances with organized crime groups to secure votes and engage in extortion and racketeering in the city, known in Karachi as the bhatta economy.

Illicit Economies, Criminal Groups, and Politics

As a crucial global port and gateway to Pakistan and Afghanistan, and a megacity of many unemployed, Karachi is also, not surprisingly, a significant hub of illicit economies and organized crime. The city’s crime economy overall is estimated at a $3 billion annually[18] and features drug trafficking,[19] arms smuggling, human smuggling, timber trafficking, extortion, gambling, and kidnapping as well as a variety of other predatory crimes.[20] These illicit economies are to various degrees dominated by organized crime or militant groups.

The under-delivery and privatization of basic services have provided further opportunities for criminalization and violence as well as extensive connections to politics. Informal and outright illicit economies and extensive theft have emerged in land access, electricity and water delivery,[21] as well as transportation. These illicit economies are run by organized crime groups connected to politicians and political parties – networks to which Karachi residents refer to as “mafias.”

Access to land is a prime example of such politically-linked criminalization. Both public and private land is frequently stolen and usurped by criminals, politicians, and/or state agents such as the Sindh Rangers and the military, whether directly by them or through proxies for their benefit. It is also taken over the city’s many squatters.[22] Land has thus become the city’s most prized and contested commodity, with federal, provincial, and local land-owning agencies, military cantonments, corporate entities and formal and informal developers fighting for land rights.[23]

Public transportation is largely defunct. Medical services are equally underprovided, delivered to many by charities or Islamist parties and the political proxies of Jihadist groups, such as Lashkar-e-Tayyaba (after state pressure renamed Jammat-ud-Dawa). In the political contestation surrounding the 2008 elections, the PPP and MQM used their political heft to get access for their clients to the city’s hospitals and clinics.[24] Meanwhile, the rich receive their medical treatment in Dubai, London, or the United States.

Many criminal groups in Karachi are ethnically based and have close, if complex, relations with the political party of their ethnicity. The Peoples Aman Committee (PAC) gang operating in the Lyari subdivision of Karachi is a prime example of these dynamics. For years, in addition to running its own criminal rackets such as drug trafficking and extortion, the PAC would also do some of the dirty work of its political patron, the PPP. At the same time, the PAC sought to cultivate the Karachi’s top police officials and corrupt Sindh Rangers as well as business and political elite even while extorting them.[25]

But like many other criminal gangs and militant groups,[26] the PAC sought to build its political capital with local populations by investing some of its proceeds from its criminal activities in public welfare schemes.[27] Following a major 2011 battle with the Karachi police during which not just the PAC, but the entire Lyari subdivision were de facto starved in a siege, the PAC also came to distribute water and food to Lyari’s residents. It also regulated street crime in the subdivision by advancing its own rackets. Under the PAC rule, carjacking, cellphone snatching, and robberies decreased compared to previous periods and other parts of the city.[28] The PAC supported and sponsored NGOs seeking to bring hospitals and schools to Lyari, one symbolically located in a gang’s former torture house.[29] In contrast, between 2001 and 2008 when MQM’s political power was high during the presidency of Gen. Pervez Musharraf, nothing had been built in Lyari. The discrimination was a blatant retaliation by the Mohajir MQM against the Sindhis.

But with its own political capital rising, the PAC started chaffing at the bid of its political patron, the PPP. It began cutting significantly into the PPP’s electoral base and challenging its orders.[30] While once essentially subservient to the politicians, the PAC crime gang began dictating the terms to the PPP, such as by selecting its own PPP candidates for the subdivision. [31]

Jihadist Militancy and Sectarian Conflict

Multiple highly dangerous jihadist terrorist groups operate in the city, compete over turf and illicit rackets, fundraise, organize violent operations, and take shelter from operations by the Pakistani military during occasional periods when the military decides to confront some of them as opposed to mostly coddling them.[32] The anti-India and Kashmir-focused Laskhar-e-Tayyaba (LeT)/ Jammat-ud-Dawa (that carried out the 2008 attack on Mumbai’s Taj Mahal hotel and other sites and killed over 160 people) and Jaish-e-Mohammad (that, along w LeT, carried out the 2001 attack on India’s parliament) and the anti-Shia Lashkar-e-Jhangvi have used the city as a crucial base for decades. They are extensively linked to the city’s many madrasas (Islamic schools). Sectarian violence between Pakistan’s predominant Sunni majority and Shia minority was unleashed in the 1980s by the Zia regime’s Islamization policies that patronized Deobandi extremist groups as a means of internal control and a counter to Shia mobilization after Iran’s 1979 Islamic revolution. Stoked by the rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran since, the sectarian contestation often explodes into violence in Karachi, where in 2012 and 2013, at least 100 sectarian killings took place each year.[33] After 9-11, Al Qaeda also used Karachi as a key operating area and killed the U.S. Wall Street Journal ’s correspondent Daniel Pearl there.

Among the more recent arrivals, about a decade and half ago, has been the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), a terrorist group displaced to Karachi as a result of Pakistan’s military operations in the province of Khyber Pakthunkhwa and previously autonomous tribal areas (now incorporated into KPK). As the presence of TTP in Karachi grew to some 8,000 members in 2013, so did violence.[34] Although also predominantly Pahstun, the TTP intensely focused violence on the anti-militant Pashtun party Awami National Party (ANP). By the end of 2013, the TTP’s violent actions had forced the ANP to close down 70 percent of its offices in the city.[35] In fact, in the runup to the 2013 elections, the TTP ratcheted up violence against all political parties that opposed it, attempting to prevent them from campaigning.[36]