What is Nature Writing?

Definition and Examples

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Nature writing is a form of creative nonfiction in which the natural environment (or a narrator 's encounter with the natural environment) serves as the dominant subject.

"In critical practice," says Michael P. Branch, "the term 'nature writing' has usually been reserved for a brand of nature representation that is deemed literary, written in the speculative personal voice , and presented in the form of the nonfiction essay . Such nature writing is frequently pastoral or romantic in its philosophical assumptions, tends to be modern or even ecological in its sensibility, and is often in service to an explicit or implicit preservationist agenda" ("Before Nature Writing," in Beyond Nature Writing: Expanding the Boundaries of Ecocriticism , ed. by K. Armbruster and K.R. Wallace, 2001).

Examples of Nature Writing:

- At the Turn of the Year, by William Sharp

- The Battle of the Ants, by Henry David Thoreau

- Hours of Spring, by Richard Jefferies

- The House-Martin, by Gilbert White

- In Mammoth Cave, by John Burroughs

- An Island Garden, by Celia Thaxter

- January in the Sussex Woods, by Richard Jefferies

- The Land of Little Rain, by Mary Austin

- Migration, by Barry Lopez

- The Passenger Pigeon, by John James Audubon

- Rural Hours, by Susan Fenimore Cooper

- Where I Lived, and What I Lived For, by Henry David Thoreau

Observations:

- "Gilbert White established the pastoral dimension of nature writing in the late 18th century and remains the patron saint of English nature writing. Henry David Thoreau was an equally crucial figure in mid-19th century America . . .. "The second half of the 19th century saw the origins of what we today call the environmental movement. Two of its most influential American voices were John Muir and John Burroughs , literary sons of Thoreau, though hardly twins. . . . "In the early 20th century the activist voice and prophetic anger of nature writers who saw, in Muir's words, that 'the money changers were in the temple' continued to grow. Building upon the principles of scientific ecology that were being developed in the 1930s and 1940s, Rachel Carson and Aldo Leopold sought to create a literature in which appreciation of nature's wholeness would lead to ethical principles and social programs. "Today, nature writing in America flourishes as never before. Nonfiction may well be the most vital form of current American literature, and a notable proportion of the best writers of nonfiction practice nature writing." (J. Elder and R. Finch, Introduction, The Norton Book of Nature Writing . Norton, 2002)

"Human Writing . . . in Nature"

- "By cordoning nature off as something separate from ourselves and by writing about it that way, we kill both the genre and a part of ourselves. The best writing in this genre is not really 'nature writing' anyway but human writing that just happens to take place in nature. And the reason we are still talking about [Thoreau's] Walden 150 years later is as much for the personal story as the pastoral one: a single human being, wrestling mightily with himself, trying to figure out how best to live during his brief time on earth, and, not least of all, a human being who has the nerve, talent, and raw ambition to put that wrestling match on display on the printed page. The human spilling over into the wild, the wild informing the human; the two always intermingling. There's something to celebrate." (David Gessner, "Sick of Nature." The Boston Globe , Aug. 1, 2004)

Confessions of a Nature Writer

- "I do not believe that the solution to the world's ills is a return to some previous age of mankind. But I do doubt that any solution is possible unless we think of ourselves in the context of living nature "Perhaps that suggests an answer to the question what a 'nature writer' is. He is not a sentimentalist who says that 'nature never did betray the heart that loved her.' Neither is he simply a scientist classifying animals or reporting on the behavior of birds just because certain facts can be ascertained. He is a writer whose subject is the natural context of human life, a man who tries to communicate his observations and his thoughts in the presence of nature as part of his attempt to make himself more aware of that context. 'Nature writing' is nothing really new. It has always existed in literature. But it has tended in the course of the last century to become specialized partly because so much writing that is not specifically 'nature writing' does not present the natural context at all; because so many novels and so many treatises describe man as an economic unit, a political unit, or as a member of some social class but not as a living creature surrounded by other living things." (Joseph Wood Krutch, "Some Unsentimental Confessions of a Nature Writer." New York Herald Tribune Book Review , 1952)

- Creative Nonfiction

- Defining Nonfiction Writing

- A Guide to All Types of Narration, With Examples

- What You Should Know About Travel Writing

- Notable Authors of the 19th Century

- Genres in Literature

- Top 5 Books about Social Protest

- Must Reads If You Like 'Walden'

- Great Summer Creative Writing Programs for High School Students

- Point of View in Grammar and Composition

- Ways of Defining Art

- Ralph Waldo Emerson: American Transcendentalist Writer and Speaker

- What Is a Synopsis and How Do You Write One?

- The Power and Pleasure of Metaphor

- What Literature Can Teach Us

What is nature writing?

What we talk about when we talk about nature writing.

“Nature writing can be defined as non-fiction or fiction prose or poetry about the natural environment.” This is actually its definition on Wikipedia.

For the purposes of this prize, we're accepting only non-fiction prose submissions (see last week's resources on breaking down the brief ), but in general, nature writing can mean many more things and cover lots of different ideas. As such, there’s a whole variety of approaches to writing a book in this genre. Different types of nature writing books can include: factual books such as field guides, natural history told through essays, poetry about the natural world, literary memoir and personal reflections.

Typically, nature writing is writing about the natural environment. Your book might take a look at the natural world and examine what it means to you or what you’ve encountered in the environment. You could frame this idea through a personal lens.

Perhaps you want to take a more focused or factual approach and look at individual flora and fauna in detail. Recent books that we’ve enjoyed have looked at topics such as beekeeping, owls, social and cultural history, trees, swimming, cows and have offered personal observation and reflection on their chosen topics.

You might be writing about the landscape, from farming to remote islands or city life. You may want to write about the fauna and flora of a whole region, or just one animal or a single tree. You don’t need to go out into the wilderness to write about nature and you don’t need to be hiking for three months in a remote area either. Most importantly, we believe the best books on nature writing convey a clear sense of place and mainly focus on the natural world and our human relationship with it.

The Nan Shepherd Prize aims to find the next big voice in nature writing from emerging writers, and we can’t wait to read about what nature means to you.

- Read an academic paper on New Nature Writing here .

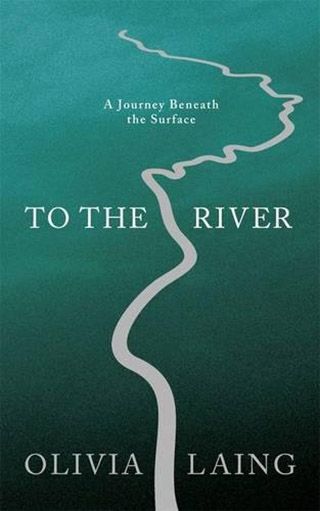

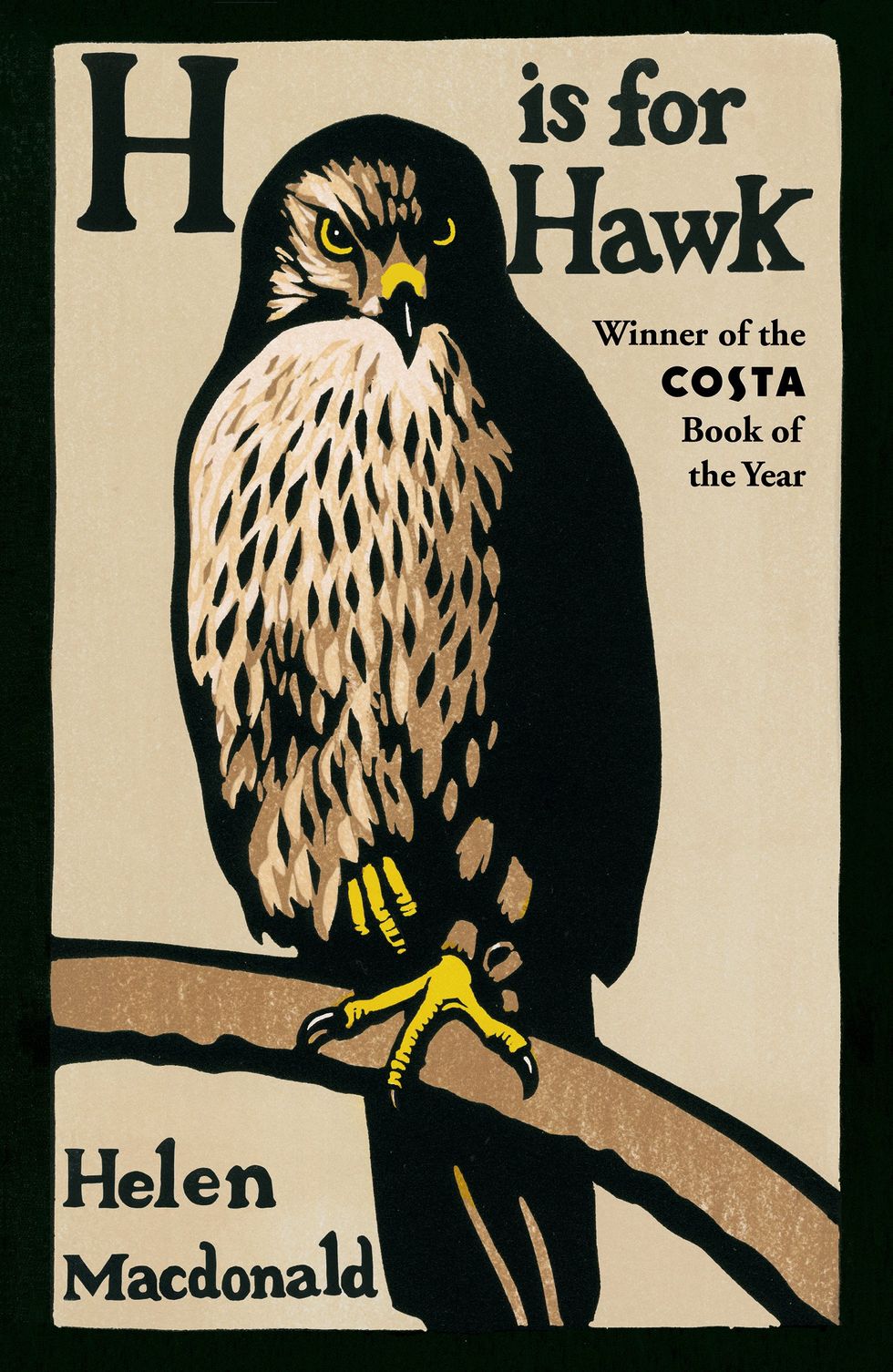

- ‘Land Lines’ was a two-year project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, and is a collaboration between researchers at the Universities of Leeds, Sussex and St Andrews. The project carried out a sustained study on modern British nature writing, beginning in 1789 with Gilbert White’s seminal study, The Natural History of Selborne, and ending in 2014 with Helen Macdonald’s prize-winning memoir, H is for Hawk. You can look at their website here .

- Read about nature writing throughout history (this is a US perspective) here .

- Read about which nature books have inspired today’s contemporary nature writers here .

- Read this guide to nature writing from Sharmaine Lovegrove, publisher of Dialogue Books, who teamed up with the Forestry Commission to find undiscovered nature writers here .

Over @NanPrize we’ve been sharing examples of our favourite nature writing books, so if you want to see some specific examples of recent favourites, that might be a good place to start. We’ve also got a collection here which will give you an idea as to what books we like to publish in the nature writing genre.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Book News & Features

The workings of nature: naturalist writing and making sense of the world.

Genevieve Valentine

Buy Featured Book

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

"In every generation and among every nation, there are a few individuals with the desire to study the workings of nature; if they did not exist, those nations would perish."

-- Al-Jahiz, The Book of Animals

In 185 AD, Chinese astronomers recorded a supernova. Among more detached details of its appearance, there is this: "It was like a large bamboo mat. It displayed the five colors, both pleasing and otherwise."

The attempt to ground the unknown within the familiar — and the editorial aside of "otherwise" — cuts to the heart of naturalist writing. Nearly 2000 years later, Carl Sagan did the same in Cosmos , condensing astronomy to its component parts: facts and wonder.

We've been curious about the natural world since before recorded time; the history of naturalism is human history. By the ninth century, al-Jahiz's multi-volume History of Animals combined zoological folklore with scientific observation, including theories of natural selection. In the early 20th century, Sioux author Zitkala-Ša wrote landscapes intertwined with the personal, which became a model for the form. In 1962, Rachel Carson's ecological manifesto Silent Spring was a deciding factor in banning DDT.

The best naturalist writing delivers both a secondhand thrill of obsession and a jolt of protectiveness for what's been discovered. Some of it reveals as much about the author as the surroundings. (Carl Linnaeus' 1811 Tour of Lapland manuscript cuts off a paragraph about wedding customs mid-sentence, picking up again with a breathless catalog of marsh plants.) And naturalists themselves are shaped by the lure of landscapes on the page. Robert MacFarlane's Landmarks explores the British countryside using others' writing as an interior map that challenges him to approach familiar places in new ways.

We love reading about nature for the same reason naturalists love being ankle-deep in marshes: Nature provides enough order to soothe and enough entropy to surprise. It's also why so many involve a person in the landscape; understanding our place in the world is as important as understanding the world itself. We read the work of naturalists to capture that sense of discovery made familiar. They present worlds we've never seen, and make us care as if they were our own backyards.

Not every naturalist sets out to be an activist; this is a literary tradition as much as a scientific one. But there are threads that connect naturalist literature, across continents and centuries. It's driven by an environmental curiosity that integrates the scientific and the spiritual; facts inspire wonder, rather than quench it. And every piece of naturalist literature, from al-Jahiz to today, makes a case for preserving the world it sees.

The Invention of Nature

Some naturalists actually do try to encompass the world entire. In The Invention of Nature , Andrea Wulf follows Alexander Humboldt's expeditions in Latin America and European royal courts, painting a portrait of a man whose hunger for knowledge — and constant pontificating about it — bordered on caricature. Humboldt's legacy is the 'web of life' his work conveyed to a lay audience. That interconnectedness made him an early conservationist; by 1800 he was noting adverse effects "when forests are destroyed, as they are everywhere in America by European planters, with an imprudent precipitation."

But he wasn't the first to catalog the systems of life. A century before Humboldt, German-born naturalist Maria Sybilla Merian was in Surinam, recording her life's passion: butterflies, moths, and insects. Chrysalis , Kim Todd's biography of this amateur scientist who established the idea of a life cycle, aims for a sly impression of Merian, down to the subject matter: "Insects," Todd explains, "generally gave off a whiff of vice." Merian's engravings made life cycles palpable for a public who still believed rotten meat spontaneously transformed into flies; it was impressive enough to change assumptions about the natural world (though Merian's credit waned as male scientists began absorbing her work into their own).

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

To write about the world around us is to write about people, whether cataloging the unknown or coming to terms with one's backyard. This is the dynamic at the heart of Annie Dillard's Pilgrim at Tinker Creek , which carries a touch of the hymnal (and a grim streak that has a grandmother in Merian's engraving of a tarantula devouring a bird), and Barbara Hurd's Stirring the Mud , a love letter swamps, bogs, and "the damp edges of what is most commonly praised." And few naturalists write themselves into their landscapes quite so drily as M. Krishnan. The essays in Of Birds and Birdsong carry a sense of magical realism; always scientifically rigorous (his bird descriptions are those of a man looking for a particular friend in a crowd of thousands), Krishnan writes himself as a resigned meddler in avian affairs; he could try to be invisible among nature's bounty, but then who'd train his pigeons?

Of course, some writers have to fight to be seen on the landscape at all. Enter The Colors of Nature , an anthology of nature writing by people of color edited by Alison H. Deming and Lauret E. Savoy, providing deeply personal connections to — or disconnects from — nature. Jamaica Kincaid's "In History" considers naturalism in the aftermath of colonialism, asking a crucial question for naturalism in a global context: "What should history mean to someone who looks like me?" And Joseph Bruchac's travel diary is pragmatism shot through with hope; "Our old words keep returning to the land."

The Colors of Nature

For others, the internal landscape and that hope for the natural world must be rediscovered in tandem. In Braiding Sweetgrass , botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer tackles everything from sustainable agriculture to pond scum as a reflection of her Potawatomi heritage, which carries a stewardship "which could not be taken by history: the knowing that we belonged to the land." That sense of connection, or the loss of it, is the spine of the book: mucking out a pond is a microcosm, agriculture becomes rumination on symbiosis, and mast fruiting of pecan trees parallels human and plant communities.

It's a book absorbed with the unfolding of the world to observant eyes — that sense of discovery that draws us in. Happily for armchair naturalists, mysteries of the natural world never stop unfolding; but increasingly, a sense of impending doom accompanies the delight of knowledge. Kimmerer mentions a language between trees as something awaiting more specific study; it arrives later this year in Peter Wohlleben's The Hidden Life of Trees . A no-nonsense writing style — he came, he studied, here's how to date a forest via its weevil population — frames a deeply conservationist argument: Trees harbor not only ecosystems, but feelings, vocabulary, and etiquette. Hidden Life is designed to be an arboreal Silent Spring .

For some places, however, no revelations are yet possible; the world being studied is simply too mysterious to be yet wholly understood. With meditative prose, 1986's Arctic Dreams chronicled Barry Lopez's expeditions in an ecosystem so punishing half an animal population can die every winter, and so otherworldly animal fat is preserved on bones after a century. "Something eerie ties us to the world of animals," he says, and it's both a warning and a promise. In The Whale: In Search of the Giants of the Deep, Philip Hoare's marine obsession is similarly dreamlike; for him, what we know about whales and how they make us feel is deeply linked. After all, our 'discovery' of them is still in its first blush. Sperm whales were first filmed in 1984; "We knew what the world looked like before we knew what the whale looked like." The only absolute conclusion in his book is a stern one: Humanity's damaging effects on nature and its fascination with the unknown has been devastating; if we're going to keep whales long enough to know them, that fascination will have to take a more protective turn.

To write about the world around us is to write about people, whether cataloging the unknown or coming to terms with one's backyard. These narratives are crucial, especially now — stories of the worth of nature, even just as a mirror of ourselves, build a narrative in which nature's something worth saving. It's imperfect; making nature an object rather than a subject prevents us from seeing ourselves as part of natural patterns of cause and effect. But in The Colors of Nature, Aileen Suzara pins it down: "The landscape is a narrative, not a narrator, because it has no human voice." The human voice that looked at the dark and saw a dying star is heard 2000 years later. If we're going to have another 2000 years, there's no time like the present to start listening.

Genevieve Valentine's latest novel is Icon.

Advertisement

Supported by

THE NATURE OF NATURE WRITING

- Share full article

By David Rains Wallace

- July 22, 1984

NATURE writing is a historically recent literary genre, and, in a quiet way, one of the most revolutionary. It's like a woodland stream that sometimes runs out of sight, buried in sand, but overflows into waterfalls farther downstream. It can be easy to ignore, but it keeps eroding the bedrock.

There is some confusion as to exactly what nature writing is. It usually is associated with essays such as ''Walden,'' but there is nature fiction, nature poetry, nature reporting, even nature drama, if television documentary narrations are literature. All these have something in common: They are appreciative esthetic responses to a scientific view of nature, and I think this trait defines the genre. Of course, there was much writing that concerned nature before Linnaeus developed scientific classification in the mid- 18th century, but the fascination with nature itself that science evoked was new. Before Linnaeus, there were hunting stories, fables, herbals, bestiaries, pastorals, lyrics and traveler's tales, but nature generally was seen in only two dimensions. It was a backdrop to a historical cosmos, or a veneer over a religious one. Whether it was admired or scorned, the human figure stood in strong relief against it. After Linnaeus began to give even insects impressive Greco-Latinate names, nature rapidly acquired a new substantiality, and became a subject as well as a setting. By the 1790's, an English country clergyman who a century or two before might have been writing theological treatises or metaphysical poems produced a book (Gilbert White's ''The Natural History of Selborne'') wherein history and religion were interwoven with, sometimes overshadowed by, beech trees and earthworms.

Nature writing has been particularly prevalent in America, for an obvious reason. European colonists found here a world which was for them (if not for the Indians they displaced) empty of historical or religious association. In this world, they ignored nature itself at their own risk. The early Jamestown and Boston colonists succeeded in ignoring it to some degree, which perhaps is one reason they clung precariously to the coast for the first hundred years, but by Linnaeus's time, Americans had begun to observe nature closely, and to venture into the wilderness with appreciation.

They observed in a piecemeal fashion at first, and ventured without too much appreciation. Early naturalists, such as Cadwallader Colden and John Bartram, were more interested in extracting rare, valuable plants and animals from the wilderness than in perceiving it as a whole, an attitude in keeping with the Linnaean bias for individual organisms over ecological systems (ecology not having been invented yet). Bartram, a Philadelphia Quaker who collected Venus' flytraps and other curiosities for wealthy English patrons' gardens, saw the wolves and swamps of the wilderness as uncomfortable obstacles, and his descriptions of Florida and upstate New York in the 1750's and 60's reflect this. They are robust and accurate, but utilitarian. They are not quite nature writing as we understand it today, because an element of poetic sensibility is lacking from their genuine scientific interest.

JOHN'S son, William Bartram, supplied the missing element. An artist and dreamer who failed several times at storekeeping and farming, he spent four years alone in the American wilderness, and brought poetry to it as decisively as a rather similar figure, Johnny Appleseed, brought fruit. His account of Florida and the southern Appalachians in his book, the ''Travels,'' is a subtropical escarpment dividing dry Enlightenment from moist Romanticism. William's father had described the waters of one of Florida's celebrated limestone sinkhole springs as smelling ''like bilge,'' tasting ''sweetish and loathsome,'' and boiling up from the bottom ''like a pot.'' William saw ''an enchanting and amazing crystal fountain, which incessantly threw up, from dark, rocky caverns below, tons of water every minute . . . the blue ether of another world.''

If William's effusions have a familiar ring to even the most urban sensibility, there is good reason. After its publication in 1791, Bartram's ''Travels'' was devoured by the generation of young European poets that included the author of ''Kubla Khan.'' Bartram supplied Coleridge, Wordsworth, Chateaubriand, and others with genuine examples of the exotic, Rousseau- esque wonders they hungered for - not only ''caverns measureless to man,'' but noble Creek warriors, lovely Cherokee maidens, flowery savannas, fragrant groves, brilliant birds. The wonders seem a little overblown to us today, but they were real, honestly observed and vividly described. Fragments of their splendor still linger in today's condominium-laden Florida. The ''magnificent plains of Alachuah,'' where Bartram saw ''the thundering alligator'' and ''the sonorous savanna cranes,'' are now a state preserve, although there's an Interstate freeway through one corner of them.

The ''Travels'' didn't evoke as much interest in America as it did in Europe. Most Americans were unprepared for its glowing picture of wilds that lay only a few days' travel to the west. One reviewer found its subject interesting but its style ''disgustingly pompous.'' As the romantic sensibility filtered westward across the Atlantic, however, Bartram's poetic wilderness followed it. ''Do you know Bartram's 'Travels'?'' Carlyle wrote to Emerson, ''Treats of Florida generally, has a wonderful kind of floundering eloquence in it; and has grown immeasurably old. All American libraries ought to provide themselves with that kind of book; and keep them as a future biblical article.''

If the more flowery passages in Fenimore Cooper's Leatherstocking Tales are to be believed, American pioneers were beginning to sound more like William than his father. In fact, early 19th-century frontier letters contain quite a few effusive descriptions of flowery prairies and soaring forests along with more prosaic matters, suggesting that nature-loving in the romantic mode had caught on.

Nature writing changed as romanticism evolved into Victorian pragmatic optimism. Its scientific orientation deepened, and at the same time it began to question the directions in which economic applications of science were leading civilization. It became increasingly aware of ecology, in other words. William Bartram hadn't given too much thought to the relationship of civilization and wilderness. (His patron had sent him to scout the Southeast's agricultural and industrial potential as well as to study its natural history.) But Henry Thoreau did, and John Muir after him. Pragmatic, optimistic men (both were mechanically skilled inventors as well as naturalists), they saw wilderness as a remedy for the enervations and constraints of growing industrial towns. They hauled it down from the garret of romanticism to the Victorian parlor and kitchen. ''We require an infusion of hemlock, spruce, or arbor vitae in our tea,'' wrote Thoreau, with characteristic pungency (and hyperbole). ''Hope and the future for me are not in lawns and cultivated fields, not in towns and cities, but in the impervious and quaking swamp.''

Although they often are seen as opposed to 19th-century expansionism, Thoreau and Muir were men of their time, inhabiting a planet with about a quarter of today's population. Land speculators saw hope and future in quaking swamps too, although they differed from Thoreau in wanting to see them drained after they'd bought them cheap. One might say that Thoreau and Muir liked the expansive quality of the frontier so much that they wanted to make it permanent, to integrate its challenges and exhilarations with civilization. From this desire, expressed in Thoreau's New England swamp ruminations and Muir's California mountaintop raptures, arose the concept of the wilderness park, America's unique contribution to global culture.

As Victorian optimism ripened into Edwardian euphoria, the words of Thoreau and Muir struck increasingly responsive chords with the public. Expansion of the frontier was making America rich, but it was gobbling up natural resources so fast that the idea of preserving some wilderness for recreation, or at least for future use, had become respectable. Nature writing had a heyday at the turn of the century, especially during the Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, himself a nature writer of sorts. It would be hard to imagine John Muir going camping in Yosemite with the present Republican incumbent, but he did with Teddy Roosevelt. John Burroughs, a less acerbic writer than Thoreau or Muir, enjoyed tremendous popularity with books about countryside wildlife, and went camping with Henry Ford and Thomas Edison as well as Roosevelt.

The heyday didn't survive Muir and Roosevelt. The scientifically conducted carnage of the First World War revealed the rot at the Edwardian core, and pragmatic optimism became a mark of naive boosterism. Many American writers were overtaken by a wave of nostalgia for the prescientific, for the nobility in which religion and history can clothe humanity. Muir and Thoreau had complained eloquently of human conceit and destructiveness, but they still had taken for granted a high degree of human significance. It was harder to do this after a generation of young men had been slaughtered in the trenches. The pragmatic remedies of progressives seemed inadequate to modernists, who sought utopias.

The modernist flight of American writers to Europe was a frontier in reverse. Nature writing meant little to its pioneers, Pound and Eliot, who turned their backs on Idaho and Missouri to embrace medieval Europe. Even the outdoorsman Ernest Hemingway had a medieval attitude toward wilderness. It was a place for hunting, fishing or war, not for seeking knowledge, transcendent or otherwise. Knowledge was for priests. D. H. Lawrence excluded Thoreau from his canon of American classics, regarding him as a coldhearted detailer of biotic mechanisms.

But nostalgia for the prescientific degenerated into fascism, helping bring about the Second World War and even more murderous applications of science. As though seeking an antidote in the serpent that had stung it, the postwar world turned back to pragmatic optimism of a sort, with much talk of new frontiers in the Arctic, the tropics, the oceans, space. Nature writing underwent a resurgence, partly as a result of renewed public interest in science, partly as a result of renewed public uneasiness about its applications. The popularity of Rachel Carson's best-seller,''The Sea Around Us,'' which eloquently introduced the public to many new discoveries about the biosphere, gave her the time and authority to write ''Silent Spring,'' which eloquently introduced the public to the many new dangers of pesticides and herbicides.

Carson and other outstanding postwar nature writers, such as Aldo Leopold and Loren Eisely, were somewhat different from their predecessors, reflecting American society's growing dependence on expert knowledge. Bartram, Thoreau, and Muir were amateurs, but Carson, Leopold, and Eiseley were institutionally trained and employed scientists. There were advantages and disadvantages to this. Carson and her colleagues could appeal to vastly expanded knowledge of the biosphere's interdependence when advocating wilderness preservation, while Muir and Thoreau worked more from intuition. On the other hand, professional positions may have inhibited postwar writers from the robust partisanship that let John Muir lobby unabashedly for birds and flowers in 19th-century Sacramento.

There's no doubt that Carson, Eisley, and Leopold contributed greatly to the wave of environmental partisanship in the 1960's and 70's. That surge has encouraged a new crop of nature writers; despite continuing shrinkage of wilderness, there probably are more nature writers today than ever. It remains to be seen whether we'll be as influential as our predecessors. At times, the prospects look dim. Since land development became a major industry, there has been an expectation in some quarters that wilderness simply will disappear eventually, replaced by artifice. Some writers seem to have accepted this. They write like undertakers: an elegy on every page. A new book about this or that last wilderness comes out at least once a year.

It's important for us to know how bad things are, but to me there's something unimaginative about the elegists. As dealers in myth, writers ought to know better than to let technocrats and salesmen mesmerize them into believing that civilization can conquer nature. They should understand that this is a myth too, what one might call the myth of nature as loser. But nature is not a loser because it is not a competitor: It simply is. We have better myths. Evolution, the vast, intricate story of four-billion-year-old wilderness earth, throws a cold light on man the conqueror. The nature- as-loser myth was useful when humanity was small and wilderness large; it encouraged the growth of civilization, and of knowledge. It's of doubtful utility to us, who are capable of reducing the biosphere to dust. It is not nature that will have lost in that event.

THERE'S a lot of work for nature writers to do. It's not quite the same work that William Bartram faced. Adventure is a luxury commodity today, packaged by tour agencies. The old, romantic, exotic nature writing is of declining relevance. I wonder how many people have gone to the library to read about something in their local woods and found books about the Arctic, the tropics, the oceans and space, but nothing much about their local woods. I certainly have: It's one more reason I started writing nature books.

Carson, Leopold, and Eiseley did much of their exploring in their studies. The most daunting challenge facing nature writers today is not travel but data. Somebody has to translate information into feelings and visions. This is not to say that nature writers now must spend all their time at computer terminals. Collecting mosquito bites always will go with the job, and there are still more places to do so, even in America, than some people think. They're generally the worse for wear, these places, but they're still alive, still holding up the biosphere, still part of what Wallace Stegner calls ''the geography of hope.'' B

David Rains Wallace is a naturalist and the author of ''The Klamath Knot,'' a collection of writings on the Klamath Mountains in California. He is working on a book about Florida.

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

James McBride’s novel sold a million copies, and he isn’t sure how he feels about that, as he considers the critical and commercial success of “The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store.”

How did gender become a scary word? Judith Butler, the theorist who got us talking about the subject , has answers.

You never know what’s going to go wrong in these graphic novels, where Circus tigers, giant spiders, shifting borders and motherhood all threaten to end life as we know it .

When the author Tommy Orange received an impassioned email from a teacher in the Bronx, he dropped everything to visit the students who inspired it.

Do you want to be a better reader? Here’s some helpful advice to show you how to get the most out of your literary endeavor .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

Disabled Poets Prize

Deptford literature festival, nature nurtures, early career bursaries, criptic x spread the word, lewisham, borough of literature, a pocket guide to nature writing.

In this glorious Pocket Guide, Kerri ní Dochartaigh highlights the value of Nature writing, whilst sharing her personal tips, resources and opportunities on how you can get inspired to write.

What do we really mean when we talk about ‘nature writing’? And what do we even mean when we talk about ‘nature’?

Nature writing , like pockets , is a politicised thing – embroidered with different threads; depending on your race , class , gender , (dis)ability, wealth or place in this world. Is there space here for you? Do you feel safe? There has never been a more important time to make safe space: for every single thing on this earth. The writing, then, will just do its own thing, you see. It will come and go as it pleases, like a moth to a big aul’ light.

How about a wee browse through these background reads , and then we might, in the words of Edwyn Collins , (the most inspiring nature punk on earth): ‘Rip it up and start again’?… (What is nature writing if not the constant riotous act of starting again? Of learning, again, to listen and to look, to draw close and keep our distance, to break and to weep; to get back up and love the world afresh?) In this NY Times piece three and a half decades ago, David Rains Wallace wrote ‘NATURE writing is a historically recent literary genre, and, in a quiet way, one of the most revolutionary.’

We’re ready for this revolution but who is going to lead it?

For far too long we have allowed a very particular voice, from a very particular background, with a very particular outlook – dominate bookshop displays, library shelves, reading lists, bestseller rankings and our own homes. This, the idea that there has only ever been one nature story, is wildly incorrect. Other standpoints, other views, other stories, other voices: have always been there. In ‘Heart Berries’ Terese Marie Mailhot summarises: ‘So, where are we? Where we have always been. Where are you?’

To write about nature with truth and integrity means to ask questions about the past and the future – who, where and what have been mistreated – and how do we make that stop, through how we approach this genre? I only want to be a part of any gathering where every single one of us is there as an equal.

So, who is doing the important work in this area? Where should you go to read more? Where should you send your fledgling words?

Let’s start with The Willowherb Review because I think they are incredible. Their aim is ‘to provide a digital platform to celebrate and bolster nature writing by emerging and established writers of colour’, and already their writers have seen prize nominations and awards (all links on the site). Most importantly of all the writing is cracking; beautiful, raw and necessary. Jessica J Lee, the editor, has a no nonsense approach to the genre that I deeply admire. If you are a nature writer of colour, check out their website for submission dates.

Jessica has also organised a reading group, Allies in the Landscape , a fantastic support for nature writers and anyone wanting to widen their reading in the genre.

The folks at Caught by the River do stellar work for those who love the natural world across a plethora of genres. If you are in need of inspiration, or events to go to when we can, start here. You will not be let down. They read everything they’re sent but are a busy crew so – as with submitting anywhere, patience is kindness.

More folks with big hearts and brilliant writing are The Clearing .

The art of nature writing itself can be a children’s story, a poem, a list, a eulogy, a translation – it can be fiction or non – written or other – short or long; it is anything that takes our world and makes it sing. The best nature writing, for me, speaks of transformation – anything from a fiercely hungry caterpillar, through to strong women swimming themselves to safe places – making lists of yellow things for their sick fathers – moulding grief through sowing seeds: the best nature writers might not even call themselves that at all. Some books I have recently loved are: ‘ Trace’ by Lauret Savoy, ‘Braiding Sweet Grass’ by Robin Wall Kimmerer Elizabeth J Burnett’s ‘ The Grassling’ , ‘ Bulbul Calling’ by Pratyusha, Seán Hewitt’s ‘ Tongues of Fire’ , Jessica J Lee’s ‘ Two Trees Make a Forest’ , ‘The Promise’ by Nicola Davies and ‘ The Diary of a Young Naturalist’ by Dara McAnulty. I return over and over to writers like Amy Liptrot, Kathleen Jamie, Annie Dillard, Robert McFarlane and others but I am constantly trying to find new voices, approaches and stories – new to me, not new in their existence, of course: it’s important to make that distinction in a genre such as this.

The important thing, needed now more than ever, is that they each take their place in this symphony of hope.

There is room, here, on these mountains and beaches, in these gardens and fields, in these bodies of water – in ASDA parking lots and unsafe spaces – on the streets, and in every place both ‘wild’ and not (both outer and inner) – for you and your story.

From me to you, here a few exercises I return to over and over as a means to get started…

Choose something – a moth, the colour blue, a tree, a wren, a pebble, the waves on the beach – and write about it as if the reader will have never before seen or heard of it. Really stay with the description for as long as you can, and try to get down to what it really is: its thingness. Make your description almost like a love letter in how much care you take with it, and the depth of your words. Another interesting take on this is to write yourself as the thing – to really imagine, say, going through all the stages of the cycle from caterpillar to moth – or the ebb and flow you would experience as a particular body of water etc.

Journal – at least three free-flow pages without thinking about them or rereading – every single day. This one really helps to get me out of my normal flow of thought, and does something to my brain that welcomes experiences, creatures and thoughts that are conducive to nature writing. It really doesn’t matter if I am not writing about nature in these pages, really that is not the point, I think it’s in the act of carving out space and time – bringing awareness to the act. The space in which I write these can be a cafe, on a train, or at home, and still I find myself in a wild place, one that is on the inside not the outside.

The thing that most helps me to write about the natural world is actually being in it – walking, swimming, running, laying, laughing, crying – just allowing myself to be outside as much as I can seems to be the best way for me to try to write about the world we share.

Once you feel more confident, you might be interested in entering your writing into a prize or sharing it online (an incredible amount of links can also be found in the hyperlinked pages too) and I can share only a fraction but here are a few that sing to me:

https://nanshepherdprize.com This prize is changing the landscape of this genre. Every single section on the site is invaluable.

https://www.thenaturelibrary.com

Christina Riley has put such a wonderful thing together here. Have a browse / follow.

https://www.lonewomeninflashesofwilderness.com/about

Clare Archibald’s inspiring, inclusive site is really making ripples in this area.

https://beachbooks.blog/about/ A gorgeous, generous sea library full of joy.

https://www.elementumjournal.com Submissions are closed for this journal but there is lots of fine work to peruse.

https://www.elsewhere-journal.com This is a superb journal of place, and submission are open.

The Moth Nature Writing prize , The Rialto Nature Poetry Competition and others are great to look at too. There are courses, schemes and more online but I think the most important place to start is by looking and listening, reading and caring; by loving the world and by writing it down in any way you can.

For me, any time any of us looks and listens to the non-human beings we share this earth with – when we pause in humility to acknowledge the interconnectedness of us all – the threads tying us to each other; invisible often, but so strong – we are playing a part in making this a safer, fairer earth. To go one step further, and to write about this connection, to name, explore, celebrate and honour – whether we choose a swan or a stone, a moth or a lough, the wild sea or our gut flora; things nearby or faraway, the known or unknown – we are shining light on one of the most important truths of this earth: our need to be alive, and to remain connected to every other living thing. There is power in trying to find traces of ourselves in the nonhuman, as well as acknowledging our difference. In searching for the beat of something unnameable; the simple act of being alive, at the same time, as each other, and in the same way as even the smallest insect.

Nature Writing holds the hope, for me, of reminding us how to treat everyone and everything on the earth. The best nature writing shines light on places we need to see; on beings we need to learn to accept as our equal. It is only a proper telling of the earth if we can tread gently on the land and the non-human as well as human while we do it. If we can speak honestly of the places and the past – if we can find a way to write it where every single one of us is heard; where each one of us, and our stories, are kept safe.

Kerri ní Dochartaigh is from the North West of Ireland but now lives in the very middle. She writes about nature, literature and place for The Irish Times, The Dublin Review of Books, Caught By The River and others. Her first book, Thin Places , is out with Canongate in January 2021. @kerri_ni @whooperswan

Published 7 July 2020

Read the 2024 Nature Nurtures Anthology & Watch the Nature Nurtures Short Films

Announcing the winners of the lba literary agency feedback opportunity 2024, teach with us: developing tutors programme.

- Opportunities

We’re hiring: Programme and Communications Assistant

Stay in touch, join london writers network, spread the word’s e-newsletter.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with Spread the Word’s news and opportunities.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

29 Nature Writing

Philip F. Gura is the William S. Newman Distinguished Professor of American Literature and Culture at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he holds appointments in the departments of English and religious studies and in the curriculum in American studies. He is the author or editor of nine books, including The Wisdom of Words: Language, Theology, and Literature in the New England Renaissance; A Glimpse of Sion's Glory: Puritan Radicalism in New England, 1620– 1660; the prize-winning America's Instrument: The Banjo in the Nineteenth Century (with coauthor James F. Bollman); Jonathan Edwards: America's Evangelical; and American Transcendentalism: A History, a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. He is an elected member of the Society of American Historians and was recently named distinguished scholar by the MLA's division on American literature to 1800. He serves as an editor of the Norton Anthology of American Literature.

- Published: 18 September 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This article focuses on the idea of nature writing as adapted by the Transcendentalists. Henry David Thoreau is considered as the exponent of nature writing in American Transcendentalism. This article traces what nature writing is, what constitutes Transcendentalist nature writing, and why one author can be more successful at it than another. For more than a century some literary critics have bravely, if not fully convincingly, addressed these issues. One of the first twentieth-century commentators to do so, Philip Marshal Hicks, offered, in 1924, a very strict definition of the genre of nature writing. This article refers to the works of Thoreau and Emerson in relation to the genre of nature writing. Thoreau's occasion was the publication of a series of scientific reports issued by the state of Massachusetts, but he opened this essay with a moving meditation on the restorative powers of nature rather than with a mention of the reports' practical value.

We associate nature writing with American Transcendentalism and consider Henry Thoreau the form's greatest exponent, even as we acknowledge others in this movement's circle and penumbra as (albeit less successful) contributors to the genre. Yet we often do so blithely, ignoring the difficulty of defining precisely what nature writing is, what constitutes Transcendentalist nature writing, and why one author is more successful at it than another. Faced with such thorny questions, one might throw up one's hands and quote Henry David Thoreau himself: “Some circumstantial evidence is very strong,” Ralph Waldo Emerson recalled him saying, “as when you find a trout in the milk,” a homely reference to the unscrupulous farmer who dilutes his cow's milk with stream water before he brings it to market (“Thoreau,” Trism 667). In other words, one “knows” nature writing, good nature writing, and Transcendentalist nature writing, when one sees it.

For more than a century some literary critics have bravely, if not fully convincingly, addressed these issues. One of the first twentieth-century commentators to do so, Philip Marshal Hicks, offered, in 1924, a very strict definition of the genre of nature writing. He would so designate an essay, he wrote, if it “is based upon, and has for its major interest the literary expression of scientifically accurate observations of the life history of the lower orders of nature, or of other natural objects.” His narrow construction eliminates from consideration “the essay inspired merely by an aesthetic or sentimental delight in nature in general; the narrative of travel, where the observation is merely incidental; and the sketch which is concerned solely with description of scenery.” He thus was interested primarily in “the extent to which the facts of natural history have been made the basis of literary treatment in essay form” (Hicks 6). Hicks offers little guidance, however, as to what precisely constitutes “literary” expression. Moreover, his confident dismissal of, say, the “narrative of travel” makes us wonder what to do with the essays in Thoreau's Cape Cod and The Maine Woods . Similarly, to discount the “sketch” seemingly leaves little room for Thoreau's “Winter's Walk” or “Autumnal Tints” (essays that Hicks does, however, treat).

Around the same time, Norman Foerster, writing in Nature in American Literature (1923), hazarded another, broader definition. “With only two or three exceptions,” he observed, “all of our major writers” merited study, for nearly all “have displayed a striking curiosity as to the facts of the external world—an intellectual conscience in seeking to know them with exactness and an ardent emotional devotion to nature because of her beauty or divinity.” He begins his study with William Cullen Bryant and John Greenleaf Whittier before addressing the Transcendentalists Emerson and Thoreau and their fellow traveler, Walt Whitman. That all of these and a raft of others discovered in nature (rather than in any organized creeds) the chief inspiration for their understanding of humanity's place in the universe makes them part of what Foerster terms the “naturalistic movement,” which indelibly defines American letters (xiii). To him, any nineteenth-century writer who saw and was moved by a wildflower, bird, or waterfall and labored to describe it was engaged in nature writing.

Despite such opposing definitions of the genre, we can locate with some specificity a particular group of writers who, taking their inspiration from the nexus of ideas associated with American Transcendentalism, purposefully set out to write about the natural world in a distinctive way. Here the contemporary literary historian and ecocritic Lawrence Buell is helpful. In The Environmental Imagination (1995) he treats many writers, from the eighteenth century to the present, who are linked by their desire “to investigate literature's capacity for articulating the nonhuman environment” and among whom he regards Thoreau as a touchstone for understanding and evaluating the American variant of “literary naturism” (Buell 10). Buell lends support to an opinion about Thoreau's prominence in this genre promulgated as early as the 1880s, when his friend H. G. O. Blake, entrusted with Thoreau's voluminous journals, published excerpts in volumes named after the four seasons, and literary critic Edwin P. Whipple claimed, in his rich evaluation of American literature, that Thoreau “penetrated nearer to the physical heart of Nature than any other American author” (111).

Buell's criteria for literary naturism are four. In the best of such work (again, exemplified in Thoreau's prose), he writes, “the nonhuman environment is present not merely as a framing device but as a presence that begins to suggest that human history is implicated in natural history.” Second, “the human interest is not understood to be the only legitimate interest.” Third, “human accountability to the environment is part of the text's ethical orientation.” Finally, “some sense of the environment as a process rather than as a constant or a given is at least implicit in the text” (Buell 7–8). Not all of these premises are necessarily found in each example of nature writing, but all in some variant underlie the most powerful and enduring examples of the form and contribute to the “environmental imagination.” If we add to Buell's list self-consciousness of the capabilities and limits of language for allowing one to write about nature in these ways, we approach an understanding of the achievement of what we might call the Thoreauvian school of “literary naturism,” as Buell terms it (431). But what within the Transcendentalist movement per se pushed its participants in such directions? And did others in it besides Thoreau contribute to and succeed at promulgating such discourse?

One thing is clear. When American Transcendentalism emerged in the early 1830s, the study of nature was not a chief concern of the coterie who embraced new currents in European philosophy and religion and applied them to their own situation as Unitarians. The contemporary debates in which they partook centreed on the manner and import of scriptural exegesis, as well as the implications of German Idealist philosophy on an understanding of consciousness and cognition. Such matters, and not the texture of one's relation to Nature and spirit, most exercised Frederic Henry Hedge, George Ripley, Orestes Brownson, and others whose writings and activities marked the earliest phase of American Transcendentalism (Gura 69–97). These individuals were drawn to the “New Thought” as a way to revivify a Christianity whose adherents were devoted to religious and social reform, not from a belief that a deeper understanding of nature brought one closer to the spiritual life.

The initial impetus in this latter direction came from Emerson's publication of Nature in 1836. Throughout the early 1830s he, too, was embroiled in religious controversy, but at about the same time he began to develop an interest in science, and on a subsequent trip to Europe after he resigned his pulpit at Boston's Second Church, he indulged this budding interest in the natural world. When he visited the renowned Jardin des Plantes in Paris, for example, he was much impressed by the complexity and order of the world's flora and fauna. His interest in scientific classification whetted, he visited places such as the Cabinet of Natural History at the Collège Royale de France and attended various lectures on science in Paris and London ( EmEL 1:3). When Emerson returned to the United States to begin a career on the lyceum boards, he made various aspects of “natural philosophy” the subject of his first four lectures ( EmEL 1:86).

His maiden effort, “The Uses of Natural History,” delivered to Boston's Natural History Society in the early fall of 1833, augured what he soon immortalized in Nature , that is, a belief that nature serves humankind in many ways, providing (among other things) material comfort, aesthetic satisfaction, moral instruction, a language for our thoughts and feelings, and, not least of all, a way to spiritual self-knowledge. “It is in my judgment,” he said to his audience at the Masonic Temple, “the greatest office of natural science…to explain man to himself.” Is there not, he continued, “a secret sympathy which connects man to all the animate and to all the inanimate things around him?” ( EmEL 1:23–24). If, as Emerson learned from Idealist philosophers like Friedrich von Schelling and Johann Gottlieb Fichte, an individual's consciousness is the centre from which all knowledge radiates, nature provides the mind's language and metaphors. Nature, Emerson concluded, is a language “put together into a most significant and universal sense,” and “every new fact we learn is a new word” (1:26). “I wish to learn this language,” he continued. “I am moved by strange sympathies. I say I will listen to this invitation, I will be a naturalist” (1:10).