Suisse Enregistré à son insu, son entretien RH finit sur le darknet

Taïwan Au moins 7 morts et plus de 700 blessés après un puissant séisme

Genève Excédé par le robot-tondeuse, il caillasse le jardin voisin

Vaud Elle donne ses chats avant de se raviser... mais trop tard

Crues de la Seine La répétition de la cérémonie d’ouverture des JO reportée

Football Pep Guardiola riposte: «Haaland est le meilleur attaquant du monde»

États-unis un étudiant projeté au sol par une violente tornade.

États-Unis «Littéralement N’importe Qui D’autre» veut devenir président

Fooby widget - do not move.

États-Unis Shannen Doherty prépare son décès en vendant ses meubles

États-unis un pilote craque et lance le pare-chocs de sa voiture sur un autre concurrent.

France Jean-Marie Le Pen, 95 ans, placé «sous protection juridique»

Zurich La Ville forcée de créer une piste cyclable à 17'000 fr. le mètre

Suisse Près de 30 degrés le week-end prochain

Guerre en ukraine revendiquée par l'ukraine, cette frappe en russie est historique.

Conflit Israël-Hamas La situation à Gaza est «pire que catastrophique»

Suisse Des silencieux et la vision nocturne pour aider les chasseurs

Martigny (VD) Onze chiots sont nés à la Fondation Barry

Finlande Journée de deuil après la mort par balle d’un élève dans une école

Venezuela L’homme le plus vieux du monde s’éteint à l’âge de 114 ans

Hockey sur glace Entre amitié et rivalité, le derby ne manque pas de sel

Conflit Israël-Hamas «L’erreur» d’Israël qui a tué sept humanitaires à Gaza

Espagne Il fait d'un ancien lieu de culte sa résidence principale

États-Unis Kanye West accusé de racisme et d’antisémitisme par un ex-employé

Salvador Trois quarts des membres des gangs sont sous les verrous

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Mind & Body Articles & More

How journaling can help you in hard times, stressed and isolated try expressing your thoughts and feelings in writing..

On April 1, I had been quarantining in my downtown apartment for two weeks, and it was starting to become clear that this coronavirus thing wasn’t going away anytime soon.

As I often do in tough times, I turned to journaling. I decided I’d keep a record of my quarantine life through the month of April, a way to remember this crazy historical moment and process my feelings.

Now it’s August, and my daily journal continues. I’ve left my building about two dozen times since I started journaling, so its contents aren’t all that exciting—tidbits of everyday life, news about social distancing rules and reopening stages, moments of worry and loneliness and cabin fever and gratitude.

I know I’m not the only one with a pandemic journal. In fact, hundreds of people have written journal entries on the Pandemic Project website , a resource created by psychology researchers that offers writing prompts to help people explore their experiences and emotions around COVID-19.

At a time when the days blend into each other, journaling is helping people separate one from the next and clear out the distressing thoughts invading our heads (and our dreams ). Research also suggests it might be helping our health and immune systems, the very things many of us are worried about.

Although there are some pitfalls to journaling—ways of doing it that might backfire—it’s one of those rare and valuable mental health tools that doesn’t require you to leave your house or even see another human being.

The power of opening up

People had been keeping diaries long before scientists thought to put them under microscopes. But in the past 30 years, hundreds of studies have uncovered the benefits of putting pen to paper with your deepest thoughts and feelings.

According to that research, journaling may help ease our distress when we’re struggling. In a 2006 study , nearly 100 young adults were asked to spend 15 minutes journaling or drawing about a stressful event, or writing about their plans for the day, twice during one week. The people who journaled saw the biggest reduction in symptoms like depression, anxiety, and hostility, particularly if they were very distressed to begin with. This was true even though 80 percent had seldom journaled about their feelings and only 61 percent were comfortable doing so.

Why do we avoid journaling?

For one, it isn’t always pleasant; I know that I sometimes have to force myself to sit down and do it. Cathartic is probably a better word. In fact, some research suggests that we can feel more anxious , sad, or guilty right after we write.

But in the long term, we can expect to cultivate a greater sense of meaning as well as better health. Various studies have found that people who do a bout of journaling have fewer doctor visits in the following half year, and reduced symptoms of chronic disease like asthma and arthritis.

Can your diary keep you healthy?

Other research finds that writing specifically boosts our immune system, good news when the source of so much stress today is an infectious virus.

One older study even found that journaling could make vaccines more effective. In the experiment, some medical students wrote for four days in a row about their thoughts and feelings around some of the most traumatic experiences of their lives, from divorce to grief to abuse, while others simply wrote down their daily events and plans. Then, everyone received the hepatitis B vaccine and two booster shots.

According to blood tests, the group who journaled about upsetting experiences had higher antibodies right before the last dose and two months later. While the other group had a perfectly healthy response to the vaccine, the authors write, journaling could make an important difference for people who are immune-compromised or for vaccines that don’t stimulate the immune system as well.

“Expression of emotions concerning stressful or traumatic events can produce measurable effects on human immune responses,” write the University of Auckland’s Keith J. Petrie and his colleagues.

Greater Good’s Guide to Well-Being During Coronavirus

Practices, resources, and articles for individuals, parents, and educators facing COVID-19

Journaling could also boost our immune system once we’ve been infected with a virus. In another study , researchers recruited undergraduate students who tested positive for the virus that causes mononucleosis, which persists in the body after infection and has the potential to flare up. Three times weekly for 20 minutes, some wrote about a stressful event—like a breakup or a death—while others wrote about their possessions.

Based on blood samples taken before and after, writing about stress increased people’s antibodies—an indication that the immune system has more control over the latent virus in the body—compared to more mundane writing. It also seemed to help them gain a deeper understanding of their stress and see more positives to it.

Why journaling works

What’s the secret to the humble diary? It turns out journaling works on two different levels, having to do with both our feelings and our thoughts.

First, it’s a way of disclosing emotions rather than stuffing them down, which is known to be harmful for our health. So many of us have secret pain or shame that we haven’t shared with others, swarming around our brains in images and emotions. Through writing, our pain gets translated into black-and-white words that exist outside of ourselves.

“I’m able to organize thoughts and feelings on paper so they no longer take up room in my head,” says Allison Quatrini, an assistant professor at Eckerd College who has been journaling for years and started a COVID-19 journal in April. “If I get them out on the page and clear the mental decks, it sets up the rest of the day to not only be more productive but be more relaxed.”

On the thinking level, writing forces us to organize our experiences into a sequence, giving us a chance to examine cause and effect and form a coherent story. Through this process, we can also gain some distance from our experiences and begin to understand them in new ways, stumbling upon insights about ourselves and the world. While trauma can upset our beliefs about how life works, processing trauma through writing seems to give us a sense of control.

“Journaling is a tool to put our experiences, thoughts, beliefs, and desires into language, and in doing so it helps us understand and grow and make sense of them,” says Joshua Smyth, a distinguished professor of biobehavioral health and medicine at Penn State University, who coauthored the book Opening Up by Writing It Down with pioneering journaling researcher James Pennebaker.

How to start a journaling practice

While you can journal in many different ways, one of the most well-studied techniques is called Expressive Writing . To do this, you write continuously for 20 minutes about your deepest thoughts and emotions around an issue in your life. You can explore how it has affected you, or how it relates to your childhood or your parents, your relationships or your career.

Expressive Writing is traditionally done four days in a row, but there isn’t anything magical about this formula. Studies suggest you can journal a few days in a row, a couple times a week, or just once a week; you can write for 10 or 15 or 20 minutes; and you can keep journaling about the same topic or switch to different ones each time.

Expressive Writing

A simple, effective way to work through an emotional challenge

For example, the Pandemic Project offers several prompts to inspire your writing. You can write a basic entry about your general thoughts and feelings around COVID-19, or dig into more specific topics like the following:

- Social life: How is your social world changing, how does that make you feel, and how are you handling it?

- Work and money: How do you feel about your financial situation, and how has your job changed?

- Uncertainty: Where is your anxiety and sense of uncertainty coming from, and how can you cope with it?

“Many people often start writing about COVID-19 and then begin writing about other topics that are bothering them more than they thought,” notes the Pandemic Project website, which was created by Pennebaker and his research team. “This is what expressive writing is good for. Use it to try to understand those problems that are getting under your skin.”

In my journal, I’ve found myself exploring the issue of control . My constant instinct is to organize and plan out life, but that’s been impossible in the midst of a massive, unpredictable crisis. Journaling also let me ponder the lessons I want to take away from this experience around flexibility, acceptance, and letting go.

The do’s and don’ts of a diary

A 2002 study does suggest that journalers should beware of rehashing the same difficult feelings over and over in writing.

In the experiment, over 120 college students journaled about a stressful or traumatic event they were experiencing, like troubles at school, conflicts with their partner, or a death in the family. They were instructed to write for at least 10 minutes, twice a week, over the course of a month. Some students wrote about their deepest thoughts and feelings—including how they try to make sense of the stress and what they tell themselves to cope with it—while others wrote about their feelings only.

During the month, the group who wrote about feelings and thoughts experienced more growth from the trauma: better relationships with others and a greater sense of strength, appreciation for life, and new possibilities for the future. They seemed to be more aware of the silver linings of the experience, while the group who focused on emotions expressed more negative emotions over time and even got sick more often that month.

The point here is that the most effective journaling moves from emotions to thoughts over time. We start expressing our feelings, allowing ourselves to name them; after all, jumping to thoughts too quickly could mean we’re over-analyzing or avoiding. But eventually, we do start to make observations, notice patterns, or set goals for the future.

The Science of Happiness Course

Launching September 1, The Science of Happiness is a self-paced, online course featuring research and practices on empathy, mindfulness, self-compassion, and more. Learn science-based principles and practices for strong relationships and a meaningful life. Register here .

This has been the case for Allison Quatrini, who usually writes for a half hour in the morning about whatever’s going through her mind—from the losses she’s experiencing during the pandemic to her work or romantic relationship. It allows her to put into words how much her life has been disrupted, normalize the range of emotions she’s been feeling, and brainstorm ways forward.

“It helps me make sense of the way that I’m feeling right now,” she says. “Why do I feel not very motivated, why do I feel bored, why do I feel sad? It’s also useful in admitting to myself what is going on [and] why it’s been very challenging to deal with this.”

In addition to writing, you might also consider adding drawings to your journal. In a 2003 study , people either journaled, made drawings, or journaled and drew about a negative experience from the past that still upset them, like relationship troubles or loss. According to surveys before and after, the group who wrote and drew saw the biggest improvements in their mood after three weekly, 20-minute sessions. Drawing without writing actually made people’s moods worse, though. The researchers speculate it may have dredged up difficult feelings without offering a way to process them.

If writing is challenging, speaking your feelings aloud may work just as well. In that mono study, there was another group of students who recorded themselves talking about their stress. This group ended up showing the strongest immune responses to the dormant virus in their bodies. They also seemed to be doing the best psychologically, gaining insight and a positive perspective on their stress, improving in self-esteem, and engaging in healthier coping strategies. The researchers suspect that talking—even to a voice recorder—may feel similar to sharing our feelings with a loved one.

Freedom of expression

Sharing with a trusted confidant might seem even better than writing down feelings, as it serves a similar purpose and offers us warmth and validation that a piece of paper can’t provide. And that’s probably true, write Pennebaker and Smyth in Opening Up by Writing It Down .

One study , for example, found that people who talked to a therapist for four short daily sessions showed more positive emotion and less negative emotion. They gained understanding and perspective, and they made healthy behavior changes similar to people who journaled.

Therapy also seemed to be less unpleasant than writing. In fact, when Pennebaker originally envisioned journaling as a mental health exercise, he was inspired by the benefits of therapy—but mindful that not everyone has the means or the inclination to talk to a professional about their problems.

Of course, confessing to friends or partners isn’t without its complications. Sometimes our loved ones are overloaded by their own stresses, or they can’t offer the right kind of support—and may even make us feel worse. Other times, our secrets feel too vulnerable to speak out loud.

No matter what, if we’re talking to another human, our brains will be doing a constant calculation about what to say or not say, how they might react, and how we will be perceived, says Smyth. Confiding on paper can be a valuable alternative and a way to express ourselves with absolute freedom. Journaling lets us process secrets before we reveal them to others.

For Quatrini, who researches and teaches about China, the stress of the pandemic has an extra layer: With the disruption to U.S.-China relations and travel, she’s concerned about the future of her research. The immensity of that loss and uncertainty—and how it was affecting her day-to-day feelings and relationships—only became clear to her when she wrote about it.

“My entire life has been turned upside down and I don’t know if it will ever right itself,” she says. “Without the journal, I think I would not have figured that out.”

About the Author

Kira M. Newman

Kira M. Newman is the managing editor of Greater Good . Her work has been published in outlets including the Washington Post , Mindful magazine, Social Media Monthly , and Tech.co, and she is the co-editor of The Gratitude Project . Follow her on Twitter!

You May Also Enjoy

This article — and everything on this site — is funded by readers like you.

Become a subscribing member today. Help us continue to bring “the science of a meaningful life” to you and to millions around the globe.

- Gouvernement Attal

- Guerre Israël-Hamas

- Guerre en Ukraine

- #20MinutesPlaisir

TADAMM fait avancer le cinéma immersif à la vitesse des Lumière

En créant un village immersif itinérant, l’entreprise française renoue avec l’esprit forain des débuts du cinéma

- Les + partagés

10:21 | Evasion

Un tunnel artisanal découvert en direction de la prison de la Santé

10:19 | DEVOIR DE RÉSERVE

Un agent de Saint-Malo surpris en train de dégrader des affiches du RN

10:17 | Pas mal non ? C'est français

« Wemby » tout proche du quadruple double après son titre de rookie du mois

10:01 | Carnet rose

Une femme accouche dans le métro à Paris, le bébé aura un Navigo gratuit

09:53 | drame

En Californie, une ado abattue par les policiers venus la secourir

09:53 | violence

En Isère, un homme armé sème la panique dans un village des marques

09:47 | Argent

Comment rattraper ses mauvaises notes sur Parcoursup ?

09:31 | TUTELLE

Jean-Marie Le Pen placé « sous régime de protection juridique »

09:21 | SERVEZ-VOUS

Dans ces cimetières nantais, la libre cueillette pour fleurir les tombes

09:13 | mauvaise surprise

Une fillette ingère du cannabis caché dans un œuf Kinder, dans le Béarn

09:10 | RIDEAU

L’actrice américaine Barbara Rush s’est éteinte à 97 ans

09:09 | ACCIDENT

L’automobiliste qui a fauché une jeune femme à Brest participait à un rodéo

09:08 | SÉCURITÉ

« Pas de menace terroriste spécifique » pour les JO, assure Oudéa-Castéra

09:06 | quartet

Quand une comédie française parle de sexe « Et plus si affinités »

09:03 | Intempéries

Les pics de crues atteints en Bourgogne dans les endroits les plus touchés

08:51 | GOAT

Cristiano Ronaldo impliqué dans cinq buts en une mi-temps avec Al-Nassr

08:45 | catastrophe

A Taïwan, au moins sept morts et 700 blessés après un puissant séisme

08:32 | ASSISES

Un cardiologue jugé en appel pour viol et agressions sur des patientes

08:13 | actualités

Mea culpa d’Israël, enquête sur la mort d’Emile et violences sexuelles

08:03 | bilan final

Six gardes à vue, 600 verbalisations et des saisies après une teuf à Quimper

08:02 | FOOTBALL

Après son improbable renaissance, l’OL a vécu une demi-finale « magique »

07:47 | PHOTO INSTANTANÉE

L’Instax mini 99, un appareil photo instantané qui fait de l’effet !

07:21 | ENQUETE

86 % des plaintes pour des violences sexuelles classées sans suite

07:02 | animaux

Insolite : cette tortue se nourrit d’éponges de mer !

06:42 | LIVE

Guerre en Ukraine EN DIRECT : L’Otan va discuter d’un fonds d’aide à Kiev…

02/04/24 | avancée

L’appareil d’IRM le plus puissant du monde a livré ses premières images

02:19 | FOOTBALL

L’arbitrage « exécrable » de Stéphanie Frappart a-t-il coulé Valenciennes ?

02/04/24 | PROCES

Manu Levy de NRJ assigné aux prud’hommes pour « harcèlement moral »

06:02 | GAZA

Israël reconnaît une « grave erreur » en tuant sept membres d’une ONG

02/04/24 | Violences sexistes et sexuelles

Viol, enquête, marche blanche… Le point sur la mort de Shanon, 13 ans

02/04/24 | MINUTIE

Bientôt une commission d’enquête sur l’aggravation de la dette sous Macron

03:37 | rétropédalage

Après un essai de trois ans, l’Oregon va repénaliser les drogues

02:43 | PATRIMOINE

Taylor Swift devient milliardaire juste avec sa musique, une première

02/04/24 | point presse

Après la mort d’Emile, un squelette incomplet et des « hypothèses ouvertes »

02/04/24 | Récap'

la Russie grignote le pays au 769e jour de la guerre en Ukraine

02/04/24 | Prévoyance

Shannen Doherty a entrepris un vide-grenier bien triste

02/04/24 | LIVE

Mort d’Emile EN DIRECT : « C'est une étape importante pour l'enquête mais…

02/04/24 | meurtre

Un cadavre avec des traces de balles découvert à Rambouillet

02/04/24 | Pyrénées

L’énorme rocher dévale la montagne et s’arrête juste devant les immeubles

02/04/24 | STUPEFIANTS

Héroïne, cannabis, ecstasy... Jackpot pour les gendarmes du Finistère

02/04/24 | Sans nouvelles

Inquiétude dans le village du couple de boulangers portés disparus à Madère

02/04/24 | Cadavre

Que sait-on du corps d’une femme retrouvée à Nanterre dans une voiture ?

02/04/24 | ACCIDENT

Un motard sous cocaïne écroué après la mort de sa passagère près de Nantes

02/04/24 | Affaires (dé) classées

Aidez la justice à résoudre des cold cases en regardant des vidéos

Maddyness, l’incontournable de la French Tech, livre sa « Maddy Keynote »

Avec Maddyness, Louis Carle et Etienne Portais ont vu passer les pitchs de toutes les start-up de France depuis dix ans… A leur tour de pitcher la Maddy Keynote, leur conférence événement

Premiers Secours, Umay… Cinq applis qui sauvent des vies

Empêcher un arrêt cardiaque grâce à son téléphone, donner l’alerte d’une pression du doigt… Cinq applications incontournables pour secourir ou être secouru

Se former aux premiers secours en ligne, les comptes qui comptent

Vous cherchez des tutos pour apprendre les gestes de premiers secours ? On vous guide dans cette démarche altruiste

De De Gaulle à Macron, une histoire électro de la Ve République au Trianon

La tournée République Electronique fait escale à Paris le 15 mars, au Trianon

20 Minutes et la Croix-Rouge française lancent un numéro spécial secourisme

Les secouristes bénévoles jouent un rôle crucial dans notre société

Kristen Stewart trouve sa couverture pour « Rolling Stone » bien trop sage

L’actrice s’y affiche pourtant une main glissée dans son slip (masculin)

Un Sommet pour célébrer l’engagement « qui part du bas »

Le Sommet de l’engagement, dont 20 Minutes est partenaire, se tient demain à Paris

Comment expliquer la longévité du Zidane du Trot ?

Avec des milliers de victoires à son actif, dont cinq Grand Prix d’Amérique, le « Zidane du trot » reste plus que jamais sur le devant de la scène

Marolles-en-Brie, la ville où le cheval est roi

Cette commune du Val-de-Marne de près de 5.000 habitants accueille 1.500 chevaux dans le prestigieux domaine de Grosbois

- Page courante : 1

Article abonné

"20 minutes", le dernier survivant des journaux gratuits dans l'incertitude économique

Vingt ans après.

Publié le 16/03/2022 à 18:38

Imprimer l'article

Partager l'article sur Facebook

Partager l'article sur Twitter

Le média a fêté son vingtième anniversaire mardi 15 mars 2022. Dernier rescapé de ce modèle économique, il a traversé de fortes turbulences, notamment avec la crise du Covid. Peut-il tenir encore longtemps ?

Survivra-t-il encore 20 ans ? Il y a deux décennies paraissait le premier numéro du quotidien 20 Minutes , le 15 mars 2002. Lancé quelques années plus tôt à Zurich en Suisse, 20 Minutes se présente à l'époque comme un concept innovant, « une démarche humaniste visant à rendre l’information accessible à tous ». Uniquement financé par la publicité, il entend séduire une nouvelle génération de lecteurs, habituée à une information synthétique, celle de la télévision et de la radio.

Pour Marie-Christine Lipani, maître de conférences en sciences de l’information, l'objectif des journaux gratuits était et reste de « réconcilier les jeunes avec l’information, ne se sentant plus concernés par les sujets traités par la presse nationale » .

Débuts controversés

Par Mathilde Karsenti

Contenu sponsorisé

Nos abonnés aiment.

Les indiscrétions de "Marianne" : Macron, ce RH tout-puissant et la piñata Ruffin

Confidentiel.

"Ma jambe, c'est 'Elephant Man' !" : comment les fluoroquinolones m'ont pourri la vie

De la "théorie Rey" à l'affaire Jean-Michel Trogneux... Cette rumeur qui inquiète l’Élysée

Européennes : Valérie Hayer, tête de liste de la Macronie... et du vide intersidéral

Le portrait crashé, plus de société.

Nicolas Thierry, député écolo élu à Bordeaux : "Le scandale des PFAS est comparable à celui de l’amiante"

Ces établissements privés qui virent leurs élèves vers le public bientôt sanctionnés ?

L'œil d'Audrey Jougla

Audrey Jougla : "Céder à cette génération d'offusqués, c’est signer la mort de l’école"

Contrôles mollassons

"À ce rythme, c'est un contrôle tous les 1500 ans" : ce rapport au vitriol sur l'encadrement des écoles privées

Zones d'ombre

Mort d'Émile : accident ou piste criminelle... ces mystères que les enquêteurs doivent dissiper

Info Marianne

JO de Paris 2024 : un test antidrones confidentiel réalisé au-dessus d'un ministère... a foiré

Votre abonnement nous engage.

En vous abonnant, vous soutenez le projet de la rédaction de Marianne : un journalisme libre, ni partisan, ni pactisant, toujours engagé ; un journalisme à la fois critique et force de proposition.

Natacha Polony, directrice de la rédaction de Marianne

Découvrez le numéro de la semaine

Les articles les plus lus

- "À La Poste, on est devenu des vendeurs" : Hervé, 59 ans, facteur, raconte son premier et dernier jour de boulot

- Christophe Guilluy : "À l'Élysée, Emmanuel Macron ne pense qu'à la trace qu'il va laisser dans l'Histoire"

- Pourquoi il fait un temps de merde depuis des mois (et pourquoi c'est un peu une bonne nouvelle)

- Nicolas Ravailhe : "L'Europe a désindustrialisé, pillé et paupérisé la France"

- Natacha Rey, Alain Soral, Zoé Sagan… Ces personnalités à l'origine de l'intox Jean-Michel Trogneux

- Gouvernement

- Union Européenne

- Petites indiscrétions / Grosses révélations

- Laïcité et religions

- Police et Justice

- Alimentation

- Agriculture et ruralité

- Sciences et bioéthique

- Big Brother

- Économie française

- Économie européenne

- Économie internationale

- Protection sociale

- Territoires

- Entreprises

- Consommation

- Proche-Orient

- Géopolitique

- Les signatures de Marianne

- Billets & humeurs

- Tribunes libres

- Les médiologues

- Entretiens et débats

- Littérature

- Cultures pop

- Arts plastiques

- Spectacle vivant

- Du côté des classiques

- Marianne vous remet à niveau

- La fabrique culturelle

- Le goût de la France

- Newsletters

- Archives 2024

- Archives 2023

- Archives 2022

- Archives 2021

- Archives 2020

- Archives 2019

- Archives 2018

- Archives 2017

- Archives 2016

- Archives 2015

- Archives 2014

- Archives 2013

- Archives 2012

- Archives 2011

- Archives 2010

- Archives 2009

- Archives 2008

- Archives 2007

Le magazine

- Déposer vos annonces légales

- Voir nos annonces légales

- Foire aux questions

- Mentions légales

- Données personnelles et cookies

- Gérer mes cookies

- Formulaire de rétractation

- Postuler à un stage

Nos réseaux sociaux

- Side Hustles

- Power Players

- Young Success

- Save and Invest

- Become Debt-Free

- Land the Job

- Closing the Gap

- Science of Success

- Pop Culture and Media

- Psychology and Relationships

- Health and Wellness

- Real Estate

- Most Popular

Related Stories

- Health and Wellness A psychologist shares the 5 exercises she does to 'stop overthinking everything'

- Psychology and Relationships Venting won't help, new study shows—this is the No. 1 way to manage your anger

- Health and Wellness Harvard-trained neuroscientist: 7 tricks I use to remember better

- Success Happiness researcher: The exact blueprint that will help you achieve your biggest career goal

- Life There's a word for obsessive longing—'limerence'—and it can ruin relationships

The surprising benefits of journaling for 15 minutes a day—and 7 prompts to get you started

If you're like most people, you'll only write down what you absolutely need to, like to-do lists, meeting notes and reminders. But writing in your journal as a way to release and express your thoughts, feelings and emotions can be a life-changing habit.

Daily writing can be a challenge if you're new to it. Much like meditating, it requires patience and commitment. But if you stick to it, it can improve your life in significant ways.

The surprising benefits of journaling

1. It can help you clarify your thoughts and feelings

Keeping a journal allows you to track patterns, trends and improvements over time. When current circumstances appear insurmountable, you can look back on previous dilemmas that you have since resolved and learn from them.

You might also encounter moments where you feel confused and uncertain about your feelings. By writing them down, you're able to tap into your internal world and better make sense of things.

Anne Nelson, an acclaimed journalist and author of the forthcoming book, "Shadow Network: Media, Money and the Secret Hub of the Radical Right," says she's often asked whether she suffers when writing on fraught subjects. Her answer is always no.

"What I feel is a deep satisfaction when I get it right," she said. "It's the feeling when I've explained something in writing that I couldn't explain to myself before I started."

2. It can help your injuries heal faster

It may sound a little crazy, but a 2013 study found that 76% of adults who spend 50 to 20 minutes writing about their thoughts and feelings for three consecutive days two weeks before a medically necessary biopsy were fully healed 11 days after. Meanwhile, 58% of the control group had not fully recovered.

"We think writing about distressing events helped participants make sense of the events and reduce distress, thus helping the body to heal faster," Elizabeth Broadbent, professor of medicine at the University of Auckland in New Zealand and co-author of the study, said in an interview with Scientific American .

3. It can improve your problem-solving skills

When you encounter a difficult problem, removing the situation from your mind and putting it down on paper encourages you to look at things from different angles and brainstorm several solutions in a more organized manner.

A classic 1985 study from the School Science and Mathematics Association, for example, found that students who wrote about their math problems in a journal (e.g., describing the problem and writing about how they came up with the answer) had significantly improved test scores over time.

4. It can help you recover from traumatic experiences

There are no rules as to how or what you must write about. Creative writing, such as fiction or poetry, can also be a form of journaling — and it can help you move past traumatic experiences.

Writing creatively allows you to craft a coherent narrative and shifting perspective, according to Jessica Lourey, a tenured writing professor, sociologist and author of 15 books, including "Rewrite Your Life: Discover Your Truth Through the Healing Power of Fiction."

What I feel is a deep satisfaction when I get it right. It's the feeling when I've explained something in writing that I couldn't explain to myself before I started. Anne Nelson Journalist and author

After the loss of her husband, Lourey said she couldn't survive reliving the pain of the tragedy by writing down her thoughts and emotions. "I needed to convert it, package it and ship it off," she wrote in a column for Psychology Today . Rewriting her life to fit a fictional narrative helped her heal faster because it allowed her to become "a spectator to life's roughest seas."

Journalist and novelist Leila Cobo agrees. Writing fiction has helped her so much that it's now become a daily routine. "It allows me to say anything in any way that I wish. It's the most amazing feeling," she said. "I write either early in the morning or late at night. And once I'm in, I'm in."

How to get started

While some can write for hours at a time, researchers say that journaling for at least 15 minutes a day three to five times a week can significantly improve your physical and mental health.

If you're new to journaling, the easiest way to begin is to find a time and place where you won't be disturbed and just start writing. (Don't worry about spelling or grammar; you're writing for yourself and no one else.)

If you don't know what to write about, here are some ideas:

- Write about something (or someone) extremely important to you.

- Write about three things you're grateful for today — and why.

- Write about what advice you'd give to your younger self.

- Write about a current challenge you're struggling with and possible solutions.

- Write about 10 things you wish people knew about you.

- Write about one thing you did this year that you're proud of.

- Write about 10 things you'd say yes to and 10 things you'd say no to.

Deepak Chopra is the co-author of "The Healing Self," founder of The Chopra Foundation and co-founder of Jiyo and The Chopra Center for Wellbeing .

Kabir Sehgal is a New York Times best-selling author. He is a former vice president at JPMorgan Chase, multi-Grammy Award winner and U.S. Navy veteran. Chopra and Sehgal are the co-creators of Home: Where Everyone Is Welcome , inspired by American immigrants.

Like this story? Subscribe to CNBC Make It on YouTube!

Don't miss:

- What do 90-somethings regret most? Here's what I learned about how to live a happy, regret-free life

- 3 science-backed tricks to pull yourself out of a bad mood—in 5 minutes or less

- I took Yale's 'most popular class ever'—and it completely changed how I spend my money

Around 20 minutes of exercise a day may balance out the harms of sitting, study finds

People who have no choice but to sit at a desk for hours on end may have seen, in recent years, a slew of headlines about the scary consequences of sitting for long periods of time — and how even regular exercise couldn’t undo the damage.

Research published Tuesday in the British Journal of Sports Medicine , however, finds that about 22 minutes a day of moderate to vigorous activity may provide an antidote to the ills of prolonged sitting. What’s more, the researchers found that, as a person’s activity level increases, the risk of dying prematurely from any cause goes down.

The study found that the current recommendation of 150 minutes per week of moderate to vigorous activity “is enough to counteract the detrimental health effect of prolonged sitting,” said the study’s lead author, Edvard Sagelv, a researcher at The Arctic University of Norway. “This is the beautiful part: we are talking about activities that make you breathe a little bit heavier, like brisk walking, or gardening or walking up a hill.”

While 150 minutes may seem like a lot, Sagelv broke it down into manageable terms.

“Think of it: only 20 minutes of this a day is enough, meaning, a small stroll of 10 minutes twice a day — like jumping off the bus one stop before your actual destination to work and then when taking the bus back home, jumping off one stop before,” he said in an email.

The new research appears to upend findings from earlier studies showing that regular exercise didn’t zero out the negative effects associated with extended periods of sitting. One of those studies, published in the Annals of Internal Medicine in 2017, found that working out regularly reduced some of the harms associated with hours of sitting, but didn’t completely eliminate them.

In the study, researchers looked at information from nearly 12,000 people ages 50 and older in four datasets from Norway, Sweden and the United States. In those datasets, the participants wore movement detection devices on their hips for 10 hours a day for at least four days. All of the individuals included in the new study were tracked for at least two years.

More on the benefits of exercise

- Morning workouts may be better for weight loss, study finds

- If you're sitting all day, science shows how to undo the health risks: "activity snacks"

- Short bursts of activity , totaling less than 10 minutes, linked to lower risk of death

In the new analysis, the researchers accounted for factors, including medical conditions, that could’ve affected risk of early death.

About half of the participants spent 10 ½ hours or more sedentary each day.

When the researchers linked the participants’ information with death registries in the different countries, they found that over an average of five years, 805 people, or 17%, had died. Of those who died, 357, or 6%, had spent less than 10 ½ hours a day seated, while 448 averaged 10 ½ hours or more sedentary.

Sitting for more than 12 hours a day, the researchers found, was associated with a 38% increased risk of death as compared to eight hours, but only among those who managed to get less than 22 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity a day.

The risk of death went down with increasing amounts of physical activity . An extra 10 minutes a day translated into a 15% lower risk of death among those spending fewer than 10 ½ hours seated and a 35% lower risk among those who spent more than 10 ½ hours sedentary each day.

Lower intensity activity only made a difference among participants who spent 12 or more hours sitting every day.

Sagelv said he believes the new study is more accurate than previous research because he and his colleagues painstakingly adjusted data from the four datasets so that the individuals in them were more comparable to one another and thus their data could be treated as if they were all participating in a single study.

Prolonged sitting is becoming a bigger and bigger problem, said Benjamin Boudreaux, a research scientist in the division of behavioral cardiology at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, who was not involved with the new research.

More activity can easily be incorporated into the schedules of even the busiest people, Boudreaux said.

“I always tell people if they are pressed for time, when you go grocery shopping or running errands, park your car far away in the lot. If you have a meeting with co-workers, do a walking meeting.”

Dr. Howard Weintraub, clinical director of the Center for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease at NYU Langone Heart, said he worries that people will take the wrong message from the study and “think all they need is 22 minutes of activity, that it will make them bulletproof like Kevlar and after that they can plunk down in a chair.”

Instead, he said, “people should look at this and then speak to their physician or trainer about it.”

“Ask what they think about the strategy of 22 minutes of activity a day being an antidote to sitting ,” said Weintraud, who wasn’t involved with the new research.

The good news from this study is that even a minimum amount of activity will help decrease the risk of premature death related to prolonged sitting , said Dr. Joseph Herrera, professor and chair of the department of rehabilitation and human performance at the Mount Sinai Health System in New York City.

“It says that 20 to 25 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity for those who are sedentary — walking briskly, pushing a lawn mower, riding a bicycle at a speed of 10 to 12 miles per hour — can make a difference,” said Herrera, who was not involved with the new study. “It doesn’t mean if you’re already active and exercising you can cut down to 20 minutes, the bare minimum.”

Follow NBC HEALTH on Twitter & Facebook .

Linda Carroll is a regular health contributor to NBC News. She is coauthor of "The Concussion Crisis: Anatomy of a Silent Epidemic" and "Out of the Clouds: The Unlikely Horseman and the Unwanted Colt Who Conquered the Sport of Kings."

- Mental Health/Psychology

Spending Just 20 Minutes in a Park Makes You Happier. Here’s What Else Being Outside Can Do for Your Health

S pending time outdoors, especially in green spaces, is one of the fastest ways to improve your health and happiness. It’s been shown to lower stress, blood pressure and heart rate, while encouraging physical activity and buoying mood and mental health . Some research even suggests that green space is associated with a lower risk of developing psychiatric disorders — all findings that doctors are increasingly taking seriously and relaying to their patients.

Now, a new study published in the International Journal of Environmental Health Research adds to the evidence and shows just how little time it takes to get the benefits of being outside. Spending just 20 minutes in a park — even if you don’t exercise while you’re there — is enough to improve well-being, according to the research.

For the study, researchers surveyed 94 adults who visited one of three urban parks near Birmingham over the summer and fall. They were given fitness trackers to measure physical activity but were not told what to do in the park or how long to stay. Each person also answered questions about their life satisfaction and mood — which were used to calculate a subjective well-being score, with a maximum value of 55 — before and after their park visit.

The average park visit lasted 32 minutes, and 30% of people engaged in at least moderate-intensity physical activity while there. Well-being scores rose during the park visit in 60% of people, with an average increase of about 1.5 points (from about 37 to 39).

Physical activity was not necessary to increase well-being, the study authors found, even though plenty of research suggests that exercise is great for mental health , particularly when it’s done outside . For many people in the study, simply being in green space seemed to be enough to spark a change, says study co-author Hon Yuen, director of research in the occupational therapy department at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“Some people may go to the park and just enjoy nature. It’s not that they have to be rigorous in terms of exercise,” Yuen says. “You relax and reduce stress, and then you feel more happy.”

The medical community is increasingly viewing green space as a place for their patients to reap physical and mental health benefits. Some physicians, like Dr. Robert Zarr, a pediatrician in Washington, D.C., are even writing prescriptions for it.

These “nature prescriptions” — therapies that are redeemable only outdoors, in the fresh air of a local park — advise patients to spend an hour each week playing tennis, for instance, or to explore all the soccer fields near their home. The scripts are recorded in his patients’ electronic health records.

“There’s a paradigm shift in the way we think about parks: not just as a place to recreate, but literally as a prescription, a place to improve your health,” says Zarr, who writes up to 10 park prescriptions per day. In 2017 he founded Park Rx America to make it easier for health professionals to write park prescriptions for people of all ages, particularly those with obesity, mental-health issues or chronic conditions like hypertension and Type 2 diabetes .

By writing nature prescriptions — alongside pharmaceutical prescriptions, when necessary — physicians are encouraging their patients to get outdoors and take advantage of what many view to be free medicine. The specificity that comes with framing these recommendations as prescriptions, Zarr says, motivates his patients to actually do them. “It’s something to look forward to and to try to feel successful about,” he says.

In 2018, NHS Shetland, a government-run hospital system in Scotland, began allowing doctors at 10 medical practices to write nature prescriptions that promote outdoor activities as a routine part of patient care. And in recent years, organizations with the goal of getting people outside for their health have proliferated in the U.S. The National Park Service’s Healthy Parks Healthy People program promotes parks as a “powerful health prevention strategy” locally and nationally. Walk With a Doc , which sponsors free physician-led community walks, is now in 47 states, and Park Rx , which has studied and tracked park-prescription programs since 2013, says these are now in at least 33 states and Washington, D.C. Even mental-health professionals are going green. A growing number of “ecotherapy” counselors conduct sessions outdoors to combine the benefits of therapy and nature.

Plus, these unusual prescriptions are the prettiest you’ll ever fill — a fact that Betty Sun, program manager at the Institute at the Golden Gate, which runs Park Rx, says encourages people to actually do them. “With social media and Instagram, when you see your friends going out to beautiful places, you want to go too,” Sun says. “It’s about making a positive choice in your life, rather than a punitive choice — like ‘You’re sick, take a pill.’ It just seems so much more supportive.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Passengers Are Flying up to 30 Hours to See Four Minutes of the Eclipse

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Essay: The Complicated Dread of Early Spring

- Why Walking Isn’t Enough When It Comes to Exercise

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Jamie Ducharme at [email protected]

You May Also Like

Expert Consult

Journal Club: How to Build One and Why

By Michelle Sharp, MD; Hunter Young, MD, MHS

Published April 6, 2022

Journal clubs are a longstanding tradition in residency training, dating back to William Osler in 1875. The original goal of the journal club in Osler’s day was to share expensive texts and to review literature as a group. Over time, the goals of journal clubs have evolved to include discussion and review of current literature and development of skills for evaluating medical literature. The ultimate goal of a journal club is to improve patient care by incorporating evidence into practice.

Why are journal clubs important?

In 2004, Alper et al . reported that it would take more than 600 hours per month to stay current with the medical literature. That leaves residents with less than 5 hours a day to eat, sleep, and care for patients if they want to stay current, and it’s simply impossible. Journal clubs offer the opportunity for residents to review the literature and stay current. Furthermore, Lee et al . showed that journal clubs improve residents’ critical appraisal of the literature.

How do you get started?

The first step to starting a journal club is to decide on the initial goal. A good initial goal is to lay the foundation for critical thinking skills using literature that is interesting to residents. An introductory lecture series or primer on study design is a valuable way to start the journal club experience. The goal of the primer is not for each resident to become a statistician, but rather to lay the foundation for understanding basic study designs and the strengths and weaknesses of each design.

The next step is to decide on the time, frequency, and duration of the journal club. This depends on the size of your residency program and leadership support. Our journal club at Johns Hopkins is scheduled monthly during the lunch hour instead of a noon conference lecture. It is essential to pick a time when most residents in your program will be available to attend and a frequency that is sustainable.

How do you get residents to come?

Generally, if you feed them, they will come. In a cross-sectional analysis of journal clubs in U.S. internal medicine residencies, Sidorov found that providing food was associated with long-lasting journal clubs. Factors associated with higher resident attendance were fewer house staff, mandatory attendance, formal teaching, and an independent journal club (separate from faculty journal clubs).

The design or format of your journal club is also a key factor for attendance. Not all residents will have time during each rotation to read the assigned article, but you want to encourage these residents to attend nonetheless. One way to engage all residents is to assign one or two residents to lead each journal club, with the goal of assigning every resident at least one journal club during the year. If possible, pick residents who are on lighter rotations, so they have more time outside of clinical duties to dissect the article. To enhance engagement, allow the assigned residents to pick an article on a topic that they find interesting.

Faculty leadership should collaborate with residents on article selection and dissection and preparation of the presentation. Start each journal club with a 10- to 20-minute presentation by the assigned residents to describe the article (as detailed below) to help residents who did not have time to read the article to participate.

What are the nuts and bolts of a journal club?

To prepare a successful journal club presentation, it helps for the structure of the presentation to mirror the structure of the article as follows:

Background: Start by briefly describing the background of the study, prior literature, and the question the paper was intended to address.

Methods: Review the paper’s methods, emphasizing the study design, analysis, and other key points that address the validity and generalizability of the results (e.g., participant selection, treatment of potential confounders, and other issues that are specific to each study design).

Results: Discuss the results, focusing on the paper’s tables and figures.

Discussion: Restate the research question, summarize the key findings, and focus on factors that can affect the validity of the findings. What are potential biases, confounders, and other issues that affect the validity or generalizability of the findings to clinical practice? The study results should also be discussed in the context of prior literature and current clinical practice. Addressing the questions that remain unanswered and potential next steps can also be useful.

Faculty participation: At our institution, the faculty sponsor meets with the assigned residents to address their questions about the paper and guide the development of the presentation, ensuring that the key points are addressed. Faculty sponsors also attend the journal club to answer questions, emphasize key elements of the paper, and facilitate the open discussion after the resident’s presentation.

How do you measure impact?

One way to evaluate your journal club is to assess the evidence-based practice skills of the residents before and after the implementation of the journal club with a tool such as the Berlin questionnaire — a validated 15-question survey that assesses evidence-based practice skills. You can also conduct a resident satisfaction survey to evaluate the residents’ perception of the implementation of the journal club and areas for improvement. Finally, you can develop a rubric for evaluation of the resident presenters in each journal club session, and allow faculty to provide feedback on critical assessment of the literature and presentation skills.

Journal clubs are a great tradition in medical training and continue to be a valued educational resource. Set your goal. Consider starting with a primer on study design. Engage and empower residents to be part of the journal club. Enlist faculty involvement for guidance and mentorship. Measure the impact.

- Methodology

- Open access

- Published: 12 February 2022

Operationalising the 20-minute neighbourhood

- Lukar E. Thornton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8759-8671 1 , 2 ,

- Ralf-Dieter Schroers 2 , 3 ,

- Karen E. Lamb 2 , 4 ,

- Mark Daniel 3 , 5 ,

- Kylie Ball 2 ,

- Basile Chaix 6 ,

- Yan Kestens 7 , 8 ,

- Keren Best 2 ,

- Laura Oostenbach 2 &

- Neil T. Coffee 3

International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity volume 19 , Article number: 15 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

31 Citations

19 Altmetric

Metrics details

Recent rapid growth in urban areas and the desire to create liveable neighbourhoods has brought about a renewed interest in planning for compact cities, with concepts like the 20-minute neighbourhood (20MN) becoming more popular. A 20MN broadly reflects a neighbourhood that allows residents to meet their daily (non-work) needs within a short, non-motorised, trip from home. The 20MN concept underpins the key planning strategy of Australia’s second largest city, Melbourne, however the 20MN definition has not been operationalised. This study aimed to develop and operationalise a practical definition of the 20MN and apply this to two Australian state capital cities: Melbourne (Victoria) and Adelaide (South Australia).

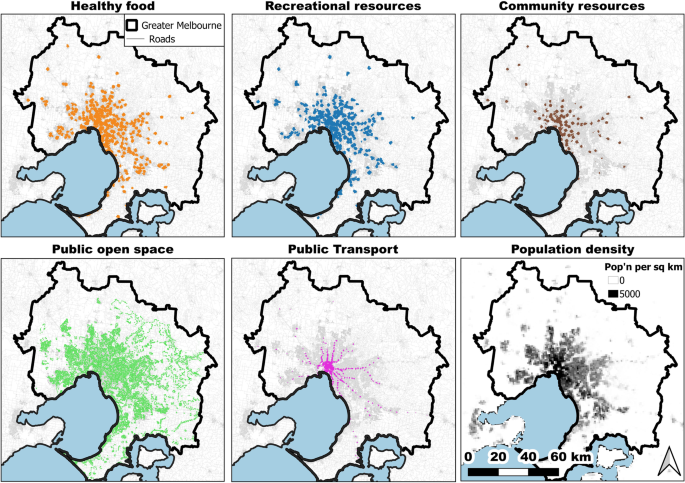

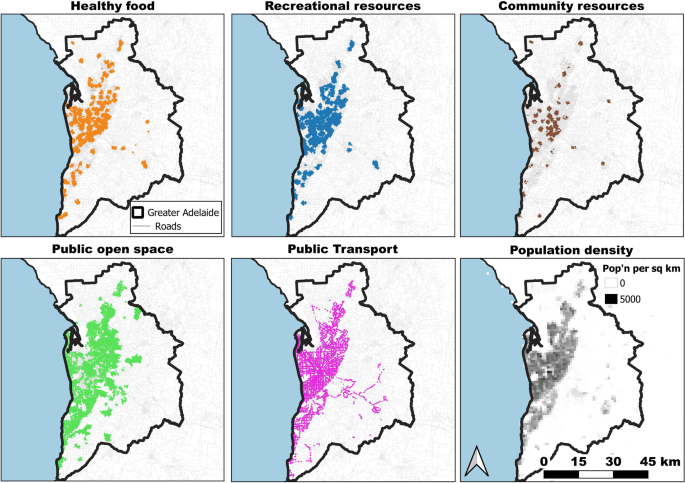

Using the metropolitan boundaries for Melbourne and Adelaide, data were sourced for several layers related to five domains: 1) healthy food; 2) recreational resources; 3) community resources; 4) public open space; and 5) public transport. The number of layers and the access measures required for each domain differed. For example, the recreational resources domain only required a sport and fitness centre (gym) within a 1.5-km network path distance, whereas the public open space domain required a public open space within a 400-m distance along a pedestrian network and 8 ha of public open space area within a 1-km radius. Locations that met the access requirements for each of the five domains were defined as 20MNs.

In Melbourne 5.5% and in Adelaide 7.6% of the population were considered to reside in a 20MN. Within areas classified as residential, the median number of people per square kilometre with a 20MN in Melbourne was 6429 and the median number of dwellings per square kilometre was 3211. In Adelaide’s 20MNs, both population density (3062) and dwelling density (1440) were lower than in Melbourne.

Conclusions

The challenge of operationalising a practical definition of the 20MN has been addressed by this study and applied to two Australian cities. The approach can be adapted to other contexts as a first step to assessing the presence of existing 20MNs and monitoring further implementation of this concept.

Estimates suggest that in 2018, 4.2 billion people (55% of the world population) lived in cities and by 2050, 68% of the world’s population will live in urbanised areas [ 1 ]. Australia is witnessing a rapid population increase in its major cities [ 2 ]. Seventy-five percent of Australia’s population growth over the last 20 years occurred in state capital cities [ 2 , 3 ] and further significant population growth is forecast [ 4 ].

The global transition to urban living has occurred concomitant with increases in obesity and chronic diseases related to inappropriate diet and physical inactivity [ 5 , 6 ]. Understanding how urbanisation and urban design inhibit, or alternately, promote healthful lifestyles, is essential to preventing obesity and chronic disease [ 7 , 8 ]. Creating liveable urban environments that facilitate improved population health presents challenges and opportunities for governments, planners, and policy-makers responsible for employment, transport, housing, the environment, community engagement, urban sprawl, education and health [ 3 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ], all of which are key indicators of liveability [ 12 , 13 ].

Compact city policies seek to ensure residents have access to important everyday amenities and services without travelling far from home and without resorting to motorised transport. In theory, neighbourhoods with a wide range of local amenities, services, and transport infrastructure, should encourage greater local interaction and support more healthful choices.

International adoption of compact city strategies

Many Asian cities are designed in a way that reflects compact cities and consequently this results in local and, especially, vertical living [ 14 , 15 ]. Portland, USA, initially promoted their compact city concept within the framework of a “20-minute neighbourhood” (20MN) [ 16 , 17 ]. A 20MN was defined as “a place with convenient, safe, and pedestrian-oriented access to the places people need to go to and the services people use nearly every day: transit, shopping, healthy food, school, parks, and social activities” (p.4, [ 16 ]) and noted that the 20MN term “is not intended to convey a specific metric ” (p.4 [ 16 ]). Recently, cities such as Paris, France [ 18 ], Edinburgh, UK [ 19 ], Seattle, USA [ 20 ], and the Flanders region of Belgium [ 21 ] have put forward similar concepts. In England, an emphasis is being placed on creating 20MNs with benefits stated to extend to the economy, environment, health, as well as social benefits such as safety and inclusiveness [ 22 ].

What is happening in Melbourne?

Increasingly, Australian city planners are examining opportunities to create compact localised environments [ 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ]. In Melbourne, Australia’s second largest city, the most recent planning strategy, Plan Melbourne, proposed an agenda to manage urban growth and meet Melbourne’s future environmental, population, housing and employment needs [ 26 ]. A key component underpinning Plan Melbourne was the promotion of 20MNs that allowed people to access amenities and services near their home promoting and enabling healthful local living [ 24 , 26 ].

Table 1 presents an overview of the four key policy documents relating to Melbourne’s 20MN strategy with iterations published in 2014, 2015, 2017 and 2019. This table identifies how key aspects of the Melbourne 20MN have evolved and changed over this timeframe. When the 20MN concept was first introduced in the 2014 Plan Melbourne planning strategy, it ambitiously stated that “20-minute neighbourhoods are places where you have access to local shops, schools, parks, jobs and a range of community services within a 20-minute trip from your front door” [ 27 ] (page numbers for the quoted text throughout are provided in Table 1 ). The most recent version (2019) states “The 20-minute neighbourhood is all about ‘living locally’ – giving people the ability to meet most of their daily needs within a 20-minute walk from home, with access to safe cycling and local transport options” [ 24 ].

Apart from employment opportunities, amenities and services considered as constituting everyday needs have remained relatively stable across the various iterations of Plan Melbourne (Table 1 ). These have included amenities and services related to retail (with specific reference among others to food retail such as small supermarkets and cafés), education, open space, sports facilities, community services, health services, and public transport. Access to safe and well-connected pedestrian and cycling infrastructure has also been a common element.

Less consistent in Plan Melbourne has been the definition of what constitutes 20 minutes from the perspective of travel mode and what distance this equates to. Originally in 2014, this was posed as “within 20 minutes of where they live, travelling by foot, bicycle or public transport” [ 27 ], while the 2015 version refined this to “primarily within a 20-minute walk” with an estimated distance of 1 to 1.5 km [ 25 ]. The updated strategy that followed in 2017 stated “within a 20-minute journey from home by walking, cycling, riding or local public transport” [ 26 ], although it was unclear what “riding” referred to given “cycling” preceded it separately. It is perhaps not surprising that the 2019 update refined this once again to just include walking and this time acknowledged the benefit of access to other modes using the following statement: “ within a 20-minute walk from home with access to safe cycling and local transport options” [ 24 ]. Importantly, it is stated that “this 20-minute journey represents an 800m walk from home to a destination, and back again” [ 24 ]. Two interesting points are of note here. First, instead of features being within 20 minutes, the wording is suggestive that these are now effectively within 10 minutes from home factoring in a return journey. The second point of interest is the emphasis on walking noting that “while cycling and local transport provide people with alternative active travel options to walking, these modes do not extend neighbourhoods, or access to 20-minute neighbourhood features beyond walkable catchments of 800m” [ 24 ].

Problem statement and objective

Without a clear conceptualisation and operationalisation of a 20MN, it is impossible to properly implement a 20MN, much less evaluate the benefits. This study sought to develop and operationalise a practical definition of the 20MN concept. The method proposed can be utilised elsewhere and modified by adding/removing spatial data layers that represent amenities and services and altering the measures of access (e.g., by distance and mode of travel) assuming each decision rule is rationalised. Flexibility in allowing the approach to be tailored ensures it can remain relevant to different populations, contexts, and policy environments.

With the intense policy focus on 20MNs in Melbourne (state capital of Victoria, Australia), we chose this city as the basis for our 20MN measure. To demonstrate how the measure could be tailored and applied to a different setting, the Australian city of Adelaide (state capital of South Australia) was chosen for comparison purposes. Both the Victorian [ 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ] and South Australian [ 29 ] state governments have neighbourhood design and urban renewal policies yet the two state capitals themselves differ substantially in terms of population, urban sprawl, and transportation infrastructure. The 30 Year Plan for Greater Adelaide [ 29 ], while not explicitly invoking the 20MN, refers to transit-oriented developments that support walkable and connected communities .

Spatial extent

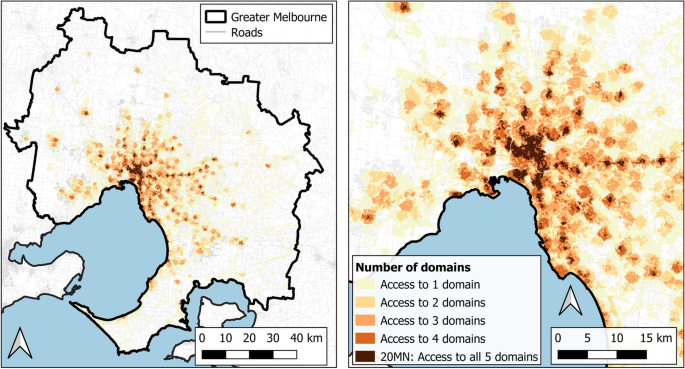

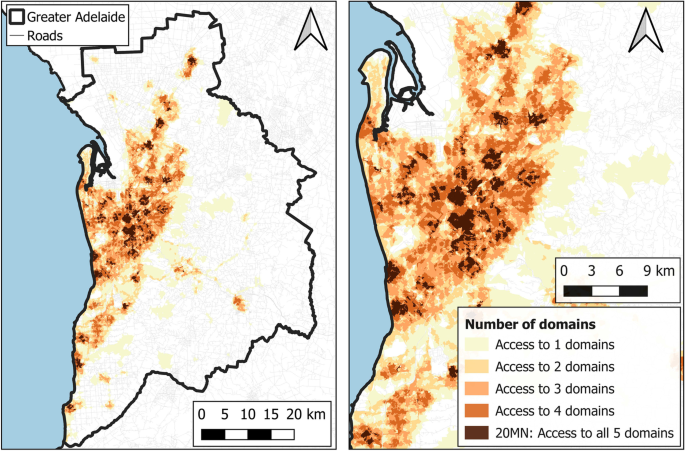

The spatial extent of the metropolitan Melbourne and Adelaide regions is represented by the 2016 Australian Bureau of Statistics Greater Capital City Statistical Areas [ 36 ] (Fig. 1 , Melbourne, and Fig. 2 , Adelaide). The Greater Capital City Statistical Areas represent the functional extent of the Australian State and Territory capital cities, capturing most of the commuting population and the labour markets of each capital city. They are not a marker of the edge of the city, but instead include the population who regularly socialise, shop, or work within the city, and include small towns and rural areas surrounding the urban core of the city.

Areas in Melbourne with access to the healthy food, recreational resources, community resources, public open space, and public transport domains and a population density layer depicted by population density grid [ 37 ]

Areas in Adelaide with access to the healthy food, recreational resources, community resources, public open space, and public transport domains and a population density layer depicted by population density grid [ 37 ]

Defining the attributes of the 20-minute neighbourhood

Drawing on Plan Melbourne’s various definitions of the 20MN [ 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ], the Portland Plan [ 16 , 17 ], literature related to urban liveability indices (e.g. [ 8 , 11 , 12 ]), and our collective knowledge of this field, we proposed five spatial data domains required for a 20MN: 1) healthy food; 2) recreational resources; 3) community resources; 4) public open space; and 5) public transport. Further details of the attributes used and the inclusion rationale for each are outlined in Table 2 and in the text below.

Defining the pedestrian network layer

A pedestrian network layer was created for each city which allowed for the calculation of pedestrian network distances. A pedestrian network distance differs from a road network distance by including paths that vehicles cannot use (e.g. pedestrian alleyways that link two streets) and excluding network paths accessible to cars but not pedestrians (e.g. freeways) [ 43 ]. Vehicle based one-way restrictions on streets were also removed to allow pedestrian movement in either direction, whilst tunnels and overpasses were included in the network model so as to distinguish them from crossroad intersections. For Melbourne, VicMap Transport data were used to create this layer and, in Adelaide, Statewide Road Network data.

Data sources

Data were sourced from a combination of government and commercial sources either publicly available or accessible upon request. Some datasets were available at a national level, meaning the same data sources could be used for both Melbourne and Adelaide (e.g., general practitioners (GPs) and pharmacies), whilst others were state or city specific (e.g., public open space). For full data source details see Additional File 1 .

A further comment on our featuring of both a primary city (Melbourne) and a comparison city (Adelaide) is that a great deal of spatial data representing natural and built environments in Australia is based at a state or even at more local levels rather than being available nationally in a consistent format. Thus, the use of a comparison city provides an opportunity to test the applicability of our 20MN concept in a different context where the data sources vary, further demonstrating the generalisability of the approach.

Defining accessibility for each layer

All layers were processed using ArcGIS v10.5 [ 44 ] and access to each was defined as per Table 2 . For most measures, a pedestrian network service area at a specified distance was created using the feature as the starting point noting that there were no one-way restrictions within our network layer. Address points within this service area were therefore considered to have access to this feature. For most features, a 1.5-km distance was used and is consistent with common definitions used in walkability studies which equate a 5-minute walk to 400 m [ 45 ]. For public transport, accessibility measures were informed by the literature and altered based on published estimates of usual distances that people walk to different transport modes [ 39 , 40 , 41 ].

The access measure used for open space considered both access to public open space within a 400-m network distance and at least 8 ha of public open space area within a 1-km radius. These access metrics were consistent with the Melbourne planning guideline recommendations for open space (see Table 2 ). The comprehensive Victorian Planning Authority Metropolitan Open Space Network walkable catchment layer [ 38 ] was used to determine if households were located within 400 m of open space in Melbourne with open space access points within this dataset specified by the provider at 30-m intervals. For Adelaide, data were sourced from a previous study [ 46 ] and 400-m pedestrian network service areas were created along park border points (50-m spacing). In both cities, the selected open space features outlined in Table 2 were rasterised to a 10-m × 10-m grid (cell defined as open space: 0 = no; 1 = yes). A count of open space cells within a 1-km radius (circular radius using focal statistics) around each individual cell was undertaken. A minimum count of 800 cells classified as open space was required to represent access to at least 8-ha open-space area within a 1-km radius. The method resulted in a continuous surface (10-m grid) representation of open space access across both Melbourne and Adelaide. This approach avoids some of the complex issues associated with measuring open space access [ 47 ].

Combining layers to create domains

As detailed in Table 2 , for each of the five 20MN domains (healthy food, recreational resources, community resources, public open space, public transport), several criteria had to be met for households to be defined as having access to this domain, with the exception of the recreational resources domain, which required access to a gym only. The healthy food domain required access to either a large supermarket or both a smaller supermarket and a greengrocer (greengrocers defined as fruit and vegetable stores). The community resources domain required access to each of the six layers (i.e., primary school, general practitioner, pharmacy, library, post office, and café). The public open space domain required access to public open space within 400 m and at least 8 ha of open space within 1 km. Finally, the public transport domain in Melbourne required access to any public transport mode for households located within a 5-km radius of the city centre (defined by the location of the General Post Office) or access to a train station and either a bus or tram for those beyond 5 km (see Table 2 for rationale). In Adelaide, the public transport domain required access to any of the three specified modes of transport.

Using the community resources domain as an example, determining if access to the domain criteria had been met involved overlaying the services areas of the six individual layers and extracting the intersection of the six layers. The spatial distribution of areas considered to meet the access criteria for each domain is presented in Fig. 1 for Melbourne and Fig. 2 for Adelaide.

Creating the final 20MN layer

Once the five domains were generated, they were overlayed, and the count of intersecting areas calculated (Fig. 3 ). Areas where all five domains intersected were considered as consistent with the 20MN concept as they met the access criteria for each domain (healthy food, recreational resources, community resources, public open space, and public transport). This approach allows features to be dispersed in different directions around address points rather than clustered in a single activity centre.

Intersecting areas of domain access

Areas with access to each of the five domains and therefore a 20MN are represented in Fig. 4 for Melbourne and Fig. 5 for Adelaide. As expected, more areas considered to be 20MNs were clustered nearer to the city centres whilst in Melbourne there was also a noticeable pattern of areas with 20MNs appearing around the train stations in the mid and outer suburbs. Figures 4 and 5 also show the intensity of domain access across the two cities.

Count of domain access within Greater Melbourne (left) and the inner-mid Melbourne region (right)

Count of domain access within Greater Adelaide (left) and the inner-mid Adelaide region (right)

Population and dwelling density by level of domain access

Population and dwelling counts were determined using data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2016 census mesh block (the smallest geographical area defined by the ABS [ 48 ]). Mesh block centroids were used to determine how many domains that mesh block had access to. The ABS assign the dominant land use to each mesh block (e.g., residential, commercial, primary production, parkland). Over 95% of the population in both cities reside within mesh blocks categorised as residential. The total population with access to each domain was extracted (Table 3 ) in addition to the population density and dwelling densities of residential mesh blocks by the count of domains the mesh block had access to (Table 4 ).

When examining domains individually, over 50% of the population in each city met the access criteria for the healthy food domain whilst over 70% had access to open space (Table 3 ). In Melbourne, 45% met the access criteria for the recreational resources domain compared to 56% in Adelaide. The percentage meeting the access criteria for the community resources layer was much lower in both cities (20% Melbourne; 18% Adelaide) as this domain required access to six separate layers. The main difference between cities was in the percentage of the population meeting the access criteria for the public transport domain. This was to be expected given the different access criteria applied in the two cities (i.e., those further than 5 km from the General Post Office in Melbourne required access to a train station) with just 13% of the Melbourne population meeting the requirements of this domain compared to 64% in Adelaide.

Most of the Melbourne population (66%) had access to two or fewer domains compared to 45% in Adelaide which again likely reflects the differences in the public transport access criteria. In Melbourne, 5.5% of the population met the access criteria for each of the five domains and therefore were considered to have a 20MN. In Adelaide, this percentage was slightly higher at 7.6%.

Noticeably, there was a trend in the population density and dwelling density results with the lowest median density in areas without access to any of the domains and the highest median density in areas with access to all five domains (Table 4 ). The median number of people per square kilometre with access to all five domains (a 20MN) was 6429 in Melbourne and 3062 in Adelaide. The median number of dwellings per square kilometre with access to all five domains was also higher in Melbourne (3211) compared to Adelaide (1440).

The 20MN continues to be promoted as having many projected benefits [ 22 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 49 , 50 ]. However, without defining and operationalising the 20MN, it remains difficult to implement a 20MN, monitor the progress of 20MN initiatives, and quantify the benefits. There are various ways that a 20MN could be expressed differently to what is proposed here including, for example, the addition of further attributes deemed important for everyday living, altering the modes of travel and the corresponding distance of a 20-minute trip, and allowing for more refined gradations of access to attributes. We have presented the first steps to flexibly operationalise the 20MN concept without resorting to the typical approach of using predefined administrative units. This ensures access can be determined from individual address points. This is an advance over existing liveability indicators that utilise predefined administrative units that measure access to various attributes according to their presence, number, and distance from some referent (e.g. within the boundaries of the unit or the distance from the geographic centroid) [ 51 , 52 ]. We view pre-defined administrative units that specify arbitrary boundaries (e.g., statistical area 1, census tract) as having little, if any, inherently meaningful correspondence to a resident’s lived environment [ 53 ].

In support of our methodology, we examined variations in how the 20MN concept has been presented across various iterations of Melbourne’s planning strategies [ 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ] (Table 1 ) but also internationally [ 16 , 17 , 19 , 22 ]. We concede the attributes and access definition can, and should, be debated and that no single prescriptive definition may suit all contexts. Yet, the simplistic definition conveyed in policy documents falls short of specifying which amenities and services should be located within 20-minutes. This lack of specificity prevents a clear capacity to evaluate targeted interventions to increase 20MNs in urban areas.

The attributes that we selected represent a broad range of everyday services and amenities that may be considered to promote environmental, social, economic and health benefits across various demographic groups. In defining these attributes, we note three issues. First, access to an attribute is defined by the presence of a single attribute within the specified distance rather than the concentration of that attribute, with the partial exception of open space where a minimum concentration of 8 ha was required. Second, the selection of attributes did not consider those that might be harmful for environmental, social, or health reasons (e.g., fast food chains, presence of major thoroughfares leading to greater traffic, congestion, and pollution) and thus we did not exclude areas where harmful features were co-located with the selected layers. Third, in the case of recreational resources, our measure was limited to gyms including municipal-run facilities that are sometimes termed leisure centres and are available to non-members. In the Australian context, gyms operate all year round and it is not unusual for gyms (especially municipal-run gyms) to include facilities such as swimming pools and classes for activities such as yoga, in addition to weights and cardio equipment. Gyms also cater to people of all levels of fitness and abilities. We avoided sport specific facilities such as tennis courts due to the more limited general appeal. Whilst the availability of gyms provides the opportunity for people to use them, we acknowledge we did not differentiate between municipal-run and commercially-operated gyms, with the latter restricted to members and thus only accessible to those that can afford the membership fees. A key benefit of our overall approach is that each of the domains can be modified through the addition or removal of attributes. They can also be tailored, such that there may be multiple ways to meet the domain criteria. For example, for the healthy food domain, access could be obtained from having access to either a large supermarket or a smaller supermarket and greengrocer whilst in Melbourne, we altered the public transport criteria for those further from the city.