Concept Papers in Research: Deciphering the blueprint of brilliance

Concept papers hold significant importance as a precursor to a full-fledged research proposal in academia and research. Understanding the nuances and significance of a concept paper is essential for any researcher aiming to lay a strong foundation for their investigation.

Table of Contents

What Is Concept Paper

A concept paper can be defined as a concise document which outlines the fundamental aspects of a grant proposal. It outlines the initial ideas, objectives, and theoretical framework of a proposed research project. It is usually two to three-page long overview of the proposal. However, they differ from both research proposal and original research paper in lacking a detailed plan and methodology for a specific study as in research proposal provides and exclusion of the findings and analysis of a completed research project as in an original research paper. A concept paper primarily focuses on introducing the basic idea, intended research question, and the framework that will guide the research.

Purpose of a Concept Paper

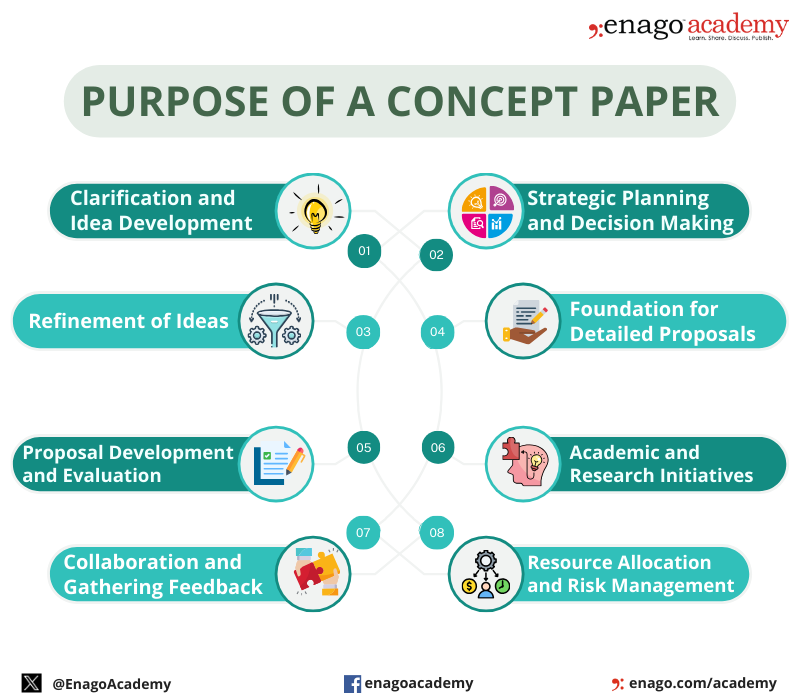

A concept paper serves as an initial document, commonly required by private organizations before a formal proposal submission. It offers a preliminary overview of a project or research’s purpose, method, and implementation. It acts as a roadmap, providing clarity and coherence in research direction. Additionally, it also acts as a tool for receiving informal input. The paper is used for internal decision-making, seeking approval from the board, and securing commitment from partners. It promotes cohesive communication and serves as a professional and respectful tool in collaboration.

These papers aid in focusing on the core objectives, theoretical underpinnings, and potential methodology of the research, enabling researchers to gain initial feedback and refine their ideas before delving into detailed research.

Key Elements of a Concept Paper

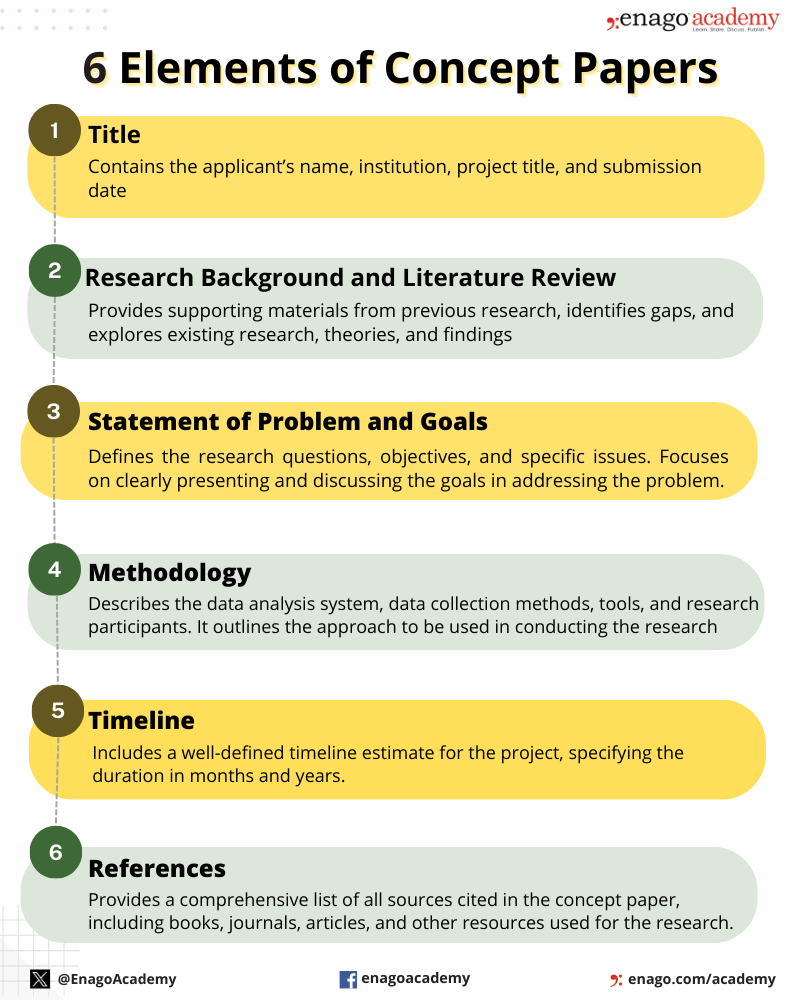

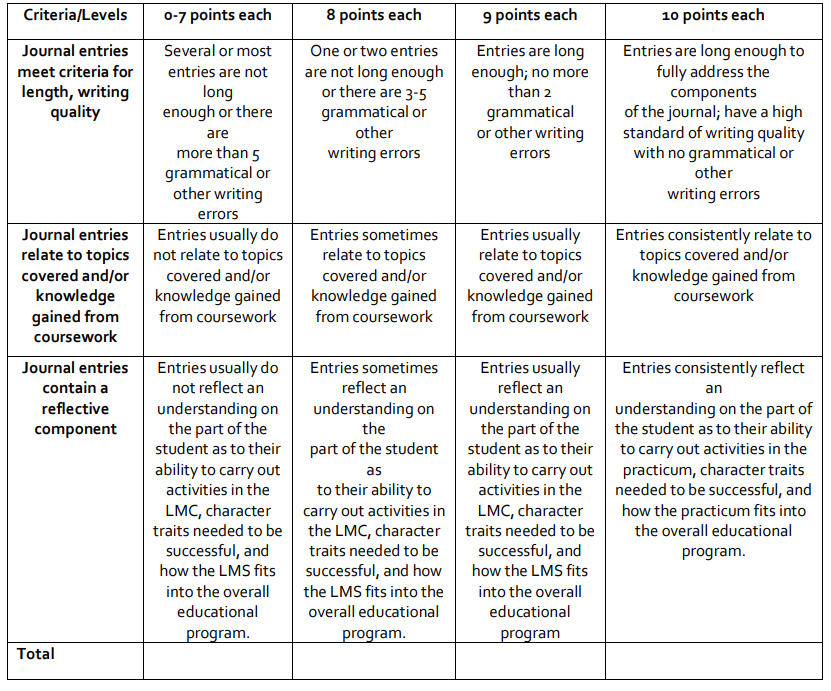

Key elements of a concept paper include the title page , background , literature review , problem statement , methodology, timeline, and references. It’s crucial for researchers seeking grants as it helps evaluators assess the relevance and feasibility of the proposed research.

Writing an effective concept paper in academic research involves understanding and incorporating essential elements:

How to Write a Concept Paper?

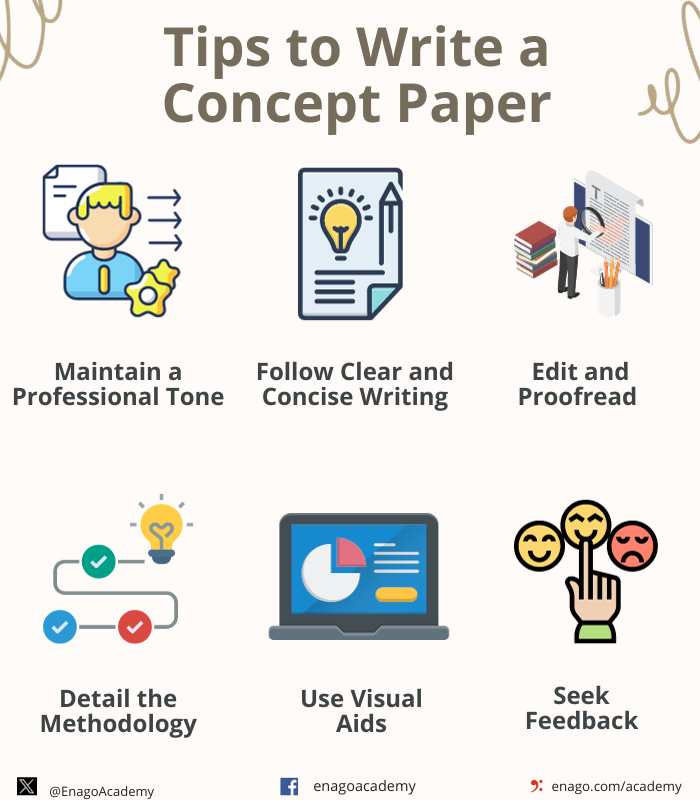

To ensure an effective concept paper, it’s recommended to select a compelling research topic, pose numerous research questions and incorporate data and numbers to support the project’s rationale. The document must be concise (around five pages) after tailoring the content and following the formatting requirements. Additionally, infographics and scientific illustrations can enhance the document’s impact and engagement with the audience. The steps to write a concept paper are as follows:

1. Write a Crisp Title:

Choose a clear, descriptive title that encapsulates the main idea. The title should express the paper’s content. It should serve as a preview for the reader.

2. Provide a Background Information:

Give a background information about the issue or topic. Define the key terminologies or concepts. Review existing literature to identify the gaps your concept paper aims to fill.

3. Outline Contents in the Introduction:

Introduce the concept paper with a brief overview of the problem or idea you’re addressing. Explain its significance. Identify the specific knowledge gaps your research aims to address and mention any contradictory theories related to your research question.

4. Define a Mission Statement:

The mission statement follows a clear problem statement that defines the problem or concept that need to be addressed. Write a concise mission statement that engages your research purpose and explains why gaining the reader’s approval will benefit your field.

5. Explain the Research Aim and Objectives:

Explain why your research is important and the specific questions you aim to answer through your research. State the specific goals and objectives your concept intends to achieve. Provide a detailed explanation of your concept. What is it, how does it work, and what makes it unique?

6. Detail the Methodology:

Discuss the research methods you plan to use, such as surveys, experiments, case studies, interviews, and observations. Mention any ethical concerns related to your research.

7. Outline Proposed Methods and Potential Impact:

Provide detailed information on how you will conduct your research, including any specialized equipment or collaborations. Discuss the expected results or impacts of implementing the concept. Highlight the potential benefits, whether social, economic, or otherwise.

8. Mention the Feasibility

Discuss the resources necessary for the concept’s execution. Mention the expected duration of the research and specific milestones. Outline a proposed timeline for implementing the concept.

9. Include a Support Section:

Include a section that breaks down the project’s budget, explaining the overall cost and individual expenses to demonstrate how the allocated funds will be used.

10. Provide a Conclusion:

Summarize the key points and restate the importance of the concept. If necessary, include a call to action or next steps.

Although the structure and elements of a concept paper may vary depending on the specific requirements, you can tailor your document based on the guidelines or instructions you’ve been given.

Here are some tips to write a concept paper:

Example of a Concept Paper

Here is an example of a concept paper. Please note, this is a generalized example. Your concept paper should align with the specific requirements, guidelines, and objectives you aim to achieve in your proposal. Tailor it accordingly to the needs and context of the initiative you are proposing.

Download Now!

Importance of a Concept Paper

Concept papers serve various fields, influencing the direction and potential of research in science, social sciences, technology, and more. They contribute to the formulation of groundbreaking studies and novel ideas that can impact societal, economic, and academic spheres.

A concept paper serves several crucial purposes in various fields:

In summary, a well-crafted concept paper is essential in outlining a clear, concise, and structured framework for new ideas or proposals. It helps in assessing the feasibility, viability, and potential impact of the concept before investing significant resources into its implementation.

How well do you understand concept papers? Test your understanding now!

Fill the Details to Check Your Score

Role of AI in Writing Concept Papers

The increasing use of AI, particularly generative models, has facilitated the writing process for concept papers. Responsible use involves leveraging AI to assist in ideation, organization, and language refinement while ensuring that the originality and ethical standards of research are maintained.

AI plays a significant role in aiding the creation and development of concept papers in several ways:

1. Idea Generation and Organization

AI tools can assist in brainstorming initial ideas for concept papers based on key concepts. They can help in organizing information, creating outlines, and structuring the content effectively.

2. Summarizing Research and Data Analysis

AI-powered tools can assist in conducting comprehensive literature reviews, helping writers to gather and synthesize relevant information. AI algorithms can process and analyze vast amounts of data, providing insights and statistics to support the concept presented in the paper.

3. Language and Style Enhancement

AI grammar checker tools can help writers by offering grammar, style, and tone suggestions, ensuring professionalism. It can also facilitate translation, in case a global collaboration.

4. Collaboration and Feedback

AI platforms offer collaborative features that enable multiple authors to work simultaneously on a concept paper, allowing for real-time contributions and edits.

5. Customization and Personalization

AI algorithms can provide personalized recommendations based on the specific requirements or context of the concept paper. They can assist in tailoring the concept paper according to the target audience or specific guidelines.

6. Automation and Efficiency

AI can automate certain tasks, such as citation formatting, bibliography creation, or reference checking, saving time for the writer.

7. Analytics and Prediction

AI models can predict potential outcomes or impacts based on the information provided, helping writers anticipate the possible consequences of the proposed concept.

8. Real-Time Assistance

AI-driven chat-bots can provide real-time support and answers to specific questions related to the concept paper writing process.

AI’s role in writing concept papers significantly streamlines the writing process, enhances the quality of the content, and provides valuable assistance in various stages of development, contributing to the overall effectiveness of the final document.

Concept papers serve as the stepping stone in the research journey, aiding in the crystallization of ideas and the formulation of robust research proposals. It the cornerstone for translating ideas into impactful realities. Their significance spans diverse domains, from academia to business, enabling stakeholders to evaluate, invest, and realize the potential of groundbreaking concepts.

Frequently Asked Questions

A concept paper can be defined as a concise document outlining the fundamental aspects of a grant proposal such as the initial ideas, objectives, and theoretical framework of a proposed research project.

A good concept paper should offer a clear and comprehensive overview of the proposed research. It should demonstrate a strong understanding of the subject matter and outline a structured plan for its execution.

Concept paper is important to develop and clarify ideas, develop and evaluate proposal, inviting collaboration and collecting feedback, presenting proposals for academic and research initiatives and allocating resources.

I got wonderful idea

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Career Corner

- Trending Now

Recognizing the signs: A guide to overcoming academic burnout

As the sun set over the campus, casting long shadows through the library windows, Alex…

- Diversity and Inclusion

Reassessing the Lab Environment to Create an Equitable and Inclusive Space

The pursuit of scientific discovery has long been fueled by diverse minds and perspectives. Yet…

- AI in Academia

Simplifying the Literature Review Journey — A comparative analysis of 6 AI summarization tools

Imagine having to skim through and read mountains of research papers and books, only to…

- Reporting Research

How to Improve Lab Report Writing: Best practices to follow with and without AI-assistance

Imagine you’re a scientist who just made a ground-breaking discovery! You want to share your…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

We use cookies on this site to enhance your experience

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

A link to reset your password has been sent to your email.

Back to login

We need additional information from you. Please complete your profile first before placing your order.

Thank you. payment completed., you will receive an email from us to confirm your registration, please click the link in the email to activate your account., there was error during payment, orcid profile found in public registry, download history, understanding and developing a concept paper.

- Charlesworth Author Services

- 15 December, 2021

A concept paper, simply put, is a one- to two-page written document describing an idea for a project . At this stage, there is no need to flesh out details, but rather just introduce the overall rationale of the project, how it’ll be carried out and the expected outcomes. There is no hard rule as to how this should be structured, but below are some tips on what to include and why to include them.

Discuss the rationale

The need for the project is an important aspect to address, and is often something a funding body might look for when considering funding a project. A concept paper might be the first thing a funding round requests to get an idea of what the project is all about. So make sure that it includes:

- Importance of the work being proposed

- What the impact (not the same as ‘ impact factor ’ – see later below) will be

- How the outcomes of your project might meet or respond to the need

- Priorities of your intended audience

Outline your methodology and procedures

Your overall methodology , i.e. how you intend to approach your work, should be outlined here to give your reader an idea of how you propose to achieve your research objectives. Mentioning the proposed methodology in advance allows them to conduct an independent evaluation into whether it is a valid approach.

Further, you should highlight some exciting, specific procedures or methods that you might be especially well-placed to perform. For example, your institute may have a specific piece of equipment, or you may have access to very high quality expertise. This will inspire confidence in the review panel that you are well-positioned to take the project on.

Describe the potential impact

Impact is a term often thrown around in research circles, usually relating to the ‘impact factor’ of a journal. Impact in this instance does not refer to that. The impact that you should be describing here is the real-world impact of your work.

Will your idea or innovation change people’s lives? Will it save the taxpayer money? How will it do those things?

Make sure you describe impacts that go beyond discovering something new to shaking up your research community.

A concept paper is a loose framework by which you are able to quickly communicate an idea for a piece of work you might want to do in the future. At the very least, it can help you put ideas to paper and look at them as a whole, allowing you to critically assess what is needed to make it a reality. In the best case scenario, a concept paper might be used to advance your grant applications or attract investment for your idea. Whatever you are using it for, it is a valuable piece of writing that can help you formalise your idea and make it a reality.

Read next (second) in series: Writing a successful Research Proposal

Maximise your publication success with Charlesworth Author Services.

Charlesworth Author Services, a trusted brand supporting the world’s leading academic publishers, institutions and authors since 1928.

To know more about our services, visit: Our Services

Share with your colleagues

Related resources.

Writing a successful Research Proposal

Charlesworth Author Services 08/03/2022 00:00:00

Concept Paper vs. Research Proposal – and when to use each

Preparing and writing your PhD Research Proposal

Charlesworth Author Services 02/08/2021 00:00:00

Related webinars

Bitesize Webinar: Writing Competitive Grant Proposals: Module 1- Unpacking the Request for Proposals

Charlesworth Author Services 09/03/2021 00:00:00

Bitesize Webinar: Writing Competitive Grant Proposals: Module 2- Choosing the Right Funder

Bitesize Webinar: Writing Competitive Grant Proposals: Module 3- Structuring the Proposal

Bitesize Webinar: Writing Competitive Grant Proposals: Module 4- Developing a Grant Budget

How to write the Rationale for your research

Charlesworth Author Services 19/11/2021 00:00:00

A guide to finding the right Funding Agency for your project

Charlesworth Author Services 27/01/2021 00:00:00

Difference between Methodology and Method

Charlesworth Author Services 15/12/2021 00:00:00

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.2: Introduction to Humanities Overview

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 88996

- Lori-Beth Larsen

- Central Lakes College

This course is an introductory survey of the genres and themes of the humanities. Readings, lectures, and class discussions will focus on genres such as music, the visual arts, drama, literature, and philosophy. As themes, the ideas of freedom, love, happiness, death, nature, and myth may be explored from a western and non-western point of view.

Goal Area: Humanities and Fine Arts

To expand students’ knowledge of the human condition and human cultures , especially in relation to behavior, ideas and values expressed in works of human imagination and thought . Through study in disciplines such as literature, philosophy and the fine arts, students will engage in critical analysis, form aesthetic judgments and develop an appreciation of the arts and humanities as fundamental to the health and survival of any society . Students should have experiences in both the arts and humanities.

Take some time in a notebook or in a digital document, write down some answers to these questions. As you do, think about your experiences and thoughts. Write down some examples of humanity. You’ll return back to these questions throughout the course, so make sure you save them and add to them as we progress though the class.

What do you know about the human condition and human cultures?

What do you want to know about the human condition and human cultures?

What are the behaviors, ideas and values expressed in works of human imagination and thought?

Is it important to engage in critical analysis and form aesthetic judgments about the arts?

How do we develop an appreciation of the arts and humanities as fundamental to the health and survival of any society?

Goal Area: Global Perspective

To increase students’ understanding of the growing interdependence of nations and peoples and develop their ability to apply a comparative perspective to cross-cultural social, economic and political experiences.

What do cultures around the world contribute to humanity?

What do we see that comes from where?

How can I expand what I value?

What makes these contributions strong?

Essential Questions:

This course is organized around questions instead of answers. I hope, as you answer these questions, you will learn to think critically and your learning will be deep. Primarily, in this class you’ll need to rely on your curiosity. Being curious will be important.

Reflective Learning Journal

Each week as you progress through the lessons, take notes. As you read, listen, and talk about the stuff you’re learning, write down what you’re learning and thinking. You can use these notes to write a reflective learning journal at the end of each week. You might want to take notes on a class discussion as well. You might also be loading a Prezi, a photo of your own art, a video, an essay, or a podcast in this blog.

The reflective journal summarizes the week and should tell about the tasks, learning experiences, activities and opportunities you have been involved in during the week of the report.

Here are directions for creating the reflective learning journal as a blog posting.

Blog Instructions

- If you do not have a gmail account, open an account at: http://mail.google.com/

- Go to http://www.blogger.com

- Click on "Create Your Blog Now"

- Click "Continue" and sign in with your gmail account and password

- Give your blog an appropriate title and a Web address (URL)

- Click "Continue"

- Choose a template (How do you want the background of the blog to look?)

- Click "Start Posting"

- Type in an appropriate title and text; add an appropriate image and Web link with the posting.

- To add a Web link, highlight the text or URL that you want to be the link then click on the icon with the green globe or the word “Link” and type or paste in an appropriate link. Click “OK” then publish the post.

- Click on the “Add Image” icon on the menu; browse and locate an image file (or find an image on the Web); choose a layout then click on “Upload Image”

- Click on “View Blog” to see what your posting looks like; if you wish to edit, click on “Customize” or “Dashboard” to access the Settings option or Posting option to edit posts

- To edit posts or add a new post to your blog, type in your blog address (URL) and login to your account; click on Dashboard link or New Post link or then create a new post (or edit/update an older post) with text, image, and link.

- You can find tutorials for wordpress or blogger.com on youtube.com such as: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ULIUhJSKViE&feature=related

* How to Find and Save Images from the Web

- Go to Google.com

- Type in the relevant term

- Click on “Images” at the top left corner to do an image search

- Under Tools, select “Usage Rights” and “Labeled for Reuse”.

- After you find an appropriate image, click on the image, then click on “See full size image”

- Place the cursor on the image then right click – a menu box will appear

- From the menu box, choose the option “Save Image As…”

- Save the image to your desktop or to a disk

- If your image needs to be cropped or made smaller, there are free tools on the Web such as: http://www.pixlr.com/editor/

- Now the image is ready for you to upload to your blog.

Reflective Journal (30 points)

Self-Reflection Questions for Learning

What were some of the most interesting discoveries I made? About myself? About others?

What were some of my most challenging moments and what made them so?

What were some of my most powerful learning moments and what made them so?

What is the most important thing I learned personally?

What most got in the way of my progress, if anything?

What did I learn were my greatest strengths? My biggest areas for improvement?

What moments was I most proud of my efforts?

What could I do differently the next time?

What's the one thing about myself above all others I would like to work to improve?

How will I use what I've learned in the future?

Humanities Sites

Description of Humanities on Wikipedia: https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Humanities

Outline of the Humanities from Wikipedia: https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Outline_of_the_humanities

Minnesota Humanities Center: https://mnhum.org/

What are the Humanities and Why are they important? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ytR3wxwVBd0

Lumen Learning Introduction to Humanities: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/worldcivilization1/

Chris Abani: On Humanity

Chris Abani tells stories of people: People standing up to soldiers. People being compassionate. People being human and reclaiming their humanity. It's "ubuntu," he says: the only way for me to be human is for you to reflect my humanity back at me.

Organizing Research for Arts and Humanities Papers and Theses

- General Guide Information

- Developing a Topic

- What are Primary and Secondary Sources

- What are Scholarly and Non-Scholarly Sources

- Writing an Abstract

- Writing Academic Book Reviews

- Writing A Literature Review

- Using Images and other Media

Critical Engagement

Note: these recommendations are geared toward researchers in the arts or humanities.

Developing a research topic is an iterative process, even for a short paper. This is a process that emerges in stages, and one which requires critical (but not criticizing) engagement with the evidence, literature, and prior research. The evidence can be an object, an artifact, a historic event, an idea, a theoretical framework, or existing interpretations.

Ultimately, you want to be able to pose a research question that you will then investigate in your paper.

If you are writing a paper for a course, the initial critical ideas and theoretical frameworks may come from your course readings. Pay attention to footnotes and bibliographies in your readings, because they can help you identify other potential sources of information.

As you are thinking about your topic, consider what, if anything, has already been written. If a lot of literature exists on your topic, you will need to narrow your topic down, and decide how to make it interesting for your reader. Regurgitating or synthesizing what has already been said is very unlikely to be exciting both for you and for those who will be reading your wok. If there is little or no literature on your topic, you will need to think how to frame it so as to take advantage of existing theories in the discipline. You may also be able to take advantage of existing scholarship on related topics.

Types of Research Papers

There are two common types of research papers in the arts and humanities: expository and argumentative . In an expository paper you develop an idea or critical "reading" of something, and then support your idea or "reading" with evidence. In an argumentative essay you propose an argument or a framework to engage in a dialog with and to refute an existing interpretation, and provide evidence to support your argument/interpretation, as well as evidence to refute an existing argument/interpretation. For further elaboration on expository and argumentative papers, as well and for examples of both types of essays, check the book titled The Art of Writing About Art , co-authored by Suzanne Hudson and Nancy Noonan-Morrissey, originally published in 2001. Note that particular disciplines in the arts or humanities may have other specialized types of frameworks for research.

Also, remember that a research paper is not "merely an elaborately footnoted presentation of what a dozen scholars have already said about a topic; it is a thoughtful evaluation of the available evidence , and so is, finally, an expression of what the author [i.e., you] thinks the evidence adds up to." [Sylvan Barnet, A Short Guide to Writing About Art (New York: Pearson/Longman, 2005), 238-239.]

If you select a broad topic

If a lot has been written on your topic, perhaps you should consider the following:

- why are you interested in this topic?

- is there something specific you want to address?

- can you offer a different or a more nuanced interpretation?

- is there a specific theoretical or methodological perspective that you would like to apply?

- can you shed more light on specific evidence or detail(s)?

- review scholarship cited in the footnotes/bibliographies of your readings and see if there are lacunae you can address.

If you stick with a broad topic, you run into the danger of over-generalizing or summarizing existing scholarship, both of which have limited value in contemporary arts and humanities research papers. Summarizing is generally useful for providing background information, as well as for literature reviews. However, it should not constitute the bulk of your paper.

If you select a narrow or a very new topic

If you are interested in something very specific or very new, you may find that little has been written about it. You might even find that the same information gets repeated everywhere, because nothing else is available. Consider this an opportunity for you to do unique research, and think of the following:

- is there a broader or a related topic that you can investigate in order to circle back and hone in on your chosen topic?

- can your topic be critically examined within an existing theoretical or methodological framework?

- are you able to draw on another field of study to investigate your topic?

- review scholarship cited in the footnotes/bibliographies of the readings. - in other words, engage in citation chaining.

- if the pertinent readings you find are not scholarly (this is not necessarily a bad thing), evaluate how you can use them to develop a more scholarly and critical context for investigating your topic.

Citing sources

Remember to keep track of your sources, regardless of the stage of your research. The USC Libraries have an excellent guide to citation styles and to citation management software .

- << Previous: General Guide Information

- Next: What are Primary and Secondary Sources >>

- Last Updated: Jan 19, 2023 3:12 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/ah_writing

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 08 February 2024

Integrating the humanities and the social sciences: six approaches and case studies

- Brendan Case ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4277-8075 1 &

- Tyler J. VanderWeele 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 231 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

996 Accesses

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

The social sciences are still young, and their interaction with older siblings such as philosophy and theology is still necessarily tentative. This paper outlines three ways in which humanistic disciplines such as philosophy and theology might inform the social sciences and three in which the social sciences might inform the humanities in turn, proceeding in each case by way of brief “case studies” to exemplify the relation. This typology is illustrative rather than exhaustive, but each of its halves nonetheless roughly tracks the development of a research project in the social sciences and humanities, respectively. In the first direction, (1) the humanities can help the social sciences identify new directions and scope for their inquiry; (2) provide conceptual clarity for constructs that the social sciences elect to study; and (3) enrich & clarify the interpretation of empirical results. Moving in the opposite direction, the social sciences can help (4) furnish new data for humanistic reflection; (5) confirm (or challenge) claims from the humanities; and (6) develop and assess interventions for achieving the goods highlighted by humanistic inquiry.

Similar content being viewed by others

The process and mechanisms of personality change

Joshua J. Jackson & Amanda J. Wright

A precision functional atlas of personalized network topography and probabilities

Robert J. M. Hermosillo, Lucille A. Moore, … Damien A. Fair

Interviews in the social sciences

Eleanor Knott, Aliya Hamid Rao, … Chana Teeger

In 1917, Max Weber famously proclaimed that “the enterprise of science as a vocation is determined by the fact that science has entered a stage of specialization that has no precedent” (Weber, 2004 : p. 7). Weber did not introduce this fragmentation as a cause for lament; on the contrary, he insisted, “Only rigorous specialization can give the scholar the feeling for what may be the one and only time in his life, that here he has achieved something that will last .” Nonetheless, he recognized that scientific specialization posed significant challenges for intellectual work of any ambition or scope: “With every piece of work that strays into neighboring territory…we must resign ourselves to the realization that the best we can hope for is to provide the expert with useful questions of the sort that he may not easily discover for himself from his own vantage point” (Weber, 2004 : p. 7).

This galloping specialization has only accelerated since Weber’s day—by some measures, there are now 176 distinct scientific sub-fields, including astronomy, atmospheric sciences, and automotive engineering (Ioannidis et al., 2019 ). And the humanities have by no means been immune from the pressure to specialize: particularly in the Anglosphere, it is rare today for a humanist—out of expedience, we’ll restrict ourselves to philosophers and theologians—to publish on more than a handful of her discipline’s classic problems, both from the sheer mass of publications in even relatively narrow sub-fields, and owing to the academic incentives for hiring and promotion. Not that all philosophers and theologians are happy about this situation: both disciplines are full of internal hand-wringing about the fragmentation of their sub-disciplines and the intellectual impoverishment it imposes. Footnote 1

In this situation of deep, Weberian specialization, it is perhaps no great surprise that even sciences closely adjacent to the humanities—“social sciences,” such as psychology, sociology, or social epidemiology—have had relatively little time or energy for opening a conversation with their seemingly strange neighbors. Some corners of the humanities—philosophy in particular—have made relatively greater progress in engaging with the findings of the social sciences, but on the whole, the lines of communication between these disparate disciplines have been few and fragmentary.

The social sciences are still young, and their interaction with older siblings such as philosophy and theology is still necessarily tentative. However, a broad paradigm for dialogue in some specific areas is now coming into focus, guided by the broad conviction that (as Mark Alfano nicely put it, riffing on Kant’s famous line about intuitions and concepts): “Moral philosophy without psychological content is empty, whereas psychological investigation without philosophical insight is blind” ( 2016 : p. 1). Footnote 2 Where Weber had proposed a clean division between the sciences’ “facts” and the humanities’ “values”—“non-overlapping magisteria,” to borrow a phrase from Gould ( 1997 )—Alfano’s maxim points to the essential complementarity of the humanities’ and social sciences’ distinctive methods. If humanists make claims about the actual world, they must do so responsibly, with due attention to specialists’ empirical inquiry. And conversely, social scientists must recognize that their concepts are rarely pellucid, their measurements are always partial, and their data is never self-interpreting, so that they can frequently profit from the analytical rigor and hermeneutical insight in which the humanities specialize.

Below, we outline three ways in which humanistic disciplines such as philosophy or theology might inform the social sciences and three in which the social sciences might inform them in turn, proceeding in each case by way of brief “case studies” to exemplify the relation. Our choice of philosophy and theology is doubly practical: these are the two humanistic disciplines in which we are most at home, as well as fields in which there has already been a fair amount both of engagement with the social sciences and methodological reflection on that engagement. These could and should be expanded by reference to other corners of the humanities. For a sketch of how a dialogue of this sort might proceed between the fields of economics and literature in particular, cf. Morson and Shapiro ( 2017 ). So too, we have chosen case studies that both reflect our own areas of expertise and furnish clear instances of the kinds of interdisciplinary interaction that we hope to highlight in each section.

This typology is illustrative rather than exhaustive, but each of its halves nonetheless roughly tracks the development of a research project in the social sciences and humanities, respectively. In the first direction, (1) the humanities can help the social sciences identify new directions and scope for their inquiry; (2) provide conceptual clarity for constructs that the social sciences elect to study; and (3) enrich & clarify the interpretation of empirical results. Moving in the opposite direction, the social sciences can help (4) furnish new data for humanistic reflection; (5) confirm (or challenge) claims from the humanities; and (6) develop and assess interventions for achieving the goods highlighted by humanistic inquiry.

Guiding inquiry: life satisfaction and eudaimonia

The humanities can help guide, direct, and motivate the research inquiries of the various social sciences. For instance, recent debates over the measurement of well-being have been explicit, if often imperfectly, influenced by ancient moral philosophy, especially in the “eudaimonistic” tradition. We will argue that although the drawing upon Aristotle’s understanding of flourishing has clearly already shaped empirical well-being research, deeper engagement with his actual views might enrich empirical work yet further. More specifically, we’ll consider two cases of this kind of philosophical influence on psychometrics (Helliwell, 2021 ; Ryff et al., 2021 ), the former drawing on classical eudaimonism to defend a central role for the assessment of “life satisfaction” in well-being research and in global development work, and the latter doing so to contrast “hedonic well-being” with “eudaimonic well-being” or “challenged thriving.”

John Helliwell is the editor of the UN’s World Happiness Report, an annual analysis of subjective well-being in 160 countries (Helliwell, 2021 ). In the Report, “happiness” is assessed using measures of self-reported experiences of positive and negative emotion and “life evaluation,” assessed by asking respondents where they would place their lives (ranging from “best” to “worst”) on a ladder (cf. Cantril, 1965 ).

Helliwell ( 2021 ) has recently drawn on Aristotle, in particular, to argue that measures of life evaluation or life satisfaction ought to be given priority over other measures of well-being, such as GDP per capita or in contemporary policy debates. He argues that the most important tools for measuring happiness are “the evaluations that individuals make of the quality of their own lives,” and goes on to quote Julia Annas (from her classic survey of ancient ethics) as noting that “ancient ethical philosophy ‘gets its grip on the individual at this point of reflection: am I satisfied with my life as a whole, and the way it has developed and promises to develop?’” (2021: 29, quoting Annas, 1993 : p. 28). This intuition motivates Aristotle’s startling insistence, citing Priam’s tragic death amid the downfall of Troy, that even a flourishing life cannot be regarded as “supremely blessed ( makarios )” unless it comes to a good end (1934: 1.9.11, p. 47). For Helliwell, measures of “life satisfaction” are Aristotelian precisely to the extent that they invite respondents to consider, not merely their current or recent mood (as questions about “happiness” might suggest), but their lives as a whole.

Helliwell notes two further senses in which life-satisfaction research is broadly Aristotelian. First, he suggests that life satisfaction measures follow Aristotle in allowing “that a good life is likely to combine elements of the viewpoints later identified as Epicurean and Stoic,” i.e., to involve both external goods and internal goods such as character and virtue (Helliwell, 2021 : 30, cf. Aristotle, 1934 : 1.8.15–16, p. 43). And second, Aristotle insisted “that the right answers [to questions about the good life] require evidence as much as introspection” (Helliwell, 2021 : p. 30, citing Aristotle, 1934 : 1.8.9–13, p. 41).

However “Aristotelian” Helliwell’s approach might be an inspiration, though, Aristotle would hardly have approved of mass surveys of life satisfaction as a supposedly adequate tool for gauging the flourishing of an individual or population. After all, he took it that most people (“the many”) mistakenly believed that the good life consists of pleasure (1934: 1.4.1–3, p. 11). Aristotle is unapologetically elitist in insisting that a flourishing life is characterized most fundamentally by “the active exercise of one’s soul’s faculties in conformity with virtue,” or (put the same point in somewhat different words) “in conformity with reason” (1934: 1.7.15, p. 33).

To his credit, Helliwell is up-front about discounting Aristotle’s “emphasis on excellence and purpose,” but an account of well-being that brackets the centrality of virtue is not Aristotelian, nor meaningfully eudaimonist in any classical sense. Indeed, precisely because they accepted the intuitive requirement that the human good must be good for one’s life as a whole, and not simply for the passing moment, even the supposedly hedonistic Epicureans had to embrace revisionary accounts of pleasure. For Epicurus, the pleasures that are really pleasant turn out to be the refined pleasures of intellectual engagement and virtuous friendship, which he summarized as a state of being undisturbed in the soul ( ataraxia ) (Annas, 1993 : pp. 334–50).

A more eudaimonistic—and arguably more adequate—approach to assessing well-being would distinguish in a finer-grained way among distinct domains—between, say, the external goods of health and wealth and the internal goods of character, meaning, and achievement—and would perhaps discount the former in view of the relatively greater importance of the latter (Symons and VanderWeele, 2023 ). This is precisely what Ryff et al. ( 2021 ) propose in distinguishing between “eudaimonic well-being” or “challenged thriving,” and “hedonic well-being” (defined to include life satisfaction, positive affect, and the absence of negative affect). They take the former category to assess the dimensions of flourishing which they claim all the ancient eudaimonists gave pride of place, such as “autonomy,” “personal growth,” “positive relations with others,” or “purpose in life” (2021: pp. 99–100; cf. also Ryff’s earlier work on this topic, in Ryff 1989 or Ryff & Keyes, 1995 ). This approach has the advantage of teasing apart two relatively distinct domains of flourishing, which differ significantly both in their demographic distribution (Ryff et al., 2021 : pp. 101–109) and in their effects on other domains, such as physical health (Ryff et al., 2021 : pp. 110–115).

Nonetheless, the absence from their description of the eudaimonic well-being of the central concept of classical eudaimonism, namely the virtues, is striking. Neither Aristotle, Zeno, nor Epicurus would have regarded autonomy or purpose in life as intrinsic goods in themselves; Hitler, after all, enjoyed a high degree of both for much of his public life, but we presumably would not want to say that he was flourishing in that period. Rather, eudaimonists would regard all of those qualities as valuable to the extent that they were shaped by the virtues, paradigmatically of wisdom, courage, temperance, and justice. We might thus hypothesize that measures of “eudaimonic well-being” would be more valuable—and more predictive of other well-being outcomes—to the extent that they incorporated, not merely the thin “character strengths” beloved of much recent psychology, but the more robust excellences of character captured in the classical conception of virtue (cf. Ng and Tay, 2020 ; VanderWeele, 2022 ).

In short, the empirical study of well-being has clearly been greatly facilitated by attention to the insights of ancient moral philosophy, particularly the philosophy of Aristotle, who emphasized the diversity of goods that compose a flourishing life. Nonetheless, well-being assessment and subsequent empirical research would be more properly “eudaimonic” to the extent that it incorporated sustained attention to the virtues as such, and not merely to some of the qualities with which they are associated. Insights from the humanities—from philosophy, from theology, from history—have and almost inevitably will continue to inform, motivate, and direct research in the empirical social sciences.

Clarifying constructs: hope and optimism

For a second way in which the humanities might contribute to the social sciences, consider their role in shaping construct definitions of traits or behaviors, which profoundly shape empirical research, but are sometimes under-theorized or imprecisely defined by the social scientists who employ them. We should of course heed Aristotle’s caution not to insist on greater precision in any inquiry than its subject-matter admits (Aristotle, 1934 : 1.3.1–2, p. 7); the boundaries between human emotions or dispositions will typically be fuzzier than those distinguishing atoms in the chemical table of elements. Nonetheless, in avoiding the error of artificial precision, we ought not to license the opposite error of avoidable vagueness. For example, the terms “hope” and “optimism” are sometimes used interchangeably in ordinary language, which has arguably obscured social-scientific inquiry on these topics as well. Research on hope has been dominated by Snyder’s influential definition of hope as “the cognitive energy and pathways for goals” ( 1995 : p. 355). The items in Snyder’s accompanying measure of hope include the following: “There are lots of ways around any problem”; “I’ve been pretty successful in life”; or “I meet the goals that I set for myself.”

Notice that all of these items imply a strong expectation on the part of the respondent that the future will in fact turn out well, or even that it already has, combined with a strong sense that the respondent has the capacities and drive to bring about the desired future (Snyder, 1995 : p. 357). While Snyder explicitly distinguishes his conceptualization of hope from the related trait of “optimism,” Footnote 3 his construct definition and many of the items in his measure of hope in fact seem principally to capture an optimistic future outlook, albeit with a high degree of “self-efficacy.” Snyder’s hopeful person exemplifies what we might call “warranted optimism” or “agential optimism,” in contrast with “unwarranted” or “passive optimism.”

Snyder’s conflation of hope with an optimistic outlook has a long history. In the 17th century, René Descartes, one of the founding figures of modern European philosophy, described hope as “a disposition of the soul to be convinced that what it desires will come to pass” ( 1989 : p. 110). Snyder might seem to be on firm ground, then, in identifying hope as the confidence in one’s ability to identify the pathways to some goal, but this definition arguably screens out the most important aspects of the virtue of hope, which, as Dickinson ( 1983 ) put it, “sweetest in the gale is heard.” What about situations in which no pathway to success is evident, and so no confidence is warranted? What about when the diagnosis is terminal or the jail sentence is life without parole?

It is striking, for instance, how prominent the theme of “hope” is in Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning , his memoir of his time in Auschwitz, notwithstanding his frank assessment of how bleak his future prospects were, once he was inside the concentration camp. “I said,” Frankl wrote, “that to the impartial the future must seem hopeless…Each of us could guess for himself how small were his chances of survival…But I also told [the others] that, in spite of that, I had no intention of losing hope and giving up” ( 1989 : p. 103). Frankl would have been out of his mind to affirm that “there [were] lots of ways around any problem” in Auschwitz; to any sane person, by far the likeliest outcome was misery and torture ending only with his murder. Nonetheless, Frankl was determined to fix his mind and will on a possible, future good, and that disposition helped sustain him through the agonizing years of his captivity. It would have been cruel mockery to tell Frankl to believe that he would escape, but the hope he cultivated did not require that belief; indeed, it was more , not less, truly hopeful for the bleakness of his situation.

If Frankl’s conception of hope as a disposition to be cultivated even, and perhaps especially, in the face of overwhelming odds and seemingly unendurable suffering makes no sense in light of the Descartes-Snyder model of hope, it fits well with the theory of hope developed by Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274). In one of the philosophical passages of his Summa Theologiae , Aquinas distinguished hope’s particular object with reference to four conditions: “First, that it is something good…Secondly, that it is future…Thirdly, that it must be something arduous and difficult to obtain, for we do not speak of anyone hoping for trifles, which are in one’s power to have at any time…Fourthly, this difficult thing is something possible to obtain: for one does not hope for that which one cannot get at all” ( 1888 : 1–2.40.1). For Aquinas, then, hope is the desire for a future good which is difficult but possible to obtain. We can be hopeful in Aquinas’s (or Dickinson’s) sense about probable outcomes, to be sure, but hope never matters more to us than when the prognosis is grim, the outlook poor, the options few.

Incorporating philosophical and theological insights into social-scientific research would better conceptually distinguish hope from optimism. This greater clarity could give rise to more precise construct definitions and thus also more adequate and distinct measure development and so enable better empirical research on these topics. The use of philosophical resources to refine construct definitions and to clarify the logical relations between those definitions and survey items designed to capture them may have considerable potential to improve measure development in the social sciences. Footnote 4 The humanities have a real contribution to make in providing conceptual clarity for constructs that the social sciences aim to study.

Enriching interpretation: explaining and understanding marriage

The humanities can also enrich the interpretation of insights from the social sciences, by alerting them to the intrinsic limitations of their methods and bringing other disciplinary insights. Wilhelm Dilthey proposed long ago that we distinguish between “explanation ( Erklärung )” and “understanding ( Verstehen ).” Dilthey’s paradigms for explanation are drawn from the natural sciences’ penchant for reduction: in physics, the mechanics or chemistry of medium-sized dry goods are explained in terms of interacting elementary particles, and appeals to such obscure entities are justified by their adequacy in simplifying both theory and description ( 2002 : p. 107).

Much work in contemporary social science aspires to this sort of rigorous—indeed, predictive—reduction. For instance, consider the question, “Why has monogamy prevailed over polygamy as a marriage form?” This question, among many others, is given illuminating treatment by Henrich ( 2020 ). As Henrich shows, there are quite practical reasons for the gradual pressure away from polygamy (especially “polygyny,” one husband with multiple wives) and toward monogamy. This is above all a function of polygyny’s “math problem”: when men are allowed to take multiple wives, elite men tend to take many (think of King Solomon’s 700 wives and 300 concubines, 1 Kings 11:3), leaving a glut of less successful men who can’t find even one spouse (Henrich, 2020 : pp. 263–64). This is a dangerous situation, since unmarried men will often be less productive and more prone to reckless or criminal behavior than their married peers, while wives and children in polygynous families receive less investment of effort and concern from their husbands and spouses than those in monogamous families (Henrich, 2020 : pp. 268–84). Monogamy solves the math problem more elegantly than polygyny can. Henrich’s game-theoretic account of marriage’s slow evolution toward monogamy provides a paradigm of an impersonal account: it offers a vision of marriage from the outside, as an adaptive strategy on which societies naturally converge over time without any deliberate or reflective understanding. Most crucially, this kind of bottom-up explanation makes no reference to any perspective from within the institution of marriage itself.

This sort of reductive social-scientific account explains a great deal—but not everything. Indeed, much that lies closest to the heart of human life is screened out entirely by its method of “explanation,” which Dilthey opposed to “understanding ( Verstehen ),” an incommensurable and equally important mode of inquiry concerned with “spiritual ( geistlich ) objects” which are grounded in “lived experience ( Erlebnis )” and which are proper to the human sciences or “ Geisteswissenschaften (sciences of mind).” Footnote 5 The natural sciences aspire to a “view from nowhere,” as Nagel ( 1989 ) put it, an account of the world from which subjectivity has been expunged; they can depict only what McDowell called “the space of nature…the realm of law” ( 1996 : xiv–xv). Restricting accounts of human psychology and behavior to this sort of reductive explanation encourages what Mary Midgley called the spirit of “nothing-buttery,” in which apparently reasonable, noble, or loving acts are debunked as “nothing but” lust, greed, or the libido dominandi (Midgley, 2005 : p. 203). This is that “cold philosophy,” which Keats lamented must in the end “unweave the rainbow” ( 1820 : p. 41).

Happily, we are not limited to Dilthey’s Erklärung , for there are also the Geisteswissenschaften , which concern themselves with a subjectivity-saturated world, Sellars’s ( 1963 ) “logical space of reasons,” in which one is “able to justify what one says.” As Dilthey puts it, “the procedure of understanding is grounded in the realization that the external reality that constitutes its objects is totally different from the objects of the natural sciences. Spirit has objectified itself in the former, purposes have been embodied in them, values have been actualized in them” ( 2002 : p. 141).

More recently, Roger Scruton ( 2014 ) made the distinction between “explaining” and “understanding”—interpreted in terms of a “cognitive dualism,” and rooted variously in the thought of Dilthey, Sellars, and Kant, among others—central to his entire philosophical project. “Persons are objects,” Scruton notes, “but they are also subjects…This means that, while we often attempt to explain people in the way we explain other objects in our environment—in terms of cause and effect, laws of motion, and physical makeup—we also have another kind of access to their past and future conduct. In addition to explaining their behavior, we seek to understand it” ( 2014 : p. 32).

As Scruton argued elsewhere, the distinction between explanation and understanding is particularly crucial in the case of an institution such as marriage: “Anthropologists can tell us why the vow of love is useful to us and why it has been selected by our social evolution. But they have no special ability to trace its roots in human experience or to enable us to understand what happens to the moral life when the vow disappears and erotic commitment is replaced by the sexual handshake” ( 2006 : p. 13). Even if the impersonal, evolutionary account succeeds in explaining why monogamy should eventually prevail within populations of sexually dimorphous primates with slow-developing children, that in itself provides us no access to the reasons for which men and women enter into marriage, and which sustain their commitment to it. In this case, neglecting the work of understanding entirely in favor of explanation will be, not merely incomplete, but fundamentally misleading.

To begin, an account that reduces human behavior to genetically driven appetite cannot make sense of basic facts about the human experience of sexual desire. As Scruton emphasizes, the experience of sexual desire is arguably not in the first instance “a desire for sensations,” notwithstanding the determination of much empirical psychology to treat it as such. Footnote 6 Rather, it is a desire for a person —not for “his or her body, conceived as an object in the physical world, but the person conceived as an incarnate subject, in whom the light of self-consciousness shines and who confronts me eye to eye, and I to I” ( 2006 : p. 15). It is precisely because sexual desire properly aims at a communion of subjects that it takes as its focus, not the genitals, but the face, and particularly the eyes, the soul’s windows. It is also why we instinctively class rape, not with being spat upon, but with murder—it is not the unwanted contact with another’s bodily fluids that makes it a desecration, but the forcible reduction of another’s free personhood to the status of a mere, passive object ( 2006 : p. 17).

The anthropologist’s perspective allows us to explain why lifelong monogamy is an advantageous reproductive strategy, but the internal perspective allows us to understand the reasons that make that institution intelligible to its members. In this case, the two perspectives are not merely complementary, but mutually reinforcing. As Scruton observes, while “the inner, sacramental character of marriage is reinforced by its external function” of socializing sex and nurturing children, it is equally true that the external function is sustained by the internal commitments, so that “societies in which the vow of marriage is giving way to the contract for sexual pleasure are also rapidly ceasing to reproduce themselves” ( 2006 : pp. 19, 24).

Much more could be said on this controversial topic. However, it is clear that by appealing to different levels of explanation and, in particular, those concerning teleology and the reasons agents give for commitments and actions, our understanding of empirical research can be enriched. It is of course true that some social scientists (e.g., anthropologists engaged in the “thick descriptions” characteristic of participant-observer research) are also skilled practitioners of Dilthey’s Verstehen ; particular methods need have no necessary or non-transferrable connection to particular academic disciplines. In principle, then, the exchanges we describe in this section could occur within the social sciences, for instance between anthropology and psychology or economics. (For a proposal along these lines, cf. Haidt, 2012 : p. 143). Nonetheless, it is equally true that many humanists specialize in the descriptions of forms of life which Dilthey singled out as the hallmark of Verstehen , and that social scientists principally engaged in Erklärung neglect the other’s contributions at their own peril. While we have given a single example here concerning appeal to more philosophical forms of reasoning, likewise interpretation of data from the empirical social sciences can be enriched by a deeper and more philosophical exposition of relevant concepts, by theological frameworks, and by historical understanding and context.

Furnishing new data: situationism and the virtues

Let’s now turn to three ways in which the social sciences might inform the work of the humanities, first by furnishing data and evidence that may itself prompt new directions of reflection and inquiry within the humanities. In the section “Guiding Inquiry” above, we saw that moral philosophy, especially but by no means only in the West, has been centrally concerned with virtues and vices as key dimensions of a flourishing life (Dahlsgaard et al., 2005 ). In recent decades, however, findings from social psychology have sparked a wide-ranging debate among philosophers about how common the virtues and vices actually are. The “situationist” literature in social psychology, as it has come to be called, has been construed by many psychologists and philosophers alike as challenging the notion that most people possess stable virtues or vices, or even global character traits of any sort. Footnote 7

The situationist literature is vast and varied, but a few well-established findings will suffice to give its flavor:

Helping : Experimental subjects are much less likely to help a distressed stranger if they are being hurried by a third party (Darly and Batson, 1973 ) or are sitting with a third party who refuses to help (Latané and Rodin, 1969 ), but much more likely to help if they have just emerged from a bathroom or found a dime in a phone booth (Isen and Levin, 1972 ).

Generosity : Psychologists visited a Moroccan marketplace and had volunteers play cooperation games amid the stalls, either during the regular call to prayer (obligatory for all Muslims five times daily) or between calls. “During the call to prayer, 100 percent of the shopkeepers gave all of the money [they had won] to charity. At other times, the percentage of participants giving it all to charity dropped to 59 percent” (Henrich, 2020 : p. 126, discussing Duhaime, 2015 ).

Harming : Stanley Milgram found that a large majority of his test subjects could be pressured by a white-coated “supervisor” into administering what they (wrongly) believed to be painful electric shocks to a total stranger (in fact an actor bellowing convincing howls of agony and pleas for mercy), and that, across several trials, 65% were even willing to administer a deadly, 450-volt shock (Milgram, 1974 ). Footnote 8 Nonetheless, though participants in Milgram’s experiments could be pressured into cruel behavior, hardly any embraced it with verve—in other versions of Milgram’s experiment in which no pressure was applied to administer shocks, almost none did (Miller, 2016a : p. 97).

All of these findings are examples of the wider field of “social priming,” and so need to be handled carefully: priming experiments have been a central focus of the recent “replication crisis” in psychology, and many seem to presuppose rather implausible accounts of human motivation. Footnote 9 Nonetheless, in the cases above, the experiments (or close approximations to them) have been replicated, and the underlying mechanisms seem plausible: for instance, it is hardly a novel idea that social pressure, especially from authority figures or their metonymies (e.g., religious symbols), profoundly shapes human behavior for good and for ill, even if most of us typically underestimate how strongly such external factors influence us.

The data and experiments provided important new material for philosophical reflection and debate. In the late 1990s, two philosophers, Gilbert Harman and John Doris, launched the situationist debate in moral philosophy by arguing that this sort of finding provided strong evidence against the existence of any global character traits, including virtues or vices. In their view, most human behavior is instead the product of situational factors, many of them unnoticed by the agents in question (Harman, 1999 ; Doris, 2002 ; Alfano, 2014 ). A more moderate situationism has been developed by Christian Miller, for whom situationist findings indicate that most of us possess neither virtues nor vices, but rather what he calls “mixed traits,” which incline us to, e.g., honesty in some highly specified situations, and to dishonesty in others (Miller, 2013 : p. 111). Miller argues that situational factors activate “surprising dispositions” in each of us, such as a disposition to “harm others in order to obey the instructions of a legitimate authority” (activated in the Milgram experiments) or to help others in order to alleviate embarrassment (activated in the bathroom experiment) (Miller, 2016b : p. 61).

Counter-intuitive as it might seem, the thesis that virtues and vices are rare was a relatively mainstream position in the ancient and medieval worlds. Aristotle, for instance, took for granted that the virtues are rare, insisting that “the many… do not abstain from bad acts because of their baseness but through fear of punishment” ( 1934 : 1179b7–13; Curzer, 2012 : p. 333). And, as Thomas Osborne notes, “Following Aristotle, Thomas [Aquinas] thinks although some agents are virtuous and others are vicious, there are many agents who are neither. Continent agents act well, but they think about what they should not do because their desires are disordered. Incontinent agents act poorly, but they are generally aware of what they should do” (Osborne, 2014 : p. 77, cf. Aquinas 1953: q. 3, art. 9, ad 7).

Why then has the situationist literature struck such a nerve among contemporary moral philosophers, many of whom are reluctant to take refuge, with Aristotle and Aquinas, in the rarity of the virtues as a response to situationism? A key factor in motivating the situationist debates is perhaps the democratic and egalitarian convictions of most philosophers in the modern West. These convictions come to the surface of Robert Adams’s seminal contribution to this debate: “If I do not adopt [the rarity response to situationism], that is because I believe it is important to find moral excellence in imperfect human lives and because I disagree with ancient views about the kind of integration human virtue can and should have” ( 2006 : p. 119).

Whatever the precise motives for their reluctance, some social psychologists and philosophers alike have nonetheless reasonably cautioned against over-interpreting the results of situationist experiments. Further consideration of the data and results of the empirical research can once again help guide philosophical reflection. In an important meta-analysis of 286 experimental studies of helping behavior, for instance, Lefevor et al. ( 2017 ) observed that, while there is substantial evidence that situational factors influence rates of helping, those factors can only explain part of the differences across individuals. So, while “there was a significant difference in the odds of helping between experimental and control groups (OR = 2.25, k = 286, 95% CI [2.08, 2.43], z = 20.41, p < 0.001)” (indicating that situational factors played an important role in shaping helping behavior), roughly 42% of participants across all control groups still engaged in helping behavior without any specifiable situational prompt. Moreover, even in experimental settings designed to discourage helping behavior (e.g., the unhelpful bystander, the hurrying authority figure), roughly 39% of participants still helped, compared with 58% of participants in the control groups (Levefor et al., 2017 : pp. 240–43). Situational factors clearly influence helping behavior, but by no means determine it.

This sort of mixed result is standard in the situationist literature—recall the aforementioned finding that the call to prayer increased Muslim shopkeepers’ charitable giving to 100%, but did so from a relatively high floor of 59% (cf. p. 17 above). While situational factors or the “surprising dispositions” they activate matter a great deal, they are not the whole story; the experimental evidence for helping behaviors suggests that situations and personal traits—whether an evolved disposition to help conspecifics, a developed virtue of benevolence, or something in-between—both contribute to observed patterns of morally significant behaviors such as helping or charitable giving. Owen Flanagan sums up the implications of these mixed findings as follows: “There are dispositions and there are situations. They interact in complex ways” (2016: p. 49).

The data that have come out of experimental psychology on character and virtue has contributed to our understanding of the prevalence and distribution of the virtues and has informed a lively philosophical debate about the place of the virtues, and of moral character more broadly, within human action. Philosophical and theological reflection on the topic of how to cultivate virtue has tended to rely heavily on a given author’s own experiences or observations (Doris, 1998 : p. 512; Healy, 2014 : pp. 73–99). The social sciences can provide a helpful supplement to anecdotal experience by documenting and describing representative distributions of patterns and behaviors. (For a largely successful interaction along these lines, cf. the essays collected in Snow, 2014 ). More broadly, the empirical social sciences can contribute to, and supplement, knowledge in ways that are useful for reflection and scholarship within the humanities.

Corroborating or disconfirming philosophical and theological claims: religion and public health

Besides furnishing grist for the humanistic mill, the social sciences can also provide evidence for or against a range of empirical claims that humanists are wont to make. For instance, students of religion, both within and without religious communities, naturally take an interest in the effects of various religious practices (e.g., attending corporate worship, communal fellowship and support, the confession of sin, private prayer and Scripture reading, etc.) not only on the believer’s eternal destiny but also on flourishing in the present. For example, Miroslav Volf’s Flourishing ( 2015 ) offers a thoughtful treatment of the ways in which a life of faith can become a pathway to flourishing. Volf emphasizes that each of the great world religions (e.g., Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism, etc.) “teaches that we live our ordinary lives well when we have a purpose that transcends the goods of ordinary life and when this purpose regulates care for the goods of ordinary life” ( 2015 : p. 72).

World religions, then, predict that their followers will generally experience not only transcendent or eternal flourishing, but also “ordinary flourishing” (Volf, 2015 : p. 44). This prediction, however, is in deep tension, Volf notes, with the contention of some students of religion, that, far from upholding the goods of ordinary life, “religion poisons everything” ( 2015 : p. 76, quoting Hitchens, 2007 ). Volf in fact partially concedes this objection, noting, “Religions have a genuine and indispensable gift to give, but they often get corrupted; they malfunction, and the gift turns into poison” ( 2015 : p. 76). These malfunctions can produce religious hypocrites or violent zealots, but in each case, Volf cautions, we must remember that abuses do not abrogate a thing’s proper use ( 2015 : pp. 76–77).

It is of course true that religious communities often betray their own teachings and best aspirations, and true as well that religious practices are vulnerable to “characteristic damage,” the vices to which their virtues leave them vulnerable (cf. Winner, 2018 : 14 et passim ). Nonetheless, Volf’s discussion of this issue leaves an interesting and important question hanging, namely: how does religious practice affect “ordinary flourishing” in general , rather than in its ideals and in its deformations? Without a clear answer to this question, Volf hasn’t refuted the “New Atheists’” challenge so much as dodged it.

Volf’s silence on this point is particularly striking, given that there is a large and growing empirical literature (mostly from Western contexts) on the relation of religious practice to human flourishing. Let’s distinguish, with Volf, among three domains of flourishing: “life being led well” (a virtuous or moral life, we might say); “life going well” (a prosperous, healthy, productive life); and “life feeling good” (a life of subjective happiness, joy, pleasure, etc.) ( 2015 : p. 75). What is that state of the empirical evidence for the bearing of religious practice on each of them?

First, regarding “a life well led,” a great deal of evidence suggests that religious belief and practice generally make participants less prone to delinquency and crime (Johnson et al., 2001 ; Johnson, 2011 ), fairer and more honest (Tan et al., 2008 ; Ruffle and Sossis, 2006 ; Haidt, 2012 : pp. 308–309), and more generous in their dealings with others (Brooks, 2007 ). Footnote 10 Second, regarding “a life going well,” the data is again abundant, and its trend is clear: those who attend religious services at least weekly are about 34% less likely to binge drink than those who never attend (Chen et al., 2020a ), while adolescents who attend services regularly have a 33% lower risk of illegal drug use and a 40% lower risk of contracting an STD compared to never-attenders (Chen and VanderWeele, 2018 ). Regular attenders are also about 50% less likely to divorce (Li et al., 2018 ), 27% less likely to become depressed, and five times less likely to commit suicide than non-attenders (Li et al., 2016a ; VanderWeele et al., 2016 ), and, in fact, 33% less likely to die (over sixteen years of follow-up) than non-attenders (Chen et al., 2020b ; Li et al., 2016b ). Finally, there is strong evidence that religious participation contributes to a “life that feels good,” a happy or joyful life: religious practitioners consistently report higher levels of meaning and purpose in their lives than non-practitioners (Chen et al., 2020a ), as well as higher levels of overall life satisfaction (Lim and Putnam, 2010 ). While questions of causality and directionality are almost always open to dispute, the research on this topic has become increasingly rigorous, employing data over time and principles of causal inference to evaluate evidence (cf. VanderWeele, 2017 ; Koenig et al., 2024 ; Fruehwirth et al., 2019 ; Giles et al., 2023 ).

Of course, many of these findings may well generalize across religions, including “primary” or “pre-Axial Age” religions. (On the transition from primary or archaic religion to “secondary,” “world,” or “axial age” religion, cf. esp. Jaspers, 1953 ; Bellah, 2017 ).

Belief in a post-mortem final judgment according to one’s deeds, for instance, seems to have originated in Middle Kingdom Egypt (cf. The Egyptian Book of the Dead 1895 : ch. 125; Assmann, 2005 : Kindle loc. 1471–75), where it appears already to have served to discipline the lives of believers anticipating it (Assmann, 2005 : Kindle loc. 1614).

Even religious practices that rightly horrify us today might have once been a source of Durkheimian social cohesion. When King Mesha of Moab sacrificed his eldest son on the walls of his besieged city, for instance, his troops apparently flew into a frenzy which turned the tide of the Israelite advance (cf. 2 Kings 3:26–27). Indeed, it seems reasonable to think that much of what social scientists or theologians alike study under the rubric of “religion” is emphatically a natural phenomenon, which unites us to one another by uniting each of us to some conception of divinity or transcendence (cf. Haidt, 2012 : p. 303).

World religions typically have their own internal strategies for relating religion as a “natural” phenomenon to their own claims to a relatively fuller measure of the truth of things. Mahayana Buddhists, for instance, characteristically regard spiritual traditions other than the Dharma as the “compassionate skillful means” employed by the Buddha in one of his many “transformation bodies” so as to nudge wayward sentient beings closer to ultimate truth (Williams 2008 : p. 181). For the Christian theologian Karl Barth, by contrast, “natural” religion is “sublated” (in Hegel’s sense of a development that at once preserves and transforms its predecessor) in the rites revealed to Israel and brought to their fullness in Christ (Barth, 2007 : Kindle loc. 887; cf. Hegel, 1878 : 1.4.3).

The empirical social sciences can help contribute evidence towards corroborating claims that theologians or philosophers may take as self-evident. In some cases, the data may play out as expected, but in other cases, this may not be so. Footnote 11 Often, however, empirical research is needed to confirm or challenge intuitive but ultimately empirically testable convictions. Many confessional thinkers might well be less than enthusiastic about social scientists’ accounts of religious community, either because of their apparent reduction of grace to nature, or because the results do not confirm some of their prior convictions. Nonetheless, we think that these tensions provide an important opportunity for deepened reflection on their part.

Establishing effective interventions: how can we promote forgiveness?

For our final category of social-scientific influence on the humanities, let’s consider an area in which there is some agreement about a desired goal, but a need for greater clarity in how to bring it about. For instance, many agree that forgiveness—understood as the replacement of one wronged of ill-will for good-will towards the offender—is an important good both for individuals and for their broader communities (VanderWeele, 2018 ). Importantly, forgiveness in this sense is not to be confused with condoning the offense, reconciling with the offender, or even foregoing punishment for the offense (Worthington, 2013 ).

With regard to its desirability, there is a growing body of evidence that suggests that being forgiving is associated with improved outcomes across a range of public health measures, including, for example, less depression and less anxiety, and possibly better physical health (Wade et al., 2014 ; Toussaint et al., 2015 ; Long et al., 2020 ). For religious believers across many traditions, forgiveness is a spiritual duty; Christians, for instance, regularly pray that God would “forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors” (Matt. 6:12). Finally, many today also recognize that forgiveness—or related concepts such as “reconciliation”—is of deep social and political relevance in societies seeking to heal from past traumas, whether in post-Communist Balkan republics (Volf, 1996 ), post-apartheid South Africa (Forster, 2019 ), or post-genocide Rwanda and Burundi (Katangole and Rice, 2008 ).