- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

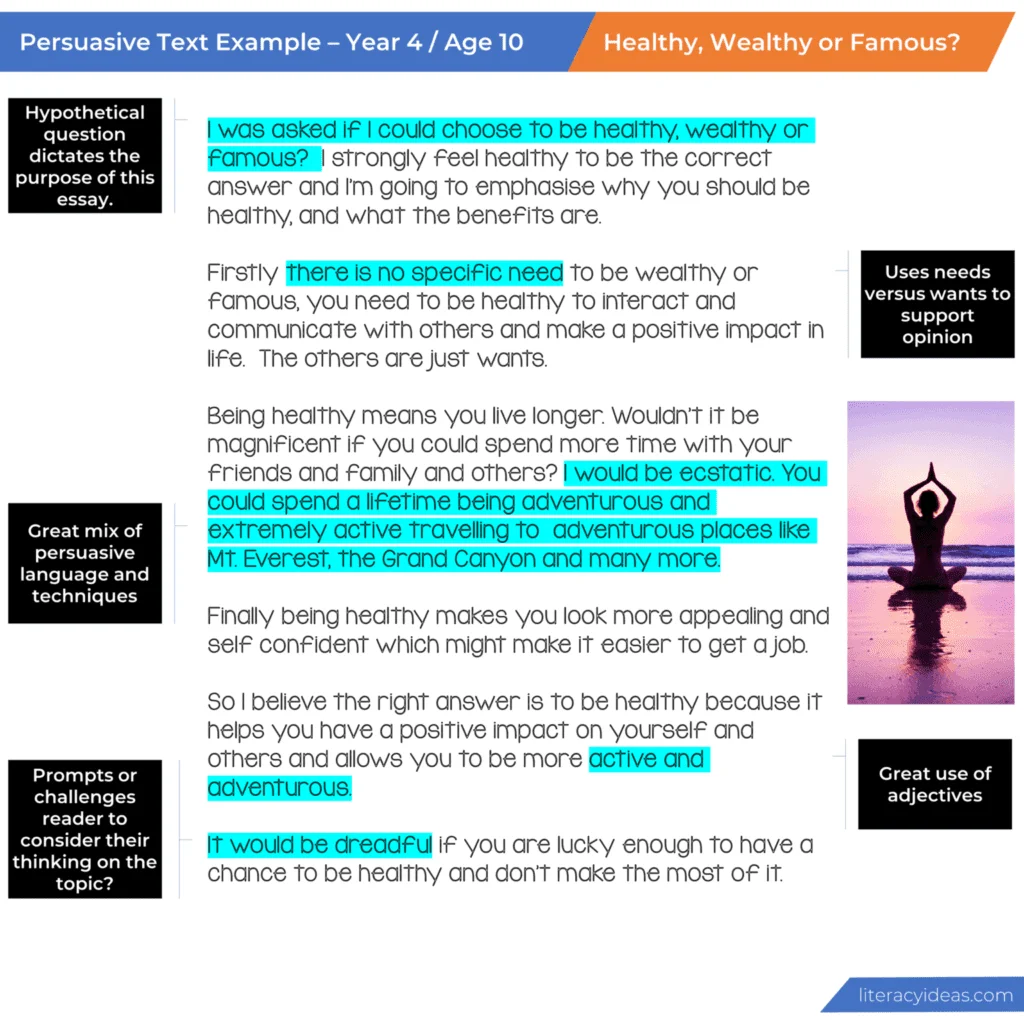

How to Write a Persuasive Essay: Tips and Tricks

Allison Bressmer

Most composition classes you’ll take will teach the art of persuasive writing. That’s a good thing.

Knowing where you stand on issues and knowing how to argue for or against something is a skill that will serve you well both inside and outside of the classroom.

Persuasion is the art of using logic to prompt audiences to change their mind or take action , and is generally seen as accomplishing that goal by appealing to emotions and feelings.

A persuasive essay is one that attempts to get a reader to agree with your perspective.

Ready for some tips on how to produce a well-written, well-rounded, well-structured persuasive essay? Just say yes. I don’t want to have to write another essay to convince you!

How Do I Write a Persuasive Essay?

What are some good topics for a persuasive essay, how do i identify an audience for my persuasive essay, how do you create an effective persuasive essay, how should i edit my persuasive essay.

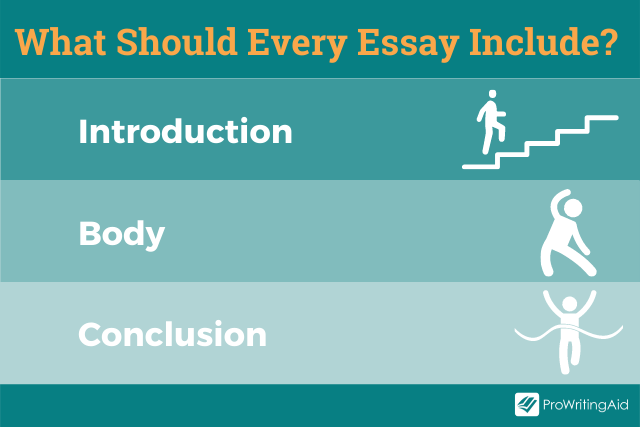

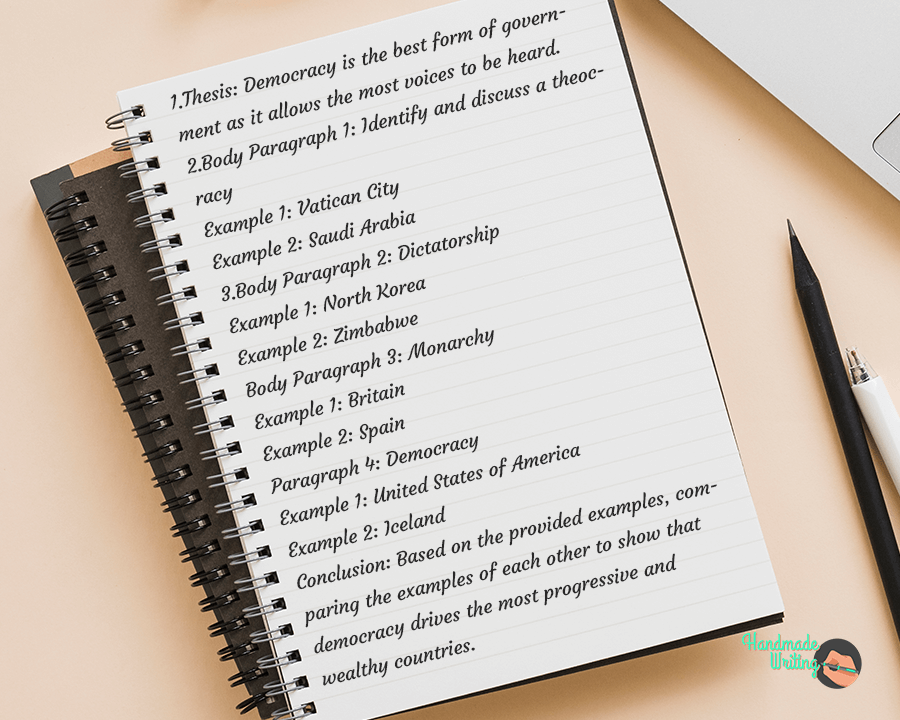

Your persuasive essay needs to have the three components required of any essay: the introduction , body , and conclusion .

That is essay structure. However, there is flexibility in that structure.

There is no rule (unless the assignment has specific rules) for how many paragraphs any of those sections need.

Although the components should be proportional; the body paragraphs will comprise most of your persuasive essay.

How Do I Start a Persuasive Essay?

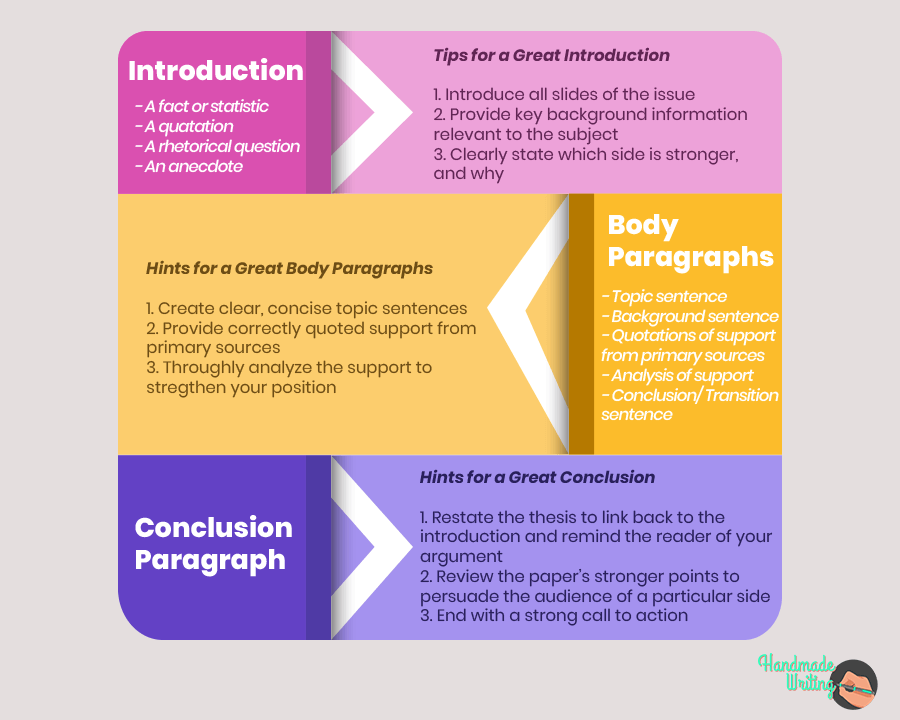

As with any essay introduction, this paragraph is where you grab your audience’s attention, provide context for the topic of discussion, and present your thesis statement.

TIP 1: Some writers find it easier to write their introductions last. As long as you have your working thesis, this is a perfectly acceptable approach. From that thesis, you can plan your body paragraphs and then go back and write your introduction.

TIP 2: Avoid “announcing” your thesis. Don’t include statements like this:

- “In my essay I will show why extinct animals should (not) be regenerated.”

- “The purpose of my essay is to argue that extinct animals should (not) be regenerated.”

Announcements take away from the originality, authority, and sophistication of your writing.

Instead, write a convincing thesis statement that answers the question "so what?" Why is the topic important, what do you think about it, and why do you think that? Be specific.

How Many Paragraphs Should a Persuasive Essay Have?

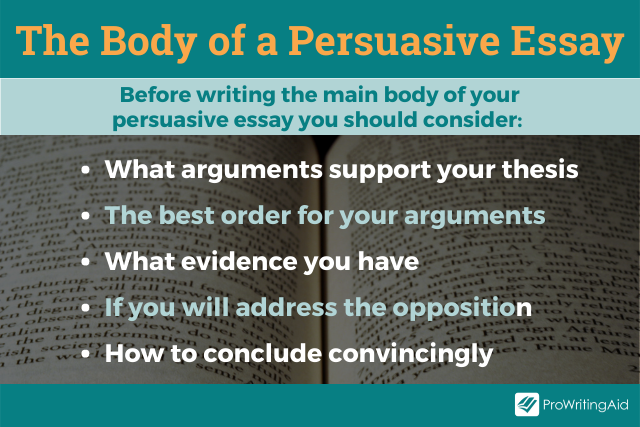

This body of your persuasive essay is the section in which you develop the arguments that support your thesis. Consider these questions as you plan this section of your essay:

- What arguments support your thesis?

- What is the best order for your arguments?

- What evidence do you have?

- Will you address the opposing argument to your own?

- How can you conclude convincingly?

TIP: Brainstorm and do your research before you decide which arguments you’ll focus on in your discussion. Make a list of possibilities and go with the ones that are strongest, that you can discuss with the most confidence, and that help you balance your rhetorical triangle .

What Should I Put in the Conclusion of a Persuasive Essay?

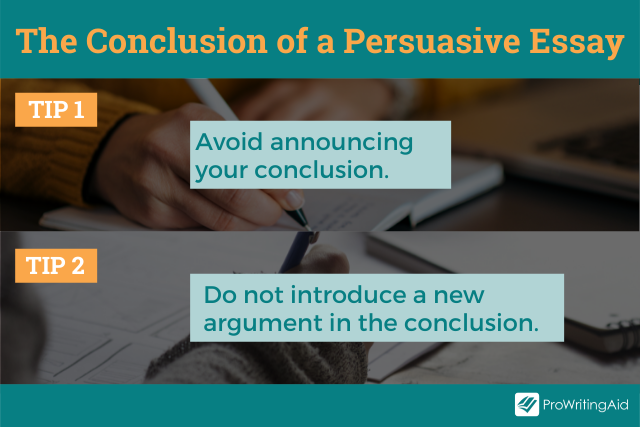

The conclusion is your “mic-drop” moment. Think about how you can leave your audience with a strong final comment.

And while a conclusion often re-emphasizes the main points of a discussion, it shouldn’t simply repeat them.

TIP 1: Be careful not to introduce a new argument in the conclusion—there’s no time to develop it now that you’ve reached the end of your discussion!

TIP 2 : As with your thesis, avoid announcing your conclusion. Don’t start your conclusion with “in conclusion” or “to conclude” or “to end my essay” type statements. Your audience should be able to see that you are bringing the discussion to a close without those overused, less sophisticated signals.

If your instructor has assigned you a topic, then you’ve already got your issue; you’ll just have to determine where you stand on the issue. Where you stand on your topic is your position on that topic.

Your position will ultimately become the thesis of your persuasive essay: the statement the rest of the essay argues for and supports, intending to convince your audience to consider your point of view.

If you have to choose your own topic, use these guidelines to help you make your selection:

- Choose an issue you truly care about

- Choose an issue that is actually debatable

Simple “tastes” (likes and dislikes) can’t really be argued. No matter how many ways someone tries to convince me that milk chocolate rules, I just won’t agree.

It’s dark chocolate or nothing as far as my tastes are concerned.

Similarly, you can’t convince a person to “like” one film more than another in an essay.

You could argue that one movie has superior qualities than another: cinematography, acting, directing, etc. but you can’t convince a person that the film really appeals to them.

Once you’ve selected your issue, determine your position just as you would for an assigned topic. That position will ultimately become your thesis.

Until you’ve finalized your work, consider your thesis a “working thesis.”

This means that your statement represents your position, but you might change its phrasing or structure for that final version.

When you’re writing an essay for a class, it can seem strange to identify an audience—isn’t the audience the instructor?

Your instructor will read and evaluate your essay, and may be part of your greater audience, but you shouldn’t just write for your teacher.

Think about who your intended audience is.

For an argument essay, think of your audience as the people who disagree with you—the people who need convincing.

That population could be quite broad, for example, if you’re arguing a political issue, or narrow, if you’re trying to convince your parents to extend your curfew.

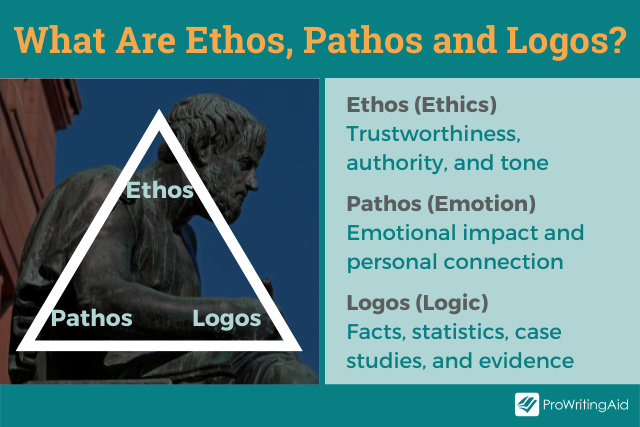

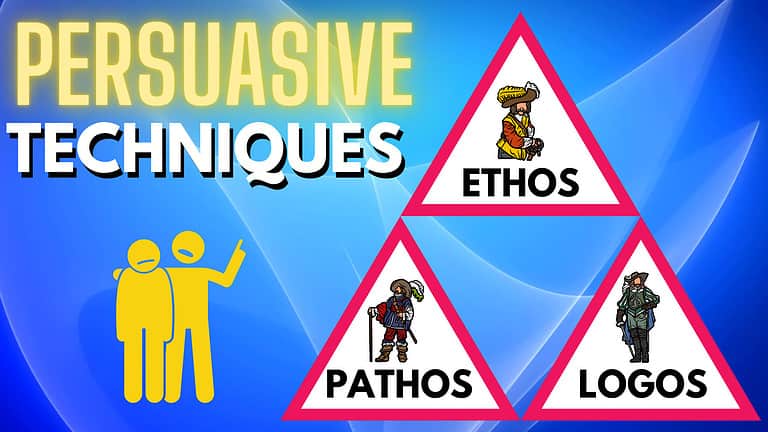

Once you’ve got a sense of your audience, it’s time to consult with Aristotle. Aristotle’s teaching on persuasion has shaped communication since about 330 BC. Apparently, it works.

Aristotle taught that in order to convince an audience of something, the communicator needs to balance the three elements of the rhetorical triangle to achieve the best results.

Those three elements are ethos , logos , and pathos .

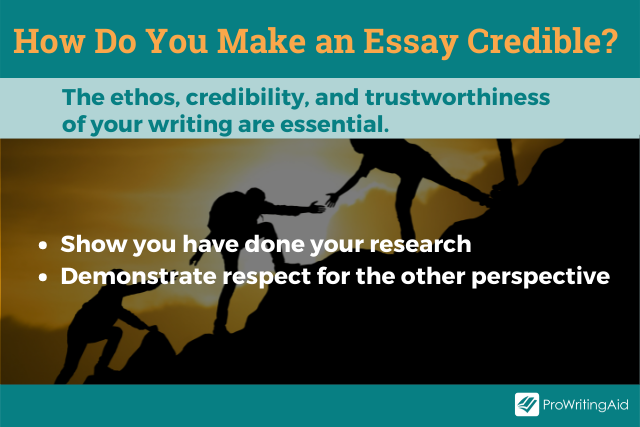

Ethos relates to credibility and trustworthiness. How can you, as the writer, demonstrate your credibility as a source of information to your audience?

How will you show them you are worthy of their trust?

- You show you’ve done your research: you understand the issue, both sides

- You show respect for the opposing side: if you disrespect your audience, they won’t respect you or your ideas

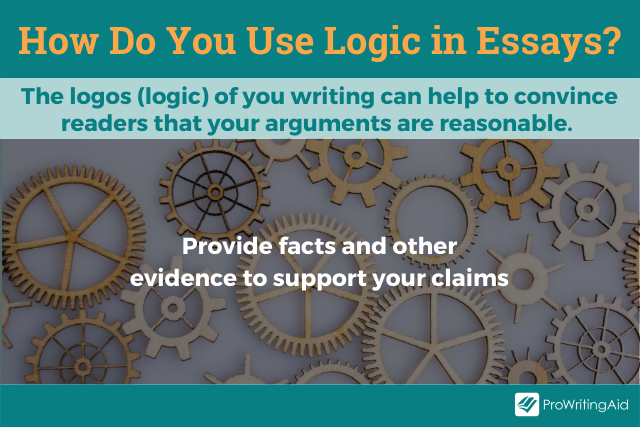

Logos relates to logic. How will you convince your audience that your arguments and ideas are reasonable?

You provide facts or other supporting evidence to support your claims.

That evidence may take the form of studies or expert input or reasonable examples or a combination of all of those things, depending on the specific requirements of your assignment.

Remember: if you use someone else’s ideas or words in your essay, you need to give them credit.

ProWritingAid's Plagiarism Checker checks your work against over a billion web-pages, published works, and academic papers so you can be sure of its originality.

Find out more about ProWritingAid’s Plagiarism checks.

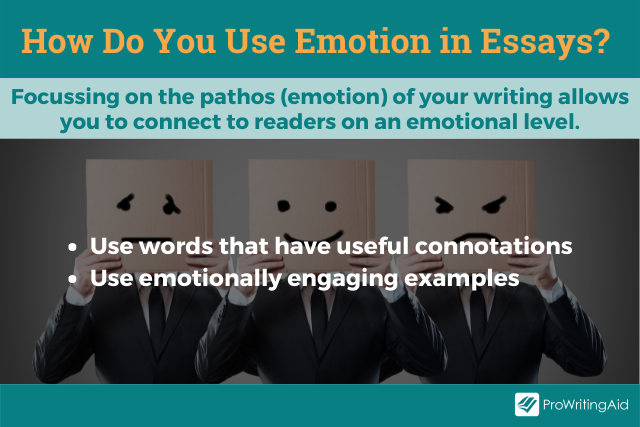

Pathos relates to emotion. Audiences are people and people are emotional beings. We respond to emotional prompts. How will you engage your audience with your arguments on an emotional level?

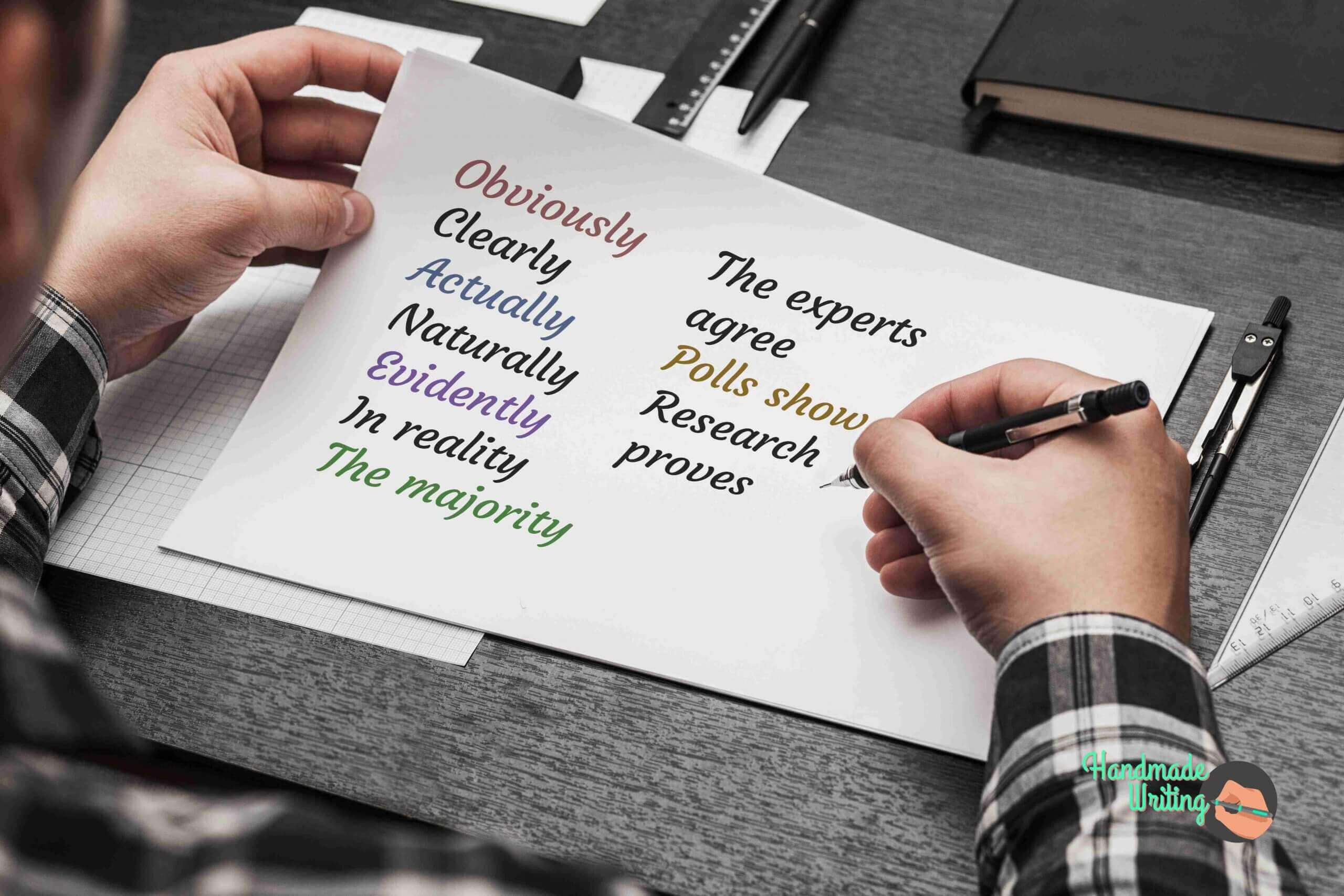

- You make strategic word choices : words have denotations (dictionary meanings) and also connotations, or emotional values. Use words whose connotations will help prompt the feelings you want your audience to experience.

- You use emotionally engaging examples to support your claims or make a point, prompting your audience to be moved by your discussion.

Be mindful as you lean into elements of the triangle. Too much pathos and your audience might end up feeling manipulated, roll their eyes and move on.

An “all logos” approach will leave your essay dry and without a sense of voice; it will probably bore your audience rather than make them care.

Once you’ve got your essay planned, start writing! Don’t worry about perfection, just get your ideas out of your head and off your list and into a rough essay format.

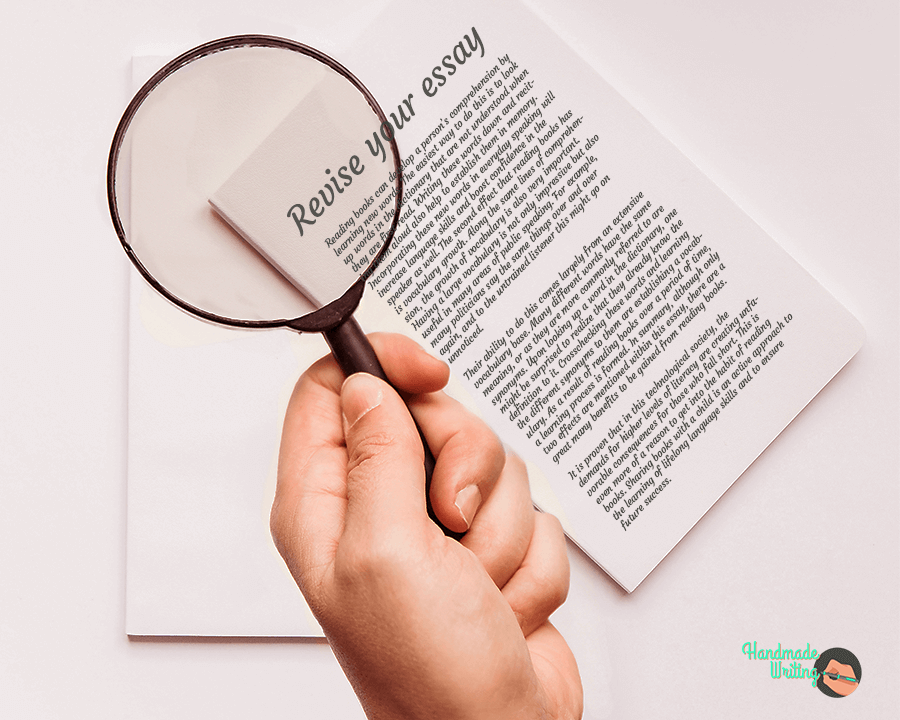

After you’ve written your draft, evaluate your work. What works and what doesn’t? For help with evaluating and revising your work, check out this ProWritingAid post on manuscript revision .

After you’ve evaluated your draft, revise it. Repeat that process as many times as you need to make your work the best it can be.

When you’re satisfied with the content and structure of the essay, take it through the editing process .

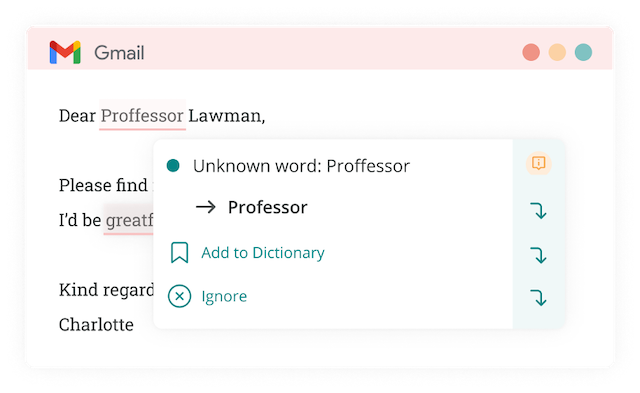

Grammatical or sentence-level errors can distract your audience or even detract from the ethos—the authority—of your work.

You don’t have to edit alone! ProWritingAid’s Realtime Report will find errors and make suggestions for improvements.

You can even use it on emails to your professors:

Try ProWritingAid with a free account.

How Can I Improve My Persuasion Skills?

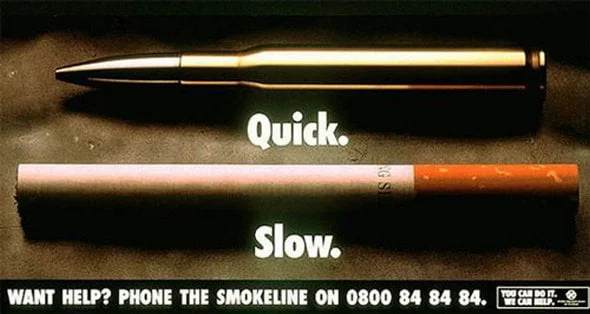

You can develop your powers of persuasion every day just by observing what’s around you.

- How is that advertisement working to convince you to buy a product?

- How is a political candidate arguing for you to vote for them?

- How do you “argue” with friends about what to do over the weekend, or convince your boss to give you a raise?

- How are your parents working to convince you to follow a certain academic or career path?

As you observe these arguments in action, evaluate them. Why are they effective or why do they fail?

How could an argument be strengthened with more (or less) emphasis on ethos, logos, and pathos?

Every argument is an opportunity to learn! Observe them, evaluate them, and use them to perfect your own powers of persuasion.

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Allison Bressmer is a professor of freshman composition and critical reading at a community college and a freelance writer. If she isn’t writing or teaching, you’ll likely find her reading a book or listening to a podcast while happily sipping a semi-sweet iced tea or happy-houring with friends. She lives in New York with her family. Connect at linkedin.com/in/allisonbressmer.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

How to Write a Persuasive Essay (This Convinced My Professor!)

.png)

Table of contents

Meredith Sell

You can make your essay more persuasive by getting straight to the point.

In fact, that's exactly what we did here, and that's just the first tip of this guide. Throughout this guide, we share the steps needed to prove an argument and create a persuasive essay.

This AI tool helps you improve your essay > This AI tool helps you improve your essay >

Key takeaways: - Proven process to make any argument persuasive - 5-step process to structure arguments - How to use AI to formulate and optimize your essay

Why is being persuasive so difficult?

"Write an essay that persuades the reader of your opinion on a topic of your choice."

You might be staring at an assignment description just like this 👆from your professor. Your computer is open to a blank document, the cursor blinking impatiently. Do I even have opinions?

The persuasive essay can be one of the most intimidating academic papers to write: not only do you need to identify a narrow topic and research it, but you also have to come up with a position on that topic that you can back up with research while simultaneously addressing different viewpoints.

That’s a big ask. And let’s be real: most opinion pieces in major news publications don’t fulfill these requirements.

The upside? By researching and writing your own opinion, you can learn how to better formulate not only an argument but the actual positions you decide to hold.

Here, we break down exactly how to write a persuasive essay. We’ll start by taking a step that’s key for every piece of writing—defining the terms.

What Is a Persuasive Essay?

A persuasive essay is exactly what it sounds like: an essay that persuades . Over the course of several paragraphs or pages, you’ll use researched facts and logic to convince the reader of your opinion on a particular topic and discredit opposing opinions.

While you’ll spend some time explaining the topic or issue in question, most of your essay will flesh out your viewpoint and the evidence that supports it.

The 5 Must-Have Steps of a Persuasive Essay

If you’re intimidated by the idea of writing an argument, use this list to break your process into manageable chunks. Tackle researching and writing one element at a time, and then revise your essay so that it flows smoothly and coherently with every component in the optimal place.

1. A topic or issue to argue

This is probably the hardest step. You need to identify a topic or issue that is narrow enough to cover in the length of your piece—and is also arguable from more than one position. Your topic must call for an opinion , and not be a simple fact .

It might be helpful to walk through this process:

- Identify a random topic

- Ask a question about the topic that involves a value claim or analysis to answer

- Answer the question

That answer is your opinion.

Let’s consider some examples, from silly to serious:

Topic: Dolphins and mermaids

Question: In a mythical match, who would win: a dolphin or a mermaid?

Answer/Opinion: The mermaid would win in a match against a dolphin.

Topic: Autumn

Question: Which has a better fall: New England or Colorado?

Answer/Opinion: Fall is better in New England than Colorado.

Topic: Electric transportation options

Question: Would it be better for an urban dweller to buy an electric bike or an electric car?

Answer/Opinion: An electric bike is a better investment than an electric car.

Your turn: Walk through the three-step process described above to identify your topic and your tentative opinion. You may want to start by brainstorming a list of topics you find interesting and then going use the three-step process to find the opinion that would make the best essay topic.

2. An unequivocal thesis statement

If you walked through our three-step process above, you already have some semblance of a thesis—but don’t get attached too soon!

A solid essay thesis is best developed through the research process. You shouldn’t land on an opinion before you know the facts. So press pause. Take a step back. And dive into your research.

You’ll want to learn:

- The basic facts of your topic. How long does fall last in New England vs. Colorado? What trees do they have? What colors do those trees turn?

- The facts specifically relevant to your question. Is there any science on how the varying colors of fall influence human brains and moods?

- What experts or other noteworthy and valid sources say about the question you’re considering. Has a well-known arborist waxed eloquent on the beauty of New England falls?

As you learn the different viewpoints people have on your topic, pay attention to the strengths and weaknesses of existing arguments. Is anyone arguing the perspective you’re leaning toward? Do you find their arguments convincing? What do you find unsatisfying about the various arguments?

Allow the research process to change your mind and/or refine your thinking on the topic. Your opinion may change entirely or become more specific based on what you learn.

Once you’ve done enough research to feel confident in your understanding of the topic and your opinion on it, craft your thesis.

Your thesis statement should be clear and concise. It should directly state your viewpoint on the topic, as well as the basic case for your thesis.

Thesis 1: In a mythical match, the mermaid would overcome the dolphin due to one distinct advantage: her ability to breathe underwater.

Thesis 2: The full spectrum of color displayed on New England hillsides is just one reason why fall in the northeast is better than in Colorado.

Thesis 3: In addition to not adding to vehicle traffic, electric bikes are a better investment than electric cars because they’re cheaper and require less energy to accomplish the same function of getting the rider from point A to point B.

Your turn: Dive into the research process with a radar up for the arguments your sources are making about your topic. What are the most convincing cases? Should you stick with your initial opinion or change it up? Write your fleshed-out thesis statement.

3. Evidence to back up your thesis

This is a typical place for everyone from undergrads to politicians to get stuck, but the good news is, if you developed your thesis from research, you already have a good bit of evidence to make your case.

Go back through your research notes and compile a list of every …

… or other piece of information that supports your thesis.

This info can come from research studies you found in scholarly journals, government publications, news sources, encyclopedias, or other credible sources (as long as they fit your professor’s standards).

As you put this list together, watch for any gaps or weak points. Are you missing information on how electric cars versus electric bicycles charge or how long their batteries last? Did you verify that dolphins are, in fact, mammals and can’t breathe underwater like totally-real-and-not-at-all-fake 😉mermaids can? Track down that information.

Next, organize your list. Group the entries so that similar or closely related information is together, and as you do that, start thinking through how to articulate the individual arguments to support your case.

Depending on the length of your essay, each argument may get only a paragraph or two of space. As you think through those specific arguments, consider what order to put them in. You’ll probably want to start with the simplest argument and work up to more complicated ones so that the arguments can build on each other.

Your turn: Organize your evidence and write a rough draft of your arguments. Play around with the order to find the most compelling way to argue your case.

4. Rebuttals to disprove opposing theses

You can’t just present the evidence to support your case and totally ignore other viewpoints. To persuade your readers, you’ll need to address any opposing ideas they may hold about your topic.

You probably found some holes in the opposing views during your research process. Now’s your chance to expose those holes.

Take some time (and space) to: describe the opposing views and show why those views don’t hold up. You can accomplish this using both logic and facts.

Is a perspective based on a faulty assumption or misconception of the truth? Shoot it down by providing the facts that disprove the opinion.

Is another opinion drawn from bad or unsound reasoning? Show how that argument falls apart.

Some cases may truly be only a matter of opinion, but you still need to articulate why you don’t find the opposing perspective convincing.

Yes, a dolphin might be stronger than a mermaid, but as a mammal, the dolphin must continually return to the surface for air. A mermaid can breathe both underwater and above water, which gives her a distinct advantage in this mythical battle.

While the Rocky Mountain views are stunning, their limited colors—yellow from aspen trees and green from various evergreens—leaves the autumn-lover less than thrilled. The rich reds and oranges and yellows of the New England fall are more satisfying and awe-inspiring.

But what about longer trips that go beyond the city center into the suburbs and beyond? An electric bike wouldn’t be great for those excursions. Wouldn’t an electric car be the better choice then?

Certainly, an electric car would be better in these cases than a gas-powered car, but if most of a person’s trips are in their hyper-local area, the electric bicycle is a more environmentally friendly option for those day-to-day outings. That person could then participate in a carshare or use public transit, a ride-sharing app, or even a gas-powered car for longer trips—and still use less energy overall than if they drove an electric car for hyper-local and longer area trips.

Your turn: Organize your rebuttal research and write a draft of each one.

5. A convincing conclusion

You have your arguments and rebuttals. You’ve proven your thesis is rock-solid. Now all you have to do is sum up your overall case and give your final word on the subject.

Don’t repeat everything you’ve already said. Instead, your conclusion should logically draw from the arguments you’ve made to show how they coherently prove your thesis. You’re pulling everything together and zooming back out with a better understanding of the what and why of your thesis.

A dolphin may never encounter a mermaid in the wild, but if it were to happen, we know how we’d place our bets. Long hair and fish tail, for the win.

For those of us who relish 50-degree days, sharp air, and the vibrant colors of fall, New England offers a season that’s cozier, longer-lasting, and more aesthetically pleasing than “colorful” Colorado. A leaf-peeper’s paradise.

When most of your trips from day to day are within five miles, the more energy-efficient—and yes, cost-efficient—choice is undoubtedly the electric bike. So strap on your helmet, fire up your pedals, and two-wheel away to your next destination with full confidence that you made the right decision for your wallet and the environment.

3 Quick Tips for Writing a Strong Argument

Once you have a draft to work with, use these tips to refine your argument and make sure you’re not losing readers for avoidable reasons.

1. Choose your words thoughtfully.

If you want to win people over to your side, don’t write in a way that shuts your opponents down. Avoid making abrasive or offensive statements. Instead, use a measured, reasonable tone. Appeal to shared values, and let your facts and logic do the hard work of changing people’s minds.

Choose words with AI

You can use AI to turn your general point into a readable argument. Then, you can paraphrase each sentence and choose between competing arguments generated by the AI, until your argument is well-articulated and concise.

2. Prioritize accuracy (and avoid fallacies).

Make sure the facts you use are actually factual. You don’t want to build your argument on false or disproven information. Use the most recent, respected research. Make sure you don’t misconstrue study findings. And when you’re building your case, avoid logical fallacies that undercut your argument.

A few common fallacies to watch out for:

- Strawman: Misrepresenting or oversimplifying an opposing argument to make it easier to refute.

- Appeal to ignorance: Arguing that a certain claim must be true because it hasn’t been proven false.

- Bandwagon: Assumes that if a group of people, experts, etc., agree with a claim, it must be true.

- Hasty generalization: Using a few examples, rather than substantial evidence, to make a sweeping claim.

- Appeal to authority: Overly relying on opinions of people who have authority of some kind.

The strongest arguments rely on trustworthy information and sound logic.

Research and add citations with AI

We recently wrote a three part piece on researching using AI, so be sure to check it out . Going through an organized process of researching and noting your sources correctly will make sure your written text is more accurate.

3. Persuasive essay structure

If you’re building a house, you start with the foundation and go from there. It’s the same with an argument. You want to build from the ground up: provide necessary background information, then your thesis. Then, start with the simplest part of your argument and build up in terms of complexity and the aspect of your thesis that the argument is tackling.

A consistent, internal logic will make it easier for the reader to follow your argument. Plus, you’ll avoid confusing your reader and you won’t be unnecessarily redundant.

The essay structure usually includes the following parts:

- Intro - Hook, Background information, Thesis statement

- Topic sentence #1 , with supporting facts or stats

- Concluding sentence

- Topic sentence #2 , with supporting facts or stats

- Concluding sentence Topic sentence #3 , with supporting facts or stats

- Conclusion - Thesis and main points restated, call to action, thought provoking ending

Are You Ready to Write?

Persuasive essays are a great way to hone your research, writing, and critical thinking skills. Approach this assignment well, and you’ll learn how to form opinions based on information (not just ideas) and make arguments that—if they don’t change minds—at least win readers’ respect.

Share This Article:

The Official Wordtune Guide

An Expert Guide to Writing Effective Compound Sentences (+ Examples)

A Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Stellar Literature Review (with Help from AI)

Looking for fresh content, thank you your submission has been received.

How to Write a Persuasive Essay: Step-by-Step Guide + Examples

Have you ever tried to get somebody round to your way of thinking? Then you should know how daunting the task is. Still, if your persuasion is successful, the result is emotionally rewarding.

Our specialists will write a custom essay specially for you!

A persuasive essay is a type of writing that uses facts and logic to argument and substantiate such or another point of view. The purpose is to assure the reader that the author’s position is viable. In this article by Custom-writing experts, you can find a guide on persuasive writing, compelling examples, and outline structure. Continue reading and learn how to write a persuasive essay!

⚖️ Argumentative vs. Persuasive Essay

- 🐾 Step-by-Step Writing Guide

🔗 References

An argumentative essay intends to attack the opposing point of view, discussing its drawbacks and inconsistencies. A persuasive essay describes only the writer’s opinion, explaining why it is a believable one. In other words, you are not an opponent; you are an advocate.

A persuasive essay primarily resorts to emotions and personal ideas on a deeper level of meaning, while an argumentative one invokes logic reasoning. Despite the superficial similarity of these two genres, argumentative speech presupposes intense research of the subject, while persuasive speech requires a good knowledge of the audience.

🐾 How to Write a Persuasive Essay Step by Step

These nine steps are the closest thing you will find to a shortcut for writing to persuade. With practice, you may get through these steps quickly—or even figure out new techniques in persuasive writing.

📑 Persuasive Essay Outline

Below you’ll find an example of a persuasive essay outline . Remember: papers in this genre are more flexible than argumentative essays are. You don’t need to build a perfectly logical structure here. Your goal is to persuade your reader.

Just in 1 hour! We will write you a plagiarism-free paper in hardly more than 1 hour

Note that the next section contains a sample written in accordance with this outline.

Persuasive Essay Introduction

- Hook: start with an intriguing sentence.

- Background: describe the context of the discussed issue and familiarize the reader with the argument.

- Definitions: if your essay dwells upon a theoretical subject matter, be sure to explain the complicated terms.

- Thesis statement: state the purpose of your piece of writing clearly and concisely. This is the most substantial sentence of the entire essay, so take your time formulating it.

Persuasive Essay Body

Use the following template for each paragraph.

- Topic sentence: linking each new idea to the thesis, it introduces a paragraph. Use only one separate argument for each section, stating it in the topic sentence.

- Evidence: substantiate the previous sentence with reliable information. If it is your personal opinion, give the reasons why you think so.

- Analysis: build the argument, explaining how the evidence supports your thesis.

Persuasive Essay Conclusion

- Summary: briefly list the main points of the essay in a couple of sentences.

- Significance: connect your essay to a broader idea.

- Future: how can your argument be developed?

⭐ Persuasive Essay Examples

In this section, there are three great persuasive essay examples. The first one is written in accordance with the outline above, will the components indicated. Two others are downloadable.

Example #1: Being a Millionaire is a Bad Thing

Introduction, paragraph #1, paragraph #2, paragraph #3, example #2: teachers or doctors.

The importance of doctors in the period of the COVID-19 pandemic is difficult to overstate. The well-being of the nation depends on how well doctors can fulfill their duties before society. The US society acknowledges the importance of doctors and healthcare, as it is ready to pay large sums of money to cure the diseases. However, during the lockdown, students and parents all around the world began to understand the importance of teachers.

Before lockdown, everyone took the presence of teachers for granted, as they were always available free of charge. In this country, it has always been the case that while doctors received praises and monetary benefits, teachers remained humble, even though they play the most important role for humanity: passing the knowledge through generations. How fair is that? The present paper claims that even in the period of the pandemic, teachers contribute more to modern society than doctors do.

Example #3: Is Online or Homeschool More Effective?

The learning process can be divided into traditional education in an educational institution and distance learning. The latter form has recently become widely popular due to the development of technology. Besides, the COVID-19 pandemic is driving the increased interest in distance learning. However, there is controversy about whether this form of training is sufficient enough. This essay aims to examine online and homeschooling in a historical and contemporary context and to confirm the thesis that such activity is at least equivalent to a standard type of education.

Persuasive Essay Topics

- Why do managers hate the performance evaluation?

- Why human cloning should be prohibited.

- Social media have negative physical and psychological effect on teenagers.

- Using cell phones while driving should be completely forbidden.

- Why is business ethics important?

- Media should change its negative representation of ageing and older people.

- What is going on with the world?

- Good communication skills are critical for successful business.

- Why capitalism is the best economic system.

- Sleep is extremely important for human health and wellbeing.

- Face-to-face education is more effective than online education.

- Why video games can be beneficial for teenagers.

- Bullies should be expelled from school as they encroach on the school safety.

- Why accountancy is a great occupation and more people should consider it as a future career.

- The reasons art and music therapy should be included in basic health insurance.

- Impact of climate change on the indoor environment.

- Parents should vaccinate their children to prevent the spread of deadly diseases.

- Why celebrities should pay more attention to the values they promote.

- What is wrong with realism?

- Why water recycling should be every government’s priority.

- Media spreads fear and panic among people.

- Why e-business is very important for modern organizations.

- People should own guns for self-protection.

- The neccessity of container deposit legislation.

- We must save crocodiles to protect ecological balance.

- Why we should pay more attention to renewable energy projects.

- Anthropology is a critically relevant science.

- Why it’s important to create a new global financial order .

- Why biodiversity is crucial for the environment?

- Why process safety management is crucial for every organization.

- Speed limits must not be increased.

- What’s wrong with grades at school ?

- Why tattoos should be considered as a form of fine art.

- Using all-natural bath and body products is the best choice for human health and safety.

- What is cancel culture?

- Why the Internet has become a problem of modern society.

- Illegal immigrants should be provided with basic social services.

- Smoking in public places must be banned for people’s safety and comfort.

- Why it is essential to control our nutrition .

- How to stimulate economic growth?

- Why exercise is beneficial for people.

- Studying history is decisive for the modern world.

- We must decrease fuel consumption to stop global warming.

- Why fighting social inequality is necessary.

- Why should businesses welcome remote work?

- Social media harms communication within families.

- College athletes should be paid for their achievements.

- Electronic books should replace print books.

- People should stop cutting down rainforest .

- Why every company should have a web page .

- Tips To Write An Effective Persuasive Essay: The College Puzzle, Stanford University

- 31 Powerful Persuasive Writing Techniques: Writtent

- Persuasive Essay Outline: Houston Community College System

- Essays that Worked: Hamilton College

- Argumentative Essays // Purdue Writing Lab

- Persuasion – Writing for Success (University of Minnesota)

- Persuasive Writing (Manitoba Education)

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to email

![steps on writing a persuasive essay Common Essay Mistakes—Writing Errors to Avoid [Updated]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/avoid-mistakes-ccw-284x153.jpg)

One of the most critical skills that students gain during their college years is assignment writing. Composing impressive essays and research papers can be quite challenging, especially for ESL students. Nonetheless, before learning the art of academic writing, you may make numerous common essay mistakes. Such involuntary errors appear in:...

You’re probably thinking: I’m no Mahatma Gandhi or Steve Jobs—what could I possibly write in my memoir? I don’t even know how to start an autobiography, let alone write the whole thing. But don’t worry: essay writing can be easy, and this autobiography example for students is here to show...

![steps on writing a persuasive essay Why I Want to Be a Teacher Essay: Writing Guide [2024]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/senior-male-professor-writing-blackboard-with-chalk3-284x153.jpg)

Some people know which profession to choose from childhood, while others decide much later in life. However, and whenever you come to it, you may have to elaborate on it in your personal statement or cover letter. This is widely known as “Why I Want to Be a Teacher” essay.

![steps on writing a persuasive essay Friendship Essay: Writing Guide & Topics on Friendship [New]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/smiley-female-friends-fist-bumping-284x153.jpg)

Assigned with an essay about friendship? Congrats! It’s one of the best tasks you could get. Digging through your memories and finding strong arguments for this paper can be an enjoyable experience. I bet you will cope with this task effortlessly as we can help you with the assignment. Just...

When you are assigned an autobiography to write, tens, and even hundreds of questions start buzzing in your head. How to write autobiography essay parts? What to include? How to make your autobiography writing flow? Don’t worry about all this and use the following three simple principles and 15 creative...

“Where is your thesis statement?” asks your teacher in a dramatic tone. “Where is my what?” you want to reply, but instead, you quickly point your finger at a random sentence in your paper, saying, “Here it is…” To avoid this sad situation (which is usually followed by a bad...

A life experience essay combines the elements of narration, description, and self-reflection. Such a paper has to focus on a single event that had a significant impact on a person’s worldview and values. Writing an essay about life experience prompts students to do the following: evaluate their behavior in specific...

Who has made a significant impact in your life and why? Essay on the topic might be challenging to write. One is usually asked to write such a text as a college admission essay. A topic for this paper can be of your choice or pre-established by the institution. Either...

Are you about to start writing a financial assistance essay? Most probably, you are applying for a scholarship that will provide additional funding for your education or that will help you meet some special research objectives.

![steps on writing a persuasive essay Growing Up Essay: Guide & Examples [2024]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/gardening-concept-with-mother-daughter-284x153.jpg)

What does it mean to grow up? Essays on this topic might be entertaining yet challenging to write. Growing up is usually associated with something new and exciting. It’s a period of everything new and unknown. Now, you’ve been assigned to write a growing up essay. You’re not a kid...

![steps on writing a persuasive essay Murder Essay: Examples, Topics, and Killer Tips [2024]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/man-holding-gun-as-evidence-284x153.jpeg)

Probably, a murder essay is not a fascinating assignment to complete. Talking about people’s deaths or crazy murderers can be depressing. However, all assignments are different, and you are supposed to work on every task hard. So, how are you going to deal with a murder essay? You can make...

Are you a nursing student? Then, you will definitely have an assignment to compose a nursing reflective essay. This task might be quite tough and challenging. But don’t stress out! Our professionals are willing to assist you.

Thank you for posting this!! I am trying to get notice to bring up a new language in our school because it doesn’t allow many languages so this really helped 🙂

I’m happy you found the article helpful, Allie. Thank you for your feedback!

Beautiful content

Thanks, Frances!

Useful article for blogging. I believe, for business, these blog tips will help me a lot.

Glad to know our tips are helpful for you! Hope you visit our blog again!

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Write a Persuasive Essay

Last Updated: December 17, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD . Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014. There are 14 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 4,275,008 times.

A persuasive essay is an essay used to convince a reader about a particular idea or focus, usually one that you believe in. Your persuasive essay could be based on anything about which you have an opinion or that you can make a clear argument about. Whether you're arguing against junk food at school or petitioning for a raise from your boss, knowing how to write a persuasive essay is an important skill that everyone should have.

Sample Persuasive Essays

How to Lay the Groundwork

- Look for language that gives you a clue as to whether you are writing a purely persuasive or an argumentative essay. For example, if the prompt uses words like “personal experience” or “personal observations,” you know that these things can be used to support your argument.

- On the other hand, words like “defend” or “argue” suggest that you should be writing an argumentative essay, which may require more formal, less personal evidence.

- If you aren’t sure about what you’re supposed to write, ask your instructor.

- Whenever possible, start early. This way, even if you have emergencies like a computer meltdown, you’ve given yourself enough time to complete your essay.

- Try using stasis theory to help you examine the rhetorical situation. This is when you look at the facts, definition (meaning of the issue or the nature of it), quality (the level of seriousness of the issue), and policy (plan of action for the issue).

- To look at the facts, try asking: What happened? What are the known facts? How did this issue begin? What can people do to change the situation?

- To look at the definition, ask: What is the nature of this issue or problem? What type of problem is this? What category or class would this problem fit into best?

- To examine the quality, ask: Who is affected by this problem? How serious is it? What might happen if it is not resolved?

- To examine the policy, ask: Should someone take action? Who should do something and what should they do?

- For example, if you are arguing against unhealthy school lunches, you might take very different approaches depending on whom you want to convince. You might target the school administrators, in which case you could make a case about student productivity and healthy food. If you targeted students’ parents, you might make a case about their children’s health and the potential costs of healthcare to treat conditions caused by unhealthy food. And if you were to consider a “grassroots” movement among your fellow students, you’d probably make appeals based on personal preferences.

- It also should present the organization of your essay. Don’t list your points in one order and then discuss them in a different order.

- For example, a thesis statement could look like this: “Although pre-prepared and highly processed foods are cheap, they aren’t good for students. It is important for schools to provide fresh, healthy meals to students, even when they cost more. Healthy school lunches can make a huge difference in students’ lives, and not offering healthy lunches fails students.”

- Note that this thesis statement isn’t a three-prong thesis. You don’t have to state every sub-point you will make in your thesis (unless your prompt or assignment says to). You do need to convey exactly what you will argue.

- A mind map could be helpful. Start with your central topic and draw a box around it. Then, arrange other ideas you think of in smaller bubbles around it. Connect the bubbles to reveal patterns and identify how ideas relate. [5] X Research source

- Don’t worry about having fully fleshed-out ideas at this stage. Generating ideas is the most important step here.

- For example, if you’re arguing for healthier school lunches, you could make a point that fresh, natural food tastes better. This is a personal opinion and doesn’t need research to support it. However, if you wanted to argue that fresh food has more vitamins and nutrients than processed food, you’d need a reliable source to support that claim.

- If you have a librarian available, consult with him or her! Librarians are an excellent resource to help guide you to credible research.

How to Draft Your Essay

- An introduction. You should present a “hook” here that grabs your audience’s attention. You should also provide your thesis statement, which is a clear statement of what you will argue or attempt to convince the reader of.

- Body paragraphs. In 5-paragraph essays, you’ll have 3 body paragraphs. In other essays, you can have as many paragraphs as you need to make your argument. Regardless of their number, each body paragraph needs to focus on one main idea and provide evidence to support it. These paragraphs are also where you refute any counterpoints that you’ve discovered.

- Conclusion. Your conclusion is where you tie it all together. It can include an appeal to emotions, reiterate the most compelling evidence, or expand the relevance of your initial idea to a broader context. Because your purpose is to persuade your readers to do/think something, end with a call to action. Connect your focused topic to the broader world.

- For example, you could start an essay on the necessity of pursuing alternative energy sources like this: “Imagine a world without polar bears.” This is a vivid statement that draws on something that many readers are familiar with and enjoy (polar bears). It also encourages the reader to continue reading to learn why they should imagine this world.

- You may find that you don’t immediately have a hook. Don’t get stuck on this step! You can always press on and come back to it after you’ve drafted your essay.

- Put your hook first. Then, proceed to move from general ideas to specific ideas until you have built up to your thesis statement.

- Don't slack on your thesis statement . Your thesis statement is a short summary of what you're arguing for. It's usually one sentence, and it's near the end of your introductory paragraph. Make your thesis a combination of your most persuasive arguments, or a single powerful argument, for the best effect.

- Start with a clear topic sentence that introduces the main point of your paragraph.

- Make your evidence clear and precise. For example, don't just say: "Dolphins are very smart animals. They are widely recognized as being incredibly smart." Instead, say: "Dolphins are very smart animals. Multiple studies found that dolphins worked in tandem with humans to catch prey. Very few, if any, species have developed mutually symbiotic relationships with humans."

- "The South, which accounts for 80% of all executions in the United States, still has the country's highest murder rate. This makes a case against the death penalty working as a deterrent."

- "Additionally, states without the death penalty have fewer murders. If the death penalty were indeed a deterrent, why wouldn't we see an increase in murders in states without the death penalty?"

- Consider how your body paragraphs flow together. You want to make sure that your argument feels like it's building, one point upon another, rather than feeling scattered.

- End of the first paragraph: "If the death penalty consistently fails to deter crime, and crime is at an all-time high, what happens when someone is wrongfully convicted?"

- Beginning of the second paragraph: "Over 100 wrongfully convicted death row inmates have been acquitted of their crimes, some just minutes before their would-be death."

- Example: "Critics of a policy allowing students to bring snacks into the classroom say that it would create too much distraction, reducing students’ ability to learn. However, consider the fact that middle schoolers are growing at an incredible rate. Their bodies need energy, and their minds may become fatigued if they go for long periods without eating. Allowing snacks in the classroom will actually increase students’ ability to focus by taking away the distraction of hunger.”

- You may even find it effective to begin your paragraph with the counterargument, then follow by refuting it and offering your own argument.

- How could this argument be applied to a broader context?

- Why does this argument or opinion mean something to me?

- What further questions has my argument raised?

- What action could readers take after reading my essay?

How to Write Persuasively

- Persuasive essays, like argumentative essays, use rhetorical devices to persuade their readers. In persuasive essays, you generally have more freedom to make appeals to emotion (pathos), in addition to logic and data (logos) and credibility (ethos). [13] X Trustworthy Source Read Write Think Online collection of reading and writing resources for teachers and students. Go to source

- You should use multiple types of evidence carefully when writing a persuasive essay. Logical appeals such as presenting data, facts, and other types of “hard” evidence are often very convincing to readers.

- Persuasive essays generally have very clear thesis statements that make your opinion or chosen “side” known upfront. This helps your reader know exactly what you are arguing. [14] X Research source

- Bad: The United States was not an educated nation, since education was considered the right of the wealthy, and so in the early 1800s Horace Mann decided to try and rectify the situation.

- For example, you could tell an anecdote about a family torn apart by the current situation in Syria to incorporate pathos, make use of logic to argue for allowing Syrian refugees as your logos, and then provide reputable sources to back up your quotes for ethos.

- Example: Time and time again, the statistics don't lie -- we need to open our doors to help refugees.

- Example: "Let us not forget the words etched on our grandest national monument, the Statue of Liberty, which asks that we "Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” There is no reason why Syrians are not included in this.

- Example: "Over 100 million refugees have been displaced. President Assad has not only stolen power, he's gassed and bombed his own citizens. He has defied the Geneva Conventions, long held as a standard of decency and basic human rights, and his people have no choice but to flee."

- Good: "Time and time again, science has shown that arctic drilling is dangerous. It is not worth the risks environmentally or economically."

- Good: "Without pushing ourselves to energy independence, in the arctic and elsewhere, we open ourselves up to the dangerous dependency that spiked gas prices in the 80's."

- Bad: "Arctic drilling may not be perfect, but it will probably help us stop using foreign oil at some point. This, I imagine, will be a good thing."

- Good: Does anyone think that ruining someone’s semester, or, at least, the chance to go abroad, should be the result of a victimless crime? Is it fair that we actively promote drinking as a legitimate alternative through Campus Socials and a lack of consequences? How long can we use the excuse that “just because it’s safer than alcohol doesn’t mean we should make it legal,” disregarding the fact that the worst effects of the drug are not physical or chemical, but institutional?

- Good: We all want less crime, stronger families, and fewer dangerous confrontations over drugs. We need to ask ourselves, however, if we're willing to challenge the status quo to get those results.

- Bad: This policy makes us look stupid. It is not based in fact, and the people that believe it are delusional at best, and villains at worst.

- Good: While people do have accidents with guns in their homes, it is not the government’s responsibility to police people from themselves. If they're going to hurt themselves, that is their right.

- Bad: The only obvious solution is to ban guns. There is no other argument that matters.

How to Polish Your Essay

- Does the essay state its position clearly?

- Is this position supported throughout with evidence and examples?

- Are paragraphs bogged down by extraneous information? Do paragraphs focus on one main idea?

- Are any counterarguments presented fairly, without misrepresentation? Are they convincingly dismissed?

- Are the paragraphs in an order that flows logically and builds an argument step-by-step?

- Does the conclusion convey the importance of the position and urge the reader to do/think something?

- You may find it helpful to ask a trusted friend or classmate to look at your essay. If s/he has trouble understanding your argument or finds things unclear, focus your revision on those spots.

- You may find it helpful to print out your draft and mark it up with a pen or pencil. When you write on the computer, your eyes may become so used to reading what you think you’ve written that they skip over errors. Working with a physical copy forces you to pay attention in a new way.

- Make sure to also format your essay correctly. For example, many instructors stipulate the margin width and font type you should use.

Expert Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://www.grammarly.com/blog/how-to-write-a-persuasive-essay/

- ↑ https://www.hamilton.edu/academics/centers/writing/writing-resources/persuasive-essays

- ↑ https://www.hamilton.edu/writing/writing-resources/persuasive-essays

- ↑ https://www.adelaide.edu.au/writingcentre/sites/default/files/docs/learningguide-mindmapping.pdf

- ↑ https://examples.yourdictionary.com/20-compelling-hook-examples-for-essays.html

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/transitions/

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/common_writing_assignments/argument_papers/rebuttal_sections.html

- ↑ http://www.readwritethink.org/files/resources/lesson_images/lesson56/strategy-definition.pdf

- ↑ https://stlcc.edu/student-support/academic-success-and-tutoring/writing-center/writing-resources/pathos-logos-and-ethos.aspx

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/editing-and-proofreading/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/revising-drafts/

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/the_writing_process/proofreading/proofreading_suggestions.html

About This Article

To write a persuasive essay, start with an attention-grabbing introduction that introduces your thesis statement or main argument. Then, break the body of your essay up into multiple paragraphs and focus on one main idea in each paragraph. Make sure you present evidence in each paragraph that supports the main idea so your essay is more persuasive. Finally, conclude your essay by restating the most compelling, important evidence so you can make your case one last time. To learn how to make your writing more persuasive, keep reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Joslyn Graham

Nov 4, 2017

Did this article help you?

Jul 28, 2017

Sep 18, 2017

Jefferson Kenely

Jan 22, 2018

Chloe Myers

Jun 3, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Level up your tech skills and stay ahead of the curve

Persuasive Essay: A Guide for Writing

Ever found yourself wrestling with the challenge of convincing others through your writing? Look no further – our guide is your go-to roadmap for mastering the art of persuasion. In a world where effective communication is key, this article unveils practical tips and techniques to help you produce compelling arguments that captivate your audience. Say goodbye to the struggles of conveying your message – let's learn how to make your persuasive essay informative and truly convincing.

What Is a Persuasive Essay

Persuasive essays are a form of writing that aims to sway the reader's viewpoint or prompt them to take a specific action. In this genre, the author employs logical reasoning and compelling arguments to convince the audience of a particular perspective or stance on a given topic. The persuasive essay typically presents a clear thesis statement, followed by well-structured paragraphs that provide evidence and examples supporting the author's position. The ultimate goal is to inform and influence the reader's beliefs or behavior by appealing to their emotions, logic, and sense of reason. If you need urgent help with this assignment, use our persuasive essay writing service without hesitation.

Which Three Strategies Are Elements of a Persuasive Essay

Working on a persuasive essay is like building a solid argument with three friends: ethos, pathos, and logos. Ethos is about trustworthiness, like when someone vouches for your credibility before making a point. Picture it as your introduction, earning trust from the get-go. Then comes pathos, your emotional storyteller. It's all about making your readers feel something, turning your essay into an experience rather than just a bunch of words. Lastly, logos is your logical thinker, using facts and solid reasoning to beef up your argument. These three work together to engage both the heart and mind of your audience. So, let's see how this trio can take your arguments from so-so to memorable.

In a persuasive essay, ethos functions much like introducing your friend as the go-to expert in their field before they share their insights with a new group. It's about showcasing the writer's credibility, expertise, and trustworthiness through a mix of personal experience, professional background, and perhaps even endorsements. Readers are more likely to buy into an argument when they believe the person presenting it knows their stuff and has a solid ethical standing, creating a foundation of trust. Does this information seem a bit confusing? Then simply type, ‘ write my paper ,’ and our writers will help you immediately.

Now, let's consider pathos – the emotional connection element. Imagine a movie that entertains and makes you laugh, cry, or feel a rush of excitement. Pathos in a persuasive essay aims to tap into your emotions to make you feel something. It's the storyteller in the essay weaving narratives that resonate personally. By sharing relatable anecdotes, vivid imagery, or emotionally charged language, writers can create a powerful connection with readers, turning a dry argument into a compelling human experience that leaves a lasting impression.

Lastly, logos is the cool-headed, logical friend who always has the facts straight. In a persuasive essay, logos presents a strong, well-reasoned argument supported by evidence, data, and solid reasoning. The backbone holds the essay together, appealing to the reader's sense of logic and reason. This might include citing research studies, providing statistical evidence, or employing deductive reasoning to build a solid case. So, think of ethos as your trustworthy friend, pathos as the emotional storyteller, and logos as the rational thinker – together, they create a persuasive essay that speaks to the heart and stands up to critical scrutiny. Choose the persuasive essay format accordingly, depending on how you’d like to approach your readers.

.webp)

Persuasive Essay Outline

Creating an outline for persuasive essay is like sketching a plan for your argument, which is the GPS to help your readers follow along smoothly. Start with an engaging intro that grabs attention and states your main point. Then, organize your body paragraphs, each focusing on one important aspect or evidence backing up your main idea. Mix in ethos (credibility), pathos (emotion), and logos (logic) throughout to make your argument strong. Don't forget to address opposing views and show why your stance is the way to go. Finally, wrap things up with a strong conclusion that reinforces your main points. Here’s a general outline for a persuasive essay:

How to start a persuasive essay? Introduction.

- Hook. Start with a captivating anecdote, surprising fact, or thought-provoking question to grab the reader's attention.

- Background. Provide context for the issue or topic you're addressing.

- Thesis Statement. Clearly state your main argument or position.

Body Paragraphs

Paragraph 1

- Topic Sentence. Introduce the first key point supporting your thesis.

- Supporting Evidence. Include facts, statistics, or examples that back up your point.

- Ethos, Pathos, Logos. Incorporate elements of persuasion to strengthen your argument.

Paragraph 2

- Topic Sentence. Introduce the second key point supporting your thesis.

- Supporting Evidence. Provide relevant information or examples to bolster your argument.

- Ethos, Pathos, Logos. Continue integrating persuasive elements for a well-rounded appeal.

Paragraph 3

- Topic Sentence. Introduce the third key point supporting your thesis.

- Supporting Evidence. Present compelling evidence or examples.

- Ethos, Pathos, Logos. Ensure a balanced use of persuasive strategies.

Counterargument

- Address opposing views. Acknowledge and counter opposing arguments.

- Refutation. Explain why the counterargument is invalid or less convincing.

- Summarize main points. Recap the key arguments from the body paragraphs.

- Call to Action. Encourage readers to take a specific stance, consider your perspective, or engage in further discussion.

Closing Statement

- Leave a lasting impression. End with a powerful statement that reinforces your thesis and strongly impacts the reader.

We recommend you study our guide on how to write an argumentative essay as well, as these two types of assignments are the most common in school and college.

.webp)

Take Your Persuasive Writing to the Next Level!

Give us your task to amaze your readers with our tried-and-true methods

How to WritHow to Write a Persuasive Essay

Writing a persuasive essay typically follows a structured format that begins with a compelling introduction, where the writer captures the reader's attention with a hook, provides background information on the topic, and presents a clear thesis statement outlining the main argument. The body paragraphs delve into supporting evidence and key points, each focusing on a specific aspect of the argument and incorporating persuasive elements such as ethos, pathos, and logos. Counterarguments are addressed and refuted to strengthen the overall stance. The conclusion briefly summarizes the main points, reiterates the thesis, and often includes a call to action or a thought-provoking statement to leave a lasting impression on the reader. Follow these tips if you want to learn how to write a good persuasive essay up to the mark:

Choose a Strong Topic

Selecting a compelling topic is crucial for a persuasive essay. Consider issues that matter to your audience and elicit strong emotions. A well-chosen topic captures your readers' interest and provides a solid foundation for building a persuasive argument. If you’re low on ideas, check out a collection of persuasive essay topics from our experts.

Research Thoroughly

Thorough research is the backbone of a persuasive essay. Dive into various sources, including academic journals, reputable websites, and books. Ensure that your information is current and reliable. Understanding the counterarguments will help you anticipate objections and strengthen your position.

Brainstorm a Solid Thesis Statement

Your thesis statement serves as the central point of your essay. It should be clear, concise, and specific, outlining your stance. Consider it a guideline for your readers, guiding them through your argument. A strong thesis statement sets the tone for the entire essay and helps maintain focus.

Organize Your Thoughts

A rigid persuasive essay structure is key to creating a desired effect on readers. Begin with an engaging introduction that introduces your topic, provides context, and ends with a clear thesis statement. The body paragraphs should each focus on a single point that supports your thesis, providing evidence and examples. Transition smoothly between paragraphs to ensure a cohesive flow. Conclude with a powerful summary that reinforces your main points and leaves a lasting impression.

Develop Compelling Arguments

Each body paragraph should present a persuasive argument supported by evidence. Clearly articulate your main points and use examples, statistics, or expert opinions to strengthen your claims. Make sure to address potential counterarguments and refute them, demonstrating the robustness of your position.

- Use Persuasive Language

Employ language that is strong, clear, and persuasive. Be mindful of your tone, avoiding overly aggressive or confrontational language. Appeal to your audience's emotions, logic, and credibility. Use rhetorical devices like anecdotes or powerful metaphors to make your writing more engaging and memorable.

Revise and Edit

The final step is revising and editing your essay. Take the time to review your work for clarity, coherence, and grammar. Ensure that your arguments flow logically and eliminate any unnecessary repetition. Consider seeking feedback from peers or mentors to gain valuable perspectives on the strength of your persuasive essay. You should also explore the guide on how to write a synthesis essay , as you’ll be dealing with it quite often as a student.

Tips for Writing a Persuasive Essay

The most important aspect of writing a persuasive essay is constructing a compelling and well-supported argument. A persuasive essay's strength hinges on the clarity and persuasiveness of the main argument, encapsulated in a robust thesis statement. This central claim should be clearly articulated and supported by compelling evidence, logical reasoning, and an understanding of the target audience. Here are more tips for you to consider:

- Write a Compelling Hook

Begin your essay with a captivating hook that grabs the reader's attention. This could be a surprising fact, a thought-provoking question, a relevant quote, or a compelling anecdote. A strong opening sets the tone for the rest of the essay.

- Establish Credibility

Build your credibility by demonstrating your expertise on the topic. Incorporate well-researched facts, statistics, or expert opinions that support your argument. Establishing credibility enhances the persuasiveness of your essay.

- Clearly Articulate Your Thesis

Craft a clear and concise thesis statement that outlines your main argument. This statement should convey your position on the issue and provide a path for the reader to follow throughout the essay. Note that if you use custom essay writing services , a thesis is automatically included in the assignment.

- Organize Your Arguments Effectively

Structure your essay with a logical flow. Each paragraph should focus on a single point that supports your thesis. Use transitional phrases to guide the reader smoothly from one idea to the next. This organizational clarity enhances the persuasive impact of your essay.

- Address Counterarguments

Anticipate and address potential counterarguments to strengthen your position. Acknowledge opposing viewpoints and provide compelling reasons why your stance is more valid. This demonstrates a thorough understanding of the topic and reinforces the credibility of your argument.

Choose words and phrases that evoke emotion and engage your reader. Employ rhetorical devices, such as metaphors, similes, or vivid language, to make your argument more compelling. Pay attention to tone, maintaining a respectful and persuasive demeanor.

- Appeal to Emotions and Logic

Strike a balance between emotional appeal and logical reasoning. Use real-life examples, personal stories, or emotional anecdotes to connect with your audience. Simultaneously, support your arguments with logical reasoning and evidence to build a robust case.

- Create a Strong Conclusion

Summarize your main points in the conclusion and restate the significance of your thesis. End with a powerful call to action or a thought-provoking statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader. A strong conclusion reinforces the persuasive impact of your essay.

Persuasive Essay Examples

Explore the persuasive essay examples provided below to gain a deeper comprehension of crafting this type of document.

Persuasive Essay Example: Are Women Weaker Than Men Today?

Students should explore persuasive essay examples as they provide valuable insights into effective argumentation, organizational structure, and the art of persuasion. Examining well-crafted samples allows students to grasp various writing techniques, understand how to present compelling evidence, and observe the nuanced ways in which authors address counterarguments. Additionally, exposure to diverse examples helps students refine their own writing style and encourages critical thinking by showcasing the diversity of perspectives and strategies. Here are two excellent persuasive essay examples pdf for your inspiration. If you enjoy the work of our writers, buy essay paper from them and receive an equally quality document prepared individually for you.

Example 1: “The Importance of Incorporating Financial Literacy Education in High School Curriculum”

This essay advocates for the imperative inclusion of financial literacy education in the high school curriculum. It emphasizes the critical role that early exposure to financial concepts plays in empowering students for lifelong success, preventing cycles of debt, fostering responsible citizenship, adapting to technological advancements, and building a more inclusive society. By arguing that financial literacy is a practical necessity and a crucial step towards developing informed and responsible citizens, the essay underscores the long-term societal benefits of equipping high school students with essential financial knowledge and skills.

Example 2: “Renewable Energy: A Call to Action for a Sustainable Future”

This persuasive essay argues for the urgent adoption of renewable energy sources as a moral imperative and a strategic move towards mitigating climate change, fostering economic growth, achieving energy independence, and driving technological innovation. The essay emphasizes the environmental, economic, and societal benefits of transitioning from conventional energy to renewable alternatives, asserting that such a shift is not just an environmentally conscious choice but a responsible investment in the sustainability and well-being of the planet for current and future generations.

Knowing how to write a persuasive essay is essential for several reasons. Firstly, it cultivates critical thinking and analytical skills, requiring students to evaluate and organize information effectively to support their arguments. This process enhances their ability to assess different perspectives and make informed decisions. The persuasive essay format also equips students with valuable communication skills, teaching them to articulate ideas clearly and convincingly. As effective communicators, students can advocate for their viewpoints, contributing to a more engaged and informed society. This proficiency extends beyond academic settings, proving crucial in various professional and personal scenarios. If you’d like to expedite the process, consider using our essay service , which saves time and brings positive grades.

Want to Easily Influence Your Readers?

Buy your persuasive essay right away to start using words to change the world!

What are the 7 Tips for Persuasive Essays?

How do i make a persuasive essay, related articles.

.webp)

Home / Guides / Writing Guides / Paper Types / How to Write a Persuasive Essay

How to Write a Persuasive Essay

The entire point of a persuasive essay is to persuade or convince the reader to agree with your perspective on the topic. In this type of essay, you’re not limited to facts. It’s completely acceptable to include your opinions and back them up with facts, where necessary.

Guide Overview

- Be assertive

- Use words that evoke emotion

- Make it personal

- Topic selection hints

Tricks for Writing a Persuasive Essay

In this type of writing, you’ll find it is particularly helpful to focus on the emotional side of things. Make your reader feel what you feel and bring them into your way of thinking. There are a few ways to do that.

Be Assertive

A persuasive essay doesn’t have to be gentle in how it presents your opinion. You really want people to agree with you, so focus on making that happen, even if it means pushing the envelope a little. You’ll tend to get higher grades for this, because the essay is more likely to convince the reader to agree. Consider using an Persuasive Essay Template to understand the key elements of the essay.

Use Words that Evoke Emotion

It’s easier to get people to see things your way when they feel an emotional connection. As you describe your topic, make sure to incorporate words that cause people to feel an emotion. For example, instead of saying, “children are taken from their parents” you might say, “children are torn from the loving arms of their parents, kicking and screaming.” Dramatic? Yes, but it gets the point across and helps your reader experience the

Make it Personal

By using first person, you make the reader feel like they know you. Talking about the reader in second person can help them feel included and begin to imagine themselves in your shoes. Telling someone “many people are affected by this” and telling them “you are affected by this every day” will have very different results.

While each of these tips can help improve your essay, there’s no rule that you have to actually persuade for your own point of view. If you feel the essay would be more interesting if you take the opposite stance, why not write it that way? This will require more research and thinking, but you could end up with a very unique essay that will catch the teacher’s eye.

Topic Selection Hints

A persuasive essay requires a topic that has multiple points of view. In most cases, topics like the moon being made of rock would be difficult to argue, since this is a solid fact. This means you’ll need to choose something that has more than one reasonable opinion related to it.

A good topic for a persuasive essay would be something that you could persuade for or against.

Some examples include:

- Should children be required to use booster seats until age 12?

- Should schools allow the sale of sugary desserts and candy?

- Should marijuana use be legal?

- Should high school students be confined to school grounds during school hours?

- Should GMO food be labeled by law?

- Should police be required to undergo sensitivity training?

- Should the United States withdraw troops from overseas?

Some topics are more controversial than others, but any of these could be argued from either point of view . . . some even allow for multiple points of view.

As you write your persuasive essay, remember that your goal is to get the reader to nod their head and agree with you. Each section of the essay should bring you closer to this goal. If you write the essay with this in mind, you’ll end up with a paper that will receive high grades.

Finally, if you’re ever facing writer’s block for your college paper, consider WriteWell’s template gallery to help you get started.

EasyBib Writing Resources

Writing a paper.

- Academic Essay

- Argumentative Essay

- College Admissions Essay

- Expository Essay

- Persuasive Essay

- Research Paper

- Thesis Statement

- Writing a Conclusion

- Writing an Introduction

- Writing an Outline

- Writing a Summary

EasyBib Plus Features

- Citation Generator

- Essay Checker

- Expert Check Proofreader

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tools

Plagiarism Checker

- Spell Checker

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Grammar and Plagiarism Checkers

Grammar Basics

Plagiarism Basics

Writing Basics

Upload a paper to check for plagiarism against billions of sources and get advanced writing suggestions for clarity and style.

Get Started

How to Write Perfect Persuasive Essays in 5 Simple Steps

WHAT IS A PERSUASIVE ESSAY?

A persuasive text presents a point of view around a topic or theme that is backed by evidence to support it.