- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

How The Pandemic Has Changed The Way We Communicate

NPR's Lulu Garcia-Navarro speaks with Amelia Aldao, a clinical psychologist in New York City, about how the pandemic has impacted the ways we communicate with one another.

LULU GARCIA-NAVARRO, HOST:

Here in the United States, some 1,700 people are still dying every day, and tens of thousands are getting infected. It's been almost a year since the pandemic changed every aspect of our lives and, in particular, the way we communicate. We asked some of you to tell us about how you've talked to the people in your life, what's worked for you over the last year and what hasn't.

JAY DANIELS: Before COVID-19, we would, you know, have our occasional phone calls where I called my parents, like, every Wednesday. And I talked to my sister every once in a while. But the pandemic has changed all that. So we've gone from infrequent communication to now every Friday night, we have a Zoom dinner where the three families can get together, and the grandkids can see each other, and we can talk and have dinner together. We don't ever miss it.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

JESSICA LINEHAM: On Thursday, March 20, 2020, my book club was scheduled to meet. Another member suggested we get together on Zoom, something we'd never done before. The rest is history. Since then, we've met up every single Thursday. We don't talk about a book every week, but we do spend a few hours chatting, commiserating and remembering what it's like to see our friends. And while I'm looking forward to getting vaccinated and seeing them in person, I have a feeling we'll keep up our more frequent Zooms, too.

KAREN FREEMAN: I've always really loved writing handwritten letters and receiving them in the mail. So at the beginning of the pandemic, when I was missing my colleagues and friends, I gathered a bunch of postcards and started writing one to someone every day at lunch, someone I was thinking of and missing. And it was a great opportunity to connect with them. I loved receiving notes back and texts and people telling me how much it meant that I was thinking of them.

CLAIRE O'KEEFE: I teach community college, and probably the biggest change that I've witnessed is how the technologies that we rely on for remote learning have this tendency to bring new student voices into the conversation. Traditional face-to-face classes have a way of rewarding one kind of student, the one who's good at speaking extemporaneously and who is comfortable raising their hand. But now I hear from everybody, whether it's via discussion boards or the chat feature. And all of those multiple entry points have this wonderful, magical way of just blowing the class wide open.

CHRIS WELLS: My friends and I always found it hard to get together. And then the pandemic struck last March, and we found ourselves home alone. One thing that we all have in common is that we are Trekkies, meaning we love "Star Trek." And so we got together one night on Zoom and decided to watch an episode of "Star Trek: The Next Generation" together through one of the watch party services. Believe it or not, we've been getting together almost every night since then.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: That was Jay Daniels (ph), Jessica Lineham (ph), Karen Freeman (ph), Claire O'Keefe (ph) and Chris Wells (ph). While technology has been great for some people - and shoutout there to those "Star Trek" fans - there's a lot we do lose through a screen - eye contact, body language, nonverbal cues. We spoke with Amelia Aldao - she's a therapist in New York - about the future of post-pandemic communication. I asked her if we found ways to compensate for what we've lost.

AMELIA ALDAO: To be honest, no. If you actually think about it - right? - we are not necessarily making eye contact. We're looking at the person on the screen, but we're not really looking at the camera. And if we are looking at the camera, we're not actually looking at the person. And that's actually very different, right? It's sort of changing the way in which we are looking into each other. So the eye contact is off.

And I've noticed myself, my clients and also some of my friends as well that then when we go see people in real life, we get a little awkward with the whole eye contact because we're sort of forgetting how to do it outside of the small circle of people that maybe live in our household or that we see regularly. So the eye contact is a big adjustment that we're all going to be facing in the next few months, to be honest.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: So I asked people on Twitter what their experience has been with communicating during COVID, and some people had some really wonderful responses. You know, people are now handwriting each other letters as a reaction against this kind of enforced virtual world that we find ourselves in. They're playing board games virtually. They're talking with family that lives far away more often than they would otherwise. So there is, you know, something positive that we can take away from all this. Do you think we will take away some of this virtual connection when we move forward - there'll be a sort of hybrid?

ALDAO: Yeah, I absolutely think so, and I hope so as well. It is convenient to use all these technologies to communicate, and that's useful. What we're missing by doing things that are efficient - this is usually in general, right? Whenever we optimize for efficiency, we tend to lose depth, and we tend to lose connection. So I think it's going to be finding a balance between using technology so that we can do certain things more efficiently, faster, better and then find time and space to connect with people differently, one-on-one, in the sort of messiness of the real world.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: What do you tell your clients about how they should go back into the world as this pandemic and its effects end?

ALDAO: So the first thing that I tell my clients and my friends and myself and everybody who's willing to listen, to be honest, is that this is not going to be a switch that we turn on and off. Basically, approach this as a quote-unquote "exposure exercise." You know, maybe you grab a coffee with a friend one week. And then maybe two weeks later, you decide to make that into a dinner with a friend or a dinner with a friend and another friend.

So that's what I tell people - be patient. It's going to take a long time. But at the same time, you have to take agency and put yourself out there. And it's going to be awkward. It's going to be difficult. It's going to be anxiety-provoking. But it's really the only path forward. So that's how we're going to get through all of this.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: Dr. Amelia Aldao is a therapist in New York City.

Thank you very much.

ALDAO: Yeah, thank you for having me.

Copyright © 2021 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Changes in Digital Communication During the COVID-19 Global Pandemic: Implications for Digital Inequality and Future Research

Affiliation.

- 1 University of Zurich, Switzerland.

- PMID: 34192039

- PMCID: PMC7481656

- DOI: 10.1177/2056305120948255

Governments and public health institutions across the globe have set social distancing and stay-at-home guidelines to battle the COVID-19 pandemic. With reduced opportunities to spend time together in person come new challenges to remain socially connected. This essay addresses how the pandemic has changed people's use of digital communication methods, and how inequalities in the use of these methods may arise. We draw on data collected from 1,374 American adults between 4 and 8 April 2020, about two weeks after lockdown measures were introduced in various parts of the United States. We first address whether people changed their digital media use to reach out to friends and family, looking into voice calls, video calls, text messaging, social media, and online games. Then, we show how age, gender, living alone, concerns about Internet access, and Internet skills relate to changes in social contact during the pandemic. We discuss how the use of digital media for social connection during a global public health crisis may be unequally distributed among citizens and may continue to shape inequalities even after the pandemic is over. Such insights are important considering the possible impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people's social wellbeing. We also discuss how changes in digital media use might outlast the pandemic, and what this means for future communication and media research.

Keywords: COVID-19; digital communication; digital inequality; social connection.

© The Author(s) 2020.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 23 May 2022

The impact of COVID-19 on digital communication patterns

- Evan DeFilippis ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9757-4374 1 ,

- Stephen Michael Impink ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5910-642X 2 ,

- Madison Singell 3 ,

- Jeffrey T. Polzer 1 &

- Raffaella Sadun 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 9 , Article number: 180 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

20k Accesses

16 Citations

20 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

We explore the impact of COVID-19 on employees’ digital communication patterns through an event study of lockdowns in 16 large metropolitan areas in North America, Europe, and the Middle East. Using de-identified, aggregated meeting and email meta-data from 3,143,270 users, we find, compared to pre-pandemic levels, increases in the number of meetings per person (+12.9 percent) and the number of attendees per meeting (+13.5 percent), but decreases in the average length of meetings (−20.1 percent). Collectively, the net effect is that people spent less time in meetings per day (−11.5 percent) in the post-lockdown period. We also find significant and durable increases in length of the average workday (+8.2 percent, or +48.5 min), along with short-term increases in email activity. These findings provide insight into how formal communication patterns have changed for a large sample of knowledge workers in major cities. We discuss these changes in light of the ongoing challenges faced by organizations and workers struggling to adapt and perform in the face of a global pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

The effects of remote work on collaboration among information workers

Longqi Yang, David Holtz, … Jaime Teevan

The online language of work-personal conflict

Gloria Liou, Juhi Mittal, … Sharath Chandra Guntuku

The effect of co-location on human communication networks

Daniel Carmody, Martina Mazzarello, … Carlo Ratti

Introduction

The COVID-19 global pandemic disrupted the way organizations function, just as it disrupted life more generally. As the number of infections increased, governments across the globe closed their borders and shut down physical work sites to reduce the spread of infection caused by the virus. By April 7, 2020, 95 percent of Americans were required to shelter-in-place within their homes, similar to the citizens of many other countries. Organizations responded by altering their work arrangements to accommodate these new realities, including a rapid shift to working from home for large segments of knowledge workers. Many workers were forced to work remotely to perform their jobs regardless of how conducive their home environment or task requirements were to such arrangements. Given the large-scale economic and social upheaval wrought by COVID-19, this abrupt transition to remote work occurred at a time when organizational coordination, decision-making processes, and productivity were never more consequential.

This paper provides a large-scale analysis of how formal digital communication patterns changed in the early stages of the pandemic. For all the anecdotes and speculation about working from home during the pandemic, there is still little systematic evidence on how day-to-day work activities changed due to these unexpected shocks. This paper explores, in particular, how the pandemic altered patterns of interactions—measured through a comprehensive set of meeting and email activity metrics—as organizations rapidly moved their activity to remote work. The analysis is based on de-identified meta-data from an information technology services provider that licenses digital communications solutions to organizations worldwide. We use digital meta-data on emails and meetings for 3,143,270 users across 21,478 de-identified firms located in 16 large metropolitan areas, aggregated by the provider to the Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) and day across all available firms (see Appendix, Figs. B1 and B2 ). The meta-data provides information on both email and meeting frequency, as well as other salient aspects of digital communications, such as meeting size, meeting duration, the number of email recipients, the time an email was sent, and related dimensions (see Appendix, Table A1 ).

The precise geographical and longitudinal information contained in the communication meta-data allows us to study the evolution of meeting and email activity before and throughout the first stage of the pandemic. To identify the time at which workers presumably shifted to remote work, we selected 16 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) that experienced government-mandated lockdowns. These lockdowns established a clear breakpoint, after which we could infer that people were working away from their offices. The earliest lockdown in our data occurred on March 8, 2020, in Milan, Italy, and the latest lockdown occurred on March 25, 2020, in Washington, DC (see Table 1 for more information). We report data from a window starting 8 weeks before the lockdown and ending 8 weeks after the lockdown in each MSA to explore how the behavior of workers changed.

Digital communication and remote work

Theorizing about how employees might have responded to the COVID-19 crisis is challenging for many reasons. First, research conducted before the pandemic examined transitions to remote work that were voluntary, less widespread, and performed under less dramatic circumstances (Bloom et al., 2013 ; Choudhury et al., 2019 ). These circumstances are fundamentally different from the situation that organizations found themselves in shortly after the start of the pandemic.

Second, the few examples of forced transitions to remote work which do exist occurred in the aftermath of acute disasters, such as the Christchurch earthquakes in New Zealand or the 2011 Tōhoku tsunami in Japan (e.g. Donnelly and Proctor-Thomson, 2015 ; Dye et al., 2014 ), rather than a persistent crisis more similar to the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, these transitions typically involved a smaller fraction of the workforce over a shorter duration, making it harder to generalize from them to the circumstances surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic.

Third, there is scarce prior evidence on digital communication across many firms, even in the absence of a crisis. For example, the nascent literature on the “science of meetings” tends to examine the behavior of a single or handful of firms, or use self-report measures derived from survey responses from a subset of firms or workers, instead of digitally-stored communications data at the scale examined in this paper (e.g. Rogelberg et al., 2006 , 2010 ; Allen et al., 2015 ). While there is a growing body of research examining how digital communications have changed since the pandemic (e.g. Cao et al., 2021 ; Yang et al., 2021 ), these studies tend to examine a single company, making it difficult to generalize results across different organizational features, such as size and industry.

Finally, existing research provides little guidance on how various dimensions of organizational communication activities relate to each other, even though they are likely to be interdependent. For example, meeting count—the number of meetings employees attend in a day—is likely to depend on other dimensions of meeting activity, such as meeting duration or size. Organizations may be reluctant to have meetings that are too long, involve many participants, and occur too frequently, as this may inhibit employees from accomplishing their individual work. Similarly, having infrequent, short, and small meetings may also be suboptimal, as it would limit opportunities for organization-wide coordination on broader tasks. The lack of research about how organizations navigate this balancing act makes it difficult to distill clear hypotheses about how the forced shift to remote work during the pandemic affected the different, interrelated dimensions of communication activity examined in this paper.

Because of the lack of existing theory and the novelty of these widespread, forced transitions to remote work, we do not generate a set of hypotheses. Instead, we summarize what we might infer from adjacent research on the individual variables considered in this paper.

Meeting frequency

The communication literature shows that digital communication is generally less information-dense than face-to-face interaction (Sproull and Kiesler, 1986 ; Daft and Lengel, 1986 ). Because virtual work must take place via “lean” informational channels, such as emails and videoconferences, certain social cues that are readily apprehended in-person can be lost when translated into digital mediums (Denstadli et al., 2012 ; Han et al., 2011 ). According to this reasoning, newly virtual teams adjusting to the pandemic should communicate more frequently via email and meet more often to compensate for the lack of rich social and contextual information previously conveyed through face-to-face interaction (Carletta et al., 2000 ; DeSanctis et al., 1993 ). We can arrive at a similar prediction by examining research on virtual teams, which finds that teams working remotely often suffer from a lack of formal accountability as managers cannot directly observe their employees’ performance (Kurland and Bailey, 1999 ). To compensate for this fact, managers on virtual teams may meet more frequently to ensure that employees accomplish organizational tasks (Maurer, 2020 ; White, 2014 ; Wiesenfeld et al., 1999 , 2001 ).

However, emerging research suggests that an unconditional increase in meeting frequency is unlikely, given that virtual meetings tend to be more cognitively demanding, more prone to distraction, and less effective in many ways than their in-person counterparts (Wiederhold, 2020 ). Adding to this problem are the unique challenges associated with technological adoption, including unanticipated service interruptions and the need for skilled meeting organizers who are fluent in the advanced features of meeting platforms and can resolve issues when they arise (Deakin and Wakefield, 2014 ; Seitz, 2016 ). These issues might offset the inclination to hold more meetings if managers acknowledge the diminishing returns to virtual meetings and modulate their frequency as teams transition remotely (Nardi and Whittaker, 2002 ; Wiederhold, 2020 ).

Meeting size

The literature is equally equivocal when it comes to the topic of meeting size. Research on collaboration, for example, observes that organizations often have different norms and conventions governing average meeting size, and that these norms are important predictors of meeting effectiveness, task performance, and inclusiveness in remote collaboration (Allen et al., 2020 ). But the literature is largely silent on whether these pre-existing organizational differences in meeting norms are likely to be preserved as firms transition remotely, or if organizations will be forced to adopt new norms as employees adjust to working from home. Convincing cases can be made for either prediction. For example, we might expect meetings to become larger as organizations shift to remote work since meeting organizers can be more inclusive about who gets invited to virtual meetings, since they do not have to worry about the physical capacity of meeting rooms. Managers may even see advantages to increasing the total number of people invited to meetings, as the problems that organizations face during this time will likely be relevant to a greater fraction of the workforce.

On the other hand, there are also good reasons to predict that meetings would become smaller as organizations get accustomed to remote work. Managers who use meetings primarily as an accountability tool to check-in with remote employees could increase the frequency of one-on-one meetings, which would drive the average size of meetings downward. Meeting organizers are also likely to consider workers’ attentional limitations, which are exacerbated in larger digital meetings where expectations regarding listening behaviors and interaction are less strict (Lyons and Kim, 2010 ). To mitigate these concerns, managers may opt for smaller meetings to minimize the risk of distraction.

Meeting length

Meeting length is another topic about which the literature is inconclusive. While there is a wealth of research discussing the challenges of long or inefficiently staggered meetings (e.g. Rogelberg et al., 2006 ; Stray et al., 2013 ), there is very little empirical research directly testing the dimension of meeting length, and few theoretical pieces that might inform predictions about what to expect as organizations transition remotely. As with other dimensions of meeting activity, plausible cases can be made for expecting either an increase or a decrease in the average length of meetings that employees attend. For example, employees are likely to have a hard time staying engaged in long virtual meetings (Wiederhold, 2020 ), which may force managers to respond by decreasing the length of meetings to reduce strain on employees’ attention. Similarly, as a greater proportion of meetings are used as a “check-in” tool to enforce employee accountability remotely, we might also expect a decrease in average meeting length, since check-in meetings can be completed in a shorter amount of time than other meeting types (Arnfalk and Kogg, 2003 ).

However, we might also expect the average meeting length to increase for a different set of reasons. For example, organizations may simply face more severe and frequent problems in the middle of a pandemic than they usually do. These problems may require longer meetings to adequately share information and ensure tasks are effectively coordinated across employees. Online meetings may also be less efficient than their in-person counterparts, owing to technical problems, communication challenges, and distractions at home. These inefficiencies may require meeting organizers to schedule relatively longer meetings to accommodate challenges inherent to digital media.

Email activity

The trade-offs entailed in these decisions not only affect meeting activity, but communication activity more broadly. After all, much of the information that is exchanged in meetings could be conveyed in written form via email or other text-based tools. For this reason, our paper also focuses on email activity, which continues to be a prominent channel of communication in many organizations. In the context of this paper, email is a particularly important communication stream because it can act as both a complement to and substitute for meeting activity. Many tasks, for example, can be more efficiently accomplished via email, given its asynchronous, text-based format and the potential for one-to-many communication (Larsen et al., 2008 ). Other tasks which may require significant coordination or a large amount of social context and nuance may be better suited for meetings. The degree to which organizations will rely on emails as a complement to or substitute for meeting activity as they transition remotely remains an open question.

To understand how organizations changed their digital communication patterns in response to the pandemic, we analyzed a large sample of aggregated meeting and email meta-data from 3,143,270 users across 21,478 firms in 16 international cities that have been affected by official lockdown orders, reported in Appendix, Figures B1 and B2 . From this meta-data, our data provider, which licenses digital communications services to organizations around the world, built measures of the communication frequency for email (the average count of distinct, internal, and external emails and the average count of recipients) and meetings (the average count of meetings, average meeting duration, and the average count of attendees per meeting). Additionally, we measured broader changes to work patterns, such as the average length of workday (measured from the first communication to the last communication in a given day), the cumulative number of hours people spent in meetings, and the average number of emails sent outside of regular business hours, reported in the Appendix, Table A1 . More details on our measures are reported in the Appendix, Note A6 .

Our data provider cleaned the data in several ways to increase the likelihood that calendar metadata reflected actual organizational activity. First, they dropped meetings with only one attendee or meetings that lasted longer than 8 h since those meetings overwhelmingly corresponded with out-of-office notices or people blocking out personal time on their calendar rather than formal meeting activity. Next, they excluded meetings with greater than 250 attendees to filter out company-wide notices and spam invitations. Lastly, they only provided internal emails based on correspondence between two employees who shared the same corporate domain address (e.g. @company.com).

The data provider matched meeting and email metadata to a list of metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs). For each MSA in our data, we included the central business district of the cities and surrounding suburbs and townships within the MSA with populations greater than 100,000 people. The 16 major cities included in the sample were selected based on the following criteria: (1) each city must average at least 50,000 active users across 500 firms in the time period examined; (2) each city must have implemented a clear, government-mandated order for non-essential employees to work from home; and (3) these orders had to take effect around the same time (between March 8 and 28) to more explicitly control for time-specific factors related to the organizational response to COVID-19. The third criteria resulted in the exclusion of Asian cities from the analysis since their lockdowns took place at least a month before other major international cities. Each variable used in this analysis was computed by our provider and delivered to us pre-aggregated at the MSA-level. At no point did the research team have access to personally identifiable or user-level data.

In a secondary data set, our provider calculated and shared email communication aggregates at the industry (SIC-1) and organization size level (i.e., small <250 users, medium 250–500 users, large 1000–2500 users, and enterprise 2500+ users) for each of the 16 MSAs included in this study. Our email provider was unable to provide the industry-level data for meeting measures. We use this dataset only to show that our results are consistent across industry and size levels in various robustness tests.

For the main set of results, we used average meeting and email activity aggregated at the MSA level in the post-lockdown period relative to the pre-lockdown period. We used the following specification for our first set of results, which uses a single dummy variable to test the overall difference between pre- and post-lockdown periods for each outcome variable.

To analyze the change in email and meeting measures over different weeks, we used the following specification:

where y i , t are logged email and meeting data at the MSA i and day t level, post is an indicator variable for the period after lockdown, Dτ t is a week indicator variable, relative to the lockdown week, γ i are MSA-level fixed effects, d t are day of the week indicator variables (Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, etc.), and u i,t is an error-term. Note that MSA-level fixed effects were selected since that was the level at which our communication data was aggregated by our data provider. MSA-level fixed effects control for average differences across MSAs for the outcome of interest, enabling us to report within-MSA changes.

The “lockdown week” is the 7-day period that includes the lockdown date at its center. Every prior and subsequent week indicator is defined relative to that week. The base week for our regression is defined as one week before the lockdown week since many organizations began making arrangements days in advance of official lockdowns based on news of impending policy changes. Email and meeting measures do not display evidence of a pre-trend in the weeks leading up to the base week and lockdown week. All standard errors are clustered at the MSA level (see Tables 2a , b for details).

We use an OLS regression-based event study to examine how these measures vary before and after government-mandated lockdowns. Our method is similar to other approaches in the literature used to evaluate event-related changes in an outcome of interest (e.g. Henderson, 1990 ; Kothari and Warner, 2007 ). We group digital communication measures into three categories of interest: meeting, email, and work–life balance.

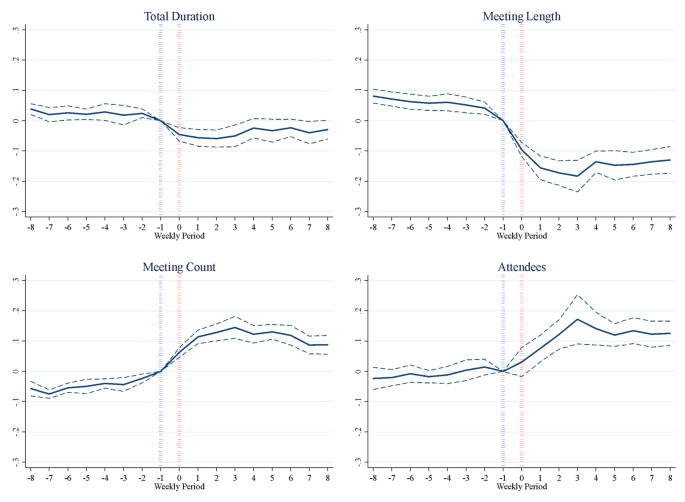

We find an increase in the total meeting count (+12.9% [CI: +11.4% to +14.4%], +0.8 meetings per person per day) Footnote 1 , a decrease in the average meeting duration (−20.1% [−23.0% to −17.1%], −12.1 min per meeting), and an increase in the average number of attendees (+13.5% [+10.6% to +16.5%], +2.1 attendees per meeting). Our results suggest that organizations in the post-lockdown period had shorter, more frequent meetings with more attendees than in the prior period. Additionally, we find that the net effect of all these changes was to significantly reduce the total number of hours employees spent in meetings during the post-lockdown period (−11.5% [−14.3% to −8.7%], −18.6 min per person per day). We report these models in the Appendix in Table A2 .

After assessing the overall post-lockdown changes in meeting activities, we conducted more granular tests to understand how these changes unfolded week by week. Using a similar regression specification, but with dummy variables corresponding to each week, we computed the weekly change in digital communication patterns following the enacted lockdown relative to the base week. In this weekly specification, we find consistent increases in the size and count of meetings and consistent decreases in the length of meetings each week after the lockdown date. The cumulative effect of these changes is a decrease in the total amount of hours employees spend in meetings each week after the lockdown date, relative to the base week. We report the coefficients, denoting the weekly changes in communication relative to the base week and corresponding standard errors, in Table 2a , and graph these coefficients in Fig. 1 .

Depiction of the coefficients from Table 2a .

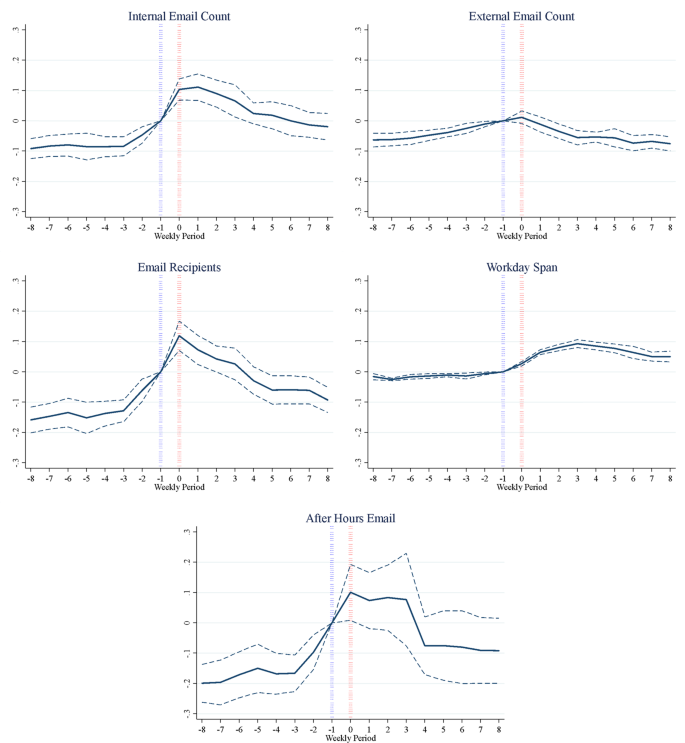

Turning to emails, we find that two types of email communication increased in the post-lockdown period. First, the average number of internal emails sent increased (+5.2% [+3.0% to +7.6%], +1.4 emails per person per day). Additionally, there is a significant increase in the average number of recipients included in emails sent in the post-lockdown period (+2.9% [+0.3% to +5.5%], +0.25 recipients per email sent). However, external emails did not significantly change in the post-lockdown period. We report the coefficients, denoting the weekly changes in communication relative to the base week and corresponding standard errors, in Table 2b , and graph these coefficients in Fig. 2 . To better understand how these results unfold over time, we analyze our main email measures up to nine months after the initial lockdowns. Appendix Table A5 depicts results from our main specification for all email measures, controlling for industry-level fixed effects. We find that, even 9 months after the lockdown, the total number of internal emails sent remains significantly higher than pre-lockdown levels. However, the average number of email recipients appears to return to pre-lockdown levels by the third month. We interpret this as evidence that certain changes to communication activity, such as increases in the total number of emails sent, reflect enduring changes to digital communication that are associated with the semi-permanent adoption of remote work. In contrast, other changes, such as increases in the average number of recipients per email, are less durable and fade in the immediate aftermath of lockdowns.

Depiction of the coefficients from Table 2b .

We find that the average workday span, defined as the span of time from the first to the last email sent or meeting attended in a 24-h period, increased by +48.5 min (+8.2% [+7.1% to +9.3%]). Consistent with longer workdays, emails sent after business hours also increased (+8.3% [+4.0% to +12.7%], +0.63 emails per person per day). We report these details in the Appendix in Table A2 . Even in the weekly specification, the employee’s average workday span remains elevated, higher than pre-pandemic levels, for the eight post-lockdown weeks examined in the weekly specification. Furthermore, the total number of emails sent increases steeply the week of the lockdown and then decreases persistently in the weeks after, returning to pre-lockdown levels around week four.

We run numerous analyses with different weighting and aggregation schemes to ensure that our results are consistent across specifications. All results, except for email recipients, are robust to weighting regressions by the total number of users in each MSA, as described in the Appendix in Table A3 . Next, we run additional analyses using weekly instead of daily aggregations, reported in the Appendix in Table A4 . These models are consistent with our main set of findings, regardless of the level of aggregation chosen. Furthermore, in additional analysis (available upon request), we examined whether the changes in communication activity observed in the data were driven by specific sectors of the economy, but found similar responses, both in terms of sign and magnitude, across various industries.

Interestingly, Europe is more negatively impacted by the lockdowns than other cities in our sample when controlling for relevant holidays. However, this could be due to a greater intensity of the lockdown regulations in these areas, disrupting life more in the first two months of the pandemic. It is also possible that pre-existing work–life balance norms in European countries contributed to this result due to a ceiling effect. That is, cities with low baseline levels of communication, perhaps owing to stronger work–life balance norms, have more room to increase their email and meeting activity than cities with higher baseline levels of communication. Lastly, we confirm that the user base remains similar throughout this period and share a graphical depiction of meeting and email users in the Appendix in Figs. B1 and B2 .

Careful inspection of these weekly results reveals that some communication patterns began to change even earlier than one week before the lockdown. To account for this variation, we reran the main analysis, but set the reference category to 8 weeks before the lockdown date to formally test whether meeting and email trends 8 weeks into a lockdown were different from the trends observed 8 weeks before the lockdown. We share these results in the Appendix in Figs. B3 and B4 . With few exceptions, we find that the broad trends in meeting and email activity described above hold regardless of whether the reference week is 8 weeks before the lockdown or one week before the lockdown.

Furthermore, we share additional analysis by MSA and industry. We graph each measure by MSA in the Appendix in Figs. B5 – B14 . Lastly, in Appendix Fig. B15 , we provide an industry analysis showing the heterogeneous effect of industry on email intensity, based on the additional industry-level data provided in the secondary data set. This analysis confirms that our results do not vary much by industry. The only industry differentially affected by the pandemic lockdown is the services industry (excluding financial services). In the services industry, we find that email communication does not recover as quickly as other industries after the lockdown, possibly suggesting a reduction in demand for in-person services.

With the COVID-19 pandemic forcing employees worldwide to work from home, organizations have had to make challenging and urgent decisions about how best to utilize digital communication technology in the absence of a shared physical workspace. Our paper examines two important types of digital communication—meeting and email activity—and shows that on average, employees significantly changed their communication behavior in response to the pandemic. While our results are more descriptive in nature and cannot rule out several competing explanations for the observed findings, the existing literature does help us to identify which explanations are most plausible. Overall, our results suggest that the organizations made communication trade-offs in response to the pandemic, increasing meeting and email activity in terms of frequency and the number of people included, but decreasing the overall time spent doing these activities. While our data cannot speak to whether these changes were due to explicit strategic managerial decisions or a consequence of organizations transitioning to remote work, these patterns are consistent with the idea that virtual forms of communication were leveraged to replace the face-to-face interaction typical in an office setting in a way that might have freed up time for employees to get work accomplished throughout the day.

Though an increase in the quantity of virtual communication is perhaps unsurprising in the middle of a pandemic, the extant literature could not have predicted the specific ways in which this occurred. The literature does, however, help us interpret our findings. For example, despite the potential drawbacks of large meetings or emails with many recipients, these forms of communication practices may help synchronize how information is shared (Allen et al., 2015 ; Cohen et al., 2011 ; Mroz et al., 2018 ). Furthermore, expanding the number of email recipients and meeting attendees increases the likelihood that important information is received by all relevant individuals in an organization (Skovholt and Svennevig, 2006 ).

The hypothesis that organizations were forced to leverage meetings and emails as an imperfect substitute to face-to-face interaction is plausible. Still, one finding that should be explained is why internal emails increased (and remained significantly higher than pre-lockdown levels even 9 months after lockdowns), but external email communication did not. One possibility is that communication turned inward as organizations adapted to remote work. Organizations working remotely for the first time likely have a greater need to use email for internal activities (e.g. synchronizing work activity, enforcing accountability, and communicating information), than for external activities, such as establishing new external partnerships. Another important possibility is that a meaningful amount of external communication in our dataset consisted of mass emails sent out as part of newsletters or promotional campaigns, rather than unique external communication efforts with specific individuals. If these mass emails were automated before the pandemic, and therefore not subject to changes in remote working status, then we would not expect to observe significant increases in external communication.

In addition to observing increases in internal email communication, we also observed important changes to meeting activity. Specifically, we found an increase in the frequency and size of meetings, which can be explained by the fact that virtual work limits opportunities for in-office social engagement and serendipitous information sharing with other employees. Managers may have found it necessary to correct this problem by increasing the frequency of “all-hands” meetings for their teams or departments to overcome feelings of social isolation (Carletta et al., 2000 ; Nilles, 1994 ) and maintain a sense of identification with the organization (Wiesenfeld et al., 1999 ).

The observed decline in meeting length is also consistent with research on virtual teams, which finds that employees find it harder to stay engaged in long, virtual meetings compared to in-person meetings (Wasson, 2004 ; Cummins, 2020 ). Additionally, natural distractions at home which compete for attention, such as demands from family and household responsibilities, may make it even harder to focus during a working day (Cummins, 2020 ; Davis and Green, 2020 ). The collective effect of these demands on attention may have motivated managers to shorten the average length of meetings to avoid overwhelming employees adjusting to working-from-home.

The joint effect of having both an increase in meeting frequency and a decrease in meeting length suggests an interesting possibility that meetings may have become more difficult to coordinate efficiently while organizations adapted to working remotely. A greater quantity of meetings involving a greater number of people implies a substantial requirement for coordination among attendees to schedule these meetings. For at least some of these employees, it would be impossible to schedule meetings consecutively so as to minimize interruption to work activity. From the perspective of employee well-being, the total amount of time spent in meetings is less important than the total number of interruptions (Rogelberg et al., 2006 ). For employees involved in highly interdependent tasks (Barrick et al., 2002 ), an increased quantity of meetings may result in greater distraction and deterioration of well-being over time, even if the net amount of time spent in these meetings is decreasing.

Consistent with this possibility, our findings also point to a spillover of virtual communication beyond normal working hours. Employees worked an average of 48.5 min longer after COVID-19 lockdowns, and were significantly more likely to send emails outside of standard working hours. This points to yet another trade-off organizations should be sensitive to—the decision to expand the scope and frequency of communications, with all its attendant coordination costs, is synonymous with a decision to expand the working day for employees. Even with reduced time spent in meetings, the work demands brought about by the pandemic, coupled with personal demands that are always close at hand, likely made it hard to meet obligations within the bounds of normal working hours.

One explanation for why employees might be working more while working from home comes from research on non-traditional work schedules. This literature has shown that managers have a tendency to view employees who take advantage of flexible working hours as less productive or committed to the organization (Chung, 2020 ; Kaplan et al., 2018 ). Given this perception, employees in virtual teams tend to work longer hours to overcome this “flexibility stigma” and to signal progress on certain assignments by communicating more regularly with managers (Chung, 2020 ; Golden and Eddleston, 2020 ). Another worrying possibility is that workers who would rather not work remotely consider having an office away from their home as essential to keeping their work and personal lives separate. For these workers, working from home may blur the distinction between work and other aspects of their personal life, which may result in them working longer hours without being fully aware of doing so.

Some employees may work a similar amount of time, but spread across an irregular schedule, increasing the span of their workdays. Employees working from home, for example, may decide to take periodic breaks throughout the day to accommodate idiosyncratic demands associated with home life (e.g. childcare, spousal responsibilities, etc.) and compensate for these breaks by working later. Because our measure of the working day is computed by taking the length of time between the first and last meeting or email each day, it does not necessarily capture the total amount or intensity of working time. Despite this caveat, the possibility that employees’ working hours have become less regular is still an important feature of work during the pandemic, as there are well-studied consequences to deviating from formal, organization-wide working schedules (e.g. Piasna, 2018 ; Joshi and Bogen, 2007 ).

In addition to estimating the effects of COVID-related lockdowns on patterns of digital communication, our results also offer a few relevant insights for managers and leaders within organizations. First, our data show that organizations are not merely reactive, but remarkably proactive to external shocks. Organizations of different sizes, in different industries, in different parts of the world, changed their patterns of digital communication at least one full week, on average, before government-imposed lockdowns. That is, our findings show that organizations can (and did) rapidly adjust their communication patterns in anticipation of formal policy requirements or response to local environmental conditions (e.g., the increasing spread of the virus in workplaces.) This degree of responsiveness is surprising when juxtaposed with the literature showing that many organizations can be slow to adapt and change, especially as they become large or are required to respond to rapid political and regulatory change (Woods, 2020 ; Wright et al., 2004 ).

Second, our findings point to the utility of passively collected digital communications data. It is worth noting that this study would not have been possible 20 years ago. Researchers would have had to infer the organizational impact of the crisis via survey data shared from a smaller number of organizations, and such data would have taken months, if not years, to collect. Today, however, because of the widespread use of calendar platforms by organizations that automatically collect communications meta-data, it is now possible to glimpse the impact of any event on organizational communication in real-time (Salganik et al., 2020 ). Because we wanted to ensure our results apply to a large number of organizations, we limited our analysis to broad communication measures shared across organizations worldwide. However, communications data can be collected at a much more granular level than the measures used in this paper. For example, Yang et al. ( 2021 ), in a study that complements our broader approach, examines network data at greater depth for a single firm to show that collaboration networks have become more siloed since the adoption of remote work.

Lastly, our findings have implications for managers by highlighting the importance of considering the trade-offs in organizational communication. Shortly after COVID-related lockdowns were imposed, managers found themselves in charge of newly remote workers and had to decide, in real-time, how best to communicate with employees. Difficult decisions had to be made regarding how many emails to send to employees, how many people to include on meeting invitations, and how frequently to schedule “check-in” meetings to heighten accountability. While our data cannot speak to whether managers consciously made these decisions, our data do show meaningful trade-offs in the dimensions of communication activity. In the context of meetings, organizations varied along different dimensions of meeting activity: the number of meetings, the size of meetings, and the length of meetings. While our paper focuses on the short-term response to the emergency situation created by the pandemic, in the long run, the correct balance of these parameters may vary across organizations. How managers and organizations proactively think about the ideal balance of these parameters (if at all) is an important question for future research.

Limitations

While our data establish that employees changed their email and meeting activity patterns in response to lockdowns, our findings are not without limitations. First, our data only represent a subset of the possible communication occurring within a firm. Non-email communication, such as messaging via consumer or other business communication platforms, and informal meetings not scheduled via calendar invitations, are not reflected in our data. Our analysis does not capture these cross-platform substitutions outside our provider’s data. Therefore, this paper’s findings should be interpreted cautiously as the effect of COVID-19 lockdowns on more formal digital communication patterns, the email and meeting activity facilitated through the company’s communication platform, rather than the net effect of all communication occurring within a firm. As such, other types of communication (e.g. watercooler conversations, instant messenger, phone calls, etc.) were not captured by our email provider’s email and calendar system and were not analyzed in our study. As a result, our analysis may miss important ways in which organizations responded to the pandemic by increasing their use of non-email and meeting channels. For example, organizations might have reacted to the loss of serendipitous in-person conversation by increasing their use of other business communication platforms, like Slack or Microsoft Teams, which are not captured in our data.

A second limitation is that at least three distinct events or phenomena can occur in concert with COVID-related lockdowns: firms transition to remote work, there is a shock to demand due to macroeconomic forces, and behavior is changed for non-work-related reasons. Even controlling for industry and firm size, we cannot disentangle which of these forces is responsible for the effects observed in the paper. As such, the effects documented in the paper should be interpreted as the joint effect of all the forces that co-occur with COVID-19 lockdowns. Related to this, we treat all government-mandated lockdowns as similar in terms of their influence on organizational communication. In reality, firms may have responded to lockdowns in distinct and important ways. For example, Yang et al. ( 2021 ) note that some firms may have adopted a “hybrid work model” in response to the pandemic in which employees spend part of their week working remotely and the other part working in the office. Other organizations are more likely to adopt a “mixed-mode” model in which some employees work remotely full-time, and other employees are full-time office workers. Whether a firm adopted a hybrid working model, a mixed-mode model, or something more extreme has important implications for assessing the impact of remote work on organizational communication.

Third, even though we take great lengths to ensure that calendar data reflects real organizational activity, there is still the possibility that some fraction of our meeting meta-data may not perfectly capture organizational work. For our meeting length variable, a similar problem occurs if a meeting lasts longer or shorter than scheduled on the calendar. The extent to which meeting length, frequency, and size are incorrectly estimated will likely vary substantially across firms, but we have no reason to expect that this bias will vary systematically in a particular direction rendering our estimates unreliable. Measurement error of this sort also does not diminish the practical significance of the results.

Given the unprecedented nature of the changes wrought by COVID-19, it was unclear from the outset how employees would adapt their communication patterns as they transitioned to working from outside their offices. We find that COVID-related lockdowns are associated with: (1) an increase in the total volume of meeting and email activity; (2) a decrease in the average length of meetings; and (3) an increase in the span of the workday. We also found an increase in the average size of meetings and a decrease in the total amount of time spent in meetings after the implementation of COVID-19 lockdowns.

In analyzing digital communication patterns across a large number of firms and regions, we build upon an emerging literature that uses communication meta-data to measure the relationship between patterns of communication and organizational outcomes (Impink et al., 2020 ; Polzer et al., 2018 ; Kleinbaum et al., 2013 ; Srivastava et al., 2018 ). More substantively, we contribute to the literature on virtual work, which has traditionally focused on the impact to organizations when a small subset of employees voluntarily transition to remote work (e.g., Bloom et al., 2013 ; Choudhury et al., 2019 ). Our findings clarify how core communicative functions in an organization change when remote work is implemented under less auspicious conditions—when the transition is mandatory and involves entire organizations.

Data availability

Please contact the corresponding author: Jeffrey Polzer ([email protected]) to be provided with information on how to contact the email provider in our study to apply for access to use the data or to be provided with the code (R and STATA) used to run our analyses.

The details reported in parentheticals are the following: the percentage change of the outcome variable compared to pre-lockdown levels computed from the regression, the 95% confidence interval for this percentage change, and the raw change in the outcome variable in its original units.

Allen TD, Golden TD, Shockley KM (2015) how effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychol Sci Public Interest 16(2):40–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100615593273

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Allen JA, Lehmann-Willenbrock N, Rogelberg SG (Eds) (2015) The Cambridge handbook of meeting science. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY

Google Scholar

Allen JA, Tong J, Landowski N (2020) Meeting effectiveness and task performance: meeting size matters. J Manag Dev. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-12-2019-0510

Arnfalk P, Kogg B (2003) Service transformation—managing a shift from business travel to virtual meetings. J Clean Prod 11(8):859–872. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-6526(02)00158-0

Article Google Scholar

Barrick MR, Stewart GL, Piotrowski M (2002) Personality and job performance: test of the mediating effects of motivation among sales representatives. J Appl Psychol 87(1):43–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.43

Bloom N, Liang J, Roberts J, Ying ZJ (2013) Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment (No. w18871 ) . National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w18871

Cao H, Lee C-J, Iqbal S, Czerwinski M, Wong PNY, Rintel S, Hecht B, Teevan J, Yang L (2021) Large scale analysis of multitasking behavior during remote meetings. In: Association for Computer Machinery (ACM) (eds), Proceedings of the 2021 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems. Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 1–13.

Carletta J, Anderson AH, McEwan R (2000) The effects of multimedia communication technology on non-collocated teams: a case study. Ergonomics 43(8):1237–1251. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140130050084969

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Choudhury P, Foroughi C, Larson B (2019). Work-from-anywhere: the productivity effects of geographic flexibility. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3494473

Chung H (2020) Gender, flexibility stigma and the perceived negative consequences of flexible working in the UK. Soc Indic Res 151(2):521–545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-2036-7

Cohen MA, Rogelberg SG, Allen JA, Luong A (2011) Meeting design characteristics and attendee perceptions of staff/team meeting quality. Group Dyn: Theory Res Pract 15(1):90–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021549

Cummins E (2020). Why you can’t help screwing around while working from home. Vox. https://www.vox.com/the-highlight/21317485/work-from-home-coronavirus-covid-19-zoom-distraction-animal-crossing

Daft RL, Lengel RH (1986) Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Manag Sci 32(5):554–571. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.32.5.554

Davis M, Green J (2020) Three hours longer, the pandemic workday has obliterated work–life balance. Bloomberg.Com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-04-23/working-from-home-in-covid-era-means-three-more-hours-on-the-job

Deakin H, Wakefield K (2014) Skype interviewing: reflections of two PhD researchers. Qual Res 14(5):603–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794113488126

Denstadli JM, Julsrud TE, Hjorthol RJ (2012) Videoconferencing as a mode of communication: a comparative study of the use of videoconferencing and face-to-face meetings. J Bus Tech Commun 26(1):65–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651911421125

DeSanctis G, Poole MS, Dickson GW, Jackson BM (1993) Interpretive analysis of team use of group technologies. J Organ Comput 3(1):1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/10919399309540193

Donnelly N, Proctor-Thomson SB (2015) Disrupted work: home-based teleworking (HbTW) in the aftermath of a natural disaster (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2583246). Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12040

Dye KC, Eggers JP, Shapira Z (2014) Trade-offs in a Tempest: stakeholder influence on hurricane evacuation decisions. Organ Sci 25(4):1009–1025. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2013.0890

Golden TD, Eddleston KA (2020) Is there a price telecommuters pay? Examining the relationship between telecommuting and objective career success. J Vocat Behav 116:103348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.103348

Han H, Hiltz SR, Fjermestad J, Wang Y (2011) Does medium matter? A comparison of initial meeting modes for virtual teams. IEEE Trans Prof Commun 54(4):376–391. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2011.2175759

Henderson Jr, GV (1990). Problems and solutions in conducting event studies. J. Risk Insur 282–306.

Impink SM, Prat A, Sadun R (2020) Measuring collaboration in modern organizations. AEA Pap Proc 110:181–186. https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20201068

Joshi P, Bogen K (2007) Nonstandard schedules and young children’s behavioral outcomes among working low-income families. J Marriage Family 69(1):139–156

Kaplan S, Engelsted L, Lei X, Lockwood K (2018) Unpackaging manager mistrust in allowing telework: comparing and integrating theoretical perspectives. J Bus Psychol 33(3):365–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-017-9498-5

Kleinbaum AM, Stuart TE, Tushman ML (2013) Discretion within constraint: homophily and structure in a formal organization. Organ Sci 24(5):1316–1336. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1120.0804

Kothari SP, Warner JB (2007). Econometrics of event studies. In Handbook of empirical corporate finance (pp. 3–36). Elsevier.

Kurland NB, Bailey DE (1999) Telework: The advantages and challenges of working here, there, anywhere, and anytime. Organ Dyn 28(2):53–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0090-2616(00)80016-9

Larsen J, Urry J, Axhausen K (2008) Coordinating face-to-face meetings in mobile network societies. Inf Commun Soc 11(5):640–658

Lyons K, Kim H, Nevo, S (2010) Paying attention in meetings: Multitasking in virtual worlds. In First Symposium on the Personal Web, Co-located with CASCON (Vol. 2005, p. 7).

Maurer R (2020) Some companies are making virtual internships work during COVID-19. Remote work. Retrieved, 5 October 2020 from https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/talent-acquisition/pages/remote-virtual-internships-covid19-hr.aspx ).

Mroz JE, Allen JA, Verhoeven DC, Shuffler ML (2018) Do we really need another meeting? The science of workplace meetings. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 27(6):484–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721418776307

Nardi BA, Whittaker S (2002) The place of face-to-face communication in distributed work. In: The MIT Press. Distributed work. Boston Review, pp. 83–110.

Nilles JM (1994) Making telecommuniting happen: a guide for telemanagers and telecommuters. https://trid.trb.org/view/405282

Piasna A (2018) Scheduled to work hard: the relationship between non-standard working hours and work intensity among European workers (2005–2015). Hum Resource Manag J 28(1):167–181

Polzer JT, DeFilippis E, Tobio K (2018) Countries, culture, and collaboration. Acad Manag Proc 2018(1):17645. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2018.17645abstract

Rogelberg SG, Leach DJ, Warr PB, Burnfield JL (2006) “Not another meeting!” Are meeting time demands related to employee well-being? J Appl Psychol 91(1):83

Rogelberg SG, Allen JA, Shanock L, Scott C, Shuffler M (2010) Employee satisfaction with meetings: a contemporary facet of job satisfaction. Hum Resource Manag (Published in Cooperation with the School of Business Administration, The University of Michigan and in alliance with the Society of Human Resources Management) 49(2):149–172

Salganik MJ, Lundberg I, Kindel AT, Ahearn CE, Al-Ghoneim K, Almaatouq A, ... & McLanahan S (2020) Measuring the predictability of life outcomes with a scientific mass collaboration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117(15):8398–8403

Seitz S (2016) Pixilated partnerships, overcoming obstacles in qualitative interviews via Skype: a research note. Qual Res 16(2):229–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794115577011

Sproull L, Kiesler S (1986) Reducing social context cues: electronic mail in organizational communication. Manag Sci 32(11):1492–1512. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.32.11.1492

Srivastava SB, Goldberg A, Manian VG, Potts C (2018) Enculturation trajectories: language, cultural adaptation, and individual outcomes in organizations. Manag Sci 64(3):1348–1364. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2016.2671

Skovholt K, Svennevig J (2006) Email copies in workplace interaction. J Comput-Mediat Commun 12(1):42–65

Stray VG, Lindsjørn Y, Sjøberg DI (2013). Obstacles to efficient daily meetings in agile development projects: a case study. In: ACM Woods. Benoît J, Hervé L, Corinne B, Claude G (eds) 2013 ACM/IEEE international symposium on empirical software engineering and measurement. IEEE, pp. 95–102

Wasson C (2004) Multitasking during virtual meetings. Hum Resource Plan 27(4):47

White M (2014) The management of virtual teams and virtual meetings. Bus Inf Rev 31:111–117

Wiederhold BK (2020) Connecting through technology during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: avoiding “zoom fatigue”. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 23(7):437–438. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.29188.bkw

Wiesenfeld BM, Raghuram S, Garud R (1999) Communication patterns as determinants of organizational identification in a virtual organization. Organ Sci 10(6):777–790. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.10.6.777

Wiesenfeld BM, Raghuram S, Garud R (2001) Organizational identification among virtual workers: the role of need for affiliation and perceived work-based social support. J Manag 27(2):213–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630102700205

Woods DD (2020) The strategic agility gap: how organizations are slow and stale to adapt in turbulent worlds. In: Human and organisational factors. Springer, Cham, pp. 95–104

Wright G, Van Der Heijden K, Bradfield R, Burt G, Cairns G (2004) The psychology of why organizations can be slow to adapt and change. J General Manag 29(4):21–36

Yang L, Holtz D, Jaffe S, Suri S, Sinha S, Weston J, Joyce C, Shah N, Sherman K, Hecht B, Teevan J (2021) The effects of remote work on collaboration among information workers. Nat Hum Behav 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01196-4 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Harvard University, Cambridge, USA

Evan DeFilippis, Jeffrey T. Polzer & Raffaella Sadun

New York University, New York, USA

Stephen Michael Impink

Stanford University, Stanford, USA

Madison Singell

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jeffrey T. Polzer .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Additional information.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

DeFilippis, E., Impink, S.M., Singell, M. et al. The impact of COVID-19 on digital communication patterns. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9 , 180 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01190-9

Download citation

Received : 18 September 2021

Accepted : 28 April 2022

Published : 23 May 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01190-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

“the magic triangle between bed, office, couch”: a qualitative exploration of job demands, resources, coping, and the role of leadership in remote work during the covid-19 pandemic.

- Elisabeth Rohwer

- Volker Harth

- Stefanie Mache

BMC Public Health (2024)

Emotional, coping factors and personality traits that influenced alcohol consumption in Romanian students during the COVID-19 pandemic. A cross-sectional study

- Cornelia Rada

- Cristina Faludi

- Mihaela Lungu

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

The Role of Crisis Communication in the COVID-19 pandemic

By Anushka Singh

Over the past year, the coronavirus outbreak has created uncertainty, stress, emotional disruption, and more in the world. Businesses and organizations are struggling to provide their stakeholders with the appropriate set of resources to overcome the current crisis. During a crisis, effective communication is essential. Business leaders need to communicate with transparency and empathy consistently. Effective communication helps build trust and hope in organizations and their efforts to adapt to the challenges they face. However, seeing how the world has never seen a crisis quite like this one in the past, leaders, and communicators are struggling to design a crisis communication plan that connects with employees, communities, and other stakeholders. Leaders and communicators need to be careful about the course of action they take while creating crisis plans, making sure it is appropriate, informative, and effective.

Some worthwhile tips for creating a strong crisis plan include:

Making sure all communication efforts are consistent, clear, and continual. A crisis, especially one as long as this pandemic, limits people’s ability to cope with excessive amounts of information. Continual communication efforts reduce fear amongst stakeholder groups and guarantee that these groups have understood the organization’s key messages over time and build trust. With so much negativity in the world, leaders and communicators need to make the messaging as positive, reassuring, and hopeful as possible and remind their stakeholder groups of ways the organization has faced and overcome challenges in the past.

Helping stakeholder groups cope with the emotional disruption that comes along with this crisis. Leaders and communicators should put out frequent messages that focus on helping employees, customers, surrounding communities deal with the global pandemic. Leaders and communicators need to go beyond just focusing on how this crisis impacts the organization – but also focus on the stakeholder groups involved. Through crisis messaging, leaders and communicators should try and build a community and focus on its common social identity. For instance, creating virtual campaigns that allow for employees to interact with one another – outside of work – can encourage employee morale. Additionally, the organization should also focus on ensuring that its messaging with various stakeholder groups is one-to-one and varies between each group.

Reminding stakeholder groups of the organization’s goals and missions. Leaders and communicators need to ensure that all messaging ties back to a deeper sense of purpose. Early on in the crisis, organizations need to emphasize their goals during this pandemic. Oftentimes, especially during a long-drawn crisis, stakeholder groups can lose sight of the overarching purpose of the organization before the crisis. It is important for communicators to remind stakeholders of these missions and goals and work towards achieving them during the crisis. For instance, if an organization prides itself on serving its employees, the crisis plan should involve ways in which the organization can support its employees – like providing them with wellness days, sick leave (with pay), and more.

The unexpected and long-lasting nature of the coronavirus outbreak has led to hesitancy and skepticism when it comes to creating a crisis plan. However, leaders and communicators must remember that everyone is in the same boat with respect to implementing a new kind of crisis plan. Organizations must set aside time, effort, and resources to formulate a well-thought-out, strategic plan which acknowledges the lows, emphasizes the highs, and frames a clear plan for the future.

Source: https://www.mckinsey.com/ business-functions/ organization/our-insights/a- leaders-guide-communicating- with-teams-stakeholders-and- communities-during-covid-19

Share this:

5 Lessons for Communicating About Coronavirus

- March 17, 2020

- By Susan Krenn | Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs Executive Director

The coronavirus pandemic has put the business of risk communication front and center. Every day, it seems, we are getting mixed messages from our leaders, messages that differ in their tone and content depending on who is talking.

In a situation full of unknowns, as with the early days of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa five years ago, sometimes communication is all we have. Good communication lets people know what they should do, how they can protect themselves and others and helps them balance their fears with concrete information they can use.

Here are some communication lessons to keep in mind as the coronavirus interrupts life as we know it. So much has already changed, with the closure of schools, restaurants and gyms, many workers being asked to stay away from the office, the cancellation of major life celebrations such as weddings and graduations and directives to keep our distance from one another. What is key is that we focus on how to help one another navigate the way forward.

- Build trust: People need information from sources with expertise and they need to hear from trusted public health experts at regular intervals. If incorrect information is shared, experts need to correct the record quickly to ensure that trust is maintained. And when too much time passes between communications, people tend to fill the void with inaccurate information from unreliable sources. Be honest about what you know – and don’t know – in a crisis.

- Have one set of messages: All spokespeople must be on the same page. This is crucial so that people know exactly what to do to reduce the spread of the virus. Otherwise, people make up their own minds about how to behave – which won’t slow the spread of disease.

- Counter myths and misinformation: Ignoring rumors and hoping that they dissipate on their own is a poor course of action, especially in a crisis. Create a system to dispel myths and correct the record by sharing the clear, accurate messages that experts have agreed on.

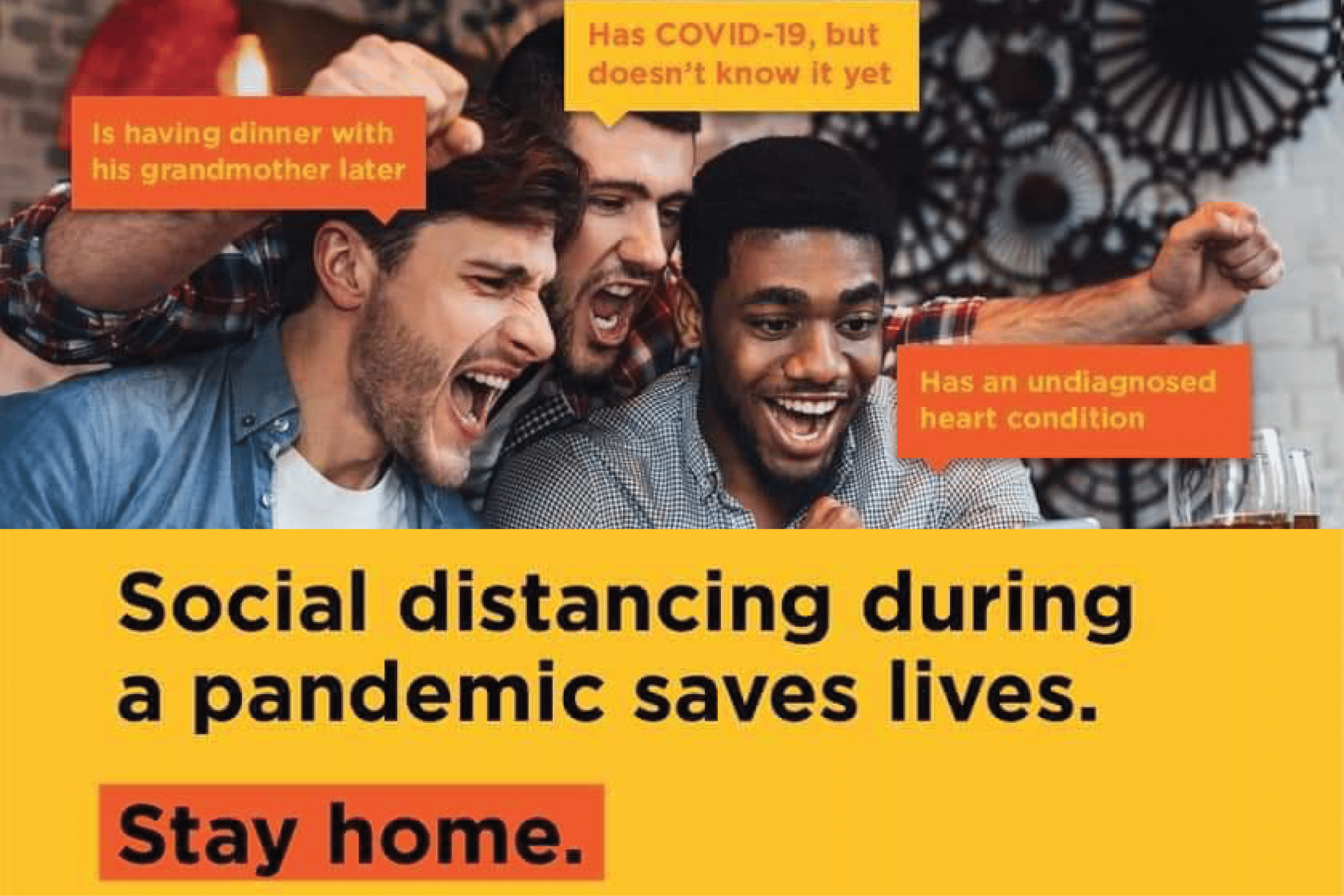

- Promote action: In an unprecedented crisis, some people just don’t know what to do and why to do it. Being anxious right now is completely normal, but we need to balance that with the ability to act to prevent paralysis. Giving them concrete things to do calms anxiety and promotes a restored sense of control. We’ve already seen some people change social norms, such as avoiding hugs and handshakes upon greeting. Our trusted leaders need to role model this behavior and talk about what else people can do to protect themselves such as vigorous handwashing, avoiding public events and settings and keeping your distance from others, especially older people who are particularly at risk for complications.

- Be empathetic: We are all in this together and we need communication that reflects this. The unknowns are scary, but helping people understand that they need to take action for the greater good can help foster community.

For more information on the coronavirus:

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter

Related posts.

CCP Launches Campaign to Promote Vaccination During Africa Cup of Nations Tournament

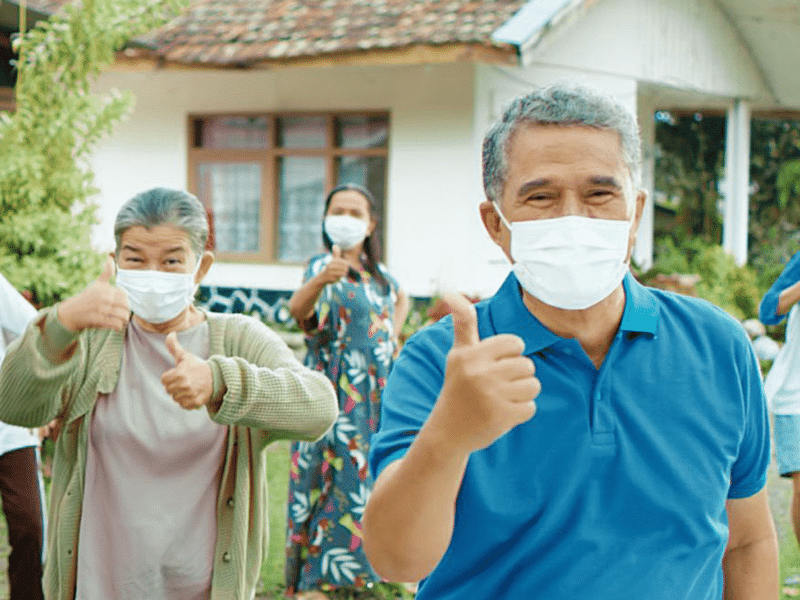

Integrating COVID-19 Vaccines into Basic Health Care

Elderly Heroes Help Fellow Indonesians Get COVID-19 Vaccines

Subscribe to ccp's monthly newsletter.

Receive the latest news and updates, tools, events and job postings in your inbox every month

Privacy Policy

Communication During a Pandemic

Featured Clinical Reviews

- Screening for Atrial Fibrillation: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement JAMA Recommendation Statement January 25, 2022

- Evaluating the Patient With a Pulmonary Nodule: A Review JAMA Review January 18, 2022

Select Your Interests

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine