An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Gerontologist

Critical Perspectives on Successful Aging: Does It “Appeal More Than It Illuminates”?

Stephen katz.

1 Department of Sociology, Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada.

Toni Calasanti

2 Department of Sociology, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg.

“Successful aging” is one of gerontology’s most successful ideas. Applied as a model, a concept, an approach, an experience, and an outcome, it has inspired researchers to create affiliated terms such as “healthy,” “positive,” “active,” “productive,” and “effective” aging. Although embraced as an optimistic approach to measuring life satisfaction and as a challenge to ageist traditions based on decline, successful aging as defined by John Rowe and Robert Kahn has also invited considerable critical responses. This article takes a critical gerontological perspective to explore such responses to the Rowe–Kahn successful aging paradigm by summarizing its empirical and methodological limitations, theoretical assumptions around ideas of individual choice and lifestyle, and inattention to intersecting issues of social inequality, health disparities, and age relations. The latter point is elaborated with an examination of income, gender, racial, ethnic, and age differences in the United States. Conclusions raise questions of social exclusion and the future of successful aging research.

Successful aging is one of gerontology’s most successful ideas. Although historical traces of it can be found in Renaissance texts ( Gilleard, 2013 ), the modern gerontological idea emerged in the 1950s and was later crystallized in the work of John Rowe and Robert Kahn. Successful aging has been churned into theoretical paradigms, health measurements, retirement lifestyles, policy agendas, and antiaging ideals. Researchers have also generated a discourse of kin terms such as “productive aging,” “positive aging,” “optimal aging,” “effective aging,” “independent aging,” and “healthy aging,” which together promote (a) an industry of books, conferences, journals, funding, and research programs, (b) web sites (e.g., http://healthyandsuccessfulaging.wordpress.com/ ), and (c) institutional identities. For example, Wayne State University’s Institute of Gerontology’s banner is “Promoting Successful Aging in Detroit and Beyond,” and Florida State University has a new “Institute of Successful Longevity.” Indeed, Carol Ryff’s (1982) comment, now 30 years on, that, “like goodness, truth, and other human ideals, successful aging may appeal more than it illuminates” (p. 209), still holds true. This essay examines the theoretical development of successful aging and the critical literature that has ensued, with a focus on the disparities of aging and social inequality in the United States today.

Robert Havighurst (1961) provided an early formulation of successful aging. In the first issue of The Gerontologist , he optimistically described successful aging in terms of life satisfaction that emphasized “the greatest good for the greatest number” (p. 8). Havighurst and his associates saw that successful aging was both an adaptable theory and a testable experience. Furthermore, it could apply to both disengagement and activity theories, which were otherwise contending models of retirement living at the time. Later, large-scale studies such as the First Duke Longitudinal Study ( Palmore, 1979 ) multiplied the factors and predictors for successful aging over longer periods of time. Although Havighurst (1961) cautioned that “no segment of a society should get satisfaction at a severe cost to some other segment” (p. 8), the enduring appeal of successful aging was its positive characterization of the aging process (“The Measurement of Life Satisfaction” ( Neugarten, Havighurst, & Tobin, 1961 ) is listed at the top of Ferraro and Schafer’s (2008) “Gerontology’s Greatest Hits” for most frequently cited social science article in the Journals of Gerontology ). Successful agers were satisfied, active, independent, self-sufficient, and, above all, defiant of traditional narratives of decline. Thus, for gerontologists, successful aging scholarship combined antiageist advocacy with empirical research. At the same time, the research paralleled the postwar American preoccupation with individual adaptability and adjustment in later life, a relationship that became a mainstay in the successful aging paradigm developed by John Rowe and Robert Kahn (see Dillaway & Byrnes, 2009 ).

Rowe and Kahn (1987, 1997, 1998 ) introduced a more medical framework in which usual aging and successful aging could be differentiated: The former term referred to nonpathologic but higher risk individuals and the latter term referred to lower risk and higher functioning individuals. Although their earlier work equated successful aging with the absence or avoidance of disease, they later widened it to include cognitive and lifestyle factors. What Rowe and Kahn offered was a hypothesis that merged physical, cognitive, and lifestyle factors with measurable indicators of disease and disability. In effect, Rowe and Kahn maintained that the appropriate lifestyle could result in successful aging, which they defined as (a) forestalling disease and disability, (b) maintaining physical and mental function, and (c) social engagement ( Rowe and Kahn, 1998 , p. 38). According to Rowe, the “new gerontology” recognized that successful aging requires “full engagement in life, including productive activities and interpersonal relations” in addition to health maintenance ( Rowe, 1997 , p. 367). To their credit, Rowe and Kahn, following their predecessors, evoked a much-needed optimistic narrative of positive aging in their consistent emphasis on self-directed health across the life course; that indeed one’s experiences in later life could be measured in terms of success, rather than dowsed in conventional expectations for failure. At the same time, however, by aligning their “new gerontology” so strongly to the role of individual volition and lifestyle in maintaining, improving, and even reversing disabling problems, Rowe and Kahn moved successful aging further from the social determinants of health. This issue, along with other limitations in the successful aging paradigm, is elaborated subsequently.

Responses, Limitations, and Exclusions

Although the successful aging literature has grown vast, for purposes of brevity here we divide the main responses to the Rowe–Kahn paradigm into the following categories: (a) Empirical and methodological limitations, (b) theoretical assumptions around ideas of choice and lifestyles, and (c) lack of attention to intersecting social inequalities and age relations.

Successful Aging: Limitations and Modifications From Within

One of the greatest challenges faced by those working within the successful aging framework is the inconsistency across studies in terms of conceptualization and measures, so much so that the meaning of successful aging is often more implied than delineated ( Knight & Ricciardelli, 2003 ; Phelan, Anderson, LaCroix, & Larson, 2004 ; Pruchno, Wilson-Genderson, Rose, & Cartwright, 2010 ). In fact, in their review of quantitative studies, Depp and Jeste (2006) identified 29 definitions in the 28 studies they examined, with most (but not all) including a measure of disability or physical function. This variability alone presents limitations to research on successful aging.

Researchers concerned with the empirical and methodological limitations of successful aging have responded by extending or adapting successful aging criteria in alternative ways. The most prominent example is the work of Baltes and Baltes (1990) and their model of “selective optimization with compensation” in which aging individuals compensate for losses and limitations by adjusting their expectations and goals to focus on those with the highest priorities. Curb and coworkers (1990) propose the notion of “effective aging” to encompass both successful agers and those in the “middle ground” who face physiologic losses and disease (p. 828). Martin and Gillen develop a “spectrum model of aging” to broaden successful aging research at the level of individual development over the life course with the aim of improving care and quality of life ( Martin & Gillen, 2013 ).

These innovative exercises often respond to a perceived methodological shortcoming of the Rowe–Kahn paradigm: Its neglect of what aging, successful or otherwise, means to older people, a situation addressed through qualitative discovery and self-reporting studies ( Bowling, 2006 ; Fagerström & Aarsten, 2013 ; Rossen, Knafl, & Flood, 2008 ; Strawbridge, Wallhagen, & Cohen, 2002 ; Strawbridge & Wallhagen, 2003 ; Torres & Hammarström, 2009 ). Although life is lived as a subjective process in time through a diversity of contexts and relationships, “the successful aging paradigm seems to define success as an outcome … a game which can be won or lost on the basis of whether or not individuals are diagnosed as successful or usual” ( Dillaway & Byrnes, 2009 , p. 706). When the voices of older individuals are included, we learn that disability and disease are not necessarily experienced in terms of unsuccessful aging nor is successful aging a precondition of aging well, and this has led some scholars to modify the model to incorporate coping and other strategies ( Phelan et al., 2004 ; Van Wagenen, Driskell, & Bradford, 2013 ). And the repeatedly demonstrated discrepancy between the objective criteria (variously measured) and older individuals’ experiences and definitions ( Montross et al., 2006 ) of successful aging has resulted in researchers’ calls to alter the notion of successful aging by combining subjective and objective dimensions. For instance, Pruchno and coworkers (2010) argue for the utility of exploring both dimensions simultaneously, rendering a typology “of successful aging, whereby some people are successful according to both definitions, others are successful according to neither, and still others are successful according to one, but not the other definition” (p. 822).

Our discussion of these limitations, debates over measurements and appropriate criteria, and modifications is not undertaken in order to adjudicate these, but to elucidate them so that we might comment upon their ramifications for gerontology, a topic to which we turn in the final section of this article. Here, we note that regardless of how these debates are decided, their resolution does not move them away from the successful aging framework itself but instead serves to further its prominence and use.

Individual Choice and Lifestyles

The successful aging paradigm has drawn criticism for its assumptions around concepts of individual choice, agency, and lifestyle ( Katz, 2013 ). Individualist culture shapes Rowe and Kahn’s formulation about successful aging, which not only emphasizes successes and failures, but also individual responsibility for same. In their book ( Rowe and Kahn, 1998 ), they wrote: “Our main message is that we can have a dramatic impact on our own success or failure in aging. Far more than is usually assumed, successful aging is in our own hands.” (p. 18, emphasis ours). And “To succeed … means having desired it, planned it, worked for it. All these factors are critical to our view of aging which … we regard as largely under the control of the individual. In short, successful aging is dependent upon individual choices and behaviors. It can be attained through individual choice and effort” (p. 37). However the problems of individual choice go back to the lifestyle ideas of sociologists Georg Simmel and Max Weber. Simmel thought that urban modernity created “a tendency towards extreme subjectivism,” a kind of coerced individualism (Simmel in Frisby, 1992 , p. 76) that was also constructive of new characters at the edge of cosmopolitan life (e.g., the stranger, the modern prostitute, the adventurer). Max Weber’s critique of lifestyles was part of his analysis of status and class division. Weber claimed that, while people may have pretensions to certain status-bound lifestyles, “the possibility of maintaining the life-style of a status group is usually conditioned on economics” ( Weber in Runciman, 1978 , p. 52).

For both Simmel and Weber, lifestyle choices and individual volition are always constrained by the material conditions that accumulate lifelong advantages and disadvantages. In this vein, Pierre Bourdieu (1984) modernized the critique of lifestyle practices to include cultural capital, whereby individual choices are disclosed as the products of privilege; hence, those with the most access to health benefits and services also frame their health behaviors within positive lifestyle outcomes. Like Bourdieu, Anthony Giddens (1991 , 1999 ) forefronts lifestyle in his theories of reflexive and posttraditional individualism, arguing that the structuring of life chances limit individual lifestyle options. The critical traditions of Simmel, Weber, Bourdieu, and Giddens can be seen in the work of contemporary sociologists of aging, such as Hendricks and Hatch (2009) , who aver that “lifestyles and social resources deriving from social arrangements work in tandem to structure the life course, yielding cumulative advantages or disadvantages leading to one or another experience in older age” (p. 440).

These and related critiques make it clear that aging research has to theorize lifestyle, choice, health, and successful aging beyond personal choice because lifestyles are configured by differential opportunities and relations of social inequality ( Calasanti and King, 2011 ; Dannefer, 2003 , 2006 ). However, these critical perspectives on lifestyle are lost in the successful aging research because individual choice is reduced to decontextualized health-relevant choices, such as smoking, diet, or exercise ( Franklin & Tate, 2009 ). For example, policy recommendations such as A Survey in Europe on Nutrition and the Elderly: A Concerted Action (2003) conclude that “the identification of people with unhealthy lifestyle habits, and finding ways to improve lifestyle habits of specific target groups is the challenge of future prevention programmes in young and elderly subjects” ( Haveman-Nies, de Groot, & van Staveren, 2003 , p. 432).

Where successful aging research conceives of health advantages and disadvantages as the results of individual responsibility, buoyed by media narratives of aging winners and losers ( Rozanova, 2010 ), it thus fails to acknowledge social relations of power, environmental determinants of health, and the biopolitics of health inequalities. Indeed, lifestyle and individual volition fit a contemporary consumerist, neoliberal, and entrepreneurial style of thought that dominates health and retirement politics. Where this style of thought intersects with person-centered explanations of health, such as those pronounced in successful aging discourse, the result can be a powerful opposition to state welfare entitlements that “defeat[s] the political lobbying for more social support and resources” ( Dillaway & Byrnes, 2009 , p. 708).

Intersecting Social Inequalities and Age Relations

The most contentious critiques of the successful aging paradigm target those whom it excludes. For example, scholars have questioned what successful aging means for groups who live with dependency and disabilities ( Minkler & Fadem, 2002 ). If they are considered unsuccessful agers in theory, then such labeling deeply affects their treatment by health care regimes in practice. Further, if populations are homogenized as either successful or unsuccessful agers, then the diversity of the aging experience is flattened, especially the consequences of social inequalities as they intersect with age relations. These should figure in theories of successful aging more fully than they do, given all that researchers of intersecting inequities have discovered about patterns in spending power and access to health care, which remain two critical pathways to successful aging as defined by Rowe and Kahn. The advantages and disadvantages that accrue across the life course become more salient in later life. The time in which people are to be “successful agers” is one in which those aged 65 and older are faced with ageism. To this they bring varying material and social resources (based on the intersections of gender, race, ethnicity, class, and sexuality) with which to resist being subjected to this form of inequality. A brief examination of financial and health resources can demonstrate how social inequalities shape opportunities for and constraints upon successful aging in the United States (similar patterns accrue in many other countries in the global North).

Beginning with income, we note that gender-based differences in earnings persist despite women’s increased employment rates ( DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, & Smith, 2013 , p. 11, Figure 2). Individual choice cannot explain these discrepancies, which prevail despite educational levels and occupational incumbency. For instance, gender comparisons at various occupational levels find that women’s absolute earnings are highest when they have obtained a professional degree; yet the gap between their income and that of men’s with a similar degree (72%) is also greater than at any other educational level ( AAUW, 2013 , p. 10, Figure 6). Such differences are further shaped by their intersections with race and ethnicity such that White women out-earn racial and ethnic minority women at each educational level ( AAUW, 2013 , p. 14, Figure 7). Similarly, although women’s occupations pay less overall than do men’s, women who work in traditionally male jobs still earn less than their male peers; and even in female-dominated occupations, such as registered nursing, women’s earnings are only 91% of men’s ( AAUW, 2013 ).

Similar racial and ethnic patterns of economic inequalities persist. In 2012, the ratio of Black to non-Hispanic White median income was 0.58, not significantly changed from 1972, whereas the ratio of Hispanic to non-Hispanic White median income actually declined from 0.74 to 0.68 ( DeNavas-Walt et al., 2013 , p. 8). Poverty rates also reflect these disparities; only 9.7% of non-Hispanic Whites were poor in 2012 compared with 11.7%, 25.6%, and 27.2% of Asians, Hispanics, and Blacks, respectively ( DeNavas-Walt et al., 2013 , pp. 14–15). Such systemic differences in earnings become magnified in a time of recession where impacts of economic downturns are not evenly dispersed. Racial and ethnic groups with the lowest incomes (Blacks and Hispanics) saw the largest percentage decreases in the 2008 recession ( DeNavas-Walt et al., 2009 , p. 7), while class-based income inequality increased ( DeNavas-Walt et al., 2013 ). Older workers also face increasing odds of losing their jobs and difficulty finding comparable employment in later life ( Johnson, 2009 ; Roscigno, 2010 ). Once unemployed, Black and Hispanic older workers are less likely than non-Hispanic Whites to find new jobs and thus face long-term joblessness or leave the labor force altogether; Hispanic women are particularly disadvantaged ( Flippen & Tienda, 2000 ) and all such workers lose income for their Social Security and/or other pensions. Ending up in jobs that pay much less than previous occupations furthers their financial woes. Taken together, these factors mean they also will have lower incomes in retirement ( Johnson, 2009 , p. 29).

The results of these employment and income patterns include differences in health and health care, which affect the ability to realize ideals of successful aging. For example, those who have unstable or low-paid work have fewer benefits and lower access to health care, which in turn influences their ability to work and receive higher wages. Racial and ethnic minority members of the working class are more likely to occupy lower skilled jobs that are exposed to toxic working conditions or are physically demanding, thus increasing their health risks. Yet such workers are also less likely to have health insurance coverage of any kind ( Brown, 2009 ; DeNavas-Walt et al., 2013 ; Williams, 2004 ) and tend to receive care in less optimal settings without the benefits of a continuity of care ( Williams, 2004 ). Taken together, racial and ethnic minority groups are more likely to enter old age in poor physical health. Adding to these outcomes, gender relations also influence the ways in which people define and maintain health. For example, scholars have faulted the performance of masculinity for leading men to engage in risky behaviors or to neglect health protective behaviors ( Courtenay, 2000 ). Yet men do attend to their bodies in contexts where good health and functional capacity are connected to masculine ideals and expectations ( O’Brien, Hunt, & Hart, 2005 ).

If different groups enter their later years with varying financial resources, then these deeply affect how they govern their ability to engage in the activities related to successful aging as defined by Rowe and Kahn. Indeed, older men and women have significantly disparate median incomes and average monthly Social Security benefits ( Administration on Aging, 2013 ; Social Security Administration, 2013 ), but given that men’s median income is almost twice as high as women’s, it is obvious that men also have more sources of income. Reliance on Social Security for a large portion of one’s income certainly bodes poorly for financial security in old age; among those who are poor or near poor (below 200% of the federal poverty line), three fourths of their income comes from Social Security ( Issa & Zedlewski, 2011 ). And gender, race, ethnicity, and class all shape the likelihood that one will rely predominantly on Social Security and experience financial strain. Given these financial realities, it follows that many people aged 65 and older—and women more than men, as well as minority group members and poor or working-class people—are constrained in their lifestyle or health choices. This is so despite the availability of Medicare because, while the entitlement enhances older groups’ access to health care, their copayments and deductibles remain problematic to those with low levels of disposable income. In 2012, nine percent of those aged 65 and older are considered poor under the official poverty threshold ($11,011 for an individual 65+). However, this number jumps to 15% when the supplemental poverty measure, which takes such health expenditures into account, is used ( Short, 2013 ).

Again, the intersections between race, ethnicity, gender, and age are salient. Racial ethnic minority group members do not receive equivalent treatment for dementia despite their receipt of Medicare, even when socioeconomic status, health care access and utilization, and comorbidities are considered ( Zuckerman et al., 2008 ). Black Medicare beneficiaries also receive fewer medical procedures and lower quality medical care than do Whites, even under similar conditions of income, insurance, disease, and medical facility ( Williams, 2004 ). Furthermore, because Medicare is more geared toward acute than chronic illnesses, this means that women who have higher rates of chronic disabilities ( Quadagno, 2014 ) pay more out-of-pocket expenses than do men, despite their lower financial means. Such do not appear to be the result of lifestyle decisions or other personal choices but are configured by relations of power. And to the extent that power relations themselves are not dismantled, the inequalities that constrain individual choice will persist, and the call to age successfully will continue to demarcate winners and losers and will itself serve as another marker of group-based differences.

Critical Conclusions

A key contribution of critical gerontology is its reflexive attitude toward the major concepts by which problems of aging are addressed. Successful aging is certainly one such concept. It has animated a controversial space in which almost every branch of gerontology has participated in some way, including the protagonists themselves. In an exchange between Matilda White Riley and Robert Kahn, Riley accused Rowe and Kahn of not taking into account the fact that “changes in lives and changes in social structures are fundamentally interdependent” and thus neglecting “the dependence of successful aging upon structural opportunities” ( Kahn, 1998 , p. 151). Kahn replied that an obstacle to demonstrating “the effects of major structural interventions is the expense and difficulty of mounting such interventions” (p. 151). For Riley, the sociologist, understanding aging requires a vision of group activities and social structures. For Kahn, the scientist, society is a human population laboratory into which social improvement is based on rational intervention. In response to a different criticism concerning the lack of self-reporting in successful aging research ( Strawbridge et al., 2002 ), Kahn says that, despite his and Rowe’s best intentions to invite researchers “to investigate the heterogeneity among older people” and to “encourage people to make lifestyle choices that would maximize their own likelihood of aging well,” he shares the concerns of his critics “that the term successful aging may itself have the unintended effect of defining the majority of the elderly population as unsuccessful and therefore failing. I believe that this problem, to the extent that it exists, reflects a characteristic of contemporary American culture rather than something intrinsic to the concept” ( Kahn, 2002 , p. 726). However, Rowe and Kahn’s well-taken point concerning the importance of exploring heterogeneity again refers to individual differences; this is quite different from group-based differences resulting from social inequalities.

Rowe and Kahn’s work (1998) sought to combat myths of aging, particularly those that rely upon and promulgate narratives of decline. However, the hypothesis that successful aging is a minimization of declines in physical and cognitive health, or in social connections—rather than as a social location different from (and in conflict with) middle age—shows too little of both the social forces that affect success and the groups’ definitions of it. Both access to the means to success, however defined, and the very definition of success itself are matters of social inequality. Ultimately, the power relations that underlie ageism are not challenged ( Calasanti, 2003 ). In part, these power relations derive from a culture in which ageism is so embedded that we may not realize that middle age serves as its implicit standard ( Calasanti, 2003 ). Thus, gerontologists might consider demonstrating the value of diverse, inclusive, less ageist, and less ethnocentric experiences of aging, for example, the Eastern spiritual context of “harmonious aging” ( Liang & Luo, 2012 ). Again, other studies that have modified the successful aging framework by focusing on subjective assessments provide starting points from which to build alternative conceptions that value old age as qualitatively different from middle and other age categories, rather than a time of life defined by loss or lack of success. In Knight and Ricciardelli’s (2003) study, older participants wisely understood the purpose of their aging lives because “it was a time to take things as they came” (p. 237).

As for the future, in both of his responses above, Kahn suggests that greater interdisciplinarity is needed between scientists and social scientists in order to actively improve the lives of older individuals. To this end, we, as sociologists, hope our review of the critiques of successful aging—in concept, theory, and practice—makes a contribution. We also expect that, in the spirit of critical gerontology, the successful aging paradigm in all of its manifestations will continue to inspire passionate debate between the disciplines, to question why certain models fill theoretical voids in gerontology, to be wary of the popular appeal of positive discourses in aging research, to think historically about the concepts we promote and their exclusionary consequences for the people we care about, and to see clearly which interests are served and knowledges mobilized by the ideas we espouse.

- AAUW. (2013). The simple truth about the gender pay gap Retrieved December 26, 2013, from http://www.aauw.org/files/2013/03/The-Simple-Truth-Fall-2013.pdf

- Administration on Aging. (2013). A profile of older Americans: 2012 Retrieved December 28, 2013, from http://www.aoa.gov/AoAroot/Aging_Statistics/Profile/index.aspx

- Baltes P. B., Baltes M. M. (Eds.). (1990). Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences . New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bowling A. (2006). Lay perceptions of successful aging: Findings from a national survey of middle aged and older adults in Britain . European Journal of Aging , 3 , 123–136. 10.1007/s10433-006-0032-2 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bourdieu P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown E. (2009). Work, retirement, race, and health disparities . In Antonucci T. C., Jackson J. S. (Eds.), Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics (Life-course perspectives on late-life health inequalities) (Vol. 29 , pp. 233–249). New York: Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Calasanti T. (2003). Theorizing age relations . In Biggs S., Lowenstein A., Hendricks J.(Eds.), The need for theory: Critical approaches to social gerontology for the 21st century (pp. 199–218). Amityville, NY: Baywood. [ Google Scholar ]

- Calasanti T., King N. (2011). A feminist lens on the third age: Refining the framework . In Carr D., Komp K. (Eds.), Gerontology in the era of the third age (pp. 67–85). New York: Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Courtenay W. H. (2000). Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health . Social Science & Medicine , 50 , 1385–1401. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00390-1 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Curb J. D., Guralnik J. M., LaCroix A. Z., Korper S. P., Deeg D., Miles T., White L. (1990). Effective aging. Meeting the challenge of growing older . Journal of the American Geriatrics Society , 38 , 827–828. 10.1002/ajim.20569 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dannefer D. (2003). Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: Cross-fertilizing age and social science theory . The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 58 , 327–337. 10.1093/geronb/58.6.S327 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dannefer D. (2006). Reciprocal co-optation: The relationship of critical theory and social gerontology . In Baars J., Dannefer D., Phillipson C., Walker A. (Eds.), Aging, globalization and inequality: The new critical gerontology (pp. 103–120). Amityville, NY: Baywood. [ Google Scholar ]

- DeNavas-Walt C., Proctor B. P., Smith J. C. (2009). Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States, 2008. Current Population Reports . Retrieved March, from http://www.census.gov/prod/2009pubs/p60-236.pdf

- DeNavas-Walt C., Proctor B. D., Smith J. C. (2013). U.S. Census Bureau, current population reports, P60–245. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2012 . Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. [ Google Scholar ]

- Depp C. A., Jeste D. V. (2006). Definitions and predictors of successful aging: A comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies . The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry , 14 , 6–20. 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192501.03069.bc [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dillaway H. D., Byrnes M. (2009). Reconsidering successful aging: A call for renewed and expanded academic critiques and conceptualizations . Journal of Applied Gerontology , 28 , 702–722. 10.1177/0733464809333882 [ Google Scholar ]

- Fagerström J., Aarsten M. (2013). Successful ageing and its relationship to contemporary norms: A critical look at the call to ‘age well .’ Recherches sociologiques et anthropologiques , 44 , 51–73. 10.4000/rsa.918 [ Google Scholar ]

- Ferraro K. F., Schafer M. H. (2008). Gerontology’s greatest hits . The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 63 , 3–6. 10.1002/bies.20854 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Flippen C., Tienda M. (2000). Pathways to retirement: Patterns of labor force participation and labor market exit among the pre-retirement population by race, Hispanic origin, and sex . The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 55 , 14–27. 10.1093/geronb/55.1.S14 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Franklin N. C., Tate C. A. (2009). Lifestyle and successful aging: An overview . American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine , Jan.-Feb., 6–11. 10.1177/1559827608326125 [ Google Scholar ]

- Frisby D. (1992). Simmel and since: Essays on Georg Simmel’s social theory . London: Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Giddens A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Giddens A. (1999). Runaway world: How globalization is reshaping our lives . London: Profile Books. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gilleard C. (2013). Renaissance treatises on ‘successful aging.’ Ageing & Society , 33 , 189–215. 10.1017/S0144686X11001127 [ Google Scholar ]

- Haveman-Nies A., de Groot L. C., van Staveren W. A. (2003). Dietary quality, lifestyle factors and healthy ageing in Europe: The SENECA study . Age and Ageing , 32 , 427–434. 10.1093/aje/kwf144 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Havighurst R. J. (1961). Successful aging . The Gerontologist , 1 , 8–13. 10.1093/geront/1.1.8 [ Google Scholar ]

- Hendricks J., Hatch L. R. (2009). Theorizing lifestyle: Exploring agency and structure in the life course . In Bengston V. L., Gans D., Putney N. M., Silverstein M. (Eds.), Handbook of theories of aging (pp. 435–454). New York: Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Issa P., Zedlewski S. R. (2011). Poverty among older Americans, 2009. Urban Institute, Retirement Security Data Brief, No. 1, February. Retrieved August 31, 2011, from http://www.retirementpolicy.org/

- Johnson R. W. (2009). The recession’s impact on older workers . Public Policy & Aging Report , 19 , 26–31. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kahn R. L. (2002). On “Successful aging and well-being: Self-rated compared with Rowe and Kahn” . The Gerontologist , 42 , 725–726. 10.1093/geront/42.6.725 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kahn R. L. (1998). Letters to the Editor . The Gerontologist , 38 , 151. 10.1093/geront/38.2.151a [ Google Scholar ]

- Katz S. (2013). Active and successful aging: Lifestyle as a gerontological idea . Recherches sociologiques et anthropologiques , 44 , 33–49. 10.4000/rsa.910 [ Google Scholar ]

- Knight T., Ricciardelli L. A. (2003). Successful aging: Perceptions of adults aged between 70 and 101 years . International Journal of Aging & Human Development , 56 , 223–245. 10.2190/CG1A-4Y73-WEW8-44QY [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liang J., Luo B. (2012). Toward a discourse shift in social gerontology: From successful aging to harmonious aging . Journal of Aging Studies , 26 , 327–334. 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.03.001 [ Google Scholar ]

- Martin D. J., Gillen L. L. (2013). Revisiting gerontology’s scrapbook: From Metchnikoff to the spectrum model of aging . The Gerontologist . 10.1093/geront/gnt073. Advanced access published July 27. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Minkler M., Fadem P. (2002). “Successful aging”: A disability perspective . Journal of Disability Policy Studies , 12 , 229–235. 10.1177/104420730201200402 [ Google Scholar ]

- Montross L. P., Depp C., Daly J., Reichstadt J., Golshan S., Moore D., … Jeste D. (2006). Correlates of self-rated successful aging among community-dwelling older adults . American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry , 14 , 43–51. 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192489.43179.31 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Neugarten B. L., Havighurst R. J., Tobin S. S. (1961). The measurement of life satisfaction . The Gerontologist , 16 , 134–143. 10.1093/gerontj/16.2.134 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- O’Brien R., Hunt K., Hart G. (2005). ‘It’s caveman stuff, but that is to a certain extent how guys still operate’: Men’s accounts of masculinity and help seeking . Social Science & Medicine , 61 , 503–516. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.008 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Palmore E. (1979). Predictors of successful aging . The Gerontologist , 19 , 427–431. 10.1093/geront/19.5_Part_1.427 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Phelan E. A., Anderson L. A., LaCroix A. Z., Larson E. B. (2004). Older adults’ views of “successful aging”–how do they compare with researchers’ definitions? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society , 52 , 211–216. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52056.x [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pruchno R. A., Wilson-Genderson M., Rose M., Cartwright F. (2010). Successful aging: Early influences and contemporary characteristics . The Gerontologist , 50 , 821–833. 10.1093/geront/gnq041 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Quadagno J. (2014). Aging and the life course (6th ed). New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Google Scholar ]

- Roscigno V. J. (2010). Ageism in the American workplace . Contexts , 9 , 16–21. 10.1525/ctx.2010.9.1.16 [ Google Scholar ]

- Rossen E. K., Knafl K. A., Flood M. (2008). Older women’s perceptions of successful aging . Activities, Adaptation, & Aging , 32 , 73–88. 10.1080/01924780802142644 [ Google Scholar ]

- Rowe J. W. (1997). The new gerontology . Science (New York, N.Y.) , 278 , 367. 10.1126/science.278.5337.367 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rowe J. W., Kahn R. L. (1987). Human aging: Usual and successful . Science (New York, N.Y.) , 237 , 143–149. 10.1126/science.3299702 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rowe J. W., Kahn R. L. (1997). Successful aging . The Gerontologist , 37 , 433–440. 10.1093/geront/37.4.433 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rowe J. W., Kahn R. L. (1998). Successful aging . New York: Random House. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rozanova J. (2010). Discourse of successful aging in The Globe & Mail: Insights from critical gerontology . Journal of Aging Studies , 24 , 213–222. 10.1016/j.jaging.2010.05.001 [ Google Scholar ]

- Ryff C. D. (1982). Successful aging: A developmental approach . The Gerontologist , 22 , 209–214. 10.1093/geront/22.2.209 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Short K. (2013). The Research Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2012 Retrieved December 26, 2013, from http://www.census.gov/prod/2013pubs/p60-247.pdf

- Social Security Administration. (2013). Fast facts and figures about social security: 2013 Retrieved October 4, 2013, from www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/chartbooks/fast_facts/2013/fast_facts13.pdf

- Strawbridge W. J., Wallhagen M. I. (2003). Self-reported successful aging: Correlates and predictors . In Poon L. W., Gueldner S. H., Sprouse B. (Eds.), Successful aging and adaptation with chronic diseases in older adulthood (pp. 1–24). New York: Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Strawbridge W. J., Wallhagen M. I., Cohen R. D. (2002). Successful aging and well-being: Self-rated compared with Rowe and Kahn . The Gerontologist , 42 , 727–733. 10.1093/geront/42.6.727 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Torres S., Hammarström G. (2009). Successful aging as an oxymoron: Older people—with and without home-help care—talk about what aging well means to them . International Journal of Ageing and Later Life , 4 , 23–54. 10.3384/ijal.1652–8670.094123 [ Google Scholar ]

- Van Wagenen A., Driskell J., Bradford J. (2013). “I’m still raring to go”: Successful aging among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults . Journal of Aging Studies , 27 , 1–14. 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.09.001 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weber M. (1922/1978). Classes, status groups and parties . In Runciman W. G. (Ed.), Weber: Selections in translation (pp. 43–56). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Williams D. R. (2004). Racism and health . In Whitfield K. E. (Ed.), Closing the gap: Improving the health of minority elders in the new millennium (pp. 69–79). Washington, DC: Gerontological Society of America. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zuckerman I. H., Ryder P. T., Simoni-Wastila L., Shaffer T., Sato M., Zhao L., Stuart B. (2008). Racial and ethnic disparities in the treatment of dementia among Medicare beneficiaries . The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 63 , 328–333. 10.1093/geronb/63.5.S328 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Advertisement

What Does “Successful Aging” Mean to you? — Systematic Review and Cross-Cultural Comparison of Lay Perspectives of Older Adults in 13 Countries, 2010–2020

- ORIGINAL ARTICLE

- Published: 16 October 2020

- Volume 35 , pages 455–478, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Afton J. Reich 1 , 2 ,

- Kelsie D. Claunch 1 , 3 ,

- Marco A. Verdeja 2 ,

- Matthew T. Dungan 2 ,

- Shellie Anderson 1 , 4 ,

- Colter K. Clayton 1 , 5 ,

- Michael C. Goates 6 &

- Evan L. Thacker ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3813-0885 1 , 2

5144 Accesses

41 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

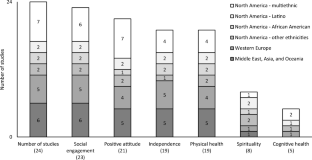

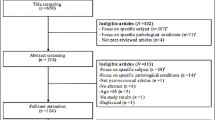

Successful aging is a concept that has gained popularity and relevance internationally among gerontologists in recent decades. Examining lay older adults’ perspectives on successful aging can enhance our understanding of what successful aging means. We conducted a systematic review of peer reviewed studies from multiple countries published in 2010–2020 that contained qualitative responses of lay older adults to open-ended questions such as “What does successful aging mean to you?” We identified 23 studies conducted in 13 countries across North America, Western Europe, the Middle East, Asia, and Oceania. We identified no studies meeting our criteria in Africa, South America, Eastern Europe, North Asia, or Pacific Islands. Across all regions represented in our review, older adults most commonly referred to themes of social engagement and positive attitude in their own lay definitions of successful aging. Older adults also commonly identified themes of independence and physical health. Least mentioned were themes of cognitive health and spirituality. Lay definitions of successful aging varied by country and culture. Our findings suggest that gerontology professionals in fields including healthcare, health psychology, and public health may best serve older adults by providing services that align with older adults’ priority of maintaining strong social engagement as they age. Lay perspectives on successful aging acknowledge the importance of positive attitude, independence, and spirituality, in addition to physical and cognitive functioning.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

“With Age Comes Wisdom:” a Qualitative Review of Elder Perspectives on Healthy Aging in the Circumpolar North

Britteny M. Howell & Jennifer R. Peterson

A Literature Review of Healthy Aging Trajectories Through Quantitative and Qualitative Studies: A Psycho-Epidemiological Approach on Community-Dwelling Older Adults

Alfonso Zamudio-Rodríguez, J.-F. Dartigues, … K. Pérès

Gerotranscendence and Alaska Native Successful Aging in the Aleutian Pribilof Islands, Alaska

Erik S. Wortman & Jordan P. Lewis

Adra, M. G., Hopton, J., & Keady, J. (2015). Constructing the meaning of quality of life for residents in care homes in the Lebanon: Perspectives of residents, staff, and family. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 10 , 306–318.

Google Scholar

Ahaddour, C., Van den Branden, S., & Broeckaert, B. (2020). “What goes around comes around”: Attitudes and practices regarding ageing and care for the elderly among Moroccan Muslim women living in Antwerp (Belgium). Journal of Religion and Health, 59 , 986–1012.

Alley, D. E., Putney, N. M., Rice, M., & Bengtson, V. L. (2010). The increasing use of theory in social gerontology: 1990-2004. Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65 , 583–590.

Amin, I. (2017). Perceptions of successful aging among older adults in Bangladesh: An exploratory study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 32 , 191–207.

Bacsu, J., Jeffery, B., Abonyi, S., Johnson, S., Novik, N., Martz, D., & Oosman, S. (2014). Healthy aging in place: Perceptions of rural older adults. Educational Gerontology, 40 , 327–337.

Baltes, P., & Baltes, M. (1990). Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. In P. Baltes & M. Baltes (Eds.), Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences (pp. 1–34). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baron, M., Fletcher, C., & Riva, M. (2020). Aging, health and place from the perspective of elders in an Inuit community. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 35 , 133–153.

Bauger, L., & Bongaardt, R. (2016). The lived experience of well-being in retirement: A phenomenological study. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 11 , 33110.

Bousquet, J., Kuh, D., Bewick, M., Standberg, T., Farrell, J., Pengelly, R., Joel, M. E., Rodriguez Mañas, L., Mercier, J., Bringer, J., Camuzat, T., Bourret, R., Bedbrook, A., Kowalski, M. L., Samolinski, B., Bonini, S., Brayne, C., Michel, J. P., Venne, J., Viriot-Durandal, P., Alonso, J., Avignon, A., Ben-Shlomo, Y., Bousquet, P. J., Combe, B., Cooper, R., Hardy, R., Iaccarino, G., Keil, T., Kesse-Guyot, E., Momas, I., Ritchie, K., Robine, J. M., Thijs, C., Tischer, C., Vellas, B., Zaidi, A., Alonso, F., Andersen Ranberg, K., Andreeva, V., Ankri, J., Arnavielhe, S., Arshad, H., Augé, P., Berr, C., Bertone, P., Blain, H., Blasimme, A., Buijs, G. J., Caimmi, D., Carriazo, A., Cesario, A., Coletta, J., Cosco, T., Criton, M., Cuisinier, F., Demoly, P., Fernandez-Nocelo, S., Fougère, B., Garcia-Aymerich, J., Goldberg, M., Guldemond, N., Gutter, Z., Harman, D., Hendry, A., Heve, D., Illario, M., Jeandel, C., Krauss-Etschmann, S., Krys, O., Kula, D., Laune, D., Lehmann, S., Maier, D., Malva, J., Matignon, P., Melen, E., Mercier, G., Moda, G., Nizinkska, A., Nogues, M., O'Neill, M., Pelissier, J. Y., Poethig, D., Porta, D., Postma, D., Puisieux, F., Richards, M., Robalo-Cordeiro, C., Romano, V., Roubille, F., Schulz, H., Scott, A., Senesse, P., Slagter, S., Smit, H. A., Somekh, D., Stafford, M., Suanzes, J., Todo-Bom, A., Touchon, J., Traver-Salcedo, V., Van Beurden, M., Varraso, R., Vergara, I., Villalba-Mora, E., Wilson, N., Wouters, E., & Zins, M. (2015). Operational definition of active and healthy ageing (AHA): A conceptual framework. Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 19 , 955–960.

Carpentieri, J. D., Elliott, J., Brett, C. E., & Deary, I. J. (2017). Adapting to aging: Older people talk about their use of selection, optimization, and compensation to maximize well-being in the context of physical decline. Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72 , 351–361.

Carr, K., & Weir, P. L. (2017). A qualitative description of successful aging through different decades of older adulthood. Aging & Mental Health, 21 , 1317–1325.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). The public health system & the 10 essential public health services, https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/publichealthservices/essentialhealthservices.html .

Chen, S.-N., Riner, M. E., Stocker, J. F., & Hsu, M.-T. (2019). Uses and perspectives of aging well terminology in Taiwanese and international literature: A systematic review. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 30 , 64–74.

Conkova, N., & Lindenberg, J. (2020). The experience of aging and perceptions of “aging well” among older migrants in the Netherlands. The Gerontologist, 60 , 270–278.

Cosco, T. D., Prina, A. M., Perales, J., Stephan, B. C. M., & Brayne, C. (2013). Lay perspectives of successful ageing: A systematic review and meta-ethnography. BMJ Open, 3 , e002710.

Cosco, T. D., Stephan, B. C., & Brayne, C. (2015). Validation of an a priori, index model of successful aging in a population-based cohort study: The successful aging index. International Psychogeriatrics, 27 , 1971–1977.

Emlet, C. A., Harris, L., Furlotte, C., Brennan, D. J., & Pierpaoli, C. M. (2017). ‘I’m happy in my life now. I’m a positive person’: Approaches to successful ageing in older adults living with HIV in Ontario, Canada, Ageing & Society, 37 , 2128–2151.

Fazeli, P. L., Montoya, J. L., McDavid, C. N., & Moore, D. J. (2020). Older HIV+ and HIV- adults provide similar definitions of successful aging: A mixed-methods examination. The Gerontologist, 60 , 385–395.

Feng, Q., & Straughan, P. T. (2017). What does successful aging mean? Lay perception of successful aging among elderly Singaporeans, Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72 , 204–213.

Griffith, D. M., Cornish, E. K., Bergner, E. M., Bruce, M. A., & Beech, B. M. (2018). “Health is the ability to manage yourself without help”: How older African American men define health and successful aging. Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73 , 240–247.

Havighurst, R. J. (1961). Successful aging. The Gerontologist, 1 , 8–13.

Hilton, J. M., Gonzalez, C. A., Saleh, M., Maitoza, R., & Anngela-Cole, L. (2012). Perceptions of successful aging among older Latinos, in cross-cultural context. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 27 , 183–199.

Hörder, H. M., Frändin, K., & Larsson, M. E. (2013). Self-respect through ability to keep fear of frailty at a distance: Successful ageing from perspective of community-dwelling older people. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 8 , 20194.

Howell, B. M., & Peterson, J. R. (2020). With age comes wisdom. A qualitative review of elder perspectives on healthy aging in the circumpolar north. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 35 , 113–131.

Hwang, Y. I., Foley, K.-R., & Troller, J. N. (2017). Aging well on the autism spectrum: The perspectives of autistic adults and carers. International Psychogeriatrics, 29 , 2033–2046.

Iwamasa, G. Y., & Iwasaki, M. (2011). A new multidimensional model of successful aging: Perceptions of Japanese American older adults. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 26 , 261–278.

Jopp, D. S., Wozniak, D., Damarin, A. K., De Feo, M., Jung, S., & Jeswani, S. (2015). How could lay perspectives on successful aging complement scientific theory? Findings from a U.S. and a German life-span sample. Gerontologist, 55 , 91–106.

Katz, S., & Calasanti, T. (2015). Critical perspectives on successful aging: Does it “appeal more than it illuminates”? The Gerontologist, 55 , 26–33.

Lagacé, M., Charmarkeh, H., & Grandena, F. (2012). Cultural perceptions of aging: The perspective of Somali Canadians in Ottawa. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 27 , 409–424.

Lamb, S. (2014). Permanent personhood or meaningful decline? Toward a critical anthropology of successful aging, Journal of Aging Studies, 29 , 41–52.

Lamb, S., Robbins-Ruszkowski, J., & Corwin, A. I. (2017). Introduction: Successful aging as a twenty-first-century obsession. In S. Lamb (Ed.), Successful aging as a contemporary obsession: Global perspectives (pp. 1–23). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Lewis, J. P. (2011). Successful aging through the eyes of Alaska native elders. What it means to be an elder in Bristol Bay, AK, Gerontologist, 51 , 540–549.

Lood, Q., Häggblom-Kronlöf, G., & Dellenborg, L. (2016). Embraced by the past, hopeful for the future: Meaning of health to ageing persons who have migrated from the Western Balkan region to Sweden. Ageing & Society, 36 , 649–665.

Martinson, M., & Berridge, C. (2015). Successful aging and its discontents: A systematic review of the social gerontology literature. The Gerontologist, 55 , 58–69.

Nosraty, L., Jylhä, M., Raittila, T., & Lumme-Sandt, K. (2015). Perceptions by the oldest old of successful aging, vitality 90+ study. Journal of Aging Studies, 32 , 50–58.

Reichstadt, J., Sengupta, G., Depp, C. A., Palinkas, L. A., & Jeste, D. V. (2010). Older adults’ perspectives on successful aging: Qualitative interviews. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18 , 567–575.

Reyes-Uribe, A. C. (2015). Perceptions of successful aging among Mexican older adults. Journal of Behavior, Health & Social Issues, 7 , 9–17.

Róin, A. (2014). Embodied ageing and categorisation work amongst retirees in the Faroe Islands. Journal of Aging Studies, 31 , 83–92.

Romo, R. D., Wallhagen, M. I., Yourman, L., Yeung, C. C., Eng, C., Micco, G., Pérez-Stable, E. J., & Smith, A. K. (2012). Perceptions of successful aging among diverse elders with late-life disability. Gerontologist, 53 , 939–949.

Rowe, J. W., & Kahn, R. L. (1987). Human aging: Usual and successful. Science, 237 , 143–149.

Rowe, J. W., & Kahn, R. L. (1997). Successful aging. Gerontologist, 37 , 433–440.

Rowe, J. W., & Kahn, R. L. (2015). Successful aging 2.0: Conceptual expansions for the 21st century. Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70 , 593–596.

Sato-Komata, M., Hoshino, A., Usui, K., & Katsura, T. (2015). Concept of successful ageing among the community-dwelling oldest old in Japan. British Journal of Community Nursing, 20 , 586–592.

Scelzo, A., Di Somma, S., Antonini, P., Montross, L. P., Schork, N., Brenner, D., & Jeste, D. V. (2018). Mixed-methods quantitative-qualitative study of 29 nonagenarians and centenarians in rural southern Italy: Focus on positive psychological traits. International Psychogeriatrics, 30 , 31–38.

Stephens, C., Breheny, M., & Mansvelt, J. (2015). Healthy ageing from the perspective of older people: A capability approach to resilience. Psychology and Health, 30 , 715–731.

Thanakwang, K., Soonthorndhada, K., & Mongkolprasoet, J. (2012). Perspectives on healthy aging among Thai elderly: A qualitative study. Nursing and Health Sciences, 14 , 472–479.

Tkatch, R., Musich, S., Macleod, S., Kraemer, S., Hawkins, K., Wicker, E. R., & Armstrong, D. G. (2017). A qualitative study to examine older adults’ perceptions of health: Keys to aging successfully. Geriatric Nursing, 38 , 485–490.

Todorova, I. L. G., Guzzardo, M. R., Adams, W. E., & Falcón, L. M. (2015). Gratitude and longing: Meanings of health in aging for Puerto Rican adults in the mainland. Journal of Health Psychology, 20 , 1602–1612.

Troutman, M., Nies, M. A., & Mavellia, H. (2011). Perceptions of successful aging in Black older adults. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 49 , 28–34.

World Health Organization. (2015). World report on ageing and health . Geneva: Switzerland.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Gerontology Program, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, USA

Afton J. Reich, Kelsie D. Claunch, Shellie Anderson, Colter K. Clayton & Evan L. Thacker

Department of Public Health, Brigham Young University, 2051 LSB, Provo, UT, USA

Afton J. Reich, Marco A. Verdeja, Matthew T. Dungan & Evan L. Thacker

Department of Exercise Sciences, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, USA

Kelsie D. Claunch

School of Nursing, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, USA

Shellie Anderson

Department of Psychology, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, USA

Colter K. Clayton

Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, USA

Michael C. Goates

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Evan L. Thacker .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Reich, A.J., Claunch, K.D., Verdeja, M.A. et al. What Does “Successful Aging” Mean to you? — Systematic Review and Cross-Cultural Comparison of Lay Perspectives of Older Adults in 13 Countries, 2010–2020. J Cross Cult Gerontol 35 , 455–478 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-020-09416-6

Download citation

Accepted : 08 October 2020

Published : 16 October 2020

Issue Date : December 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-020-09416-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- International

- Lay perspectives

- Older adults

- Successful aging

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Get New Issue Alerts

- American Academy of Arts and Sciences

Successful Aging of Societies

As America ages, policy-makers’ preoccupations with the future costs of Medicare and Social Security grow. But neglected by this focus are critically important and broader societal issues such as intergenerational relations within society and the family, rising inequality and lack of opportunity, productivity in late life (work or volunteering), and human capital development (lifelong education and skills training). Equally important, there is almost no acknowledgment of the substantial benefits and potential of an aging society. The MacArthur Foundation Research Network on an Aging Society offers policy options to address these issues and enhance the transition to a cohesive, productive, secure, and equitable aging society. Such a society will not only function effectively at the societal level but will provide a context that facilitates the capacity of individuals to age successfully. This volume comprises a set of papers, many of which are authored by members of the MacArthur Network, focusing on various aspects of the opportunities and challenges facing the United States while it passes through its current demographic transformation. This essay provides a general overview of the strategy the Network has used to address the various components of this broad subject.

John W. Rowe, a Fellow of the American Academy since 2005, is Professor at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and Chair of the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on an Aging Society. He is the author of Successful Aging (with Robert L. Kahn, 1998) and was the Chair of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies project the Future Health Care Workforce for Older Americans, which authored the report Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce (2008).

Policy-makers and pundits are increasingly preoccupied with the negative economic effects of population aging on public health and pension entitlements, including Medicare and Social Security. The enormous unfunded future obligations of these programs, especially Medicare, tend to crowd out all other considerations. While these entitlement programs surely require modifications to ensure their sustainability and fairness, the current debate neglects other critically important issues related to the aging of America: future intergenerational relations and tensions; socioeconomic disparities and inequalities; changes in the structure and function of the family and its capacity to serve the traditional safety-net role; the impact of technology; and the critical importance of adaptation of core societal institutions, including education, work and retirement, housing, transportation, and even the design of the built environment (the supporting residential, recreational, commercial, and transportation infrastructure). Equally important, there is almost no acknowledgment of the substantial positive contributions and potential productivity of an aging society.

Our goal is to develop and help implement policies that assure our transition to a cohesive, productive, secure, and equitable aging society. Failure to reach this goal will leave us with a society rife with intergenerational tensions – characterized by enormous gaps between the haves and the (increasingly less-educated) have-nots in quality of life and opportunity – and unable to provide needed goods and services for any of its members, especially a progressively older and more dependent population.

Gloomy though this scenario is, it is avoidable. We have time to put in place policies that will help strengthen the future workforce, increase productive engagement of older individuals, and enhance the capacity of families to support elders. Many such policies may, at the same time, lessen the burden on Social Security.

How did we get here? Given the advance warning decades ago that an age wave was coming, why has U.S. society been unable to prepare? Part of the failure to act lies with a set of archaic beliefs regarding the true nature of societal aging. Stakeholders failed to realistically assess challenges and envision opportunities and squandered the time available to formulate appropriate public policy. The denial continues: a recent Pew Research Center survey of global attitudes on aging shows that less than 26 percent of Americans feel that an aging society is a “major issue”! Only Indonesia and Egypt ranked lower on the survey. 1 Contributing to this denial are two pervasive and disabling myths about aging in the United States: the first myth concerns the impact of the baby boom; the second assumes that an aging society is only concerned with the elderly.

The influence of the baby boom on U.S. population aging is not temporary. Contrary to what the popular myth suggests, the passing of the baby boomers through the age structure will not terminate population aging or return us to the age structure of earlier periods of U.S. history. Rather, the demographic changes that have taken place over the last century are permanent. The age structure of all current and future populations either have already been transformed or are about to permanently shift, aggravated in part by the unusually large post – World War II birth cohort, but driven primarily by the combined effect of unprecedented increases in life expectancy and decreases in birth rates.

The second widely accepted myth is that an aging society is defined by and is solely concerned with its elders. This belief tends to pit generations against each other, overlooking the critical fact that the proper unit of analysis for policy-makers is not one specific age cohort but rather society as a whole. Policy-makers must consider the intergenerational effects of their policies and design solutions that benefit all of society, not just any one interest group.

Whereas countries in Western Europe aged ahead of the United States – reflecting their post – World War II baby bust and sustained reductions in total fertility below the replacement rate – the U.S. baby boom and higher fertility rate have combined to delay by a few decades the emergence of an aging society (defined here as one with more individuals over age sixty-five than are under age fifteen). For instance, the United States will not meet Germany’s current population age distribution until 2030. And Germany’s age structure has not caused ruin for its society or its economy. Thus, one would think that the experiences of the Western European countries, which are like the United States in many ways, would provide a clear road map for the policies the United States needs to adopt for a successful transition to a productive and equitable aging society. But although the United States certainly has much to learn from looking at the experiences of older societies in Europe and even of Japan, differences across societies, cultures, and policy strategies may limit the utility of these comparisons, thus requiring the development of a uniquely American resolution to the issues presented by an aging society. In short, international comparisons can be valuable, but we must be cautious in generalizing experiences from other cultures.

The MacArthur Network has developed a set of closely related components that form the core of a theory of adaptation in an aging society. Although there is substantial overlap between these components, identifying each has value. To begin, a plan of action must first:

1) Analyze society and its institutions. The unit of analysis should be the society and the adaptation of its core institutions (such as family, work and retirement, education, media, religion, and civic affairs) and should encompass a multigenerational and intergenerational perspective, rather than focus solely on individuals of any one age group (elders or youth).

2) Take a long-term view and consider structural lag. The primary focus should be on adjusting and adapting core institutions – including education, work and retirement, health care, the design and function of housing and cities, and transportation – over the long term. It is important to keep in mind gerontologist Matilda Riley’s concept of structural lag: the recognition that most societal institutions are resistant to change and lag behind the shifting population of their members. 2

3) Adopt a life-course perspective. U.S. society needs to adopt a life-course perspective that urges redistribution of life’s activities (such as education, work, retirement, childrearing, and leisure) across the individual life span. Stakeholders need to detail the impact of socioeconomic, racial/ ethnic, and gender differences on life-course trajectories and specify how they influence the effectiveness of various lifestyle related interventions.

4) Consider benefits and risks. Analysis of policy changes should consider both the possible benefits and risks to an aging society and should develop a unifying strategy that optimizes the balance between the two. As societies attempt to deal with the many challenges derived from demographic transition, too little attention is paid to its potential upside: the longevity dividend. This includes the previously unimaginable capability of older individuals to participate productively in society either through the workforce or through civic engagement. Older people have much to offer, including accrued knowledge, stability, unique creative capacities for synthetic problem solving, and increased ability to manage conflicts and consider the perspectives of other age groups. As a society, the United States should harness the life-stage-appropriate capabilities and goals of people of all ages, including older adults, to enhance societal benefits and reduce social stratification.

5) Focus on human capital. Policy-makers should focus on strategies that take advantage of all available talent in the population, employ social norms based on ability rather than chronological age, and transition from an emphasis on investment early in life to recognition that investments across the full life span can pay dividends. These payoffs will be individual, intergenerational, and societal (with both crossover and spillover effects); and because they can be positive or negative, the outcomes must be monitored.

The MacArthur Network has developed three strategies for policy analysis. First, it is critical to develop a toolbox of more sensitive and predictive economic and social indicators – including lifestyle dimensions – that permit accurate assessment of the current conditions and likely future trajectory of the population and society along the principal policy dimensions of interest. We need an alternative to the archaic old-age dependency ratio, which simply equates old age with dependency. Metrics that express the full array of benefits-to-costs relationships of a long-lived society, as well as alternatives for life-course trajectories, are also essential. This toolbox can be used to model possible outcomes of societal investment in factors that alter the impact of an aging population. Second, in order to encourage the identification of effective solutions, researchers and policy-makers must present and analyze multiple policy options, rather than advocate single proposals, and should target multiple factors (such as the financial, social, life-course evolution, behavioral, and physical). Further, policy-makers should consider and employ both private and public involvement and federal and local approaches.

Finally, policy analysis must assess policy impacts. The MacArthur Network suggests adopting a strategy similar to that used to assess the environmental impact of a planned development. Specifically, Network members propose that all policies be evaluated for the effects they have within each generation, as well as on the interactions between generations (known as assessing intergenerational effects), in order to be most effective.

In addition, the MacArthur Network has identified six high-priority domains for policy analysis. They include:

1) Intergenerational relations. This general area requires understanding at both the societal and individual family-unit levels. For society, the core question relates to cohesion. What is the potential for the widening gap between the haves and have-nots and for the increased competition over scarce resources being channeled into entitlements to tear at the fabric of our society and create a “war” between the generations?

The MacArthur Network prefers to use the term cohesion to describe the issues related to intergenerational relations (or tensions) because it focuses on age integration rather than age segregation and addresses intergenerational transfers, attitudes, multigenerational strategies, and changes in family structure. Cohesion can be viewed as the debate regarding the traditional social compact – which we prefer over the more commonly used legalistic “contract” – between the generations.

Substantial empirical evidence shows strong support by middle-aged and younger Americans for older Americans and highlights social cohesion’s benefits; but, as many observers have noted, the future increase of entitlement costs may place substantial stress on this balance. 3 Depending on future economic and educational gaps, will future young-adult and middle-aged Hispanics, for example, reflect the same support for elderly white Americans? Further, what impact will future immigration policies, whose intent may be to eliminate the shortfall of skilled U.S. workers, have on these tensions?

2) Family (evolution, supports, changing roles). Families make up the front line of our adaptation to an aging society. For the family, the core question of the aging society relates to the uncertainty regarding its capacity to play its traditional role as safety net and exhibit adaptive capacities to respond to a variety of financial, social, and health-related needs. Factors threatening the family’s role include the emergence of an array of family forms with different capacities for support (such as a childless family unit), increased longevity, geographic dispersion, economic challenges, and likely future reductions in entitlements.

Moreover, these changes are amplified by the growing diversity that results from increased stratification. The strength and salience of intergenerational ties become more prominent features in an aging society, and the traditional life course is being altered in part because of increased longevity. The transition to adulthood comes five or more years later than it used to, placing parents of young adults in the challenging position of helping support their parents or even their grandparents while launching their own children toward independence. 4 Families with resources can manage this balancing act relatively well, but a growing number of families will be overly burdened trying to contend with these competing demands without proven ways of managing the more complex, intergenerational family systems. Issues such as intrafamilial supports, housing, financial transfers, caregiving, and new familial roles will also inform critical policy decisions surrounding the changing face of U.S. families.

3) Productivity (work and retirement, functional status and disability, technology, roles of older individuals in society). The future roles of older individuals in society will have a dramatic impact on the likelihood that the United States will be productive, cohesive, and equitable. This set of issues can be conveniently divided between work and retirement matters and civic engagement matters, although they are closely interrelated. The likelihood of a retiree volunteering is very much influenced by whether that person volunteered while still in the workforce. 5 Thus, approaches to encouraging people to volunteer while still in the workforce – via modifications in time and place of work, provision of opportunities for engaging in what individuals consider meaningful activities, and development of paid volunteerism strategies – may have a substantial positive effect on post-retirement engagement. Such engagement is beneficial not only for retirees but also for the general population.

Technology bridges the worksite to areas of civic engagement and, depending on the type of technology and its fit with the abilities and needs of older individuals, can wind up either facilitating or inhibiting their participation. Substantial opportunity exists for policy changes and technological and other worksite modifications and educational interventions that will not only make retention of older workers more attractive to employers, but will also take advantage of the many strengths older workers offer. It is important for policy-makers to be aware of the “lump-of-labor” fallacy and the growing body of empirical evidence indicating that older individuals need not be moved out of the workforce to make room for younger workers. 6 In addition, policy should be informed by the most recent findings regarding trends in disability in populations of elders and near-elders. Much of the most recent work suggests that the severe disability rates (as measured by activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living scales) are now stable in older individuals, having halted their decades-long decline; and that, for unknown reasons, functional mobility impairments may be rising in individuals aged fifty to sixty-five. 7 It will be important for policy-makers to understand the likely influence of these trends on the adequacy of the future U.S. labor force, as well as on the future demand for personal care services.

4) Human capital development (such as lifelong education and skills training). Some of the same societal forces that led to longer lives have also shortened the half-life of knowledge in science and technology. How can human capital be expanded at different points along the life course? Can the misalignment between education and work that is aggravated by increasing longevity be improved through a closer relationship between educational institutions and the workplace?

Stakeholders need to understand and employ the most effective approaches to keep young individuals in school and to provide a coherent approach to lifelong learning that gives individuals the skills and attitudes they need to continue to productively evolve within overall societal and work environments. Although returning to school – now common among younger adults – is still relatively rare among individuals over forty, providing access to educational institutions for the near-old and old is no less critical than keeping younger people in school. Education must be redefined as a lifelong experience.

5) Health and health care. Although it might seem that the ongoing national debate about health care reform may have exhausted this topic, the Network believes that some important and often neglected areas of the discussion are directly related to the demographic transformation. These include the development of a more geriatrically sophisticated health care system in which most providers (physicians, nurses, dentists, social workers, psychologists, pharmacists, and others) are competent in diagnosing and treating medical diseases and syndromes that are common in old age, as well as a strong reliance on new interdisciplinary models of care that are more effective in managing the health care problems of frail older individuals with multiple impairments. In addition, a reorientation to a life-course preventive health model is needed to strengthen education about healthy lifestyles and intervention implementation in at-risk groups so that future older individuals will enter the Medicare program healthier and at higher levels of functioning than their predecessors. Finally, the United States needs sustainable and clearly articulated policies that deal humanely with care at the end of life.

6) Relevance to successful aging of individuals. Over the past fifteen years, successful aging has been a major theme of gerontological research. Much of the work in the field has been stimulated by the model of successful aging proposed by the MacArthur Network on Successful Aging, which is focused primarily at the level of the individual. 8 It is self-evident that the changes that occur at the societal level in response to the demographic transformation may have major positive or negative effects on the capacity of individuals to age successfully. While many of the issues and policy options discussed in this volume are relevant to individuals, our primary current focus is at the level of society. The interaction between societal change and the status of aging individuals represents fertile territory for future research.