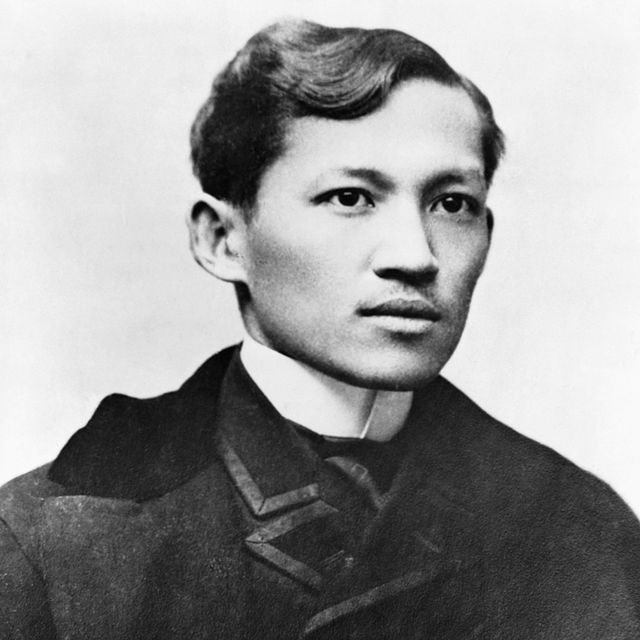

(1861-1896)

Who Was José Rizal?

While living in Europe, José Rizal wrote about the discrimination that accompanied Spain's colonial rule of his country. He returned to the Philippines in 1892 but was exiled due to his desire for reform. Although he supported peaceful change, Rizal was convicted of sedition and executed on December 30, 1896, at age 35.

On June 19, 1861, José Protasio Rizal Mercado y Alonso Realonda was born in Calamba in the Philippines' Laguna Province. A brilliant student who became proficient in multiple languages, José Rizal studied medicine in Manila. In 1882, he traveled to Spain to complete his medical degree.

Writing and Reform

While in Europe, José Rizal became part of the Propaganda Movement, connecting with other Filipinos who wanted reform. He also wrote his first novel, Noli Me Tangere ( Touch Me Not/The Social Cancer ), a work that detailed the dark aspects of Spain's colonial rule in the Philippines, with particular focus on the role of Catholic friars. The book was banned in the Philippines, though copies were smuggled in. Because of this novel, Rizal's return to the Philippines in 1887 was cut short when he was targeted by police.

Rizal returned to Europe and continued to write, releasing his follow-up novel, El Filibusterismo ( The Reign of Greed ) in 1891. He also published articles in La Solidaridad , a paper aligned with the Propaganda Movement. The reforms Rizal advocated for did not include independence—he called for equal treatment of Filipinos, limiting the power of Spanish friars and representation for the Philippines in the Spanish Cortes (Spain's parliament).

Exile in the Philippines

Rizal returned to the Philippines in 1892, feeling he needed to be in the country to effect change. Although the reform society he founded, the Liga Filipino (Philippine League), supported non-violent action, Rizal was still exiled to Dapitan, on the island of Mindanao. During the four years Rizal was in exile, he practiced medicine and took on students.

Execution and Legacy

In 1895, Rizal asked for permission to travel to Cuba as an army doctor. His request was approved, but in August 1896, Katipunan, a nationalist Filipino society founded by Andres Bonifacio, revolted. Though he had no ties to the group and disapproved of its violent methods, Rizal was arrested shortly thereafter.

After a show trial, Rizal was convicted of sedition and sentenced to death by firing squad. Rizal's public execution was carried out in Manila on December 30, 1896, when he was 35 years old. His execution created more opposition to Spanish rule.

Spain's control of the Philippines ended in 1898, though the country did not gain lasting independence until after World War II. Rizal remains a nationalist icon in the Philippines for helping the country take its first steps toward independence.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Jose Rizal

- Birth Year: 1861

- Birth date: June 19, 1861

- Birth City: Calamba, Laguna Province

- Birth Country: Philippines

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: José Rizal called for peaceful reform of Spain's colonial rule in the Philippines. After his 1896 execution, he became an icon for the nationalist movement.

- Science and Medicine

- Journalism and Nonfiction

- World Politics

- Astrological Sign: Gemini

- University of Madrid

- University of Heidelberg

- University of Santo Tomas

- Nacionalities

- Death Year: 1896

- Death date: December 30, 1896

- Death City: Manila

- Death Country: Philippines

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: José Rizal Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/political-figures/josé-rizal

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: May 3, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- [C]reative genius does not manifest itself solely within the borders of a specific country: it sprouts everywhere; it is like light and air; it belongs to everyone: it is cosmopolitan like space, life and God.

- What is the use of independence if the slaves of today will be the tyrants of tomorrow?

- Tomorrow at seven, I shall be shot; but I am innocent of the crime of rebellion. I am going to die with a tranquil conscience.

Famous Political Figures

10 of the First Black Women in Congress

Kamala Harris

Deb Haaland

Why Lewis Strauss Didn’t Like Oppenheimer

Madeleine Albright

These Are the Major 2024 Presidential Candidates

Hillary Clinton

Indira Gandhi

Toussaint L'Ouverture

Vladimir Putin

Kevin McCarthy

15 Mar Rizal’s Education

Jose Rizal’s first teacher was his mother, who had taught him how to read and pray and who had encouraged him to write poetry. Later, private tutors taught the young Rizal Spanish and Latin, before he was sent to a private school in Biñan.

When he was 11 years old, Rizal entered the Ateneo Municipal de Manila. He earned excellent marks in subjects like philosophy, physics, chemistry, and natural history. At this school, he read novels; wrote prize-winning poetry (and even a melodrama—“Junto al Pasig”); and practiced drawing, painting, and clay modeling, all of which remained lifelong interests for him.

Rizal eventually earned a land surveyor’s and assessor’s degree from the Ateneo Municipal while taking up Philosophy and Letters at the University of Santo Tomas. Upon learning that his mother was going blind, Rizal opted to study ophthalmology at the UST Faculty of Medicine and Surgery. He, however, was not able to complete the course because “he became politically isolated by adversaries among the faculty and clergy who demanded that he assimilate to their system.”

Without the knowledge of his parents, Rizal traveled to Europe in May 1882. According to his biographer, Austin Craig, Rizal, “in order to obtain a better education, had had to leave his country stealthily like a fugitive from justice, and his family, to save themselves from persecution, were compelled to profess ignorance of his plans and movements. His name was entered in Santo Tomas at the opening of the new term, with the fees paid, and Paciano had gone to Manila pretending to be looking for this brother whom he had assisted out of the country.”

Rizal earned a Licentiate in Medicine at the Universidad Central de Madrid, where he also took courses in philosophy and literature. It was in Madrid that he conceived of writing Noli Me Tangere . He also attended the University of Paris and, in 1887, completed his eye specialization course at the University of Heidelberg. It was also in that year that Rizal’s first novel was published (in Berlin).

Rizal is said to have had the ability to master various skills, subjects, and languages. Our national hero was also a doctor, farmer, naturalist (he discovered the Draco rizali , a small lizard; Apogania rizali , a beetle; and the Rhacophorus rizali , a frog), writer, visual artist, athlete (martial arts, fencing, and pistol shooting), musician, and social scientist.

References:

Craig, Austin. Lineage, Life and Labors of Jose Rizal: Philippine Patriot . http://www.gutenberg.org/files/6867/6867-h/6867-h.htm#d0e1835 , retrieved March 11, 2011.

Morris, John D. “José Rizal and the Challenge Of Philippines Independence.” http://www.schillerinstitute.org/educ/hist/rizal.html , retrieved March 11, 2011.

No Comments

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

- Friends of PE

Editor's Note

Filipino Legal

A Bit of Burgos

Diary of the Dreamer

Building Bridges

Cristy Per Minute

Life of Canadian PI

Green Building

Empowering Education

POV Philippines

Heavenly Connection

Batang North End

Career Connexion

It's All History

In Other Words

Pulis Kababayan

Medisina at Politika

Ask Ate Anna

Ask Tito Mike

Living Today

My Money Coach

Sulong Pinoy

Published on 01 December 2016

by Jon Malek

My friend and comrade Levy Abad asked me to give a brief reflection on a poem of José Rizal for a recent event of the Knights of Rizal. The event, called A Night of Poems, Songs and Essays Celebrating “Rizal the Artist,” was held the evening of November 19, 2016, at the Filipino Senior’s Centre in Winnipeg. It was a great evening of ideas and arts in honour of Rizal, one of the most famed heroes of the Philippines. As a historical figure, Rizal presents a number of contradictions. As Renato Constantino pointed out in his essay Veneration without Understanding, “In our case our national hero was not the leader of our Revolution.” Indeed, he openly condemned it. Regardless of these contradictions, though, José Rizal holds a commanding position in the Filipino mind. Regardless of his politics and brand of revolutionary spirit, Rizal has bequeathed a wealth of writing from which his kababayan can learn.

For this event, I decided to reflect upon Rizal’s poem, Education Gives Lustre to Motherland , which he wrote in 1876 as a youth. The poem, which can be read online at http://www.joserizal.ph/pm16.html , is an eloquent extolment of the value of education to Philippine youth. I chose this poem because, in my lectures at the University of Manitoba, I had been thinking a lot about the role of education in the era of imperial Asia. Throughout history, the fight for access to education has often been tied to anti-colonial movements. Denying access to education to a colonized people was a tool that colonists used to suppress and maintain control. Even when education was permitted, it was often limited and certainly not of the quality that could be had in Europe or North America. For this reason, many Asian revolutionary intellectuals – such as José Rizal or Sun Yat-Sen in China – did their schooling abroad.

For many of these revolutionaries, education was key to self-determination. For Rizal, education was the means to freedom. Important to Rizal, as expressed in Education Give Lustre to Motherland, education was not just about the classroom; it was more holistic, and importantly, it included having an artistic mind. In his poem, Rizal writes that from the lips of education

the waters crystalline Gush forth without end, of divine virtue, And prudent doctrines of her faith The forces weak of evil subdue, That break apart like the whitish waves That lash upon the motionless shoreline: And to climb the heavenly ways the people Do learn with her noble example.

In the wretched human beings’ breast The living flame of good she lights The hands of criminal fierce she ties, And fill the faithful hearts with delights, Which seeks her secrets beneficent And in the love for the good her breast she incites, And it’s th’ education noble and pure Of human life the balsam sure.

Rizal saw education not just as learning facts or practical skills, but also as an enlightenment of human strength and spirit, a realization of our potential:

And like a rock that rises with pride In the middle of the turbulent waves When hurricane and fierce Notus roar She disregards their fury and raves, That weary of the horror great So frightened calmly off they stave; Such is one by wise education steered He holds the Country’s reins unconquered.

It merits emphasis that Rizal had a special place in his heart for the Philippine youth. Indeed, when he wrote Education Gives Luster to Motherland, Rizal was 15. But what education was he talking about? Certainly, Rizal spoke of education in terms of the sciences and arts; but education was not just a matter of becoming “smart” or of gaining a livelihood. Even at a young age, as a youth himself, Rizal saw that an education was key to creating a class of Filipinos that could lead the country to freedom and self-determination.

Education was thus key to knowing oneself. Shakespeare’s famous adage from Hamlet, “To thyself be true,” rings true. Rizal was part of a larger anti-colonial movement that was beginning to sweep across Asia at the turn of the 20th century as colonized peoples discovered their own selves and histories from the ashes and sediment of imperialism. This was not a re-discovery of a pre-Hispanic past. Rizal felt that there was much that could be learned from the Spanish, and Western education more generally, but also that it must be adopted and adapted by Filipinos. Around the same time, Chinese and Japanese intellectuals were coining phrases such as borrowing “Western tricks to save China from the Westerners,” reflecting the idea of taking Western learning and applying it to Asian struggles. Rizal was part of such a re-interpretation that was occurring in the Philippines about what it meant to be Filipino in the modern world.

This movement is not one that has ended, either. In my research, I have seen the Winnipeg Filipino community work to renegotiate their identity. In newspapers from the 1970s and 1980s, one can see how a Filipino heritage within Canadian society created tensions and negotiations. Were the two at odds? By no means, just as a Filipino identity was not incompatible with a “modern” education, so long as a Filipino foundation was maintained.

What I think is the lesson of Rizal to Filipino youth today, especially migrant youth, is that this education must be holistic: it must go beyond teaching math, science, social sciences, or the arts. What we all – and migrant youth especially – need to be taught is not just facts, but how to be questioning beings. L. S. Stavrianos has argued that every new generation will ask new questions of itself and society, not because the old answers were wrong, but because the new generation has new questions.

So what happens when we fail to train a group of youth to ask their own questions? Worse, what happens when we mis-educate the youth? What happens when our school and university curriculums give little space to explore the historic diversity of Canada? What happens when Filipino youth are not taught that Filipinos have been in Canada since before the 20th century, that they have integrated and contributed exceptionally to broader Canadian society? What happens when attempts to narrate a national history extols the great actions of white settlers, but neglect the other stories? It can be no surprise that youth from such groups might then be disaffected. And I think that Winnipeg’s Filipino youth group, ANAK, understands this. When the Manila to Manitoba museum exhibit was unveiled in 2009, they asked this same question. Their answer: “You ask questions.” If we – and I mean “we” collectively – fail to engrain the value of critical inquiry upon youth, then larger failings in society will go unchecked. Elders may teach and guide from experience, but the best teachers are those who teach others to question, teach one how to ask questions that are critical and relevant. And, moreover, education must mean not simply arriving at an answer: but to go further and understand why the answer is important.

Applying Rizal’s writings on education in a modern context in which migration is a reality for many, education should include a continued and intensified preservation of heritage through an emphasis on education and openness to critical enquiry. Not only will our youth then be aware of their cultural identity, which is important in fitting into larger Canadian society, but they will also be raised as global citizens capable of critical though. Furthermore, beyond knowledge of one’s heritage, this education should include the means to produce and practice one’s heritage. I think this was one of Rizal’s major projects in his writing, to emphasize that education and self-awareness was key to the Philippines’ future self-determination and freedom. And this is what it means to live in a multicultural society like Canada: not just to be encouraged with empty words, but aided in this process of heritage preservation – in this case through meaningful education.

I’d like to end with an excerpt from Rizal’s Hymn to Labour , in a section devoted to the youth of the Philippines:

Teach, us ye the laborious work To pursue your footsteps we wish, For tomorrow when country calls us We may be able your task to finish. And on seeing us the elders will say: “Look, they’re worthy of their sires of yore!” Incense does not honour the dead As does a son with glory and valour.

Jon Malek is a PhD candidate in History at Western University, and is a member of the Migration and Ethnic Relations program.

Have a comment on this article? Send us your feedback

Search form

- ADVERTISE here!

- How To Contribute Articles

- How To Use This in Teaching

- To Post Lectures

Sponsored Links

You are here, our free e-learning automated reviewers.

- Mathematics

- Home Economics

- Physical Education

- Music and Arts

- Philippine Studies

- Language Studies

- Social Sciences

- Extracurricular

- Preschool Lessons

- Life Lessons

- AP (Social Studies)

- EsP (Values Education)

Jose Rizal’s Essays and Articles

Refer these to your siblings/children/younger friends:

HOMEPAGE of Free NAT Reviewers by OurHappySchool.com (Online e-Learning Automated Format)

HOMEPAGE of Free UPCAT & other College Entrance Exam Reviewers by OurHappySchool.com (Online e-Learning Automated Format)

Articles in Diariong Tagalog

“El Amor Patrio” (The Love of Country)

This was the first article Rizal wrote in the Spanish soil. Written in the summer of 1882, it was published in Diariong Tagalog in August. He used the pen name “Laong Laan” (ever prepared) as a byline for this article and he sent it to Marcelo H. Del Pilar for Tagalog translation.

Written during the Spanish colonization and reign over the Philippine islands, the article aimed to establish nationalism and patriotism among the natives. Rizal extended his call for the love of country to his fellow compatriots in Spain, for he believed that nationalism should be exercised anywhere a person is.

“Revista De Madrid” (Review of Madrid)

This article written by Rizal on November 29, 1882 wasunfortunatelyreturned to him because Diariong Tagalog had ceased publications for lack of funds.

Articles in La Solidaridad

“Los Agricultores Filipinos” (The Filipino Farmers)

This essay dated March 25, 1889 was the first article of Rizal published in La Solidaridad. In this writing, he depicted the deplorable conditions of the Filipino farmers in the Philippines, hence the backwardness of the country.

“A La Defensa” (To La Defensa)

This was in response to the anti-Filipino writing by Patricio de la Escosura published by La Defensa on March 30, 1889 issue. Written on April 30, 1889, Rizal’s article refuted the views of Escosura, calling the readers’ attention to the insidious influences of the friars to the country.

“Los Viajes” (Travels)

Published in the La Solidaridad on May 15, 1889, this article tackled the rewards gained by the people who are well-traveled to many places in the world.

“La Verdad Para Todos” (The Truth for All)

This was Rizal’s counter to the Spanish charges that the natives were ignorant and depraved. On May 31, 1889, it was published in the La Solidaridad.

"Vicente Barrantes’ Teatro Tagalo”

The first installment of Rizal’s “Vicente Barrantes” was published in the La Solidaridad on June 15, 1889. In this article, Rizal exposed Barrantes’ lack of knowledge on the Tagalog theatrical art.

“Defensa Del Noli”

The manuscripts of the “Defensa del Noli” was written on June 18, 1889. Rizal sent the article to Marcelo H. Del Pilar, wanting it to be published by the end of that month in the La Solidaridad.

“Verdades Nuevas”(New Facts/New Truths)

In this article dated July 31, 1889, Rizal replied to the letter of Vicente Belloc Sanchez which was published on July 4, 1889 in ‘La Patria’, a newspaper in Madrid. Rizal addressed Sanchez’s allegation that provision of reforms to the Philippines would devastate the diplomatic rule of the Catholic friars.

“Una Profanacion” (A Desecration/A Profanation)

Published on July 31, 1889, this article mockingly attacked the friars for refusing to give Christian burial to Mariano Herbosa, Rizal’s brother in law, who died of cholera in May 23, 1889. Being the husband of Lucia Rizal (Jose’s sister), Herbosa was denied of burial in the Catholic cemetery by the priests.

“Crueldad” (Cruelty),

Dated August 15, 1889, this was Rizal’s witty defense of Blumentritt from the libelous attacks of his enemies.

“Diferencias” (Differences)

Published on September 15, 1889, this article countered the biased article entitled “Old Truths” which was printed in La Patria on August 14, 1889. “Old Truths” ridiculed those Filipinos who asked for reforms.

“Inconsequencias” (Inconsequences)

The Spanish Pablo Mir Deas attacked Antonio Luna in the Barcelona newspaper “El Pueblo Soberano”. As Rizal’s defense of Luna, he wrote this article which was published on November 30, 1889.

“Llanto Y Risas” (Tears and Laughter)

Dated November 30, 1889, this article was a condemnation of the racial prejudice of the Spanish against the brown race. Rizal remembered that he earned first prize in a literary contest in 1880. He narrated nonetheless how the Spaniard and mestizo spectators stopped their applause upon noticing that the winner had a brown skin complexion.

“Filipinas Dentro De Cien Anos” (The Philippines within One Hundred Years)

This was serialized in La Solidaridad on September 30, October 31, December 15, 1889 and February 15, 1890. In the articles, Rizal estimated the future of the Philippines in the span of a hundred years and foretold the catastrophic end of Spanish rule in Asia. He ‘prophesied’ Filipinos’ revolution against Spain, winning their independence, but later the Americans would come as the new colonizer

The essay also talked about the glorious past of the Philippines, recounted the deterioration of the economy, and exposed the causes of natives’ sufferings under the cruel Spanish rule. In the essay, he cautioned the Spain as regards the imminent downfall of its domination. He awakened the minds and the hearts of the Filipinos concerning the oppression of the Spaniards and encouraged them to fight for their right.

Part of the essays reads, “History does not record in its annals any lasting domination by one people over another, of different races, of diverse usages and customs, of opposite and divergent ideas. One of the two had to yield and succumb.” The Philippines had regained its long-awaited democracy and liberty some years after Rizal’s death. This was the realization of what the hero envisioned in this essay.

Dated January 15, 1890, this article was the hero’s reply to Governor General Weyler who told the people in Calamba that they “should not allow themselves to be deceived by the vain promises of their ungrateful sons.” The statement was made as a reaction to Rizal’s project of relocating the oppressed and landless Calamba tenants to North Borneo.

“Sobre La Nueva Ortografia De La Lengua Tagala” (On The New Orthography of The Tagalog Language)

Rizal expressed here his advocacy of a new spelling in Tagalog. In this article dated April 15, 1890, he laid down the rules of the new Tagalog orthography and, with modesty and sincerity, gave the credit for the adoption of this new orthography to Dr. Trinidad H. Pardo de Tavera, author of the celebrated work “El Sanscrito en la Lengua Tagala” (Sanskrit in the Tagalog Language) published in Paris, 1884.

“I put this on record,” wrote Rizal, “so that when the history of this orthography is traced, which is already being adopted by the enlightened Tagalists, that what is Caesar’s be given to Caesar. This innovation is due solely to Dr. Pardo de Tavera’s studies on Tagalismo. I was one of its most zealous propagandists.”

“Sobre La Indolencia De Los Filipinas” (The Indolence of the Filipinos)

This logical essay is a proof of the national hero’s historical scholarship. The essay rationally countered the accusations by Spaniards that Filipinos were indolent (lazy) during the Spanish reign. It was published in La Solidaridad in five consecutive issues on July (15 and 31), August (1 and 31) and September 1, 1890.

Rizal argued that Filipinos are innately hardworking prior to the rule of the Spaniards. What brought the decrease in the productive activities of the natives was actually the Spanish colonization. Rizal explained the alleged Filipino indolence by pointing to these factors: 1) the Galleon Trade destroyed the previous links of the Philippines with other countries in Asia and the Middle East, thereby eradicating small local businesses and handicraft industries; 2) the Spanish forced labor compelled the Filipinos to work in shipyards, roads, and other public works, thus abandoning their agricultural farms and industries; 3) many Filipinos became landless and wanderers because Spain did not defend them against pirates and foreign invaders; 4) the system of education offered by the colonizers was impractical as it was mainly about repetitive prayers and had nothing to do with agricultural and industrial technology; 5) the Spaniards were a bad example as negligent officials would come in late and leave early in their offices and Spanish women were always followed by servants; 6) gambling like cockfights was established, promoted, and explicitly practiced by Spanish government officials and friars themselves especially during feast days; 7) the crooked system of religion discouraged the natives to work hard by teaching that it is easier for a poor man to enter heaven; and 8) the very high taxes were discouraging as big part of natives’ earnings would only go to the officials and friars.

Moreover, Rizal explained that Filipinos were just wise in their level of work under topical climate. He explained, “violent work is not a good thing in tropical countries as it is would be parallel to death, destruction, annihilation. Rizal concluded that natives’ supposed indolence was an end-product of the Spanish colonization.

Other Rizal’s articles which were also printed in La Solidaridad were “A La Patria” (November 15, 1889), “Sin Nobre” (Without Name) (February 28, 1890), and “Cosas de Filipinas” (Things about the Philippines) (April 30, 1890).

Historical Commentaries Written in London

This historical commentary was written by Rizal in London on December 6, 1888.

“Acerca de Tawalisi de Ibn Batuta”

This historical commentaryis believed to form part of ‘Notes’ (written incollaboration with A.B. Meyer and F. Blumentritt) on a Chinese code in the Middle Ages, translated from the German by Dr. Hirth. Written on January 7, 1889, the article was about the “Tawalisi” which refers to the northern part of Luzon or to any of the adjoining islands.

It was also in London where Rizal penned the following historical commentaries: “La Political Colonial On Filipinas” (Colonial Policy In The Philippines), “Manila En El Mes De Diciembre” (December , 1872), “Historia De La Familia Rizal De Calamba” (History Of The Rizal Family Of Calamba), and “Los Pueblos Del Archipelago Indico (The People’s Of The Indian Archipelago )

Other Writings in London

“La Vision Del Fray Rodriguez” (The Vision of Fray Rodriguez)

Jose Rizal, upon receipt of the news concerning Fray Rodriguez’ bitter attack on his novel Noli Me Tangere, wrote this defense under his pseudonym “Dimas Alang.” Published in Barcelona, it is a satire depicting a spirited dialogue between the Catholic saint Augustine and Rodriguez. Augustine, in the fiction, told Rodriguez that he (Augustine) was commissioned by God to tell him (Rodriguez) of his stupidity and his penance on earth that he (Rodriguez) shall continue to write more stupidity so that all men may laugh at him. In this pamphlet, Rizal demonstrated his profound knowledge in religion and his biting satire.

“To The Young Women of Malolos”

Originally written in Tagalog, this famous essay directly addressed to the women of Malolos, Bulacan was written by Rizal as a response to Marcelo H. Del Pilar’s request.

Rizal was greatly impressed by the bravery of the 20 young women of Malolos who planned to establish a school where they could learn Spanish despite the opposition of Felipe Garcia, Spanish parish priest of Malolos. The letter expressed Rizal’s yearning that women be granted the same chances given to men in terms of education. In the olden days, young women were not educated because of the principle that they will soon be wives and their primary career would be to take care of the home and children. Rizal however advocated women’s right to education.

Below are some of the points mentioned by Rizal in his letter to the young women of Malolos: 1) The priests in the country that time did not embody the true spirit of Christianity; 2) Private judgment should be used; 3) Mothers should be an epitome of an ideal woman who teaches her children to love God, country, and fellowmen; 4) Mothers should rear children in the service of the state and set standards of behavior for men around her;5) Filipino women must be noble, decent, and dignified and they should be submissive, tender, and loving to their respective husband; and 6) Young women must edify themselves, live the real Christian way with good morals and manners, and should be intelligent in their choice of a lifetime partner.

Writings in Hong Kong

“Ang Mga Karapatan Ng Tao” (The Rights Of Man)

This was Rizal’s Tagalog translation of “The Rights of Man” which was proclaimed by the French Revolution in 1789.

“A La Nacion Espanola”(To The Spanish Nation)

Written in 1891, this was Rizal’s appeal to Spain to rectify the wrongs which the Spanish government and clergy had done to the Calamba tenants.

“Sa Mga Kababayan” (To My Countrymen)

This writing written in December 1891 explained the Calamba agrarian situation .

“Una Visita A La Victoria Gaol” (A Visit To Victoria Gaol), March 2, 1892

On March 2, 1892,Rizal wrote this account of his visit to the colonial prison of Hong Kong. He contrasted in the article the harsh Spanish prison system with the modern and more humane British prison system.

“Colonisation Du British North Borneo, Par De Familles De Iles Philippines” (Colonization Of British North Borneo By Families From The Philippine Islands)

This was Rizal’s elucidation of his pet North Borneo colonization project.

“Proyecto De Colonization Del British North Borneo Por Los Filipinos” (Project Of The Colonization Of British North Borneo By The Filipinos)

In this writing, Rizal further discussed the ideas he presented in “Colonization of British North Borneo by Families from the Philippine Islands.”

“La Mano Roja” (The Red Hand)

This was a writing printed in sheet form. Written in Hong Kong, the article denounced the frequent outbreaks of fires in Manila.

“Constitution of The La Liga Filipina”

This was deemed the most important writing Rizal had made during his Hong Kong stay. Though it was Jose Ma. Basa who conceived the establishment of Liga Filipina (Philippine League), his friend and namesake Jose Rizal was the one who wrote its constitution and founded it.

Articles for Trubner’s Record

Due to the request of Rizal’s friend Dr. Reinhold Rost, the editor of Trubner’s Record (a journal devoted to Asian Studies), Rizal submitted two articles:

Specimens of Tagal Folklore

Published in May 1889, the article contained Filipino proverbs and puzzles.

Two Eastern Fables (June 1889)

It was a comparative study of the Japanese and Philippine folklore. In this essay, Jose Rizal compared the Filipino fable, “The Tortoise and the Monkey” to the Japanese fable “Saru Kani Kassen” (Battle of the Monkey and the Crab).

Citing many similarities in form and content, Rizal surmised that these two fables may have had the same roots in Malay folklore. This scholarly work received serious attention from other ethnologists, and became a topic at an ethnological conference.

Among other things, Rizal noticed that both versions of the fable tackled about morality as both involve the eternal battle between the weak and the powerful. The Filipino version however had more philosophy and plainness of form whereas the Japanese counterpart had more civilization and diplomacy.

Other Writings

“Pensamientos De Un Filipino” (Reflections of A Filipino)

Jose Rizal wrote this in Madrid, Spain from 1883-1885. It spoke of a liberal minded and anti-friar Filipino who bears penalties such as an exile.

“Por Telefono”

This was a witty satire authored by “Dimas Alang” (one of the hero’s pen names) ridiculing the Catholic monk Font, one of the priests who masterminded the banning of the “Noli”. Published in booklet form in Barcelona, Spain, it narrated in a funny way the telephone conversation between Font and the provincial friar of the San Agustin Convent in Manila.

This pamphlet showed not only Rizal’s cleverness but also his futuristic vision. Amazingly, Rizal had envisaged that overseas telephonic conversations could be carried on—something which was not yet done during that time (Fall of 1889). It was only in 1901, twelve years after Rizal wrote the “Por Telefono,” when the first radio-telegraph signals were received by Marconi across the Atlantic.

“La Instruccion” (The Town Schools In The Philippines)

Using his penname “Laong Laan”, Rizal assessed in this essay the elementary educational system in the Philippines during his time. Having observed the educational systems in Europe, Rizal found the Spanish-administered education in his country poor and futile. The hero thus proposed reforms and suggeted a more significant and engaging system.

Rizal for instance pointed out that there was a problem in the mandated medium of instruction—the colonizers’ language (Spanish) which was not perfectly understood by the natives. Rizal thus favored Philippine languages for workbooks and instructions.

The visionary (if not prophetic) thinking of Rizal might have been working (again) when he wrote the essay. Interestingly, his call for educational reforms, especially his stand on the use of the local languages for instruction, is part of the battle cry and features of today’s K to 12 program in the Philippines ... continue reading (© 2013 by Jensen DG. Mañebog )

Jensen DG. Mañebog , the contributor, is a book author and professorial lecturer in the graduate school of a state university in Metro Manila. His unique textbooks and e-books on Rizal (available online) comprehensively tackle, among others, the respective life of Rizal’s parents, siblings, co-heroes, and girlfriends. (e-mail: [email protected] )

Tag: Jose Rizal’s Essays and Articles

For STUDENTS' ASSIGNMENT, use the COMMENT SECTION here: Bonifacio Sends Valenzuela to Rizal in Dapitan

Ourhappyschool recommends.

Select Chapter:

The philippines:a century hence.

Rizal’s “Filipinas Dentro De Cien Años”

Rizal’s “Filipinas Dentro De Cien Años” (translated as “The Philippines within One Hundred Years” or “The Philippines A Century Hence”) is an essay meant to forecast the future of the country within a hundred years. This essay, published in La Solidaridad of Madrid, reflected Rizal’s sentiments about the glorious past of the Philippines, the deterioration of the Philippine economy, and exposed the foundations of the native Filipinos’ sufferings under the cruel Spanish rule. More importantly, Rizal, in the essay, warned Spain as regards the catastrophic end of its domination – a reminder that it was time that Spain realizes that the circumstances that contributed to the French Revolution could have a powerful effect for her on the Philippine islands. Part of the purpose in writing the essay was to promote a sense of nationalism among the Filipinos – to awaken their minds and hearts so they would fight for their rights.

La Solidaridad, the newspaper which serialized Rizal’s Filipinas Dentro De Cien Años

Causes of miseries, 1. spain’s implementation of her military laws.

Because of such policies, the Philippine population decreased significantly. Poverty became more widespread, and f armlands were left to wither. The family as a unit of society was neglected, and overall, every aspect of the life of the Filipino was retarded.

2. Deterioration and disappearance of Filipino indigenous culture

When Spain came with the sword and the cross, it began the gradual destruction of the native Philippine culture. Because of this, the Filipinos started losing confidence in their past and their heritage, became doubtful of their present lifestyle, and eventually lost hope in the future and the preservation of their race. The natives began forgetting who they were – their valued beliefs, religion, songs, poetry, and other forms of customs and traditions.

3. Passivity and submissiveness to the Spanish colonizers

One of the most powerful forces that influenced a culture of silence among the natives were the Spanish friars. Because of the use of force and intimidation, unfairly using God’s name, the Filipinos learned to submit themselves to the will of the foreigners.

Rizal's Forecast

What will become of the Philippines within a century? Will they continue to be a Spanish Colony? Spain was able to colonize the Philippines for 300 years because the Filipinos remained faithful during this time, giving up their liberty and independence, sometimes stunned by the attractive promises or by the friendship offered by the noble and generous people of Spain. Initially, the Filipinos see them as protectors but sooner, they realize that they are exploiters and executers. So if this state of affair continues, what will become of the Philippines within a century? One, the people will start to awaken and if the government of Spain does not change its acts, a revolution will occur. But what exactly is it that the Filipino people like? 1) A Filipino representative in the Spanish Cortes and freedom of expression to cry out against all the abuses; and 2) To practice their human rights. If these happen, the Philippines will remain a colony of Spain, but with more laws and greater liberty. Similarly, the Filipinos will declare themselves ’independent’. Note that Rizal only wanted liberty from Spaniards and not total separation. In his essay, Rizal urges to put freedom in our land through peaceful negotiations with the Spanish Government in Spain. Rizal was confident as he envisioned the awakening of the hearts and opening of the minds of the Filipino people regarding their plight. He ‘prophesied’ that the Philippines will be successful in its revolution against Spain, winning their independence sooner or later. Though lacking in weapons and combat skills, the natives waged war against the colonizers and in 1898, the Americans wrestled with Spain to win the Philippines. Years after Rizal’s death, the Philippines attained its long-awaited freedom — a completion of what he had written in the essay, does not record in its archives any lasting domination by one people over another of different races, of diverse usages and customs, of opposite and divergent ideas. One of the two had to yield and succumb.” Indeed, the essay, The Philippines a Century Hence is as relevant today as it was when it was written over a century ago. Alongside Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, Rizal shares why we must focus on strengthening the most important backbone of the country – our values, mindsets, and all the beliefs that had shaped our sense of national identity. Additionally, the essay serves as a reminder that we, Filipinos, are historically persevering and strong-minded. The lessons learned from those years of colonization were that all those efforts to keep people uneducated and impoverished, had failed. Nationalism eventually thrived and many of the predictions of Rizal came true. The country became independent after three centuries of abusive Spanish rule and five decades under the Americans.

SOBRE LA INDOLENCIA DE LOS FILIPINOS (The Indolence of the Filipinos)

This is said to be the longest essay written by Rizal, which was published in five installments in the La Solidaridad, from July 15 to September 15, 1890. The essay was described as a defense against the Spaniards who charged that the Filipinos are inherently lazy or indolent. The Indolence of the Filipinos is said to be a study of the causes why the people did not, as was said, work hard during the Spanish regime. Rizal pointed out that long before the coming of the Spaniards, the Filipinos were industrious and hardworking. The Spanish reign brought about a decline in economic activities because of the following causes: First, the establishment of the Galleon Trade cut-off all previous associations of the Philippines with other countries in Asia and the Middle East. As a result, business was only conducted with Spain through Mexico. Because of this, the small businesses and handicraft industries that flourished during the pre-Spanish period gradually disappeared. Second, Spain also extinguished the natives’ love of work because of the implementation of forced labor. Because of the wars between Spain and other countries in Europe as well as the Muslims in Mindanao, the Filipinos were compelled to work in shipyards, roads, and other public works, abandoning agriculture, industry, and commerce. Third, Spain did not protect the people against foreign invaders and pirates. With no arms to defend themselves, the natives were killed, their houses burned, and their lands destroyed. As a result of this, the Filipinos were forced to become nomads, lost interest in cultivating their lands or in rebuilding the industries that were shut down, and simply became submissive to the mercy of God. Fourth, there was a crooked system of education, if it was to be considered an education. What was being taught in the schools were repetitive prayers and other things that could not be used by the students to lead the country to progress. There were no courses in Agriculture, Industry, etc., which were badly needed by the Philippines during those times. Fifth, the Spanish rulers were a bad example to despise manual labor. The officials reported to work at noon and left early, all the while doing nothing in line with their duties. The women were seen constantly followed by servants who dressed them and fanned them – personal things which they ought to have done for themselves. Sixth, gambling was established and widely propagated during those times. Almost everyday there were cockfights, and during feast days, the government officials and friars were the first to engage in all sorts of bets and gambles. Seventh, there was a crooked system of religion. The friars taught the naïve Filipinos that it was easier for a poor man to enter heaven, and so they preferred not to work and remain poor so that they could easily enter heaven after they died. Lastly, the taxes were extremely high, so much so that a huge portion of what they earned went to the government or to the friars. When the object of their labor was removed and they were exploited, they were reduced to inaction. Rizal admitted that the Filipinos did not work so hard because they were wise enough to adjust themselves to the warm, tropical climate. “An hour’s work under that burning sun, in the midst of pernicious influences springing from nature in activity, is equal to a day’s labor in a temperate climate.” He explained, “violent work is not a good thing in tropical countries as it would be parallel to death, destruction, annihilation.” It can clearly be deduced from the writing that the cause of the indolence attributed to our race is Spain: When the Filipinos wanted to study and learn, there were no schools, and if there were any, they lacked sufficient resources and did not present more useful knowledge; when the Filipinos wanted to establish their businesses, there was not enough capital nor protection from the government; when the Filipinos tried to cultivate their lands and establish various industries, they were made to pay enormous taxes and were exploited by the foreign rulers.

LETTER TO THE YOUNG WOMEN OF MALOLOS

Jose Rizal’s legacy to Filipino women is embodied in his famous essay entitled, “To the Young Women of Malolos,” where he addresses all kinds of women – mothers, wives, the unmarried, etc. and expresses everything that he wishes them to keep in mind. On December 12, 1888, a group of 20 women of Malolos petitioned Governor-General Weyler for permission to open a night school so that they may study Spanish under Teodor Sandiko. Fr. Felipe Garcia, a Spanish parish priest in Malolos objected. But the young women courageously sustained their agitation for the establishment of the school. They then presented a petition to Governor Weyler asking that they should be allowed to open a night school (Capino et al, 1977). In the end, their request was granted on the condition that Señorita Guadalupe Reyes should be their teacher. Praising these young women for their bravery, Marcelo H. del Pilar requested Rizal to write a letter commending them for their extraordinary courage. Originally written in Tagalog, Rizal composed this letter on February 22, 1889 when he was in London, in response to the request of del Pilar. We know for a fact that in the past, young women were uneducated because of the principle that they would soon be wives and their primary career is to take care of the home and their children. In this letter, Rizal yearns that women should be granted the same opportunities given to men in terms of education. The salient points contained in this letter are as follows: 1. The rejection of the spiritual authority of the friars – not all of the priests in the country that time embodied the true spirit of Christ and His Church. Most of them were corrupted by worldly desires and used worldly methods to effect change and force discipline among the people. 2. The defense of private judgment 3. Qualities Filipino mothers need to possess – as evidenced by this portion of his letter, Rizal is greatly concerned of the welfare of the Filipino children and the homes they grow up in. 4. Duties and responsibilities of Filipino mothers to their children 5. Duties and responsibilities of a wife to her husband - Rizal states in this portion of his letter how Filipino women ought to be as wives, in order to preserve the identity of the race. 6. Counsel to young women on their choice of a lifetime partner

QUALITIES MOTHERS HAVE TO POSSESS

Rizal enumerates the qualities Filipino mothers have to possess: 1. Be a noble wife - that women must be decent and dignified, submissive, tender and loving to their respective husband. 2. Rear her children in the service of the state – here Rizal gives reference to the women of Sparta who embody this quality. Mothers should teach their children to love God, country and fellowmen. 3. Set standards of behavior for men around her - three things that a wife must instill in the mind of her husband: activity and industry; noble behavior; and worthy sentiments. In as much as the wife is the partner of her husband’s heart and misfortune, Rizal stressed on the following advices to a married woman: aid her husband, share his perils, refrain from causing him worry; and sweeten his moments of affliction.

RIZAL’S ADVICE TO UNMARRIED MEN AND WOMEN

Jose Rizal points out to unmarried women that they should not be easily taken by appearances and looks, because these can be very deceiving. Instead, they should take heed of men’s firmness of character and lofty ideas. Rizal further adds that there are three things that a young woman must look for a man she intends to be her husband: 1. A noble and honored name 2. A manly heart 3. A high spirit incapable of being satisfied with engendering slaves.

In summary, Rizal’s letter “To the Young Women of Malolos,” centers around five major points (Zaide &Zaide, 1999): 1. Filipino mothers should teach their children love of God, country and fellowmen. 2. Filipino mothers should be glad and honored, like Spartan mothers, to offer their sons in defense of their country. 4. Filipino women should educate themselves aside from retaining their good racial values. 5. Faith is not merely reciting prayers and wearing religious pictures. It is living the real Christian way with good morals and manners.

Jose Rizal Biography Essay : The Philippine National Hero

Jose Rizal, born on June 19, 1861, in Calamba, Philippines, is widely regarded as the national hero of the Filipino people. His life and works played a crucial role in shaping the country’s struggle for independence from Spanish colonial rule. This essay delves into the extraordinary life of Jose Rizal, highlighting his significant contributions as a writer, reformist, and patriot.

Jose Rizal: The Philippine National Hero

Credit image Wikipedia

Essay on Early Life and Education

Rizal hailed from a middle-class family and received an excellent education. He studied in Manila and later pursued higher education in Europe, where he honed his intellectual and artistic talents. Rizal’s exposure to European ideals and his experiences abroad influenced his later writings and fueled his passion for social reform.

Literary and Artistic Achievements:

Rizal was a gifted writer and artist, leaving behind an extensive body of work. His novels, including “Noli Me Tangere” and “El Filibusterismo,” exposed the injustices and abuses suffered by the Filipino people under Spanish rule. Through his writings, Rizal sought to awaken national consciousness and inspire his fellow countrymen to fight for their rights and freedom.

Social and Political Activism:

Driven by a strong sense of justice and patriotism, Rizal actively participated in various reform movements. He advocated for equal rights, education, and fair treatment of Filipinos. Rizal’s peaceful approach to social change emphasized education, enlightenment, and the power of intellectual discourse. He co-founded the Liga Filipina, a civic organization that aimed to unite Filipinos and work towards political and social reforms.

Impact and Martyrdom: Rizal’s ideas and writings resonated deeply with the Filipino people, inspiring a wave of nationalism and resistance against Spanish oppression. Unfortunately, his relentless pursuit of reform led to his arrest and subsequent execution on December 30, 1896. Rizal’s martyrdom transformed him into a symbol of courage, sacrifice, and national identity, galvanizing the Filipino revolutionaries in their quest for independence.

Legacy : Despite his untimely death, Rizal’s legacy endures. He remains a revered figure in Philippine history, celebrated for his intellectual prowess, moral integrity, and unwavering commitment to his country. Rizal’s influence extends beyond his own time, continuing to inspire generations of Filipinos in their pursuit of justice, freedom, and a brighter future.

Conclusion: Jose Rizal’s life and works exemplify the indomitable spirit of the Filipino people in their fight against colonial oppression. Through his writings and activism, Rizal left an indelible mark on the Philippines, serving as a beacon of hope and a catalyst for change. His legacy reminds us of the power of ideas, the importance of education, and the enduring pursuit of justice. Jose Rizal truly deserves the title of the Filipino National Hero .

Easy Writing

Essay writing, subscribe to get the new updates, related articles.

Andrew Tate: Biography -How to Become a Top G

Who is Founder Facebook Mark Zuckerberg Life History

Barack Obama: The First African-American President of the United States

Michael Madhusudan Dutta About Life History Easy

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

A Reflection Paper about The Philippines a Century Hence by Jose Rizal

Rizal paints a chilling portrait of his homeland's potential future under continued Spanish rule. He envisions a Philippines choked by oppression, where Filipinos are stripped of their identity and exploited to enrich the motherland. Education is stifled, industry stagnates, and social injustices run rampant. If Spain embraced reform, granting Filipinos representation, equal rights, and access to education, they might assimilate the archipelago into a unified Spanish nation. This, Rizal warns, would come at the cost of cultural annihilation and complete subordination. On the other hand, if Spain continues its oppressive policies, Rizal predicts a violent uprising, fueled by Filipino resentment and yearning for freedom. This path, though bloody, could lead to independence and the birth of a truly sovereign nation.

Related Papers

Angel O . Untal IV

The Philippines: A Century hence was written by Jose Rizal and was published in La Solaridad, a newspaper run by Filipino Illustrados in Spain. This essay was made to supplement his works, especially his two famous works “Noli Me Tangere” and El Filibusterismo” as his works made confusion on what it wants to entail to its readers. Because the readers of his works interpreted it as a means to spread the message of revolution but he do not condone violence and all he wanted is reformation and assimilation to what he called “the mother country” Spain. His work was heavily influenced by the enlightenment ideology spreading in Europe during his time and by the book of Feodor Jagor. His essay talks about the past what was the Philippines like before and the present time (during his time) and used it as a basis to form a hypothesis on what will happen to the Philippines in the future, hence it is not a random prediction. And what he told was did really happen in the Philippines later. His essay contains the miseries Filipinos experienced during the three decades of the Spanish regime, the reasons why the Filipinos awakened their nationalism, how the Spaniards keep the Filipino indolent and submissive, why Spain could not stop the liberal ideologies emergence in the Philippines, how it can lead to revolution, how to prevent the revolution and it is through reformation, what will happen if the Philippines becomes separated to Spain like how can the country keep its liberty from other foreign invaders, and who among the foreign invaders will colonize the Philippines. He forecasted that after many a century, the Philippines will be in the hands of new foreign masters.

Christine Jane Zarsadias

Janelle Giann Depio

Rethink how Rizal almost begged for reforms within the Spanish colonial setup through this paper and predicted correctly that the Americans would invade the country if Spain refuses to institute reform. Write a 3-page reaction paper. Rizal Begging for Reforms within the Spanish Colonial Setup In the intelligent piece "Filipinas dentro de Cien Años," Jose Rizal, via his predictive writing instrument, nearly screamed for reforms within the Spanish colonial system and intelligently predicted the coming American invasion should Spain not listen to the pleas for change. As I read over Rizal's remarks,

Justine jannah Taguibao

Rethink how Rizal almost begged for reforms within the Spanish colonial setup through this paper and predicted correctly that the Americans would invade the country if Spain refuses to institute reform. (The Philippine a Century Hence by Dr. Jose Rizal)

Rocel Erica Calma

Rethink how Rizal almost begged for reforms within the Spanish colonial setup through this paper and predicted correctly that the Americans would invade the country if Spain refuses to institute reform. Upon perusing Rizal's "The Philippines A Century Hence" via firsthand experience, I am impressed by the insightful and insightful conclusions he made regarding the future of his native land. Written more than a century ago, Rizal's insight is remarkably precise and thought-provoking.

Trisha Mae Abainza

"The Philippines, A Century Hence" by Jose Rizal is a seminal work that serves as a poignant reflection on the socio-political landscape of the Philippines during the late 19th century. Written in 1889, Rizal's essay is a prescient analysis that not only calls for internal reforms within the Spanish colonial system but remarkably predicts the eventual American intervention if Spain fails to address the grievances of its Filipino subjects. This literary masterpiece provides a profound glimpse into Rizal's visionary thinking and offers valuable insights into the historical trajectory of the Philippines as it navigates the challenges of colonization and the quest for national identity.

Niña Angeline Infante

Activity No.5: Buhay at Mga Sinulat ni Rizal Rethink how Rizal almost begged for reforms within the Spanish colonial setup through this paper and predicted correctly that the Americans would invade the country if Spain refuses to institute reform.

Althea Hannah D . Deloso

In his sociopolitical essay "The Philippines a Century Hence," Dr. Jose Rizal talked about the Filipino people's suffering during the Spanish colonization and how the Philippines would become in the next century.

Cefren Pao Bubos

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

José Rizal (born June 19, 1861, Calamba, Philippines—died December 30, 1896, Manila) patriot, physician, and man of letters who was an inspiration to the Philippine nationalist movement. The son of a prosperous landowner, Rizal was educated in Manila and at the University of Madrid. A brilliant medical student, he soon committed himself to ...

Rizal took first the entrance examination at the Colegio de San Juan de Letran on June 10, 1872. His brother, Paciano, accompanied him when he took the exam. The exams for incoming freshmen in the different colleges for boys were administered or held at the Colegio de San Juan de Letran since the Dominicans exer-cised the power of inspection and regula-tion over Ateneo that time.

José Protasio Rizal Mercado y Alonso Realonda (Spanish: [xoˈse riˈsal,-ˈθal], Tagalog: [hoˈse ɾiˈsal]; June 19, 1861 - December 30, 1896) was a Filipino nationalist, writer and polymath active at the end of the Spanish colonial period of the Philippines.He is considered a national hero (pambansang bayani) of the Philippines. An ophthalmologist by profession, Rizal became a writer and ...

Name: Jose Rizal. Birth Year: 1861. Birth date: June 19, 1861. Birth City: Calamba, Laguna Province. Birth Country: Philippines. Gender: Male. Best Known For: José Rizal called for peaceful ...

Rizal's Education. Jose Rizal's first teacher was his mother, who had taught him how to read and pray and who had encouraged him to write poetry. Later, private tutors taught the young Rizal Spanish and Latin, before he was sent to a private school in Biñan. When he was 11 years old, Rizal entered the Ateneo Municipal de Manila.

Jose Rizal was a patriot, physician, and man of letters whose life and literary works were an inspiration to the Philippine nationalist movement. Dr. Jose Protacio Rizal was born in the town of Calamba, Laguna, on June 19, 1861. He was the second son, and the seventh among eleven children, of Francisco Mercado and Teodora Alonso.

Even at a young age, as a youth himself, Rizal saw that an education was key to creating a class of Filipinos that could lead the country to freedom and self-determination. Education was thus key to knowing oneself. Shakespeare's famous adage from Hamlet, "To thyself be true," rings true.

Jose Rizal, a name synonymous with Filipino nationalism and intellectual prowess, holds a revered place in the annals of Philippine history. His life and works have left an indelible mark on the nation's identity and struggle for independence. In this essay, I will share my perspective on the life and works of Jose Rizal, a man whose influence ...

Rizal had his early education in Calamba and Biñan. It was a typical schooling that a son of an ilustrado family received during his time, characterized by the four R's- reading, writing, arithmetic, and religion. Instruction was rigid and strict. Knowledge was forced into the minds of the pupils by means of the tedious memory method aided ...

Education was a priority for the Mercado family and young Jose Protacio was sent to find out from Justiniano Aquino Cruz, a teacher from nearby Binan, Laguna. But the education of alittle town and an educator failed to sufficiently quench the young man's thirst for knowledge and. Download Free PDF. View PDF.

Guerrero's "The First Filipino" delves into the life, struggles, and enduring legacy of Jose Rizal, the national hero of the Philippines. This comprehensive critical paper, exceeding 2500 words, meticulously unravels Rizal's journey from an elite reformist to a fervent nationalist. Guerrero's narrative navigates through Rizal's formative years ...

The essay rationally countered the accusations by Spaniards that Filipinos were indolent (lazy) during the Spanish reign. It was published in La Solidaridad in five consecutive issues on July (15 and 31), August (1 and 31) and September 1, 1890. Rizal argued that Filipinos are innately hardworking prior to the rule of the Spaniards.

Rizal's "Filipinas Dentro De Cien Años" (translated as "The Philippines within One Hundred Years" or "The Philippines A Century Hence") is an essay meant to forecast the future of the country within a hundred years. This essay, published in La Solidaridad of Madrid, reflected Rizal's sentiments about the glorious past of the ...

Get your custom essay on. Knowing this made me realize that even the brightest mind needs perseverance in order to be successful. Rizal is a great example for the youth. His love for learning is beyond what we imagined. Rizal shows us that knowing is not enough. Learning is a never ending process.

Have a Clear Structure. Write an introduction of Rizal's childhood years that influenced his later life. You can also organize the series of events in Rizal's life in chronological order to have a clear transition and structure for the readers to follow. Lastly, write a conclusion of how the experience has molded Rizal to be a hero.

Polytechnic University of the Philippines A.Y. 2022-2023 Analyzing Jose Rizal's 'Letter to the Women of Malolos': Empowerment, Education, and Women's Roles in Society In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Course GEED 10013 Buhay at Mga Sinulat ni Rizal by Aaron A. Santillan BSCS4-1N June 30, 2023 During the era of Spanish colonization, demanding education for women in the ...

This essay is about the life and actions of Jose Rizal as he was an influential person for Filipino society. Jose Rizal is a prominent figure in the history of the Philippines and is widely considered as the national hero of the country. Born on June 19, 1861, in Calamba, Laguna, Philippines, he was a polymath, a physician, a novelist, a poet ...

Jose Rizal, born on June 19, 1861, in Calamba, Philippines, is widely regarded as the national hero of the Filipino people. His life and works played a crucial role in shaping the country's struggle for independence from Spanish colonial rule. ... Essay on Early Life and Education. Rizal hailed from a middle-class family and received an ...

Download. Essay, Pages 4 (751 words) Views. 9620. Family and Early life He was the seventh child in a family of 11 children (2 boys and 9 girls). His parents went to school and were well known. His father, Francisco Rizal Mercado, worked hard as a farmer in Binan, Laguna. Rizal looked up to him.

This is a summary and reflection paper covering Rizal's life and works. The biography "The First Filipino" by Leon Maria Guerrero was used as a reference and approach into the research on Rizal's life and works, focusing solely on the personal details of the national hero. It will cover Rizal's life from childhood up until his death as a ...

essay about Jose Rizal: Jose Rizal was a Filipino physician, writer, and national hero of the Philippines. He is considered one of the greatest geniuses of the Philippines and is known for his novels, essays, and poems that exposed the ills of Spanish colonial rule and inspired the Philippine revolution.

Jose Rizal José Protasio Rizal Mercado y Alonso Realonda) is a national hero of the Philippines. In the country, he is sometimes called the "pride of the Malayan race". He was born on June 19, 1861 in the town of Calamba, Laguna. He was the seventh child in a family of 11 children (2 boys and 9 girls).

The Philippines: A Century hence was written by Jose Rizal and was published in La Solaridad, a newspaper run by Filipino Illustrados in Spain. This essay was made to supplement his works, especially his two famous works "Noli Me Tangere" and El Filibusterismo" as his works made confusion on what it wants to entail to its readers.