Essay On Women Rights

500 words essay on women rights.

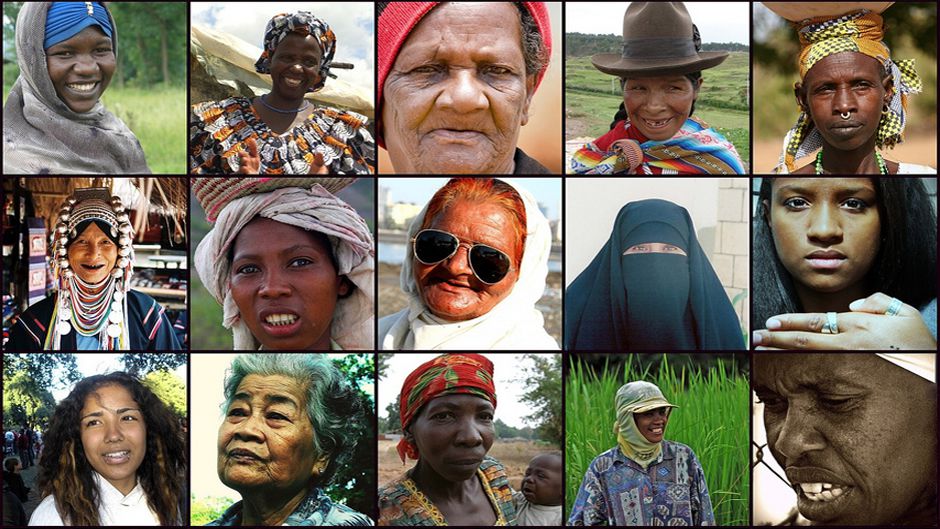

Women rights are basic human rights claimed for women and girls all over the world. It was enshrined by the United Nations around 70 years ago for every human on the earth. It includes many things which range from equal pay to the right to education. The essay on women rights will take us through this in detail for a better understanding.

Importance of Women Rights

Women rights are very important for everyone all over the world. It does not just benefit her but every member of society. When women get equal rights, the world can progress together with everyone playing an essential role.

If there weren’t any women rights, women wouldn’t have been allowed to do something as basic as a vote. Further, it is a game-changer for those women who suffer from gender discrimination .

Women rights are important as it gives women the opportunity to get an education and earn in life. It makes them independent which is essential for every woman on earth. Thus, we must all make sure women rights are implemented everywhere.

How to Fight for Women Rights

All of us can participate in the fight for women rights. Even though the world has evolved and women have more freedom than before, we still have a long way to go. In other words, the fight is far from over.

First of all, it is essential to raise our voices. We must make some noise about the issues that women face on a daily basis. Spark up conversations through your social media or make people aware if they are misinformed.

Don’t be a mute spectator to violence against women, take a stand. Further, a volunteer with women rights organisations to learn more about it. Moreover, it also allows you to contribute to change through it.

Similarly, indulge in research and event planning to make events a success. One can also start fundraisers to bring like-minded people together for a common cause. It is also important to attend marches and protests to show actual support.

History has been proof of the revolution which women’s marches have brought about. Thus, public demonstrations are essential for demanding action for change and impacting the world on a large level.

Further, if you can, make sure to donate to women’s movements and organisations. Many women of the world are deprived of basic funds, try donating to organizations that help in uplifting women and changing their future.

You can also shop smartly by making sure your money is going for a great cause. In other words, invest in companies which support women’s right or which give equal pay to them. It can make a big difference to women all over the world.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Conclusion of the Essay on Women Rights

To sum it up, only when women and girls get full access to their rights will they be able to enjoy a life of freedom . It includes everything from equal pay to land ownerships rights and more. Further, a country can only transform when its women get an equal say in everything and are treated equally.

FAQ of Essay on Women Rights

Question 1: Why are having equal rights important?

Answer 1: It is essential to have equal rights as it guarantees people the means necessary for satisfying their basic needs, such as food, housing, and education. This allows them to take full advantage of all opportunities. Lastly, when we guarantee life, liberty, equality, and security, it protects people against abuse by those who are more powerful.

Question 2: What is the purpose of women’s rights?

Answer 2: Women’s rights are the essential human rights that the United Nations enshrined for every human being on the earth nearly 70 years ago. These rights include a lot of rights including the rights to live free from violence, slavery, and discrimination. In addition to the right to education, own property; vote and to earn a fair and equal wage.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

A demonstrator raises a sign that says, "Human rights are women's rights" at the Women's March in Los Angeles in 2018. Though the concept had long been controversial, the United Nations declared that women's rights are human rights in 1995 at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing.

- HISTORY & CULTURE

'Women's Rights are Human Rights,' 25 years on

Hillary Rodham Clinton’s speech at a UN conference propelled this idea into the mainstream after centuries of society sidelining gender equality as “women’s issues.”

When Hillary Rodham Clinton approached the podium at a United Nations conference on women in September 1995 in Beijing, she faced an uncertain audience. Only a few people had read the speech, which was a well-guarded secret even to high-ranking members of the president’s cabinet. “Nobody knew what to expect,” recalls Melanne Verveer , the then first lady’s chief of staff, who later served as the first U.S. Ambassador for Global Women’s Issues when Clinton became secretary of state.

Twenty-five years later, a single phrase from Clinton’s speech has entered mainstream parlance: “Women’s rights are human rights.” The concept wasn’t new. But the excitement and energy that Clinton’s speech generated at the Fourth World Conference on Women helped elevate the idea to one that fuels modern feminism and international efforts to achieve gender parity.

Women’s rights advocates have long argued that gender equality should be a human right—but were thwarted for years by those who claimed their rights were subordinate to those of men. During the infancy of the American feminist movement of the 1830s, abolitionists and women’s rights advocates tussled over whether it was more important to seek freedom for enslaved people or equality for women. As women pushed for their rights to vote, access educational opportunities, and own property, male abolitionists like Theodore Weld urged them to wait, arguing that they should first fight for the abolition of slavery as a matter of human rights.

Some women, such as educator Catharine Beecher , argued that women deserved rights because of their morality—as they were uniquely positioned to edify and enlighten men—not their humanity. She cautioned that their roles in public life should not extend into equality in the home. In response, abolitionist and women’s rights advocate Angelina Grimké wrote , “I recognize no rights but human rights,” noting that a society that didn’t give women power or a political voice violated their innate human rights. She was just one of a group of women who invoked the idea throughout the 19 th century. (Grimké later went on to marry Weld, who was her mentor.)

In the 1970s, the idea resurfaced as so-called second-wave feminists, who believed women should have access to full societal and legal rights, attempted to put women’s rights on the international agenda. In many countries, there was no consensus that women had a right to equal partnership in marriage, power over their finances, an equal education, or a life free of sexual assault or harassment. Between 1975 and 1995, the United Nations convened four landmark Conferences on Women that made gender parity a global priority. ( Here are the best and worst countries to be a woman. )

The first conference, held in Mexico City in 1975, recognized women’s equality. Eighty-nine of the 133 nations that participated adopted a framework to help women gain equal access to all facets of society; several western nations abstained , and the United States opposed the framework. In 1980, a follow-up conference in Copenhagen called for stronger protections for women, with an emphasis on property ownership, child custody, and a restructuring of inheritance laws. A third in Nairobi in 1985 called attention to violence against women. But though these conferences brought women’s issues to the international stage, each one fell short because of a lack of consensus and failure to implement the adopted platforms. By 1995, global women’s leaders had agreed it was time to create an action plan to guarantee equality for women.

Slated for Beijing in September 1995, the Fourth World Conference on Women took place in an atmosphere of intense international condemnation of the host nation’s treatment of its own citizens. Human rights groups and governments criticized China’s history of political imprisonment, torture, detention, and denial of religious freedom. The nation’s one-child policy , which put family planning decisions under state control, came under particular fire.

Women watch Hillary Rodham Clinton speak to the abuse against women at the 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. Her call for women's rights to be considered human rights has since become mainstream.

News that Clinton would attend and speak at the meeting prompted an American outcry. “There were serious efforts not to make [the speech] happen,” Verveer recalls. “You had a cacophony of voices that were trying to keep this from being meaningful or successful.” The first lady faced outrage from human rights advocates who objected to the China visit on principle, conservative politicians who disapproved of her outspoken feminism, and people who worried the speech could threaten the bilateral relationship between the U.S. and China.

FREE BONUS ISSUE

You may also like.

Meet the 5 iconic women being honored on new quarters in 2024

Women won the vote with the 19th Amendment, but hurdles remain

Title IX at 50: How the U.S. law transformed education for women

“I wanted to push the envelope as far as I could for girls and women,” Clinton said in a virtual public event hosted on September 10 by the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security , of which Verveer is the executive director. ( A century after women’s suffrage in the U.S., the fight for equality isn’t over. )

On September 5, 1995, the second day of the conference, Clinton took the podium in front of representatives from all over the world. As Clinton spoke, Verveer watched the delegates’ faces closely. The speech cited a “litany of violations against women,” including rape, female genital mutilation, dowry burnings, and domestic violence—which Clinton labeled as human rights violations. She excoriated those who forcibly sterilized women and condemned those who restricted civil liberties, a jab at China, which restricted news coverage of the event.

The room was “filled with women who were in the trenches of those issues,” says Verveer. “The audience was completely pulled into their struggle.” The mostly female delegation applauded and cheered during the 20-minute speech, sometimes even pounding their fists on the tables to underscore their approval.

“The reaction was extraordinary,” Verveer says. On September 15, the phrase “women’s rights are human rights” was unanimously adopted as part of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action , which defined 12 areas—including education, health, economic participation, and the environment—in need of urgent international action. The document still governs the global agenda for women’s issues and is credited with helping narrow the education gap, improve maternal health, and reduce violence against women. ( Around the world, women are taking charge of their futures. )

Fourth World Conference on Women participants (from left) Benedita Da Silva of Brazil, Vuyiswa Bongile Keyi of Canada, and Silvia Salley of the United States cheer at the conclusion of the "Women of Color" press briefing where they stated that racism was not adequately addressed in the declaration.

Today, the idea that human rights and women’s rights are synonymous is considered mainstream. “I have rarely seen a single message carry such [an] important meaning and have such a durable life,” former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright said at the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security event commemorating the anniversary.

But the work of gender equality is not yet done—and 25 years after Beijing, women still face systemic inequities and gaps in terms of safety, economic and political mobility, and more. “Girls need to know that they stand on the shoulders of other people who struggled to gain the rights they enjoy today,” says Verveer. “They need to play a role in ensuring the work goes on. There has been progress, but there is a long journey ahead.”

Related Topics

- CIVIL RIGHTS

A century after women’s suffrage, the fight for equality isn’t over

MLK and Malcolm X only met once. Here’s the story behind an iconic image.

These Black transgender activists are fighting to ‘simply be’

Harriet Tubman, the spy: uncovering her secret Civil War missions

Scientists are finally studying women’s bodies. This is what we’re learning.

- History & Culture

- Photography

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Are Women’s Rights Human Rights?

Are Women’s Rights Human Rights? Critically Evaluate the Tensions Between Feminist and Non-Feminist Approaches to Contemporary Human Rights Issues and Debates.

Introduction

For many feminist scholars, in spite of a concerted effort by the international community towards international legislation on women’s rights as human rights, including the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women of 1979 (Women’s Convention), the only matter for contention surrounding human rights is not whether they are gender equal, but rather, whether the entire concept of human rights is “gender-biased and/or gender-blind” (Guerrina & Zalewski, 2007: 9). Drawing on the work of feminist lawyers and analysts, as well as human rights groups, this essay will argue that a non-feminist approach to women’s human rights all too often sees them as separate or in some way secondary to other human rights concerns, does not take women’s lives and daily experiences into account, and sees women’s human rights as conflicting with other rights such as religious practices, the rights of men or the (perceived) rights of the unborn child from the moment of conception. While there are overwhelming numbers of examples of violations of all aspects of women’s human rights – including their political, social and economic rights – this essay will focus on women’s reproductive rights as a prime example of how the law’s male-centeredness, lack of consideration for women’s experiences and woolly language, jeopardises women’s most fundamental right: their right to life. By examining the concept of and legal backing for women’s reproductive rights, then considering the cases of three countries that have signed and ratified the Women’s Convention, this essay will show that a lack of clarity, resources and power of enforcement mean that human rights law actually undermines the feminist approach to women’s human rights by giving legitimacy to states who have no intention of removing discriminatory and life-threatening practices and legislation against women.

Human Rights or the Rights of Man?

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 states that “Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as […] sex” (United Nations, date unknown(a)). However, feminist lawyers and scholars have convincingly shown that this is not the case and the very treaties and principles upon which the human rights framework was created defend the rights of man and, in particular, male household heads (Moller Okin, 1998: 18). Not only does the declaration refer repeatedly to “man” and “his” rights, but it also deals only with the public realm, protecting the rights of the family from outside intrusion. In particular, Article 12 declares: “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour or reputation” (United Nations, date unknown(a), emphasis added). For feminists, this is the ultimate example of the public/private dichotomy in which domestic matters, and those which most often concern the lives of women, are seen as private and of no concern to the state. Human rights law has evolved since 1948 and there have been three so-called “generations” of human rights treaties (civil and political rights; social and cultural rights; the rights of groups or peoples), yet for Hilary Charlesworth they all share the same flaw: “they are built on typically male life experiences and in their current form do not respond to the most pressing risks women face” (1994: 58 – 59). For the many women around the world whose greatest risk is the one they face at home, a list of political, economic and above all public rights will mean very little. Whereas, the very real dangers faced by women inside or outside of the home are often seen as “too specific to women to be seen as human or too generic to human beings to be seen as specific to women” (MacKinnon, 1994: 10): in other words, the law shows gender-bias or gender-blindness. Women have distinctive rights, which are also human rights, and which require seeing the human as not only male (Maya, 2007: 97).

An effort has been made more recently to redress these imbalances and inequalities and to assert the human rights of women, most noticeably through the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and its Optional Protocol, and through international conferences such as the Beijing Platform for Action. These were no doubt born out of feminist activism; however their feminism has been tempered by non-feminist and oppressive states refusing to subscribe to principles that could greatly limit them (MacKinnon, 1994: 6), and their activism has been restricted by the enduring patriarchy of the United Nations. The resulting Women’s Convention is largely one that protects women’s rights to the same rights stated for men in existing treaties, in other words an “approach of adding women and stirring them into existing first generation human rights categories” (Bunch, 1990: 494), rather than acknowledging women’s specific experiences and rights. States were also allowed to sign and ratify the Women’s Convention whilst stating reservations, many of which are completely contrary to the aim of non-discrimination. For example, in response to Article 16 on equal marriage rights, Algeria entered a reservation that these should not contradict the Algerian Family Code. Several European countries exercised their right under article 29(1) to dispute this reservation, however Algeria had already entered a reservation declaring that it did not consider itself to be bound by article 29(1) and so little could be done (Neuwirth, 2005: 28). As Jessica Neuwirth points out, “[i]n effect, Algeria stated its willingness to implement CEDAW so long as nothing needed to be done to implement CEDAW” (ibid: 29).

Feminist lawyers working in this field have been quick to point out the multiple other ways in which CEDAW and the process of incorporating a gender perspective in human rights processes have not been given the same priority or resources as other human rights treaties. These include, but are not limited to: the fact that the Commission on the Status of Women has fewer staff, less budget and less effective mechanisms for implementation than the Human Rights Commission (Bunch, 1990: 492); while women make up 74% of membership of the committees on CEDAW and the Rights of the Child, they are just 15% of the members of the other human rights committees (Charlesworth, 2005: 7); the Human Rights Committee is able to reject reservations to treaties if they are deemed to be against the entire purpose of the law, yet the CEDAW Committee cannot do the same (Neuwirth, 2005: 26); states only report to the Committee every four years on their implementation of the Convention, and there is no mechanism to hold them accountable at any other time (Charlesworth & Chinkin, 2000: 220); and during the 1993 World Conference on Human Rights, governments called for measures to assist the Committee on the Rights of the Child in its mandate, yet no such request was made for CEDAW (Sullivan, 1994: 160). While there is clearly still an overwhelming gender-bias and/or gender-blindness in the field of human rights, the very existence of CEDAW and the policy of gender mainstreaming at the UN have been used to justify reducing the resources available to initiatives for women within UN agencies. As Hilary Charlesworth puts it, “[g]ender has been defanged” (2005: 16).

Where are Women’s Reproductive Rights?

Perhaps one of the best examples of the lack of acknowledgement of women’s lives and experiences in international human rights law can be seen in the scant provision for women’s reproductive rights. The Convention makes no reference at all to women’s sexual rights, such as freedom to choose whether or not to have sex, freedom to have consensual sex and sex not linked to reproduction (Amnesty International, 2010: 14), there is some limited mention of women’s reproductive rights. They are entitled to access to information, advice and services for family planning, as well as the information, education and means to decide on the number and spacing of their children (United Nations, date unknown(b)). This seems woefully inadequate when “[m]aternity is ranked as the primary health problem in young women (ages 15 – 44) in developing countries, accounting for 18 per cent of the total disease burden” (Cook, Dickens & Fathalla, 2003: 9-10), and “pregnancy related deaths are the leading cause of mortality for 15 to 19-year-old girls worldwide” (Amnesty International, 2009: 10). The language of the Convention is too weak, the terms used too vague, and once again the greatest threats to women worldwide escape the boundaries of international law.

For the most part, those wishing to make a human rights claim on a violation of their reproductive rights, must use the terminology of other, “mainstream” rights to do so. This in itself may be a very difficult thing for a woman to do; as Sally Engle Merry argues, “[h]uman rights are difficult for individuals to adopt as a self-definition in the absence of institutions that will take these rights seriously” (2003: 281). Some lawyers have learned to interpret the law in favour of women, “[looking] at women’s lives first and [holding] human rights law accountable to what we need” (MacKinnon, 1994: 6), and Amnesty International has created a table of women’s sexual and reproductive rights based on the assertion that these require respect for rights such as the rights to life, freedom from torture and to physical and mental integrity (2010: 14).

However, just as the inexplicit language of the law can be interpreted in a feminist way, so too can it be interpreted by states in a non-feminist way, and the content of treaties can send out mixed messages. Looking at a table of conventions and declarations related to reproductive rights (see Cook, Bernard & Fathalla, 2008: 438 – 443), the most startling observation is that the Women’s Convention does not mention the right to life. This right is protected for all human beings, with no distinction according to sex, in the Declaration of Human Rights, however the international community still felt the need to reiterate it in the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and not CEDAW. During the drafting on the CRC, there was considerable disagreement among states on the stage at which a child has rights, with some states arguing for the rights of the unborn child from the moment of conception. This was rejected, however no lower age limit was set, leaving the interpretation of the world “child” to individual states. Eventually, to avoid a recurrence of the same debate, it was suggested by Italy and accepted by states that the “right to survival” should be augmented and linked to the “right to life” (Alston, 1990: 164). And so, the right to life was included in the Convention on the Rights of the Child while it is absent from CEDAW, and was left sufficiently vague in terms of starting point, so that it could be interpreted by states to protect the right to life or the right to be born of an unborn child, even when to do so would endanger the right to life of an adult woman.

Much has been made of the tensions between feminists and non-feminists, and even within feminisms, in terms of advocacy, women’s rights and cultural relativity. While cultural relativity is often cited as a reservation in human rights law and debates, this is done most of all when it comes to issues concerning women’s rights, sexuality and reproduction, even in contexts where the traditions or practices raised as objections are ignored in other aspects of society (Charlesworth & Chinkin, 2000: 222; Moller Okin, 1998: 36). While not all claims to humanity are universal and no one context, culture or continent can truly represent all peoples, the following three examples from very different contexts, cultures and continents show that some violations of women’s human rights are universal. In particular, it is still the case the world over that a woman’s reproductive rights, which impact on her right to life, are still seen as secondary or conflicting with men’s rights, religious freedoms, the rights of the unborn child, or even financial concerns and budgeting.

Marital Status Discrimination in Indonesia

Indonesia ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women on 9July 1993. The only reservation it entered was to say that it does not consider itself bound by the provisions of article 29, paragraph 1: the dispute process by which another state may bring the application, or lack thereof, of the Convention of a state to the attention of the International Court of Justice (United Nations, date unknown(c)). In other words, with this reservation the government of Indonesia has ensured that it does not need to apply the Convention in any future legislation nor indeed address the existing discriminatory legislation in Indonesia that defines a wife’s responsibility as “taking care of the household to the best of her ability” and has yet to criminalise marital rape (Amnesty International, 2010: 16 & 19).

In terms of reproductive rights, the government in Indonesia has shown a total disregard for what limited provisions are stated within the Convention to which it is party. For example, while the Convention clearly states that women have a right to information, education and means to control the number of children they conceive, the Indonesian Criminal Code states that it is a criminal offence to provide information to anyone on means of preventing or interrupting pregnancy (ibid: 30). While CEDAW states that women have a right to access this information, the Political Covenant does contain exceptions under which states may restrict people’s right to impart information. Contained within Article 19(3)(b), one such exception is “for the protection of national security or of public order, or of public health or morals” (Cook, Dickens & Fathalla, 2003: 209-210). Until human rights law explicitly states which rights take priority, and what constitutes or does not constitute public morals, states will be able to interpret the rules in a way that is fitting to their pre-existing legislation and Conventions like CEDAW become almost meaningless to the women of Indonesia.

In spite of Article 1 of the Convention, which states that women must enjoy these rights “irrespective of their marital status” (United Nations, date unknown(b)), the Population and Family Development Law and the Health Law in Indonesia state that only married couples have a right to access sexual health and reproductive health services (Amnesty International 2010: 23). Furthermore, some contraceptives require that a woman obtains permission from her husband to be able to access them (ibid: 27). This explicitly denies the rights of all women, irrespective of their marital status, to decide the number and spacing of their children. Within a marriage, it also completely denies bodily autonomy by giving priority to a husband’s right to decide whether to have children over a wife’s.

Finally, and perhaps most worryingly of all, is the fact that abortion is completely illegal unless in cases of rape or complications in the pregnancy that are particularly life-threatening to the woman. In these cases, there are still strict criteria to apply that leave women’s fates very much in the hands of medical professionals, and in the case of life-threatening complications a woman still requires her husband’s consent to go ahead with an abortion (ibid: 33-34). Not only does this mean that an unmarried woman or girl with life-threatening complications has no choice but to continue with a pregnancy, but it also means that a married woman’s health is entirely determined by whether her husband thinks it is worth risking. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, the maternal mortality rate in Indonesia is 470 per 100,000 live births – 47 times that of the United Kingdom (Cook, Dickens & Fathalla, 2003: 406-417) – and 11 per cent of those deaths are attributed to unsafe abortions (Amnesty International, 2010: 24). In the case of countries like Indonesia, CEDAW clearly serves only to make them appear more legitimate to other states in the international arena. There is little or no evidence to show that they subscribe to the principles of the Convention, or have any intention of implementing them in law or practice.

One in Eight: Maternal Mortality in Sierra Leone

In Sierra Leone, a woman has a one in eight chance of dying as a result of pregnancy or childbirth in her lifetime (Amnesty International, 2009: 1), with one in 50 births resulting in death and an average of 6.5 births per woman (Cook, Dickens & Fathalla, 2003: 414). There are currently no emergency obstetric facilities able to provide life-saving caesarean sections and blood transfusions in six of the country’s 13 districts, and while the World Health Organisation estimates that between five and 15 per cent of deliveries will need caesarean sections, they make up just one percent of births in Sierra Leone (Amnesty International, 2009: 2 & 20).

The civil war that devastated the country and the severe levels of poverty and deprivation are significant factors in a country where at the onset of war the government employed 300 doctors, and by mid-2009 this number had dropped to 78 (ibid: 8). However, to attribute high levels of maternal mortality entirely to financial factors is to ignore the gender-bias and/or gender-blindness of the Sierra Leonean government, and its complicity in a situation in which maternal mortality is so frequent that it is perceived to be “‘normal’, or inevitable, rather than preventable” (ibid: 12).

An Amnesty International report in 2009 found that less than half of the money the government allocates to health services reaches its intended destination each year (ibid: 4). One of the many results of this is that government health officers are not being paid and so decide to charge for the services and drugs they offer, many of which should be provided free to pregnant women by law (ibid: 18). In a culture in which men are permitted to take as many wives as they feel they can afford to keep, and in which men control a household’s money, some 68 per cent of the mothers Amnesty interviewed stated that it was their husband’s decision where they gave birth and whether they had enough money to pay for emergency obstetric care (ibid: 11).

For Cook, Dickens and Fathalla, there is no financial justification for such appalling levels of maternal mortality: “[t]here is no country that is so poor that it cannot do something to improve the reproductive health of its people” (2003: 55), and in fact services such as family planning and maternal health are “the most cost-effective health interventions” in terms of long-term benefits to communities (ibid: 191). Education is perhaps one of the most cheap and effective ways to address the fact that 94 per cent of women in Sierra Leone undergo female genital mutilation practices that could increase the risks to them in childbirth (ibid: 10), or to address the commonly held belief that women have an obstructed labour because they have been unfaithful to their husband and must confess before they can be given emergency health care (ibid: 12).

The fact that a baby girl in Sierra Leone faces a one in eight chance of dying during her lifetime because of pregnancy or childbirth is not an inevitable consequence of severe economic deprivation: it is a violation of women’s reproductive rights and hence their right to life. Until the government in Sierra Leone and the international community begin to see it as such however, it is difficult to see how the situation can improve.

“She Had a Heartbeat Too”: The Death of Savita Halappanavar

The Republic of Ireland ratified CEDAW on 23 December 1985 with no reservations, and it even disputed the reservations of Saudi Arabia, Oman, Brunei and Qatar to certain articles of the Convention on the grounds that references to religious laws “may cast doubts on the commitment of the reserving State to fulfil its obligations under the Convention” (United Nations, date unknown(c)). Nonetheless, due to the enduring influence of the Catholic Church in Ireland, the state has continually failed to clarify its position on abortion in cases where a mother’s life is in danger. Tragically, in October 2012, this lack of clarity led to the death of Savita Halappanavar when she was refused an abortion by medical staff in a hospital. Her husband claims that they were told that they would definitely lose the foetus, yet were repeatedly refused the abortion because doctors could still detect a foetal heartbeat and “this is a Catholic country” (McDonald, 2012b).

Article 40(3)(3) of the Irish Constitution protects the “right to life of the unborn”, although it does also recognise the “equal right to life of the mother” (Mullaly, 2005: 89-90). The CEDAW Committee has in the past expressed concern over women’s reproductive rights in Ireland and the influence that the Catholic Church has over these (ibid: 79), the European Court of Human Rights ruled two years ago that Ireland was failing mothers whose lives were at risk during pregnancy by not providing abortion (Houstan, 2012), and in 1992 the Irish population voted in favour of legalising abortion in life-threatening cases in a referendum (Mullaly, 2005: 95). In spite of all of this, no clarification has yet been given on the meaning of Article 40(3)(3), and the resulting uncertainty led the doctors in the case of Savita Halappanavar to refuse a medical procedure that would have saved her life, in favour of not ending the life of a foetus that they already knew she would lose. As Cook, Bernard and Fathalla state,

“[l]aws that prohibit medical procedures but that do not have clearly stated or indeed any exceptions where women’s lives […] are at risk can be shown to violate human rights requirements” (2003: 51).

Savita’s mother’s reaction to her death sums up the way in which the Irish state views women: “In an attempt to save a 4-month-old foetus they killed my […] daughter. How is that fair you tell me?” (McDonald, 2012a). Similarly, one protestor in a vigil held after Savita’s death, held a picture of Savita with a caption reading “she had a heartbeat too” (McDonald, 2012b). While the media coverage of the event refers regularly to women’s rights and human rights, there is no mention of Ireland’s commitments as a state party to CEDAW or other human rights instruments. The government has now promised to bring in legislation in 2013 to legalise abortion in life-threatening cases (BBC, 2013), however only time will tell whether it succeeds in clarifying the issue. Given its track record, it would seem that this limited and glacial progress is linked more to public protests and pressure than any sense of being bound by its commitment to CEDAW. Whatever happens in the future, it is certain that the state’s inaction on an issue that has been brought to its attention over decades, violated Savita Halappanavar’s right to life.

Conclusions

Why is it so important that women’s reproductive rights be recognised and fully acknowledged as human rights, not because they touch on other aspects of human rights, but in their own right? To do so would empower women around the world to challenge their own states’ oppressive and discriminatory laws, and would open up their rights to claim asylum in other countries, which in turn would be a considerable incentive for other states to take an interest in the treatment of women within the ‘privacy’ of their own states (Moller Okin, 1998: 39). The non-feminist hijacking of CEDAW has resulted in a convention that does not reflect the lives of women and still seems to see some issues as too personal to be political, and some dangers as inevitable and inherent to the condition of being female. Feminists must continue fighting to rescue women’s human rights and to gain international recognition for the fact that when a woman dies from a preventable situation, her government is complicit in that violation of her most basic right, the right to life.

References

Alston, Philip (1990), “The Unborn Child and Abortion under the Draft Convention on the Rights of the Child”, Human Rights Quarterly , 12(1), pp. 156-178

Amnesty International (2009), Out of Reach: The Cost of Maternal Health in Sierra Leone , available at http://www.amnesty.org.uk/uploads/documents/doc_19708.pdf [accessed on 31st December 2012]

Amnesty International (2010), Left Without a Choice: Barriers to Reproductive Health in Indonesia , available at: http://www.amnesty.org.uk/uploads/documents/doc_21542.pdf [accessed on 31st December 2012]

BBC News (2013), “Irish government hears abortion submissions”, available at http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-20937342 [accessed on 8th January 2013]

Bunch, Charlotte (1990), “Women’s Rights as Human Rights: Toward a Re-Vision of Human Rights”, Human Rights Quarterly , 12 (4), pp. 486-498

Charlesworth, Hilary (1994), “What are ‘Women’s International Human Rights?’”, in Cook, Rebecca J. (ed.), Human Rights of Women: National and International Perspectives , University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, pp. 58-84

Charlesworth, Hilary and Chinkin, Christine (2000), The boundaries of international law: A feminist analysis , Manchester University Press: Manchester

Charlesworth, Hilary (2005), “Not Waving but Drowning: Gender Mainstreaming and Human Rights in the United Nations”, Harvard Human Rights Journal , 18, pp. 1-18

Cook, Rebecca J., Dickens, Bernard M., and Fathalla, Mahmoud F. (2003), Reproductive Health and Human Rights: Integrating Medicine, Ethics, and Law , Oxford University Press: Oxford

Engle Merry, Sally (2003), “Rights Talk and the Experience of Law: Implementing Women’s Human Rights to Protection from Violence”, Human Rights Quarterly , 25(2), pp. 343-381

Guerrina, Roberta and Zalewksi, Marysia (2007), “Negotiating differences/negotiating rights: the challenges and opportunities of women’s human rights”, Review of International Studies , 33(1), pp. 5-10

Houstan, Muiris (2012), “Investigations begin into death of woman who was refused an abortion”, British Medical Journal , 345(e8161), available at http://211.144.68.84:9998/91keshi/Public/File/38/345-7884/pdf/bmj.e7824.full.pdf [accessed on 7th January 2013]

Lloyd, Maya (2007), “(Women’s) human rights: paradoxes and possibilities”, Review of International Studies , 33(1), pp. 91-103

MacKinnon, Catharine A. (1994), “Rape, Genocide, and Women’s Human Rights”, Harvard Women’s Law Journal , 17, pp. 5-16

McDonald, Henry (2012a), “Irish abortion laws to blame for woman’s death, say parents”, The Guardian , available at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/nov/15/irish-abortion-law-blame-death [accessed on 8th January]

McDonald, Henry (2012b), “Ireland to legalise abortions where woman’s life is at risk”, The Guardian , available at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/dec/18/ireland-legalise-abortion-life-risk [accessed on 8th January 2013]

Moller Okin, Susan (1998), “Feminism, Women’s Human Rights and Cultural Differences”, Hypatia , 13(2), pp. 32-52

Mullaly, Siobhán (2005), “Debating Reproductive Rights in Ireland”, Human Rights Quarterly, 27(1), pp. 78-104

Neuwirth, Jessica (2005), “Inequality Before the Law: Holding States Accountable for Sex Discriminatory Laws Under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women and Through the Beijing Platform for Action”, Harvard Human Rights Journal , 18, pp. 19-54

Sullivan, Donna J. (1994), “Women’s Human Rights and the 1993 World Conference on Human Rights”, American Journal of International Law , 8(1), pp. 152-167

United Nations (date unknown(a)), “The Universal Declaration of Human Rights”, available at: http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/index.shtml [accessed on 8th January 2013]

United Nations (date unknown(b)), “Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women”, available at: http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/cedaw.htm [accessed on 8th January 2013]

United Nations (date unknown(c)), “Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women: Status of ratification, reservations and declarations”, available at: http://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IV-8&chapter=4&lang=en#EndDec [accessed on 8 th January 2013].

Written by: Rosie Walters Written at: University of Bristol Written for: Jutta Weldes Date written: January 2013

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- State Feminism and the Islamist-Secularist Binary: Women’s Rights in Tunisia

- Women’s Rights in North Korea: Reputational Defense or Labor Mobilization?

- The Resonance of Name-Shaming in Global Politics: The Case of Human Rights Watch

- Human Rights and Security in Public Emergencies

- Cultural Relativism in R.J. Vincent’s “Human Rights and International Relations”

- Navigating the Complexities of Business and Human Rights

Please Consider Donating

Before you download your free e-book, please consider donating to support open access publishing.

E-IR is an independent non-profit publisher run by an all volunteer team. Your donations allow us to invest in new open access titles and pay our bandwidth bills to ensure we keep our existing titles free to view. Any amount, in any currency, is appreciated. Many thanks!

Donations are voluntary and not required to download the e-book - your link to download is below.

WOMEN’S RIGHTS

Women’s rights are human rights.

We are all entitled to human rights. These include the right to live free from violence and discrimination; to enjoy the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health; to be educated; to own property; to vote; and to earn an equal wage.

But across the globe many women and girls still face discrimination on the basis of sex and gender. Gender inequality underpins many problems which disproportionately affect women and girls, such as domestic and sexual violence, lower pay, lack of access to education, and inadequate healthcare.

For many years women’s rights movements have fought hard to address this inequality, campaigning to change laws or taking to the streets to demand their rights are respected. And new movements have flourished in the digital age, such as the #MeToo campaign which highlights the prevalence of gender-based violence and sexual harassment.

Through research, advocacy and campaigning, Amnesty International pressures the people in power to respect women’s rights.

On this page we look at the history of women’s rights, what women’s rights actually are, and what Amnesty is doing.

WHAT ARE WE FIGHTING FOR?

What do we mean when we talk about women’s rights? What are we fighting for? Here are just some examples of the rights which activists throughout the centuries and today have been fighting for:

Women’s Suffrage

During the 19th and early 20 th centuries people began to agitate for the right of women to vote . In 1893 New Zealand became the first country to give women the right to vote on a national level. This movement grew to spread all around the world, and thanks to the efforts of everyone involved in this struggle, today women’s suffrage is a right under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (1979).

However, despite these developments there are still many places around the world where it is very difficult for women to exercise this right. Take Syria for example, where women have been effectively cut off from political engagement, including the ongoing peace process.

In Pakistan, although voting is a constitutional right, in some areas women have been effectively prohibited from voting due to powerful figures in their communities using patriarchal local customs to bar them from going to the polls.

And in Afghanistan, authorities recently decided to introduce mandatory photo screening at polling stations, making voting problematic for women in conservative areas, where most women cover their faces in public.

Amnesty International campaigns for all women to be able to effectively participate in the political process.

Sexual and Reproductive Rights

Everyone should be able to make decisions about their own body.

Every woman and girl has sexual and reproductive rights . This means they are entitled to equal access to health services like contraception and safe abortions, to choose if, when, and who they marry, and to decide if they want to have children and if so how many, when and with who.

Women should be able to live without fear of gender-based violence, including rape and other sexual violence, female genital mutilation (FGM), forced marriage, forced pregnancy, forced abortion, or forced sterilization.

But there’s a long way to go until all women can enjoy these rights.

For example, many women and girls around the world are still unable to access safe and legal abortions. In several countries, people who want or need to end pregnancies are often forced to make an impossible choice: put their lives at risk or go to jail.

In Argentina , Amnesty International has campaigned alongside grassroots human rights defenders to change the country’s strict abortion laws. There have been some major steps forward, but women and girls are still being harmed by laws which mean they cannot make choices about their own bodies.

We have also campaigned successfully in Ireland and Northern Ireland , where abortion was recently decriminalized after many decades of lobbying by Amnesty and other rights groups.

In Poland along with more than 200 human and women’s rights organisations from across the globe, Amnesty has co-signed a joint statement protesting the ‘Stop Abortion’ bill.

South Korea has recently seen major advances in sexual and reproductive rights after many years of campaigning by Amnesty and other groups, culminating in a ruling by South Korea’s Constitutional Court that orders the government to decriminalize abortion in the country and reform the country’s highly restrictive abortion laws by the end of 2020.

In Burkina Faso, Amnesty International has supported women and girls in their fight against forced marriage , which affects a huge number of girls especially in rural areas.

And in Sierra Leone, Amnesty International has been working with local communities as part of our Human Rights Education Programme, which focuses on a number of human rights issues, including female genital mutilation .

In Zimbabwe, we found that women and girls were left vulnerable to unwanted pregnancies and a higher risk of HIV infection because of widespread confusion around sexual consent and access to sexual health services. This meant that girls would face discrimination, the risk of child marriage, economic hardship and barriers to education.

In Jordan Amnesty International has urged authorities to stop colluding with an abusive male “guardianship” system which controls women’s lives and limits their personal freedoms, including detaining women accused of leaving home without permission or having sex outside marriage and subjecting them to humiliating “virginity tests”.

Freedom of Movement

Freedom of movement is the right to move around freely as we please – not just within the country we live in, but also to visit others. But many women face real challenges when it comes to this. They may not be allowed to have their own passports, or they might have to seek permission from a male guardian in order to travel.

For example, recently in Saudi Arabia there has been a successful campaign to allow women to drive, which had previously been banned for many decades. But despite this landmark gain, the authorities continue to persecute and detain many women’s rights activists, simply for peacefully advocating for their rights.

FEMINISM AND WOMEN’S RIGHTS

When looking at women’s rights it’s helpful to have an understanding of feminism. At its core, feminism is the belief that women are entitled to political, economic, and social equality. Feminism is committed to ensuring women can fully enjoy their rights on an equal footing with men.

Intersectional Feminism

Intersectional feminism is the idea that all of the reasons someone might be discriminated against, including race, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, economic class, and disability, among others, overlap and intersect with each other. One way of understanding this would be to look at how this might apply in a real world setting, such as Dominica , where our research has shown that women sex workers, who are often people of colour, or transgender, or both, suffer torture and persecution by the police.

HOW ARE WOMEN’S RIGHTS BEING VIOLATED?

Gender inequality.

Gender inequality could include:

Gender-Based Violence

Gender-based violence is when violent acts are committed against women and LGBTI people on the basis of their orientation, gender identity, or sex characteristics. Gender based violence happens to women and girls in disproportionate numbers.

Women and girls in conflict are especially at risk from violence, and throughout history sexual violence has been used as a weapon of war. For example, we have documented how many women who fled attacks from Boko Haram in Nigeria have been subjected to sexual violence and rape by the Nigerian military .

Globally, on average 30% of all women who have been in a relationship have experienced physical and/or sexual violence committed against them by their partner. Women are more likely to be victims of sexual assault including rape, and are more likely to be the victims of so-called “honour crimes”.

Violence against women is a major human rights violation. It is the responsibility of a state to protect women from gender-based violence – even domestic abuse behind closed doors.

Sexual Violence and Harassment

Sexual harassment means any unwelcome sexual behaviour. This could be physical conduct and advances, demanding or requesting sexual favours or using inappropriate sexual language.

Sexual violence is when someone is physically sexually assaulted. Although men and boys can also be victims of sexual violence, it is women and girls who are overwhelmingly affected.

Workplace Discrimination

Often, women are the subject of gender based discrimination in the workplace. One way of illustrating this is to look at the gender pay gap . Equal pay for the same work is a human right, but time and again women are denied access to a fair and equal wage. Recent figures show that women currently earn roughly 77% of what men earn for the same work. This leads to a lifetime of financial disparity for women, prevents them from fully exercising independence, and means an increased risk of poverty in later life.

Discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity

In many countries around the world, women are denied their rights on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity, or sex characteristics . Lesbian, bisexual, trans and intersex women and gender non-confirming people face violence, exclusion, harassment, and discrimination Many are also subjected to extreme violence , including sexual violence or so called “corrective rape” and “honour killings.”

WOMEN’S RIGHTS AND INTERNATIONAL LAW

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) (1979) is a key international treaty addressing gender-based discrimination and providing specific protections for women’s rights.

The convention sets out an international bill of rights for women and girls, and defines what obligations states have make sure women can enjoy those rights.

Over 180 states have ratified the convention.

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO STAND UP FOR WOMEN’S RIGHTS?

Women’s rights are human rights.

It might seem like an obvious point, but we cannot have a free and equal society until everyone is free and equal. Until women enjoy the same rights as men, this inequality is everyone’s problem.

Protecting women’s rights makes the world a better place

According to the UN, “gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls is not just a goal in itself, but a key to sustainable development, economic growth, and peace and security”. Research has shown this to be the case – society gets better for everyone when women’s rights are upheld and taken seriously.

We’re stronger when we work together

Although grassroots movements have done so much to effect change, when everyone comes together to support women’s rights we can be so much stronger. By working alongside individual activists and campaigners on the ground as well as running our own targeted campaigns, movements such as Amnesty International can form a formidable vanguard in the fight for women’s rights.

RELATED CONTENT

Iranti and amnesty international mark international transgender day of visibility, understanding the long roots of violence in the occupied palestinian territories and israel , kyrgyzstan: amnesty international secretary general agnès callamard’s call to veto restrictive ngo law, tunisia: authorities’ targeting of lawyers undermines access to justice, nigeria: icc must not dash the hope of survivors of atrocities by the military.

📕 Studying HQ

Comprehensive argumentative essay example on the rights of women, rachel r.n..

- February 20, 2024

- Essay Topics and Ideas

What You'll Learn

Women’s rights have been a significant focal point in the ongoing discourse on social justice and equality. The struggle for women’s rights is deeply rooted in history, marked by milestones and setbacks. While progress has undeniably been made, there remain persistent challenges that necessitate continued advocacy and action. This essay argues that the advancement of women’s rights is not only a matter of justice and equality but also a fundamental imperative for societal progress.(Comprehensive Argumentative essay example on the Rights of Women)

The historical context of women’s rights is marked by a legacy of systemic discrimination, limited opportunities, and societal norms that perpetuated gender inequality. From the suffragette movement to the fight for reproductive rights, women have consistently challenged oppressive structures. The recognition of women’s rights as human rights, as articulated in international conventions, underscores the global commitment to address historical injustices and promote gender equality.(Comprehensive Argumentative essay example on the Rights of Women)

One crucial aspect of women’s rights is economic empowerment . The gender pay gap and limited access to economic resources have persisted despite advancements in the workplace. Empowering women economically not only contributes to their individual well-being but also enhances overall societal prosperity. Research consistently demonstrates that economies thrive when women actively participate in the workforce and have equal opportunities for career advancement.(Comprehensive Argumentative essay example on the Rights of Women)

Education is a powerful catalyst for social change, and ensuring equal access to education for girls and women is integral to advancing women’s rights. When women are educated, they become catalysts for positive change within their communities. Educated women are more likely to make informed decisions about their lives, contribute meaningfully to society, and break the cycle of poverty.

Rights Securing women’s rights includes safeguarding their reproductive health and rights. Access to comprehensive healthcare, including reproductive services, is essential for women to have control over their bodies and make autonomous choices about family planning. Policies that prioritize women’s health contribute to a healthier and more equitable society.(Comprehensive Argumentative essay example on the Rights of Women)

Violence Against Women Addressing and preventing violence against women is a critical component of the women’s rights agenda. Gender-based violence not only inflicts harm on individual women but also perpetuates a culture of fear and inequality. Legal frameworks, awareness campaigns, and support services are essential tools in combating violence against women and ensuring their safety and well-being.(Comprehensive Argumentative essay example on the Rights of Women)

In conclusion, the advancement of women’s rights is not only a moral imperative but also a crucial factor in fostering societal progress. A comprehensive approach that addresses historical injustices, economic disparities, educational opportunities, reproductive rights, and violence against women is essential. As we strive for a more equitable future, it is imperative that individuals, communities, and governments actively support and promote women’s rights, recognizing that the empowerment of women is synonymous with the advancement of society as a whole.(Comprehensive Argumentative essay example on the Rights of Women)

80 Topic Ideas for Your Argumentative Essay

- Universal Basic Income

- Climate Change and Environmental Policies

- Gun Control Laws

- Legalization of Marijuana

- Capital Punishment

- Immigration Policies

- Healthcare Reform

- Artificial Intelligence Ethics

- Cybersecurity and Privacy

- Online Education vs. Traditional Education

- Animal Testing

- Nuclear Energy

- Social Media Impact on Society

- Gender Pay Gap

- Affirmative Action

- Censorship in the Media

- Genetic Engineering and Designer Babies

- Mandatory Vaccinations

- Electoral College vs. Popular Vote

- Police Brutality and Reform

- School Uniforms

- Space Exploration Funding

- Internet Neutrality

- Autonomous Vehicles and Ethics

- Nuclear Weapons Proliferation

- Racial Profiling

- Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide

- Cultural Appropriation

- Socialism vs. Capitalism

- Mental Health Stigma

- Income Inequality

- Renewable Energy Sources

- Legalization of Prostitution

- Affirmative Consent Laws

- Education Funding

- Prescription Drug Prices

- Parental Leave Policies

- Ageism in the Workplace

- Single-payer Healthcare System

- Bullying Prevention in Schools

- Government Surveillance

- LGBTQ+ Rights

- Nuclear Disarmament

- GMO Labeling

- Workplace Diversity

- Obesity and Public Health

- Immigration and Border Security

- Free Speech on College Campuses

- Alternative Medicine vs. Conventional Medicine

- Childhood Vaccination Requirements

- Mass Surveillance

- Renewable Energy Subsidies

- Cultural Diversity in Education

- Youth and Political Engagement

- School Vouchers

- Social Justice Warriors

- Internet Addiction

- Human Cloning

- Artistic Freedom vs. Cultural Sensitivity

- College Admissions Policies

- Cyberbullying

- Privacy in the Digital Age

- Nuclear Power Plants Safety

- Cultural Impact of Video Games

- Aging Population and Healthcare

- Animal Rights

- Obesity and Personal Responsibility

- Reproductive Rights

- Charter Schools

- Military Spending

- Immigration and Economic Impact

- Mandatory Military Service

- Workplace Harassment Policies

- Cultural Globalization

- Criminal Justice Reform

- Immigration Detention Centers

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Internet Censorship

- Discrimination in the Workplace

- Space Colonization

Brownlee, K. (2020). Being sure of each other: an essay on social rights and freedoms. Oxford University Press, USA. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=kTjpDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Argumentative+essay+example+on+the+Rights+of+Women&ots=oysLrPE6ux&sig=ANTnu_5AH4_3PMfGG0XdMzxBpLA

Start by filling this short order form order.studyinghq.com

And then follow the progressive flow.

Having an issue, chat with us here

Cathy, CS.

New Concept ? Let a subject expert write your paper for You

Have a subject expert write for you now, have a subject expert finish your paper for you, edit my paper for me, have an expert write your dissertation's chapter, popular topics.

Business StudyingHq Essay Topics and Ideas How to Guides Samples

- Nursing Solutions

- Study Guides

- Free Study Database for Essays

- Privacy Policy

- Writing Service

- Discounts / Offers

Study Hub:

- Studying Blog

- Topic Ideas

- How to Guides

- Business Studying

- Nursing Studying

- Literature and English Studying

Writing Tools

- Citation Generator

- Topic Generator

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Conclusion Maker

- Research Title Generator

- Thesis Statement Generator

- Summarizing Tool

- Terms and Conditions

- Confidentiality Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Refund and Revision Policy

Our samples and other types of content are meant for research and reference purposes only. We are strongly against plagiarism and academic dishonesty.

Contact Us:

📞 +15512677917

2012-2024 © studyinghq.com. All rights reserved

- SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY

- DEVELOPMENT & SOCIETY

- PEACE & SECURITY

- HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS

- HUMAN RIGHTS

Women’s Rights are Human Rights

Written as part of the global campaign for the 16 Days of Activism against Gender-based Violence, this article includes contributions from members of the United Nations University Institute on Globalization, Culture and Mobility ( UNU-GCM ) research team: Megha Amrith, Inés Crosas, Jane Freedman, Cecilia Gordano, Marta Guasp, Yu Kojima, Parvati Nair, Marija Obradovic, and Aishih Webhe-Herrera.

Women’s rights are human rights. It may seem obvious, but it bears repeating today on Human Rights Day .

The 16 Days of Activism against Gender-based Violence is an international campaign symbolically linking 25 November, the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, to 10 December, Human Rights Day. The team at the UNU Institute for Globalization, Culture and Mobility ( UNU-GCM ), building on our current research program on female agency, mobility and socio-cultural change, has participated in the 16 Days of Activism with a campaign on our Facebook and Twitter highlighting issues including the importance of language, women with disabilities, migrant women and refugees, and art as activism.

We are using our research to raise awareness on these pressing concerns facing women today, and particularly applying our research to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 5 on gender equality. SDG 5 seeks to end all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere, with a particular focus on eliminating all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation.

UN special meeting in observance of the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women. Photo: © UN Photo /Cia Pak.

Language, hate speech and cyber violence

“Language is not neutral: it has an active role in our understanding of diverse realities, our practices and behaviours,” says Cecilia Gordano. She draws attention to a situation when local news reports referred to various “passion killings” that left several women “dead”, arguing that “it’s high time we improved the vocabulary to name gender-based crimes and leave behind the passive voice: women do not just ‘die’, they are ‘killed’, mostly by intimate partners, so they are victims of ‘intimate femicides’.” Media framing , which differs across contexts, plays a critical role in how we perceive gender-based violence.

While the internet provides new opportunities for women’s rights activism, it is also a space where new forms of violence are performed. Aishih Webhe-Herrera explains that “the terms ‘ Feminazi ’ and ‘Gal-Quaeda’ are gaining visibility in current lingo to refer to feminists who denounce everyday sexism, gender stereotyping, and gender discrimination. They are used to shun and silence feminists by delegitimizing their claims, harassing them verbally, publicly and privately. They also promote a misleading understanding of feminism(s) and the collective project of gender equality, which are viewed as an attack on the universalist and degendered ‘rights’ and ‘justice’ of what Michael Kimmel calls ‘Angry White Men’. With striking parallelisms with far right discourses, the popularisation of this terminology in the media and even everyday conversations are clear examples of hate speech against women, and more precisely, gender-based violence against women and girls.”

Nils Muižnieks , the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, points out that “hate speech against women is a long-standing, though underreported problem in Europe”. Not only are these words an attack on women’s right to freedom of expression, but they also violate women’s human rights to privacy, dignity, non-discrimination and life free from violence.

These virtual forms of violence have concrete consequences, as Webhe-Herrera explains that “the spread of this terminology also incites to discrimination, violence and gender hatred against feminist and women’s human rights campaigners, which has forced several feminist bloggers either to adopt a pseudonym to remain safe in the blogosphere or to abandon their virtual platforms and public activism altogether.”

Women with disabilities

Certain groups of women are more vulnerable to violence due to social marginalization. On 3 December for the International Day of Persons with Disabilities Inés Crosas drew attention to women with disabilities, who suffer from among the highest levels of gender-based violence. Nearly 80% of women with a disability are victims of violence , and they are three times more likely to experience abuse compared with “non-disabled women”.

Crosas argues that “this reality seems to be overlooked and these subjects totally misrepresented, since many institutions lack the necessary means to deal with this specific type of violence and data and statistics are often hard to find. As activist groups and scholars point out, the roots of this ‘normalization’ of violence come from prevailing stereotypes and prejudices against women with disabilities, which are sustained through persistent patriarchal and ableist [ableism is discrimination in favour of able-bodied people] notions. It is the hegemonic social construction of ‘woman’ and ‘disability’ which makes this collective particularly vulnerable and imposes deep communicational, attitudinal and structural barriers upon them in their daily life. Therefore, in order to change this situation, social cooperation and awareness is the first, and most important, step.”

The research book Gènere i Diversitat Funcional: una Violència Invisible (Functional Diversity and Gender: An Invisible Violence) provides an in-depth examination of the main causes and consequences of gender-based violence against women with disabilities and exposes good practices for dealing with it.

Migrant women and refugees

Migrant women are another group that is socially marginalized, rendering them even more vulnerable to gender-based violence.

Domestic violence poses a particular challenge for migrant women. As we explained in a previous article , any woman suffering from domestic abuse struggles with how to handle the situation. The problem is doubly difficult for immigrant women, who face additional barriers to reporting violence and accessing services. Migrant women must be empowered to denounce domestic violence and access appropriate support without fear of losing their legal residency status. Violence that takes place in the private sphere is a public issue: it is a violation of women’s human rights that the State has the responsibility to prevent.

Parvati Nair adds that “gender-based violence in domestic contexts is not a one-off event. Even if sporadic, it is the symptom of a power relation where intimacy becomes confused with violence. In the film Te doy mis ojos (Take My Eyes) (directed by Icíar Bollaín, 2003), we see how Pilar constantly scans her partner’s moods, trying to pre-empt the moment when his mood will turn. As such, gender-based violence turns the home into a place of fear and dread. It is, therefore, a form of violence that is as much psychological as it is physical.”

Sudanese refugees in Iridimi Camp in Chad. Photo: © UN Photo /Eskinder Debebe.

The gender-based violence that migrant women experience is not confined to the domestic sphere. “Migrant women are vulnerable to violence at all stages of their journey due to gendered inequalities and relations of domination,” explains Jane Freedman . “Current EU policies restricting migration exacerbate migrant women’s vulnerability. The only way to improve these women’s security is through a genuine commitment to providing safe and legal routes for migration and/or claiming asylum.”

Armed conflict puts women in a particularly vulnerable situation, and protecting female refugees against sexual and gender-based violence in camps remains a major challenge. “Staying in a refugee camp within the country of origin or seeking protection elsewhere brings serious threats to women’s security, freedom and health,” explains Marija Obradovic.

“The international community has long resolved to end this scourge. Yet, despite declarations and resolutions, current reports show that protecting female refugees from gender based violence remains a complex problem. This challenge is solvable, however, as it largely a matter of policy not adequately implemented, and world events prove that implementation should be prioritized.”

The precarity of female refugees often goes unnoticed, and this is especially true in the case of minority groups, such as the Rohingya in Myanmar. “Given their status as women, stateless and part of an ethno-religious minority, Rohingya women (and girls) are particularly vulnerable to sexual and gender-based violence that can affect not only their physical and psychological development but can restrict the socio-economic opportunities available to them both within Myanmar and in their new country of residence,” notes Yu Kojima.

She emphasizes that “it is clear that improved and more coordinated policy efforts are needed among key government agencies and between women’s rights and pro-migrants groups and international agencies in order to begin combating the wider scope of sexual and gender-based violence that Rohingya refugee and migrant women are at risk of during flight and in the country of asylum. Because of the magnitude and seriousness of this challenge, the issue of sexual and gender based violence involving Rohingya women deserves more serious international attention.”

Human trafficking frequently involves the forced movement of people across borders, and it is a form of violence that disproportionately targets women. The UN has made trafficking a focus of the International Day for the Abolition of Slavery , which falls during the 16 Days Campaign on 2 December. Human trafficking should not be conflated with slavery, but action is needed in order to advance policies that prevent trafficking, rescue victims and provide for reintegration and prosecute traffickers. A holistic human rights approach is critical to respect the dignity of all victims of trafficking while working toward its eradication.

Art as activism

Across the world, activists are finding creative strategies to bring attention to women’s human rights. “Literature, music, performance, and the arts are powerful tools that reach wide sectors of society, appealing to their sensitivities, interests and worlds in languages far removed from the realm of international human rights law, but intimately connected to it,” argues Webhe-Herrera.

She discusses “writers, artists, musicians, performers: all of them are raising their voices to denounce femicides or feminicidios, the consistent and massive murder of women in Ciudad Juárez (Chihuahua, México) and worldwide. With more than 400 women assassinated in this city since 1994, and thousands disappeared, writers and artists engage with this feminicidal reality in their works to render it visible, and to claim state accountability for this violation of women’s human right to life and to a life free from violence, as enshrined in the 1994 Convention Belém do Pará and the 2011 Istanbul Convention .”

Webhe-Herrera continues, “good examples of human rights ’artvocay’ can be found in the works of Chicana writer Ana Castillo , who has published several poems, a novel and a play about it, and London visual artist Tamsyn Challenger, whose art installation 400 Women consists of 175 portraits of different women killed as a result of gender-based violence in the Mexican-American borderland.”

Gordano gives another example of Mexican artist Elina Chauvet, who collected 33 pairs of women shoes painted red in Ciudad Juárez and arranged them on the public space in 2009. She called it ‘ Zapatos Rojos ’ [Red Shoes] and conceived it as “a meeting of art and collective memory” to rise awareness on feminicides, the most extreme materialization of gender-based violence. “It is through the ethics and aesthetics, through absence and visibility [that] red shoes show the void left by the daughters, sisters, mothers and wives.” Her artistic intervention has been replicated in various cities in Latin and North America and Europe.

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon at the opening of “The Transformative Power of Art” Exhibition. Photo: © UN Photo /Evan Schneider.

Photography is another powerful medium for advocacy. Megha Amrith tells the story of Xyza Cruz Bacani, a Filipina domestic worker turned photographer. “Her photographs , documenting migrant domestic workers in a Hong Kong shelter who escaped physical and mental abuse, won her a photography scholarship for raising awareness about the grave situations that migrant domestic workers live through. In this new series of photographs, she demonstrates how gender-based violence and labour abuses are common experiences among migrant women across countries and continents,” explains Amrith.

Nair also suggests that “this is an apt time to reflect on the work of the Indian-American photographer Fazal Sheikh, who, in his photo-essays Ladli and Moksha , focuses on the social structures in contemporary India that relegate women to disempowerment within severely patriarchal structures. Through conversations and photographs, Sheikh portrays the untapped potential and the resilience of these women and girls.”

Webhe-Herrera says that “these works represent a global cry for gender and social justice in the face of personal, collective and state violence against women. They also open a creative and political space from which to raise awareness about global violations of women’s human rights, and compel (inter)national actors to take responsibility for the massacre of the female population across the globe.”

The way forward

The UN took a major step in recognizing women’s rights as human rights in the 1993 Vienna Declaration . Campaigns such as the 16 Days of Activism draw attention to the challenges that we still face so that we can continue making the necessary policies and changing attitudes to fulfill women’s human rights.

This year, the focus of the 16 Days Campaign is on the relationship between militarism and the right to education. As such, it is essential to consider the impact of ongoing conflicts across the world on education, particularly for young girls who are living in situations of conflict or who have been displaced.

In Syria , Marta Guasp explains that “[the] ongoing crisis has left almost 3 million Syrian children out of school and puts their future at risk”. Guasp argues that “given the mobility of families, active conflict and limited humanitarian access, the international community will need to look at ways to find more suitable and effective solutions to a long term education response to address the needs of out of school children, boys and girls, in Syria.”