EnglishTutorHub

The Hanging Stranger Story Analysis With Summary And Theme

The Hanging Stranger – This article will tell you the short story entitled, “ The Hanging Stranger with story analysis, summary and theme in English. What is the theme, summary, plot, setting, character and point of view of the story, The Hanging Stanger by Philip K Dick ?

Table of contents

The hanging stanger story analysis, the hanging stanger by philip k. dick, the hanging stanger theme, the hanging stanger genre, the hanging stanger moral lesson, the hanging stanger characters, the hanging stanger summary.

The Hanging Stanger

At five o’clock Ed Loyce washed up, tossed on his hat and coat, got his car out and headed across town toward his TV sales store. He was tired. His back and shoulders ached from digging dirt out of the basement and wheeling it into the back yard. But for a forty-year-old man he had done okay. Janet could get a new vase with the money he had saved; and he liked the idea of repairing the foundations himself. It was getting dark. The setting sun cast long rays over the scurrying commuters, tired and grim-faced, women loaded down with bundles and packages, students, swarming home from the university, mixing with clerks and businessmen and drab secretaries. He stopped his Packard for a red light and then started it up again. The store had been open without him; he’d arrive just in time to spell the help for dinner, go over the records of the day, maybe even close a couple of sales himself. He drove slowly past the small square of green in the center of the street, the town park. There were no parking places in front of LOYCE TV SALES AND SERVICE. He cursed under his breath and swung the car in a U-turn. Again he passed the little square of green with its lonely drinking fountain and bench and single lamppost. From the lamppost something was hanging. A shapeless dark bundle, swinging a little with the wind. Like a dummy of some sort. Loyce rolled down his window and peered out. What the hell was it? A display of some kind? Sometimes the Chamber of Commerce put up displays in the square. Again he made a U-turn and brought his car around. He passed the park and concentrated on the dark bundle. It wasn’t a dummy. And if it was a display it was a strange kind. The hackles on his neck rose and he swallowed uneasily. Sweat slid out on his face and hands. It was a body. A human body. “Look at it!” Loyce snapped. “Come on out here!” Don Fergusson came slowly out of the store, buttoning his pin-stripe coat with dignity. “This is a big deal, Ed. I can’t just leave the guy standing there.” “See it?” Ed pointed into the gathering gloom. The lamppost jutted up against the sky—the post and the bundle swinging from it. “There it is. How the hell long has it been there?” His voice rose excitedly. “What’s wrong with everybody? They just walk on past!” Don Fergusson lit a cigarette slowly. “Take it easy, old man. There must be a good reason, or it wouldn’t be there.” “A reason! What kind of a reason?” Fergusson shrugged. “Like the time the Traffic Safety Council put that wrecked Buick there. Some sort of civic thing. How would I know?” Jack Potter from the shoe shop joined them. “What’s up, boys?” “There’s a body hanging from the lamppost,” Loyce said. “I’m going to call the cops.” “They must know about it,” Potter said. “Or otherwise it wouldn’t be there.” “I got to get back in.” Fergusson headed back into the store. “Business before pleasure.” Loyce began to get hysterical. “You see it? You see it hanging there? A man’s body! A dead man!” “Sure, Ed. I saw it this afternoon when I went out for coffee.” “You mean it’s been there all afternoon?” “Sure. What’s the matter?” Potter glanced at his watch. “Have to run. See you later, Ed.” Potter hurried off, joining the flow of people moving along the sidewalk. Men and women, passing by the park. A few glanced up curiously at the dark bundle—and then went on. Nobody stopped. Nobody paid any attention. “I’m going nuts,” Loyce whispered. He made his way to the curb and crossed out into traffic, among the cars. Horns honked angrily at him. He gained the curb and stepped up onto the little square of green. The man had been middle-aged. His clothing was ripped and torn, a gray suit, splashed and caked with dried mud. A stranger. Loyce had never seen him before. Not a local man. His face was partly turned away, and in the evening wind he spun a little, turning gently, silently. His skin was gouged and cut. Red gashes, deep scratches of congealed blood. A pair of steel-rimmed glasses hung from one ear, dangling foolishly. His eyes bulged. His mouth was open, tongue thick and ugly blue. “For Heaven’s sake,” Loyce muttered, sickened. He pushed down his nausea and made his way back to the sidewalk. He was shaking all over, with revulsion—and fear. Why? Who was the man? Why was he hanging there? What did it mean? And—why didn’t anybody notice? He bumped into a small man hurrying along the sidewalk. “Watch it!” the man grated. “Oh, it’s you, Ed.” Ed nodded dazedly. “Hello, Jenkins.” “What’s the matter?” The stationery clerk caught Ed’s aim “You look sick.” “The body. There in the park.” “Sure, Ed.” Jenkins led him into the alcove of LOYCE TV SALES AND SERVICE. “Take it easy.” Margaret Henderson from the jewelry store joined them. “Something wrong?” “Ed’s not feeling well.” Loyce yanked himself free. “How can you stand here? Don’t you see it? For God’s sake—” “What’s he talking about?” Margaret asked nervously. “The body!” Ed shouted. “The body hanging there!” More people collected. “Is he sick? It’s Ed Loyce. You okay, Ed?” “The body!” Loyce screamed, struggling to get past them. Hands caught at him. He tore loose. “Let me go! The police! Get the police!” “Ed—” “Better get a doctor!” “He must be sick.” “Or drunk.” Loyce fought his way through the people. He stumbled and half fell. Through a blur he saw rows of faces, curious, concerned, anxious. Men and women halting to see what the disturbance was. He fought past them toward his store. He could see Fergusson inside talking to a man, showing him an Emerson TV set. Pete Foley in the back at the service counter, setting up a new Philco. Loyce shouted at them frantically. His voice was lost in the roar of traffic and the murmuring around him. “Do something!” he screamed. “Don’t stand there! Do something! Something’s wrong! Something’s happened! Things are going on!” The crowd melted respectfully for the two heavy-set cops moving efficiently toward Loyce. “Name?” the cop with the notebook murmured. “Loyce.” He mopped his forehead wearily. “Edward C. Loyce. Listen to me. Back there—” “Address?” the cop demanded. The police car moved swiftly through traffic, shooting among the cars and buses. Loyce sagged against the seat, exhausted and confused. He took a deep shuddering breath. “1368 Hurst Road.” “That’s here in Pikeville?” “That’s right.” Loyce pulled himself up with a violent effort. “Listen to me. Back there. In the square. Hanging from the lamppost—” “Where were you today?” the cop behind the wheel demanded. “Where?” Loyce echoed. “You weren’t in your shop, were you?” “No.” He shook his head. “No, I was home. Down in the basement.” “In the basement?” “Digging. A new foundation. Getting out the dirt to pour a cement frame. Why? What has that to do with—” “Was anybody else down there with you?” “No. My wife was downtown. My kids were at school.” Loyce looked from one heavy-set cop to the other. Hope flickered across his face, wild hope. “You mean because I was down there I missed—the explanation? I didn’t get in on it? Like everybody else?” After a pause the cop with the notebook said: “That’s right. You missed the explanation.” “Then it’s official? The body—it’s supposed to be hanging there?” “It’s supposed to be hanging there. For everybody to see.” Ed Loyce grinned weakly. “Good Lord. I guess I sort of went off the deep end. I thought maybe something had happened. You know, something like the Ku Klux Klan. Some kind of violence. Communists or Fascists taking over.” He wiped his face with his breast-pocket handkerchief, his hands shaking. “I’m glad to know it’s on the level.” “It’s on the level.” The police car was getting near the Hall of Justice. The sun had set. The streets were gloomy and dark. The lights had not yet come on. “I feel better,” Loyce said. “I was pretty excited there, for a minute. I guess I got all stirred up. Now that I understand, there’s no need to take me in, is there?” The two cops said nothing. “I should be back at my store. The boys haven’t had dinner. I’m all right, now. No more trouble. Is there any need of—” “This won’t take long,” the cop behind the wheel interrupted. “A short process. Only a few minutes.” “I hope it’s short,” Loyce muttered. The car slowed down for a stoplight. “I guess I sort of disturbed the peace. Funny, getting excited like that and—” Loyce yanked the door open. He sprawled out into the street and rolled to his feet. Cars were moving all around him, gaining speed as the light changed. Loyce leaped onto the curb and raced among the people, burrowing into the swarming crowds. Behind him he heard sounds, snouts, people running. They weren’t cops. He had realized that right away. He knew every cop in Pikeville. A man couldn’t own a store, operate a business in a small town for twenty-five years without getting to know all the cops. They weren’t cops—and there hadn’t been any explanation. Potter, Fergusson, Jenkins, none of them knew why it was there. They didn’t know—and they didn’t care. That was the strange part. Loyce ducked into a hardware store. He raced toward the back, past the startled clerks and customers, into the shipping room and through the back door. He tripped over a garbage can and ran up a flight of concrete steps. He climbed over a fence and jumped down on the other side, gasping and panting. There was no sound behind him. He had got away. He was at the entrance of an alley, dark and strewn with boards and ruined boxes and tires. He could see the street at the far end. A street light wavered and came on. Men and women. Stores. Neon signs. Cars. And to his right—the police station. He was close, terribly close. Past the loading platform of a grocery store rose the white concrete side of the Hall of Justice. Barred windows. The police antenna. A great concrete wall rising up in the darkness. A bad place for him to be near. He was too close. He had to keep moving, get farther away from them. Them? Loyce moved cautiously down the alley. Beyond the police station was the City Hall, the old-fashioned yellow structure of wood and gilded brass and broad cement steps. He could see the endless rows of offices, dark windows, the cedars and beds of flowers on each side of the entrance. And—something else. Above the City Hall was a patch of darkness, a cone of gloom denser than the surrounding night. A prism of black that spread out and was lost into the sky. He listened. Good God, he could hear something. Something that made him struggle frantically to close his ears, his mind, to shut out the sound. A buzzing. A distant, muted hum like a great swarm of bees. Loyce gazed up, rigid with horror. The splotch of darkness, hanging over the City Hall. Darkness so thick it seemed almost solid. In the vortex something moved. Flickering shapes. Things, descending from the sky, pausing momentarily above the City Hall, fluttering over it in a dense swarm and then dropping silently onto the roof. Shapes. Fluttering shapes from the sky. From the crack of darkness that hung above him. He was seeing—them. For a long time Loyce watched, crouched behind a sagging fence in a pool of scummy water. They were landing. Coming down in groups, landing on the roof of the City Hall and disappearing inside. They had wings. Like giant insects of some kind. They flew and fluttered and came to rest—and then crawled crab-fashion, sideways, across the roof and into the building. He was sickened. And fascinated. Cold night wind blew around him and he shuddered. He was tired, dazed with shock. On the front steps of the City Hall were men, standing here and there. Groups of men coming out of the building and halting for a moment before going on. Were there more of them? It didn’t seem possible. What he saw descending from the black chasm weren’t men. They were alien—from some other world, some other dimension. Sliding through this slit, this break in the shell of the universe. Entering through this gap, winged insects from another realm of being. On the steps of the City Hall a group of men broke up. A few moved toward a waiting car. One of the remaining shapes started to re-enter the City Hall. It changed its mind and turned to follow the others. Loyce closed his eyes in horror. His senses reeled. He hung on tight, clutching at the sagging fence. The shape, the man-shape, had abruptly fluttered up and flapped after the others. It flew to the sidewalk and came to rest among them. Pseudo-men. Imitation men. Insects with ability to disguise themselves as men. Like other insects familiar to Earth. Protective coloration. Mimicry. Loyce pulled himself away. He got slowly to his feet. It was night. The alley was totally dark. But maybe they could see in the dark. Maybe darkness made no difference to them. He left the alley cautiously and moved out onto the street. Men and women flowed past, but not so many, now. At the bus stops stood waiting groups. A huge bus lumbered along the street, its lights flashing in the evening gloom. Loyce moved forward. He pushed his way among those waiting and when the bus halted he boarded it and took a seat in the rear, by the door. A moment later the bus moved into life and rumbled down the street. Loyce relaxed a little. He studied the people around him. Dulled, tired faces. People going home from work. Quite ordinary faces. None of them paid any attention to him. All sat quietly, sunk down in their seats, jiggling with the motion of the bus. The man sitting next to him unfolded a newspaper. He began to read the sports section, his lips moving. An ordinary man. Blue suit. Tie. A businessman, or a salesman. On his way home to his wife and family. Across the aisle a young woman, perhaps twenty. Dark eyes and hair, a package on her lap. Nylons and heels. Red coat and white Angora sweater. Gazing absently ahead of her. A high school boy in jeans and black jacket. A great triple-chinned woman with an immense shopping bag loaded with packages and parcels. Her thick face dim with weariness. Ordinary people. The kind that rode the bus every evening. Going home to their families. To dinner. Going home—with their minds dead. Controlled, filmed over with the mask of an alien being that had appeared and taken possession of them, their town, their lives. Himself, too. Except that he happened to be deep in his cellar instead of in the store. Somehow, he had been overlooked. They had missed him. Their control wasn’t perfect, foolproof.

ASIDE FROM THE SHORT STORY, The HANGING STRANGER , SEE ALSO : 140+ Best Aesop’s Fables Story Examples With Moral And Summary

Maybe there were others. Hope flickered in Loyce. They weren’t omnipotent. They had made a mistake, not got control of him. Their net, their field of control, had passed over him. He had emerged from his cellar as he had gone down. Apparently their power-zone was limited. A few seats down the aisle a man was watching him. Loyce broke off his chain of thought. A slender man, with dark hair and a small mustache. Well-dressed, brown suit and shiny shoes. A book between his small hands. He was watching Loyce, studying him intently. He turned quickly away. Loyce tensed. One of them? Or—another they had missed? The man was watching him again. Small dark eyes, alive and clever. Shrewd. A man too shrewd for them—or one of the things itself, an alien insect from beyond. The bus halted. An elderly man got on slowly and dropped his token into the box. He moved down the aisle and took a seat opposite Loyce. The elderly man caught the sharp-eyed man’s gaze. For a split second something passed between them. A look rich with meaning. Loyce got to his feet. The bus was moving. He ran to the door. One step down into the well. He yanked the emergency door release. The rubber door swung open. “Hey!” the driver shouted, jamming on the brakes. “What the hell—?” Loyce squirmed through. The bus was slowing down. Houses on all sides. A residential district, lawns and tall apartment buildings. Behind him, the bright-eyed man had leaped up. The elderly man was also on his feet. They were coming after him. Loyce leaped. He hit the pavement with terrific force and rolled against the curb. Pain lapped over him. Pain and a vast tide of blackness. Desperately, he fought it off. He struggled to his knees and then slid down again. The bus had stopped. People were getting off. Loyce groped around. His fingers closed over something. A rock, lying in the gutter. He crawled to his feet, grunting with pain. A shape loomed before him. A man, the bright-eyed man with the book. Loyce kicked. The man gasped and fell. Loyce brought the rock down. The man screamed and tried to roll away. “Stop! For God’s sake listen—” He struck again. A hideous crunching sound. The man’s voice cut off and dissolved in a bubbling wail. Loyce scrambled up and back. The others were there, now. All around him. He ran, awkwardly, down the sidewalk, up a driveway. None of them followed him. They had stopped and were bending over the inert body of the man with the book, the bright-eyed man who had come after him. Had he made a mistake? But it was too late to worry about that. He had to get out—away from them. Out of Pikeville, beyond the crack of darkness, the rent between their world and his. “Ed!” Janet Loyce backed away nervously. “What is it? What—” Ed Loyce slammed the door behind him and came into the living room. “Pull down the shades. Quick.” Janet moved toward the window. “But—” “Do as I say. Who else is here besides you?” “Nobody. Just the twins. They’re upstairs in their room. What’s happened? You look so strange. Why are you home?” Ed locked the front door. He prowled around the house, into the kitchen. From the drawer under the sink he slid out the big butcher knife and ran his finger along it. Sharp. Plenty sharp. He returned to the living room. “Listen to me,” he said. “I don’t have much time. They know I escaped and they’ll be looking for me.” “Escaped?” Janet’s face twisted with bewilderment and fear. “Who?” “The town has been taken over. They’re in control. I’ve got it pretty well figured out. They started at the top, at the City Hall and police department. What they did with the real humans they—” “What are you talking about?” “We’ve been invaded. From some other universe, some other dimension. They’re insects. Mimicry. And more. Power to control minds. Your mind.” “My mind?” “Their entrance is here, in Pikeville. They’ve taken over all of you. The whole town—except me. We’re up against an incredibly powerful enemy, but they have their limitations. That’s our hope. They’re limited! They can make mistakes!” Janet shook her head. “I don’t understand, Ed. You must be insane.” “Insane? No. Just lucky. If I hadn’t been down in the basement I’d be like all the rest of you.” Loyce peered out the window. “But I can’t stand here talking. Get your coat.” “My coat?” “We’re getting out of here. Out of Pikeville. We’ve got to get help. Fight this thing. They can be beaten. They’re not infallible. It’s going to be close—but we may make it if we hurry. Come on!” He grabbed her arm roughly. “Get your coat and call the twins. We’re all leaving. Don’t stop to pack. There’s no time for that.” White-faced, his wife moved toward the closet and got down her coat. “Where are we going?” Ed pulled open the desk drawer and spilled the contents out onto the floor. He grabbed up a road map and spread it open. “They’ll have the highway covered, of course. But there’s a back road. To Oak Grove. I got onto it once. It’s practically abandoned. Maybe they’ll forget about it.” “The old Ranch Road? Good Lord—it’s completely closed. Nobody’s supposed to drive over it.” “I know.” Ed thrust the map grimly into his coat. “That’s our best chance. Now call down the twins and let’s get going. Your car is full of gas, isn’t it?” Janet was dazed. “The Chevy? I had it filled up yesterday afternoon.” Janet moved toward the stairs. “Ed, I—” “Call the twins!” Ed unlocked the front door and peered out. Nothing stirred. No sign of life. All right so far. “Come on downstairs,” Janet called in a wavering voice. “We’re—going out for a while.” “Now?” Tommy’s voice came. “Hurry up,” Ed barked. “Get down here, both of you.” Tommy appeared at the top of the stairs. “I was doing my homework. We’re starting fractions. Miss Parker says if we don’t get this done—” “You can forget about fractions.” Ed grabbed his son as he came down the stairs and propelled him toward the door. “Where’s Jim?” “He’s coming.” Jim started slowly down the stairs. “What’s up, Dad?” “We’re going for a ride.” “A ride? Where?” Ed turned to Janet. “We’ll leave the lights on. And the TV set. Go turn it on.” He pushed her toward the set. “So they’ll think we’re still—” He heard the buzz. And dropped instantly, the long butcher knife out. Sickened, he saw it coming down the stairs at him, wings a blur of motion as it aimed itself. It still bore a vague resemblance to Jimmy. It was small, a baby one. A brief glimpse—the thing hurtling at him, cold, multi-lensed inhuman eyes. Wings, body still clothed in yellow T-shirt and jeans, the mimic outline still stamped on it. A strange half-turn of its body as it reached him. What was it doing? A stinger. Loyce stabbed wildly at it. It retreated, buzzing frantically. Loyce rolled and crawled toward the door. Tommy and Janet stood still as statues, faces blank. Watching without expression. Loyce stabbed again. This time the knife connected. The thing shrieked and faltered. It bounced against the wall and fluttered down. Something lapped through his mind. A wall of force, energy, an alien mind probing into him. He was suddenly paralyzed. The mind entered his own, touched against him briefly, shockingly. An utter alien presence, settling over him—and then it flickered out as the thing collapsed in a broken heap on the rug. It was dead. He turned it over with his foot. It was an insect, a fly of some kind. Yellow T-shirt, jeans. His son Jimmy… He closed his mind tight. It was too late to think about that. Savagely he scooped up his knife and headed toward the door. Janet and Tommy stood stone-still, neither of them moving. The car was out. He’d never get through. They’d be waiting for him. It was ten miles on foot. Ten long miles over rough ground, gulleys and open fields and hills of uncut forest. He’d have to go alone. Loyce opened the door. For a brief second he looked back at his wife and son. Then he slammed the door behind him and raced down the porch steps. A moment later he was on his way, hurrying swiftly through the darkness toward the edge of town. The early morning sunlight was blinding. Loyce halted, gasping for breath, swaying back and forth. Sweat ran down in his eyes. His clothing was torn, shredded by the brush and thorns through which he had crawled. Ten miles—on his hands and knees. Crawling, creeping through the night. His shoes were mud-caked. He was scratched and limping, utterly exhausted. But ahead of him lay Oak Grove. He took a deep breath and started down the hill. Twice he stumbled and fell, picking himself up and trudging on. His ears rang. Everything receded and wavered. But he was there. He had got out, away from Pikeville. A farmer in a field gaped at him. From a house a young woman watched in wonder. Loyce reached the road and turned onto it. Ahead of him was a gasoline station and a drive-in. A couple of trucks, some chickens pecking in the dirt, a dog tied with a string. The white-clad attendant watched suspiciously as he dragged himself up to the station. “Thank God.” He caught hold of the wall. “I didn’t think I was going to make it. They followed me most of the way. I could hear them buzzing. Buzzing and flitting around behind me.” “What happened?” the attendant demanded. “You in a wreck? A holdup?” Loyce shook his head wearily. “They have the whole town. The City Hall and the police station. They hung a man from the lamppost. That was the first thing I saw. They’ve got all the roads blocked. I saw them hovering over the cars coming in. About four this morning I got beyond them. I knew it right away. I could feel them leave. And then the sun came up.” The attendant licked his lip nervously. “You’re out of your head. I better get a doctor.” “Get me into Oak Grove,” Loyce gasped. He sank down on the gravel. “We’ve got to get started—cleaning them out. Got to get started right away.” They kept a tape recorder going all the time he talked. When he had finished the Commissioner snapped off the recorder and got to his feet. He stood for a moment, deep in thought. Finally he got out his cigarettes and lit up slowly, a frown on his beefy face. “You don’t believe me,” Loyce said. The Commissioner offered him a cigarette. Loyce pushed it impatiently away. “Suit yourself.” The Commissioner moved over to the window and stood for a time looking out at the town of Oak Grove. “I believe you,” he said abruptly. Loyce sagged. “Thank God.” “So you got away.” The Commissioner shook his head. “You were down in your cellar instead of at work. A freak chance. One in a million.” Loyce sipped some of the black coffee they had brought him. “I have a theory,” he murmured. “What is it?” “About them. Who they are. They take over one area at a time. Starting at the top—the highest level of authority. Working down from there in a widening circle. When they’re firmly in control they go on to the next town. They spread, slowly, very gradually. I think it’s been going on for a long time.” “A long time?” “Thousands of years. I don’t think it’s new.” “Why do you say that?” “When I was a kid… A picture they showed us in Bible League. A religious picture—an old print. The enemy gods, defeated by Jehovah. Moloch, Beelzebub, Moab, Baalin, Ashtaroth—” “So?” “They were all represented by figures.” Loyce looked up at the Commissioner. “Beelzebub was represented as—a giant fly.” The Commissioner grunted. “An old struggle.” “They’ve been defeated. The Bible is an account of their defeats. They make gains—but finally they’re defeated.” “Why defeated?” “They can’t get everyone. They didn’t get me. And they never got the Hebrews. The Hebrews carried the message to the whole world. The realization of the danger. The two men on the bus. I think they understood. Had escaped, like I did.” He clenched his fists. “I killed one of them. I made a mistake. I was afraid to take a chance.” The Commissioner nodded. “Yes, they undoubtedly had escaped, as you did. Freak accidents. But the rest of the town was firmly in control.” He turned from the window, “Well, Mr. Loyce. You seem to have figured everything out.” “Not everything. The hanging man. The dead man hanging from the lamppost. I don’t understand that. Why? Why did they deliberately hang him there?” “That would seem simple.” The Commissioner smiled faintly. “Bait.” Loyce stiffened. His heart stopped beating. “Bait? What do you mean?” “To draw you out. Make you declare yourself. So they’d know who was under control—and who had escaped.” Loyce recoiled with horror. “Then they expected failures! They anticipated—” He broke off. “They were ready with a trap.” “And you showed yourself. You reacted. You made yourself known.” The Commissioner abruptly moved toward the door. “Come along, Loyce. There’s a lot to do. We must get moving. There’s no time to waste.” Loyce started slowly to his feet, numbed. “And the man. Who was the man? I never saw him before. He wasn’t a local man. He was a stranger. All muddy and dirty, his face cut, slashed—” There was a strange look on the Commissioner’s face as he answered, “Maybe,” he said softly, “you’ll understand that, too. Come along with me, Mr. Loyce.” He held the door open, his eyes gleaming. Loyce caught a glimpse of the street in front of the police station. Policemen, a platform of some sort. A telephone pole—and a rope! “Right this way,” the Commissioner said, smiling coldly. As the sun set, the vice-president of the Oak Grove Merchants’ Bank came up out of the vault, threw the heavy time locks, put on his hat and coat, and hurried outside onto the sidewalk. Only a few people were there, hurrying home to dinner. “Good night,” the guard said, locking the door after him. “Good night,” Clarence Mason murmured. He started along the street toward his car. He was tired. He had been working all day down in the vault, examining the lay-out of the safety deposit boxes to see if there was room for another tier. He was glad to be finished. At the corner he halted. The street lights had not yet come on. The street was dim. Everything was vague. He looked around—and froze. From the telephone pole in front of the police station, something large and shapeless hung. It moved a little with the wind. What the hell was it? Mason approached it warily. He wanted to get home. He was tired and hungry. He thought of his wife, his kids, a hot meal on the dinner table. But there was something about the dark bundle, something ominous and ugly. The light was bad; he couldn’t tell what it was. Yet it drew him on, made him move closer for a better look. The shapeless thing made him uneasy. He was frightened by it. Frightened—and fascinated. And the strange part was that nobody else seemed to notice it. The Short story entitled, “The Hanging Stranger,” is from americanliterature.com

The summary and analysis of Philip K. Dick ‘s short story “ The Hanging Stranger ” help you figure out what the story is really about. Allow us to indulge ourselves by delving into the great story analysis of the story The Hanging Stranger by Philip K Dick .

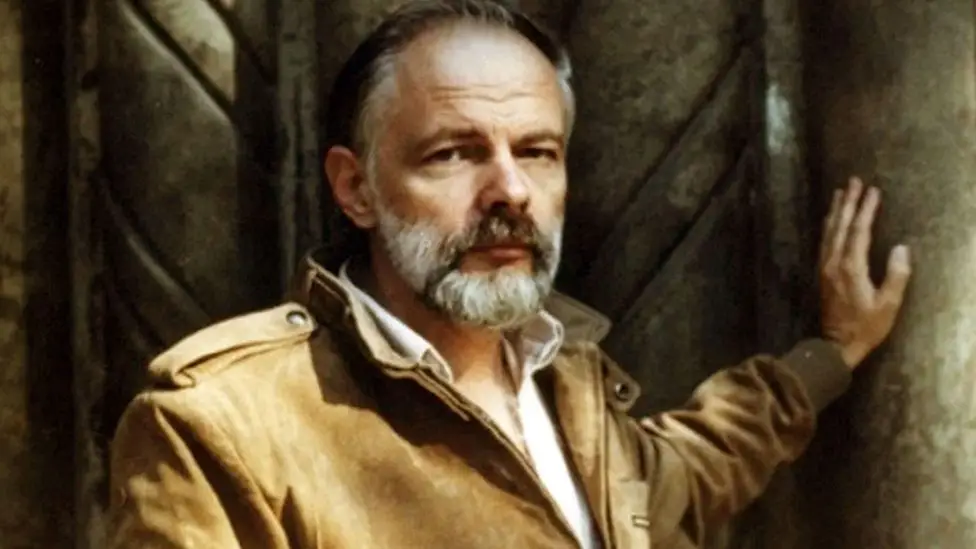

Philip K. Dick , whose full name was Philip Kindred Dick, was an American science-fiction writer who was born on December 16, 1928, in Chicago, Illinois, and died on March 2, 1982, in Santa Ana, California. His novels and short stories often show the psychological struggles of characters who are stuck in fake environments.

He is an underrated master of science fiction, and he wrote dystopian stories most of the time. In his cautionary stories, which were often funny and had gothic elements, he wrote about the effects of totalitarian regimes, monopoly power, and scary bonkers timers, among other things.

A Handful of Darkness (1955), The Variable Man and Other Stories (1957), and The Preserving Machine (1969) are among Dick’s story collections (1985). Several of his short stories and novels have been adapted for film, including “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale” (Total Recall, 1990 and 2012), “Second Variety” (Screamers, 1995), “ The Minority Report ” (Minority Report, 2002), and A Scanner Darkly (1977; film 2006). The Man in the High Castle was adapted (2015–19) as a serial drama.

Throughout, The Hanging Stranger , Dick emphasize the themes of bravery by being a hero in his own situation and cycle of actions in a way the the events happen over and over again.

The genre , The Hanging Stranger is a short story that also belongs to a scary classic science fiction thriller. It is a story of paranoia mixed with a lot of fear of insects.

In the story, Ed Loyce was shocked to find a stranger’s dead body hanging from a lamp post. But when he tells his friends and neighbors about the sad display, they act strangely, which makes him realize something disturbing.

The story emphasizes the moral lesson that to be practical, when you see something wrong, try to correct it.

Time needed: 2 minutes

Here are the characters in the short story The Hanging Stranger by Philip K Dick.

Loyce TV Sales and Service is owned by Ed Loyce. He noticed that there’s a man hanging on the lamp post and nobody cares.

He works at Loyce TV Sales and Service as a salesman.

He works at a shoe store near the park.

He is a stationary clerk.

She works at the jewelry store by the town park.

She is Ed Loyce’s wife.

They are Ed and Janet Loyce’s sons.

He tries to record Ed’s statement.

More Stories To Enjoy

Aside from this story ‘s summary analysis , here are more stories for you and your children to enjoy.

- Desiree’s Baby Short Story Analysis With Summary And Theme

- The Skylight Room Short Story Analysis With Summary And Theme

- Araby By James Joyce Short Story Analysis With Summary And Theme

- A Dark Brown Dog Short Story Analysis With Summary And Theme

- An Angel In Disguise Short Story Analysis With Summary And Theme

- The Cat By Mary E. Wilkins Freeman Story Analysis With Summary/Theme

- An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge Story Analysis With Summary/Theme

- About Love By Anton Chekhov Story Analysis With Summary And Theme

- The Monkey’s Paw Story Analysis With Summary And Theme

- The Luck Of Roaring Camp Story Analysis With Summary/Theme

- A Journey By Edith Wharton Story Analysis With Summary/Theme

- A New England Nun Story Analysis With Summary And Theme

This short story, called “ The Hanging Stranger” is written by Philip K Dick . In the summary and analysis, Ed’s curiosity helps him think about the current situation and give in to it. Undeniably, one of the most important symbols in the story is the idea of a society that only cares about itself.

Based on the analysis of the short story, Ed starts to figure this out when he sees the monsters fly into the government building and take over. In fact, the “stranger” who was hung from a tree was another sign.

If you have any questions or suggestions about this post, “ The Hanging Stranger by Philip K Dick Short Story Analysis With Summary , Characters, And Theme 2022 .” Let us know what you think by leaving a comment below.

Thanks for reading. God bless

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Project Gutenberg

- 73,221 free eBooks

- 14 by Philip K. Dick

The Hanging Stranger by Philip K. Dick

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The Hanging Stranger

Item preview.

Share or Embed This Item

Flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

1,516 Views

3 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

In collections.

Uploaded by arkiver2 on July 29, 2018

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

- Short Stories

- Junior's and Children's

- History and Biography

- Science and Technology

THE HANGING STRANGER

by Philip K Dick

Free download

Download options

How to download.

Related books

Second Variety

Piper in the Woods

The Defenders

The Hanging Stranger by Philip Dick - Text Based Evidence, Text Analysis Writing

- Google Apps™

Also included in

Description

Teaching how to write a literary analysis essay citing text evidence for "The Hanging Stranger" by Philip K. Dick has never been easier! This in-depth text dependent analysis (TDA) writing prompt resource guides students through a step-by-step process of writing an expository essay with textual evidence as support. It includes an expository writing graphic organizer , rubric, expository writing quiz , and an expository writing template .

All aspects of text evidence writing are covered in this resource: brainstorming ideas , developing a thesis statement , introducing supporting evidence , writing hooks and leads , and incorporating the 6 Traits of Writing ™.

The video, slide show, graphic organizer, worksheets, writing template, and rubric allow students to practice and develop their expository writing skills. The writing quiz reinforces guided note-taking techniques when used in conjunction with the instructional video. The detailed lesson plans make implementing informative writing easy for teachers.

The lesson can be used in class, assigned for distance learning, or given as independent student work. The instructional video with writing tutorial and template can also be presented as whole class instruction or assigned for students to complete at home.

Each resource listed below is included in Google Drive™ and print format.

*****************************************************************************************

This Citing Text Evidence Expository / Informative writing prompt lesson includes:

Entertaining Instructional Video with:

- Brainstorming ideas

- Prompt identification and comprehension

- Thesis statement development

- Rubric explanation

- How to Write an Expository Essay tutorial and writing template

- How to Write an Expository Essay writing quiz / guided note-taking

"The Hanging Stranger" by Philip K. Dick Detailed Lesson Plan with:

- Common Core State Standards indicated on lesson plan

- Instructional Focus

- Instructional Procedures

- Objectives/Goals

- Direct Instruction

- Guided Practice

- Differentiation

- ESE Strategies

- ELL Strategies

- I Can Statement

- Essential Question

"The Hanging Stranger" by Philip K. Dick Worksheets with:

- Brainstorming section

"The Hanging Stranger" by Philip K. Dick PowerPoint Presentation with:

- Introduction slide with prompt (interactive for students to identify key vocabulary)

- Brainstorming slide (interactive for students to list ideas)

- Standard and implied thesis development slides

- How to Write an Expository Essay tutorial and writing template slides

- Checklist slide

Expository Writing Quiz

Expository Rubric

Expository Graphic Organizer

Google Slides ™

Check out my other Middle School Text Based Analysis Writing Prompts:

- Text Analysis Writing Prompts

Connect with me for the latest Write On! with Jamie news:

- Write On! with Jamie Blog

- FB Community for 6-12 ELA Teachers

. . . and visit my WRITE ON! with Jamie website for a free TEXT EVIDENCE WRITING LESSON!

© Google Inc.™ All rights reserved. Google™ and the Google Logo are registered trademarks of Google Inc.™ Write On! with Jamie® is an independent company and is not affiliated with or endorsed by Google Inc.™

Terms of Use

Copyright © Write On! with Jamie. All rights reserved by author. All components of this product are to be used by the original downloader only. Copying for more than one teacher, classroom, department, school, or school system is prohibited unless additional licenses are purchased. This product may not be distributed or displayed digitally for public view. Failure to comply is a copyright infringement and a violation of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA). Clipart and elements found in this product are copyrighted and cannot be extracted and used outside of this file without permission or license. Intended for classroom and personal use ONLY.

Questions & Answers

Write on with jamie.

- We're hiring

- Help & FAQ

- Privacy policy

- Student privacy

- Terms of service

- Tell us what you think

- Share full article

The ‘Colorblindness’ Trap

How a civil rights ideal got hijacked.

Supported by

The ‘Colorblindness’ Trap: How a Civil Rights Ideal Got Hijacked

The fall of affirmative action is part of a 50-year campaign to roll back racial progress.

By Nikole Hannah-Jones

Nikole Hannah-Jones is a staff writer at the magazine and is the creator of The 1619 Project. She also teaches race and journalism at Howard University.

Anthony K. Wutoh, the provost of Howard University, was sitting at his desk last July when his phone rang. It was the new dean of the College of Medicine, and she was worried. She had received a letter from a conservative law group called the Liberty Justice Center. The letter warned that in the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision striking down affirmative action in college admissions, the school “must cease” any practices or policies that included a “racial component” and said it was notifying medical schools across the country that they must eliminate “racial discrimination” in their admissions. If Howard refused to comply, the letter threatened, the organization would sue.

Listen to this article, read by Janina Edwards

Open this article in the New York Times Audio app on iOS.

Wutoh told the dean to send him the letter and not to respond until she heard back from him. Hanging up, he sat there for a moment, still. Then he picked up the phone and called the university’s counsel: This could be a problem.

Like most university officials, Wutoh was not shocked in June when the most conservative Supreme Court in nearly a century cut affirmative action’s final thin thread. In Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, the court invalidated race-conscious admissions programs at Harvard and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Universities across the nation had been preparing for the ruling, trying both to assess potential liabilities and determine the best response.

But Howard is no ordinary university. Chartered by the federal government two years after the Civil War, Howard is one of about 100 historically Black colleges and universities, known as H.B.C.U.s. H.B.C.U. is an official government designation for institutions of higher learning founded from the time of slavery through the end of legal apartheid in the 1960s, mostly in the South. H.B.C.U.s were charged with educating the formerly enslaved and their descendants, who for most of this nation’s history were excluded from nearly all of its public and private colleges.

Though Howard has been open to students of all races since its founding in 1867, nearly all of its students have been Black. And so after the affirmative-action ruling, while elite, predominantly white universities fretted about how to keep their Black enrollments from shrinking, Howard (where I am a professor) and other H.B.C.U.s were planning for a potential influx of students who either could no longer get into these mostly white colleges or no longer wanted to try.

Wutoh thought it astounding that Howard — a university whose official government designation and mandate, whose entire reason for existing, is to serve a people who had been systematically excluded from higher education — could be threatened with a lawsuit if it did not ignore race when admitting students. “The fact that we have to even think about and consider what does this mean and how do we continue to fulfill our mission and fulfill the reason why we were founded as an institution and still be consistent with the ruling — I have to acknowledge that we have struggled with this,” he told me. “My broader concern is this is a concerted effort, part of an orchestrated plan to roll back many of the advances of the ’50s and ’60s. I am alarmed. It is absolutely regressive.”

Wutoh has reason to be alarmed. Conservative groups have spent the nine months since the affirmative-action ruling launching an assault on programs designed to explicitly address racial inequality across American life. They have filed a flurry of legal challenges and threatened lawsuits against race-conscious programs outside the realm of education, including diversity fellowships at law firms, a federal program to aid disadvantaged small businesses and a program to keep Black women from dying in childbirth. These conservative groups — whose names often evoke fairness and freedom and rights — are using civil rights law to claim that the Constitution requires “colorblindness” and that efforts targeted at ameliorating the suffering of descendants of slavery illegally discriminate against white people. They have co-opted both the rhetoric of colorblindness and the legal legacy of Black activism not to advance racial progress, but to stall it. Or worse, reverse it.

During the civil rights era, this country passed a series of hard-fought laws to dismantle the system of racial apartheid and to create policies and programs aimed at repairing its harms. Today this is often celebrated as the period when the nation finally triumphed over its original sin of slavery. But what this narrative obscures is that the gains of the civil rights movement were immediately met with a backlash that sought to subvert first the language and then the aims of the movement. Over the last 50 years, we have experienced a slow-moving, near-complete unwinding of the idea that this country owes anything to Black Americans for 350 years of legalized slavery and racism. But we have also undergone something far more dangerous: the dismantling of the constitutional tools for undoing racial caste in the United States.

Beginning in the 1970s, the Supreme Court began to vacillate on remedies for descendants of slavery. And for the last 30 years, the court has almost exclusively ruled in favor of white people in so-called reverse-discrimination cases while severely narrowing the possibility for racial redress for Black Americans. Often, in these decisions, the court has used colorblindness as a rationale that dismisses both the particular history of racial disadvantage and its continuing disparities.

This thinking has reached its legal apotheosis on the court led by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. Starting with the 2007 case Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1, the court found that it wasn’t the segregation of Black and Latino children that was constitutionally repugnant, but the voluntary integration plans that used race to try to remedy it. Six years later, Roberts wrote the majority opinion in Shelby v. Holder, gutting the Voting Rights Act, which had ensured that jurisdictions could no longer prevent Black Americans from voting because of their race. The act was considered one of the most successful civil rights laws in American history, but Roberts declared that its key provision was no longer needed, saying that “things have changed dramatically.” But a new study by the Brennan Center for Justice found that since the ruling, jurisdictions that were once covered by the Voting Rights Act because of their history of discrimination saw the gap in turnout between Black and white voters grow nearly twice as quickly as in other jurisdictions with similar socioeconomic profiles.

These decisions of the Roberts court laid the legal and philosophical groundwork for the recent affirmative-action case. Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard involved two of the country’s oldest public and private universities, both of which were financed to a significant degree with the labor of the enslaved and excluded slavery’s descendants for most of their histories. In finding that affirmative action was unconstitutional, Roberts used the reasoning of Brown v. Board of Education to make the case that because “the Constitution is colorblind” and “should not permit any distinctions of law based on race or color,” race cannot be used even to help a marginalized group. Quoting the Brown ruling, Roberts argued that “the mere act of ‘separating children’” because of their race generated “ ‘a feeling of inferiority’” among students.

But in citing Brown, Roberts spoke generically of race, rarely mentioning Black people and ignoring the fact that this earlier ruling struck down segregation because race had been used to subordinate them. When Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote those words in 1954, he was not arguing that the use of race harmed Black and white children equally. The use of race in assigning students to schools, Warren wrote, referring to an earlier lower-court decision, had “a detrimental effect upon colored children” specifically, because it was “interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the Negro group.”

Roberts quickly recited in just a few paragraphs the centuries-long legacy of legal discrimination against Black Americans. Then, as if flicking so many crumbs from the table, he used the circular logic of conservative colorblindness to dispatch that past with a pithy line: “Eliminating racial discrimination means eliminating all of it.”

By erasing the context, Roberts turned colorblindness on its head, reinterpreting a concept meant to eradicate racial caste to one that works against racial justice.

Roberts did not invent this subversion of colorblindness, but his court is constitutionalizing it. While we seem to understand now how the long game of the anti-abortion movement resulted in a historically conservative Supreme Court that last year struck down Roe v. Wade, taking away what had been a constitutional right, Americans have largely failed to see that a parallel, decades-long antidemocratic racial strategy was occurring at the same time. The ramifications of the recent affirmative-action decision are clear — and they are not something so inconsequential as the complexion of elite colleges and the number of students of color who attend them: We are in the midst of a radical abandonment of a compact that the civil rights movement forged, a shared understanding that racial inequality is harmful to democracy.

The End of Slavery, and the Instant Backlash

When this country finally eliminated first slavery and then racial apartheid, it was left with a fundamental question: How does a white-majority nation, which for nearly its entire history wielded race-conscious policies and laws that oppressed and excluded Black Americans, create a society in which race no longer matters? Do we ignore race in order to eliminate its power, or do we consciously use race to undo its harms?

Our nation has never been able to resolve this tension. Race, we now believe, should not be used to harm or to advantage people, whether they are Black or white. But the belief in colorblindness in a society constructed on the codification of racial difference has always been aspirational. And so achieving it requires what can seem like a paradoxical approach: a demand that our nation pay attention to race in order, at some future point, to attain a just society. As Justice Thurgood Marshall said in a 1987 speech, “The ultimate goal is the creation of a colorblind society,” but “given the position from which America began, we still have a very long way to go.”

Racial progress in the United States has resulted from rare moments of national clarity, often following violent upheavals like the Civil War and the civil rights movement. At those times, enough white people in power embraced the idea that racial subordination is antidemocratic and so the United States must counter its legacy of racial caste not with a mandated racial neutrality or colorblindness but with sweeping race-specific laws and policies to help bring about Black equality. Yet any attempt to manufacture equality by the same means that this society manufactured inequality has faced fierce and powerful resistance.

This resistance began as soon as slavery ended. After generations of chattel slavery, four million human beings were suddenly being emancipated into a society in which they had no recognized rights or citizenship, and no land, money, education, shelter or jobs. To address this crisis, some in Congress saw in the aftermath of this nation’s deadliest war the opportunity — but also the necessity — for a second founding that would eliminate the system of racial slavery that had been its cause. These men, known as Radical Republicans, believed that making Black Americans full citizens required color-consciousness in policy — an intentional reversal of the way race had been used against Black Americans. They wanted to create a new agency called the Freedmen’s Bureau to serve “persons of African descent” or “such persons as once had been slaves” by providing educational, food and legal assistance, as well as allotments of land taken from the white-owned properties where formerly enslaved people were forced to work.

Understanding that “race” was created to force people of African descent into slavery, their arguments in Congress in favor of the Freedmen’s Bureau were not based on Black Americans’ “skin color” but rather on their condition. Standing on the Senate floor in June 1864, Senator Charles Sumner quoted from a congressional commission’s report on the conditions of freed people, saying, “We need a Freedmen’s Bureau not because these people are Negroes but because they are men who have been for generations despoiled of their rights.” Senator Lyman Trumbull, an author of the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery, declared: “The policy of the states where slavery has existed has been to legislate in its interest. … Now, when slavery no longer exists, the policy of the government must be to legislate in the interest of freedom.” In a speech to Congress, Trumbull compelled “the people of the rebellious states” to be “as zealous and active in the passage of laws and the inauguration of measures to elevate, develop and improve the Negro as they have hitherto been to enslave and degrade him.”

But there were also the first stirrings of an argument we still hear today: that specifically aiding those who, because they were of African descent, had been treated as property for 250 years was giving them preferential treatment. Two Northern congressmen, Martin Kalbfleish, a Dutch immigrant and former Brooklyn mayor, and Anthony L. Knapp, a representative from Illinois, declared that no one would give “serious consideration” to a “bureau of Irishmen’s affairs, a bureau of Dutchmen’s affairs or one for the affairs of those of Caucasian descent generally.” So they questioned why the freedmen should “become these marked objects of special legislation, to the detriment of the unfortunate whites.” Representative Nelson Taylor bemoaned the Freedmen’s Bureau Act of 1866, which he accused of making a “distinction on account of color between two races.” He argued, “This, sir, is what I call class legislation — legislation for a particular class of the Blacks to the exclusion of all whites.”

Ultimately, the Freedmen’s Bureau bills passed, but only after language was added to provide assistance for poor white people as well. Already, at the very moment of racial slavery’s demise, we see the poison pill, the early formulation of the now-familiar arguments that helping a people who had been enslaved was somehow unfair to those who had not, that the same Constitution that permitted and protected bondage based on race now required colorblindness to undo its harms.

This logic helped preserve the status quo and infused the responses to other Reconstruction-era efforts that tried to ensure justice and equality for newly freed people. President Andrew Johnson, in vetoing the 1866 Civil Rights Act, which sought to grant automatic citizenship to four million Black people whose families for generations had been born in the United States, argued that it “proposes a discrimination against large numbers of intelligent, worthy and patriotic foreigners,” who would still be subjected to a naturalization process “in favor of the Negro.” Congress overrode Johnson’s veto, but this idea that unique efforts to address the extraordinary conditions of people who were enslaved or descended from slavery were unfair to another group who had chosen to immigrate to this country foreshadowed the arguments about Asian immigrants and their children that would be echoed 150 years later in Students for Fair Admissions.

As would become the pattern, the collective determination to redress the wrongs of slavery evaporated under opposition. Congress abolished the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1872. And just 12 years after the Civil War, white supremacists and their accommodationists brought Reconstruction to a violent end. The nation’s first experiment with race-based redress and multiracial democracy was over. In its place, the Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 ushered in the period of official racial apartheid when it determined that “the enforced separation of the races … neither abridges the privileges or immunities of the colored man … nor denies him the equal protection of the laws.” Over the next six decades, the court condoned an entire code of race law and policies designed to segregate, marginalize, exclude and subjugate descendants of slavery across every realm of American life. The last of these laws would stand until 1968, less than a decade before I was born.

Thurgood Marshall’s Path to Desegregation

In 1930, a young man named Thurgood Marshall, a native son of Baltimore, could not attend the University of Maryland’s law school, located in the city and state where his parents were taxpaying citizens. The 22-year-old should have been a shoo-in for admission. An academically gifted student, Marshall had become enamored with the Constitution after his high school principal punished him for a prank by making him read the founding document. Marshall memorized key parts of the Constitution, especially the Bill of Rights. After enrolling at Lincoln University, a prestigious Black institution, he joined the debate team and graduated with honors.

But none of that mattered. Only one thing did: Marshall was a descendant of slavery, and Black people, no matter their intellect, ambition or academic record, were barred by law from attending the University of Maryland. Marshall enrolled instead at Howard University Law School, where he studied under the brilliant Charles Hamilton Houston, whose belief that “a lawyer is either a social engineer or he’s a parasite on society” had turned the law school into the “West Point of civil rights.”

It was there that Marshall began to see the Constitution as a living document that must adapt to and address the times. He joined with Houston in crafting the strategy that would dismantle legal apartheid. After graduating as valedictorian, in one of his first cases, Marshall sued the University of Maryland. He argued that the school was violating the 14th Amendment, which granted the formerly enslaved citizenship and ensured Black Americans “equal protection under the law,” by denying Black students admission solely because of their race without providing an alternative law school for Black students. Miraculously, he won.

Nearly two decades later, Marshall stood before the Supreme Court on behalf of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in Brown v. Board of Education, arguing that the equal-protection clause enshrined in the 14th Amendment did not abide the use of racial classifications to segregate Black students. Marshall was not merely advancing a generic argument that the Constitution commands blindness to color or race. The essential issue, the reason the 14th Amendment existed, he argued, was not just because race had served as a means of classifying people, but because race had been used to create a system to oppress descendants of slavery — people who had been categorized as Black. Marshall explained that racial classification was being used to enforce an “inherent determination that the people who were formerly in slavery, regardless of anything else, shall be kept as near that stage as is possible.” The court, he said, “should make it clear that that is not what our Constitution stands for.” He sought the elimination of laws requiring segregation, but also the segregation those laws had created.

The Supreme Court, in unanimously striking down school segregation in its Brown decision, did not specifically mention the word “colorblind,” but its ruling echoed the thinking about the 14th Amendment in John Marshall Harlan’s lone dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson. “There is no caste here,” Harlan declared. “Our constitution is colorblind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.” But he also made it clear that colorblindness was intended to eliminate the subordination of those who had been enslaved, writing, “In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law.” He continued, “The arbitrary separation of citizens on the basis of race … is a badge of servitude.”

The court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education was not merely a moral statement but a political one. Racial segregation and the violent suppression of democracy among its Black citizens had become a liability for the United States during the Cold War, as the nation sought to stymie Communism’s attraction in non-European nations. Attorney General James P. McGranery submitted a brief to the Supreme Court on behalf of the Truman administration supporting a ruling against school segregation, writing: “It is in the context of the present world struggle between freedom and tyranny that the problem of racial discrimination must be viewed. The United States is trying to prove to the people of the world of every nationality, race and color that a free democracy is the most civilized and most secure form of government yet devised by man. … Racial discrimination furnishes grist for the Communist propaganda mills.”

Civil rights activists were finally seeing their decades-long struggle paying off. But the architects and maintenance crew of racial caste understood a fundamental truth about the society they had built: Systems constructed and enforced over centuries to subjugate enslaved people and their descendants based on race no longer needed race-based laws to sustain them. Racial caste was so entrenched, so intertwined with American institutions, that without race-based counteraction , it would inevitably self-replicate.

One can see this in the effort to desegregate schools after the Brown v. Board of Education ruling. Across the country, North and South, white officials eliminated laws and policies mandating segregation but also did nothing to integrate schools. They maintained unofficial policies of assigning students to schools based on race, adopting so-called race-neutral admissions requirements designed to eliminate most Black applicants from white schools, and they drew school attendance zones snugly around racially segregated neighborhoods. Nearly a decade after Brown v. Board, educational colorblindness stood as the law of the land, and yet no substantial school integration had occurred. In fact, at the start of 1963, in Alabama and Mississippi, two of the nation’s most heavily Black states, not a single Black child attended school with white children.

By the mid-1960s, the Supreme Court grew weary of the ploys. It began issuing rulings trying to enforce actual desegregation of schools. And in 1968, in Green v. New Kent County, the court unanimously decided against a Virginia school district’s “freedom-of-choice plan” that on its face adhered to the colorblind mandate of Brown but in reality led to almost no integration in the district. “The fact that in 1965 the Board opened the doors of the former ‘white’ school to Negro children and of the ‘Negro’ school to white children merely begins, not ends, our inquiry whether the Board has taken steps adequate to abolish its dual, segregated system,” the court determined.

The court ordered schools to use race to assign students, faculty and staff members to schools to achieve integration. Complying with Brown, the court determined, meant the color-conscious conversion of an apartheid system into one without a “ ‘white’ school and a ‘Negro’ school, but just schools.” In other words, the reality of racial caste could not be constitutionally subordinated to the ideal of colorblindness. Colorblindness was the goal, color-consciousness the remedy.

Using Race to End Racial Inequality

Hobart Taylor Jr., a successful lawyer who lived in Detroit, was mingling at a party in the nation’s capital in January 1961 to celebrate the inauguration of Lyndon B. Johnson as vice president of the United States. Taylor had not had any intention of going to the inauguration, but like Johnson, Taylor was a native son of Texas, and his politically active family were early supporters of Johnson. And so at a personal request from the vice president, Taylor reluctantly found himself amid the din of clinking cocktail glasses when Johnson stopped and asked him to come see him in a few days.

Taylor did not immediately go see Johnson. After a second request came in, in February, Taylor found himself in Johnson’s office. The vice president slid into Taylor’s hands a draft of a new executive order to establish the Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity, which Johnson would lead. This was to be one of President John F. Kennedy’s first steps toward establishing civil rights for Black people.

Taylor’s grandfather had been born into slavery, and yet he and Taylor’s father became highly successful and influential entrepreneurs and landowners despite Texas’ strict color line.

The apartheid society Taylor grew up in was changing, and the vice president of the United States had tapped him to help draft its new rules. How could he say no? Taylor had planned on traveling back to Detroit that night, but instead he checked into the Willard Hotel, where he worked so intently on the draft of the executive order that not only did he forget to eat dinner but also he forgot to tell his wife that he wasn’t coming home. The next day, Taylor worked and reworked the draft for what would become Executive Order 10925, enacted in March 1961.

A few years later, in an interview for the John F. Kennedy Library Oral History Program, Taylor would recall what he considered his most significant contribution. The draft he received said employers had to “take action” to ensure that job applicants and employees would not be discriminated against because of their race, creed, color or national origin. Taylor thought the wording needed a propellant, and so inserted the word “affirmative” in front of action. “I was torn between ‘positive’ and ‘affirmative,’ and I decided ‘affirmative’ on the basis of alliteration,” he said. “And that has, apparently, meant a great deal historically in the way in which people have approached this whole thing.”

Taylor added the word to the order, but it would be the other Texan — a man with a fondness for using the N-word in private — who would most forcefully describe the moral rationale, the societal mandate, for affirmative action. Johnson would push through Congress the 1964, 1965 and 1968 civil rights laws — the greatest civil rights legislation since Reconstruction.

But a deeply divided Congress did not pass this legislation simply because it realized a century after the Civil War that descendants of slavery deserved equal rights. Black Americans had been engaged in a struggle to obtain those rights and had endured political assassinations, racist murders, bombings and other violence. Segregated and impoverished Black communities across the nation took part in dozens of rebellions, and tanks rolled through American streets. The violent suppression of the democratic rights of its Black citizens threatened to destabilize the country and had once again become an international liability as the United States waged war in Vietnam.

But as this nation’s racist laws began to fall, conservatives started to realize that the language of colorblindness could be used to their advantage. In the fall of 1964, Barry Goldwater, a Republican who was running against President Johnson, gave his first major national speech on civil rights. Civil rights leaders like the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Roy Wilkins had lambasted Goldwater’s presidential nomination, with King saying his philosophy gave “aid and comfort to racists.” But at a carefully chosen venue — the Conrad Hilton in Chicago — in front of a well-heeled white audience unlikely to spout racist rhetoric, Goldwater savvily evoked the rhetoric of the civil rights movement to undermine civil rights. “It has been well said that the Constitution is colorblind,” he said. “And so it is just as wrong to compel children to attend certain schools for the sake of so-called integration as for the sake of segregation. … Our aim, as I understand it, is not to establish a segregated society or an integrated society. It is to preserve a free society.”

The argument laid out in this speech was written with the help of William H. Rehnquist. As a clerk for Justice Robert Jackson during the Brown v. Board of Education case, Rehnquist pushed for the court to uphold segregation. But in the decade that passed, it became less socially acceptable to publicly denounce equal rights for Black Americans, and Rehnquist began to deploy the language of colorblindness in a way that cemented racial disadvantage.

White Americans who liked the idea of equality but did not want descendants of slavery moving next door to them, competing for their jobs or sitting near their children in school were exceptionally primed for this repositioning. As Rick Perlstein wrote in his book “Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of American Consensus,” when it came to race, Goldwater believed that white Americans “didn’t have the words to say the truth they knew in their hearts to be right, in a manner proper to the kind of men they wanted to see when they looked in the mirror. Goldwater was determined to give them the words.”

In the end, Johnson beat Goldwater in a landslide. Then, in June 1965, a few months after Black civil rights marchers were barbarically beaten on Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge and two months before he would sign the historic Voting Rights Act into law, Johnson, now president of a deeply and violently polarized nation, gave the commencement address at Howard University. At that moment, Johnson stood at the pinnacle of white American power, and he used his platform to make the case that the country owed descendants of slavery more than just their rights and freedom.

“You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say, ‘You are free to compete with all the others,’ and still justly believe that you have been completely fair,” Johnson said. “This is the next and the more profound stage of the battle for civil rights. We seek not just freedom but opportunity. We seek not just legal equity but human ability, not just equality as a right and a theory but equality as a fact and equality as a result.”

For a brief moment, it seemed as if a grander, more just vision of America had taken hold. But while Goldwater did not win the election, 14 years later a case went before the Supreme Court that would signal the ultimate victory of Goldwater’s strategy.

Claiming Reverse Discrimination

Allan Bakke was enjoying a successful career at NASA when he decided he wanted to become a physician. Bakke grew up in a white middle-class family — his father worked for the Post Office, and his mother taught school. Bakke went to the University of Minnesota, where he studied engineering and joined the R.O.T.C. to help pay for college, and then served four years as a Marine, including seven months in Vietnam. It was there that Bakke became enamored with the medical profession. While still working at NASA, he enrolled in night courses to obtain a pre-med degree. In 1972, while he was in his 30s, Bakke applied to 11 medical schools, including at his alma mater, and was rejected by all 11.

One of the schools that Bakke, who was living in California at the time, applied to was the University of California at Davis. The school received 2,664 applications for 100 spots, and by the time he completed his application, most of the seats had already been filled. Some students with lower scores were admitted before he applied, and Bakke protested to the school, claiming that “quotas, open or covert, for racial minorities” had kept him out. His admission file, however, would show that it was his age that was probably a significant strike against him and not his race.

Bakke applied again the next year, and U.C. Davis rejected him again. A friend described Bakke as developing an “almost religious zeal” to fight what he felt was a system that discriminated against white people in favor of so-called minorities. Bakke decided to sue, claiming he had been a victim of “reverse” discrimination.

The year was 1974, less than a decade after Johnson’s speech on affirmative action and a few years after the policy had begun to make its way onto college campuses. The U.C. Davis medical school put its affirmative-action plan in place in 1970. At the time, its first-year medical-school class of 100 students did not include a single Black, Latino or Native student. In response, the faculty designed a special program to boost enrollment of “disadvantaged” students by reserving 16 of the 100 seats for students who would go through a separate admissions process that admitted applicants with lower academic ratings than the general admissions program.

From 1971 to 1974, 21 Black students, 30 Mexican American students and 12 Asian American students enrolled through the special program, while one Black student, six Mexican Americans and 37 Asian American students were admitted through the regular program. Bakke claimed that his right to equal protection under the 14th Amendment and the 1964 Civil Rights Act had been violated. Though these laws were adopted to protect descendants of slavery from racial discrimination and subordination, Bakke was deploying them to claim that he had been illegally discriminated against because he was white. The case became the first affirmative-action challenge decided by the Supreme Court and revealed just how successful the rhetorical exploitation of colorblindness could be.

Justice Lewis Powell, writing for a fractured court in 1978, determined that although the 14th Amendment was written primarily to bridge “the vast distance between members of the Negro race and the white ‘majority,’” the passage of time and the changing demographics of the nation meant the amendment must now be applied universally. In an argument echoing the debates over the Freedmen’s Bureau, Powell said that the United States had grown more diverse, becoming a “nation of minorities,” where “the white ‘majority’ itself is composed of various minority groups, most of which can lay claim to a history of prior discrimination at the hands of the State and private individuals.”

“The guarantee of equal protection cannot mean one thing when applied to one individual and something else when applied to a person of another color,” Powell wrote. “If both are not accorded the same protection, then it is not equal.” Powell declared that the medical school could not justify helping certain “perceived” victims if it disadvantaged white people who “bear no responsibility for whatever harm the beneficiaries of the special admissions program are thought to have suffered.”

But who or what, then, did bear the responsibility?

Bakke was raised in Coral Gables, a wealthy, white suburb of Miami whose segregationist founder proposed a plan to remove all Black people from Miami while serving on the Dade County Planning Board, and where the white elementary school did not desegregate until after it was ordered by a federal court to do so in 1970, the same year U.C. Davis began its affirmative-action program. The court did not contemplate how this racially exclusive access to top neighborhoods and top schools probably helped Bakke to achieve the test scores that most Black students, largely relegated because of their racial designation to resource-deprived segregated neighborhoods and educational facilities, did not. It did not mean Bakke didn’t work hard, but it did mean that he had systemic advantages over equally hard-working and talented Black people.

For centuries, men like Powell and Bakke had benefited from a near-100 percent quota system, one that reserved nearly all the seats at this nation’s best-funded public and private schools and most-exclusive public and private colleges, all the homes in the best neighborhoods and all the top, well-paying jobs in private companies and public agencies for white Americans. Men like Bakke did not acknowledge the systemic advantages they had accrued because of their racial category, nor all the ways their race had unfairly benefited them. More critical, neither did the Supreme Court. As members of the majority atop the caste system, racial advantage transmitted invisibly to them. They took notice of their race only when confronted with a new system that sought to redistribute some of that advantage to people who had never had it.