- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Beyond 'Good' Vs. 'Bad' Touch: 4 Lessons To Help Prevent Child Sexual Abuse

Tennessee Watson

More than 58,000 children were sexually abused in the U.S. in 2017, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services .

Many states are trying to curb those numbers — 20 now require sexual abuse prevention education by law. In 2009, Vermont became one of the first.

K-12 schools in Vermont are required to provide sexual violence prevention to all students. Schools must also provide information to parents. Additionally, all schools and childcare facilities are required to train teachers and adult employees.

Vermont is a testing ground for states like Wyoming, which is one of nine other states that allow or recommend this type of education, but don't require it.

Jody Sanborn, the prevention specialist for the Wyoming Coalition Against Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault, wants all Wyoming communities to work to keep kids safe from sexual abuse. But she says Wyoming isn't there yet.

"Wyoming is at a stage of what we call denial or resistance that the issue even exists in the first place," Sanborn says.

Eventually, she'd like to see something in place to guarantee schools are teaching prevention statewide. But she knows Wyoming's strong culture of local control makes that hard.

In Vermont, it's up to local school boards to pick the curriculum they'd like to use.

California Lawmakers Consider How To Regulate Home Schools After Abuse Discovery

How Schools Can Reduce Sexual Violence

Linda Johnson, the executive director of Prevent Child Abuse Vermont , strongly encourages schools to adopt the evidence-based model that her organization has been using since the 1990s. It's a series of age-appropriate lessons designed to help protect little kids from sexual abuse.

That may sound like a scary topic, but this curriculum takes a positive approach by focusing on healthy relationships : How to pay attention to your feelings, knowing about your body and your boundaries, and, if something doesn't feel right, knowing you can ask for help.

Joy Kitchell, who runs a child advocacy center in Bennington, Vt., teaches the curriculum distributed by Johnson's organization. Kitchell worked as a teacher and a principal for years before turning her focus entirely to sexual abuse prevention.

She says parents feel more at ease knowing that their kids aren't explicitly talking about sex or sexual violence.

Still, she says, it's up to adults to know the signs and symptoms of abuse — and teach behaviors that could prevent it.

What can parents and teachers do to keep their kids safe? Kitchell and Johnson offer some key lessons geared toward sexual abuse prevention.

The lessons also address sexual abuse between kids. Johnson says talking about these things early might keep kids from doing harm as they get older.

Teach kids to pay attention to their feelings

Around 90 percent of child sexual abusers are someone the child knows, according to the Crimes Against Children Research Center.

Kitchell says that makes it even harder for kids to understand that something bad is happening.

"A person who is grooming a child to be their victim, they are going to do it in such a way that it's not going to be painful. It's going to be confusing," she says.

That's an important departure from teaching "good" versus "bad" touch.

"If a child is taught that it's good touch or bad touch, and it's not a bad touch but it's confusing, then they might not understand that it's OK to go to a trusted adult and figure that out," Kitchell says.

Let kids know they can talk to trusted grown-ups

Linda Johnson of Prevent Child Abuse Vermont says teaching children they can tell other grown-ups any time they're confused means they don't have to decide for themselves if the touch is good or bad.

And there's an important difference between teaching a kid they should tell versus teaching a kid they can tell, she says.

"We don't want to add guilt and sense of responsibility to children who have been victimized," she says.

Learning 'no' means no

One recurring theme in the curricula is the meaning of no. "That is the foundation of consent," Johnson says.

When one kid isn't willing to share with another kid, grown-ups often jump in to force them to share. But Johnson teaches adults to take a different approach. She says it's important to remind kids that hearing "no" is part of life.

"We can teach this to 2-year-olds, and then again at 3 and 4 and 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, until — there they are in that situation in the car and one wants to and one doesn't want to," Johnson says. "And they have to be able to accept 'no' for an answer."

Start the conversation at home

When working with preschoolers and younger elementary schoolers, Kitchell uses picture books to help start conversations about boundaries and consent.

She also uses anatomically correct dolls to help kids learn the names of their body parts. She says these are things parents can also do at home.

Among the many books she uses are:

How Are You Peeling? by Saxton Freymann and Joost Elffers

Hands Off, Harry! by Rosemary Wells

Uncle Willy's Tickles: A Child's Right to Say No by Marcie Aboff

All By Myself by Mercer Mayer

The New Baby by Mercer Mayer

The Bare Naked Book by Kathy Stinson and Heather Collins

How Can I Protect My Child From Sexual Assault?

Para leer en español, haga clic aquí .

Sexual abuse can happen to children of any race, socioeconomic group, religion or culture. There is no foolproof way to protect children from sexual abuse, but there are steps you can take to reduce this risk. If something happens to your child, remember that the perpetrator is to blame—not you and especially not the child. Below you’ll find some precautions you can take to help protect the children in your life.

If your child is in immediate danger, don’t hesitate to call 911. If you aren’t sure of the situation but you suspect the child is being harmed , you can take steps to gauge the situation and put an end to the abuse.

Be involved in the child’s life.

Being actively involved in a child’s life can make warning signs of child sexual abuse more obvious and help the child feel more comfortable coming to you if something isn’t right. If you see or hear something that causes concern, you can take action to protect your child.

- Show interest in their day-to-day lives . Ask them what they did during the day and who they did it with. Who did they sit with at lunchtime? What games did they play after school? Did they enjoy themselves?

- Get to know the people in your child’s life . Know who your child is spending time with, including other children and adults. Ask your child about the kids they go to school with, the parents of their friends, and other people they may encounter, such as teammates or coaches. Talk about these people openly and ask questions so that your child can feel comfortable doing the same.

- Choose caregivers carefully . Whether it’s a babysitter, a new school, or an afterschool activity, be diligent about screening caregivers for your child.

- Talk about the media . Incidents of sexual violence are frequently covered by the news and portrayed in television shows. Ask your child questions about this coverage to start a conversation. Questions like, “Have you ever heard of this happening before?” or “What would you do if you were in this situation?” can signal to your child that these are important issues that they can talk about with you. Learn more about talking to your kids about sexual assault.

- Know the warning signs . Become familiar with the warning signs of child sexual abuse , and notice any changes with your child, no matter how small. Whether it’s happening to your child or a child you know, you have the potential to make a big difference in that person’s life by stepping in .

Encourage children to speak up.

When someone knows that their voice will be heard and taken seriously, it gives them the courage to speak up when something isn’t right. You can start having these conversations with your children as soon as they begin using words to talk about feelings or emotions. Don’t worry if you haven't started conversations around these topics with your child—it is never too late.

- Teach your child about boundaries . Let your child know that no one has the right to touch them or make them feel uncomfortable — this includes hugs from grandparents or even tickling from mom or dad. It is important to let your child know that their body is their own. Just as importantly, remind your child that they do not have the right to touch someone else if that person does not want to be touched.

- Teach your child how to talk about their bodies . From an early age, teach your child the names of their body parts. Teaching a child these words gives them the ability to come to you when something is wrong. Learn more about talking to children about sexual assault .

- Be available . Set time aside to spend with your child where they have your undivided attention. Let your child know that they can come to you if they have questions or if someone is talking to them in a way that makes them feel uncomfortable. If they do come to you with questions or concerns, follow through on your word and make the time to talk.

- Let them know they won’t get in trouble . Many perpetrators use secret-keeping or threats as a way of keeping children quiet about abuse. Remind your child frequently that they will not get in trouble for talking to you, no matter what they need to say. When they do come to you, follow through on this promise and avoid punishing them for speaking up.

- Give them the chance to raise new topics . Sometimes asking direct questions like, “Did you have fun?” and “Was it a good time?” won’t give you the answers you need. Give your child a chance to bring up their own concerns or ideas by asking open-ended questions like “Is there anything else you wanted to talk about?”

To speak with someone who is trained to help, call the National Sexual Assault Hotline at 800.656.HOPE (4673) or chat online at online.rainn.org .

Related Content

Talking to your kids about sexual assault.

Conversations about sexual assault can be a part of the safety conversations you’re already having, like knowing when to speak up, how to take care of friends, and listening to your gut.

Evaluating Caregivers

There are steps you can take to evaluate caregivers, such as babysitters or nursing homes, to reduce the risk of something happening to your loved one.

Child Sexual Abuse

When a perpetrator intentionally harms a minor physically, psychologically, sexually, or by acts of neglect, the crime is known as child abuse.

What are the warning signs for child sexual abuse?

Every 68 seconds, another american is sexually assaulted., 91¢ of every $1 goes to helping survivors and preventing sexual violence..

- High contrast

- Press Centre

Search UNICEF

Sexual violence against children, sexual violence knows no boundaries. it occurs in every country, across all parts of society..

- Violence against children

- Sexual violence

Every year, millions of girls and boys around the world face sexual abuse and exploitation. Sexual violence occurs everywhere – in every country and across all segments of society. A child may be subjected to sexual abuse or exploitation at home, at school or in their community. The widespread use of digital technologies can also put children at risk.

Most often, abuse occurs at the hands of someone a child knows and trusts.

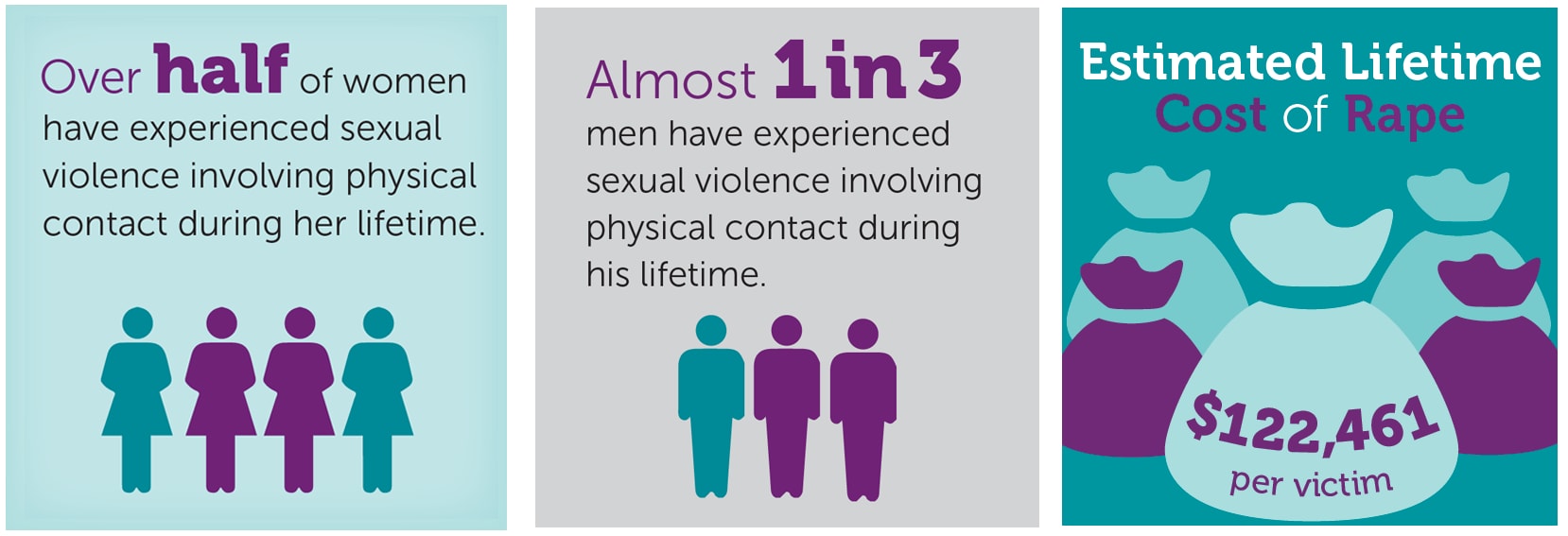

At least 120 million girls under the age of 20 – about 1 in 10 – have been forced to engage in sex or perform other sexual acts, although the actual figure is likely much higher. Roughly 90 per cent of adolescent girls who report forced sex say that their first perpetrator was someone they knew, usually a boyfriend or a husband.

But many victims of sexual violence, including millions of boys, never tell anyone.

About 1 in 10 girls under the age of 20 have been forced to engage in sex or perform other sexual acts.

Although sexual violence occurs everywhere, risks surge in emergency contexts. During armed conflict, natural disasters and other humanitarian emergencies , women and children are especially vulnerable to sexual violence – including conflict-related sexual violence, intimate partner violence and trafficking for sexual exploitation – as well as other forms of gender-based violence .

Sexual violence results in severe physical, psychological and social harm. Victims experience an increased risk of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, pain, illness, unwanted pregnancy, social isolation and psychological trauma. Some victims may resort to risky behaviours like substance abuse to cope with trauma. And as child victims reach adulthood, sexual violence can reduce their ability to care for themselves and others.

While sexual violence is fundamentally a crime of power, it is increasingly driven by economic motives. The internet has opened a rapidly growing global market for the production, distribution and consumption of child sexual abuse materials, such as photographs and videos. When online , children may be susceptible to sexual coercion and in-contact sexual abuse by offenders who attempt to extort them for content and financial gain.

The harmful norms that perpetuate sexual violence take a heavy toll on families and communities too. Most children who face sexual abuse experience other kinds of violence. And as abuse and exploitation become entrenched, progress towards development and peace can stall – with consequences for entire societies.

UNICEF’s response

UNICEF plays a key role in preventing and responding to sexual violence worldwide – both in emergency and non-emergency contexts – through programmes, partnerships and advocacy.

Globally, we build advocacy tools and develop technical guidance for violence prevention and response, helping to ensure services are appropriate and sensitive to the needs of survivors. We work closely with partners on a variety of global initiatives, including the Global Partnership to End Violence against Children , Together for Girls and the WePROTECT Global Alliance to End Child Sexual Exploitation Online .

At the national level, we work with governments to develop and strengthen laws and policies, and to increase access to justice, health, education and social services that help child and adolescent survivors recover. We also invest in national prevention programmes to change social norms that condone sexual violence and perpetuate a culture of silence.

Throughout all we do, we focus on supporting children and parents. We work directly with children to build their knowledge on how and where to seek help and protection; and with parents, teachers and adults to identity signs of abuse and make sure children receive ongoing care.

More from UNICEF

Stories of hope, courage and change

Read stories about the work of UNICEF and the Spotlight Initiative to end violence against women and girls across Latin America and Africa

DR Congo: Children killed, injured, abducted, and face sexual violence in conflict at record levels for third consecutive year – UNICEF

UNICEF calls for urgent action to respond to alarming levels of increasing sexual violence against girls and women in eastern DRC

On world poetry day, hundreds of children affected by conflict and war share poems for peace, action to end child sexual abuse and exploitation: a review of the evidence 2020.

This evidence review documents the evidence on effective interventions and strategies to prevent and respond to child sexual abuse and exploitation.

Action to End Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation

The Action to End Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation proposed a framework of action to prevent and respond to child sexual abuse and exploitation.

UNICEF Humanitarian Practice: COVID-19 Technical Guidance

Terminology guidelines for the protection of children from sexual exploitation and abuse, promising programmes to prevent and respond to child sexual abuse and exploitation , preventing and responding to child sexual abuse and exploitation: evidence review, government, civil society and private sector responses to the prevention of sexual exploitation of children in travel and tourism , protecting children from online sexual exploitation: a guide to action for religious leaders and communities, unicef and leap: a new reality – child helplines report on online child sexual exploitation and abuse, optional protocol to the convention on the rights of the child on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography, implementation handbook on the optional protocol on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography, child safety online: global challenges and strategies, world congress iii against sexual exploitation of children and adolescents, council of europe convention on the protection of children from sexual exploitation and sexual abuse, code of conduct for the protection of children from sexual exploitation in travel and tourism, ecpat international, together for girls initiative to end sexual violence, un special representative of the secretary-general on violence against children, online course: action to end child sexual exploitation and abuse, legislating for the digital age: global guide on improving legislative frameworks to protect children from online sexual exploitation and abuse framing the future: how the model national response framework is supporting national efforts to end child sexual exploitation and abuse online.

Last updated 23 June 2022

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

A systematic review of primary prevention strategies for sexual violence perpetration ☆

Associated data.

This systematic review examined 140 outcome evaluations of primary prevention strategies for sexual violence perpetration. The review had two goals: 1) to describe and assess the breadth, quality, and evolution of evaluation research in this area; and 2) to summarize the best available research evidence for sexual violence prevention practitioners by categorizing programs with regard to their evidence of effectiveness on sexual violence behavioral outcomes in a rigorous evaluation. The majority of sexual violence prevention strategies in the evaluation literature are brief, psycho-educational programs focused on increasing knowledge or changing attitudes, none of which have shown evidence of effectiveness on sexually violent behavior using a rigorous evaluation design. Based on evaluation studies included in the current review, only three primary prevention strategies have demonstrated significant effects on sexually violent behavior in a rigorous outcome evaluation: Safe Dates ( Foshee et al., 2004 ); Shifting Boundaries (building-level intervention only, Taylor, Stein, Woods, Mumford, & Forum, 2011 ); and funding associated with the 1994 U.S. Violence Against Women Act (VAWA; Boba & Lilley, 2009 ). The dearth of effective prevention strategies available to date may reflect a lack of fit between the design of many of the existing programs and the principles of effective prevention identified by Nation et al. (2003) .

1. Introduction

Sexual violence 2 is a significant public health problem affecting millions of individuals in the United States and around the world ( Black et al., 2011 ; Krug, Dahlberg, Mercy, Zwi, & Lozano, 2002 ; World Health Organization/London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 2010 ). Efforts to prevent sexual violence before it occurs (i.e., primary prevention) are increasingly recognized as a critical and necessary complement to strategies aimed at preventing re-victimization or recidivism and ameliorating the adverse effects of sexual violence on victims (e.g., Black et al., 2011 ; Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2004 ; DeGue, Simon, et al., 2012 ; Krug et al., 2002 ). Successful primary prevention efforts, however, require an understanding of what works to prevent sexual violence and implementing effective strategies. Currently, there are no comprehensive, systematic reviews of evaluation research on primary prevention strategies for sexual violence perpetration. Such a review is needed to inform prevention practice and guide additional research to build the evidence base. To address this gap, the current paper provides a systematic review and summary of the existing literature and identifies gaps and future directions for research and practice in the prevention of sexual violence perpetration.

Primary prevention strategies, as defined here, include universal interventions directed at the general population as well as selected interventions aimed at those who may be at increased risk for sexual violence perpetration ( Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2004 ). To capture the breadth of possible sexual violence prevention efforts, we defined primary prevention strategies to include any primary prevention efforts, including policies and programs (similar to Saul, Wandersman, et al., 2008 ). Consistent with the public health approach to sexual violence prevention ( Cox, Ortega, Cook-Craig, & Conway, 2010 ; DeGue, Simon, et al., 2012 ; McMahon, 2000 ), strategies to prevent violence perpetration, rather than victimization, are the focus of this review. Although risk reduction approaches that aim to prevent victimization can be important and valuable pieces of the prevention puzzle 3 , a decrease in the number of actual and potential perpetrators in the population is necessary to achieve measurable reductions in the prevalence of sexual violence ( DeGue, Simon, et al., 2012 ).

1.1. Goals of the current review

1.1.1. describing the state of the field in sexual violence prevention.

The first goal of this review is to describe the broad field of sexual violence prevention research and identify patterns of results associated with evaluation methodology or programmatic elements. Although a number of qualitative reviews, meta-analyses, and one meta-review (e.g., Anderson & Whiston, 2005 ; Breitenbecher, 2000 ; Carmody & Carrington, 2000 ; Vladutiu, Martin, & Macy, 2011 ) have been conducted over the past two decades, no reviews examine methodological and programmatic elements and sexual violence outcomes across the broad spectrum of sexual violence primary prevention efforts. Several existing reviews focus solely on describing approaches being implemented in the field and the use of underlying theory ( Carmody & Carrington, 2000 ; Fischhoff, Furby, & Morgan, 1987 ; Paul & Gray, 2011 ). Two non-systematic reviews identified methodological and programmatic issues associated with sexual violence prevention efforts with college students ( Breitenbecher, 2000 ; Schewe & O’Donohue, 1993 ) and called attention to the need to measure behavioral outcomes (in addition to changes in attitudes and behavioral intentions) to demonstrate an impact on sexual violence. These reviews also pointed out that the small statistically significant effects reported on the, primarily attitudinal, measures in existing studies may not be truly meaningful (i.e., clinically significant). These existing reviews focused solely on college-based strategies, limiting the generalizability of these findings to community-based and younger audiences.

Three meta-analyses examined the effectiveness of educational prevention programming with college students ( Anderson & Whiston, 2005 ; Brecklin & Forde, 2001 ; Flores & Hartlaub, 1998 ), but two of these focused only on attitudinal outcomes (i.e., Brecklin & Forde, 2001 ; Flores & Hartlaub, 1998 ). All three reported small to moderate mean effects on attitudes ranging from 0.06 to 0.35 (e.g., rape myth acceptance) and noted that the magnitude of effects decreased as the interval between strategy implementation and data collection increased. In addition, Anderson and Whiston (2005) reported a moderate mean effect size for knowledge (0.57), but reported small mean effect sizes for behavioral intentions (0.14), incidence of sexual violence (0.12), and attitudes considered more distal to sexual violence (0.10; e.g., adversarial sexual beliefs, hostile attitudes toward women), suggesting that the changes may have little clinical significance. Mean effect sizes for rape empathy and indicators of greater rape awareness (e.g., willingness to volunteer at rape crisis centers) were not significantly different from zero. The results from these meta-analyses suggest that knowledge and attitudes are assessed most frequently in prevention programming with college students, with attitudinal measures showing the largest effect sizes in evaluations of those programs. Although attitudes and behaviors are related, attitudes typically account for a relatively small proportion of the variance in behavior (e.g., Glasman & Albarracín, 2006 ; Kraus, 1995 ), suggesting that achieving attitude change may not be enough to impact sexual violence behaviors.

The one meta-review ( Vladutiu et al., 2011 ) also focused on reviews of college-based programs. Vladutiu and colleagues noted that reviews often made inconsistent recommendations, primarily due to differences in program context and content and the outcomes examined in the studies. For example, Vladutiu et al. (2011) concluded that longer programs were generally associated with greater effectiveness, but some shorter programs were able to document change when rape myth acceptance was the only outcome of interest. Single-gender audience approaches were generally considered more effective, but primarily when the program focused on attitudes, empathy, and knowledge outcomes related to sexual violence. The meta-review also identified a wide range of content and delivery components that were associated with changes on different outcomes. Finally, Vladutiu et al. (2011) noted that of the reviews included in their meta-review, only one had been published in the last decade (i.e., Anderson & Whiston, 2005 ). As indicated previously, there are no comprehensive reviews of the sexual violence prevention evaluation literature, and the only systematic reviews have dealt solely with college-based strategies. Relatively few patterns have been identified or recommendations made with respect to improving primary prevention of sexual violence or the rigor of evaluations conducted in the field. An updated, systematic, and comprehensive review of the literature on sexual violence primary prevention programs is warranted.

1.1.2. Summarizing “what works” in sexual violence prevention

The second goal of this review is to identify and summarize the best available evidence on specific sexual violence primary prevention strategies. Prevention practitioners are increasingly being asked to select and implement evidence-based practices and to devote resources toward strategies most likely to have an impact on health outcomes, but guidance and information on navigating this process are lacking ( Saul, Duffy, et al., 2008 ; Tseng, 2012 ). In particular, we wish to identify effective strategies for preventing sexual violence perpetration behaviors, as that is the ultimate goal of sexual violence prevention efforts. Although targeting risk and protective factors such as attitudes and knowledge are common prevention approaches, the most critical objective is to prevent sexual violence perpetration behaviors and their adverse effects ( Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2004 ; World Health Organization/London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 2010 ). Evidence regarding change in sexual violence perpetration behavior, however, is generally absent from the literature ( Schewe & O’Donohue, 1993 ; Vladutiu et al., 2011 ; World Health Organization/London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 2010 ). By summarizing the evidence on strategies that have been rigorously evaluated for sexually violent behavior, we can identify and categorize programs that currently appear to have evidence of effectiveness, those that are ineffective, and others that are potentially harmful strategies to assist practitioner efforts at better selecting and implementing sexual violence prevention strategies.

2.1. Search strategy

To identify studies meeting selection criteria for this review, we first conducted searches of the following online databases between May and August of 2009 and repeated these searches in March and April of 2010 and May of 2012: PsycNet, PsycExtra, PubMed, ERIC, Sociological Abstracts, MEDLINE, Web of Knowledge, Dissertation Abstracts International, and GoogleScholar. Search terms included combinations of the following: (intervention, prevent*, program, effectiveness, efficacy or evaluation) and (perpetration, rape, rapist, sex*, coercion, violence, aggression, assault, offender, or abuse). Second, manual reviews of issues from relevant journals (i.e., Aggression and Violent Behavior , Journal of Adolescent Health , Journal of Interpersonal Violence , Journal of Women’s Health , Prevention Science , Psychology of Violence , Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research and Treatment , Trauma , Violence , & Abuse , Violence Against Women , Violence & Victims ) published between January 2008 and May 2012 were also conducted to identify recent work in this area that may not have been cataloged yet in searchable databases. Third, to identify unpublished evaluation reports, solicitations were sent to relevant email lists and e-newsletters, including Prevent Connect, VAWnet, and the Sexual Violence Research Initiative. Fourth, for each article or report identified, we scanned the reference list to identify and retrieve additional reports that might meet inclusion criteria. During each of these iterative search steps, we were over-inclusive to ensure that all abstracts with the potential for inclusion were identified. The initial searches identified more than 10,600 reports, from which 330 were retained for full-text retrieval because they appeared to describe an outcome evaluation of a sexual violence prevention strategy.

2.2. Study selection criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they examined the effectiveness of primary prevention strategies for sexual violence perpetration and were published in print or online between January 1985 4 and May 2012. Journal articles, book chapters, and reports from government agencies or other institutions were included. Efforts were made to gather unpublished manuscripts, conference presentations, theses, and dissertations (see above). Because the focus on this review is to summarize the evidence base for the primary prevention of sexual violence perpetration, this review did not include studies that exclusively examined secondary and tertiary prevention approaches (e.g., treatment or recidivism prevention), strategies targeting victimization prevention (i.e., risk reduction), or etiological research. In order to avoid double-counting studies, existing reviews and meta-analyses of interventions for sexual violence prevention were excluded.

Only studies that compared one intervention condition to a no-treatment or waitlist control group (i.e., experimental and quasi-experimental designs) or that utilized a single-group pre–post design were included in this review, as the goal was to ascertain changes or differences in the outcomes following exposure to a specific treatment program. Thus, we excluded studies in which data from two different intervention groups were combined and compared to a control group as it was not possible to determine which intervention was responsible for any observed changes on the outcome measures. In addition, we excluded studies in which the intervention and the comparison conditions received different sexual violence prevention programs, because these studies examine the relative benefits of one program compared to another program as opposed to an individual program’s overall effectiveness relative to no intervention. Similarly, studies in which the comparison condition included a combined sample of control participants and participants who received a different sexual violence preventative intervention were also excluded. Because our focus was to examine the effectiveness of strategies to prevent sexual violence, studies that did not measure outcomes relevant to sexual violence perpetration were excluded (see below for a description of the outcomes included).

Of the 330 full-text reports retrieved, 226 reports were excluded. Reports were excluded because they did not describe an outcome evaluation study (45%; n = 101; e.g., review or meta-analysis, program description, theoretical paper, etiological research), did not measure sexual violence-related outcomes (11%; n = 25), evaluated a victimization prevention strategy only (10%; n = 23), did not evaluate a primary prevention strategy (8%; n = 18; e.g., sex offender treatment or recidivism prevention), did not utilize a research design with a comparison group or pre–post measurement (7.5%; n = 17), or met other exclusion criteria (8.1%; n = 27; e.g., non-English language). In addition, we identified several reports that described outcomes from the same study (e.g., a dissertation and a peer-reviewed journal article). In these cases, the peer-reviewed journal article was coded as the primary source and other reports were excluded as a duplicate report (3%; n = 7). In some cases, the excluded reports (e.g., dissertations) were used to provide supplemental information about the sexual violence prevention program or the evaluation design during the coding process. Numerous attempts were made to retrieve all reports identified in the initial searches, including contacting the first author directly and utilizing inter-library loan resources to obtain print copies. However, another eight reports (3.5%) identified through database searches could not be retrieved and were excluded as unavailable. These missing reports were nearly all dissertations and most were published more than 15 years ago; thus, this review may underrepresent these older dissertations.

2.3. Data extraction

2.3.1. coding process.

The review team developed a structured coding sheet 5 to extract, quantify, and summarize information from studies. A detailed coding manual was developed to ensure consistency across coders. Before coding began, the review team completed several reviews in order to refine the coding sheet and manual and to increase reliability. The review team consisted of six doctoral-level researchers with expertise in violence prevention. Two reviewers independently coded each of the 104 reports meeting inclusion criteria for this study between November of 2009 and December of 2012. Coding dyads were randomized such that no two coders coded more than one-sixth of the studies together. After each study was coded independently by two reviewers, coding sheets were compared and discrepancies were discussed. Initial agreement by independent coders was acceptable, with reviewers initially agreeing on 75.6% of codes. The coding dyad discussed any items on which there was disagreement until consensus was reached on the best possible response for each item, and the final consensus code was used in analyses.

2.3.2. Study variables and outcomes coded

The variables coded included the report type, study design, sample, nature of the prevention strategy (i.e., setting, delivery, dose, stated program goals, program content), and relevant program outcomes. Study outcomes relevant to sexual violence were coded within eight key categories: sexually violent behavior 6 including rates or reports of perpetration or victimization; rape proclivity or self-reported likelihood of future sexual perpetration; attitudes about gender roles, sexual violence, sexual behavior, or bystander intervention; knowledge about sexual violence rates, definitions, and laws; bystanding behavior related to sexual violence, such as intervening in a risky situation or speaking up about violence; bystanding intentions or self-reported likelihood of intervening in a hypothetical scenario; relevant skills related to communication, relationships, or bystanding behavior, and affect / arousal to violence including victim-related empathy and sexual attraction to violence.

The patterns of intervention effects within each study were summarized within and across outcome categories. Intervention effects were considered positive if significant effects were reported on all relevant outcomes in the hypothesized direction at all measurement time points. Study effects were categorized as null if all findings on relevant outcomes were non-significant. Effects were mixed if findings were a combination of positive and null. Studies that had at least one significant finding on any relevant outcome in a negative direction, suggesting potentially harmful effects of the intervention, were categorized as having negative effects. Given the diversity of study designs, outcome measures, and follow-up periods examined, it was necessary to collapse findings from multiple measures and measurement periods within each study to characterize the overall patterns of effectiveness. For example, findings from multiple attitudinal measures relevant to sexual violence were collapsed into a composite “attitudes” category. For some analyses, these findings were further collapsed across outcome types (e.g., attitudes, knowledge) to obtain a summary of the overall effects. Similarly, intervention effects observed at different time points (i.e., post-test, follow-up) were combined into one code to represent the overall pattern of outcomes for that study.

2.3.3. Study sample

Of the 104 reports coded, 73 described a single study in which one prevention strategy was evaluated using a comparison group or pre–post design. The remaining 31 reports described findings from more than one evaluation study. The majority of these reports ( n = 25) compared two or more prevention strategies to a single control group, resulting in non-independent data across the various studies. Four reports described two or more separate studies in which samples were distinct and data were independent. Two reports included one study with independent data and two with non-independent data in the same report. To examine outcome data for each separate preventative program or strategy evaluated, we coded information about the study design, program characteristics and content, and outcome data for each of these studies separately. This approach is consistent with the process for systematic reviews recommended by the Task Force on Community Preventive Services ( Briss et al., 2000 ). Thus, the review team identified and coded 140 separate evaluation studies from the 104 reports meeting inclusion criteria. References for all studies included in this review are available in an online supplemental archive (see supplemental materials ); studies mentioned in the text are also referenced below.

2.4. Criteria for defining rigorous evaluation designs

Studies were classified as having either a rigorous or non-rigorous evaluation design. Rigorous evaluation designs included experimental studies with random assignment to an intervention or control condition (e.g., randomized controlled trial [RCT], cluster RCT) or rigorous quasi-experimental designs, such as interrupted time series or regression-discontinuity, for strategies where random assignment is not possible due to implementation restrictions (e.g., evaluation of policy). Other quasi-experimental designs (e.g., comparison groups without randomization to condition, including matched groups) and pre–post designs were considered non - rigorous evaluation designs , for the purposes of examining effectiveness in this review, consistent with standards of prevention science and evaluation research (e.g., Eccles, Grimshaw, Campbell, & Ramsay, 2003 ; Flay et al., 2005 ; Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002 ).

In addition to design considerations, studies meeting criteria for a rigorous evaluation design were required to have at least one follow - up assessment beyond an immediate post-test assessment. Prior research has established the presence of a rebound effect on attitudinal and knowledge outcomes for sexual violence prevention programs wherein effects are seen immediately after the program but are not evident at longer-term follow-up ( Anderson & Whiston, 2005 ; Brecklin & Forde, 2001 ; Carmody & Carrington, 2000 ). In addition, studies without a follow-up assessment often conducted the pre-test and the post-test measurement and the intervention all within the same session, increasing the potential influence of demand characteristics and test–retest effects. Thus, studies that did not include at least one follow-up measurement beyond immediate post-test, regardless of the research design, were also considered to be non-rigorous.

2.5. Criteria for evaluating evidence of effectiveness for preventing sexual violence

To identify prevention strategies with rigorous evidence of effectiveness, we developed criteria to classify specific interventions based on the strength of evidence of effectiveness for preventing sexually violent behavior. These criteria, illustrated in Fig. 1 , emphasize sexual violence behavioral outcomes and rigorous experimental research designs that permit inferences about causality. Based on these criteria, interventions were placed into one of five categories: Effective for Sexual Violence Behavioral Outcomes includes those interventions with evidence of any positive impact on sexual violence victimization or perpetration in at least one rigorous evaluation. Interventions categorized as Not Effective for Sexual Violence Behavioral Outcomes were evaluated on sexual violence outcomes using a rigorous evaluation design and had consistently null effects on those measures. Interventions categorized as Potentially Harmful for Sexual Violence Behavioral Outcomes include those with at least one negative effect on sexually violent behavior in a rigorous evaluation. Interventions categorized as More Research Needed included those with evidence of positive effects on sexual violence behavior in a non-rigorous evaluation or positive effects on sexual violence risk factors or related outcomes in a rigorous evaluation. Interventions were considered to have Insufficient Evidence if they were not published in a peer-reviewed journal or formal government report, if they measured outcomes at immediate post-test only without a longer follow-up period, if they found null effects on sexual violence behavioral outcomes using a non-rigorous design; and/or if they only examined risk factors or other related outcomes using a non-rigorous design (regardless of the type of effect).

Decision tree for evaluating evidence of effectiveness on sexual violence behavioral outcomes in rigorous evaluation.

We attempted to identify and combine findings from multiple studies or reports examining the same intervention based on the program name or description and used outcomes from the most rigorous evaluation(s) available to categorize the program’s effects. In some cases, researchers may have evaluated modified versions of the same program over time; findings from these evaluations were considered together if the program name did not change and there were no indications that modifications to the structure or content of the program model over time substantially altered the core content or strategy.

3.1. Study and intervention characteristics

Evaluation of sexual violence perpetration prevention programs peaked in the late 1990s and again in 2010 and 2011 (see Fig. 2 ). Table 1 describes characteristics of the 140 studies and interventions, including the research design, study population, intervention length, setting, participant and presenter sex, and mode of delivery. Notably, almost two-thirds ( n = 84; 60%) of the included studies examined one-session interventions with college populations; these programs had an average length of 68 min. The majority of studies utilizing pre–post designs measured outcomes at immediate post-test only ( n = 13, 56.5%). Studies with quasi-experimental designs measured outcomes most often at post-test ( n = 12, 34.3%) or with a follow-up period of one month or less ( n = 10, 28.6%). In contrast, evaluations using experimental designs had the lowest proportion of studies with post-test only outcomes ( n = 19, 23.2%) and the highest proportion with follow-ups at 5 months or longer ( n = 17, 20.7%).

Number of studies meeting inclusion criteria by publication year (Jan 1985–May 2012).

Study and intervention characteristics.

To examine changes in evaluation methodology over time, we compared studies published in 1999 or earlier ( n = 73; 52.1%) to those published in 2000 or later ( n = 67; 47.9%). Before 2000, 63% ( n = 46) of published studies were RCTs, 30.1% ( n = 22) used quasi-experimental designs, and 6.8% ( n = 5) used pre–post designs; 28.8% ( n = 21) assessed outcomes at immediate post-test only and only 6.8% ( n = 5) followed participants for 5 months or longer. Since 2000, 53.7% ( n = 36) of published studies were RCTs, 19.4% ( n = 13) were quasi-experimental, and 26.9% ( n = 18) were pre–post designs; 34.3% ( n = 23) of these studies measured outcomes at immediate post-test only, but another 26.9% ( n = 18) of studies assessed outcomes after at least 5 months.

3.2. Intervention effects by study characteristics and outcome type

Table 2 summarizes patterns of intervention effects by study characteristic and outcome types. Studies with mixed effects across outcome types and follow-up periods were most common (41.4%; n = 58). More than one-quarter of studies (27.9; n = 39) reported only positive effects and another 21.4% ( n = 30) reported only null findings. Nine studies (6.4%) had at least one negative finding suggesting that the intervention was associated with increased reporting of sexually violent behavior ( Potter & Moynihan, 2011 ; Stephens & George, 2009 ), rape proclivity ( Duggan, 1998 ; Hillenbrand-Gunn, Heppner, Mauch, & Park, 2010 ), or attitudes toward sexual violence ( Echols, 1998 ; McLeod, 1997 ; Murphy, 1997 ). Peer-reviewed studies and government reports tended to have positive or mixed findings more often than dissertations and unpublished manuscripts. Examination of outcomes by study design suggested that evaluations employing more rigorous methodologies (i.e., experimental or quasi-experimental designs with comparison groups) were less likely to identify consistently positive effects than studies using a pre–post design. Similarly, studies that examined outcomes at immediate post-test only were more likely to identify positive effects than studies with a longer follow-up period.

Patterns of intervention effects by study characteristics and outcome type.

Note . Of the 140 studies reviewed, 136 conducted sufficient outcome analyses to determine the effects of the intervention on relevant measures; the remaining four studies from three reports ( Feltey, Ainslie, & Geib, 1991 ; Heppner, Humphrey, Hillenbrand-Gunn, & DeBord, 1995 ; Wright, 2000 ) are not included in these analyses.

Looking at the pattern of intervention effects by outcome type, results suggest that null effects were more common and positive effects less common on sexually violent behavior and rape proclivity outcomes than on other outcome types. Specifically, about half of all studies measuring sexually violent behavior or rape proclivity found only null effects (47.6%; n = 10); very few studies (4.8%; n = 4) reported only significant, positive effects on these main outcomes of interest. In contrast, the majority of studies measuring knowledge, bystanding behavior or intentions or skills found consistently significant positive effects on these outcomes. No clear pattern was evident for studies assessing attitudinal or affective/arousal outcomes.

To examine the potential impact of intervention length, we estimated the average intervention exposure (i.e., sessions × length) for studies with positive, mixed, negative, and null effects. Findings indicate that interventions with consistently positive effects were about 2 to 3 times longer, with an average length of 6 h ( SD = 11.4), than interventions with mixed ( M = 3.2 h; SD = 6.6), negative ( M = 2.2 h; SD = .9), or null ( M = 2.8 h; SD = 4.3) effects.

3.3. Evidence of effectiveness for preventing sexual violence perpetration

As shown in Table 3 , only three interventions (based on 3 studies; 2.1%) were categorized as effective for sexual violence behavioral outcomes: Safe Dates (e.g., Foshee et al., 2004 , 2005 ), Shifting Boundaries building-level intervention ( Taylor, Stein, Mumford, & Woods, 2013 ; Taylor et al., 2011 ), and funding associated with the 1994 U.S. Violence Against Women Act ( Boba & Lilley, 2009 ). Five interventions (based on 11 studies; 6.4%) were found to be not effective for sexual violence behavioral outcomes and three interventions (based on 2 studies; 2.1%) reported evidence suggesting that they were potentially harmful. Another ten interventions (based on 17 studies; 12.1%) were categorized as needing more research in order to understand their effects. Findings within each of these categories are discussed below. The majority of studies reviewed ( n = 108; 77.1%) provided insufficient evidence to adequately evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention for preventing sexual violence; these studies were unpublished manuscripts or dissertations which had not been subjected to independent peer review ( n = 53; 38%), measured outcomes at immediate post-test only ( n = 57; 41%), and/or examined only risk factors or related outcomes for sexual violence using a non-rigorous design ( n = 71; 51%). Interventions with insufficient evidence are not included in Table 3 due to the large number of studies in this category and the lack of practical value for this information when the findings are inconclusive.

Summary of the best available evidence for the primary prevention of sexual violence (SV) perpetration.

4. Conclusions and discussion

The current systematic review sought to address two key objectives in an effort to inform and advance the research and practice fields of sexual violence primary prevention. First, by examining evaluation research on the primary prevention of sexual violence perpetration over nearly 30 years, we aimed to describe and assess the breadth, quality, and evolution of evaluation research and prevention programming in order to identify gaps for future development, implementation, and evaluation work. Second, we categorized sexual violence prevention programs on their evidence of effectiveness in an effort to inform decision-making in the practice field based on the best available research evidence.

4.1. State of the field: research on the primary prevention of sexual violence perpetration

In the last three decades, a sizable literature has emerged examining the effectiveness of strategies to prevent sexual violence perpetration with more than 100 evaluation reports identified since 1985. The number of studies published in the last two years of this review increased notably, suggesting a possible resurgence of research interest in this area. However, our results suggest that the sexual violence prevention evaluation literature has not seen a steady increase in publications over time to mirror the large increases in other types of sexual violence research. A bibliometric analysis of sexual violence research found that publications with the keywords “rape,” “sexual assault,” or “sexual violence” increased over 250% between 1990 and 2010, from approximately 5990 citations in 1990 to about 15,400 citations in 2010 ( Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2012 ). Despite this marked increase in general research attention to sexual violence, the current review suggests that the prevention evaluation literature has remained relatively stagnant both in terms of quantity and quality. In part, this trend may reflect the relatively limited resources available during this period for development and rigorous evaluation of sexual violence primary prevention approaches ( Jordan, 2009 ; Koss, 2005 ). Fortunately, funding for sexual violence evaluation research has increased over the last decade. For example, CDC funded 27 research projects with a focus on sexual violence between 2000 and 2010, resulting in the increased availability of more than $19 million in federal funding for the field; more than half of these projects involved prevention evaluation research ( Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2012 ; DeGue, Simon, et al., 2012 ). Although this funding represents a large proportional increase in federal dollars available for sexual violence research, the total research funding available remains low compared to other forms of violence and other areas of public health ( Backes, 2013 ; DeGue, Massetti, et al., 2012 ).

In addition to limiting the quantity of evaluation research studies, fiscal constraints may have also resulted in less rigorous research designs, as large randomized controlled trials of prevention strategies are generally considered costly to implement. Indeed, this review found two-thirds of the evaluation studies conducted over nearly 30 years examined brief, one-session interventions with college populations, approaches that are relatively inexpensive to implement and evaluate. In terms of measurement, few of these studies ( n = 11) measured sexually violent behavior, and none found consistently positive effects on these key behavioral outcomes. Of course, the predominance of brief awareness and education strategies in the literature not only reflects resource limitations for research but also implementation challenges in the field. Many colleges may limit access to students to only one class period or have policies requiring only 1 h of relevant training—spurring the development of programs to fit this need. Nevertheless, future research is needed that rigorously evaluates a more diverse and comprehensive set of prevention approaches with various populations.

Although the vast majority of preventative interventions evaluated to date have failed to demonstrate sufficient evidence of impact on sexual violence perpetration behaviors, progress is being made. Findings from several large, federally-funded 7 effectiveness trials of comprehensive, multi-component primary prevention strategies have been published more recently, with interventions targeting a broader, and younger, segment of the population (e.g., Foshee et al., 2004 , 2012 ; Miller et al., 2012b ; Taylor et al., 2013 ) with additional evaluations underway (e.g., Cook-Craig et al., in press ; Espelage, Low, Polanin, & Brown, 2013 ; Tharp, Burton, et al., 2011 ). This new research is providing the primary prevention practice field with additional evidence on which to base decisions about resource allocation and implementation in order to prevent sexual violence. However, as we discuss below, more rigorous evaluation research on various prevention approaches is needed before we can expect to see measurable reductions in sexual violence at the population level.

4.1.1. Evaluation methodology

A movement toward evidence-based policymaking has been gaining traction in the US. In 2012, the U.S. Office of Management and Budget directed federal agencies to prioritize rigorous research evidence in budget, management, and policy decisions in order to improve effectiveness and reduce costs ( Office of Management & Budget, 2012 ). These shifting federal priorities reflect a growing push in the field by researchers and advocacy organizations such as the Coalition for Evidence-Based Policy ( www.coalition4evidence.org ) for increased investment in evaluation research and the implementation of evidence-based programs. Evaluation guidelines provided by these various stakeholders emphasize the value of well-conducted, rigorous evaluations with an emphasis on randomized controlled trials to permit the strongest possible conclusions regarding causality (e.g., Flay et al., 2005 ; Office of Management & Budget, 2012 ).

A small majority (58.6%) of the studies in this review utilized an experimental design with randomization, and about three-quarters of these collected follow-up data beyond an immediate post-test. Thus, fewer than half (45%; n = 63) of the included studies met our minimum criteria for a rigorous evaluation. Further, only 17 of the rigorous evaluations included measures of sexually violent behavior, the intended public health outcome of the programs. In summary, after nearly 30 years of research, the field has produced very few evaluation studies using a research design that, if well-conducted, would permit conclusions regarding the effectiveness of the intervention for preventing sexually violent behavior. This shortage of rigorous research accounts, in large part, for the lack of evidence-based interventions available to practitioners to date.

The use of less rigorous methodologies, such as single-group or quasi-experimental designs, is often necessary and cost-effective for the purposes of program development, improvement, and to establish initial empirical support for an intervention ( Tharp, DeGue, et al., 2011 ). However, there is an implicit expectation that the rigor of evaluation research will continue to increase over time, both for individual interventions with promising initial outcomes and for the literature as a whole ( Tharp, DeGue, et al., 2011 ). However, this review did not find evidence of a general shift toward more rigorous evaluation methodology in the field over time. A comparison of studies published before and after 2000 found that evaluations completed from 2000 to 2012 were actually less likely to utilize an experimental design with randomization (53.7% vs. 63%) and more likely to utilize a pre–post design (26.9% vs. 6.8%) than studies from 1985 to 1999. Further, most of the identified interventions were the subject of a single evaluation rather than an evolving program of research, regardless of the initial study quality or findings. Progress in the field is dependent on systematic research initiatives that build off of the existing evidence base and move toward the ultimate goal of identifying “what works”.

4.1.2. Prevention approach

Much has been learned from the prevention science and public health fields about the characteristics of effective prevention strategies. For example, Nation et al. (2003) identified nine “principles of prevention” that were strongly associated with positive effects across multiple literatures and found that effective interventions had the following characteristics: (a) comprehensive, (b) appropriately timed, (c) utilized varied teaching methods, (d) had sufficient dosage, (e) were administered by well-trained staff, (f) provided opportunities for positive relationships, (g) were socio-culturally relevant, (h) were theory-driven, and (i) included outcome evaluation. Similar sets of “best practices” for prevention have been articulated elsewhere (e.g., Small, Cooney, & O’Connor, 2009 ). With the exception of outcome evaluation which we addressed above, we consider how well the sexual violence literature to date aligns with each of these principles.

4.1.2.1. Comprehensive

Comprehensive strategies should include multiple intervention components and affect multiple settings to address a range of risk and protective factors for sexual violence ( Nation et al., 2003 ). However, the vast majority of interventions evaluated for sexual violence prevention have been fairly one-dimensional — implemented in a single setting, typically a school or college, and often utilizing a narrow set of strategies to address individual attitudes and knowledge related to sexual violence. A minority of programs included content to address individual-level risk factors other than attitudes and knowledge (e.g., relevant skills and behaviors). Fewer than 10% included content to address factors beyond the individual level, such as peer attitudes, social norms, or organizational climate and policies, despite evidence that relationship and contextual factors are also important in shaping risk for sexual violence perpetration ( Casey & Lindhorst, 2009 ; Tharp et al., 2013 ). Several relatively recent studies have evaluated interventions that utilize a more comprehensive approach by combining educational or skills-building curricula with social norms campaigns, policy changes, community interventions, and/or environmental changes (e.g., Ball et al., 2012 ; Foshee et al., 2004 ; Taylor et al., 2011 ); however, comprehensive interventions remain the exception and not the norm. In order to potentially reduce and prevent sexual violence, program developers should build off of this work and develop a range of comprehensive strategies geared toward multiple populations.

4.1.2.2. Appropriately-timed

More than two-thirds of sexual violence prevention strategies evaluated thus far have targeted college samples. There is consensus that college men and women are at a particularly high risk for sexual violence perpetration and victimization, making this a key population for intervention. However, because many college men have already engaged in sexual violence before arriving on campus or will shortly thereafter ( Abbey & McAuslan, 2004 ), prevention initiatives that address this age group may miss the window of opportunity to prevent sexual violence before it starts. Primary prevention efforts may be best targeted at younger populations—before college. Sexually violent behavior is often initiated in adolescence ( Abbey & McAuslan, 2004 ), and more than 40% of victims will experience their first completed rape before age 17 ( Black et al., 2011 ). Only about one-quarter of the studies reviewed here evaluated interventions in high schools, middle schools, or elementary schools. However, younger populations are getting increased attention from program developers and evaluators in recent years. One-third of the evaluations involving school-aged youth in this review were published in 2010 or later, and several randomized trials of school-based strategies are underway in the field ( Cook-Craig et al., in press ; Espelage et al., 2013 ; Tharp, Burton, et al., 2011 ). It is notable that the only strategies with evidence of effectiveness on sexually violent behavior, to date, target adolescents. This is consistent with findings from a recent review of intimate partner violence prevention strategies ( Whitaker, Murphy, Eckhardt, Hodges, & Cowart, 2013 ), suggesting that adolescence may represent a critical window to intervene on these related behaviors. Better targeting our prevention strategies to adolescents and evaluating these efforts into the college years will aid in our understanding about the preventative effects of these interventions.

4.1.2.3. Varied teaching methods

Research indicates that preventative interventions are most successful when they include interactive instruction and opportunities for active, skills-based learning ( Nation et al., 2003 ). Prior reviews of sexual violence prevention programs also suggest that engaging participants in multiple ways (e.g., writing exercises, role plays) and with greater participation may be associated with more positive outcomes ( Paul & Gray, 2011 ). In the current review, nearly one-third of interventions utilized a single mode of intervention delivery (or teaching method) and another 40% utilized two modes of instruction. The most common modes of intervention delivery involved interactive presentations (i.e., presentations with opportunities for questions or discussion), didactic-only lectures, and/or videos. Only about one-third of the programs involved active participation in the form of role playing, skills practice, or other group activities. The effectiveness of program development efforts may be increased by focusing on integrating more active learning methods in order to increase the likelihood that participants acquire and retain skills and knowledge.

4.1.2.4. Sufficient dose

Prevention approaches must provide a sufficient “dose” of the intervention, as measured by total exposure to program content or contact hours, to have an effect on the behavior of participants ( Small et al., 2009 ). The intensity needed to be effective will vary by the type of approach, the needs and risk level of participants, and the nature of the targeted behavior, but longer programs may be more likely to achieve lasting results ( Nation et al., 2003 ). Our findings suggest that the dose received by participants is often small. Three-quarters of interventions had only one session, and half of all studies involved a total exposure of 1 h or less. While it may be possible to impact some behaviors with a brief, one-session strategy, it is likely that behaviors as complex as sexual violence will require a higher dosage to change behavior and have lasting effects. Indeed, we found that interventions with consistently positive effects in this review tended to be 2 to 3 times longer, on average, than interventions with null, negative, or mixed effects. Of course, there are practical limitations on the time and resources available to implement prevention strategies in most settings. The most efficient interventions would balance the necessity of providing a sufficient dose to achieve intended outcomes with the need for long-term sustainability and scalability. But, outcomes are critical: No matter how brief or low-cost an intervention may be, if it does not impact the outcomes of interest, implementation will not be an efficient or effective use of resources.

4.1.2.5. Fosters positive relationships

Strategies that foster positive relationships between participants and their parents, peers, or other adults have been associated with better outcomes in past prevention research ( Nation et al., 2003 ). Although the short length and didactic nature of most interventions reviewed here do not lend themselves well to relationship-building, strategies that work to nurture or capitalize on positive relationships are beginning to gain traction in the field. For example, programs that engage youth in facilitated peer support groups (e.g., Expect Respect; Ball et al., 2012 ) can leverage positive peer influences to reduce violent behavior. Further, strategies that train and empower youth to serve as active bystanders (e.g., Bringing in the Bystander; Banyard, Moynihan, & Plante, 2007 ; or, Green Dot; Cook-Craig et al., in press ) utilize existing peer networks to diffuse positive social norms and messages about dating and sexual violence. In addition, recent work to involve parents in dating violence prevention is a promising new direction (see for example, Families for Safe Dates ; Fo et al., 2012). Although these particular interventions have not yet demonstrated effects on sexual violence perpetration in a rigorous evaluation, research is ongoing, and the attention to the role of relationships in behavior modification and risk may prove fruitful.

4.1.2.6. Sociocultural relevance

Prevention programs that are sensitive to and reflective of community norms and cultural beliefs may be more successful in recruitment, retention, and achieving outcomes ( Nation et al., 2003 ; Small et al., 2009 ). Only three interventions were identified that included content designed for specific racial/ethnic groups, including Asian-Pacific Islander ( Stephens, 2008 ), African-American ( Weisz & Black, 2001 ) and Latino/a ( Nelson et al., 2010 ) populations. Fourteen studies (10% of the total) evaluated programs targeting fraternity men, male athletes, or members of the military. No studies evaluated programs targeting sexual minority populations. Overall, about two-thirds of the interventions reviewed were implemented with majority-White samples. Nation et al. (2003) note that involving members of the target population in the development and implementation of prevention strategies may improve the programs’ perceived relevance to the community’s needs. Future program development and evaluation research efforts should gauge the extent to which interventions with culturally specific approaches result in increased cultural relevance, recruitment, retention, and impact on preventing sexual violence.

4.1.2.7. Well-trained staff

Effective programs tend to have staff or implementers that are stable, committed, competent, and can connect effectively with participants ( Mihalic, Irwin, Fagan, Ballard, & Elliott, 2004 ). Sufficient “buy-in” to the program model is also important to credibly deliver and reinforce program messages ( Nation et al., 2003 ). Although researchers are increasingly recognizing the importance of measuring and describing characteristics of implementers and training procedures, few reports included this information. Reports were typically limited to a basic description of the type of implementer (e.g., peer, school staff, professional). About one-quarter of the interventions were implemented by professionals with expertise related to sexual violence prevention and extensive knowledge of the program model (e.g., program developers, sexual violence prevention practitioners). The majority of programs were implemented by peer facilitators, advanced students, or school/agency staff who may not have specific expertise in the topic. The sexual violence prevention field would benefit from more extensive descriptions of program staff and training and implementation research to determine characteristics of program staff that may enhance the preventative effects of our programs.

4.1.2.8. Theory-driven

A recent review by Paul and Gray (2011) concluded that sexual violence prevention strategies often lack a strong theoretical framework and fail to utilize established social psychological and behavior change research to inform program development. Etiological theories that identify modifiable points for intervention in the development of health risk behaviors are extremely valuable as a basis for prevention development ( Nation et al., 2003 ), especially when supported by evidence that the factors identified represent causal influences in a theoretical model. Although we did not systematically examine the theoretical underpinnings of interventions, attention to etiological theory (e.g., risk and protective factors and processes; Nation et al., 2003 ) was implicit in many studies with a focus on changing presumed sexual violence risk factors. The most common risk factors addressed were knowledge and attitudes about rape, women, and sex. There is limited empirical evidence linking legal or sexual knowledge to sexual violence perpetration ( Tharp, DeGue, et al., 2011 ) and virtually no theoretical reason to believe that rape is caused by a lack of awareness about laws prohibiting it. However, education about rape laws and statistics remains a frequent component of sexual violence prevention strategies. Attitudes are similarly attractive targets for intervention because they are relatively easy to measure and assess for change in the short-term. However, more empirical and theoretical work is needed to establish these factors as functional pieces in violence development rather than merely correlates or indicators and to provide well-developed, integrative theories to explain the role of attitudes and their potential value as primary prevention targets. On the other hand, cognitive factors, including hostility toward women, traditional gender role adherence, and hypermasculinity, have shown consistent links to sexual violence perpetration ( Tharp et al., 2013 ) but are rarely addressed directly in prevention programs. Strategies that involve working with young men to shape and support healthy views of masculinity and relationships, such as Men Can Stop Rape ( www.mencanstoprape.org ) or Coaching Boys into Men ( Miller et al., 2012b ), are promising exceptions, but more evaluation research is needed in order to ascertain whether these programs have an impact on sexual violence.

4.2. What works (and what doesn’t) to prevent sexual violence perpetration?

Emphasizing rigorous evaluation and behavioral outcomes, we developed and applied a set of criteria to identify specific interventions with more or less evidence of effectiveness for the primary prevention of sexual violence perpetration in order to serve as a guide for decision-making. Communities and organizations are increasingly interested in and required to implement evidence-based interventions with an expectation of achieving reductions in sexual violence. Table 3 is intended to serve as a resource and tool for this purpose. Although we believe that this approach has many practical advantages, it has notable limitations as well. Most importantly, it is limited by the ever-growing and evolving nature of the evaluation research literature. Over time, additional effective interventions will be identified, some will be found to be ineffective, and others will find that their effects can be replicated—or not—in different populations. The current review provides only a snapshot of knowledge regarding “what works” currently to prevent sexual violence. Practitioners are encouraged to consider this information in the context of the needs, goals, and resources of their organization and to supplement this summary with additional information about the strategy and new research findings as they become available. This summary may also be useful in identifying promising strategies in need of further research or when developing new comprehensive strategies that combine the strengths of multiple evidence-based approaches. Future research investments should reflect the best available science and theory, and move beyond approaches that have proven ineffective or insufficient.

4.2.1. What works (so far)?

Only three strategies, to date, have evidence of at least one positive effect on sexual violence perpetration behavior using a rigorous, controlled evaluation design. The best available evidence suggests that these strategies, if well-implemented with an appropriate population, may be effective in preventing sexually violent behavior. Notably, none of these evaluations have been replicated and it is not known whether their effects will generalize to other populations, age groups, or to forms of sexual violence that were not assessed. In addition, it is likely that none of these approaches, in isolation, will be sufficient to reduce rates of sexual violence at the population-level, even if brought “to scale” ( Dodge, 2009 ). Instead such approaches should be viewed as potential components of an evidence-based, comprehensive, multi-level strategy to combat sexual violence.

Safe Dates is a universal dating violence prevention program for middle- and high-school students involving a 10-session curriculum addressing attitudes, social norms, and healthy relationship skills, a 45-minute student play about dating violence, and a poster contest. Results from one rigorous evaluation using an RCT design showed that four years after receiving the program, students in the intervention group were significantly less likely to be victims or perpetrators of self-reported sexual violence involving a dating partner relative to students in the control group ( Foshee et al., 2004 ).

Shifting Boundaries is a universal, school-based dating violence prevention program for middle school students with two components: a 6-session classroom-based curriculum and a building-level intervention addressing policy and safety concerns in schools. Results from one rigorous evaluation indicated that the building-level intervention, but not the curriculum alone, was effective in reducing self-reported perpetration and victimization of sexual harassment and peer sexual violence, as well as sexual violence victimization (but not perpetration) by a dating partner ( Taylor et al., 2011 , 2013 ).

The U.S. Violence Against Women Act of 1994 (VAWA) aimed to increase the prosecution and penalties associated with sexual assault, stalking, intimate partner violence and other forms of violence against women, as well as to fund research, education and awareness programs, prevention activities, and victim services ( Boba & Lilley, 2009 ). Results of a rigorous, controlled quasi-experimental evaluation suggest that VAWA-related grant funding through the U.S. Department of Justice for criminal justice-related activities was associated with a .066% annual reduction in rapes reported to the police, as well as reductions in aggravated assault. Given the deficit of policy, environmental, or community-level change strategies with empirical, or even theoretical, evidence in this field ( DeGue, Holt, et al., 2012 ), communities and researchers may be able to learn from the programs and strategies funded by VAWA to inform development or implementation of similar approaches to prevent sexual violence.

4.2.2. What (probably) doesn’t work, or might be harmful?

This review identified five interventions with evidence of null effects on sexually violent behavior in at least one rigorous evaluation. It is notable that most of these programs have shown positive effects on other related outcomes, including potential risk factors or moderators. In some cases, positive effects on behavioral outcomes were identified using non-rigorous evaluation designs. Additional research that evaluates these strategies with different measures of sexual violence perpetration, stronger implementation, different populations, longer follow-up periods, or larger sample sizes may possibly reveal positive effects on behavior. However, the most rigorous evidence currently available suggests that these strategies have so far not been effective in changing rates of sexual violence perpetration after a reasonable follow-up period.