Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

19.3 The Economics of Discrimination

Learning objectives.

- Define discrimination, identify some sources of it, and illustrate Becker’s model of discrimination using demand and supply in a hypothetical labor market.

- Assess the effectiveness of government efforts to reduce discrimination in the United States.

We have seen that being a female head of household or being a member of a racial minority increases the likelihood of being at the low end of the income distribution and of being poor. In the real world, we know that on average women and members of racial minorities receive different wages from white male workers, even though they may have similar qualifications and backgrounds. They might be charged different prices or denied employment opportunities. This section examines the economic forces that create such discrimination, as well as the measures that can be used to address it.

Discrimination in the Marketplace: A Model

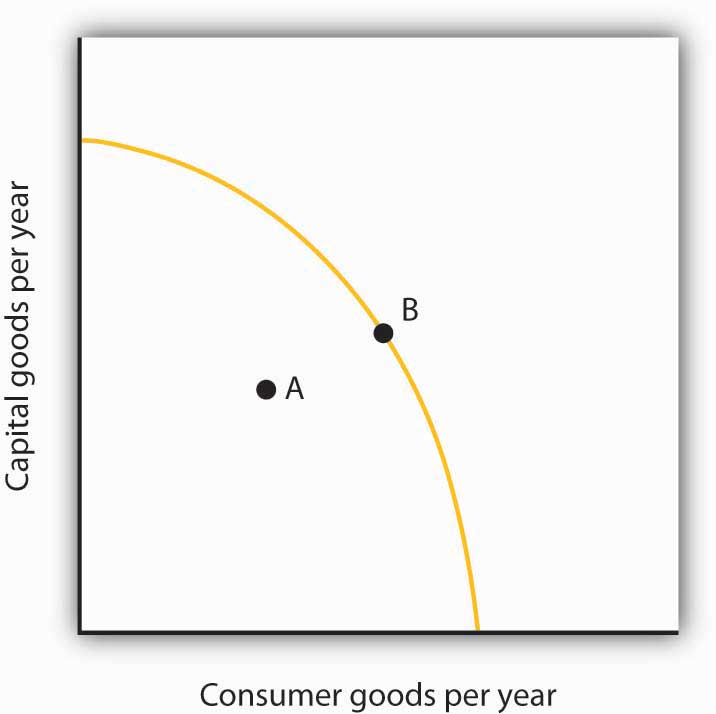

Discrimination occurs when people with similar economic characteristics experience different economic outcomes because of their race, sex, or other noneconomic characteristics. A black worker whose skills and experience are identical to those of a white worker but who receives a lower wage is a victim of discrimination. A woman denied a job opportunity solely on the basis of her gender is the victim of discrimination. To the extent that discrimination exists, a country will not be allocating resources efficiently; the economy will be operating inside its production possibilities curve.

Pioneering work on the economics of discrimination was done by Gary S. Becker, an economist at the University of Chicago, who won the Nobel Prize in economics in 1992. He suggested that discrimination occurs because of people’s preferences or attitudes. If enough people have prejudices against certain racial groups, or against women, or against people with any particular characteristic, the market will respond to those preferences.

In Becker’s model, discriminatory preferences drive a wedge between the outcomes experienced by different groups. Discriminatory preferences can make salespeople less willing to sell to one group than to another or make consumers less willing to buy from the members of one group than from another or to make workers of one race or sex or ethnic group less willing to work with those of another race, sex, or ethnic group.

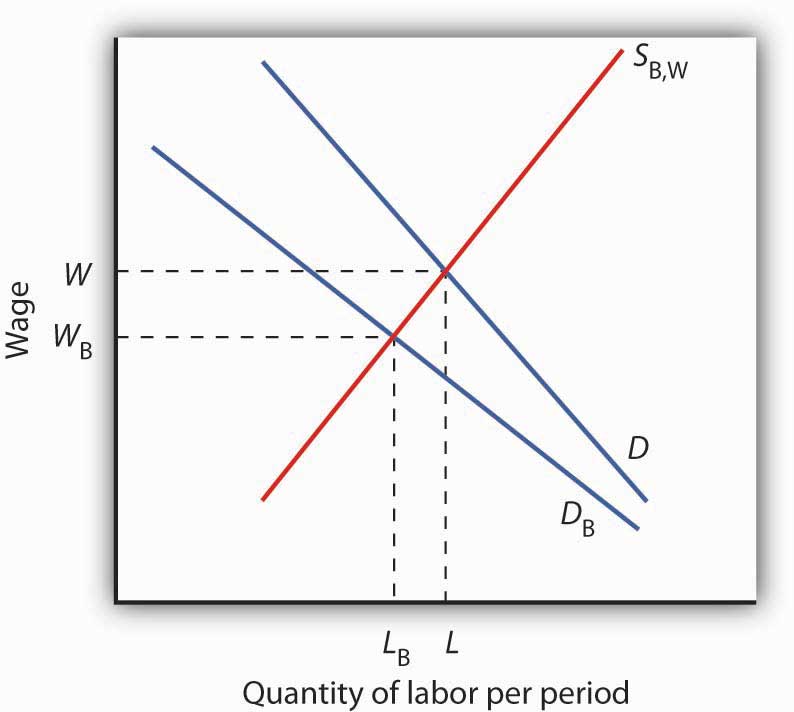

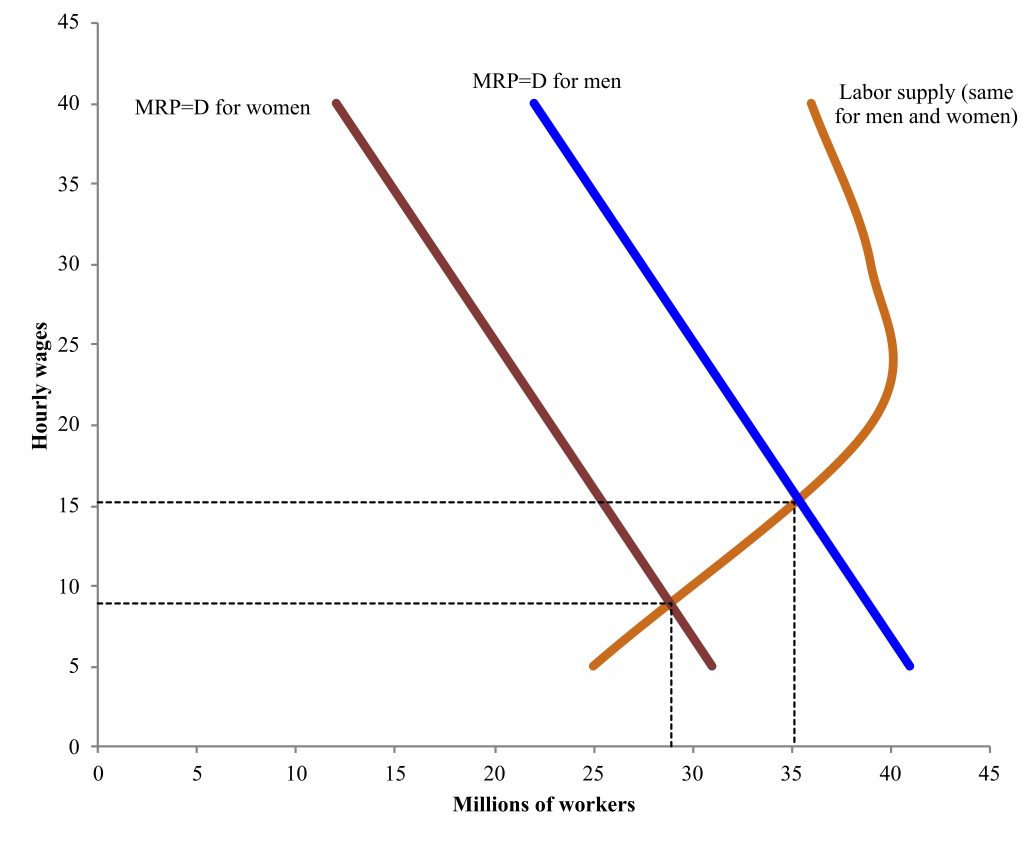

Let us explore Becker’s model by examining labor-market discrimination against black workers. We begin by assuming that no discriminatory preferences or attitudes exist. For simplicity, suppose that the supply curves of black and white workers are identical; they are shown as a single curve in Figure 19.11 “Prejudice and Discrimination” . Suppose further that all workers have identical marginal products; they are equally productive. In the absence of racial preferences, the demand for workers of both races would be D . Black and white workers would each receive a wage W per unit of labor. A total of L black workers and L white workers would be employed.

Figure 19.11 Prejudice and Discrimination

If employers, customers, or employees have discriminatory preferences, and those preferences are widespread, then the marketplace will result in discrimination. Here, black workers receive a lower wage and fewer of them are employed than would be the case in the absence of discriminatory preferences.

Now suppose that employers have discriminatory attitudes that cause them to assume that a black worker is less productive than an otherwise similar white worker. Now employers have a lower demand, D B , for black than for white workers. Employers pay black workers a lower wage, W B , and employ fewer of them, L B instead of L , than they would in the absence of discrimination.

Sources of Discrimination

As illustrated in Figure 19.11 “Prejudice and Discrimination” , racial prejudices on the part of employers produce discrimination against black workers, who receive lower wages and have fewer employment opportunities than white workers. Discrimination can result from prejudices among other groups in the economy as well.

One source of discriminatory prejudices is other workers. Suppose, for example, that white workers prefer not to work with black workers and require a wage premium for doing so. Such preferences would, in effect, raise the cost to the firm of hiring black workers. Firms would respond by demanding fewer of them, and wages for black workers would fall.

Another source of discrimination against black workers could come from customers. If the buyers of a firm’s product prefer not to deal with black employees, the firm might respond by demanding fewer of them. In effect, prejudice on the part of consumers would lower the revenue that firms can generate from the output of black workers.

Whether discriminatory preferences exist among employers, employees, or consumers, the impact on the group discriminated against will be the same. Fewer members of that group will be employed, and their wages will be lower than the wages of other workers whose skills and experience are otherwise similar.

Race and sex are not the only characteristics that affect hiring and wages. Some studies have found that people who are short, overweight, or physically unattractive also suffer from discrimination, and charges of discrimination have been voiced by disabled people and by homosexuals. Whenever discrimination occurs, it implies that employers, workers, or customers have discriminatory preferences. For the effects of such preferences to be felt in the marketplace, they must be widely shared.

There are, however, market pressures that can serve to lessen discrimination. For example, if some employers hold discriminatory preferences but others do not, it will be profit enhancing for those who do not to hire workers from the group being discriminated against. Because workers from this group are less expensive to hire, costs for non-discriminating firms will be lower. If the market is at least somewhat competitive, firms who continue to discriminate may be driven out of business.

Discrimination in the United States Today

Reacting to demands for social change brought on most notably by the civil rights and women’s movements, the federal government took action against discrimination. In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court rendered its decision that so-called separate but equal schools for black and white children were inherently unequal, and the Court ordered that racially segregated schools be integrated. The Equal Pay Act of 1963 requires employers to pay the same wages to men and women who do substantially the same work. Federal legislation was passed in 1965 to ensure that minorities were not denied the right to vote.

Congress passed the most important federal legislation against discrimination in 1964. The Civil Rights Act barred discrimination on the basis of race, sex, or ethnicity in pay, promotion, hiring, firing, and training. An Executive Order issued by President Lyndon Johnson in 1967 required federal contractors to implement affirmative action programs to ensure that members of minority groups and women were given equal opportunities in employment. The practical effect of the order was to require that these employers increase the percentage of women and minorities in their work forces. Affirmative action programs for minorities followed at most colleges and universities.

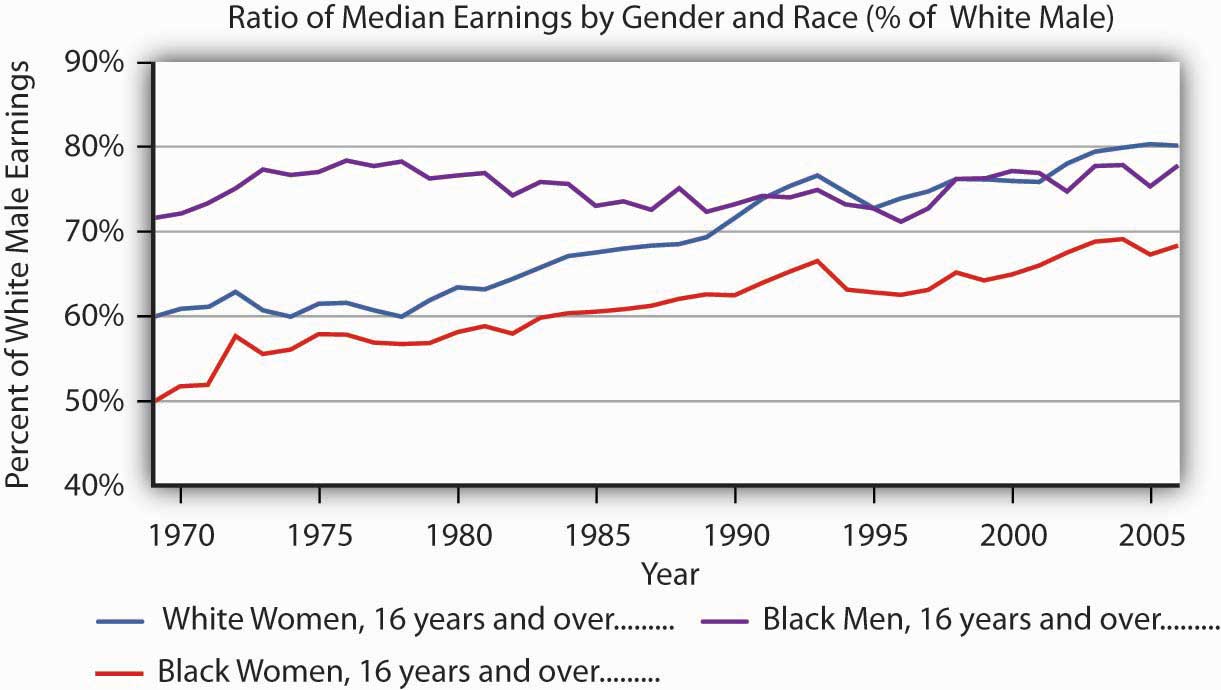

What has been the outcome of these efforts to reduce discrimination? A starting point is to look at wage differences among different groups. Gaps in wages between males and females and between blacks and whites have fallen over time. In 1955, the wages of black men were about 60% of those of white men; in 2005, they were 75% of those of white men. For black men, the reduction in the wage gap occurred primarily between 1965 and 1973. In contrast, the gap between the wages of black women and white men closed more substantially, and progress in closing the gap continued after 1973, albeit at a slower rate. Specifically, the wages of black women were about 35% of those of white men in 1955, 58% in 1975, and 67% in the 2005. For white women, the pattern of gain is still different. The wages of white women were about 65% of those of white men in 1955, and fell to about 60% from the mid-1960s to the late 1970s. The wages of white females relative to white males did improve, however, over the last 40 years. In 2005, white female wages were 80% of white male wages. While there has been improvement in wage gaps between black men, black women, and white women vis-à-vis white men, a substantial gap still remains. Figure 19.12 “The Wage Gap” shows the wage differences for the period 1969–2006.

Figure 19.12 The Wage Gap

The exhibit shows the wages of white women, black women, and black men as a percentage of the wages of white men from 1969–2005. As you can see, the gap has closed considerably, but there remains a substantial gap between the wages of white men and those of other groups in the economy. Part of the difference is a result of discrimination.

Source: Table 16. Median usual weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary workers, by sex, age, race and Hispanic origin, quarterly average (not seasonally adjusted) and annual averages, 1970–2006. For years after 1979, http://www.bls.gov/cps/wlf-table_16-2007.pdf

One question that economists try to answer is the extent to which the gaps are due to discrimination per se and the extent to which they reflect other factors, such as differences in education, job experience, or choices that individuals in particular groups make about labor-force participation. Once these factors are accounted for, the amount of the remaining wage differential due to discrimination is less than the raw differentials presented in Figure 19.12 “The Wage Gap” would seem to indicate.

There is evidence as well that the wage differential due to discrimination against women and blacks, as measured by empirical studies, has declined over time. For example, a number of studies have concluded that black men in the 1980s and 1990s experienced a 12 to 15% loss in earnings due to labor-market discrimination (Darity, W. A., and Patrick L. Mason, 1998). University of Chicago economist James Heckman denies that the entire 12% to 15% differential is due to racial discrimination, pointing to problems inherent in measuring and comparing human capital among individuals. Nevertheless, he reports that the earnings loss due to discrimination similarly measured would have been between 30 and 40% in 1940 and still over 20% in 1970 (Heckman, J. J., 1998).

Can civil rights legislation take credit for the reductions in labor-market discrimination over time? To some extent, yes. A study by Heckman and John J. Donohue III, a law professor at Northwestern University, concluded that the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act, as well as other civil rights activity leading up to the act, had the greatest positive impact on blacks in the South during the decade following its passage. Evidence of wage gains by black men in other regions of the country was, however, minimal. Most federal activity was directed toward the South, and the civil rights effort shattered an entire way of life that had subjugated black Americans and had separated them from mainstream life (Donohue III, J. J. and James Heckman, 1991).

In recent years, affirmative action programs have been under attack. Proposition 209, passed in California in 1996, and Initiative 200, passed in Washington State in 1998, bar preferential treatment due to race in admission to public colleges and universities in those states. The 1996 Hopwood case against the University of Texas, decided by the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, eliminated the use of race in university admissions, both public and private, in Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Then Supreme Court decisions in 2003 concerning the use of affirmative action at the University of Michigan upheld race conscious admissions, so long as applicants are still considered individually and decisions are based of multiple criteria.

Controversial research by two former Ivy League university presidents, political scientist Derek Bok of Harvard University and economist William G. Bowen of Princeton University, concluded that affirmative action policies have created the backbone of the black middle class and taught white students the value of integration. The study focused on affirmative action at 28 elite colleges and universities. It found that while blacks enter those institutions with lower test scores and grades than those of whites, receive lower grades, and graduate at a lower rate, after graduation blacks earn advanced degrees at rates identical to those of their former white classmates and are more active in civic affairs (Bok, D., and William G. Bowen, 1998).

While stricter enforcement of civil rights laws or new programs designed to reduce labor-market discrimination may serve to further improve earnings of groups that have been historically discriminated against, wage gaps between groups also reflect differences in choices and in “premarket” conditions, such as family environment and early education. Some of these premarket conditions may themselves be the result of discrimination.

The narrowing in wage differentials may reflect the dynamics of the Becker model at work. As people’s preferences change, or are forced to change due to competitive forces and changes in the legal environment, discrimination against various groups will decrease. However, it may be a long time before discrimination disappears from the labor market, not only due to remaining discriminatory preferences but also because the human capital and work characteristics that people bring to the labor market are decades in the making. The election of Barack Obama as president of the United States in 2008 is certainly a hallmark in the long and continued struggle against discrimination.

Key Takeaways

- Discrimination means that people of similar economic characteristics experience unequal economic outcomes as a result of noneconomic factors such as race or sex.

- Discrimination occurs in the marketplace only if employers, employees, or customers have discriminatory preferences and if such preferences are widely shared.

- Competitive markets will tend to reduce discrimination if enough individuals lack such prejudices and take advantage of discrimination practiced by others.

- Government intervention in the form of antidiscrimination laws may have reduced the degree of discrimination in the economy. There is considerable disagreement on this question but wage gaps have declined over time in the United States.

Use a production possibilities curve to illustrate the impact of discrimination on the production of goods and services in the economy. Label the horizontal axis as consumer goods per year. Label the vertical axis as capital goods per year. Label a point A that shows an illustrative bundle of the two which can be produced given the existence of discrimination. Label another point B that lies on the production possibilities curve above and to the right of point A. Use these two points to describe the outcome that might be expected if discrimination were eliminated.

Case in Point: Early Intervention Programs

Figure 19.13

Navy Hale Keiki School – Kindergarten – CC BY 2.0.

Many authors have pointed out that differences in “pre-market” conditions may drive observed differences in market outcomes for people in different groups. Significant inroads to the reduction of poverty may lie in improving the educational opportunities available to minority children and others living in poverty-level households, but at what point in their lives is the pay-off to intervention the largest? Professor James Heckman, in an op-ed essay in The Wall Street Journal , argues that the key to improving student performance and adult competency lies in early intervention in education.

Professor Heckman notes that spending on children after they are already in school has little impact on their later success. Reducing class sizes, for example, does not appear to promote gains in factors such as attending college or earning higher incomes. What does seem to matter is earlier intervention. By the age of eight , differences in learning abilities are essentially fixed. But, early intervention to improve cognitive and especially non-cognitive abilities (the latter include qualities such as perseverance, motivation, and self-restraint) has been shown to produce significant benefits. In an experiment begun several decades ago known as the Perry intervention, four-year-old children from disadvantaged homes were given programs designed to improve their chances for success in school. Evaluations of the program 40 years later found that it had a 15 to 17% rate of return in terms of the higher wages earned by men and women who had participated in the program compared to those from similar backgrounds who did not—the program’s benefit-cost ratio was 8 to 1. Professor Heckman argues that even earlier intervention among disadvantaged groups would be desirable—perhaps as early as six months of age.

Economists Rob Grunewald and Art Rolnick of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis have gone so far as to argue that, because of the high returns to early childhood development programs, which they estimate at 12% per year to the public, state and local governments, can promote more economic development in their areas by supporting early childhood programs than they currently do by offering public subsidies to attract new businesses to their locales or to build new sports stadiums, none of which offers the prospects of such a high rate of return.

Sources: James Heckman, “Catch ’em Young,” The Wall Street Journal , January 10, 2006, p. A-14; Rob Grunewald and Art Rolnick, “Early Childhood Development on a Large Scale,” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis The Region , June 2005.

Answer to Try It! Problem

Discrimination leads to an inefficient allocation of resources and results in production levels that lie inside the production possibilities curve ( PPC ) (point A). If discrimination were eliminated, the economy could increase production to a point on the PPC , such as B.

Figure 19.14

Bok, D., and William G. Bowen, The Shape of the River: Long-Term Consequences of Considering Race in College and University Admissions (Princeton, N. J.: Princeton University Press, 1998).

Darity, W. A., and Patrick L. Mason, “Evidence on Discrimination in Employment,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 12:2 (Spring 1998): 63–90.

Donohue III, J. J., and James Heckman, “Continuous Versus Episodic Change: The Impact of Civil Rights Policy on the Economic Status of Blacks,” Journal of Economic Literature 29 (December 1991): 1603–43.

Heckman, J. J., “Detecting Discrimination,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 12:2 (Spring 1998): 101–16.

Principles of Economics Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

This website uses cookies to ensure the best user experience. Privacy & Cookies Notice Accept Cookies

Manage My Cookies

Manage Cookie Preferences

Confirm My Selections

- Monetary Policy

- Health Care

- Climate Change

- Artificial Intelligence

- All Chicago Booth Review Topics

How Discrimination Harms the Economy and Business

- By Kilian Huber

- July 15, 2020

- CBR - Economics

- Share This Page

Racism, xenophobia, and other forms of discrimination against minorities are, sadly, common phenomena—throughout history and in the current moment. In the United States, the Black Lives Matter movement and the protests that followed the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis highlight that many Americans consider discrimination a serious problem in the country today.

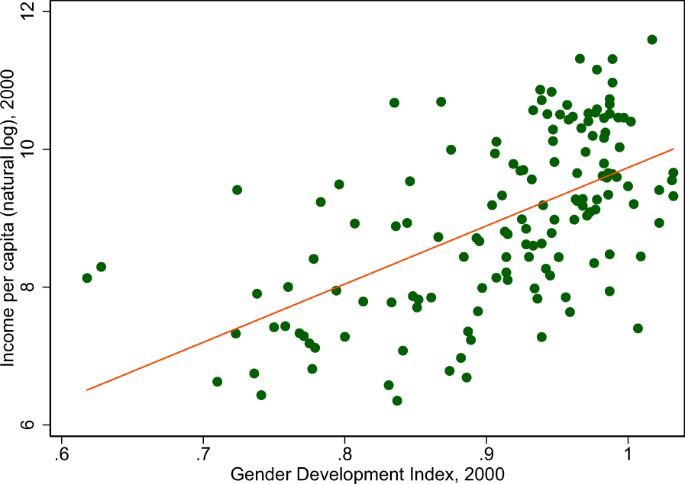

In recent research, my coresearchers— Volker Lindenthal and Fabian Waldinger , both at the University of Munich—and I consider how discrimination affects a country’s economy. Discrimination is extremely hurtful to individuals from targeted minorities. But, as we demonstrate, the effects of excluding talented individuals from economic opportunities tend to go further: when a society discriminates against a specific group, its entire economy can suffer.

The case we analyzed involves discrimination against Jews in Nazi Germany. We looked at the period after the Nazis gained power, on January 30, 1933, when discrimination against Jews quickly became commonplace in Germany. Many Jews were forced out of their jobs. By 1938, individuals with Jewish ancestry had effectively been excluded from the German economy.

The key idea in our study is that whenever discrimination interferes with the optimal allocation of talent, the economy suffers. This idea has its origins in formative work from the 1950s by the late University of Chicago economist and Nobel laureate Gary S. Becker, who argued that employers who are biased against hiring minorities harm themselves by missing out on talented individuals. We developed a technique to estimate how large and persistent the effects of such a loss of talent can be. And in our example, we find those effects are sizeable and long-lasting.

In 1932, Jews held about 15 percent of senior management positions in German companies listed on the Berlin Stock Exchange. When these top managers were kicked out, the companies were unable to replace them adequately. New senior management teams at affected companies were less connected to other companies, less educated, and had less managerial experience. The stock prices and profitability of the affected companies declined sharply after 1933, relative to unaffected companies. These effects were distinct from other shocks hitting German companies after 1933, for example, policies by the Nazi government or changes in demand for companies’ products.

When intolerance prevents individuals from exercising their talents, there tend to be widespread, long-lasting negative economic effects.

The aggregate effects of losing Jewish managers were large: an approximate calculation suggests that the market valuation of companies listed in Berlin fell by almost 2 percent of German gross national product. And besides being drastic, the effects were persistent: the performance of affected companies did not recover for at least 10 years, the end of our sample period. This suggests that the rise of a discriminatory ideology can lead to first-order and persistent economic losses.

Our case study involved dismissals of highly qualified senior managers who ran large, listed German companies. Hence, the discrimination we focused on was targeted at individual business leaders who were at the top of the economic pyramid. This pattern of forcing highly qualified individuals to give up important positions in the economy is all too common in history, bringing to mind the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II or the expulsion of managers who follow the cleric Fethullah Gülen from Turkish corporations in 2016.

Recommended Reading Why Intolerance Is Bad for Business

Strasbourg, France, is a picturesque city on the Rhine river—with a dark stain on its history.

There are important differences between the 1930s example of antisemitism in action and what many Black Americans face today. A history of slavery and racism has made it more difficult for Black Americans to reach leadership positions. But just as in Nazi Germany, these factors have an economic cost. For example, barriers such as limited access to education may have prevented an optimal allocation of talent. Some of my colleagues find that as such barriers fall, average earnings rise. (For more, read our Winter 2018/19 article “ How Women and Minorities Have Driven Wage Growth .”)

Recommended Reading A 150-Year-Old Bank Failure May Still Be Haunting Black Communities

The failure of the Freedman’s Bank may have had long-lasting repercussions for attitudes toward banking.

- CBR - Finance

The precise dynamics of how discrimination affects an economy are different depending on the form discrimination takes. However, there appears to be a similarity in the economic outcomes. When intolerance prevents individuals from exercising their talents, there tend to be widespread, long-lasting negative economic effects. The effects we documented lasted a decade, at least, and that was from a single example of a discriminatory purge. When it comes to centuries of race-based discrimination, our findings may suggest that companies and the economy are paying a high price.

Kilian Huber is assistant professor of economics at Chicago Booth.

Works Cited

- Gary S. Becker, The Economics of Discrimination , Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1957.

- Chang-Tai Hsieh, Erik Hurst, Charles I. Jones, and Peter J. Klenow, “ The Allocation of Talent and US Economic Growth ,” Econometrica, September 2019.

- Kilian Huber, Volker Lindenthal, and Fabian Waldinger, “ Discrimination, Managers, and Firm Performance: Evidence from ‘Aryanizations’ in Nazi Germany ,” CEPR discussion paper, January 2019.

More from Chicago Booth Review

How will a.i. change the labor market.

Economists consider how the technology will affect job prospects, higher education, and inequality.

- CBR - Clark Center Panels

Capitalisn’t: Rebooting American Health Care

Economist Amy Finkelstein offers her solutions for the problems plaguing the US healthcare system.

- CBR - Capitalisnt

What Are the Limits of Capitalism?

What can capitalism do for society, what can’t it do, and what should it do?

- CBR Podcast

Related Topics

More from chicago booth.

Your Privacy We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice , which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.

This website uses cookies.

By clicking the "Accept" button or continuing to browse our site, you agree to first-party and session-only cookies being stored on your device to enhance site navigation and analyze site performance and traffic. For more information on our use of cookies, please see our Privacy Policy .

- Journal of Economic Perspectives

- Spring 2020

Race Discrimination: An Economic Perspective

- Ariella Kahn-Lang Spitzer

- Article Information

- Comments ( 0 )

Additional Materials

- Author Disclosure Statement(s) (362.50 KB)

JEL Classification

- K42 Illegal Behavior and the Enforcement of Law

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6 The Economics of Discrimination

Caroline Krafft

What is discrimination?

Discrimination is the unjust or unequal treatment of an individual or group based on a specific characteristic, such as their race, age, or gender identity. In the United States, a number of laws forbid discrimination on the basis of age, disability, national origin, pregnancy, race/color, religion, or sex. [1] Globally, the United Nations (UN) has passed conventions on eliminating all forms of racial discrimination and discrimination against women. [2]

Although the definition seems straightforward, identifying when an individual or entity is discriminating in practice is quite challenging. This difficulty is because disparities (differences in outcomes) may be the result of current or past discrimination. The fact that women earn 83 cents for every dollar men earn [3] may reflect employers’ discrimination in setting wages, but may also reflect the fact that women choose different majors, or are more likely to take time out of the workforce to care for children. Of course, that women choose different majors may also reflect discrimination in human capital accumulation.

Likewise, the fact that Black men have a one in three lifetime likelihood of imprisonment, while white men have a one in seventeen chance [4] may be due to a variety of factors, such as historical housing discrimination and poor local labor market opportunities, as well as discrimination in the criminal justice system. Identifying the source of disparities—for instance in the case of imprisonment, whether disparities are due to unequal and discriminatory outcomes around education, employment, or poverty as factors in committing crimes, or in unequal chances of arrests, convictions, or sentences—is critical to addressing and reducing these disparities.

Causes of discrimination

Discriminatory “tastes”.

Economists have two main theories concerning the causes of discrimination. The first theory is that individuals have “tastes” or preferences for discrimination. [5] This taste-driven discrimination theory suggests that factors such as social and physical distance and relative socioeconomic status contribute to tastes for discrimination. Contact with a minority group and the size of a “minority” group matter as well (the minority in this case could actually be a majority that has historically been disempowered, e.g. women). Tastes for discrimination mean that individuals are effectively willing to forfeit income to avoid certain transactions or interactions. For instance, landlords may prefer to rent only to individuals of a certain race or religion, even though they could charge higher rents if they opened up to a broader market.

- Statistical discrimination

The second theory is statistical discriminatio n , which assumes discrimination is essentially an information problem. [6] For instance, in the labor market, employers may have imperfect information about the productivity of individual workers. Consider the case of an employer hiring a new carpenter for a construction company. The employer has information from applicants’ resumes on their education, training and past work experience. She can even administer a test to prospective employees to measure their skills, perhaps building a stair rail. The resume information and the test are, however, imperfect signals of the employee’s productivity. This uncertainty and imperfect information cause the employer to take into account another factor: she believes that women are, on average, less productive carpenters than men. This potentially erroneous statistic, combined with the inability of the resume and skills test to fully signal productivity, will lead the employer to conclude that a man is likely to be more productive than an equally qualified woman. The job is then offered to the man instead of the woman.

A “taste” for discrimination and statistical discrimination are often framed as competing theories. However, as we will see in discussing the empirical studies on discrimination below, there is substantial evidence for each theory. One way of reconciling the theories may be to think of taste-driven discrimination as a potential source of assumptions about individuals’ productivity in the face of incomplete information. Additionally, some individuals may change their assumptions in the face of additional evidence, a case which supports the existence of statistical discrimination. Others with more deeply ingrained prejudices would not reevaluate their assumptions, which lends credence to taste-driven discrimination. Different assumptions regarding individuals and groups may be more or less swayed by information.

Box 6. 1 : Economists in Action: Lisa Cook Studies Competition and Discrimination [7]

Dr. Lisa D. Cook is a Professor of Economics and International Relations, currently serving on the Board of Governors for the Federal Reserve. She researches economic growth and development, along with financial institutions, innovation, and economic history. She was a Senior Economist for the Council of Economic Advisors, serving in the White House, and was elected to the board of the American Economic Association (AEA). She directed the AEA Summer Training Program, which increases diversity in the field of economics by preparing undergraduate students for graduate degrees in economics.

One important area of Dr. Cook’s research is creating and analyzing data on discrimination, including gathering data on Jim Crow era firms that were friendly towards African Americans, as well as the creation of a national lynching database. In one of her papers Dr. Cook examines the determinants of firms’ discrimination towards potential consumers during the Jim Crow era and prior to the Civil Rights Act. She shows that firm owners segregated and discriminated against African Americans based on white consumers’ discrimination, a case of taste-based discrimination. Reductions in the number of white consumers reduced discrimination and activism among African Americans also helped.

Labor market models of discrimination and its consequences

Regardless of whether discrimination is taste-driven or caused by statistical discrimination, it can essentially be modeled the same way. The approaches to reducing discrimination will be quite different, but the models for the impact of discrimination will be nearly identical. Consider discrimination for the case of the labor market. Recall that employers’ demand for labor is based on productivity. We are now going to name that productivity the marginal revenue product of workers, how much revenue they create for their employers through their work. Operating under statistical discrimination, productivity is assumed to be lower for certain groups. [8] In the case of gender discrimination, employers may assume the marginal revenue product of women is lower because they disproportionately undertake caregiving responsibilities (a case of statistical discrimination). Alternatively, with taste-based discrimination, hiring a less-preferred group imposes a “cost” on employers, effectively modeled as a decrease in the marginal revenue product.

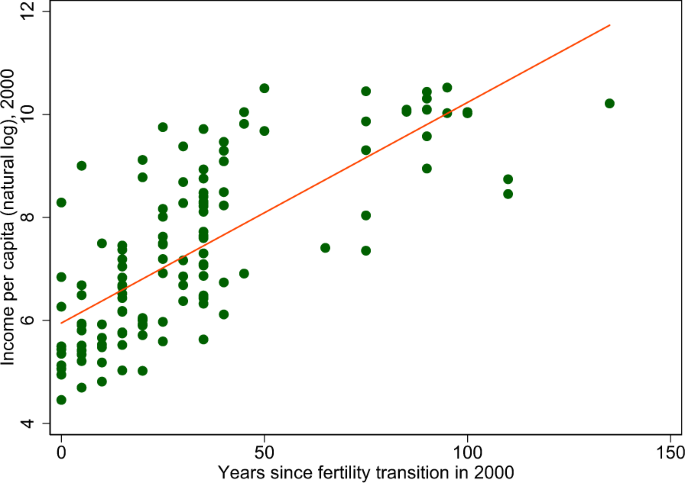

Figure 1 shows discrimination in the labor market for men and women. To simplify, we assume the same labor supply for men and women. However, the demand, which is equal to the marginal revenue product (MRP) is assumed to be lower for women than for men (discrimination). As a result, the equilibrium outcome is that fewer women are employed and women are earning lower wages than men. Although we focus on models of the labor market here, similar ideas apply to other markets. Housing is another example. A landlord might discriminate in supplying housing to individuals with a different religion than his own. This would shift the supply of housing to differentiate between religious groups, with a higher cost (reduced supply) for those of a different religion.

In all cases, there is a substantial challenge when it comes to proving discrimination. It is difficult to measure the MRP of different workers. This then makes it difficult to distinguish between cases where individuals actually are differentially productive on average, such as workers with more training or experience, and when discrimination is occurring.

Evidence on Discrimination

There are a variety of forms of discrimination and different groups that are discriminated against globally. This section presents just some of the evidence on discrimination, primarily from the U.S., but from other global contexts as well. Economists rely on a host of different techniques to gather evidence on discrimination. One is multiple regression , also called multivariate regression, a statistical technique where economists try to account for differences in observable characteristics. When checking for wage discrimination, for example, these characteristics would include occupation and education. The remainder of the differences in outcomes would then be attributed to discrimination.

Conducting experiments is another method to assess discrimination. Economists can randomize resumes with different characteristics to apply to jobs or randomize the economic equivalent of “mystery shoppers” with different characteristics to apply for housing. These experiments are typically referred to as audit studies . Experiments are the most effective for being certain about cause and effect, but can be challenging to implement and much more expensive than analyzing existing data with multiple regression. This section presents evidence from both multiple regression models and audit studies on discrimination in education, housing, the labor market, and the criminal justice system.

In education

Discrimination in the education system leads to disparate human capital outcomes that also contribute to labor market disparities. [9] Teachers play a key role in education and their discriminatory attitudes can affect students in a variety of ways. For instance, one experiment demonstrated that teachers gave worse grades and lower secondary school recommendations when assignments (essays) had minority (Turkish) names. [10] Teachers also have lower expectations and negative attitudes that affect their behavior towards minority students, which may in turn affect those students’ performance. [11] Gender bias may be particularly important for Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) fields. Science faculty presented with otherwise identical student resumes bearing either a female or male name rated women as less competent than men. Faculty were less likely to hire women, offered a lower salary, and were less likely to mentor women. [12]

Housing was one of the areas where discrimination in the United States was first measured effectively. Fair housing audits were developed by housing organizations to identify racial discrimination in housing opportunities after the passage of the Civil Rights Act. [13] For example, in assessing Black-white housing disparities, an audit will send two auditors to a housing agent, one white and one Black, for a random sample of advertised housing units. When individuals receive differential treatment, specifically in different offers of housing, and this treatment depends on their race, the audit indicates discrimination. Historically, as of 1981, Black housing seekers were told about 30% fewer available housing units than whites. [14]

More recent studies have taken advantage of the power of the internet; an experiment in the U.S. rental apartment market varied first names, using those commonly associated with whites and African Americans. In some cases, it also included information about credit history and smoking. African-American sounding names had a 9.3 percentage point lower positive response rate than applicants with white-sounding names, indicating discrimination. The additional information on credit history and smoking did differentially affect the gap in response rates, indicating that information and statistical discrimination contributed to disparities. [15] In India, a study using India’s largest real estate website showed that, while an upper-caste Hindu had a 35% chance of a response to a housing application, this was only 22% for a Muslim applicant. [16] An experiment in Sweden varied distinctive ethnic and gender names in applying for rental housing. Arabic/Muslim names received fewer responses than the Swedish male names, and Swedish female names had an easier time accessing housing than Swedish male names. [17] In addition to long-term rentals, these disparities extend to short-term rentals, such as Airbnb vacation rentals. Applications from guests with African-American names were 16% less likely to be accepted relative to otherwise identical guests with distinctively white names. [18] Discrimination also occurs against Airbnb ethnic minority hosts. [19]

In the labor market

Discrimination in the labor market manifests in substantial hiring disparities by race, ethnicity, gender, and disability status. A study sending fake resumes to help-wanted ads in Boston and Chicago found that white names received 50% more callbacks for interviews than African-American names. [20] A similar study in New York City found that Black applicants were half as likely to receive a callback or job offer than white applicants. [21] In interviews for waitstaff jobs in Philadelphia, job applications from women had a 40 percentage point lower chance of receiving a job offer from high-price (and high earning) restaurants than men, in part embodying customer discrimination. [22] An experiment that randomized disclosure of disability status found disability halved the chances of a callback. [23]

In Toronto, a study demonstrated that individuals with foreign experience or with Indian, Pakistani, Chinese, and Greek names were less likely to be hired than those with English names. [24] In Germany, which has a substantial number of Muslim migrants, especially from Turkey, it is common for applicants to send photos with resumes. A study of female applicants that randomized German names, Turkish names, and whether the migrant was wearing a headscarf found significant discrimination against Turkish names and more so against those wearing a headscarf. This discrimination is so pronounced that a female applicant who wears a headscarf and who has a Turkish name would have to send 4.5 times as many applications to receive the same number of callbacks as a woman with a German name and no headscarf. [25]

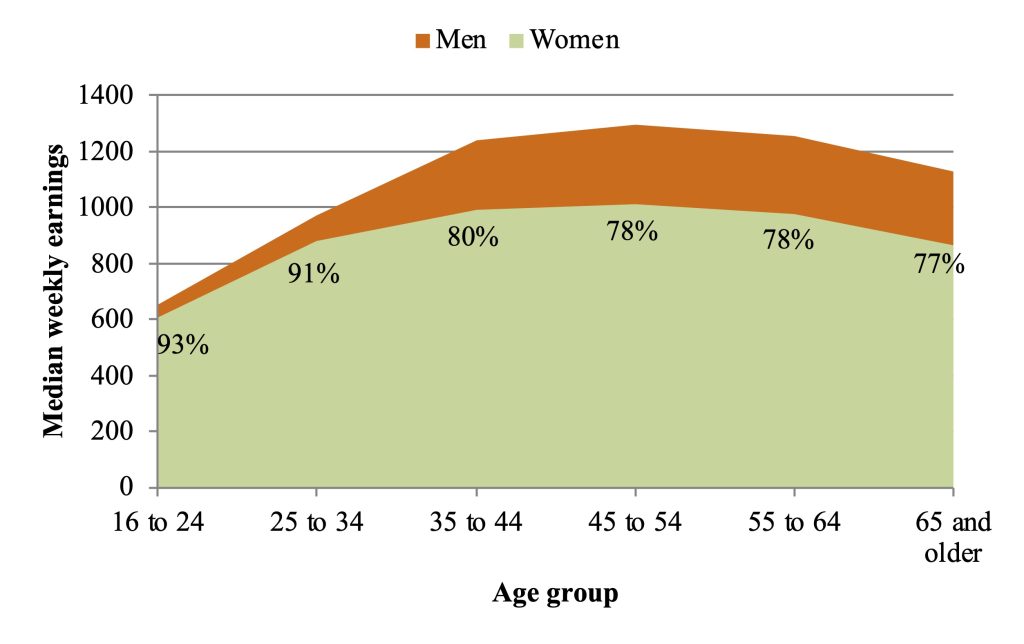

In the United States, women’s pay is, as of 2021, 83% of men’s pay. [26] Notably, women and men are approaching convergence in their pay at the start of their careers. Figure 6.2 [27] shows median weekly earnings by sex, as well as the ratio of women’s wages to men’s. Early on in the life course, women’s wages are 93% (ages 16-24) that of men’s. However, pay diverges over the lifespan, with a major expansion in the gender gap. At ages 25-34, women’s pay is 91% of men’s pay. By ages 35-44 women’s pay is only 80% of men’s, dropping to 78% at ages 45-64. Two key drivers for the gap expansion are differences in career interruptions and differences in weekly hours—both largely associated with motherhood. [28] In contrast, when men become parents, they tend to receive a premium, an increase in pay, rather than a penalty. [29] As of 2010, differences in human capital contributed little to the gender wage gap. However, differences in occupations were still important, as women tended to be in traditionally female occupations that are generally lower paying, such as nursing and teaching. [30]

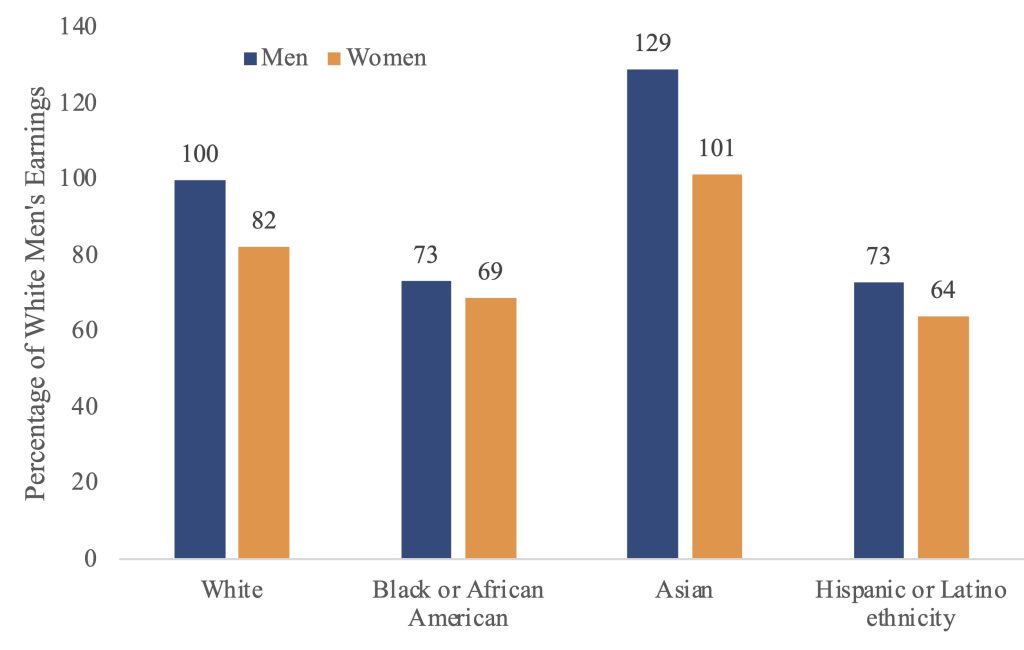

Gender pay gaps can be compounded by racial disparities. Figure 6.3 [31] shows median weekly earnings among workers as a percentage of white men’s earnings. People of color tend to earn less than whites, with disparities further exacerbated by the gender pay gap. For instance, Black and Hispanic men earn 73% of what white men earn. Asian men earn more than white men, at 129% and Asian women earn 101% of what white men earn. In contrast, other groups of women earn less on average. Black women earn 69% of what white men do and Hispanic women 64%. Relative to white women, who earn 83% of what white men earn, Asian women are better off but still at a disadvantage when compared to the relatively higher earnings of Asian men.

In studying pay gaps by race, what are referred to as pre-market factors, such as human capital, explain an important share of pay gaps. However, an important share of gaps are also discrimination in the labor market—estimated to be at least one-third of the Black-white wage gap. [32] Discrimination feeding into pay gaps can occur in complex ways. For example, when Black job-seekers attempt to negotiate for a higher salary, they are penalized in terms of their salary outcomes. [33] Likewise, women tend to be perceived more negatively than men when they try to negotiate, in part due to gender stereotypes around being “nice.” [34]

In the criminal justice system

Discrimination is a challenge throughout the criminal justice system and contributes to the large disparities in incarceration by race and gender that were discussed in the crime chapter. Racial disparities in drug arrests are not due to differential drug or nondrug offending, nor residing in areas with a police focus on drug offenses; there is strong evidence of discrimination and disparities in police practices driving disparities. [35] Likewise, studies using the differential ability to tell driver race in the daytime versus the nighttime have demonstrated racial bias in traffic stops in some localities, but not others. [36] Once arrested, individuals may be discriminated against in terms of the process from pre-trial processing (for instance, setting bail) through setting their sentences. [37] Offenders who are Black, male, less educated, and lower income receive longer sentences. [38]

Policies to reduce discrimination

Competition.

The idea of taste-based discrimination has, historically, been linked with the idea that competition may play a key role in reducing discrimination. Consider a case where all workers are equally productive, but some employers have discriminatory tastes. It would follow that the non-discriminating employers would be able to make a greater profit by hiring individuals who tend to be discriminated against but are equally productive. This idea would suggest that the solution to discrimination in any market is simply competition. However, empirical evidence suggests that, while competitive markets deter discrimination, firms that have market power exist and do discriminate. [39] Simply “waiting out” discrimination will not be effective. Other interventions are required.

Changing the available information

An important set of interventions to reduce discrimination focus on changing the available information about individuals. Interventions can remove markers of protected categories, such as gender and race, from the set of available information to reduce discrimination. For example, when symphony orchestras adopted blind auditions—where the candidate plays music behind a screen and is not visible to the hiring committee—this approach led to gender equity in hiring, increasing the proportion of women in symphony orchestras. [40] However, policies to remove all potentially revealing information are challenging to design, and employers may be resistant to their implementation. For instance, orchestras have to lay down carpet, to muffle the sounds of heeled shoes that are associated with women, or ask women to take off their shoes.

Removing names from the available information may reduce discrimination in a variety of areas. This approach can be particularly effective for reducing discrimination in models like Uber and Lyft [41] or Airbnb [42] where such information could be readily removed without interrupting transactions. Other approaches to removing potential markers of protected categories include anonymizing resumes and using skills-based tests (like the orchestra auditions) for other jobs as well. A number of European countries have experimented with anonymizing applications. [43] Doing so can reduce disparities and equalize the probability of receiving an interview. However, the process still allows for discrimination in hiring after the interview and precludes affirmative actions for otherwise equivalent applicants. In France, anonymous resumes ultimately led to a lower probability of interviewing and hiring minority candidates. [44]

Depending on the nature of discrimination, there may be cases where removing information could be potentially harmful and adding information may be more helpful. One of the studies that identified discrimination in Airbnb determined that discrimination against African-American names disappeared when there was a positive public review. [45] Essentially, positive information about individuals helped reduce discrimination. Having to report gender-disaggregated information about pay has been shown to reduce the gender pay gap. [46] However, having individuals disclose their past salaries when applying to new jobs can perpetuate discrimination, as new employers will use those as a basis for salary offers. This problem has led some states to ban asking applicants about their salary history. [47]

Box 6. 2 : The Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act [48]

Lilly Ledbetter was an employee of Goodyear from 1979 until 1998. Initially Ledbetter was paid the same as the men in the same position. By 1997, Ledbetter was paid $3,727 per month. Male managers were paid between $4,286 and $5,236 per month. In part because Goodyear kept pay information confidential (as is common practice), Ledbetter did not find out about the pay disparity until long after the disparity had occurred. When she sued, under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, a 5-4 decision in the case before the Supreme Court determined that she had not filed within the statute of limitations—the legal time frame for filing after discrimination occurs. The case treated the discrimination as the decision about her salary by her supervisor, some time ago, not the ongoing disparate paychecks, because the paychecks themselves did not have discriminatory intent, which is required under Title VII. The problem that faced Lilly Ledbetter, that she learned about discrimination long after it occurred and the statute of limitations expired, led to the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act. The Act, passed in 2009, broadened the definition of discriminatory practice to include, for instance, each disparate paycheck. The case and subsequent act illustrate some of the challenges in identifying and remedying discriminatory practices.

The “Ban the box” campaign is an example of an information removal effort that appears to have achieved the opposite of its goal. We learned in the chapter on crime that ex-offender rehabilitation depends in part on employment opportunities and holding a legitimate job. Yet employers tend to discriminate against those with a criminal record. [49] Employers commonly ask about past criminal convictions on initial job applications. “Ban the box” campaigns forbid asking at the initial job application stage but allow for the question in interviews and with conditional job offers. The goal was that ex-offenders would have better job opportunities. An additional goal was to reduce racial disparities and discrimination in employment, given racial disparities in the criminal justice system. [50] Although well intentioned, “ban the box” laws appear to be counterproductive in reducing discrimination. Employers, without information on criminal history, operate under statistical discrimination and are less likely to interview young, low-skilled Black and Hispanic men. [51]

- Affirmative action

Affirmative action is a “set of procedures designed to eliminate unlawful discrimination between applicants, remedy the results of such prior discrimination, and prevent such discrimination in the future. Applicants may be seeking admission to an educational program or looking for professional employment.” [52] Affirmative action in the United States came about as a 1961 executive order by President John F. Kennedy, with a requirement mandating affirmative action among government contractors. Affirmative action subsequently expanded to other areas, such as education.

Those in favor of affirmative action argue that it equalizes opportunities, benefits qualified women and minorities, and that it is beneficial to society as a whole. Proponents also suggest that affirmative action improves equity and either improves efficiency or has at most minor reductions in efficiency through the reallocation of jobs. Opponents suggest that there are efficiency losses and that the policy itself is inherently racist. [53]

Historically, affirmative action has helped promote the employment of minorities and women. [54] The magnitude of the effects is generally fairly small, although they can cause substantial relative shifts for minority groups. [55] While minorities who benefit on the labor market may have poorer credentials, they have equal performance, suggesting that efficiency concerns have relatively little merit. Further, white males face costs, but they are relatively small. Affirmative action has also increased the probability that under-represented minority groups graduate from selective institutions. However, affirmative action or some approaches to affirmative action have been banned in making university admissions decisions. [56]

Reducing bias in individuals

Individuals’ biases, for example their gender biases, are key drivers of discrimination. [57] Legal changes can potentially change individuals’ attitudes and behavior. For example, the passage of same-sex marriage reforms in U.S. states reduced individuals’ discrimination against sexual minorities. This reduced discrimination in turn contributed to improvements in labor market outcomes for same-sex couples. [58]

Individuals may not be aware of their biases, in which case they are referred to as implicit biases . Training can also reduce implicit biases, particularly those that may be caused by lack of exposure or familiarity with other races. [59] Treating implicit bias like a habit that can be combated through awareness, concern about its effects, and the use of strategies to reduce bias is helpful, particularly for people who are concerned about discrimination in the first place. [60] This suggests that training to reduce bias in individuals requires some commitment on their part to change their thinking and behaviors, and therefore is likely to work better for some individuals and biases than others.

Professionalizing human resources functions may also help reduce bias in the hiring process. Research in Canada demonstrated that employers discriminated against those with Asian-sounding names. Asian applicants had a 20% disadvantage for large employers but double the disadvantage, 40%, for small employers. Larger organizations may devote more resources to recruitment, have professional human resource strategies, and also have more experience with diverse staff. [61] This professionalism may reduce (although not necessarily eliminate) discrimination.

It may even be possible to reduce the role of biased human decision making in areas such as sentencing. Risk assessments are a potential, but controversial, approach to reducing bias in sentencing, parole, and rehabilitation. [62] Risk assessment instruments model the probability of reoffending based on a number of factors, including criminal history. In part because of different criminal histories, the policy can have disparate impact across racial groups. For example, Black offenders receive higher risk assessments, on average, than white offenders. [63] Especially with disparities in the criminal justice system, such instruments may perpetuate disparities. However, improvements in computing, such as machine learning algorithms, have the potential to reduce jail populations and crime rates, including reducing the percentage of minorities in jail. [64] Yet machine learning and artificial intelligence can also pick up and replicate existing biases. [65]

Conclusions

Discrimination occurs in education, employment, housing, and the criminal justice system, as well as many other dimensions of individuals’ lives. Economists tend to understand discrimination through one of two models—based on prejudicial “tastes” for discrimination or based on incomplete information leading to statistical discrimination. Both theories of discrimination show how discrimination contributes to disparate outcomes, such as different wages and employment rates for men and women. Although discrimination is pervasive, the good news is that progress is being made, and (some) disparities have decreased over time as a result of effective policies. Designing effective policies is, however, extremely challenging, as the efforts to “ban the box” illustrate. The challenges of designing effective policies underline an important role for economists and statisticians in the fight against discrimination: carefully evaluating the impact of different policy and program attempts to reduce discrimination.

List of terms

- Discrimination

- Disparities

- Taste-driven discrimination

- Marginal revenue product

- Multiple regression

- Audit studies

- Implicit biases

Abbott Watkins, Torie. “The Ghost of Salary Past: Why Salary History Inquiries Perpetuate the Gender Pay Gap and Should Be Ousted as a Factor Other Than Sex.” Minnesota Law Review 69, no. 1041–1088 (2018).

Agan, Amanda, and Sonja Starr. “Ban the Box, Criminal Records, and Racial Discrimination: A Field Experiment.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 133, no. 1 (2018): 191–235. doi:10.1093/qje/qjx028.Advance.

Ahmed, Ali M., and Mats Hammarstedt. “Discrimination in the Rental Housing Market: A Field Experiment on the Internet.” Journal of Urban Economics 64, no. 2 (2008): 362–72. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2008.02.004.

Antonovics, Kate, and Brian G. Knight. “A New Look at Racial Profiling: Evidence from the Boston Police Department.” Review of Economics and Statistics 91, no. 1 (2009): 163–77. doi:10.1162/rest.91.1.163.

Bailey, Martha J., Tanya S. Byker, Elena Patel, and Shanthi Ramnath. “The Long-Term Effects of California’s 2004 Paid Family Leave Act on Women’s Careers: Evidence from U.S. Tax Data.” NBER Working Paper Series . Cambridge, MA, 2019.

Banerjee, Rupa, Jeffrey G. Reitz, and Philip Oreopoulos. “Do Large Employers Treat Racial Minorities More Fairly? A New Analysis of Canadian Field Experiment Data.” University of Toronto Robert F. Harney Program in Ethnic, Immigration, and Pluralism Studies, 2017.

Becker, Gary S. The Economics of Discrimination . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1971.

Behaghel, Luc, Bruno Crépon, and Thomas Le Barbanchon. “Unintended Effects of Anonymous Résumés.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7, no. 3 (2015): 1–27. doi:10.1257/app.20140185.

Bellemare, Charles, Marion Gousse, Guy Lacroix, and Steeve Marchand. “Physical Disability and Labor Market Discrimination: Evidence from a Field Experiment.” HCEO Working Paper Series , 2018.

Bennedsen, Morten, Elena Simintzi, Margarita Tsoutsoura, and Daniel Wolfenzon. “Do Firms Respond to Gender Pay Gap Transparency?” NBER Working Paper Series . Cambridge, MA, 2018.

Bertrand, Marianne, Claudia Goldin, and Lawrence F. Katz. “Dynamics of the Gender Gap for Young Professionals in the Financial and Corporate Sectors.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2, no. 3 (2010): 228–55.

Bertrand, Marianne, and Sendhil Mullainathan. “Are Emily and Greg More Employable Than Lakisha and Jamal? A Field Experiment on Labor Market Discrimination.” American Economic Review 94, no. 4 (2004): 991–1013. doi:10.1257/0002828042002561.

Bielen, Samantha, Wim Marneffe, and Naci H. Mocan. “Racial Bias and In-Group Bias in Judicial Decisions: Evidence from Virtual Reality Courtrooms.” NBER Working Paper Series . Cambridge, MA, 2018.

Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn. “The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series , 2016. doi:10.1007/s10273-011-1262-2.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve. “Board Members: Lisa D. Cook,” 2022. https://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/bios/board/cook.htm.

Bonczar, Thomas P. “Prevalence of Imprisonment in the U.S. Population, 1974-2001.” Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report , 2003.

Bowles, Hannah R., Linda Babcock, and Lei Lai. “Social Incentives for Gender Differences in the Propensity to Initiate Negotiations: Sometimes It Does Hurt to Ask.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 103 (2007): 84–103. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.09.001.

Caliskan, Aylin, Joanna J. Bryson, and Arvind Narayanan. “Semantics Derived Automatically from Language Corpora Contain Human-like Biases.” Science 356 (2017): 183–86.

Carruthers, Celeste K., and Marianne H. Wanamaker. “Separate and Unequal in the Labor Market: Human Capital and the Jim Crow Wage Gap.” Journal of Labor Economics 35, no. 3 (2017): 655–96.

Cook, Lisa D. “Biographical Information for Lisa D. Cook, Ph.D.” Lisadcook.Net , 2019. https://lisadcook.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/cook_web_bio_revised_1219_rev-1.pdf.

———. “Converging to a National Lynching Database: Recent Developments.” Michigan State University , 2011.

Cook, Lisa D., Maggie E. C. Jones, David Rose, and Trevon D. Logan. “The Green Books and the Geography of Segregation in Public Accomodations.” NBER Working Paper Series . Cambridge, MA, 2020.

Cornell University Law School. “Affirmative Action.” Wex Legal Dictionary , 2017. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/affirmative_action.

Cui, Ruomeng, Jun Li, and Dennis J. Zhang. “Discrimination with Incomplete Information in the Sharing Economy: Field Evidence from Airbnb,” 2016.

Datta, Saugato, and Vikram Pathania. “For Whom Does the Phone (Not) Ring? Discrimination in the Rental Housing Market in India.” WIDER Working Paper , 2016.

Desmarais, Sarah L., and Jay P. Singh. “Risk Assessment Instruments Validated and Implemented in Correctional Settings in the United States,” 2013.

Devine, Patricia G., Patrick S. Forscher, Anthony J. Austin, and William T. L. Cox. “Long-Term Reduction in Implicit Race Bias: A Prejudice Habit-Breaking Intervention.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 48, no. 6 (2012): 1267–78. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2012.06.003.

Doleac, Jennifer L., and Benjamin Hansen. “Does ‘Ban the Box’ Help or Hurt Low-Skilled Workers? Statistical Discrimination and Employment Outcomes When Criminal Histories Are Hidden.” NBER Working Paper Series . Cambridge, MA, 2016.

Edelman, Benjamin, Michael Luca, and Svirsky Dan. “Racial Discrimination in the Sharing Economy: Evidence from a Field Experiment.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 9, no. 2 (2017): 1–22. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2701902.

Ewens, Michael, Bryan Tomlin, and Liang Choon Wang. “Statistical Discrimination or Prejudice? A Large Sample Field Experiment.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 96, no. 1 (2014): 119–34. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1816702.

Ewijk, Reyn Van. “Same Work, Lower Grade? Student Ethnicity and Teachers’ Subjective Assessments.” Economics of Education Review 30, no. 5 (2011): 1045–58. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.05.008.

Fryer Jr., Roland G., Devah Pager, and Jörg L. Spenkuch. “Racial Disparities in Job Finding and Offered Wages.” Journal of Law & Economics 56, no. 3 (2013): 633–89. doi:10.1086/673323.

Ge, Yanbo, Christopher R. Knittel, Don Mackenzie, and Stephen Zoepf. “Racial and Gender Discrimination in Transportation Network Companies.” NBER Working Paper Series , 2016. http://www.nber.org/papers/w22776.

Goldin, Claudia, and Cecilia Rouse. “Orchestrating Impartiality:The Impact of ‘Blind’ Auditions on Female Musicians.” The American Economic Review 90, no. 4 (2000): 715–41. doi:10.1257/aer.90.4.715.

Hellerstein, Judith K., David Neumark, and Kenneth R. Troske. “Market Forces and Sex Discrimination.” Journal of Human Resources 37, no. 2 (2002): 353–80. doi:10.3386/w6321.

Henry, Jessica S., and James B. Jacobs. “Ban the Box to Promote Ex-Offender Employment.” Criminology and Public Policy 6, no. 4 (2007): 755–62. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9133.2007.00470.x.

Hernandez, Morela, Derek R. Avery, Sabrina D. Volpone, and Cheryl R. Kaiser. “Bargaining While Black: The Role of Race in Salary Negotiations.” Journal of Applied Psychology 104, no. 4 (2019): 581–92.

Hinrichs, Peter. “The Effects of the National School Lunch Program on Education and Health.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 29, no. 3 (2010): 479–505. doi:10.1002/pam.20506.

Holzer, Harry J., and David Neumark. “Affirmative Action: What Do We Know?” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 25, no. 2 (2006): 463–90.

Ibanez, Marcela, and Gerhard Riener. “Sorting through Affirmative Action: Three Field Experiments in Colombia.” Journal of Labor Economics 36, no. 2 (2018): 437–78.

Kleinberg, Jon, Himabindu Lakkaraju, Jure Leskovec, Jens Ludwig, and Sendhil Mullainathan. “Human Decisions and Machine Predictions.” NBER Working Paper , 2017. doi:10.3386/w23180.

Krause, Annabelle, Ulf Rinne, and Klaus F. Zimmermann. “Anonymous Job Applications in Europe.” IZA Journal of European Labor Studies 1, no. 5 (2012).

Laouénan, Morgane, and Roland Rathelot. “Can Information Reduce Ethnic Discrimination? Evidence from Airbnb.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 14, no. 1 (2022): 107–32.

Lebrecht, Sophie, Lara J. Pierce, Michael J. Tarr, and James W. Tanaka. “Perceptual Other-Race Training Reduces Implicit Racial Bias.” PLoS ONE 4, no. 1 (2009). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004215.

Leonard, Jonathan S. “The Impact of Affirmative Action Regulation and Equal Employment Law on Black Employment.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 4, no. 4 (1990): 47–63.

Lundberg, Shelly, and Elaina Rose. “The Effects of Sons and Daughters on Men’s Labor Supply and Wages.” The Review of Economcis and Statistics 84, no. 2 (2002): 251–68.

Mitchell, Ojmarrh, and Michael S. Caudy. “Examining Racial Disparities in Drug Arrests.” Justice Quarterly 32, no. 2 (2015): 288–313. doi:10.1080/07418825.2012.761721.

Moss-Racusin, Corinne A., John F. Dovidio, Victoria L. Brescoll, Mark J. Graham, and Jo Handelsman. “Science Faculty’s Subtle Gender Biases Favor Male Students.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109, no. 41 (October 9, 2012): 16474–79. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211286109.

Mustard, David B. “Racial, Ethnic, and Gender Disparities in Sentencing: Evidence from the U.S. Federal Courts.” The Journal of Law & Economics 44, no. 1 (2001): 285–314.

Neumark, David, Roy J. Bank, and Kyle D. Van Nort. “Sex Discrimination in Restaurant Hiring: An Audit Study.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 111, no. 3 (1996): 915–41.

Oreopoulos, Philip. “Why Do Skilled Immigrants Struggle in the Labor Market? A Field Experiment with Thirteen Thousand Resumes.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 3, no. 4 (2011): 148–71. doi:10.1257/pol.3.4.148.

Pager, Devah. “The Mark of a Criminal Record.” American Journal of Sociology 108, no. 5 (2003): 937–75.

Pager, Devah, Bruce Western, and Bart Bonikowsi. “Discrimination in a Low-Wage Labor Market: A Field Experiment.” American Sociological Review 74, no. 5 (2009): 777–99. doi:10.1177/000312240907400505.Discrimination.

Phelps, Edmund S. “The Statistical Theory of Racism and Sexism.” American Economic Review 62, no. 4 (1972): 659–61.

Ritter, Joseph, and David Bael. “Detecting Racial Profiling in Minneapolis Traffic Stops: A New Approach.” CURA Reporter Summer/Spr (2009): 11–17.

Sansone, Dario. “Pink Work: Same-Sex Marriage, Employment and Discrimination.” Journal of Public Economics 180 (2019): 104086. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2019.104086.

Schlesinger, Traci. “Racial and Ethnic Disparity in Pretrial Criminal Processing.” Justice Quarterly 22, no. 2 (2007): 170–92.

Skeem, Jennifer, and Christopher T. Lowenkamp. “Risk, Race, & Recidivism: Predictive Bias and Disparate Impact.” Crimonology 54, no. 4 (2016): 680–712.

Sorock, Carolyn E. “Closing the Gap Legislatively: Consequences of the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act.” Chicago-Kent Law Review 85, no. 3 (2010): 1199–1216.

Sprietsma, Maresa. “Discrimination in Grading: Experimental Evidence from Primary School Teachers.” Empirical Economics 45, no. 1 (2013): 523–38. doi:10.1007/s00181-012-0609-x.

Starr, Sonja B., and M. Marit Rehavi. “Mandatory Sentencing and Racial Disparity: Assessing the Role of Prosecutors and the Effects of Booker.” Yale Law Journal 123, no. 1 (2013): 2–80. doi:10.1525/sp.2007.54.1.23.

US Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Highlights of Women’s Earnings in 2021.” BLS Reports Report 1102 , 2023.

U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “Discrimination by Type,” 2017. https://www.eeoc.gov/laws/types/.

UN Women. “Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women,” 2009. http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/text/econvention.htm.

United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. “International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination,” 2017. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CERD.aspx.

Weichselbaumer, Doris. “Multiple Discrimination against Female Immigrants Wearing Headscarves.” ILR Review , 2019, 1–28. doi:10.1177/0019793919875707.

Welty, Leah J., Anna J. Harrison, Karen M. Abram, Nichole D. Olson, David A. Aaby, Kathleen P. Mccoy, Jason J. Washburn, and Linda A. Teplin. “Health Disparities in Drug- and Alcohol-Use Disorders: A 12-Year Longitudinal Study of Youths After Detention.” American Journal of Public Health 106, no. 5 (2016): 872–80. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.303032.

Yinger, John. “Measuring Racial Discrimination with Fair Housing Audits: Caught in the Act.” American Economic Review 76, no. 5 (1986): 881–93.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2017. ↵

- UN Women, 2009; United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, 2017. ↵

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023. ↵

- Bonczar, 2003. ↵

- Becker, 1971. ↵

- Phelps, 1972. ↵

- Cook et al., 2020; Cook, 2011; Cook, 2019; Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, 2022. ↵

- Hellerstein, Neumark, and Troske, 2002. ↵

- Carruthers and Wanamaker, 2017. ↵

- Sprietsma, 2013. ↵

- Van Ewijk, 2011. ↵

- Moss-Racusin et al., October 9, 2012. ↵

- Yinger, 1986. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ewens, Tomlin, and Wang, 2014. ↵

- Datta and Pathania, 2016. ↵

- Ahmed and Hammarstedt, 2008. ↵

- Edelman, Luca, and Dan, 2017. ↵

- Laouénan and Rathelot, 2022. ↵

- Bertrand and Mullainathan, 2004. ↵

- Pager, Western, and Bonikowsi, 2009. ↵

- Neumark, Bank, and Van Nort, 1996. ↵

- Bellemare et al., 2018. ↵

- Oreopoulos, 2011. ↵

- Weichselbaumer, 2019. ↵

- Bertrand, Goldin, and Katz, 2010; Bailey et al., 2019. ↵

- Lundberg and Rose, 2002. ↵

- Blau and Kahn, 2016. ↵

- Fryer Jr., Pager, and Spenkuch, 2013. ↵

- Hernandez et al., 2019. ↵

- Bowles, Babcock, and Lai, 2007. ↵

- Mitchell and Caudy, 2015; Welty et al., 2016. ↵

- Ritter and Bael, 2009; Antonovics and Knight, 2009. ↵

- Schlesinger, 2007; Starr and Rehavi, 2013; Bielen, Marneffe, and Mocan, 2018. ↵

- Mustard, 2001; Cook et al., 2020. ↵

- Goldin and Rouse, 2000. ↵

- Ge et al., 2016. ↵

- Krause, Rinne, and Zimmermann, 2012; Behaghel, Crépon, and Le Barbanchon, 2015. ↵

- Behaghel, Crépon, and Le Barbanchon, 2015. ↵

- Cui, Li, and Zhang, 2016. ↵

- Bennedsen et al., 2018. ↵

- Abbott Watkins, 2018. ↵

- Sorock, 2010. ↵

- Pager, 2003. ↵

- Henry and Jacobs, 2007. ↵

- Doleac and Hansen, 2016; Agan and Starr, 2018. ↵

- Cornell University Law School, 2017. ↵

- Holzer and Neumark, 2006; Ibanez and Riener, 2018. ↵

- Leonard, 1990. ↵

- Holzer and Neumark, 2006. ↵

- Hinrichs, 2010. ↵

- E.g. Moss-Racusin et al., October 9, 2012. ↵

- Sansone, 2019. ↵

- Lebrecht et al., 2009. ↵

- Devine et al., 2012. ↵

- Banerjee, Reitz, and Oreopoulos, 2017. ↵

- Desmarais and Singh, 2013. ↵

- Skeem and Lowenkamp, 2016. ↵

- Kleinberg et al., 2017. ↵

- Caliskan, Bryson, and Narayanan, 2017. ↵

Economics for the Greater Good Copyright © 2019 by Caroline Krafft is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

How racial and regional inequality affect economic opportunity

Subscribe to the economic studies bulletin, jay shambaugh , jay shambaugh under secretary for international affairs - u.s. department of the treasury @jaycshambaugh ryan nunn , and ryan nunn assistant vice president for applied research in community development - federal reserve bank of minneapolis @ryandnunn stacy a. anderson stacy a. anderson communications manager - the hamilton project @saunique.

February 15, 2019

In a recent Hamilton Project paper, The Historical Role of Race and Policy for Regional Inequality , economists Bradley L. Hardy , Trevon D. Logan , and John Parman examine how the spatial distribution of the black population has evolved over time and how this has interacted with economic mobility and U.S. public policy. Their analysis emphasizes the importance of both place and policy in determining individual outcomes.

The Regional Concentration of the African American Population

Despite the Great Migration of millions of African-Americans from the rural South to cities across the United States, the modern distribution of black Americans closely relates to the historical patterns of the black population. Counties with disproportionately high shares of black Americans today are the same counties that had large black populations before the Civil War, suggesting that historical conditions have had extremely persistent impacts on the outcomes of African-Americans. Moreover, as illustrated in the figure below, poverty in the Deep South tend to be much higher in counties with high black populations.

Differences within regions—across cities, suburbs and rural areas—also affect racial inequality. The black population tends to be more concentrated in the central counties of large metropolitan areas relative to the white population. By contrast, the white population tends to live in smaller metropolitan areas and in rural counties.

This concentration of the African-American population is not accidental. As Hardy, Logan, and Parman detail, influences ranging from discrimination and intimidation, to lender behavior, to white flight from cities, to public policies like redlining or highway construction all combined to keep the African-American population more concentrated in particular communities.

Economic Mobility

Recent research by Raj Chetty and coauthors has illuminated the differing potential for intergenerational mobility that exists across the United States. Overlaying this pattern with the spatial distribution of the black population yields some disturbing results: areas with a large black population are likely to be places where black individuals experience particularly low levels of economic mobility. In the South, these low mobility rates for black individuals are substantially lower than corresponding rates for white individuals. Regions in the North and West, with small black populations, exhibit levels of mobility for black individuals that are both higher and comparable to those of white individuals, but these are regions with relatively small black populations. The regions where the bulk of black Americans live are the ones where their upward mobility is relatively low.

The Connection of Racial and Regional Inequality

The high concentration of the African-American population in particular areas has also meant that policies or practices that disadvantage the black community will wind up reinforcing particular patterns of regional or spatial inequality. While many of the most egregious policies designed to promote and encourage racial discrimination have been outlawed, research has shed light on the ways that their effects linger and interact with contemporary policies.

As Hardy, Logan, and Parman explain, there are a range of policies or practices that continue to disadvantage black individuals and communities throughout the U.S., impacting areas including:

- P ublic education , which has often been underfunded in African-American majority schools, limiting skill acquisition and upward mobility for black Americans.

- Employment discrimination , which makes it more difficult for black families to escape from poverty or build wealth in their community.

- The social s afety net system, where there is an increased likelihood of sanctioning and spending is less generous for black communities.

- T he criminal justice system , where poor outcomes for black Americans include higher bail and greater likelihood of monetary sanctions, among other penalties.

Given the history and the concentration of the black population throughout the U.S., regional inequality is often shaped by racial inequality, and taking steps to combat regional inequality will need to recognize this source. Accordingly, identifying mechanisms to not only address, but actually reverse, the ongoing effects of discriminatory policies and practices is not only a moral imperative: it is also a pressing economic concern.

Related Content

Bradley Hardy, Trevon D. Logan, John Parman

September 28, 2018

Jay Shambaugh, Ryan Nunn

Patrick Sharkey

December 5, 2013

Economic Studies

The Hamilton Project

April 4, 2024

April 3, 2024

Benjamin H. Harris, Liam Marshall

April 2, 2024

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Economic View

Racism Impoverishes the Whole Economy

While the targets unquestionably suffer the most, denying people equal opportunities diminishes the finances of millions of Americans.

By Lisa D. Cook

Discrimination hurts just about everyone, not only its direct victims.

New research shows that while the immediate targets of racism are unquestionably hurt the most, discrimination inflicts a staggering cost on the entire economy, reducing the wealth and income of millions of people, including many who do not customarily view themselves as victims.

The pernicious effects of discrimination on the wages and educational attainment of its direct targets are being freshly documented in inventive ways by scholarship. From the lost wages of African-Americans because of President Woodrow Wilson’s segregation of the Civil Service , to the losses suffered by Black and Hispanic students because of California’s ban on affirmative action , to the scarcity of Black girls in higher-level high school math courses , the scope of the toll continues to grow.

But farther-reaching effects of systemic racism may be less well understood. Economists are increasingly considering the cost of racially based misallocation of talent to everyone in the economy.

My own research demonstrates, for example, how hate-related violence can reduce the level and long-term growth of the U.S. economy. Using patents as a proxy for invention and innovation, I calculated how many were never issued because of the violence — riots, lynchings and Jim Crow laws — to which African Americans were subjected between 1870 and 1940.