The Barker Underground

Writing advice from the harvard college writing center tutors, the four parts of a lens essay argument.

by Emily Hogin

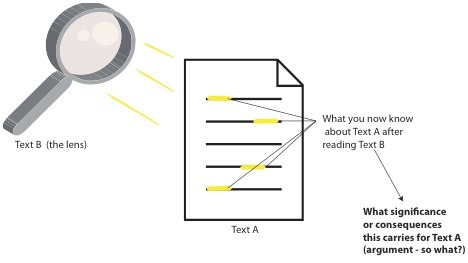

One of the most common prompts I see at the Writing Center is the “lens essay.” A lens essay brings two texts in dialogue with one another in a very particular way. It asks you to use Text B – the lens – to illuminate something you didn’t already know about Text A.

How Not to Argue a Lens Essay

A lens essay is not a list of differences and similarities between two texts. The following are some (exaggerated) examples of a bad argument for a lens essay I’ve come across at the Writing Center:

Even though one is philosophy and the other is a novel, both Text A and Text B talk about the imagination.

This first thesis statement notes a similarity between the two texts that will likely be obvious to readers of the text. It doesn’t use one text to illuminate anything about the other.

While both Text A and Text B argue that human nature is unchangeable, Text A asserts that humans are inherently good and Text B asserts that humans are inherently bad.

This thesis makes a claim about each text but doesn’t say anything about them in relation to each other.

Text A, a poem, does a better job of communicating the emotional struggles of living with HIV than Text B, a statistical report, because a poem allows readers to identify emotionally with other people while statistics are more abstract and cold.

This third thesis statement does make an argument that connects both texts, but again fails to use one text to tell us something we don’t already know about the other text.

In my experience, a successful lens essay implies a certain kind of thought-process that has at least four parts:

(1) I read Text A

(2) I read Text B (my lens)

(3) I re-read Text A and noticed something I didn’t notice before

(4) That something turns out to carry consequences for my overall reading of Text A (thesis/argument)

(And if you really want to wow your reader, you’d add a final part:)

(5) Applying Text B (my lens) in this way also reveals something significant about Text B

When I say significance or consequences, I don’t mean that it has to alter the meaning of a text radically; it can be something small but important. For example, you might find that one element is a lot more important (or a lot less important) to the overall text than you had previously thought.

As an example, here is an excerpt from the introduction to my last lens essay:

The concept of the imagination is ambiguous throughout Venus in Furs : at times, the imagination appears as passive as a battleground that external forces fight to occupy and control; at other times, the imagination appears to drive the action as if it is another character. Any theory of sexuality that seeks to explain Venus in Furs thus must be able to explain the ambiguity over the imagination. Foucault’s theory of the inescapable knowledge-power of sexuality comes close to being able to explain Sacher-Masoch’s ambiguous concept of the imagination, but applying Foucault in this way highlights Foucault’s own difficulty situating the imagination within his theory.

You can see my lens essay thought-process in just these three sentences:

(1) I read Venus in Furs (Text A) and noticed that the imagination is ambiguous

(2) I read Foucault (Text B, my lens) (3) to better understand the imagination in Venus in Furs

(4) Foucault helped explain why an ambiguous imagination is an appropriate way to look at sexuality

but (5) applying Foucault to the imagination tells me that Foucault’s own theory is challenged when he has to account for the imagination.

Once you have an argument for a lens essay, you will have to structure your paper in a way that allows this lens essay thought-process to come across. This means that each of your topic sentences should refer back to this thought-process. Even if you need a paragraph that discusses one of the texts primarily, your topic sentence should justify why you’re doing that. Your complicated and interesting thesis will likely require you to move back and forth between Text A and Text B (your lens).

Of course, your argument will depend on your assignment, but I’ve found this four-part approach successful in a number of courses where the assignment asked me to bring two texts in dialogue with one another.

Share this:

Leave a comment.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

How to Write a Critical Lens Essay Successfully Step by Step

Critical lens essay writing is a type of literary analysis where the writer is required to analyze and interpret a specific piece of literature or a quote. The essay typically involves discussing the meaning of the quote and how it relates to two literary works. The author is expected to use literary elements and techniques to support their interpretation and provide evidence from the texts.

The term "critical lense" refers to the perspective or lenses through which the scribe views and analyzes the literature. It often involves exploring the cultural, historical, or philosophical context of the works being analyzed. The goal is to demonstrate a deep understanding of the literature and present a well-argued interpretation.

In this guide, we’ll explore such crucial aspects of how to write critical lens essay, its definition, format, and samples. Just in case you’re in a big hurry, here’s a link to our essay writer service that can help you cope with a task at hand quickly and effortlessly.

What Is a Critical Lens Essay and How to Write It

A critical lens analysis is a form of literary exploration that challenges students to interpret and analyze a specific quote, known as the "lens," and apply it to two pieces of literature. This type of composition aims to assess a student's understanding of literary elements, themes, and the broader implications of the chosen quote. Effectively producing a research paper involves several key steps, each contributing to a comprehensive and insightful analysis.

The critical lens meaning is to provide a unique perspective into the complexities of literature. It goes beyond mere summarization, urging students to explore the layers of meaning embedded within the chosen quote and its application to literary works. Unveiling the assignment's meaning requires a keen eye for nuance and an appreciation for the intricate dance between language and interpretation.

Knowing how to write a lens essay involves mastering the art of interpretation. As students embark on this literary journey, the process of achieving this task becomes integral. It demands an exploration of the chosen quote's implications, an in-depth analysis of its resonance with the selected literature, and a thoughtful synthesis of ideas. A step-by-step approach is crucial, from deciphering the meaning to meticulously weaving insights into a cohesive and compelling narrative.

A lens analysis is more than a scholarly exercise; it's a nuanced exploration of the intersections between literature and life. It prompts students to unravel the layers of meaning embedded within the viewpoint, dissecting its implications for characters, themes, and overarching narratives. This analytical journey not only refines academic skills but also cultivates a deeper appreciation for the profound impact literature can have on our understanding of the human experience.

Step-by-Step Writing Guide

In this guide, we will explore the assignment’s prerequisites and outline five steps to help students understand how to write a critical lens essay.

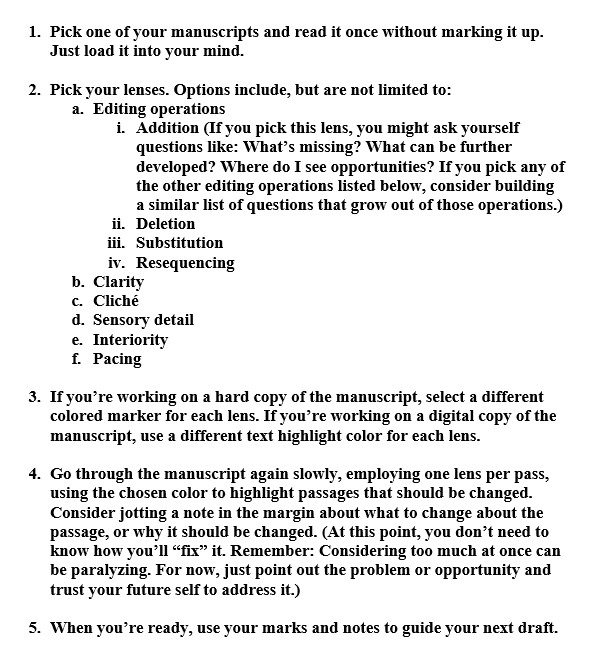

.png)

STEP 1 - Understand the Critical Lens Quote

The journey of crafting a compelling draft begins with a deep understanding of the chosen quote or viewpoint. This quote typically embodies a philosophical or thematic idea that serves as a foundation for analyzing the selected literary works. Students should dissect the quote, exploring its nuances, underlying meanings, and potential applications to literature.

STEP 2 - Select Appropriate Literary Works

Once the sources are comprehended, the next step is to select two literary works that can be effectively analyzed through this framework. Choosing appropriate texts is crucial, as they should offer rich content and thematic depth, allowing for a comprehensive exploration. Students must consider how the texts align with and diverge from the central ideas presented in the quote.

STEP 3 - Interpret the Chosen Texts

With the literary works in hand, students embark on a close reading and analysis of the selected texts. This involves identifying key themes, characters, literary devices, and narrative elements within each work. The goal is to understand how each text relates to the material and to uncover the deeper meanings encapsulated in the literature.

STEP 4 - Write a Thesis Statement for Your Critical Lens Essay

The thesis statement is the compass guiding the entire document. It should succinctly capture the composer’s interpretation of the original source and how it applies to the chosen texts. A well-crafted thesis statement not only outlines the focus of the essay but also provides a roadmap for the subsequent analysis, showcasing the author’s unique perspective.

STEP 5 - Structure the Essay Effectively

The final step involves organizing the tract into a coherent and persuasive structure. A well-structured article typically includes an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. In the introduction, students present their interpretation, introduce the chosen texts, and offer a clear thesis statement. Body paragraphs delve into specific aspects of lenses and their application to each text, supported by relevant evidence and analysis. The conclusion synthesizes the key findings, reinforces the thesis, and leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

A successful article requires a meticulous approach to interpreting the quote, selecting appropriate literary works, closely analyzing the texts, crafting a robust thesis statement, and structuring the document effectively. By following these five key steps, students can develop a well-rounded and insightful article that not only demonstrates their understanding of literature but also showcases their ability to apply analytical thinking skills to literary analysis. Should you find the process challenging, simply contact us and say, ‘ Write an essay for me ,’ so we can find you a perfect writer for the job.

Critical Lens Essay Outline

Creating a comprehensive lens essay outline is an essential preparatory step that helps students organize their thoughts and ensures a well-structured effort. Below is a suggested outline, dividing the task into logical sections:

Introduction:

- Hook: Begin with a captivating hook or quote to engage the reader.

- Quote: Introduce the chosen quote, providing context and potential interpretations.

- Interpretation: Offer your initial interpretation and its implications.

- Thesis Statement: Clearly state your thesis, outlining how the document applies to the chosen literary works.

Body Paragraphs:

Paragraph 1: First Literary Work

- Brief Overview: Provide a concise summary of the first literary work.

- Connection to Critical Lens: Analyze how it applies to this text.

- Evidence: Incorporate relevant quotes or examples from the text to support your analysis.

- Interpretation: Discuss the deeper meanings revealed through the analysis.

Paragraph 2: Second Literary Work

- Brief Overview: Summarize the second literary work.

- Connection to Critical Lens: Examine how it is reflected in this text.

- Evidence: Include specific quotes or instances from the text to bolster your analysis.

- Interpretation: Explore the profound implications illuminated by the material.

Paragraph 3: Comparative Analysis

- Common Themes: Identify shared themes or patterns between the two works.

- Differences: Highlight key differences and divergent interpretations.

- Unity: Emphasize how both work collectively to reinforce the analysis.

- Counterargument.

Conclusion:

- Recapitulation: Summarize the main points discussed in the body paragraphs.

- Thesis Restatement: Reiterate your thesis in a compelling manner.

- Concluding Thoughts: Offer final reflections on the broader implications of your analysis.

By adhering to this outline, students can systematically approach their essays, ensuring a coherent and well-supported exploration of the chosen perspective and literary works. The outline serves as a roadmap, guiding the author through each essential element and facilitating a more organized and impactful final product. You will also benefit from learning how to write a character analysis essay because this guide also offers a lot of useful tips.

.png)

Introduction

The introduction plays a pivotal role in capturing the reader's attention and establishing the foundation for the ensuing analysis. Begin with a compelling hook or a thought-provoking quote that relates to the chosen perspective. Following the hook, introduce the quote itself, providing the necessary context and initial interpretations. This is also the space to present the thesis statement, succinctly outlining how the outlook applies to the literary works under examination. The thesis should offer a roadmap for the reader, indicating the key themes or ideas that will be explored in the body paragraphs.

The main body paragraphs constitute the heart of the article, where the essayist delves into a detailed analysis of the chosen literary works through the framework provided. Each body paragraph should focus on a specific literary work, providing a brief overview, connecting it to the perspective, presenting evidence from the text, and offering interpretations. Use clear topic sentences to guide the reader through each paragraph's main idea. Strive for a balance between summarizing the text and analyzing how it aligns with the outlook. If applicable, include a comparative analysis paragraph that explores common themes or differences between the two works. This section requires a careful integration of textual evidence and insightful commentary. Keep in mind that learning the ins and outs of a literary analysis essay might also help you improve your overall written skills, so check it out, too!

The conclusion serves as a synthesis of the analysis, offering a concise recapitulation of the main points explored in the body paragraphs. Begin by summarizing the key findings and interpretations, reinforcing how each literary work aligns with the work’s angle. Restate the thesis in a conclusive manner, emphasizing the overarching themes that have emerged from the analysis. Beyond a mere recap, the conclusion should provide broader insights into the implications of the outlook, encouraging readers to contemplate the universal truths or societal reflections brought to light. A strong conclusion leaves a lasting impression, prompting reflection on the interconnectedness of literature and the perspectives that illuminate its depth.

Critical Lens Essay Example

Final Remark

Through the exploration of literary works, students not only refine their understanding of diverse perspectives but also develop essential analytical thinking skills. The ability to decipher, analyze, and articulate the underlying themes and conflicts within literature positions students as adept communicators and thinkers.

Armed with the skills cultivated in dissecting and interpreting texts, students gain a formidable ally in the pursuit of effective communication. By committing to harnessing the insights gained through this assignment, students empower themselves to produce richer, more nuanced pieces.

How to Write a Thesis Statement for Your Critical Lens Essay?

How does using a critical lens essay help writers, what are the best critical lens essay examples.

- Plagiarism Report

- Unlimited Revisions

- 24/7 Support

Writing a “Lens” Essay

This handout provides suggestions for writing papers or responses that ask you to analyze a text through the lens of a critical or theoretical secondary source.

Generally, the lens should reveal something about the original or “target” text that may not be otherwise apparent. Alternatively, your analysis may call the validity of the arguments of the lens piece into question, extend the arguments of the lens text, or provoke some other reevaluation of the two texts. Either way, you will be generating a critical “dialogue between texts.”

Reading the Texts

Since you will eventually want to hone in on points of commonality and discord between the two texts, the order and manner in which you read them is crucial.

First, read the lens text to identify the author’s core arguments and vocabulary. Since theoretical or critical texts tend to be dense and complex, it may be helpful to develop an outline of the author’s primary points. According the to Brandeis Writing Program Handbook, a valuable lens essay will “grapple with central ideas” of the lens text, rather than dealing with isolated quotes that may or may not be indicative of the author’s argument as a whole. As such, it’s important to make sure you truly understand and can articulate the author’s main points before proceeding to the target text.

Next, quickly read the target text to develop a general idea of its content. Then, ask yourself: Where do I see general points of agreement or disagreement between the two texts? Which of the lens text’s main arguments could be applied to the target text? It may be easier to focus on one or two of the lens text’s central arguments.

With these ideas in mind, go back and read the target text carefully, through the theoretical lens, asking yourself the following questions: What are the main components of the lens text and what are their complementary parts in the target text? How can I apply the lens author’s theoretical vocabulary or logic to instances in the target text? Are there instances where the lens text’s arguments don’t or can’t apply? Why is this? It is helpful to keep a careful, written record of page numbers, quotes, and your thoughts and reactions as you read.

Since this type of paper deals with a complex synthesis of multiple sources, it is especially important to have a clear plan of action before you begin writing. It may help to group quotes or events by subject matter, by theme, or by whether they support, contradict, or otherwise modify the arguments in the lens text. Hopefully, common themes, ideas, and arguments will begin to emerge and you can start drafting!

Writing the Introduction and Thesis

As your paper concerns the complex interactions between multiple texts, it is important to explain what you will be doing the introduction. Make sure to clearly introduce the lens text and its specific arguments you will be employing or evaluating. Then introduce the target text and its specific themes or events you will be addressing in your analysis.

These introductions of texts and themes should lead into some kind of thesis statement. Though there are no set guidelines or conventions for what this thesis should look like, make sure it states the points of interaction you will be discussing, and explains what your critical or theoretical analysis of the target text reveals about the texts.

Writing the Body

The body is where you apply specific arguments from the lens text to specific quotes or instances in the target text. In each case, make sure to discuss what the lens text reveals about the target text (or vice versa). Use the lens text’s vocabulary and logical framework to examine the target text, but make sure to be clear about where ideas in the paper are coming from (the lens text, the target text, your own interpretation etc.) so the reader doesn’t become confused.

By engaging in this type of analysis, you are “entering an academic conversation” and inserting your own ideas. As this is certainly easier said than done, Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein’s concept of “Templates” may prove useful. In their book, They Say, I Say, the authors lay out numerous templates to help writers engage in unfamiliar forms of critical academic discourse. They encourage students to use the templates in any capacity they find useful, be it filling them in verbatim, modifying and extending them, or using them as an analytical entry point, then discarding them completely.

Here I modify their basic template (They say ________. I say ________.), to create lens essay-specific templates to help you get started:

The author of the lens text lays out a helpful framework for understanding instances of ________ in the target text. Indeed, in the target text, one sees ________, which could be considered an example of ________ by the lens author’s definition. Therefore, we see a point of commonality concerning ________. This similarity reveals ________.

According to the lens text _______ tends to occur in situations where _______. By the lens author’s definition, ________ in the target text could be considered an instance of _______. However, this parallel is imperfect because _______. As such, we become aware of ________.

One sees ________ in the target text, which calls the lens author’s argument that ________ into question because ________.

If the author of the lens text is correct that ________, one would expect to see ________ in the target text. However, ________ actually takes place, revealing a critical point of disagreement. This discord suggests that ________. This issue is important because ________.

Wrapping Things up and Drawing Conclusions

By this point in your essay, you should be drawing conclusions regarding what your lens analysis reveals about the texts in questions, or the broader issues the texts address. Make sure to explain why these discoveries are important for the discipline in which you are writing. In other words, what was the point of carrying out your analysis in the first place? Happy lens writing!

Brandeis UWS Writing Handbook, 70.

UWS Handbook, 76.

Birkenstein, Cathy and Gerald Graff, They Say, I Say. (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2007), 2-3.

Mailing Address

Pomona College 333 N. College Way Claremont , CA 91711

Get in touch

Give back to pomona.

Part of The Claremont Colleges

Tag Archives: lens essay

“the death of ivan ilych: a psychological study on death and dying” as a lens essay.

The lens essay is a commonly-assigned paper, particularly in Writing Seminars. The prompt for such a paper often asks students to “critique and refine” an argument, to use a source as a lens through which to view another source and in the process gain a better understanding of both sources. This type of essay can be hard to explain and difficult to understand, so it is one of the most common types of essays we see in the Writing Center.

Recently, I read Y.J. Dayananda’s paper “ The Death of Ivan Ilych : A Psychological Study On Death and Dying ” which uses the lens technique. In this paper, Dayananda examines Tolstoy’s famous short story The Death of Ivan Ilych through the lens of Dr. E. K. Ross’s psychological studies of dying, particularly her five-stage theory. Dayananda’s paper features strong source use, shows how structure can be informed by those sources, and serves as a model for an effective and cross-disciplinary lens essay.

Dayananda establishes the paper’s argument clearly at the end of the introduction, setting up the paper’s thesis in light of this lens technique and providing the rationale (part of the motive) behind applying Ross’s study to Tolstoy’s story:

I intend to draw upon the material presented in Dr. Ross’s On Death and Dying and try to show how Tolstoy’s Ivan Ilych in The Death of Ivan Ilych goes through the same five stages. Psychiatry offers one way to a better illumination of literature. Dr. Ross’s discoveries in her consulting room corroborate Tolstoy’s literary insights into the experience of dying. They give us the same picture of man’s terrors of the flesh, despair, loneliness, and depression at the approach of death. The understanding of one will be illuminated by the understanding of the other. The two books, On Death and Dying and The Death of Ivan Ilych , the one with its systematically accumulated certified knowledge, and disciplined and scientific descriptions, and the other with its richly textured commentary, and superbly concrete and realistic perceptions, bring death out of the darkness and remove it from the list of taboo topics. Death, our affluent societies newest forbidden topic, is not regarded as “obscene” but discussed openly and without the euphemisms of the funeral industry.

Dayananda then organizes the paper in order of the five stages of Dr. Ross’s theory: denial, loneliness, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. This gives the paper a clear structure and places the texts into conversation with each other on an organizational level. As the reader moves through each stage, Dayananda combines quotations from Dr. Ross’s study and evidence from The Death of Ivan Ilych to show how Ivan Ilych experiences that stage.

Dayananda’s interdisciplinary close-reading of Tolstoy’s text through the lens of Dr. Ross’s study allows us to better understand what Ivan is experiencing as we learn the psychology behind it. As Dayananda writes, “psychoanalysis offers a rich, dynamic approach to some aspects of literature.” The only way Dayananda’s paper could have been strengthened is if the essay also argued explicitly how reading the literature critiques or refines the psychological text, as the best lens essays run both ways. However, overall, Dayananda sets up and executes an original and effective lens reading of The Death of Ivan Ilych.

–Paige Allen ’21

Dayananda, Y. J. “ The Death of Ivan Ilych: A Psychological Study On Death and Dying .” Tolstoy’s Short Fiction: Revised Translations, Backgrounds and Sources, Criticism , by Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoi and Michael R. Katz, Norton, 1991, pp. 423–434.

The Shade of the Body: Notions of Materiality in Rauschenberg’s Dante Series

In a Tortoiseshell: In the paper excerpted below, the author builds a graduated version of the lens thesis: She analyzes Robert Rauschenberg’s 34 Drawings for Dante’s Inferno in the context of Dante’s Inferno itself, using close reading as well as scholarly texts to make a subtle argument about both texts.

Continue reading →

The “Immense Edifice”: Memory, Rapture, and the Intertemporal Self in Swann’s Way

In a Tortoiseshell: This excerpt from Andrew Mullen’s essay “The ‘Immense Edifice”: Memory, Rapture, and the Intertemporal Self in Swann’s Way ” concerns the analysis of Marcel Proust’s “ Swann’s Way ” through the lens of Claudia Brodsky’s essay on narration and memory. Andrew’s essay is a prime example of the lens essay –an essay that is structured around the analysis of a source text using a theoretical framework provided by another. Continue reading →

- Current Issue

- Issue Archives

What Is A Lens In Writing? (The Ultimate Guide)

Ever feel like your writing is stuck in a one-dimensional rut? Then you need to use a lens.

What is a lens in writing?

A lens in writing is a tool that shifts your perspective, like looking through a kaleidoscope. Writing lenses include historical, psychological, and critical. Use a writing lens to analyze, interpret, and craft richer, more engaging writing.

Buckle up, language enthusiast, because this ultimate guide dives deep into the fascinating world of writing lenses.

What Is a Lens in Writing? (10 Types)

Table of Contents

Think of a lens as a specific viewpoint or approach you adopt while writing.

It guides how you dissect information, select arguments, and craft your message.

Whether you analyze literature, dissect historical events, or craft marketing copy, lenses offer unique filters through which you process and present your ideas.

To simplify your journey, I’ve compiled a handy chart outlining 10 popular lenses:

Go ahead, bookmark this chart! It’s your cheat sheet to unlocking a universe of creative perspectives.

Now, let’s explore each lens, equipping you to wield them like a writing ninja.

Through the Lens of Time: The Historical Lens

What it is: The historical lens transports you to the past, examining your topic within the context of its era. This involves considering the social, political, and cultural factors that shaped events and influenced individuals.

How to use it: Research the historical context: dig into primary sources like documents, letters, and diaries. Analyze social norms, political structures, and major events of the time period. Consider how these factors influenced your topic and how your understanding might differ from a modern perspective.

Example: Analyzing a Shakespearean play through the historical lens involves understanding Elizabethan social hierarchy, religious beliefs, and theatrical conventions. This helps you interpret character motivations, plot developments, and the play’s overall message within its historical context.

Unveiling the Mind: The Psychological Lens

What it is: The psychological lens delves into the inner workings of the human mind, exploring characters’ motivations, behaviors, and mental states. It draws on psychological theories to analyze their actions, reactions, and thought processes.

How to use it: Identify key characters and their actions. Apply relevant psychological theories, such as Freudian psychoanalysis or cognitive-behavioral therapy, to explain their motivations. Analyze how their experiences and environment shape their behavior and mental state.

Example: Examining Hamlet’s indecisiveness and introspection through a psychological lens could involve applying Freudian concepts like the Oedipus complex and existential anxieties. This deepens your understanding of his character and the play’s exploration of human nature.

Decoding Social Structures: The Sociological Lens

What it is: The sociological lens focuses on the interactions, norms, and power dynamics within communities and societies. It examines how individuals and groups relate to each other, considering factors like social class, race, gender, and cultural values.

How to use it: Identify the social context of your topic: analyze social structures, power dynamics, and potential conflicts within the group or society. Consider how these factors influence individual experiences and group behaviors. Apply sociological theories like conflict theory or symbolic interactionism to explain observations.

Example: Analyzing a social media trend through the sociological lens might involve examining how it reflects broader cultural values, power dynamics between different groups, and the role of technology in shaping social interactions.

Weighing Wallets and Resources: The Economic Lens

What it is: The economic lens analyzes the financial aspects of a topic, focusing on production, consumption, and distribution of resources. It considers factors like market forces, economic policies, and social inequalities.

How to use it: Identify the economic context: analyze relevant economic concepts like supply and demand, resource allocation, and market structures. Explore how economic factors influence your topic and the individuals involved. Consider potential economic consequences of different actions or policies.

Example: Evaluating the impact of climate change through the economic lens might involve analyzing its effects on different industries, economic losses due to extreme weather events, and potential costs of implementing mitigation strategies.

Unveiling Power Plays: The Political Lens

What it is: The political lens examines the dynamics of power, governance, and influence within a political system. It analyzes how decisions are made, power is distributed, and individuals or groups compete for influence.

How to use it: Identify the political context: understand the structure of government, key political actors, and prevailing ideologies. Analyze how political dynamics influence your topic and the individuals involved. Consider potential political implications of different actions or policies.

Example: Examining a protest movement through the political lens might involve analyzing its demands in relation to existing power structures, the influence of political parties, and potential responses from the government.

Beyond Biology: The Gender Lens

What it is: The gender lens analyzes how gender identities, roles, and expectations shape experiences and social structures. It examines how individuals and groups are affected by societal norms and power dynamics related to gender.

How to use it: Identify the gender context: analyze dominant societal expectations for different genders, consider power dynamics and potential inequalities. Explore how gender roles and identities influence your topic and the individuals involved.

Example: Analyzing a novel through the gender lens might involve examining how female characters challenge or conform to societal expectations, exploring the portrayal of masculinity, and questioning power dynamics between genders.

Understanding Shared Values: The Cultural Lens

What it is: The cultural lens delves into the shared beliefs, values, and practices of a particular group or society. It examines how cultural norms, traditions, and customs shape experiences and behaviors.

How to use it: Identify the cultural context: research the specific belief systems, traditions, and values relevant to your topic and target audience. Analyze how cultural factors influence the perception and interpretation of your topic.

Example: Comparing advertising strategies across different cultures through the cultural lens might involve examining how humor, color symbolism, and family dynamics differ and how these differences impact marketing effectiveness.

The Power of Words: The Rhetorical Lens

What it is: The rhetorical lens analyzes how language is used to persuade, inform, or entertain. It examines the speaker’s purpose, strategies, and techniques to achieve their desired effect on the audience.

How to use it: Identify the speaker’s purpose and target audience. Analyze the language used, considering elements like tone, imagery, and emotional appeals. Evaluate the effectiveness of the speaker’s strategies in achieving their desired response.

Example: Analyzing a political speech through the rhetorical lens might involve examining how the speaker uses persuasive techniques like repetition, emotional appeals, and logical arguments to influence the audience’s opinion.

Preserving Our Planet: The Environmental Lens

What it is: The environmental lens considers the impact of human actions on the natural world. It examines issues like sustainability, resource management, and ecological consequences of human activities.

How to use it: Identify the environmental context: analyze the ecological impact of your topic and consider relevant environmental issues. Explore potential solutions and sustainable practices related to your topic.

Example: Evaluating the social impact of a new technology through the environmental lens might involve considering its energy consumption, potential pollution, and impact on biodiversity and resource depletion.

Shaping the Future: The Technological Lens

What it is: The technological lens examines the role of technology in society, focusing on its development, impact, and ethical implications. It analyzes how technology shapes our lives and raises important questions about its future evolution.

How to use it: Identify the technological context: understand the specific technology and its development stage. Analyze the social, economic, and ethical implications of its use. Consider potential future scenarios and responsible tech development practices.

Example: Discussing the potential benefits and risks of artificial intelligence through the technological lens might involve analyzing its impact on jobs, automation, and potential biases, highlighting the need for ethical considerations in its development and deployment.

Remember, these are just a few of the many writing lenses available. With practice and exploration, you can unlock a world of creative possibilities, enriching your writing and engaging your audience with diverse perspectives.

What Is a Critical Lens in Writing?

A critical lens is, in essence, a specific perspective or approach you adopt to critically examine a topic or text.

It acts as a filter, guiding how you analyze information, evaluate arguments, and ultimately shape your understanding.

Unlike mere summaries or descriptions, critical lenses encourage in-depth questioning, pushing you beyond surface-level observations to unearth deeper meanings and underlying assumptions.

Think of it this way: Imagine examining a painting through a magnifying glass.

While you could simply describe the colors and shapes, the magnifying glass allows you to closely scrutinize brushstrokes, textures, and hidden details, revealing the artist’s technique and message in a nuanced way.

Similarly, critical lenses empower you to zoom in on information, dissecting its layers and uncovering its deeper significance.

But remember, critical lenses are not about imposing a singular “correct” interpretation.

Watch this video about writing a critical lens essay:

Final Thoughts: What Is a Lens in Writing?

Don’t be afraid to experiment, break the mold, and see the world through a new lens. Write on!

Read This Next:

- What Is A Universal Statement In Writing? (Explained)

- What Is Writing Style? (Easy Guide for Beginners)

- What Is a Snapshot in Writing? (Easy Guide + 10 Examples)

- Tag Writing (Ultimate Guide for Beginners)

How to Write a Lens Essay

Sophie levant, 25 jun 2018.

Look closely at literature, and you may see a new world below the surface. In high school or college, a teacher may ask you to do this by writing a lens essay. A lens essay is a type of comparative paper that analyzes one text through the viewpoints expressed in another. Composing an effective one is difficult even for the most seasoned of writers. However, it is an incredible intellectual exercise through which you will not only improve your writing skills but your critical reading and thinking skills as well.

Explore this article

- Read the Lens Text

- Read the Focus Text

- Take a Closer Look

- Construct Your Thesis

- Compose the Body of Your Essay

- Sum Up Your Ideas

- Revise and Edit

things needed

- Your two texts

- Pen and paper

1 Read the Lens Text

Begin by reading the text you plan to use as your viewpoint. Take note of strong opinions, assumptions and justifications. Clear, concise notes about this section will help when using this text as a lens and when writing your final essay, so make sure your notes are accurate.

2 Read the Focus Text

Read the second work once, making note of its important details. Look back at your notes from the lens text, and read the focus text again with the lens text in mind. Use active reading skills such as writing questions in the margins and determining the purpose of each paragraph.

3 Take a Closer Look

Here are a few questions to consider when analyzing the content of your focus text: How does the lens text serve to shed light on the second text? Does it criticize it or support it? If the two pieces were written during different periods in history, consider the era in which the lens was written and how it affects the opinions or points made in the second. Consider the lives of the authors and how their differences might inform their writing.

4 Construct Your Thesis

With your notes in hand, construct your thesis statement. Using details from the both texts as context clues, determine how the author of the lens text would view the assertions of the focal text. Construct this view as a statement that includes the details expounded upon in the body paragraphs of your essay. At the same time, keep your thesis statement as clear and simple as you can. Your thesis statement is the roadmap to the rest of your paper. Its clarity and concision will help your reader understand what to expect.

5 Compose the Body of Your Essay

Write the body. A lens essay is typically constructed on a text-by-text basis. Concentrate on presenting the lens in the first paragraphs. In the following, present the second text as viewed through the lens. How do your points support the thesis? Make sure to include evidence for your assertions.

6 Sum Up Your Ideas

Write the conclusion. Restate your thesis first, then sum up the main points of your paper. Be sure to make what you have said meaningful. Don't let the paper fizzle out, but don't introduce new information either.

7 Revise and Edit

Read over your work at least once, first paying attention to content and inconsistencies in your argument. Make additions and corrections, and then proofread your work. Correct errors in style and grammar, and make sure your prose reads fluently. When in doubt, ask a friend to read your paper. Sometimes another set of eyes can catch mistakes that yours don't.

- It is always well worth your time to proofread and edit your paper before submission. Not only can you correct any errors in style and grammar, but inconsistencies in your argument as well.

- 1 Brandeis University: The Lens Essay

- 2 The McGraw Center for Teaching and Learning: Active Reading Strategies

About the Author

Sophie Levant is a freelance writer based in Michigan. Having attended Michigan State University, her interests include history classical music, travel, and the German language. Her work has been published at eHow and Travels.

Related Articles

How to Write a Thesis Statement for an Article Critique

How to Write an Informative Summary

Different Types of Reading Strategies

How to Summarize an Essay or Article

How to Write a Comparison Essay of Text to Text

How to Improve Adult Reading Comprehension

How to Write a Summary Paper in MLA Format

How to Write a DBQ Essay

Three Components of a Good Paragraph

How to Write a Reaction Paper

How to Annotate a Reading Assignment

How to Erase Highlighters

How to Find a Thesis in an Essay

How to Summarize a Reading Assignment

How to Choose a Title for Your Research Paper

How to Write a Critique Essay

How to Write a Paper: Title, Introduction, Body & Conclusion

Comprehension Skills That Require Critical Thinking

Difference Between a Paraphrase & a Summary

How to Do Skimming in a Reading Comprehension Test

Regardless of how old we are, we never stop learning. Classroom is the educational resource for people of all ages. Whether you’re studying times tables or applying to college, Classroom has the answers.

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright Policy

- Manage Preferences

© 2020 Leaf Group Ltd. / Leaf Group Media, All Rights Reserved. Based on the Word Net lexical database for the English Language. See disclaimer .

Lens Analysis

What is lens analysis?

Lens analysis requires you to distill a concept, theory, method or claim from a text (i.e. the “lens”) and then use it to interpret, analyze, or explore something else e.g. a first-hand experience, visual text, physical object or space, historical or current event or figure, a cultural phenomenon, an idea or even another text (i.e. the “exhibit”).

A writer employing lens analysis seeks to assert something new and unexpected about the exhibit; he or she strives to go beyond the expected or the obvious, exploiting the lens to acquire novel insights. Furthermore, there is a reciprocal aspect in that the exploration of the exhibit should cause the writer to reflect, elaborate, or comment on the selected concept or claim. Using a concept developed by someone else to conduct an analysis or interpretation of one’s own is a fundamental move in academia, one that you will no doubt be required to perform time and time again in college.

Note: The first part of the process (ICE) is also known as a “quote sandwich,” which makes sense if you think about it.

How to Perform Lens Analysis

- Introduce selected quotation from lens text i.e. provide the source for the quote as well as its context.

- Cite the quotation i.e. use a signal phrase and partial quotation to present the author’s ideas clearly to your reader. Make sure to provide the required citation (MLA for this class).

- Explain what the quotation means in terms of your argument i.e. ensure that the meaning of the quotation is clear to your reader in connection to your argument.

- Apply the quotation to a specific aspect of the exhibit i.e. use the idea expressed in the quotation to develop an insightful interpretation about an aspect of the exhibit.

- Reflect on the particular lens idea more deeply i.e. complicate it, extend its scope, or raise a new question that you will address next in your analysis, if applicable.

Writing About Literature Copyright © by Rachael Benavidez and Kimberley Garcia is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Skip to content

Davidson Writer

Academic Writing Resources for Students

Main navigation

Literary analysis: applying a theoretical lens.

A common technique for analyzing literature (by which we mean poetry, fiction, and essays) is to apply a theory developed by a scholar or other expert to the source text under scrutiny. The theory may or may not have been developed in the service literary scholarship. One may apply, say, a Marxist theory of historical materialism to a novel, or a Freudian theory of personality development to a poem. In the hands of an analyst, another’s theory (in parts or whole) acts as a conceptual lens that when brought to the material brings certain elements into focus. The theory magnifies aspects of the text according to its special interests. The term theory may sound rarified or abstract, but in reality a theory is simply an argument that attempts to explain something. Anytime you go to analyze literature—as you attempt to explain its meanings—you are applying theory, whether you recognize its exact dimensions or not. All analysis proceeds with certain interests, desires, and commitments (and not others) in mind. One way to define the theory—implicit or explicit—that you bring to a text is to ask yourself what assumptions (for instance, about how stories are told, about how language operates aesthetically, or about the quality of characters’ actions) guide your findings. A theory is an argument that attempts to explain something.

Let’s turn again to the insights about using theories to analyze literature provided in Joanna Wolfe’s and Laura Wilder’s Digging into Literature: Strategies for Reading, Analysis, and Writing (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016).

Here’s a brief example of a writer using a theoretical text as a lens for reading the primary text :

In her book, The Second Sex , the feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir describes how many mothers initially feel indifferent toward and estranged from their new infants, asserting that though “the woman would like to feel that the new baby is surely hers as is her own hand,. . . she does not recognize him because. . .she has experienced her pregnancy without him: she has no past in common with this little stranger” (507). Sylvia Plath’s “Morning Song” exemplifies the indifference and estrangement that de Beauvoir describes. However, where de Beauvoir asserts that “a whole complex of economical and sentimental considerations makes the baby seem either a hindrance or a jewel” (510), Plath’s poem illustrates how a child can simultaneously be both hindrance and jewel. Ultimately, “Morning Song” shows us how new mothers can overcome the conflicting emotions de Beauvoir describes.

Daniel DiGiacomo. From Mourning Song to “Morning Song”: The Maturation of a Maternal Bond.

Notice that in this brief passage, the writer fairly represents de Beauvoir’s theory about maternal feelings, then goes on to apply a portion of that theory to Plath’s poem, a focusing move that establishes the writer’s special interest in an aspect of Plath’s text. In this case, the application yields new insight about the non-universality of de Beauvoir’s theory, which Plath’s poem troubles. The theory magnifies a portion of the primary text, and its application puts pressure on the soundness of the theory.

Applying a Theoretical Lens: W.E.B. Du Bois Applied to Langston Hughes

Experienced literary critics are familiar with a wide range of theoretical texts they can use to interpret a primary text. As a less experienced student, your instructors will likely suggest pairings of theoretical and primary texts. We would like you to consider the writerly workings of the theory-primary text application by examining a student’s paper entitled “Double-consciousness in ‘Theme for English B,” an essay which uses W.E.B. Du Bois’s theory (of double-consciousness ) to elucidate and interpret Langston Hughes’s poem (“Theme for English B”). W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963) was an American sociologist, civil rights activist, author, and editor. Langston Hughes (1902-1967) was an American poet, activist, editor, and guiding member of the group of artists now known as the Harlem Renaissance.

But before you can make sense of that student’s essay, we ask that you read both a synopsis of the theoretical text and the primary text .

Primary Text

The instructor said,

Go home and write a page tonight.

And let that page come out of you—

Then, it will be true.

I wonder if it’s that simple?

I am a twenty-two, colored, born in Winston-Salem.

I went to school there, then Durham, then here

to this college on the hill above Harlem,

I am the only colored student in my class.

The steps from the hill lead down into Harlem through a park, then I cross St. Nicholas,

Eighth Avenue, Seventh, and I come to the Y,

the Harlem Branch Y, where I take the elevator

up to my room, site down, and write this page:

It’s not easy to know what is true for you or me

at twenty-two, my age. But I guess I’m what

I feel and see and hear, Harlem, I hear you:

hear you, hear me—we two—you, me, talk on this page.

(I hear New York, too.) Me—who?

Well, I like to eat, sleep, drink, and be in love.

I like to work, read, learn, and understand life.

I like a pipe for a Christmas present,

or records—Bessie, bop, or Bach.

I guess being colored doesn’t make me not like

the same things other folks like who are other races.

So will my page be colored that I write?

Being me, it will not be white.

But it will be a part of you, instructor.

You are white—

yet a part of me, as I am a part of you.

That’s American.

Sometimes perhaps you don’t want to be a part of me.

Nor do I often want to be a part of you.

But we are, that’s true!

As I learn from you,

I guess you learn from me—

although you’re older—and white—

and somewhat more free.

Theoretical Text

W.E.B. Du Bois

Of Our Spiritual Strivings

O water, voice of my heart, crying in the sand,

All night long crying with a mournful cry,

As I lie and listen, and cannot understand

The voice of my heart in my side or the voice of the sea.

O water, crying for rest, is it I, is it I?

All night long the water is crying to me.

Unresting water, there shall never be rest

Till the last moon drop and the last tide fall,

And the fire of the end begin to burn in the west;

And the heart shall be weary and wonder and cry like the sea,

All life long crying without avail

As the water all nigh long is crying to me.

—Arthur Symons

Between me and the other world there is an unasked question: unasked by some through feelings of delicacy; by others through the difficulty of rightly framing it. All, nevertheless, flutter round it. They approach me in a half-hesitant sort of way, eye me curiously or compassionately, and then, instead of saying directly, How does it feel to be a problem? they say, I know an excellent colored man in my town; or I fought at Mechanicsville; or Do not these Southern outrages make your blood boil? At these I smile, or am interested, or reduce the boiling to a simmer, as the occasion may require. To the real question, How does it feel to be a problem? I answer seldom a word.

And yet, being a problem is a strange experience—peculiar even for one who has never been anything else, save perhaps in babyhood and in Europe. It is in the early days of rollicking boyhood that the revelation first bursts upon one, all in a day, as it were. I remember well when the shadow swept across me. I was a little thing, away up in the hills of New England, where the dark Housatonic winds between Hoosac and Taghkanic to the sea. In a wee wooden schoolhouse, something put it into the boys’ and girls’ heads to buy gorgeous visiting-cards—ten cents a package—and exchange. The exchange was merry, till one girl, a tall newcomer, refused my card—refused it peremptorily, with a glance. Then it dawned upon me with a certain sadness that I was different from the others; or, like, mayhap, in heart and life and longing, but shut out from their world as by a vast veil. I had thereafter no desire to tear down that veil, to creep through; I held all beyond it in common contempt, and lived above it in a region of blue sky and great wandering shadows. That sky was bluest when I could beat my mates at examination time, or beat them at a footrace, or even beat their stringy heads. Alas, with the hears all this fine contempt began to fade; for the worlds I long for, and all their dazzling opportunities, were theirs, not mine. But they should not keep these prizes, I said; some, all, I would wrest from them. Just how I would do it I could never decide: by reading law, by healing the sick, by telling the wonderful tales that swam in my head—some way. With other black boys the strife was not so fiercely sunny: their youth shrunk into tasteless sycophancy, or into silent hatred of the pale world about them and mocking distrust of everything white, or wasted itself in a bitter cry, Why did God make me an outcast and a stranger in mine own house? The shades of the prison-house closed round about us all: walls strait and stubborn to the whitest, but relentlessly narrow, tall, and unscalable to sons of night who must plod darkly on in resignation, or beat unavailing palms against the stone, or steadily, half hopelessly, watch the streak of blue above.

After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world, a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his tw0-ness, an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strengths alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife, this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. In this merging he wishes neither of the older selves to be lost. He would not Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa. He would not bleach his Negro soul in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of Opportunity closed roughly in his face.

This, then, is the end of his striving: To be a coworker in the kingdom of culture, to escape both death and isolation, to husband and use his best powers and his latent genius. These powers of body and mind have in the past been strangely wasted, dispersed, or forgotten. The shadow of a might Negro past flits through the tale of Ethiopia the Shadowy and of Egypt the Sphinx. Throughout history, the powers of single black men flash here and there like falling stars, and die sometimes before the world has rightly gauged their brightness. Here in America, in the few days since Emancipation, the black man’s turning hither and thither in hesitant and doubtful striving has often made his very strength to loos effectiveness, to seem like absence of power, like weakness. And yet it is not weakness—it is the contradiction of double aims. The double-aimed struggle of the black artisan—on the one hand to escape white contempt for a nation of mere hewers of wood and drawers of water, and on the other hand to plough and nail and dig for a poverty-stricken horde—could only result in making him a poor craftsman, for he had but half a heart either cause. By the poverty and ignorance of his people, the Negro minister or doctor was tempted toward quackery and demagogy; and by the criticism of the other world, toward ideals that made him ashamed of his lowly tasks. The would-be black savant was confronted by the paradox that the knowledge his people needed was a twice-told tale to his white neighbors, while the knowledge which would teach the white world was Greek to his own flesh and blood. The innate love of harmony and beauty that set the ruder souls of his people a-dancing and a-singing raised but confusion and doubt in the soul of the black artist; for the beauty revealed to him was the soul-beauty of a race which his larger audience despised, and he could not articulate the message of another people. This waste of double aims, this seeking to satisfy two unreconciled ideals, has wrought sad havoc with the courage and faith and deeds of ten thousand thousand people—has sent them often wooing false gods and invoking false means of salvation, and at times has even seemed about to make them ashamed of themselves.

Away back in the days of bondage they thought to see in one divine event the end of all doubt and disappointment; few men ever worshipped Freedom with half such unquestioning faither as did the American Negro for two centuries. To him, so far as he thought and dreamed, slavery was indeed the sum of all villainies, the cause of all sorrow, the root of all prejudice; Emancipation was the key to a promised land of sweeter beauty than ever stretched before the eyes of wearied Israelites. In song and exhortation swelled one refrain—Liberty; in his tears and curses the God he implored had Freedom in his right hand. At last it came—suddenly, fearfully, like a dream. With one wild carnival of blood and passion came the message in his own plaintive cadences:—

“Shout, O children!

Shout, you’re free!

For God has bought your liberty!”

Years have passed away since then—ten, twenty, forty; forty years of national life, forty years of renewal and development, and yet the swarthy scepter sits in its accustomed seat at the Nation’s feast. In vain do we cry to this our vastest social problem:—

“Take any shape but that, and my firm nerves

Shall never tremble!”

The Nation has not yet found peace from its since; the freedman has not yet found in freedom his promised land. Whatever of good may have come in these years of change, the shadow of a deep disappointment rests upon the Negro people—a disappointment all the more bitter because the unattained ideal was unbounded save by the simple ignorance of a lowly people.

The first decade was merely a prolongation of the vain search for freedom, the boon that seemed ever barely to elude their grasp—like a tantalizing will-o-the-wisp, maddening and misleading the headless host. The holocaust of war, the terrors of the Ku Klux Klan, the lies of carpetbaggers, the disorganization of industry, and the contradictory advice of friends and foes, left the bewildered serf with no new watchword beyond the old cry for freedom. As the time flew, however, he began to grasp a new idea. The ideal of liberty demanded for its attainment powerful means, and these the Fifteenth Amendment gave him. The ballot, which before he had looked upon as a visible sign of freedom, he now regarded as the chief means of gaining and perfecting the liberty with which war had partially endowed him. And why not? Had not votes made war and emancipated millions? Had not votes enfranchised the freedmen? Was anything impossible to a power that had done all this? A million black men started with renewed zeal to vote themselves into the kingdom. So the decade flew away, the revolution of 1876 came, and left the half-free serf weary, wondering, but still inspired. Slowly but steadily, in the following years, a new vision began gradually to replace the dream of political power—a powerful movement, the rise of another ideal to guide the unguided, another pillar of fire by night after a clouded day. It was the ideal of “book-learning”: the curiosity, born of compulsory ignorance, to know and test the power of the cabalistic letters of the white man, the longing to know. Here at last seemed to have been discovered the mountain path to Canaan; longer than the highway to Emancipation and law, steep and rugged, but straight, leading to heights high enough to overlook life.

Up the new path the advance guard toiled, slowly, heavily, doggedly; only those who have watched and guided the faltering feet, the misty minds, the dull understandings, of the dark pupils of these schools know how faithfully, how piteously, this people strove to learn. It was weary work. The cold statistician wrote down the inches of progress here and there, noted also where here and there a foot had slipped or someone fallen. To the tired climbers, the horizon was ever dark, the mists were often cold, the Canaan was always dim and far away. If, however, the vistas disclosed as yet no goal, no resting place, little but flattery and criticism, the journey at least gave leisure for reflection and self-examination; it changed the child of Emancipation to the youth with dawning self-consciousness, self-realization, self-respect. In those somber forests of his striving his own soul rose before him, and he saw himself—darkly as through a veil; and yet he saw in himself some faint revelation of his power, of his mission. He began to have a dim feeling that, to attain his place in the world, he must be himself, and not another. For the first time he sought to analyze the burden he bore upon his back, that deadweight of social degradation partially masked behind a half-named Negro problem. He felt his poverty; without a cent, without a home, without land, tools, or savings, he had entered into competition with rich, landed, skilled neighbors. To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships. He felt the weight of his ignorance,—not simply of letters, but of life, of business, of the humanities; the accumulated sloth and shirking and awkwardness of decades and centuries shackled his hands and feet. Nor was his burden all poverty and ignorance. The red stain of bastardy, which two centuries of systematic legal defilement of Negro women had stamped upon his race, meant not only the loss of ancient African chastity, but also the hereditary weight of a mass of corruption from white adulterers, threatening almost the obliteration of the Negro home.

A people thus handicapped ought not to be asked to race with the world, but rather allowed to give all its time and thought to its own social problems. But alas! while sociologists gleefully count his bastards and prostitutes, the very soul of the toiling, sweating black man is darkened by the shadow of a vast despair. Men call the shadow prejudice, and learnedly explain it as the natural defense of culture against barbarism, learning against ignorance, purity against crime, the “higher” against the lower races. To which the Negro cries Amen! and swears that to such much of this strange prejudice as is founded on just homage to civilization, culture, righteousness, and progress, he humbly bows and meekly does obeisance. But before that nameless prejudice that leaps beyond all this he stands helpless, dismayed, and well-nigh speechless; before that personal disrespect and mockery, the ridicule and systematic humiliation, the distortion of fact and wanton license of fancy, the cynical ignoring of the better and the boisterous welcoming of the worse, the all-pervading desire to inculcate disdain for everything b lack, from Toussaint to the devil—before this there rises a sickening despair that would disarm and discourage any nation save the black host to whom “discouragement” is an unwritten word.

But the facing of so vast a prejudice could not but bring the inevitable self-questioning, self-disparagement, and lowering of ideals which ever accompany repression and breed in an atmosphere of contempt and hate. Whisperings and portents came borne upon the four winds: Lo! we are diseased and dying, cried the dark hosts; we cannot write, our voting is vain; what we need of education, since we must always cook and serve? And the Nation echoed and enforced this self-criticism, saying: Be content to be servants, and nothing more; what need of higher culture for half-men? Away with the black man’s ballot, by force or fraud—and behold the suicide or a race! Nevertheless, out of the evil came something of good—the more careful adjustment of education to real life, the clearer perception of the Negroes’ social responsibilities, and the sobering realization of the meaning of progress.

So dawned the time of Sturm und Drang: storm and stress today rocks out little boat on the mad waters of the world-sea; there is within and without the sound of conflict, the burning of body and rending of soul; inspiration strives without doubt, and faith with vain questionings. The bright ideals of the past—physical freedom, political power, the training of brains and the training of hands—all these in turn have waxed and waned, until even the last grows dim and overcast. Are they all wrong—all false? No, not that, but each alone was oversimple and incomplete—the dreams of a credulous race-childhood, or the fond imaginings of the other world which does not know and does not want to know our power. To be really true, all these ideals must be melted and welded into one. The training of the schools we need today more than ever—the training of deft hands, quick eyes and ears, and above all the broader, deeper, higher culture of gifted minds and pure hearts. The power of the ballot we need in sheer self-defense—else what shall save us from a second slavery? Freedom, too, the long-sought, we still seek—the freedom of life and limb, the freedom to work and think, the freedom to love and aspire. Work, culture, liberty—all these we need, not singly but together, not successively but together, each growing and aiding each, and all striving toward that vaster ideal that swims before the Negro people, the ideal of human brotherhood, gamed through the unifying ideal of Race; the idea of fostering and developing the traits and talents of the Negro, not in opposition to or contempt for other race, but rather in large conformity to the greater ideals of the American Republic, in order that someday on American soil two world races may give each to each those characteristics both so sadly lack. We the darker ones come even now not altogether empty-handed: there are today no truer exponents of the pure human spirit of the Declaration of Independence than the American Negroes; there is not true American music but the wild sweet melodies of the Negro slave; the American fairy tales and folklore are Indian and African; and, all in all, we black men seem the sole oasis of simple faith and reverence in a dusty desert of dollars and smartness. Will American be poorer if she replace her brutal dyspeptic blundering with light-hearted but determined Negro humility? of her coarse and cruel wit with loving jovial good-humor? or her vulgar music with the soul of the Sorrow Songs?

Merely a concrete test of the underlying principles of the great republic is the Negro Problem, and the spiritual striving of the freedmen’s sons is the travail of souls whose burden is almost beyond the measure of their strength, but who bear it in the name of an historic race, in the name of this the land of their fathers’ fathers, and in the name of human opportunity.

Using a Theoretical Lens to Write Persuasively

Applying a theoretical lens to poetry, fiction, plays, or essays is a standard academic move, but theories are also frequently applied to real-world cases, hypothetical cases, and other non-fiction texts in disciplines such as Philosophy, Sociology, Education, Anthropology, History, or Political Science. Sometimes, the theoretical lens analysis is called a reading , as in a “Kantian reading of an ethical dilemma,” or a “Marxist reading of an historical episode.” At other times, the application of a theory is known as an approach , as in a “Platonic approach to the question of beauty.”

The basic writerly moves to using a theoretical lens include:

- name and cite the theoretical text and accurately summarize this text’s argument. Usually this short summary appears in one or two paragraphs at the beginning of the essay. You will want to be sure your summary includes the key concepts you use in your paper to analyze the primary literary text.

- use the surface/depth strategy to show how deeper meanings in the primary text can be explained by concepts from the theoretical text. You might think about this as creating a “match argument” between the primary and theoretical text (or case under consideration). Take important points made in the theoretical argument and match them to particular events or descriptions in the primary text. For instance, you could argue Langston Hughes’s line So will my page be colored as I write? (27) matches Du Bois’s argument that the veil prevents Whites from seeing Black’s individuality. Such a match argument can form an organizing structure for the essay as you develop whole paragraphs to support different points of connection between the theoretical and primary texts. You may be able to devote an entire paragraph to the claim that Du Bois’s concept of “the veil” can help us understand Hughes’s description of the challenges his speaker faces in asking his instructor to see him on his own terms.

- support your surface/depth claims linking the primary and theoretical texts with textual evidence from the primary text . If you claim that a particular passage exemplifies a particular theory, you need to provide evidence in the form of quotations or paraphrases to support this interpretation. This evidence will most certainly need to be provided from the primary text you are analyzing but perhaps also occasionally from the theoretical text, too, especially if you connect the primary text to a small detail in the theoretical text or if the wording of the theoreticl text helps you explain something in the primary text. Use the patterns strategy to provide multiple examples from the primary text supporting your claims that it matches elements of the theoretical text.

- reveal something complex and unexpected about the primary text. The goal of the theoretical lens strategy—like all strategies of literary analysis—should be to show that the text you are analyzing is complex and can be understood on multiple levels.

- challenge, extend, or reevaluate the theoretical text (for more sophisticated analyses). The most sophisticated uses of the theoretical lens strategy not only help you better understand the primary text but also help you better understand—and reveal complexities in—the theoretical text. When you first start applying this strategy, it may be sufficient to argue how the theoretical text helps you understand the primary text, but as you advance, you should attempt the second part of this strategy and use the primary text to extend or challenge the theoretical argument. Such arguments may serve as starting points for you to contribute to literary (or philosophical, or sociological, or historical) theory as a theorist yourself. These arguments are often made in the concluding paragraphs of analyses using the theoretical lens strategy.

Common Words and Phrases Associated with Theoretical Lens

A Sample Student Essay

Title: Double-consciousness in “Theme for English B”

Paragraph 1

The post-slavery history of African-Americans in the United States has been one of struggle for recognition. This struggle continued through the civil rights movement in the 1970s and ’80s. W.E.B. Du Bois, one of the most influential African-American leaders of the early twentieth century, described the complicated effects racism had on African-American selfhood. In his treatise The Souls of Black Folk , Du Bois introduces the term “double-consciousness” to describe African-Americans’s struggle for self-recognition. Double-consciousness is the sense of “always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others” (8). It means that an African-American “[e]ver feels his two-ness—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body” (8). According to Du Bois, double-consciousness means that African-Americas are always judging themselves through a veil of racism, experiencing how others judge and define them rather than how they might define and express themselves.

Paragraph 2

Langston Hughes’s poem “Theme for English B,” written nearly fifty years after Du Bois’s essay, depicts one African-American’s continued struggle with double-consciousness. However, where Du Bois sees double-consciousness as a painful condition he hopes will one day disappear, Hughes seems to have a more positive view, suggesting that mainstream Americans should also have an opportunity to experience this condition. Instead of eradicating double-consciousness, Hughes seeks to universalize it. His poem suggests that true equality will be possible when all cultures are able to experience and appreciate double-consciousness.

Paragraph 3

We see the poem’s speaker struggling with double-consciousness when he expresses difficulty articulating what is “true” for himself. Hughes writes:

It’s not easy to know what is true for you and me

I feel and see and hear. Harlem, I hear you:

(I hear New York, too.) Me—who? (16-20)

In this passage, which concludes with a question about who he is, the speaker expresses a divided self. At first, he seems to identify with Harlem, an African-American neighborhood in New York, where he is currently sitting and writing. However, this identification becomes troubled by his acknowledgment that Harlem does not completely define him. When the speaker writes “hear you, hear me—we two” (19), he suggests that “you” (referring to Harlem) and “me” (referring to himself) are intimately related by not identical. They are two voices that, while both present in his poem, still “talk” (19) to one another. The fact that these voices converse, rather than speak as one, indicates they are not completely merged.

Paragraph 4

This sense of a divided self is further reinforced by the claim “(I hear New York, too.)” (20). This aside is interesting because it establishes Harlem as both separate from and connected to the larger city. This division reflects what Du Bois calls the “two-ness [of being] an Amercan [and] a Negro” (8). By placing New York in parentheses, the speaker may be suggesting that the American part of himself represented by New York plays a weaker role in his identity than the African-American self represented by Harlem. Like Du Bois, the speaker in “Theme for English B” experiences inner conflict when he tries to reconcile the different parts of himself.

Paragraph 5

We further see evidence of the speaker’s conflict when he writes that he likes “Bessie, bop, or Bach” (24). “Bessie” refrs to the popular blues singer Bessie Smith, an African-American woman who sang a very African-American style of music. At the other end of the spectrum is “Bach,” which refers to the classical European composer J.S. Bach and represents a traditionally White form of music. In the middle is “bop,” which refers to “bebop,” a form of jazz made popular in the 1940s that inspired a particular form of dance most practiced by White teenagers at the time. In saying that he likes all of these forms of music, the speaker indicates that he is a mix of both African and European identities—like Du Bois, he feels both traditional White and traditional African-American culture calling him.

Paragraph 6