- Privacy policy

- Terms and conditions

Essay on democracy in Nepal in 250 words.

DEMOCRACY IN NEPAL

Rana rule was a family autocracy. It existed in Nepal for 104 years. It did not give place to people’s will and aspiration. So people fought against ranas for rights and freedom. Nepal got democracy in 2007 B.S. we celebrate falgun as democracy day every year. People could not strengthen the democracy they got in 2007. So they again had to fight for it in 2046 and 2062/ 063. The last movement succeeded to bring a remarkable change in the country. We had kingship for nearly 240 years in our history. This movement made it a republic state. Now we have been the citizen of a federal secular state.

However, we have to do a lot to make the democracy stronger. First and foremost need is political stability through elected government. Our constituent assembly should formulate new constitution addressing the will and aspiration of all people representing all cast and creed. Only then everyone can get equal opportunity for their personality development.

Loktantra is the spirit of the people’s movement. It grants citizens various kind of freedom such as freedom of expression, freedom of religion, freedom of movement, freedom to form association, etc. It ensures equality. Loktantra is based on public opinion. The government in a democratic country like Nepal is expected to work according to people’s will and aspiration. No disparity is made on the plea of race, caste, religion and sex. Democracy encourages patriotism and nationality.

Despite these good aspects, it is said to have some demerits. Some people say that is based on hollow idealism. The majority suppresses the minority. Rich persons win elections only. Above all, there are partisan evils and lowers are misused.

In spite of the aforementioned weakness, democracy is the best government. No other forms of government can take its place. It is our duty to make our loktantra strong and provide ensure the rights and freedom of the people.

Posted by Nepticle Blog

You may like these posts, post a comment, popular posts.

Essay on Social evils in Nepal-2021

SOCIAL EVILS …

essay on environmental pollution in 250 words-Nepal-2022

ENVIRONMENTAL POLLUTION Environment simply…

Importance of Newspapers | Essay | 2021

IMPORTANCE OF NEWSPAPER There are different me…

- Book articles

- environmentalpollution

- formationofFossil

- human brain

- importance of agriculture

- pleasure of reading

- Rights and duties

- rivers in nepal

- student life

Featured post

Structures and Function of brain

Hello Everyone! Welcome to my blog. Here you can find any articles related to General knowledge, creative stories, articles on different subjects, Essay writting, photography and so on.

- anti-social practices (1)

- Articles (24)

- Be positive (1)

- Book articles (1)

- children day special (1)

- conscious mind (1)

- creativity (1)

- cyber law (1)

- Democracy (1)

- dowry system (1)

- drug addiction (1)

- Education (1)

- environmentalpollution (1)

- excursion (1)

- Forest in Nepal (1)

- formationofFossil (1)

- health is wealth (1)

- history (1)

- history of earth (1)

- human brain (1)

- importance of agriculture (1)

- internet (1)

- multimedia (1)

- newspapers (1)

- patriotism (1)

- pleasure of reading (1)

- quiz time (1)

- Rights and duties (1)

- rivers in nepal (1)

- social service (1)

- student life (1)

- student mind (1)

- subconscious in plants (1)

- tourism industry (1)

- unix and linux (1)

- value of science (1)

Most Popular

DEMOCRACY IN NEPAL Democracy is a …

.png)

Essay on Student life in 250 words

STUDENT LIFE The period of a human life spent at school or college for …

Essay on rights and duties in 250+ words

RIGHTS AND DU…

HUMAN BRAIN Brain There are vario…

Essay on importance of women education in Nepal in 300 words

IMPORTANCE OF WOMEN EDUCATION IN NEPAL WHAT IS EDUCATION? Education …

Essay on 'Tourism in Nepal' in 250 words

TOURISM IN NEPAL We want to visi…

essay on science and human values in 300 words

THE VALUE OF SCIENCE The present of era is t…

Essay on pleasures of reading | School Essay | College Essay-2021

PLEASURES OF READING …

Social Widget

- Contract Publishing

- Submissions

- Advertise With Us

- Testimonials

- Latin America and the Caribbean

- Indo Pacific

- Middle East

- Climate & Environment

- Defence & Security

- Development Partnerships

- Agriculture

- Politics & Government

- Science & Technology

- Special Reports

- Soft Diplomacy

Nepal: Contemporary Democratic Politics

Nepal’s democracy has made a distinctive identity of the Nepali version. Nepal has witnessed the experience of the second episode of democracy in the constitutional monarchy set-up from 1990 to 2007. Nepalis today are experiencing the first chapter of inclusive democracy in the infant republic declared in 2015. The result of seven decades of political trials since 1950 is not a new political issue for contemporary Nepalis. The preamble mentioned in the Seventh Constitution of Nepal 2015, the result of the ongoing political struggle, has clearly and accurately defined the past, present and future of Nepali politics in a terse chronicle. Democracy in Nepal has become achievable for the violent protests as a means of Nepali politics and the peaceful disobedience of the populist forces.

The story of politics, the consequences of pain and expectation in politics, whether or not we like it, we have no choice but to walk in the vicinity and sync of time and situation. These activities are interdependent in such political and social movements, creating many upheavals in public affairs. We can sum the political vibrations caused in the political repercussions in the political system as neither performance-oriented nor deliver solutions-based actions within the democratic templates even if there are politico-administrative praxis. The primary temporal challenge is seen on the surface. The primary reasons are the lack of strengthening of the foundations of parliamentary democracy, and the delay in the process of democratization of democracy by managing short, medium and long term political transitions.

In the present’s grammar of the Government of Nepal, maintaining a full or collective or comprehensive democracy is an inseparable concern of all. There are three areas of specialization in politics – government and state (polity), private sector (economy) and civil society (political society). The fourth pillar of political communication (media) is the positive activism of political parties and the promotion of the infrastructures of emerging politics. The role of this fourth pillar in promoting political education, political socialization and political advancement is crucial in the 21st century.

Nepali democracy is strengthened by maintaining the balance and control of the interrelationships between the three interdependent and interconnected sectors, including political proactiveness and political semantics, political-economic perspectives and practices, and the conduct of public administration. Ideological diversity and intersectional pluralism pervade political society. Efficient leadership helps bridge the gap between political thinking and performance-oriented delivery of the rhetorics. The practice of pragmatic political mastery and politico-administrative professionalism was not limited to the politics experienced in the Western political society. The time has come for Nepal not to be an exception. The above three bases of governance – thinking of political action, implementation of political ideas and adoption of public professionalism – are also the seeds of social transformation in Nepal. In political aspirations, leadership style and its culture naturally determine the intensity and extensity of political will.

In terms of economic thinking, the challenge is not only to imprison Nepal’s poor economy in the vision of prosperity or its kept tall promises. But also to turn it into realization is no less a daunting challenge. In order to achieve the goal of good governance and sustainable development of Nepal, the current cycle of coronavirus pandemic, the conflict-ridden legacy of the Nepali political economy, and the signs of negative economic growth are further disrupted and stunted. There should be full implementation of public policy in public affairs, whether they are annual policies and programs, fiscal and monetary policies.

It is equally important whether the three core public policies are backed and followed down and up in the strata of bureaucracy, government and governance in Nepal. It is essential that the basic national policy address current and future challenges. Apart from maintaining security, peace and tranquillity, the administration is not impervious to facilitate the state of flux of the state and society and to act as a catalyst for change. Politics should also be sensitive to public management bodies. Therefore, public opinion and political aspirations towards the state and the government assist bonafide citizens and assuage the public to convey positive sentiments.

Public intellectual circles have their own fundamental traditions and new political consciousness on behalf of civil society. Its concept of rational cooperation and coexistence will become more and more universally accepted. In this matter of importance, if the political parties involved in it adopt the ideological practice of mutual rationale of existentialism, in addition to a conventional and agitation role of a vigilant civic society. Civil society is circumscribed into the role of social opposition in Nepal. It can also be analyzed that the use and practice of political theory in Nepal have been misappropriated, abused or deviated if otherwise. These basic and general political problems have eroded internal and external sovereignty creating its thin layer of supreme authority in the design of popular sovereignty. Weaknesses in sovereignty have certainly not diminished some of the hopes in politics that will be resolved over time.

The first chapter of the Republic of Nepal will come to an end if the power struggles in the culture of the political leadership and tensions or anxiety continue in the incumbent leadership. The presidential system of the Executive Rule is not unlikely to be the beginning of the second chapter of the Republic of Nepal. In comparative politics, for example, French politics is in the version of the Fifth Republic after the French Revolution. Despite the failures and successes of Nepal’s political history, in a liberal democracy, all Nepali people depend on the art of doing politics as much as possible when time and tide are cruel and tough.

Nepal’s entry into federalism under this process is another stage of decentralization. The idea of local-oriented self-government, which has been promised in the past or declared in political history, can be considered as the political remedy of overdue administrative affairs. In addition, the voice of inclusive democracy is characterized by respect for plurality and its spiritual acceptance and self-co-existence. It would not be an exaggeration to say that political knowledge is the vehicle of change in the form and structure of the state. In the context of changing world affairs, the end of the old, conservative and authoritarian tendencies is inevitable. The friction of equity and equality in our life world, society and national sphere can also be taken as a part and parcel of political conduct. It is time to jump from simple talk to follow the results of positive thinking in politics. Politics is considered the art of both the possible and the impossible. Because of these state activities, sophisticated and dynamic politics will become the current vernacular and reality of the new Nepal.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Climate & Environment

- Defence &Security

- Politics & Government

- Science & Technology

- Social Issues

Brill | Nijhoff

Brill | Wageningen Academic

Brill Germany / Austria

Böhlau

Brill | Fink

Brill | mentis

Brill | Schöningh

Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht

V&R unipress

Open Access

Open Access for Authors

Open Access and Research Funding

Open Access for Librarians

Open Access for Academic Societies

Discover Brill’s Open Access Content

Organization

Stay updated

Corporate Social Responsiblity

Investor Relations

Policies, rights & permissions

Review a Brill Book

Author Portal

How to publish with Brill: Files & Guides

Fonts, Scripts and Unicode

Publication Ethics & COPE Compliance

Data Sharing Policy

Brill MyBook

Ordering from Brill

Author Newsletter

Piracy Reporting Form

Sales Managers and Sales Contacts

Ordering From Brill

Titles No Longer Published by Brill

Catalogs, Flyers and Price Lists

E-Book Collections Title Lists and MARC Records

How to Manage your Online Holdings

LibLynx Access Management

Discovery Services

KBART Files

MARC Records

Online User and Order Help

Rights and Permissions

Latest Key Figures

Latest Financial Press Releases and Reports

Annual General Meeting of Shareholders

Share Information

Specialty Products

Press and Reviews

Share link with colleague or librarian

Stay informed about this journal!

- Get New Issue Alerts

- Get Advance Article alerts

- Get Citation Alerts

Diversity, Multilingualism and Democratic Practices in Nepal

This paper presents the relationship among Nepal’s linguistic diversity, multilingualism, and democratic practices by bringing into ideas from the global north and global south. The guiding question for exploring this relationship is, “why is Nepal’s linguistic diversity being squeezed despite the formulation of democratic and inclusive language policies that intended to promote multilingualism?”. To investigate this concern, qualitative data were obtained from semi-structured interviews with two purposively selected high-profile people working in the capacity of language policymaking in the state agencies. In Nepal, although democracy promoted awareness towards the issue of language rights and the need of preservation and promotion of minority languages, the narrowing of multilingual diversity continued in practice. This study concluded that democracy allowed neoliberal ideologies to penetrate sociolinguistic spaces and put greater emphasis on English and Nepali. While there is an intertwined relationship between linguistic diversity, democracy, and multilingualism, the ongoing democratic practices have become counterproductive in maintaining the linguistic diversity leading to the marginalization of minority and lesser-known languages. Also, despite ample literature documenting linguistic diversity as a resource and opportunity, the notions of ‘linguistic diversity’ and ‘multilingualism’ were utilized merely as political agendas and issues of critical discourses which have left negligible impact on changing the conventionalized practices of linguistic domination of Nepali and English. Therefore, we question the co-existence of diversity and democracy and claim that democracy alone does not necessarily contribute to the protection of linguistic diversity. In line with this concept, democratic practices could even be counterproductive in the promotion and protection of linguistic diversity. Our findings suggest future interventions about essentializing the use of minority languages in education and governance, alongside democracy providing the fertile grounds for policy pitches to address micro problems in maintaining multilingualism within a democracy.

- Introduction

Nepal is a multilingual, multicultural, multiracial, and multi-religious country (Constitution of Nepal 2007 ; 2015 ) situated in the Greater Himalayan Region, the mega center of biodiversity, and home to more than one-sixth of world languages ( Turin 2007 ). The tremendous linguistic diversity, with four major language families namely Indo-Aryan, Tibeto-Burman, Dravidian (Munda), and Austro-Asiatic and one language isolate i.e., Kusunda, is one of the aspects of its national identity. The National Population and Housing Census (Central Bureau of Statistics [ cbs ] 2012 ) records more than 123 languages spoken as mother tongues, with an additional category of “other unknown languages” – with close to half million speakers while as many as 129 languages have also been recorded recently ( Language Commission 2019 ). Despite this huge linguistic and cultural diversity, it has been found that the speakers of traditionally unwritten and increasingly endangered vernacular languages have been shifting towards the regional, national and even international languages that carry relatively better economic benefits, access to education, trade, and participation in mainstream politics. This is understood as an impact of the forces of neoliberal ideologies ( Sharma and Phyak 2017 ). The instance of adoption of Nepali and English as media for education, business, and communication is also reported among ethnic communities instead of using the local languages, especially in urban contexts such as the Kathmandu Valley ( Gautam 2020a ). This trend has contributed to the weakening of the functional status and strength of many ethnic/indigenous languages, igniting several movements initiated by indigenous communities. At the same time, there are mounting challenges for the preservation and promotion of those languages due to both policy and practice lapses at micro levels ( Poudel and Choi 2020 ). Though there are several instances of attempts by national governments and related communities for the promotion and preservation of these languages, these efforts have been found to be inconsistent across history. In that, at various times, some governments have promoted monolingual policies whereas, at other times, some other governments have adopted multilingual policies.

Amidst these attempts, both monolingual and multilingual ideologies emerged to the forefront of the debate concerning whether and how to preserve languages, and how they are negotiated in everyday life as well ( Gynne, Bagga-Gupta and Lainio 2016 ). These ideologies emerged as agendas of political discourse perhaps due to the political parties’ attempts to please as well as empower the communities that have their indigenous and ethnolinguistic identities for political reasons. In this paper, we have explored such issues that have emerged around the values of diversity, democracy, and multilingualism while shaping policymaking processes. In doing so, we assess recent trends on linguistic diversity relating to Nepal’s democratic practices with special reference to its historical dimension drawing on instances from the changing status of languages and diversity, and the linguistic practices therein. We also present our critical evaluation of the current policy based on the analysis of legal and policy documents, and practices based on the analysis of interview data.

Supported by our in-depth exploration of the policies and practices, a study of the relevant literature from the countries in the global south, in-depth interviews with participants, we have identified several issues within the democratic polity that have impacted Nepal’s linguistic diversity in various ways. Finally, some implications have been drawn for future planning directions to enrich and maintain multilingualism within the democratic system in Nepal.

- Diversity and Language Vitality in Nepal

Diversity emerges and exists when people from different identity orientations such as races, nationalities, ethnicities, religions, or even philosophies come together to form a community that recognizes and celebrates the values of all backgrounds (also, see Bagga-Gupta and Messina Dahlberg 2018 ). As stated earlier, linguistic, cultural, and ethnic diversity are the essences of Nepalese society, and such diversity characteristics have been existing since the early history of Nepal. All these diversities make up Nepal’s collective multilingual and multicultural identity. The domains of geographical, linguistic, and cultural diversities hold a mutually reinforcing connection among the people in constituting Nepal’s collective identity. Comprising an area of 147,516 square kilometers, 1 with a length of 885 kilometers from east to west and a breadth of 193 kilometers from north to south, Nepal embraces the demographic, cultural and linguistic diversities influenced by people-to-people connection with India on the south and China on the north. Along the three ecological zones, 2 a total of 125 officially recognized ethnic and caste groups reside ( Yadava 2014 ), making this country ethnically and socio-culturally diverse, not only geographically, but also with varied demographic characteristics of the people.

Similarly, Nepal is a “home of 5,400 plus species of higher plants and more than 850 species of birds measuring about 2.2% and 9.4% of the world’s level of biodiversity per unit area matched by a similar rate of linguistic and cultural variation” ( Turin 2007 , 14). This biodiversity, which also links with the social and cultural systems of the communities, contributes to the enrichment of relevant cultural patterns, and enriches the country’s linguistic repertoire. All these species exist through the network of interrelationships in an ecosystem, which also matters for language preservation ( Crystal 2000 ). The diversity of cultural patterns and values also highlight the role of language within. For instance, Crystal (2000, 34) argues that “If the development of multiple cultures is so important then the role of languages becomes critical, for cultures are chiefly transmitted through spoken and written languages”. Although the cultural aspect of diversity is beyond the focus of this paper, it is sensible enough to note that there is an explicit link between language and culture for the very survival of the both, and the ethnic and cultural identity emerge therein. Embracing situated diversity in the national systems is important for Nepal as we see the very identity of this country lies in the same premises. For this, policy provisions in celebrating, preserving, and accommodating diversity and multilingualism have been well articulated in the macro national policies that came out in recent decades ( The Constitution of Nepal 2015 ; National Planning Commission 2013 ). The brief historical account hereafter exemplifies and elaborates on the evolutionary development of such policies in Nepal.

- Diversity and Multilingualism in Nepal: A Glimpse of Language Policy

Despite being multicultural and multilingual, Nepal preserved ‘ethnic’, instead of ‘civic’, nationalism in its task of nation-building which has been reflected in various policies from unification movement (1736 ad ) to present time. Following the Gorkha conquest 3 Gorkhali or Khas (now known as Nepali spoken by 44.6% of national population- cbs 2012 ), the language of ruling elites and mother tongue of many people in the Hills, was uplifted as the national official language. After unification, a hegemonic policy in terms of language and culture was formulated which promoted the code (linguistic and dress) of the Hill Brahmins, Chhetries and Thakuris to the ideal national code (i.e., ‘Nepali’ as the national language and ‘Daura Suruwal Topi’ 4 as national dress). This has been interpreted as one of the attempts to promote assimilatory national policy (in terms of language and culture) that contributed to curbing both linguistic and cultural diversity. However, for the rulers then, it was an attempt to establish stronger national identity and integrity. The Rana regime 5 further prolonged this nationalist (i.e., ‘one nation-one language’) policy by uplifting the Nepali language in education and public communication (as the language of wider communication within the territory of Nepal). The Rana, during their rule, suppressed the Newar and Hindi language movements, which served as evidence of their deliberate plan to eliminate all but one language, viz. Nepali. In this sense, we can understand that Nepal’s diversity and multilingual identity were suppressed historically in the name of nation-building and promoting national integration among people with diverse ethnic and cultural orientations.

Following the end of Rana oligarchy in 1950, with the establishment of democracy, some changes were noticed concerning the recognition and mainstreaming of the other ethnic/indigenous languages. This instigated policy changes in terms of language use in education as well. However, the status quo of the Nepali language further strengthened as it was made the prominent language of governance and education. The National Education Planning Commission [ nnepc ] (1956), the first national report on education, basically reflected the ideology of monolingualism with the influence of Hugh. B. Wood (one of the prominent scholars and educationists from the US who worked in India was invited by the Government of Nepal to advise the education policy and planning process). The nnepc recommended the following concerning language stating, “If the younger generation is taught to use Nepali as the basic language then other languages will gradually disappear, the greater the national strength and unity” (Ministry of Education [ moe ] 1956 , 97). Although this report formed the backbone of Nepal’s education system, it also paved the way for minimizing the potential for empowering the languages of the nation. Pradhan (2019, 169) also writes that this commission attempted to “coalesce the ideas of Nepali nationalism around the triumvirate of Nepali language, monarchy and Hindu religion as uniquely Nepali”. The same was reinforced by the K. I. Singh government in 1957 by prescribing Nepali as a medium of instruction in school education.

The Panchayat regime 6 also promoted the use of Nepali as the only language of administration, education, and media in compliance with the Panchayat slogan ‘one language, one dress, one country’ ( eutaa bhasha, eutaa bhesh, eutaa desh ), again providing a favor for the strengthening of the monolingual nationalistic ideology (in other words, the assimilatory policy). Such an ideology can be seen in the report of the All-Round National Education Commission (1961) as well. Not only in education but also in governance, English, or Nepali were made mandatory in recording all documents of companies through the Company Act (1964). Following the Panchayat system, with the restoration of democracy in 1990, the Constitution of Nepal ( 1991 , part 1, article 6.1 and 6.2) provisioned the Nepali language written in Devnagari 7 script as the national language, while also recognizing all the mother tongues as the languages of the nation with their official eligibility as a medium of instruction up to primary education. 8 Similarly, the Interim Constitution of Nepal (2007) , which came as a collective outcome of the Maoist insurgency 9 and Andolan ii (Public movement - ii ) continued to strengthen the Nepali language but ensured (in its part 1, article 5[2]) that each community has the right to get education in their mother tongue and the right to preserve and promote their languages, script, and culture as well.

The recognition of all the mother tongues as the languages of the nation was a progressive step ahead provisioned by the Interim Constitution of Nepal (2007) . Apart from further confirming the right of each community residing in Nepal to preserve and promote its language, script, cultural civility, and heritage, this constitution (Part 3, Article 17) enshrined the right to each community to obtain basic education in their mother tongue as provided for in the law. The same was well-articulated in the Constitution of Nepal (2015) as well, and each state was given the authority to provide one or many languages spoken by the majority population as the official language(s). Along with this provision, the Language Commission was established to study and recommend other matters relating to language (part 1, article 7 of the constitution). However, it can be concluded that these policy provisions that embrace diversity will have less effect if the concerned communities or agencies do not translate them into practice.

This small-scale case study is based on both primary and secondary data sets. The primary data were collected from semi-structured interviews with two purposively selected participants who we identified through our professional networks. The secondary data were obtained from detailed reading of available literature about language policy and planning such as legislative documents, policy papers, and research papers. The two interviewees, Mr Anjan and Mr Akela (pseudonyms used) have extensive work experience in the field of education, governance, constitution-making, and advocacy for language preservation and promotion in Nepal. Anjan and Akela emerge from two different backgrounds. Anjan worked at the Ministry of Education for more than 25 years, studied about multilingual education from a university in Europe as a part of his higher education. While at the ministry, he worked in the capacity of director at central offices such as the Office of the Controller of Examination, Department of Education, Curriculum Development Center, and served in the most influencing decision-making positions in the areas of language and education policy planning in Nepal. On the other hand, Akela worked as a politician and journalist, teacher educator who later joined Radio Nepal, engaged in various cultural advocacy forums of the Communist Party of Nepal, and again moved to politics at the later part of his life. He was an elected member of the parliament in the Constituent Assembly. While Anjan is the native speaker of Nepali, Akela is a native speaker of Bhojpuri and learned Nepali as a second language among other languages such as Hindi, Maithili, English, etc. In that, both individuals are still active in language politics, policy, and planning, however, they are from different socio-cultural, linguistic, and geopolitical backgrounds. We claim that their ideas have made our understanding of linguistic diversity and democracy more enriched and reliable since both have experienced the major political transitions in Nepal and were involved in key policymaking positions. Also, both have been actively engaged in the language policy processes and advocacy. Therefore, our trust in the data obtained from the interviews with them lies in their history, professional background, and engagement.

They were interviewed online, using the Zoom interactive videoconferencing platform. The semi-structured interviews lasted for approximately one hour each. The questions asked were primarily related to the overarching concern “Why is Nepal’s linguistic diversity being squeezed despite the formulation of democratic and inclusive language policies that intended to promote multilingualism? However, several new concerns (e.g., ultranationalism, pragmatic gaps in policy implementation) emerged during the interviews (cf. the findings and discussion below). The interviews were video recorded, they were transcribed verbatim, and the relevant extracts were translated into English (by the authors) and were double-checked for accuracy and reliability. We have analyzed the data without being stuck to any specific theory, but rather with inductively generated themes ( Miles, Huberman, and Saldana 2014 ), and have positioned ourselves on the critical perspectives that challenge the historical and structural practices contributing to the understanding of inequalities and marginalization of the ethnic/indigenous languages. In other words, we looked at the data in reference to our major concern that questions the co-existence of democracy and linguistic diversity in multilingual contexts. We examined the relationship between historically shifting democratic practices and the situated linguistic diversity of Nepal, questioning whether democracy promotes diversity or subdues it. The empirical data have been integrated with the policy information, which facilitated us to generate relevant themes that relate to the focus of the study. Hence, the trichotomy of diversity, democracy, and multilingualism constitutes the backbone of the analytical framework in this paper.

We have taken our positions on the critical theories that challenge the historical and structural practices contributing to the understanding of inequalities and marginalization of the languages. Such practices have been promoted by democracies of various types (usually in the global North and the South) instead of facilitating the promotion of linguistic diversities. Hence the discussion moves around the trichotomy of diversity, democracy, and multilingualism as an analytical framework.

Findings and Discussion

This section presents the findings of the data organized around inductively generated themes presented in subthemes that deal with historicity of language policy, democracy and its impact on diversity, conceptualization of linguistic diversity (e.g., diversity as resources vs diversity as problem), community engagement in promotion and protection of languages, instances of language contact, and impact of global North ideologies on the language policy and practice processes of global South. The findings are also discussed integrating empirical data and the available literature as appropriate.

- ‘One Nation’ Ideology and Linguistic Diversity

Historically, even before the unification of Nepal, there were several principalities in which the Kings used to speak their languages, and the linguistic diversity was preserved and strengthened”. In a follow-up response to the same query, he claimed, “The geopolitical, historical, socio-political and anthropological history recognized the multilingual social dynamics, however, the national policies after the unification could not embrace such diversity”.

He relates his claim with the inability to embrace diversity as expected within the current political systems and the ideologies of Nepali nationalism and adds that practices of promoting only Nepali language constitute instances of growing ultranationalism. Ultra-nationalism refers to the ideology and the practice of promoting the interest of one state or people in the name of extreme nationalism, with very little or no attention to consolidating democratic institutions ( Irvine 1997 ). Akela emphasizes that the government’s plurilingual policies will not operate as the practice has largely shaped people’s orientation towards Nepali and English, sidelining the regional and local languages. Anjan also expressed a similar perception as, “Though deliberate efforts are made in the policy level to promote the regional/local languages through status planning, there still lies the attitudinal problem which undermines the potential of bringing local languages into practice. Their claims echo discontents expressed by the Language Commission (2019) in its report regarding the failure in translating the national policies that value minority languages into practice, including language use for official as well as educational purposes.

- Diversity and Democracy

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) asserts that democracy assures the basic human right for self-determination and full participation of people in various aspects of their living such as decision-making concerning their language and culture. It also provides them with ways of assuring social benefits such as equal opportunities and social justice (Pillar, 2016). In Nepal, diversity was promoted by democracy through policy provisions, especially after the promulgation of the Constitution of Nepal in 1990 following the Nepali-only monolingual policy of the absolute monarchy (alternatively the Panchayat regime). The basic rights for the use of indigenous languages were assured in the constitution as well as other educational acts formed as outcomes of democratic political turns. The changes in the policy provisions provided opportunities for linguists, language rights activists, and advocacy groups/individuals to explore more about their languages and cultures. Due to their attempts, also supported by the democratic political system, new languages (e.g., Santhali, Bote, Dhimal, etc.) were identified and recognized. For instance, a total of 31 languages were recorded by the National Census in 1991, whereas after the establishment of democracy, the successive censuses in 2001 and 2011 identified a total of 92 and 123 languages respectively ( Yadava 2014 ). Accordingly, to streamline the mother tongue education, as a form of campaign for preservation and promotion of the languages, teaching and learning materials (for up to grade 3) were prepared in more than 22 languages by cdc . However, pragmatic actions remained fragile for mother tongue education up to grade 3 to support the aspiration for promoting diversity. The ineffective implementation (or perhaps a failure) of the state policies to run mother tongue education up to primary level ultimately resulted in constraining multilingualism instead of promoting it. Although the statistical data shows that the number of languages spoken as mother tongues in Nepal is 129 ( Language Commission 2019 ), some scholars still doubt whether these languages functionally exist in reality ( Gautam 2019 ), or if they are there, then the practice may be fragile. This fragile practice in the field can be noted to be influenced by a multitude of factors including lack of community participation, hegemonic attitude of people with power of the dominant languages (e.g., Nepali, Maithili, etc.), and their agency against the minority languages.

Nepal’s participation in the UN organizations and endorsement of most of its declarations compelled Nepal Government to form its domestic policies in line with the commitments made in the international communities to ensure the fundamental concerns of democracy, and that further contributed to creating pressure for right-based policies in Nepal.

Anjan echoed a similar belief saying, “ The recognition of linguistic diversity in the macro policies is the result of democracy” . From the observation of their claims and, also with support from the available literature (e.g., Sonntag 1995 , 2007 ; Pradhan 2019 ; Poudel and Choi 2020 ), it can be strongly claimed that the establishment of multiparty democracy in 1990 in Nepal contributed to the wider recognition of linguistic diversity. Also, “The Nepali-only policy was discarded in favor of an official language policy that recognized Nepal’s linguistic diversity” ( Sonntag 2007 , 205). This informs that the democratic political system that remained open to the neoliberal economy embraced the linguistic diversity as a resource, due to which the multilingual identity of Nepalese society was officially recognized. However, at the same time, this political system could not preserve the minority/indigenous languages as expected, which prompted us to question the co-existence of diversity and democracy. Also, “It is very much a matter of democracy that everyone has the right to language and that society has a common language that everyone can understand and use” (Rosén and Bagga-Gupta 2015, 59). This implies that democratic states (e.g., Nepal, India, Sweden) must address the contradictory discourses of language rights and equity concerns pertaining to language(s) (e.g., Nepali and other indigenous languages). However, the fundamental question still not well-answered, at least in the case of Nepal, is whether democracy can, in a real sense, promote linguistic diversity, or if it narrows down diversity by marginalizing ethnic/minority languages. While responding to this unanswered concern, we have observed that diversity as a resource and diversity as a problem are the two distinct discourses that emerged during the evolutionary process of democracy in Nepal, which was also emphasized by the two participants. Their arguments (see elaboration in 5.3 and 5.4 below) revealed that the two mutually exclusive concerns (diversity as resource vs diversity as problem) parallelly existed in Nepal’s language policy and planning discourse, and they have formed the core of the debate.

- Diversity as a Resource

Both informants in this study argued that diversity must be absolutely understood as a resource, very significant for human beings at the global level. Akela claims, If any language of a community dies, the culture and lifestyle of that community disappears, reduces biodiversity, and that ultimately will be a threat to humanity . He understands linguistic diversity as a part of the ecology, and strongly argues that it should be protected. Agnihotri (2017, 185) also echoes a similar belief as Just as biodiversity enriches the life of a forest, linguistic diversity enhances the intellectual well-being of individuals and groups, both small and large . Akela adds, No language should die for our existence as well . Both Akela and Anjan pointed out that the discourse on diversity and multilingualism in Nepal has been strengthened and institutionalized after 1990 when the country entered a multiparty democratic system.

However, Akela thinks that the current legislative provisions have only partially addressed the diversity needs to fit Nepal’s super diverse context. He also points to the influence of the global North in bringing ultranationalist values in Nepal’s policymaking. He does not think that the identity issues raised and addressed through policy processes would make significant differences as they were just brought into the field as agendas of political bargains. He stated, The agendas of identity are just the forked tongues’, translated from [pahichanko sabal ta dekhaune daant matra ho] . He meant that the identity issues have been largely used by the political leaders to deceive the concerned communities for their political benefits. This perception of a political leader, who is also an activist and scholar from the concerned ethnic community is very much meaningful for this study, as it indicates that Nepal’s democratic path initiated a comprehensive discourse for the protection of diversity. However, such discourse has been mostly used for political goals, rather than changing the grass-root practice and engagement of the concerned communities to bring indigenous knowledge and skills into the education systems. However, it has been well-agreed that multilingualism, and variability are constitutive of human existence. We usually engage in the dynamic dialogic interaction to construct our identity within the diversity we have ( Agnihotri 2017 ). Agnihotri (ibid) thinks that the potentiality for multilingualism is innately programmed in human beings, so that linguistic and cultural harmony in our communities can be developed, for which the democratic political system facilitates.

- Diversity as a Problem

There is a strong motivation of people towards educating their children in Nepali and English, however they stick to their ethnic languages for communicative purposes. And when there comes the issue of language of the provincial or regional communication, there is a conflict between two of the major regional languages (i.e., Maithili and Bhojpuri).

He sees that such conflicts are due to ideological divides among people themselves. It can, therefore, be observed that this community-level ideology and practice has led to the fragmentation of values associated with their languages, most probably harming the socio-historical harmony among languages.

Nettle (2000, 335) claimed, “Linguistic and ethnic fragmentation relates to low levels of economic development since it is associated with societal divisions and conflict, low mobility, limited trade, imperfect markets, and poor communications in general”. The low levels of societal values and economic development linked with the indigenous languages might have led to intergenerational shifts among the youths of these communities ( Gautam 2019 ). Consequently, this trend has impacted the participation of the relevant communities in campaigns for revitalization of their languages. In addition to this, on the educational dimension of language use, the “schools are often not always aware of the linguistic and cultural wealth they own and could reveal as an important part of their school identities” ( Finkbeiner 2011 , 86). Despite the availability of rich multilingual diversity, the rapid expansion of English medium instruction, irrespective of the local as well as national language, in private and public schools in Nepal is a lively example of how the mother tongues are undervalued. This trend has indirectly contributed to the devaluation of the potential of indigenous language use in education systems in multilingual communities globally.

- The Role of Community Participation in Language Preservation and Promotion

In principle, the participatory democracy and the consequential reconciliation often appear to be the only suitable approach ( Agnihotri 2017 ), but in reality, the community participation in the promotion and protection of the indigenous languages is negligible if we take the case of multilingual countries such as Nepal and India. With the utilization of democratic ideals, some communities (e.g., Tamang, Newar, Maithili, Rajbansi, etc.) have made several initiatives but largely in many communities the motivation towards educating their children in their ethnic/indigenous languages is negligible, especially conditioned by the local level policymakers’ inaction (see, Poudel and Choi 2020 ), and their demotivation are influenced by the pedagogical and ideological debates around the discourses on empowering local languages ( Poudel 2019 ). This practice has served the interest of the elites who, with influences from various sectors, would like to homogenize the societies linguistically and culturally, which creates inequalities of various types.

A sense of ownership in the community about keeping their language(s) lively is very significant for the preservation and promotion of both the language and culture. For instance, in Nepal, some languages (e.g., Kusunda, Raute) are endangered as the number of native speakers is declining, and there is a lack of community participation in preserving them. Akala says, “ Unless the community owns it, initiates it, no outsider can feel the language as the native-speakers do. The emic feeling is far stronger than the etic one ”. However, he believes that the cause for diminishing participation of the community in language preservation initiatives is due to the structural constraints that shape people’s mindset towards the preference of either Nepali or English. Rosén and Bagga-Gupta (2013, 70) stated that “It is through participation and interaction that the social structure that forms the practice is (trans)formed and (re)produced”. Both Anjan and Akela believe that the widespread use or practice of Nepali and English in academia, governance and education has contributed to the (re)production of the hegemonic power structure of these languages over the other ethnic/indigenous ones, and this structure has (trans)formed the public understanding that learning in indigenous languages is inferior to the dominant ones (Kansakar, 1996). For them, this trend is a counterproductive outcome of democracy that promoted neoliberal ideas ( Siegel 2006 ) and led the languages into the competitive edge in the societies, which ultimately led to the promotion of the promoted, and suppression of the suppressed in which the “ideological and affective mismatches that arise out of encounters between people with different language socialization experiences” ( Fujita 2010 , 38) were observed. The data also pointed to the impacts of global North ideologies (for instance, the inclusive democratic ideas) on the discourses of multilingualism of the global South.

- Ideological Construction of the Global North and Impacts on Global South

Nepal’s growing engagement with the international community (through its membership in the UN, wto , imf , etc.), and its political systems have largely influenced attitudinal patterns in Nepalese society. From a geopolitical perspective, Nepal is sandwiched between two giant countries India and China, and the changes in the neighborhood would influence it on a larger scale. Besides, the development in the global North would always have a chain effect in the countries of the global South. For instance, the British colonial government of India then promoted English amidst other languages, and a similar trend emerged in Nepal with the effect of the environment in the neighborhood. Such geopolitical conditions and the waves gravely influenced the closely related communities to the development of nationalism and the creation of nation-states, including a new Europe perceived as superior to other parts of the world ( Bagga-Gupta 2010 ; Gal and Irvine 1995 ; Rosen and Bagga-Gupta 2013 ; Shohamy 2006 ). The ideologies of the countries of the global North have influenced the countries of the global South in many ways, including ideologies of language planning and policy. This has generated a perception and a social space that differentiates ‘us and the other’ through the formation of linguistic-cultural ideologies ( Gynne, Bagga-Gupta and Lainio 2016 ) or creating linguistic imageries constitutive of cultural tools ( Bagga-Gupta and Rao 2018 ) in the communities that have multiple languages in place that ultimately impact relevant social actions. This made some languages valued more than others in the domains of governance and educational spaces ( Poudel and Choi 2020 ; Poudel 2010 ). In the case of Nepal, the first educational commission was influenced by Huge. B. Wood’s ideologies formed out of his involvement in Indian and the western world, and the committee under his leadership had huge influence in collaboration with academia and politicians then recommended for streamlining the education systems through a monolingual ideology. Awasthi (2008) also noted that the ideologies constructed by the Macaulay Minutes (1835) in India had an invisible effect in Nepal’s language policymaking, especially reflected in the nnepc report prepared with the contribution of Mr. Wood. The same ideological structure continued for long, and even today with maintaining Nepali as the national language to be used in governance and education ( Sharma 1986 ), while at the same time allowing other regional or ethnic languages for such purposes as an outcome of democratic political development. It can be understood as having an ideological link with the “Englishization” efforts of many countries in the global North, reflected in nnepc and the reports afterward. In this way, it is not unfair to claim that the ideologies of the global North impacted the linguistic, cultural, and economic systems of countries in the global South (e.g., India, Nepal, etc.).

In addition to that, “the international political-economic structure seems stacked against a substantial or near future diminishment of the north-south gap” (Thompson and Reuveny 2010: 66). The neoliberal trends that emerged from the global North have travelled to the global South, impacting the global-south countries through the language and culture of the former. The unprecedented expansion of English as a global phenomenon ( Dearden 2014 ) can be a living example of such an effect. The advancement in technology and the increasing use of English as the dominant language of that domain further brought the global North and South together, influencing each other. As a result, the language also became one of the aspects of the north-south political economy. It involved various combinations of developmental states recapturing domestic markets from foreign exporters (import substitution) and the recapture of domestic business (nationalization). The outcome, aided by investments in education, was a new elite of technical managers and professionals who could build on historical experience and opportunities through the commodification of the English language.

Besides, the technology sharing, migration and demographic changes have had variable impacts on the north-south gap. For instance, Nepali youths’ labor migration and their English preference have also impacted the “generational shifts in languages” ( Gautam 2020a , 140). The youths’ migration to the countries in the Middle East and their participation in the global marketplaces in the global North countries have contributed to reshaping of their ideologies towards the home languages and English. Anjan’s statement, “ We have made whimsical choices in our social and education systems, (e.g., choice of language for education) and are even lured by the ideologies formed even by our immigrant population usually in the western world” . Among many, this can be understood as one of the causes for accentuated divergent tendencies in language shifts, usually from the indigenous and national languages to English. Similar cases were reported in the countries of globalized economies as well. For instance, in Singapore, Lakshmi (2016, 229) concluded “Despite governmental and community efforts to support Tamil maintenance in Singapore, census and school data show a decrease in the number of Indian families using Tamil as the predominant home language”, and perhaps this is an instance of a generalizable scenario of squeezing multilingualism in the micro level.

- Multilingualism and Language Contact as an Outcome of Democracy

Multilingualism is a defining feature of intricate social and cultural practices ( Lafkioui 2013 ), and it is influenced gravely by the dynamic social, cultural, and political processes such as migration, social movements, and mobility in any society. For instance, the global impact of migration entailed language contact in multilingual countries ( Gautam 2020a , 2021 ), and this was evidenced in various communities across Nepal. Multilingual diversity has also been threatened by such processes, as the language choices have been more constrained due to limited linguistic competencies and interactive skills among the migrants as members of the community. It is also possible that the more intense the migration, the more homogeneity in language use emerges. Highly migrant communities (usually in the urban spaces) attempt to develop a shared linguistic and cultural identity through increasingly engaging in the construction of new normal patterns of shared beliefs and values.

Languages are a treasure trove of literature, philosophy, and worldviews, and the loss of languages will have a huge intellectual catastrophe ( Abbi 2017 ). The protection of 6000 plus languages in the world has been a big challenge as estimates have shown a language dies every fortnight on this planet (ibid). This global problem has affected Nepal’s linguistic diversity as well in an unprecedented way. Regmi (2017) writes that nearly 44% of languages are safe, and the rest of the 56% languages are broadly labelled as threatened and shifting, and this trend has been growing. Also, most of the Nepalese minority language speaking communities have been influenced by the impact of cross-border links through media, marriage, migration (M3s) in the city areas ( Gautam 2018 , 2020a ), and these trends have intensified the trend of language contacts among the dominant ones further reducing the functional values of the minority languages. Due to this, the multilingual arenas turned to be more complex zones for incidences of contacts across local, national, and international languages reproducing the dominance of the dominating languages. The strongest impact of language contact on multilingualism in Nepal can be observed after the 1990s that increased people’s participation in social spaces in inclusive democratic processes. The “Nepali-only policy of the absolute monarchy was discarded in favor of an official language policy that recognized Nepal’s linguistic diversity” ( Sonntag 2007 , 205). On top of that, the impact of the Maoist revolution (1996–2006) brought lots of social and cultural changes in Nepalese multilingualism. Many ethnic communities were displaced from their original homelands to the capital city, and other urban contexts because of political pressure from the agitating parties then. Hence, the urban contexts such as Kathmandu (largely Newar speaking area), Pokhara (Gurung and Magar speaking area), Nepalgunj (Tharu speaking area), Kapilvastu (Awadhi speaking area), etc. were established as zones for the increasing trend of language contacts as people from various remote villages hurled to these cities for opportunities of education, employment, and business. Nowadays, people have gradually well-assimilated with the dominant language and cultural values developing complex social zones for language contact activities.

The consequences of such contacts which are further triggered by democratic political processes, are multifaceted. One of the major effects is the shift of such minority languages and their cultures towards assimilation into the dominant ones. Such assimilation has led to erasing of the indigenous languages and cultures, not even leaving linguistic marks of some dead languages for the future generations. This, as one of the reasons for the inter-generational shift, was reported by our participants as well. Gautam (2020b, 204) claims, “The young generations are not very much interested about the role of language in community rather they are more concerned about globalization and the economic activities” Similarly, Anjan says, “ The contemporary generation of parents and their children do not value their ethnic language on the economic grounds, and that has impacted the way they make language choices at home and in schools ”. Indirectly, he pointed towards the increasing trend of educating in English medium. This shift has impacted the policymaking process regarding language use in education as well ( Poudel and Choi 2020 ), because the relevant policymaking bodies did not end up with strong resolutions to use the already minoritized local languages in education and governance.

- Conclusion and Implications

In this paper, we discussed the way that a democratic country (here, Nepal) has undergone through a process of democratizing its macro policies for the promotion and preservation of its linguistic diversity, which provided shreds of evidence that such practices have minimal impact on the substantial results due to the processes of glocalization ( Choi 2017 ). The identification of new languages and recognition of multilingualism through scheduling of these languages in the constitution have been the visible results of democratic governance. However, largely mono and/or bilingual practices in governance, education, and public communication show that the promises of the constitution have not materialized as yet. Based on the analysis of the data, we conclude that democracy in Nepal functioned as a “double-edged sword”, which on the one hand promoted efforts of preservation and promotion of linguistic diversity, while on the other hand, contributed to constraining the size of diversity by vitalizing mainly Nepali and English, sidelining the potential of indigenous languages. Such a role of democracy promoted the ethnic and indigenous communities’ active engagement in reacting against the macro policies pertaining to languages. This issue was also used as an agenda of political gains but with very little or nil impact on the ongoing practices within their own linguistic and cultural communities. The democratic ideology fundamentally borrowed from the global North had done more justice at the macro policy level but created inequalities and injustices in practices at the micro level, and that consequently turned the investments and attempts in promoting linguistic diversity futile.

Our conclusion implies that in Nepal democracy promoted monolingual/bilingual ways of thinking about multilingualism, which became counterproductive to the mission of protecting linguistic diversity. Here, our understanding adheres to Pillar’s (2016, 32) critical claim that “The monolingual ways of seeing multilingualism entails a focus on the product of the monolingual academic texts”. In other words, democracy did not practically contribute to promoting linguistic diversity though it developed awareness of the linguistic rights of the individuals and communities of minority languages. During the democratic evolutions, the state intervention to preserve and promote these languages remained inconsistent, as some governments intentionally discouraged the planned promotion compared to others. Although monolingual and multilingual ideologies were debated in political and social spaces, the substantial effects of such debates in transforming current practices are yet to be materialized. We also claim that, owing to the uniquely complex nature of Nepal’s linguistic and demographic diversity, the ideal policies, especially those related to linguistic diversity and multilingualism, developed outside of Nepal are likely to be ineffective or perhaps will have counterproductive effects. This rightly informs of the fact that the governmental systems need to develop all-inclusive policies that adhere to Nepal’s unique situation and translate into observable practices to fundamentally change the current situation of diminishing linguistic diversity.

The conclusion of this paper also implies that democratic political system alone will not be sufficient to promote diversity, unless the relevant communities proactively engage in localized policymaking, valuing their own cultures and languages, and link them with the peripheral world. Despite the increasing awareness of the indigenous identity and rights among people including those from the concerned communities, the streamlined long-term visions in changing the practice are essential to utilize the democratic political systems in protecting and promoting multilingual diversity. We also appeal to the reassessment of the investments (or probably the wasteful investments) in the name of promoting multilingualism in the case of Nepal, as all the efforts made for this, or with this agenda, have proved to be less effective to materialize the very mission of protecting and promoting diversity and multilingualism. Hence, we suggest for a planned intervention in changing the practice at the local governmental level to build collective strength to promote ethnic/indigenous languages in wider use, including their socio-cultural and economic values so that the current and the future generation can feel assured that they can survive out of the learning of local/ethnic languages. Although in this paper, we explored the case of Nepal, our conclusions are informative to the other similar contexts globally where minority languages are endangered due to less supportive political systems where the ethnic minority communities are struggling hard to revive them back.

- Acknowledgments

We express our deep sense of gratitude to the informants of this study for their trust in us, and the great sharing based on our queries, despite their very busy schedule at the time of crisis due to Covid-19 lockdown in Nepal. At the same time, we acknowledge all the scholars whose works have been cited in the paper.

Abbi , Anvita. 2017 . “ Human Cognitive Abilities and Safeguarding Linguistic Diversity .” IIC Quarterly 44 ( 2 ): 83 – 100 .

- Search Google Scholar

- Export Citation

Agnihotri , Rama Kant. 2017 . “ Identity and Multilinguality: The Case of India ”. In: Language Policy, Culture, and Identity in Asian Contexts ”, edited by A. M. Tsui and J. W. Tollefson , (Pp. 185 – 204 ). London : Routledge .

Awasthi , Lav Deo. 2008 . “ Importation of Ideologies: From Macaulay Minutes to Wood Commission .” Journal of Education and Research . 1 ( 1 ): 21 – 30 .

Bagga-Gupta , Sangeeta , and Aprameya Rao . 2018 . “ Languaging in Digital Global South–North Spaces in the Twenty-first Century: Media, Language and Identity in Political Discourse .” Bandung: Journal of the Global South. 5 ( 1 ): 1 – 34 .

Bagga-Gupta , Sangeeta , and Giulia Messina Dahlberg . 2018 . “ Meaning-making or Heterogeneity in the Areas of Language and Identity: The Case of Translanguaging and Nyanlanda (newly- arrived) Across Time and Space .” International Journal of Multilingualism 15 ( 4 ): 383 – 411 .

Bagga-Gupta , Sangeeta. 2010 . “ Creating and (Re)negotiating Boundaries: Representations as Mediation in Visually Oriented Multilingual Swedish School Settings .” Language, Culture and Curriculum 23 ( 3 ): 251 – 276 .

Central Bureau of Statistics. 2012 . National Population and Household Census . Kathmandu : National Planning Commission .

Choi , Tae Hee. 2017 . “ Glocalisation of English Language Education: Comparison of Three Contexts in East Asia .” In Sociological and Philosophical Perspectives on Education in the Asia-Pacific Region , edited by C. M. Lam and Jae Park , 147 – 164 . Singapore : Springer .

Crystal , David. 2000 . Language Death . Cambridge : Cambridge University Press .

Dearden , Julie. 2014 . English as a Medium of Instruction-a Growing Global Phenomenon . London : British Council .

Finkbeiner , Claudia Hilde. 2011 . “ Research and Scholarship in Multilingualism: An Interdisciplinary Multi-Perspective Framework .” Die Neueren Sprachen 2 : 82 – 96 .

Fujita , Emily. 2010 . “ Ideology, Affect, and Socialization in Language Shift and Revitalization: The Experiences of Adults Learning Gaelic in the Western Isles of Scotland .” Language in Society . 39 : 27 – 64 .

Gal , Susan , and Judith T. Irvine . 1995 . “ The Boundaries of Languages and Disciplines: How Ideologies Construct Difference .” Social Research . 62 ( 4 ): 967 – 1001 .

Gautam , Bhim Lal. 2018 . “ Language Shift in Newar: A case study in the Kathmandu valley .” Nepalese Linguistics . 33 ( 1 ): 33 – 42 .

Gautam , Bhim Lal. 2019 . Badalindo pribesh ma bhasa (Language in the Changing Context) .” Nayapatrika Daily. March 13, 2019. URL: https://www.nayapatrikadaily.com/news-details/13971/2019-05-13?fbclid=IwAR2SCT5r86qSEjCD08Vb2xcHVz0Iv4OWOf78Dx0D06zz6pJTb7Jtvx-gbPA .

Gautam , Bhim Lal. 2020a . Language contact in Kathmandu Valley. Ph.D. dissertation , Central Department of Linguistics, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Tribhuvan University , Kathmandu, Nepal .

Gautam , Bhim Lal. 2020b . “ Sociolinguistic Survey of Nepalese Languages: A Critical Evaluation .” Language Ecology . 3 ( 2 ): 190 – 208 .

Gautam , Bhim Lal. 2021 . Language Contact in Nepal: A Study on Language Use and Attitudes . Switzerland : Palgrave-Macmillan .

Government of Nepal. 2015 . The Constitution of Nepal 2015 . Kathmandu : Nepal Government, Minister of Law and Justice .

Gynne , Annaliina , Sangeeta Bagga-Gupta , and Jarmo Lainio . 2016 . “ Practiced Linguistic-Cultural Ideologies and Educational Policies: A Case Study of a “Bilingual Sweden Finnish School ”. Journal of Language, Identity & Education . 15 ( 6 ): 329 – 343 .

Irvine , Jill A. 1997 . “ Ultranationalist Ideology and State-building in Croatia, 1990- 1996 .” Problems of Post-Communism 44 ( 4 ): 30 – 43 .

Kansakar , Tej Ratna. 1996 . “ Multilingualism and the language situation in Nepal .” Linguistics of the Tibeto-Berman Area . 19 ( 2 ): 17 – 30 .

Lafkioui , Mena. 2013 . “ Multilingualism, Multimodality and Identity Construction on French-Based Amazigh (Berber) Websites .” Revue française de linguistique appliquée . 18 ( 2 ): 135 – 151 .

Lakshmi , Seetha. 2016 . “ Use and Impact of Spoken Tamil in the Early Tamil Classrooms .” In Quadrilingual Education in Singapore , edited by Elaine Silver R. and Bokhorst-Heng W. , 229 – 246 . Singapore : Springer .

Language Commission . 2019 . Annual Report of Language Commission of Nepal-2019 . Kathmandu : Language Commission .

Miles , Matthew B. , Huberman , Michael A. , and Johnny Saldana . 2014 . Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook ( 3rd ed. ). California, CA : Sage Publications .

Ministry of Education [ moe ]. 1956 . Education in Nepal: Report of the National Education Planning Commission . Kathmandu : MOE .

National Planning Commission. 2013 . An Approach Paper to the Thirteenth Plan (2013–2016) . Kathmandu : National Planning Commission .

Nettle , Daniel. 2000 . “ Linguistic Fragmentation and the Wealth of Nations: The Fishman-pool Hypothesis Reexamined .” Economic Development and Cultural Change 48 ( 2 ): 335 – 348 .

Piller , Ingrid. 2016 . Linguistic Diversity and Social Justice: An Introduction to Applied Sociolinguistics . Oxford : Oxford University Press .

Poudel , Prem Prasad. 2010 . “ Teaching English in Multilingual Classrooms of Higher Education: The Present Scenario .” Journal of NELTA. 15 ( 1–2 ): 121 – 133 .

Poudel , Prem Prasad. 2019 . “ The Medium of Instruction Policy in Nepal: Towards Critical Engagement on the Ideological and Pedagogical Debate .” Journal of Language and Education 5 ( 3 ): 102 – 110 .

Poudel , Prem Prasad. and Choi , Tae Hee. 2020 . “ Policymakers’ Agency and the Structure: The Case of Medium of Instruction Policy in Multilingual Nepal .” Current Issues in Language Planning. 22 ( 1–2 ): 79 – 98 .

Pradhan , Uma. 2019 . “ Simultaneous Identities: Ethnicity and Nationalism in Mother Tongue Education in Nepal .” Nations and Nationalism. 25 ( 2 ): 718 – 738 .

Regmi , Dan Raj. 2017 . “ Convalescing the Endangered Languages in Nepal: Policy, Practice and Challenges .” Gipan . 3 ( 1 ): 139 – 149 .

Rosén , Jenny Karin and Sangeeta Bagga-Gupta . 2013 . “ Shifting Identity Positions in the Development of Language Education for Immigrants: An Analysis of Discourses Associated with ‘Swedish for Immigrants’ .” Language, Culture and Curriculum. 26 ( 1 ): 68 – 88 .

Rosén , Jenny Karin and Sangeeta , Bagga-Gupta . 2015 . “ Prata svenska, vi är i Sverige!”[“Talk Swedish, we are in Sweden!]: A Study of Practiced Language Policy in Adult Language Learning .” Linguistics and Education . 31 : 59 – 73 .

Sharma , Balkrishna and Phyak , Prem. 2017 . “ Neoliberalism, Linguistic Commodification, and Ethnolinguistic Identity in Multilingual Nepal .” Language in Society. 46 ( 2 ): 231 – 256 .

Sharma , Gopi Nath. 1986 . Nepalma shikshako itihaas, 2043 BS [History of Education in Nepal 1986] . Kathmandu : Samjhana Press .

Shohamy , Elana Goldberg. 2006 . Language Policy: Hidden Agendas and New Approaches . Oxon : Psychology Press .

Siegel , Jeff. 2006 . “ Language Ideologies and the Education of Speakers of Marginalized Language Varieties: Adopting a Critical Awareness Approach .” Linguistics and Education. 17 : 157 – 174 .

Sonntag , Selma K. 1995 . “ Ethnolinguistic Identity and Language Policy in Nepal .” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 1 ( 4 ): 116 – 128 .

Sonntag , Selma, K. 2007 . “ Change and Permanence in Language Politics in Nepal .” In Language Policy, Culture, and Identity in Asian Contexts , edited by Amy B.M. Tsui and James Tollefson , 205 – 217 . Mahwah : Lawrence Erlbaum .

The Constitution of Nepal. 1962 . Kathmandu : His Majesty’s Government of Nepal .

The Constitution of Nepal . 2015 . Kathmandu : Government of Nepal .

The Constitution of the Kingdom of Nepal. 1959 . Kathmandu : His Majesty’s Government of Nepal .

The Constitution of the Kingdom of Nepal . 1991 . Kathmandu : Government of Nepal .

The Government Act of Nepal . 1948 . Kathmandu : His Majesty’s Government of Nepal .

The Interim Constitution of Nepal (6th Amendment). 2007 . Kathmandu : UNDP .

The Nepal Interim Government Act. 1951 . Kathmandu : His Majesty’s Government of Nepal .

Thompson , William R. and Rafael Reuveny . 2010 . Limits to Globalization: North-South Divergence . London : Routledge .

Turin , Mark. 2007 . Linguistic Diversity and the Preservation of Endangered Languages: A Case Study from Nepal . Kathmandu : ICIMOD .

Yadava , Yogendra Prasad. 2014 . Languages of Nepal . Population Monograph . 2 : 51 – 72 .

The Government of Nepal on18 May 2020 (5th Jestha 2077) endorsed the new map including Lipulekh and Kalapani area with a new total area of 147, 516 Square Kilometers.

Nepal is ecologically divided into three ecological zones, i.e., High Hills ( Hima l), Mid Hills ( Pahad ) and Plains ( Terai ). All these three ecological belts are inhabited by varied communities with ethnic, cultural, and linguistic identities.

Gorkha conquest refers to the victory made by Late King Prithivi Narayan Shah who unified Nepal during the period 1736 to 1769 ad .

A typical Nepali dress promoted as the identity of Nepalese people, and so is established as the formal dress code for official functions.

The Rana Oligarchy, in which Ranas ruled the country for 103 years in Nepal between 1846 and 1951.

The Panchayat regime ruled Nepal since 1961 to 1990.

The script in which Nepali language is written.

In Nepal, the education up to grade 5 was termed as primary education. However, recent education restructuring recognizes grade 1–8 as the basic education.

The Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) conducted a 10-year-long insurgency with an agenda of reforming historical, social, and cultural inequality.

Content Metrics

Reference Works

Primary source collections

COVID-19 Collection

How to publish with Brill

Open Access Content

Contact & Info

Sales contacts

Publishing contacts

Stay Updated

Newsletters

Social Media Overview

Terms and Conditions

Privacy Statement

Cookie Settings

Accessibility

Legal Notice

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Statement | Cookie Settings | Accessibility | Legal Notice | Copyright © 2016-2024

Copyright © 2016-2024

- [66.249.64.20|185.66.14.133]

- 185.66.14.133

Character limit 500 /500

- Culture & Lifestyle

- Madhesh Province

- Lumbini Province

- Bagmati Province

- National Security

- Koshi Province

- Gandaki Province

- Karnali Province

- Sudurpaschim Province

- International Sports

- Brunch with the Post

- Life & Style

- Entertainment

- Investigations

- Climate & Environment

- Science & Technology

- Visual Stories

- Crosswords & Sudoku

- Corrections

- Letters to the Editor

- Today's ePaper

Without Fear or Favour UNWIND IN STYLE

What's News :

- UML breaches court precendent

- Inflation falls but prices remain same

- Bir Hospital bed crunch

- Covid on the rise

- Hum Bahadur profile

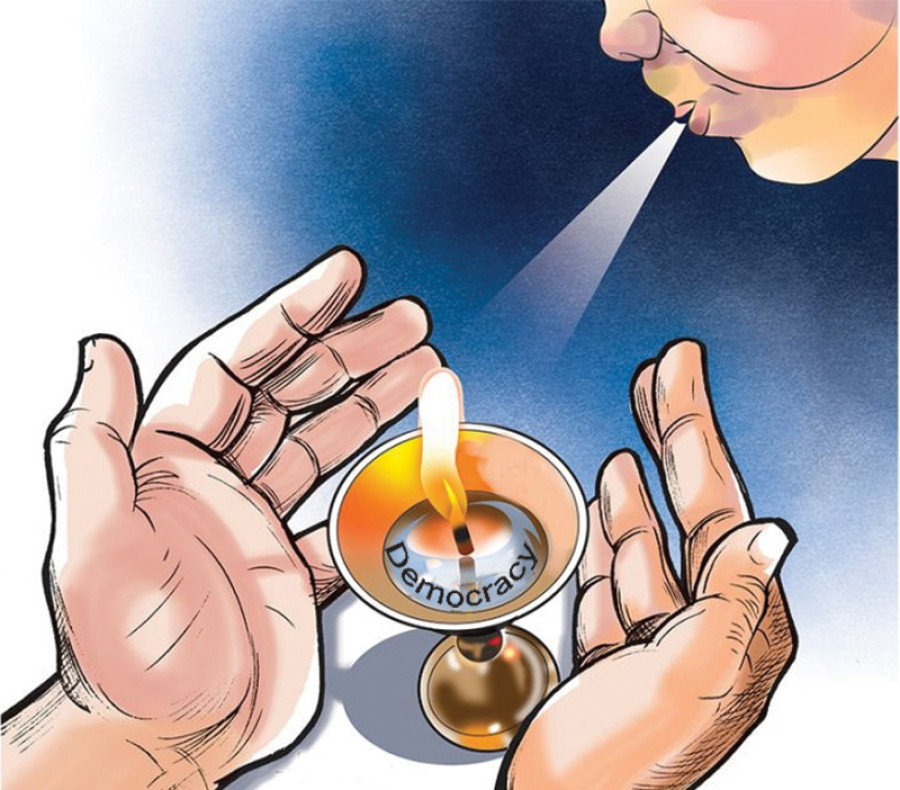

Nepal’s democracy challenges

Seventy years ago, on this day (Falgun 7) Nepal ended 104-year-old Rana rule and ushered in democracy. Nepal’s first steps towards democracy, however, were clumsy. It saw five different governments until 1959 when the country held its first general election. The Nepali Congress, which played a key role in overthrowing the Rana regime, was voted to power with a two-thirds majority. Congress’ BP Koirala was elected prime minister. But Nepal’s democracy dreams were short-lived. Just a year later, in 1960, King Mahendra staged a coup, banned political parties and set up a party-less Panchayat rule, a system the monarch said was “suitable to the Nepali soil”.

It took 30 years before Nepal’s political parties could restore democracy that was snatched away by king Mahendra. In 1990, Nepal proclaimed the dawn of democracy. Maendra’s son Birendra was on the throne. Nepal adopted a multiparty system with the constitutional monarchy and wrote a new constitution in 1990.

But Nepal’s fledgling democracy was assaulted once again. This time by Mahendra’s second son–Gyanendra–in 2005. King Birendra and his family were killed in the 2001 royal massacre.

Nepal needed yet another people’s movement in 2006 which abolished the centuries-old monarchy. A Constituent Assembly in 2015 drew up a new constitution, which was promulgated amid reservations from various sections of society. But five years after the new “people’s” constitution, democracy is once again under threat—this time from KP Sharma Oli, an elected prime minister.

As Nepalis mark Democracy Day, to commemorate the historic day of 1951, the country is yet again facing a democratic crisis.

“We have failed to set up a system, especially after 1990,” said Daman Nath Dhungana, a former House Speaker, who was on the forefront of the 1990 people’s movement, which is also dubbed “first people’s movement”. “It’s unfortunate that even a constitution that was delivered by the Constituent Assembly could not establish a political system.”

Many blame a lack of political culture among the parties for why the country has failed to strengthen democracy.

As in after 1951, the Nepali Congress was voted to power after the restoration of democracy in 1990. Democracy hugely suffered because of the growing intra-party feud in the Congress. Despite leading a majority government, then prime minister Girija Prasad Koirala dissolved the Parliament and called snap polls. Congress senior leader Krishna Prasad Bhattarai had to face a defeat largely due to the internal conflict in the party.

Disenchantment started to grow among the people, politicians were failing to deliver on their promises despite adopting “the world’s best constitution”.

A section of politicians that was vehemently opposed to the parliamentary system was priming itself for a drastic movement, which would later be known as “people's war”—an armed struggle against the state.

As the governments were formed and pulled down in Kathmandu, the Maoists waged the war in 1996, which continued until 2006. By the time it ended, at least 17,000 people had died and thousands were disappeared and maimed.

In 2001, Nepal grabbed international headlines when Birendra, who now in the hindsight many believe was a benevolent monarch, was killed along with his family. His younger brother Gyanendra succeeded.