Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Finding middle way out of Gaza war

Roadmap to Gaza peace may run through Oslo

Why Democrats, Republicans, who appear at war these days, really need each other

At the onset of the pandemic, the number of calls into hotlines went down. “But that didn’t mean that suddenly domestic violence was declining. It meant that the opportunities to have a safe space to call or ask for help were limited,” said Marianna Yang.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘Shadow pandemic’ of domestic violence

Harvard Staff Writer

Law School’s Marianna Yang examines rise in factors, hurdles in courts for victims

Violence against women increased to record levels around the world following lockdowns to control the spread of the COVID-19 virus. The United Nations called the situation a “shadow pandemic” in a 2021 report about domestic violence in 13 nations in Africa, Asia, South America, Eastern Europe, and the Balkans. In the United States, the American Journal of Emergency Medicine reported alarming trends in U.S. domestic violence, and the National Domestic Violence Hotline ( The Hotline ) received more than 74,000 calls, chats, and texts in February, the highest monthly contact volume of its 25-year history. The Gazette spoke with Marianna Yang, lecturer on law and clinical instructor at the Family and Domestic Violence Law Clinic at WilmerHale Legal Services Center of Harvard Law School, about the crisis. The interview was edited for clarity and length.

Marianna Yang

GAZETTE: The most recent statistics about domestic violence during the pandemic are worrisome. What do those numbers mean?

YANG: In 2021, the United Nations published the report “Measuring the Shadow Pandemic: Violence Against Women During COVID-19.” It said that since the pandemic, violence against women has increased to unprecedented levels. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine said that domestic violence cases increased by 25 to 33 percent globally. The National Commission on COVID-19 and criminal justice shows an increase in the U.S. by a little over 8 percent, following the imposition of lockdown orders during 2020. I don’t have anything more specific for Massachusetts, but there is no reason to believe that we are any different from the rest. Domestic violence is prevalent everywhere.

According to all statistics I have seen from 2020-2021, domestic violence and intimate partner violence during the pandemic has increased because the risk factors have increased with lockdowns and pandemic restrictions.

GAZETTE: What role did the pandemic play in the rise of risk factors for domestic violence?

YANG: The increase in numbers really shows that there are unintended consequences to some of the lockdowns recommended by global health experts to address the pandemic. There are good reasons for lockdowns to protect public health, but we have to recognize the collateral and unintended impacts as well. That’s not to say that we should not have lockdowns, but there must be more focus on the resources to address those secondary impacts as well. A lockdown increases the risk factors for domestic violence in multiple ways: there are more financial stressors because of income loss due to unemployment; there is also the loss of the ability to have breathing spaces for people who are in risky relationships. When people are working outside the home, interactions with their partner are limited to certain hours of the day, and the potential time for conflict is also limited. In a lockdown, not only do you take away those breathing spaces, but you also increase the dynamics where domestic violence can occur. Also, beyond that, during a lockdown, the ability to get help is limited because you don’t have the private space to call somebody; you’re isolated from your support system as a victim/survivor, and you can’t access your family and friends, the people that you rely on. In all those facets and all those ways, the risk goes up for violence.

“There are good reasons for lockdowns to protect public health, but we have to recognize the collateral and unintended impacts as well.”

GAZETTE: How did the reporting of domestic violence incidents fluctuate during the pandemic?

YANG: I do know that at the very beginning of the pandemic, the number of calls into hotlines were showing a decrease, but that didn’t mean that suddenly domestic violence was declining. It meant that the opportunities to have a safe space to call or ask for help were limited. As the restrictions were relaxed a bit, we saw an increase in the calls for help, but they could also mean that the situation might have escalated to a point where it would push someone to make calls they otherwise would not have before the pandemic.

Generally speaking, domestic violence and intimate partner violence are underreported, and that was before and during the pandemic. There are plenty of folks who, for many good reasons, do not reach out for help. Before the pandemic, there were two hashtags — #WhyIStayed, #WhyILeft — which helped facilitate discussions around many of the reasons why people decide to stay or leave.

GAZETTE: In which other ways were domestic violence victims affected by the pandemic?

YANG: I don’t have direct access to information about shelters during the pandemic. I’m sure they remained open for the current residents, but I don’t know whether they were accepting new residents. What I do know is that judges were less likely to grant motions like Motions to Vacate the Marital Home due to the pandemic restrictions. Although this didn’t happen in any of my cases, there were anecdotes about judges being much less willing to consider those motions because of the inability of anyone to leave the house and go somewhere else. But in situations where there is clear violence, and the plaintiff can show imminent physical safety issues, judges must first and foremost consider the safety aspects of the plaintiff seeking a protective order. Judges handled restraining orders during the pandemic as emergency petitions, and the courts were open for those, but everything had to be remote and remote on a dime. There were situations where it was more difficult to provide evidence because documents or affidavits were usually filed with the court and had to be filed in person. There were gaps in the court’s systems during the pandemic, and understandably so, but that doesn’t lessen the impact and hardships that the victims had to endure.

GAZETTE: How did the pandemic impact the services provided by the Family Law and Domestic Violence Clinic at HLS?

YANG: By the time domestic violence victims get to us, it’s several steps removed. The clinic has a partnership with the Passageway program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, which provides services directly to domestic violence clients, including safety planning. My understanding is that they’ve faced an increased number of clients seeking their assistance. Those who needed to seek restraining orders and address issues through the probate and family courts were referred to us to the extent that we could access the courts. Because of the court’s closures, we provided increased levels of consultation and education around the law for when the clients could make a legal move.

Now that the courts are open again, what we’re noticing, especially in the courts that we’re practicing in, is that things are getting delayed a lot longer than they used to. Even if people can go to court, getting motions in a divorce case or getting custody and child support issues heard in front of a judge has taken months longer. Before the pandemic, it took about 30 days for motion to be heard. These days, it takes two weeks or more just to get motions docketed and then another 30 or 60 days, if not more, after that. We’re seeing a lot of chaos in terms of the workings of some of the courts; there are files that go missing and pro se litigants [those representing themselves] needing to get in front of the judges can’t get through the bureaucracy of the courts.

The biggest hurdle has been the bureaucratic aspects of getting in front of a judge. Minimizing that delay is now a much bigger part of our advocacy. We also need more legal aid and pro bono lawyers who understand that people who are in domestic violence situations are going through trauma. One of the best ways to support victims of domestic violence is to offer trauma-informed lawyering, which is another way to holistically support a client going through a difficult situation.

Share this article

You might like.

Educators, activists explore peacebuilding based on shared desires for ‘freedom and equality and independence’ at Weatherhead panel

Former Palestinian Authority prime minister says strengthening execution of 1993 accords could lead to two-state solution

Political philosopher Harvey C. Mansfield says it all goes back to Aristotle, balance of competing ideas about common good

College accepts 1,937 to Class of 2028

Students represent 94 countries, all 50 states

Pushing back on DEI ‘orthodoxy’

Panelists support diversity efforts but worry that current model is too narrow, denying institutions the benefit of other voices, ideas

So what exactly makes Taylor Swift so great?

Experts weigh in on pop superstar's cultural and financial impact as her tours and albums continue to break records.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in B - History of Economic Thought, Methodology, and Heterodox Approaches

- Browse content in B2 - History of Economic Thought since 1925

- B21 - Microeconomics

- B22 - Macroeconomics

- Browse content in C - Mathematical and Quantitative Methods

- Browse content in C1 - Econometric and Statistical Methods and Methodology: General

- C10 - General

- C14 - Semiparametric and Nonparametric Methods: General

- Browse content in C2 - Single Equation Models; Single Variables

- C23 - Panel Data Models; Spatio-temporal Models

- C25 - Discrete Regression and Qualitative Choice Models; Discrete Regressors; Proportions; Probabilities

- Browse content in C5 - Econometric Modeling

- C50 - General

- C52 - Model Evaluation, Validation, and Selection

- Browse content in C7 - Game Theory and Bargaining Theory

- C70 - General

- C72 - Noncooperative Games

- C78 - Bargaining Theory; Matching Theory

- Browse content in C9 - Design of Experiments

- C91 - Laboratory, Individual Behavior

- C92 - Laboratory, Group Behavior

- Browse content in D - Microeconomics

- Browse content in D0 - General

- D01 - Microeconomic Behavior: Underlying Principles

- D02 - Institutions: Design, Formation, Operations, and Impact

- D03 - Behavioral Microeconomics: Underlying Principles

- Browse content in D1 - Household Behavior and Family Economics

- D11 - Consumer Economics: Theory

- D12 - Consumer Economics: Empirical Analysis

- D14 - Household Saving; Personal Finance

- D18 - Consumer Protection

- Browse content in D2 - Production and Organizations

- D21 - Firm Behavior: Theory

- D22 - Firm Behavior: Empirical Analysis

- D23 - Organizational Behavior; Transaction Costs; Property Rights

- Browse content in D3 - Distribution

- D30 - General

- D31 - Personal Income, Wealth, and Their Distributions

- Browse content in D4 - Market Structure, Pricing, and Design

- D40 - General

- D42 - Monopoly

- D43 - Oligopoly and Other Forms of Market Imperfection

- Browse content in D6 - Welfare Economics

- D60 - General

- D61 - Allocative Efficiency; Cost-Benefit Analysis

- D62 - Externalities

- D63 - Equity, Justice, Inequality, and Other Normative Criteria and Measurement

- Browse content in D7 - Analysis of Collective Decision-Making

- D70 - General

- D71 - Social Choice; Clubs; Committees; Associations

- D72 - Political Processes: Rent-seeking, Lobbying, Elections, Legislatures, and Voting Behavior

- D73 - Bureaucracy; Administrative Processes in Public Organizations; Corruption

- D74 - Conflict; Conflict Resolution; Alliances; Revolutions

- D78 - Positive Analysis of Policy Formulation and Implementation

- Browse content in D8 - Information, Knowledge, and Uncertainty

- D80 - General

- D81 - Criteria for Decision-Making under Risk and Uncertainty

- D82 - Asymmetric and Private Information; Mechanism Design

- D83 - Search; Learning; Information and Knowledge; Communication; Belief; Unawareness

- D86 - Economics of Contract: Theory

- Browse content in D9 - Micro-Based Behavioral Economics

- D91 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making

- Browse content in E - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Browse content in E0 - General

- E00 - General

- E02 - Institutions and the Macroeconomy

- Browse content in E1 - General Aggregative Models

- E12 - Keynes; Keynesian; Post-Keynesian

- Browse content in E2 - Consumption, Saving, Production, Investment, Labor Markets, and Informal Economy

- E24 - Employment; Unemployment; Wages; Intergenerational Income Distribution; Aggregate Human Capital; Aggregate Labor Productivity

- Browse content in E5 - Monetary Policy, Central Banking, and the Supply of Money and Credit

- E51 - Money Supply; Credit; Money Multipliers

- Browse content in F - International Economics

- Browse content in F1 - Trade

- F10 - General

- F13 - Trade Policy; International Trade Organizations

- F18 - Trade and Environment

- Browse content in F2 - International Factor Movements and International Business

- F22 - International Migration

- Browse content in F3 - International Finance

- F34 - International Lending and Debt Problems

- Browse content in F5 - International Relations, National Security, and International Political Economy

- F53 - International Agreements and Observance; International Organizations

- F55 - International Institutional Arrangements

- Browse content in G - Financial Economics

- Browse content in G0 - General

- G01 - Financial Crises

- Browse content in G1 - General Financial Markets

- G12 - Asset Pricing; Trading volume; Bond Interest Rates

- G14 - Information and Market Efficiency; Event Studies; Insider Trading

- G18 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G2 - Financial Institutions and Services

- G21 - Banks; Depository Institutions; Micro Finance Institutions; Mortgages

- G24 - Investment Banking; Venture Capital; Brokerage; Ratings and Ratings Agencies

- G28 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G3 - Corporate Finance and Governance

- G31 - Capital Budgeting; Fixed Investment and Inventory Studies; Capacity

- G32 - Financing Policy; Financial Risk and Risk Management; Capital and Ownership Structure; Value of Firms; Goodwill

- G34 - Mergers; Acquisitions; Restructuring; Corporate Governance

- G38 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in H - Public Economics

- Browse content in H0 - General

- H00 - General

- Browse content in H1 - Structure and Scope of Government

- H10 - General

- H11 - Structure, Scope, and Performance of Government

- Browse content in H2 - Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H20 - General

- H23 - Externalities; Redistributive Effects; Environmental Taxes and Subsidies

- H24 - Personal Income and Other Nonbusiness Taxes and Subsidies; includes inheritance and gift taxes

- Browse content in H3 - Fiscal Policies and Behavior of Economic Agents

- H31 - Household

- Browse content in H4 - Publicly Provided Goods

- H40 - General

- H41 - Public Goods

- Browse content in H5 - National Government Expenditures and Related Policies

- H51 - Government Expenditures and Health

- Browse content in H6 - National Budget, Deficit, and Debt

- H63 - Debt; Debt Management; Sovereign Debt

- Browse content in H7 - State and Local Government; Intergovernmental Relations

- H70 - General

- H71 - State and Local Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H72 - State and Local Budget and Expenditures

- H73 - Interjurisdictional Differentials and Their Effects

- H74 - State and Local Borrowing

- H75 - State and Local Government: Health; Education; Welfare; Public Pensions

- H76 - State and Local Government: Other Expenditure Categories

- Browse content in H8 - Miscellaneous Issues

- H81 - Governmental Loans; Loan Guarantees; Credits; Grants; Bailouts

- H82 - Governmental Property

- Browse content in I - Health, Education, and Welfare

- Browse content in I1 - Health

- I10 - General

- I11 - Analysis of Health Care Markets

- I12 - Health Behavior

- I13 - Health Insurance, Public and Private

- I18 - Government Policy; Regulation; Public Health

- Browse content in I2 - Education and Research Institutions

- I21 - Analysis of Education

- I28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in I3 - Welfare, Well-Being, and Poverty

- I38 - Government Policy; Provision and Effects of Welfare Programs

- Browse content in J - Labor and Demographic Economics

- Browse content in J0 - General

- J00 - General

- Browse content in J1 - Demographic Economics

- J12 - Marriage; Marital Dissolution; Family Structure; Domestic Abuse

- J13 - Fertility; Family Planning; Child Care; Children; Youth

- J15 - Economics of Minorities, Races, Indigenous Peoples, and Immigrants; Non-labor Discrimination

- J18 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J2 - Demand and Supply of Labor

- J22 - Time Allocation and Labor Supply

- J28 - Safety; Job Satisfaction; Related Public Policy

- Browse content in J3 - Wages, Compensation, and Labor Costs

- J30 - General

- J31 - Wage Level and Structure; Wage Differentials

- J32 - Nonwage Labor Costs and Benefits; Retirement Plans; Private Pensions

- J33 - Compensation Packages; Payment Methods

- J38 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J4 - Particular Labor Markets

- J41 - Labor Contracts

- J45 - Public Sector Labor Markets

- J48 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J6 - Mobility, Unemployment, Vacancies, and Immigrant Workers

- J61 - Geographic Labor Mobility; Immigrant Workers

- J62 - Job, Occupational, and Intergenerational Mobility

- Browse content in J7 - Labor Discrimination

- J71 - Discrimination

- J78 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J8 - Labor Standards: National and International

- J81 - Working Conditions

- J83 - Workers' Rights

- J88 - Public Policy

- Browse content in K - Law and Economics

- Browse content in K0 - General

- K00 - General

- Browse content in K1 - Basic Areas of Law

- K10 - General

- K11 - Property Law

- K12 - Contract Law

- K13 - Tort Law and Product Liability; Forensic Economics

- K14 - Criminal Law

- K19 - Other

- Browse content in K2 - Regulation and Business Law

- K20 - General

- K21 - Antitrust Law

- K22 - Business and Securities Law

- K23 - Regulated Industries and Administrative Law

- Browse content in K3 - Other Substantive Areas of Law

- K30 - General

- K31 - Labor Law

- K32 - Environmental, Health, and Safety Law

- K34 - Tax Law

- K35 - Personal Bankruptcy Law

- K36 - Family and Personal Law

- Browse content in K4 - Legal Procedure, the Legal System, and Illegal Behavior

- K40 - General

- K41 - Litigation Process

- K42 - Illegal Behavior and the Enforcement of Law

- K49 - Other

- Browse content in L - Industrial Organization

- Browse content in L1 - Market Structure, Firm Strategy, and Market Performance

- L11 - Production, Pricing, and Market Structure; Size Distribution of Firms

- L12 - Monopoly; Monopolization Strategies

- L13 - Oligopoly and Other Imperfect Markets

- L14 - Transactional Relationships; Contracts and Reputation; Networks

- L15 - Information and Product Quality; Standardization and Compatibility

- Browse content in L2 - Firm Objectives, Organization, and Behavior

- L22 - Firm Organization and Market Structure

- L24 - Contracting Out; Joint Ventures; Technology Licensing

- Browse content in L3 - Nonprofit Organizations and Public Enterprise

- L38 - Public Policy

- Browse content in L4 - Antitrust Issues and Policies

- L40 - General

- L42 - Vertical Restraints; Resale Price Maintenance; Quantity Discounts

- L49 - Other

- Browse content in L5 - Regulation and Industrial Policy

- L51 - Economics of Regulation

- Browse content in L8 - Industry Studies: Services

- L83 - Sports; Gambling; Recreation; Tourism

- Browse content in L9 - Industry Studies: Transportation and Utilities

- L91 - Transportation: General

- L96 - Telecommunications

- Browse content in M - Business Administration and Business Economics; Marketing; Accounting; Personnel Economics

- Browse content in M1 - Business Administration

- M13 - New Firms; Startups

- Browse content in M4 - Accounting and Auditing

- M42 - Auditing

- M48 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in M5 - Personnel Economics

- M50 - General

- M52 - Compensation and Compensation Methods and Their Effects

- Browse content in N - Economic History

- Browse content in N1 - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics; Industrial Structure; Growth; Fluctuations

- N11 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913

- Browse content in N4 - Government, War, Law, International Relations, and Regulation

- N40 - General, International, or Comparative

- N41 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913

- N42 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N43 - Europe: Pre-1913

- Browse content in N5 - Agriculture, Natural Resources, Environment, and Extractive Industries

- N53 - Europe: Pre-1913

- Browse content in O - Economic Development, Innovation, Technological Change, and Growth

- Browse content in O1 - Economic Development

- O13 - Agriculture; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Other Primary Products

- Browse content in O3 - Innovation; Research and Development; Technological Change; Intellectual Property Rights

- O31 - Innovation and Invention: Processes and Incentives

- O34 - Intellectual Property and Intellectual Capital

- Browse content in P - Economic Systems

- P4 - Other Economic Systems

- P5 - Comparative Economic Systems

- Browse content in Q - Agricultural and Natural Resource Economics; Environmental and Ecological Economics

- Browse content in Q1 - Agriculture

- Q15 - Land Ownership and Tenure; Land Reform; Land Use; Irrigation; Agriculture and Environment

- Browse content in Q3 - Nonrenewable Resources and Conservation

- Q30 - General

- Browse content in Q5 - Environmental Economics

- Q53 - Air Pollution; Water Pollution; Noise; Hazardous Waste; Solid Waste; Recycling

- Browse content in R - Urban, Rural, Regional, Real Estate, and Transportation Economics

- Browse content in R1 - General Regional Economics

- R10 - General

- R11 - Regional Economic Activity: Growth, Development, Environmental Issues, and Changes

- R14 - Land Use Patterns

- Browse content in R2 - Household Analysis

- R21 - Housing Demand

- R23 - Regional Migration; Regional Labor Markets; Population; Neighborhood Characteristics

- Browse content in R3 - Real Estate Markets, Spatial Production Analysis, and Firm Location

- R31 - Housing Supply and Markets

- R38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R5 - Regional Government Analysis

- R50 - General

- R52 - Land Use and Other Regulations

- R58 - Regional Development Planning and Policy

- Browse content in Z - Other Special Topics

- Browse content in Z1 - Cultural Economics; Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology

- Z12 - Religion

- Z13 - Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology; Social and Economic Stratification

- Z18 - Public Policy

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Books for Review

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About American Law and Economics Review

- About the American Law and Economics Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction, 2. data and summary statistics, 3. the impact of lockdown on domestic violence, 3. the impact of lockdown on the extensive versus intensive margin of domestic violence, 5. conclusion, acknowledgement, supplementary material.

- < Previous

The Impact of the Coronavirus Lockdown on Domestic Violence

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Justin McCrary, Sarath Sanga, The Impact of the Coronavirus Lockdown on Domestic Violence, American Law and Economics Review , Volume 23, Issue 1, Spring 2021, Pages 137–163, https://doi.org/10.1093/aler/ahab003

- Permissions Icon Permissions

We use 911 call records and mobile device location data to study the impact of the coronavirus lockdown on domestic violence. The percent of people at home sharply increased at all hours, and nearly doubled during regular working hours, from 45% to 85%. Domestic violence increased 12% on average and 20% during working hours. Using neighborhood-level identifiers, we show that the rate of first-time abuse likely increased even more: 16% on average and 23% during working hours. Our results contribute to an urgent need to quantify the physical and psychological burdens of prolonged lockdown policies.

In this article, we examine the impact of the coronavirus lockdown on domestic violence. In response to the coronavirus pandemic, nearly all U.S. states issued stay-at-home orders designed to restrict the movement of people. 1 The anticipated public-health benefit of these policies was to arrest the spread of Covid-19 and lower the peak resource use of health care and emergency services. But these policies came at considerable cost. The economic costs of lost GDP and mass unemployment are large, well-measured, and well-understood. Much less understood, however, are the physical, psychological, and emotional costs of lockdown—of which domestic violence is one tragically common example. 2 These costs are difficult to quantify and unlikely to be reflected in standard economic measures of welfare ( Stevenson and Wolfers, 2009 ). To evaluate the true social cost of ongoing lockdown policies, it is therefore crucial to account for these sources of harm. 3

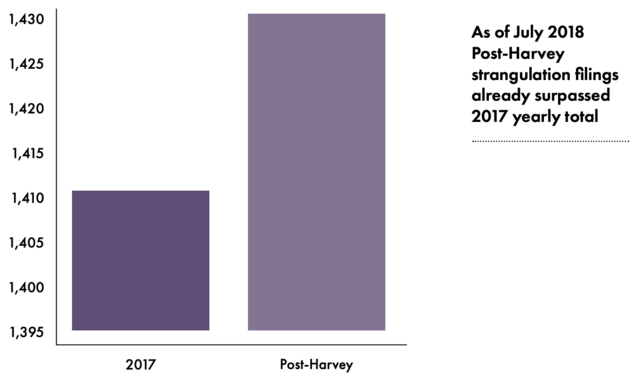

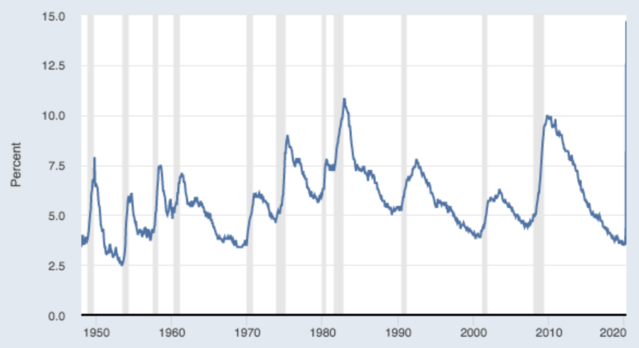

We quantify the impact of lockdown on domestic violence by assembling a database of approximately 50 million 911 call records from 14 large U.S. cities. We also obtain mobile device location data from these same cities. Together, these data allow us to study the impacts of lockdown on at-home patterns and domestic violence. We find that both increased sharply during lockdown ( Figures 1 and 2 ). Domestic violence calls increased throughout mid-March and peaked in early April. By the end of April, domestic violence calls returned to pre-lockdown levels. At the same time, the number of people at home also abruptly increased but stayed high throughout April. The largest increases in both at-home patterns and domestic violence occurred during weekday daytime hours, when most adults would have otherwise been at work and most children would have been in school.

The impact of lockdown on being at home.

The fraction of mobile devices at home at 12 p.m. each day (a proxy for the fraction of people at home) for the sample of 14 U.S. cities listed in Table 1 .

The impact of lockdown on domestic violence.

The average daily number of domestic violence 911 calls in the sample of 14 U.S. cities listed in Table 1 .

While the surge in domestic violence appears to have been temporary, there are at least two reasons to suspect that the harms will be long-lasting. The first reason comes from the long-lasting nature of physical and psychological trauma. While economies can recover from large, even catastrophic, shocks, people may not be so resilient. Children who suffer or witness abuse also suffer a range of psychological, behavioral, and academic problems throughout their lives. 4 The harms from domestic violence will therefore persist well after lockdowns end. The second reason is that violence begets violence. Inasmuch as domestic violence is state dependent, in the sense used by Heckman (1981) , exposure to violence today increases the likelihood of violence tomorrow, and temporary surges in abuse will lead to a permanent increase in long-run levels. 5

While we cannot directly estimate state dependence or the long-run impact of lockdown, we nevertheless begin to address these issues by asking whether lockdown caused people to commit abuse for the first time. The impacts of lockdown could be especially persistent if the surge in domestic violence came from households without a history of violence, or put another way, if it caused an increase on the extensive margin of domestic violence. This is because any state dependence would then act as a multiplier, causing those households to experience more violence in the future.

To estimate changes on the extensive margin, we construct neighborhood identifiers using address records attached to each 911 call. (City authorities anonymize the address to the level of about half of one city block.) We then show how the neighborhood-level data can provide a close approximation of the percentage change in the household-level extensive margin, as well as an upper bound on the household-level intensive margin. Applying our procedures to the data, we find that the impact on the extensive margin was at least twice as large as the impact on the intensive margin: 16% on the extensive margin versus an upper bound of 8% on the intensive margin. Lockdown therefore had larger impact, in percentage terms, on households without a history of domestic violence. To the extent that domestic violence is state dependent, we conclude that the temporary surge will lead to a permanent increase.

The surge in domestic violence in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic and lockdown has been documented across scores of countries. See, for example, Perez-Vincent et al. (2020) (Argentina); Sifat (2020) (Bangladesh); Das et al. (2020) and Ravindran and Shah (2020) (India); Dahal et al. (2020) (Nepal); Calderon-Anyosa and Kaufman (2020) (Peru); Sediri et al. (2020) (Tunisia); Leslie and Wilson (2020) and Boserup et al. (2020) (United States); Javed and Mehmood (2020) (various countries)—among many others. The closest study to ours is perhaps Leslie and Wilson (2020) , which also studies the U.S. context. Virtually all studies demonstrate that domestic violence significantly increased in the post-lockdown period.

Our study provides three unique contributions to this literature: (1) we assemble the largest sample of 911 calls for service (14 U.S. cities that constitute |$\sim$| 5% of the U.S. population); (2) we provide the first credible estimate of the extent to which increased time spent at home is responsible for the surge in domestic violence (specifically, an upper bound on this estimate); and (3) we theoretically motivate and demonstrate how neighborhood-level data can be used to separately identify bounds on changes in the household-level extensive and intensive margins of domestic violence.

Two caveats are in order. First, we use the term “lockdown” as a catchall for the total disruption caused by the pandemic and subsequent suspension of regular economic and social interaction. We do so with the understanding that the pandemic and the myriad public and private responses to it likely affected domestic violence through a variety of channels. In our view, it is likely that the surge in domestic violence did not come from sheltering in place per se—that is, only from spending more time at home—but rather from spending more time at home under the uniquely stressful conditions created by the pandemic. The most straightforward reason comes from Figures 1 and 2 , which show that simply being at home under lockdown was not sufficient to sustain an increase in domestic violence: domestic violence call volumes rose with the number of people at home, but then dropped significantly throughout April even as the number of people at home remained constant.

The second caveat is that our conclusions on changes in domestic violence are based on reported incidents that result in a 911 call. Since most incidents of domestic abuse do not result in a 911 call, the data are subject to considerable reporting bias. Moreover, reporting bias may have increased or decreased during lockdown. If domestic violence incidents were less likely to be reported during lockdown, then our results would underestimate the change in domestic violence. 6 Indeed, lockdown made it much more difficult to leave the house and go to a shelter or stay with a friend. A victim unable to leave the house might reasonably conclude that involving the police would make matters worse. Even more troubling, the return to pre-lockdown domestic violence levels could reflect additional increases in reporting bias as lockdown wore on. 7 Nevertheless, the reporting bias inherent in our study is, relative to a typical empirical study of crime, straightforward to characterize. A typical study might use crimes reported by law enforcement authorities, and therefore be subject to the reporting bias of victims, witnesses, and police. In contrast, we use 911 calls, which are typically placed by victims or witnesses. Any reporting bias would thus come directly from the victims and witnesses themselves.

The article is organized as follows. Section 2 summarizes the 911 call records and mobile device location data. Section 3 reports the main results. Section 3 reports estimates of the response to lockdown on the extensive and intensive margins of domestic violence. Section 5 concludes.

Our analysis combines two sources of data. The first source is 911 call records for police service from 14 large U.S. cities. The second source is mobile device location histories from those same cities. This section briefly summarizes both sources of data. Additional details on data construction can be found in the Supplementary Appendix .

2.1. Calls for Police Service

We obtained records of about 52 million 911 calls for police service, of which about 6.3 million were placed during the main sample period of January 1, 2020 through April 24, 2020 ( Table 1 ). The records come from 14 cities (or more precisely, 13 cities and 1 county) with a collective population of about 17 million people. Depending on the city, there are anywhere between 2 and 15 years of call records. The records are complete for each city beginning January 1 of the starting year listed in Table 1 and running through April 24, 2020.

911 Calls for Police Service

Notes . Neighborhoods is the total number of unique locations from which a domestic violence call originated. The geographic origin of each call is known up to the 100-block level. For example, “303 Main St” and “340 Main St” would both be recorded as originating from the same neighborhood (“300 Block of Main St”). The origin of domestic violence calls is not known for Los Angeles, Seattle, and Sacramento. Population comes from the 2019 U.S. Census estimates.

Out of the 52 million 911 calls, approximately 1.6 million (3%) are domestic violence-related. To determine whether a call was domestic violence-related, we tabulated the short textual descriptions that accompany each record, separately for each city, and manually read them to identify domestic violence-related descriptors. This process yielded 291 unique domestic violence-related descriptors across the 14 cities. 8

The domestic violence calls come from 116,809 distinct neighborhoods. We constructed these neighborhoods from the call records by analyzing the “origin of call” information attached to each record. For 11 of the 14 cities, each call record includes information about the geographic origin of the call. 9 The addresses in the call records are typically anonymized to the 100-level address block. For example, the locations “310 Chicago Ave,” “319 Chicago Ave,” and “375 Chicago Ave” would all be recorded as “300 Block Chicago Ave.” Some cities also use intersections to record locations (e.g. “Chicago Ave / State St”). We standardize these addresses to ensure consistency within a city and then use them to define unique neighborhood identifiers. Each neighborhood is thus about half of one city block or smaller.

Domestic violence calls exhibit strong seasonality ( Figure 3 ). In general, call volumes increase linearly from the beginning of the calendar year, peak in early and late summer, and then linearly decline throughout the rest of the year. Four calendar days also stand out as outliers: July 4, July 5, and December 25 each exceed average domestic violence call levels by more than 20%, while January 1 exceeds the average level by more than 40%.

The seasonality of domestic violence 911 calls.

This figure shows that the seasonality of domestic violence 911 calls is, in years before lockdown, continuous throughout the pre- and post-lockdown period. Each dot is the average number of domestic violence 911 calls on that calendar day divided by the average number of domestic violence 911 calls (across all days). The sample is domestic violence 911 calls from all cities for all calendar days except February 29 and all years except 2020. The vertical line at March 14 indicates the start of the lockdown period in 2020.

Importantly, however, the seasonal trend is stable throughout the period we study: It is roughly linear and continuous during the weeks before and after the calendar day of March 14 (which, for reasons explained below, is the day we use to mark the beginning of lockdown). In the regression analysis, we will use simple linear and quadratic trends to account for seasonality.

Domestic violence calls increased sharply in the weeks following lockdown. Figure 2 plots the average daily call volume in 2020. The average call volume follows the usual linear trend up to the week ending on March 13. It then sharply rises throughout lockdown and peaks in early April. By the end of April, the call volume declines to the level predicted by the pre-lockdown linear trend.

2.2. Mobile Device Location Data

The mobile device location data are a daily cross-sectional sample of mobile devices physically located within the 14 cities in our sample. The sample ranges from approximately 1.3 to 1.8 million devices per day, which is roughly one-tenth the size of the total population of the cities they represent. The data provider identifies a mobile device as being “at home” by comparing its current location to its history of nighttime locations for the past 6 weeks. 10 The mobile device location data are available beginning January 1, 2020.

Figure 1 plots our estimate of the fraction of people at home at 12 p.m. each day. The fraction at home on weekdays nearly doubled in mid-March, from about 45% to 85%. For weekends, the increase was smaller but similarly abrupt. The largest increase occurred on March 14. For this reason, we will use that day—March 14, 2020—to define the beginning of lockdown.

Since not everyone is at home during the early morning hours, our estimator of the fraction at home is biased upwards. To get a sense of the potential scale of this bias, suppose the maximum number of people at home occurs at 3 a.m. If the true fraction of people at home at 3 a.m. is 0.95, and the true fraction at home at 12 p.m. is 0.5, then our estimate at 3 a.m. would be biased upward by 5 percentage points ( |$= 95/95 - 95$| ) and our estimate at 12 p.m. would be biased upward by 3 percentage points ( |$\approx 50/0.95 - 50$| ).

More importantly, this procedure may also underestimate the change in the fraction at home caused by lockdown. Consider the change in at-home patterns on weekdays at 12 p.m. From Figure 1 , the fraction at home increased 40 percentage points (from 0.45 to 0.85). If lockdown caused the maximum fraction at home to increase from, say, 0.95 to 0.99, then the true change on weekdays at 12 p.m. would have been 41 percentage points (from 0.43 to 0.84). The bias for the weekday daytime change is therefore likely small. On the other hand, and continuing the example from above, suppose the maximum fraction at home always occurs at 3 a.m. Then the true change at 3 a.m. would be 4% (95–99), but our procedure would normalize this to zero by construction. In percentage terms, the scale of the downward bias is therefore modest for the main daytime estimates (where the percentage point charges are large), but potentially significant for the nighttime estimates (where the percentage point changes are small). We will keep this bias in mind when interpreting the results below.

3.1. Baseline Results

Our baseline estimate of the increase in domestic violence caused by lockdown is 12% ( Table 2 , panel A). The estimate is similar (13%) even without controls for hour of day, day of week, or seasonal trends. Because lockdown had the greatest impact in at-home patterns during working hours, we separately estimate equation 2 for periods defined by the interaction of daytime (9 a.m.–9 p.m.) and weekday (Monday–Friday). The largest increase occurred during daytime hours: 20% for weekdays and 17% for weekends. The nighttime increase was 9% for weekdays and less than 1% for weekends. The latter estimate is not statistically significantly different from zero at conventional levels of confidence.

The Impact of Lockdown on At-Home Patterns and Domestic Violence

Notes . All panels use 911 call records and/or mobile device location data from January 2, 2020–April 24, 2020. The unit of observation is the day-hour. Lockdown is an indicator equal to 1 if the day is March 14–April 24, inclusive. * and ** indicate statistically significantly different from zero at 95 and 99 percent confidence, respectively. (A) The impact of lockdown on the log number of domestic violence 911 calls. (B) The impact of lockdown on the log number of people at home. (C). An upper bound on the effect of being at home on domestic violence; the number of people at home is instrumented using the lockdown period.

3.2. The Effect of Increased Time Spent At Home

Since lockdown forced people to stay at home, it is natural to ask whether the impact of lockdown on domestic violence is, in percentage terms, equal to the impact of lockdown on at-home patterns (i.e. whether the elasticity of domestic violence with respect to people at home is equal to one). Further, it is also natural to ask whether the differential impacts we observe throughout the week are consistent with a constant-elasticity model.

Nevertheless, |$\gamma_1$| has two related and useful interpretations. Firstly, and as a matter of arithmetic, |$\gamma_1$| is the ratio of two causal effects: it is the reduced-form effect of lockdown on domestic violence ( |$\beta_1$| from equation 2 ) divided by the first-stage effect of lockdown on being at home ( |$\pi_1$| from equation 4 ). It therefore provides one way to scale the reduced-form estimates and compare the differential impacts of lockdown throughout the hours of the week. For example, if |$\gamma_1$| were, say, 0.40, then we would conclude that the impact of lockdown on domestic violence was 40% of its impact on being at home.

The second and related interpretation of |$\gamma_1$| is that, under plausible assumptions, it is an upper bound on the causal effect of being at home on domestic violence. To see this, recall that lockdown is not a valid instrument for being at home because it likely violates the “only through” assumption: lockdown caused more people to stay home, but it also caused economic and psychological distress that in turn may have directly affected rates of domestic violence. Yet suppose one partitions the impacts of lockdown on domestic violence into two channels: the first, which we will call the mechanical effect of lockdown, is the true effect of more people at home on domestic violence. The second, which we will call the collateral effects of lockdown, is the sum of all other nonmechanical influences of lockdown on domestic violence. The collateral effects include any channel—any economic or psychological stress—that increased the rate of domestic violence per person-hour at home. We refer to this set of effects as “collateral” because they were clearly not the intended effects of stay-at-home orders, private self-isolation, layoffs, and all the other public and private responses to the pandemic. If one assumes that the collateral effects jointly led to a net increase in domestic violence, then |$\gamma_1$| is an upper bound on the mechanical effect because it attributes the entire change in domestic violence to the change in time spent at home. Put another way, |$\gamma_1$| is the mechanical effect under the (invalid) assumption that lockdown increased domestic violence “only through” its increase on the number of people at home.

Moving to the estimates, panel B of Table 2 reports results from the first stage: the effect of lockdown on the number of people at home. As one might expect, the largest increase in at-home patterns occurred during regular working hours. The number of people at home for all hours increased 14 percent. The increase during daytime, however, was 32% for weekdays and 13% for weekends. The increases during nighttime were much smaller: 5% for weekdays and less than 1% in magnitude for weekends. It is worth noting, however, that the nighttime weekend estimate includes the hour-of-day and quadratic time trend. Without these controls, the simple post-lockdown difference is 2% and statistically significant.

For nighttime hours, there are two reasons to prefer the simple difference estimates without controls. First, as explained in Section 2 , the upward bias inherent in our estimate of the number of people at home, while small in terms of percentage point differences, increases in percent age differences as the fraction of people at home goes to 1. This could lead us to underestimate the change in at-home patterns, especially for the early morning hours. On the other hand, and partially mitigating the magnitude of this potentially large bias, the change in at-home patterns is substantial during many of the hours that are included in the nighttime estimates, specifically, during the hours between 7 a.m.–9 a.m. and 9 p.m.–11 p.m. Second, the change in at-home patterns at night are likely small to begin with, as most people are probably asleep during at least half the hours between 9 p.m. and 9 a.m. The extrapolation of any pre-lockdown trend could therefore overwhelm these small differences, leading to a zero (or even negative) estimate ( Bound et al., 1995 ). For these reasons, we interpret the nighttime first- and second-stage estimates with caution, as the first-stage estimate may be biased downward. At the same time, however, one may be more confident in interpreting the daytime estimates because the impact of the two concerns outlined above is likely to be much smaller.

Moving to the second-stage estimates ( Table 2 , panel C), the upper bound on the elasticity of domestic violence with respect to people at home is 0.85 (column 2). Thus, in percentage terms, the total change in domestic violence was 85% of the total change in at-home patterns. We fail to reject the null hypothesis that the elasticity is equal to 1, using both a basic |$t$| -test and the more accurate Anderson and Rubin (1949) test. 11

With full controls, the daytime estimates of |$\gamma_1$| are 0.62 for weekdays and 1.29 for weekends. Relative to the change in at-home patterns, the increase in domestic violence during weekday daytime hours, while larger in absolute terms, is thus smaller than the increase during weekend daytime hours. The difference in these estimates is statistically significant at conventional levels ( |$p=0.02$| , column 4 versus column 6). 12

In summary, the results provide evidence against a simple proportional model. While we cannot reject the simple proportional model on average (column 2), we can reject equality of the proportions during daytime hours for weekdays versus weekends (columns 4 versus 6). We conclude that the lockdown-associated surge in domestic violence likely reflects a mixture of causal channels more complex than the simple mechanical increase in the number of people at home.

Finally, we ask whether the surge in domestic violence came from households with or without a history of domestic violence. To answer this question, one could use a panel of individual- or household-level data to estimate the impact of lockdown on the extensive versus intensive margin. The change in households without prior domestic violence calls would be the change in the extensive margin, while the change in households with prior domestic violence calls would be the change in the intensive margin. Unfortunately, the 911 call data do not include an individual or household identifier. They do include, however, addresses that were coarsened to the level of about one half of one city block, which we use to construct neighborhood-level identifiers. In this section, we show how the neighborhood-level data can provide an approximation of the change in the extensive margin of domestic violence, as well as an upper bound for the change in the intensive margin.

4.1. Theoretical framework

We begin by defining the extensive and intensive margins of domestic violence. We will say that a call occurs on the extensive margin if it is the first call for that household since period |$t=0$| , for some start date normalized to zero. Otherwise, the call occurs on the intensive margin.

It is worth pausing here to clarify the role that the “start date” plays in both the theoretical model and the empirical application. In principle, the first “true” extensive margin event for a given household is the first time that the household places a 911 call. Given household-level data, the ideal start date would therefore be the date that the household was formed. However, this is not feasible in our setting because the call data are at the neighborhood level. It is for this reason that we redefine the first extensive margin event as the first call since a given start date , and then show (in Appendix Section A ) how changes in the (redefined) neighborhood margins can identify changes in the (redefined) household margins. Thus, the interpretation of the results depends on the specific choice of start date. Since the exact choice of start date is arbitrary, the empirical section repeats the analysis for a variety of start dates.

As noted, a limitation of our data is that it identifies calls at a neighborhood level, but not a household level. However, neighborhood level data contain valuable information for the intensive–extensive breakdown of our results. An increase in calls from a neighborhood with no history of calls can only occur on the extensive margin. An increase in calls from a neighborhood with a history of calls, on the other hand, could come from either the intensive or extensive margin, and therefore represents a mixture of the two. Appendix Section A develops the implications of this intuition. Letting |$\sim$| denote neighborhood-level quantities, Appendix Section A shows that |$\widetilde{\eta}$| is a reasonable approximation of |$\eta$| and that |$\widetilde{\varepsilon}$| is a bound (upper or lower, depending on |$\eta$| ) on |$\varepsilon$| .

In practice, it may be that the impact of lockdown on the extensive margin differs by neighborhood. In that case, our estimate of |$\eta$| is valid for the households in neighborhoods with low rates of domestic violence. Note that a neighborhood-level rate can be low either because the rates of its constituent households are low, or because there are simply few households in the neighborhood.

4.2. Results

The change in the extensive margin is |$\phi_1$| , and the bound on the change in the intensive margin is |$\psi_1$| .

As a baseline, we use 18 months before the lockdown period (September 14, 2018) as the start date to define the extensive and intensive margins. A domestic violence 911 call thus contributes to the extensive margin if it is the first neighborhood-level call since September 14, 2018. Otherwise, it contributes to the intensive margin. In addition, since the functional form approximations from equations 10 and 11 hold only when |$t$| is sufficiently large relative to |$\theta$| ( when one is sufficiently far from the start date that defines both margins), we only use observations beginning 150 days after the start date to estimate both equations. The approximations appear to be valid about 150 days after the start date, at which point the extensive margin is roughly linear and the intensive margin is roughly constant ( figure 4 ). Finally, since the choice of start date and estimation window is arbitrary, we also produce estimates for other start dates and estimation windows.

The impact of lockdown on (a) the extensive margin and (b) the intensive margin of domestic violence (Monday–Friday, 9 a.m.–9 p.m.).

A call is on the extensive margin if it is the first call from that neighborhood since September 14, 2018 (18 months before lockdown begins). Otherwise, the call is on the intensive margin.

The impact on the extensive margin is consistently larger than the (upper) bound of the impact on the intensive margin. Table 3 reports estimates using the start date September 14, 2018 and commencing estimation 150 days later. The change in the extensive margin is larger on average (16 percent versus 8 percent) as well as for each of the sub-periods during the week. During daytime, the increase was 23 versus 14 percent for weekdays, and 25 versus 10 percent for weekends. During nighttime, the changes were smaller: 12 versus 6 percent for weekdays, and 1 versus -1 for weekends. (The latter result is not statistically significant.) Given that our estimate of the intensive margin change is an upper bound, these results suggest that the percentage change in the extensive margin is roughly twice as large (or more) than the change in the intensive margin.

The Impact of Lockdown on Domestic Violence (Extensive versus Intensive Margins)

Notes. This table estimates the impact of lockdown on the log number of domestic violence 911 calls for the extensive and intensive margins. A call is on the extensive margin if it is the first call from that neighborhood since September 14, 2018 (18 months before lockdown beings). Otherwise, the call is on the intensive margin. Lockdown begins March 14, 2020. * and ** indicate statistically significantly different from zero at 95% and 99% confidence, respectively.

Finally, the main result – that the impact on the extensive margin was greater than the impact on the intensive margin – is robust to a variety of start dates and estimation windows. Specifically, it is robust to using start dates between 12 and 24 months before lockdown, and estimation windows that begin 120, 150, and 180 days after the start date. In theory, one might prefer the earlier start dates as they are more likely to capture a household’s true first domestic violence call (and thus reflect the true change in the extensive margin). On the other hand, an earlier start date allows more time for household and neighborhood turnover to bias the estimates in unknown directions. In table 3 , we chose 18 months before lockdown as an (admittedly arbitrary) balance between these two concerns. Somewhat reassuringly, however, estimates of changes on the extensive margin are fairly stable, particularly for start dates that are 18 months or more before lockdown. 14

We used 911 calls for police service to study the impact of the coronavirus lockdown on domestic violence. Domestic violence calls surged in the weeks following lockdown, from mid-March to early-April, and returned to pre-lockdown levels by the end of April. The largest increases occurred during weekday daytime hours, when most adults and children would have otherwise been at work or in school. Using mobile device location data, we found that these hours also experienced the greatest disruption in at-home patterns. Lockdown is especially likely to have led to episodes of first-time abuse: the increase from neighborhoods with no recent history of violence was roughly double the increase from neighborhoods with a recent history of violence.

Our results are important for evaluating the total social cost of prolonged lockdown policies. Compared to the economic costs of lost GDP and unemployment, the physical and psychological costs of lockdown are much more difficult to observe and quantify. They are, however, just as important contributors to welfare.

We thank Bernard Black, Vandy Howell, Katherine Litvak, Max Schanzenbach, David Schwartz, Eric Talley, Kimberly Yuracko, and seminar participants at Northwestern University for helpful comments.

A. Technical Appendix

This appendix section formally shows how we use neighborhood-level data to identify household-level changes on the extensive and intensive margins.

As an estimate of |$\eta$| , |$\widetilde{\eta}$| has a second-order downward bias, a third-order upward bias, a fourth-order downward bias, and so on. The net bias is downward, and the magnitude increases with |$\eta$| , |$n$| , and |$\theta$| . For plausible values of |$\eta$| , |$n$| , and |$\theta$| , however, the bias is negligible. The order of magnitude of the bias is roughly |$\theta\cdot n$| . In neighborhoods without recent calls, it is likely that the typical household call rate is well below average. Nevertheless, using the conservatively high level of the average daily call rate from the data (about 0.00004) and a neighborhood size of 25, a household-level |$\eta$| of 1.5 would yield a neighborhood-level |$\widetilde{\eta}$| of approximately 1.4996. A neighborhood of 250 would be 1.4963. % (1-(1-x*y)^n) / (1-(1-x)^n) for x=.00004, y=1.5, n=250

Supplementary material is available at American Law and Economics Review Journal online.

To the best of our knowledge, Arkansas, Iowa, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota did not issue state-level orders. Our sample of 911 call records does not cover any of these states.

On the psychological costs of domestic violence, see generally, Russell (1990) , White and Koss (1991) , Balsam and Szymanski (2005) , Truman and Morgan (2014) , and Golding (1999) .

This is especially urgent as subsequent waves of the virus—and potentially additional lockdown orders—are expected in the medium term.

See Edleson (1999) , Kilpatrick and Williams (1997) , Truman and Morgan (2014) , and Snyder et al. (2016) .

Repeat-victimization in domestic violence is a fundamental concern for law enforcement authorities. See, e.g., Hanmer et al. (1999) .

Perhaps the strongest evidence of increased reporting bias comes from widespread reports of an increased reluctance to contact emergency medical services for both covid-19 and non-covid-19 reasons, as well as the related increase in at-home deaths. At-home deaths spiked 4-fold in Detroit and 6-fold in New York City ( Gillum et al., 2020 ).

See, e.g., Ott (2020) .

A list of these descriptors is given in the Supplementary Appendix .

The origin of domestic violence calls is not known for Los Angeles, Seattle, and Sacramento.

The data were provided by SafeGraph. See the Supplementary Appendix for additional details.

The |$p$| -value for the Anderson and Rubin (1949) test is |$p=0.29$| (column 2). Generally for columns 1 through 6, the first-stage relationship is strong enough that there is little difference between an asymptotic |$t$| -test and an Anderson and Rubin (1949) test. However, for the results without controls (column 1), we reject the null that the elasticity is equal to 1 using either approach.

However, without controls, the estimates are much more similar (0.52 for weekdays, 0.61 for weekends). Given the sampling variability of each estimate, it is perhaps not surprising that the data suggest little difference between the two estimates ( |$p=0.60$| , column 3 versus column 5).

In our simple model, |$\psi_2\approx 0$| for sufficiently large |$t$| . See section A . Also, the estimates below do not include Detroit because data are not available before January 1, 2019. Similar results are obtained when one restricts the start dates to January 1, 2019 and later. (Results not shown.)

See the Supplementary Appendix .

The average daily call rate is about 3–5 per 100,000.

This is without loss of generality given sufficiently small |$\theta$| .

Anderson, Theodore W. , and Rubin Herman . 1949 . “ Estimation of the Parameters of a Single Equation in a Complete System of Stochastic Equations ,” 20 The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 46 – 63 .

Google Scholar

Balsam, Kimberly F. , and Szymanski Dawn M. . 2005 . “ Relationship Quality and Domestic Violence in Women’s Same-Sex Relationships: The Role of Minority Stress ,” 29 Psychology of Women Quarterly 258 – 269 .

Boserup, Brad , McKenney Mark , and Elkbuli Adel . 2020 . “ Alarming Trends in US Domestic Violence during the COVID-19 Pandemic ,” 38 The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2753 – 2755 .

Bound, John , Jaeger David A. , and Baker Regina M. . 1995 . “ Problems With Instrumental Variables Estimation When the Correlation Between the Instruments and the Endogenous Explanatory Variable is Weak ,” 90 Journal of the American Statistical Association 443 – 450 .

Calderon-Anyosa, Renzo J. C. , and Kaufman Jay S. . 2020 . “ Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown Policy on Homicide, Suicide, and Motor Vehicle Deaths in Peru ,” 143 Preventive Medicine 106331 .

Dahal, Minakshi , Khanal Pratik , Maharjan Sajana , Panthi Bindu , and Nepal Sushil . 2020 . “ Mitigating Violence against Women and Young Girls during COVID-19 Induced Lockdown in Nepal: A Wake-up Call ,” 16 Globalization and Health 1 – 3 .

Das, Manob , Das Arijit , and Mandal Ashis . 2020 . “ Examining the Impact of Lockdown (Due to COVID-19) on Domestic Violence (DV): An Evidences from India ,” 54 Asian Journal of Psychiatry 102335 .

Edleson, Jeffrey L . 1999 . “ Children’s Witnessing of Adult Domestic Violence ,” 14 Journal of Interpersonal Violence 839 – 870 .

Gillum, Jack , Song Lisa , and Kao Jeff . 2020 . “ There’s Been a Spike in People Dying at Home in Several Cities. That Suggests Coronavirus Deaths Are Higher Than Reported ,” ProPublica April 14 , 2020 .

Golding, Jacqueline M . 1999 . “ Intimate Partner Violence as a Risk Factor for Mental Disorders: A Meta-Analysis ,” 14 Journal of Family Violence 99 – 132 .

Hanmer, Jalna , Griffiths Sue , and Jerwood David . 1999 . Arresting Evidence: Domestic Violence and Repeat Victimisation , Vol. 104 . Home Office London .

Google Preview

Heckman, James J . 1981 . “Heterogeneity and State Dependence” in Rosen Sherwin , ed., Studies in Labor Markets . Chicago, IL : University of Chicago Press , pp. 91 – 140 .

Javed, Saira , and Mehmood Yasir . 2020 . “ No Lockdown for Domestic Violence during COVID-19: A Systematic Review for the Implication of Mental-Well Being ,” 1 Life and Science 6 .

Kilpatrick, Kym L. , and Williams Leanne M. . 1997 . “ Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in Child Witnesses to Domestic Violence ,” 67 American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 639 .

Leslie, Emily , and Wilson Riley . 2020 . “ Sheltering in Place and Domestic Violence: Evidence from Calls for Service during COVID-19 ,” 189 Journal of Public Economics 104241 .

Ott, Haley . 2020 . “ In Countries Mired in Crises, Aid Organization Sees Huge Drop in Domestic Abuse Reports – and It’s Worried ,” CBS News .

Perez-Vincent, Santiago M. , Carreras Enrique , Gibbons M. Amelia , Murphy M. Amelia , and Rossi Martín A. 2020 . COVID-19 Lockdowns and Domestic Violence . Washington, DC, USA : Inter-American Development Bank .

Ravindran, Saravana , and Shah Manisha . 2020 . “ Unintended Consequences of Lockdowns: Covid-19 and the Shadow Pandemic ,” Technical Report , National Bureau of Economic Research .

Russell, Diana E. H. 1990 . Rape in Marriage . Bloomington, IN : Indiana University Press .

Sediri, Sabrine , Zgueb Yosra , Ouanes Sami , Ouali Uta , Bourgou Soumaya , Jomli Rabaa , and Nacef Fethi , 2020 . “ Women’s Mental Health: Acute Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Domestic Violence ,” 23 Archives of Women’s Mental Health 749 – 756 .

Sifat, Ridwan Islam . 2020 . “ Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Domestic Violence in Bangladesh ,” 53 Asian Journal of Psychiatry 102393 .

Snyder, James , Gewirtz Abigail , Schrepferman Lynn , Gird Suzanne R , Quattlebaum Jamie , Pauldine Michael R. , Elish Katie , Zamir Osnat , and Hayes Charles . 2016 . “ Parent–Child Relationship Quality and Family Transmission of Parent Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms and Child Externalizing and Internalizing Symptoms Following Fathers’ Exposure to Combat Trauma ,” 28 Development and Psychopathology 947 – 969 .

Stevenson, Betsey , and Wolfers Justin . 2009 . “ The Paradox of Declining Female Happiness ,” 1 American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 190 – 225 .

Truman, Jennifer L. , and Morgan Rachel E. . 2014 . “ Nonfatal Domestic Violence, 2003–2012 ,” Technical Report , Washington, D.C .

White, Jacquelyn W. , and Koss Mary P. . 1991 . “ Courtship Violence: Incidence in a National Sample of Higher Education Students ,” 6 Violence and Victims , 247 .

Supplementary data

Email alerts, citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1465-7260

- Print ISSN 1465-7252

- Copyright © 2024 American Law and Economics Association

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Violence against women and girls: the shadow pandemic

Date: Monday, 6 April 2020

With 90 countries in lockdown, four billion people are now sheltering at home from the global contagion of COVID-19. It’s a protective measure, but it brings another deadly danger. We see a shadow pandemic growing, of violence against women .

COVID-19: Women front and centre

As more countries report infection and lockdown, more domestic violence helplines and shelters across the world are reporting rising calls for help. In Argentina, Canada, France, Germany, Spain, the United Kingdom [ 1 ], and the United States [ 2 ], government authorities, women’s rights activists and civil society partners have flagged increasing reports of domestic violence during the crisis, and heightened demand for emergency shelter [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Helplines in Singapore [ 6 ] and Cyprus have registered an increase in calls by more than 30 per cent [ 7 ]. In Australia, 40 per cent of frontline workers in a New South Wales survey reported increased requests for help with violence that was escalating in intensity [ 8 ].

Confinement is fostering the tension and strain created by security, health, and money worries.And it is increasing isolation for women with violent partners, separating them from the people and resources that can best help them. It’s a perfect storm for controlling, violent behaviour behind closed doors. And in parallel, as health systems are stretching to breaking point, domestic violence shelters are also reaching capacity, a service deficit made worse when centres are repurposed for additional COVID-response.

Even before COVID-19 existed, domestic violence was already one of the greatest human rights violations. In the previous 12 months, 243 million women and girls (aged 15-49) across the world have been subjected to sexual or physical violence by an intimate partner. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, this number is likely to grow with multiple impacts on women’s wellbeing, their sexual and reproductive health, their mental health, and their ability to participate and lead in the recovery of our societies and economy.

Wide under-reporting of domestic and other forms of violence has previously made response and data gathering a challenge, with less than 40 per cent of women who experience violence seeking help of any sort or reporting the crime. Less than 10 per cent of those women seeking help go to the police. The current circumstances make reporting even harder, including limitations on women’s and girls’ access to phones and helplines and disrupted public services like police, justice and social services. These disruptions may also be compromising the care and support that survivors need, like clinical management of rape, and mental health and psycho-social support. They also fuel impunity for the perpetrators. In many countries the law is not on women’s side; 1 in 4 countries have no laws specifically protecting women from domestic violence.

Gender-Based Violence and COVID-19 - UN chief video message

If not dealt with, this shadow pandemic will also add to the economic impact of COVID-19. The global cost of violence against women had previously been estimated at approximately USD 1.5 trillion. That figure can only be rising as violence increases now, and continues in the aftermath of the pandemic.

The increase in violence against women must be dealt with urgently with measures embedded in economic support and stimulus packages that meet the gravity and scale of the challenge and reflect the needs of women who face multiple forms of discrimination.The Secretary-General has called for all governments to make the prevention and redress of violence against women a key part of their national response plans for COVID-19. Shelters and helplines for women must be considered an essential service for every country with specific funding and broad efforts made to increase awareness about their availability.

Grassroots and women’s organizations and communities have played a critical role in preventing and responding to previous crises and need to be supported strongly in their current frontline role including with funding that remains in the longer-term. Helplines, psychosocial support and online counselling should be boosted, using technology-based solutions such as SMS, online tools and networks to expand social support, and to reach women with no access to phones or internet. Police and justice services must mobilize to ensure that incidents of violence against women and girls are given high priority with no impunity for perpetrators. The private sector also has an important role to play, sharing information, alerting staff to the facts and the dangers of domestic violence and encouraging positive steps like sharing care responsibilities at home.

COVID-19 is already testing us in ways most of us have never previously experienced, providing emotional and economic shocks that we are struggling to rise above. The violence that is emerging now as a dark feature of this pandemic is a mirror and a challenge to our values, our resilience and shared humanity. We must not only survive the coronavirus, but emerge renewed, with women as a powerful force at the centre of recovery.

Related content

- COVID-19 and ending violence against women and girls

- Infographic: The Shadow Pandemic - Violence Against Women and Girls and COVID-19

[1] “Coronavirus: I'm in lockdown with my abuser” https://www.bbc.com/news/world-52063755 , accessed 3 rd April 2020

[2] “Domestic violence cases escalating quicker in time of COVID-19” https://missionlocal.org/2020/03/for-victims-of-domestic-violence-sheltering-in-place-can-mean-more-abuse , accessed 3 rd April

[3] Lockdowns around the world bring rise in domestic violence” https://www.theguardian. com/society/2020/mar/28/lockdowns-world-rise-domestic-violence , accessed 3 rd April 2020

[4] "Domestic violence cases jump 30% during lockdown in France” https://www.euronews.com/2020/03/28/domestic-violence-cases-jump-30-during-lockdown-in-france , accessed 3 rd April 2020

[5] “During quarantine, calls to 144 for gender violence increased by 25%” http://www.diario21.tv/notix2/movil2/?seccion=desarrollo_nota&id_nota=132124 ), accessed 2 nd April 2020

[6] “Commentary: Isolated with your abuser? Why family violence seems to be on the rise during COVID-19 outbreak”, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/commentary/coronavirus-covid-19-family-violence-abuse-women-self-isolation-12575026 , accessed 2 nd April 2020

[7] “Lockdowns around the world bring rise in domestic violence” https://www.theguardian. com/society/2020/mar/28/lockdowns-world-rise-domestic-violence , accessed 3 rd April 2020

[8] “Domestic Violence Spikes During Coronavirus As Families Trapped At Home” https://10daily.com.au/news/australia/a200326zyjkh/domestic-violence-spikes-during-coronavirus-as-families-trapped-at-home-20200327 , accessed 2 nd April 2020

- ‘One Woman’ – The UN Women song

- UN Under-Secretary-General and UN Women Executive Director Sima Bahous

- Kirsi Madi, Deputy Executive Director for Resource Management, Sustainability and Partnerships

- Nyaradzayi Gumbonzvanda, Deputy Executive Director for Normative Support, UN System Coordination and Programme Results

- Guiding documents

- Report wrongdoing

- Programme implementation

- Career opportunities

- Application and recruitment process

- Meet our people

- Internship programme

- Procurement principles

- Gender-responsive procurement

- Doing business with UN Women

- How to become a UN Women vendor

- Contract templates and general conditions of contract

- Vendor protest procedure

- Facts and Figures

- Global norms and standards

- Women’s movements

- Parliaments and local governance

- Constitutions and legal reform

- Preguntas frecuentes

- Global Norms and Standards

- Macroeconomic policies and social protection

- Sustainable Development and Climate Change

- Rural women

- Employment and migration

- Facts and figures

- Creating safe public spaces

- Spotlight Initiative

- Essential services

- Focusing on prevention

- Research and data

- Other areas of work

- UNiTE campaign

- Conflict prevention and resolution

- Building and sustaining peace

- Young women in peace and security

- Rule of law: Justice and security

- Women, peace, and security in the work of the UN Security Council

- Preventing violent extremism and countering terrorism

- Planning and monitoring

- Humanitarian coordination

- Crisis response and recovery

- Disaster risk reduction

- Inclusive National Planning

- Public Sector Reform

- Tracking Investments

- Strengthening young women's leadership

- Economic empowerment and skills development for young women

- Action on ending violence against young women and girls

- Engaging boys and young men in gender equality

- Sustainable development agenda

- Leadership and Participation

- National Planning

- Violence against Women

- Access to Justice

- Regional and country offices

- Regional and Country Offices

- Liaison offices

- UN Women Global Innovation Coalition for Change

- Commission on the Status of Women

- Economic and Social Council

- General Assembly

- Security Council

- High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development

- Human Rights Council

- Climate change and the environment

- Other Intergovernmental Processes

- World Conferences on Women

- Global Coordination

- Regional and country coordination

- Promoting UN accountability

- Gender Mainstreaming

- Coordination resources

- UN Coordination Library

- System-wide strategy

- Focal Point for Women and Gender Focal Points

- Entity-specific implementation plans on gender parity

- Laws and policies

- Strategies and tools

- Reports and monitoring

- Training Centre services

- Publications

- Government partners

- National mechanisms

- Civil Society Advisory Groups

- Benefits of partnering with UN Women

- Business and philanthropic partners

- Goodwill Ambassadors

- National Committees

- UN Women Media Compact

- UN Women Alumni Association

- Editorial series

- Media contacts

- Annual report

- Progress of the world’s women

- SDG monitoring report

- World survey on the role of women in development

- Reprint permissions

- Secretariat

- 2023 sessions and other meetings

- 2022 sessions and other meetings

- 2021 sessions and other meetings

- 2020 sessions and other meetings

- 2019 sessions and other meetings

- 2018 sessions and other meetings

- 2017 sessions and other meetings

- 2016 sessions and other meetings

- 2015 sessions and other meetings

- Compendiums of decisions