- Biodiversity

- Cities & society

- Land & water

- All research news

- All research topics

- Learning experiences

- Programs & partnerships

- All school news

- All school news topics

- In the media

- For journalists

The science behind the West Coast fires

A collection of research and insights from Stanford experts on wildfires' links to climate change, the health impacts of smoke, and promising strategies for preventing huge blazes and mitigating risks.

Wildfires torched more than five million acres in California, Oregon and Washington in 2020. They killed dozens of people, prompted evacuation orders for hundreds of thousands more and spewed enough toxin-laden smoke to make air conditions hazardous for millions.

In 2021, wildfires in California alone burned more than 1.7 million acres before the end of August, destroying thousands of structures and forcing mass evacuations.

Tendrils of smoke from fires in the western United States have drifted as far as Europe. As environmental economist Marshall Burke put it in a virtual panel discussion hosted in September 2020 by Stanford’s Woods Institute for the Environment , “This is not just a U.S. West Coast issue, this is a nationwide issue.”

As the fires burn, they are unlocking huge amounts of carbon dioxide from soils and plants and launching it into the atmosphere.

Six of the seven largest fires on the modern record in California ignited in 2020 or 2021, and most of the largest fires in the state’s history have occurred in the past two decades. Scientists say global warming and decades of fire suppression have helped lay the groundwork for the devastating blazes. One study by Stanford researchers estimated as much as 20 million acres in California would benefit from vegetation thinning or prescribed burns. Another found that the risk of extreme wildfire conditions during autumn has more than doubled across California over the past four decades, and human-caused global warming has made the changes more likely.

This collection covers how scientists are unraveling the factors that contribute to wildfire risk, understanding their impacts and developing solutions. Scroll down for wildfire research news and insights related to climate change , health impacts , prevention and mitigation , prediction and modeling and more.

Last updated: August 31, 2021

Climate change

Back to top

Longer, more extreme fire seasons

A study led by Stanford scientists shows autumn days with extreme fire weather have more than doubled in California since the early 1980s due to climate change.

What to expect from future wildfire seasons

The new normal for Western wildfires is abnormal, with increasingly bigger and more destructive blazes.

Wildfire weather

Stanford climate and wildfire experts discuss extreme weather’s role in current and future wildfires, as well as ways to combat the trend toward bigger, more intense conflagrations.

Climate change has its ‘thumb on the scale’ of extreme fire

“Humans are ingenious at managing climate risk, but our systems are built around the historical climate,” climate scientist Noah Diffenbaugh told The Washington Post . “Systems that were built for the old climate are being stressed in a new way.”

(Image credit: Sheila Sund / Flickr )

Shifting biomes

“In a changing climate it’s not just about continuing to manage the risk of ignition. We also need to recognize that we are dealing with biome shifts that will occur through time," said Chris Field, director of Stanford's Woods Institute for the Environment . Read more in the National Geographic article, " How much are beetles to blame for the 2020 fires? "

Wildfire emissions

“The forests are alive. They’re growing and dying and regrowing,” says Michael Wara, director of the climate and energy policy program at the Woods Institute for the Environment. “That’s really different than carbon that was buried 50 million years ago under the earth that we are unearthing and burning. I think it’s not helpful to compare the two. It’s a misdirection.”

Wildfire smoke worse for kids' health than smoke from controlled burns

Immune markers and pollutant levels in the blood indicate wildfire smoke may be more harmful to children’s health than smoke from a controlled burn.

California wildfires bring questions about health and climate

What does smoke inhalation do to my health? What’s the evidence that these are caused by climate change? Here is how some Stanford experts answer and continue to tackle these complex concerns.

Wildfires' health impacts

California’s massive wildfires bring a host of health concerns for vulnerable populations, firefighters and others. Kari Nadeau and Mary Prunicki of Stanford’s Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research discuss related threats, preparedness and ongoing research.

Mask confusion

"Only certain masks are effective during wildfires, while a range of face coverings may help prevent coronavirus transmission," Stanford researchers write in Environmental Research Letters . Drawing on human behavior studies and past responses to epidemics and wildfire smoke, the scientists recommend ways to communicate mask-use guidance more effectively.

An unexpectedly huge toll on America's lungs

As wildfires become more frequent due to climate change, the increasing amounts of smoke may harm Americans nearly as much as rising temperatures, according to a working paper by Stanford environmental economist Marshall Burke and colleagues. “We hadn’t even thought of that as a key part of the climate impact in this country,” Burke told Bloomberg .

Wildfire smoke is poisoning California's kids. Some pay a higher price.

Marshall Burke, an economist at Stanford, has found that, across California, as the number of smoke days has risen over the past 15 years, it has begun to reverse some of the gains that the state had made in cleaning up its air from conventional sources of pollution.

The shifting burden of wildfires in the United States

Wildfire smoke will be one of the most widely felt health impacts of climate change throughout the country, but U.S. clean air regulations are not equipped to deal with it. Stanford experts discuss the causes and impacts of wildfire activity and its rapid acceleration in the American West.

Tips to protect against wildfire smoke

Warnings of another severe wildfire season abound, as do efforts to reduce the risk of ignition. Yet few are taking precautions against the smoke. Stanford experts advise on contending with hazardous air quality.

Wildfire smoke can increase hazardous toxic metals in air, study finds

Smoke from wildfires – particularly those that burn manmade structures – can significantly increase the amount of hazardous toxic metals present in the air, sending up plumes that can travel for miles, a new study from the California Air Resources Board has suggested. "No one is protected," said Mary Prunicki of Stanford’s Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research.

How do people respond to wildfire smoke?

Interviews with Northern California residents reveal that social norms and social support are essential for understanding protective health behaviors during wildfire smoke events – information that could be leveraged to improve public health outcomes.

Wildfire smoke exposure during pregnancy increases preterm birth risk

Smoke from wildfires may have contributed to thousands of additional premature births in California between 2007 and 2012. The findings underscore the value of reducing the risk of big, extreme wildfires and suggest pregnant people should avoid very smoky air.

Prevention and mitigation

Setting fires to avoid fires.

Analysis by Stanford researchers suggests California needs fuel treatments – whether prescribed burns or vegetation thinning – on about 20 million acres or nearly 20 percent of the state’s land area.

A new treatment to prevent wildfires

Scientists and engineers worked with state and local agencies to develop and test a long-lasting, environmentally benign fire-retarding material. If used on high-risk areas, the treatment could dramatically cut the number of fires that occur each year.

Wildfire preparedness

Experts with Stanford's Woods Institute for the Environment discuss strategies for managing wildfire risks, including incentive structures, regulations, partnerships and financing.

Mitigating risks with law and environmental policy

"In talking about risks and policy prescriptions, we need to separate out wildfires at the wildland-urban interface – those that put people and communities at most risk – from fires that historically have burned through our remote forestlands," said Deborah Sivas , Director of Stanford’s Environmental Law Clinic.

Concrete steps California can take to prevent massive fire devastation

"Successful wildfire preparedness begins with a clear strategy and accountability for outcomes," writes Michael Wara, director of the Climate and Energy Policy Program at Stanford's Woods Institute for the Environment.

Are forest managers robbing the future to pay for present-day fires?

"As fires burn with greater magnitude and frequency, the cost of fighting them is increasingly borne by money earmarked for prevention," writes Bill Lane Center for the American West writer in residence Felicity Barringer.

Policy brief

Managing the growing cost of wildfire.

Stanford experts review recent trends in wildfire activity, quantify how the smoke from these wildfires is affecting air quality and health across the U.S. and discuss what policymakers can do to help reduce wildfire risk.

California burning

Heat waves that could melt the fat in uncooked meat until it would “run away in spontaneous gravy.” Forests that turned abruptly into “great sheets of flame.” These are some of the realities of life in California noted by the botanist William Brewer in 1860, and surfaced in an essay for The New Yorker by Stanford Classics professor Ian Morris about being evacuated from his home in the Santa Cruz mountains.

According to Morris, "Before Europeans came, Native Californians had found ways to cope with this reality. Many moved seasonally, partly to avoid forest fires. As much as one-sixth of the state was deliberately burned each year." Not many people lived in places like the Santa Cruz Mountains until the 1870s. Since then, Morris wrote, the "quiet migration of hundreds of thousands of nature lovers has created one of the most unnatural landscapes on Earth."

Preparing together

"We need programs that emphasize and support herd immunity from fires," Rebecca Miller, a PhD student in the Emmet Interdisciplinary Program in Environment and Resources, told Mic . Rebuilding efforts after a fire, she added, ought to recognize that once-burned neighborhoods are likely to burn again.

Fire burned the Coffey Park neighborhood of Santa Rosa, Calif. in October 2017. (Image credit: Sgt. 1st Class Benjamin Cosse / California National Guard)

Prediction and modeling

Mapping dry wildfire fuels with ai and new satellite data.

Stanford researchers have developed a deep-learning model that maps fuel moisture levels in fine detail across 12 western states, opening a door for better fire predictions.

Predicting wildfires with CAT scans

Engineers at Stanford have used X-ray CT scans, more common in hospital labs, to study how wood catches fire. They’ve now turned that knowledge into a computer simulation to predict where fires will strike and spread.

Satellite imagery shows hot spots and thick smoke plumes from wildfires burning in Oregon and northern California on Sept. 8, 2020. (Video credit: NOAA)

Stanford Wildfire Research

Find experts, events, information about ongoing research projects and more.

Stanford Wildfire News

Read the latest wildfire coverage from Stanford News.

Media Contacts

Josie Garthwaite School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (650) 497-0947; [email protected]

Explore More

Looking back on the first year of Stanford Ecopreneurship

A new report shares key accomplishments from the inaugural year of Stanford Ecopreneurship programs, a collaboration between the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability and Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Living Laboratory Partnership Summit kicks off Earth Month at Stanford

The summit convened students, faculty, and staff Tuesday to celebrate the sustainability collaborations and achievements taking place across campus.

Confronting the ‘two-headed monster’ of environmental injustice

Scholars and community leaders gathered at an environmental justice conference to discuss the importance of community-driven research, intersectional frameworks, and institutional legitimacy.

- Environmental justice

The Past, Present, and Future of California Wildfires

Essay By Professor Jeffrey Kane

The 2018 wildfire season in California was the deadliest and most destructive on record, burning almost 1.9 million acres—an area 2.5 times the size of Rhode Island and more area than had ever burned in California within the past 50 years. Most scientists, managers, and firefighters would tell you that last year's fire season was not a surprise.

If a fire season like this didn't occur last year, it would have been this year or next year or the year after that. In fact, 15 of the 20 largest fires in California state history have occurred since 2000. The tragic fires of 2018 are part of a broader pattern occurring across the West that shows no sign of abating in the near future unless we make substantial changes. We can surely agree that more needs to be done to limit the impacts of these events.

The 2018 fire season is the culmination of three main factors: climate change, past fire and forest management practices, and development in the wildland urban interface.

The marked increase in greenhouse gases over the past century has increased the average temperature in California by 2 to 3 degrees Fahrenheit. This seemingly modest difference has profound impacts on our state. Warmer temperatures are extending the fire season, meaning that fires are burning earlier in the spring and later into the fall. The fire season in the Sierra Nevada, for example, has doubled in length and is now more than 10 weeks longer than it was three decades ago. Under warmer conditions, the atmosphere also draws more water from the ground. This increase in evaporative demand more readily dries out fuels that can easily ignite.

Exacerbating the effects of climate change on fire is the legacy of past fire and forest management. For thousands of years prior to Euro-American settlement, Native American tribes and lightning fires burned 5 million acres in California every year, with many areas burning every 10 years or so. These fires were typically more benign, burning more often but at lower intensities. The federal government's focus on fire suppression has resulted in denser forests with more continuous fuel to burn in an intense fire. These conditions are quite common around and within most communities.

15 of the 20 largest fires in California state history have occurred since 2000

Finally, the population of California has grown rapidly over the past 75 years, increasing the risk of devastating wildfires. More homes are being built within or near wildlands and constructed with materials that can often burn easily.

Forestry major Tenaya Wood, president of HSU's Student Association for Fire Ecology club, works a fire line. Wood and other students from the club joined representatives from various organizations for the Prescribed Fire Training Exchange on Yurok land in the Klamath Mountains last year. The program teaches participants how to use controlled burns to manage land.

These are daunting and often human-driven factors that we can reverse with effective policies and sufficient resources.

One thing that seems particularly evident is that fire can be a great unifier. An example of this is the growing support for expanding the use of prescribed fire, or controlled burning, which was once a common way of managing California ecosystems. In fact, one might say there has been a prescribed fire renaissance over the past decade as more people return to this practice to help reduce fuels, restore ecosystems, and protect communities. The Western Klamath Restoration Partnership is also manifesting a positive trajectory by embodying an “all hands, all lands” perspective to encourage private and public partners to solve some of these challenging problems together.

It will be up to future managers, scientists, and homeowners to solve these fire challenges. Thus, it is imperative to provide students with the knowledge, skills, and ability to tackle this problem.

Humboldt State University's Forestry program works toward this goal through education, experience, and exposure to research related to the science and management of fire-prone ecosystems.

Forestry Professor Jeffrey Kane (far right) and his students observe fire behavior in HSU's fire lab.

The program focuses on fire ecology, fire behavior, and fuels management to address current and future problems in California. Students use our indoor fire lab to burn fuels and research fire behavior. This active learning experience reinforces concepts learned in the classroom.

However, learning concepts and science necessary to inform appropriate management responses related to fire is not enough. That's why we're working with local partners, including Native American tribes, to provide students real-life experiences with wildland fire and fuels. For instance, students have participated in the The Nature Conservancy's prescribed fire training exchange program, also known as TREX, in the Klamath Mountains. Last year, 10 HSU students worked with the Cultural Fire Management Council to help bring fire back to Yurok tribal lands and to revitalize this once widespread management practice.

Students are investigating the long-term effectiveness of fuel treatments in the lower elevation shrublands and woodlands of Whiskeytown National Recreation Area, which burned in the 2018 Carr fire. Students are also researching the use of creative thinning techniques and prescribed burning treatments to reduce drought- and bark beetle-caused tree mortality in the central Sierra Nevada.

Events like those of the 2018 wildfire season tug at the heartstrings. Stories of so many lives and homes lost to fire, pictures of the rubble-strewn foundations, and charred forests can invoke the deepest of sympathies and feelings of loss. These images are powerful and harken the destructive potential of fire.

But fires can be restorative and must be part of the solution. The beauty and natural heritage of this state exist, in part, because of fire, which is an essential component of the California landscape. Many ecosystems have seen either too little, too much, or the wrong kind of fire, and the key is to find better ways humans and fire can coexist.

About the author

Jeffrey Kane is a professor of Forestry at Humboldt State, among the top fire science institutions in the country and one of only three universities that have a fire lab. His areas of research include ecology and management of fire-prone ecosystems.

Search form

- Find Stories

- For Journalists

Stanford experts reflect on the most destructive fire season in California history

The 2018 fire season in California gave Stanford experts much to think about, including how the state can develop better policies for preventing fires and new research to better understand the long-term effects of breathing smoky air.

Scenes like this one following a fire in San Diego County are becoming more commonplace in California. (Image credit: Katrina Swietek / Getty Images)

In November, the Camp Fire in Butte County and the Woolsey Fire near Los Angeles together killed at least 90 people, burned more than 250,000 acres, destroyed more than 20,000 structures and generated unhealthy air conditions in communities hundreds of miles away. The fires also gave Stanford faculty much to consider as they look ahead to a hotter, drier climate and the possibility of even more destructive fire seasons in the future.

We asked experts in health, climate change and public policy to discuss what they learned from this fire season, how the fires influenced their research objectives and ideas they have for fire prevention.

Noah Diffenbaugh

The recent fires highlight the growing risks in California and the American West. Many of the recent fires in California have occurred with record or near-record combustible material that have been elevated by hot conditions. Decades of research show not only that the area burned in the West has been increasing, but also that global warming has been playing a role by increasing the dryness of vegetation on the landscape. The National Climate Assessment that was released by the U.S. government the day after Thanksgiving confirmed this evidence, highlighting that global warming has been responsible for around half of the historical increase in area burned.

With regards to the conditions in California over the past few years, it is clear from multiple lines of evidence that California is now in a new climate, in which conditions are much more likely to be hot, leading to earlier melting of snowpack and exacerbating periods of low precipitation when they occur. The net effect is an extension of the fire season and greater potential for large, intense wildfires.

A key research question going forward is exactly how much the odds of the record-setting conditions that we have just experienced have already been elevated, and how much further they will be elevated in the coming years as global warming continues to unfold.

Mary Prunicki

While we have been investigating the impact of air pollution and wildfires on health, the main focus previously for us and others has been on the health consequences for those relatively close to the fire. The Camp Fire, on the other hand, highlighted the massive impact that wildfires can have on those over 200 miles away. As a result, our center (The Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research) collected biomarkers (for example, blood and saliva) from Bay Area residents during the period of increased smoke exposure from the Camp Fire. We will re-collect biomarkers from the same subjects in one month, when the air quality has been at the typical low levels for several weeks. Our goal will be to look for differences in immune function during the two time periods to help determine the health implications for those exposed to the wildfire smoke in the Bay Area and, potentially, whether wearing a mask during the wildfire smoke altered immune outcomes. These are important questions, as the immune system is not only involved in fighting infections but is key for immunity, autoimmune disease, allergy, asthma, cancer and other diseases.

Rebecca Miller

State legislators responded to the catastrophic 2017 wildfire season with bills that proposed to increase fuel treatments around California through timber thinning and prescribed burns. Gov. Brown issued an executive order in May to establish training and certification programs for prescribed burns and to double the number of actively managed acres in California through thinning, prescribed burns and reforestation. The long-term effects of this executive order and the new wildfire legislation from the 2017–18 session have yet to be seen.

The devastating 2018 wildfires place greater urgency on the need to respond to California’s wildfire problem. Both of these wildfire seasons affected rural and urban areas and also hit Northern and Southern California, increasing interest for action from legislators beyond those from traditionally rural or forested districts. Governor-elect Gavin Newsom has already declared wildfire planning to be a priority of his administration. Looking ahead to the 2019–20 session, wildfires will likely be a major topic of proposed legislation and executive action.

There are dozens of communities in California and in the rest of the western United States that are at risk of a catastrophic fire in a similar way as Paradise, California, and we need new strategies and technologies to proactively protect them instead of being limited to reactive suppression efforts. While my lab has been focusing on developing a new fire-prevention technology to be leveraged in these high-risk areas, complementary efforts are needed to (1) identify these high-risk areas and (2) fund projects to leverage new technologies for fire prevention.

On the first point, three factors crucial to identifying high-risk areas are: (1) where do fires happen (exact latitude and longitude), (2) how do they happen, and (3) total number of starts per year. The current post-fire reporting that fulfills federal, state, county and city filing requirements most often lacks critical details such as the exact coordinates of where the fire originated (these are often simply placed at the nearest road intersection). Moreover, post-fire investigation is often unable to determine any obvious culprit and the cause of ignition is reported with the exceedingly unhelpful “undetermined” designation. Furthermore, only fires larger than 10 acres are typically reported to the Fire and Resource Assessment Program and are searchable on the state database, but this excludes thousands of fires, many of which could have grown to be catastrophic if conditions on the day were different. Therefore, in order to identify high-risk areas that are burning year after year and draining local, state and federal agencies of their resources, we find ourselves relying on the memories of fire professionals to determine where, how, and how often fires occur.

On the second point, a large Cal Fire (California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection) grant RFP (request for proposals) is now open for large prevention-oriented projects, but applications are due in mid-December, posing a massive hurdle for the various fire-related agencies in each district – considering that many are still engaged in recovery efforts. Moreover, we have seen that proposals for fire prevention efforts in very high-risk areas in several counties in California have not been funded, despite the fact that these areas routinely have dozens of ignitions per year. One example project is along a highway in Ventura County, where a proposed project to protect the roadside for the 2018 fire season was not funded on this mechanism and the district suffered numerous fire starts and one large 160-acre fire this year that all originated on the side of this road. Worst of all, the large fire occurred while the Woolsey Fire was raging. (It wasn’t started by the Woolsey Fire). Further, this RFP is one of the first major investments in prevention. Most of the available money is specifically slated to support reactive fire suppression efforts and very few funds are available for proactive fire prevention efforts. It seems what we really need is for legislators to green-light funding of prevention efforts in each district statewide so these agencies have the ability to protect their own high-risk areas right now, without having to cross their fingers and hope they get awarded a grant to protect those areas year after year.

Michael Wara

The Stanford Climate and Energy Policy Program has been working with California legislators since the 2017 wildfires to help them better understand the root causes of destructive wildfires and to take legal and policy steps aimed at reducing risks and creating greater safety for California. This work culminated in framing key issues and the legislative approaches taken by the legislature in the 2017 session.

The Camp and Woolsey fires have reinvigorated this legislative conversation and the Climate and Energy Policy Program is again working with stakeholders to identify potential solutions and perform the necessary analysis to fully develop and vet them. These efforts engage students and faculty from a variety of disciplines across campus including law, business, engineering and the natural sciences.

Rob Jackson

The loss of life and destruction from this year’s California fires is record-breaking and tragic. The danger continues even hundreds of miles away for people breathing smoky air across the state, including the San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles. Earlier this year, a paper in the Journal of the American Heart Association showed how fires in California in 2015 sent more people to emergency rooms for cardiovascular problems, including heart failure and stroke. More shockingly, recent research at the California National Primate Research Center has shown the effects of being outdoors and breathing sustained, smoky air is particularly damaging for primates younger than three months of age – and lasts for years. Smoky air affects us all, but our young and our old are the most vulnerable by far.

Our work on droughts and fires highlights some of the increased risks observed today. Our work on changing fire regimes, including fire suppression and controlled burns, provides opportunities for reducing some of them.

[Jackson recently wrote about increased fire risk and other climate-related threats in this Scientific American blog post .]

For more faculty who study climate, health and policy related to wildfires, see Stanford’s wildfire experts list .

To read all stories about Stanford science, subscribe to the biweekly Stanford Science Digest .

California Wildfire Disaster: The Emergency Response Essay

Introduction.

Nations across the world repeatedly encounter emergency situations that push the safety systems to the limits and require immediate and effective action to save human lives with possible retention of vitally important resources. Being of different levels of severity and threat to human lives and safety, both natural disasters and man-induced catastrophes cause significant damage. It is crucial for national security systems and disaster management agencies to have effective contingency and emergency response plans that would minimize harm and losses at a crucial moment. The best way to generate and promote effective disaster response is through analysis and improvement planning.

In this paper, the disaster incident of wildfires in California in 2021 will be reviewed to assess the effectiveness of response and communication strategies to generate possible recommendations for better action in the future. The wildfire seasons occur regularly in the USA and adversely impact numerous states across the country, California being one of the most vulnerable regions. Given the threatening pace of climate change across the globe, with average temperatures rising and droughts increasing, the risks of wildfires enhance worldwide. Therefore, it is imperative to review and assess emergency response to wildfires to address it from the perspectives of Qatar’s emergency response systems.

Aim and Objectives of the Document

The aim of the current document is twofold and is influenced by the need for continuous improvement of communication strategies in times of crises and emergencies to ensure public safety. In particular, the first aim of the paper is to review the instance of the wildfire disaster in 2021 as a threatening emergency. Secondly, the paper is designed to generate particular communication strategies and emergency response recommendations to minimize harm and losses for societies, including Qatar, facing similar hazards under the growing impact of climate change.

To pursue the general aims of the document, several specific objectives are pursued. Namely, it is necessary to assess the quality of governmental and emergency departments’ response to the disaster. In addition, the communication strategies used before, during, and after the emergency need to be analyzed and assessed as per their effectiveness in predicting, preparing, addressing, and recovering after the incident. Moreover, it is particularly important to generate an effective communication strategy to inform vulnerable and difficult-to-reach populations to ensure that the lessons learned from California’s disaster are efficiently applied to future incidents. Lastly, the recommendations for the authorities and agencies should be presented to ensure that the drawbacks are approached for proper correction, and the strengths of the emergency response tactics are reinforced.

Given the complexity of the problem and the difficulty of incorporating efforts to avert the crisis, the scope of the document will be limited to the review of communication strategies and immediate emergency responses. In particular, the government action during and after the wildfire will be analyzed, responsible agencies’ aid and public informing efforts will be evaluated, as well as the recovery actions will be addressed. The paper will not take into consideration the financial aspect of the problem, as well as will not refer to wildfires in other states of the USA at the same period of time. The selection of these particular emergency response elements and this region is validated by the severity of losses and its high probability of representation of similar occasions globally.

Authorities’ Communication Strategies and Outcomes Assessment

The quality, effectiveness, and timeliness of response to an emergency are the key factors that guarantee saved lives and reduced losses in the outcome. Uncontrolled wildfires in California in 2021 had a devastating impact on the forestry and the towns, citizens, and their dwellings and infrastructure. Among the three largest fires, the Dixie fire destroyed 733,475 acres with 43% containment, the “Monument fire has burned 152,125 acres and was 20% contained,” and the Caldor fire burned 122,980 acres with 11% containment” (Yee, 2021, para. 6-7). Such a fast and disruptive force of the disaster necessitated immediate action and informing of the public.

As the wildfires started, numerous responsible agencies started their work immediately to prevent the fires from spreading and ensure people’s safety. In particular, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection and Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) appointed their crews to work in the impacted counties and districts (Yee, 2021). Firefighters and emergency responders were sent to the locations caught on fire to stop the burning and provide help to the victims (Yee, 2021). The injured were hospitalized, and the endangered residents were evacuated. As the crisis unfolded, President Biden “approved a major disaster declaration …, opening up federal funding for grants, temporary housing, repairs and other relief efforts as multiple blazes continue to sweep across the Golden State” (Yee, 2021, para. 1). In addition, some non-profit organizations were swiftly involved in accommodating the victims, which was very important in the early stages of the emergency, as well as after it.

Moreover, not only state and county agencies but also federal authorities were included in the work on the elimination of the adverse outcomes of the disaster. According to FEMA (2021), Fire Management Assistance Programs have been initiated to help stop the fires and address the outcomes. In general, the authorities’ response to the California wildfires in 2021 has been informed by prior experiences of similar disasters in the same region. Before the disaster, the public was warned about the rising temperatures and the increasing risks. However, not all of the incidents were predicted since many emergencies occurred as no-notice situations. According to research, “no-notice events are complicated to manage for authorities and residents alike; authorities may struggle to communicate quickly with the population, while residents have limited time between notification and evacuation decisions” (Grajdura, Qian and Niemeier, 2021, p. 1). Therefore, although the public was timely evacuated, thousands of homes were not saved due to the large scale of the disaster and insufficient resources for response.

An evacuation warning is essential for such a fast-spreading disastrous event as no-notice wildfire. Indeed, “the outcome of a wildfire evacuation depends on many complicating factors but is highly influenced by the quality of the information received and the dissemination tactics that are used to “spread the word” (Grajdura, Qian and Niemeier, 2021, p. 2). Local authorities used media to reach all populations and inform them about the evacuation procedures. Nonetheless, the communication strategies used by the agencies were general and did not particularly include the needs of the marginalized population groups. However, the large scope of damage to households and infrastructure demonstrates that the timeliness of firefighters’ response and the resources available to first responders were insufficient to manage such a fast-spreading disaster.

In the aftermath of the incident, the authorities used multiple channels of communication to deliver messages addressing the outcomes of the disaster. In particular, at the local level, the government spread the information among the citizens to inform them about shelters, financial aid for recovery, and other survival information. Californian authorities engaged in cooperation with emergency management agencies and non-profit organizations to inspect the damaged areas and estimate the level of damage caused. Special grants and funds were launched to help the survivors of the disaster repair their homes and obtain accommodation in the aftermath of the emergency (FEMA, 2021). To disseminate this information and available recovery aid opportunities to the public, the authorities used social media, news programs, and broadcasting agencies. In such a manner, the population was provided with necessary information as per the guidance on how to act further.

Generated Communication Strategy

The review of California wildfires demonstrated that such a drastic natural disaster imposes a significant burden on the responsible agencies. The fast pace of the incident unfolding and the uncontrolled and often unpredictable nature of such kind of disaster limit the time for informing the citizens about the hazard and giving guidance on when and where to evacuate. While there are multiple obstacles to effective and timely emergency response, the chances to reach the groups of the public that might be difficult to inform even grows. Indeed, “disaster survivors from socially marginalized groups, including low-income residents and communities of color, are most at risk of experiencing long-term housing issues following disasters” (Rosenthal, Stover and Haar, 2021, para. 8). Therefore, these vulnerable populations might be the most difficult to communicate emergency messages to due to their marginalized status. Overall, “successful public communication seeks to balance the needs and expectations of all of these diverse audiences and speak to each of them while not miscommunicating to the remainder” (Haupt, 2021, p. 128). In addition, people representing an elderly generation might also be considered the population that would be the most difficult to inform due to the limited channels of information exchange available to them.

In order to achieve success in the appropriate dissemination of warning messages for evacuation or disaster prevention, special efforts should be made by authorities. According to Généreux et al . (2021), communication strategies that are deemed most pertinent under such circumstances include those that eliminate the promotion of fear in public and send clear messages addressing pivotal psychological factors that might play a decisive role in addressing the emergency. Only credible and authoritative information should be distributed across conventional and non-conventional communication channels. Indeed, since older people or those marginalized might have no access to smartphones, social media might not be an effective channel to reach these populations (Grajdura, Qian, and Niemeier, 2021). When provided with a clear and timely message, people will not waste valuable time seeking additional information or clarification (Haupt, 2021). It is imperative to include TV and radio as the communication media to ensure that all individuals obtain clear guidance on how to act in an emergency.

Another important strategy in the communication of emergency response is multilingual messages to ensure that people with limited language proficiency understand the situation and comprehend the plan of action. Furthermore, consistency is another pivotal element in an effective communication strategy designed to warn the public about a disaster. Proper behavior should be designed in clear step-by-step instructions with key contacts and locations of emergency rooms, shelters, and food centers provided in a timely manner. The instructions should be simple to avoid confusion under the stressful and hectic circumstances of wildfire. The fast pace of fire spreading should be emphasized to ensure that people act instantly and evacuate immediately, taking only the most necessary possessions with them without wasting time.

Since wildfires are particularly dependent on weather changes, such as temperatures, humidity, and wind speed, and direction, the interaction of authorities with meteorological centers is imperative. Indeed, the frequent occurrence of wildfires in different states of the USA, especially in California, serves as a factor of being equipped with data for better response to the emergency in the future. The awareness of risks should be informed by the close cooperation between the emergency management agencies and departments for immediate action in case of necessity. Research suggests that “disasters are also known to have considerable impacts on social determinants of health, such as housing and employment” (Rosenthal, Stover and Haar, 2021, para. 8). That is why people’s concerns about their health and dwellings should be addressed as they reach the emergency points. Thus, timeliness, clarity, consistency, availability, multilingual messages constitute the essential elements of an effective emergency response communication strategy.

In summation, the review of the work of first responders to the California wildfire disaster allows for stating that the response was effective. The evacuation messages were disseminated successfully and in a timely manner. People were evacuated swiftly, which guaranteed saved lives. However, despite the predictability of the emergency, the resources and efforts of the authorities were insufficient to save the dwellings and infrastructure of multiple towns. Also, the subsequent actions aimed at informing people about aid, financial support, healthcare, and shelter services were generalized and insufficiently addressed the needs of marginalized population groups. Therefore, it is imperative to integrate a more effective communication strategy that would include consistent, timely, and clear messages available to diverse populations at all levels of emergency response.

Recommendations

The studied incident and the review and analysis of California wildfires that happened in 2021 allow for making several recommendations for Qatar. Although the country does not have a high risk of wildfires in general, there are multiple factors that might cause this natural disaster to unfold in any area. For example, droughts, high temperatures, specific features in vegetation, wind patterns, and other weather and landscape particularities might contribute to the probability of wildfires. Moreover, since climate change impacts all countries of the world, Qatar should develop wildfire emergency response strategies. For that matter, the national authorities should learn from the experience of the USA emergency management agencies to prevent and predict such disasters. At the ‘before the disaster’ stage, the authorities should cooperate with meteorological agencies to ensure the availability of updated information on the weather conditions that might trigger fires. Also, the public should be informed about the elevated risks to prepare safety kits for the case of an emergency.

Most importantly, the crucial stage of emergency response is the messages and actions that take place during the disaster. It is imperative to borrow the same communication strategies to ensure the timely evacuation of the endangered citizens. Also, it is important not to make the mistakes made by the analyzed authorities and ensure that all the population groups, included marginalized ones, obtain clear, consistent, and credible information through communication channels available to them. At the ‘after disaster’ stage, the authorities should provide financial, healthcare, and shelter aid to the survivors by informing them about available options in a timely and comprehensive manner. Consequently, using these recommendations, the emergency response agencies of Qatar will be able to mitigate the adverse outcomes of wildfires if such should occur.

Federal Emergency Management Agency (2021) Wildfire action . Web.

Genereux, M. et al . (2021) ‘Communication strategies and media discourses in the age of COVID-19: an urgent need for action’, Health Promotion International , 36(4), pp. 1178-1185.

Grajdura, S., Qian, X., and Niemeier, D. (2021) ‘Awareness, departure, and preparation time in no-notice wildfire evacuations’, Safety Science , 139(105258). Web.

Haupt, B. (2021) ‘The use of crisis communication strategies in emergency management’, Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management , 18(2), pp. 125-150.

Rosenthal, A., Stover, E. and Haar, R.J. (2021) ‘Health and social impacts of California wildfires and the deficiencies in current recovery resources: an exploratory qualitative study of systems-level issues’ , PloS One , 16(3), p. e0248617. Web.

Yee, G. (2021) ‘President Biden approves wildfire major disaster declaration in California’, Los Angeles Times. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, November 28). California Wildfire Disaster: The Emergency Response. https://ivypanda.com/essays/california-wildfire-disaster-the-emergency-response/

"California Wildfire Disaster: The Emergency Response." IvyPanda , 28 Nov. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/california-wildfire-disaster-the-emergency-response/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'California Wildfire Disaster: The Emergency Response'. 28 November.

IvyPanda . 2022. "California Wildfire Disaster: The Emergency Response." November 28, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/california-wildfire-disaster-the-emergency-response/.

1. IvyPanda . "California Wildfire Disaster: The Emergency Response." November 28, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/california-wildfire-disaster-the-emergency-response/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "California Wildfire Disaster: The Emergency Response." November 28, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/california-wildfire-disaster-the-emergency-response/.

- California Wildfires: The Issue of the Proper Communication

- Dangers, Causes, and Effects of Wildfires

- Emergency Plan for Wildfires in California

- Impact of Climate Change on Increased Wildfires

- Wildfires and Impact of Climate Change

- Idaho Wildfires: Health and Economic Challenges

- "Fort McMurray Fires Cause Air Pollution" by McDiarmid

- Hazard Adjustments in Alaska

- Wildfire Forensic Company's Risk Assessment

- Emergency Preparedness to Natural Disasters in Healthcare

- Core Humanitarian Standards Applied to Natural Disasters

- Hurricane Katrina and Failure of Emergency Management Operations

- Natural Disasters: Earthquakes, Volcanoes, and Tsunamis

- Earthquake Disaster Preparedness in Healthcare

- Tonga Cyclone Gita

- Original research

- Open access

- Published: 25 August 2021

Large California wildfires: 2020 fires in historical context

- Jon E. Keeley ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4564-6521 1 , 2 &

- Alexandra D. Syphard 3

Fire Ecology volume 17 , Article number: 22 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

27k Accesses

73 Citations

33 Altmetric

Metrics details

California in the year 2020 experienced a record breaking number of large fires. Here, we place this and other recent years in a historical context by examining records of large fire events in the state back to 1860. Since drought is commonly associated with large fire events, we investigated the relationship of large fire events to droughts over this 160 years period.

This study shows that extreme fire events such as seen in 2020 are not unknown historically, and what stands out as distinctly new is the increased number of large fires (defined here as > 10,000 ha) in the last couple years, most prominently in 2020. Nevertheless, there have been other periods with even greater numbers of large fires, e.g., 1929 had the second greatest number of large fires. In fact, the 1920’s decade stands out as one with many large fires.

Conclusions

In the last decade, there have been several years with exceptionally large fires. Earlier records show fires of similar size in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Lengthy droughts, as measured by the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI), were associated with the peaks in large fires in both the 1920s and the early twenty-first century.

Antecedentes

En el año 2020, California experimentó un récord al quebrar el número de grandes incendios. Aquí situamos a éste y otros años en un contexto histórico mediante el examen de registros de incendios en el estado desde 1860. Dado que la sequía es frecuentemente asociada a grandes eventos de incendios, investigamos la relación entre grandes incendios y sequías en este período de 160 años.

Este estudio mostró que eventos extremos como el visto en 2020 no son históricamente desconocidos, y lo que se muestra como distintivamente nuevo es el incremento en el número de grandes incendios (definidos aquí como > 10.000 ha) en el último par de años, y más prominentemente en 2020. Sin embargo, ha habido otros períodos con aún mayores números de incendios (i.e. en 1929 hubo mayor número de incendios que en cualquier otro año del registro). De hecho, la década de 1920, fue una de las que presentó mayor número de grandes incendios.

Conclusiones

En la última década ha habido muchos años con incendios excepcionalmente grandes. Antiguos registros muestran incendios de tamaño similar tanto en el siglo 19 como en el siglo 20. Sequías prolongadas, medidas mediante el Índice de Sequías Severas de Palmer (PDSI), fueron asociadas con los picos de grandes incendios tanto en el siglo 20 como en el 21.

Introduction

The western US has a long history of large wildfires, and there is evidence that these were not uncommon on pre-EuroAmerican landscapes (Keane et al. 2008 ; Baker 2014 ; Lombardo et al. 2009 ). One of the biggest historical events was the 1910 “Big Blowup,” which reached epic proportions and was an important impetus for fire suppression policy (Diaz and Swetnam 2013 ). California in particular has had a history of massive wildfires such as the 100,000 ha 1889 Santiago Canyon Fire in Orange County or the similarly large 1932 Matilija Fire or 1970 Laguna Fire (Keeley and Zedler 2009 ).

While large fires are known in the historical record, in the first few decades of the twenty-first century, the pace of these events has greatly accelerated (Keeley and Syphard 2019 ). In the last decade, the state has experienced a substantial number of fires ranging from 10,000 ha to more than 100,000 ha, and these have caused massive losses of lives and property. The largest fires on record were recorded in 2018 and then were replaced with even larger fires in 2020, although some of these were the result of multiple fires that coalesced into fire complexes of massive size.

Causes for these fires are multiple, but climate change has been implicated as a critical factor (Williams et al. 2019 ; Abatzoglou et al. 2019 ). Historically, drought has often been invoked as a driver of large fires (Keeley and Zedler 2009 ; Diaz and Swetnam 2013 ), and California has experienced an unprecedented drought in the last decade (Robeson 2015 ). However, factors such as management impacts on forest structure and fuel accumulation, made worse by the recent drought, are critically important in some ecosystems (Stephens et al. 2018 ).

To put these recent fires in a historical context, we have investigated the history of large wildfires in California. “Large” fires is an arbitrary designation, e.g., Nagy et al. ( 2018 ) considered it to be 1000 ha or more. Our focus, however, is on those fires that made 2020 particularly noteworthy; so we define large fires as those in the top 1–2% of all fires, which is approximated by fires > 10,000 ha. In addition, we have examined the relationship of large fires to drought.

The database of fires > 10,000 ha was assembled from diverse sources. From 1950 to the present, the State of California Fire and Resource Assessment Program (FRAP) fire history database was relatively complete, but less so prior to 1950 (Syphard and Keeley 2016 ; Miller et al. 2021 ). In California, US Forest Service (USFS) annual reports provide statistics on fires by ignition source and area burned back to 1910 and Cal Fire back to 1919 (Keeley and Syphard 2017 ), and although these reports focused on annual summaries, they often provided descriptions of very large fires. A rich but under-utilized historical record for early years was the exhaustive compilation of fires in a diversity of documents from 1848 to 1937, assembled by a USFS project and brought to our attention by Cermak’s ( 2005 ) USFS report on Region 5 fire history. This source presents all documents (including agency reports and newspaper reports on fire, vegetation, timber harvesting and Native Americans) for all counties in the state and comprises 69 bound volumes (USDA Forest Service 1939-1941 ). We utilized these documents where they presented data on fire size, either an estimate of acres burned or dimensions of the burned area. We did not include fire reports that lacked a clear indication of area burned; e.g., the 1848 fire described in the region of Eldorado County referred to an immense plain on fire and all the hills blackened for an extensive distance (USDA Forest Service 1939-1941 ), but lacked more precise measures.

Other sources included the following: Barrett ( 1935 ), based on USFS records and personal experiences as well as “early-day diaries, historical works, magazines and newspapers.” Greenlee and Moldenke ( 1982 ) included fire records from state and federal agencies as well as library and museum archives. Morford ( 1984 ) was based on unpublished USFS records accumulated during the author’s 41 years in that agency. Keeley and Zedler ( 2009 ) was based on records retrieved from the California State Archives and State Library. Cal Fire ( 2020 ) data, not part of the FRAP database, included agency records of individual fire reports (not available to the public but searchable by the State Fire Marshall Kate Dobrinsky). In a few cases, the same fire was reported by more than one source, sometimes with different sizes; when this occurred after 1950, we used the FRAP data and before that either Cermak ( 2005 ) or Barrett ( 1935 ) over other sources.

Reliability of these data sources is an important question to address. Stephens ( 2005 ) contended that USFS data before 1940 were unreliable, an assertion based on Mitchell ( 1947 ); but Mitchell ( 1947 ) provided no evidence that early data were inaccurate, only that many states lacked early records. Mitchell ( 1947 ) was considering availability of state and federal data for the entire USA; however, California has far better historical records at both the state and federal archives than much of the USA (Keeley and Syphard 2017 ). USFS records for California were reported annually for all forests beginning in 1910 and for state protected lands by Cal Fire back to 1919. The latter agency had by 1920 several hundred fire wardens strategically placed throughout the state and each warden was held to a strict standard of reporting all fires in their jurisdiction.

Before 1910, data on fires was dependent on unpublished reports available in state and federal archives, observations published in books, data given in newspaper accounts of fire events, and estimates from fire-scar chronology studies. It was suggested by Goforth and Minnich ( 2007 ) that early newspaper reports were exaggerations and represented “yellow journalism,” a pejorative term that connoted unethical journalism. This was based on what they considered sensational headlines, but comparison of nineteenth century with more recent newspaper headlines provides no basis for this conclusion (Keeley and Zedler 2009 ). As a journalist colleague suggested, “a century-old newspaper story is not a precise source …[but] is the first draft of history and a valuable source of first person account from long past events.” Such information qualifies as scientific evidence, which is defined as evidence that serves to either support or counter a scientific theory or hypothesis, is empirical, and interpretable in accordance with scientific method. The data we present falls within these bounds and that includes newspaper reports as we used data on fire size in terms of acres or dimensions of burned landscape reported. Recently Howard et al. ( 2021 ) demonstrated that fire-scar records match newspaper accounts in the eastern US. To address the issue of how close newspaper accounts used in this study come to accurately depicting fire size, we have compared fires reported in published sources with newspapers where available. We of course appreciate that early accounts lacked the precise technology available today for outlining fire perimeters; however, this lack of precision does not necessarily translate into less accurate accounts and applies to both newspapers as well as state and federal agencies.

Data were presented for the state and by NOAA divisions North Coast (1), North Interior (2), Central Coast (4), Sierra Nevada (5), and South Coast (6). These are the five most fire-prone divisions of NOAA’s National Climatic Data Center categories, defined as climatically homogenous areas (Guttman and Quayle 1996 ). There of course are other systems that may be useful for comparisons, dependent on the need. For example, the Bailey Ecoregions (Bailey 1980 ), which separates regions by vegetation type, might be thought preferable, but, for our purposes, there is no necessary advantage as large fires usually burn across a mosaic of different vegetation types. A system that might provide a better presentation would be the recently described Fire Regime Ecoregions (Syphard and Keeley 2020 ). However, despite limitations to the NOAA divisions (e.g., Vose et al. 2014 ), it is preferable due to the availability of historical annual data on the Palmer Drought Severity index calculated by NOAA divisions.

Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) was recorded for each year from two sources. From 1895 to 2020, PDSI was the annual mean from NOAA ( 2020a ), and for years prior to 1895, summer PDSI was reconstructed from tree-ring studies (Cook et al. 1999 ). Statistical analysis and graphical presentation were conducted with Systat software (ver. 13.0, Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA, http://www.systat.com/ ).

Since some of the fires came from data reported in newspapers, not a typical scientific data base, we did an initial investigation comparing FRAP reported fire size with size reported in newspaper reports. This was not an exhaustive study since FRAP data before 1950 presents relatively few fires by date or fire name making it difficult to match up fires with newspaper reports; however, we found half a dozen potential comparisons (Table 1 ). As to be expected these different reports are not identical in fire size, however, they were quite similar; sometimes, newspapers over reported area burn but other times under reported, although most importantly, they were of similar magnitude as those in the FRAP database. Data sources varied over time (Table 2 ); from 1950 to the present, large fires were all recorded in the FRAP database. Prior to that year, sources were mostly from USFS ( 1939-1941 ).

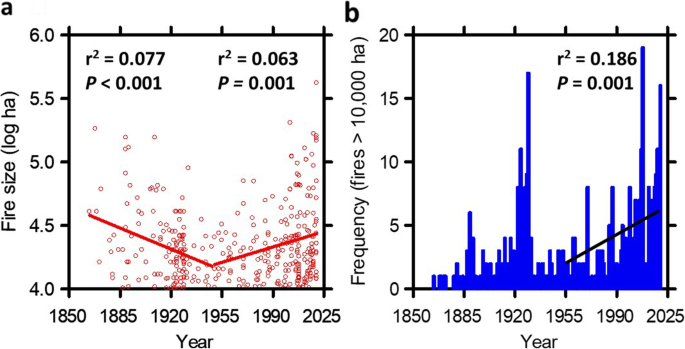

Fire size of all fires over 10,000 ha during the last 160 years are shown in Fig. 1 a. Exceptionally large fires followed a bimodal pattern with peaks in the nineteenth century and again in the twenty-first century, separated by a low point in the 1950s. From 1860 to 1950, there was a significant decrease in large fire size followed by a significant increase in the second half of the record. Although the trends were highly significant, the great year to year variation in size of large fires, gave low r 2 values, indicating limited ability to predict fire size for any given year.

a Fire size for large fires from 1860 to 2020. b Frequency of large fires over this same time period

To illustrate the temporal distribution of record-breaking fires, we picked the top 3% ( n = 12) of all fires based on size, and these are shown in (Table 3 ). Not surprisingly, 5 occurred in the year 2020; however, four occurred in the nineteenth century.

The data presented in this paper greatly expands our understanding of the history of large fires in California. To date, our dependence has been on the FRAP database and they clearly acknowledge their records are for fires from 1950 to the present, and this is borne out by our analysis (Table 2 ), but the records presented here extend the fire history back nearly a century. Over the period from 1860 to the present, yearly frequency of fires over 10,000 ha exhibited several prominent peaks (Fig. 1 b). A few peak years occurred in the 1920s, with one of the highest frequencies recorded throughout the entire 160 year record in 1929. There were also peaks in 2007 and 2008 and again in 2018 and 2020.

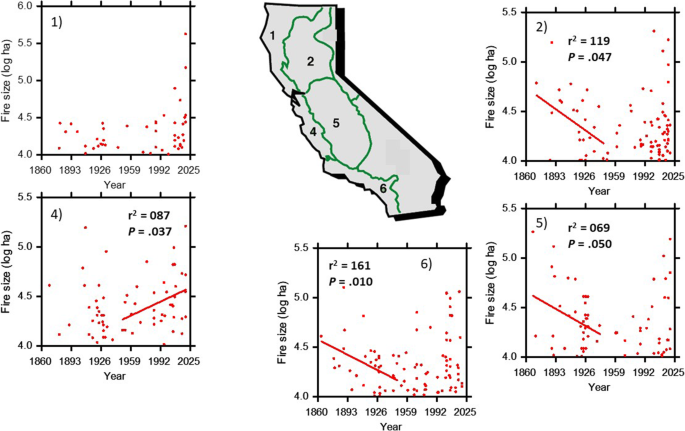

Through time, the distribution of fire size varied between NOAA divisions (Fig. 2 ). The North Interior (2), Sierra Nevada (5), and South Coast (6) divisions all exhibited a significant decline in fire size from the nineteenth century till 1950. Although all the regions exhibited the largest fires in the last decade, only in the Central Coast (4) was this significant for the years 1950–2020.

Large fires within NOAA Divisions. Statistics are presented for significant trends

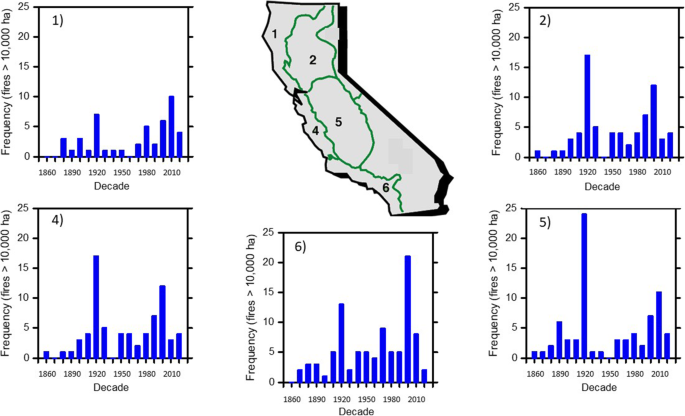

Frequency of fires over 10,000 ha are presented by decade for each of the five divisions (Fig. 3 ). Consistent with the statewide pattern (Fig. 1 b), all showed a spike in number of large fires in the 1920s and again after 2000. The 1920s peak was particularly prominent in the Sierra Nevada (5) and South Coast. Also, for the Central Coast and Central Sierra Nevada regions, the number of fires in the 1920s was higher than that for recent years. For the years 1860 to 1949 and for the years 1950 to 2020 separately, there was no significant change in frequency over time.

Decadal frequency of large fires within NOAA Divisions. Note the decade 2020 is represented by a single year.

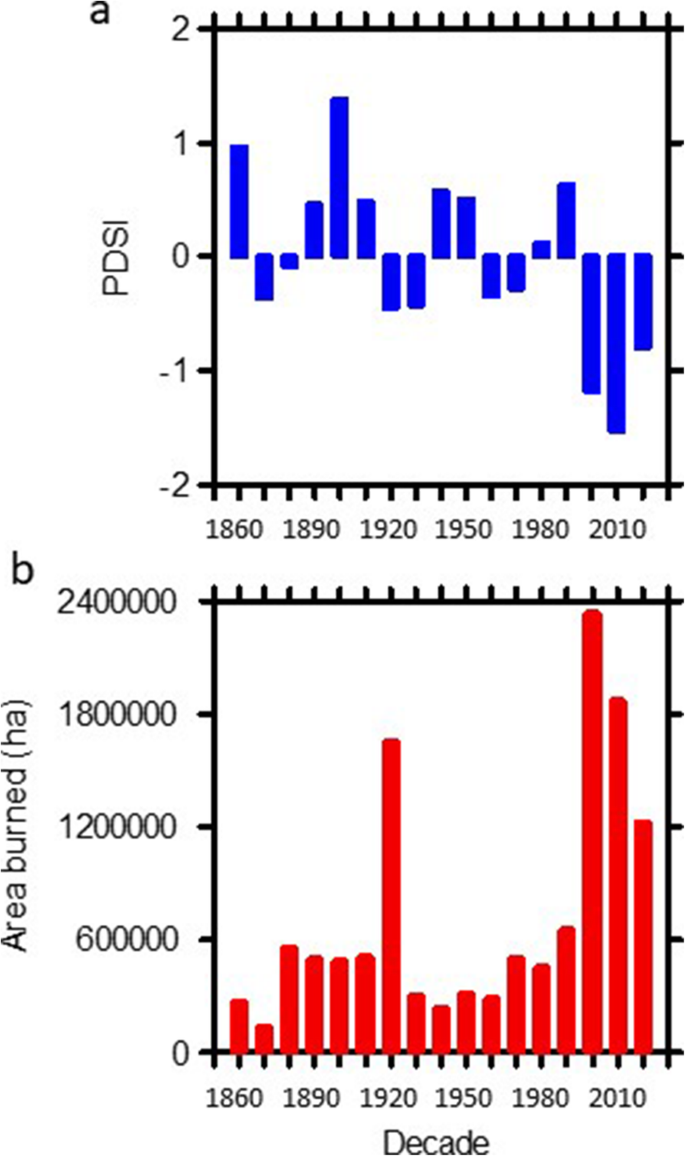

One aspect of climate over the entire period is captured by the PDSI, a drought index that includes patterns of both precipitation and temperature. There have been several periods of drought over the past 160 years, the most severe being in the decades 1920-1930 and 1990-2020 (Fig. 4 a). These periods also correlate with periods of large amounts of area burned by large fires (Fig. 4 b). Bivariate regression analysis showed that over the period from 1860 to 2020, there was a significant relationship between PDSI and area burned (adj r 2 = 0.429, P = 0.003).

a PDSI for the decades from 1860 to 2020. b Area burned by fires > 10,000 ha for the decades from 1860 to 2020. Note the decade 2020 is represented by a single year

Clearly, 2020 was a phenomenal fire year in California for record breaking large fires. However, this study shows that such extreme fire events are not unknown historically, and what stands out as distinctly new is the increased number of large fires (defined here as > 10,000 ha) in the last couple of years, most prominently in 2020. Given that historically we have seen years with even greater number of large fire events, e.g., 1929, a comprehensive evaluation of the factors leading up to large fire event years is clearly needed.

The largest fire in recorded history for the state is the 2020 August Complex Fire, which comprised 38 separate fires that were considered a single a massive 418,000 ha fire (Cal Fire 2020 ). Thus, the merging of these multiple fires into a larger event is certainly a factor affecting “fire” size. Indeed, some 2020 fire complexes included multiple fires that never actually merged; for example, the LNU Complex Fire, which ranked within the top 12 fires (Table 3 ), actually comprised several distinctly separate fires that apparently did not merge (San Francisco Chronicle 2020 ).

It has been contended that large fires in the past were often very different in nature from contemporary large fires. For example, many southwestern US mixed conifer forest large fire events in the nineteenth century were low-intensity surface fires, unlike contemporary large fires that are dominated by high-intensity crown fire (Keane et al. 2008 ). This contention, however, varies from descriptions of the top 12 fires recorded here (Table 3 ). For example, when describing the 1889 Plumas fire, newspaper reports state “A large amount of timber and fire wood [were] destroyed.” One report describes the 1891 Eldorado fire as “the most terrible forest fire ever experienced in California…fanned by a strong north wind has swept over almost the entire stretch of country between Georgetown and Salmon Falls…Magnificent forests of a few days ago have been burned over and blackened and lofty pines seared and killed. The scene at night baffles all powers of description, there being a moving mass of fire as far as the eye can reach.” The 1909 Santa Cruz fire was described as “this large conflagration spread… [and] the country is entirely burned over; the entire growth on Loma Prieta Peak and its sides down to Los Gatos Creek is a charred area.”

In general, very few of the large fires reported in (USDA Forest Service 1939-1941 ) were described as low-intensity surface fires. This source described forest fires up and down the state as high intensity conflagrations. For instance, in San Diego County, the 19,000 ha fire of 1870 was described as “the fires which have been raging in the mountains …are wholly unprecedented in extent and …destruction of timber”; in the San Luis Obispo 1869 40,000 ha fire “a great deal of timber and grass has been destroyed”; in Calavaras County in 1889, an 81,000 ha fire was described “A large forest fire has been raging…a large scope of timber country has been laid in waste”; a description of the Tehama 1889 30,000 ha fire was “The forest fire that has raged...was very destructive”, etc. In short, there is little in these records to suggest that nineteenth century large fires were normally less destructive of natural resources than twenty-first century fires. This of course is not meant to negate the commonly accepted paradigm that California forests in the past frequently burned with low-intensity surface fires (Skinner and Chang 1996 ), but that once fires reached epic proportions, and consequently burned through a mosaic of vegetation types, fire behavior appears to have been quite different.

However, one thing that is different between historical large fires and recent ones is that contemporary large fire events are often much more destructive in terms of loss of lives and property. For example, the 2018 Butte County Camp Fire driven by extreme foehn winds killed 85 people and destroyed over 18,000 buildings, however, a similar foehn wind driven fire occurred in Eldorado County in 1891 (Table 3 ), and there were no reports of fatalities and relatively few structures were lost (USFS 1939-1941 ). The difference is due to changes in human demography, e.g., California population throughout the nineteenth century was fewer than 2 million people in contrast to 2020 with a population approaching 40 million. Pressure to find affordable housing has resulted in urban sprawl into watersheds of dangerous fuels (Syphard et al. 2007 , 2019 ). In addition, population growth has played a role in increasing ignitions as most fires that result in human losses are of human origin (Keeley and Syphard 2018 ).

Another factor that is very different in recent decades, when compared to the middle of the century, is the frequency of large fires, with 2007, 2008, 2017, 2018, and 2020 all being peak years for number of large fire events. However, the 1920s were comparable to these recent decades, and in fact, 1929 was a peak year for frequency of large fire events (Fig. 1 b). The1920s decade was also a peak in most regions (Fig. 3 ). Although there was less structure loss in the 1920s, demographic changes could have been involved in terms of frequency of large fires, as the 1920s saw a major influx of people. In this decade, there were increased anthropogenic ignitions driven by greater access to wildlands due to rapid road construction and an order of magnitude increase in car licenses (Keeley and Fotheringham 2001 ).

Climate is widely viewed as a determining factor in fire size, and in particular, drought has been a major driver historically (Little et al. 2016 ; Madadgar et al. 2020 ; Huang et al. 2020 ). One of the important factors behind the 2020 fire events was the anomalously long and intense drought the region experienced beginning in 2012. This drought was experienced across the southern US (Rippey 2015 ) and lasted 3–5 years in California; it was considered to be one of the most severe droughts in California history (Robeson 2015 ; Jacobsen and Pratt 2018 ). The greatest number of recent large fires and size of these fires have been concentrated in the years since this drought (Fig. 4 ). Drought has also been implicated as a factor in other large California fires during the first decade of the twenty-first century (Keeley and Zedler 2009 ) as well as with large fire events in the 1920s, as shown in this study.

While a clear climate signal in terms of drought is a likely driver of big fire events in the state, an emerging issue is the role of anthropogenic climate change (Williams et al. 2019 ). While droughts have historically been a natural occurrence in California’s Mediterranean climate ecosystems, it has been postulated that global warming has made these droughts more severe. Estimates are that the 2012–2014 drought in the Sierra Nevada was perhaps 10–15% more severe due to global warming (Williams et al. 2015 ). This has important implications for the impact of drought on tree and shrub dieback that increases hazardous fuels and contributes to increased fire risk (Stephens et al. 2018 ). However, the relationship between drought and tree dieback in the state is complicated and impacted by competition and other factors (Das et al. 2011 ; Young et al. 2017 ).

The severity of the 2020 fire season in California is not the result of any one factor such as climate change but the result of the “perfect storm” of events. Winter and spring precipitation in the northern part of the state was only about 50% of average, August had a stream of dry lightning storms in northern California that ignited over 5000 fires (Cal Fire 2020 ), there was an intense heat wave in early September that elevated temperatures to record breaking levels (NOAA 2020b ), and forests in the northern half of the state had anomalous fuel loads due to a century of fire suppression and greatly exacerbated by the intense drought of 2012–2015 (Stephens et al. 2018 ).

It is a major challenge to parse out the role of anthropogenic climate change in driving 2020 fires. Certainly, the below normal rainfall year in the north fell within the natural range of variation. The extraordinary lighting storm was perhaps more severe than what is seen in most years, but was not at all unprecedented; e.g., in 2008 northern California experienced a similar event with over 6000 lightning strikes and burning over 400,000 ha from these fires alone, and this is a common phenomenon at a decadal scale, e.g., 1999, 1987, 1977, 1955 (Cal Fire 2008 ). Further contributing to the 2020 fires was the intense heat wave that may be linked to climate change (Gershunov and Guirguis 2012 ; Hully et al. 2020 ). The role of anomalous fuel accumulation due to more than a century of fire suppression and made much worse by 2012–2016 drought was also a major contributor to the size of these fires.

Historically, California fires as big as some of the largest fires in 2020 year have occurred as evident from records beginning in 1860. However, without question, 2020 was an extraordinary year for fires in California. This was driven by a multitude of factors but prominently is the extraordinary droughts the state has experienced in the last couple decades. Peaks in the number of large fires have occurred in the 1920s as well as in the twenty-first century and both occurred in decades with extended droughts.

Availability of data and materials

Data from published sources listed in the “Methods” section.

Abbreviations

California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection

Cal Fire’s Fire and Resource Assessment Program

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Palmer Drought Severity Index

Abatzoglou, J.T., A.P. Williams, and R. Barbero. 2019. Global emergence of anthropogenic climate change in fire weather indices. Geophysical Research Letters 46 (1): 326–336. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL080959 .

Article Google Scholar

Bailey, R.G. 1980. Description of the ecoregions of the United States. Misc. Publication 1931 . Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Google Scholar

Baker, W.L. 2014. Historical forest structure and fire in Sierran mixed-conifer forests reconstructed from General Land Office survey data. Ecosphere 5 (7): 79.

Barrett, L.A. 1935. A record of forest and field fires in California from the days of the early explorers to the creation of the forest reserves . San Francisco: USDA Forest Service.

Cal Fire. 2008. June 2008 California Fire Siege Summary Report . Sacramento: Cal Fire.

Cal Fire. 2020. Fire incidents. https://www.fire.ca.gov/incidents/

Cermak, R.W. 2005. Fire in the forest: a history of forest fire control on the national forests in California, 1898-1956 . Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office.

Cook, E.R., D.M. Meko, D.W. Stahle, and M.K. Cleaveland. 1999. Drought reconstructions for the continental United States. Journal of Climate 12: 1145–1162 ftp://ftp.ncdc.noaa.gov/pub/data/paleo/drought/NAmericanDroughtAtlas.v2/ .

Das, A.J., J. Battles, N.L. Stephenson, and P.J. van Mantgem. 2011. The contribution of competition to tree mortality in old-growth coniferous forests. Forest Ecology and Management 261 (7): 1203–1213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2010.12.035 .

Diaz, H.F., and T.W. Swetnam. 2013. The wildfires of 1910. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 94 (9): 1361–1370. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-12-00150.1 .

Gershunov, A., and K. Guirguis. 2012. California heat waves in the present and future. Geophysical Research Letters 39: L18710.

Goforth, B.S., and R.A. Minnich. 2007. Evidence, exaggeration, and error in historical accounts of chaparral wildfires in California. Ecological Applications 17 (3): 779–790. https://doi.org/10.1890/06-0831 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Greenlee, J. M. and A. Moldenke. 1982. History of wildland fires in the Gabilan Mountains region of central coastal California. Unpublished report under contract with the National Park Service.

Guttman, N.B., and R.G. Quayle. 1996. A historical perspective of U.S. climate divisions. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 77 (2): 293–303. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0477/WF13115 .

Howard, L.F., G.D. Cahalan, K. Ehleben, B.A. Muhammad El, H. Halza, and S. DeLeon. 2021. Fire history and dendroecology of Catoctin Mountain, Maryland, USA, with newspaper corroboration. Fire Ecology 17 (1): 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-021-00096-2 .

Huang, Y., Y. Jin, M.W. Schwartz, and J.H. Thorne. 2020. Intensified burn severity in California’s northern coastal mountains by drier climatic condition. Environmental Research Letters 15 (10): 104033. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aba6af .

Hully, G.C., B. Dousset, and B.H. Karn. 2020. Rising trends in heatwave metrics across southern California. Earth’s Future 8: e2020EF001480.

Jacobsen, A.L., and R.B. Pratt. 2018. Extensive drought-associated plant mortality as an agent of type-conversion in chaparral shrublands. New Phytologist 219 (2): 498–504. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15186 .

Keane, R.E., J.K. Agee, P. Fule, J.E. Keeley, C. Key, S.G. Kitchen, R. Miller, and L.A. Schulte. 2008. Ecological effects of large fires on US landscapes: benefit or catastrophe? International Journal of Wildland Fire 17 (6): 696–712. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF07148 .

Keeley, J.E., and C.J. Fotheringham. 2001. Historic fire regime in Southern California shrublands. Conservation Biology 15 (6): 1536–1548. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2001.00097.x .

Keeley, J.E., and A.D. Syphard. 2017. Different historical fire-climate relationships in California. International Journal of Wildland Fire 26 (4): 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF16102 .

Keeley, J.E., and A.D. Syphard. 2018. Historical patterns of wildfire ignition sources in California ecosystems. International Journal of Wildland Fire 27 (12): 781–799. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF18026 .

Keeley, J.E., and S.D. Syphard. 2019. Twenty-first century California, USA, wildfires: fuel-dominated vs. wind-dominated fires. Fire Ecology 15: 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-019-00410 .

Keeley, J.E., and P.H. Zedler. 2009. Large, high intensity fire events in southern California shrublands: debunking the fine-grained age-patch model. Ecological Applications 19 (1): 69–94. https://doi.org/10.1890/08-0281.1 .

Little, J.S., D.L. Peterson, K.L. Rilery, Y. Liu, and C.H. Luce. 2016. A review of the relationship between drought and forest fire in the United States. Global Change Biology 22 (7): 2353–2369. https://doi.org/10.1111/GCB.13275 .