Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Persuasive essay about smoking(tagalog)

Related Papers

Danica Lorraine Garena

Ang pag-aaral na ito ay isinagawa upang mabatid ang pananaw ng mag-aaral sa paggamit ng mga sariling komposisyon ng panitikang pambata at antas ng pang-unawa. Sa pag-aaral na ito binibigyang katugunan ang mga sumusunod na katanungan: Ano ang pananaw ng mga tagasagot sa paggamit ng mga Sariling Komposisyon ngPanitikang Pambata bataysa nilalaman,layunin,disensyo/istilo, kasanayan/gawain; Ano ang antas ng pang-unawa ng mga tagasagot sa paggamit ng mga Sariling Komposisyon ng Panitikang Pambata batay sa Pang-unawang Literal at Pang-unawangKritikal; May makabuluhang kaugnayan ba ang pananaw ng mag-aaral sa paggamit ng mga Sariling Komposisyon ng Panitikang Pambata at Antas ng Pang- unawa sa Pagbasa; Ang pamamaraang palarawan-correlation ang ginamit ng mananaliksik upang makalap ang mahalaga at makatotohanang impormasyon na kinakailangan sa pag-aaral. Ang istatistikal na pamamaraan na ginamit sa pagsasaliksik ay weighted mean at standard deviation para sa pananawng mga tagasagot sa Mga Sa...

Robert Paull

Mansa Gurjar

Folia Linguist

Yves Duhoux

Teaching Mathematics and Computer Science

Bujdosó Gyöngyi

Germinal: Marxismo e Educação em Debate

Newton Duarte

Mohammed Koya

Journal of Public Economics

Maria Gallego

Debajit Sarma

RELATED PAPERS

Nicolae M Vasiliu

Revue Organisations & territoires

Yves Robichaud

philippe beriro

Paweł Maksimowski

3D Printing and Additive Manufacturing

Zachary Bushman

Larisa Spinei

Asian Social Science

Mohd Khirzan A Rahman

Gaceta medica de Mexico

eduardo meaney

Frontiers in Oncology

Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária

Mohamed Abumandour

Book of Abstracts, Meeting of the Working Group Seed Science and Certification (GPZ/GPW) & Section IV Seeds (VDLUFA), “Seed Production in Times of Climate Change”, 9-11 March 2021, Online

Simona Jaćimović

Parkinsonism & Related Disorders

Imad ghorayeb

International Journal for Parasitology

Puspa Sari 2211166169

Jean-Paul BENTZ

Davide Rigon

Middle School Journal

Eric Anderman

Beatrice Rivalta

Clinical Neurophysiology

Hannah Smithson

Journal of Clinical Investigation

Felipe Nuñez

Journal of IMAB - Annual Proceeding (Scientific Papers)

Stefan Todorov

arXiv (Cornell University)

Andrew Schofield

BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation

Wolfgang I Schöllhorn

Medieval Archaeology

Søren Sindbæk

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Sanaysay Tungkol sa Nationwide Smoking Ban

Hindi dahil sa amoy nito o sa dating ng taong gumagamit, ngunit dahil sa nakababahalang epekto nito sa ating kalusugan — gumagamit ka man nito o hindi.

Napapanahon na ang nationwide smoking ban sapagkat lalong tumataas ang bilang ng mga Pilipinong nasasawi dahil sa mga sakit na may kinalaman sa baga, at ang isa sa mga sanhi nito ay ang sigarilyo.

Ang itinuturong dahilan, ang paninigarilyo. Dahil hindi agad nakikita ang komplikasyon ng paninigarilyo tulad ng unti-unting pagkasira ng baga, ay hindi naaagapan ang gamutan sa mga tinatamaan ng komplikasyon.

Kaya naman kung nais nating mapababa ang problema sa mga sakit na may kinalaman sa baga, dapat nang ipatupad ang nationwide smoking ban bago mas maraming baga pa ang maupos na parang sigarilyo.

Mga Karagdagang Sanaysay

- Sanaysay Tungkol Sa Enhanced Community Quarantine

- Sanaysay Tungkol Sa Online Class

- Sanaysay Tungkol Sa Karapatang Pantao

July 2021 — Volume 5, Issue 1 Back

“stop the puff tayo’y mag bagong baga, sigarilyo ay itigil”: a pilot community-based tobacco intervention project in an urban settlement.

Irene Salve D. Joson-Vergara, Julie T. Li-Yu

Jul 2021 DOI 10.35460/2546-1621.2020-0040

- PDF Download

Figures and Tables

Introduction.

Tobacco use continue to be one of the leading cause of death and disability worldwide. Around 8 million deaths worldwide each year are tobacco related, 7 million of which are attributed to direct tobacco use while around 1.2 million are due to exposure to secondhand smoke. There are around 1.1 billion smokers worldwide and 80% of these live in low- and middle-income countries [1] . The Philippines is one of the countries in the Western Pacific region with the highest prevalence of tobacco use [2] and seven out of the 10 leading cause of mortality in the country is tobacco related. [3] The Philippine government has intensified its efforts to curb smoking, focusing mainly on policies that target the wider determinants of health such as smoking bans, graphic health warnings and sin tax law. These efforts have resulted to a significant decrease in the prevalence of smoking from 17.3 million in 2009 to 15.9 million in 2015. Also, the number of smokers who are interested in quitting increased by 16.3% from 2009 to 2015. However, those interested in quitting that were seen by a health care provider did not increase significantly and only around half made a quit attempt. More importantly, the quit success rate did not increase. [4] This demonstrates a wide disparity between the number of smokers who want to quit and the number who are able to quit successfully. This gap may be addressed by strengthening health care interventions especially among smokers that are heavily dependent on nicotine. There may be a need to complement national policies with programs that target the specific needs of smokers.

Brief Tobacco Intervention (BTI), also known as brief advice, is a strategy that is proven to be effective, practical and doable in the community setting. [5] Unfortunately, cessation experts in the country are few and healthcare workers with training on tobacco interventions are limited.

The primary objective of the project was to establish smoking cessation intervention in the community by empowering health workers and community volunteers on giving BTI and to improve access to cessation support by establishing a referral mechanism to smoking cessation services. The project also aimed to promote smoking cessation in the community through health education activities that promote smoke-free behavior and encourage smoking cessation among current smokers.

Review of Related Literature

Studies have shown that the outcome of quit attempt is related to various individual, socio-cultural and environmental factors. [6-13] Some factors were consistently shown to be related to quit success but there are certain factors that differ in every population. Studies done among smokers in South Africa, USA and South Korea showed that higher educational level is related to quit success. [6-8] However, in a similar study done in Brazil, this was correlated with failure. [9] Being married was associated with quit success in the studies done in USA and in South Korea [7,8] however, this was not seen in the study done in South Africa. [6-10] It can be surmised therefore, that cultural, social and behavioral aspects of smoking that affect quit outcomes may be unique in each population or community (Table 1, Appendix A).

DiGiacomo et al [14] recommends a multi-faceted approach in smoking cessation, taking into consideration the individual and socio-cultural factors that are unique to each community. These factors are usually not targeted by national policies that focus on the wider determinants of health. Community-based interventions, on the other hand, may better address these factors. There is also evidence that community-based interventions and those that are tailored to specific indigenous groups have greater retention and quit success rates compared to center-based interventions. [14-20] These suggest that establishing a community-based smoking cessation intervention is effective and feasible (Table 2, Appendix A).

Methodology

The project was done in three phases as described in Table 3. A health needs assessment and situational analysis were done in the first phase. This involved an appraisal of the attributes of the community and an analysis of the specific needs of the community pertaining to tobacco control. This was done primarily through review of secondary data, focus group discussions (FGDs) and informal interviews. The primary goals of the FGDs were to understand the general views of the community on tobacco, determine the level of awareness on its effects and identify misconceptions on tobacco use and smoking cessation. The findings were used to modify the design of the training and health education modules to better fit the needs and attributes of the community.

Phase 2 of the project involved the conduct of BTI training for health workers and volunteers in Munting Ilaw health center. The training was done in two separate sessions to align with the health workers' schedule and minimize interruption in the delivery of services of the health center. The target number of participants was 30, in accordance with the WHO recommendations. [5] The general objective of the seminar and workshop is to capacitate the participants on the method of conducting brief tobacco intervention. The module used was adopted from the BTI module of the Department of Health [21] and modified based on the result of the situational analysis. It consisted of 5 modules namely: 1. Building the Momentum; 2. Brief tobacco Intervention Essentials; 3. Not ready to quit; 4. Ready to quit; and 5. Staying quit or relapse. The description, contents, methodology and resources of the modules are summarized in Table 5 (Appendix B). Gaps in knowledge, concerns and misconceptions identified during the FGDs were given emphasis during the training. Possible referral mechanisms to smoking cessation services were discussed at the end of the session.

Phase 3 of the program involved health promotion activities such as information campaign on the dangers of smoking and promotion of smoking cessation services. This was done in the form of a lay fora.

The actual schedule of the conduct of activities is presented in Table 4.

Observations and Results

A. Health Needs Assessment

1. Health Profile of the Community

The project was implemented in Phase 1-K Kasiglahan Village, Barangay San Jose, Rodriguez Rizal where a memorandum of agreement exists between Barangay San Jose and the University of Santo Tomas, Master in Public Health (International) program. Kasiglahan Village is situated in Barangay San Jose which is one of the eleven barangays in Rodriguez Rizal. Although originally an agricultural land, the area has undergone massive development over the recent years and is now considered as an urban area. It is the 6 th most populated barangay in Rodriguez with a population of 124,868 in 2015. This population has grown quite rapidly over the past few decades largely due to the development of relocation sites that catered to displaced families from Quezon City and other cities surrounding the Pasig river. Kasiglahan Village is one example of these developments, with residents mostly relocated from Quezon City areas. [22] There are several health facilities within Rodriguez Rizal. The Rural Health Unit is manned by the rural health officer, physicians, nurses, midwives, sanitary inspectors and malaria officers. There is a 25-bed infirmary (Montalban Infirmary) that is located in Kasiglahan Village and a government health facility (Casimiro Ynares Sr. Memorial Hospital). Other private health providers likewise exist which include hospitals, lying-in clinics and multi-specialty clinics. Each barangay has at least one health center with some having satellite health centers. Hospitals outside of the municipality are also easily accessible through jeepneys and other public utility vehicles. Based on the interviews with the residents and health workers from Kasiglahan Village, patients needing tertiary care are usually brought to hospitals in Metro Manila such as East Avenue Medical Center in Quezon City and Amang Rodriguez Memorial Medical Center in Marikina City. These hospitals are what they deem as the most accessible and capable of providing higher level of healthcare. Munting Ilaw Health Center is a satellite health center of Barangay San Jose and is located in Kasiglahan Village. It is tasked to provide basic health services to the residents of Kasiglahan Village such as maternal and child health, family planning, immunization, and nutrition. It also houses a directly observed treatment short-course (DOTS) clinic for the management of tuberculosis. It is manned by nurses, midwives, barangay health workers, municipal health workers and volunteers. The leading causes of morbidity in Rodriguez Rizal in 2012 include: 1. Animal Bite; 2. Acute upper respiratory tract infection; 3. Pulmonary tuberculosis; 4. Dengue; 5. Asthma; 6. Acute rhinitis; 7. Acute gastroenteritis; 8. Hypertension; 9. Body injuries and 10. Pharyngitis. Mortalities are mostly due to cardiac causes such as myocardial infarction. Other causes of death include community acquired pneumonia, cancer (mostly of the lung), intra-cerebral hemorrhage, pulmonary tuberculosis and non-disease related deaths due to body injuries and gunshot wounds. [22]

2. Tobacco cessation services and policies in the community None of the existing health facilities within the municipality have an existing tobacco cessation service and there is no smoking cessation clinic anywhere in the municipality and in nearby areas. The municipality has a newly drafted tobacco-free resolution; however, it has not been fully implemented at the time of the implementation of this project. There is an existing ordinance prohibiting smoking in public spaces. This is strictly implemented in the city proper and major establishments but not so much in the communities.

3. Tobacco interventions from the perspective of health workers. The FGD was attended by 24 health workers. The goal of the discussion was to determine the general perception of the workers on smoking cessation interventions and the usual practices in the health center in order to identify possible strategies to integrate BTI in their existing programs. None of the health workers had attended any seminar on or related to BTI. Advise on smoking cessation and inquiry regarding the smoking status is not customarily done in any of the existing programs of the health center, except in the TB Directly Observed Treatment Short-Course (TB-DOTS) clinic wherein the smoking status of each patient is included in the patient’s record. Even so, giving advice is done inconsistently. Most did not know that BTI can be integrated in all of their programs and only a few recognized the relevance of BTI in their particular line of work (i.e. family planning, nutrition). None were aware of the existence of the National Quitline and no referral mechanism to cessation providers exists.

4. Understanding the perspective of current smokers. FGDs were done to better understand the predicament of smokers in the community. FGDs were done instead of formal interviews with structured questionnaire to allow free flow of thoughts and ideas and thereby be able to capture aspects that are not obtained by the Philippine Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS). Most of the participants initiated their smoking habit during their teen years and curiosity was the most common reason for trying. Most had the initial intention to just satisfy their curiosity but eventually got hooked to habit. One of the participants started using chewed tobacco at the age of five. Her parents were tobacco farmers and it was customary for them to chew tobacco leaves while farming. She transitioned to cigarette smoking during her teen years and maintained the smoking habit until adulthood. All of them agreed that it was easy to initiate and maintain the smoking habit because tobacco products were widely available, easily accessible and, at the time of their smoking initiation, very affordable. They are aware of the ill-effects of tobacco on their health, however, there is a general perception that these ill-effects are unlikely to happen to them. And if it does, they are resigned to accept it as an inevitable consequence of their smoking habit. Most are willing to quit “when it is absolutely necessary”, however, they do not foresee that they will be able to do so in the near future. This implies that the motivation to quit is generally low. When asked about possible motivations for them to quit, answers included: further price increase in tobacco products, development of health complications and total smoking ban. Tobacco products are also prioritized over other necessities such that they will go to the extent of borrowing money or forego one meal in order to sustain the smoking habit. There is a deep understanding of the current tobacco control policies and the intentions of such policies. However, these did not seem to deter the smoking habit as they were able to adapt to these policies. The smoking ban is not strictly enforced in the community; hence they are able to smoke freely while they are in the community. When going to the city proper or while at work where smoking ban is strictly enforced, they are able to decrease their cigarette consumption. The graphic health warnings on cigarette packages was likewise not enough to dissuade them from smoking because they usually buy individual sticks instead of packs. Others cover graphic warnings in the packaging while some think that the pictures are not real and were only meant to scare them. None of the participants had ever received advice from health workers but most of them will likely avail of smoking cessation services if it is available in the community. None were aware of the National Quitline and most are quite skeptic if it is functional.

5. Lessons from the former smokers. Similar to the FGDs with smokers, the questions during the discussions with former smokers revolved around the initiation of the smoking habit, knowledge of the ill effects of tobacco and views on current national and local tobacco control policies and how it influenced their quit journey. In addition to these, the discussion also focused on the motivation/s for quitting and the challenges encountered during their quit journey. The common motivation to quit was health reasons since all of the participants were diagnosed with a tobacco-related illness that led to the decision to quit. Most of the participants were only given very brief advice by their physicians and all were able to quit completely, unassisted (“cold turkey” style), and without using any pharmacologic treatment for tobacco dependence. The biggest challenge for most of them was seeing other people smoke, especially during gatherings and special occasions. The urge to relapse into the smoking habit was easier to resist after a few weeks of being tobacco-free. Although they fully support the existing tobacco control policies, most claim that it had little impact on their motivation to quit. The graphic health warnings had some influence in their decision to quit, but seeing real patients with tobacco related illnesses on TV was a stronger motivation for them. When asked about their views on providing cessation services in the health center, most deemed it unnecessary since smokers will quit unassisted for as long as they are motivated. To encourage smokers to quit, they think that it is important to find the right motivation because it is easier to quit when the motivation is strong.

6. Protecting the non-smokers. The discussions with non-smokers, particularly the ones who are exposed to second-hand smoke in their homes, focused on questions about their feelings about the smoking behavior of their loved ones or household members and how they think it will affect them and the other members of the family. The participants were also asked how they deal with the smoking behavior of the household member/s. Most of the participants were spouses of smokers. All of the participants do not condone the smoking behavior of their spouses; however, they feel that their sentiments and objections to the smoking habit are being disregarded. They are fearful of the ill-effects of smoking to the health of their spouses and their children as well. As most of their spouses are breadwinners, the smoking habit is a source of anxiety and worry about the future of the family should their spouse develop a tobacco related illness. Unfortunately, these feelings of fear, apprehension and anxiety are often invalidated. Attempts to encourage the spouses to quit smoking are seldom done because discussions on the need to quit often leads to disagreement and tension in the household. Most of the participants are aware of the ill-effects of second-hand smoke, but they are not aware of third- and fourth-hand smoke. They are receptive of the idea of having a cessation service in the community, however, they are not sure if their spouses will avail of the service or comply with the recommendations.

B. Brief Tobacco Intervention Seminar And Workshop At the start of the training, each of the participants were asked to write their job designation, job description and their perceived role in tobacco control. Most of the participants recognized their role as a source of information while a few recognized that they can be role models. The other roles that they can assume in tobacco control were discussed during the training. The first session consisted of modules 1 and 2 and was given mostly in a lecture format. This involved discussions on the mechanism of nicotine addiction, harms of tobacco, benefits of quitting, common misconceptions and the general approach to BTI. The second session consisted of Modules 3 to 5 and involved a discussion of the specific steps in giving brief tobacco intervention. An algorithm on how to approach each patient at various stages of quitting was presented in a workshop format wherein a video demonstration was presented after each lecture and the participants were asked to present a return demonstration. Feedback was given by the facilitator and also solicited from the rest of the audience. At the end of the session, the importance of a referral system to smoking cessation providers and clinics was discussed. Since there is no existing referral mechanism yet in the community, the participants were asked to brainstorm on the possible referral mechanism specifically in Rodriguez Rizal. These mechanisms were presented to the whole group and they were made to choose the most feasible, efficient and plausible mechanism. A pre- and post-test was also done evaluate the effectiveness of the training in terms of improving knowledge. Out of the 34 attendees, only 25 were able to accomplish both the pre- and post-test. It was evident that after the workshop, the mean test scores of the participants significantly improved (p<0.001). At an average, their test score increased by 2.08 points which translates to a 20.8% increase in baseline knowledge (95% CI: 1.35 to 2.81). To somehow ensure that the knowledge will be translated into practice, posters, guide cards and education materials were given to the health center and rural health unit (Appendix C).

C. Community Health Promotion And Education The community health education and promotion was done in conjunction with the health education and promotion activity for non-communicable diseases in the community. The findings in the FGDs were taken into consideration and misconceptions identified were corrected in the lay fora. The activity consisted of short lectures interrupted by games to break monotony and to maximize attention span and retention of concepts. The National Quitline was promoted and participants were encouraged to urge the smokers in the community to utilize this service. Education on how to give very brief advice while avoiding conflicts in doing so was also given. A pre- and post-test was done to measure the effectiveness of the lecture in augmenting the participant’s knowledge. Out of the 58 attendees, 37 completed the pre- and post-test. It was evident that after the lecture, the mean test score of the participants significantly improved (p<0.001). At an average, the test scores increased by 2.73 points which translates to a 27.3% increase in baseline knowledge (95% CI: 2.18 to 3.28).

The tobacco quit success rate in the Philippines continue to be dismal despite the government's efforts to curb smoking. Nearly half of smokers who are interested in quitting were not given proper advice by a health care provider. [4] In the community, several factors contribute to this (Figure 1). There is an apparent lack of cessation services. Health workers are not trained on brief tobacco intervention and a referral system to cessation support services is not in place. Misconceptions on tobacco cessation is also rampant even among health workers. Like in the rest of the country, tobacco products are widely available and easily accessible. On the contrary, access to nicotine replacement therapies is limited. The prices of cigarettes, even with the surge due to the sin tax law, are still affordable. There is an apparent lack of motivation for smokers to quit despite the graphic warnings and other policies that restrict access to tobacco products and decrease opportunity to smoke. Although a smoking ban exist, this is not uniformly enforced. These factors all contribute to the problem which is a low quit success rate. This in turn result to a myriad of complications such as high prevalence of smoking, high mortality and morbidity from tobacco related illnesses, ultimately leading to greater economic cost.

The objective tree (Figure 3) represents the possible solutions to the problems identified. The outcome that this project envisions is a high quit success rate in the community. However, not all of the interventions identified can be accomplished by this project. Restrictions to tobacco products, price increase and policies on the use of nicotine replacement therapies would need to be addressed by national and/or local government programs and policies. Instead, this project focused on community-based interventions such as the establishment of smoking cessation intervention and referral mechanism in the community health center and health education and promotion activities in the community.

In 2003, the Philippines, being a member of the WHO Western Pacific region, was required to implement the strategies in the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC). Bourne from this treaty, the Philippines drafted its National Tobacco Control Strategy (NTSC) for the years 2011-2016. It’s three main strategies focused on: 1. Promotion and advocacy for the complete implementation of the FCTC; 2. Mobilization for public action; and 3. Strengthening the organization capacity. [23] This project is consistent with the activities specified under strategy 3 namely: human resource development, smoking cessation and tobacco dependence treatment, public awareness and education. Likewise, it is consistent with one of the social sectoral objectives of the municipality which is "to implement sustainable preventive healthcare programs to lessen incidence of diseases caused by unhealthy lifestyle". [22]

Conclusion and Recommendations

The tobacco problem is centuries old and cannot be solved overnight. It is indeed complex and full of challenges. It was found in the situational analysis that the smoking habit can be initiated at the age of five. This means that tobacco use is not freely chosen and therefore there is a need to alter the general environment through interventions that target the wider determinants of health. Such policies already exist; however, it is essential to strengthen these policies and complement it with clinical interventions. According to the European Society of Respirology [24] , in order to achieve a smoke-free society, tobacco cessation should be supported from policy to clinical perspective. Community based interventions have been consistently shown to be effective in improving quit success rates. Although establishing a formal smoking cessation clinic in the community is ideal, the task may be challenging in a low resource setting as it will entail additional resources. Providing training to the existing health workforce and integrating brief tobacco intervention with the existing programs of the community health center may be more feasible. Likewise, creating a referral mechanism to smoking cessation providers and clinics may augment the efficiency of smoking cessation efforts in the community.

The project aimed to address the clinical aspect of tobacco control by establishing tobacco cessation services in the community. This pilot project has shown that providing brief tobacco training among health workers is feasible. There is a need to assess whether this knowledge is translated into practice and whether the training created attitudinal change as well.

Recommendations

It is important that tobacco control remain a priority despite the countless other health problems that need attention. Especially because 5 out of the top 10 causes of mortality in the municipality are tobacco related and 4 out of the 5 causes of mortality are due to tobacco related diseases [22] . A local smoke-free policy is essential and its prompt implementation is encouraged. Stricter and consistent enforcement of the smoking ban is likewise encouraged. Continued health education is necessary to contradict misconceptions on tobacco cessation. BTI training should likewise be cascaded in other health centers, with priority given to at least the head nurse and TB-DOTS nurses. Regular updating of the seminar, on a yearly or every two years basis, is likewise necessary. Once smoking cessation services are fully integrated in the programs of the health centers and more cessation providers are available, smoking cessation clinics in key institutions in the municipality can be established. In the meantime, while smoking cessation clinics are not yet available in the municipality, it is recommended to promote the use of the National Quitline.

Limitations

Tobacco control is multi-faceted and this project mainly focused on the clinical aspect. Although an increase in the knowledge of the participants was documented, whether this knowledge was translated into practice was not assessed. Measuring the impact of the project in terms of increasing quit success rate is likewise ideal but beyond the scope of the project.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The project was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the people and institutions that were instrumental in the accomplishment of this project.

- For their assistance, insights and valuable inputs:

Honorable Glenn Evangelista, Chairman of Barangay San Jose

Dr. Ma. Carmela V. Javier, Municipal Health Officer of Rodriguez Rizal

Community leaders of Phase 1K, Barangay Kasiglahan, Rodriguez Rizal

Dr. Leilani B. Mercado-Asis, Program Head, Master in Public Health (International), UST Faculty of Medicine and Surgery

- For providing the module for Brief Tobacco Intervention Training and health promotion and education materials:

Philippine College of Chest Physicians, Council on Control for Tobacco and Air Pollution

Dr. Glynna Ong-Cabrera, Chairperson

Dr. Marie Charisma Dela Trinidad

Ms. Riza SJ San Juan, RN, Nurse Coordinator, Smoking Cessation Program, Lung Center of the Philippines

Counselors and staff of the DOH National Quitline

- For their unwavering support throughout the conduct of this project from its conception to its realization:

UST FMS Master in Public Health (International) classmates and mentors

World Health Organization. WHO Tobacco Fact Sheet 2019. [Internet]. 2019 [cited 04 April 2019]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco

World Health Organization. WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco smoking. [Internet]. 2015 [cited 04 April 2019]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/156262/9789241564922_eng.pdf;jsessionid=8FA5678C2197750E092EFFACF9FD0F0E?sequence=

Philippine Statistics Authority. Registered Deaths in the Philippines, 2017. [Internet]. 2019 [cited 08 January 2020]. Available from: https://psa.gov.ph/vital-statistics/id/138794

Department of Health Philippines. Global Adult Tobacco Survey: Philippine Country Report, 2015. [Internet]. 2015 [cited 08 April 2019]. Available from: https://www.who.int/tobacco/surveillance/survey/gats/phl_country_report.pdf

World Health Organization Tobacco Free Initiative. Strengthening health systems for treating tobacco dependence in primary care. Building capacity for tobacco control: training package. [Internet]. 2013 [cited 05 January 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/tobacco/publications/building_capacity/training_package/treatingtobaccodependence/en/

Ayo-Yusuf O, Szymanski B. Factors associated with smoking cessation in South Africa. South African Medical Journal [Internet]. 2010;100(3):175–9. Available from: http://www.samj.org.za/index.php/samj/article/view/3842

Lee C, Kahende J. Factors Associated With Successful Smoking Cessation in the United States, 2000. Am J Public Health [Internet]. 2007 Aug;97(8):1503–9. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.083527

Yeom H, Lim H-S, Min J, Lee S, Park Y-H. Factors Affecting Smoking Cessation Success of Heavy Smokers Registered in the Intensive Care Smoking Cessation Camp (Data from the National Tobacco Control Center). Osong Public Health Res Perspect [Internet]. 2018 Oct 31;9(5):240–7. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.24171/j.phrp.2018.9.5.05

Azevedo RCS de, Fernandes RF. Factors relating to failure to quit smoking: a prospective cohort study. Sao Paulo Med J [Internet]. 2011 Dec;129(6):380–6. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1516-31802011000600003

Kim Y, Cho W-K. Factors associated with successful smoking cessation in Korean adult males: Findings from a national survey. Iran J Public Health. 2014;43(11):1486–96.

Khati I, Menvielle G, Chollet A, Younès N, Metadieu B, Melchior M. What distinguishes successful from unsuccessful tobacco smoking cessation? Data from a study of young adults (TEMPO). Preventive Medicine Reports [Internet]. 2015;2:679–85. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.08.006

Bacha ZA, Layoun N, Khayat G, Hallit S. Factors associated with smoking cessation success in Lebanon. Pharm Pract (Granada) [Internet]. 2018 Mar 31;16(1):1111. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.18549/PharmPract.2018.01.1111

Holm M, Schiöler L, Andersson E, Forsberg B, Gislason T, Janson C, et al. Predictors of smoking cessation: A longitudinal study in a large cohort of smokers. Respiratory Medicine [Internet]. 2017 Nov;132:164–9. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2017.10.013

DiGiacomo M, Davidson P, Abbott P, Davison J, Moore L, Thompson S. Smoking Cessation in Indigenous Populations of Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States: Elements of Effective Interventions. IJERPH [Internet]. 2011 Jan 31;8(2):388–410. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8020388

Estreet A, Apata J, Kamangar F, Schutzman C, Buccheri J, O’Keefe A-M, et al. Improving participants’ retention in a smoking cessation intervention using a community-based participatory research approach. Int J Prev Med. 2017;8:106.

Asvat Y, Cao D, Africk JJ, Matthews A, King A. Feasibility and Effectiveness of a Community-Based Smoking Cessation Intervention in a Racially Diverse, Urban Smoker Cohort. Am J Public Health [Internet]. 2014 Sep;104(S4):S620–7. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302097

Levinson AH, Valverde P, Garrett K, Kimminau M, Burns EK, Albright K, et al. Community-based navigators for tobacco cessation treatment: a proof-of-concept pilot study among low-income smokers. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2015 Jul 9;15(1). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1962-4

Li WHC, Chan SSC, Wan ZSF, Wang MP, Ho KY, LAM TH. Development of a community-based network to promote smoking cessation among female smokers in Hong Kong. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2017 Apr 11;17(1). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4213-z

Matthews AK, Li C-C, Kuhns LM, Tasker TB, Cesario JA. Results from a Community-Based Smoking Cessation Treatment Program for LGBT Smokers. Journal of Environmental and Public Health [Internet]. 2013;2013:1–9. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/984508

Whitehouse E, Lai J, Golub JE, Farley JE. A systematic review of the effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions among patients with tuberculosis. Public Health Action. 2018;8(2):37–49.

Department of Health. Brief Tobacco Intervention Training Module: October 2019; unpublished.

Municipality of Rizal. Situational Analysis Report: 2013;unpublished.

Department of Health, Philippines. Philippine National Tobacco Control Strategy. [Internet]. 2011 [cited 22 May 2019]. Available from: https://www.doh.gov.ph/sites/default/files/publications/NationalTobaccoControlStrategy%28NTCS%29.pdf

Fu D, Gratziou C, Jiménez-Ruiz C, Faure M, Ward B, Ravara S, et al. The WHO–ERS Smoking Cessation Training Project: the first year of experience. ERJ Open Res [Internet]. 2018 Jul;4(3):00070–2018. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00070-2018

Table 3: Project Design

Table 4: Actual Schedule of Activities

Figure1. Problem Tree

Figure 1 illustrates the problem tree wherein the low quit success rate is identified as the main problem that this project sought to address. The roots represent the factors that contribute to the problem while the branches represent the complications or effects of the main problem.

Figure 2: Alternative Tree

The alternative tree shows the contrast of the problem tree wherein the problem is converted into a positive outcome. The roots represent the factors that can contribute to the realization of this positive outcome and therefore the cascade of negative effects is prevented.

Figure 3. Objective Tree

The objective tree represents the possible solutions to the problems identified. The main objective of this project is to increase the quit success rate in the community. The roots represent the interventions that can help realize the objective.

APPENDIX A: SUMMARY OF REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE

Table 1: Summary of Studies on Factors Associated with Quit Outcomes

Table 2: Review of Articles on Community-based Smoking Cessation Services

APPENDIX B: BTI MODULE DESCRIPTION [21]

Table 5: Brief Tobacco Intervention Seminar and Workshop

APPENDIX C: POSTERS

Figure 4: The 5A’s in Brief Tobacco Intervention [21]

Figure 5: Readiness to change model [21]

Related content

Articles related to the one you are viewing.

There are currently no results to show, please try again later

Citation for this article:

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Public Health Action

- v.3(2); 2013 Jun 21

Language: English | French | Spanish

Addressing the tobacco epidemic in the Philippines: progress since ratification of the WHO FCTC

1 International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Edinburgh Office, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

2 Republic of the Philippines Department of Health, Manila, The Philippines

3 Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Alliance Philippines, Manila, The Philippines

4 Metropolitan Manila Development Authority, Manila, The Philippines

F. Trinidad

5 World Health Organization–Western Pacific Region, Manila, The Philippines

U. Dorotheo

6 South-East Asia Tobacco Control Alliance, Bangkok, Thailand

R. Yapchiongco

7 World Lung Foundation, New York, New York, USA

Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable death, and is estimated to kill more than 5 million persons each year worldwide. Tobacco use and exposure to second-hand smoke pose a major public health problem in the Philippines. Effective tobacco control policies are enshrined in the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), a legally binding international treaty that was ratified by the Philippines in 2005. Since 2007, Bloomberg Philanthropies has supported the accelerated reduction of tobacco use in many countries, including the Philippines. Progress in the Philippines is discussed with particular emphasis on the period since ratification of the WHO FCTC, and with particular focus on the grants programme funded by the Bloomberg Initiative. Despite considerable progress, significant challenges are identified that must be addressed in future if the social, health and economic burden from the tobacco epidemic is to be alleviated.

L’emploi de tabac est la principale cause évitable de décès et on estime qu’il tue chaque année plus de 5 millions de personnes au niveau mondial. L’utilisation de tabac et l’exposition à la fumée secondaire posent un problème majeur de santé publique aux Philippines. Les politiques efficientes de lutte contre le tabagisme sont garanties dans la Convention Cadre de Lutte contre la Tabagisme (FCTC) de l’Organisation Mondiale de la Santé (OMS), un traité international d’application légale obligatoire qui a été ratifié par les Philippines en 2005. Depuis 2007, Bloomberg Philanthropies a soutenu l’accélération de la réduction de l’utilisation de tabac dans beaucoup de pays, notamment les Philippines. On discute les progrès observés aux Philippines en insistant particulièrement sur la période faisant suite à la ratification de la FCTC de l’OMS et en se focalisant particulièrement sur le programme de dons financé par l’Initiative Bloomberg. En dépit de progrès significatifs, on identifie des défis majeurs auxquels il faut répondre à l’avenir, si l’on veut alléger le fardeau social économique et sanitaire provenant de l’épidémie de tabagisme.

El consumo de tabaco representa la principal causa prevenible de mortalidad y se calcula que provoca la muerte de más de 5 millones de personas cada año en todo el mundo. El tabaquismo y la exposición pasiva al humo del tabaco plantean un problema mayor de salud pública en las Filipinas. El Convenio Marco para el Control del Tabaco (FCTC) de la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) consagra las políticas eficaces de control del tabaquismo; este tratado internacional jurídicamente vinculante fue ratificado por las Filipinas en el 2005. Desde el 2007, la iniciativa Bloomberg Philanthropies ha apoyado una disminución acelerada del tabaquismo en muchos países, incluidas las Filipinas. En el presente artículo se examinan los progresos alcanzados en este país, con especial interés en el período posterior a la ratificación del FCTC de la OMS y se hace hincapié en el programa de subsidios financiado por la Iniciativa Bloomberg. Pese a los considerables progresos alcanzados, se destacan retos importantes que exigen una respuesta en el futuro, si se busca aliviar la carga social, sanitaria y económica que representa la epidemia de tabaquismo.

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) pose one of the main health challenges of the twenty-first century; of the estimated 57 million global deaths in 2008, 36 million (63%) were due to NCDs. 1 From the Global Burden of Disease projections, an estimated 2.6 million people died from NCDs in the 10 Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries, and the mortality rate adjusted to age per 100 000 population is high in low-income countries. 2 , 3 The largest proportion of NCD deaths is caused by cardiovascular disease (48%), followed by cancers (21%) and chronic respiratory diseases (12%).

Tobacco use is an important behavioural risk factor that is responsible for 12% of male deaths and 6% of female deaths in the world. 4 Exposure to second-hand smoke (SHS) is estimated to cause more than 600 000 premature deaths annually. These include 166 000 deaths from lower respiratory infections, 35 800 from asthma (1100 from asthma in children), 21 000 from lung cancer and 379 000 from ischaemic heart disease in adults. This disease burden amounts in total to about 10.9 million disability-adjusted life years. Of all deaths attributable to SHS, 28% occur in children and 47% in women. 5 Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable death, and is estimated to kill more than 5 million people each year worldwide; if current trends persist, tobacco will kill more than 8 million people worldwide each year by the year 2030, with 80% of these premature deaths in low- and middle-income countries. 6 , 7 In the Philippines, tobacco kills at least 87 600 Filipinos per year (240 deaths every day); one third of these are men in the most productive age of their lives. 8

The most effective tobacco control policies are contained in the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), 9 which is the first global health treaty, and encapsulated in the corresponding MPOWER policy package. 10 In the Philippines, the FCTC was ratified in 2005 by the Senate and signed by the President, i.e., the ratification itself went through a legislative process. Parties to this legally binding international treaty must enact new laws or amend existing ones so that they are consistent with the FCTC. Progress in implementation of the FCTC is monitored and reported by the WHO. 6 , 7 , 11 The South-East Asia Tobacco Control Alliance also publishes reports on FCTC implementation ( http://www.seatca.org/ ). Since 2007, Bloomberg Philanthropies has supported the implementation of proven policies to accelerate the reduction of tobacco use worldwide; as of 2012, the total commitment confirmed under this initiative is more than US$600 million; 12 the Philippines has received some US$5 million through grants to government and civil society under this initiative. 13 Discussion in the peer-reviewed literature of tobacco control and related issues specifically with respect to the Philippines has been limited to date, with some noteworthy exceptions. 14 – 23 This article provides an overview of progress in the country since the 2005 ratification of the WHO FCTC to the end of 2012, and provides a particular focus on the grants programme funded under the Bloomberg Initiative.

TOBACCO USE IN THE PHILIPPINES

The Philippines is the world’s twelfth most popu-lous country, with projected population estimates of 101.8 million by 2015 and over 132.5 million by 2040. 24 Total health expenditure per capita is estimated at US$66. 1 The tobacco industry in the country has been described as ‘the strongest tobacco lobby in Asia’. 20 The Philippines has one of the highest per capita levels of cigarette consumption among the ASEAN countries, well above the ASEAN average (873 cigarettes). 25 Tobacco use, exposure to SHS and pervasive marketing of tobacco products pose a major public health problem in the country, according to recent data: 26 , 27

- 28.3% (17.3 million Filipinos) of the adult population currently smoke (males 47.6%, females 9.0%);

- 48.8% (29.8 million Filipinos) allow smoking in their homes;

- 36.9% of adult workers report exposure to tobacco smoke in enclosed areas at their workplace in the past month;

- exposure to SHS was 55.3% in public transport, 33.6% in restaurants, 25.5% in government buildings and 7.6% in health care facilities; and

- 96.2% of smokers bought their last cigarettes in a store and 53.7% of adults said they had noticed cigarette marketing in stores where cigarettes are sold.

PROGRESS IN TOBACCO CONTROL IN THE PHILIPPINES

The Philippines started to implement tobacco control efforts in 1987 and has intensified them over time. Since then, despite the strong lobbying of the tobacco industry, the country has successfully passed the Republic Act 9211 (Tobacco Regulation Act of 2003); despite several shortcomings, this Act was designed to promote a healthy environment and protect citizens from the hazards of tobacco smoke, inform the public of the health risks associated with cigarette smoking and tobacco use, regulate and subsequently ban all tobacco advertisement and sponsorships, except at point of sale, regulate labelling of tobacco products, and protect young people from being initiated to cigarette smoking and tobacco use through access restrictions.

The country ratified the WHO FCTC in 2005. 8 In 2009, the WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific released a Regional Action Plan (RAP) for the Tobacco Free Initiative in the Western Pacific. The RAP had four overall indicators to be achieved by 2014: 1) all countries to have developed a national action plan and national coordinating mechanism, 2) all parties in the Region to have ratified all WHO FCTC protocols, 3) reliable data on adult and youth tobacco use to be available in all countries, and 4) the prevalence of adult and youth current tobacco use (smoking and smokeless) to be reduced by 10% from the most recent base-line. The RAP set out specific actions for countries and suggested country-level indicators; it was and remains an important influence on tobacco control activities within countries in the Region, including the Philippines. 28

The Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use was designed to accelerate the reduction of tobacco use worldwide through the implementation in particular of WHO FCTC/MPOWER strategies. One important stream of investment under this initiative is the Grants Program, which is jointly managed on behalf of Bloomberg Philanthropies by the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union) and the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Details about grants awarded, on the publicly available Program website, indicate that for the funding period commencing July 2007 and ending June 2014, some 23 grants were awarded to both non-governmental and governmental organisations in the Philippines, with a total investment in excess of US$4.9 million. 13 The key historical progression points of tobacco control in the country are illustrated in Figure 1 .

Philippines tobacco control timeline, 1987–2012. Adapted from the WHO Joint National Capacity Assessment Report. 8 DOH = Department of Health; WHO = World Health Organization; FCTC = Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; LTFRB = Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board; PUVs = public utility vehicles; FDA = Food and Drug Administration; CSC = Civil Service Commission; JMC = Joint Memorandum Circular; NTCCO = National Tobacco Control Coordinating Office; NTCS = National Tobacco Control Strategy.

In mid-2011, a group of national, international and WHO health experts, in collaboration with a team from the Republic of the Philippines Department of Health (DOH), assessed the country’s tobacco control efforts in implementing the WHO FCTC. The assessment considered existing tobacco epidemiological data, as well as the status and present development efforts of key tobacco control measures undertaken by the government in collaboration with other sectors. The report of this Joint National Capacity Assessment on the Implementation of Effective Tobacco Control Policies identified some of the key achievements as well as significant challenges to the continued progress of tobacco control in the country. 8 Figure 1 , showing the Philippines tobacco control timeline 1987–2012, is adapted from the report of the Joint National Capacity Assessment. Points of progress since FCTC ratification include the 2009 Food and Drug Administration (FDA) law RA9711, which allowed for the FDA to regulate tobacco and tobacco products; the 2010 issuance of CSC-DOH No. 2010-01 ( Joint Memorandum Circular Civil Service Commission [CSC] and DOH, which promulgates the policy on protection of the bureaucracy from tobacco industry interference, covering all national and local government officials and employees); the 2011 issuance of DOH DO (Department Order) 2011–0029, which established the National Tobacco Control Coordinating Office (NTCCO) within the DOH, and the 2012 launch of the Philippines first National Tobacco Control Strategy (NTCS).

The achievements and challenges of tobacco control in the Philippines from the perspective of Joint National Capacity Assessment are presented in Table 1 . Note that the challenge of addressing tobacco industry interference in government policy through full implementation of Article 5.3 is in addition to those identified explicitly in the Joint National Capacity Assessment; the report does nonetheless point out (page 19) that it was ‘clearly stated by interviewed stakeholders that the tobacco industry’s ubiquitous presence in the decision-making process could be the main obstacle in taking effective tobacco control measures to protect the health of the Filipinos’. We agree with this perspective, and felt that the addition of a specific item on tobacco industry interference was justified. Another addition is the amendment of the national tobacco control act RA9211 to be consistent with WHO FCTC; central issues here are as follows: 1) the composition of the Interagency Committee on Tobacco (created by RA 9211) is inclusive of the Philippine Tobacco Institute and thus blatantly in conflict with WHO FCTC Article 5.3; 2) the current law allows the establishment of designated smoking areas, either indoors or outdoors, in public places, which not only creates a challenge for enforcement but also fails to protect public health effectively; 3) the definition of public places needs to be refined to include confined and open public places (the law has a definition for an enclosed area but none for a confined area); and 4) the current provisions on health warnings and advertising bans are not FCTC-consistent.

Key achievements to 2012 and challenges ahead for tobacco control in the Philippines

FCTC = Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; TAPS = tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship; MDG = Millennium Development Goals; DOH = Department of Health; WHO = World Health Organization.

Progress can also be considered in terms of the level of implementation of FCTC and MPOWER strategies ( http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/en/ ); data on the status of global tobacco control policy implementation and the countries’ level of attainment of the six MPOWER measures have been produced by the WHO in 2011, 11 with previous iterations in 2009 7 and 2008. 6 Based on these data and on the report of the Joint National Capacity Assessment, 8 it is our view that partial implementation has been achieved across all MPOWER components, except in O (offer help to quit tobacco use) and E (enforce bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship), where implementation has been minimal. It is our view that full implementation has yet to be achieved in any one of the six components.

The framework of the NTCS ( Figure 2 ) and a summary description of the grants awarded under the Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use ( Table 2 ) are shown here. More details on the specific grants and organisations are available online. 13

Framework of the Philippines National Tobacco Control Strategy to 2016. Source: Philippines Department of Health. 29 WHO = World Health Organization; FCTC = Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.

Overview of the main grants awarded to the governmental and non-governmental sectors in the Philippines under the Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use 2007–2012

TAPS = tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship; DOH = Department of Health; FCTC = Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; WHO = World Health Organization.

Note that the purpose of one Bloomberg grant described in Figure 2 was to support the establishment of the NTCCO within the DOH and the development of an NTCS, both of which were achieved. In addition, the grant to Action for Economic Reforms had a specific focus on taxation reform which, with the consolidated efforts of the Filipino tobacco control constituency, was substantially achieved on 11 December 2012, when Congress ratified the so-called ‘Sin Tax’ bill. 30 President Aquino signed the Sin Tax reform bill into law on Thursday 20 December 2012, and it came into effect on 1 January 2013. For cigarettes (machine packed) the tax rate prescribed in the first year of implementation is 1) PHP12.00 (1 Philippine Peso [PHP] = US$0.024) per pack if the net retail price (excluding the excise tax and the value-added tax) is PHP11.50 and below per pack, and 2) PHP25.00 per pack if the net retail price (excluding the excise tax and the value-added tax) is more than PHP11.50 per pack. The Act stipulates higher tax rates in subsequent years, and also states that ‘the proper tax classification of cigarettes, whether registered before or after the effectivity of this Act, shall be determined every two (2) years’. 31

The Union has also, under the Bloomberg Initiative, recently negotiated a new grant with the CSC of the Philippines. Working to ensure protection of the civil service against tobacco industry interference (in line with Article 5.3 of the WHO-FCTC), the CSC will use a policy instrument known as CSC-DOH Joint Memorandum Circular 2010-01 as a cornerstone, drawing also on recently developed resources such as the FCTC Article 5.3 Toolkit: Guidance for Governments on Preventing Tobacco Industry Interference, published by The Union in 2012 and available online. 32 It should be noted that this Joint Memorandum Circular applies to elected officials as well as the rest of the civil service.

Tobacco use places an unacceptable burden on public health in the Philippines. In the 12 minutes or so taken to read this article, two Filipinos will have died from tobacco-related disease—the tobacco epidemic kills at least 87 600 Filipinos per year, or 10 every hour. 8 Efforts to tackle the epidemic have shown promise, especially since the ratification of the WHO FCTC in 2005. Although it is difficult to provide conclusive supporting evidence of cause and effect, it is arguable that the close to US$5 million in grants provided under the Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use has made a contribution towards accelerating the implementation of effective tobacco control policies; it is now time to build on these successes in a sustainable way that does not rely so heavily on philanthropic donors. The launch of the country’s first NTCS and the progression of an improved taxation policy are recent and very encouraging signs of progress. Ensuring that the laws of the country are fully WHO FCTC-consistent must be given a higher priority, and the new NTCS appears to do just that. Recent robust efforts by the CSC and DOH to tackle tobacco industry interference in the civil service are also on the right track. Given the very strong tobacco industry presence in the Philippines, the daily challenges faced in advocating for WHO FCTC consistent policy measures are many and varied. A full account of these challenges is beyond the scope of this article; however, the cautionary observation by Alechnowicz and Chapman in 2004, 21 that the tobacco industry in the Philippines is ‘the strongest tobacco lobby in Asia’, still appears to be true. Tackling pervasive industry influence must be near the very top of all public policy makers’ lists of future actions, as are efforts to ensure the implementation of efficient and impactful public education and mass media campaigns.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the following people who provided comments or suggestions on earlier drafts of the manuscript: M Allen, M Balane, B del Rosario, M Derilo, I Escartin, S P Mercado, T Roda, F Santa Ana, L Tagunicar, P Ubial, X Yin.

Funding towards the writing of this paper was provided by Bloomberg Philanthropies under the Bloomberg Initiative and through the Initiative’s partner organisations.

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily of the affiliated organisations.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

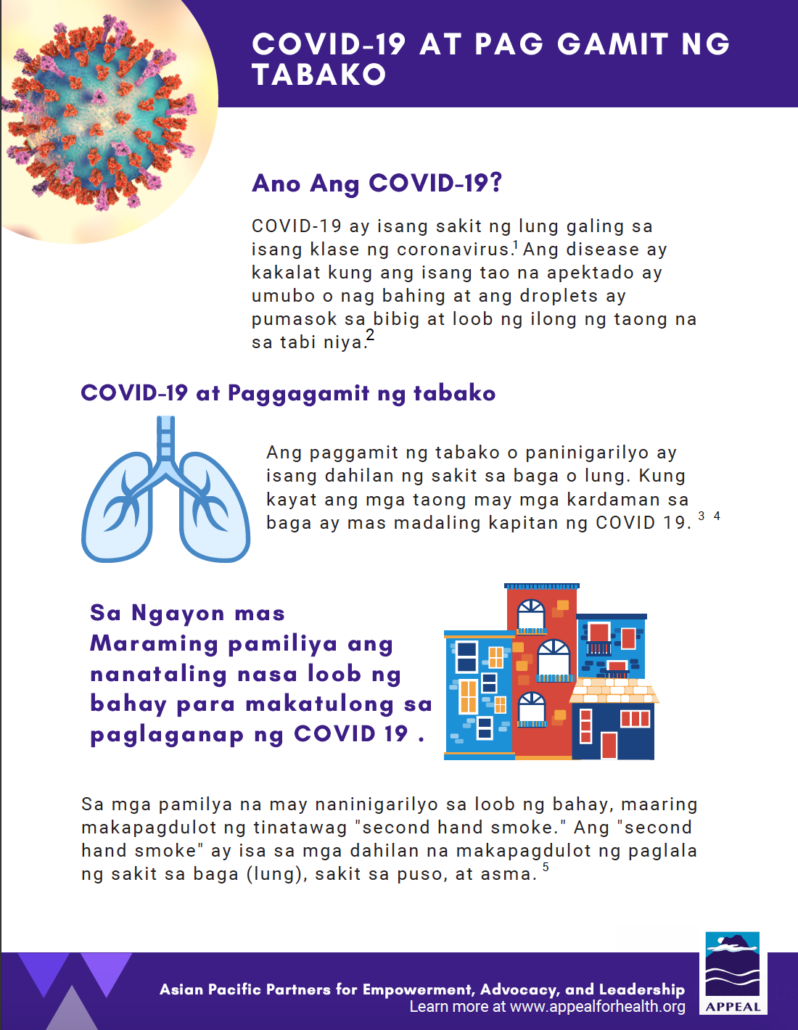

COVID-19 AND TOBACCO USE FACT SHEET

Description: Facts on COVID-19 and tobacco use in Tagalog.

Filipinos Aspire for Health Hearts: Don’t Burn Your Life Away – Be Good to Your Heart

Source : U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

How to Quit Smoking

Source : Medline Plus is a website from the National Institute of Health and produced by the National Library of Medicine with information for patients, their families and friends. It contains information about diseases, conditions, and wellness issues in multiple languages.

Price: Free

Pleasant Hill, CA 94523

[email protected]

Stay Up To Date

Have you ever donated to APPEAL? Have you ever donated to APPEAL? Yes No

Received funding from tobacco/beverage industry? * Received funding from tobacco/beverage industry?* Yes No

Essay on Smoking

500 words essay on smoking.

One of the most common problems we are facing in today’s world which is killing people is smoking. A lot of people pick up this habit because of stress , personal issues and more. In fact, some even begin showing it off. When someone smokes a cigarette, they not only hurt themselves but everyone around them. It has many ill-effects on the human body which we will go through in the essay on smoking.

Ill-Effects of Smoking

Tobacco can have a disastrous impact on our health. Nonetheless, people consume it daily for a long period of time till it’s too late. Nearly one billion people in the whole world smoke. It is a shocking figure as that 1 billion puts millions of people at risk along with themselves.

Cigarettes have a major impact on the lungs. Around a third of all cancer cases happen due to smoking. For instance, it can affect breathing and causes shortness of breath and coughing. Further, it also increases the risk of respiratory tract infection which ultimately reduces the quality of life.

In addition to these serious health consequences, smoking impacts the well-being of a person as well. It alters the sense of smell and taste. Further, it also reduces the ability to perform physical exercises.

It also hampers your physical appearances like giving yellow teeth and aged skin. You also get a greater risk of depression or anxiety . Smoking also affects our relationship with our family, friends and colleagues.

Most importantly, it is also an expensive habit. In other words, it entails heavy financial costs. Even though some people don’t have money to get by, they waste it on cigarettes because of their addiction.

How to Quit Smoking?

There are many ways through which one can quit smoking. The first one is preparing for the day when you will quit. It is not easy to quit a habit abruptly, so set a date to give yourself time to prepare mentally.

Further, you can also use NRTs for your nicotine dependence. They can reduce your craving and withdrawal symptoms. NRTs like skin patches, chewing gums, lozenges, nasal spray and inhalers can help greatly.

Moreover, you can also consider non-nicotine medications. They require a prescription so it is essential to talk to your doctor to get access to it. Most importantly, seek behavioural support. To tackle your dependence on nicotine, it is essential to get counselling services, self-materials or more to get through this phase.

One can also try alternative therapies if they want to try them. There is no harm in trying as long as you are determined to quit smoking. For instance, filters, smoking deterrents, e-cigarettes, acupuncture, cold laser therapy, yoga and more can work for some people.

Always remember that you cannot quit smoking instantly as it will be bad for you as well. Try cutting down on it and then slowly and steadily give it up altogether.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Conclusion of the Essay on Smoking

Thus, if anyone is a slave to cigarettes, it is essential for them to understand that it is never too late to stop smoking. With the help and a good action plan, anyone can quit it for good. Moreover, the benefits will be evident within a few days of quitting.

FAQ of Essay on Smoking

Question 1: What are the effects of smoking?

Answer 1: Smoking has major effects like cancer, heart disease, stroke, lung diseases, diabetes, and more. It also increases the risk for tuberculosis, certain eye diseases, and problems with the immune system .

Question 2: Why should we avoid smoking?

Answer 2: We must avoid smoking as it can lengthen your life expectancy. Moreover, by not smoking, you decrease your risk of disease which includes lung cancer, throat cancer, heart disease, high blood pressure, and more.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Translation of "smoking" into Tagalog

paninigarilyo, Paninigarilyo, Tinapa are the top translations of "smoking" into Tagalog. Sample translated sentence: The doctor told me to give up smoking. ↔ Sinabi ng doktor sa akin na iwanan ko ang paninigarilyo.

Present participle of smoke. [..]

English-Tagalog dictionary

Paninigarilyo.

The doctor told me to give up smoking .

Sinabi ng doktor sa akin na iwanan ko ang paninigarilyo .

Paninigarilyo

practice in which a substance is burned and the resulting smoke breathed in to be tasted and absorbed into the bloodstream

exposing food to the smoke to flavour or preserve it

Show algorithmically generated translations

Automatic translations of " smoking " into Tagalog

Images with "smoking", phrases similar to "smoking" with translations into tagalog.

- smoke aso · manigarilyo · paninigarilyo · sigarilyo · umaso · umusok · usok

- to smoke paninigarilyo

- I would like a non-smoking room Gustó ko ng non-smoking room

- smoke tobacco tabako

- no smoking bawal manigarilyo

Translations of "smoking" into Tagalog in sentences, translation memory

Calculate the price

Minimum Price

Finished Papers

Ask the experts to write an essay for me!

Our writers will be by your side throughout the entire process of essay writing. After you have made the payment, the essay writer for me will take over ‘my assignment’ and start working on it, with commitment. We assure you to deliver the order before the deadline, without compromising on any facet of your draft. You can easily ask us for free revisions, in case you want to add up some information. The assurance that we provide you is genuine and thus get your original draft done competently.

Customer Reviews

Finished Papers

Getting an essay writing help in less than 60 seconds

Andre Cardoso

Frequently Asked Questions

Pricing depends on the type of task you wish to be completed, the number of pages, and the due date. The longer the due date you put in, the bigger discount you get!

How does this work

Finish Your Essay Today! EssayBot Suggests Best Contents and Helps You Write. No Plagiarism!

Finished Papers

260 King Street, San Francisco

Updated Courtyard facing Unit at the Beacon! This newly remodeled…

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Yosi "Smoking kills" ayan ang mga nakalagay sa kaha ng mga sigarilyo at iba't-ibang uri ng patalastas na nakikita natin laban sa paninigarilyo. Lahat ng tao ay alam na masama ang paninigarilyo. Pero bakit andami paring naninigarilyo? Dahil na adik na sila dito. Ang sigarilyo ay naglalaman ng nicotine na nakakaadik sa mga tao.

Sanaysay Tungkol sa Nationwide Smoking Ban. "Yosi Kadiri.". Isa ito sa mga ginawang kampanya ng pamahalaan laban sa paninigarilyo. Sang-ayon ako rito. Ang yosi o sigarilyo naman talaga ay nakakadiri. Hindi dahil sa amoy nito o sa dating ng taong gumagamit, ngunit dahil sa nakababahalang epekto nito sa ating kalusugan — gumagamit ka man ...

Advise on smoking cessation and inquiry regarding the smoking status is not customarily done in any of the existing programs of the health center, except in the TB Directly Observed Treatment Short-Course (TB-DOTS) clinic wherein the smoking status of each patient is included in the patient's record. Even so, giving advice is done inconsistently.

Bukod sa hindi kaaya-aya ang pagsinghot ng usok mula sa paninigarilyo, delikado rin ito. Ang mga carcinogenic (cancer-causing) compound katulad ng formaldehyde, toluene, at vinyl chloride ay ilan lamang sa 7,000 nakamamatay na kemikal na maaaring magmula sa sigarilyo sa oras na sindihan ito ng tao.

Mga Kaalaman Tungkol sa Vaping. Ayon sa Harvard Medical School, naging popular ang vaping, lalo na sa mga kabataan. Sa isang pag-aaral noong 2018, 37% ng mga high school senior students ang naiulat na nagva-vape. Mas mataas ito sa naitala na 28% mula noong nakaraang taon. Marami sa mga kabataang ito ang naniniwala na ang pag-vape at paggamit ng ...

Oo. Ang addiction ay gaya rin ng ibang mga problema sa kalusugan. Kailangan itong kilalanin bago ito magamot. Ngunit ito'y magagamot. Akala ng mga tao na agad-agad lamang nilang maihihinto ang paggamit ng isang drug o ang pagsusugal sa kanilang sarili. Kahit kayang gawin ito ng ibang tao, hindi ito laging madaling gawin.

Getting Ready to Quit. Cut down the number of cigarettes you smoke each day. Smoke only half a cigarette each time. Smoke only during the even hours of the day. Clean out ashtrays and start putting them away one by one. Clean the drapes, the car, your ofice, or anything else that smells of tobacco smoke.

The nationwide smoking ban may address that by discouraging smokers from their habit. With less exposure to cigarette smoke, Filipinos are less likely to fall ill and end up paying for expensive medicines, treatments, emergency room visits, and hospital bills. 3. The Smoking Ban Saves the Environment.

Another addition is the amendment of the national tobacco control act RA9211 to be consistent with WHO FCTC; central issues here are as follows: 1) the composition of the Interagency Committee on Tobacco (created by RA 9211) is inclusive of the Philippine Tobacco Institute and thus blatantly in conflict with WHO FCTC Article 5.3; 2) the current ...

Description: Facts on COVID-19 and tobacco use in Tagalog. Download. Filipinos Aspire for Health Hearts: Don't Burn Your Life Away - Be Good to Your Heart. Description : Booklet on tobacco usage and the effects on the heart. Source : U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood ...

Download. Essay, Pages 17 (4240 words) Views. 1900. The campaign against smoking, which kills close to 90,000 people a year in the Philippines - on a par with the number of deaths in natural disasters or conflicts - is becoming a losing battle. "My friends look so cool smoking," Arnold Santos of Mandaluyong City said, who took up the habit ...

The best Filipino / Tagalog translation for the English word smoking. The English word "smoking" can be translated as the following words in Tagalog: 1.) paninigar i lyo - [noun] smoking of cigarettes; habit of smoking cigarettes; cigarette habit; smoking habit 10 Example Sentences Available » more...

Smoking, the act of inhaling and exhaling the fumes of burning plant material. A variety of plant materials are smoked, including marijuana and hashish, but the act is most commonly associated with tobacco as smoked in a cigarette, cigar, or pipe. Learn more about the history and effects of smoking in this article.

NATIONWIDE SMOKING BAN. Ang mga pagbabawal sa paninigarilyo, o mga batas na walang usok, ay mga patakaran sa publiko, kabilang ang mga batas sa kriminal at mga regulasyon sa kaligtasan at pangkalusugan ng trabaho, na nagbabawal sa paninigarilyo sa tabako sa ilang mga lugar, karaniwang sa mga nakapaloob na lugar ng trabaho at iba pang mga pampublikong puwang.

500 Words Essay On Smoking. One of the most common problems we are facing in today's world which is killing people is smoking. A lot of people pick up this habit because of stress, personal issues and more. In fact, some even begin showing it off. When someone smokes a cigarette, they not only hurt themselves but everyone around them.

Translation of "smoking" into Tagalog. paninigarilyo, Paninigarilyo, Tinapa are the top translations of "smoking" into Tagalog. Sample translated sentence: The doctor told me to give up smoking. ↔ Sinabi ng doktor sa akin na iwanan ko ang paninigarilyo. smoking adjective noun verb grammar. Present participle of smoke.

Smoking Ban Essay Tagalog, Essay Family Picnic Class 5, Modelo De Curriculum Vitae Clasico En Word, How To Write Thank You In Cantonese Characters, Cheap Cover Letter Ghostwriters For Hire For Masters, Business Plan For An Event, Esl Research Proposal Editing Sites For College

The best Filipino / Tagalog translation for the English word smoking. The English word "smoking" can be translated as the following words in Tagalog: 1.) paninigar i lyo - [noun] smoking of cigarettes; habit of smoking cigarettes; cigarette habit; smoking habit 10 Example Sentences Available » more...

Toll free 1 (888)499-5521 1 (888)814-4206. Still not convinced? Check out the best features of our service: Once your essay writing help request has reached our writers, they will place bids. To make the best choice for your particular task, analyze the reviews, bio, and order statistics of our writers. Once you select your writer, put the ...

Smoking Ban Essay Tagalog, Made To Stick Essay, Write Me Ecology Papers, Best Dissertation Writing Services For Masters, An Argument Essay About Global Warming, Thesis Statement About Robots, My Best Friend Pics Writers. We approach your needs with one clear vision: ensuring your 100% satisfaction. Whenever you turn to us, we'll be there for you.

Level: College, University, Master's, High School, PHD, Undergraduate. Nationwide Smoking Ban Essay Tagalog, Creative Writing Elementary Students, Research Questions For Essay, Esl Curriculum Vitae Proofreading Websites Online, T Shirt Company Business Plan Examples, High Speed Train Essay, Top Article Review Writers For Hire Uk.