A Summary and Analysis of Martin Luther King’s ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’ is Martin Luther King’s most famous written text, and rivals his most celebrated speech, ‘ I Have a Dream ’, for its political importance and rhetorical power.

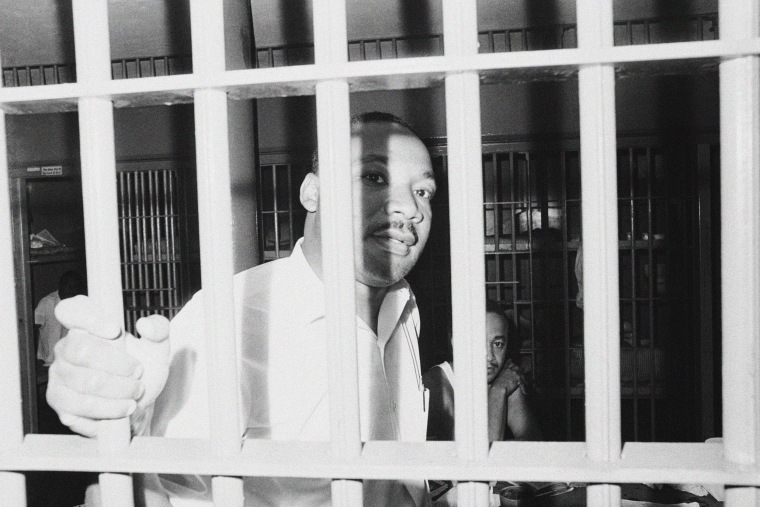

King wrote this open letter in April 1963 while he was imprisoned in the city jail in Birmingham, Alabama. When he read a statement issued in the newspaper by eight of his fellow clergymen, King began to compose his response, initially writing it in the margins of the newspaper article itself.

In ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’, King answers some of the criticisms he had received from the clergymen in their statement, and makes the case for nonviolent action to bring about an end to racial segregation in the South. You can read the letter in full here if you would like to read King’s words before reading on to our summary of his argument, and analysis of the letter’s meaning and significance.

‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’: summary

The letter is dated 16 April 1963. King begins by addressing his ‘fellow clergymen’ who wrote the statement published in the newspaper. In this statement, they had criticised King’s political activities ‘unwise and untimely’. King announces that he will respond to their criticisms because he believes they are ‘men of genuine good will’.

King outlines why he is in Birmingham: as president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, he was invited by an affiliate group in Birmingham to engage in a non-violent direct-action program: he accepted. When the time came, he honoured his promise and came to Birmingham to support the action.

But there is a bigger reason for his travelling to Birmingham: because injustice is found there, and, in a famous line, King asserts: ‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.’ The kind of direction action King and others have engaged in around Birmingham is a last resort because negotiations have broken down and promises have been broken.

When there is no alternative, direct action – such as sit-ins and marches – can create what King calls a ‘tension’ which will mean that a community which previously refused to negotiate will be forced to come to the negotiating table. King likens this to the ‘tension’ in the individual human mind which Socrates, the great classical philosopher, fostered through his teachings.

Next, King addresses the accusation that the action he and others are taking in Birmingham is ‘untimely’. King points out that the newly elected mayor of the city, like the previous incumbent, is in favour of racial segregation and thus wishes to preserve the political status quo so far as race is concerned. As King observes, privileged people seldom give up their privileges voluntarily: hence the need for nonviolent pressure.

King now turns to the question of law-breaking. How can he and others justify breaking the law? He quotes St. Augustine, who said that ‘an unjust law is no law at all.’ A just law uplifts human personality and is consistent with the moral law and God’s law. An unjust law degrades human personality and contradicts the moral law (and God’s law). Because segregation encourages one group of people to view themselves as superior to another group, it is unjust.

He also asserts that he believes the greatest stumbling-block to progress is not the far-right white supremacist but the ‘white moderate’ who are wedded to the idea of ‘order’ in the belief that order is inherently right. King points out both in the Bible (the story of Shadrach and the fiery furnace ) and in America’s own colonial history (the Boston Tea Party ) people have practised a form of ‘civil disobedience’, breaking one set of laws because a higher law was at stake.

King addresses the objection that his actions, whilst nonviolent themselves, may encourage others to commit violence in his name. He rejects this argument, pointing out that this kind of logic (if such it can be called) can be extended to all sorts of scenarios. Do we blame a man who is robbed because his possession of wealth led the robber to steal from him?

The next criticism which King addresses is the notion that he is an extremist. He contrasts his nonviolent approach with that of other African-American movements in the US, namely the black nationalist movements which view the white man as the devil. King points out that he has tried to steer a path between extremists on either side, but he is still labelled an ‘extremist’.

He decides to own the label, and points out that Jesus could be regarded as an ‘extremist’ because, out of step with the worldview of his time, he championed love of one’s enemies.

Other religious figures, as well as American political figures such as Abraham Lincoln and Thomas Jefferson, might be called ‘extremists’ for their unorthodox views (for their time). Jefferson, for example, was considered an extremist for arguing, in the opening words to the Declaration of Independence, that all men are created equal. ‘Extremism’ doesn’t have to mean one is a violent revolutionary: it can simply denote extreme views that one holds.

King expresses his disappointment with the white church for failing to stand with him and other nonviolent activists campaigning for an end to racial segregation. People in the church have made a variety of excuses for not supporting racial integration.

The early Christian church was much more prepared to fight for what it believed to be right, but it has grown weak and complacent. Rather than being disturbers of the peace, many Christians are now upholders of the status quo.

Martin Luther King concludes his letter by arguing that he and his fellow civil rights activists will achieve their freedom, because the goal of America as a nation has always been freedom, going back to the founding of the United States almost two centuries earlier. He provides several examples of the quiet courage shown by those who had engaged in nonviolent protest in the South.

‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’: analysis

Martin Luther King’s open letter written from Birmingham Jail is one of the most famous open letters in the world. It is also a well-known defence of the notion of civil disobedience, or refusing to obey laws which are immoral or unjust, often through peaceful protest and collective action.

King answers each of the clergymen’s objections in turn, laying out his argument in calm, rational, but rhetorically brilliant prose. The emphasis throughout is non nonviolent action, or peaceful protest, which King favours rather than violent acts such as rioting (which, he points out, will alienate many Americans who might otherwise support the cause for racial integration).

In this, Martin Luther King was greatly influenced by the example of Mahatma Gandhi , who had led the Indian struggle for independence earlier in the twentieth century, advocating for nonviolent resistance to British rule in India. Another inspiration for King was Henry David Thoreau, whose 1849 essay ‘ Civil Disobedience ’ called for ordinary citizens to refuse to obey laws which they consider unjust.

This question of what is a ‘just’ law and what is an ‘unjust’ law is central to King’s defence of his political approach as laid out in the letter from Birmingham Jail. He points out that everything Hitler did in Germany in the 1930s and 1940s was ‘legal’, because the Nazis changed the laws to suit their ideology and political aims. But this does not mean that what they did was moral : quite the opposite.

Similarly, it would have been ‘illegal’ to come to the aid of a Jew in Nazi Germany, but King states that he would have done so, even though, by helping and comforting a Jewish person, he would have been breaking the law. So instead of the view that ‘law’ and ‘justice’ are synonymous, ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’ is a powerful argument for obeying a higher moral law rather than manmade laws which suit those in power.

But ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’ is also notable for the thoughtful and often surprising things King does with his detractors’ arguments. For instance, where we might expect him to object to being called an ‘extremist’, he embraces the label, observing that some of the most pious and peaceful figures in history have been ‘extremists’ of one kind of another. But they have called for extreme love, justice, and tolerance, rather than extreme hate, division, or violence.

Similarly, King identifies white moderates as being more dangerous to progress than white nationalists, because they believe in ‘order’ rather than ‘justice’ and thus they can sound rational and sympathetic even as they stand in the way of racial integration and civil rights. As with the ‘extremist’ label, King’s position here may take us by surprise, but he backs up his argument carefully and provides clear reasons for his stance.

There are two main frames of reference in the letter. One is Christian examples: Jesus, St. Paul, and Amos, the Old Testament prophet , are all mentioned, with King drawing parallels between their actions and those of the civil rights activists participating in direct action.

The other is examples from American history: Abraham Lincoln (who issued the Emancipation Proclamation during the American Civil War, a century before King was writing) and Thomas Jefferson (who drafted the words to the Declaration of Independence, including the statement that all men are created equal).

Both Christianity and America have personal significance for King, who was a reverend as well as a political campaigner and activist. But these frames of reference also establish a common ground between both him and the clergymen he addresses, and, more widely, with many other Americans who will read the open letter.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

LAW AND RELIGION FORUM

Martin luther king on just and unjust laws.

Today is Martin Luther King Day in the United States. In commemoration, here’s a passage from Dr. King’s famous Letter from a Birmingham Jail , which he wrote in 1963 to answer clergy who had criticized his willingness to break laws as part of his anti-segregation campaign:

You express a great deal of anxiety over our willingness to break laws. This is certainly a legitimate concern. Since we so diligently urge people to obey the Supreme Court’s decision of 1954 outlawing segregation in the public schools, at first glance it may seem rather paradoxical for us consciously to break laws. One may well ask: “How can you advocate breaking some laws and obeying others?” The answer lies in the fact that there are two types of laws: just and unjust. I would be the first to advocate obeying just laws. One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws. I would agree with St. Augustine that “an unjust law is no law at all.”

Now, what is the difference between the two? How does one determine whether a law is just or unjust? A just law is a man made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God. An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law. To put it in the terms of St. Thomas Aquinas: An unjust law is a human law that is not rooted in eternal law and natural law. Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust. All segregation statutes are unjust because segregation distorts the soul and damages the personality. It gives the segregator a false sense of superiority and the segregated a false sense of inferiority. Segregation, to use the terminology of the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber, substitutes an “I it” relationship for an “I thou” relationship and ends up relegating persons to the status of things. Hence segregation is not only politically, economically and sociologically unsound, it is morally wrong and sinful. Paul Tillich has said that sin is separation. Is not segregation an existential expression of man’s tragic separation, his awful estrangement, his terrible sinfulness? Thus it is that I can urge men to obey the 1954 decision of the Supreme Court, for it is morally right; and I can urge them to disobey segregation ordinances, for they are morally wrong.

Let us consider a more concrete example of just and unjust laws. An unjust law is a code that a numerical or power majority group compels a minority group to obey but does not make binding on itself. This is difference made legal. By the same token, a just law is a code that a majority compels a minority to follow and that it is willing to follow itself. This is sameness made legal. Let me give another explanation. A law is unjust if it is inflicted on a minority that, as a result of being denied the right to vote, had no part in enacting or devising the law. Who can say that the legislature of Alabama which set up that state’s segregation laws was democratically elected? Throughout Alabama all sorts of devious methods are used to prevent Negroes from becoming registered voters, and there are some counties in which, even though Negroes constitute a majority of the population, not a single Negro is registered. Can any law enacted under such circumstances be considered democratically structured?

Sometimes a law is just on its face and unjust in its application. For instance, I have been arrested on a charge of parading without a permit. Now, there is nothing wrong in having an ordinance which requires a permit for a parade. But such an ordinance becomes unjust when it is used to maintain segregation and to deny citizens the First-Amendment privilege of peaceful assembly and protest.

The King Center has a link to the original publication, here .

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from law and religion forum.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

MLK disobeyed unjust laws. The state of America today requires that we not forget that.

Martin Luther King Jr. is a symbol of peace, justice and nonviolence, but he is often misquoted, misunderstood and invoked for nefarious purposes that have nothing to do with his legacy. While many like to speak of King's "dream" and his commitment to peace, part of remembering him means understanding his belief that society has a responsibility to disobey unjust laws. And right now in America, we have become the land of unjust laws and policies — from voter suppression to bans on teaching race and racism.

In his “ Letter from Birmingham Jail ,” King said we have a duty to disobey unjust laws. "I would be the first to advocate obeying just laws. One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws," he wrote. "Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws. I would agree with St. Augustine that 'an unjust law is no law at all.'"

King was unwavering in advocating for civil disobedience to break systems of oppression — disobeying unjust laws in the open, and with love.

What is an unjust law? According to King, it's one that degrades rather than uplifts humanity. Jim Crow segregation statutes were a prime example of unjust laws because "segregation distorts the soul and damages the personality," as King noted. "It gives the segregator a false sense of superiority and the segregated a false sense of inferiority."

A law is also unjust if a numerical majority or a power majority imposes it on a minority yet the majority does not have to follow the law. King used specific examples to make his point.

Internationally, he pointed to Germany, writing: "We should never forget that everything Adolf Hitler did in Germany was 'legal.' ... It was 'illegal' to aid and comfort a Jew in Hitler's Germany."

And, of course, sitting in a Birmingham jail cell, he spoke of how Alabama's segregation laws that prevented Black citizens from voting were put in place by an undemocratically elected state Legislature (a power majority). He pointed to the fact that not a single Black person was registered to vote even in some majority-Black counties.

While he did not advocate lawbreaking, or as he said "evading or defying the law" like the "rabid segregationist," King was unwavering in advocating for civil disobedience to break systems of oppression — disobeying unjust laws in the open, and with love. After all, he believed that those who passively accepted evil without protesting it are perpetuating it and cooperating with it.

"I submit that an individual who breaks a law that conscience tells him is unjust, and who willingly accepts the penalty of imprisonment in order to arouse the conscience of the community over its injustice, is in reality expressing the highest respect for law," King insisted.

This is a side of him that has been glossed over or even conveniently left out of the conversation. Meanwhile, there are people today who support unjust laws yet invoke King's name when it is convenient. Supporting policies that directly oppose King's dream for America, they cherry-pick his words without context to justify unjust laws.

Nothing about King’s actions or rhetoric — no matter how some may try to twist them — indicates that he would be satisfied with where America is on civil rights today.

Sens. Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz., and Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., claim to support voting rights and to celebrate King's vision and honor his legacy of freedom, justice and equality, yet they refuse to change the Senate filibuster rule that would allow for crucial voting rights legislation to pass and preserve multiracial democracy. Sinema and Manchin exemplify the white moderate King described, that "great stumbling block" against Black freedom "who is more devoted to 'order' than to justice" and believes now is not a convenient time for freedom.

In a 1963 interview, King cited the filibuster as stalling the Civil Rights Act of 1964: "I think the tragedy is that we have a Congress with a Senate that has a minority of misguided senators who will use the filibuster to keep the majority of people from even voting."

That same year at the March on Washington, King said: "I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character."

GOP lawmakers who justified, supported or enabled the Jan. 6 insurrection and appealed to white nationalists — such as Sen. Josh Hawley of Missouri, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy of California and Sen. Ron Johnson of Wisconsin — have quoted and twisted King's "I Have a Dream" speech to attack critical race theory and deny the existence of systemic racism.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis , a Republican, name-dropped King last month in announcing an anti-critical race theory bill called the Stop Woke Act. The legislation would allow private parties, such as students, parents, employees and businesses, to sue schools and workplaces that teach critical race theory. "You think about what MLK stood for," DeSantis said. "He said he didn't want people judged on the color of their skin but on the content of their character."

Opinion We want to hear what you THINK. Please submit a letter to the editor.

Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp called King "a transformational leader" and "a true American hero" who recognized "great injustice in this world" and took "the necessary steps to right that wrong." Yet Kemp sat under a painting of a slave plantation as he signed a voter suppression law making it a crime to give food and water to people waiting in line to vote.

In Texas — where the Legislature removed King from the state curriculum and ended the requirement to teach that the Ku Klux Klan was morally wrong — Sen. Ted Cruz praised King's fight against racial inequality and injustice . This is the same person who has thrown his unwavering support behind Donald Trump, a president who denigrated Black women , whose administration operated migrant detention centers that one member of Congress compared to concentration camps and who advocated for measures that contribute to voter suppression .

Now is the time to remember that King, though nonviolent, was not a pushover. People in the U.S. are witnessing how the future of the country’s multiracial democracy is at stake because of unjust laws that aim to further ostracize marginalized voices. And we shouldn’t just stand aside and watch it happen. We can use the power of our vote and our voices to hold elected officials accountable. Nothing about King’s actions or rhetoric — no matter how some may try to twist them — indicates that he would be satisfied with where America is on civil rights today.

David A. Love, a faculty member in journalism and media studies at the Rutgers University School of Communication and Information, is a writer based in Philadelphia. He writes about race, politics and justice issues.

On the Cusp of an American Civil Rights Revolution: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Final Visit and Address to San Diego in 1964

By seth mallios and breana campbell.

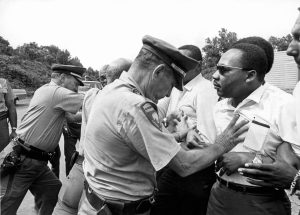

Legendary civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s last appearance in San Diego in the late spring of 1964 came at the apex of one of the most important and volatile moments in the nation’s history. Collectively, participants in the American Civil Rights movement of the early 1960s endured an onslaught of racially motivated and targeted political deceit, police brutality, and murder. Simultaneously, they inspired the rise of unprecedented social activism through non-violent civil disobedience as a means to expose racial injustice. Fewer than six weeks after King’s trip to San Diego, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson would sign the Civil Rights Act of 1964, formally outlawing discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. This time was also one of King’s most celebrated periods; during 1963-64, he gave likely the most important speech of the 20th century in August 1963, 1 was named Time magazine’s “Man of the Year” in December 1963, and would be the youngest person ever (at the age of 35) to win the Nobel Peace Prize in December 1964. Despite mammoth personal acclaim and national advancement for his primary cause—the end of segregation—King did not come to San Diego for accolades or praise; he ventured to the city as part of a statewide tour to rally California voters against Proposition 14, which was on the upcoming November (1964) state ballot. Were it to pass, this proposed law would undo California’s 1963 Rumford Act, which prohibited racial discrimination in housing.

San Diego was generally hostile to King’s social and political causes, even though the Baptist minister was already a global icon. This conservative Southern California town was especially backward when it came to civil rights, earning the nickname, “the Mississippi of the West,” 2 from George Stevens, former Chairman of San Diego’s Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and San Diego National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) president, and Dr. Carrol W. Waymon, founder of the San Diego State College Black History Department (today’s Africana Studies Department) and former Executive Director of San Diego’s Citizen’s Interracial Committee (CIC). 3 In 1964, African-Americans in San Diego were routinely turned down for loans from banks, denied housing outside of three segregated neighborhoods, 4 unable to work at companies like San Diego Gas & Electric or Woolworth’s, and refused entrance to many businesses solely because of the color of their skin. They were even prohibited from trying on clothes at department stores. King’s brief trip to California in 1964 was rife with conflict. As he flew west, his cottage in Florida was attacked by armed gunmen; during his talks in San Diego, protestors handed out fliers on site declaring that King was a communist; 5 and a few weeks after he returned home, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover told reporters that King was “the most notorious liar in the country.” 6 King faced adversity nearly everywhere he went, and San Diego was neither an exception nor a respite from near constant antagonism.

Political Background

By the late 1950s, the Democratic Party in California had largely become the state’s civil rights party. In 1958, California democrats swept the legislative elections, including a victory by democrat Edmund G. “Pat” Brown in the gubernatorial race. Together, these wins gave democrats a super-majority of over two-thirds in the state legislature, making it impossible for anti-civil rights members to block legislation. Governor Brown and the state assembly immediately made civil rights their primary agenda. By the end of 1959, they succeeded in passing the Fair Employment Protection Act (FEPA), the Unruh Civil Rights Act, and the Hawkins Act. 7 Governor Brown’s momentum carried into the 1960s as he defeated big-name Republican Richard Nixon in the 1962 election. 8 As the civil rights movement gained speed and escalated across the country, California activists successfully pushed for additional progressive reform in the state. For example, University of California, Berkeley, students participated in peaceful demonstrations against national companies that complied with Jim Crow laws or refused to hire African-Americans. In January 1963, the Berkeley City Council passed the first fair-housing ordinance in California, although this ordinance was soon after repealed in April. 9

On April 25, 1963, the California state assembly passed the California Fair Housing Act. 10 The Rumford Act, as it was more commonly known, was introduced by William Byron Rumford, a civil rights activist and the first African-American from Northern California to serve in the state legislature. This act prohibited discrimination by realtors and property owners on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, or ancestry. Discrimination against blacks and others in the housing market contributed to the growth of large concentrations of minority groups in urban areas where they often lived in unhealthy, overcrowded, and impoverished conditions. King and others knew that housing discrimination, especially in northern and western parts of the country, was a starting point for addressing broader racist practices in America; they insisted that weakening this sort of structural bigotry would successfully undermine other forms of institutionalized racism. Their cause gained momentum as the passage of the Rumford Act in California was followed by many other states passing similar anti-discriminatory civil-rights legislation at this time.

Public backlash against the Rumford Act among certain stakeholders in the state was swift. California’s Chamber of Commerce and the construction and real estate industries immediately met the law with great protest. In fact, it was at the El Cortez Hotel in San Diego on January 11, 1964, that real estate agents met to determine if the California Real Estate Association (CREA) would sponsor the proposed Proposition 14, an initiative action that would overturn the Rumford Act. 11 It sought to add an amendment to the constitution of California prohibiting state action that would hinder any person from discriminating when selling or renting a property. Protesters, many of whom were San Diego members of the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE), gathered to show their opposition for the initiative with signs that read “The Ghetto Must Go,” “Human Rights over Property Rights,” and “Housing Discrimination Must End.” Counter-protestors showed up to support Proposition 14, including members of the American Nazi Party, who carried signs stating, “The Rumford Act is Communist Backed; Treason is the Reason.” By the meeting’s end, over 1,000 directors from CREA statewide reaffirmed the racist agenda to sponsor and support the passage of Proposition 14, disguising it as an issue of state’s rights. 12 Not only did it sponsor Proposition 14, CREA funneled over $100,000 in campaign funds and extensive propaganda to ensure its victory. Proposition. 14 would be decided upon by the voters in California’s 1964 election. 13

Those rallying to uphold the Rumford Act recognized that California’s fair housing law might not survive the November 1964 election. In fact, there was a prominent counter-trend of fair-housing laws being rejected nationwide by popular referendum in 1964 and 1965. 14 As a result, numerous organizations collaborated to invite and sponsor a set of California appearances by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. His busy itinerary would include speaking with the public on the specific importance of defeating Proposition 14 and uniting this regional cause with the general significance of combatting all future legislation that impeded the desegregation of the nation. 15 King’s brief trip to California included stops in San Diego, Los Angeles, Fresno, and San Francisco with two talks scheduled at local colleges. Sponsors for these two San Diego addresses, including the San Diego State College Lectures and Concerts Board, Western Christian Leadership Conference, San Diego County Council of Churches, San Diego Ministerial Association, Associated Student Body of California Western University, and United Church Women of San Diego, hoped that King’s presence would galvanize opposition to Proposition 14 and further national causes to end lawful segregation in all of its institutionalized forms.

Martin Luther King in San Diego

There are historical discrepancies regarding the number of trips King made to San Diego and his exact itineraries during these visits. Although many local contemporaneous leaders claimed that he made only one or two trips to the city, oral histories and a spotty trail of artifacts suggest that there were three separate appearances. San Diego native, San Diego State College alumnus (Class of 1965), and famed local educator Willie Jefferson Horton, Jr. stated that he first met King in 1955 when the burgeoning civil rights leader first came to San Diego to visit Bethel Baptist Church pastor Charles H. Hampton. Hampton was a personal friend of King’s father, the Baptist minister Martin Luther King. 16 A sixth grader at the time, Horton clearly recalled his mother telling him: “Finish your homework; let’s go. This is history in the making!” 17 Horton also remembered that King came to town in an effort to raise money for the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which was fueled by the December 1, 1955, arrest of Rosa Parks. 18

King also visited San Diego five years later on February 26, 1960; on this trip he spoke at two local churches, Bethel Baptist Church and Calvary Baptist Church. Voice & Viewpoint reporter Chida Warren-Darby, insisted that this was Dr. King’s first appearance in San Diego, an assertion that Horton vehemently denies. 19 There is little doubt about King’s 1960 visit, as multiple people, including former CORE leader and San Diego County Urban League administrator Ambrose Brodus, Jr., detailed extensive personal interaction with the famed civil rights leader. Brodus recalled that he met Dr. King at Calvary Baptist Church in 1960 and emphasized how the meeting changed his life, stating that, “The man believed. Dr. King practiced what he preached, and we could see that he was determined.” 20 It is difficult to dispute his account as Brodus kept his autographed program from King’s 1960 San Diego appearance.

King returned four years later to San Diego on May 29, 1964; he arrived on a PSA “super-electric” jet that landed at Lindbergh Field. King was scheduled for two official in-town speaking engagements; one at San Diego State College (SDSC), now San Diego State University (SDSU), and a second at California Western University (Cal Western), now Point Loma Nazarene University (PLNU). Nevertheless, there is debate as to the exact events of the day. Hartwell W. Ragsdale, former president of the San Diego NAACP and prominent local businessman (owner of the Anderson Ragsdale Mortuary), recalled that he ordered a limousine to pick up King at the airport. He explained that, “Having Dr. King here had meaning to me. It was the greatest thing associated with my life.” 21 In Ragsdale’s account, the hired car then drove King to the NAACP branch headquarters at 2601 Imperial Avenue in San Diego to meet with Ragsdale and other staff members. Once there, the group discussed legislative efforts to end segregation in California and the rest of the nation. Following this meeting, Ragsdale stated that King was then escorted by NAACP members to his multiple speaking engagements and, later, driven back to Lindbergh Field to continue his speaking tour of California. Ragsdale’s son, Hartwell “Skipper” Ragsdale III, was nine years old during the visit and recalled that King “was very warm…very genuine [and] seemed to be very caring and sincere…. He spoke to me as though I was someone he was very familiar with.” 22 The younger Ragsdale was also quoted as saying that, “I remember riding around in the car with [King] and watching him. He was just an everyday regular person. Even though he was revered, he was so kind.” 23 Warren-Darby’s Voice and Viewpoint article included a photograph of King with Ragsdale.

Mary Eunice Oliver, a local civil rights activist and member of the Episcopal Human Relations Commission, provided different information about King’s 1964 visit to San Diego. She stated that her church was honored with the responsibility of attending to King during his brief visit. Oliver recalled personally escorting him from Lindbergh Field and bringing him directly from the airport to SDSC for his 2:00 p.m. speech. She also has a photograph featuring King, herself, and others at Lindbergh Field (Figures 2 and 3). Furthermore, the King Center Archive in Atlanta, Georgia, contains two correspondences confirming Oliver’s time with King; the first even mentions the Lindbergh Field pictures. Mary Eunice Oliver handwrote a letter to King on June 22, 1964, which stated:

Dear Dr. King, Due to your sacrificial witness in St. Augustine, it may be a long time before this letter will be read, yet I must write and express my gratitude for your efforts in San Diego. We felt the total program was terrific, thanks to you, and your wonderful Christian witness. God has richly blessed you with many talents, especially the peace that passes understanding, which is highlighted in everything you do, and say and are. The pictures we took at the airport are fine. Will send you copies shortly. God bless and protect you. Faithfully, Mary Eunice

King responded with a typed correspondence on June 29, 1964, that read:

Dear Mrs. Oliver, This is a rather belated note thanking you and your husband for making my recent visit to San Diego such a magnificent one. I am deeply grateful to both of you for all of the courtesies extended. The fellowship was rich indeed, and I only regret that we did not have more time together. Please extend my warm best wishes to all of the friends I had an opportunity to meet in San Diego, particularly to your lovely children. I do hope our paths will cross again in the not too distant future. May God continue to bless you and yours in all of your endeavors. Sincerely yours, Martin Luther King, Jr.

Overall, it is difficult to reconcile Ragsdale and Oliver’s conflicting narratives as they recount seemingly mutually exclusive events. Both renditions could be seen as accurate, however, if the Ragsdales’ memories refer to King’s 1960 visit. 24

The Atlanta archive also has King’s May 20, 1964, welcome letter from San Diego Board of Supervisors’ Chairman, Robert C. Dent. The tone of the correspondence was surprisingly devotional given that it came from a public administrator; it stated:

Dear Doctor King: As Chairman of the Board of Supervisors of the County of San Diego, it is my pleasure to welcome you to our County. As you are probably aware, Southern California is one of the fastest growing areas in the United States. With a continual increase in our work and problems, those of us in local government must constantly work toward the improvement of our services to the public with fairness and equity to all people. Without the Christian influence, our labors would be in vain. We are all cognizant of the necessity of applying Christian principles to attain success in all our endeavors. We are particularly indebted to leaders like you who are devoting their lives to make our world a better place in which to live. There is much work to be done but it is my belief if we all keep in mind the Christian truths upon which this Nation is founded and our responsibilities to all people as we go about our daily tasks, we can all go forward in harmony. Sincerely, Robert C. Dent

Almost as soon as King deplaned at Lindbergh Field in 1964, San Diego State College journalism professor Harold Keen interviewed him for local CBS affiliate, Channel 8. Video footage of this conversation, long thought to have been lost or destroyed, was recently discovered by KFMB producer David Gotfredson in the spring of 2014. The interview revealed dramatic details of the recent attack on King’s cottage in St. Augustine, Florida. This southern city had been at the epicenter of racial conflict for generations, and in 1964 was about to explode into widespread violence for the nation to see on television and in newspapers. St. Augustine had an especially active Ku Klux Klan (KKK) chapter and a militant NAACP leader in Dr. Robert B. Hayling, a former U.S. Air Force officer. In the spring of 1964, Hayling encouraged northern college students in St. Augustine to join in local anti-segregation social activism instead of vacationing at the beach during their school break. King and other members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) joined the cause and engaged in months of non- violent protest, resulting in numerous arrests and rampant physical abuse of activists by segregationists. 25 Keen’s poignant interview with a clearly disturbed yet defiant King, missing for 50 years and presumed lost, is reproduced here in its entirety. Keen’s questions are tough, common to 1960s journalism, and King’s answers are remarkably raw assessments of civil rights struggle, especially in his stern critique of people who had yet to take a side in this conflict.

May 29, 1964 Interview Professor Keen: Dr. King, your rented cottage in St. Augustine in Florida was hit by bullets early today. Does this indicate a new outbreak of violence in the civil rights struggle? Dr. King: Well, it does indicate that there are still recalcitrant forces alive in the South that will do anything to prevent integration. We started a strong push to desegregate facilities in that the oldest city in the United States just last Wednesday and this is a result of the violent reaction to that move. The Klan is rather strong in that area and very active, and I think this is the beginning of a reign of terror, and I have apprised President Johnson of this through a telegram that I just sent stating that several acts of terror have taken place. Some of my staff members were beaten last night. They shot in their automobiles, and then went and shot in the cottage that I had just rented for our staff for the months that we would be working there. So I think it is a critical problem and one that should call, bring about action from the federal government. Professor Keen: Dr. King, have some of the unpopular civil disobedience tactics and disorders such as the New York World’s Fair stall-in 26 indicated that responsible Negro leadership may have lost control? Dr. King: No, I don’t think at all. I think we still have the vast majority of Negroes following the lines or the methods set forth by the established organizations and the responsible leaders. I think this will continues as long as we make progress, as long as we can win concrete victories, but I must say that if these victories do not come through non-violence and if the vast majority of Negroes are not able to see definite gains, these other approaches may appeal to them more in future months. Professor Keen: You believe there’s a possibility of serious bloodshed then if this frustration is not overcome? Dr. King: Well, I hate to predict violence because I found in so many instances that the constant prediction of violence is an unconscious invitation to it, but I must be realistic. If there is not a strong move to do something about the injustices the Negroes face, if there isn’t something dramatic done, if the Civil Rights Bill does not pass with strength, I’m sure that it will show increase the discontent, the restlessness, the frustration, and the despair of the Negro that it will be much more difficult to keep the struggle disciplined and non-violent. Professor Keen: Don’t the strong showings of Governor Wallace in the primaries 27 in which he was entered show a public reaction against the civil rights movement? Dr. King: I think this is a reaction from many people who have never been committed to civil rights. I don’t think it means a setback or what some refer to as a white backlash. The fact is that many of these people have been out in the middle all along, neither pro- or anti-. Now they’re forced to face the issue in a way that they’ve never faced it before, and they find that they have many more latent prejudices, than they realize. I think the other thing in the Wallace showing that we just see is that prejudice is not just a sectional problem. It’s a national problem, and I think it may be a blessing in disguise in that it will cause people of good will to realize that much more must be done to get rid of this festering sore of segregation. Professor Keen: How do you rate the Republican candidates in California on the issue of civil rights, Governor Rockefeller and Senator Goldwater? 28 Dr. King: Now Governor Rockefeller has made it clear to the national public, and he’s made it clear to me in private conversations that I’ve had with him that he’s committed to civil rights in general and to the Civil Rights Bill in particular. He has advanced broad humanitarian concern and the Rockefeller family generally has given support to civil rights. Now Mr. Goldwater has also made his position clear. He feels that the matter of civil rights should be left to the states, and this means that you leave it to Mr. Wallace of Alabama and to Barnetts 29 and Johnsons of Mississippi, and I just don’t think this matter can be left in the hands of such racists. So I don’t think Senator Goldwater can be considered a strong man in civil rights. Professor Keen: What influence do you think the Negro vote will have in the presidential election this year? Dr. King: I think we’ll have great influence. The Negro vote is still the balance of power in your main urban areas, your large communities and large electoral states of our country, and I think the Negro vote may well determine the next president of the United States. Professor Keen: Is there any possibility that you yourself might enter politics following your own advice that Negros should be more active in this field? Dr. King: Well, I haven’t considered this at this point. I do think it is necessary for Negros to become more political minded and for more persons of integrity and depth of understanding, and I think it’s necessary for them to enter politics, but at this point, I feel that my job is in the civil rights struggle and one that should stay above both political parties and not become inextricably bound to either.

Dr. King’s speech at SDSC began at 2:00 p.m. on a Friday afternoon at the Greek Bowl. 30 The speech was well attended; over 4,000 students, faculty, and community members listened to the address. Multiple local newspapers previewed the speech, claiming that this was San Diego’s opportunity to hear from the man who “will not be satisfied until segregation is dead in America” and who was touring California to “mobilize the liberal forces to push passage of the pending civil rights legislation without crippling amendments.” 31 San Diego State Associated Students President Jerry Harmon served as the event’s master of ceremonies. Although King’s address from the event has since been lost, interviews with attendees and newspaper accounts of the event offer snippets of what was said. The most complete account of the address came from the June 2, 1964, Daily Aztec . Buried on page 9 of the campus newspaper with no accompanying picture, an article by student reporter Cathy Pearson talked about how King outlined a “three-point program” to make the American dream a reality for all citizens. 32 According to Pearson, King’s first point concerned universal peace; he told the San Diego State crowd that, “If the American dream is to become a reality, it must be concerned with the world dream… Now man’s moral and ethical commitment must make the world one in terms of brotherhood and peace.” King underscored that, “We must learn to live together as brothers or we will perish together as fools.” 33 His next point dispelled the notion of superior and inferior races, debunking a wide variety of self-serving segregationist arguments. King explained that, “We can’t use the tragic results of segregation as an argument for its continuation.” His final point was a plea for the U.S. to actively eliminate the final remnants of segregation; King was especially vehement in his dismissal of certain well- propagated myths—e.g., “Only time can solve the problem” and “Legislation cannot solve the problem of civil rights”—that placated and ensured maintenance of a bigoted status-quo. He matter-of-factly observed that:

You can’t legislate integration, but you can legislate de-segregation. Morality can’t be legislated, but laws can regulate behavior. Laws can’t make you love me, but they can keep you from lynching me. The law can change our habits, and then our hearts will change.

In addition to detailing this tri-partite plan of action, Dr. King also spoke directly to two pressing legislative matters: 1) the need to pass the federal civil rights act that then sat before Congress (The Civil Rights Act of 1964), and 2) the need to defeat the initiative that would nullify California civil rights statutes (Proposition 14). He urged those in attendance to vote against Proposition 14, concluding that it “would be a setback for American freedom and the entire structure of justice if the Rumford Act in California were repealed.”

King’s speech at the near-capacity Greek Bowl left a lasting impression on many who attended. Multiple alumni who were there recalled the audience being composed and silent when King started. That quiet attentiveness soon shifted to inspired excitement as the civil rights leader delivered his powerful message. Mary Cook, who attended the speech with her communications class, recalled being “blown away” by King. She insisted, “We had been studying and listening to many great speeches, but what I remember best about his speech was his passion.” 34 The content of King’s address also stunned Cook; she remarked that growing up in East County, the plight of many African- Americans living in San Diego was unbeknownst to her. It was only after listening to King that she realized how few African-Americans were in attendance at SDSC. Likewise, class of 1964 alumnus James Sibbet’s lasting memory of the event was of how dynamically King spoke, noting that “I was truly impressed.” 35 Viola Cox, now 97, attended the speech and recalled that, “It was very exciting… I remember the young people jumping up and down saying, ‘What a speaker!’ ‘What a speaker!’” 36

Ralph Clem (San Diego State College Class of 1965), now a retired U.S. Air Force general and professor emeritus of International Relations at Florida International University, also witnessed the event. He reminisced that, “It was clear that [King] was a great orator,” but emphasized that this address was “more of a lecture than it was a speech…I don’t remember it as rousing. I remember it as very impressive.” 37 Clem explained that, “He talked a lot about the institutional basis of the civil rights movement, about the need for legal reforms, the needs for members of minority groups…to have access to the full range of rights that any citizen should expect in this country and how that might be pursued.” It was as if Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., holder of a Ph.D. in systematic theology and policy expert, was speaking to the crowd instead of the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., the devout and inspirational leader of the Civil Rights movement. People who attended both San Diego speeches in 1964 noted by comparison that King’s Cal Western address later that day was less intellectual and more emotional.

Ethnic diversity at SDSC at the time of King’s visit was minimal. According to the San Diego State College yearbook, Del Sudoeste , from 1964, fewer than a dozen graduating seniors were African-American, despite the fact that black students had been attending the institution for over half a century. 38 Willie Horton saw firsthand the hostile environment many African-Americans faced across the country as they sought a higher-education degree. Reminiscing on his experience as an SDSC student, Horton said that certain faculty would purposefully give African-American students failing marks in courses to force them out of the college regardless of the quality of the work. Horton, who attended both of King’s 1964 speeches in San Diego, was especially motivated by the addresses. He recalled that King had an unrivaled ability to “move people to action,” calling him “an effective motivator for students and others in the crowd.” Although King’s San Diego State speech may not have immediately pushed administrators and faculty to create an equal-opportunity campus, Horton believed that his appearance at SDSC enlightened many students to the plight of African-Americans locally and across the nation. Likewise, Clem noted that the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) had been granted student-group status on campus only two days before King’s visit in 1964, and that student awareness of the civil rights movement was “really starting to pick up speed at that time.” 39

Immediately following the conclusion of his speech at the Greek Bowl, King signed a small number of autographs and was quickly led away to a waiting vehicle. 40 His activities after the delivery of his speech at SDSC and prior to his appearance at Cal Western are not well documented. Reports suggest that King and his entourage, which included close associate and fellow SCLC leader Dr. Ralph Abernathy, were taken on a tour of San Diego. This included a short sail on Mission Bay and a scenic drive through San Diego with stops at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery and Mount Soledad. 41

King’s speaking engagement at Cal Western began at 8:00 p.m. in the Golden Gymnasium. Between 3,500 to 5,000 students, faculty, religious groups, and city dignitaries attended the event, which opened with an official welcome to the university by members of the six sponsoring groups responsible for his visit. King’s speech was entitled “ Remaining Awake through a Great Revolution.” Like the address earlier in the day at San Diego State, the content centered on the elimination of all forms of segregation and targeted particular importance to California voters rejecting Proposition 14. He spoke slowly and with purpose, to what he called “a beautiful, integrated audience,” 42 and was interrupted over twenty times by enthusiastic applause. In his speech, King described the attack on his St. Augustine cottage only hours before his arrival in San Diego, emphasizing, “We work under these conditions all along and yet we do it without fear.” King thrilled his audience, covering four central points—1) reaffirming the essential immorality of racial segregation, 2) rejecting the notion of superior and inferior races, 3) insisting that the struggle for equality be non-violent, and 4) explaining that this was a national problem. He used the story of Rip Van Winkle sleeping through the American Revolution as a parable for how to keep all Americans awake during the current social revolution. In closing, Dr. King urged those in attendance to “[s]tand up for justice, not next week, not even tomorrow, not even a[n] hour from now, but at this moment.”

Similar to the recollections of those who witnessed King’s speech at San Diego State, those in attendance at Cal Western were moved by King’s passion and the urgency with which he spoke. Darrel Oliver was nine years old when he heard King speak at the Golden Gymnasium. He recalled that, “The place was electric. There was a feeling of solidarity between us.” 43 Additional interviews echo Oliver’s sentiments; many remarked that they recalled the sensation of being a part of something momentous.

Whether King left immediately following his speech at Cal Western for the airport is not certain. Reports indicated that King and his colleagues only intended to stay in San Diego for ten hours. 44 It is believed that King either received a ride back to Lindbergh Field following his speech or that he stayed in San Diego overnight and left from the airport the following day. The Olivers recalled that there were discussions about King altering his travel plans in an effort to thwart planned attacks, especially considering the events that had just transpired in Florida. 45

Material Legacies

Despite King’s iconic stature, the profundity of his message, and the importance of the times in which he spoke in San Diego, the region’s historical archives contained remarkably little evidence of his 1964 appearance. San Diego State‘s records were especially sparse, leading multiple local administrators, politicians, and dignitaries to suggest that King never even visited the campus. This dearth of material was especially surprising and troubling when compared to the extensive collection the SDSU library from U.S. President John F. Kennedy’s 1963 visit to campus, including audio, video, dozens of photos, programs, seating charts, transcribed oral histories, extensive contemporaneous media coverage, commemorative markers, and statuary. It is suggested here that the lack of memorabilia collection, preservation, and celebration was a continuation of San Diego’s spotty record on civil rights. How else could so little remain from an event in which the famed “Man of the Year” spoke to a capacity crowd on the eve of the most important legislation of the 20th century?

SDSU Special Collections has only three items relating to King’s 1964 appearance: a public announcement request, and two separate invitations to speak in 1965 and 1966. The P. A. spot request revealed that the announcement, “This Friday Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. will address the students and Faculty of San Diego State College. The place – Greek Bowl. The time – 2:00 p.m.,” was read multiple times from May 27-29. The university’s archive also contained evidence showing that although King never returned to San Diego after 1964, SDSC continued to send invitations for him to speak during the 1965 academic year and the 1966 summer session. In his 1965 reply, King alluded to the state of the struggle for civil rights across the country and declined the invitation, citing his newly adopted policy of not accepting speaking engagements more than three months in advance to avoid the potential embarrassment of having to cancel. In 1966, King wrote of his increasingly demanding schedule working with voter-rights’ groups in Chicago, conducting workshops on non-violence, and his increased focus on grassroots movements across the nation as his reason for declining a return visit to San Diego State.

In 2007, Point Loma Nazarene University (formerly Cal Western) honored King’s memory by dedicating a podium-shaped kiosk, replicating the one used during his speech. The interactive memorial, funded by the PLNU Alumni Association, allowed visitors to listen to portions of his speech, read a timeline of Dr. King’s accomplishments, and view multiple photographs. For the 50th anniversary of Dr. King’s speech in 2014, the podium was rededicated.

In an effort to address and start correcting the institution’s longstanding oversight of King’s visit to campus, San Diego State University officials celebrated the golden anniversary of this historic event with a large ceremony that included hundreds of students, faculty, administrators, alumni, and community members. The public gala featured the dedication of a permanent plaque (the largest of its kind on campus), sponsored by California Coast Credit Union, SDSU Associated Students, and the SDSU Alumni Association, and placed prominently at the east entrance of what was once the Greek Bowl—today’s California Coast Credit Union Amphitheatre. The marker included a brief history of King’s visit and highlighted the excerpt from his speech: “We must learn to live together as brothers or we will perish together as fools.” The ceremony included speeches by SDSU President Elliot Hirshman, SDSU Anthropology chair Seth Mallios, aforementioned SDSC alumnus Willie J. Horton, Jr., student-essay contest winners Jessica Ahern, Mary Stout-Clipper, and Thomas De La Garza, and a rousing from-memory rendition of Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech by local nine-year-old Jeremiah Carr.

Conclusions

The legacies of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s 1964 visit to San Diego are remarkably varied. Months after he left the city, Proposition 14 passed by a near two-thirds majority, seemingly marking the end of the state’s Fair Housing Act. 46 In 1966, however, the California Supreme Court would strike down the proposition as unconstitutional. A year later, the U.S. Supreme Court would uphold this decision in Reitman v. Mulkey on the grounds that a state court could invalidate a state’s constitutional amendment if the amendment violated the U.S. Constitution, in this case, the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Simply put, King was decidedly unsuccessful in his attempts at convincing West Coast voters to defeat Proposition 14, but state and federal courts would rescue the Rumford Act. Furthermore, King’s setback in the Golden State was offset by landmark national gains, first and foremost being the Civil Rights Act in 1964, passed about a month after his San Diego appearance. 47 In addition, those groups that were actively protesting racial discrimination in the region before King’s local collegiate tour in 1964, including CORE and may others, continued to gain momentum in demonstrations against bigoted employment practices in San Diego. Moreover, SDSU’s institutional amnesia of King’s historic visit has finally been at least partially addressed by the anniversary celebration and a prominent and permanent public plaque that will prevent anyone on campus from ever wondering again, “Did MLK really visit State?”

Lastly, the authors of this article insist on preserving King’s Cal Western speech here in its entirety for multiple reasons. Not only did the address come at one of the most important times in the nation’s history and contain a powerful message of peace and equality in the face of violence and hate, but it also was nearly lost from the permanent historical record. In fact, the San Diego State speech is apparently gone, and the Cal Western address has been accidentally misplaced multiple times. 48 With its reproduction here, King’s words in his final address in San Diego will never be lost again.

“Remaining Awake through a Great Revolution,” Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s California Western University Speech. 49