How to Write a Sociological Essay: Explained with Examples

This article will discuss “How to Write a Sociological Essay” with insider pro tips and give you a map that is tried and tested. An essay writing is done in three phases: a) preparing for the essay, b) writing the essay, and c) editing the essay. We will take it step-by-step so that nothing is left behind because the devil, as well as good grades and presentation, lies in the details.

Writing is a skill that we learn throughout the courses of our lives. Learning how to write is a process that we begin as soon as we turn 4, and the learning process never stops. But the question is, “is all writing the same?”. The answer is NO. Do you remember your initial lessons of English when you were in school, and how the teacher taught various formats of writing such as formal, informal, essay, letter, and much more? Therefore, writing is never that simple. Different occasions demand different styles and commands over the writing style. Thus, the art of writing improves with time and experience.

Those who belong to the world of academia know that writing is something that they cannot escape. No writing is the same when it comes to different disciplines of academia. Similarly, the discipline of sociology demands a particular style of formal academic writing. If you’re a new student of sociology, it can be an overwhelming subject, and writing assignments don’t make the course easier. Having some tips handy can surely help you write and articulate your thoughts better.

[Let us take a running example throughout the article so that every point becomes crystal clear. Let us assume that the topic we have with us is to “Explore Culinary Discourse among the Indian Diasporic Communities” .]

Phase I: Preparing for the Essay

Step 1: make an outline.

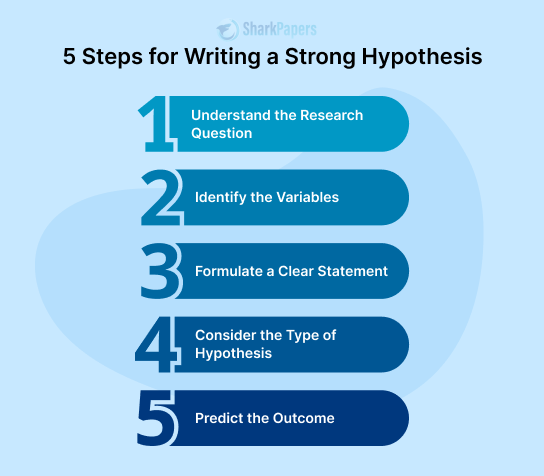

So you have to write a sociological essay, which means that you already either received or have a topic in mind. The first thing for you to do is PLAN how you will attempt to write this essay. To plan, the best way is to make an outline. The topic you have, certainly string some thread in your mind. They can be instances you heard or read, some assumptions you hold, something you studied in the past, or based on your own experience, etc. Make a rough outline where you note down all the themes you would like to talk about in your essay. The easiest way to make an outline is to make bullet points. List all the thoughts and examples that you have in find and create a flow for your essay. Remember that this is only a rough outline so you can always make changes and reshuffle your points.

[Explanation through example, assumed topic: “Explore Culinary Discourse among the Indian Diasporic Communities” . Your outline will look something like this:

- Importance of food

- Definition of Diaspora

- Relationship between food and culture

- Relationship between food and nation

- Relationship between food and media

- Relationship between food and nostalgia

- How food travels with people

- Is food practices different for different sections of society, such as caste, class, gender ]

Step 2: Start Reading

Once you have prepared an outline for your essay, the next step is to start your RESEARCH . You cannot write a sociological essay out of thin air. The essay needs to be thoroughly researched and based on facts. Sociology is the subject of social science that is based on facts and evidence. Therefore, start reading as soon as you have your outline determined. The more you read, the more factual data you will collect. But the question which now emerges is “what to read” . You cannot do a basic Google search to write an academic essay. Your research has to be narrow and concept-based. For writing a sociological essay, make sure that the sources from where you read are academically acclaimed and accepted.

Some of the websites that you can use for academic research are:

- Google Scholar

- Shodhganga

[Explanation through example, assumed topic: “Explore Culinary Discourse among the Indian Diasporic Communities” .

For best search, search for your articles by typing “Food+Diaspora”, “Food+Nostalgia”, adding a plus sign (+) improves the search result.]

Step 3: Make Notes

This is a step that a lot of people miss when they are preparing to write their essays. It is important to read, but how you read is also a very vital part. When you are reading from multiple sources then all that you read becomes a big jumble of information in your mind. It is not possible to remember who said what at all times. Therefore, what you need to do while reading is to maintain an ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY . Whenever you’re reading for writing an academic essay then have a notebook handy, or if you prefer electronic notes then prepare a Word Document, Google Docs, Notes, or any tool of your choice to make notes.

As you begin reading, note down the title of the article, its author, and the year of publication. As you read, keep writing down all the significant points that you find. You can either copy whole sentences or make shorthand notes, whatever suits you best. Once you’ve read the article and made your notes, write a summary of what you just read in 8 to 10 lines. Also, write keywords, these are the words that are most used in the article and reflect its essence. Having keywords and a summary makes it easier for you to revisit the article. A sociological essay needs a good amount of research, which means that you have to read plenty, thus maintaining an annotated bibliography helps you in the greater picture.

Annotate and divide your notes based on the outline you made. Having organized notes will help you directly apply the concepts where they are needed rather than you going and searching for them again.]

Phase II: Write a Sociological Essay

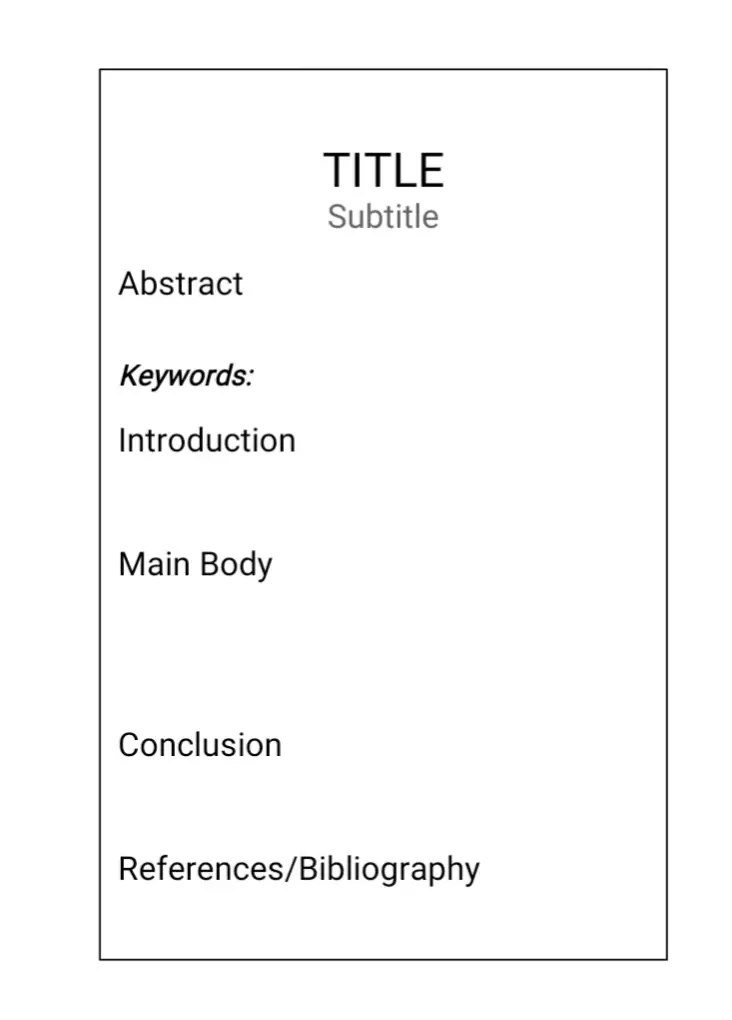

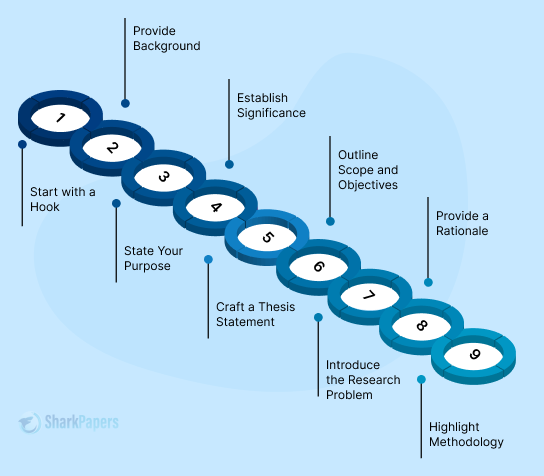

A basic essay includes a title, an introduction, the main body, and a conclusion. A sociological essay is not that different as far as the body of contents goes, but it does include some additional categories. When you write a sociological essay, it should have the following contents and chronology:

- Subtitle (optional)

- Introduction

Conclusion

- References/ Bibliography

Now let us get into the details which go into the writing of a sociological essay.

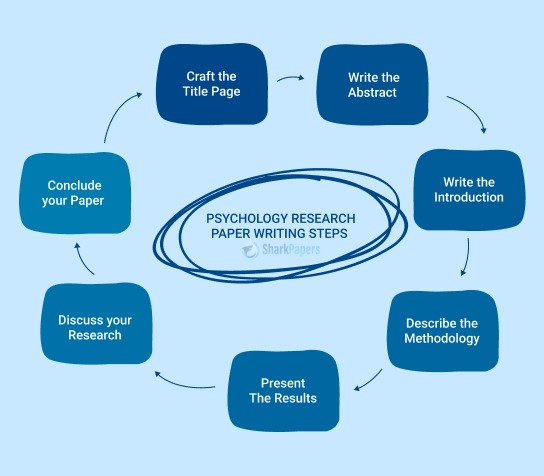

Step 4: Writing a Title, Subtitle, Abstract, and Keywords

The title of any document is the first thing that a reader comes across. Therefore, the title should be provocative, specific, and the most well-thought part of any essay. Your title should reflect what your essay will discuss further. There has to be a sync between the title and the rest of your content. The title should be the biggest font size you use in your essay.

Pro Tip by Sociology Group: A title preferably should not exceed 5 to 7 words.

This is an optional component of any essay. If you think that your title cannot justify the rest of the contents of your essay, then you opt for a subtitle. The subtitle is the secondary part of the title which is used to further elucidate the title. A subtitle should be smaller in font than the Title but bigger than the rest of the essay body.

Pro Tip by Sociology Group: Make the font color of your subtitle Gray instead of Black for it to stand out.

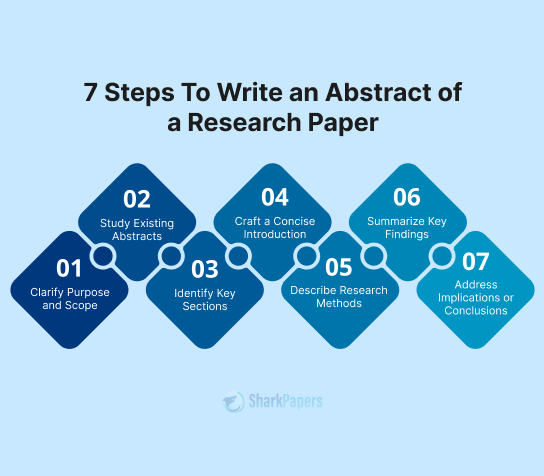

The abstract is a 6 to 10 line description of what you will talk about in your essay. An abstract is a very substantial component of a sociological essay. Most of the essays written in academia exceed the word limit of 2000 words. Therefore, a writer, i.e., you, provides the reader with a short abstract at the beginning of your essay so that they can know what you are going to discuss. From the point of view of the reader, a good abstract can save time and help determine if the piece is worth reading or not. Thus, make sure to make your abstract as reflective to your essay as possible using the least amount of words.

Pro Tip by Sociology Group: If you are not sure about your abstract at first, it is always great to write the abstract in the end after you are done with your essay.

Your abstract should highlight all the points that you will further discuss. Therefore your abstract should mention how diasporic communities are formed and how they are not homogeneous communities. There are differences within this large population. In your essay, you will talk in detail about all the various aspects that affect food and diasporic relationships. ]

Keywords are an extension of your abstract. Whereas in your abstract you will use a paragraph to tell the reader what to expect ahead, by stating keywords, you point out the essence of your essay by using only individual words. These words are mostly concepts of social sciences. At first, glance, looking at your keywords, the reader should get informed about all the concepts and themes you will explain in detail later.

Pro Tip by Sociology Group: Bold your Keywords so that they get highlighted.

Your keywords could be: Food, Diaspora, Migration, and so on. Build on these as you continue to write your essay.]

Step 5: Writing the Introduction, Main Body, and Conclusion

Introduction

Your introduction should talk about the subject on which you are writing at the broadest level. In an introduction, you make your readers aware of what you are going to argue later in the essay. An introduction can discuss a little about the history of the topic, how it was understood till now, and a framework of what you are going to talk about ahead. You can think of your introduction as an extended form of the abstract. Since it is the first portion of your essay, it should paint a picture where the readers know exactly what’s ahead of them.

Pro Tip by Sociology Group: An apt introduction can be covered in 2 to 3 paragraphs (Look at the introduction on this article if you need proof).

Since your focus is on “food” and “diaspora”, your introductory paragraph can dwell into a little history of the relationship between the two and the importance of food in community building.]

This is the most extensive part of any essay. It is also the one that takes up the most number of words. All the research and note-making which you did was for this part. The main body of your essay is where you put all the knowledge you gathered into words. When you are writing the body, your aim should be to make it flow, which means that all paragraphs should have a connection between them. When read in its entirety, the paragraphs should sing together rather than float all around.

The main body is mostly around 4 to 6 paragraphs long. A sociological essay is filled with debates, theories, theorists, and examples. When writing the main body it is best to target making one or two paragraphs about the same revolving theme. When you shift to the other theme, it is best to connect it with the theme you discussed in the paragraph right above it to form a connection between the two. If you are dividing your essay into various sub-themes then the best way to correlate them is starting each new subtheme by reflecting on the last main arguments presented in the theme before it. To make a sociological essay even more enriching, include examples that exemplify the theoretical concepts better.

Pro Tip by Sociology Group: Though there is no word limit to the length of the paragraphs, if you keep one paragraph between 100 to 200 words, it makes the essay look more organized.

The main body can here be divided into the categories which you formed during the first step of making the rough outline. Therefore, your essay could have 3 to 4 sub-sections discussing different themes such as: Food and Media, Caste and Class influence food practices, Politics of Food, Gendered Lens, etc.]

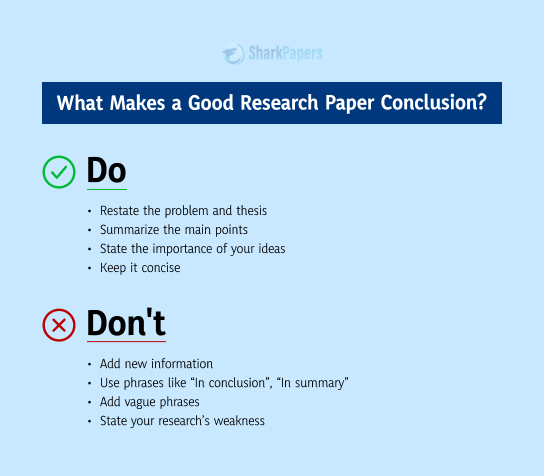

This is the section where you end your essay. But ending the essay does not mean that you lose your flair in conclusion. A conclusion is an essential part of any essay because it sums up everything you just wrote. Your conclusion should be similar to a summary of your essay. You can include shortened versions of the various arguments you have referred to above in the main body, or it can raise questions for further research, and it can also provide solutions if your topic seeks one. Hence, a conclusion is a part where you get the last chance to tell your reader what you are saying through your article.

Pro Tip by Sociology Group: As the introduction, the conclusion is smaller compared to the main body. Keep your conclusion within the range of 1 to 2 paragraphs.

Your conclusion should again reiterate all the main arguments provided by you throughout the essay. Therefore it should bind together everything you have written starting from your introduction to all the debates and examples you have cited.]

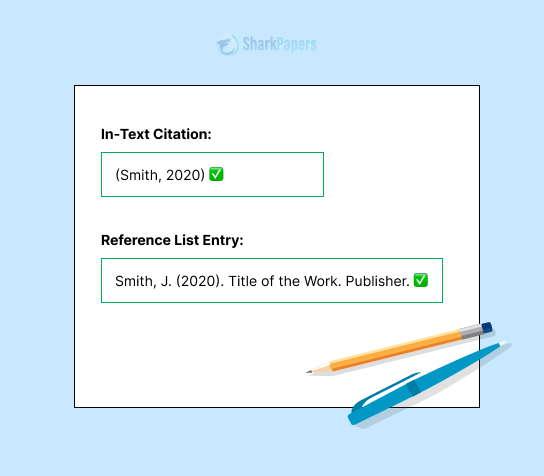

Step 6: Citation and Referencing

This is the most academic part of your sociological essay. Any academic essay should be free of plagiarism. But how can one avoid plagiarism when their essay is based on research which was originally done by others. The solution for this is to give credit to the original author for their work. In the world of academia, this is done through the processes of Citation and Referencing (sometimes also called Bibliography). Citation is done within/in-between the text, where you directly or indirectly quote the original text. Whereas, Referencing or Bibliography is done at the end of an essay where you give resources of the books or articles which you have quoted in your essay at various points. Both these processes are done so that the reader can search beyond your essay to get a better grasp of the topic.

There are many different styles of citations and you can determine which you want to follow. Some of the most common styles of citation and referencing are MLA, APA, and Chicago style. If you are working on Google Docs or Word then the application makes your work easier because they help you curate your citations. There are also various online tools that can make citing references far easier, faster, and adhering to citation guidelines, such as an APA generator. This can save you a lot of time when it comes to referencing, and makes the task far more manageable.

How to add citations in Google Doc: Tools → Citation

How to add citations in Word Document: References → Insert Citations

But for those who want to cite manually, this is the basic format to follow:

- Author’s Name with Surname mentioned first, then initials

- Article’s Title in single or double quotes

- Journal Title in Italics

- Volume, issue number

- Year of Publication

Example: Syrkin, A. 1984. “Notes on the Buddha’s Threats in the Dīgha Nikāya ”, Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies , vol. 7(1), pp.147-58.

Pro Tip by Sociology Group: Always make sure that your Bibliography/References are alphabetically ordered based on the first alphabet of the surname of the author and NOT numbered or bulleted.

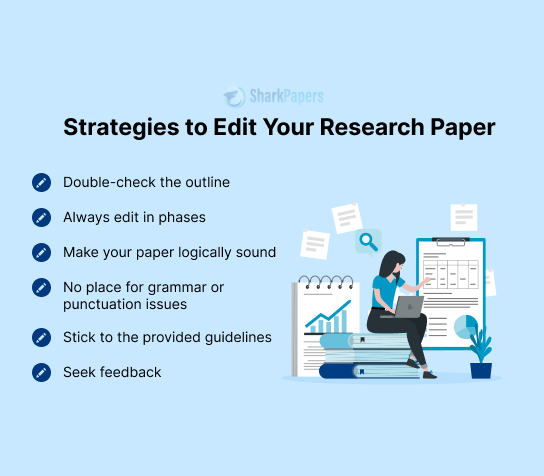

Phase III: Editing

Step 7: edit/review your essay.

The truth of academic writing is that it can never be written in one go. You need to write, rewrite, and revisit your material more than once. Once you have written the first draft of your essay, do not revise it immediately. Leave it for some time, at least for four hours. Then revisit your essay and edit it based on 3 criteria. The first criteria you need to recheck for is any grammatical and/or spelling mistakes. The second criteria are to check the arguments you have posed and if the examples you have cited correlate or not. The final criteria are to read the essay as a reader and read it objectively.

Pro Tip by Sociology Group: The more you edit the better results you get. But we think that your 3rd draft is the magic draft. Draft 1: rough essay, Draft 2: edited essay, Draft 3: final essay.

Hello! Eiti is a budding sociologist whose passion lies in reading, researching, and writing. She thrives on coffee, to-do lists, deadlines, and organization. Eiti's primary interest areas encompass food, gender, and academia.

How To Write A Sociology Research Paper Outline: Easy Guide With Template

Table of contents

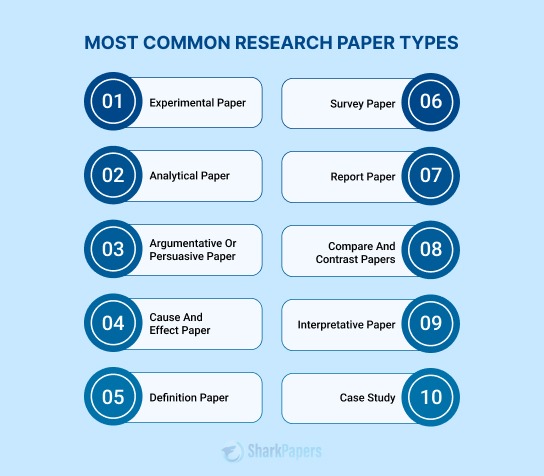

- 1 What Is A Sociology Research Paper?

- 2 Sociology Paper Format

- 3 Structure of the Sociology Paper

- 4 Possible Sociology Paper Topics

- 5.1 Sociology Research Paper Outline Example

- 6 Sociology Research Paper Example

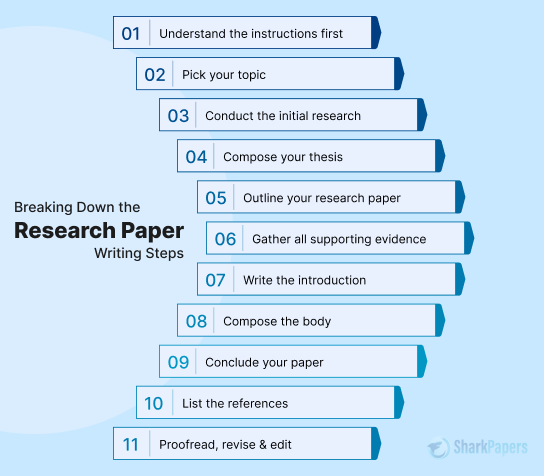

Writing a sociology research paper is mandatory in many universities and school classes, where students must properly present a relevant topic chosen with supporting evidence, exhaustive research, and new ways of understanding or explaining some author’s ideas. This type of paper is very common among political science majors and classes but can be assigned to almost every subject.

Learn about the key elements of a sociological paper and how to write an excellent piece.

Sociology papers require a certain structure and format to introduce the topic and key points of the research according to academic requirements. For those students struggling with this type of assignment, the following article will share some light on how to write a sociology research paper and create a sociology research paper outline, among other crucial points that must be addressed to design and write an outstanding piece.

With useful data about this common research paper, including topic ideas and a detailed outline, this guide will come in handy for all students and writers in need of writing an academic-worthy sociology paper.

What Is A Sociology Research Paper?

A sociology research paper is a specially written composition that showcases the writer’s knowledge on one or more sociology topics. Writing in sociology requires a certain level of knowledge and skills, such as critical thinking and cohesive writing, to be worthy of great academic recognition.

Furthermore, writing sociology papers have to follow a research paper type of structure to ensure the hypothesis and the rest of the ideas introduced in the research can be properly read and understood by teachers, peers, and readers in general.

Sociology research papers are commonly written following the format used in reports and are based on interviews, data, and text analysis. Writing a sociology paper requires students to perform unique research on a relevant topic (including the appropriate bibliography and different sources used such as books, websites, scientific journals, etc.), test a question or hypothesis that the paper will try to prove or deny, compare different sociologist’s points of view and how/why they state certain sayings and data, among other critical points.

A research paper in sociology also needs to apply the topic of current events, at least in some parts of the piece, in which writers must apply the theory to today’s scenarios. In addition to this, sociology research requires students to perform some kind of field research such as interviews, observational and participant research, and others.

Sociology research papers require a deep understanding of the subject and the ability to gather information from multiple sources. Therefore, many students seek help from experienced online essay writers to guide them through the research process and craft a compelling paper. With the help of a professional essay writer, students can craft a comprehensive sociology research paper outline to ensure they cover all the relevant points.

After explaining what this type of paper consists of, it is time to dive into one of the most searched questions online, “What format are sociology papers written in?”. Below you can find a detailed paragraph with all the information necessary.

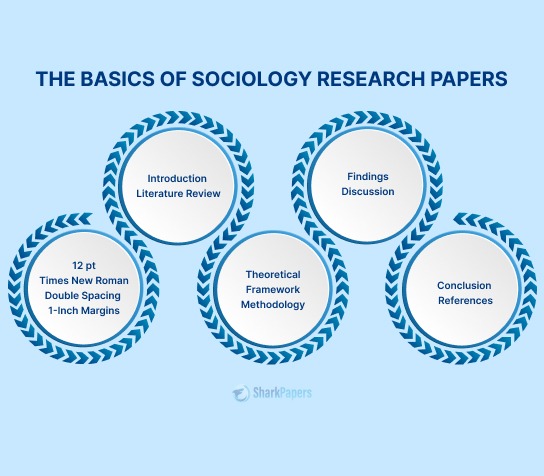

Sociology Paper Format

A sociology paper format follows some standard requirements that can be seen on other types of papers as well. The format commonly used in college and other academic institutions consists of an appropriate citation style, which many professors ask for in the traditional APA format, but others can also require students to write in ASA style (very similar to APA, and the main difference is how you write the author’s name).

The citation is one of the major parts of any sociological research paper that needs to be understood perfectly and used according to the rules established by it. Failing to present a cohesive and correct citing format is very likely to cause the failure of the assignment.

As for the visual part of the paper, a neat and professional font is called for, and generally, the standard sociology paper outline is written in Times New Roman font (12pt and double spaced) with at least 1 inch of margin on both sides. If your professor did not specify which sociology format to use, it is safe to say that this one will be just fine for your delivery.

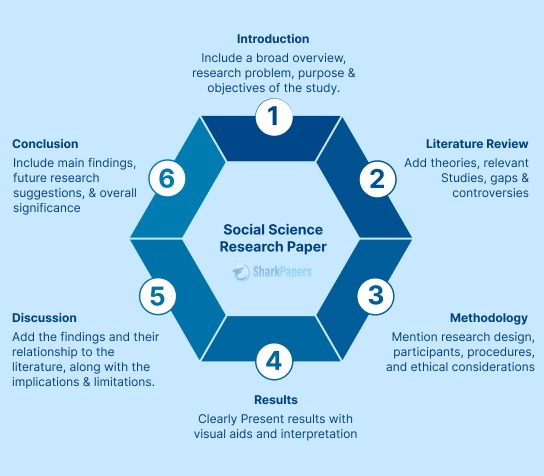

Sociology papers have a specific structure, just like other research pieces, which consist of an introduction , a body with respective paragraphs for each new idea, and a research conclusion . In the point below, you can find a detailed sociology research paper outline to help you write your statement as smoothly and professionally as possible.

Structure of the Sociology Paper

A traditional sociology research paper outline is based on a few key points that help present and develop the information and the writer’s skills properly. Below is a sociology research paper outline to start designing your project according to the standard requirements.

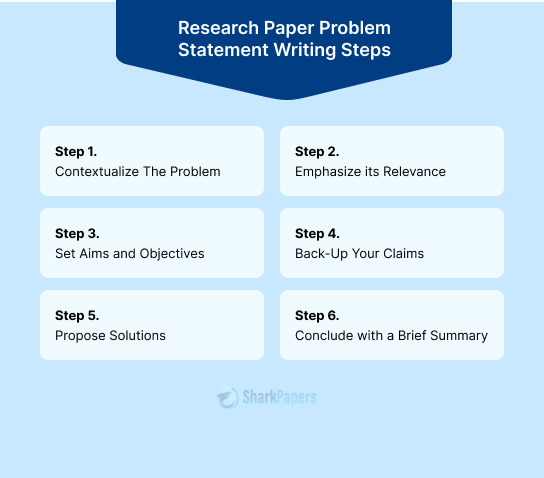

- Introduction. In this first part, you should state the question or problem to be solved during the article. Including a hypothesis and supporting the claim relevant to the chosen field is recommended.

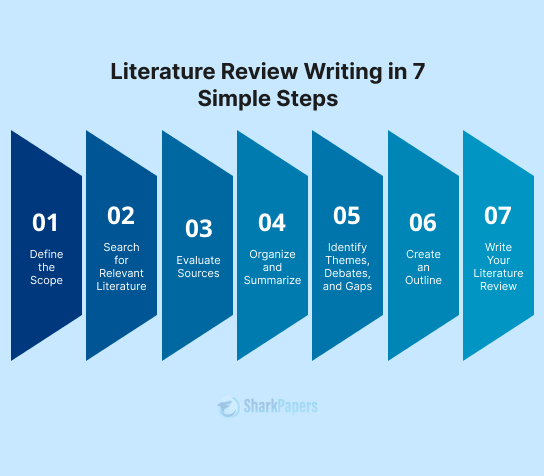

- Literature review. Including the literature review is essential to a sociology research paper outline to present the authors and information used.

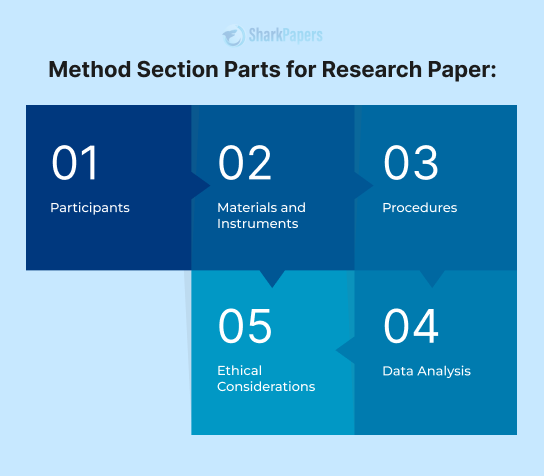

- Methodology. A traditional outline for a sociology research paper includes the methodology used, in which writers should explain how they approach their research and the methods used. It gives credibility to their work and makes it more professional.

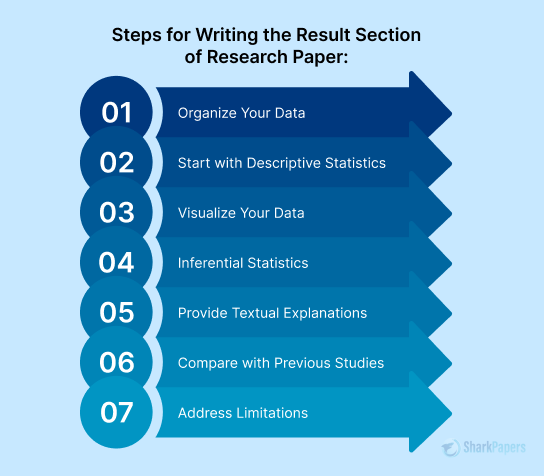

- Outcomes & findings. Sociological research papers must include, after the methodology, the outcomes and findings to provide readers with a glimpse of what your paper resulted in. Graphics and tables are highly encouraged to use on this part.

- Discussion. The discussion part of a sociological paper serves as an overall review of the research, how difficult it was, and what can be improved.

- Conclusion. Finally, to close your sociology research paper outline, briefly mention the results obtained and do the last paragraph with the writer’s final words on the topic.

- Bibliography. The bibliography should be the last page (or pages) included in the article but in different sheets than the paper (this means, if you finished your article in the middle of the page, the bibliography should start on a new separate one), in which sources must be cited according to the style chosen (APA, ASA, etc.).

This sociology research paper outline serves as a great guide for those who want to properly present a sociological piece worthy of academic recognition. Furthermore, to achieve a good grade, it is essential to choose a great topic.

Below you can find some sociology paper topics to help you decide how to begin writing yours.

Possible Sociology Paper Topics

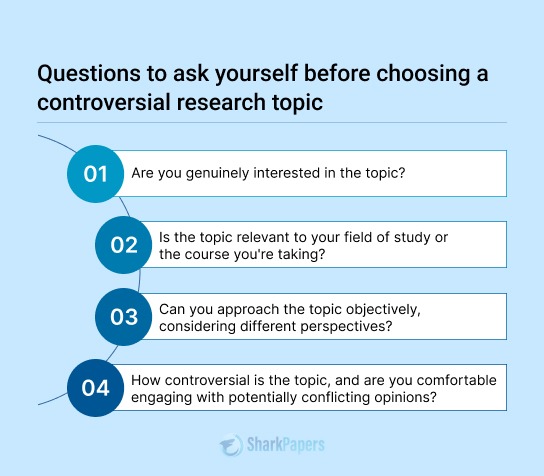

To present a quality piece, choosing a relevant topic inside the sociological field is essential. Here you can find unique sociology research paper topics that will make a great presentation.

- Relationship Between Race and Class

- How Ethnicity Affects Education

- How Women Are Presented By The Media

- Sexuality And Television

- Youth And Technology: A Revision To Social Media

- Technology vs. Food: Who Comes First?

- How The Cinema Encourages Unreachable Standards

- Adolescence And Sex

- How Men And Women Are Treated Different In The Workplace

- Anti-vaccination: A Civil Right Or Violation?

These sociology paper topics will serve as a starting point where students can conduct their own research and find their desired approach. Furthermore, these topics can be studied in various decades, which adds more value and data to the paper.

Writing a Great Sociology Research Paper Outline

If you’re searching for how to write a sociology research paper, this part will come in handy. A good sociology research paper must properly introduce the topic chosen while presenting supporting evidence, the methodology used, and the sources investigated, and to reach this level of academic excellence, the following information will provide a great starting point.

Three main sociology research paper outlines serve similar roles but differ in a few things. The traditional outline utilizes Roman numerals to itemize sections and formats the sub-headings with capital letters, later using Arabic numerals for the next layer. This one is great for those who already have an idea of what they’ll write about.

The second sample is the post-draft outline, where writers mix their innovative ideas and the actual paper’s outline. This second type of draft is ideal for those with a few semi-assembled ideas that need to be developed around the paper’s main idea. Naturally, a student will end up finding their way through the research and structuring the piece smoothly while writing it.

Lastly, the third type of outline is referred to as conceptual outline and serves as a visual representation of the text written. Similar to a conceptual map, this outline used big rectangles that include the key topics or headings of the paper, as well as circles that represent the sources used to support those headings. This one is perfect for those who need to visually see their paper assembled, and it can also be used to see which ideas need further development or supporting evidence.

Furthermore, to write a great sociology paper, the following tips will be of great help.

- Introduction. An eye-catching introduction calls for an unknown or relevant fact that captivates the reader’s attention. Apart from conducting excellent research, students worthy of the highest academic score are those able to present the information properly and in a way that the audience will be interested in reading.

- Body. The paragraphs presented must be written attractively, to make readers want to know more. It is important to explain theories and add supporting evidence to back up your sayings and ideas; empirical data is highly recommended to be added to give the research paper more depth and physical recognition. A great method is to start a paragraph presenting an idea or theory, develop the paragraph with supporting evidence and close it with findings or results. This way, readers can easily understand the idea and comprehend what you want to portray.

- Conclusion. For the conclusion, it is highly important, to sum up the key points presented in the sociology research paper, and after doing so, professors always recommend adding further readings or suggested bibliography to help readers who are interested in continuing their education on the topic just read.

No matter the method you choose to plan out your sociological papers, you’ll need to cover a few bases of how to assemble your final draft. If you’re stuck on where to begin your work, you can always buy sociology research paper from professional writers. Many students go to the pros to shore up their grades and make time when deadlines become overwhelming. If you do it independently, double-check your assignment’s requirements and fit them into the following sections.

Sociology Research Paper Outline Example

The following sociology research paper outline example will serve as an excellent guide and template which students can customize to fit their topics and key points. The outline above follows the topic “How Women Are Presented By The Media”.

Sociology Research Paper Example

PapersOwl website is an excellent resource if you’re looking for more detailed examples of sociology research papers. We provide a wide range of sample research papers that can serve as a guide and template for your own work.

“Changing Demographics Customer Service to Millennials” Example

Students who structure their sociological papers before conducting in-depth research are more likely to succeed. This happens because it is easier and more efficient to research specific key points rather than diving into the topic without knowing how to approach it or presenting the information, data, statistics, and others found.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

ReviseSociology

A level sociology revision – education, families, research methods, crime and deviance and more!

A Level Sociology Essays – How to Write Them

Use the Point – Explain – Expand – Criticise method (PEEC), demonstrate knowledge, application and evaluation skills, and use the item to make your points!

Table of Contents

Last Updated on November 10, 2022 by

This post offers some advice on how you might plan and write essays in the A level sociology exams.

Essays will either be 20 or 30 marks depending on the paper but the general advice for answering them remains the same:

- Use the PEEC method for the main paragraphs: POINT – EXPLAIN – EXPAND – CRITICISE

- Use the overall structure below – PEEC (3 to 5 times) framed by an introduction, then overall evaluations and conclusion towards the end.

- Use the item provided – this must form the basis of your main points!

How to write an A-level sociology essay

- Allow yourself enough time – 1.5 minutes per mark = 45 minutes for a 30 mark essay.

- Read the Question and the item, what is it asking you to do?

- Do a rough plan (5-10 mins) – initially this should be ‘arguments and evidence’ for and ‘against’ the views in the question, and a few thoughts on overall evaluations/ a conclusion. If you are being asked to look at two things, you’ll have to do this twice/ your conclusion should bring the two aspects of the essay together.

- Write the essay (35 mins)– aim to make 3-5 points in total (depending on the essay, either 3 deep points, or 5 (or more) shallower points). Try to make one point at least stem from the item, ideally the first point.

- Try to stick to the following structure in the picture above!

- Overall evaluations – don’t repeat yourself, and don’t overdo this, but it’s useful t tag this in before a conclusion.

- Conclusion (allow 2 mins minimum) – an easy way to do this is to refer to the item – do you agree with the view or not, or say which of the points you’ve made is the strongest/ weakest and on balance is the view in the question sensible or not?

Skills in the A Level Sociology Exam

The AQA wants you to demonstrate 3 sets of skills in the exam – below are a few suggestions about how you can do this in sociology essays.

AO1: Knowledge and Understanding

You can demonstrate these by:

- Using sociological concepts

- Using sociological perspectives

- Using research studies

- Showing knowledge of contemporary trends and news events

- Knowledge can also be synoptic, or be taken from other topics.

- NB – knowledge has to be relevant to the question to get marks!

AO2: Application

You can demonstrate application by…

- Using the item – refer to the item!!!

- Clearly showing how the material you have selected is relevant to the question, by using the words in the question

- Making sure knowledge selected is relevant to the question.

AO3: Analysis and Evaluation

NB ‘Assess’ is basically the same as Evaluation

You can demonstrate analysis by….

- Considering an argument from a range of perspectives – showing how one perspective might interpret the same evidence in a different way, for example.

- Developing points – by showing why perspectives argue what they do, for example.

- Comparing and contrasting ideas to show their differences and similarities

- You can show how points relate to other points in the essay.

You can demonstrate evaluation by…

- Discussing the strengths and limitations of a theory/ perspective or research method.

- You should evaluate each point, but you can also do overall evaluations from other perspectives before your conclusion.

- NB – Most people focus on weaknesses, but you should also focus on strengths.

- Weighing up which points are the most useful in a conclusion.

Use the item

Every 30 mark question will ask you to refer to an ‘item’. This will be a very short piece of writing, consisting of about 8 lines of text. The item will typically refer to one aspect of the knowledge side of the question and one evaluation point. For example, if the question is asking you to ‘assess the Functionalist view of education’, the item is likely to refer to one point Functionalists make about education – such as role allocation, and one criticism.

All you need to do to use the item effectively is to make sure at least one of your points stems from the knowledge in the item, and develop it. It’s a good idea to make this your first point. To use the evaluation point from the item (there is usually some evaluation in there), then simply flag it up when you use it during the essay.

Signposting

For more exams advice please see my exams and essay advice page

To return to the homepage – revisesociology.com

Seven examples of sociology essays, and more advice…

For more information on ‘how to write sociology essays for the A level exam’ why not refer to my handy ‘how to write sociology essays guide’.

The contents are as follows:

Introductory Section

- A quick look at the three sociology exam papers

- A pared-down mark scheme for A Level sociology essays

- Knowledge, application, analysis, evaluation, what are they, how to demonstrate them.

- How to write sociology essays – the basics:

These appear first in template form, then with answers, with the skills employed shown in colour. Answers are ‘overkill’ versions designed to get full marks in the exam.

- Assess the Functionalist View of the Role of Education in Society (30) – Quick plan

- Assess the Marxist view of the role of education in society (30) – Detailed full essay

- Assess the extent to which it is home background that is the main cause of differential education achievement by social class (30) – Detailed full essay

- Assess the view that education policies since 1988 have improved equality of educational opportunity (30) – Quick plan

- Assess the view that the main aim of education policies since 1988 has been to raise overall standards in education.’ (30) – Quick plan

- Assess the claim that ‘ethnic difference in educational achievement are primarily the result of school factors’ (30) – Detailed full essay

- Assess the view that in school processes, rather than external factors, are the most important in explaining differences in educational achievement (30) – detailed essay – Quick plan.

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

One thought on “A Level Sociology Essays – How to Write Them”

- Pingback: Important Tips To Write The Best Sociology Essay – Revise Sociology

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from ReviseSociology

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

What this handout is about

This handout introduces you to the wonderful world of writing sociology. Before you can write a clear and coherent sociology paper, you need a firm understanding of the assumptions and expectations of the discipline. You need to know your audience, the way they view the world and how they order and evaluate information. So, without further ado, let’s figure out just what sociology is, and how one goes about writing it.

What is sociology, and what do sociologists write about?

Unlike many of the other subjects here at UNC, such as history or English, sociology is a new subject for many students. Therefore, it may be helpful to give a quick introduction to what sociologists do. Sociologists are interested in all sorts of topics. For example, some sociologists focus on the family, addressing issues such as marriage, divorce, child-rearing, and domestic abuse, the ways these things are defined in different cultures and times, and their effect on both individuals and institutions. Others examine larger social organizations such as businesses and governments, looking at their structure and hierarchies. Still others focus on social movements and political protest, such as the American civil rights movement. Finally, sociologists may look at divisions and inequality within society, examining phenomena such as race, gender, and class, and their effect on people’s choices and opportunities. As you can see, sociologists study just about everything. Thus, it is not the subject matter that makes a paper sociological, but rather the perspective used in writing it.

So, just what is a sociological perspective? At its most basic, sociology is an attempt to understand and explain the way that individuals and groups interact within a society. How exactly does one approach this goal? C. Wright Mills, in his book The Sociological Imagination (1959), writes that “neither the life of an individual nor the history of a society can be understood without understanding both.” Why? Well, as Karl Marx observes at the beginning of The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852), humans “make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past.” Thus, a good sociological argument needs to balance both individual agency and structural constraints. That is certainly a tall order, but it is the basis of all effective sociological writing. Keep it in mind as you think about your own writing.

Key assumptions and characteristics of sociological writing

What are the most important things to keep in mind as you write in sociology? Pay special attention to the following issues.

The first thing to remember in writing a sociological argument is to be as clear as possible in stating your thesis. Of course, that is true in all papers, but there are a couple of pitfalls common to sociology that you should be aware of and avoid at all cost. As previously defined, sociology is the study of the interaction between individuals and larger social forces. Different traditions within sociology tend to favor one side of the equation over the other, with some focusing on the agency of individual actors and others on structural factors. The danger is that you may go too far in either of these directions and thus lose the complexity of sociological thinking. Although this mistake can manifest itself in any number of ways, three types of flawed arguments are particularly common:

- The “ individual argument ” generally takes this form: “The individual is free to make choices, and any outcomes can be explained exclusively through the study of their ideas and decisions.” While it is of course true that we all make our own choices, we must also keep in mind that, to paraphrase Marx, we make these choices under circumstances given to us by the structures of society. Therefore, it is important to investigate what conditions made these choices possible in the first place, as well as what allows some individuals to successfully act on their choices while others cannot.

- The “ human nature argument ” seeks to explain social behavior through a quasi-biological argument about humans, and often takes a form such as: “Humans are by nature X, therefore it is not surprising that Y.” While sociologists disagree over whether a universal human nature even exists, they all agree that it is not an acceptable basis of explanation. Instead, sociology demands that you question why we call some behavior natural, and to look into the social factors which have constructed this “natural” state.

- The “ society argument ” often arises in response to critiques of the above styles of argumentation, and tends to appear in a form such as: “Society made me do it.” Students often think that this is a good sociological argument, since it uses society as the basis for explanation. However, the problem is that the use of the broad concept “society” masks the real workings of the situation, making it next to impossible to build a strong case. This is an example of reification, which is when we turn processes into things. Society is really a process, made up of ongoing interactions at multiple levels of size and complexity, and to turn it into a monolithic thing is to lose all that complexity. People make decisions and choices. Some groups and individuals benefit, while others do not. Identifying these intermediate levels is the basis of sociological analysis.

Although each of these three arguments seems quite different, they all share one common feature: they assume exactly what they need to be explaining. They are excellent starting points, but lousy conclusions.

Once you have developed a working argument, you will next need to find evidence to support your claim. What counts as evidence in a sociology paper? First and foremost, sociology is an empirical discipline. Empiricism in sociology means basing your conclusions on evidence that is documented and collected with as much rigor as possible. This evidence usually draws upon observed patterns and information from collected cases and experiences, not just from isolated, anecdotal reports. Just because your second cousin was able to climb the ladder from poverty to the executive boardroom does not prove that the American class system is open. You will need more systematic evidence to make your claim convincing. Above all else, remember that your opinion alone is not sufficient support for a sociological argument. Even if you are making a theoretical argument, you must be able to point to documented instances of social phenomena that fit your argument. Logic is necessary for making the argument, but is not sufficient support by itself.

Sociological evidence falls into two main groups:

- Quantitative data are based on surveys, censuses, and statistics. These provide large numbers of data points, which is particularly useful for studying large-scale social processes, such as income inequality, population changes, changes in social attitudes, etc.

- Qualitative data, on the other hand, comes from participant observation, in-depth interviews, data and texts, as well as from the researcher’s own impressions and reactions. Qualitative research gives insight into the way people actively construct and find meaning in their world.

Quantitative data produces a measurement of subjects’ characteristics and behavior, while qualitative research generates information on their meanings and practices. Thus, the methods you choose will reflect the type of evidence most appropriate to the questions you ask. If you wanted to look at the importance of race in an organization, a quantitative study might use information on the percentage of different races in the organization, what positions they hold, as well as survey results on people’s attitudes on race. This would measure the distribution of race and racial beliefs in the organization. A qualitative study would go about this differently, perhaps hanging around the office studying people’s interactions, or doing in-depth interviews with some of the subjects. The qualitative researcher would see how people act out their beliefs, and how these beliefs interact with the beliefs of others as well as the constraints of the organization.

Some sociologists favor qualitative over quantitative data, or vice versa, and it is perfectly reasonable to rely on only one method in your own work. However, since each method has its own strengths and weaknesses, combining methods can be a particularly effective way to bolster your argument. But these distinctions are not just important if you have to collect your own data for your paper. You also need to be aware of them even when you are relying on secondary sources for your research. In order to critically evaluate the research and data you are reading, you should have a good understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of the different methods.

Units of analysis

Given that social life is so complex, you need to have a point of entry into studying this world. In sociological jargon, you need a unit of analysis. The unit of analysis is exactly that: it is the unit that you have chosen to analyze in your study. Again, this is only a question of emphasis and focus, and not of precedence and importance. You will find a variety of units of analysis in sociological writing, ranging from the individual up to groups or organizations. You should choose yours based on the interests and theoretical assumptions driving your research. The unit of analysis will determine much of what will qualify as relevant evidence in your work. Thus you must not only clearly identify that unit, but also consistently use it throughout your paper.

Let’s look at an example to see just how changing the units of analysis will change the face of research. What if you wanted to study globalization? That’s a big topic, so you will need to focus your attention. Where would you start?

You might focus on individual human actors, studying the way that people are affected by the globalizing world. This approach could possibly include a study of Asian sweatshop workers’ experiences, or perhaps how consumers’ decisions shape the overall system.

Or you might choose to focus on social structures or organizations. This approach might involve looking at the decisions being made at the national or international level, such as the free-trade agreements that change the relationships between governments and corporations. Or you might look into the organizational structures of corporations and measure how they are changing under globalization. Another structural approach would be to focus on the social networks linking subjects together. That could lead you to look at how migrants rely on social contacts to make their way to other countries, as well as to help them find work upon their arrival.

Finally, you might want to focus on cultural objects or social artifacts as your unit of analysis. One fine example would be to look at the production of those tennis shoes the kids seem to like so much. You could look at either the material production of the shoe (tracing it from its sweatshop origins to its arrival on the showroom floor of malls across America) or its cultural production (attempting to understand how advertising and celebrities have turned such shoes into necessities and cultural icons).

Whichever unit of analysis you choose, be careful not to commit the dreaded ecological fallacy. An ecological fallacy is when you assume that something that you learned about the group level of analysis also applies to the individuals that make up that group. So, to continue the globalization example, if you were to compare its effects on the poorest 20% and the richest 20% of countries, you would need to be careful not to apply your results to the poorest and richest individuals.

These are just general examples of how sociological study of a single topic can vary. Because you can approach a subject from several different perspectives, it is important to decide early how you plan to focus your analysis and then stick with that perspective throughout your paper. Avoid mixing units of analysis without strong justification. Different units of analysis generally demand different kinds of evidence for building your argument. You can reconcile the varying levels of analysis, but doing so may require a complex, sophisticated theory, no small feat within the confines of a short paper. Check with your instructor if you are concerned about this happening in your paper.

Typical writing assignments in sociology

So how does all of this apply to an actual writing assignment? Undergraduate writing assignments in sociology may take a number of forms, but they typically involve reviewing sociological literature on a subject; applying or testing a particular concept, theory, or perspective; or producing a small-scale research report, which usually involves a synthesis of both the literature review and application.

The critical review

The review involves investigating the research that has been done on a particular topic and then summarizing and evaluating what you have found. The important task in this kind of assignment is to organize your material clearly and synthesize it for your reader. A good review does not just summarize the literature, but looks for patterns and connections in the literature and discusses the strengths and weaknesses of what others have written on your topic. You want to help your reader see how the information you have gathered fits together, what information can be most trusted (and why), what implications you can derive from it, and what further research may need to be done to fill in gaps. Doing so requires considerable thought and organization on your part, as well as thinking of yourself as an expert on the topic. You need to assume that, even though you are new to the material, you can judge the merits of the arguments you have read and offer an informed opinion of which evidence is strongest and why.

Application or testing of a theory or concept

The application assignment asks you to apply a concept or theoretical perspective to a specific example. In other words, it tests your practical understanding of theories and ideas by asking you to explain how well they apply to actual social phenomena. In order to successfully apply a theory to a new case, you must include the following steps:

- First you need to have a very clear understanding of the theory itself: not only what the theorist argues, but also why they argue that point, and how they justify it. That is, you have to understand how the world works according to this theory and how one thing leads to another.

- Next you should choose an appropriate case study. This is a crucial step, one that can make or break your paper. If you choose a case that is too similar to the one used in constructing the theory in the first place, then your paper will be uninteresting as an application, since it will not give you the opportunity to show off your theoretical brilliance. On the other hand, do not choose a case that is so far out in left field that the applicability is only superficial and trivial. In some ways theory application is like making an analogy. The last thing you want is a weak analogy, or one that is so obvious that it does not give any added insight. Instead, you will want to choose a happy medium, one that is not obvious but that allows you to give a developed analysis of the case using the theory you chose.

- This leads to the last point, which is the analysis. A strong analysis will go beyond the surface and explore the processes at work, both in the theory and in the case you have chosen. Just like making an analogy, you are arguing that these two things (the theory and the example) are similar. Be specific and detailed in telling the reader how they are similar. In the course of looking for similarities, however, you are likely to find points at which the theory does not seem to be a good fit. Do not sweep this discovery under the rug, since the differences can be just as important as the similarities, supplying insight into both the applicability of the theory and the uniqueness of the case you are using.

You may also be asked to test a theory. Whereas the application paper assumes that the theory you are using is true, the testing paper does not makes this assumption, but rather asks you to try out the theory to determine whether it works. Here you need to think about what initial conditions inform the theory and what sort of hypothesis or prediction the theory would make based on those conditions. This is another way of saying that you need to determine which cases the theory could be applied to (see above) and what sort of evidence would be needed to either confirm or disconfirm the theory’s hypothesis. In many ways, this is similar to the application paper, with added emphasis on the veracity of the theory being used.

The research paper

Finally, we reach the mighty research paper. Although the thought of doing a research paper can be intimidating, it is actually little more than the combination of many of the parts of the papers we have already discussed. You will begin with a critical review of the literature and use this review as a basis for forming your research question. The question will often take the form of an application (“These ideas will help us to explain Z.”) or of hypothesis testing (“If these ideas are correct, we should find X when we investigate Y.”). The skills you have already used in writing the other types of papers will help you immensely as you write your research papers.

And so we reach the end of this all-too-brief glimpse into the world of sociological writing. Sociologists can be an idiosyncratic bunch, so paper guidelines and expectations will no doubt vary from class to class, from instructor to instructor. However, these basic guidelines will help you get started.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Cuba, Lee. 2002. A Short Guide to Writing About Social Science , 4th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Rosen, Leonard J., and Laurence Behrens. 2003. The Allyn & Bacon Handbook , 5th ed. New York: Longman.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

1.1 What Is Sociology?

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Explain concepts central to sociology.

- Describe how different sociological perspectives have developed.

What Are Society and Culture?

Sociology is the scientific and systematic study of groups and group interactions, societies and social interactions, from small and personal groups to very large groups. A group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture is what sociologists call a society .

Sociologists study all aspects and levels of society. Sociologists working from the micro-level study small groups and individual interactions, while those using macro-level analysis look at trends among and between large groups and societies. For example, a micro-level study might look at the accepted rules of conversation in various groups such as among teenagers or business professionals. In contrast, a macro-level analysis might research the ways that language use has changed over time or in social media outlets.

The term culture refers to the group’s shared practices, values, and beliefs. Culture encompasses a group’s way of life, from routine, everyday interactions to the most important parts of group members’ lives. It includes everything produced by a society, including all the social rules.

Sociologists often study culture using the sociological imagination , which pioneer sociologist C. Wright Mills described as an awareness of the relationship between a person’s behavior and experience and the wider culture that shaped the person’s choices and perceptions. It’s a way of seeing our own and other people’s behavior in relationship to history and social structure (1959). One illustration of this is a person’s decision to marry. In the United States, this choice is heavily influenced by individual feelings. However, the social acceptability of marriage relative to the person’s circumstances also plays a part.

Remember, though, that culture is a product of the people in a society. Sociologists take care not to treat the concept of “culture” as though it were alive and real. The error of treating an abstract concept as though it has a real, material existence is known as reification (Sahn, 2013).

Studying Patterns: How Sociologists View Society

All sociologists are interested in the experiences of individuals and how those experiences are shaped by interactions with social groups and society. To a sociologist, the personal decisions an individual makes do not exist in a vacuum. Cultural patterns , social forces and influences put pressure on people to select one choice over another. Sociologists try to identify these general patterns by examining the behavior of large groups of people living in the same society and experiencing the same societal pressures.

Consider the changes in U.S. families. The “typical” family in past decades consisted of married parents living in a home with their unmarried children. Today, the percent of unmarried couples, same-sex couples, single-parent and single-adult households is increasing, as well as is the number of expanded households, in which extended family members such as grandparents, cousins, or adult children live together in the family home. While 15 million mothers still make up the majority of single parents, 3.5 million fathers are also raising their children alone (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). Increasingly, single people and cohabitating couples are choosing to raise children outside of marriage through surrogates or adoption.

Some sociologists study social facts —the laws, morals, values, religious beliefs, customs, fashions, rituals, and cultural rules that govern social life—that may contribute to these changes in the family. Do people in the United States view marriage and family differently over the years? Do they view them differently than Peruvians? Do employment and economic conditions play a role in families? Other sociologists are studying the consequences of these new patterns, such as the ways children influence and are influenced by them and/or the changing needs for education, housing, and healthcare.

Sociologists identify and study patterns related to all kinds of contemporary social issues. The “Stop and Frisk” policy, the emergence of new political factions, how Twitter influences everyday communication—these are all examples of topics that sociologists might explore.

Studying Part and Whole: How Sociologists View Social Structures

A key component of the sociological perspective is the idea that the individual and society are inseparable. It is impossible to study one without the other. German sociologist Norbert Elias called the process of simultaneously analyzing the behavior of individuals and the society that shapes that behavior figuration .

Consider religion. While people experience religion in a distinctly individual manner, religion exists in a larger social context as a social institution . For instance, an individual’s religious practice may be influenced by what government dictates, holidays, teachers, places of worship, rituals, and so on. These influences underscore the important relationship between individual practices of religion and social pressures that influence that religious experience (Elias, 1978). In simpler terms, figuration means that as one analyzes the social institutions in a society, the individuals using that institution in any fashion need to be ‘figured’ in to the analysis.

Sociology in the Real World

Individual-society connections.

When sociologist Nathan Kierns spoke to his friend Ashley (a pseudonym) about the move she and her partner had made from an urban center to a small Midwestern town, he was curious about how the social pressures placed on a lesbian couple differed from one community to the other. Ashley said that in the city they had been accustomed to getting looks and hearing comments when she and her partner walked hand in hand. Otherwise, she felt that they were at least being tolerated. There had been little to no outright discrimination.

Things changed when they moved to the small town for her partner’s job. For the first time, Ashley found herself experiencing direct discrimination because of her sexual orientation. Some of it was particularly hurtful. Landlords would not rent to them. Ashley, who is a highly trained professional, had a great deal of difficulty finding a new job.

When Nathan asked Ashley if she and her partner became discouraged or bitter about this new situation, Ashley said that rather than letting it get to them, they decided to do something about it. Ashley approached groups at a local college and several churches in the area. Together they decided to form the town's first Gay-Straight Alliance.

The alliance has worked successfully to educate their community about same-sex couples. It also worked to raise awareness about the kinds of discrimination that Ashley and her partner experienced in the town and how those could be eliminated. The alliance has become a strong advocacy group, and it is working to attain equal rights for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender, or LGBTQ individuals.

Kierns observed that this is an excellent example of how negative social forces can result in a positive response from individuals to bring about social change (Kierns, 2011).

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Sociology 3e

- Publication date: Jun 3, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-1-what-is-sociology

© Jan 18, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 1. An Introduction to Sociology

Learning objectives.

1.1. What Is Sociology?

- Explain concepts central to sociology

- Describe the different levels of analysis in sociology: micro-sociology and macro-sociology

- Understand how different sociological perspectives have developed

1.2. The History of Sociology

- Explain why sociology emerged when it did

- Describe the central ideas of the founders of sociology

- Describe how sociology became a separate academic discipline

1.3. Theoretical Perspectives

- Explain what sociological theories are and how they are used

- Describe sociology as a multi-perspectival social science, which is divided into positivist, interpretive and critical paradigms

- Understand the similarities and differences between structural functionalism, critical sociology, and symbolic interactionism

1.4. Why Study Sociology?

- Explain why it is worthwhile to study sociology

- Identify ways sociology is applied in the real world

Introduction to Sociology

Concerts, sports games, and political rallies can have very large crowds. When you attend one of these events, you may know only the people you came with. Yet you may experience a feeling of connection to the group. You are one of the crowd. You cheer and applaud when everyone else does. You boo and yell alongside them. You move out of the way when someone needs to get by, and you say “excuse me” when you need to leave. You know how to behave in this kind of crowd.

It can be a very different experience if you are travelling in a foreign country and find yourself in a crowd moving down the street. You may have trouble figuring out what is happening. Is the crowd just the usual morning rush, or is it a political protest of some kind? Perhaps there was some sort of accident or disaster. Is it safe in this crowd, or should you try to extract yourself? How can you find out what is going on? Although you are in it, you may not feel like you are part of this crowd. You may not know what to do or how to behave.

Even within one type of crowd, different groups exist and different behaviours are on display. At a rock concert, for example, some may enjoy singing along, others may prefer to sit and observe, while still others may join in a mosh pit or try crowd surfing. On February 28, 2010, Sydney Crosby scored the winning goal against the United States team in the gold medal hockey game at the Vancouver Winter Olympics. Two hundred thousand jubilant people filled the streets of downtown Vancouver to celebrate and cap off two weeks of uncharacteristically vibrant, joyful street life in Vancouver. Just over a year later, on June 15, 2011, the Vancouver Canucks lost the seventh hockey game of the Stanley Cup finals against the Boston Bruins. One hundred thousand people had been watching the game on outdoor screens. Eventually 155,000 people filled the downtown streets. Rioting and looting led to hundreds of injuries, burnt cars, trashed storefronts and property damage totaling an estimated $4.2 million. Why was the crowd response to the two events so different?

A key insight of sociology is that the simple fact of being in a group changes your behaviour. The group is a phenomenon that is more than the sum of its parts. Why do we feel and act differently in different types of social situations? Why might people of a single group exhibit different behaviours in the same situation? Why might people acting similarly not feel connected to others exhibiting the same behaviour? These are some of the many questions sociologists ask as they study people and societies.

A dictionary defines sociology as the systematic study of society and social interaction. The word “sociology” is derived from the Latin word socius (companion) and the Greek word logos (speech or reason), which together mean “reasoned speech about companionship”. How can the experience of companionship or togetherness be put into words or explained? While this is a starting point for the discipline, sociology is actually much more complex. It uses many different methods to study a wide range of subject matter and to apply these studies to the real world.

The sociologist Dorothy Smith (1926 – ) defines the social as the “ongoing concerting and coordinating of individuals’ activities” (Smith 1999). Sociology is the systematic study of all those aspects of life designated by the adjective “social.” These aspects of social life never simply occur; they are organized processes. They can be the briefest of everyday interactions—moving to the right to let someone pass on a busy sidewalk, for example—or the largest and most enduring interactions—such as the billions of daily exchanges that constitute the circuits of global capitalism. If there are at least two people involved, even in the seclusion of one’s mind, then there is a social interaction that entails the “ongoing concerting and coordinating of activities.” Why does the person move to the right on the sidewalk? What collective process lead to the decision that moving to the right rather than the left is normal? Think about the T-shirts in your drawer at home. What are the sequences of linkages and social relationships that link the T-shirts in your chest of drawers to the dangerous and hyper-exploitive garment factories in rural China or Bangladesh? These are the type of questions that point to the unique domain and puzzles of the social that sociology seeks to explore and understand.

What Are Society and Culture?

Sociologists study all aspects and levels of society. A society is a group of people whose members interact, reside in a definable area, and share a culture. A culture includes the group’s shared practices, values, beliefs, norms and artifacts. One sociologist might analyze video of people from different societies as they carry on everyday conversations to study the rules of polite conversation from different world cultures. Another sociologist might interview a representative sample of people to see how email and instant messaging have changed the way organizations are run. Yet another sociologist might study how migration determined the way in which language spread and changed over time. A fourth sociologist might study the history of international agencies like the United Nations or the International Monetary Fund to examine how the globe became divided into a First World and a Third World after the end of the colonial era.

These examples illustrate the ways society and culture can be studied at different levels of analysis , from the detailed study of face-to-face interactions to the examination of large-scale historical processes affecting entire civilizations. It is common to divide these levels of analysis into different gradations based on the scale of interaction involved. As discussed in later chapters, sociologists break the study of society down into four separate levels of analysis: micro, meso, macro, and global. The basic distinction, however, is between micro-sociology and macro-sociology .

The study of cultural rules of politeness in conversation is an example of micro-sociology. At the micro- level of analysis, the focus is on the social dynamics of intimate, face-to-face interactions. Research is conducted with a specific set of individuals such as conversational partners, family members, work associates, or friendship groups. In the conversation study example, sociologists might try to determine how people from different cultures interpret each other’s behaviour to see how different rules of politeness lead to misunderstandings. If the same misunderstandings occur consistently in a number of different interactions, the sociologists may be able to propose some generalizations about rules of politeness that would be helpful in reducing tensions in mixed-group dynamics (e.g., during staff meetings or international negotiations). Other examples of micro-level research include seeing how informal networks become a key source of support and advancement in formal bureaucracies or how loyalty to criminal gangs is established.

Macro -sociology focuses on the properties of large-scale, society-wide social interactions: the dynamics of institutions, classes, or whole societies. The example above of the influence of migration on changing patterns of language usage is a macro-level phenomenon because it refers to structures or processes of social interaction that occur outside or beyond the intimate circle of individual social acquaintances. These include the economic and other circumstances that lead to migration; the educational, media, and other communication structures that help or hinder the spread of speech patterns; the class, racial, or ethnic divisions that create different slangs or cultures of language use; the relative isolation or integration of different communities within a population; and so on. Other examples of macro-level research include examining why women are far less likely than men to reach positions of power in society or why fundamentalist Christian religious movements play a more prominent role in American politics than they do in Canadian politics. In each case, the site of the analysis shifts away from the nuances and detail of micro-level interpersonal life to the broader, macro-level systematic patterns that structure social change and social cohesion in society.

The relationship between the micro and the macro remains one of the key problems confronting sociology. The German sociologist Georg Simmel pointed out that macro-level processes are in fact nothing more than the sum of all the unique interactions between specific individuals at any one time (1908), yet they have properties of their own which would be missed if sociologists only focused on the interactions of specific individuals. Émile Durkheim’s classic study of suicide (1897) is a case in point. While suicide is one of the most personal, individual, and intimate acts imaginable, Durkheim demonstrated that rates of suicide differed between religious communities—Protestants, Catholics, and Jews—in a way that could not be explained by the individual factors involved in each specific case. The different rates of suicide had to be explained by macro-level variables associated with the different religious beliefs and practices of the faith communities. We will return to this example in more detail later. On the other hand, macro-level phenomena like class structures, institutional organizations, legal systems, gender stereotypes, and urban ways of life provide the shared context for everyday life but do not explain its nuances and micro-variations very well. Macro-level structures constrain the daily interactions of the intimate circles in which we move, but they are also filtered through localized perceptions and “lived” in a myriad of inventive and unpredictable ways.

The Sociological Imagination

Although the scale of sociological studies and the methods of carrying them out are different, the sociologists involved in them all have something in common. Each of them looks at society using what pioneer sociologist C. Wright Mills called the sociological imagination , sometimes also referred to as the “sociological lens” or “sociological perspective.” In a sense, this was Mills’ way of addressing the dilemmas of the macro/micro divide in sociology. Mills defined sociological imagination as how individuals understand their own and others’ pasts in relation to history and social structure (1959). It is the capacity to see an individual’s private troubles in the context of the broader social processes that structure them. This enables the sociologist to examine what Mills called “personal troubles of milieu” as “public issues of social structure,” and vice versa.

Mills reasoned that private troubles like being overweight, being unemployed, having marital difficulties, or feeling purposeless or depressed can be purely personal in nature. It is possible for them to be addressed and understood in terms of personal, psychological, or moral attributes, either one’s own or those of the people in one’s immediate milieu. In an individualistic society like our own, this is in fact the most likely way that people will regard the issues they confront: “I have an addictive personality;” “I can’t get a break in the job market;” “My husband is unsupportive;” etc. However, if private troubles are widely shared with others, they indicate that there is a common social problem that has its source in the way social life is structured. At this level, the issues are not adequately understood as simply private troubles. They are best addressed as public issues that require a collective response to resolve.

Obesity, for example, has been increasingly recognized as a growing problem for both children and adults in North America. Michael Pollan cites statistics that three out of five Americans are overweight and one out of five is obese (2006). In Canada in 2012, just under one in five adults (18.4 percent) were obese, up from 16 percent of men and 14.5 percent of women in 2003 (Statistics Canada 2013). Obesity is therefore not simply a private trouble concerning the medical issues, dietary practices, or exercise habits of specific individuals. It is a widely shared social issue that puts people at risk for chronic diseases like hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. It also creates significant social costs for the medical system.

Pollan argues that obesity is in part a product of the increasingly sedentary and stressful lifestyle of modern, capitalist society, but more importantly it is a product of the industrialization of the food chain, which since the 1970s has produced increasingly cheap and abundant food with significantly more calories due to processing. Additives like corn syrup, which are much cheaper to produce than natural sugars, led to the trend of super-sized fast foods and soft drinks in the 1980s. As Pollan argues, trying to find a processed food in the supermarket without a cheap, calorie-rich, corn-based additive is a challenge. The sociological imagination in this example is the capacity to see the private troubles and attitudes associated with being overweight as an issue of how the industrialization of the food chain has altered the human/environment relationship, in particular with respect to the types of food we eat and the way we eat them.

By looking at individuals and societies and how they interact through this lens, sociologists are able to examine what influences behaviour, attitudes, and culture. By applying systematic and scientific methods to this process, they try to do so without letting their own biases and pre-conceived ideas influence their conclusions.

Studying Patterns: How Sociologists View Society