Write an essay in French

Beyond the fact that writing an essay in French can be a good practice to improve your writing, you may also be asked to write one during your schooling. So, it is important to study the topic of French essay writing and get some useful tips..

» Tips and tricks for your French essay » The structure of a French essay » Sample French Essay

Tips and tricks for your French essay

When writing a French essay for school, you should always use a structured approach and good French skills to present your arguments in a focused way. Beyond French skills, there are also important formal requirements for a successful French essay. We will come back to this in detail later. First, you will find some useful tips and tricks that will help you write more compelling and better French essays in the future.

- Have a clear thesis and structure

- Do sufficient research and use reliable sources

- Use examples and arguments to support your thesis

- Avoid plagiarism and cite correctly

- Always check structure, grammar and spelling

When you write your essay at school or university, you need to make sure that the general structure of your essay, the presentation of the arguments and, above all, your French language skills play a role in the mark you will get. This is why you should definitely take a closer look at the structure of an essay as well as the most important grammar rules and formulations for French essays.

The structure of a French essay

In an essay, you deal at length and in detail with a usually given topic. When you write an essay in French, you must follow a certain structure. Below we show you what this structure looks like and give you some tips for writing the most important parts of your essay.

The Introduction

The introduction prepares the main body of your essay. You think of a meaningful title for your essay, you describe your thesis or your question, you give general information on the subject and you prepare your argument by giving an overview of your most important arguments.

Below are examples and phrases that you can use to write the introduction to your essay in French.

The title should be meaningful, concise and reflect the content of the essay.

Introductory paragraph

The first paragraph of your French essay should briefly introduce the topic and engage the reader. Here are some examples to help you write your essay:

Proposal or question

The central proposition or question of your French essay should be a clear and concise definition of the purpose of the essay. Use these examples to get a clearer idea of how to write theses in French:

Overview of Arguments and Structure

At the end of your introduction, describe the structure of the main part of your essay (your outline) and outline your argument. Here are some French expressions that will certainly help you write your essay:

The body of your essay

The main part of your French essay deals with the given topic in detail. The subject is studied from all angles. The main body of your essay follows a thread of argument and discusses in detail the main arguments of your thesis previously made in the introduction.

In the body of the text, you should discuss the subject of your essay in clear and concise language. To achieve this, we give you some wording aids as well as vocabulary and phrases that you can use to write your essay in French.

Formulation tools:

French vocabulary for essays.

In the conclusion of your French essay, you address the thesis of your essay, summarize the main points of your discussion in the main body, and draw a conclusion. On the basis of the arguments and the resulting conclusions, you formulate in the conclusion of your dissertation final thoughts and suggestions for the future. It is important that you do not add new information or new arguments. This should only be done in the body of your text.

Here are some wording guides to help you write your essay in French:

Sample French Essay

Les avantages des voyages linguistiques

Malgré les difficultés potentielles, les voyages linguistiques offrent aux apprenants une occasion unique d'améliorer leurs compétences linguistiques et de découvrir de nouvelles cultures, ce qui en fait un investissement précieux pour leur développement personnel et académique.

Les séjours linguistiques sont des voyages organisés dans le but d'améliorer les compétences linguistiques des participants. Ces voyages peuvent se dérouler dans le pays ou à l'étranger et durer d'un week-end à plusieurs semaines. L'un des principaux avantages des séjours linguistiques est l'immersion. Entourés de locuteurs natifs, les apprenants sont contraints de pratiquer et d'améliorer leurs compétences linguistiques dans des situations réelles.Il s'agit d'une méthode d'apprentissage beaucoup plus efficace que le simple fait d'étudier une langue dans une salle de classe.

Un autre avantage des séjours linguistiques est l'expérience culturelle. Voyager dans un nouveau pays permet aux apprenants de découvrir de nouvelles coutumes, traditions et modes de vie, et de se familiariser avec l'histoire et la culture du pays. Cela enrichit non seulement l'expérience d'apprentissage de la langue, mais contribue également à élargir les horizons et à accroître la sensibilisation culturelle.

Cependant, les séjours linguistiques peuvent également présenter des inconvénients. Par exemple, le coût du voyage et de l'hébergement peut être élevé, en particulier pour les séjours de longue durée. En outre, les apprenants peuvent être confrontés à la barrière de la langue ou à un choc culturel, ce qui peut être difficile à surmonter. Le coût et les difficultés potentielles des séjours linguistiques peuvent sembler décourageants, mais ils offrent des avantages précieux en termes d'épanouissement personnel et scolaire.

Les compétences linguistiques et les connaissances culturelles acquises peuvent déboucher sur de nouvelles opportunités d'emploi et améliorer la communication dans un cadre professionnel. Les bourses et les aides financières rendent les séjours linguistiques plus accessibles. Le fait d'être confronté à une barrière linguistique ou à un choc culturel peut également être l'occasion d'un développement personnel. Ces avantages l'emportent largement sur les inconvénients et font des séjours linguistiques un investissement qui en vaut la peine.

En conclusion, malgré les difficultés potentielles, les séjours linguistiques offrent aux apprenants une occasion unique d'améliorer leurs compétences linguistiques et de découvrir de nouvelles cultures, ce qui en fait un investissement précieux pour le développement personnel et académique. Qu'il s'agisse d'un débutant ou d'un apprenant avancé, un voyage linguistique est une expérience à ne pas manquer.

Improve your writing style in French

Learn French with us. We will help you improve your writing skills.

Improve your French with Sprachcaffe

A Year abroad for high school students

Spend a unique school year abroad

Online French courses

Learn French from the comfort of your own home with an online course

Learn French on a language trip

Learn French in a French-speaking country

How to Write an Excellent French Essay (Resources Included)

Tips to write an excellent french essay.

Writing essays is challenging enough, but when you are asked to write a French essay, you are not only being asked to write in a foreign language, but to follow the conventions of another linguistic and literary tradition. Like essay-writing in any language, the essential part of writing a French essay is to convey your thoughts and observations on a certain topic in a clear and concise manner. French essays do come out of a certain tradition that is part of the training of all students who attend school in France – or at least secondary school – and when you are a French essay, it is important to be aware of this tradition.

The French philosopher Michel de Montaigne is credited with popularizing the essay form as a literary genre. His work, Essais, first published in 1580, and undergoing several subsequent publications before his death in 1592, covers a wide breadth of topics, ranging from “amitié” to “philosopher c’est apprendre à mourir”, and includes many literary references, as well as personal anecdotes. The name for this genre, essai, is the nominal form of the verb essayer, “to attempt”. We have an archaic English verb essay, meaning the same thing. The limerick that includes the phrase, “... when she essayed to drink lemonade ...” indicates an attempt to drink a beverage and has nothing to do with writing about it. But the writing form does illustrate an attempt to describe a topic in depth with the purpose of developing new insights on a particular text or corpus.

French instructors are very specific about what they would like when they ask for an essay, meaning that they will probably specify whether they would like an explication de texte, commentaire composé, or dissertation. That last essay form should not be confused with the document completed for a doctorate in anglophone countries – this is called a thèse in French, by the way. There are different formats for each of these types of essay, and different objectives for each written form.

Types of Essay

1. l’explication de texte.

An explication de texte is a type of essay for which you complete a close reading. It is usually written about a poem or a short passage within a larger work. This close reading will elucidate different themes and stylistic devices within the text. When you are completing an explication de texte, make sure to follow the structure of the text as you complete a close examination of its form and content. The format for an explication de texte consists of:

i. An introduction, in which you situate the text within its genre and historical context. This is where you can point out to your readers the general themes of the text, its form, the trajectory of your reading, and your approach to the text.

ii. The body, in which you develop your ideas, following the structure of the text. Make sure you know all of the meanings of the words used, especially the key terms that point to the themes addressed by the author. It is a good idea to look words up in the dictionary to find out any second, third, and fourth meanings that could add to the themes and forms you describe. Like a student taking an oral examination based on this type of essay writing, you will be expected to have solid knowledge of the vocabulary and grammatical structures that appear in the text. Often the significance of the language used unfolds as you explain the different components of theme, style, and composition.

iii. A conclusion, in which you sum up the general meaning of the text and the significance of the figures and forms being used. You should also give the implications of what is being addressed, and the relevance of these within a larger literary, historical, or philosophical context.

NB: If you are writing about a poem, include observations on the verse, rhyme schemes, and meter. It is a good idea to refer to a reference work on versification. If you are writing about a philosophical work, be familiar with philosophical references and definitions of concepts.

Caveat: Refrain from paraphrasing. Instead show through careful analysis of theme, style, and composition the way in which the main ideas of the text are conveyed.

2. Le commentaire composé

A commentaire composé is a methodologically codified commentary that focuses on themes in a particular text. This type of essay develops different areas of reflection through analytical argument. Such argumentation should clarify the reading that you are approaching by presenting components of the text from different perspectives. In contrast to the explication de texte, it is organized thematically rather than following the structure of the text to which it refers. The format for a commentaire composé consists of:

i. An introduction, in which you present the question you have come up with, often in relation to a prompt commenting on a thematic or stylistic aspect of the text, such as “Montrez en quoi ce texte évoque l’amour courtois” or “Qu’apporte l’absence de la ponctuation dans ce texte ?” In this section, you will be expected to delineate your approach to the text and illustrate the trajectory of your ideas so that your readers will have a clear idea of the direction these ideas will take.

ii. A tripartite body, in which you explore the question you have come up with, citing specific examples in the text that are especially pertinent to the areas of reflection you wish to explore. These citations should be explained and connected to the broad themes of your commentary, all the while providing details that draw the readers’ attention to your areas of inquiry. These different areas of inquiry may initially seem disparate or even contradictory, but eventually come together to form a harmonious reading that addresses different aspects of the text. The more obvious characteristics of the text should illuminate its subtler aspects, which allows for acute insight into the question that you are in the process of exploring.

iii. A conclusion, in which you evaluate your reading and synthesize its different areas of inquiry. This is where you may include your own opinions, but make sure that the preceding sections of your commentaire remain analytical and supported by evidence that you find in the text.

NB: Looking at verb tenses, figures of speech, and other aspects that contribute to the form of the text will help situate your reader, as will commenting on the register of language, whether this language is ornate, plain, reflects a style soutenu, or less formal patterns of speech.

Caveat: Quotations do not replace observations or comments on the text. Explain your quotations and situate them well within your own text.

3. La dissertation

The dissertation is a personal, organized, and methodical reflection on a precise question that refers to a corpus of writing. Referring to this corpus, you may be asked questions along the lines of “Que pensez-vous de l’équivalence entre l’amour et la chanson exprimée dans ces textes ?” or “Est-ce que la sagesse et la folie ont les mêmes sources?” This type of essay allows for an exploration of a question through knowledge of a corpus as well as through an individual’s cultural knowledge. The format for a dissertation consists of:

i. An introduction, in which you present the topic addressed, the significance of your argument, and the trajectory of your ideas.

ii. The body which, like a commentaire composé, consists of a tripartite development of your argument. This can follow any one of the following structures: a dialectical schema, organized into thèse, antithèse, and synthèse – an argument, its counter-argument, and its rebuttal; an analytical schema, consisting of the description of a situation, an analysis of its causes, and commentary on its consequences; a thematic schema, which consists of a reflection on a topic which you proceed to examine from different angles in an orderly fashion.

iii. A conclusion, in which you address the different ways in which you have approached the question at hand and how this deepens your insights, while placing the question within a broader context that shows room for expansion. The conclusion can open up the topic addressed to show its placement within a literary movement, or in opposition to another literary movement that follows it, for example.

NB: Approach the question at hand with as few preconceptions as possible. If you are writing on a quotation, gather all of your knowledge about its author, the work in which it appears, and the body of literature with which it is associated.

Caveat: Even for a personal reflection, such as a dissertation, avoid using the first person pronoun je. Nous or on are preferable. It is advisable not to switch from one to the other, though.

For each of these essay forms, it is a good idea to make an outline to which you can refer as you write. As your writing progresses, things may shift a bit, but having a structure on which you can rely as you gather your various ideas and information into a coherent argument provides solid foundation for a clear and well-developed essay. This also facilitates smooth transitions from one section of your essay to the next.

During your reading, you may encounter a problem, a contradiction, or a surprising turn of phrase that is difficult to figure out. Such moments in a text give you the opportunity to delve into the unique characteristics of the text or corpus to which you are referring, to propose different solutions to the problems you encounter, and to describe their significance within a larger literary, philosophical, and historical context. Essay writing allows you to become more familiar with French works, with their cultural significance, and with the French language. You can refer to the following resources to guide you in this endeavor:

Auffret, Serge et Hélène. Le commentaire composé. Paris: Hachette, 1991. Dufau, Micheline et Ellen D'Alelio. Découverte du poème: Introduction à l'explication de textes. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1967. Grammont, Maurice. Petit traité de versification française. Paris: A. Colin, 2015. Huisman, Denis et L. R. Plazolles. L’art de la dissertation littéraire : du baccalauréat au C.A.P.E.S. Paris : Société d’édition d’enseignement supérieur, 1965.

The French newspaper Le Monde also has good articles on these essay forms that prepare French students for the baccalauréat exam: CLICK HERE

This is also a website with thorough information on essay writing techniques that prepare students for the baccalauréat exam: CLICK HERE

In addition, the University of Adelaide has tips for general essay writing in French: CLICK HERE

🇫🇷 Looking for More French Resources?

Train with Glossika and get comfortable talking in French. The more you listen and speak, the better and more fluent you will be.

Glossika uses syntax to help you internalize grammatical structures and you can build up your French vocabulary along with way. You'll also learn to communicate in real-life situations, and achieve fluency by training your speaking and listening!

Sign up on Glossika and try Glossika for free:

You May Also Like:

- 10 Great Tips to Prepare to Study in France

- How to Maintain French and Continue Learning by Yourself

- Differences Between Spoken French and Written French

Subscribe to The Glossika Blog

Get the latest posts delivered right to your inbox

Stay up to date! Get all the latest & greatest posts delivered straight to your inbox

Published on October 6th, 2023 | by Adrian Lomezzo

How to Write an Essay in French Without Giving Yourself Away as a Foreigner

Image source: https://www.pexels.com/photo/close-up-shot-of-a-quote-on-a-paper-5425603/

Bienvenue! Do you dream of unleashing your inner French literary genius, but worry that your writing might inadvertently reveal your foreign roots? Fret not, mes amis, as we have the ultimate guide to help you master the art of essay writing en Français!

Within these pages, we’ll navigate the intricate waters of linguistic nuances, cultural subtleties, and grammatical finesse, allowing you to exude the aura of a native French speaker effortlessly. Many students like you have embarked on this journey, seeking academic assistance from platforms like https://paperwritten.com/ to conquer their writing pursuits.

From crafting a compelling introduction to fashioning impeccable conclusions, we’ll unveil the secrets that will leave your professors applauding your newfound linguistic prowess. So, bid adieu to those awkward linguistic giveaways and embrace the sheer elegance of French expression – all while keeping your foreign identity beautifully concealed! Let’s embark on this adventure together and unlock the true essence of writing like a native French virtuoso.

1. Mastering French Grammar and Vocabulary: Building a Strong Foundation

To create a compelling French essay, it’s essential to lay a solid groundwork. Ensure that your French grammar is accurate and that you possess a rich vocabulary. Avoid relying on online translators, as they may yield awkward or incorrect sentences. Instead, embrace reputable dictionaries and language resources to enhance your language skills effectively.

2. Mimic Sentence Structures: The Art of Authentic Expression

To truly immerse yourself in the French language, observe and mimic the sentence structures used by native speakers. Analyzing essays written by experienced writers can prove invaluable in grasping the authentic style required to compose a captivating essay.

3. Use Transition Words: Crafting a Smooth Flow of Ideas

In French essays, the use of transition words and phrases plays a pivotal role in connecting ideas seamlessly. Incorporate expressions like “de plus,” “en outre,” “en conclusion,” “tout d’abord,” and “par conséquent” to add coherence and elegance to your writing.

4. Embrace French Idioms and Expressions: Unveiling Cultural Fluency

Demonstrate a deeper understanding of the French language and culture by incorporating idioms and expressions where appropriate. However, remember to use them sparingly to avoid overwhelming your essay.

5. Pay Attention to Formality: Striking the Right Tone

Tailor the formality of your writing to suit the context of your essay. Whether you are crafting an academic piece or a more personal creation, be mindful of your choice of vocabulary and sentence structures to match the required tone.

6. Research Cultural References: The Power of In-depth Knowledge

If your essay touches upon French culture, history, or literature, extensive research is key. Delve into your subjects to avoid mistakes and showcase your genuine interest in the matter at hand.

7. Avoid Direct Translations: Let French Be French

To avoid awkward phrasing, strive to think in French rather than translating directly from your native language. This will lead to a more natural and eloquent essay.

8. Practice Writing Regularly: The Path to Proficiency

Mastering the art of French writing requires regular practice. Embrace writing in French frequently to grow more comfortable with the language and refine your unique writing style.

9. Read French Literature: A Gateway to Inspiration

Explore the world of French literature to expose yourself to diverse writing styles. This practice will deepen your understanding of the language and immerse you further in French culture and history.

10. Connect with French Culture: Bridges of Cultural Resonance

Incorporate cultural references that resonate with French readers, such as art, cuisine, festivals, historical figures, or social customs. Authenticity is key, so avoid relying on stereotypes.

11. Use a French Thesaurus: Expanding Your Linguistic Palette

Discovering new contextually appropriate words can elevate your writing. Embrace a French thesaurus to find synonyms that may not be apparent through direct translations.

12. Master French Punctuation: The Finishing Touch

Take care to use correct French punctuation marks, such as guillemets (« ») for quotes and proper accent marks. These subtle details add a professional touch to your essay.

13. Practice French Rhetorical Devices: Crafting Eloquent Prose

Experiment with rhetorical devices like parallelism, repetition, and antithesis to lend depth and sophistication to your writing.

14. Pay Attention to Word Order: Unlocking French Sentence Structure

French boasts a unique sentence structure distinct from English. Dive into the intricacies of subject-verb-object order and grasp the art of organizing sentences to sidestep common foreign mistakes. Embracing this essential aspect will elevate your writing to a truly native level.

15. Use French Idiomatic Expressions: Infuse Cultural Flair

Enrich your prose with the colorful tapestry of French idioms, reflecting the vibrant essence of the culture. Yet, a word of caution – wield them with finesse, for the strategic placement of an idiom can imbue your essay with unparalleled flair and authenticity.

16. Master Pronouns and Agreement: The Dance of Language

The dance of pronouns, nouns, and adjectives requires your keen attention. Like a skilled performer, ensure their seamless alignment to avoid inadvertently revealing your non-native status. Mastering this harmony is key to writing like a true Francophone.

17. Understand Subtle Connotations: Unveiling Linguistic Shades

Delve into the labyrinth of French words, where subtle connotations diverge from their English counterparts. Familiarize yourself with these delicate nuances, for it is in their mastery that your writing shall find refinement.

18. Study Formal and Informal Registers: Tailoring Language to Purpose

Akin to selecting the perfect outfit for each occasion, comprehend the art of using formal and informal language. Consider your essay’s purpose and audience, and with this knowledge, enhance your authenticity, seamlessly aligning with the appropriate linguistic register.

19. Practice Dialogue Writing: Conversing with Eloquence

Embark on the journey of dialogue writing to enrich your linguistic repertoire. As you hone your conversational skills, watch as authenticity gracefully weaves itself into your written work, enchanting readers with its charm.

20. Seek Feedback: A Second Set of Eyes

To refine your essay further, seek the guidance of a native French speaker or language tutor from the best cheap essay writing services . Their valuable feedback can uncover any language or cultural mistakes you may have made, allowing you to make necessary improvements.

Equip yourself with these priceless tips and set forth on your quest to master the art of French writing. Embrace the language’s allure, immerse in its rich culture, and watch your words flow with grace and poise. À la plume! Let the pen become your ally in crafting captivating prose that echoes with authenticity and charm.

Header Photo Credit by George Milton: https://www.pexels.com/photo/smiling-woman-in-eyeglasses-with-books-7034478/

About the Author

Adrian Lomezzo is a content writer and likes to write about technology and education. He understands the concern of parents due to the evolving technology and researches deeply in that area. When he is not researching, he buries himself in books along with his favorite cup of hot chocolate.

Related Posts

Beyond Shakespeare: Expanding Horizons with London’s Diverse Theatre Scene →

Three French authors from San Diego present their new books →

Martine Couralet-Laing reveals behind the scenes of the city of angels in DreamLAnd →

Don’t Miss Laurent Ruquier’s “Un Couple Magique” in Paris This Month! →

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Welcome to French Quarter Magazine (FQM) – your passport to a journey through France, the United States and beyond!

French Quarter Magazine is a dynamic bilingual publication, based in Las Vegas, that celebrates the finest in art, culture, entertainment, lifestyle, fashion, food, travel, sports and history. Whether you're longing for a taste of Parisian elegance or the vibrancy of American culture, we've got you covered.

Our mission is to create a link and to bridge the gap between the United States and France by promoting exchanges and offering a unique reading experience through our bilingual publication. From the charming streets of Paris to the bustling avenues of New York City, our articles provide a captivating exploration of diverse cultural landscapes. Written by our dedicated team of contributors from around the world, they cover everything from the latest places to visit or stay, to new spectacles and exhibitions, to the opening of exciting restaurants or stores, fashion trends, and the nuanced history of French-American relations.

With a focus on women empowering women and excellence, we showcase individuals who make a positive impact in our communities. Through cultural events, conferences, and engaging content, we strive to enrich understanding of history, culture, and the arts, while preserving and transmitting valuable skills and knowledge.

At French Quarter Magazine, we cherish culture as a precious and diverse treasure that should be celebrated. That's why we provide a platform for individuals and businesses with interests in both countries to connect, network, and engage. Through our engaging content and cultural events, we strive to foster understanding and appreciation of the unique qualities of each culture, while also highlighting their shared values.

So why not join us on a journey of discovery? Whether you're seeking inspiration or information, French Quarter Magazine is the perfect publication for you.

Step into a world of lifestyle, entertainment, cultural exchanges with French Quarter Magazine! Subscribe today to receive our weekly newsletters and special offers, and step into a world of endless possibilities.

PROMOTE MY BUSINESS

Donate we need your help, become an ambassador, virtual and in-person events with fqm, your opinion matters , learning french, recent posts.

RECENT COMMENTS

Merci pour votre commentaire intéressant, Annick ! Désolée pour la réponse tardive. Nous avons dû restructurer notre équipe. Nous sommes…

Thank you for your continued support and for being a regular visitor to our website, Cameron! Sorry for the late…

Bonjour! Nous sommes ravis que vous ayez apprécié l'article ! Désolée pour la réponse très tardive. Nous avons dû restructurer…

Thank you for sharing that interesting piece of information, Mike! As for "Alors on Danse" by Stromae, while it didn't…

Thank you so much, Jaya! I'm delighted that you enjoyed the article and found it informative. Exploring the cultural differences…

©2023 French Quarter Magazine

- Sponsorships, Partnerships and Advertising

- Privacy Policies

- Art & Culture

- Travel & Sports

What is the translation of "essay" in French?

"essay" in french, essay {v.t.}.

- volume_up disserter

essay {noun}

- volume_up thèse

essay question {noun} [example]

- volume_up sujet de dissertation

essay subject [example]

Essay test {noun} [example].

- volume_up épreuve écrite

"essayer" in English

- volume_up attempt

- volume_up run trials on

- volume_up tried

Translations

Essay [ essayed|essayed ] {transitive verb}.

- open_in_new Link to source

- warning Request revision

essayer [ essayant|essayé ] {verb}

Essayer [ essayant|essayé ] {transitive verb}, essayé {past participle}, essayée {past participle}, essayés {past participle}, context sentences, english french contextual examples of "essay" in french.

These sentences come from external sources and may not be accurate. bab.la is not responsible for their content.

Monolingual examples

English how to use "essay" in a sentence, english how to use "essay question" in a sentence, english how to use "essay subject" in a sentence, english how to use "essay test" in a sentence, collocations, "admission essay" in french.

- volume_up essai d'admission

"analytical essay" in French

- volume_up essai analytique

"essay address" in French

- volume_up adresse de dissertation

- volume_up adresse d'essai

Synonyms (English) for "essay":

Synonyms (french) for "essayer":.

- entreprendre

pronunciation

- espresso cup

- espresso drinks

- espresso machine

- espresso maker

- espresso powder

- espresso with milk

- esprit de corps

- esq. (esquire)

- essay address

- essay assignment

- essay competition

- essay contest

- essay describe

- essay discuss

- essay mills

- essay portion

- essay publish

- essay question

Do you want to translate into other languages? Have a look at our Japanese-English dictionary .

Social Login

Learn How to Write in French Easily

- Everything About

- The alphabet

- Funny phrases

- Common words

- Untranslateable Words

- Reading Hacks

- Writing Tips

- Pronunciation

- Telling time

- Learn FASTER

- More resources

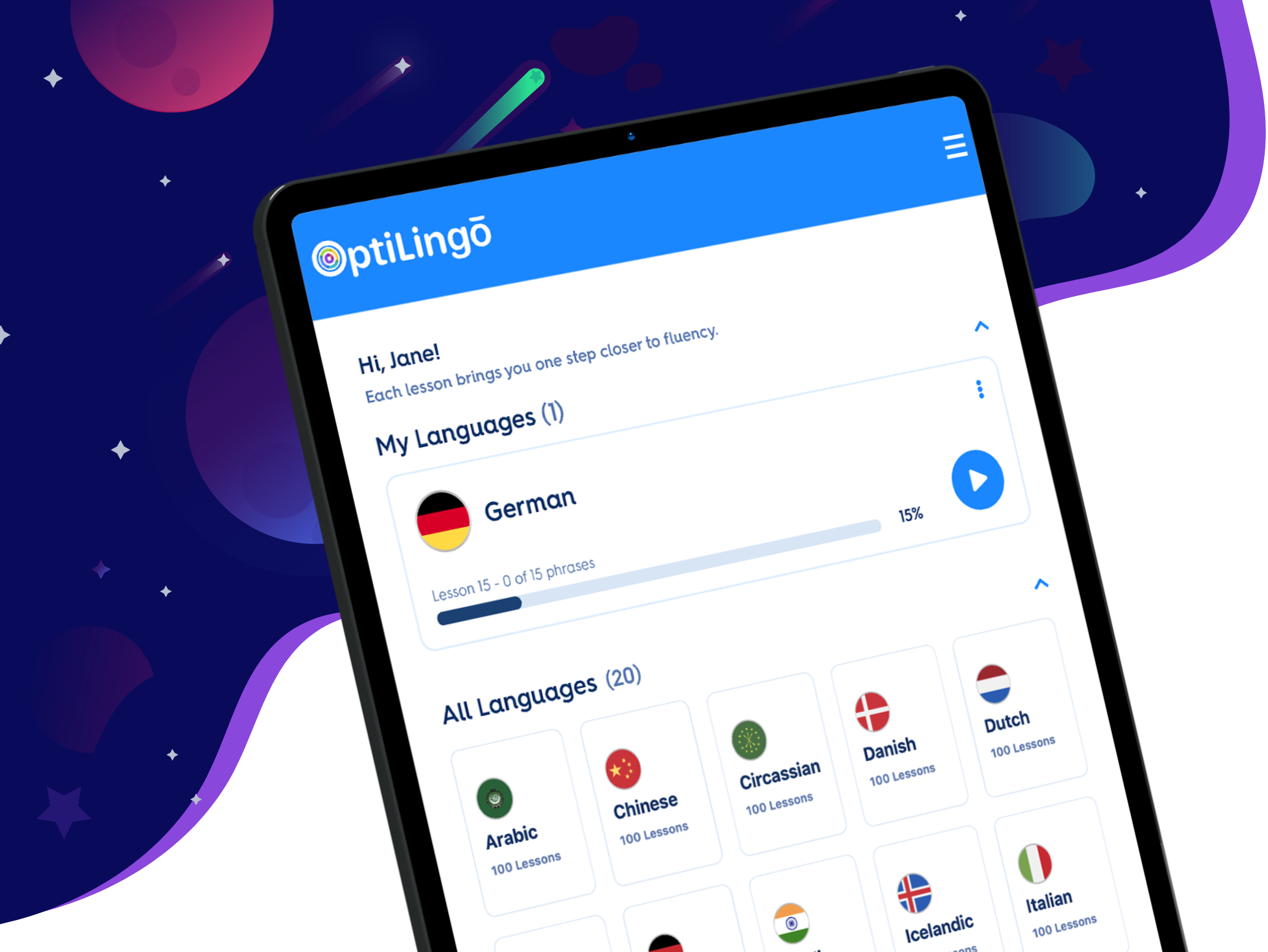

By OptiLingo • 9 minute read

Improve Your Written French Today

Whether you want to pen a love letter or submit an essay in France, you need to know how to write in French. Luckily, learning how to write in French is fairly straightforward. Since French uses the Latin Alphabet, you’re already ahead of the game. Improve your writing in French fast with these easy steps.

The Basics of French Writing for Beginners

When it comes to French writing, it’s a little different than speaking French. But, if you know how to read French well, you shouldn’t have a lot of problems.

Before you read the 8 easy steps of learning to write in French, there’s one important factor in mastering French writing: practice. The only way you can truly improve your French writing skills is with a lot of practice . Make sure you write a little bit in French every day. Soon, you’ll find that writing in French is like second nature.

1. Watch Out for French Spelling

One of the biggest obstacles that throws French learners off is spelling. Unfortunately, those silent letters that you don’t pronounce are very much there in writing. Be careful how you spell certain complicated words. You need to master all parts of French grammar to write French correctly.

2. Genders Influence Grammar in French

You may already know that nouns have genders in French. They can either be masculine or feminine. And depending on the gender, different parts of a French sentence need to be conjugated.

- articles : French articles need to be conjugated to reflect the gender and the number of the noun. These can be ‘le’, ‘la’, ‘l”, and ‘les’ for definite articles, and ‘un’ and ‘une’ for indefinite articles.

- pronouns : Pronouns in French are the words that replace the name of the subject in a sentence. ‘He’, ‘she’, and ‘them’ are some examples of pronouns in English. In French, you need to use different forms of pronouns depending on the gender of the subject.

- adjectives : When you’re describing a noun, you use an adjective. And since the noun is the only reason the adjective’s there in the sentence, you need to make the adjective fit the noun in French. There are various ways to conjugate French adjectives depending on the gender and the number of the noun, so make sure you brush up on that knowledge before you write in French.

3. Careful with French Accent Marks

French accent marks also don’t do us any favors. While they’re extremely useful when it comes to French pronunciation, their writing isn’t as straightforward. Try to associate the sound with the written French word. There are only 5 accent marks in French. One is the cedilla (ç), which only works with the letter “c”, and another is the acute accent (é), which only sits on top of the letter “e”. So in practice, there are only 3 different kinds of accents you should look out for in French.

4. Follow the French Sentence Structures

English and French sentence structures are similar in many ways. Both follow the SVO (subject-verb-object) structure, which makes writing in French much easier. And just like in English, the French sentence structure is also flexible. You can switch the words around to emphasize a part of a sentence, but still have the same meaning.

- Tomorrow , I’m going to work. Demain je vais travailler. I’m going to work tomorrow . Je vais travailler demain .

The most important part of the first sentence is the time the speaker goes to work. The second sentence focuses on the subject, the speaker instead. Still, both sentences convey the same meaning of going to work.

If you want to ask a question in French, you can do so by putting a question word at the beginning of the sentence. Common question words are:

- How Comment

- What Que / Qu’est-ce que queue

- What kind Quel genre

- When Quand

- Why Pourquoi

You can also ask a question by switching the order of the verb and the pronoun around, and connecting them with a hyphen:

- Do you speak English? Parlez-vous anglais ?

It’s important to remember these basic rules of French sentence structure before you start writing in French. If you want to learn how to write in French effectively, practice these 4 steps a lot.

Psst! Did you know we have a language learning app?

- It teaches you useful words and phrases.

- Presented in a natural, everyday context.

- Spaced out over time, so you absorb your new language organically.

- It’s kind of like learning the words to your new favorite song!

You’re only one click away!

How to Write in French for Intermediate Students

If you’re an intermediate French learner you’re familiar with basic French grammar, and you’re confident in writing in French. But, there’s always room to improve. Once you know the basic steps of how to write in French, it’s time to make your writing even better. You can start paying attention to style, flow, and structure. The tips below will benefit your French writing practice.

5. Try Nominalization

This useful technique will make your sentences better. Nominalization means that you make nouns in the sentence more dominant. While in English, the dominant words are verbs, in French, you can write with the focus of the noun instead, making them more meaningful. Here’s an example to demonstrate.

- Normal sentence: The ice cream is cold. – La glace est froide.

- Nominalized sentence: The ice cream is cold. – La glace, c’est droid.

6. Use French Conjunctions

Conjunctions are the tools to write complex French sentences. Without them, you’re limited to simple and boring sentence structures. As an intermediate student, you can start connecting two equal or unequal sentences to make an even more interesting phrase. Here are the different kinds of French conjunctions you can use to write better in French:

Coordinating Conjunctions:

You use these kinds of conjunctions to connect two equal sentences. The most common coordinating conjunctions in French are:

Subordinating Conjunctions:

If one of the sentences in unequal or dependent on the other, you need to use subordinating conjunctions. These connectors often show causality. The most common conjunctions in French for this category are:

7. Style and Flow

Now that you wield the power of conjunctions, you have to be careful with it. As fun as it is to write long and complicated sentences in French, it doesn’t sound good. Make sure you use appropriate sentence lengths as you’re writing in French.

Aim for shorter sentences. Make them explain your point well. But, feel free to mix the flow up with the occasional longer sentences. That’s how you write in French with a nice and smooth flow. And that’s how you perfect your French writing too. It will be a pleasure to read your work.

Writing in French for Advanced Learners

Once you mastered all of the French writing rules, you’re officially an advanced French learner. But, there may still be room to improve your French writing. If you’re looking to kick your projects up a notch, you can learn how to write essays and dissertations in French. These pointers will be useful if you ever attend school or university in France, or you want to take a language exam.

8. Get Familiar with French Essay Structure

When you’re writing an essay, you have to structure it for readability. If you want to learn how French high schoolers are taught to write their essays, this is the structure they follow: thèse-antithèse-synthèse (thesis-antithesis-synthesis). Learn how to write French essays using a traditional French essay structure.

- Introduction : You begin your essay by having an introduction, which is a context for argument.

- Thesis : In this section, you present and defend the statement of your thesis. You need to write everything that supports the topic of your essay.

- Antithesis : The antithesis follows the thesis. This is where you state conflicting evidence and explain other potential substitutes for your essay. Including an antithesis doesn’t mean that you disagree with your original thesis. You just need to show that you thought of all possibilities before arriving to your conclusion.

- Synthesis : This is your conclusion. This is where you summarize your arguments, and explain why you still stand by your original thesis despite the antithesis.

9. Use Introduction and Conclusion Vocabulary

Certain words can encourage sentence flow by introducing or concluding some parts of your work.

- tout d’abord (firstly)

- premièrement (firstly)

- deuxièmement (secondly)

- ensuite (then)

- enfin (finally)

- finalement (finally)

- pour conclure (to conclude)

You can use these words when introducing a new idea to your dissertation or essay. These words will signal the readers that they are encountering a new part or thought of your writing process.

10. Writing a Dissertation in French

This is the form of writing you encounter in French higher education. It’s a very complex form of French writing, only the most advanced and fluent French learners should attempt it. It’s also a longer piece of academic writing. It may take you weeks to complete research and write your French dissertation.

The French dissertation is similar to essay structure. But, there’s one main difference: your thesis isn’t a statement, but rather a question. It’s your job in the dissertation to take the reader through your thought process and research to answer your question. This logic is known as “ Cartesian logic .” It comes from Descartes , who was a well known French philosopher.

History of Written French

French was used in Strasbourg Oaths, and it first appeared in writing in 842 AD. Before then, Latin was the only language used for literature in Europe. However, in the 10th and 11th centuries, French appeared in some religious writings and documents but was not used up to the late 12th century or early 13th century. The first greatest French Literature work, the Song of Roland (Chanson de Roland), was published around the year 1200.

Writing in French Alone Won’t Make You Fluent

You need to learn how to write in French to be proficient in the language. But, it won’t make you fluent. The only way to become fluent is to practice speaking French. While it’s crucial to develop every area of your French knowledge, if you want to be fluent in French, you need a reliable language learning method like OptiLingo.

OptiLingo is an app that gets you speaking, not typing a language. It gives you the most common French words and phrases, so you’re guaranteed to learn the most useful vocabulary. Don’t waste time trying to learn French you’ll never use. Complement your French writing practice with fun speaking exercises when you download OptiLingo !

Related posts

Ultimate Guide to French Verbs: Tenses, Conjugations, and Examples

Express Your Feelings, Mood, and Emotions in French

French Dating Culture and Romantic Relationships

French Pronunciation Guide: How to Speak French in 10 Steps

Many people believe they aren’t capable of learning a language. we believe that if you already know one language, there’s no reason you can’t learn another..

French Your Way

Learn French Online | Learn French Melbourne | French Voices Podcast

How to Write The Perfect French Essay For Your Exam

November 16, 2014 by Jessica 3 Comments

Here are tips to help you write a great French essay with exam requirements in mind. Once you’re done, I strongly suggest you proofread your text using my checklis t.

Note: if you’re preparing for the French VCE, there is an updated version of these exam tips in my guide “How to Prepare for the French VCE & Reach your Maximum Score” .

While supervising exams or tutoring for exam preparation, I’ve seen too many students writing straight away on their exam copies. Stop! Resist the urge to jump on your pen and take a step back to make sure that you will be addressing all the exam requirements or you may be shooting yourself in the foot and lose precious points.

I recommend that you train with exam sample questions so that you set up good working habits and respect the required length of the essay, as well as the timing (allow at least 10 minutes for proofreading).

Crafting your French Essay

1. identify the situation: preparation work.

- Read the topic carefully, slowly and at least twice to absorb every information/detail.

- Underline/highlight/jot down any piece of information that you are expected to reuse:

- What type of text do you need to write? (a journal entry? A formal letter? A speech? Etc). Note to VCE French exam students : refer to page 13 of the VCE French Study Design for more information about the different types of texts.

- Who are you in the situation? (yourself? A journalist? etc)

- Who are you addressing? (a friend? A large audience? Etc) à adjust the degree of formality to the situation (for example by using the “tu”/”vous” form, a casual or formal tone/register, etc)

- What are the characteristic features of the type of text you need to write? (eg a journal entry will have the date, a formal letter will start and end with a formal greeting, etc)

- What is your goal ? What are you expected to talk about / present / defend / convey?

- What are the length requirements for your French essay ? Respect the word count (there’s usually a 5% or so tolerance. Check the requirements specific to your exam)

Tip : when you practice at home, count how many words in average you fit on a line. This will give you a good indication of how many lines your text should be.

Ex: You write an average of 15 words per line. If you are required to write a 300-word French essay, you should aim for:

300 words / 15 words per line = 20 lines total.

2. Draft the outline of your essay

- An essay typically has an introduction, a body with 2 or 3 distinct parts and a conclusion . (See if that outline is relevant to the type of text you are expected to write and adjust accordingly.)

- Use bullet points to organize your ideas.

- Don’t remain too general. A good rule is to use one main idea for each part and to back it up/reinforce in/illustrate it with one concrete example (eg. data).

- Brainstorming about things to say will also help you use a wider range of vocabulary , which will get noticed by the examiner. Are there some interesting/specific words or expressions that you can think of using in your text (example: if you are writing about global warming, brainstorm the vocab related to this topic. Brainstorm expressions to convince or disagree with something, etc)?

- Make sure you have reused every point identified in part 1 .

3. Write your essay

- It’s better if you have time to write or at least draft a few sentences on your draft paper rather than writing directly because:

- You want to meet the word count requirements

- You don’t want multiple words to be barred cross crossed-out and your page looking messy and great anything but neat!

- you don’t want to have to rush so much that your handwriting is really unpleasant to read (or worse, impossible to read…)

- So… monitor your time carefully!

Structuring your text

- Visually, the eye should instantly be able to see the structure of your French essay: make paragraph and skip lines so that it doesn’t look like an unappealing large block of text.

- Use connectors/link words to structure your text and make good transitions.

4. Proofread, proofread, proofread!

- It’s important that you allow at least 10 minutes for proofreading because there most likely are a few mistakes that you can fix very easily. It would therefore be a shame not to give yourself your best chances of success! Check out my Proofreading Checklist.

Bonne chance!

If you need any help with your essay, you can submit it to me there.

- Articles & Tutorials

- French Voices Podcast

- French Your Way Podcast

- News & Updates

info (at) frenchyourway.com.au

PO Box 166, Balaclava, Vic 3183, Australia

Search The Canadian Encyclopedia

Enter your search term

Why sign up?

Signing up enhances your TCE experience with the ability to save items to your personal reading list, and access the interactive map.

- MLA 8TH EDITION

- Girouard, André et al. "Essay in French". The Canadian Encyclopedia , 04 March 2015, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/essay-in-french. Accessed 04 April 2024.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , 04 March 2015, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/essay-in-french. Accessed 04 April 2024." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- APA 6TH EDITION

- Girouard, A., & Andres, B., & Mailhot, L., & Dorion, G. (2015). Essay in French. In The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/essay-in-french

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/essay-in-french" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- CHICAGO 17TH EDITION

- Girouard, André , and Bernard Andres, , and Laurent Mailhot, , and Gilles Dorion. "Essay in French." The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published February 07, 2006; Last Edited March 04, 2015.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published February 07, 2006; Last Edited March 04, 2015." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- TURABIAN 8TH EDITION

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Essay in French," by André Girouard, Bernard Andres, Laurent Mailhot, and Gilles Dorion, Accessed April 04, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/essay-in-french

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Essay in French," by André Girouard, Bernard Andres, Laurent Mailhot, and Gilles Dorion, Accessed April 04, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/essay-in-french" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Essay in French

Article by André Girouard , Bernard Andres , Laurent Mailhot , Gilles Dorion

Published Online February 7, 2006

Last Edited March 4, 2015

The hallmark of the French Canadian essay is that it is both personal (or subjective) and creative. The essay stands apart from any writing that claims to offer an objective explanation of reality or explores a preordained, objective truth that is assumed to be valid for any time and place. The essayist is not at the service of the truth, a cause or a class: he proclaims and defends his own irreducible sincerity and recognizes that, while his experience and the account he gives of it are subjective, they may still serve as a model to others. The essay may range from popular to scholarly treatment of a subject. The writer may just as easily deal with a scientific subject as with a theological, literary or political one, and his tone may be polemical or discursive. The literary quality of an essay, as of any other genre, rests in the quality of the writing, in the capacity of the author to interpret the world about him, to reconstruct it and awaken in the reader as much admiration and wonder for the interpretation as for the reality being interpreted.

ANDRÉ GIROUARD

Pamphlets and Polemics

Philosophical and political essays, pamphlets, manifestos and polemic exchanges are all arguably forms of the essay. When placed in their original contexts, they afford excellent opportunities to observe sociopolitical and cultural phenomena of their eras. Polemical texts and pamphlets are not always self-evidently critical in nature, and they are made all the more effective when the author's indignation is camouflaged. A complete polemic structure is to be found as an undercurrent in accounts of early voyages, in private and administrative correspondence and in the writings of religious orders in New France. Generally addressed to authorities in the mother country, these texts crystallize metropolitan antagonisms around Canadian situations. They contain a double contradiction, expressing the New World in the linguistic and cultural codes of the mother country, which is itself replete with antagonisms such as those between Recollets and Jesuits or, at another level, proponents of evangelization and champions of exploitation.

The texts of Cartier, Champlain, Lescarbot, Biard and Sagard, and the JESUIT RELATIONS ( see EXPLORATION AND TRAVEL LITERATURE IN FRENCH ) should be read in the context of the actual conditions in which they were written (literary strategies, thinly veiled battles to obtain local credit, privilege and power). So, too, should one read the protests of Canadian naval personnel against French officers during the Seven Years' War. Essays of protest continued to be written after the Conquest, and pamphlets regarding the GUIBORD AFFAIR (1869-74) and the battle between Monseigneur BOURGET and the INSTITUT CANADIEN carried the genre into the late 19th century. Parliamentary battles in the Canadas gave scope to the pamphleteer and essayist as well: oratorical jousts were taken up and exaggerated in the polemics between francophone and anglophone newspapers (eg, in the Anti-Gallic Letters ).

Striking examples of the use of polemical essays in political settings include exchanges during the MANITOBA SCHOOLS QUESTION (1890-96), the anticommunist campaigns of the 1930s ( Pamphlets de Valdombre , 1936-43) and the CONSCRIPTION debates during the 2 world wars. In 1960 Jean-Paul DESBIENS , in LES INSOLENCES DU FRÈRE UNTEL , and Gilles Leclerc, in Journal d'un inquisiteur , took up the language debate and other matters with vehemence. The authors offer pragmatic commentary on current events, using this as a device to discredit the targets of their scorn, hoping thus to alter the attitudes of the reading public. Since the QUIET REVOLUTION there has been an explosion of polemical writings about independence, unionism and native people by leftist individuals, groups and magazines. More recently feminism held the limelight, with its radical challenge to all the institutions that have traditionally excluded women.

BERNARD ANDRES

Political Essay

Political essays may be distinguished from other works in the fields of history, sociology and political science as the products of a more personal and untrammelled quest. Memoirs, reminiscences, notebooks, diaries and autobiographical fragments all overlap partially and unevenly with the political essay. Among the best political memoirs in French are the 3 volumes by Georges-Émile LAPALME , the leader of the Québec Liberal Party who was caught between Premier Maurice DUPLESSIS and Prime Minister Louis ST-LAURENT . He makes some lucid comments on the subject of the limits of political action.

The major political or ideological essays of the 19th century were not the work of orators or public figures (Papineau, Mercier, Laurier) but the discussions and chronicles of some leading journalists (Étienne PARENT , Arthur BUIES ). L'Avenir du peuple canadien-français (1896), by sociologist Edmond de Nevers, was a cultural and deeply political essay, a mixture of idealism, pessimism and prophecy. In the 20th century as well, the best political essays have been the work of a few well-educated journalists (Olivar Asselin, Jules Fournier, André LAURENDEAU ) and nationalist historians (Lionel GROULX , Michel Brunet). They raised (or revived) the question of Québec's relations with London and Paris and with English Canadians; they were as concerned about war and conscription as about elections.

The birth of political magazines free from party affiliation - CITÉ LIBRE (1950-66) and PARTI PRIS (1963-68) - led to a proliferation of the political essay. The collection of articles, studies and testimonials about the ASBESTOS STRIKE , La Grève de l'amiante (1956), which appeared with a comprehensive introduction by Pierre Elliott TRUDEAU , was the prototype for numerous other collections. Many were the products of conferences, such as that held in Cerisy-la-Salle, France ( Le Canada au seuil du siècle de l'abondance , 1969), which had brought together Francophones of every persuasion. Independentists produced manifestos, declarations and testimonies, but also a few essays of a more structured nature, such as Le Colonialisme au Québec (1966) by André d'Allemagne.

A Marxist-tinged theory of decolonization, inspired by the experiences and rhetoric of developing nations, marked a number of the essays published at the beginning of the Quiet Revolution, in particular NÈGRES BLANCS D'AMÉRIQUE (1968) by Pierre Vallières. Neo-federalists (most of them in the group around Trudeau and Gérard PELLETIER ) began countering the arguments of the fervent neo-nationalists. They seemed to be calmer and more staid than their antagonists, but they were just as lively in their use of history and statistics. Essays in their true form were rare: the writers slid easily from a constitutional treatise or thesis to a circumstantial or journalistic approach.

Some of the meatiest and most thought-provoking essays written since the late 1960s are Le Canada français après deux siècles de patience (1967) by political scientist Gérard Bergeron; LA DERNIÈRE HEURE ET LA PREMIÈRE (1973) by Pierre VADEBONCOEUR , trade unionist turned writer; La Question du Québec (1971) by sociologist Marcel Rioux; and Le Développement des idéologies au Québec (1977) by political scientist Denis Monière. The most trenchant political essays are perhaps to be found in certain novels (eg, those of Hubert AQUIN and Jacques FERRON ).

Québec political essayists have been obsessed since the mid-1960s by the state and the constitution. Subjects now discussed move beyond partisanship and dogma to a new definition of the central issue: the division of powers is not solely a Québec-Ottawa dispute; it is also an issue for Montréal and its suburbs, the regions of Québec, women and ethnic and marginal groups. The postreferendum period was marked by important essays on language and culture as well as economics and the role of the state. Among the less systematic but more intense and vivid of the collections were those of columnists Lysiane Gagnon ( Chroniques politiques , 1985) and of Lise Bissonnette ( La Passion du présent , 1987), whose "Les Yvettes" served as a stimulus for the Non faction. René Lévesque contributed his memoirs ( Attendez que je me rappelle ... , 1986). Then there was a study of international as well as national politics, more precisely, the Québec-Ottawa-Paris triangle, by former minister of intergovernmental affairs Claude Morin.

Since the midseventies, the literary journal Liberté has published the best political essays on topics such as language and translation, official bilingualism and biculturalism, culture, money and the State. It has dedicated special issues to topics such as referendums, majorities and minorities and Anglo-Montrealers. Many contributors to Liberté include political articles in their collections of essays. For the late André Belleau ( Surprendre les voix , 1986), BILL 101 is not racist, but anti-racist, a tool of development. So thinks Jean Larose, whose la Petite Noirceur won a controversial Governor General's Award in 1987. Larose is a vivid polemicist in la Souveraineté rampante (1994), addressed to shy, tired, soft sovereigntists.

For Belleau, Larose and Liberté's editors, François Ricard, François Hébert, Marie-Andrée Lamontagne and their friends, it is not difficult to be a Québec independentist without being a narrow, ethnic nationalist. For Mordecai RICHLER 's followers, it is impossible. For college teacher Nadia Khouri ( Qui a peur de Mordecai Richler? , 1995), there is no real difference between right-wing Canon GROULX and René LÉVESQUE or Le Devoir ; bad Québec's ideological elites are opposed to good old grass-rooted people.

Original points of view on individual and collective identity may be found in Lise Gauvin's Lettres d'une autre (1984), whose main question is inspired by Montesquieu: "Comment peut-on être Québécois(e)? " The second volume of former minister and poet Gérald Godin's Ecrits et parlés is about Politique (1993), before and after 1976, when he defeated Premier Robert Bourassa in his own riding. Critic and novelist André Brochu's La Grande Langue (1993) is an ironical panegyric of English as a language of power. Genèse de la societé québécoise (1993) by sociologist Fernand Dumont is a strong synthesis of French Canadian history, memory, consciousness. Dumont published also Raisons communes (1995), a collection of substantial articles on foundations, collective identity, democracy, intellectuals and citizens, and French (a "language in exile").

LAURENT MAILHOT

Literary Essay

Unlike literary criticism, which necessarily passes judgement on the work under study, the literary essay freely considers the written work, offering nondefinitive, personal comments on its aesthetic value. The literary essay first appeared in newspapers and magazines of the mid-19th century as well as in papers presented in literary circles, at the Institut canadien and in similar reading groups. These first stirrings prepared the way for true literary essayists, Étienne Parent and Napoléon Aubin, Abbé Henri-Raymond CASGRAIN , Octave CRÉMAZIE , Arthur Buies and a few others who were prompted by religious and moral concerns to deal with aesthetic questions.

The literary essay developed along nationalist and regionalist lines in Québec in the early 20th century, thanks to Laval professor Camille ROY , who explored the "nationalization" of French Canadian literature in some 30 essays. He was followed by Olivier Maurault and Émile Chartier of Université de Montréal, and other major voices of nationalism such as Lionel Groulx, who concentrated on the land, the parish, the family, religion, customs and ancestral traditions - and by the next wave, regionalist writers associated with the journals Le Pays laurentien , La Revue nationale and L' ACTION FRANÇAISE (later L'Action canadienne-française and then L'Action nationale ).

The "Parisianists" ("exotics"), who followed modern French thought in their subjects and writings and often sharply disagreed with the first group, included Paul Morin, Marcel Dugas, Jean Charbonneau, Robert de Roquebrune, Olivar Asselin, Victor Barbeau and his Cahiers de Turc (1921-22; 1926-27), and the people associated with LE NIGOG , Cahiers des Jeunes-Canada and LA RELÈVE . In the long run, the often vigorous disagreements led to an affirmation of a French Canadian literature that was autonomous yet always strongly influenced by France.

With this ideological battle behind them, writers could finally pay serious attention to the different genres of expression. From 1940 to 1960 the literary essay was particularly important. The many publications included writings about Canadian as well as French authors; general studies of French Canadian literature by critics such as Roger Duhamel, Benoît Lacroix and Séraphin Marion; specialized studies of THEATRE by Léopold Houlé and Jean Béraud, of poetry by Jeanne Crouzet and of the novel by Dostaler O'Leary; and histories of literature by Samuel Baillargeon, Berthelot Brunet and Auguste Viatte.

The proliferation of literary essays has been boosted since the Quiet Revolution by the development of the teaching of Québec literature ( see LITERATURE IN FRENCH: SCHOLARSHIP AND TEACHING ). Analyses of literature and of literary movements (the historical novel, the novel of the soil, literary nationalism, Parti pris , the AUTOMATISTES , surrealism) were accompanied by many essays dealing with literary genres: the novel (Gérard Bessette, Yves Dostaler, Jacques Blais, Maurice Lemire, Gilles Marcotte, Mireille Servais-Maquoi, Henri Tuchmaïer); theatre (Michel Belair, Beaudoin Burger, Jacques Cotnam, Martial Dassylva, Jan Doat, Jean-Cléo Godin and Laurent Mailhot, Chantal Hébert, G.E. Rinfret); poetry (Paul Gay, Philippe Haeck, Jeanne d'Arc Lortie, Axel Maugey); and the literary essay (Jean Terrasse). There were treatments of specific subject matter (themes of the family, of winter, etc), a host of monographs on French Canadian writers, general studies of Québec literature (Guy Laflèche, Gilles Marcotte, Jean Ménard, Guy Robert) and histories of literature (Pierre de Grandpré, Laurent Mailhot, Gérard Tougas). There are also collective literary essays such as the Archives des lettres canadiennes , and anthologies, including L'Anthologie de la littérature québécoise (directed by Gilles Marcotte) and the Dictionnaire des oeuvres littéraires du Québec (directed by Maurice Lemire) - highly useful works, although their contents tend to be literary criticism rather than essays. Only rarely do Québec essayists study broad issues the way Europeans do. Finally, most Québec literary essays are aimed at students and professors in both foreign and Québec colleges and universities, though they are occasionally intended to reach a larger public.

GILLES DORION

Authors contributing to this article:

Recommended

Foreign Writers on Canada in French

Literature in french: scholarship and teaching, literary prizes in french.

- Look up in Linguee

- Suggest as a translation of "essays"

Linguee Apps

▾ dictionary english-french, essays noun, plural ( singular: essay ) —, essais pl m ( singular: essai m ), essay noun —, essai m ( plural: essais m ), étude f ( plural: études f ), dissertation f, composition f ( plural: compositions f ), rédaction f ( plural: rédactions f ), photo essay n —, essay writing n —, essay contest n —, essay competition n —, short essay n —, research essay n —, argumentative essay n —, photographic essay n —, critical essay n —, written essay n —, essay topic n —, long essay n —, literary essay n —, brief essay n —, philosophical essay n —, political essay n —, first essay n —, second essay n —, ▸ wikipedia, ▾ external sources (not reviewed).

- This is not a good example for the translation above.

- The wrong words are highlighted.

- It does not match my search.

- It should not be summed up with the orange entries

- The translation is wrong or of bad quality.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

How do I efficiently write essays in French?

This worksheet is geared towards advanced French Majors. It provides guidance on and tools for essay-writing in various genres. It is accompanied by “Know Your Audience: Undergraduate Writing and Speaking.” For oral assignments, please consult “What Makes For an Efficient Oral Presentation?” This document was created in Winter 2021 and last updated in Summer 2023. For its last revision, the author benefited from the valuable input of former students Marley Fortin, Merve Ozdemir, and Elizabeth Swanson.

Related Papers

Johannes Junge Ruhland

The aim of this worksheet is to provide advanced undergraduates with the tools to tailor their written and oral assignments to a well-defined audience in a specific communicative context such as written assignments and in-class presentations. The imagined audience of this paper are French literature Majors. This worksheet accompanies how-to guides specifically for undergraduate essay-writing in French and undergraduate oral presentations in literature and related fields: “How Do I Efficiently Write Essays in French?” and “What Makes for an Efficient Oral Presentation?” It was created in Summer 2023 with the valuable input and feedback of former students Kayne Belul and Emily Martinez.

Hela Mornagui

Paul Wadden

afraz ahmad

International Journal for Research in Applied Sciences and Biotechnology

Muhammad Hattah Fattah

Writing is one of the most well-known phenomena that may help a civilization evolve and improve. Writing is how a society's knowledge, literature, and culture are passed down from generation to generation for millennia. Writing, as a significant aspect of civilization, should be constantly improved, updated, and given special attention so that it can carry knowledge across generations in the most efficient manner possible. We all know that writing is a difficult process that needs more thought and time. This difficult activity needs extreme care in order to be completed correctly. In this study topic, I've covered a wide range of topics related to essay writing, including how to write an essay, the stages to writing an essay, why write an essay, prewriting, and how to research, prepare, and write an essay. The purpose of the research on this topic is, in the first how to research and write an academic essay, steps and plans of writing an essay, essay writing checklist and th...

Teodora Popescu

Cette étude présente l’analyse d’un corpus d’essais écrits par des apprenants de la langue anglaise (LEWC) compte tenu de la perspective offerte par l’analyse computationnelle. Le sous-corpus de LEWC visé par notre ci-présente analyse comprend 30 essais (environ 13 600 mots) rédigés par des apprenants de la langue anglaise, ayant un niveau intermédiaire, ceux-ci étant étudiants en sciences économiques. Tout en utilisant de divers moyens de l’analyse computationnelle nous avons élaboré une classification des types d’erreurs y enregistrées. Nos futures recherches seront dirigées vers l’amélioration des compétences en anglais écrit.

Betsy Gilliland

Ned Stuckey-French

Writing academic texts is an inevitable component of contemporary higher education; writing in a more specific sense is an indispensable method when teaching a particular subject (Blau, 2003). As a species of text, essay-form is an integral piece of writing in which one expresses in depth his/her opinions or feelings on a particular subject. In higher education teaching, essay-form has been used mainly as an individually graded writing task, which enables students to align their own subjective points of view to more general philosophical or scientific perspectives. For this type of academic or English style essay, it is common to have a rather personal discursive overall mood, critical and argumentative perspective, and stylistic comprehension. While the essay, in its traditional form, involves logic, dialectics, and rhetoric, it still enables students to put forward their own personal views as well as to interpret the variety of generic features of the essay-form in a more general ...

Natalie G Sharpling

RELATED PAPERS

harold andres ordoñez muñoz

The Journal of Arthroplasty

Henrik Malchau

Joachim Spangenberg

Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering

Darren Mifsud

Fitopatologia Brasileira

Edna Dora Newman Luz

Eckhard Burkatzki

Guillermo Velázquez

Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter

Elmustapha Feddi

medigraphic.com

oscar manuel berlanga bolado

Derek Rosenzweig

Vanja Tanasić

ECTI Transactions on Computer and Information Technology (ECTI-CIT)

Ureerat Suksawatchon

Agricultural Systems

Jeremy Haggar

Pollarise GROUPS

Sustainable Competitive Advantage

Najmudin Najmudin

Catalysis Today

Johannes Schwank

Human immunology

James Mathew

Dayan Sipahutar

Internal Medicine

Akira Takahashi

Journal of Affective Disorders

Enrico Massimetti

Agricultural Engineering International: The CIGR Journal

Mohamed Samer

Jerry Coakley

ARAM Periodical Volume 34

Patrick Scott-Geyer

Jean-Michel Schroëtter

British Journal of Pharmacology

Patricio Castro Sáez

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Free Resources

- 1-800-567-9619

- Subscribe to the blog Thank you! Please check your inbox for your confirmation email. You must click the link in the email to verify your request.

- Explore Archive

- Explore Language & Culture Blogs

What’s The Problem? – Writing A Thesis In French Posted by John Bauer on Aug 31, 2016 in Culture , Vocabulary

These past few weeks I’ve been hard at work on mon mémoire (my thesis). The last big project for un diplôme (a degree) is always hard, and writing un mémoire in another language makes the whole process even more of un casse-tête (a headache).

“ Place de la Sorbonne ” by Alan on Flickr. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

I came to France to do mon master (my Master’s), and it has been an interesting exeprience learning how nobody’s perfect and what a CM and TD are . Now hard at work on mon mémoire , I’m struggling to find enough café (coffee) to keep me going.

Writing more than cinquante pages (fifty pages) en français has been tough. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve mixed up the words une mémoire (a memory) and un mémoire (a thesis). Not to mention all the other dual gender nouns .

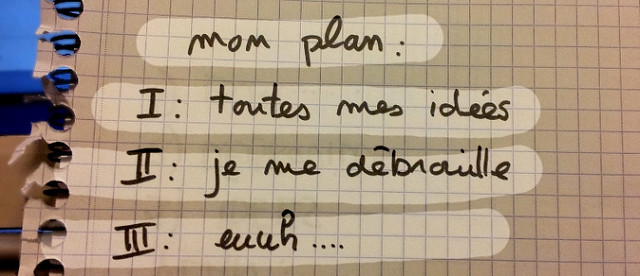

To make things easier, le mémoire should follow le plan (the outline), but sometimes il est difficile de savoir par où commencer (it’s hard to know where to start).

“ Plan de dissertation ” by dicophilo on Flickr. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Figuring out une problématique is a big part of writing un mémoire . Once you have une idée (an idea) you have to fix not just le grammaire (the grammar), but le raisonnement et la logique (the reasoning and logic) as well.

C’est quoi une problématique ? What is une problématique?

Une problématique is a thesis statement to some people. In my experience, they are used in the same general educational contexts. Cependant (however), they do not mean exactly the same thing.

The word for a thesis statement is une thèse principale or un énoncé de la thèse .

It’s a subtle difference, but la problématique is more about defining the research problem or outlining the research problem rather than a summary of the main point or presenting un point de vue (a point of view) and making a claim.

It can be difficult to understand how to succeed in the French education system without understanding this difference. Surtout (especially) because in the classroom you’ll hear le professeur (the professor) talk about the importance of la problématique in the same way you would hear le professeur talk about the thesis statement in aux États-Unis (in the United States).

There is also a lot to learn about les travaux universitaires (academic writing). All the nuances of specific wordings can easily get lost in translation. The main ideas of writing clearly, citing your sources, creating a bibliography, and proper formatting are all the same, but the details can be different enough that figuring out how to write correctly is un casse-tête .

De plus (what’s more), if you went to school in the US, you are probably familiar with MLA or APA formatting and it’s hard to realize that those are American guidelines.

Ne vous inquiétez pas ! Don’t worry!

In France, all the information you need is in le guide de mise en page (the style guide) provided by le professeur .

Maintenant (now), the biggest problem I have is that with la canicule it’s too hot to drink du café !

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: John Bauer

John Bauer is an enthusiast for all things language and travel. He currently lives in France where he's doing his Master's. John came to France four years ago knowing nothing about the language or the country, but through all the mistakes over the years, he's started figuring things out.

Voice speed

Text translation, source text, translation results, document translation, drag and drop.

Website translation

Enter a URL

Image translation

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

A Simple Guide to Talking About School in French: Subjects, Rooms and More

School and education is one of the most common talking points for French learners.

Whether you’re navigating a new French class, preparing for the speaking portion of a test like the GCSE or making friends with French-speaking students , it’s important to know lots of school vocabulary.

That’s exactly what I’ll give you in this post, with more than 100 words for people, places and things you’ll need to know for talking about school in French!

People at School

Levels of schooling, school subjects, rooms in a school building, school supplies, school assignments, and one more thing....

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

L’étudiant / L’étudiante – Student

Le/ La camarade de classe – Classmate

Le professeur – Teacher/Professor

L’entraîneur – Coach

L’infirmier / L’infirmière – Nurse

Le proviseur / Le chef d’établissement – Principal or Headmaster

Le proviseur adjoint – Vice Principal

L’école – School

L’école public – Public school

L’école privée – Private school

L’école de langue – Language school

L’école maternelle – Preschool

L’école primaire – Primary school