- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

- Academy of American Poets

User account menu

Search more than 3,000 biographies of contemporary and classic poets.

Page submenu block

- literary seminars

- materials for teachers

- poetry near you

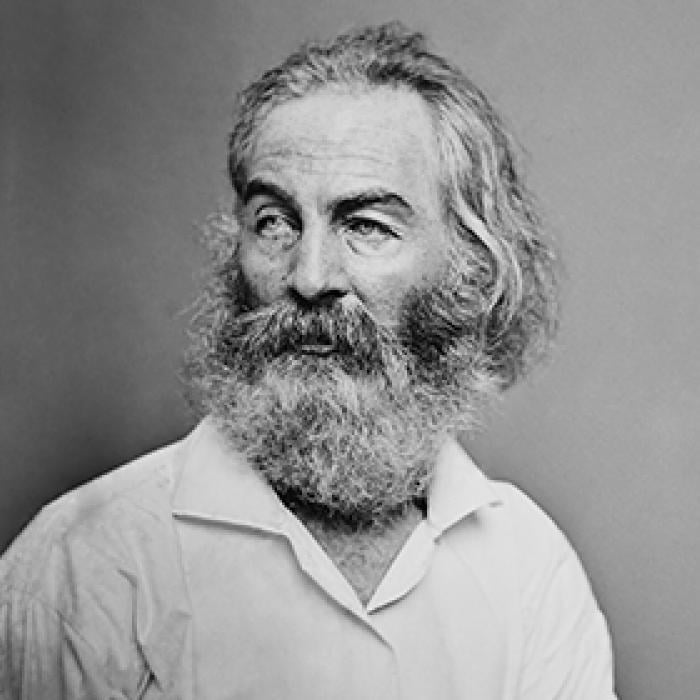

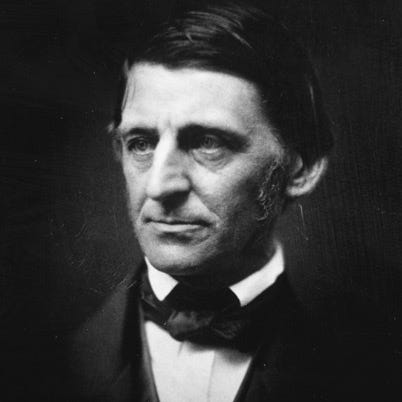

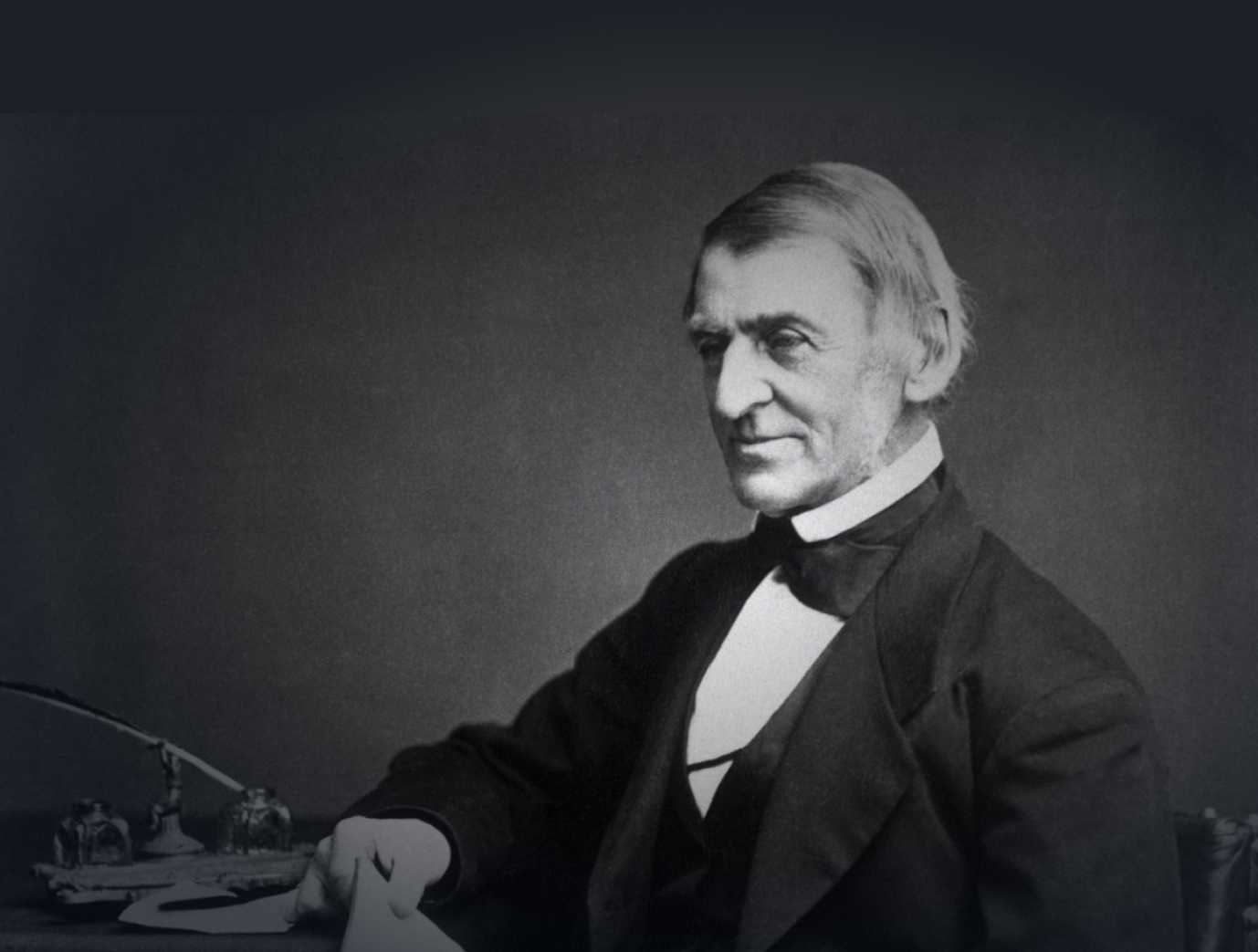

Ralph Waldo Emerson

American poet, essayist, and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson was born on May 25, 1803, in Boston. After studying at Harvard and teaching for a brief time, Emerson entered the ministry. He was appointed to the Old Second Church in his native city, but soon became an unwilling preacher. Unable in conscience to administer the sacrament of the Lord’s Soon after the death of his nineteen-year-old wife of tuberculosis, Emerson resigned his pastorate in 1831.

The following year, Emerson sailed for Europe, visiting Thomas Carlyle and Samuel Taylor Coleridge . Carlyle, the Scottish-born English writer, was famous for his explosive attacks on hypocrisy and materialism, his distrust of democracy, and his highly romantic belief in the power of the individual. Emerson’s friendship with Carlyle was both lasting and significant; the insights of the British thinker helped Emerson formulate his own philosophy.

On his return to New England, Emerson became known for challenging traditional thought. In 1835, he married his second wife, Lydia Jackson, and settled in Concord, Massachusetts. Known in the local literary circle as “The Sage of Concord,” Emerson became the chief spokesman for Transcendentalism, the American philosophic and literary movement. Centered in New England during the nineteenth century, Transcendentalism was a reaction against scientific rationalism.

Emerson’s first book, Nature (1836), is perhaps the best expression of his Transcendentalism, the belief that everything in our world—even a drop of dew—is a microcosm of the universe. His concept of the Over-Soul—a Supreme Mind that every man and woman share—allowed Transcendentalists to disregard external authority and to rely instead on direct experience. “Trust thyself,” Emerson’s motto, became the code of Margaret Fuller, Bronson Alcott, Henry David Thoreau, and W. E. Channing. From 1842 to 1844, Emerson edited the Transcendentalist journal, The Dial .

Emerson wrote a poetic prose, ordering his essays by recurring themes and images. His poetry, on the other hand, is often called harsh and didactic. Among Emerson’s most well known works are Essays, First and Second Series (1841, 1844). The First Series includes Emerson's famous essay, “Self-Reliance,” in which the writer instructs his listener to examine his relationship with Nature and God, and to trust his own judgment above all others.

Emerson’s other volumes include Poems (1847), Representative Men (1850), The Conduct of Life (1860), and English Traits (1865). His best-known addresses are The American Scholar (1837) and The Divinity School Address , which he delivered before the graduates of the Harvard Divinity School, shocking Boston’s conservative clergymen with his descriptions of the divinity of man and the humanity of Jesus.

Emerson’s philosophy is characterized by its reliance on intuition as the only way to comprehend reality, and his concepts owe much to the works of Plotinus, Emanuel Swedenborg, and Jakob Böhme. A believer in the “divine sufficiency of the individual,” Emerson was a steady optimist. His refusal to grant the existence of evil caused Herman Melville , Nathaniel Hawthorne , and Henry James, Sr., among others, to doubt his judgment. In spite of their skepticism, Emerson’s beliefs are of central importance in the history of American culture.

Ralph Waldo Emerson died of pneumonia on April 27, 1882.

Related Poets

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth, who rallied for "common speech" within poems and argued against the poetic biases of the period, wrote some of the most influential poetry in Western literature, including his most famous work, The Prelude , which is often considered to be the crowning achievement of English romanticism.

W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats, widely considered one of the greatest poets of the English language, received the 1923 Nobel Prize for Literature. His work was greatly influenced by the heritage and politics of Ireland.

Walt Whitman

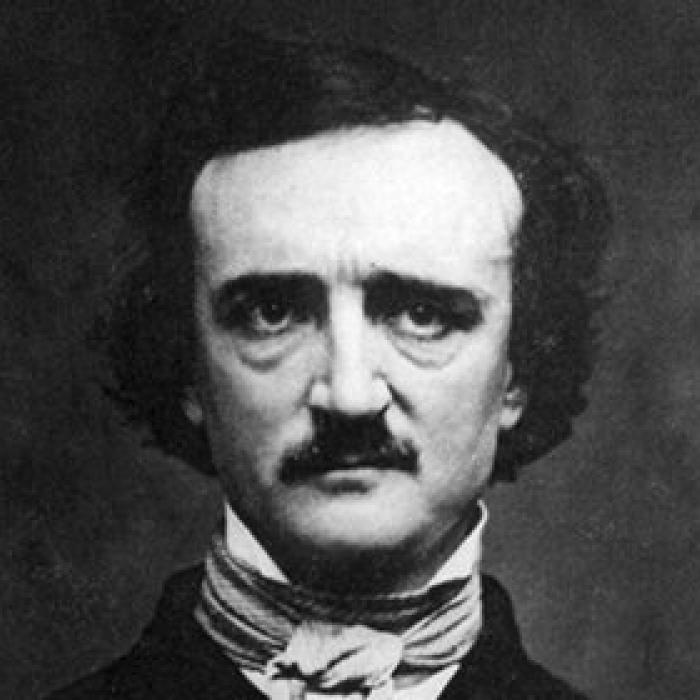

Edgar Allan Poe

Born in 1809, Edgar Allan Poe had a profound impact on American and international literature as an editor, poet, and critic.

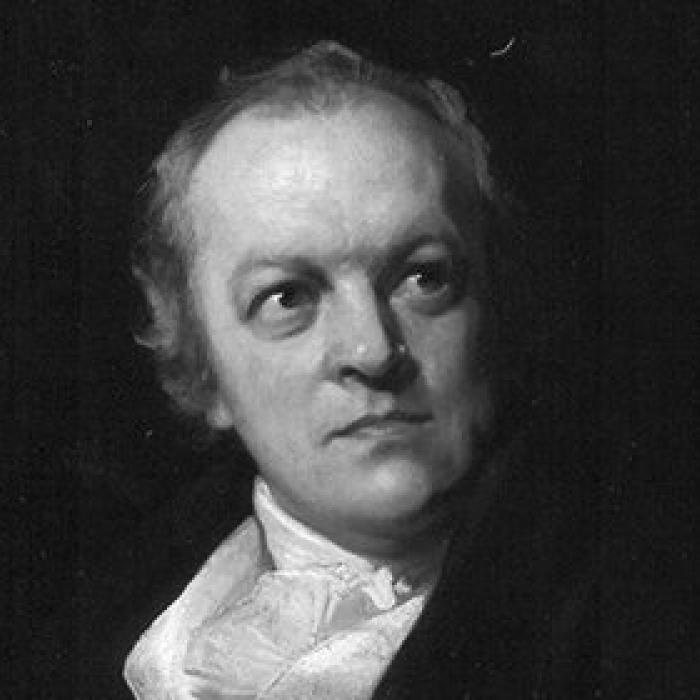

William Blake

William Blake was born in London on November 28, 1757, to James, a hosier, and Catherine Blake. Two of his six siblings died in infancy. From early childhood, Blake spoke of having visions—at four he saw God "put his head to the window"; around age nine, while walking through the countryside, he saw a tree filled with angels.

Newsletter Sign Up

- Academy of American Poets Newsletter

- Academy of American Poets Educator Newsletter

- Teach This Poem

Ralph Waldo Emerson

An American essayist, poet, and popular philosopher, Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–82) began his career as a Unitarian minister in Boston, but achieved worldwide fame as a lecturer and the author of such essays as “Self-Reliance,” “History,” “The Over-Soul,” and “Fate.” Drawing on English and German Romanticism, Neoplatonism, Kantianism, and Hinduism, Emerson developed a metaphysics of process, an epistemology of moods, and an “existentialist” ethics of self-improvement. He influenced generations of Americans, from his friend Henry David Thoreau to John Dewey, and in Europe, Friedrich Nietzsche, who takes up such Emersonian themes as power, fate, the uses of poetry and history, and the critique of Christianity.

1. Chronology of Emerson's Life

2.1 education, 2.2 process, 2.3 morality, 2.4 christianity, 2.6 unity and moods, 3.1 consistency, 3.2 early and late emerson, 3.3 sources and influence, works by emerson, selected writings on emerson, other internet resources, related entries, 2. major themes in emerson's philosophy.

In “The American Scholar,” delivered as the Phi Beta Kappa Address in 1837, Emerson maintains that the scholar is educated by nature, books, and action. Nature is the first in time (since it is always there) and the first in importance of the three. Nature's variety conceals underlying laws that are at the same time laws of the human mind: “the ancient precept, ‘Know thyself,’ and the modern precept, ‘Study nature,’ become at last one maxim” (87). Books, the second component of the scholar's education, offer us the influence of the past. Yet much of what passes for education is mere idolization of books — transferring the “sacredness which applies to the act of creation…to the record.” The proper relation to books is not that of the “bookworm” or “bibliomaniac,” but that of the “creative” reader who uses books as a stimulus to attain “his own sight of principles.” Used well, books “inspire…the active soul” (88). Great books are mere records of such inspiration, and their value derives only, Emerson holds, from their role in inspiring or recording such states of the soul. The “end” Emerson finds in nature is not a vast collection of books, but, as he puts it in “The Poet,” “the production of new individuals,…or the passage of the soul into higher forms” (CW3:14)

The third component of the scholar's education is action. Without it, thought never “ripens into truth.” Action is the process whereby what is not fully formed passes into expressive consciousness (91–2). Action is also the scholar's “dictionary,” the source for what she has to say. The true scholar speaks from experience, not in imitation of others; her words, as Emerson puts it, are “are loaded with life…” (Z: 92). The scholar's education in original experience and self-expression is appropriate, according to Emerson, not only for a small class of people, but for everyone. Its goal is the creation of a democratic nation. Only when we learn to “walk on our own feet” and to “speak our own minds,” he holds, will a nation “for the first time exist” (Z: 104–5).

Emerson returned to the topic of education late in his career in “Education,” an address he gave in various versions at graduation exercises in the 1860's. Self-reliance appears in the essay in his discussion of respect. The “secret of Education,” he states, “lies in respecting the pupil.” It is not for the teacher to choose what the pupil will know and do, but for the pupil to discover “his own secret.” The teacher must therefore “wait and see the new product of Nature” (L: 143), guiding and disciplining when appropriate-not with the aim of encouraging repetition or imitation, but with that of finding the new power that is each child's gift to the world. The aim of education is to “keep” the child's “nature and arm it with knowledge in the very direction in which it points” (L: 144). This aim is sacrificed in mass education, Emerson warns. Instead of educating “masses,” we must educate “reverently, one by one,” with the attitude that “the whole world is needed for the tuition of each pupil” (L: 154).

Emerson is in many ways a process philosopher, for whom the universe is fundamentally in flux and “permanence is but a word of degrees” (CW 2: 179). Even as he talks of “Being,” Emerson represents it not as a stable “wall” but as a series of “interminable oceans” (CW3: 42). This metaphysical position has epistemological correlates: that there is no final explanation of any fact, and that each law will be incorporated in “some more general law presently to disclose itself” (CW2: 181). Process is the basis for the succession of moods Emerson describes in “Experience,” (CW3: 30), and for the emphasis on the present throughout his philosophy.

Some of Emerson's most striking ideas about morality and truth follow from his process metaphysics: that no virtues are final or eternal, all being “initial,” (CW2: 187); that truth is a matter of glimpses, not steady views. We have a choice, Emerson writes in “Intellect,” “between truth and repose,” but we cannot have both (CW2: 202). Fresh truth, like the thoughts of genius, comes always as a surprise, as what Emerson calls “the newness” (CW3: 40). He therefore looks for a “certain brief experience, which surprise[s] me in the highway or in the market, in some place, at some time…” (Z: 253). This is an experience that cannot be repeated by simply returning to a place or to an object such as a painting. A great disappointment of life, Emerson finds, is that one can only “see” certain pictures once, and that the stories and people who fill a day or an hour with pleasure and insight are not able to repeat the performance.

Emerson's basic view of religion also coheres with his emphasis on process, for he holds that one finds God only in the present: “God is, not was” (Z: 123). In contrast, what Emerson calls “historical Christianity” (114) proceeds “as if God were dead” (Z: 116). Even history, which seems obviously about the past, has its true use, Emerson holds, as the servant of the present: “The student is to read history actively and not passively; to esteem his own life the text, and books the commentary” (CW2:5).

Emerson's views about morality are intertwined with his metaphysics of process, and with his perfectionism, his idea that life has the goal of passing into “higher forms” (CW3:14). The goal remains, but the forms of human life, including the virtues, are all “initial” (CW2: 187). The word “initial” suggests the verb “initiate,” and one interpretation of Emerson's claim that “all virtues are initial” is that virtues initiate historically developing forms of life, such as those of the Roman nobility or the Confucian junxi . Emerson does have a sense of morality as developing historically, but in the context in “Circles” where his statement appears he presses a more radical and skeptical position: that our virtues often must be abandoned rather than developed. “The terror of reform,” he writes, “is the discovery that we must cast away our virtues, or what we have always esteemed such, into the same pit that has consumed our grosser vices” (CW2: 187). The qualifying phrase “or what we have always esteemed such” means that Emerson does not embrace an easy relativism, according to which what is taken to be a virtue at any time must actually be a virtue. Yet he does cast a pall of suspicion over all established modes of thinking and acting. The proper standpoint from which to survey the virtues is the ‘new moment‘ “the moment of truth rather than repose” (CW2:202), in which what once seemed important may appear “trivial” or “vain.” From this perspective (or more properly the developing set of such perspectives) the virtues do not disappear, but they may be fundamentally altered and rearranged.

Although Emerson is thus in no position to set forth a system of morality, he nevertheless delineates throughout his work a set of virtues and heroes, and a corresponding set of vices and villains. In “Circles” the vices are “forms of old age,” and the hero the “receptive, aspiring” youth (CW2:189). In the “Divinity School Address,” the villain is the “spectral” preacher whose sermons offer no hint that he has ever lived. “Self Reliance” condemns virtues that are really “penances” (CW2: 31), and the philanthropy of abolitionists who display an idealized “love” for those far away, but are full of hatred for those close by (CW2: 30).

Conformity is the chief Emersonian vice, the opposite or “aversion” of the virtue of “self-reliance.” We conform when we pay unearned respect to clothing and other symbols of status, when we show “the foolish face of praise” or the “forced smile which we put on in company where we do not feel at ease in answer to conversation which does not interest us” (CW2: 32). Emerson criticizes our conformity even to our own past actions-when they no longer fit the needs or aspirations of the present. This is the context in which he states that “a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen, philosophers and divines” (CW2: 33). There is wise and there is foolish consistency, and it is foolish to be consistent if that interferes with the “main enterprise of the world for splendor, for extent, …the upbuilding of a man” (99).

If Emerson criticizes much of human life, he nevertheless devotes most of his attention to the virtues. Chief among these is what he calls “self-reliance.” The phrase connotes originality and spontaneity, and is memorably represented in the image of a group of nonchalant boys, “sure of a dinner…who would disdain as much as a lord to do or say aught to conciliate one…” The boys sit in judgment on the world and the people in it, offering a free, “irresponsible” condemnation of those they see as “silly” or “troublesome,” and praise for those they find “interesting” or “eloquent.” (CW2: 29). The figure of the boys illustrates Emerson's characteristic combination of the romantic (in the glorification of children) and the classical (in the idea of a hierarchy in which the boys occupy the place of lords or nobles).

Speaking of “self-reliance,” Emerson nevertheless warns-undermining his own previous statements-can be a “poor external way of speaking” (CW 2:40). For it can be taken to mean that there is a self already formed on which we may rely. The “self” on which we are to “rely” is, in contrast, the original self that we are in the process of creating. Such a self, to use a phrase from Nietzsche's Ecce Homo, “becomes what it is.”

For Emerson, the best human relationships require the confident and independent nature of the self-reliant. Emerson's ideal society is a confrontation of powerful, independent “gods, talking from peak to peak all round Olympus.” There will be a proper distance between these gods, who, Emerson advises, “should meet each morning, as from foreign countries, and spending the day together should depart, as into foreign countries” (CW 3:81). Even “lovers,” he advises, “should guard their strangeness” (CW3: 82). Emerson portrays himself as preserving such distance in the cool confession with which he closes “Nominalist and Realist,” the last of the Essays, Second Series :

I talked yesterday with a pair of philosophers: I endeavored to show my good men that I liked everything by turns and nothing long…. Could they but once understand, that I loved to know that they existed, and heartily wished them Godspeed, yet, out of my poverty of life and thought, had no word or welcome for them when they came to see me, and could well consent to their living in Oregon, for any claim I felt on them, it would be a great satisfaction (CW 3:145).

The self-reliant person will “publish” her results, but she must first learn to detect that spark of originality or genius that is her particular gift to the world. It is not a gift that is available on demand, however, and a major task of life is to meld genius with its expression. “The man,” Emerson states “is only half himself, the other half is his expression” (CW 3:4). There are young people of genius, Emerson laments in “Experience,” who promise “a new world” but never deliver: they fail to find the focus for their genius “within the actual horizon of human life” (CW 3:31). Although Emerson emphasizes our independence and even distance from one another, then, the payoff for self-reliance is public and social. The scholar finds that the most private and secret of his thoughts turn out to be “the most acceptable, most public, and universally true” (Z: 97). And the great “representative men” Emerson identifies are marked by their influence on the world. Their names-Plato, Moses, Jesus, Luther, Copernicus, even Napoleon-are “ploughed into the history of the world” (Z: 112).

Although self-reliance is central, it is not the only Emersonian virtue. Emerson also praises a kind of trust, and the practice of a “wise skepticism.” There are times, he holds, when we must let go and trust to the nature of the universe: “As the traveler who has lost his way, throws his reins on his horse's neck, and trusts to the instinct of the animal to find his road, so must we do with the divine animal who carries us through this world” (3:15). But the world of flux and conflicting evidence also requires a kind of epistemological and practical flexibility that Emerson calls “wise skepticism” (318). His representative skeptic of this sort is Michel de Montaigne, who as portrayed in Representative Men is no unbeliever, but a man with a strong sense of self, rooted in the earth and common life, whose quest is for knowledge. He wants “a near view of the best game and the chief players; what is best in the planet; art and nature, places and events; but mainly men” (CW4: 91). Yet he knows that life is perilous and uncertain, “a storm of many elements,” the navigation through which requires a flexible ship, “fit to the form of man.” (CW4: 91).

The son of a Unitarian minister, Emerson attended Harvard Divinity School and was employed as a minister for almost three years. Yet he offers a deeply felt and deeply reaching critique of Christianity in the “Divinity School Address,” flowing from a line of argument he establishes in “The American Scholar.” If the one thing in the world of value is the active soul, then religious institutions, no less than educational institutions, must be judged by that standard. Emerson finds that contemporary Christianity deadens rather than activates the spirit. It is an “Eastern monarchy of a Christianity” in which Jesus, originally the “friend of man,” is made the enemy and oppressor of man. A Christianity true to the life and teachings of Jesus should inspire “the religious sentiment” — a joyous seeing that is more likely to be found in “the pastures,” or “a boat in the pond” than in a church. Although Emerson thinks it is a calamity for a nation to lose the capacity to worship (Z: 122) he finds it strange that, given the “famine of our churches” (Z: 117) anyone should attend them. He therefore calls on the Divinity School graduates to breathe new life into the old forms of their religion, to be friends and exemplars to their parishioners, and to remember “that all men have sublime thoughts; that all men value the few real hours of life; they love to be heard; they love to be caught up into the vision of principles” (Z: 124).

Power is a theme in Emerson's early writing, but it becomes especially prominent in such middle- and late-career essays as “Experience,” “Montaigne; or the Skeptic” “Napoleon,” and “Power.” Power is related to action in “The American Scholar,” where Emerson holds that a “true scholar grudges every opportunity of action passed by, as a loss of power” (Z: 92). It is also a subject of “Self-Reliance,” where Emerson writes of each person that “the power which resides in him is new in nature” (CW2:28). In “Experience” Emerson speaks of a life which “is not intellectual or critical, but sturdy” (CW3:294); and in “Power” he celebrates the “bruisers” (P: 372) of the world who express themselves rudely and get their way. The power in which Emerson is interested, however, is more artistic and intellectual than political or military. In a characteristic passage from “Power,” he states:

In history the great moment is, when the savage is just ceasing to be a savage, with all his hairy Pelasgic strength directed on his opening sense of beauty:-and you have Pericles and Phidias,-not yet passed over into the Corinthian civility. Everything good in nature and the world is in that moment of transition, when the swarthy juices still flow plentifully from nature, but their astringency or acridity is got out by ethics and humanity” (P: 375).

Power is all around us, but it cannot always be controlled. It is like “a bird which alights nowhere,” hopping “perpetually from bough to bough” (CW3:34). Moreover, we often cannot tell at the time when we exercise our power that we are doing so: happily we sometimes find that much is accomplished in “times when we thought ourselves indolent” (CW3:28).

At some point in many of his essays and addresses, Emerson enunciates, or at least refers to, a great vision of unity. He speaks in “The American Scholar” of an “original unit” or “fountain of power” (Z: 84), of which each of us is a part. He writes in “The Divinity School Address” that each of us is “an inlet into the deeps of Reason.” And in “Self-Reliance,” the essay that more than any other celebrates individuality, he writes of “the resolution of all into the ever-blessed ONE” (CW 2:40). “The Oversoul” is Emerson's most sustained discussion of “the ONE,” but he does not, even there, shy away from the seeming conflict between the reality of process and the reality of an ultimate metaphysical unity. How can the vision of succession and the vision of unity be reconciled?

Emerson never comes to a clear or final answer. One solution he both suggests and rejects is an unambiguous idealism, according to which a nontemporal “One” or “Oversoul” is the only reality, and all else is illusion. He suggests this, for example, in the many places where he speaks of waking up out of our dreams or nightmares. But he then portrays that to which we awake not simply as an unchanging “ONE,” but as a process or succession: a “growth” or “movement of the soul” (CW2: 189); or a “new yet unapproachable America” (CW3: 259).

Emerson undercuts his visions of unity (as of everything else) through what Stanley Cavell calls his “epistemology of moods.” According to this epistemology, most fully developed in “Experience” but present in all of Emerson's writing, we never apprehend anything “straight” or in-itself, but only under an aspect or mood. Emerson writes that life is “a train of moods like a string of beads,” through which we see only what lies in each bead's focus (CW3: 30). The beads include our temperaments, our changing moods, and the “Lords of Life” which govern all human experience. The Lords include “Succession,” “Surface,” “Dream,” “Reality,” and “Surprise.” Are the great visions of unity, then, simply aspects under which we view the world?

Emerson's most direct attempt to reconcile succession and unity, or the one and the many, occurs in the last essay in the Essays, Second Series , entitled “Nominalist and Realist.” There he speaks of the universe as an “old Two-face…of which any proposition may be affirmed or denied” (CW3: 144). As in “Experience,” Emerson leaves us with the whirling succession of moods. “I am always insincere,” he skeptically concludes, “as always knowing there are other moods” (CW3: 145). But Emerson enacts as well as describes the succession of moods, and he ends “Nominalist and Realist” with the “feeling that all is yet unsaid,” and with at least the idea of some universal truth (CW3: 363).

3. Some Questions about Emerson

Emerson routinely invites charges of inconsistency. He says the world is fundamentally a process and fundamentally a unity; that it resists the imposition of our will and that it flows with the power of our imagination; that travel is good for us, since it adds to our experience, and that it does us no good, since we wake up in the new place only to find the same “ sad self” we thought we had left behind (CW2: 46).

Emerson's “epistemology of moods” is an attempt to construct a framework for encompassing what might otherwise seem contradictory outlooks, viewpoints, or doctrines. Emerson really means to “accept,” as he puts it, “the clangor and jangle of contrary tendencies” (CW3: 36). He means to be irresponsible to all that holds him back from his self-development. That is why, at the end of “Circles,” he writes that he is “only an experimenter…with no Past at my back” (CW2: 188). In the world of flux that he depicts in that essay, there is nothing stable to be responsible to: “every moment is new; the past is always swallowed and forgotten, the coming only is sacred” (CW2: 189).

Despite this claim, there is considerable consistency in Emerson's essays and among his ideas. To take just one example, the idea of the “active soul” — mentioned as the “one thing in the world, of value” in “The American Scholar-is a presupposition of Emerson's attack on “the famine of the churches” (for not feeding or activating the souls of those who attend them); it is an element in his understanding of a poem as “a thought so passionate and alive, that, like the spirit of a plant or an animal, it has an architecture of its own …” (CW3: 6); and, of course, it is at the center of Emerson's idea of self-reliance. There are in fact multiple paths of coherence through Emerson's philosophy, guided by ideas discussed previously: process, education, self-reliance, and the present.

It is hard for an attentive reader not to feel that there are important differences between early and late Emerson: for example, between the buoyant Nature (1836) and the weary ending of “Experience” (1844); between the expansive author of “Self-Reliance” (1841) and the burdened writer of “Fate” (1860). Emerson himself seems to advert to such differences when he writes in “Fate”: “Once we thought positive power was all. Now we learn that negative power, or circumstance, is half” (Z: 369). Is “Fate” the record of a lesson Emerson had not absorbed in his early writing, concerning the multiple ways in which circumstances over which we have no control — plagues, hurricanes, temperament, sexuality, old age-constrain self-reliance or self-development?

“Experience” is a key transitional essay. “Where do we find ourselves?” is the question with which it begins. The answer is not a happy one, for Emerson finds that we occupy a place of dislocation and obscurity, where “sleep lingers all our lifetime about our eyes, as night hovers all day in the boughs of the fir-tree” (CW3: 27). An event hovering over the essay, but not disclosed until its third paragraph, is the death of his five-year old son Waldo. Emerson finds in this episode and his reaction to it an example of an “unhandsome” general character of existence-it is forever slipping away from us, like his little boy.

“Experience” presents many moods. It has its moments of illumination, and its considered judgment that there is an “Ideal journeying always with us, the heaven without rent or seam” (CW3: 41). It offers wise counsel about “skating over the surfaces of life” and confining our existence to the “mid-world.” But even its upbeat ending takes place in a setting of substantial “defeat.” “Up again, old heart!” a somewhat battered voice states in the last sentence of the essay. Yet the essay ends with an assertion that in its great hope and underlying confidence chimes with some of the more expansive passages in Emerson's writing. The “true romance which the world exists to realize,” he states, “will be the transformation of genius into practical power” (CW3: 49).

Despite important differences in tone and emphasis, Emerson's assessment of our condition remains much the same throughout his writing. There are no more dire indictments of ordinary human life than in the early work, “The American Scholar,” where Emerson states that “Men in history, men in the world of today, are bugs, are spawn, and are called ‘the mass’ and ‘the herd.’ In a century, in a millennium, one or two men; that is to say, one or two approximations to the right state of every man” (99). Conversely, there is no more idealistic statement in his early work than the statement in “Fate” that “[t]hought dissolves the material universe by carrying the mind up into a sphere where all is plastic” (377). All in all, the earlier work expresses a sunnier hope for human possibilities, the sense that Emerson and his contemporaries were poised for a great step forward and upward; and the later work, still hopeful and assured, operates under a weight or burden, a stronger sense of the dumb resistance of the world.

Emerson read widely, and gave credit in his essays to the scores of writers from whom he learned. He kept lists of literary, philosophical, and religious thinkers in his journals and worked at categorizing them.

Among the most important writers for the shape of Emerson's philosophy are Plato and the Neoplatonist line extending through Plotinus, Proclus, Iamblichus, and the Cambridge Platonists. Equally important are writers in the Kantian and Romantic traditions (which Emerson probably learned most about from Coleridge's Biographia Literaria ). Emerson read avidly in Indian, especially Hindu, philosophy, and in Confucianism. There are also multiple empiricist, or experience-based influences, flowing from Berkeley, Wordsworth and other English Romantics, Newton's physics, and the new sciences of geology and comparative anatomy. Other writers whom Emerson often mentions are Anaxagoras, St. Augustine, Francis Bacon, Jacob Behmen, Cicero, Goethe, Heraclitus, Lucretius, Mencius, Pythagoras, Schiller, Thoreau, August and Friedrich Schlegel, Shakespeare, Socrates, Madame de Staël and Emanuel Swedenborg.

Emerson's works were well known throughout the United States and Europe in his day. Nietzsche read German translations of Emerson's essays, copied passages from “History” and “Self-Reliance” in his journals, and wrote of the Essays : that he had never “felt so much at home in a book.” Emerson's ideas about “strong, overflowing” heroes, friendship as a battle, education, and relinquishing control in order to gain it, can be traced in Nietzsche's writings. Other Emersonian ideas-about transition, the ideal in the commonplace, and the power of human will permeate the writings of such classical American pragmatists as William James and John Dewey; and his philosophy is a primary source for Stanley Cavell's contemporary writing on “moral perfectionism.”

Bibliography

(See Chronology for original dates of publication.)

- Allen, Gay Wilson, 1981, Waldo Emerson , New York: Viking Press

- Bishop, Jonathan, 1964, Emerson on the Soul , Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

- Buell, Lawrence, 2003, Emerson , Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

- Cameron, Sharon, 2007, Impersonality , Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- Carpenter, Frederick Ives, 1930, Emerson and Asia , Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

- Cavell, Stanley, 1981, “Thinking of Emerson” and “An Emerson Mood,” in The Senses of Walden, An Expanded Edition, San Francisco: North Point Press

- –––, 1988, In Quest of the Ordinary: Lines of Skepticism and Romanticism , Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- –––, 1990, “Introduction” and “Aversive Thinking,” in Conditions Handsome and Unhandsome: The Constitution of Emersonian Perfectionism , Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- –––, 2004, Emerson's Transcendental Etudes , Stanford: Stanford University Press

- Conant, James, 1997, “Emerson as Educator,” ESQ: A Journal of the American Renaissance , 43: 181–206

- Ellison, Julie, 1984, Emerson's Romantic Style , Princeton: Princeton University Press

- Firkins, Oscar W., 1915, Ralph Waldo Emerson , Boston: Houghton Mifflin

- Goodman, Russell B., 1990a, American Philosophy and the Romantic Tradition , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Chapter 2

- –––, 1990b, “East-West Philosophy in Nineteenth Century America: Emerson and Hinduism,” Journal of the History of Ideas , 51(4): 625–45

- –––, 1997, “Moral Perfectionism and Democracy in Emerson and Nietzsche,” ESQ: A Journal of the American Renaissance , 43: 159–80

- –––, 2004, “The Colors of the Spirit: Emerson and Thoreau on Nature and the Self,” Nature in American Philosophy , ed. Jean De Groot, Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1–18.

- –––, 2008, “Emerson, Romanticism, and Classical American Pragmatism,” The Oxford Handbook of American Philosophy , ed. Cheryl Misak, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 19–37.

- Holmes, Oliver Wendell, 1885, Ralph Waldo Emerson , Boston: Houghton Mifflin

- Lysaker, John, 2008, Emerson and Self-Culture , Indianapolis: Indiana University Press

- Matthiessen, F. O., 1941, American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman . New York: Oxford University Press

- Packer, B. L., 1982, Emerson's Fall , New York: Continuum

- –––, 2007, The Transcendentalists , Athens: University of Georgia Press.

- Poirier, Richard, 1987, The Renewal of Literature: Emersonian Reflections , New York: Random House

- –––, 1992, Poetry and Pragmatism , Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press

- Porte, Joel, and Morris, Saundra (eds.), 1999, The Cambridge Companion to Ralph Waldo Emerson . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Richardson, Robert D. Jr., 1995, Emerson: The Mind on Fire , Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press

- Sacks, Kenneth, 2003, Understanding Emerson: “The American Scholar” and His Struggle for Self-Reliance , Princeton: Princeton University Press

- Versluis, Arthur, 1993, American Transcendentalism and Asian Religions , New York: Oxford University Press

- Whicher, Stephen, 1953, Freedom and Fate: An Inner Life of Ralph Waldo Emerson , Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

- Guide to Resources on Emerson (maintained by Jone Johnson Lewis)

Anaxagoras | Augustine, Saint | Bacon, Francis | Cambridge Platonists | -->Cicero --> | -->Dewey, John --> | Heraclitus | -->Iamblichus --> | James, William | Lucretius | Mencius | Nietzsche, Friedrich | Plotinus | Pythagoras | -->Schiller, Friedrich --> | Schlegel, Friedrich | Socrates | transcendentalism

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson was an American Transcendentalist poet, philosopher and essayist during the 19th century. One of his best-known essays is "Self-Reliance.”

(1803-1882)

Who Was Ralph Waldo Emerson?

In 1821, Ralph Waldo Emerson took over as director of his brother’s school for girls. In 1823, he wrote the poem "Good-Bye.” In 1832, he became a Transcendentalist, leading to the later essays "Self-Reliance" and "The American Scholar." Emerson continued to write and lecture into the late 1870s.

Early Life and Education

Ralph Waldo Emerson was born on May 25, 1803, in Boston, Massachusetts. He was the son of William and Ruth (Haskins) Emerson; his father was a clergyman, as many of his male ancestors had been. He attended the Boston Latin School, followed by Harvard University (from which he graduated in 1821) and the Harvard School of Divinity. He was licensed as a minister in 1826 and ordained to the Unitarian church in 1829.

Emerson married Ellen Tucker in 1829. When she died of tuberculosis in 1831, he was grief-stricken. Her death, added to his own recent crisis of faith, caused him to resign from the clergy.

Travel and Writing

In 1832 Emerson traveled to Europe, where he met with literary figures Thomas Carlyle, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth. When he returned home in 1833, he began to lecture on topics of spiritual experience and ethical living. He moved to Concord, Massachusetts, in 1834 and married Lydia Jackson in 1835.

American Transcendentalism

In the 1830s Emerson gave lectures that he afterward published in essay form. These essays, particularly “Nature” (1836), embodied his newly developed philosophy. “The American Scholar,” based on a lecture that he gave in 1837, encouraged American authors to find their own style instead of imitating their foreign predecessors.

Emerson became known as the central figure of his literary and philosophical group, now known as the American Transcendentalists. These writers shared a key belief that each individual could transcend, or move beyond, the physical world of the senses into deeper spiritual experience through free will and intuition. In this school of thought, God was not remote and unknowable; believers understood God and themselves by looking into their own souls and by feeling their own connection to nature.

The 1840s were productive years for Emerson. He founded and co-edited the literary magazine The Dial , and he published two volumes of essays in 1841 and 1844. Some of the essays, including “Self-Reliance,” “Friendship” and “Experience,” number among his best-known works. His four children, two sons and two daughters, were born in the 1840s.

Later Work and Life

Emerson’s later work, such as The Conduct of Life (1860), favored a more moderate balance between individual nonconformity and broader societal concerns. He advocated for the abolition of slavery and continued to lecture across the country throughout the 1860s.

By the 1870s the aging Emerson was known as “the sage of Concord.” Despite his failing health, he continued to write, publishing Society and Solitude in 1870 and a poetry collection titled Parnassus in 1874.

Emerson died on April 27, 1882, in Concord. His beliefs and his idealism were strong influences on the work of his protégé Henry David Thoreau and his contemporary Walt Whitman, as well as numerous others. His writings are considered major documents of 19th-century American literature, religion and thought.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Birth Year: 1803

- Birth date: May 25, 1803

- Birth State: Massachusetts

- Birth City: Boston

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Ralph Waldo Emerson was an American Transcendentalist poet, philosopher and essayist during the 19th century. One of his best-known essays is "Self-Reliance.”

- Journalism and Nonfiction

- Fiction and Poetry

- Education and Academia

- Writing and Publishing

- Astrological Sign: Gemini

- Boston Public Latin School

- Harvard University

- Harvard Divinity School

- Death Year: 1882

- Death date: April 27, 1882

- Death State: Massachusetts

- Death City: Concord

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

- Nothing great was ever achieved without enthusiasm.

- The only reward of virtue is virtue; the only way to have a friend is to be one.

- Nature never hurries: atom by atom, little by little, she achieves her work.

Philosophers

Francis Bacon

Auguste Comte

Charles-Louis de Secondat

Saint Thomas Aquinas

William James

John Stuart Mill

Jean-Paul Sartre

Philosophy Break Your home for learning about philosophy

Introductory philosophy courses distilling the subject's greatest wisdom.

Reading Lists

Curated reading lists on philosophy's best and most important works.

Latest Breaks

Bite-size philosophy articles designed to stimulate your brain.

Ralph Waldo Emerson The Best 5 Books to Read

R alph Waldo Emerson (1803 - 1882) was a philosopher and essayist perhaps best known for spearheading American Transcendentalism, a philosophical movement that emphasizes the power of individualism, self-reliance, and the natural world.

One of the key hallmarks of the Transcendentalist movement, which notably included Emerson, Margaret Fuller, and Henry David Thoreau (see our reading list of Thoreau’s best books here ), is its celebration of the supremacy — even divinity — of nature.

Divinity is not locked in a distant heaven, say transcendentalists; it is accessible right here in the company of the natural world.

We are thus at our best not when we conform to voices outside ourselves, but when we follow the voice within — the glimmering insight, the “immense intelligence” of our natural intuition and instincts.

Society on this view is seen as a corrupting force — it takes us away from our natural wisdom.

As unique individuals, we should not conform to generic belief systems or conventions, Emerson writes, but instead “enjoy an original relation to the universe.”

Emerson offers the beginnings of a path for how we might resist the pressures of society in his famous 1841 essay, Self-Reliance (read my Self-Reliance summary and analysis here ), which features in the collection below.

A famous passage from Emerson’s Self-Reliance that encapsulates the theme of much of his work runs as follows:

You will always find those who think they know what is your duty better than you know it. It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox:

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

This reading list consists of the best books by and about Ralph Waldo Emerson.

After reading some of the books on this list, you’ll understand why this brilliant thinker was heralded by the great German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche as “the most gifted of the Americans” (see my reading list of Nietzsche’s best books here ), and remains so celebrated to this day.

Let’s dive in!

1. Nature and Selected Essays, by Ralph Waldo Emerson

BY RALPH WALDO EMERSON

Nature was Emerson’s first book, and it set out the core principles for much of his (and Transcendentalist) thought.

Published in 1836 following the traumatic death of his first wife, Nature features Emerson at his sermonic best. Having left the Church, Emerson aimed to deliver secular lectures that nevertheless contained an almost religious power of their own. Nature is his first attempt at doing so with the written word — and in this regard it’s an undisputed success.

Emerson meditates on the power and beauty of nature and our profound, unbreakable connection to it. He writes:

Nature always wears the colors of the spirit. To a man laboring under calamity, the heat of his own fire hath sadness in it.

The essence of nature is integral to the essence of ourselves, and Emerson implores us to both explore and live in harmony with it.

If you’re interested in Emerson and Transcendentalism, there’s no better book to start with. As well as the book-length Nature essay, Nature and Selected Essays also includes many other of Emerson’s most acclaimed essays, including Self-Reliance, The Poet, and The American Scholar.

2. The Annotated Emerson, by Ralph Waldo Emerson and David Mikics

The Annotated Emerson

While Emerson is regarded as one of America’s greatest writers, his luxurious 19th-century prose can appear a little dense to the modern eye. Hence The Annotated Emerson : a brilliant book — published in 2012 — that contextualizes, illustrates, and discusses Emerson’s most important works.

Presenting some of Emerson’s most significant essays (including Nature, Self-Reliance, and more), the scholar David Mikics provides brilliant commentary throughout, drawing on Emerson’s journal entries and providing biographical details to supplement the work and bring Emerson’s writing to life.

For those seeking a deeper understanding of Emerson’s work, The Annotated Emerson is highly recommended.

3. Ralph Waldo Emerson: Essays and Lectures, by Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson: Essays and Lectures

If you’re looking for a one-stop shop for all things Emerson, then look no further than Ralph Waldo Emerson: Essays and Lectures , published in 1983.

This anthology contains all of Emerson’s essays and lectures, as well as a wealth of helpful contextual and biographical detail.

At 1150 pages, this anthology’s a beast — but you won’t need another!

4. Emerson: The Mind on Fire, by Robert D. Richardson

Emerson: The Mind on Fire

BY ROBERT D. RICHARDSON

If you’re looking to learn more about the life Emerson lived and the events that shaped his work, Robert D. Richardson’s Emerson: The Mind on Fire is a fantastic biography, excellently researched and engagingly written.

In 100 bite-size chapters, Richardson lovingly weaves the story of Emerson’s intellectual development, his spearheading of the Transcendentalist movement (and often fraught interpersonal relationships with its members), his legacy as one of the greatest figureheads of American literature, and his lasting impact on the American psyche.

If you’re interested in Emerson, this autobiography is an essential addition to your bookshelf.

5. Emerson in His Journals, by Joel Porte

Emerson in His Journals

BY JOEL PORTE

For much of his long and fascinating life, Emerson kept a detailed journal. In 1984, Emerson scholar Joel Porte edited Emerson’s vast collection of journal entries to produce Emerson in His Journals , a book that should delight fans of Emerson and his work.

In these pages, we are granted intimate access into some of the major events in Emerson’s life — like his complex relationship with fellow Transcendentalist Margaret Fuller — from Emerson’s own perspective .

We see a side to Emerson that he would never expose in his published writings, rendering Emerson in His Journals an enthralling addition for hardcore Emerson scholars.

Further reading

Are there any other books you think should be on this list? Let us know via email or drop us a message on Twitter or Instagram .

In the meantime, why not explore more of our reading lists on the best philosophy books :

View All Reading Lists

Essential Philosophy Books by Subject

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free):

About the author.

Jack Maden Founder Philosophy Break

Having received great value from studying philosophy for 15+ years (picking up a master’s degree along the way), I founded Philosophy Break in 2018 as an online social enterprise dedicated to making the subject’s wisdom accessible to all. Learn more about me and the project here.

If you enjoy learning about humanity’s greatest thinkers, you might like my free Sunday email. I break down one mind-opening idea from philosophy, and invite you to share your view.

Subscribe for free here , and join 11,000+ philosophers enjoying a nugget of profundity each week (free forever, no spam, unsubscribe any time).

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 11,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (50+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Each philosophy break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your curiosity.

Enrich Your Personal Philosophy with these 6 Major Philosophies for Life

17 -MIN BREAK

Heidegger On Being Authentic in an Inauthentic World

4 -MIN BREAK

Iris Murdoch on the Morality of Attention, and the Hostile Mother-in-Law

6 -MIN BREAK

The Apollonian and Dionysian: Nietzsche On Art and the Psyche

14 -MIN BREAK

View All Breaks

PHILOSOPHY 101

- What is Philosophy?

- Why is Philosophy Important?

- Philosophy’s Best Books

- About Philosophy Break

- Support the Project

- Instagram / Threads / Facebook

- TikTok / Twitter

Philosophy Break is an online social enterprise dedicated to making the wisdom of philosophy instantly accessible (and useful!) for people striving to live happy, meaningful, and fulfilling lives. Learn more about us here . To offset a fraction of what it costs to maintain Philosophy Break, we participate in the Amazon Associates Program. This means if you purchase something on Amazon from a link on here, we may earn a small percentage of the sale, at no extra cost to you. This helps support Philosophy Break, and is very much appreciated.

Access our generic Amazon Affiliate link here

Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy

© Philosophy Break Ltd, 2024

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson was one of the titans of American Romanticism. Obsessed with freedom, he developed a conception of political democracy that motivated generations of political philosophers. Equally obsessed with the inherent value of nature, he laid the intellectual groundwork for the conservation movements that would blossom in the late 19 th century with the establishment of America’s National Parks.

Emerson was always suspicious of philosophy, particularly of the professional philosopher’s habit of looking down on common sense. He was also unpersuaded by the notion of philosophical truth as something value-free, abstracted from the human domains of power, emotion, and desire. Philosophers, Emerson argued, are still human and subject to the same historical and cultural forces that shape all human thought and action.

For Emerson, the goal of philosophy was not to seek absolute truth but to promote human freedom. And his conception of freedom was a peculiarly American one: intensely individualistic, iconoclastic, and democratic. This was not the aristocratic freedom of Kant, who had argued (persuasively, to many) that freedom consisted in the capacity to obey the dictates of reason. For Emerson, reason was only one more human creative endeavor alongside the arts, literature, and the enjoyment of natural beauty. Emerson might be thought of as the first in a longstanding tradition of American anti-philosophers.

Ralph Waldo Emerson was raised in a well-to-do family in Boston, MA. His father was a Unitarian minister and prominent public figure in post-Revolution Boston, and his religious upbringing influenced the development of his transcendentalist thinking (see next section). Like the sons of other wealthy Bostonians at the time, Emerson attended Harvard, ultimately graduating with a degree from the Divinity School alongside his Bachelor’s. He worked for a few years as a pastor, but was disappointed with the church. Instead of seeking knowledge of God, he wrote, “we worship the dead forms of our forefathers.” In abandoning the ministry, Emerson lived out one of his most cherished principles –rejecting tradition whenever it conflicts with personal conscience . After leaving the ministry, he worked as a lecturer and traveling scholar, mostly in New England but also in Europe and the western states.

Tragically, Emerson’s mind deteriorated as he aged and he lived for several years with only a limited ability to speak or remember things. But his books and essays had made him a global celebrity and he continued to travel the world, meeting fellow scholars and public figures, even though he could no longer carry on much of an intellectual conversation. He died in 1882 at the age of 78.

Emerson’s Ideas

Self-reliance.

The title of one of Emerson’s most well-known essays captures the spirit of his philosophy: self-reliance. The essay is part political manifesto, part spiritual guidebook, and part epistemological treatise. In all four dimensions, its defining characteristic is its insistence on the self as the wellspring of human goodness. Politically, it envisions a system in which human individuals are free to create the institutional conditions in which they live. Cornel West refers to this as “creative democracy” and praises the idea while simultaneously criticizing its blindness to the historical realities of politics. Spiritually, it invokes an idea of the self as a wellspring of spiritual strength and moral clarity. It also views self-knowledge as the most important form of knowledge, perhaps a necessity for clear knowledge of anything in the outside world. (This is the epistemological angle.) If we think of the mind as an instrument for observation, then of course our first task should be to understand the instrument – what sort of scientist would try to use a microscope without first understanding how it works?

Though it has inspired generations of American individualists, Self-Reliance has also been roundly criticized for being unrealistic, particularly in its politics. Human political projects are always the product of collective effort, in which individual introspection and self-seeking are subordinated for the betterment of the whole society. Emerson himself is a product of this sort of collective politics: his political freedoms came from the labor of the American revolutionaries, his literary abilities came from the labor of teachers and university administrators, and the food that fueled his pen came from the labor of farmers and grocers. Given how tightly Emerson was enmeshed in the skein of human connection, is he hypocritical for exhorting humans to pursue absolute individuality?

Of course, Emerson might agree with the claim that humans are inherently bound into communities, and still maintain that individualism is the best way of life as far as it’s possible to achieve it. More fundamentally, he might argue that collective political efforts can be a way of exploring the self – though at every stage in this process one would have to maintain clarity on which ideas belong authentically to the self, and which are inauthentic projections of the group. Not an easy thing to do!

Transcendentalism

Transcendentalism is an eclectic philosophical and spiritual movement influenced by European Romanticism (with its embrace of nature and the emotions against the Enlightenment’s emphasis on reason and civilization), by American democratic culture, and by a mystical, culturally decontextualized reading of Hindu scriptures. Emerson wasn’t the founder of transcendental philosophy, but he was the person most responsible for introducing it into American philosophy.

Emerson’s transcendentalism was distinct in its extreme individualism. Other transcendentalists embraced the role of communities in fostering the Romantic spirit, and their movement was closely intertwined with the growing Unitarian church. Emerson, on the other hand, was never satisfied with this sort of collectivist transcendentalism. He believed individuals needed only to look within themselves for spiritual guidance, and that any outside influence would merely get in the way.

It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.

Fierce individualist though he was, Emerson did not tell his readers to abandon human company and run off into the woods to live alone. He argued that independence – “self-reliance” – is not a physical state of being but a frame of mind. To be truly independent is not to be alone all the time, but to be among others without becoming them.

Standing on the bare ground, — my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space, — all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.

Emerson’s individualism was never about solipsism or self-obsession (what he here calls “mean egotism”). Although some readers take Emerson’s philosophy as an excuse to be dismissive of the needs of others, that isn’t what he advocated. The image of a “transparent eye-ball” evokes an idea of a self that knows and perceives yet is empty. Paradoxically, the pursuit of solitude (and sensory contact with nature) ultimately yields a dissolution of the ego into the universal whole.

In Pop Culture

Parks and recreation.

There’s a lot of Emerson in the work of Nick Offerman, who plays Ron Swanson on Parks and Recreation . His book, Paddle Your Own Canoe hits two of Emerson’s main themes: self-reliance and an appreciation for nature. Offerman discusses this kind of thing frequently in his standup routines, and a lot of that fierce individualism comes through in his portrayal of Ron Swanson.

a. American

c. Australian

d. Canadian

a. Paddle Your Own Canoe

b. The American Experience

c. Self-Reliance

d. All of these are famous Emerson essays

a. Epistemology

b. Politics

c. Spirituality

d. All of the above

a. A farmer

b. A builder

c. A minister

d. A teacher

(92) 336 3216666

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson was born on 25 May 1803 and died on 27 April 1882. He was an American lecturer, essayist, poet, and philosopher. In the mid-nineteenth century, he was the founding member of the transcendentalist movement in America. He advocated individualism against the pressure of society and became a clairvoyant critic of it. He wrote dozens of essays and delivered more than 1500 public lectures across the country to disseminate his thoughts.

Emerson boycotted contemporary social and religious beliefs. In 1836, he formulated his philosophy of transcendentalism in his most famous essay, “Nature.” After the publication of the essay, he delivered a speech in 1837, titled “The American Scholar.” Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. regarded this speech as America’s “intellectual Declaration of Independence.” Emerson was also an important member of the Romantic movement of America. A great number of writers, thinkers, and poets have been greatly influenced by his philosophy and works.

A Short Biography of Ralph Waldo Emerson

Emerson was born in Boston, Massachusetts, to the Rev. William Emerson and Ruth Haskins. His father was a Unitarian minister. Ralph had four siblings: Edward, William, Charles, and Robert Bulkeley. They survived into adulthood with Ralph Waldo, whereas the other three – Phebe, Mary Caroline, and John Clarke – died in childhood. The ancestry of Emerson was completely English. They had been living in New England since the colonial period started.

On 12 May 1811, the father of Emerson died because of stomach cancer. At that time, Emerson was almost eight years old. With the help of other women of the family, Emerson’s mother raised him. He had been greatly influenced by his aunt Mary Moody Emerson. She had often been living with his family and was in touch with Emerson until she died in 1863.

In 1812, at the age of nine, Emerson started his schooling at the Boston Latin School. He then went to Harvard College in 1817 and was appointed as the messenger for the president. He was required to raise negligent students and deliver messages to faculty. In the same years, Emerson started writing a list of the books he had already read, and in a series of notebooks, he started a journal “Wide World.”

To cover his expenses, he sought some jobs that included a waiter for Junior Commons and occasional teacher at Waltham, Massachusetts. When he was in senior year, he started using his middle name, “Waldo.” He also served the Class Poet and presented his original poem on the Class Day, at the age of 18. He graduated in September 1821.

In 1826, Emerson’s health was getting poor. He decided to go to a place of a warmer climate. First, he went to Charleston; however, the weather was cold, which does not suit him. Then he went to St. Augustine, Florida. Over there, he would take long walks on the beach and start writing poetry. He also became a good friend of Prince Achille Murat, the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, in St. Augustine. Murat and Emerson would often discuss society, religion, government, and philosophy. Emerson regarded Murat as the most significant influencer and intellectual educator.

In 1829, he married Ellen Tucker. However, she was diagnosed with Tuberculosis and died in 1831. Her death made him skeptical of faith, and he resigned from his job of the clergy.

He traveled to Europe in 1832. There he met with well-known literary figures William Wordsworth, S.T Coleridge, and Thomas Carlyle. He returned in 1833 and started delivering lectures of spiritualism; in 1834, he shifted to Concord, Massachusetts, and married Lydia in 1835.

In the 1830s, he delivered some lectures that he later published in the essay form. These essays were the basis of his transcendental philosophy. Moreover, his lecture “The American Scholar” in 1837 motivated American authors to be more distinctive in their own art than following the foreigners.

In the 1840s, he founded his own magazine, “The Dial,” and published his two volumes of essays. The most well-known essay was published in these years. Moreover, his four children were also born in these years. In the 1850s, he advocated the idea of nonconformity and abolition of slavery. In the 1870s, Emerson was well known as “the sage of Concord.” He died in 1882 in concord.

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Writing Style

In the mid-nineteenth century and twentieth century, the works of Emerson were the most read and frequently quoted. His works were based on the entirely new ideas of transcendentalism and mysticism that captured the attention of the readers of his time and audience of his lectures. In fact, his ideas also continue to influence the readers of the 21 st century. In his writings, Emerson focuses on his idealistic philosophies and the true relationship of man with God and nature.

Emerson’s rich expression and keen observation made him one of the best prose writers of the century. Though he, most of the time, emphasizes on the obscure and complex concepts, his writing keeps directness , clarity , and careful development of new ideas. He elucidates difficult ideas with metaphor and analogy . He moves his ideas from the perceptions of an individual to the broad generalization that bends the readers.

The way Emerson constructs his sentences and phases engages the readers as if he has not written it on the piece of paper but is speaking it to them. This impression is strengthened by his use of common words and maxims in his works. His language and emotions attained the peak of expression with his rhetorical style .

His poetry is also based on the same major themes as found in his essays and speeches. The crescendos and cadences in the essays parallel the rise and fall of the intensity of emotions in the poetry. His poetry is stylistically unique and different from the poetry of contemporary poets.

Various things greatly influenced Emerson’s writing. The most significant among them were Unitarianism, New England Calvinism, the Neo-Platonists, Plato’s writings, Carlyle, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Swedenborg, Montaigne, and eastern sacred texts. However, his ideas he put in his lectures and essays were totally his own what we now called “American Transcendentalism.”

Characteristics of Emerson’s work

He talks about the truth of man, God, nature, and existence in most of his works. He considers man as an expression of God, thus elevating the dignity and significance of man. In his essay “Nature,” he writes that the “Supreme Being,” i.e., God is the spirit who does not create nature around men.

However, he put nature into view through men, just like the new branches and tree of the trees put forth by the life of the tree through an old pore. The way plants breathe upon the bosom of Earth, a man also breathes on the “bosom of God.” Man is sustained by consistent cascades, and pulls, at his need, unlimited power. Who can put restrictions on the potentials of a man? He says that it is the man who can get access to the mind of the Creator; even he himself is the creator with some restrictions.

Emerson’s outlook was highly humanistic and challenged the beliefs of the Calvinistic tradition of New England that formed the remote sovereignty of God.

Emerson not only made humanity to believe in the oneness of God but made them obey him without questionings. He was in view that all men are equal in worth and capacity. To measure the value of an individual based on his social status and human hierarchies is baseless, Emerson says. In his essay “Nature” (Chapter VIII; Prospects), Emerson wrote that it is either Adam or Caesar; everyone is equal.

Whatever Adam had, and whatever Caesar could do, an ordinary man can also have it and do it. Adam would call his house earth and heaven, whereas Caesar would call it Rome, you can have your house, what if it is called as Cobbler’s trade; it does not matter how much amount of and you have, or of what worth, if you have your own dominion, it is as worth as theirs though it does not have a fine name. Therefore, build your own world.

The notion of equality among men and the idea that God equally creates all men, thus all processes divinity is a degree, were strongly appealing to the contemporary readers as they are in the 21 st century. The idea of democracy that Emerson gave in his works is more basic and does not promote any social or political system.

Moreover, it reinforced the claim of the individual to be respected by philosophy; therefore, highlighting the extraordinary abilities of humans in the framework of the whole of humanity. For Emerson, those men who had achieved peculiarity in some ways are the representatives of human abilities. In his speech “The American Scholar,” he asserts that the building up of a man is the main initiative of the world for magnitude and grandeur.

He says that the personal life of the individual should be his more renowned dominion suggesting to be harsh for its enemy; however, to influence his friends, it must be sweet and serene, that any monarchy in history. If one man is perceived rightly, it comprehends the nature of all men. “Each philosopher, each bard, each actor, has only done for me, as by a delegate, what one day I can do for myself.”

He was greatly charmed by both positive and negative characteristics of various extraordinary individuals . His collection of “Representative Essay” contains the lectures and essays on Plato, Montaigne, Swedenborg, Shakespeare, Goethe, and Napoleon.

However, he does not focus only on the positive attributes but on the negative as well, suggesting the abilities and aspirations of the whole of humanity. In his essay “Uses of Great Men,” he writes that the people whom we call masses and common men; in fact, they are not the common man. Every man has hidden talents, and true art is only possible if a man has strong beliefs that somewhere his art will be admired at best. “Fair play, and an open field, and freshest laurels to all who have won them!”

However, heaven has reserved an equal possibility for every creature. Each is uncomfortable till he has formed his reserved gleam unto the “concave sphere,” and also witnessed his ability in its last decency and adulation.

He also talks about the restriction imposed on an individual by society, civilization, materialism, and institutions that greatly affect the abilities of individuals. He says that the limitations imposed by these institutions do not work to highlight the distinctiveness among men. However, they suppress the self-realization of the individual.

Emerson’s view of the essential link between the man, God, and nature made him exalt the status of the individual.

According to him, man is more capable of insight, imagination, and morality; however, his abilities stem from his close association with a greater, sophisticated entity than himself.

In the essay “The Over-Soul,” Emerson focuses on his mans’ indispensable harmony with the divine that man is a spiritual being. The way there is “no ceiling” or “screen” between the heavens and the heads of man, there is no wall or stopping point where we can point out starting and ending points of effect, the man, and God, the cause. The walls have been removed, and man is lying open to the spiritual nature, which are the attributes of God.

Emerson also talks about the inconsistency between daily life experiences and philosophy, particularly in his essay “Experience.” In his career and writings, he examined a range of subjects. It includes poetry and poets, history, education, art, society, reforms, politics, and the individual’s life. He examined all these subjects in the framework of transcendentalism.

Works Of Ralph Waldo Emerson

Emerson writes a poem about old friendships and about friendships lost.

A ruddy drop of manly blood The surging sea outweighs, The world uncertain comes and goes, The lover rooted stays. I fancied he was fled, And, after many a year, Glowed unexhausted kindliness Like daily sunrise there. My careful heart was free again, — O friend, my bosom said, Through thee alone the sky is arched, Through thee the rose is red, All things through thee take nobler form, And look beyond the earth, And is the mill-round of our fate A sun-path in thy worth. Me too thy nobleness has taught To master my despair; The fountains of my hidden life Are through thy friendship fair.

W e have a great deal more kindness than is ever spoken. Maugre all the selfishness that chills like east winds the world, the whole human family is bathed with an element of love like a fine ether. How many persons we meet in houses, whom we scarcely speak to, whom yet we honor, and who honor us! How many we see in the street, or sit with in church, whom, though silently, we warmly rejoice to be with! Read the language of these wandering eye-beams. The heart knoweth.

The effect of the indulgence of this human affection is a certain cordial exhilaration. In poetry, and in common speech, the emotions of benevolence and complacency which are felt towards others are likened to the material effects of fire; so swift, or much more swift, more active, more cheering, are these fine inward irradiations. From the highest degree of passionate love, to the lowest degree of good-will, they make the sweetness of life.

Our intellectual and active powers increase with our affection. The scholar sits down to write, and all his years of meditation do not furnish him with one good thought or happy expression; but it is necessary to write a letter to a friend, — and, forthwith, troops of gentle thoughts invest themselves, on every hand, with chosen words. See, in any house where virtue and self-respect abide, the palpitation which the approach of a stranger causes. A commended stranger is expected and announced, and an uneasiness betwixt pleasure and pain invades all the hearts of a household. His arrival almost brings fear to the good hearts that would welcome him. The house is dusted, all things fly into their places, the old coat is exchanged for the new, and they must get up a dinner if they can. Of a commended stranger, only the good report is told by others, only the good and new is heard by us. He stands to us for humanity. He is what we wish. Having imagined and invested him, we ask how we should stand related in conversation and action with such a man, and are uneasy with fear. The same idea exalts conversation with him. We talk better than we are wont. We have the nimblest fancy, a richer memory, and our dumb devil has taken leave for the time. For long hours we can continue a series of sincere, graceful, rich communications, drawn from the oldest, secretest experience, so that they who sit by, of our own kinsfolk and acquaintance, shall feel a lively surprise at our unusual powers. But as soon as the stranger begins to intrude his partialities, his definitions, his defects, into the conversation, it is all over. He has heard the first, the last and best he will ever hear from us. He is no stranger now. Vulgarity, ignorance, misapprehension are old acquaintances. Now, when he comes, he may get the order, the dress, and the dinner, — but the throbbing of the heart, and the communications of the soul, no more.

What is so pleasant as these jets of affection which make a young world for me again? What so delicious as a just and firm encounter of two, in a thought, in a feeling? How beautiful, on their approach to this beating heart, the steps and forms of the gifted and the true! The moment we indulge our affections, the earth is metamorphosed; there is no winter, and no night; all tragedies, all ennuis, vanish, — all duties even; nothing fills the proceeding eternity but the forms all radiant of beloved persons. Let the soul be assured that somewhere in the universe it should rejoin its friend, and it would be content and cheerful alone for a thousand years.

I awoke this morning with devout thanksgiving for my friends, the old and the new. Shall I not call God the Beautiful, who daily showeth himself so to me in his gifts? I chide society, I embrace solitude, and yet I am not so ungrateful as not to see the wise, the lovely, and the noble-minded, as from time to time they pass my gate. Who hears me, who understands me, becomes mine, — a possession for all time. Nor is nature so poor but she gives me this joy several times, and thus we weave social threads of our own, a new web of relations; and, as many thoughts in succession substantiate themselves, we shall by and by stand in a new world of our own creation, and no longer strangers and pilgrims in a traditionary globe. My friends have come to me unsought. The great God gave them to me. By oldest right, by the divine affinity of virtue with itself, I find them, or rather not I, but the Deity in me and in them derides and cancels the thick walls of individual character, relation, age, sex, circumstance, at which he usually connives, and now makes many one. High thanks I owe you, excellent lovers, who carry out the world for me to new and noble depths, and enlarge the meaning of all my thoughts. These are new poetry of the first Bard, — poetry without stop, — hymn, ode, and epic, poetry still flowing, Apollo and the Muses chanting still. Will these, too, separate themselves from me again, or some of them? I know not, but I fear it not; for my relation to them is so pure, that we hold by simple affinity, and the Genius of my life being thus social, the same affinity will exert its energy on whomsoever is as noble as these men and women, wherever I may be.

I confess to an extreme tenderness of nature on this point. It is almost dangerous to me to "crush the sweet poison of misused wine" of the affections. A new person is to me a great event, and hinders me from sleep. I have often had fine fancies about persons which have given me delicious hours; but the joy ends in the day; it yields no fruit. Thought is not born of it; my action is very little modified. I must feel pride in my friend's accomplishments as if they were mine, — and a property in his virtues. I feel as warmly when he is praised, as the lover when he hears applause of his engaged maiden. We over-estimate the conscience of our friend. His goodness seems better than our goodness, his nature finer, his temptations less. Every thing that is his, — his name, his form, his dress, books, and instruments, — fancy enhances. Our own thought sounds new and larger from his mouth.