Interview: the Struggle for Peace in Mindanao, the Philippines

The southern Philippines has known a long history of armed conflict. Among those regions is Mindanao, where in February 2019 the Bangsamoro people voted to ratify the Bangsamoro Organic Law (BOL). This law is a big leap towards peace in the Southern Philippines. To understand why this is such a big leap for peace we interviewed Marc Batac, who is the Regional Programme Coordinator at our member organisation Initiatives for International Dialogue (IID) in the Philippines. IID has been involved in the peace process in Mindanao for almost twenty years.

To give us an overview of the conflict in Mindanao: how did the conflict come about, what are the root causes, who are the main actors and what is it about?

The root cause of armed conflict in Mindanao can be found in the narrative of Mindanao peoples’ continuing struggle for their right to self-determination. A struggle that involves an assertion of their identity and demand for meaningful governance in the face of the national government’s failure to realise genuine social progress and peace and development in the southern Philippines. The struggle is also a response to “historical injustices” and grave human rights violations committed against the peoples of Mindanao.

With the clamor to correct these historical injustices and to recognise their inherent right to chart their own political and cultural path, the Bangsamoro people – together with their non-Moro allies – have struggled to get their calls heard and acted upon by the central government.

A huge number of the victims of the conflict in Mindanao have been ordinary civilians: women and men, young and old who were either displaced from their communities or killed in the crossfire by bullets and bombs that recognize no gender, religion, creed or stature.

There are two opposing views when it comes to the armed struggle in the Bangsamoro region: While the central government had earlier viewed the armed struggle as an act of rebellion against the state, the other party has always claimed it as a legitimate exercise of their right to self-determination.

Over the years, the State has come to recognise the Bangsamoro and Indigenous Peoples struggle for just and lasting peace in Mindanao, albeit always within the framework of the country’s constitution.

A huge number of the victims of the conflict in Mindanao have been ordinary civilians: women and men, young and old who were either displaced from their communities or killed in the crossfire by bullets and bombs that recognize no gender, religion, creed or stature. The impact and social cost of the decades-old war to the people and the entire nation have been vicious and costly. The infographic on the cost of war in Mindanao (see below) explains previous Philippine governments’ huge spending on wars in Mindanao, which clearly talks about ‘lives lost’ rather than ‘lives improved’. Finding peaceful solutions to the causes of the armed conflict in Mindanao is never easy as the toll has affected not just Mindanao but the entire country. This has discouraged foreign and local investments and ultimately bleeding the nation’s coffers with the previous governments spending more on war than on basic social services.

While previous governments tried to resolve these conflicts, the root cause is the failure to address the Mindanao peoples legitimate struggle for their ‘right to self-determination, dignity and governance’, and is a major challenge to achieving sustainable peace in the region.

The conflict between the Government of the Philippines and the armed groups in Mindanao, particularly the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), is not the only conflict affecting the whole region. The conflict in Mindanao is multi-faceted, involving numerous armed groups, as well as clans, criminal gangs and political elites. Main actors to this decades-old conflict are: the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) and other groups such as the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF), Abu Sayyaf (considered a bandit group engaged in various criminal activities like kidnapping and bombings), as well as other armed non-state actors who are consistently ‘in conflict’ with the central government.

The Bangsamoro Organic Law (BOL) has been passed, which is for now the successful conclusion of a peace process. Can you explain what this is? And how it happened?

The purpose and intent of the law is to establish the new Bangsamoro political entity and provide for its basic structure of government. This also includes an expansion of the territory in recognition of the aspirations of the Bangsamoro people. Said law provides that the Bangsamoro Government will have a parliamentary form of government. The two key components of the peace process that will determine its eventual success are the passing of the BOL and the plebiscite for its ratification in the proposed Bangsamoro territory. With the BOL passage comes a roadmap that outlines a smooth transition leading to the creation of the Bangsamoro government that promises to fulfil the Bangsamoro’s aspirations for peace, justice, economic development and self-governance. The new Bangsamoro political entity will in effect abolish the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) and provide for a basic structure of government in recognition of the justness and legitimacy of the cause of the Bangsamoro people and their desire to chart their own political future through a democratic process.

The BOL is a product not only of political negotiations between the Bangsamoro and the Philippine government through their respective principals and negotiators but of the peacebuilding community’s decades of peacemaking and conflict prevention work and initiatives, both inside and outside of Mindanao and the Philippines.

What has civil society, and particularly Initiatives for International Dialogue (IID), done for this peacebuilding process? And why is it important?

IID became more involved into the Mindanao peace process when then President Joseph Estrada unleashed an “all-out war” against the MILF in 2000 that resulted in countless deaths, wounded and massive dislocation of mainly Moro communities. IID’s Moro and Mindanao partners sought the assistance of civil society and IID in helping to galvanize a response and projection of their voices and perspectives into the entire peace process. IID then proceeded to establish platforms and networks to concretize this accompaniment, forming the Mindanao Peoples Caucus (MPC) – a Tri-people (Moro, settlers and Indigenous peoples) network that engaged the peace process. MPC in turn established the Bantay Ceasefire (Ceasefire Watch) – a grassroots and community-based ceasefire-monitoring network.

GPPAC Southeast Asia members in the Philippines have been in the forefront of engaging the peace process in Mindanao since the “all-out war” declared by then President Estrada in 2000 against the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF).

Eventually, IID together with its partner communities were able to go through consensus building and lobbied in Congress a civil society agenda on crucial provisions in the draft BBL, conducted public advocacy activities and engaged lawmakers and the media.

Why is this such a big win for peace in the Philippines and the region?

GPPAC Southeast Asia members in the Philippines have been in the forefront of engaging the peace process in Mindanao since the “all-out war” declared by then President Estrada in 2000 against the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). It has since initiated and helped establish various networks for peace in the country, including Bantay Ceasefire, Mindanao Peaceweavers (MPW), Friends of the Bangsamoro (FoBM) and All-Out Peace (AOP) among others.

For us, the enactment of BOL is major step forward in achieving a just and sustainable peace in Mindanao. The BOL, if implemented according to its intent and purpose, could finally open a smooth path towards peace, development and social progress in the south of the Philippines. A product of a long-drawn peace negotiation, it also serves as a 'justice instrument', which can help in correcting historical injustices committed against the Bangsamoro people, the indigenous peoples, and other inhabitants of Mindanao--injustices that continue to haunt them up to this day.

The BOL, if implemented according to its intent and purpose, could finally open a smooth path towards peace, development and social progress in the south of the Philippines.

For numerous decades, Mindanao and its peoples have witnessed the exceptional savagery of armed conflict. The results have been equally vicious: from the unending cycle of multiple displacements by hapless communities to depleting our nation's fiscal health. In all these armed conflicts happening around Mindanao, the most marginalized and vulnerable especially our women, children and the elderly, were made to endure the profound and unceasing pains of conflicts they never wished to be part of. Now that the BOL has been successfully ratified, and the installation of a transition structure through the Bangsamoro Transition Authority (BTA) is underway, prospects towards a significant improvement in the lives of the peoples of Mindanao and hopefully in the whole country as well.

Are you hopeful that this change will be sustainable for a more peaceful Mindanao? And what needs to be done now?

While the ratification of the BOL and the eventual establishment of the Bangsamoro government are significant political milestones towards realising just peace and social progress not only for Mindanao but for the whole country, we believe that it is not the end-all and be-all of the struggle for peace. What still needs to be addressed during the process are difficult issues around governance, inclusion, land distribution, incursion of foreign aid, dealing with shadow economies and violent extremism in a fragile peace process. The promise of a more enhanced and meaningful autonomy can reach its full potential if a peacebuilding strategy, coupled with participation and protection pathways, is substantively embedded in governance in the incipient Bangsamoro. Civil society has to develop what is now a “post-conflict peacebuilding” paradigm, wherein we have to locate our role and added value during political transition around hard and intractable issues around land, governance, transitional justice and security.

Peace monitoring will continue to be a staple strategy fulfilling civil society’s role as a third party in the peace process. There are other aspects of the law that must be monitored and ensured especially when the “caretaker” BTA starts its job weeks from now, including how in the transition period the normalization programs will be equally supported and cascaded to ensure decommissioning of the MILF forces and support to these combatants and amnesty, transformation of camps and conflict-affected communities. This, of course, will entail bringing to the Normalization table the issues on displacement and post-reconstruction of those IDPs during the sieges in Zamboanga and Marawi cities, including the displaced indigenous communities due to intermittent armed hostilities in ancestral domain areas in the BARMM.

Civil society has to develop what is now a “post-conflict peacebuilding” paradigm, wherein we have to locate our role and added value during political transition around hard and intractable issues around land, governance, transitional justice and security.

Lastly, a whole of society approach in developing and implementing government programs in the BARMM shall respond to social cohesion, trust building and work on inclusion of minority and minoritized issues concerning the IPs in the region and the Christian population. From a civil society’s perspective, it is not a mere governance issue that is at stake here, but actualising the negotiated consensus (BOL, FAB/CAB, and all previously signed peace agreements) and the essence of social justice by guaranteeing affirmative action every step of the way. The civil society scorecard should be designed to critically monitor the following:

- Realizing meaningful autonomy and right to self-rule of the Bangsamoro (and the inhabitants of the region) based on their distinct cultural identities, historical struggle, faiths, heritage and traditions;

- Grant genuine and efficient fiscal autonomy for the Bangsamoro;

- Provide the Bangsamoro effective management and control over and benefits of the natural resources in the Bangsamoro territory;

- Full Inclusion of the Indigenous Peoples rights in the Bangsamoro governance to ensure the recognition and protection of their rights and to correct historical marginalization and exclusion; and

- Realizing a transitional justice and reconciliation program for the Bangsamoro. Heed previous recommendations to establish a Transitional Justice and Reconciliation Commission for the Bangsamoro (NTJRCB) that shall among others ensure and promote justice, healing and reconciliation.

- the Philippines

- Southeast Asia

Share this article on

Related highlights.

A Light at the End of the Tunnel? Moving Forward in the Philippines Peace Process

GPPAC Encourages Continued Peace Talks in the Philippines: “Peace talks are paramount for the sustainable future of the Philippines”

GPPAC Statement on Philippines Peace Process

Talk ain’t cheap when keeping the peace.

Peacebuilding from the grassroots: Resolving conflicts in Mindanao

Written by Julius Cesar Trajano .

Image credit: Mindanao Street Scene by Gary Todd /Flickr; Licence: CC0 1.0 DEED

The peace process between the Philippine government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) was hailed as a significant step towards ending four decades of armed conflict in Mindanao, southern Philippines. In 2018, the Philippine Congress ratified the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL) which aims to carve a self-ruled region for Muslims in Mindanao. In January 2019, a majority of the people of the Muslim provinces in Mindanao voted in the plebiscite for their communities to be included in the new autonomous region called the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (BARMM).

However, the Mindanao peace process should not end just because a peace agreement has been signed or a new autonomous region has been ratified by the people of Mindanao. Despite the progress that has been seen in relation to this peace process, significant challenges to the goal of inclusive peace and development in Muslim Mindanao remain. The presence of other rebel groups advocating for separatism, as well as violent extremist groups and warring political clans, all pose significant threats to peacebuilding in Mindanao.

The Mindanao peace process is a clear case study of the importance of bottom-up approaches to peacebuilding. This is a good time to explore comprehensively this bottom-up peacebuilding approach, which is being driven primarily by the vulnerable communities themselves.

In the context of conflict resolution in the southern Philippines, grassroots-based, bottom-up processes and initiatives are being generated to protect the peace process. This article examines three major contributions of local organisations and actors to the Mindanao peacebuilding process in recent years. These are: (1) countering violent extremism; (2) articulating women’s voices in the peace process; and (3) resolving local conflicts and ‘ rido ’ (clan wars).

Countering violent extremism

There is a new facet in the decades-old armed conflict in Muslim Mindanao: the emergence of violent extremist ideology that has been inspired by the rise of Islamic State (ISIS ) in the Middle East. In 2017, a large group of ISIS-inspired militants attacked and occupied for five months the City of Marawi, a Muslim-majority city in Mindanao. The militants were members of the extremist groups Abu Sayyaf and Maute that had declared allegiance to ISIS.

Experts have attributed the rise of pro-ISIS extremist groups in recent years partly to the delay in implementing the peace agreements agreed with the main Moro rebel movements – i.e. the MILF and the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) – as well as the refusal of other armed groups to participate in the peace process. Prior to the successful establishment of the BARMM under the governance of the MILF, the uncertain prospects for implementation of the peace agreements in the past created opportunities for violent extremist groups to discredit the peace process and gain popularity among marginalised sections of Filipino Muslims and also to recruit Moro youth.

Several organisations have started conducting activities to counter pro-ISIS violent extremism in Muslim Mindanao. One such organisation is the Institute for Autonomy and Government (IAG), a public-policy centre based in Mindanao which provides research, capacity-building training and technical assistance in order to advance meaningful autonomy and governance in Mindanao.

In 2017 the IAG conducted a research project to investigate the vulnerability of Muslim youth to radicalisation and recruitment by violent extremist groups in Mindanao. The IAG report offers policy recommendations to counter violent extremism. One such recommendation is for the Philippine government to adopt a comprehensive policy framework to counter extremism that can guide national and local government units in crafting long-term programmes for its prevention.

Local religious leaders also play an important role in countering violent extremism. During the Marawi crisis, there was a strong focus on their role and how they could counter the narrative of the pro-ISIS Maute group. Established in 1996, the Bishops-Ulama Conference (BUC) is a key institution for advancing the peace process in Mindanao. BUC is composed of Catholic bishops, Muslim ulama and Protestant bishop-pastors in Mindanao who collectively envision a society where different religious communities can live together peacefully and harmoniously.

At the height of the Marawi conflict, BUC convened the Multi-Sectoral Peace Conference in Cagayan de Oro City, Mindanao in July 2017. The Conference gathered together religious leaders from Mindanao, military officials, local government officials and NGOs. Together, the BUC and its dialogue partners strongly recommended the introduction of peace education with Islamic concepts as an antidote to extremism.

Articulating women’s voices

Women’s NGOs also contribute to the Mindanao peace process beyond the formal peace talks. Educating the public on Bangsamoro history is one of their contributions. Moro women and peace advocates have cited the significance of educating both the Bangsamoro and Filipino people on Bangsamoro history in order to gain nationwide support for the success of the peace process.

One important movement that conducts peace education is the Women’s Organisation Movement in the Bangsamoro (WOMB), a consortium of Bangsamoro women’s organisations mostly engaged in peace advocacy work. WOMB regularly organises advocacy training workshops in a bid to provide peace advocates and women’s organisations with appropriate strategies in policy advocacy towards realising Bangsamoro autonomy.

Another contribution of women’s organisations to the peace process is assisting war evacuees. Most recently, at the height of the Marawi conflict in 2017, a Marawi-based NGO composed of Muslim women called the Al-Mujadilah Development Foundation was at the forefront of providing life-saving aid to an estimated 220,000 civilians affected by the conflict in the city. Its aid workers explained that women and children affected by the conflict were more vulnerable to sexual harassment and other forms of gender-based violence, even in evacuation centres. Thus, women aid volunteers and workers need to be on the frontline of providing humanitarian relief, given that they understand women’s needs best of all.

Resolving local conflicts and rido

Community-based mediation is another important process outside the formal peace talks. This is primarily driven by the prevalence of local conflicts such as rido in Muslim Mindanao. Rido, or clan wars, have further complicated the delicate security situation in Muslim Mindanao. Rido is the state of recurring hostilities among families and clans, involving retaliatory acts of armed conflict triggered by an affront or disgrace to the honour of a family or its members. As of 2017, most of the 235 unresolved rido cases were due to land ownership issues and local politics.

In this regard, resolving local rido cases and the associated armed violence must be considered as another peace process which complements the broader Mindanao peace process. Several NGOs are conducting community-based mediation to resolve rido . One such organisation is Tumikang Sama Sama (TSS), which means ‘Together We Move Forward’ in the Tausug language of Sulu Province. TSS is now a large independent organisation of well-respected community mediators who seek to address the security challenges in Sulu Province arising from rido . Between 2010 and 2014, TSS handled 82 rido cases and helped formally settle 48 such cases in conflict-ridden Sulu. TSS uses a combination of formal legal mechanisms and indigenous cultural traditions to achieve results.

As demonstrated in this article, there are several significant issues such as clan wars and an increase in extremist ideology that are not directly addressed by the top-down peace process or by the Bangsamoro Basic Law. Grassroots actors can contribute to mitigating and resolving these issues that may otherwise threaten the sustainability of the overall peace process.

Julius Cesar Trajano is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Non-Traditional Security Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this article.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

11 The Philippines: Peace Talks and Autonomy in Mindanao

- Published: March 2019

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter examines how political interests in Mindanao and in Manila have made it difficult to resolve the territorial cleavage in southern Philippines, even though the 1987 Constitution envisioned Muslim autonomy within the unitary republic. It first provides a historical background on the Muslim insurgency in Mindanao, led by the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) and later, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). It also considers the 1976 Tripoli agreement signed under martial law, the drafting of the 1987 Constitution, and the creation of the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao in 1989. It goes on to describe the period of constitutional engagement and more specifically, the “constitutional moment” for resolving the Mindanao question that began in mid-2010. Finally, it analyzes the outcome of the peace talks between the government and the Moro insurgents, along with some of significant the lessons that can be drawn from the experience.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

United States Institute of Peace

Home ▶ Publications

The Long Road to Peace in the Southern Philippines

USIP editorial series provides perspectives from the Bangsamoro region.

Tuesday, January 18, 2022 / By: Brian Harding ; Haroro J. Ingram

Publication Type: Analysis

For four centuries, the Muslim-majority areas in the southern reaches of the Philippines have resisted domination authorities in Manila, the capital city of the Philippines, whether its leaders were Spanish, American or Filipino. This dynamic has spawned insurgencies, glimmers of hope for peaceful coexistence and repeated disappointment — all amid endemic violence and poverty.

Over the past five and a half years, while the world has focused on Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte’s excesses, particularly his deadly war on drugs, a groundbreaking possibility for peace has emerged under the first president of the Philippines to hail from Mindanao, the second-largest island located in the southern part of the archipelago.

As the Philippines gears up for general elections in May 2022 that will see a term-limited Duterte cede power, there is an urgent need for Manila and the international community to support the most promising opportunity for a sustainable peace in Mindanao in decades, a hopeful development that has too often flown under the radar.

The United States has a stake in peace in the Southern Philippines, most acutely on two fronts. First, as the United States and the Philippines work to deepen cooperation on external security challenges, principally in the South China Sea, peace in Mindanao would remove a key domestic focus for the armed forces of the Philippines and free resources for other priorities. Second, sustainable peace — and good local governance — would significantly help to address drivers of transnational crime, including terrorism.

It is within this context that the U.S. Institute of Peace is launching an initiative to bring attention to the peace process and the development of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), which was established in early 2019 as part of a peace agreement to end nearly five decades of conflict between the Philippine government and Moro secessionists in Mindanao. This effort will include a series of articles written by Filipino authors that analyze key issues and challenges at this historic juncture of Bangsamoro peace efforts.

The Latest Push for Peace in Mindanao

The establishment of the BARMM in 2019 brought with it the most promising opportunity for sustainable peace in living memory. After decades of war and cyclical peace process failures, an 80-member Bangsamoro Transition Authority (BTA) was appointed by Duterte to implement the two-track peace process and take the region to its first elections in May 2022. Most BTA ministers are former guerrillas who had devoted their lives to revolutionary war but now were responsible for founding a parliamentary system, implementing a legal and policy architecture, establishing government bureaucracies, decommissioning combatants and providing basic services to their impoverished communities.

Under any circumstances, the challenges facing the new Bangsamoro authorities were immense and the timelines in the Bangsamoro Organic Law for achieving key political, legal and normalization milestones overly optimistic. But then, almost a year into the transition period, COVID-19 hit the Philippines. By mid-2020, the BTA was increasingly (and understandably) prioritizing its pandemic response. By the end of 2020, Bangsamoro authorities and civil society were calling for an extension of the transition period, which was eventually granted and signed into law by Duterte on October 28, 2021. The extension grants Bangsamoro authorities three more years to complete the transition process and take the BARMM to its first elections in May 2025.

While the extension may have given the BTA more time, it has done little to relieve pressures on Bangsamoro authorities to succeed in their efforts. For instance, expectation management is a concern for every peace process, but it is especially concerning in the BARMM. In many communities, hopes for what peace dividends will deliver socially, economically and politically are extraordinarily high, highlighting the potential for acute disappointment if those hopes are not met. One of the most concerning issues has been the faltering normalization track that was meant to decommission 40,000 ex-combatants, their arms and camps but has left many disgruntled and many more still needing to be processed.

Extension has also brought with it added uncertainties. For example, a clause in the transition extension means that new BTA ministers could be appointed by either Duterte or the newly elected president in May 2022. At the first Bangsamoro Donor’s Forum organized by the Bangsamoro Planning and Development Authority on December 13, 2021, it was clear that at this historic juncture in the struggle for peace in Mindanao there are plenty of reasons to be cautiously optimistic for the future.

As the authors featured in this USIP series explore, the Bangsamoro region is delicately balanced and the resolution (or otherwise) of some key issues may prove the difference between a peaceful and even prosperous BARMM or another generation traumatized by war.

Inside the Struggle for Peace in the Bangsamoro Region

This USIP series seeks to bring attention to peace efforts in the Southern Philippines by showcasing a broad thematic and multisector spectrum of local perspectives from inside the BARMM. The Filipino contributors featured in this series will explore a range of challenges and opportunities for peace in the Bangsamoro region. From the vital role of Bangsamoro women as peace leaders and the key issues associated with the extension of the transition period to the Bangsamoro government’s inclusivity challenge and the impact of COVID-19 on the achievement of peace and development milestones, the series will take readers inside the multisector effort to achieve peace in Mindanao.

If there is one overarching theme that unites this eclectic collection of authors and subjects, it is the issue of balance. For the Bangsamoro, this challenge arises in discovering how to both embrace and protect the region’s rich ethnic and cultural diversity while also championing a shared Bangsamoro identity. History offers its own challenges as a source of traumas that weigh heavily on the present, as well as a source of immense pride and inspiration. After decades of bloody wars and failed peace efforts, local expectations for what the peace dividends should deliver will need to be balanced by the realities of what can be delivered. All the while, peace spoilers will be looking to exploit any opportunity to tip the balance once again toward war.

Hanging in the Balance

The picture that will emerge from this series is of a complicated and delicately balanced peace process that has every reason to succeed or fail. If there is one lesson to emerge from Mindanao’s too-often bloody history, it is that the aftermaths of failed peace efforts have been a boon for the rise of violent groups exploiting the politics of dashed expectations. For the international community to appreciate why the current confluence of dynamics in the BARMM is raising the stakes for the peace process, it is vital to read the nuanced ground-level perspectives of locals on the inside of the peace process.

Haroro J. Ingram is a senior research fellow with the Program on Extremism at George Washington University and a fellow with Mindanao State University (Marawi).

Related Publications

Indonesia’s Nickel Bounty Sows Discord, Enables Chinese Control

Thursday, March 21, 2024

By: Brian Harding ; Kayly Ober

As the world moves toward cleaner forms of energy, specific minerals and metals that support this transition have become “critical.” Nickel — a major component used in electric vehicle (EV) batteries — is one such critical mineral. Demand for battery metals is forecast to increase 60-70 percent in the next two decades. This may be a boon for some. But in Indonesia, which produces more than half of the world’s nickel supply, it has led to political, environmental and ethical complications.

Type: Analysis

Environment ; Global Policy

Are China and the Philippines on a Collision Course?

Thursday, March 14, 2024

By: Dean Cheng ; Carla Freeman, Ph.D. ; Brian Harding ; Andrew Scobell, Ph.D.

Tensions between China and the Philippines have sharply escalated in recent months over territorial disputes in the South China Sea that could draw in the United States.

Type: Question and Answer

Global Policy

Two Years Later, What Has the Indo-Pacific Strategy Achieved?

Thursday, February 15, 2024

By: Carla Freeman, Ph.D. ; Mirna Galic ; Daniel Markey, Ph.D. ; Vikram J. Singh

This month marks the second anniversary of the Biden administration’s Indo-Pacific Strategy (IPS). USIP experts Carla Freeman, Mirna Galic, Daniel Markey, and Vikram Singh assess what the strategy has accomplished in the past two years, how it has navigated global shocks and its impact on partnerships in the region.

Type: Analysis ; Question and Answer

The Cascading Risks of a Resurgent Islamic State in the Philippines

Tuesday, January 9, 2024

By: Haroro J. Ingram

On December 3, militants placed a bomb amongst parishioners gathered for Catholic Mass on the floor of the Mindanao State University (MSU) gym in Marawi City. Minutes later, it detonated killing four and injuring dozens. The Islamic State (ISIS) claimed that its East Asia affiliate was responsible for the attack. After a year of heavy losses, many had hoped that the threat posed by pro-ISIS groups was dissipating. Unfortunately, the violence that has characterized the six weeks since the bombing suggests that the Islamic State East Asia (ISEA) is attempting a resurgence timed for a critical 16-month period for the Philippines. The stakes are very high.

Conflict Analysis & Prevention ; Violent Extremism

- COVID-19 Full Coverage

- Cover Stories

- Ulat Filipino

- Special Reports

- Personal Finance

- Other sports

- Pinoy Achievers

- Immigration Guide

- Science and Research

- Technology, Gadgets and Gaming

- Chika Minute

- Showbiz Abroad

- Family and Relationships

- Art and Culture

- Health and Wellness

- Shopping and Fashion

- Hobbies and Activities

- News Hardcore

- Walang Pasok

- Transportation

- Missing Persons

- Community Bulletin Board

- GMA Public Affairs

- State of the Nation

- Unang Balita

- Balitanghali

- News TV Live

Fighting and talking: A Mindanao conflict timeline

Â

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Mindanao Conflict in the Philippines: Ethno-Religious War or Economic Conflict?

The Politics of Death: Political Violence in Southeast Asia

RELATED PAPERS

Journal of Educational Society for Social Studies.

Prof. Dr.Naglaa M. El-Nahass

Virginie Rachmuhl

Retratos Da Escola

Dalila Oliveira

Ramars Amanchy

Revista de la Facultad de Odontología

cristina loha

Medical Archives

Sefedin Muçaj

Leonardo Rossiello

Baruj Clavellina

Journal for Contemporary History

Steve Gruzd

Muhammad Majid

Torsir Pasauran

ghina meza laureano

Terrestrial, Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences

Donald Reed

Deflita Lumi

Katrien Vanderwee

BIO-PEDAGOGI

Rahmawati Darussyamsu

Dr. Ajit Yadav

Interventionalradiology India , Arun Gupta

Victoriano Pastor Julián

Michael Hoffer

Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment

A. Jacholkowski

Bioconjugate Chemistry

Christie Hunter

Journal of the Acoustical Society of America

Volker Mellert

Marine Biology

Wann Nian Tzeng

Jurnal Pendidikan Fisika Unismuh

Hesti Pebriayani

See More Documents Like This

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Subscribe Now

EXPLAINER: Why Duterte’s sudden call for Mindanao independence won’t fly

Already have Rappler+? Sign in to listen to groundbreaking journalism.

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Photo courtesy of Malacañang; Graphics by Marian Hukom/Rappler

MANILA, Philippines – A couple of days after former president Rodrigo Duterte accused his successor Ferdinand Marcos Jr. of involvement in the illegal drug trade, the man from Davao City stepped up his rhetoric by calling for Mindanao’s independence.

“What is at stake now is our future, so we’ll just separate,” Duterte was quoted as saying on January 30. The former mayor even claimed he had asked his former House speaker – incumbent Davao del Norte 1st District Representative Pantaleon Alvarez – to gather signatures in favor of the advocacy.

The government did not take the call sitting down, decrying the proposal that has – at the same time – baffled critics due to its lack of specifics.

Rappler sums up the gigantic obstacles that advocates of Mindanao secession are facing to make that vision – if they are really serious about it – a reality.

Advocates want to emulate the path to independence of some young nations, but their lived realities are different from those of Mindanao.

In the 2006 book Secession: International Law Perspectives , professor Antonello Tancredi wrote: “International law neither prohibits nor authorizes secession, but simply acknowledges the result of de facto processes which may lead to the birth of new states.”

There is no manual on successful secessions, and separatists can only learn from the experience of other countries.

Duterte-era chief presidential legal counsel Salvador Panelo brought up the statehoods of Singapore and Timor-Leste, but the conditions that paved the way for their independence are different from the realities in Mindanao.

Singapore, for instance, did not gain independence voluntarily . It was expelled by Malaysia in 1965, due to irreconcilable differences in ideology and politics.

Timor-Leste, meanwhile, is a case that inspires Duterte, who said on February 7: “My proposal of a Mindanao secession is a legal process that will be brought to the United Nations (UN), just like what happened to Timor-Leste.”

Yes, the UN organized a referendum in Timor-Leste in 1999, the watershed vote that resulted in its independence from Indonesia. But the young nation’s journey of self-determination was bloody, and its experience does not necessarily bear strong similarities to that of Mindanao.

While there were state-sanctioned killings that triggered the Moro insurgency in the southern Philippines, Timor-Leste had to grapple with what numerous scholars believe is a genocide at the tail-end of the 20th century. The atrocities during that time prompted the rise and consolidation of pro-independence organizations, which Mindanao does not have at the moment.

Jabidah and Merdeka: The inside story

The downfall of military dictator Suharto also ushered in an era of democratic reforms , and the succeeding president, B.J. Habibie, allowed the people of Timor-Leste to pick either full independence from Indonesia or special autonomy.

The Philippine government has spoken strongly against the call for an independent Mindanao.

It seems implausible that the Marcos administration would one day just let political foes in Mindanao do what they want, such as enabling a referendum on secession. After all, the government has already been adamant about quashing Duterte’s out-of-left-field proposal that made national headlines.

Issuing their own statements to reject the former president’s call were the justice and interior departments, as well as National Security Adviser Eduardo Año and Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process Carlito Galvez Jr. – both Marcos appointees who were once part of the Duterte Cabinet.

“The national government will not hesitate to use its authority and forces to quell and stop any and all attempts to dismember the Republic,” Año warned on February 4. “Any attempt to secede any part of the Philippines will be met by the government with resolute force.”

President Marcos has also urged the proponents of a separate Mindanao to drop their advocacy.

“The new call for a separate Mindanao is doomed to fail, for it is anchored on a false premise, not to mention a sheer constitutional travesty,” he said on February 8 .

The politics of secession

The 1987 constitution does not entertain the concept of secession..

Panelo has rebuked Marcos, insisting that espousing the idea of secession is part of freedom of speech guaranteed by the 1987 Constitution.

“Secession is anchored on the principle that the people have the right to self-determination. They have the right to choose the kind of government they want, to choose the officials who will govern them and to determine their future,” Panelo said on February 11.

Still, the present charter does not entertain secessionist movements.

The first two articles of the Constitution put a premium on the country’s territorial integrity, saying that the Armed Forces of the Philippines must work “to secure the sovereignty of the State and the integrity of the national territory.”

Marcos has already made clear how he interprets the Constitution in light of secession calls.

“Our Constitution calls for a united, undivided country. It calls for an eternal cohesion. For this reason, unlike other Constitutions, there is nothing in ours that allows the breaking up of this union, such as an exit provision,” he said.

Duterte does not have the support of the Bangsamoro leadership nor key political figures from Mindanao.

There were calls in the past for Mindanao to separate from the rest of the Philippines, but “they never really got mainstream,” according to former presidential adviser on the peace process Ging Deles.

“What became a real move towards independence or secession was the Bangsamoro,” she said in Rappler’s panel discussion on Mindanao independence on February 9. “It was not a call for an independent Mindanao. It was a call of a specific area that was united in teachers of culture, history, and tradition that were being neglected.”

Duterte, however, cannot convince even the leadership of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) to join his cause.

“As chief minister of the Bangsamoro government, I stand firmly on adhering to the faithful implementation of the provisions of the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro towards the right to self-determination,” Bangsamoro Chief Minister Ahod Ebrahim said on February 2, referring to the landmark 2014 peace deal that resulted in Islamic separatists letting go of their firearms.

Other leaders from Mindanao have opposed Duterte’s call, including Senate President Juan Miguel Zubiri, Senate Minority Leader Aquilino “Koko” Pimentel III, and House Majority Leader Mannix Dalipe.

It appears that advocates of Mindanao secession have yet to fully organize themselves.

Weeks since Duterte’s statement, there are little indications that would suggest there is truly a “movement” or well-oiled machine to concretize the idea. A signature campaign has also not begun.

When asked about the blueprint of their ambition, Alvarez acknowledged that they are still at the first step of what he said is a three-stage process.

“First is awareness. The people in Mindanao need to know about this movement seeking to separate Mindanao from the rest of the Philippines. The next stage would be acceptance. We have to answer the questions of what and why so the public will understand. After that, we will wait for the right timing, the ‘when,'” he said during Rappler’s panel discussion.

Alvarez insisted their call for Mindanao secession is not personal, but former presidential political adviser Ronald Llamas disagreed.

Llamas suspects that the proposal ultimately stems from the long shadow cast by the possibility of the Marcos administration allowing the International Criminal Court to arrest Duterte over his bloody drug war that resulted in thousands dead.

“My belief is that the call for secession is basically personal. It’s the fear of the ICC,” he said. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

Please abide by Rappler's commenting guidelines .

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.

How does this make you feel?

Related Topics

Dwight de Leon

Recommended stories, {{ item.sitename }}, {{ item.title }}, ferdinand marcos jr., [newsstand] the marcoses’ three-body problem.

![war in mindanao essay [Newsstand] The Marcoses’ three-body problem](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-marcoses-3-body-problem.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=451px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

Marcos vows countermeasures vs China’s ‘dangerous attacks’

Marcos, First Lady Liza have made full recovery from flu-like symptoms, says Palace

[Rappler’s Best] No rest for the wicked

![war in mindanao essay [Rappler’s Best] No rest for the wicked](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/newsletter-2.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=402px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

With PAREX uncertain, advocates ask Marcos: Consult communities for Pasig River revival

International Criminal Court

Explainer: what happens to arnie teves after arrest in timor-leste.

In Germany, Marcos touts his supposed about-face from Duterte’s bloody drug war

FACT CHECK: ICC probe ongoing, no ‘guilty’ verdict issued vs Duterte

ICC issues arrest warrants against top Russian commanders Kobylash and Sokolov

Newsbreak Chats: Should Rodrigo Duterte be afraid of the Int’l Criminal Court?

Pantaleon Alvarez

Mindanao independence: duterte’s ‘joke’ that just didn’t fly.

Rappler Talk: Pantaleon Alvarez on charter change push under Marcos gov’t

CAMPAIGN TRAIL: Now allied with Davao del Norte’s Alvarez, Robredo returns to Tagum City

WATCH: Alvarez confident in Robredo’s ‘slow burn’ campaign momentum

Checking your Rappler+ subscription...

Upgrade to Rappler+ for exclusive content and unlimited access.

Why is it important to subscribe? Learn more

You are subscribed to Rappler+

The War at Stanford

I didn’t know that college would be a factory of unreason.

Listen to this article

Produced by ElevenLabs and News Over Audio (NOA) using AI narration.

This article was featured in the One Story to Read Today newsletter. Sign up for it here .

ne of the section leaders for my computer-science class, Hamza El Boudali, believes that President Joe Biden should be killed. “I’m not calling for a civilian to do it, but I think a military should,” the 23-year-old Stanford University student told a small group of protesters last month. “I’d be happy if Biden was dead.” He thinks that Stanford is complicit in what he calls the genocide of Palestinians, and that Biden is not only complicit but responsible for it. “I’m not calling for a vigilante to do it,” he later clarified, “but I’m saying he is guilty of mass murder and should be treated in the same way that a terrorist with darker skin would be (and we all know terrorists with dark skin are typically bombed and drone striked by American planes).” El Boudali has also said that he believes that Hamas’s October 7 attack was a justifiable act of resistance, and that he would actually prefer Hamas rule America in place of its current government (though he clarified later that he “doesn’t mean Hamas is perfect”). When you ask him what his cause is, he answers: “Peace.”

I switched to a different computer-science section.

Israel is 7,500 miles away from Stanford’s campus, where I am a sophomore. But the Hamas invasion and the Israeli counterinvasion have fractured my university, a place typically less focused on geopolitics than on venture-capital funding for the latest dorm-based tech start-up. Few students would call for Biden’s head—I think—but many of the same young people who say they want peace in Gaza don’t seem to realize that they are in fact advocating for violence. Extremism has swept through classrooms and dorms, and it is becoming normal for students to be harassed and intimidated for their faith, heritage, or appearance—they have been called perpetrators of genocide for wearing kippahs, and accused of supporting terrorism for wearing keffiyehs. The extremism and anti-Semitism at Ivy League universities on the East Coast have attracted so much media and congressional attention that two Ivy presidents have lost their jobs. But few people seem to have noticed the culture war that has taken over our California campus.

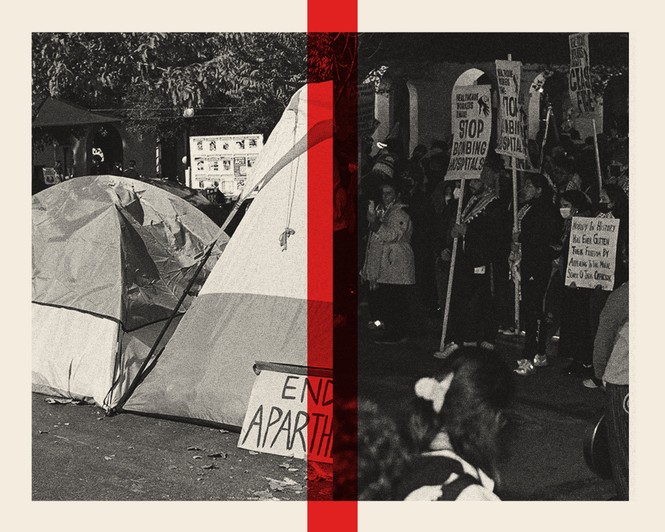

For four months, two rival groups of protesters, separated by a narrow bike path, faced off on Stanford’s palm-covered grounds. The “Sit-In to Stop Genocide” encampment was erected by students in mid-October, even before Israeli troops had crossed into Gaza, to demand that the university divest from Israel and condemn its behavior. Posters were hung equating Hamas with Ukraine and Nelson Mandela. Across from the sit-in, a rival group of pro-Israel students eventually set up the “Blue and White Tent” to provide, as one activist put it, a “safe space” to “be a proud Jew on campus.” Soon it became the center of its own cluster of tents, with photos of Hamas’s victims sitting opposite the rubble-ridden images of Gaza and a long (and incomplete) list of the names of slain Palestinians displayed by the students at the sit-in.

Some days the dueling encampments would host only a few people each, but on a sunny weekday afternoon, there could be dozens. Most of the time, the groups tolerated each other. But not always. Students on both sides were reportedly spit on and yelled at, and had their belongings destroyed. (The perpetrators in many cases seemed to be adults who weren’t affiliated with Stanford, a security guard told me.) The university put in place round-the-clock security, but when something actually happened, no one quite knew what to do.

Conor Friedersdorf: How October 7 changed America’s free speech culture