93 Personal Identity Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best personal identity topic ideas & essay examples, ⭐ interesting topics to write about personal identity, ✅ simple & easy personal identity essay titles, ❓ research questions about identity.

- How Does Culture Affect the Self Identity Personal Essay The economic background, family relations and ethnic distinctions have contributed significantly to the personality trait of being a low profile person who is considerate of others.

- Personal Identity Under the Influence of Community In other words, how individuals are raised in society is essential in facilitating the ability to predict the conduct and even future roles within the group. The community values that are embraced and respected are […] We will write a custom essay specifically for you by our professional experts 808 writers online Learn More

- Music Role in Personal and Social Identities Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to answer the question ‘How does music contribute to personal and social identities?’ In answering this question, the paper will develop a comprehensive analysis of a number of […]

- Bernard Williams The Self and the Future and Psychological Continuity Theory of Personal Identity The researches and ideas of Bernard Williams are focused on the necessity of personal awareness about the experiment; “they [Person A and Person B] may even have been impressed by philosophical arguments to the effect […]

- Exploring a Personal Identity: What Defines Me as an Individual However, due to openness to new ideas and the ability to retain my cultural values, I have managed to shape my personal identity in a unique way that included both the core values of my […]

- Personal Identity & Self-Reflection In the reflection, Ivan examined his past life and the values that he had lived by in all of his life.

- Music and the Construction of Personal and Social Identities Despite the relative difference between the current and the past music experience, it is clear that music has increasingly been used in the construction of the youths’ identities.

- Respect and Self-Respect: Impact on Interpersonal Relationships and Personal Identity It is fundamental to human nature to want to be heard and listened to.indicates that when you listen to what other people say, you show them respect at the basic level.

- Recognizing Homosexuality as a Personal Identity According to Freud, all human beings are inherently bisexual, and homosexuality results from a malfunction in the process of sexual development.

- Personal Identity and Teletransportation Moreover, according to his views, one soul can live in several bodies in different lives, which resembles the concept of reincarnation, but at the same time, a person is not the same.

- Personal Identity Description The topic of personal identity has been presenting a matter of interest for numerous philosophers throughout the whole history of humanity.

- Leisure and Consumption: Cell Phones and Personal Identity Foley, Holzman, and Wearing aim to confirm the improvement of the quality of human experiences in public spaces through the application of cell phones.

- Personal Troubles: Deviance and Identity It is therefore a violation of social norms and failure to conform to these norms that are entrenched in the culture of the society.

- The Trouble Distinguishing Personal Identity From Perception of Reality The play of Arthur Miller Death of a Salesman is a brilliant example of how perception of reality influences personal identity.

- Sexuality and Personal Identity Deployment by Foucault Thesis Statement: Foucault suggests that the “deployment” of sexuality is closely connected with the deployment of integrity, which is the main principle of the social and political welfare of the state.

- Cultural and Personal Identity: Mothers and Shadows Memory knots, as the term, have been employed to refer to sites of humanity, sites in time, and sites of physical matter or geography.

- Importance of Personal Identity The first stated that the continuity of personality is reliant on the sameness of the body, while the opposing view proclaimed that only the sameness of the soul could signify the sameness of a person.

- Personal Identity Change and Identification Acts It appears that, instead of being referred to as the agent of ‘identity change’, the act of ‘identification’ should be discussed as one among many strategies, deployed by people on the way of trying to […]

- Personal Information Use and Identity Theft The study provided a national scale analysis of identity theft patterns in the United States between 2002 and 2006. The form of government documentation and benefits of fraud have contributed to the increase in identity […]

- Influence of the Fashion Attributes on the Social Status and Personal Identity In the end, the primary goal of the paper is to propose the suitable methodology and analysis of the information to find the relevant answer to the research question.

- A.A. Bronson’s Through the Looking Glass: His Personal Identity as a Canadian Artist Thus, his work Through the Looking Glass is the one of the best works that reflect the author’s vision of reality and the one that reflects the author’s sense of Canadian identity.

- Locke and Hume’s Discussions of the Idea of Personal Identity He argues that, the identity of a soul alone in an embryo of man is one and same that is the identity of it in a fully grown up man.

- Ship of Theseus and Personal Identity Regarding the Ship of Theseus, the ship changed a lot but it remained the same in terms of its properties. Equally, Y could be said to be the same as Z in terms of properties.

- Human Freedom and Personal Identity In demonstrating a working knowledge of psychoanalysis theory of consciousness and personal identity it is clear that being conscious of my personal endowments, gifts and talents, in addition to the vast know how and skill […]

- Psychological Foundations Behind Personal Identity

- Behind the Scenes: The Effects of Acting on Personal Identity

- Psychology: Personal Identity and Self Awareness

- The Personal Identity and the Psychology for the Child Development

- Defining Yourself and Personal Identity in Philosophy

- Personal Identity Challenges and Survival

- Cultural Diversity, Racial Intolerance, and Personal Identity

- Identification Process: Personal Contiguity and Personal Identity

- Personal Identity and Career Management

- Habits: Bridging the Gap Between Personhood and Personal Identity

- Personal Identity and Psychological Continuity

- Gender Roles and Personal Identity

- Personal Identity and Social Identity: What’s the Difference

- Three Theories of Personal Identity: The Body Theory, Soul Theory, and the Conscious Theory

- Personal Identity and the Definition of One’s Self

- Creative Industries and Personal Identity

- Psychological Continuity Theory of Personal Identity

- Generation Gap: Family Stories and Personal Identity

- How Antidepressants Affect Selfhood, Teenage Sexuality, and Personal Identity

- Personal Identity, Ethics, Relation, and Rationality

- Philosophical Views for Personal Identity, Inventory, and Reflection

- The Role and Importance of Personal Identity in Philosophy

- Personal Identity and Its Effect on Pre-procedural Anxiety

- Self-Discovery, Social Identity, and Personal Identity

- Psychological Continuity: Personal, Ethnic and Cultural Identity

- Person and Immortality: Personal Identity and Afterlife

- Cultural Norms, Language, and Personal Identity

- Socialization, Personal Identity, Gender Identity, and Terrorism

- Personal Identity: Bundle and Ego Theory

- Society and the Importance of a Unique Personal Identity

- Political Issues Through Personal Identity

- Conflict Between Personal Identity and Public Image

- Difference Between Personal Identity and Online Identity

- Noninvasive Brain Stimulation and Personal Identity: Ethical Consideration

- Personal Identity and Psychological Reductionism

- Bodily, Psychological and Personal Identity

- Memory Role in Personal Identity

- Unique and Different Types of Personal Identity

- Capabilities and Personal Identity: Using Sen to Explain Personal Identity in Folbre’s ‘Structures of Constraint’ Analysis

- Genetic Memory and Personal Identity

- Does Group Identity Prevent Inefficient Investment in Outside Options?

- Does Student Exchange Program Involve a Nations Identity?

- How America Hinders the Cultural Identity of Their Own Citizens?

- Are Education Issues Identity Issues?

- Are Persons With Dissociative Identity Disorder Responsible for Bad?

- How Do Advertisers Shape the Identity, Values, and Beliefs of Any Culture?

- What Factors Affect the Development of Ego Identity?

- Can Social Identity Theory Address the Ethnocentric Tendencies of Consumers?

- How Are Adolescents Responsible for Their Own Identity?

- Did the Mongols Create a More Diverse Islamic Identity?

- Why Corporate and White Collar Crimes Rarely Dealt in Criminal Courts Culture and Identity?

- What’s the Relationship Between Communication and Identity?

- Does Globalization Affect Our Culture Identity?

- What Does Ethnicity Affect a Person’s Identity?

- Does Trauma Shape Identity?

- What Does Identity Tell Us About Someone?

- How Beauty Standards Have Shaped Women’s Identity?

- How Has Bisexuality Been an Ambiguous Sexual Identity?

- What Does Identity Mean?

- How and Why Does Ethnic Identity Affect the Idea of ‘Beauty’ Cross-Culturally?

- Can Consumption and Branding Be Considered a Part of a Person’s Identity?

- What Has Caused Britain to Lose Its Sense of Identity?

- How Antidepressants Affect Selfhood, Teenage Sexuality, and Our Quest for Personal Identity?

- Does Identity Affect Aspirations in Rural India?

- Do Identity Contingencies Affect More Than Just One Race?

- Does Identity Incompatibility Lead to Disidentification?

- Does Social Inequality Affect a Person’s Identity?

- Why Is Identity Important in Education?

- Can People Choose Their Identity?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, March 2). 93 Personal Identity Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/personal-identity-essay-topics/

"93 Personal Identity Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 2 Mar. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/personal-identity-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2024) '93 Personal Identity Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 2 March.

IvyPanda . 2024. "93 Personal Identity Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/personal-identity-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "93 Personal Identity Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/personal-identity-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "93 Personal Identity Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/personal-identity-essay-topics/.

- Personality Psychology Research Topics

- Self-Reflection Research Topics

- Freedom Topics

- Personal Ethics Titles

- Self-Efficacy Essay Titles

- Identity Theft Essay Ideas

- Personal Values Ideas

- Cultural Identity Research Topics

- Self-Concept Questions

- Personality Development Ideas

- Moral Dilemma Paper Topics

- Psychology Questions

- Culture Topics

- Self-Awareness Research Topics

- Personal Growth Research Ideas

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Why Identity Matters and How It Shapes Us

Sanjana is a health writer and editor. Her work spans various health-related topics, including mental health, fitness, nutrition, and wellness.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/SanjanaGupta-d217a6bfa3094955b3361e021f77fcca.jpg)

Dr. Sabrina Romanoff, PsyD, is a licensed clinical psychologist and a professor at Yeshiva University’s clinical psychology doctoral program.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/SabrinaRomanoffPhoto2-7320d6c6ffcc48ba87e1bad8cae3f79b.jpg)

Verywell / Zoe Hansen

Defining Identity

- What Makes Up a Person's Identity?

Identity Development Across the Lifespan

The importance of identity, tips for reflecting on your identity.

Your identity is a set of physical, mental, emotional, social, and interpersonal characteristics that are unique to you.

It encapsulates your core personal values and your beliefs about the world, says Asfia Qaadir , DO, a child and adolescent psychiatrist at PrairieCare.

In this article, we explore the concept of identity, its importance, factors that contribute to its development , and some strategies that can help you reflect upon your identity.

Your identity gives you your sense of self. It is a set of traits that distinguishes you from other people, because while you might have some things in common with others, no one else has the exact same combination of traits as you.

Your identity also gives you a sense of continuity, i.e. the feeling that you are the same person you were two years ago and you will be the same person two days from now.

Asfia Qaadir, DO, Psychiatrist

Your identity plays an important role in how you treat others and how you carry yourself in the world.

What Makes Up a Person's Identity?

These are some of the factors that can contribute to your identity:

- Physical appearance

- Physical sensations

- Emotional traits

- Life experiences

- Genetics

- Health conditions

- Nationality

- Race

- Social community

- Peer group

- Political environment

- Spirituality

- Sexuality

- Personality

- Beliefs

- Finances

We all have layers and dimensions that contribute to who we are and how we express our identity.

All of these factors interact together and influence you in unique and complex ways, shaping who you are. Identity formation is a subjective and deeply personal experience.

Identity development is a lifelong process that begins in childhood, starts to solidify in adolescence, and continues through adulthood.

Childhood is when we first start to develop a self-concept and form an identity.

As children, we are highly dependent on our families for our physical and emotional needs. Our early interactions with family members play a critical role in the formation of our identities.

During this stage, we learn about our families and communities, and what values are important to them, says Dr. Qaadir.

The information and values we absorb in childhood are like little seeds that are planted years before we can really intentionally reflect upon them as adults, says Dr. Qaadir.

Traumatic or abusive experiences during childhood can disrupt identity formation and have lasting effects on the psyche.

Adolescence

Adolescence is a critical period of identity formation.

As teenagers, we start to intentionally develop a sense of self based on how the values we’re learning show up in our relationships with ourselves, our friends, family members, and in different scenarios that challenge us, Dr. Qaadir explains.

Adolescence is a time of discovering ourselves, learning to express ourselves, figuring out where we fit in socially (and where we don’t), developing relationships, and pursuing interests, says Dr. Qaadir.

This is the period where we start to become independent and form life goals. It can also be a period of storm and stress , as we experience mood disruptions, challenge authority figures, and take risks as we try to work out who we are.

As adults, we begin building our public or professional identities and deepen our personal relationships, says Dr. Qaadir.

These stages are not set in stone, rather they are fluid, and we get the rest of our lives to continue experiencing life and evolving our identities, says Dr. Qaadir.

Having a strong sense of identity is important because it:

- Creates self-awareness: A strong sense of identity can give you a deep sense of awareness of who you are as a person. It can help you understand your likes, dislikes, actions, motivations, and relationships.

- Provides direction and motivation: Having a strong sense of identity can give you a clear understanding of your values and interests, which can help provide clarity, direction, and motivation when it comes to setting goals and working toward them.

- Enables healthy relationships: When you know and accept yourself, you can form meaningful connections with people who appreciate and respect you for who you are. A strong sense of identity also helps you communicate effectively, establish healthy boundaries, and engage in authentic and fulfilling interactions.

- Keeps you grounded: Our identities give us roots when things around us feel chaotic or uncertain, says Dr. Qaadir. “Our roots keep us grounded and help us remember what truly matters at the end of the day.”

- Improves decision-making: Understanding yourself well can help you make choices that are consistent with your values, beliefs, and long-term goals. This clarity reduces confusion, indecision, and the tendency to conform to others' expectations, which may lead to poor decision-making .

- Fosters community participation: Identity is often shaped by cultural, social, political, spiritual, and historical contexts. Having a strong sense of identity allows you to understand, appreciate, and take pride in your cultural heritage. This can empower you to participate actively in society, express your unique perspective, and contribute to positive societal change.

On the other hand, a weak sense of identity can make it more difficult to ground yourself emotionally in times of stress and more confusing when you’re trying to navigate major life decisions, says Dr. Qaadir.

Dr. Qaadir suggests some strategies that can help you reflect on your identity:

- Art: Art is an incredible medium that can help you process and reflect on your identity. It can help you express yourself in creative and unique ways.

- Reading: Reading peoples’ stories through narrative is an excellent way to broaden your horizons, determine how you feel about the world around you, and reflect on your place in it.

- Journaling: Journaling can also be very useful for self-reflection . It can help you understand your feelings and motivations better.

- Conversation: Conversations with people can expose you to diverse perspectives, and help you form and represent your own.

- Nature: Being in nature can give you a chance to reflect undisturbed. Spending time in nature often has a way of putting things in perspective.

- Relationships: You can especially strengthen your sense of identity through the relationships around you. It is valuable to surround yourself with people who reflect your core values but may be different from you in other aspects of identity such as personality styles, cultural backgrounds, passions, professions, or spiritual paths because that provides perspective and learning from others.

American Psychological Association. Identity .

Pfeifer JH, Berkman ET. The development of self and identity in adolescence: neural evidence and implications for a value-based choice perspective on motivated behavior . Child Dev Perspect . 2018;12(3):158-164. doi:10.1111/cdep.12279

Hasanah U, Susanti H, Panjaitan RU. Family experience in facilitating adolescents during self-identity development . BMC Nurs . 2019;18(Suppl 1):35. doi:10.1186/s12912-019-0358-7

Dereboy Ç, Şahin Demirkapı E, et al. The relationship between childhood traumas, identity development, difficulties in emotion regulation and psychopathology . Turk Psikiyatri Derg . 2018;29(4):269-278.

Branje S, de Moor EL, Spitzer J, Becht AI. Dynamics of identity development in adolescence: a decade in review . J Res Adolesc . 2021;31(4):908-927. doi:10.1111/jora.12678

Stirrups R. The storm and stress in the adolescent brain . The Lancet Neurology . 2018;17(5):404. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30112-1

Fitzgerald A. Professional identity: A concept analysis . Nurs Forum . 2020;55(3):447-472. doi:10.1111/nuf.12450

National Institute of Standards and Technology. Identity .

By Sanjana Gupta Sanjana is a health writer and editor. Her work spans various health-related topics, including mental health, fitness, nutrition, and wellness.

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Philosophy

Essay Samples on Personal Identity

Personal identity encompasses the fundamental question of “Who am I?” It delves into the complex layers of our individuality, examining the factors that define and distinguish us as unique beings. Exploring personal identity involves introspection and contemplation of various aspects, such as our beliefs, values, experiences, and relationships. It invites us to unravel the intricacies of our self-perception and the influences that shape our identities in personal identity essay examples.

How to Write an Essay on Personal Identity

When crafting an essay on personal identity, it is essential to begin by defining the term and setting the stage for further exploration. Establish a strong thesis statement that outlines your perspective on the topic. Consider incorporating personal anecdotes or real-life examples to illustrate your points effectively. Remember to maintain a logical flow of ideas, guiding your readers through the intricate terrain of personal identity. Conclude your essay by summarizing key findings and offering thought-provoking insights or suggestions for further exploration of the topic.

To create an engaging and comprehensive personal identity essay, delve into various philosophical, psychological, and sociocultural perspectives on personal identity. Explore influential theories, such as John Locke’s bundle theory or David Hume’s notion of the self as a bundle of perceptions. Analyze the impact of cultural and societal factors on shaping personal identities, highlighting the interplay between individual agency and external influences.

- Information

Drawing upon reputable sources and research studies will lend credibility to your essay, allowing readers to explore different perspectives and deepen their understanding of personal identity.

Whether you are seeking free essay on personal identity or aiming to develop your own unique viewpoint, our collection of essays will serve as an invaluable resource.

How Does Society Shape Our Identity

How does society shape our identity? Society acts as a powerful force that molds the intricate contours of our identities. As individuals, we are not isolated entities; we are products of the societies we inhabit. This essay explores the dynamic interplay between society and identity,...

- Personal Identity

How Does Family Influence Your Identity

Family is a powerful force that weaves the threads of our identity. The relationships, values, and experiences within our family unit play a significant role in shaping who we become. This essay delves into how family influences our identity, from the formation of core beliefs...

Exploring the Relationship Between Illness and Identity

In this essay I will be exploring the relationship between illness and identity, drawing on specific examples documented in the article ‘Disrupted lives and threats to identity: The experience of people with colorectal cancer within the first year following diagnosis’, by Gill Hubbard, Lisa Kidd...

Evolving Identities: The Concept of Self-Identity and Self-Perception

For centuries psychologists, like Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung have discussed the concept of self-identity and self-perception. In social sciences, identity refers to an individual's or party's sense of who they are and what defines them. As the human condition, we have evolved to form...

- Self Identity

Free Cultural Identity: Understanding of One's Identity

The term ‘identity’ is vaguely defined or given a specific definition which means that we, as people, are constantly on this quest for identity, a validation of who we are. We do not want to be influenced or touched by society’s ideas or its ways...

- Cultural Identity

Stressed out with your paper?

Consider using writing assistance:

- 100% unique papers

- 3 hrs deadline option

My Cultural Identity and Relationship with God

Cultural identity influences every characteristic of a person, both outward and inward. My cultural identity consists of various factors. I was born and raised in the United States, specifically in Tennessee. While I was born in Nashville, I lived most of my life in Athens....

My Cultural Identity and Preserving Ancestors' Traditions

I'm a multicultural person living in the United States. Born in the Philippines; I was wrongly recognized as a Latino in my school from time to time. Both of my parents are Filipino, and I both speak fluent English and Tagalog, but I don't speak...

Gregor Samsas` Burden In "The Metamorphosis" By F. Kafka

Everyone has dreamed of a crazy dream that made them go crazy as it was unbelievable, but what you will do if that dream turned out to be a reality that you are living? “The metamorphosis” is a short novella written by Franz Kafka which...

- The Metamorphosis

Reflections On Personal Intercultural Experience

Intercultural experience has introduced me to new ideas, revealed layers of concepts I was previously familiar with, and modified my original perceptions of particular notions. The course has allowed me to re-establish my feelings, thoughts, and opinions comprehensively, by encouraging reflection on my instinctive communicative...

- Intercultural Communication

Literature of African Diaspora as a Postcolonial Discourse

Literature of diaspora as a postcolonial discourse addresses issues such as home, nostalgia, formation of identity and to the interaction between people in diaspora and the host society, the center and the margin. Sufran believes that ‘diaspora’ is used as a ‘metaphoric designation’ to describe...

- African Diaspora

- Anthropology

The Ideology of Giving People Status or Reward

A meritocratic society is based on the ideology of giving people status or reward based on what they achieve rather than their wealth or social position. However, it could be argued that a meritocratic is just, and arguments that a meritocratic society is not just....

- Just Society

Features And Things That Shape Your Identity

“Who am I?”, “What is my identity?” these are the two inquiries I frequently ask myself. In my opinion, identity can be described as who you truly are or what distinguished from others. I am no different from my classmates. I go to school, eat,...

- Individual Identity

Identity Crisis: What Shapes Your Identity

Your Identity is your most valuable possession, protect it (Elastic Girl). Once in our lifetime, we ask ourselves this question that is difficult to answer. Who are we? What makes up my personality? These type of self-questions make us think about ourselves. Knowing our identity...

- Finding Yourself

My Passion And Searching What You Are Passionate About

What does being passionate even mean well being passionate means showing or caused by strong feelings or a strong belief. In that case, the music is what I’m passionate about. I’ve loved listening to music for as long as I can remember. Personally I feel...

The Importance Of Inner Beauty Over Outer Beauty

Human beings identify items or other human beings as beautiful if they possess traits that they commend, would like to possess, or features they find remarkable. Substance is beautiful if it is special in a favorable way; if it is interesting to look at; something...

- Physical Appearance

The Exterior Beauty Is Superior To Inner Beauty

The word ‘beauty’ looks just like a simple word, but it has a complex meaning; people give it a lot of definitions based on their own prejudice. This word is a magic world of characteristics which make each person unique; attributes that make us special...

What Book Of Matthew Teaches About Being Ourselves

Matthew 9:9-13 It's easy to go through life wearing different masks. We pretend that everything is ok. We’re more concerned about the outside, what people are going to think, our image. It takes a lot of work to deal with the inner issues: character, motives,...

- Being Yourself

- Biblical Worldview

Theme of Self-Identity in the Graphic Novels American Born Chinese by Gene Luen Yang, and Skim by Mariko and Jillian Tamaki

The coming of age genre is reflective of the life-changing moments in the lives of every growing adolescent. The stories share a mixture of minor yet pivotal events that allow the readers to see themselves in a moment where they are experiencing numerous emotions that...

- American Born Chinese

Factors That Affected the Formation of My Personal Identity

Personal identity is a difficult topic, especially in the current time where we are assailed by internet trends challenging us to compromise and change our identity to fit in. One of the biggest facets of my identity is the fact that I have lived in...

How Child Beauty Pageants Ruin Self Image of Younger Population

Self image is a big problem today, especially with social media being such a big part of our lives. Beauty pageants are a big part of this problem and is making it even worse. Beauty pageants can cause a lot of mental problems. It must...

- Child Beauty Pageants

- Child Psychology

Fictional and Cultural Analysis of Obasan in Japanese Culture

Holistic thinking allows for the highest benefit in all areas of a healthy life and planning for or taking action to support the healthiest outcome with balance in all areas. The term 'holistic thinking” in the Japanese culture refers to a picture of mentality in...

The Speaker’s Conflict with Identity in Neruda’s “We Are Many”

The problem of self-identification is a frequent topic for reflection by philosophers and psychologists. Each person can express himself in different ways in different conditions and situations. The speaker of Pablo Neruda’s “We Are Many” is very puzzled by his own uncertain identity and wants...

- Pablo Neruda

House of Mirth: The Causes of Failure in the Narrative

Lily Bart is a terrible person. She's a single-minded buffoon characterized by hypocrisy, gluttony, and greed. She's not only ignorant and lazy but proud of her ignorance and defensive of her laziness. So, how do I think I can get away with talking about her...

- The House of Mirth

Self-Acceptance and Identity in The House of Mirth

My thoughts when it comes to the subject of 'Is House of Mirth feminist?' is that this is ultimately the wrong question to ask because when you're looking at anything and asking 'Is ______ feminist?', you are asking the wrong question. This is the wrong...

The Effects of Anger on Other Human Emotions

Anger is like a drug, addictive. Everyone gets those feelings everyday of jealousy or comparison; or maybe someone says something that rubs you the wrong way. Anger can have many effects on a person. While mainly effecting someone’s emotions, anger can also cause a strain...

- Human Nature

The Search for the True Identity of Richard III in a Play

Looking for the resonances and dissonances between texts allows audiences to understand a textual conversation, which acts as a vehicle through which we evaluate changes in contexts, values and interpretations of texts. The resonances between William Shakespeare's tragedy King Richard III (1592) and Al Pacino's...

- Richard III

The Search for Identity in What You Pawn I Will Redeem

In the story, “What You Pawn I Will Redeem” by Sherman Alexie, the author describes Jackson’s notion of Identity by introducing himself as a homeless, middle-aged, alcoholic Indian man. When he describes his life before becoming homeless, he doesn’t glamorize about his past. Before talking...

- Sherman Alexie

- What You Pawn I Will Redeem

My Journey Of Learning To Love My Body And Believe In Myself

My smile is like the sun, warm and bright. My eyes, a deep brown, as brown as the color of the earth after torrential rains. My skin, as rich and swarthy as the earth’s soil. Freckles, scattered in the most random places; on my back,...

- Believe in Myself

- Personal Life

Forensic Psychology: Offender Profiling and Human Identification

The application of forensic psychology into investigation, prosecution and working with victims has undergone several theories. The psychology of detection has used many methods including Offender Profiling, Eyewitness Testimony and Interviewing. Offender profiling was initially introduced by Federal Bureau Investigation (FBI) supplying a possible description...

- Forensic Psychology

Themes of Perseverance and Identity in The Secret Life of Bees

“The nation saw itself in the midst of a new war in Vietnam, and culture wars were being fought at home, with the civil rights movement escalating and new youth subcultures emerging that rejected the values of the past...Over the course of the decade, public...

Moonlight: Influences on the Formation of Protagonist's Identity

Moonlight – a movie directed by Barry Jenkins was one of the most beautiful and heart – wrenching masterpiece that I have ever seen. The film is set in Miami in 1980s, the peak ages when abject poverty, drug addiction, violence and social degradation occurred...

Making a Statement of One's Identity in 'A&P'

John Updike’s short story entitled, “A & P,” is written through the eyes of the main character Sammy, who is a nineteen-year-old checkout clerk at the local grocery store. Throughout the story, Sammy is very descriptive in his introduction of the other characters that come...

Brave New World: Loss of Human Identity Due to Technological Progress

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley is a dystopian novel published in 1932 in England. This unorthodox view of society and government led this book to be banned in Ireland and Australia and is currently within the top 10 most wanted banned books in America....

- Brave New World

The Relationship Between Illness & Person’s Identity

Bibliographical disruption of illness can be understood as how illness affects a person’s identity, social life and how you view yourself (Sontag, 1979). The essay will be focusing on greater sense of those identities with which illness may interact, including the way such identities may...

How Identity Is Presented In TCP And Sula

Identity is a factor that the characters of both texts lack due to their oppressive states. Oppression which hinders the characters from attaining their self-identity. It is through the relationships that the characters form with each other is what enables them to attain their sense...

- The Color Purple

Taking Judgement In A Positive Way

Most people judge others based on their own inner insecurities. This has been a universal issue which causes most specifically body issues. These issues grow based on how one presents themselves. Every individual has their own story and own experiences which enables the way one...

- Personal Qualities

- Positive Psychology

An Event In My Life Having Impacted My Identity

A big influence that really made an impact in my identity formation is my dad leaving us. Him not being there made it really hard, not only on me and my sister but my mom as well. My dad isn’t the best person in the...

- Personal Experience

Analysis Of Risk Attitudes And Financial Decisions Of Millennial Generation

As a result of the financial turmoil at the beginning of the twenty first century, literature has prompted growing interest in how young individuals, that just started to interact with credit markets and accumulate assets, have fared in the wake of Great Recession. In more...

- Decision Making

- Millennial Generation

Breakdown Of The Constructed Masculine Ideals

These constructed notions of masculine identities were broken soon when these men came face to face with the dehumanizing horrors of the war. The psychological torture due of the trench warfare was something that they had never witnessed before. One poem that describes the breakdown...

- Masculinity

Individual’s Identity versus Social Norms: Why Do We Get Judged

Defined by the Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, personal identity is the subject that deals with the philosophical questions that stem out about oneself as a result of that person being human. Personal identity is a complex cocktail of different components that are always being stirred...

My Social Identity: Analysis and Reflection

In class, we participated in a “Social Identity Wheel” activity. On the wheel, that is based on the seven categories of “otherness” that is commonly experienced in the U. S. American society which is spoken about in Tatum’s chapter on “The Complexity of Identity, ‘Who...

- Money and Class in America

Teacher As Professional: Defining Personal Identity Assignment

Lifelong learning is what I truly put my heart into when it comes to being an educator. There are strengths and weaknesses we come across as we discover ourselves. Self-improvement is important as an educator to overcome challenges and to seek for effectiveness for student...

The Impact Of Language On Identity

Our tongue possesses the ability to express intimate thoughts and convey emotions. The cornerstone of communication is language, for without it, self-expression would be humdrum. The author of “Mother Tongue”, Amy Tan along with Eudora Welty who penned “One Writer’s Beginnings” evolved into extraordinary writers...

- Language Diversity

- Mother Tongue

The Importance Of Leaving A Legacy

All leaves dance. Shira Tamir says “Anyone who thinks fallen leaves are dead has never watched them dancing on a windy day.” Leaves do not just trot or hop, more importantly leaves do not just fall. They are experts in the world's most beautiful dance...

- Personal Philosophy

The Theory Of Our Identity & Self Concept

We hold several identities which fluctuate at different given points across time and space. A person will have numerous identities such as mother, professor, wife, helpful neighbor or friend. Each position has its own value and expectations that they are obliged to perform, and the...

- Self Awareness

Understanding My Sense Of Identity

Any sixteen year olds struggle to know themselves, but at least they can say they know every uncle, cousin, second cousin on both sides of their family tree. Even though I’m adopted, I thought I did too. It was a typical summer morning, and my...

We Are Too Sensitive, Here's Why

The discussion at hand is about us, every single one of us that has or will have an impact on our society. I’m here to talk about what we all proclaim to be the most progressive, open-minded, and free-spirited group of individuals, us. I, Lash,...

- Human Behavior

What Shapes My Personal Identity

Jarod Kintz said “If I told you I’ve worked to get where I’m at. I’d be lying, because I have no idea where I am right now.” Where am I? Who am I? Why do I like the things I choose? Is it where I...

Best topics on Personal Identity

1. How Does Society Shape Our Identity

2. How Does Family Influence Your Identity

3. Exploring the Relationship Between Illness and Identity

4. Evolving Identities: The Concept of Self-Identity and Self-Perception

5. Free Cultural Identity: Understanding of One’s Identity

6. My Cultural Identity and Relationship with God

7. My Cultural Identity and Preserving Ancestors’ Traditions

8. Gregor Samsas` Burden In “The Metamorphosis” By F. Kafka

9. Reflections On Personal Intercultural Experience

10. Literature of African Diaspora as a Postcolonial Discourse

11. The Ideology of Giving People Status or Reward

12. Features And Things That Shape Your Identity

13. Identity Crisis: What Shapes Your Identity

14. My Passion And Searching What You Are Passionate About

15. The Importance Of Inner Beauty Over Outer Beauty

- Ethics in Everyday Life

- Euthyphro Dilemma

- Virtue Ethics

- Psychoanalytic Theory

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

Which program are you applying to?

Accepted Admissions Blog

Everything you need to know to get Accepted

August 26, 2022

College Admissions: Mining Identity for College Essays, Personal Statements

Langston Hughes begins his poem “Theme for English B” this way:

The instructor said:

Go home and write a page tonight. And let that page come out of you- Then it will be true.

I wonder if it’s that simple?

“Tell us about yourself”

When colleges instruct you to “Tell us about yourself,” it may sound simple, but it is not. Sarah Myers McGinty, of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, conducted a study in 1998 to determine the importance of the college application essay and students’ ability to complete it successfully. She found that while admissions officials viewed the essay as “somewhat important,” students found themselves unprepared to write it. In The Chronicle of Higher Education (1/25/02), McGinty says, “I knew that students felt comfortable talking about the most significant event in the life of Jay Gatsby. But many felt ill-at-ease when asked about the most significant event in their own lives.” After all, as many students will attest, they have never done anything like this before. Students are rarely asked to write personal narratives.

So how do you tell admissions officers about yourself in a true and convincing way? First, you need to “mine” various areas of your identity to discover what makes you an individual . We’re not talking strip-mining, where you just pull up whatever’s on the surface. We’re talking about digging to see what’s below the surface. That takes time and commitment, but in the end, you may strike gold.

Writing is discovery. You cannot write an essay without first discovering what you have to say. You are setting out to discover what has made you who you are. Keep a journal as you explore your past and your present. These jottings and written wanderings are not your essay, but some will serve as the essay’s building materials. (Others might be valuable points for reflection more generally!)

9 aspects of identity

Some areas of your identity to explore include:

- Sexual Orientation

Events in a college essay

The events of your life, whether big and small, successful or failed, shape you as an individual.

In other words, your identity is, in part, formed through a series of events, which can be narrated to tell a story that gives the reader a glimpse of who you are. Telling a good story involves strong description (including the colors, sounds, and smells of your life), action (including movement, dialogue or internal monologue, etc); and reflection (including decisions you made, thoughts or feelings you had during an event, and your reflection afterwards).

Help transport your reader into your story by showing what it was like. And, tell the reader what this anecdote says about you as a person.

Which experience to pick? Looking at a few colleges’ essay questions may provide you with some ideas (emphases added):

- The Common Application asks you to: “Recount a time when you faced a challenge, setback, or failure. How did it affect you, and what did you learn from the experience?’

- The mission of Harvard College is to educate our students to be citizens and citizen-leaders for society. What would you do to contribute to the lives of your classmates in advancing this mission?

- Dartmouth: The Hawaiian word mo’olelo is often translated as “story” but it can also refer to history, legend, genealogy, and tradition. Use one of these translations to introduce yourself.

- Columbia students take an active role in improving their community, whether in their residence hall, classes or throughout New York City. Their actions, small or large, work to positively impact the lives of others. Share one contribution that you have made to your family, school, friend group or another community that surrounds you.

Your experience does not have to be massively life-altering (not all of us have huge turning points in our lives), but can be one of the many little events in our lives that make us see ourselves and the world a bit differently. The time your classmates offered you a stolen test and you refused it. Seeing the ocean for the first time at age 15. Learning to drive or ski or swim. Notice, too, that all of the essay questions ask you both to tell the story of an experience and also to reflect on the significance or impact of the event.

Here are some ideas for getting started on these and related prompts:

Passions in a college essay

Your passion for certain causes or issues, as well as your hobbies or interests, show who you are. How do you spend your free time? What excites you? Concerns you? Enrages you? What have you done to translate this passion into action? I know a student whose concern over the Middle East conflict led him to distribute to all of his classmates bracelets commemorating those who have died in the conflict. His essay on the topic worked because his passion led him to action, and his writing conveyed his passion. Another student explored how his childhood Lego hobby was a springboard to his building robots in national competitions. I taught a young woman whose frustration over male-female relations in her school led her to start a Gender Issues discussion group. I know people who could write fascinating essays on their obsession with beads, their rock collection, or bike riding. Perhaps you think it’s less-than-admirable to say that you spend every Saturday afternoon watching classic movies, but if you can intelligently reflect on why you love old movies and what it shows about you, it could be a worthwhile topic.

People in a college essay

Begin by listing people in your life who have nurtured your identity. In addition to your family members, you may list instructors, coaches, teachers, or neighbors. After you make a list, decide which person or people you could write about most engagingly. Some applications ask you to write about a person; some just leave the door open for you by telling you to explore a topic of choice. You might begin your exploration by reflecting on your family and how it has affected who you have become. Focus on the details of one or two members of your family-their appearance, their habits, their activities, and their interactions with you. Think of a story that encapsulates a relationship. Consider exploring your family’s cultural heritage, traditions, or foods. Bring the people you depict to life, and give them color, personality, a voice. Provide anecdotes about these family members or other important people in your life.

Places in a college essay

Perhaps a place has gotten under your skin because you’ve spent so much time there. Perhaps you’ve worked on your grandfather’s farm in Wisconsin each summer since you were ten. Perhaps you attend a school unlike most schools in the nation, one in an unusual setting or with an unusual philosophy. Perhaps you spent a semester on sabbatical with your parents in Zimbabwe, and once you came back, everything looked different. Place can be a character, and you can tell a vivid story about how it helped shape you . Conversely, you might have spent time in a place only briefly (one night on a camping trip, for example); or, the place you visited or lived in might have been lousy: decrepit, dirty, scary, upsetting. All of the above are fair game: the point is to use the experience as a vehicle for talking about who you are and how you experience the world around you.

Religion in a college essay

For some people, religion is integral to their lives and identities. Even so, you may consider religion a “touchy” subject. You may fear that the reader won’t like your religion. Don’t let that stop you if you have honest stories and reflections to relate. Consider writing a personal statement that reveals your thoughts about religion through a vivid story or series of anecdotes.

Race in a college essay

For some, their racial identity- and perhaps the persecution they’ve experienced or the minority status they have had- is an important part of who they are. Writing about moments of challenges and what you did to be a leader, to hold your ground, or to educate others, can let the reader get a glimpse of your strongest qualities. Colleges seek students from diverse backgrounds and in possession of strong characters, so don’t be afraid to let both of those qualities shine through.

Gender in a college essay

Does your gender identity feel significant to who you are– to your experiences, your community, your identity? For some, being a woman, being transgender, or being genderqueer can be essential to who they are and their experiences. You might consider writing an essay about going to an all girls’ Catholic school; being the only boy in a household of many sisters; experimenting with multiple pronouns. Just remember: this essay should be about more than a certain experience alone; it is also about what your thoughts, decisions, and actions say about who you are and what is important to you.

Disability/different abilities in a college essay

While so often viewed as a setback, your life with a disability – whether since birth or due to an illness or an event later in life– can help distinguish you or a sea of similarly-abled peers. How have you embraced, overcome, or given voice to your disability or those of others? What abilities have you cultivated or discovered because of it? How have you both coped, and strived , with your disability, and what does this say about your character and commitments?

Sexual orientation in a college essay

Perhaps your sexual identity has played a role in your life, inspiring you to form interests in certain writers or ideas; to work on an inclusive marriage campaign; to lead your school’s Gay Straight Alliance. Whether your identity or that of a loved one, be sure to keep yourself center-stage as you use the idea of sexual orientation to speak to your values, passions, and interests.

You care about your essay because it will help you get into Wonderful U. Fair enough. But you will also gain a bonus along the way: self-realization as you step across the threshold from childhood to adulthood; A sense of who you are and what made you that way; some insight into your desires for the future. Happy digging.

(Once you’ve mined for ideas, visit other sections of the Accepted website, which offers lots of essay writing tips and sample student essays to help you pull your essay together.)

If you would like the guidance and support of experienced college admissions consultants as you explore your identity and develop an application strategy, Accepted is here to help. We offer a range of services that can be tailored exactly to your needs. Our singular goal is to help you gain admittance to the college of your choice!

Accepted has helped applicants gain acceptance to top colleges and universities for 25 years. Our team of admissions consultants features former admissions committee members and highly experienced college admissions consultants who have guided our clients to admission at top programs including Princeton, Harvard, Stanford, Columbia, MIT, University of Chicago, and Yale. Want an admissions expert to help you get Accepted? Click here to get in touch!

Related Resources:

- Different Dimensions of Diversity , a podcast episode

- The Essay Whisperer: How to Write a College Application Essay

- Common App Essay Prompts 2022-2023: Tips for Writing Essays That Impress

About Us Press Room Contact Us Podcast Accepted Blog Privacy Policy Website Terms of Use Disclaimer Client Terms of Service

Accepted 1171 S. Robertson Blvd. #140 Los Angeles CA 90035 +1 (310) 815-9553 © 2022 Accepted

Cultural Identity Essay

27 August, 2020

12 minutes read

Author: Elizabeth Brown

No matter where you study, composing essays of any type and complexity is a critical component in any studying program. Most likely, you have already been assigned the task to write a cultural identity essay, which is an essay that has to do a lot with your personality and cultural background. In essence, writing a cultural identity essay is fundamental for providing the reader with an understanding of who you are and which outlook you have. This may include the topics of religion, traditions, ethnicity, race, and so on. So, what shall you do to compose a winning cultural identity essay?

Cultural Identity Paper: Definitions, Goals & Topics

Before starting off with a cultural identity essay, it is fundamental to uncover what is particular about this type of paper. First and foremost, it will be rather logical to begin with giving a general and straightforward definition of a cultural identity essay. In essence, cultural identity essay implies outlining the role of the culture in defining your outlook, shaping your personality, points of view regarding a multitude of matters, and forming your qualities and beliefs. Given a simpler definition, a cultural identity essay requires you to write about how culture has influenced your personality and yourself in general. So in this kind of essay you as a narrator need to give an understanding of who you are, which strengths you have, and what your solid life position is.

Yet, the goal of a cultural identity essay is not strictly limited to describing who you are and merely outlining your biography. Instead, this type of essay pursues specific objectives, achieving which is a perfect indicator of how high-quality your essay is. Initially, the primary goal implies outlining your cultural focus and why it makes you peculiar. For instance, if you are a french adolescent living in Canada, you may describe what is so special about it: traditions of the community, beliefs, opinions, approaches. Basically, you may talk about the principles of the society as well as its beliefs that made you become the person you are today.

So far, cultural identity is a rather broad topic, so you will likely have a multitude of fascinating ideas for your paper. For instance, some of the most attention-grabbing topics for a personal cultural identity essay are:

- Memorable traditions of your community

- A cultural event that has influenced your personality

- Influential people in your community

- Locations and places that tell a lot about your culture and identity

Cultural Identity Essay Structure

As you might have already guessed, composing an essay on cultural identity might turn out to be fascinating but somewhat challenging. Even though the spectrum of topics is rather broad, the question of how to create the most appropriate and appealing structure remains open.

Like any other kind of an academic essay, a cultural identity essay must compose of three parts: introduction, body, and concluding remarks. Let’s take a more detailed look at each of the components:

Introduction

Starting to write an essay is most likely one of the most time-consuming and mind-challenging procedures. Therefore, you can postpone writing your introduction and approach it right after you finish body paragraphs. Nevertheless, you should think of a suitable topic as well as come up with an explicit thesis. At the beginning of the introduction section, give some hints regarding the matter you are going to discuss. You have to mention your thesis statement after you have briefly guided the reader through the topic. You can also think of indicating some vital information about yourself, which is, of course, relevant to the topic you selected.

Your main body should reveal your ideas and arguments. Most likely, it will consist of 3-5 paragraphs that are more or less equal in size. What you have to keep in mind to compose a sound ‘my cultural identity essay’ is the argumentation. In particular, always remember to reveal an argument and back it up with evidence in each body paragraph. And, of course, try to stick to the topic and make sure that you answer the overall question that you stated in your topic. Besides, always keep your thesis statement in mind: make sure that none of its components is left without your attention and argumentation.

Conclusion

Finally, after you are all finished with body paragraphs and introduction, briefly summarize all the points in your final remarks section. Paraphrase what you have already revealed in the main body, and make sure you logically lead the reader to the overall argument. Indicate your cultural identity once again and draw a bottom line regarding how your culture has influenced your personality.

Best Tips For Writing Cultural Identity Essay

Writing a ‘cultural identity essay about myself’ might be somewhat challenging at first. However, you will no longer struggle if you take a couple of plain tips into consideration. Following the tips below will give you some sound and reasonable cultural identity essay ideas as well as make the writing process much more pleasant:

- Start off by creating an outline. The reason why most students struggle with creating a cultural identity essay lies behind a weak structure. The best way to organize your ideas and let them flow logically is to come up with a helpful outline. Having a reference to build on is incredibly useful, and it allows your essay to look polished.

- Remember to write about yourself. The task of a cultural identity essay implies not focusing on your culture per se, but to talk about how it shaped your personality. So, switch your focus to describing who you are and what your attitudes and positions are.

- Think of the most fundamental cultural aspects. Needless to say, you first need to come up with a couple of ideas to be based upon in your paper. So, brainstorm all the possible ideas and try to decide which of them deserve the most attention. In essence, try to determine which of the aspects affected your personality the most.

- Edit and proofread before submitting your paper. Of course, the content and the coherence of your essay’s structure play a crucial role. But the grammatical correctness matters a lot too. Even if you are a native speaker, you may still make accidental errors in the text. To avoid the situation when unintentional mistakes spoil the impression from your essay, always double check your cultural identity essay.

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

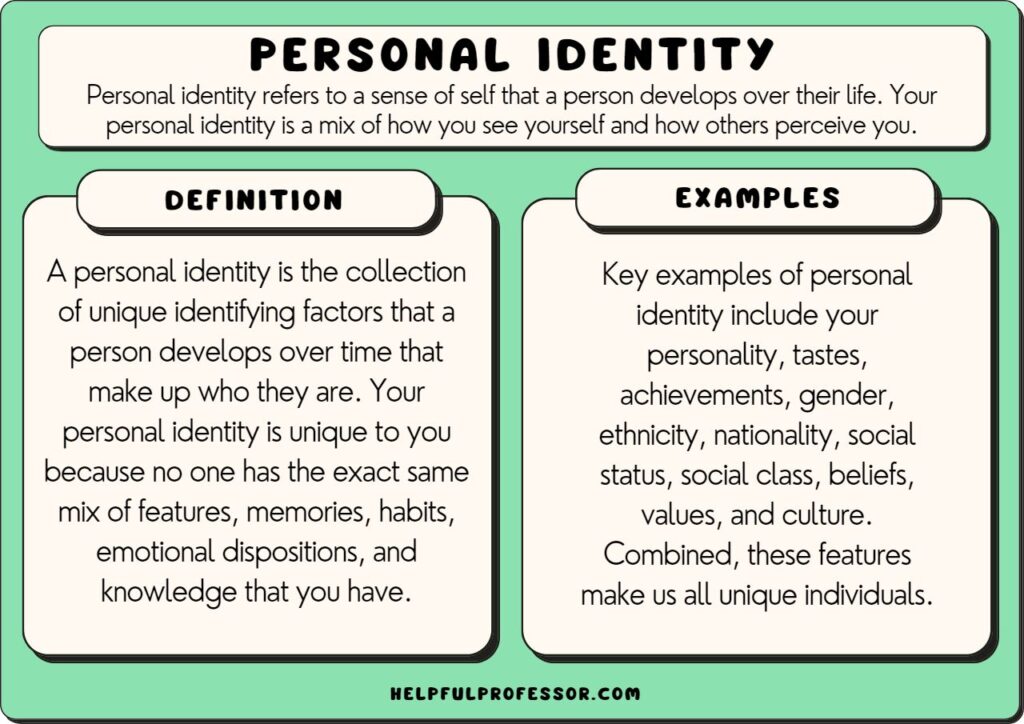

65 Personal Identity Examples

Personal identity refers to a sense of self that a person develops over their life. Your personal identity is a mix of how you see yourself and how others perceive you.

Key examples of personal identity include your personality, achievements, gender, ethnicity, nationality , social status, social class, beliefs, values, and culture. Combined, these features (along with others – see below) make us all unique individuals.

Personal Identity Examples

- Ability and Disability

- Achieved Status

- Ascribed Status (Born Status Features)

- Aspirations

- Awards and Recognition from Society (See Also: Achieved Status)

- Birth Order

- Career and Profession

- Citizenship Status

- Childhood Experiences

- Cultural Practices

- Cultural Values

- Current Occupation

- Educational Level

- Emotional Intelligence

- Family Role

- Family Traditions

- Friend Groups

- Geographical Identification (Rural, Ocean, City, etc.)

- Group Memberships

- Health Status

- Hopes and Dreams

- Immigrant Status

- Indigenous Status

- Intelligence

- Languages Spoken

- Nationality

- Optimism (or Pesimism)

- Parental Status

- Past Occupations

- Personal Achievements

- Personal Preferences

- Personality

- Philosopical Beliefs

- Physical Characteristics (Appearance)

- Professional Achievements

- Relationship Status

- Sociability (e.g Introvert vs Extravert)

- Social Class

- Social Expectations

- Social Roles

- Social Status

- Spirituality

- Sporting Skills and Interests

- Subcultural Idenficiation

- Personal Values

Get a Pdf of this article for class

Enjoy subscriber-only access to this article’s pdf

Real Life Personal Identity Analysis: Queen Elizabeth II

As the longest-serving ruler of England, Queen Elizabeth II will be a character remembered through the history books for many hundreds of years.

There are some interesting aspects of the Queen’s personal identity that make her a good case study. No one is quite like her.

She has some features that overlap with many other people. But she has some that are remarkably unique.

Let’s start with the more common identity features of the Queen

Personal Identity of the Queen

The Queen was assigned female at birth and accepted this as her gender identity throughout her life.

Her gender affected her life profoundly. For one thing, she would only have been able to become the Queen because she did not have any brothers who, at the time, would have overriden her claim to the throne because they were male.

In smaller ways, her gender affected her personal identity. For example, the way she would dress was normal only for women and not men (she wore many famous flowing dresses, for example).

2. Race/Ethnicity

The Queen is of a white Western European ethnicity. She has Germanic, English, Scottish, Hungarian, French, and Irish blood.

Clearly, the Queen was of privileged social status. Her family’s race would, in history, have been a prerequisite for them ruling England. Today, the white European British ethnicity remains an ethnicity of privilege in Europe.

3. Social Class

The Queen was at the very tip of the social class hierarchy. Born into wealth and high social status, she was seen as being of the upper class.

This influenced her personal identity from a very young age. The Queen’s posh accent, for example, developed from her cultural surroundings. Similarly, she never experienced financial hardship or the need to go out and seek a trade (although, interestingly, she did serve as a mechanic during the 1940s).

4. Marital Status

The Queen was married to Prince Phillip. Her marital status would likely have been central to her sense of self.

The Queen would not only have seen herself as a wife, but also a mother. Like most married parents, these two identity features were probably at the core of her sense of self.

Most people’s status as a husband, wife, or parent, can affect how they think (always keeping their loved ones in their thoughts when they make decisions) and act (for example, many people insist they can’t quit their job because they have family who rely on them!).

5. Ascribed Status

Ascribed status refers to a social status that you were given at your time of birth. Of course, for Queen Elizabeth, she was ascribed her royal status by birthright.

In fact, the queen almost had to become the queen. She could have abdicated her right, like her uncle did, but this is highly frowned upon in Royal circles. Her uncle left Britain and moved to the United States to get away from his ascribed status!

6. Achieved Status

Achieved status refers to your personal accomplishments in life.

For the Queen, this includes being the longest ruling British monarch in history. She wasn’t born with this status, she achieved it through her life.

Similarly, the Queen might claim her ability to unite England, Wales, and Scotland under her for over 70 years as an accomplishment of sorts.

Normal people would often identify things like a university degree or their profession as their personal accomplishments.

7. Family Role

The Queen also has a very interesting family role which underpins her personal identity.

In Western Europe, women did not traditionally take the family role of decision maker and authority figure. But the Queen’s unique status as Queen meant that she became the matriarch of her family.

Famously, all family decisions had to be passed through her, and she even had the authority to decide which family members could (and couldn’t) use the royal title and get money from her personal trust fund.

Definition of Personal Identity

A personal identity is the collection of unique identifying factors that a person develops over time that make up who they are.

Your personal identity is unique to you because no one has the exact same mix of features , memories, habits, emotional dispositions, and knowledge that you have.

Personal identity is similar to social identity, but personal identities are about all of your unique features whereas your social identity usually only counts your sociological categorizations ( social identity examples include: gender, race, social class).

How we Develop a Personal Identity

Your personal identity begins to be formed even before you were born.

Everyone is born with a history: who their parents are, genetic factors, and socially ascribed status features that are assigned at birth (e.g. gender).

As we enter middle childhood , our sense of self emerges in ernest. We start learning about our personal tastes, preferences, and hobbies.

As children, we also get feedback from our surroundings (other children’s reactions to us, our parents disciplining us) which shape who we are as well. Some children meet these identity challenges and develop self-confidence and independence, while others may be scarred by their early rebukes and setbacks.

Into adolescence , we start to develop aspects of our identities like mindsets, ideologies, philosophies, and romantic relationships that will underpin our futures. Adolescents often explore different subcultural and countercultural identities to ‘try on’ ways of behaving.

The identity features that resonate with any individual may become a lifelong identity feature (e.g. ‘a lover of rap music’ or ‘a long-distance runner’).

In adulthood , our personal identities come to revolve around career and family status. We become concerned with creating a legacy and making a sustainable and happy life for ourselves and our loved ones.

Why is Personal Identity Important?

Developing a sense of who we are is essential for developing self-efficacy, morality, and happiness.

Self-efficacy refers to belief in yourself. People who grow up to be competent, optimistic, and self-reliant have high self-efficacy. These people can navigate challenges and obstacles they face in everyday life. It sets them up well for success, builds resilience, and prevents burnout or social withdrawal.

Our morality refers to our sense of right and wrong. When you know who you are and what your personal standards are, then you’re able to set boundaries about what you will and will not do. Morality comes in part from our family and culture, but it’s also developed through our own thought processes as we move through adolescence and adulthood.

Happiness will often come from having a clear sense of who we are, what we want out of life, and whether we have achieved it. People who don’t know who they are and don’t have purpose in life will often be unhappy. This is because they don’t have a clear moral core. By contrast, people with a clear sense of their own personal identity will often be able to find happiness by taking up pursuits that fulfil their sense of purpose.

There are countless factors that influence our personal identity. Above, I’ve outlined some of the most important elements that people might point to when trying to define what’s unique about themselves.

Developing a personal identity can make you confident and self-assured. When you know who you are and are comfortable with that, you can begin to develop happiness and contentment.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

2 thoughts on “65 Personal Identity Examples”

I struggle to understand Identity and how to change that what your not happy with. How do you actually change identity, obvs we can’t change race, gender, etc., but if you wanted to change beliefs, how you see yourself etc? how do you change it without an experience? I say that because some experiences changes our way of thinking, but how to change without an experience ?

It’s hard. I would probably start with reading books and listening to podcasts about mindset, exploring new hobbies, going out of your comfort zone – in other words, manufacturing the experiences that are required to create those identity changes.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Calculate for all schools

Your chance of acceptance, your chancing factors, extracurriculars, essays about personal identity.

Hi all! I'm thinking about writing an essay that focuses on my personal identity. What are some ways to make this type of essay engaging and interesting to colleges? Any examples I should check out for inspiration? Thanks in advance!

Hello! Writing an essay that focuses on your personal identity can be a powerful way to showcase your unique experiences, interests, and perspectives. To make this type of essay engaging and interesting to colleges, consider the following tips:

1. Be authentic and vulnerable: Share your true feelings, thoughts, and struggles as they pertain to your identity. By being open about your experiences, you create a deep connection with the reader.

2. Focus on a specific aspect: Instead of trying to cover every detail of your identity, choose one or two key facets that define you. Delving into particular experiences and emotions will allow you to demonstrate depth and create a more compelling narrative.

3. Use descriptive language and vivid imagery: Paint a picture for the reader by using descriptive words and vivid imagery. This will help them visualize and connect with your story on a deeper level.

4. Show rather than tell: Instead of simply stating your thoughts and feelings about your identity, use anecdotes and examples to illustrate your point. By showing the reader your experiences, you'll create a more compelling and engaging essay.

5. Incorporate growth and development: Demonstrate how your understanding of your identity has evolved over time, and how it has shaped you as a person. This could include personal challenges you've faced, accomplishments, or newfound insights.

6. Reflect on the impact: Discuss how your identity has influenced your decisions, interests, and relationships. This reflection will help demonstrate the importance of your identity and its role in your life.

For examples and inspiration, you can browse through essays shared by students who were admitted to top colleges. Just be mindful not to copy their ideas or writing styles. Instead, use these examples to inspire your own unique angle in exploring your personal identity.

Best of luck with your essay and application process!

About CollegeVine’s Expert FAQ

CollegeVine’s Q&A seeks to offer informed perspectives on commonly asked admissions questions. Every answer is refined and validated by our team of admissions experts to ensure it resonates with trusted knowledge in the field.

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- Home ›

- Reviews ›

First, Second, and Other Selves: Essays on Friendship and Personal Identity

Jennifer Whiting, First, Second, and Other Selves: Essays on Friendship and Personal Identity , Oxford University Press, 2016, 261pp., $74.00 (hbk), ISBN 9780199967919.

Reviewed by David O. Brink, University of California, San Diego

This is the first of three volumes of Jennifer Whiting's collected papers and focuses on issues about personal identity and friendship. The volume's eight essays are all previously published, but in disparate venues, so the volume allows the reader to see the cumulative force of ideas developed piecemeal and recurrent themes. Whiting herself identifies three such themes. First, she focuses on psychic contingenc y and variability , which is sometimes a symptom of pathology but often a reminder that familiar assumptions of moral psychology are neither universal nor necessary. Second, she explores Aristotle's conception of the friend as another self and its significance for our understanding of intrapersonal and interpersonal relations and concern. Her third theme emerges from the second and involves a non-egocentric perspective on self-love and love of others. She treats the interpersonal case as prior in explanation and justification to the intrapersonal case.

Her outside-in strategy contrasts with the inside-out strategy that goes with an egocentric assimilation of the interpersonal case to the intrapersonal case. This leads her to defend an ethocentric , or character-based, conception of both prudential concern and friendship. There are important kinds of historical influence and inspiration in these essays, including Whiting's exploration of Aristotle's conception of friendship, her discussion of Platonic love, and her discussion of Plato's conception of the soul in the Republic . However, most of the essays concentrate on systematic, rather than historical, issues and debates. Apparently, the other two volumes of essays will be more historical, focusing on the metaphysical and psychological basis of Aristotle's ethics.

These essays are long and densely argued, defying easy summary. But they are extremely rewarding and repay careful study. They display philosophical imagination and give expression to an independent voice. Whiting's essays are also deeply personal, reflecting ongoing conversations with her philosophical mentors, colleagues, and friends. Whiting is engaged in dialogue with Plato, Aristotle, Locke, Sydney Shoemaker, Derek Parfit, Annette Baier, and Terence Irwin, among others, and one comes away with a strong sense of her as a philosophical interlocutor . Her essays on personal identity and friendship are among the most important work on these topics in the last three decades. Her defense of a broadly psychological reductionist conception of personal identity is a worthy successor to the contributions of Shoemaker and Parfit, and her ethocentric conception of friendship and self-love is an important and original contribution to the literature on love and friendship. Anyone interested in these philosophical topics will profit from reading these essays together.

In what follows, I summarize the contributions of individual essays and then turn to raising some questions about her claims about personal identity and friendship.