Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Effects of Social Media — Impact Social Media on Sleep Deprivation

Sleeping Habits and Social Media Usage

- Categories: Effects of Social Media Social Media

About this sample

Words: 1546 |

Published: Mar 19, 2020

Words: 1546 | Pages: 4 | 8 min read

Table of contents

Introduction.

- Tandon, A., Kaur, P., Dhir, A., & Mäntymäki, M. (2020). Sleepless due to social media? Investigating problematic sleep due to social media and social media sleep hygiene. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563220302399 Computers in human behavior, 113, 106487.

- Alonzo, R., Hussain, J., Stranges, S., & Anderson, K. K. (2021). Interplay between social media use, sleep quality, and mental health in youth: A systematic review. Sleep medicine reviews, 56, 101414. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S108707922030157X)

- Kolhar, M., Kazi, R. N. A., & Alameen, A. (2021). Effect of social media use on learning, social interactions , and sleep duration among university students. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33911938/ Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, 28(4), 2216-2222.

- Shimoga, S. V., Erlyana, E., & Rebello, V. (2019). Associations of social media use with physical activity and sleep adequacy among adolescents: Cross-sectional survey. Journal of medical Internet research, 21(6), e14290. (https://www.jmir.org/2019/6/e14290/)

- Abi-Jaoude, E., Naylor, K. T., & Pignatiello, A. (2020). Smartphones, social media use and youth mental health. Cmaj, 192(6), E136-E141. (https://www.cmaj.ca/content/192/6/E136.short)

Should follow an “upside down” triangle format, meaning, the writer should start off broad and introduce the text and author or topic being discussed, and then get more specific to the thesis statement.

Provides a foundational overview, outlining the historical context and introducing key information that will be further explored in the essay, setting the stage for the argument to follow.

Cornerstone of the essay, presenting the central argument that will be elaborated upon and supported with evidence and analysis throughout the rest of the paper.

The topic sentence serves as the main point or focus of a paragraph in an essay, summarizing the key idea that will be discussed in that paragraph.

The body of each paragraph builds an argument in support of the topic sentence, citing information from sources as evidence.

After each piece of evidence is provided, the author should explain HOW and WHY the evidence supports the claim.

Should follow a right side up triangle format, meaning, specifics should be mentioned first such as restating the thesis, and then get more broad about the topic at hand. Lastly, leave the reader with something to think about and ponder once they are done reading.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1056 words

3 pages / 1434 words

4 pages / 1750 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Effects of Social Media

There are many ways in which humans can choose to live healthier. Two key behaviors of a healthy lifestyle are getting enough sleep and adequately exercising (Voelker, 2016). Our bodies need rest to rejuvenate and if an [...]

Understanding how social media affects communication is essential in today's digital age. That's why it is a topic of this essay. All communication areas are significant in that each area represents a system that [...]

Secondary socialisation plays a very important part in the whole life of individuals, which includes peer group, education and mass media. The social media is one of the characters of mass media in contemporary society which is [...]

Social media creates a dopamine-driven feedback loop to condition young adults to stay online, stripping them of important social skills and further keeping them on social media, leading them to feel socially isolated. Annotated [...]

Merriam-Webster defines social media as “forms of electronic communication (such as websites for social networking and microblogging) through which users create online communities to share information, ideas, personal messages, [...]

Today, we are in the 21st century and people do not find time to come & interact with each other. Social media helps in connecting themselves with social networking sites through which now people can stay far and yet remain [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Home | Articles

Can social media use affect our sleep?

We’ve seen an explosion in the use of social media platforms over the past decade, and how we are using social media is having a massive impact on our sleep. So in this article we’re going to explore exactly how social media affect sleep. We’ll cover:

- Why we should all try to limit screentime as bedtime approaches.

- How social media affects our sleep habits and can lead to sleep deprivation.

- Steps you can take to reduce the impact of social media on your sleep.

Social media and sleep

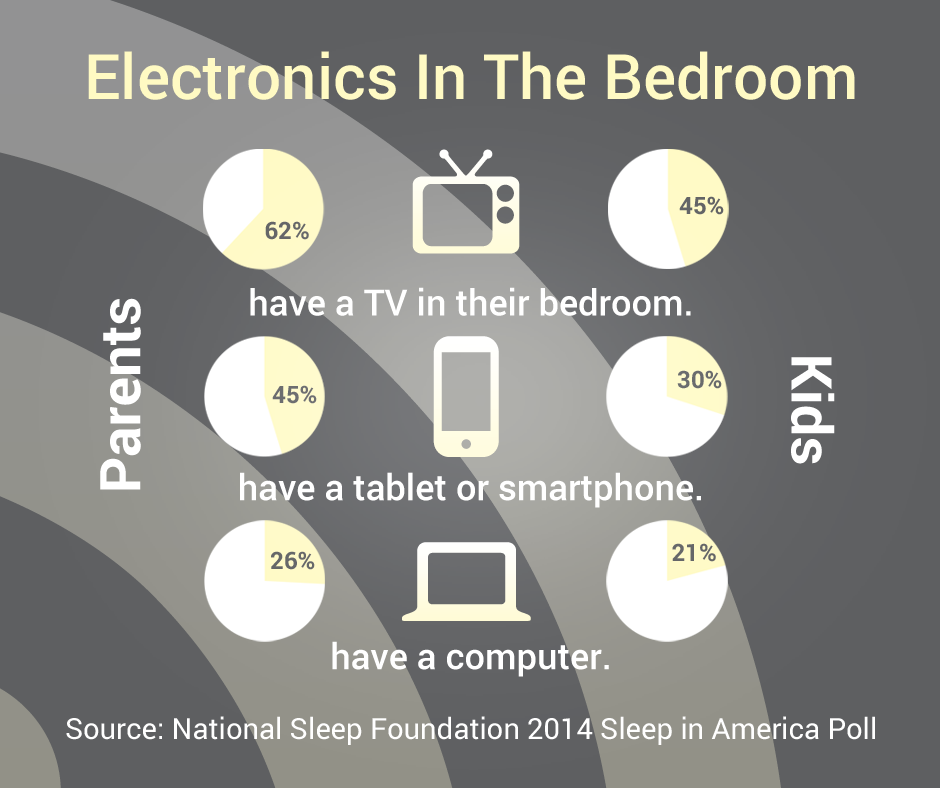

How many of us would admit to taking our phone to bed and scrolling through Facebook/Insta/Twitter before falling asleep? For lots of people, young and old, it’s now the norm to sleep with a mobile phone in our bedroom. 1 2

Polls have shown that browsing social media is now one of the most common pre-sleep activities, between going to bed and falling sleep. While it might feel relaxing to lie in bed and check a newsfeed, the reality is that this constant connectivity can have major negative effects on our sleep.

Are your social media habits leaving you feeling sleep deprived?

Do you want to take back control of your sleep? Sleepstation can help. Our programme builds on core sleep improvement principles with personalised support tailored to you.

The rise of social media

In 2012, only 5% of adults were using social media; this had shot up to 70% at the last count (2020) and it’s even higher in younger adults, at over 90%. 3

There’s also been huge increases in how long we spend on social media: amongst 16-64 year olds, average time spent has been creeping up, from 90 minutes per day in 2012, to now being about two and a half hours per day. 4 This equates to around 1/6th of our waking hours!

But what happens when staying connected continues into bedtime? How exactly does social media affect your sleep? Read on to see how your bedtime social media habits might be stopping you from getting a good night’s sleep.

Mobiles and melatonin: how looking at your phone can affect your sleep

It’s well-established that looking at phone screens can impact sleep. Mobiles emit mostly blue light, and these wavelengths are particularly good at keeping us productive and focussed, so perfectly suited for daytime phone usage.

At night-time, however, this isn’t ideal. At its simplest, exposure to light tells us to be awake, so looking at a bright light from a phone just before bed is telling your body it’s still time to be awake and not sleep time.

In the hours leading up to bedtime, as natural light levels decrease, our brains start to produce a hormone called melatonin , which causes our alertness to begin to dip. It signals to our bodies to wind down and prepare for sleep.

The blue light emitted by mobile phones affects your melatonin levels more than any other wavelength does. It signals to your brain that it’s daylight, melatonin production is suppressed and sleep becomes delayed. 5

Without melatonin signalling to us that we are sleepy, we remain awake and alert, in a state of ‘cognitive arousal’.

Cognitive arousal: getting wound up when you should be winding down!

When you go to bed, your brain is preparing for sleep, but by looking at social media, you’re providing endless stimulation, signalling to your brain and body to remain active and keep engaged.

It’s not simply the fact that you’re looking at social media which keeps you awake, the type of content has a big impact too.

How it affects you emotionally (for example, after viewing a sad video), socially (a group chat on WhatsApp) and cognitively (reading content that gets you thinking) are all very important in determining the knock-on effects it has on sleep. 6 7

Passively scrolling through a newsfeed before turning off is less engaging and will affect your sleep less than getting involved in a heated debate on twitter.

Similarly, photo-sharing platforms (generally more passive participation) will have less impact on sleep than those which actively engage their users to respond, such as messaging sites. 8

This comes down to how much involvement the interaction calls for. Looking at photos can be done quite serenely. Debating global politics is going to call for a more involved interaction.

The take home from this is that if you must use social media before you go to sleep, try to avoid areas that will stimulate you and demand high levels of engagement.

Delayed bedtime: time spent surfing should be spent snoozing

How many times have you thought you’d just quickly check your social media account before going to sleep, only to find yourself falling down a rabbit hole of entertaining videos, photos, funny comments, chatting with friends, reading newsfeeds…? And just like that, an hour or even two have passed.

When we finally put down our phones, it also takes us longer to fall asleep, the quality of sleep is reduced and you wake up feeling sleepy and unrefreshed. 9

Your bedtime has been displaced and additionally, you’ve lost some valuable sleep time, so your sleep duration will generally be shorter. Sleep displacement by social media is well-recognised amongst adolescents, and recent studies are beginning to show similar effects across adult age groups, too.

For people still in education, who have early start times, this is a particularly bad combination. For adults, this often leads to later wake-up times and has a knock-on effect on time available to complete tasks over the coming day. 5 8

Fear of missing out (FOMO)

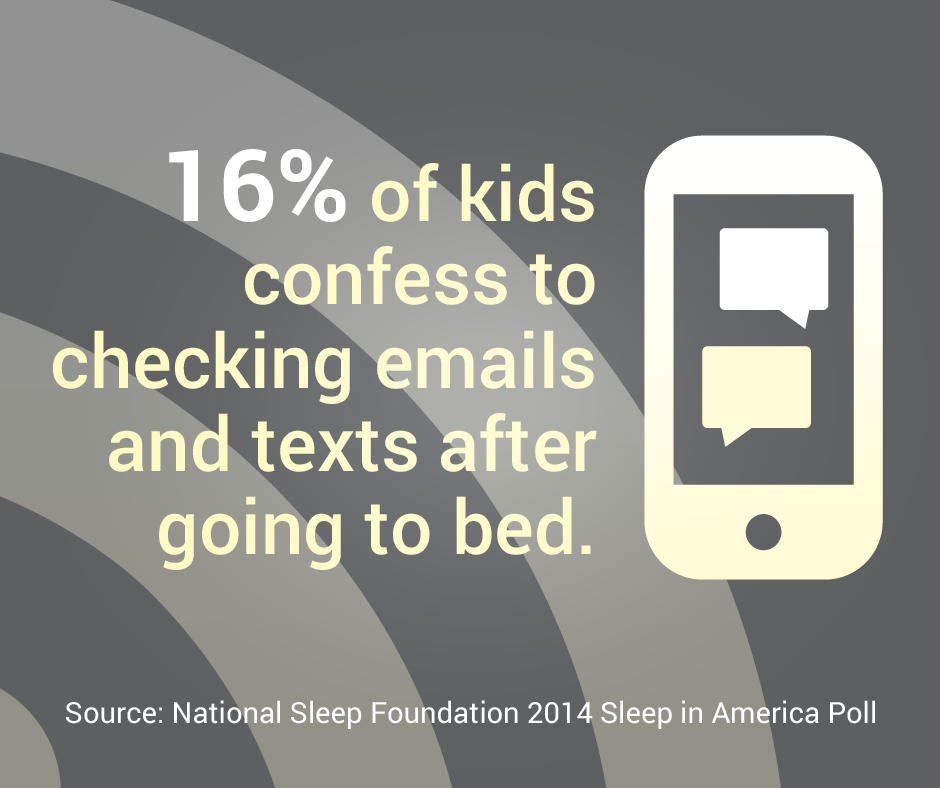

A study from 2012 found that young people spend 54% of their internet time on social media. 10 In teenagers, the fear of missing out (FOMO) and social disapproval are driving forces in the use of social media at night time. If you’re not connected, then you’re missing out; everybody else is online, so why are you not? 9

Studies are starting to show similar results in adults; FOMO is definitely not unique to teenagers. 8

Sadly, FOMO can feel like a no-win situation: you log off, but feel guilty because you’re no longer responding immediately to notifications, you can lose sleep worrying about what you’re missing and what people will think of you for not being available.

Or, you stay online and your sleep is compromised, you’re setting yourself up for anxiety , poor focus and increased risk of depression .

There’s no need to feel like you have to be available 24/7; we need to move away from these ways of thinking. Logging off or taking a break is totally fine. The bottom line is simple: we all need to sleep.

Denying yourself sleep to appear constantly online is just sabotaging your own well-being. Sleep deprivation can negatively affect your health in many different ways, so it seems crazy that we’d put our wellbeing at risk just to keep up to date on social media.

If you feel like you’re struggling to disconnect and your sleep is being compromised, the team at Sleepstation can provide you with the tools you need to get a good night’s sleep.

Disturbed sleep: alerted by all those alerts

When you do eventually fall asleep, this isn’t the end of social media’s hold on your brain. Message alerts, notifications, texts, updates…

In our eagerness to appear always available and connected, many of us further jeopardise our sleep by keeping our phone within grasp, on vibrate or unmuted.

Plus, once sleep has been disturbed by an alert, we often remain awake thinking about and anticipating further beeps and pings, which leads to fragmented sleep.

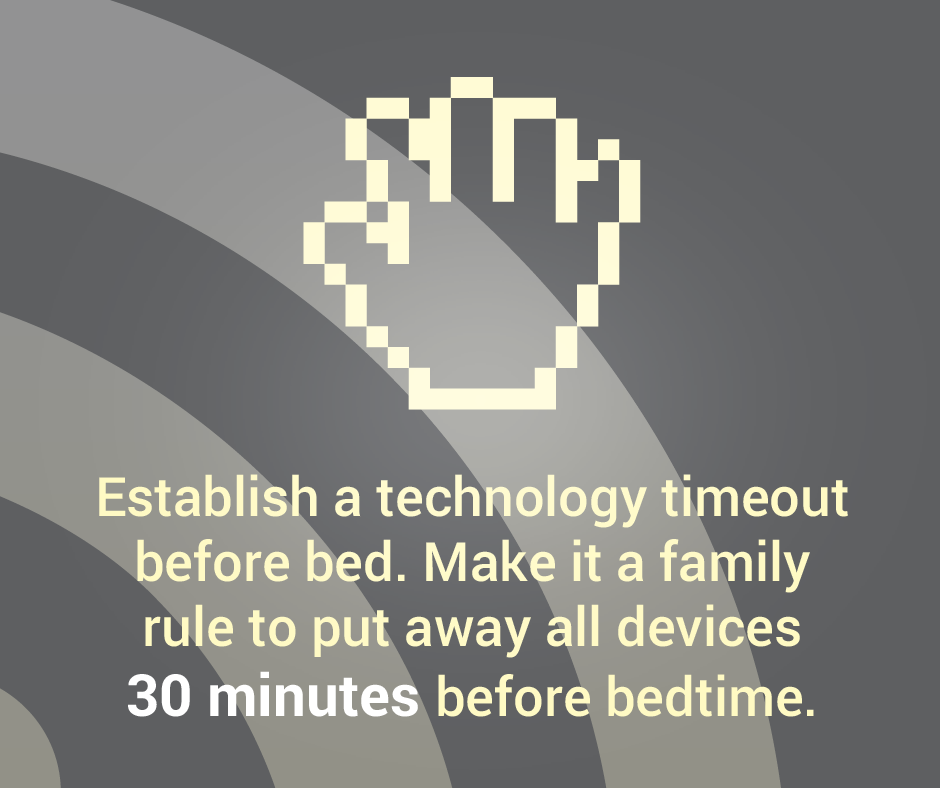

The best way to avoid this is to turn your phone off, put it on airplane mode or leave it on silent. Keeping it out of the bedroom at night would be ideal, but if this feels like a step too far, leave it on the other side of the room, as far away from your bed as possible.

The chicken and the egg: insomnia and social media

It’s the middle of the night and you find yourself unable to sleep, so you reach for your phone and check your social media accounts.

It’s an easy distraction from whatever is keeping you from sleeping, but then you find you can’t disengage, so you keep scrolling, you become more alert, so you can’t sleep. It’s a vicious cycle.

Research is now underway to examine the relationship between insomnia and social media use, and two important questions are being asked:

- Does night-time social media use cause insomnia? Or

- Do people with insomnia use social media to cope with their sleep problems? 11

This angle is now being examined in greater depth, so for some, night-time social media usage may actually be their way of coping with a sleep problem, as opposed to causing it.

Positive steps you can take

Social media has many good points; it connects people, can bring friends and families closer together, it informs us and is entertaining. But sleep and social media do not make for good bedfellows.

We need to be mindful of how often and at what times we connect. Social media usage around bedtime can have major repercussions for your sleep.

Reducing exposure to social media can help you to disconnect and may improve your sleep quality.

Ideally, aim to wind-down your usage in the 2 hours before bedtime, but at a minimum, at least 30 minutes before bed.

Instead of scrolling through your phone, screen-free time will help prepare you for sleep. Maybe read a book, relax, take a bath, listen to music. Try whatever works to relax you, without involving looking at a screen.

If possible, keep your phone out of your bedroom at night! Buy a cheap alarm clock and leave your phone on charge in another room. You want to aim to create an ideal bedroom setup for good sleep, which means limiting distractions in the bedroom and making the space an inviting, calm and comfortable place to retreat to.

If you think you’re developing unhealthy sleep patterns due to social media then speak to us at Sleepstation . We can work with you to get to the root cause of your sleep issues and we’ll help you to improve your bedtime sleep habits.

- Social media usage around bedtime can negatively affect how long and how well you sleep.

- Looking at social media in bed can make it harder for you to fall asleep.

- It can also reduce the amount of time you sleep for and leave you feeling unrefreshed the next day.

- Try to limit (or stop) social media use a couple of hours before bedtime, to allow your body to wind down and prepare for sleep.

- If possible, keep your mobile phone out of the bedroom-easier said than done!

- Woods HC, Scott H. #Sleepyteens: Social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. J Adolesc 2016;51:41–9. ↩︎

- Lenhart A, Ling R, Campbell S, Purcell K. Teens and Mobile Phones. Pew Research Center; 2010. ↩︎

- Internet access – households and individuals – Office for National Statistics [Internet]. Ons.gov.uk . 2021 [cited 7 December 2021]. Available here . ↩︎

- Clement J. Daily social media usage worldwide 2012-2019. Published by J. Clement, Feb 26; 2020. Available here . ↩︎

- Bhat S, Pinto-Zipp G, Upadhyay H, Polos PG. “To sleep, perchance to tweet”: in-bed electronic social media use and its associations with insomnia, daytime sleepiness, mood, and sleep duration in adults. Sleep Health 2018;4:166–73. ↩︎

- Scott H, Woods HC. Understanding links between social media use, sleep and mental health: Recent progress and current challenges. Curr Sleep Med Rep 2019;5:141–9. ↩︎

- van der Schuur WA, Baumgartner SE, Sumter SR. Social media use, social media stress, and sleep: Examining cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships in adolescents. Health Commun 2019;34:552–9. ↩︎

- Levenson JC, Shensa A, Sidani JE, Colditz JB, Primack BA. The association between social media use and sleep disturbance among young adults. Prev Med 2016;85:36–41. ↩︎

- Scott H, Biello SM, Woods HC. Identifying drivers for bedtime social media use despite sleep costs: The adolescent perspective. Sleep Health 2019;5:539–45. ↩︎

- Thompson SH & Lougheed E. Frazzled by Facebook? An Exploratory Study of Gender Differences in Social Network Communication among Undergraduate Men and Women. College Student Journal 2012;v46 n1 p88-98 Mar. ↩︎

- Tavernier R, Willoughby T. Sleep problems: predictor or outcome of media use among emerging adults at university? J Sleep Res 2014;23:389–96. ↩︎

Further information

Mirtazapine and sleep: will it help you sleep better?

Many of us check our social media accounts just before we go to sleep, but did you know that this can actually be a really bad idea if you want a good night’s rest? Read on to find out just how your social media habits can impact on your sleep.

Is a sound-based alarm clock the best way to wake up?

Medicines that can affect sleep

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site. To find out more, read our privacy notice .

Login to your account

If you don't remember your password, you can reset it by entering your email address and clicking the Reset Password button. You will then receive an email that contains a secure link for resetting your password

If the address matches a valid account an email will be sent to __email__ with instructions for resetting your password

Access provided by

Download started.

- PDF [958 KB] PDF [958 KB]

- Figure Viewer

- Download Figures (PPT)

- Add To Online Library Powered By Mendeley

- Add To My Reading List

- Export Citation

- Create Citation Alert

Adolescent use of social media and associations with sleep patterns across 18 European and North American countries

- Meyran Boniel-Nissim, PhD Meyran Boniel-Nissim Affiliations Department of Educational Counselling, The Max Stern Academic College of Emek Yezreel, Emek Yezreel, Israel Search for articles by this author

- Jorma Tynjälä, PhD Jorma Tynjälä Affiliations Faculty of Sport and Health Sciences, University of Jyvaskyla, Jyvaskyla, Finland Search for articles by this author

- Inese Gobiņa, PhD Inese Gobiņa Affiliations Department of Public Health and Epidemiology, Institute of Public Health, Riga Stradins University, Riga, Latvia Search for articles by this author

- Jana Furstova, MSc Jana Furstova Affiliations Olomouc University Social Health Institute, Palacky University Olomouc, Olomouc, Czech Republic Search for articles by this author

- Regina J.J.M. van den Eijnden, PhD Regina J.J.M. van den Eijnden Affiliations Interdisciplinary Social Science, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands Search for articles by this author

- Claudia Marino, PhD Claudia Marino Affiliations Department of Developmental and Social Psychology, University of Padova, Padova, Italy Search for articles by this author

- Helena Jeriček Klanšček, PhD Helena Jeriček Klanšček Affiliations National Institute of Public Health, Ljubljana, Slovenia Search for articles by this author

- Solvita Klavina-Makrecka, MSc Solvita Klavina-Makrecka Affiliations Department of Public Health and Epidemiology, Riga Stradins University, Riga, Latvia Search for articles by this author

- Anita Villeruša, MD Anita Villeruša Affiliations Department of Public Health and Epidemiology, Institute of Public Health, Riga Stradins University, Riga, Latvia Search for articles by this author

- Henri Lahti, MSc Henri Lahti Affiliations Faculty of Sport and Health Sciences, University of Jyvaskyla, Jyvaskyla, Finland Search for articles by this author

- Alessio Vieno, PhD Alessio Vieno Affiliations Department of Developmental and Social Psychology, University of Padova, Padova, Italy Search for articles by this author

- Suzy L. Wong, PhD Suzy L. Wong Affiliations Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, Canada Search for articles by this author

- Jari Villberg, MSc Jari Villberg Affiliations Faculty of Sport and Health Sciences, University of Jyvaskyla, Jyvaskyla, Finland Search for articles by this author

- Joanna Inchley, PhD Joanna Inchley Affiliations MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK Search for articles by this author

Design, setting, and participants

Measurements, conclusions.

- Social media

- Adolescents

- International survey

Introduction

- Spitzberg BH.

- Scopus (230)

- Google Scholar

Tankovska H. Percentage of US population who currently use any social media from 2008 to 2019. Statista. 2022. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/273476/percentage-of-us-population-with-a-social-network-profile/#:∼:text=In%20the%20United%20States%2C%20an,exceed%20257%20million%20by%202023 . Accessed January 29, 2022.

Anderson M, Jiang JJPRC. Teens’ social media habits and experiences. 2022. Available at: http://tony-silva.com/eslefl/miscstudent/downloadpagearticles/teensandsocialmedia-pew.pdf . Accessed January 29, 2022.

Inchley J, Currie D, Budisavljevic S, et al. Spotlight on adolescent health and well-being. Findings from the 2017/2018 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey in Europe and Canada. Volume 2. Key data. Vol. 1. 2020. International report.

- Scopus (54)

- Rosendahl I

- Jayaram-Lindström N

- Scopus (26)

- Van den Eijnden RJ

- Valkenburg PM.

- Scopus (449)

- Van Den Eijnden RJ

- Boniel-Nissim M

- Full Text PDF

- Scopus (139)

- van den Eijnden RJ

- Scopus (24)

- Scopus (112)

- Scopus (89)

- Roenneberg T.

- Scopus (1693)

- Matricciani L

- Scopus (200)

- Cohen-Zion M

- Tzischinsky O.

- Scopus (541)

- Reynolds S.

- Scopus (72)

- Scopus (775)

- Danielsen D

- Andersen S.

- Scopus (39)

- Hartstein LE

- LeBourgeois MK.

- Scopus (32)

- Scopus (31)

- Ter Bogt TF

- van der Rijst VG

- Scopus (21)

- Scopus (124)

- Scopus (42)

- Scopus (12)

- Przybylski AK

- Gladwell V.

- Scopus (1403)

- Hamilton JL

- Reinhardt L

- Scopus (17)

- Scopus (76)

Data and participants

Social media use.

Mascheroni G, Ólafsson K. Net children go mobile: risks and opportunities. 2022. Available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/55798/1/Net_Children_Go_Mobile_Risks_and_Opportunities_Full_Findings_Report.pdf . Accessed Jan 31, 2022.

- Scopus (2435)

- Finkenauer C

Sleep patterns

- Jankowski KS.

- Scopus (107)

Sociodemographic variables

- Scopus (256)

Statistical analysis

- Open table in a new tab

SMU and sleep duration

- View Large Image

- Download Hi-res image

- Download (PPT)

SMU and bedtime

SMU and social jetlag by country

SMU and sleep patterns by age

- Daly-Cano M

- Scopus (27)

- Zamanzadeh NN

- van der Schuur WA

- Baumgartner SE

- Scopus (29)

- Weinstein N.

- Scopus (367)

- Shimodera S

Study strengths and limitations

- Scopus (103)

Declaration of conflict of interest

Disclosures, appendix. supplementary materials.

- Download .docx (.16 MB) Help with docx files

Article info

Publication history, identification.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2023.01.005

User license

For non-commercial purposes:

- Read, print & download

- Redistribute or republish the final article

- Text & data mine

- Translate the article (private use only, not for distribution)

- Reuse portions or extracts from the article in other works

Not Permitted

- Sell or re-use for commercial purposes

- Distribute translations or adaptations of the article

ScienceDirect

- Download .PPT

Related Articles

- Access for Developing Countries

- Articles & Issues

- Articles In Press

- Current Issue

- List of Issues

- Special Issues

- Supplements

- For Authors

- Author Information

- Download Conflict of Interest Form

- Researcher Academy

- Submit a Manuscript

- Style Guidelines for In Memoriam

- Download Online Journal CME Program Application

- NSF CME Mission Statement

- Professional Practice Gaps in Sleep Health

- Journal Info

- About the Journal

- Activate Online Access

- Information for Advertisers

- Career Opportunities

- Editorial Board

- New Content Alerts

- Press Releases

- More Periodicals

- Find a Periodical

- Go to Product Catalog

The content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Accessibility

- Help & Contact

Western News

We’ve all done it – scrolled through our phones immediately before bedtime to read the latest news, only to wake up at 3 a.m. feeling anxious about all the things we’ve read. Then, having trouble falling back to sleep, we grab our phones again and distract ourselves with social media.

The next day we wake up feeling overwhelmed, anxious and exhausted.

But how exactly do social media and poor sleep influence our mental health? Researchers in the department of epidemiology and biostatistics at Western’s Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry are working to understand the relationship between sleep, social media and mental health among youth in two recently published papers.

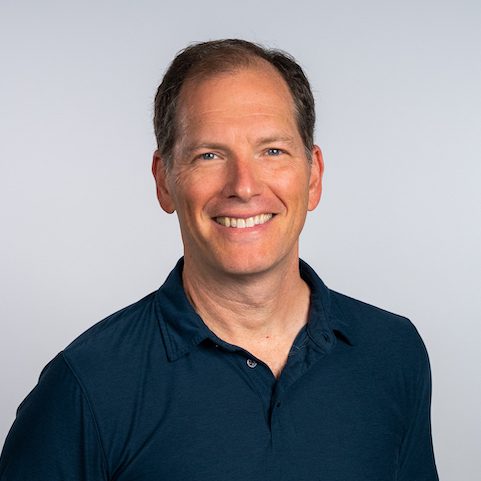

Professor Kelly Anderson, PhD, looked specifically at the role of social media in the equation through a systematic review of previously published studies.

“The literature highlighted how complex this relationship is,” said Anderson, who is also a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Public Mental Health Research. “These things are likely bidirectional; they are likely all part of a larger process that are feeding back to each other. So, if you aren’t sleeping well, you are probably going to use social media more often, which is going to impact your mental health, which impacts your sleep and so on.”

This topic has become especially important during the pandemic, said Rea Alonzo, a master’s student and contributing author on the paper, published in the journal Sleep Medicine Reviews. “Youth may be resorting to using more social media, given the current social restrictions. Also, as youth continue with online learning, technology is more easily accessible to them and screen time may be escalated.”

The review found significant associations between excessive social media use and poor mental health outcomes, and between poor sleep quality and negative mental health. Frequent social media use was a risk factor for both poor mental health and poor sleep outcomes.

“The link between the three is what really interested us,” said Junayd Hussain, one of the contributing authors on the review. “Based on our research, it seemed as though at least part of the negative effects that social media use has on mental health may act through sleep disturbances.”

The authors noted that none of the studies in the review specifically looked at the interplay of all three factors and Anderson says it is an area that warrants further study.

“One of the main takeaways is that this is a very complex process, and we are going to need really good data to try to tease apart the contributions of each and the mechanisms underlying these relationships,” said Anderson.

Another recently published study from the department of epidemiology and biostatistics found that adolescents who experience difficulties sleeping are at higher risk of developing symptoms of anxiety and depression, and that this relationship is strongest among girls.

Analyzing data from the Canadian National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth, the study published in the Journal of Psychosomatic Research found that girls with persistent difficulties sleeping between the ages of 12 and 15 experienced higher rates of anxiety and depression.

“When present, these symptoms can persist into young adulthood and negatively impact relationships, quality of life and employment,” said Dr. Saverio Stranges, chair of the department of epidemiology and biostatistics, who was senior investigator on the study. “This study highlights the potential role of difficulties sleeping for adolescents’ mental health. Our findings further emphasize the need for public health initiatives to promote sleep hygiene in this population subgroup facing a critical life transition.”

One of the ways to promote good sleep hygiene is to limit screen time before bed, said Stranges, whose collaborators included MSc graduate Sophia Nunes along with Western professors Karen Campbell, Neil Klar and Graham Reid.

“Adolescent sleep problems are a current public health concern,” said Nunes. “Up to 25 per cent of 12- to 15-year-old Canadians report difficulties sleeping more than once a week. From a public health perspective, this research contributes to the evidence on the important and potential long-term mental health impact of sleep problems in early adolescence.”

Topic Featured 1 Headline 3 Research

SHARE THIS STORY

Up next ….

Western draws top number of Early Researcher Awards

Front Hero , Research

10 faculty attract provincial funding for projects focused on health, homelessness and climate change

Related Stories

Popular this week.

- Researchers a step closer to HIV cure 158 views

- Western draws top number of Early Researcher Awards 73 views

- Geoffrey Little named new vice-provost and chief librarian 66 views

Social Media Use and Sleep

Written by Dr. Michael Breus

Social media is ever-present in the lives of most Americans. Experts suggest that 72% of people use some form of social media, with many users accessing common platforms at least once a day.

Well-known social media sites such as Facebook, YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram allow users to message, video chat, and share personal content in online communities. These platforms can be a place for connection, entertainment, and news.

Unfortunately, a growing body of research suggests sleep health in teenagers and children may suffer because of electronic devices and social media use. More studies are needed to understand the relationship between sleep health and social media use in adults as their online activity increases. However, initial research suggests an association between sleep disturbances and social media use.

Learning about how social media could be impacting your sleep can empower you to develop healthy social media habits that encourage a better night’s sleep.

How Does Social Media Affect Sleep?

Research investigating social media and sleep is ongoing, but experts suggest that there are several ways that social media could influence whether people sleep well.

Blue light emitted from electronic devices used for exploring social media sites, the fear of missing out when offline, and noisy alerts and notifications are all known culprits of poor sleep health in the digital age.

Blue Light and Melatonin

People who scroll through social media on electronic devices in the hours leading up to bedtime or at night may encounter a range of sleep problems due to blue light exposure. These include trouble falling asleep, waking up earlier than expected, disrupted sleep, and more time spent sleeping during the day.

Melatonin is a hormone that promotes sleepiness. Your body naturally produces melatonin in the evening, after the sun goes down, as a part of your sleep-wake cycle . However, electronic devices, such as phones, tablets, and laptops, emit blue light that interferes with this process.

In response to light, including blue light, your body suppresses melatonin production. This is why blue light exposure before bed makes it more difficult to fall and stay asleep.

Fear of Missing Out

Fear of missing out, sometimes called FOMO, is associated with sleep loss and may lead to poor sleep quality . FOMO is a recent phenomenon that describes a sense of exclusion or concern about missing out when disconnecting from online communities.

For social media users that experience FOMO, the urge to check social media applications may be irresistible and constant, including at night when it is time to fall asleep and immediately upon awakening in the morning.

Disturbed Sleep

The “always-on” functionality of smartphones and social media applications disrupt sleep patterns. Devices like televisions and laptops can be turned off for the night, while persistent social media and message alerts—which often include a physical vibration or audible indicator—may occur at any time, disturbing sleep.

Excessive messaging before bedtime can negatively affect sleep as well. Unrelenting notifications and alerts from social media and smartphone apps in the evening can make it difficult to relax and prepare for restful sleep. Research indicates that difficulty falling asleep due to constant notifications can lead to sleep deprivation .

Effects of Social Media on Youth

Nearly all U.S. adolescents have access to a smartphone, and the percentage of youth that describe themselves as being “constantly online” grows each year. The increased time spent engaging with online communities using social media can negatively affect adolescent sleep.

Research shows that teenagers that frequently use social media are at risk for waking up too early and may struggle with going back to sleep. Teens who use social media may take longer to fall asleep and have poor sleep quality.

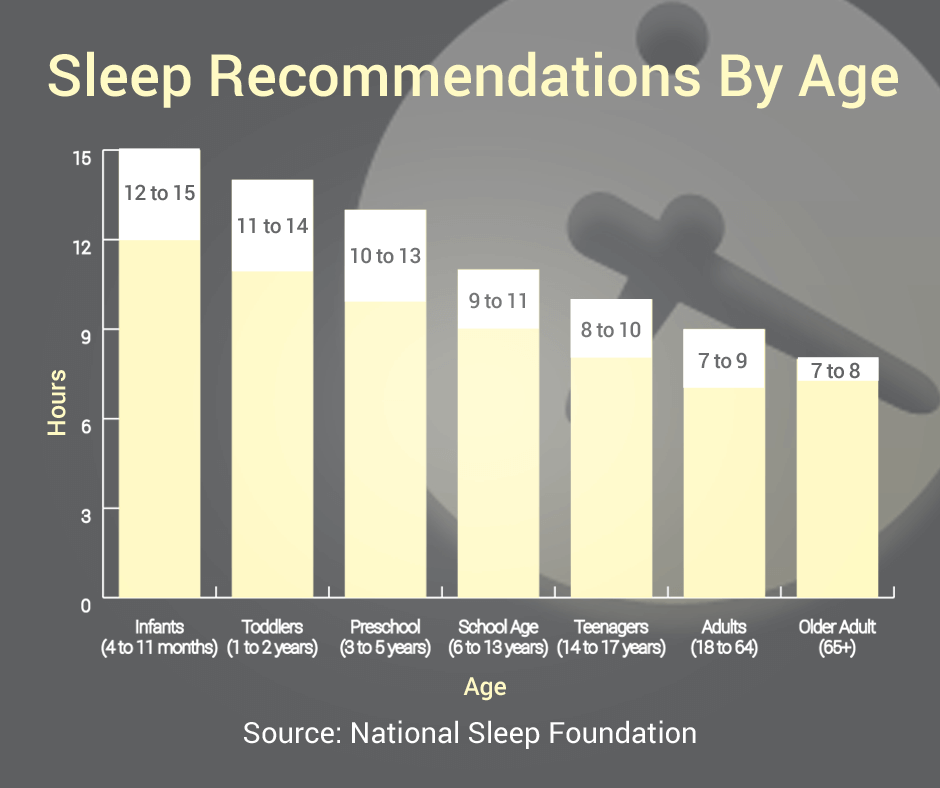

Getting a healthy amount of sleep is important for people of all ages, including children and adolescents. Adequate sleep can help prevent injuries, poor physical and mental health, and problems with behavior and attention.

Recommendations to Sleep Better

Social media users looking for a better night’s sleep may benefit from adjusting their sleep habits. A bedtime routine and sleep environment that encourage healthy social media habits may reduce or prevent the harmful effects of social media on sleep.

- Avoid Screen Use Before Bed : Using electronic devices to interact on social media platforms at night can lead to poor sleep quality. Avoid or limit screen time use in the hours leading up to bedtime and once in bed.

- Silence Notifications : Alerts from social media and other device applications may disrupt sleep and lead to sleep problems including daytime sleepiness. Turn off notifications to keep your device quiet throughout the night and to deter you from checking updates or responding to messages.

- Relocate Bedside Devices: Consider moving devices that allow access to social media to another location in your bedroom or home while you’re in bed to avoid notifications and scrolling through social media sites from bed.

- Make Time to Unplug From Devices: Experts suggest taking scheduled social media breaks to reduce your time spent on devices. During the time you unplug from your device and social media accounts, you may find it helpful to connect with friends offline, exercise, or explore activities that allow you to relax.

- Support Healthy Social Media Use in Teens : If you are involved in the care of a teen or child that uses social media, it is important to model healthy boundaries around social media and electronic device use. This includes establishing rules for when and where your teen can use devices and social media and setting limits on how much time they spend engaged with their device.

- https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/

- https://www.apa.org/monitor/2017/03/cover-disconnected

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26791323/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32065542/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34307542/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25560435/

- https://www.uptodate.com/contents/insufficient-sleep-evaluation-and-management

- https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/sleep/sleep-wake-cycle

- https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2017/technology-social-media.pdf

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02673843.2016.1181557

- https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000872.htm

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31641035/

- https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/sleep-deprivation

- https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/sleep_hygiene.html

- https://doi.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fppm0000156

- https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/your-guide-healthy-sleep

- https://www.apa.org/monitor/2018/11/cover-misuse-digital

- https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000757.htm

- https://www.healthychildren.org/English/family-life/Media/Pages/Tips-for-Parents-Digital-Age.aspx

About The Author

Clinical Psychologist, Sleep Medicine Expert

Michael Breus, Ph.D is a Diplomate of the American Board of Sleep Medicine and a Fellow of The American Academy of Sleep Medicine and one of only 168 psychologists to pass the Sleep Medical Specialty Board without going to medical school. He holds a BA in Psychology from Skidmore College, and PhD in Clinical Psychology from The University of Georgia. Dr. Breus has been in private practice as a sleep doctor for nearly 25 years. Dr. Breus is a sought after lecturer and his knowledge is shared daily in major national media worldwide including Today, Dr. Oz, Oprah, and for fourteen years as the sleep expert on WebMD. Dr. Breus is also the bestselling author of The Power of When, The Sleep Doctor’s Diet Plan, Good Night!, and Energize!

- POSITION: Combination Sleeper

- TEMPERATURE: Hot Sleeper

- CHRONOTYPE: Wolf

Get Your Sleep Questions Answered Live on April 3rd

Have questions about sleep? Join us for the next YouTube Live with sleep expert Dr. Michael Breus on Wednesday, April 3rd at 4 p.m. PDT/7 p.m. EDT. Dr. Breus will be taking all of your sleep-related questions and offering some tips and tricks for getting better sleep each night. You can also send us an email . Please note, we cannot provide specific medical advice, and always recommend you contact your doctor for any medical matters.

Recommended Reading

Technology and sleep, how blue light affects sleep, best sleep apps, best blue light blocking glasses: protect your eyes, sleep better, can video games affect sleep, how binge watching can affect sleep, is your smartphone affecting your sleep, your results are in.

Creating a profile allows you to save your sleep scores, get personalized advice, and access exclusive deals.

Create a Sleep Profile to Access More

Free sleep doctor score™.

See how your sleep habits and environment measure up and gauge how adjusting behavior can improve sleep quality.

Personalized Sleep Profile

Your profile will connect you to sleep-improving products, education, and programs curated just for you.

Exclusive Deals

Gain access to exclusive deals on mattresses, bedding, CPAP supplies, and more.

Registering and logging into your profile!

Use of this quiz and any recommendations made on a profile are subject to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

Profile Registration

A Profile With This Email Address Already Exists!

Already have a Sleep Profile?

Based on your answers, we will calculate your free Sleep Doctor Score ™ and create a personalized sleep profile that includes sleep-improving products and education curated just for you.

The Impact of Social Media Use on Sleep and Mental Health in Youth: a Scoping Review

- Open access

- Published: 08 February 2024

- Volume 26 , pages 104–119, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Danny J. Yu 1 ,

- Yun Kwok Wing 1 ,

- Tim M. H. Li 1 &

- Ngan Yin Chan 1

2199 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Purpose of Review

Social media use (SMU) and other internet-based technologies are ubiquitous in today’s interconnected society, with young people being among the commonest users. Previous literature tends to support that SMU is associated with poor sleep and mental health issues in youth, despite some conflicting findings. In this scoping review, we summarized relevant studies published within the past 3 years, highlighted the impacts of SMU on sleep and mental health in youth, while also examined the possible underlying mechanisms involved. Future direction and intervention on rational use of SMU was discussed.

Recent Findings

Both cross-sectional and longitudinal cohort studies demonstrated the negative impacts of SMU on sleep and mental health, with preliminary evidence indicating potential benefits especially during the COVID period at which social restriction was common. However, the limited longitudinal research has hindered the establishment of directionality and causality in the association among SMU, sleep, and mental health.

Recent studies have made advances with a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of SMU on sleep and mental health in youth, which is of public health importance and will contribute to improving sleep and mental health outcomes while promoting rational and beneficial SMU. Future research should include the implementation of cohort studies with representative samples to investigate the directionality and causality of the complex relationships among SMU, sleep, and mental health; the use of validated questionnaires and objective measurements; and the design of randomized controlled interventional trials to reduce overall and problematic SMU that will ultimately enhance sleep and mental health outcomes in youth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Social Media Addiction in High School Students: A Cross-Sectional Study Examining Its Relationship with Sleep Quality and Psychological Problems

Adem Sümen & Derya Evgin

Effects of Excessive Screen Time on Neurodevelopment, Learning, Memory, Mental Health, and Neurodegeneration: a Scoping Review

Eliana Neophytou, Laurie A. Manwell & Roelof Eikelboom

Social Media and Depression Symptoms: a Meta-Analysis

Simone Cunningham, Chloe C. Hudson & Kate Harkness

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Youth population, which typically refers to individuals between the ages of 15 and 24, experience substantial changes in their neurobiology, physical development, behavior, and emotions, making it a vulnerable stage for the development of both sleep and mental health problems [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. In Hong Kong, approximately 64.5% of adolescents sleep less than 8 h during weekdays [ 4 ] and 29.2% have reported insomnia symptoms [ 5 ]. Both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have demonstrated that sleep loss and disturbances in youth lead to significant personal distress, increase risk of psychiatric illnesses, and risky behaviors such as drug abuse and dangerous driving [ 5 , 6 ]. In addition to sleep disturbances, mental health problems are highly prevalent among the youth population. Evidence suggested that nearly 75% of psychiatric illnesses have their age onset during adolescence [ 7 , 8 ].

There are multiple risk factors that commonly contribute to sleep and mental health problems, including being female, heavy school workload, physical inactivity, and worse general health [ 9 ]. Recently, a growing number of studies indicate that social media use (SMU) is associated with both sleep and mental health problems in youth [ 10 •]. In particular, identity development and peer acceptance during adolescence are important developmental needs, at which social media may apparently serve as a convenient means to meet these needs. A previous study reported that over 80% of adolescents (16–19 years) use electronic devices near bedtime [ 11 ]. On the other hand, excessive SMU can have detrimental health effects [ 12 , 13 ], and contribute to various negative repercussions such as cyberbullying [ 14 ], gender stereotypes [ 15 ], self-objectification [ 16 ], and exposure to inappropriate content, such as unsolicited violent and sexual contents [ 17 ]. The effect becomes more prominent in young people who are considered as digital native [ 18 ]. Nevertheless, SMU also comes with some potential benefits [ 19 ] such as increased self-esteem [ 20 ], increased social capital [ 21 ], identity presentation and sexual exploration [ 22 ], and social support [ 23 ].

Despite the emerging evidence supporting the link among SMU, sleep, and mental health, the relationship and directionality are complex and inconsistent. For example, two recent studies did not find significant associations among SMU, sleep, and mental health [ 24 , 25 •]. Nonetheless, a US study reported that greater SMU was significantly associated with sleep disturbances [ 26 ], and some also reported bidirectional relationship at which poor sleepers tend to use electronic devices as a sleep aid [ 27 ]. In general, it is believed that youth are at a higher risk of experiencing the negative impacts of SMU as they are more susceptible to peer pressure and fear of missing out (FOMO). FOMO refers to the perception of missing out on enjoyable experiences, followed up with a compulsive behavior to maintain these social connections with others to avoid being excluded from those experiences [ 28 , 29 , 30 ]. Hence, understanding the association and directionality among SMU, sleep, and mental health is crucial for developing public health strategies on how to cultivate healthy SMU habits and develop effective interventions targeting inappropriate and excessive SMU.

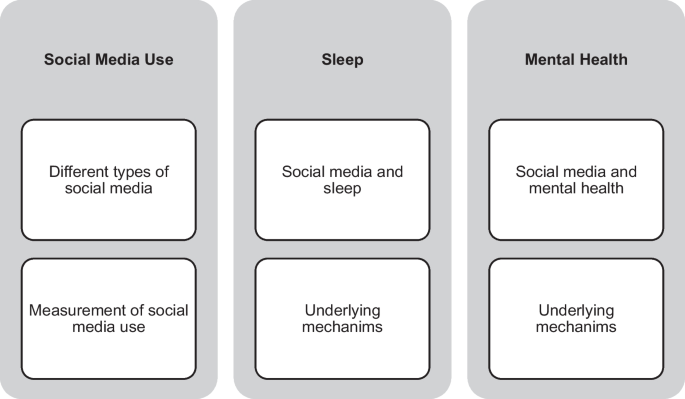

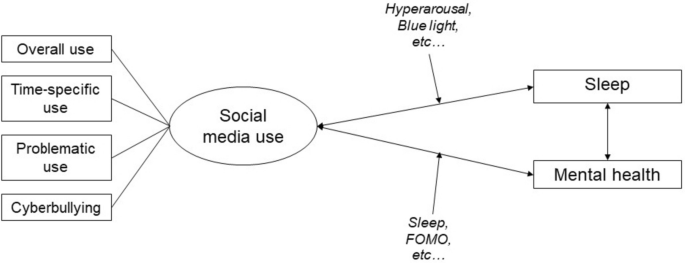

This scoping review summarized recent studies on SMU, sleep, and mental health in youth (Fig. 1 ) and explored the potential underlying mechanisms of how SMU affects sleep and mental health in youth (Fig. 2 ). Finally, we have put forward several potential avenues for future research and recommendations in this area. Search terms including #adolescent, #social media, #sleep, and #mental health were used to search for relevant studies that were published between January 2020 and July 2023 in MEDLINE. A summary of the study attributes, such as the authors, the country/region where the study was conducted, study design, the number of participants, sample age range, characteristics, as well as the measures used to assess SMU, sleep, and mental health are listed in Table 1 .

Structure of the scoping review

Potential pathways of social media use on sleep and mental health

Overview of SMU

SMU refers to the act of engaging with online platforms specifically designed for social interaction, whereas electronic media use (or digital use, digital media, internet use, screen time) is a broader term that encompasses various forms of media delivered electronically, including but not limited to social media. In this scoping review, we focus on SMU.

Over the past decade, subjective measures have been the primary tool to investigate individual perceptions, opinions, or personal experiences of SMU. For example, a self-report scale was developed to assess compulsive use of social media and its severity [ 31 ]. Besides, there are several platform-specific scales for social media addiction features such as salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse. The Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale, for instance, focuses specifically on addiction to Facebook [ 32 •], while the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale has emerged to examine a broader scope, including social media platforms beyond Facebook [ 33 •, 34 ]. Indeed, more researchers used general metrics to measure SMU across multiple platforms collectively such as the Social Media Disorder Scale which measures aspects of social media addiction features, such as preoccupation with social media, excessive time spent, withdrawal symptoms, and negative consequences [ 35 , 36 , 37 ]. Other SMU experiences are also captured including social comparison on social media and negative experiences such as bullying, FOMO, and extensive negative feedback [ 32 •].

In addition, the duration and timing of SMU also have significant implications for sleep and mental health, as excessive or inappropriate use of social media at certain timing, for example at bedtime, can potentially contribute to negative biopsychosocial effects. The Socio-Digital Participation Inventory includes four items to measure the frequency of SMU on a seven-point frequency scale (1 = never, 2 = a couple of times a year, 3 = monthly, 4 = weekly, 5 = daily, 6 = multiple times a day, 7 = all the time) [ 25 •]. The total time spent on SMU (in daytime and night-time) are usually captured by questionnaires and social media time use diary [ 38 •]. In view of the limitation of self-reported measures, there has been a shift towards incorporating more objective measures in addition to subjective self-report scales. Increasing number of studies used time tracker via specific apps (installed on participants’ devices used for online activity) to reduce recall bias [ 33 •]. Other objective features, such as the number of followers, likes, comments, shares, bookmarks, and total interactions, which can be retrieved from various social media platforms [ 39 •] were also used to reflect social medica engagement. In addition, the content (e.g., educational vs non-educational) posted, read, and shared on social media platforms plays a significant role in shaping user experiences, engagement levels, and the overall impact of SMU. It is worth to note that no included studies attempted to measure multi-device SMU as it can be challenging due to the wide range of devices that people use to access social media platforms. Traditional research methods often rely on self-reporting, surveys, or tracking software installed on specific devices, which may not capture the full extent of multi-device usage. Some individuals may switch between multiple devices throughout the day, making it challenging to track their overall social media engagement accurately.

Overview of Recent Studies

Study characteristics.

A total of 33 studies were included in this scoping review, with 26 of them were cross-sectional in nature, indicating a snapshot overview of the relationship between SMU, sleep, and mental health. Moreover, only a few studies utilized representative samples [ 35 , 36 , 40 , 41 ], as outlined in Table 1 . It is also worth noting that the sample sizes varied significantly across studies, ranging from 54 to 195,668 participants.

Measurement of SMU

In terms of the measurement of SMU, all studies used either self-developed questionnaires (e.g., “in a typical school week, how often do you check social media?” and “on a normal weekday, how many hours you spend on social medias, write blogs/read each people blogs, or chat online?”) or validated self-report questionnaires (e.g., the 26-item Chinese Internet Addiction Scale-Revised and the Online Civic Engagement Behavior Construct). Different dimensions of SMU were measured such as overall and night-time SMU, problematic SMU, emotional investment in social media, racial discrimination, and racial justice civic engagement on social media. Only a limited number of studies incorporated more reliable measurements such as ecological momentary assessment [ 42 ] and total message count [ 43 ].

Measurement of Sleep and Mental Health

In terms of sleep outcome assessment, most of these studies employed subjective instruments such as sleep diary [ 32 •], self-developed self-report questionnaires (e.g., “How many hours did you sleep over the past week?”) [ 43 ], and validated self-report questionnaires (e.g., the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and the Insomnia Severity Index) [ 44 , 45 •] to measure different sleep outcomes including sleep quality, sleep duration, sleep displacement, bedtime, and sleep-onset latency. In addition to these subjective instruments, 3 studies have utilized objective devices such as actigraphy and other wearable devices to capture objective sleep data [ 43 , 46 , 47 ]. While for mental health aspects, depression and anxiety are the main outcomes. Most of the recent studies utilized standardized questionnaires such as the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire, the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales 21, and the Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised to measure the symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Synthesis of Recent Findings

Smu and sleep.

Both longitudinal and cross-sectional studies tend to support the association between SMU and sleep disturbances (Table 1 ). A total of 17 cross-sectional studies observed an association between SMU and various sleep parameters in youth. Of these studies, a total of 16 reported a significant association between different dimensions of SMU (internet addition, duration of screen use, inappropriate time use (near bedtime), with one additionally measure parent control of technology) and poor sleep outcomes (both subjectively and objectively measured sleep parameters, such as bedtime, sleep-onset latency, sleep duration, and sleep quality) [ 31 , 32 •, 35 , 36 , 40 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 •, 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 ]. Nevertheless, a study of 101 undergraduate students did not find that bedtime SMU was detrimental to sleep [ 46 ]. However, in the subgroup analysis, the authors found that youth with increased levels of depressive symptoms are at higher risk of experiencing negative impacts of bedtime SMU on sleep [ 46 ].

Among the three cohort studies, two indicated that higher levels of SMU predicted later bedtime and shorter sleep duration in youth after 1–2 years of follow-up [ 37 , 54 ]. These studies revealed that both frequent and problematic use of SMU could result in later bedtime [ 37 , 54 ]. In addition, Richardson and colleagues further found that SMU predicted greater daytime sleepiness in adolescence [ 54 ]. In addition, adolescents with evening chronotype preference and shorter sleep duration were found to have longer usage of social media, suggesting a potential bidirectional relationship between SMU and sleep duration [ 54 ]. Another cohort study conducted by Maksniemi and colleagues did not find a significant association between SMU and bedtime among 426 youth aged between 13 and 19 [ 25 •]. Interestingly, subgroup analyses indicated that significant associations were only observed in early adolescence (at age 13 and 14), but not in middle (at age 14 and 15) nor late adolescence (at age 17 and 18) [ 25 •]. This finding highlights the importance of considering the developmental stages of youth in order to unravel the complex relationship between SMU and sleep [ 55 ].

SMU and Mental Health

A total of 9 cross-sectional studies examined the relationship between SMU and mental health [ 33 •, 34 , 38 •, 39 •, 56 •, 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 ]. A greater amount of time spent on social media was associated with an increased risk of depression, self-harm, and lower self-esteem. On the other hand, adolescents who exhibited mental health issues tended to spend more time on social media platforms, suggesting a potential bidirectional relationship between SMU and mental health. However, it is important to point out that despite appealing hypotheses, actual effect size estimates of SMU on various mental health outcomes (e.g., self-esteem, life satisfaction, depression, and loneliness) were of small-to-medium magnitude as reported in previous meta-analytic studies, ranging from − 0.11 to − 0.32 [ 61 •, 62 ].

Four longitudinal cohort studies reported mixed findings between SMU and mental health [ 41 , 63 , 64 •, 65 ]. Two cohort studies conducted in the USA and China reported that frequent and problematic SMU were significantly associated subsequent mental health issues [ 64 •, 65 ]. Interestingly, the authors identified substantial sex differences in the mental health trajectories, with only girls showing a deteriorating linear trend ( β = 0.23, p < 0.05) [ 64 •]. On the contrary, the other two longitudinal studies conducted in Sweden and UK reported that although frequent SMU was associated with increased levels of mental problems at a single timepoint, there was no longitudinal association [ 41 , 63 ], which suggests that SMU may be only an indicator for mental health instead of a risk factor.

SMU, Sleep, and Mental Health

A total of 7 studies measured both sleep and mental health outcomes [ 31 , 45 •, 46 , 47 , 48 , 50 , 59 ]. Five of these studies reported significant associations among SMU, sleep, and mental health outcome [ 31 , 45 •, 46 , 50 , 59 ]. It was reported that SMU was significantly associated with poor sleep quality and increased mental health issues [ 31 , 45 •, 46 , 50 , 59 ], and sleep was found to mediate the negative impacts of SMU on mental health and emotional symptoms in adolescents [ 45 •]. Poor sleep was also shown to be significantly associated with mental health outcomes [ 31 , 50 , 59 ]. Furthermore, adolescents with higher level of depressive symptoms were at higher risk of experiencing negative impacts of bedtime SMU on sleep outcomes [ 46 ]. Indeed, these findings preliminarily unveiled the complex interplay among SMU, sleep, and mental health.

Nevertheless, it is essential to highlight that recent research has also recognized the positive impacts of SMU on mental health, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, at which physical social interactions were significantly disrupted [ 56 •, 58 ]. Adolescents in Australia and UK were found to use social media as an active coping strategy to relieve external stressors (e.g., exam pressure), to seek support for suicidal ideation or self-harm behavior, and to support others via social media [ 56 •, 58 ].

This scoping review synthesized recent publications from the past 3 years that investigated the impact of SMU on sleep and/or mental health outcomes in youth. The majority of the studies provide supporting evidence for an association between SMU, poor sleep quality, and adverse mental health outcomes. Problematic SMU or addiction, as well as the duration of SMU, were identified as the most prevalent aspects of social media examined in the included studies. Sleep duration, bedtime, and insomnia emerged as the most commonly assessed sleep problems, while depression and anxiety were the most frequently measured mental health outcomes. However, it is important to note that despite the significant associations identified among these variables, the directionality of the relationship remains unclear in view of inconsistent findings across studies.

Underlying Mechanism Between SMU and Sleep

Numerous mechanisms have been proposed to elucidate the relationship between social/digital media usage and sleep quantity and quality [ 66 ]. Hyperarousal, a core mechanism in explaining insomnia [ 67 ], plays a role in explaining how night-time SMU disrupts sleep. Active engagement in media activities can directly induce physiological and psychological arousal, leading to longer sleep onset latency [ 68 ]. This effect is particularly noticeable when individuals actively engage in interactive digital media, such as social messaging and social media, as opposed to passive media consumption like television viewing [ 69 •], likely due to the heightened arousal associated with interactive activities [ 70 ]. Interestingly, a study found that engaging in phone conversations near bedtime was associated with longer sleep duration, while the use of social media and texting displayed a negative association [ 71 ]. It has been hypothesized that conversing with a friend may positively influence emotional well-being, thereby promoting sleep [ 72 ]. However, social networking, despite its potential for fostering friendships, may also trigger FOMO and social media stress. In addition to the psychological arousal induced by electronic media usage, the light emitted from device screens is another hypothesis explaining the detrimental effects of digital media on sleep. Specifically, the light emitted by electronic devices, especially blue light (at a wavelength of 480 nm), has a significant impact on the suppression of melatonin, a hormone that promotes sleep [ 73 ]. Moreover, a recent study indicated that high-risk adolescents whose parents with bipolar affective disorder have lower level of nocturnal melatonin secretion. It might be possible that adolescents with certain risk factors (even without psychopathologies) may be particularly hypersensitive and vulnerable to light suppression of melatonin secretion [ 74 ], which are considered as high-risk group that require early intervention. Furthermore, it is plausible that an interaction or interplay might exist between arousal and light exposure, and the combination of these conditions could potentially heighten the risk of sleep disturbances. Additionally, the direct displacement of sleep resulting from engagement in social media activities may also lead to shorter sleep duration. Although initial evidence suggests a negative impact of both content and light emitted by electronic devices on sleep, the precise underlying mechanism remains poorly established. Last but not least, some preliminary studies have also investigated other sleep- and circadian-related factors such as chronotype preference and daytime sleepiness in mediating and/or moderating the relationship between SMU and sleep [ 32 •, 44 , 54 ], albeit the findings have been inconclusive. Future studies are warranted to thoroughly explore the role of these factors in the interplay between SMU and sleep.

Underlying Mechanism Between SMU and Mental Health

It has been suggested both behavioral and cognitive factors mediate the impact of SMU on mental health. Among the behavioral factors, sleep has been identified as one of the notable mediators of the association [ 31 , 44 , 45 •, 46 , 50 , 59 , 75 ]. Physiologically, prolonged SMU before bedtime delays sleep onset, reduces sleep duration, and mediates the association between eveningness and sleep as well as daytime sleepiness [ 44 ], which have been identified as risk factors for mental illness [ 76 , 77 , 78 ]. This complex interplay between sleep and mental health has also been documented in interventional studies. Our previous clinical trial demonstrated that a brief insomnia prevention program, adapted from cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia, significantly decreased the severity of depressive symptoms in adolescents at 12-month follow-up [ 79 ], suggesting the potential mediating role of sleep in mental health. While for the cognitive factors, FOMO has been recognized as a possible mediator. In particular, Elhai et al. reported that FOMO mediated relationship between anxiety and smartphone use frequency, as well as problematic SMU [ 80 ]. Besides FOMO, recent literatures have also identified several other cognitive factors that mediate the relationship between SMU and mental health, such as self-esteem [ 38 •], body satisfaction [ 57 ], and emotional investment [ 59 ].

In addition to these behavioral and cognitive factors, cyberbullying is also one of the important mediators of SMU and mental health in youth [ 81 ]. Cyberbullying has become a prevalent phenomenon worldwide, with victimization rates in children and adolescents ranging from 14 to 57.5%, and lifetime perpetration rates ranging from 6.0 to 46.3% [ 82 , 83 ]. Previous meta-analytical study demonstrated that cyberbullying significantly increased the risks of developing depression, self-harm, suicidal attempts, and ideation [ 84 ]. Moreover, over the COVID-19 pandemic, stressors associated with disasters have also been reported to potentially exacerbate the negative effects of SMU on mental health, thereby increasing the risk for mental health issues [ 85 , 86 ].

In summary, there have been significant developments in recent years in understanding the magnitude and mechanisms that underlie the association between SMU and mental health. However, most of the studies employed a cross-sectional design, which prevented from a thorough understanding of the causality. Experimental and interventional studies are warranted to better comprehend the underlying mechanisms, establish causality, and improve the negative outcomes.

Future Direction

There are several potential avenues for future investigation. Firstly, prospective cohort studies using representative samples are needed to elucidate the magnitude and directionality of relationships among SMU, sleep, and mental health, which is of clinical practice implication for precision intervention. To capture the varying dynamics among SMU, sleep, and mental health across different age groups of adolescents (early and late adolescents), it is recommended that prospective studies may need to have a follow-up period that will better cover the entirety of adolescence period [ 41 ]. Secondly, the lack of consistency in the methodologies employed by different studies measuring SMU has been a major contributing factor to the conflicting findings found in the current literature. It is imperative to use validated questionnaires to measure the SMU. More importantly, objective measurements (e.g., screen time monitors on smartphones [ 87 ], ecological momentary assessments [ 88 ], and wearable devices [ 89 ]) should also be incorporated. Apart from timing, it is equally important to capture the content, and number of devices that subjects engage with. Thirdly, future research should consider conducting randomized controlled trials at different levels (e.g., individual, school, and family) to reduce overall and problematic SMU and to ultimately improve sleep and mental health outcomes in youth. The design of the intervention may benchmark to existing guidelines such as the American Academy of Paediatrics recommendations 2016 on media use [ 90 ], and the WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behavior [ 91 ], in which both guidelines recommend limiting the amount of recreational screen time, and avoiding SMU 1 h before bedtime. Intervention formats may consider psychoeducation, cognitive and behavioral techniques, and motivational interviewing. Finally, priority may be given to conduct observational and interventional studies on SMU in vulnerable populations, such as youth experiencing mood or sleep problems, as well as those who are high-risk offspring of parents with sleep and mood disorders, as these populations are more susceptible to experience significant negative impacts from inappropriate and excessive SMU [ 92 ].

Despite the heterogeneity observed in the recent studies, both cross-sectional and cohort studies highlight the impact of SMU on poor sleep and mental health, albeit there are some inconsistent findings. Research has progressed from focusing solely on “screen time” to exploring the social, emotional, and cognitive dimensions of SMU. When measuring sleep outcomes, researchers have investigated the sleep duration and quality and also consider factors such as chronotype and pre-sleep arousal, which will enable a better understanding of how social media impacts sleep in a broader context. Similar advancements have also been made in the field of SMU-related mental health research. Recognizing the interconnections among SMU, sleep, and mental health is crucial for public health and will contribute to improving sleep and mental health outcomes while promoting rational SMU. Future studies should evaluate the effectiveness of interventions on reducing SMU, with ultimate goal to improve sleep and mental health.

Data Availability

Since this review article solely relies on published articles and does not include individual participant data, therefore no data sharing is available.

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Nations U. Secretary General’s Report to the General Assembly, (A/36/215). 1981. United Nations New York, NY, USA.

Blair RJR. The neurobiology of psychopathic traits in youths. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(11):786–99.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pichardo AW, et al. Integrating models of long-term athletic development to maximize the physical development of youth. Int J Sports Sci Coach. 2018;13(6):1189–99.

Article Google Scholar

Wing YK, et al. A school-based sleep education program for adolescents: A cluster randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3):e635–43.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Chen SJ, et al. The trajectories and associations of eveningness and insomnia with daytime sleepiness, depression and suicidal ideation in adolescents: A 3-year longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2021;294:533–42.

Roane BM, Taylor DJ. Adolescent insomnia as a risk factor for early adult depression and substance abuse. Sleep. 2008;31(10):1351–6.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Merikangas KR, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S.adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 2010. 49(10): p. 980–9.

Kessler RC, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602.

Grandner MA, et al. Social and behavioral determinants of perceived insufficient sleep. Front Neurol. 2015;6:112.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

• Alonzo R, et al. Interplay between social media use, sleep quality, and mental health in youth: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2021;56: 101414. Systematically reviewed the relationship between SMU, sleep, and mental health, using the literature published until 2020.

Hysing M, et al. Sleep and use of electronic devices in adolescence: Results from a large population-based study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1): e006748.

Levenson JC, et al. Social media use before bed and sleep disturbance among young adults in the United States: A nationally representative study. Sleep, 2017. 40(9): p. zsx113.

Viner RM, et al. Roles of cyberbullying, sleep, and physical activity in mediating the effects of social media use on mental health and wellbeing among young people in England: A secondary analysis of longitudinal data. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 2019;3(10):685–96.

Craig W, et al. Social media use and cyber-bullying: A cross-national analysis of young people in 42 countries. J Adolesc Health. 2020;66(6):S100–8.

Jungblut M, Haim M. Visual gender stereotyping in campaign communication: Evidence on female and male candidate imagery in 28 countries. Commun Res. 2023;50(5):561–83.

Feltman CE, Szymanski DM. Instagram use and self-objectification: The roles of internalization, comparison, appearance commentary, and feminism. Sex Roles. 2018;78:311–24.

Moreno MA, et al. Display of health risk behaviors on MySpace by adolescents: Prevalence and associations. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(1):27–34.

Yonker LM, et al. “Friending” teens: Systematic review of social media in adolescent and young adult health care. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(1): e3692.

Uhls YT, Ellison NB, Subrahmanyam K. Benefits and costs of social media in adolescence . Pediatrics, 2017;140(Supplement_2): p. S67-S70.

Cingel DP, Carter MC, Krause H-V. Social media and self-esteem. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022;45: 101304.

Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C. Connection strategies: Social capital implications of Facebook-enabled communication practices. New Media Soc. 2011;13(6):873–92.

Subrahmanyam K, Smahel D, Greenfield P. Connecting developmental constructions to the internet: Identity presentation and sexual exploration in online teen chat rooms. Dev Psychol. 2006;42(3):395.

Utz S, Breuer J. The relationship between use of social network sites, online social support, and well-being . J media psychol. 2017.

Boer M, et al. Social media use intensity, social media use problems, and mental health among adolescents: Investigating directionality and mediating processes. Comput Hum Behav. 2021;116: 106645.

• Maksniemi E, et al. Intraindividual associations between active social media use, exhaustion, and bedtime vary according to age—a longitudinal study across adolescence. J Adolesc. 2022;94(3):401–14. Longitudinally examined the relationship between SMU and sleep. A significant association was only observed in early adolescence (aged 12-14).

Levenson JC, et al. The association between social media use and sleep disturbance among young adults. Prev Med. 2016;85:36–41.

Exelmans L, Van den Bulck J. The use of media as a sleep aid in adults. Behav Sleep Med. 2016;14(2):121–33.

Fabris MA, et al. Investigating the links between fear of missing out, social media addiction, and emotional symptoms in adolescence: The role of stress associated with neglect and negative reactions on social media. Addict Behav. 2020;106: 106364.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Vannucci A, et al. Social media use and risky behaviors in adolescents: A meta-analysis. J Adolesc. 2020;79:258–74.

Gupta M, Sharma A. Fear of missing out: A brief overview of origin, theoretical underpinnings and relationship with mental health. World journal of clinical cases. 2021;9(19):4881.

Madrid-Valero, J.J., et al. Problematic technology use and sleep quality in young adulthood: Novel insights from a nationally representative twin study. Sleep. 2023:zsad038.

• Bergfeld NS, Van den Bulck J. It’s not all about the likes: Social media affordances with nighttime, problematic, and adverse use as predictors of adolescent sleep indicators. Sleep Health. 2021;7(5):548–55. Examined the influence of social media use on adolescent sleep from different dimensions (including nighttime, problematic, and adverse use).

• Brailovskaia J, et al. Social media use, mental health, and suicide-related outcomes in Russian women: A cross-sectional comparison between two age groups. Womens Health. 2022;18:17455057221141292. Measured social media time use objectively by specific screen-time applications, together with self-report questionnaires.

CAS Google Scholar

Henzel V, Håkansson A. Hooked on virtual social life. Problematic social media use and associations with mental distress and addictive disorders . PloS one, 2021;16(4):p. e0248406.

Boniel-Nissim M, et al. Adolescent use of social media and associations with sleep patterns across 18 European and North American countries. Sleep Health. 2023;9(3):314–21.

Buda G, et al. Possible effects of social media use on adolescent health behaviors and perceptions. Psychol Rep. 2021;124(3):1031–48.

van den Eijnden RJ, et al. Social media use and adolescents’ sleep: A longitudinal study on the protective role of parental rules regarding internet use before sleep. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):1346.

• Barthorpe A, et al. Is social media screen time really associated with poor adolescent mental health? A time use diary study. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:864–70. Assessed social media screen time using a prospective time use diary to provide a less biased measure of social media use.

• Beyari H. The relationship between social media and the increase in mental health problems. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(3):2383. Analysed objective social media features such as the number of likes, comments, and followers and their influence on mental health.

Khan A, et al. Associations between adolescent sleep difficulties and active versus passive screen time across 38 countries. J Affect Disord. 2023;320:298–304.

Plackett R, Sheringham J, Dykxhoorn J. The longitudinal impact of social media use on UK adolescents’ mental health: Longitudinal observational study. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25: e43213.

Gaya AR, et al. Electronic device and social network use and sleep outcomes among adolescents: The EHDLA study. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1–11.

Burnell K, et al. Associations between adolescents’ daily digital technology use and sleep. J Adolesc Health. 2022;70(3):450–6.

Kortesoja L, et al. Late-night digital media use in relation to chronotype, sleep and tiredness on school days in adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2023;52(2):419–33.

• Li TM, et al. The associations of electronic media use with sleep and circadian problems, social, emotional and behavioral difficulties in adolescents. Front Psych. 2022;13: 892583. Investigated a wide range of sleep and mental problems and their associations with social media use (in both daytime and nighttime).