History Cooperative

World History and the History of Women, Gender, and Sexuality

In his recent—and excellent—study of the development of world history, Navigating World History, Patrick Manning remarks on the lack of intersection between social history and world history as the two fields have developed over the last several decades.[1]

World history and the history of women, gender, and sexuality have also seen relatively few interchanges, which several women’s historians, including Bonnie Smith, Judith Zinsser, Margaret Strobel, and I, have noted in various venues.[2]

Manning does as well in Navigating World History, writing “World history, especially as a history of great states and long-distance trade, included little recognition of gender and little space for women …it remains striking that studies of women and gender roles in world history have developed so slowly and that their development has been restricted to a small number of themes.”[3]

Why might this be? In his comments about this issue, Manning suggests that the reason for this is the “well established presumption that women’s lives are acted out in the private sphere of the family rather than the public sphere of the economy and politics” and notes that one reason scholarship on colonized societies seems to be leading the way in a gendered approach to world history is that “in colonial situations, the state interferes in the working of families and social values generally.”[4]

This may indeed be a well-established presumption among world historians, whom Manning knows very well. Most historians of women, gender, and sexuality today begin with the exact opposite presumptions, however: that women’s history is not the same as the history of the family, that the state has always interfered in the working of families and social values (and continues to do so), that the boundaries between public and private are contested, variable, and shifting, and perhaps don’t really exist at all.

Manning’s statements and his thorough discussion of the field of world history inadvertently highlight what I would see as the reason for this situation: women’s/gender history and world history have both developed at the same time as, in part, revisionist interpretations arguing that the standard story needs to be made broader and much more complex; both have been viewed by those hostile or uninterested as “having an agenda.” Both have, as Judith Zinsser has commented, “had to write with the stories of men’s lives in the United States and Europe paramount in their readers’ memories.”[5]

Both have concentrated on their own lines of revision and, because there is only so much time in a day and only so many battles one can fight, have not paid enough attention to what is going on in the other. Thus neither has a very good idea of what the other has been doing over the last several decades, and each conceptualizes the other in terms that the other would find old-fashioned: world historians see women’s history as a matter of families and private life; women’s/gender historians see world history as area studies and world-systems theory.

The primary revisionary paths in world history and women’s and gender history have also been in opposite directions. In Patrick Manning’s words, “world history is the story of connections within the global human community. The world historian’s work is to portray the crossing of boundaries and the linking of systems in the human past.”[6] As David Northrup commented recently, world history has been the story of the “great convergence.”[7]

In contrast, after an initial flurry of “sisterhood is global,” women’s and gender history over the last decades have spent much more time on divergence, making categories of difference ever more complex. There was, of course, the Holy Trinity of race, class, and gender, but there was also sexual orientation, age, marital status, geographic location, and able-bodiedness. Women’s historians emphasized that every key aspect of gender relations—the relationship between the family and the state, the relationship between gender and sexuality, and so on—is historically, culturally, and class specific. Everything that looks like a dichotomy—public/private, male/ female,gay/straight, black/white—really isn’t, but should be “queered,” that is, complicated so as to problematize the artificial and constructed nature of the oppositional pair.

These differing revisionary paths have meant that most historians who identify themselves as scholars of women, gender, and sexuality thus do not think of themselves as world historians, and both leading and younger scholars who do identify as world historians do not regularly focus on women or sexuality, or include gender as a primary category of analysis. This lack of intersection is reflected in the fact that at the 2003 World History Association conference, there was only one full panel and two individual papers (out of forty panels) that focused on women, gender, or family; at the 2004 conference there were two panels and two individual papers; and at the 2005 conference two papers and no panels. At none of these conferences was there anything on sexuality. Of the eighty articles in the last five years of the Journal of World History, only three specifically examine women or gender, and none focuses on sexuality. Of the more than thirty books in the Ashgate series “An Expanding World: The European Impact on World History 1450–1800,” not one focuses on women or gender, though there is one on families. This could be because gender is so well integrated as a category of analysis that separate articles or books aren’t necessary (in other words, that the “add women and stir” stage has been vaulted over), but this is not the case.

From the other side, well over half of the paper proposals to the Berkshire Women’s History Conference in the last several years it was held (1996, 1999, 2002, 2005) focused on U.S. history, despite the fact that the 1996 Berks theme was “Complicating Categories,” the 1999 theme was “Breaking Boundaries,” and the 2002 theme was “Local Knowledge and Global Knowledge.” The 2005 Berks theme was even more pointedly global: “Sin Fronteras: Women’s Histories, Global Conversations,” but about half the proposals were still in U.S. history. Yes, the “globalization” of U.S. history has affected women’s history, and many of the papers that focused on U.S. topics considered issues such as migration, American neo-imperialism, various diasporas, ethnic identity, and transnationalism. They were still about the United States, however. Of the eighty-eight articles published in the last five years of the Journal of Women’s History, only eight are what I would term “world history” topics, though two-thirds do deal with topics outside the United States. Of the books submitted to the American Historical Association by publishers for consideration for the Joan Kelly Prize in women’s history for the last two years (about ninety books a year), about 40 percent focus on U.S. history, another 40 percent focus on Europe, and about 20 percent are about the rest of the world. Only a handful take on topics that have been at the center of world history, such as trade, cultural diffusion, or encounters between population groups.

Though some people may interpret all these numbers as intentional exclusion on the part of journal editors and conference organizers, I edit a journal and have run enough conferences to know that it more likely reflects a lack of manuscripts or papers submitted. Because conference paper submissions often come from younger scholars, including those still in graduate school, however, the prospects for the immediate future aren’t great—too much world history does not involve gender, and too much women’s and gender history focuses on the United States.

The lack of interchange between world history and social history, and between world history and women’s history, might seem to be directly related, as most stories of women’s history as a field link it with the feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s and also with the rise of the New Social History in the 1960s. That latter connection is one that has not always been comfortable, however. In a recent article in the Journal of Women’s History, Joan Scott comments that “there was nothing inevitable about women’s history arising from social history. Rather, feminists argued, within the terms and against the grain of behaviorism and new left Marxism, that women were a necessary consideration for social historians. If they were omitted, key insights were lost about the ways class was constructed. While male historians celebrated the democratic impulses of the nascent working class, historians of women pointed to its gender hierarchies [and] also offered a critique of the ways in which labor historians reproduced the machismo of trade unionists. This did not always sit well, indeed feminists found themselves (and still find themselves) ghettoized at meetings of labor historians.”[8]

I remember this from a conference years ago sponsored by History Workshop Journal, which had only just changed its subtitle to “a journal of socialist and feminist historians,” but in which the two sides of that linking were still quite separate and definitely not equal.[9] That has changed; the editorial board at History Workshop Journal is now exactly gender balanced, and that of Radical History Review has slightly more women than men. (What’s going on in labor history, at least in terms of journals, has been complicated by the dispute between the editors of Labor History and its publisher, Taylor and Francis, which led to a founding of a new journal in 2004, Labor: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas, edited by Leon Fink. The editorial board of the new journal is distinctly more gender-balanced than that of Labor History, however, and the phrase “men and women” does appear in its mission statement.)

Despite Scott’s sliding from one to the other, labor history and leftie history are not the same as social history, of course, though both are often seen, like women’s history, as growing out of the New Social History of the 1960s. In the last several decades, however, women’s historians have stressed that what they do is not always social history, to avoid the very presumption about the limitation of women’s lives to the private sphere of the family that Manning talks about. They assert that there is really no historical change that cannot be analyzed from a feminist perspective, and no historical change—or continuity—that did not affect the lives of women in some way. (They also assert that these two things are not the same, that is, that feminist analysis does not have to be about women.) They argue most forcefully in historical fields in which the fit seems less obvious and in which the resistance to women’s history has been greatest—intellectual history, political history, military history. This is in part because who doesn’t love a good fight? But also, I would argue, because it has been more satisfying and comfortable to take on people in such fields than those who are closer politically and intellectually. Generally when women’s historians set what they do up against “traditional” history, that “traditional” history, despite Scott’s comment, is more often the story of states and generals than that of labor unions and socialist parties.

The split between “women’s history” and “gender history” also became mixed up in this distinguishing of women’s history from social history. Afsaneh Najmabadi has recently commented that “social history was most welcoming of the former [that is, women’s history], but anxious about the latter, especially as gender became a troubled category in itself.”[10] The development of gender history occurred at the same time as the “linguistic turn” and “the new cultural history,” and in some people’s minds—both in and out of the fields—the two are related. Many women’s historians responded harshly to the linguistic turn. Wasn’t it ironic, they noted, that just as women were learning they had a history, and asserting they were part of history, “history” became just a text and “women” just a historical construct? In her wonderfully titled 1998 article in Church History, “The Lady Vanishes,” Liz Clark wrote, “Why were we told to abandon subjectivity just at the historical moment that women had begun to claim it?”[11]

In an article in the most recent issue of the Journal of Women’s History that surveys books and dissertations in U.S. women’s history 1998–2000, Gerda Lerner documents and criticizes the trend toward studying representation, culture, and discourse. She comments that “the subject of class is being massively ignored, and interest in the economic realities of women’s lives in the past seems generally to be fading.”[12] She also finds, and criticizes, a “low order of interest aroused by topics such as suffrage, women’s organizations, women’s struggles for equality under the law, and political subjects in general,” and calls for more research that “focuses on the activities, thoughts, and experiences of women,” and that also constructs theory that develops a “new paradigm for an egalitarian history of men and women as agents of history.”[13] In recent speeches, Lerner’s critique of the focus on representation has been even sharper.

The linguistic turn provoked strong reactions and led to splits within many other historical fields as well. Most recently, however, cultural history, or rather the more broadly defined “cultural studies,” has portrayed itself not as a divisive force but as a healer of all wounds, a sort of humanistic unified field theory. “Cultural studies” understands itself—at least in self-descriptions on Web sites and in essay collections—as including everything I’ve been talking about: social history, women’s history, world history, gender history. The word “social” appears in most descriptions of cultural studies programs—social theory, social construction of values, social relations—as do words that suggest (though they rarely use the word) history—contemporary and past cultures, change and continuity, present and past.

Cultural studies does not understand itself as growing out of or even linked to social history, however, and even less to anthropology. Both Colin Sparks (in the reader What Is Cultural Studies?) and Simon During (in The Cultural Studies Reader) locate the origins of cultural studies in two books of literary theory, The Uses of Literacy by Richard Hoggart and Culture and Society by Raymond Williams.[14] Sparks does note that these two represented a “shift from the aesthetic to the anthropological definition of culture,” but it was only when literary criticism shifted that a new field was born. The fact that anthropologists had had an “anthropological definition of culture” for quite some time did not seem to matter. Nor did it seem to occur to the folks at Towson State’s cultural studies program that someone, somewhere might have already been studying “aspects of everyday life in both the present and the past,” a phrase they include in their description of the program’s objects of study.[15] They do world history and women’s history, too, of course, studying “gender, sexuality, class, race and ethnicity, globalization, and national identity.” So apparently we can just stop worrying about finding connections and promoting interchange, because cultural studies has done it for us.

There are some problems with this, however, as you can imagine. Despite the sweeping (and often breathless) self-definitions, programs and readers in cultural studies tend toward the literary and the contemporary, as might be expected from programs that often grew out of the theory wing of English departments. Simon During’s introduction to The Cultural Studies Reader notes first that the field’s focus is culture, but then adds, “more particularly, the study of contemporary culture.”[16] A few historians are included in the general readers, and some course descriptions also include the same language about “contemporary and historical” that the program definitions do. But it is, not surprisingly, primarily in cultural studies materials produced by historians that there is much concern with the deep past, that is, the past before the invention of television. These materials are often specifically framed as “cultural history,” however, a reification that has both benefits and detriments; it highlights the historical nature of some studies of culture, but also implies that there is some history that is not cultural, while the definitions of cultural studies imply no such limits.

I don’t think, therefore—to use a highly gendered metaphor—that cultural studies is quite the white knight and unifier that it represents itself as being. That sentiment is shared by some of the historians and anthropologists who have been most associated with the field, yet who continue to stress its problematic nature. Lynn Hunt, for example, whose The New Cultural History was required reading in the 1990s, has more recently published Beyond the Cultural Turn.[17] The anthropologist Sherry Ortner goes even further, putting culture in quotation marks in her edited volume The Fate of “Culture.”[18] Things in quotation marks —the “Enlightenment,” Athenian or Jacksonian “democracy”—are clearly things that raise questions, not answer them or make them moot.

So if cultural studies can’t provide a unified-field theory, and most world history does not involve gender, and most women’s and gender history focuses on the United States, is there much promise of interchange? I think there is, and I would like to end with several examples of work in which I see this promise becoming reality, work that brings together world history and the history of women, gender, and sexuality. Most of these studies do not explicitly present themselves as world history, but they use concepts or investigate topics that have been extremely influential in world history: encounters, borderlands, frontiers, migration, transnational, national and regional identities, and heterogeneity.

Manning is absolutely right that studies of colonialism and postcolonialism seem to be leading the way—so much so, in fact, that we are already into revision and self-criticism in work on gender and colonialism. The Winter 2003 issue of the Journal of Women’s History was a special issue: “Revising the Experiences of Colonized Women: Beyond Binaries,” with articles on Australia, Indonesia, India, Igboland, Mozambique, and the U.S. Midwest.[19]

That issue also had a separate section on historians, sources, and historiography of women and gender in modern India that emphasized “dissolving” and “rethinking” various boundaries. It is not surprising that this section focused particularly on India, for among colonized areas, South Asia has seen the most research. Feminist historians of India, including Tanika Sarkar, Kamala Visweswaran, and Manu Goswami, have developed insightful analyses of the construction of gender and national identity in India during the colonial era and the continued, often horrific and violent, repercussions of these constructions today.[20]

Sarkar in particular highlights the role of female figures—the expected devoted mother, sometimes conceptualized as Mother India, but also the loving and sacrificing wife—in nationalist iconography. Though the theoretical framework in this scholarship is postcolonial, Sarkar and Visweswaran also take subaltern studies and much of postcolonial scholarship to task for viewing actual women largely as a type of “eternal feminine,” victimized and abject, an essentialism that denies women agency and turns gender into a historical constant, not a dynamic category.

The large number of works on India has led some scholars of colonialism to argue that Indian history has become the master subaltern narrative, and that Indian women have somehow become iconic of “gendered postcolonialism.” I was not surprised to find the cover image on a recent issue of Radical History Review, an issue titled “Two, Three, Many Worlds: Radical Methodologies for Global History,” a photograph of two Indian women, the environmentalists Rashida Bee and Champa Devi Shukla.[21]

This choice of image makes sense given the lead article in the issue, which focuses on the aftermath of Bhopal, and given the powerful role of Indian women in global environmental movements. (Along with these two women, Vandana Shiva has become especially prominent on issues of biodiversity and the globalization of resources.) But it does reinforce the iconography.

Because it would be impossible to do justice to the many studies of South Asia, I would like to mention some excellent recent work on other parts of the world.[22] Gender and nationalism has clearly been a key area of scholarship, with edited collections and monographs.[23]

There are articles on gender and nationalism in many of the new collections on nationalism, and a special issue in 2000 of the new journal Nations and Nationalism titled “The Awkward Relationship: Gender and Nationalism.” Feminist Review, Gender and History, and Women’s Studies International Forum have all had special issues on nationalism, and there are chapters on nationalism in the new collections on global gender history, such as Bonnie Smith’s Women’s History in Global Perspective, and in Teresa Meade and my Companion to Gender History. Thus the interpenetration is going both ways, as it must: gender is making it into considerations of nationalism, and nationalism into considerations of gender.

The construction of nationalism and the imagined nature of national communities are important themes in this work, but women are viewed as important agents in that construction, and actual nations do result. Gender is also beginning to show up as a category of analysis in transnationalism, such as the new collection by Wendy Hesford and Wendy Kozol, Just Advocacy? Women’s Human Rights, Transnational Feminisms, and the Politics of Representation, and the new journal Meridians: Feminism, Race Transnationalism.[24]

The construction of gendered ethnoracial categories has been another strong area of research, including Jane Merritt’s At the Crossroads: Indians & Empires on a Mid-Atlantic Frontier, 1700–1763 and Nancy Appelbaum’s Muddied Waters: Race, Region, and Local History inColombia, 1846–1948.[25] This is also the focus of Susan Kellogg’s “Depicting Mestizaje: Gendered Images of Race in Colonial Mexican Texts” and Martha Hodes’s “The Mercurial Nature and Abiding Power of Race: A Transnational Family Story.”[26] Some of this work, and much of the scholarship on gender in colonial South Asia, is about discourse and representation—in this Gerda Lerner would not be pleased—but much of it is explicitly political, part of the burgeoning feminist work on gender and the state.

Studies that are clearly in what we usually think of as the realm of social history are fewer, but here I would highlight two articles from last year in the Journal of World History, both about North American women in Japan : Manako Ogawa’s on missionary women’s establishment of a settlement house in Tokyo right after World War I and Karen Garner’s on the World YWCA visitation to occupied Japan right after World War II.[27]

Jennifer L. Morgan’s Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery explores the way that work and reproduction both shaped the economic value, gendered identity, and day-to-day lives of African women in West Africa and the New World.[28] The ways gendered patterns of consumption shaped trade and production worldwide over very long periods emerge in Michelle Maskiell’s study of Kashmiri shawls and Maxine Berg’s analysis of European response to Asian luxury goods.[29] Several of the thematic essays in Teresa Meade and my Companion to Gender History address social history topics: labor, the family, popular religion, schooling.[30] M. J. Maynes and Anne Waltner provide suggestions of how to do comparative or global social history in several articles focusing on marriage.[31]

This brief survey is certainly not exhaustive, but even a more complete list would not be as long as it should be, and would also be skewed toward certain issues: race, political rights, slavery, representations of the “Other.” There is far less social and economic history in gendered global history than one would expect. These trends are a reflection of what has happened in history as a whole, of course; one can hardly expect a subfield that has been seen as a “fad” now for thirty years to avoid whatever is the newest trend.

But they are also a reflection, as I argued earlier, of historians of women and gender being more eager to take on what seem to be less likely fits—the Renaissance; the French, American, Haitian, and Scientific Revolutions; the Meiji Restoration—to make sure that the stories of formalized power relationships and of intellectual change do not remain stories of ungendered men. As Linda Kerber, Alice Kessler-Harris, and Kathryn Kish Sklar wrote in the introduction to U.S. History as Women’s History, the most significant task has been “to discover how gender serves to legitimize particular constructions of power and knowledge, to meld these into accepted practice and state policy.”[32]

That point still needs to be made, for gender remains what Randi Warne has called an “expertise of the margins” in global political and intellectual history, where there are huge areas that have not been analyzed at all in terms of either women or gender, to say nothing of sexuality.[33] (There are now nearly thirty books on the history of English masculinity, so won’t someone please, please do the manly Mongols?[34]) But I think that world history might provide historians of women, gender, and sexuality with an opportunity to also work on social history topics without seeming too fuddy-duddy.

Lerner’s survey of recent work in U.S. women’s history finds that books, articles, and dissertations on African American women tend to focus much more on women’s organizations and on class than does the rest of U.S. women’s history, and to be “more interested in the realities of lives of the past than they are in interpretation and representation.”[35] The first of these areas—women’s organizations—has seen many studies from a world-history perspective, as so many of those organizations had a global reach and mission. Gendered class analysis from a global perspective, however, is another matter, and one where the insights gained through investigating the intersection of gender, sexuality, and race, and the role of gender in constructions of the nation and national identity, can be fruitfully applied.

We may now be at a point where the opposite paths of world history and women’s and gender history—one toward convergence, and the other toward divergence—could be coming together. In his discussion of the emphasis on convergence in world history, David Northrup commented that this may have been an overly “cherished framework,” and that divergence now needs more attention from world historians.[36] On the other side, historians of women and gender are clearly more willing to pay particular attention to instances of encounter and convergence, as is clear from the exploding amount of scholarship on gender and empire. Increased interchange between world history and the history of women, gender, and sexuality can help develop what we might choose to call the “new, new social history.”

This would not be the breathlessly totalizing unified field theory that cultural studies presents itself as (what the physicist Michio Katu has called “an equation an inch long that would allow us to read the mind of God”), but one that builds on the strengths of many subfields: the tradition of collaborative and collective work in radical and feminist history; the emphasis on interaction, exchange, and connection from world history; the focus on the agency of everyday people from the “old” new social history; the attention to hegemony, hierarchy, and essentialism from queer theory, critical race theory, and postcolonial theory; the stress on difference and on intersections between multiple categories of analysis from women’s history.

These are all lines of interchange that offer much, much promise. “Gender” and “global” are two lenses that have been used, largely separately, to re-vision history in the last several decades. Putting them together allows us to create both telescopes and microscopes, to see further and find new things we’ve never seen before, and to see very familiar things in completely new ways.

I presented this paper in January 2005 and revised it over the following year. As it was going into press, the 2006 World History Association conference was held at California State University at Long Beach. At that conference, there were three entire sessions devoted to issues of gender and/or sexuality, and several additional individual papers; one of the sessions was specifically organized to look at “confluences” of gender and world history.

Papers included analyses of brand-new topics and new approaches to familiar topics, some from areas of concern to social historians, such as the family and work, and others from cultural history, such as gendered constructions of imperial encounters. It is clear that the creative interchange between gender history and world history I call for here has already begun, and to that, I say huzzah! Fabuloso! Wunderbar! Ihmeellinen! Odorokubeki! Csodás! Ajabu!

1 Patrick Manning, Navigating World History: Historians Create a Global Past (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003).

2 Judith P. Zinsser, “And Now for Something Completely Different: Gendering the World History Survey,” in The New World History: A Teacher’s Companion, ed. Ross E. Dunn (Boston: Bedford, 1999), pp. 476–478, and “Women’s History, World History, and the Construction of New Narratives,” Journal of Women’s History 12, no. 3 (2000): 196–206; Bonnie Smith, “Introduction,” in Women’s History in Global Perspective Vol. 1, ed. Bonnie Smith (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004), pp. 1–8; Merry Wiesner-Hanks, “Women’s History and World History Courses,” Radical History Review 91 (Winter 2005): 133–150; and Margaret Strobel and Marjorie Bingham, “The Theory and Practice of Women’s History and Gender History in Global Perspective,” in Smith, Women’s History, pp. 9–47.

3 Manning, Navigating World History, pp. 208, 210.

4 Ibid., p. 210.

5 Zinsser, “Women’s History,” p. 197.

6 Manning, Navigating World History, p. 3.

7 David Northrup, “Globalization and the Great Convergence: Rethinking World History in the Long Term,” Journal of World History 16 (2005): 249–268.

8 Joan Scott, “Feminism’s History,” Journal of Women’s History 16, no. 2 (2004): 10–29. With responses by Afsaneh Najmabadi, “From Supplementarity to Parasitism,” and Evelynn M. Hammonds, “Power and Politics in Feminism’s History—and Future.”

9 That conference, held in 1983, was titled “Religion and Society” and organized by Raphael Samuel, James Obelkevich, and Lyndal Roper, who subsequently edited a conference volume, Disciplines of Faith: Religion, Patriarchy and Politics (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1987). The conference ended with a session on “Women and Christianity Today,” which the conference organizers note in the book introduction “released a great deal of anger.” This is a very understated description of a scene I will never forget, with people shouting and standing on chairs, those in the back of the room calling for the heads of those who thought that the topic of the session could be discussed in a dispassionate way, and those in the front just as fervently arguing that it had to be.

10 Najmabadi, “From Supplementarity,” p. 32.

11 Elizabeth A. Clark, “The Lady Vanishes: Dilemmas of a Feminist Historian after the ‘Linguistic Turn,'” Church History 67 (1998): 3. Clark also has a book-length consideration of the linguistic turn, History, Theory, Text: Historians and the Linguistic Turn (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2004).

12 Gerda Lerner, “U.S. Women’s History: Past, Present and Future,” Journal of Women’s History 16, no. 4 (2004): 10–27, with responses by Kimberly Springer, Kathi Kern, Jennifer M. Spear, and Leslie Alexander. The quotation is on p. 21.

13 Ibid., pp. 22, 24–25.

14 Colin Sparks, “The Evolution of Cultural Studies,” in What Is Cultural Studies? A Reader, ed. John Storey (London: Arnold, 1996), pp. 14–30; Simon During, The Cultural Studies Reader (London: Routledge, 1999); Richard Hoggart, The Uses of Literacy (New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 1991); and Raymond Williams, Culture and Society, 1780–1950 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1983).

15 http://wwwnew.towson.edu/clst/.

16 During, Cultural Studies Reader, p. 1.

17 Lynn Hunt, ed., The New Cultural History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989) and (with Victoria Bonnell) Beyond the Cultural Turn (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).

18 Sherry Ortner, ed., The Fate of “Culture”: Geertz and Beyond (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).

19 Claire C. Robertson and Nupur Chaudhuri, eds., “Revising the Experiences of Colonized Women: Beyond Binaries,” special issue, Journal of Women’s History 14, no. 4 (Winter 2003).

20 Tanika Sarkar, Hindu Wife, Hindu Nation: Community, Religion and Cultural Nationalism (New Delhi: Permanent Black; Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001) and “Semiotics of Terror: Muslim Children and Women in Hindu Rashtra,” Economic and Political Weekly, 13 July 2002, pp. 2872–2876; Manu Goswami, Producing India: From Colonial Economy to National Space (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004); and Kamela Visweswaran, “Small Speeches, Subaltern Gender: Nationalist Ideology and Its Historiography,” in Subaltern Studies IX: Writings on South Asian History and Society, ed. Shahid Amin and Dipesh Chakrabarty (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1996), pp. 83–125. For more reading on gender and colonialism, see Temma Kaplan, “Revolution, Nationalism, and Anti-Imperialism,” in A Companion to Gender History, ed. Teresa A. Meade and Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks (London: Blackwell, 2004), pp. 170–185; and Mrinalini Sinha, “Gender and Nation” in Smith, Women’s History, pp. 229–274.

21 Duane J. Corpis and Ian Christopher Fletcher, eds., “Two, Three, Many Worlds: Radical Methodologies for Global History,” special issue, Radical History Review 91 (Winter 2005).

22 For surveys of recent work on South Asia, see Barbara Ramusack, Geraldine Forbes, Sanjam Ahluwalia, and Antoinette Burton, “Women and Gender in Modern India: Historians, Sources, and Historiography,” Journal of Women’s History 14, no. 4 (2003); Nupur Chaudhuri, “Clash of Cultures: Gender and Colonialism in South and Southeast Asia”; and Barbara Molony, “Frameworks of Gender: Feminism and Nationalism in Twentieth-Century Asia,” in Meade and Wiesner-Hanks, Companion, pp. 430–444 and 513–539.

23 See, e.g., Ida Blom, Karen Hagemann, and Catherine Hall, eds., Gendered Nations: Nationalisms and Gender Order in the Long Nineteenth Century (Oxford: Oxford International, 2000); Caren Kaplan, Norma Alarcon, and Minoo Moallem, eds., Between Woman and Nation: Nationalisms, Transnational Feminisms, and the State (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1999); Social Text Collective (Anne McClintock, Aamir Mufti, Ella Shohat), eds., Dangerous Liaisons: Gender, Nation, and Postcolonial Perspectives (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997); Nira Yuval-Davis, Gender and Nation (London: Sage Publications, 1997); and Elizabeth Thompson, Colonial Citizens: Republican Rights, Paternal Privilege, and Gender in French Syria and Lebanon (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000).

24 Wendy Hesford and Wendy Kozol, eds., Just Advocacy? Women’s Human Rights, Transnational Feminisms, and the Politics of Representation (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2005).

25 Nancy Appelbaum, Muddied Waters: Race, Region, and Local History in Colombia, 1846–1948 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2003); and Jane Merritt, At the Crossroads: Indians & Empires on a Mid-Atlantic Frontier, 1700–1763 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

26 Susan Kellogg, “Depicting Mestizaje: Gendered Images of Race in Colonial Mexican Texts,” Journal of Women’s History 12, no. 3 (2000): 69–92; and Martha Hodes “The Mercurial Nature and Abiding Power of Race: A Transnational Family Story,” American Historical Review 108, no. 1 (2003): 84–118.

27 Karen Garner, “Global Feminism and Postwar Reconstruction: The World YWCA Visitation to Occupied Japan, 1947,” Journal of World History 15 (2004): 191–228; and Manako Ogawa, “‘Hull-House’ in Downtown Tokyo: The Transplantation of a Settlement House from the United States into Japan and the North American Missionary Women, 1919–1945,” Journal of World History 15 (2004): 359–388.

28 Jennifer L. Morgan, Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004).

29 Michelle Maskiell, “Consuming Kashmir: Shawls and Empires, 1500–2000,” Journal of World History 13 (2002): 27–66; and Maxine Berg, “In Pursuit of Luxury: Global History and British Consumer Goods in the Eighteenth Century,” Past and Present 182 (2004): 85–142.

30 Meade and Wiesner-Hanks, Companion.

31 Mary Jo Maynes and Anne B. Waltner, “Women’s Life Cycle Transitions in a World-Historical Perspective: Comparing Marriage in China and Europe,” Journal of Women’s History 12, no. 4 (2001): 11–21, and “Family History as World History,” in Smith, Women’s History, pp. 48–91.

32 Linda Kerber, Alice Kessler-Harris, and Kathryn Kish Sklar, eds., U.S. History as Women’s History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), p. 7.

33 Randi Warne, “Making the Gender-Critical Turn,” in Secular Theories on Religion: Current Perspectives, ed. Tim Jensen and Mikhail Rothstein (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 2000), pp. 249–260.

34 In the oral presentation of this paper, I estimated that there were more than ten such studies, and then I decided to count them, which almost tripled my estimate. Many of these have a world history angle, but their primary focus is on British men. They include J.A.Mangan and James Walvin, Middle-Class Masculinity in Britain and America, 1800–1940 (New York: St. Martin’s, 1987); Ronald Hyam, Empire and Sexuality: The British Experience (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990); Michael Roper and John Tosh, eds., Manful Assertions: Masculinities in Britain since 1800 (London: Routledge, 1991); Michael Roper, Masculinity and the British Organization Man Since 1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994); David Buchbinder, Masculinities and Identities (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1994); Donald Hall, Muscular Christianity: Embodying the Victorian Age (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994); Graham Dawson, Soldier Heroes: British Adventure, Empire, and the Imaging of Masculinity (London: Routledge, 1994); James Eli Adams, Dandies and Desert Saints: Styles of Victorian Masculinity (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell, 1995); Anne McClintock, Imperial Leather: Race, Gender and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest (London: Routledge, 1995); Mrinalini Sinha, Colonial Masculinity: The “Manly Englishman” and the “Effeminate Bengali” in the Late Nineteenth Century (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995); Joanna Bourke, Dismembering the Male: Men’s Bodies, Britain, and the Great War (London: Reaktion Books, 1996); Mark Breitenberg and Stephen Orgel, eds., Anxious Masculinity in Early Modern England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996); Michele Cohen, Fashioning Masculinity: National Identity and Language in the Eighteenth Century (London: Routledge, 1996); Jonathan Rutherford, Forever England: Reflections on Race, Masculinity and Empire (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1997); Revathi Krishnaswamy, Effeminism: The Economy of Colonial Desire (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998); David Alderson, Mansex Fine: Religion, Manliness and Imperialism in Nineteenth-Century British Culture (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998); Tim Hitchcock and Michele Cohen, English Masculinities, 1660–1800 (London: Addison Wesley, 1999); John Tosh, A Man’s Place: Masculinity and the Middle-Class Home in Victorian England (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1999); Angus McLaren, The Trials of Masculinity: Policing Sexual Boundaries, 1870–1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999); Elizabeth Foyster Wiley, Manhood in Early Modern England: Honour, Sex and Marriage (London: Longman, 1999); Susan Kingsley Kent, Gender and Power in Britain, 1640–1990 (London: Routledge, 1999); Andrew Bradstock, ed., Masculinity and Spirituality in Victorian Culture (New York: St. Martin’s, 2001); Michael Mangan, Staging Masculinities: History, Gender, Performance (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002); David Kuchta, The Three-Piece Suit and Modern Masculinity: England, 1550–1850 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002); Alexandra Shepard, Meanings of Manhood in Early Modern England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003); Kelly Boyd, Manliness and the Boys’ Story Paper in Britain: A Cultural History 1855–1940 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003); Matthew Biberman, Masculinity, Anti-Semitism and Early Modern English Literature: From the Satanic to the Effeminate Jew (London: Ashgate, 2004); Thomas A. King, The Gendering of Men, 1600–1750: The English Phallus (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2004); Paul R. Deslandes, Oxbridge Men: British Masculinity and the Undergraduate Experience, 1850–1920 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004); and John Tosh, Manliness and Masculinities in Nineteenth-Century Britain: Essays on Gender, Family, and Empire (Harlow, England: Pearson Longman, 2005). This list is probably not exhaustive, and it does not include studies of masculinity in literature, which would add at least another thirty.

35 Lerner, “U.S. Women’s History,” p. 19.

36 Northrup, “Globalization.”

In dialogue: Writing women’s history

By Marion Turner, Margaret Chowning, Virginia Trimble, and David A. Weintraub March 27, 2023

Over the last century, radical shifts in historical scholarship have filled glaring gaps in the way we understand gender from the past and in the present. By developing new methods of writing history, feminist scholars have produced more pluralistic and inclusive histories globally. In celebration of this collective effort, we asked four of our authors the following question: What do we find when we read ‘women’ into histories that often exclude them? Their responses, ranging from medieval British literature to postcolonial Mexico to modern astronomy, illuminate the necessity of excavating women and womanhood from the past and the gifts we all enjoy upon doing so. This Women’s History Month, we present this dialogue to honor the innumerable women who make up our history as well as the many who write it.

Marion Turner | The Wife of Bath: A Biography

In Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey , the heroine, Catherine Morland, confesses that she cannot make herself enjoy reading history: “The quarrels of popes and kings, with wars or pestilences, in every page; the men all so good for nothing, and hardly any women at all—it is very tiresome.” Across time, the kinds of records that we have, and the kinds of stories that historians have most wanted to tell, have undoubtedly focused on men: on kings, soldiers, parliaments and other institutions which rigorously excluded women for most of history. Women’s histories are harder to excavate, but can be glimpsed and sometimes uncovered, if you know where to look and if you want to tell those unheard stories.

My 2019 biography of the fourteenth-century poet Chaucer— Chaucer: A European Life —was the story of a privileged man’s life, a story that had been told in different ways by many male biographers before me. I tried to do many things in this book, and one of those things was to look more at the women in Chaucer’s life. Very little work had been done on his daughter Elizabeth, for example, and I was able to find out fascinating information about the nunnery in which she lived. The nuns had been chastised for dancing and partying too much and having too many overnight guests. Similarly, while medievalists had long known that the earliest Chaucer life-record involved Chaucer being given some clothes, I put this record under a closer focus. The clothes had been given to him by his female employer, the countess of Ulster, and she was choosing to dress her young page in a scandalously tight and revealing outfit—in a style that was roundly condemned by contemporary chroniclers.

“Women’s histories are harder to excavate, but can be glimpsed and sometimes uncovered, if you know where to look and if you want to tell those unheard stories.”

Nuns, parties, and fashion: these are as important in understanding Chaucer’s life and world as his work as a Member of Parliament, a Customs’ Officer, and a diplomat. And these more traditionally ‘male’ strands of history are not exclusively male either. His second trip to Italy, for instance, was made with the aim of organising a marriage alliance; he got his job as a Customs’ Officer at least partly because of his sister-in-law’s liaison with John of Gaunt.

My most recent project focuses primarily on recovering medieval women’s stories. It concentrates on an extraordinary female character—the Wife of Bath—and explores why and how she emerged in the late fourteenth century and how she has been treated across time, most recently with Zadie Smith’s 2021 adaptation. Taking this fictional woman as a focus, I created a methodology that allowed me to write a composite and experimental ‘biography,’ by delving into the lives of many fascinating medieval women.

I found, for example, a group of women who formed a union in the 1360s to complain to the king and mayor of London about price-fixing by a prominent male merchant. I found a widow who took over her husband’s skinning business, producing furs, ran it successfully, employed apprentices, and remembered a female scribe, as well as other women, in her will. I found a maid who abandoned her employer half-way across Europe in order to begin a social ascent, eventually gaining a far better job in Rome and dispensing patronage to her former employer. I found female blacksmiths, parchment-makers, and ship-owners. I found women who suffered abuse and women who made their voices heard in exposing misogyny and violence.

Perhaps most importantly, by tracing long histories, it became absolutely clear that things have not steadily improved across time. Women’s voices were sometimes suppressed more in later centuries than they were in the medieval era: for example, 1970s adaptations of the Wife of Bath were more misogynist than fifteenth-century versions. Recent events in the US have reminded us that the history of women’s rights is not an ongoing forward march. In my own study of the Wife of Bath, I saw hopeful signs in the last twenty years, when more female authors have made their voices heard and have produced intelligent and sensitive adaptations. But women’s voices are by no means heard equally with men’s, even today. The work of listening to women’s voices is as urgent now as it has ever been.

Margaret Chowning | Catholic Women and Mexican Politics, 1750–1940

Bucking the recent trend toward long, story-telling titles, I decided to call my recent book simply “ Catholic Women and Mexican Politics.” This was after some false starts that included the word “gender” somewhere in the title. Although there is gender analysis in my project—both comparisons between women’s and men’s experiences, and discussions of gendered political discourses—the research centers on the real Catholic women who led other Catholic women, first into new relationships with priests within the church and then into political battles and collaborations with priests in an effort to try to preserve the special role of the Catholic church in Mexico.

“In my field of Mexican history, by the time women’s history was dead we had hardly begun the work of retrieving women from the archive.”

My embrace of social history and women’s history is a bit of a contrarian (some would say antiquarian) position among feminist scholars, most of whom—at least since 1986, with the publication of Joan Scott’s famous essay that called gender (not women) a “useful” category of analysis—have seen “women’s history” as a more or less failed experiment. Too easy for non-feminist historians to ignore, too focused on stories of overcoming male oppression, too predictable and narrow in its themes. The very universality of those themes across time and space, thrilling in the early days of women’s history, eventually made them seem banal.

But in my field of Mexican history, by the time women’s history was dead we had hardly begun the work of retrieving women from the archive. Potentially important stories (not just about oppression; not predictable; capable of altering the traditional narrative) were abandoned in favor of a framework of gender (itself sometimes producing predictable results, though that is not my point here).

I lucked out in my project. The archive revealed not just a rather shocking change in women’s relationship to the church after the turmoil of Mexican independence (women suddenly came to lead lay associations with men as members, “governing” them in an upending of the natural order of things), but also a story of Catholic women first organizing and leading lay associations and then using those lay associations as vehicles to mobilize petition campaigns in defense of church power and privilege. Since the proper and appropriate role of the church in Mexican society was at the center of politics from independence in 1821 to well into the twentieth century, this meant women were weighing in on vital political issues. And they were being paid attention to. The way the liberal press handled women’s petitioning falls into the category of predictable gendered political discourse, but the way the conservative press squirmed and shuddered its way to an embrace of women’s petitioning was as interesting as the way the church managed to accept Catholic women as leaders of important parish organizations.

This story of Catholic women shifts the traditional narrative of Mexican history, not just by showing that women seized political power much earlier than generally thought, but also by refocusing our attention on the liberal and anticlerical reform era of the mid-nineteenth century, and away, to a certain extent, from the 1910 Revolution. I was lucky to find such a story, but I found it because I was interested in women and not just gender.

Virginia Trimble | The Sky Is for Everyone: Women Astronomers in Their Own Words

Perhaps it should be unnecessary to say (but perhaps isn’t) that we all want our stories to be as accurate as possible in history of science as well as in chemistry, cosmology, condensed matter physics, and all the rest. Properly including the contributions of women scientists, as well as other minorities, is part of this process.

Now, assuming we all agree about this goal, other questions arise. One not much asked is whether our science would have progressed more rapidly if the capabilities of women had been more fully incorporated in the past. An example from my “alternative history” file is the case of Cecilia Helena Payne (later Gaposchkin). Her 1925 astronomy PhD dissertation at Harvard was a “first” in several respects, but the astronomically important point was that she demonstrated (using observations gathered by women and men, plus theoretical contributions from men) that stars are made mostly of hydrogen and helium. She finished this about when her fellowship funding ran out, was later employed at Harvard College Observatory by Shapley, and then had to work mostly on what he ordered. This was stellar photometry, variable and binary stars, not more about chemical composition of stars.

“If you take away the (not always properly recognized) contributions made by women, do you significantly slow down the progress of science?”

My “what if” is this: What if she had continued along her own lines? Would she have discovered the differences in heavy element abundances between different populations of stars and thus laying the foundation for our understanding of the evolution of the Milky Way and other galaxies? This foundation is now credited to Eggen, Lynden-Bell, and Sandage in a 1962 paper, perhaps 30 years after she might have got there following her own path. There are surely other examples from other parts of science. Names to conjure with include Rosalind Franklin, Marietta Blau, and Lisa Meitner.

A different follow-on question is this: If you take away the (not always properly recognized) contributions made by women, do you significantly slow down the progress of science? Some of these contributions were made by wives, or sometimes sisters or daughters, of scientists who generally get most of the credit. Others came from women hired, cheaply, to act as human computers and other assistants to the men. Clued-in astronomers today would surely think of Henrietta Swan Leavitt, who discovered the period-luminosity relationship for Cepheid variable stars, used (and sometimes misused) in studies of galaxies and cosmology today.

A second example that comes incompletely to mind is the computers who worked with Chandrasekhar over the years at Chicago, carrying out complex numerical calculations that fed into his results in stellar structures, stellar dynamics, and most of the other topics on which he made major impact. It is a sobering aspect of the issue of women’s under-recognized contributions across the sciences that I am going to have to stop to look up her name, though she was parodied as Canna Helpit in a paper supposed to be by S. Candlestickmaker (meaning Chandra, whose 1983 Physics Nobel Prize primarily recognized work done 50 years earlier, before he had her or other computational assistants). His papers generally recognize her role, and some of his autobiographical material records her as catching and correcting mistakes in his own calculations. She does not, however, generally appear as a co-author, though his work would surely have proceeded more slowly without her input.

I return triumphant with the name of Donna Elbert (1928–2010) who worked with Chandra from 1948 to 1979, and whose name (thank you, Astrophysics Data System) appeared as co-author on 17 of his 187 astronomy papers published during those years. She wrote (after Chandra’s death) about working with him, and a postdoctoral fellow at UCLA celebrated her in a press release on September 18, 2022. What can or should we do about all this? Does it help to write and edit books? Such was not the primary motivation for Dr. Weintraub and me—though we hope it won’t hurt!

David Weintraub | The Sky Is for Everyone: Women Astronomers in Their Own Words

In helping Virginia Trimble compile autobiographical essays by women astronomers, I learned something particularly eye-opening from one of our chapter authors. Meg Urry is the Israel Munson Professor of Physics and Astronomy at Yale. She wrote about an encounter she had with a male astrophysicist during her postdoctoral years at MIT. At a dinner one night, the senior scientist, believing himself to be an expert on the subject, announced that there had never been any good women artists. Urry’s response to this assertion comes from a famous essay by Linda Nochlin entitled “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Nochlin explains, “As we all know, things as they are and as they have been, in the arts as in a hundred other areas, are stultifying, oppressive, and discouraging to all those, women among them, who did not have the good fortune to be born white, preferably middle class and, above all, male. The fault lies not in our stars, our hormones, our menstrual cycles, or our empty internal spaces, but in our institutions and our education.”

“Histories that include women are exceptions because the victors usually write the histories. And women, historically, have not even been participants in the fight, let alone the victors.”

And so, women have been excluded from histories of art, of science, of literature, of politics—the list of excluded areas of human endeavor is nearly unbounded. This we know. But why? The answer is simple: Throughout most of human history and in most cultures, they have been—and even continue to be—excluded from actively working in the professions of art, of science, of literature, of politics, and so much more. A person cannot be written into the story if that person is not allowed in the room.

So, what have I learned? My eyes and ears are more open. I am more attuned to and notice the double standards and barriers still placed before my female colleagues. And I am much more aware that many changes are still needed before the playing fields are level. I also recognize that this story is repeating itself. Most professions still are exclusionary. In many countries, those excluded are still women. In other countries, the “firsts” are no longer women; instead, they are persons of color or those whose sexuality is nonbinary. Histories that include women are exceptions because the victors usually write the histories. And women, historically, have not even been participants in the fight, let alone the victors. These histories open our eyes to what might have been and to what should be. The latter is more important, and these histories might help us reach a better, more inclusive future much sooner.

This exchange was facilitated by Akhil Jonnalagadda as part of the Princeton University Press Publishing Fellowship program .

Stay connected for new books and special offers. Subscribe to receive a welcome discount for your next order.

- ebook & Audiobook Cart

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Women’s History Milestones: Timeline

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 25, 2024 | Original: February 26, 2019

Women’s history is full of trailblazers in the fight for equality in the United States. From Abigail Adams imploring her husband to “remember the ladies” when envisioning a government for the American colonies, to suffragists like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton fighting for women's right to vote, to the rise of feminism and Hillary Clinton becoming the first female nominee for president by a major political party, American women have long fought for equal footing throughout the nation’s history.

And while some glass ceilings have been shattered (see: Title IX), others remain. But progress continues to be made. As Clinton said while accepting her nomination, “When there are no ceilings, the sky's the limit.”

Below is a timeline of notable events in U.S. women’s history.

Abigail Adams, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Sojourner Truth

March 31, 1776 : In a letter to her husband, Founding Father John Adams , future first lady Abigail Adams makes a plea to him and the Continental Congress to “remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the husbands. Remember, all men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies, we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation.”

July 19-20, 1848 : In the first women’s rights convention organized by women, the Seneca Falls Convention is held in New York, with 300 attendees, including organizers Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott . Sixty-eight women and 32 men (including Frederick Douglass ) sign the Declaration of Sentiments, which sparked decades of activism, eventually leading to the passage of the 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote.

January 23, 1849: Elizabeth Blackwell becomes the first woman to graduate from medical school and become a doctor in the United States. Born in Bristol, England, she graduated from Geneva College in New York with the highest grades in her entire class.

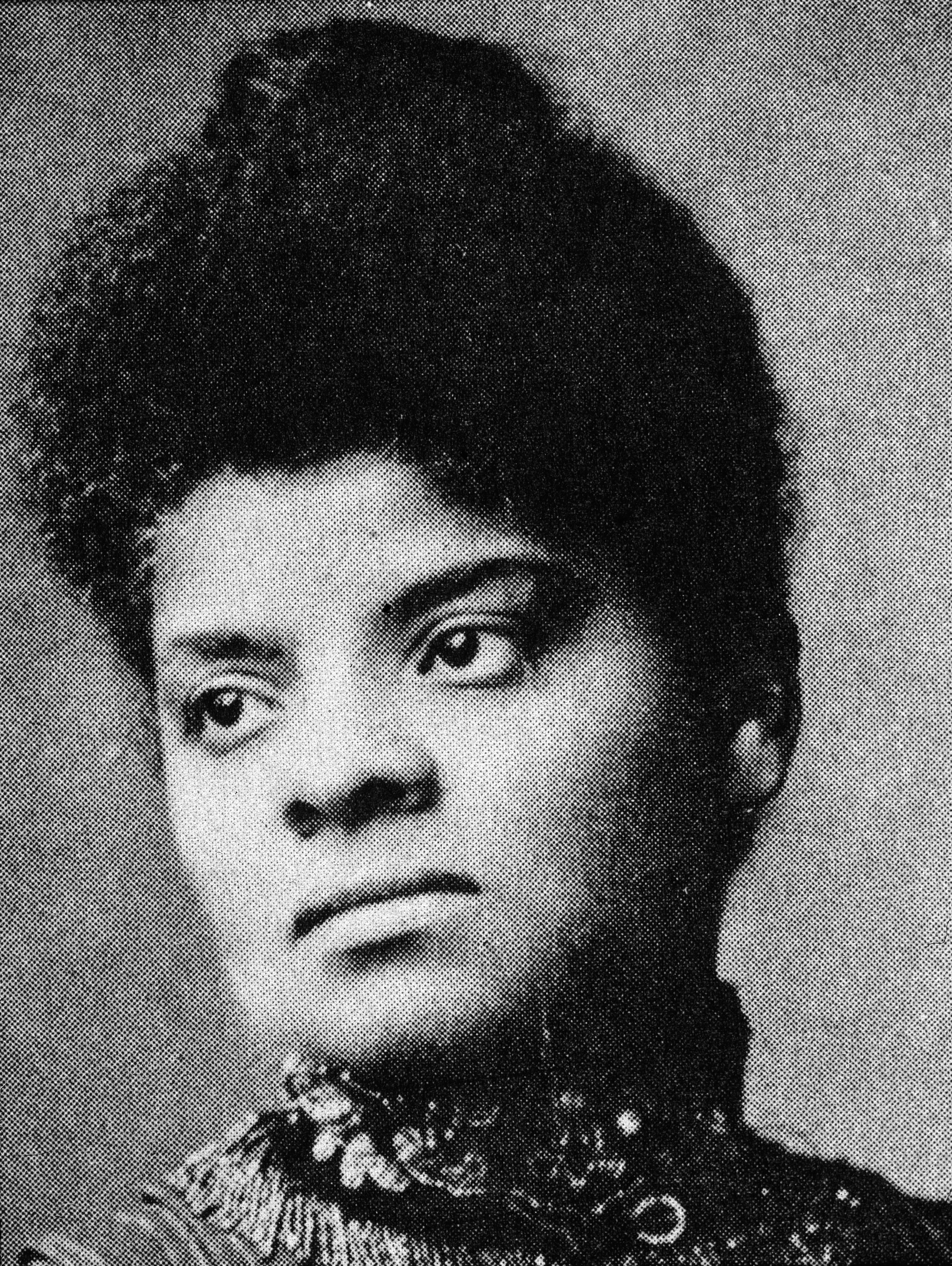

May 29, 1851 : A formerly enslaved worker turned abolitionist and women’s rights activist, Sojourner Truth delivers her famous "Ain't I a Woman?" speech at the Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. “And ain't I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man—when I could get it—and bear the lash as well! And ain't I a woman? I have borne 13 children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain't I a woman?”

Contemporaneous reports of Truth’s speech did not include this slogan, and quoted Truth in standard English. In later years, this slogan was further distorted to “Ain’t I a Woman?”, reflecting the false belief that as a formerly enslaved woman, Truth would have had a Southern accent. Truth was, in fact, a New Yorker.

Dec. 10, 1869 : The legislature of the territory of Wyoming passes America’s first woman suffrage law, granting women the right to vote and hold office. In 1890, Wyoming is the 44th state admitted to the Union and becomes the first state to allow women the right to vote.

Suffrage Movement, 19th Amendment

May 15, 1869 : Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton found the National Woman Suffrage Association, which coordinated the national suffrage movement. In 1890, the group teamed with the American Woman Suffrage Association to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association.

October 16, 1916: Margaret Sanger opens the first birth control clinic in the United States. Located in Brownsville, Brooklyn, her clinic was deemed illegal under the “Comstock Laws” forbidding birth control, and the clinic was raided on October 26, 1916. When she had to close two additional times due to legal threats, she closed the clinic and eventually founded the American Birth Control League in 1921—the precursor to today’s Planned Parenthood.

April 2, 1917 : Jeannette Rankin of Montana, a longtime activist with the National Woman Suffrage Association, is sworn in as the first woman elected to Congress as a member of the House of Representatives .

Aug. 18, 1920 : Ratification of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is completed, declaring “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” It is nicknamed “The Susan B. Anthony Amendment” in honor of her work on behalf of women’s suffrage.

May 20-21, 1932 : Amelia Earhart becomes the first woman, and second pilot ever ( Charles Lindbergh was first) to fly solo nonstop across the Atlantic.

February 16, 1945: The Alaska Equal Rights Act is signed into law. The act is the first state or territorial anti-discrimination law enacted in the United States in the 20th century. Elizabeth Peratrovich, a Tlingit woman who was Grand President of the Alaska Native Sisterhood, spearheaded the effort to end discrimination against Alaska Natives and other non-white residents.

Rosa Parks, Civil Rights, Equal Pay

Dec. 1, 1955 : Black seamstress Rosa Parks refuses to give up her seat to a white man on a bus in Montgomery, Ala. The move helps launch the civil rights movement .

May 9, 1960: The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approves the first commercially produced birth control pill in the world, allowing women to control when and if they have children. Margaret Sanger initially commissioned “ the pill ” with funding from heiress Katherine McCormick.

June 10, 1963 : President John F. Kennedy signs into law the Equal Pay Act , prohibiting sex-based wage discrimination between men and women performing the same job in the same workplace.

July 2, 1964 : President Lyndon B. Johnson , signs the Civil Rights Act into law; Title VII bans employment discrimination based on race, religion, national origin or sex.

June 30, 1966 : Betty Friedan , author of 1963’s The Feminine Mystique , helps found the National Organization for Women (NOW), using, as the organization now states , “grassroots activism to promote feminist ideals, lead societal change, eliminate discrimination, and achieve and protect the equal rights of all women and girls in all aspects of social, political, and economic life.”

Title IX, Battle of the Sexes

June 23, 1972 : Title IX of the Education Amendments is signed into law by President Richard Nixon . It states “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance."

Jan. 22, 1973 : In its landmark 7-2 Roe v. Wade decision, the U.S. Supreme Court declares that the Constitution protects a woman’s legal right to an abortion. In June 2022, the Supreme Court overturned the ruling .

Sept. 20, 1973 : In “ The Battle of the Sexes ,” tennis great Billie Jean King beats Bobby Riggs in straight sets during an exhibition match aired on primetime TV and drawing 90 million viewers. “I thought it would set us back 50 years if I didn’t win that match,” King says after the match. “It would ruin the women’s [tennis] tour and affect all women’s self-esteem.”

Sandra Day O'Connor, Sally Ride

July 7, 1981 : Sandra Day O’Connor is sworn in by President Ronald Reagan as the first woman to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court. She retires in 2006, after serving for 24 years.

June 18 1983 : Flying on the Space Shuttle Challenger, Sally Ride becomes the first American woman in space.

July 12, 1984 : Democratic presidential nominee Walter Mondale names U.S. Rep. Geraldine Ferraro (N.Y.) as his running mate, making her the first woman vice president nominee by a major party.

March 12, 1993 : Nominated by President Bill Clinton , Janet Reno is sworn in as the first female attorney general of the United States.

Jan. 23, 1997 : Also nominated by Clinton, Madeleine Albright is sworn in as the nation’s first female secretary of state.

Sept. 13, 1994 : Clinton signs the Violence Against Women Act as part of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, providing funding for programs that help victims of domestic violence, rape, sexual assault, stalking and other gender-related violence.

Nancy Pelosi, Hillary Clinton, Kamala Harris

Jan. 4, 2007 : U.S. Rep. Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) becomes the first female speaker of the House. In 2019, she reclaims the title, becoming the first lawmaker to hold the office two times in more than 50 years.

Jan. 24, 2013 : The U.S. military removes a ban against women serving in combat positions .

July 26, 2016 : Hillary Clinton becomes the first woman to receive a presidential nomination from a major political party. During her speech at the Democratic National Convention, she says, “Standing here as my mother's daughter, and my daughter's mother, I'm so happy this day has come.”

January 20, 2021 : Kamala Harris is sworn in as the first woman and first woman of color vice president of the United States. "While I may be the first woman in this office, I will not be the last," Harris said after getting elected in November.

The daughter of Jamaican and Indian immigrants, Harris served as California’s first Black female attorney general and won election to the U.S. Senate in 2016. She made her own unsuccessful presidential bid before being selected by former Vice President Joe Biden as his running mate.

Timeline of Legal History of Women in the United States, National Women’s History Alliance Seneca Falls Convention, Library of Congress Sojourner Truth’s "Ain’t I a Woman?” Sojourner Truth Memorial Woman Suffrage, National Geographic Society Suffragists Unite: National American Woman Suffrage Association, National Women’s History Museum A record number of women will be serving in the new Congress. PEWResearch.org . A List of Firsts for Women in This Year’s Midterm Elections. NPR.org .

HISTORY Vault: Women's History

Stream acclaimed women's history documentaries in HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

History of Women in the United States Essay

Introduction, early women’s history.

- Women in 19th Century US

Changing Roles

Purpose: To inform the audience about History of women in the United States.

Thesis Statement: The changing gender roles in American society are best depicted through a tour of the history of the United States.

Interesting opening statement: “Like their personal lives, women’s history is fragmented, interrupted; a shadow history of human beings whose existence has been shaped by the efforts and the demands of others.” – Elizabeth Janeway (Janeway)

Relevance: History of women in North America has been marred by masculine bias and dominance. Jane Austen believes that history talks of all that is done by men and is irrelevant, but never of women: “But history, real solemn history, I cannot be interested in…I read it a little as a duty, but it tells me nothing that does not either vex or weary me. The quarrels of popes and kings, with wars or pestilences, in every page; the men are all so good for nothing, and hardly any women at all — it is very tiresome.” (Austen) It has been a long journey for women – from being second-class citizens confined to the interior life of home and childcare. A documentary made by the History Channel on Women’s History pointed out that it was not until the mid-nineteenth century was the women’s right movement started in the US. The history of US talks of women only after the mid-19 th century and so our time starts then.

Credibility: I am a student of gender studies and am well acquainted with women who have made their mark in the history of the US. I have come across women who were the unsung heroes and supporters of the most admired men in the US as well as women who were famous for their own deed.

Thesis: The changing gender roles in American society are best depicted through a tour of the history of the United States. US history is smeared with women who have shared their lives with many famous women and so to better understand them it is necessary to understand the changing position and work of women chronologically.

Preview: So let us begin our historic journey through the lives of women who have left a permanent imprint on American history.

Transition: What does the early women’s history have to tell us?

Women losing the right to vote in many American states in the late 18 th century or those where she is considered to be a sub-set to their male counterparts? Women in early America did not have the right to their own property, sign a contract or maintain their own wages (Women’s History Resources ). The conventional idea during the time was the intensity of physical or intellectual activity would be too much for the fragile biology of a woman. Therefore, women were restrained from pursuing serious education and were idolized as objects of beauty. This idea was predominant in the early American history.

Daniel Defoe in his article titled (On) The Education Of Women states, “I have often thought of it as one of the most barbarous customs in the world, considering us as a civilized and a Christian country, that we deny the advantages of learning to women. We reproach the sex every day with folly and impertinence; while I am confident, had they the advantages of education equal to us, they would be guilty of less than ourselves.” (Defoe)

However the only occupation that women were granted to do were as servants and midwifes, and that too due to dire financial needs. The roles of women were confined to their house and no more.

Transition: Though women were no better off in active participation in social life, they were more silent partners with their husbands or families in shaping the nation.

Women in 19 th Century US

First, we will talk about women who featured silently along with famous men as mother, or wife, or daughters and made a definite impact on history. In this respect, one must mention Abigail Adams (1744-1818). She was the wife of the second President of the United States, President John Adams, and mother of President John Quincy Adams. She was known to have an active interest in politics and bore Federalist ideals. She was one of the forerunners of women’s rights. In addition, there were other first ladies who assumed the cause of betterment of the US social life and nation.

Did you know a woman first made the American Flag? Yes, the American flag was made by a woman named Betsy Ross. Some women fought wars like the daring Deborah Sampson, who truly depicted the women of power as she fought in the Revolutionary War disguised as a man, and Mary Ludwig Hays McCauley “Molly Pitcher”. Thus in the 19 th century there were numerous women who excelled as writers, social activists, medical practitioners, education, etc. Names like Florence Nightingale, Susan B. Anthony, Lucy Stone, Harriet Beecher Stowe, etc. will always remain fixed in the mind of American history. These women broke the bondage of being domesticated as procreators and homemakers, and came out as individuals in their own right. These women brought forward the true cause for women in the US.

Transition: Industrial revolution ushered in the changes in the lives of women in the US.

From the advent of 20 th century, there arose women of means. Women, who earned degrees, fought wars, took up professional qualification and competed in the men’s world. In this respect, we come across famous women like Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman physician and founder of New York Infirmary for Women and Children and Women’s Medical College. During this time, there came famous female authors like Emily Dickenson and Louisa May Alcott, painters and sculptors like Mary Cassatt and Edmonia Lewis, scientist Marie Curie, and many more. Evidently, during this period there was a transformation of domestic and social structure where women were gradually breaking the shackles of domestic life and becoming independent.

Transition : I have so far explored the upward movement of women up in social hierarchy in the speech.

Thesis/Summary: The changing roles of women in US history show the tale of changing gender roles in US social history.

Memorable Close: Women have been transgressed throughout history. However, it was they who slowly made their mark in a patriarchal world and etched their name in history. Today women in the US have attained a position wherein they are no longer subjugated by men; rather walk with them as true equals.

Austen, Jane. Wisdomequote. 2009. Web.

Defoe, Daniel. Brainly Quotes. 2009. Web.

Janeway, Elizabeth. iWise. 2009. Web.

Women’s History Resources. 2002. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, November 20). History of Women in the United States. https://ivypanda.com/essays/history-of-women-in-the-united-states/

"History of Women in the United States." IvyPanda , 20 Nov. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/history-of-women-in-the-united-states/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'History of Women in the United States'. 20 November.

IvyPanda . 2021. "History of Women in the United States." November 20, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/history-of-women-in-the-united-states/.

1. IvyPanda . "History of Women in the United States." November 20, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/history-of-women-in-the-united-states/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "History of Women in the United States." November 20, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/history-of-women-in-the-united-states/.

- "And Our Flag Was Still There" by B. Kingsolver

- Samuel Adams: Radical Puritan

- Constitutionality of Flag Burning

- Flag Desecration: US Constitution Amendement

- George Washington's and John Adams's Policies

- Flags of Our Fathers

- Flying of the Confederate Flag Over the Alabama State Capitol in 1988

- Abigail Adams' Views on Republican Motherhood

- The Way the American Flag Was Deployed Culturally Following Sept 11th

- History of John Adams’ Presidency: Ideological and Personality Differences

- Cosmetics Industry and Female Identity

- Women in Sciences Up to 1980

- Taliban Culture and Its Effect on Women

- Contribution of Women in Blues

- Women History in Ancient China

Female Cultural Production in Modern Italy pp 1–16 Cite as

New Perspectives on the Roles of Women in Italy’s Modern Intellectual History

- Sharon Hecker 4 &

- Catherine Ramsey-Portolano 5

- First Online: 13 April 2023

190 Accesses

Part of the book series: Italian and Italian American Studies ((IIAS))