Generate accurate APA citations for free

- Knowledge Base

- APA Style 7th edition

- How to create an APA Style appendix

How to Create an APA Style Appendix | Format & Examples

Published on October 16, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on August 9, 2022.

An appendix is a section at the end of an academic text where you include extra information that doesn’t fit into the main text. The plural of appendix is “appendices.”

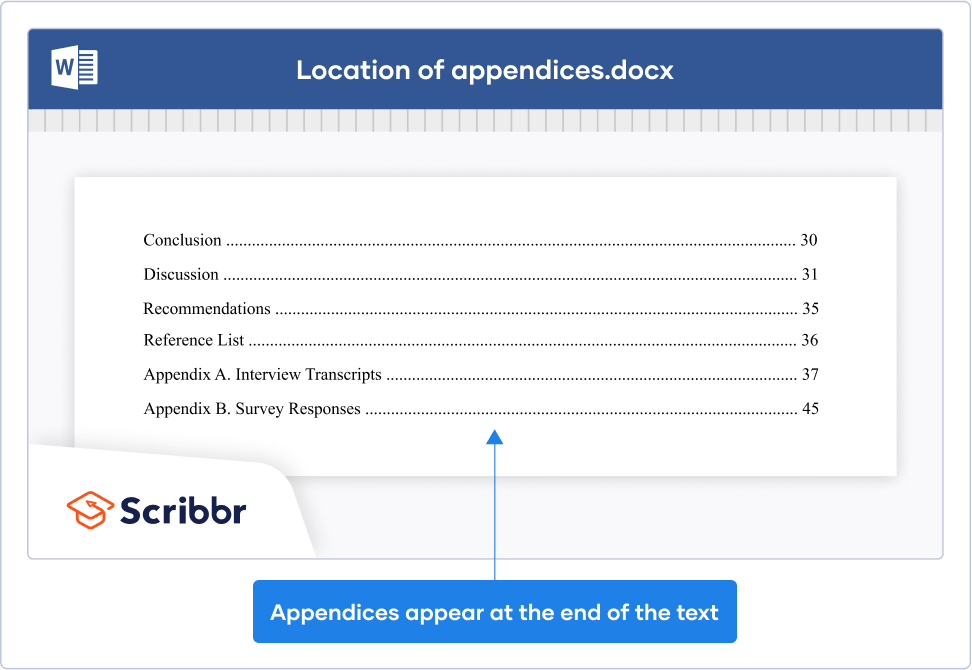

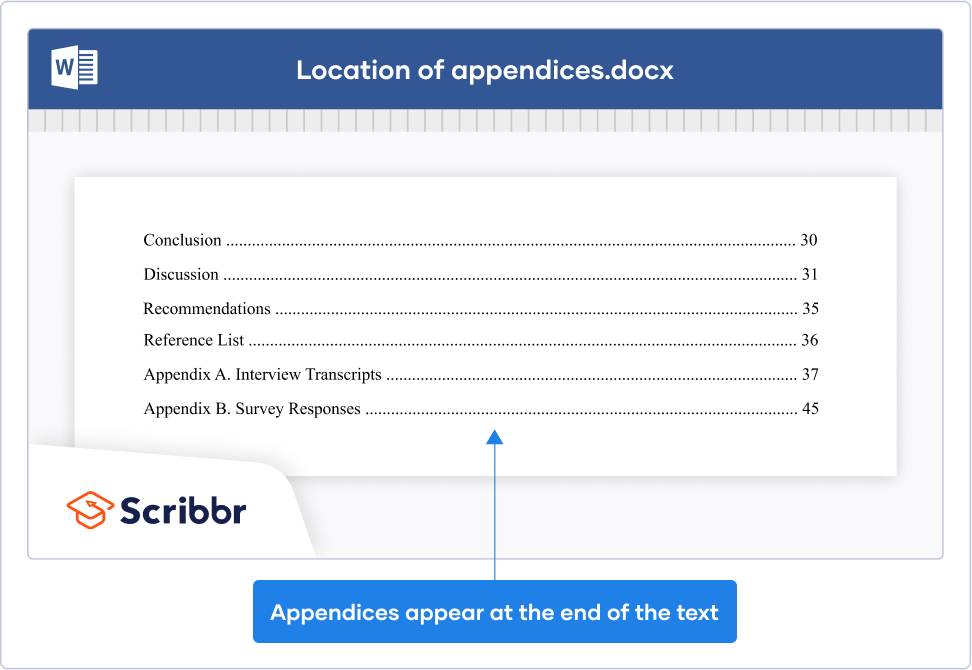

In an APA Style paper, appendices are placed at the very end, after the reference list .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Do i need an appendix, appendix format example, organizing and labeling your appendices, frequently asked questions.

You don’t always need to include any appendices. An appendix should present information that supplements the reader’s understanding of your research but is not essential to the argument of your paper . Essential information is included in the main text.

For example, you might include some of the following in an appendix:

- Full transcripts of interviews you conducted (which you can quote from in the main text)

- Documents used in your research, such as questionnaires , instructions, tests, or scales

- Detailed statistical data (often presented in tables or figures )

- Detailed descriptions of equipment used

You should refer to each appendix at least once in the main text. If you don’t refer to any information from an appendix, it should not be included.

When you discuss information that can be found in an appendix, state this the first time you refer to it:

Note that, if you refer to the same interviews again, it’s not necessary to mention the appendix each time.

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

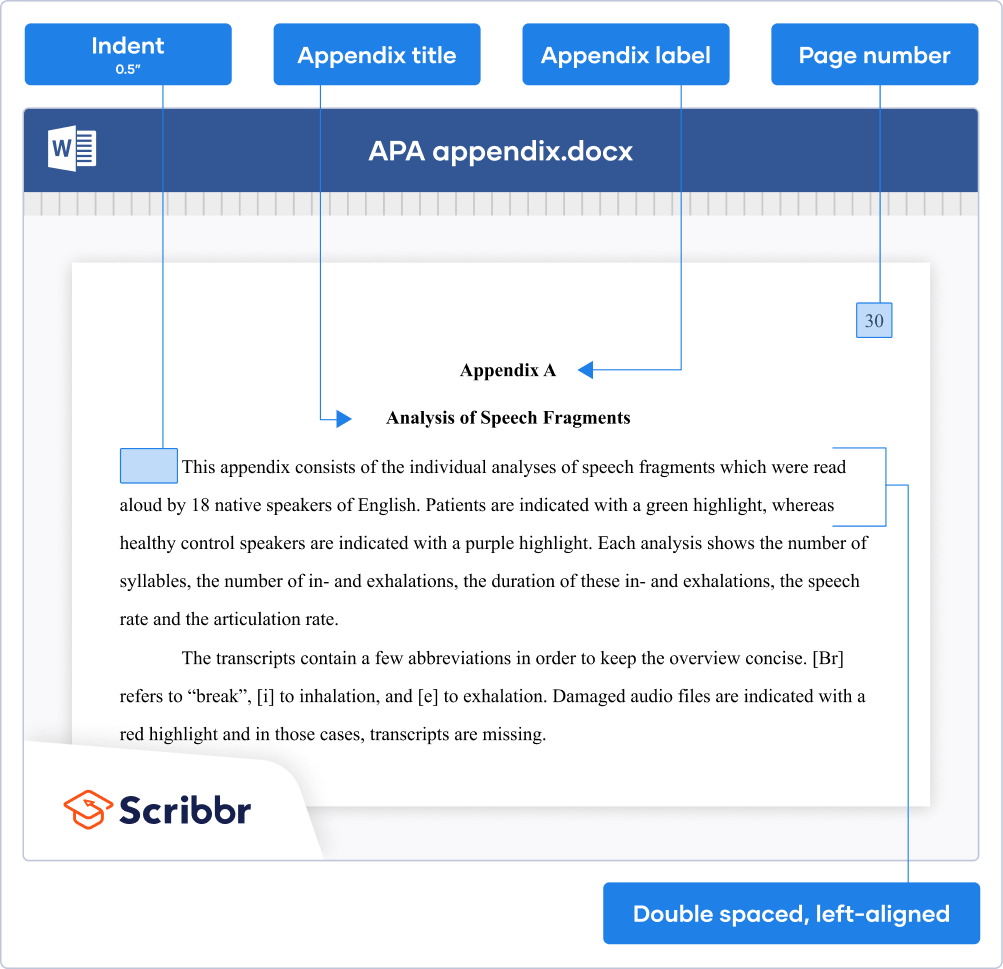

The appendix label appears at the top of the page, bold and centered. On the next line, include a descriptive title, also bold and centered.

The text is presented in general APA format : left-aligned, double-spaced, and with page numbers in the top right corner. Start a new page for each new appendix.

The example image below shows how to format an APA Style appendix.

If you include just one appendix, it is simply called “Appendix” and referred to as such in-text:

When more than one appendix is included, they are labeled “Appendix A,” “Appendix B,” and so on.

Present and label your appendices in the order they are referred to in the main text.

Labeling tables and figures in appendices

An appendix may include (or consist entirely of) tables and/or figures . Present these according to the same formatting rules as in the main text.

Tables and figures included in appendices are labeled differently, however. Use the appendix’s letter in addition to a number. Tables and figures are still numbered separately and according to the order they’re referred to in the appendix.

For example, in Appendix A, your tables are Table A1, Table A2, etc; your figures are Figure A1, Figure A2, etc.

The numbering restarts with each appendix: For example, the first table in Appendix B is Table B1; the first figure in Appendix C is Figure C1; and so on. If you only have one appendix, use A1, A2, etc.

If you want to refer specifically to a table or figure from an appendix in the main text, use the table or figure’s label (e.g. “see Table A3”).

If an appendix consists entirely of a single table or figure, simply use the appendix label to refer to the table or figure. For example, if Appendix C is just a table, refer to the table as “Appendix C,” and don’t add an additional label or title for the table itself.

An appendix contains information that supplements the reader’s understanding of your research but is not essential to it. For example:

- Interview transcripts

- Questionnaires

- Detailed descriptions of equipment

Something is only worth including as an appendix if you refer to information from it at some point in the text (e.g. quoting from an interview transcript). If you don’t, it should probably be removed.

Appendices in an APA Style paper appear right at the end, after the reference list and after your tables and figures if you’ve also included these at the end.

When you include more than one appendix in an APA Style paper , they should be labeled “Appendix A,” “Appendix B,” and so on.

When you only include a single appendix, it is simply called “Appendix” and referred to as such in the main text.

Yes, if relevant you can and should include APA in-text citations in your appendices . Use author-date citations as you do in the main text.

Any sources cited in your appendices should appear in your reference list . Do not create a separate reference list for your appendices.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2022, August 09). How to Create an APA Style Appendix | Format & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/apa-style/appendices/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, creating an apa style table of contents, how to format tables and figures in apa style, apa format for academic papers and essays, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Footnotes & Appendices

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

APA style offers writers footnotes and appendices as spaces where additional, relevant information might be shared within a document; this resource offers a quick overview of format and content concerns for these segments of a document. Should additional clarification be necessary, it is always recommended that writers reach out to the individual overseeing their work (i.e., instructor, editor, etc.). For your convenience, a student sample paper is included below; please note the document is filled with Lorem Ipsum placeholder text and references to footnotes and appendices are highighlighted. Additional marginal notes also further explain specific portions of the example.

Footnotes

Footnotes are supplementary details printed at the bottom of the page pertaining to a paper’s content or copyright information. This supporting text can be utilized in any type of APA paper to support the body paragraphs.

Content-Based Footnotes

Utilizing footnotes to provide supplementary detail can enrich the body text and reinforce the main argument of the paper. Footnotes may also direct readers to an alternate source for more detail on a topic. Though content footnotes can be useful in providing additional context, it is detrimental to include tangential or convoluted information. Footnotes should detail a focused subject; lengthier sections of text are better suited for the body paragraphs.

Acknowledging Copyright

When citing long quotations, images, tables, data, or commercially published questionnaires in-text, it is important to credit the copyright information in a footnote. Functioning much like an in-text citation, a footnote copyright attribution provides credit to the original source and must also be included in a reference list. A copyright citation is needed for both direct reprinting as well as adaptations of content, and these may require express permission from the copyright owner.

Formatting Footnotes

Each footnote and its corresponding in-text callout should be formatted in numerical order of appearance utilizing superscript. As demonstrated in the example below, the superscripted numerals should follow all punctuation with the exception of dashes and parentheses.

For example:

Footnote callouts should not be placed in headings and do not require a space between the callout and superscripted number. When reintroducing a footnote that has previously been called out, refrain from replicating the callout or footnote itself; rather, format such reference as “see Footnote 4”, for example. Footnotes should be placed at the bottom of the page on which the corresponding callout is referenced. Alternatively, a footnotes page could be created to follow the reference page. When formatting footnotes in the latter manner, center and bold the label “Footnotes” then record each footnote as a double-spaced and indented paragraph. Place the corresponding superscripted number in front of each footnote and separate the numeral from the following text with a single space.

Formatting Copyright Information

To provide credit for images, tables, or figures pulled from an outside source, include the accreditation statement at the end of the note for the visual. Copyright acknowledgements for long quotations or questionnaires should simply be placed in a footnote at the bottom of the page.

When formatting a copyright accreditation, utilize the following format:

- Establish if the content was reprinted or adapted by using language such as “from” for directly copied material or “adapted from” for material that has been modified

- Include the content’s title, author, year of publication, and source

- Cite the copyright holder and year of copyright or indicate that the source is public domain or licensed under Creative Commons

- If express permission was required to reprint the material, include a statement indicating that permission was acquired

Appendices

When introducing supplementary content that may not fit within the body of a paper, an appendix can be included to help readers better understand the material without distracting from the text itself. Primarily used to introduce research materials, specific details of a study, or participant demographics, appendices are generally concise and only incorporate relevant content. Much like with footnotes, appendices may require an acknowledgement of copyright and, if data is cited, an adherence to the privacy policies that protect participant identities.

Formatting Appendices

An appendix should be created on its own individual page labelled “Appendix” and followed by a title on the next line that describes the subject of the appendix. These headings should be centered and bolded at the top of the page and written in title case. If there are multiple appendices, each should be labelled with a capital letter and referenced in-text by its specific title (for example, “see Appendix B”). All appendices should follow references, footnotes, and any tables or figures included at the end of the document.

Text Appendices

Appendices should be formatted in traditional paragraph style and may incorporate text, figures, tables, equations, or footnotes. In an appendix, all figures, tables, and other visuals should be labelled with the letter of the corresponding appendix followed by a number indicating the order in which each appears. For example, a table labelled “Table B1” would be the first table in Appendix B. If there is only one appendix in the document, the visuals should still be labelled with the letter A and a number to differentiate them from those contained in the paper itself (for example, “Figure A3” is the third figure in the singular appendix, which is not labelled with a letter in the heading).

Table or Figure Appendices

When an appendix solely contains a table or figure, the title of the figure or table should be substituted with the title of the appendix. For example, if Appendix B only includes a figure, the figure should be labelled “Appendix B” rather than “Figure B1”, as it would be named if there were multiple figures included.

If an appendix does not contain text but includes numerous figures or table, the appendix should be formatted like a text appendix. The appendix would receive a name and label, and each figure or table would be given a corresponding letter and number. For example, if Appendix C contains two tables and one figure, these visuals would be labelled “Table C1”, “Table C2”, and “Figure C1” respectively.

Sample Paper

Media File: APA 7 - Student Sample Paper (Footnotes & Appendices)

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

An appendix contains supplementary material that is not an essential part of the text itself but which may be helpful in providing a more comprehensive understanding of the research problem or it is information that is too cumbersome to be included in the body of the paper. A separate appendix should be used for each distinct topic or set of data and always have a title descriptive of its contents.

Tables, Appendices, Footnotes and Endnotes. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

Importance of...

Appendices are always supplementary to the research paper. As such, your study must be able to stand alone without the appendices, and the paper must contain all information including tables, diagrams, and results necessary to understand the research problem. The key point to remember when including an appendix or appendices is that the information is non-essential; if it were removed, the reader would still be able to comprehend the significance, validity , and implications of your research.

It is appropriate to include appendices for the following reasons:

- Including this material in the body of the paper that would render it poorly structured or interrupt the narrative flow;

- Information is too lengthy and detailed to be easily summarized in the body of the paper;

- Inclusion of helpful, supporting, or useful material would otherwise distract the reader from the main content of the paper;

- Provides relevant information or data that is more easily understood or analyzed in a self-contained section of the paper;

- Can be used when there are constraints placed on the length of your paper; and,

- Provides a place to further demonstrate your understanding of the research problem by giving additional details about a new or innovative method, technical details, or design protocols.

Appendices. Academic Skills Office, University of New England; Chapter 12, "Use of Appendices." In Guide to Effective Grant Writing: How to Write a Successful NIH Grant . Otto O. Yang. (New York: Kluwer Academic, 2005), pp. 55-57; Tables, Appendices, Footnotes and Endnotes. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Points to Consider

When considering whether to include content in an appendix, keep in mind the following:

- It is usually good practice to include your raw data in an appendix, laying it out in a clear format so the reader can re-check your results. Another option if you have a large amount of raw data is to consider placing it online [e.g., on a Google drive] and note that this is the appendix to your research paper.

- Any tables and figures included in the appendix should be numbered as a separate sequence from the main paper . Remember that appendices contain non-essential information that, if removed, would not diminish a reader's ability to understand the research problem being investigated. This is why non-textual elements should not carry over the sequential numbering of non-textual elements in the body of your paper.

- If you have more than three appendices, consider listing them on a separate page in the table of contents . This will help the reader know what information is included in the appendices. Note that some works list appendices in the table of contents before the first chapter while other styles list the appendices after the conclusion but before your references. Consult with your professor to confirm if there is a preferred approach.

- The appendix can be a good place to put maps, photographs, diagrams, and other images , if you feel that it will help the reader to understand the content of your paper, while keeping in mind the study should be understood without them.

- An appendix should be streamlined and not loaded with a lot information . If you have a very long and complex appendix, it is a good idea to break it down into separate appendices, allowing the reader to find relevant information quickly as the information is covered in the body of the paper.

II. Content

Never include an appendix that isn’t referred to in the text . All appendices should be summarized in your paper where it is relevant to the content. Appendices should also be arranged sequentially by the order they were first referenced in the text [i.e., Appendix 1 should not refer to text on page eight of your paper and Appendix 2 relate to text on page six].

There are very few rules regarding what type of material can be included in an appendix, but here are some common examples:

- Correspondence -- if your research included collaborations with others or outreach to others, then correspondence in the form of letters, memorandums, or copies of emails from those you interacted with could be included.

- Interview Transcripts -- in qualitative research, interviewing respondents is often used to gather information. The full transcript from an interview is important so the reader can read the entire dialog between researcher and respondent. The interview protocol [list of questions] should also be included.

- Non-textual elements -- as noted above, if there are a lot of non-textual items, such as, figures, tables, maps, charts, photographs, drawings, or graphs, think about highlighting examples in the text of the paper but include the remainder in an appendix.

- Questionnaires or surveys -- this is a common form of data gathering. Always include the survey instrument or questionnaires in an appendix so the reader understands not only the questions asked but the sequence in which they were asked. Include all variations of the instruments as well if different items were sent to different groups [e.g., those given to teachers and those given to administrators] .

- Raw statistical data – this can include any numerical data that is too lengthy to include in charts or tables in its entirety within the text. This is important because the entire source of data should be included even if you are referring to only certain parts of a chart or table in the text of your paper.

- Research instruments -- if you used a camera, or a recorder, or some other device to gather information and it is important for the reader to understand how, when, and/or where that device was used.

- Sample calculations – this can include quantitative research formulas or detailed descriptions of how calculations were used to determine relationships and significance.

NOTE: Appendices should not be a dumping ground for information. Do not include vague or irrelevant information in an appendix; this additional information will not help the reader’s overall understanding and interpretation of your research and may only distract the reader from understanding the significance of your overall study.

ANOTHER NOTE : Appendices are intended to provide supplementary information that you have gathered or created; it is not intended to replicate or provide a copy of the work of others. For example, if you need to contrast the techniques of analysis used by other authors with your own method of analysis, summarize that information, and cite to the original work. In this case, a citation to the original work is sufficient enough to lead the reader to where you got the information. You do not need to provide a copy of this in an appendix.

III. Format

Here are some general guideline on how to format appendices . If needed, consult the writing style guide [e.g., APA, MLS, Chicago] your professor wants you to use for more detail:

- Appendices may precede or follow your list of references.

- Each appendix begins on a new page.

- The order they are presented is dictated by the order they are mentioned in the text of your research paper.

- The heading should be "Appendix," followed by a letter or number [e.g., "Appendix A" or "Appendix 1"], centered and written in bold type.

- If there is a table of contents, the appendices must be listed.

- The page number(s) of the appendix/appendices will continue on with the numbering from the last page of the text.

Appendices. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Appendices. Academic Skills Office, University of New England; Appendices. Writing Center, Walden University; Chapter 12, "Use of Appendices." In Guide to Effective Grant Writing: How to Write a Successful NIH Grant . Otto O. Yang. (New York: Kluwer Academic, 2005), pp. 55-57 ; Tables, Appendices, Footnotes and Endnotes. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Lunsford, Andrea A. and Robert Connors. The St. Martin's Handbook . New York: St. Martin's Press, 1989; What To Know About The Purpose And Format Of A Research Paper Appendix. LoyolaCollegeCulion.com.

Writing Tip

Consider Putting Your Appendices Online

Appendices are useful because they provide the reader with information that supports your study without breaking up the narrative or distracting from the main purpose of your paper. If you have a lot of raw data or information that is difficult to present in textual form, consider uploading it to an online site. This prevents your paper from having a large and unwieldy set of appendices and it supports a growing movement within academe to make data more freely available for re-analysis. If you do create an online portal to your data, note it prominently in your paper with the correct URL and access procedures if it is a secured site.

Piwowar, Heather A., Roger S. Day, and Douglas B. Fridsma. “Sharing Detailed Research Data Is Associated with Increased Citation Rate.” PloS ONE (March 21, 2007); Wicherts, Jelte M., Marjan Bakker, and Dylan Molenaar. “Willingness to Share Research Data Is Related to the Strength of the Evidence and the Quality of Reporting of Statistical Results.” PLoS ONE (November 2, 2011).

- << Previous: 9. The Conclusion

- Next: 10. Proofreading Your Paper >>

- Last Updated: Apr 1, 2024 9:56 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

APA 7th edition - Paper Format: Appendices

- Introduction

- Mechanics of Style

- Overall Paper

- Sample Papers

- Reference List

- Tables and Figures

- APA Citations This link opens in a new window

- Additional Resources

- Writing Skills This link opens in a new window

How to Format An Appendix - Tutorial

- APA Appendices - JIBC Tip Sheet All you need to know about appendices in APA Style.

Information in this section is as outlined in the APA Publication Manual (2020), sections 2.14, 2.17, 2.24, and 7.6.

Appendices are used to include information that supplement the paper’s content but are considered distracting or inappropriate for the overall topic. It is recommended to only include an appendix if it helps the reader comprehend the study or theoretical argument being made. It is best if the material included is brief and easily presented. The material can be text, tables, figures, or a combination of these three.

Placement :

Appendices should be placed on a separate page at the end of your paper after the references, footnotes, tables, and figure. The label and title should be centre aligned. The contents of the appendix and the note should be left-aligned.

- If you are choosing to include tables and figures in your appendix, then you can list each one on a separate page or you may include multiple tables/figures in one appendix, if there is no text and each table and/or figure has its own clear number and title within the appendix.

- Tables and figures in an appendix receive a number preceded by the letter of the appendix in which it appears, e.g. Table A1 is the first table in Appendix A or of a sole appendix that is not labeled with a letter.

The follow elements are required for appendices in APA Style:

Appendix Labels:

Each appendix that you place in your paper is labelled “Appendix.” If a paper has more than one appendix, then label each with a capital letter in the order the appendices are referred to in your paper (“Appendix A” is referred to first, “Appendix B” is referred to second, etc).

- The label of the appendix should be in bold font, centre-aligned, follow Title Casing, and is located at the top of the page.

- If your appendix only contains one table or figure (and no text), then the appendix label takes the place of the table/figure number, e.g. the table may be referred to as “Appendix B” rather than “Table B1.”

Appendix Titles:

Each appendix should have a title, that describes its contents. Titles should be brief, clear, and explanatory.

- The title of the appendix should be in bold font, centre-aligned, follow Title Casing, and is one double-spaced line down from the appendix label.

- If your appendix only contains one table or figure (and no text), then the appendix title takes the place of the table/figure title.

Appendix Contents:

- Left aligned and indented; written the same as paragraphs within the body of the paper

- Double-spaced and with the same font as the rest of the paper

- If the appendix contains a table and/or figure, then the table/figure number must contain a letter to correlate the table and/or figure to the appendix and not the body of the paper, e.g. “Table A1” rather than “Table 1” to clarify that the table appears in the appendix and not in the body of the paper.

- All tables and figures in an appendix must be mentioned in the appendix and numbered in order of mention.

- All tables and figures must be aligned to the left margin, (not center aligned), and positioned after a paragraph break, preferably the paragraph in which they are referred to, with a double-spaced blank line between the table and the text.

- Each table and figure should include a note afterwards to further explain the supplement or clarify information in the table or figure to your paper/appendix and can be general, specific, and probability. See “Table Notes” in the section “Table and Figures” above for more details.

Referring to Appendices in the Text:

In your paper, refer to every appendix that you have inserted. Do not include an appendix in your work that you do not clearly explain in relation to the ideas in your paper.

- In general, only refer to the appendix by the label (“Appendix” or “Appendix A” etc.) and not the appendix title.

Reprinting or Adapting:

If you did not create the content in the appendix yourself, for instance if you found a figure on the internet, you must include a copyright attribution in a note below the figure.

- A copyright attribution is used instead of an in-text citation.

- Each work should also be listed in the reference list.

Please see pages 390-391 in the Manual for example copyright attributions.

- << Previous: Tables and Figures

- Next: Workshops >>

- Last Updated: Feb 7, 2024 1:05 PM

- URL: https://libguides.jibc.ca/apa/formatyourpaper

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Appendices – Writing Guide, Types and Examples

Appendices – Writing Guide, Types and Examples

Table of Contents

Definition:

Appendices refer to supplementary materials or documents that are attached to the end of a Book, Report , Research Paper , Thesis or other written work. These materials can include charts, graphs, tables, images, or other data that support the main content of the work.

Types of Appendices

Types of appendices that can be used depending on the content and purpose of the document. These types of Appendices are as follows:

Statistical Appendices

Statistical appendices are used to present raw data or statistical analysis that is relevant to the main text but would be too bulky to include in the main body of the document. These appendices may include tables, graphs, charts, or other types of visual aids that help to illustrate the data.

Technical Appendices

Technical appendices are used to provide detailed technical information that is relevant to the main text but would be too complex or lengthy to include in the main body of the document. These appendices may include equations, formulas, diagrams, or other technical details that are important for understanding the subject matter.

Bibliographical Appendices

Bibliographical appendices are used to provide additional references or sources that are relevant to the main text but were not cited in the main body of the document. These appendices may include lists of books, articles, or other resources that the author consulted in the course of their research.

Historical Appendices

Historical appendices are used to provide background information or historical context that is relevant to the main text but would be too lengthy or distracting to include in the main body of the document. These appendices may include timelines, maps, biographical sketches, or other historical details that help to contextualize the subject matter.

Supplemental Appendices

Supplemental appendices are used to provide additional material that is relevant to the main text but does not fit into any of the other categories. These appendices may include interviews, surveys, case studies, or other types of supplemental material that help to further illustrate the subject matter.

Applications of Appendices

Some applications of appendices are:

- Providing detailed data and statistics: Appendices are often used to include detailed data and statistics that support the findings presented in the main body of the document. For example, in a research paper, an appendix might include raw data tables or graphs that were used to support the study’s conclusions.

- Including technical details: Appendices can be used to include technical details that may be of interest to a specialized audience. For example, in a technical report, an appendix might include detailed calculations or equations that were used to develop the report’s recommendations.

- Presenting supplementary information: Appendices can be used to present supplementary information that is related to the main content but doesn’t fit well within the main body of the document. For example, in a business proposal, an appendix might include a list of references or a glossary of terms.

- Providing supporting documentation: Appendices can be used to provide supporting documentation that is required by the document’s audience. For example, in a legal document, an appendix might include copies of contracts or agreements that were referenced in the main body of the document.

- Including multimedia materials : Appendices can be used to include multimedia materials that supplement the main content. For example, in a book, an appendix might include photographs, maps, or illustrations that help to clarify the text.

Importance of Appendices

Appendices are important components of research papers, reports, Thesis, and other academic papers. They are supplementary materials that provide additional information and data that support the main text. Here are some reasons why appendices are important:

- Additional Information : Appendices provide additional information that is too detailed or too lengthy to include in the main text. This information includes raw data, graphs, tables, and charts that support the research findings.

- Clarity and Conciseness : Appendices help to maintain the clarity and conciseness of the main text. By placing detailed information and data in appendices, writers can avoid cluttering the main text with lengthy descriptions and technical details.

- Transparency : Appendices increase the transparency of research by providing readers with access to the data and information used in the research process. This transparency increases the credibility of the research and allows readers to verify the findings.

- Accessibility : Appendices make it easier for readers to access the data and information that supports the research. This is particularly important in cases where readers want to replicate the research or use the data for their own research.

- Compliance : Appendices can be used to comply with specific requirements of the research project or institution. For example, some institutions may require researchers to include certain types of data or information in the appendices.

Appendices Structure

Here is an outline of a typical structure for an appendix:

I. Introduction

- A. Explanation of the purpose of the appendix

- B. Brief overview of the contents

II. Main Body

- A. Section headings or subheadings for different types of content

- B. Detailed descriptions, tables, charts, graphs, or images that support the main content

- C. Labels and captions for each item to help readers navigate and understand the content

III. Conclusion

- A. Summary of the key points covered in the appendix

- B. Suggestions for further reading or resources

IV. Appendices

- A. List of all the appendices included in the document

- B. Table of contents for the appendices

V. References

- A. List of all the sources cited in the appendix

- B. Proper citation format for each source

Example of Appendices

here’s an example of what appendices might look like for a survey:

Appendix A:

Survey Questionnaire

This section contains a copy of the survey questionnaire used for the study.

- What is your age?

- What is your gender?

- What is your highest level of education?

- How often do you use social media?

- Which social media platforms do you use most frequently?

- How much time do you typically spend on social media each day?

- Do you feel that social media has had a positive or negative impact on your life?

- Have you ever experienced cyberbullying or harassment on social media?

- Have you ever been influenced by social media to make a purchase or try a new product?

- In your opinion, what are the biggest advantages and disadvantages of social media?

Appendix B:

Participant Demographics

This section includes a table with demographic information about the survey participants, such as age, gender, and education level.

Age Gender Education Level

- 20 Female Bachelor’s Degree

- 32 Male Master’s Degree

- 45 Female High School Diploma

- 28 Non-binary Associate’s Degree

Appendix C:

Statistical Analysis

This section provides details about the statistical analysis performed on the survey data, including tables or graphs that illustrate the results of the analysis.

Table 1: Frequency of Social Media Platforms

Use Platform Frequency

- Facebook 35%

- Instagram 28%

- Twitter 15%

- Snapchat 12%

Figure 1: Impact of Social Media on Life Satisfaction

Appendix D:

Survey Results

This section presents the raw data collected from the survey, such as participant responses to each question.

Question 1: What is your age?

Question 2: What is your gender?

And so on for each question in the survey.

How to Write Appendices

Here are the steps to follow to write appendices:

- Determine what information to include: Before you start writing your appendices, decide what information you want to include. This may include tables, figures, graphs, charts, photographs, or other types of data that support the main content of your paper.

- Organize the material: Once you have decided what to include, organize the material in a logical manner that follows the sequence of the main content. Use clear headings and subheadings to make it easy for readers to navigate through the appendices.

- Label the appendices: Label each appendix with a capital letter (e.g., “Appendix A,” “Appendix B,” etc.) and provide a brief descriptive title that summarizes the content.

- F ormat the appendices: Follow the same formatting style as the rest of your paper or report. Use the same font, margins, and spacing to maintain consistency.

- Provide detailed explanations: Make sure to provide detailed explanations of any data, charts, graphs, or other information included in the appendices so that readers can understand the significance of the material.

- Cross-reference the appendices: In the main text, cross-reference the appendices where appropriate by referring to the appendix letter and title (e.g., “see Appendix A for more information”).

- Review and revise: Review and revise the appendices just as you would any other part of your paper or report to ensure that the information is accurate, clear, and relevant.

When to Write Appendices

Appendices are typically included in a document when additional information needs to be provided that is not essential to the main text, but still useful for readers who want to delve deeper into a topic. Here are some common situations where you might want to include appendices:

- Supporting data: If you have a lot of data that you want to include in your document, but it would make the main text too lengthy or confusing, you can include it in an appendix. This is especially useful for academic papers or reports.

- Additional examples: I f you want to include additional examples or case studies to support your argument or research, but they are not essential to the main text, you can include them in an appendix.

- Technical details: I f your document contains technical information that may be difficult for some readers to understand, you can include detailed explanations or diagrams in an appendix.

- Background information : If you want to provide background information on a topic that is not directly related to the main text, but may be helpful for readers, you can include it in an appendix.

Purpose of Appendices

The purposes of appendices include:

- Providing additional details: Appendices can be used to provide additional information that is too detailed or bulky to include in the main body of the document. For example, technical specifications, data tables, or lengthy survey results.

- Supporting evidence: Appendices can be used to provide supporting evidence for the arguments or claims made in the main body of the document. This can include supplementary graphs, charts, or other visual aids that help to clarify or support the text.

- Including legal documents: Appendices can be used to include legal documents that are referred to in the main body of the document, such as contracts, leases, or patent applications.

- Providing additional context: Appendices can be used to provide additional context or background information that is relevant to the main body of the document. For example, historical or cultural information, or a glossary of technical terms.

- Facilitating replication: In research papers, appendices are used to provide detailed information about the research methodology, raw data, or analysis procedures to facilitate replication of the study.

Advantages of Appendices

Some Advantages of Appendices are as follows:

- Saving Space: Including lengthy or detailed information in the main text of a document can make it appear cluttered and overwhelming. By placing this information in an appendix, it can be included without taking up valuable space in the main text.

- Convenience: Appendices can be used to provide supplementary information that is not essential to the main argument or discussion but may be of interest to some readers. By including this information in an appendix, readers can choose to read it or skip it, depending on their needs and interests.

- Organization: Appendices can be used to organize and present complex information in a clear and logical manner. This can make it easier for readers to understand and follow the main argument or discussion of the document.

- Compliance : In some cases, appendices may be required to comply with specific document formatting or regulatory requirements. For example, research papers may require appendices to provide detailed information on research methodology, data analysis, or technical procedures.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

- How To Write A Research Paper Appendix: A Step-by-Step Guide

Think of appendices like bonus levels on your favorite video game. They are not a major part of the game, but they boost your points and they make the game worthwhile.

Appendix are important facts, calculations, or data that don’t fit into the main body of your research paper. Having an appendix gives your research paper more details, making it easier for your readers to understand your main ideas.

Let’s dive into how to create an appendix and its best practices.

Understanding the Purpose of an Appendix

If you’re looking to add some extra depth to your research, appendices are a great way to do it. They allow you to include extremely useful information that doesn’t fit neatly into the main body of your research paper, such as huge raw data, multiple charts, or very long explanations.

Think of your appendix as a treasure chest with different compartments. You can include different information including, extra data, surveys, graphs, or even detailed explanations of your methods. You can fit anything too big or detailed for the main paper in the appendix.

Planning Your Appendix

Before you dive into making your appendix, it’s a good idea to plan things out; think of it as drawing a map before going on an adventure.

You want your appendix to be organized and provide more context to your research. Not planning it will make the process time-consuming and make the appendix confusing to people reading your research paper.

How to Decide What to Include in Your Research Paper

You have to sort through the content that you will include in your appendix. Think of what your readers need to know to understand your key points. Anything that’s overly detailed, off-topic, or clutters up your paper is a good candidate for your appendix.

Tips for Organizing Your Appendix

Once you’ve figured out what to put in your appendix, it’s time to organize it. Your appendix is a place to add extra information, but it shouldn’t be cluttered or confusing to your readers. Instead, it should make your research paper easier to understand.

Use clear headings, labels, and even page numbers to help your readers find the information they need in the appendix. This way, it’s not a jumbled mess, but a well-organized part of your research paper

Formatting Guidelines

Yes, your appendix must be formatted. Most of the time, you’ll want to keep the font and margin sizes consistent with your main paper.

However, some universities and journals may have specific guidelines for appendix formatting. Verify if your institution has special guidelines, if they do, follow them, if they don’t use the same format as your main text.

Here’s a typical breakdown of how to format your appendix:

(1) Labeling and Titling

If you have different types of information in your appendix, use letters to label them, such as “Appendix A” and “Appendix B”. Then, give each appendix a title that explains the information inside it.

For example, if the first section of your appendix contains raw survey data, you could call it “Appendix A (Survey Data of People Living with Diabetes Under 18 in Texas)”. If the second section of your appendix contains charts, you could call it “Appendix B (The Effect of Sugar Tax in Curbing Diabetes in Children and Young Adults)”.

(2) Numbering Tables, Figures, and More

If you have tables, figures, or other things in your appendix, number them like a list. For example, “Table A1,” “Figure A1,” and more. This numbering helps your readers know what they’re looking at, sort of like chapters in a book.

Creating Tables and Figures

Using tables and figures helps you organize your data neatly in your appendix. Here’s a step-by-step guide to creating tables and figures in your appendix:

Choose the Right Format for Your Appendix Data

Before creating tables or figures, you need to pick the right format to display the information. Think about what makes your data most clear and understandable.

For example, a table is better for detailed numbers, while a graph is great for showing trends. The right format makes your information easy to grasp and makes your paper look organized.

How to Create Tables in Your Appendix

You can use a spreadsheet program (like Excel or Google Sheets) to create tables to arrange information neatly. Make sure to give your table a clear title so readers know what it’s about.

Here’s a step-by-step guide to creating tables with a spreadsheet program:

- Open Google Sheets/Excel : Access Google Sheets or Excel through the web or download the app

- Open a New Spreadsheet or Existing File : Create a new spreadsheet or open an existing one where you want to insert a table.

- Select Data : Click and drag to select the data you want to include in the table.

- Insert Table : Once your data is selected, go to the “Insert” menu, then select “Table.

- Create Table : A dialog box will appear, confirming the selected data range. Make sure the “Use the first row as headers” option is checked if your data has headers. Click “Insert .”

- Customize Your Table : After inserting the table, you can customize it by adjusting the style, format, and other table properties using the “Table” menu in Google Sheets or Excel.

You can use software like PowerPoint, Google Slides, or graphic design tools to create them. If you have a chart or graph, make sure it’s easy to understand and add a title or labels to explain it.

You can use the editing tools for images to change the size and other aspects of the image.

Stop Struggling with Research Proposals! Get Organized and Impress Reviewers with our Template

Including Raw Data

The major reasons for including raw data in your appendix are transparency and credibility. Raw data is like your research recipe; it shows exactly what you worked with to arrive at your conclusions.

Raw data also provides enough information to guide researchers in replicating your study or getting a deeper understanding of your research.

Formatting and Presenting Raw Data

Formatting your raw data makes it easy for anyone to understand. You can use tables, charts, or even lists to display your data. For example, if you did a survey, you could put the survey responses in a table with clear headings.

When presenting your raw data, clear organization is your best friend. Use headings, labels, and consistent formatting to help your readers find and understand the data. This keeps your appendix from becoming a confusing puzzle.

Citing Your Appendix

Referencing your appendix in the main text gives readers a full picture of your research while they’re reading- They don’t have to wait until the end to figure out important details of your research.

Unlike actual references and citations, citing your appendix is a very straightforward process. You can simply say, “See Appendix A for more details.”

In-Text Citations for Appendix Content

If you would like to cite information in your appendix, you usually mention the author, year, and what exactly you’re citing. This allows you to give credit to the original creator of the content, so your readers know where it came from.

For instance, if you included a chart from a book in your appendix, you’d say something like (Author, Year, p. X). Keep in mind that there are different citation styles (APA, MLA, Chicago, and others), so your appendix may look a little different.

Proofreading and Editing

Proofreading and editing your appendix is just as important as proofreading and editing the main body of your paper. A poorly written or formatted appendix can leave a negative impression on your reader and detract from the overall quality of your work.

Make sure that your appendix is consistent with the main text of your paper in terms of style and tone unless otherwise stated by your institution. Use the same font, font size, and line spacing in the appendix as you do in the main body of your paper.

Your appendix should also be free of errors in grammar, spelling, punctuation, and formatting.

Tips for Checking for Errors in Formatting, Labeling, and Content

Here are some tips for checking for errors in formatting, labeling, and content in your appendix:

- Formatting : Make sure that all of the elements in your appendix are formatted correctly, including tables, figures, and equations. Check the margins, line spacing, and font size to make sure that they are consistent with the rest of your paper.

- Labeling : All of the tables, figures, and equations in your appendix should be labeled clearly and consistently. Use a consistent numbering system and make sure that the labels match the references in the main body of your paper.

- Content : Proofread your appendix carefully to catch any errors in grammar, spelling, punctuation, and content. You can use grammar editing tools such as Grammarly to help you automatically detect errors in your context.

Appendix Checklist

Having an appendix checklist guarantees a well-organized appendix and helps you spot and correct any overlooked mistakes.

Here’s a checklist of key points to review before finalizing your appendix:

- Is all of the information in the appendix relevant and necessary?

- Is the appendix well-organized and easy to understand?

- Are all the tables, numbers, and equations clearly labeled?

- Is the appendix formatted correctly and consistently with the main body of the paper?

- Is the appendix free of errors in grammar, spelling, punctuation, and content?

Sample Appendix

We have discussed what you should include in your appendix and how to organize it. Let’s take a look at what a well-formatted appendix looks like:

Appendix A. (Raw Data of Class Scores)

The following table shows the raw data collected for the study.

How the Sample Appendix Adheres to Best Practices

- The appendix is labeled clearly and concisely as “Appendix A. (Raw Data of Class Score).”

- The appendix begins on a new page.

- The appendix is formatted consistently with the rest of the paper, using the same font, font size, and line spacing.

- The table in the appendix is labeled clearly and concisely as “Table A1.”

- The table is formatted correctly, with consistent column widths and alignment.

- The table includes all of the necessary information, including the participant number, age, gender, and score.

- The appendix is free of grammar, spelling, and punctuation errors.

Having an appendix easily makes your research paper impressive to reviewers, and increases your likelihood of achieving high grades or journal publication. It also makes it easier for other researchers to replicate your research, allowing you to make a significant contribution to your research field.

Ensure to use the best practices in this guide to create a well-structured and relevant appendix. Also, use the checklist provided in this article to help you carefully review your appendix before submitting it.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- appendix data

- business research

- Moradeke Owa

You may also like:

Projective Techniques In Surveys: Definition, Types & Pros & Cons

Introduction When you’re conducting a survey, you need to find out what people think about things. But how do you get an accurate and...

Desk Research: Definition, Types, Application, Pros & Cons

If you are looking for a way to conduct a research study while optimizing your resources, desk research is a great option. Desk research...

43 Market Research Terminologies You Need To Know

Introduction Market research is a process of gathering information to determine the needs, wants, or behaviors of consumers or...

Subgroup Analysis: What It Is + How to Conduct It

Introduction Clinical trials are an integral part of the drug development process. They aim to assess the safety and efficacy of a new...

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

Reference management. Clean and simple.

What is an appendix in a paper

What is an appendix?

What type of information includes an appendix, the format of an appendix, frequently asked questions about appendices in papers, related articles.

An appendix is a section of a paper that features supporting information not included in the main text.

The appendix of a paper consists of supporting information for the research that is not necessary to include in the text. This section provides further insight into the topic of research but happens to be too complex or too broad to add to the body of the paper. A paper can have more than one appendix, as it is recommended to divide them according to topic.

➡️ Read more about what is a research paper?

An appendix can take many types of forms. Here are some examples:

- Surveys. Since many researchers base their methodology on surveys, these are commonly found attached as appendices. Surveys must be included exactly as they were presented to the respondents, and exactly how they were answered so the reader can get a real picture of the findings.

- Interviews . Whether it’s a transcript or a recording, interviews are usually included as an appendix. The list of questions and the real answers must be presented for complete transparency.

- Correspondence . All types of communication with collaborators regarding the research should be included as an appendix. These can be emails, text messages, letters, transcripts of audio messages, etc.

- Research tools . Any instrument used to perform the research should be acknowledged in an appendix to give the reader insight into the process. For instance, audio recorders, cameras, special software, etc.

- Non-textual items . If the research includes too many graphs, tables, figures, illustrations, photos or charts, these should be added as an appendix.

- Statistical data . When raw data is too long, it should be attached to the research as an appendix. Even if only one part of the data was used, the complete data must be given.

➡️ Learn more about surveys, interviews, and other research methodologies .

The format of an appendix will vary based on the type of citation style you’re using, as well as the guidelines of the journal or class for which the paper is being written. Here are some general appendix formatting rules:

- Appendices should be divided by topic or by set of data.

- Appendices are included in the table of contents.

The most common heading for an appendix is Appendix A or 1, centered, in bold, followed by a title describing its content.

- An appendix should be located before or after the list of references.

- Each appendix should start on a new page.

- Each page includes a page number.

- Appendices follow a sequential order, meaning they appear in the order in which they are referred to throughout the paper.

An appendix is usually added before or after the list of references.

There is no specific space limit to an appendix, but make sure to consult the guidelines of the citation format you are using.

Yes, all appendices must be included in the table of contents.

Appendices feature different types of material, for instance interviews, research tools, surveys, raw statistical data, etc.

Use an Appendix or Annex in Your Research Paper?

'Appendix' and 'annex' are commonly confused in research papers. While the use of an appendix is more common, the annex can also be a valuable way of supplementing your research. The appendix and the annex add supporting/supplementary information. Both are posted online and can be referred to by researchers with a particular interest in your study. The differences between them are context and length.

Updated on July 26, 2022

The terms “appendix” and “annex” are commonly confused in research papers. While the use of an appendix is more common, the annex can also be a valuable way of supplementing your research.

Both the appendix and the annex add supporting/supplementary information (SI), like tables and graphs, datasets, or transcriptions. Both are posted online and can be referred to by researchers with a particular interest in your study (especially if they're open access).

The main differences between these two forms of data supplement are context and length. Appendixes are common and are part of the study; you likely used them in theses and dissertations. Annexes deal with much longer and more detailed sets of information, and they're additional to the study's content. Let's take a deeper look at the differences so you'll never them confused.

What is an appendix?

An appendix is, according to Merriem-Webster, “supplementary material usually attached at the end of a piece of writing.” The word comes from the Latin appendere, which means “cause to hang (from something).” It's included in the paper at the end, usually after the references or bibliography.

Appendixes/Appendices can be seen as materials that supplement rather than complement the research. Read only by those with a specific interest.

Basics of an appendix

The following are generally true of an appendix.

- Included at the end of the manuscript.

- Written by one more of the paper's researchers. Exceptions are items like letters granting ethical clearance for the research or details of the research tools used (see the example later).

- Ties into the research directly; gives greater detail than the main body of the manuscript.

- Not too long. Of course, that's subjective, but generally speaking, it's a page or two rather than dozens of pages, or more.

What to put in an appendix

Some examples of an appendix are:

- Figures and tables

- Photographs

- Raw data (tables, plots, images)

- Questionnaires and interview questions (especially in qualitative research)

- Ethics approvals such as from the IRB

- Correspondences, such as letters or emails

Most research published as a journal article, and particularly as a thesis, will contain appendices rather than annexes.

This paper (PDF link) includes an appendix that details the instruments used in the research. Each test was used in the study, and the author felt the details were important enough to detail in the appendix, too much information to be presented in the main paper.

This chemistry article also presents supplementary data in the appendix. As it's too lengthy to put in print, a downloadable Word file is available. However, it's only data rather than an article or other full and standalone materials, which is likely why it was made into an appendix rather than an annex.

What is an annex?

Merriam-Webster defines an annex as “an added stipulation or statement.” In the context of research, both academic and commercial, annexes are usually separate additions to the research output and are submitted as separate documents.

Annex comes from the French annexer, which means “to join or attach.” Simply put, an annex comes along with (joining or attached to) a research paper. An example might be a UN report relevant to a manuscript, and that will be added as a supporting document, backing up the research findings. Annexes are used for materials that complement the research.

Basics of an annex

- Attached to the research paper as a separate item.

- Often (but not always) produced by someone outside the research team. If, for example, one of the researchers produced a white paper for the government on the research domain and this might complement the research, this could be an annex.

- Can be many pages long.

- Supports or informs the research that has been done; complements it.

- Is not part of the research output presented in the manuscript's body text.

What to put in an annex

Some examples of an annex are...

- Documents mentioned in the manuscript or that may support the manuscript

- News articles

- Lab reports

- Interviews of people mentioned in the manuscript.

- Data from other studies

Almost always, annexes are added to papers that exceed normal journal article lengths. They're supporting materials to lengthy research output, like those often funded by corporate or government funding.

This World Health Organization guidance paper on HIV/AIDS is itself 21 pages long but comes with separate downloadable annexes. The paper details the findings stemming from the research and describes the processes for the trials. On page 5, the paper notes that the annexes are included to give greater details on the clinical trials mentioned in the paper. In this sense, the annexes are for readers who want greater detail.

The paper reviews the trials done in the annex, but because the trials were not part of the research and was done by others, it was added as an annex.

Should you use an appendix or an annex?

Short answer: you should probably use an appendix. That's because they're much more common. Appendices are placed at the end of a document, while annexes are, technically, separate from it. The former is part of the paper, but the latter is not.

Annexes are often long documents, running even to hundreds of pages. Most often, someone an annex's author is someone who's not part of the research team. Appendices, however, are often by a paper's author(s) and are usually not more than a few pages each (though, in the case of datasets, they technically can be quite long).

Annexes are used to verify the research and provide additional, relevant information. They are documents from credible and relevant sources. They offer further insight into the research topic.

Normally, you'll be using appendices, and that's often because of the journal's word count limits. It may be ideal to include tables or charts in-line in the article, but if there's no room, the appendix can provide extra space.

Handling data: A workflow for dealing with data in your SI

Submission and sharing of data are especially key steps in dealing with your SI in appendixes, annexes, and other formats. When you're submitting your article to a journal, there is a common workflow for this:

- Create additional supplementary files (usually as few as possible, a single file is ideal).

- Upload to the journal site or one of the many ‘approved' online data repositories.

- You'll be given a URL to link back to your data files.

- Add this link to the Acknowledgements section of your paper with some text such as “Additional files in support of this article can be found at https://...”

Some commonly used and ostensibly approved online data repositories:

- Harvard Dataverse

- Open Science Framework (OSF)

- Mendeley Data

But don't get carried away!

Supplementary information, including appendixes and annexes, can also be abused. Additional information may be so long/big/dense that it actually may not undergo full peer review even though the rest of the article does.

A study by Pop and Salzberg asserted that journals' word restrictions may cause authors to move key information outside the main manuscript body. In this way, it can avert proper peer review while also being less accessible to the reader. This hinders further investigation because readers have to wade through huge amounts of supplementary documents to find what they're after.

It also robs authors cited in the supplementary information of the recognition they would receive from citations in the body text.

Nature commendably lays out specifics for SI – check them here .

Final thoughts

If you're unsure of what needs to be in your supplementary information, or if you even need an appendix or annex, as well as the English quality and style, a scientific edit can be a big help. Explore AJE's extensive editing services here .

The AJE Team

See our "Privacy Policy"

- Discoveries

- Right Journal

- Journal Metrics

- Journal Fit

- Abbreviation

- In-Text Citations

- Bibliographies

- Writing an Article

- Peer Review Types

- Acknowledgements

- Withdrawing a Paper

- Form Letter

- ISO, ANSI, CFR

- Google Scholar

- Journal Manuscript Editing

- Research Manuscript Editing

Book Editing

- Manuscript Editing Services

Medical Editing

- Bioscience Editing

- Physical Science Editing

- PhD Thesis Editing Services

- PhD Editing

- Master’s Proofreading

- Bachelor’s Editing

- Dissertation Proofreading Services

- Best Dissertation Proofreaders

- Masters Dissertation Proofreading

- PhD Proofreaders

- Proofreading PhD Thesis Price

- Journal Article Editing

- Book Editing Service

- Editing and Proofreading Services

- Research Paper Editing

- Medical Manuscript Editing

- Academic Editing

- Social Sciences Editing

- Academic Proofreading

- PhD Theses Editing

- Dissertation Proofreading

- Proofreading Rates UK

- Medical Proofreading

- PhD Proofreading Services UK

- Academic Proofreading Services UK

Medical Editing Services

- Life Science Editing

- Biomedical Editing

- Environmental Science Editing

- Pharmaceutical Science Editing

- Economics Editing

- Psychology Editing

- Sociology Editing

- Archaeology Editing

- History Paper Editing

- Anthropology Editing

- Law Paper Editing

- Engineering Paper Editing

- Technical Paper Editing

- Philosophy Editing

- PhD Dissertation Proofreading

- Lektorat Englisch

- Akademisches Lektorat

- Lektorat Englisch Preise

- Wissenschaftliches Lektorat

- Lektorat Doktorarbeit

PhD Thesis Editing

- Thesis Proofreading Services

- PhD Thesis Proofreading

- Proofreading Thesis Cost

- Proofreading Thesis

- Thesis Editing Services

- Professional Thesis Editing

- Thesis Editing Cost

- Proofreading Dissertation

- Dissertation Proofreading Cost

- Dissertation Proofreader

- Correção de Artigos Científicos

- Correção de Trabalhos Academicos

- Serviços de Correção de Inglês

- Correção de Dissertação

- Correção de Textos Precos

- 定額 ネイティブチェック

- Copy Editing

- FREE Courses

- Revision en Ingles

- Revision de Textos en Ingles

- Revision de Tesis

- Revision Medica en Ingles

- Revision de Tesis Precio

- Revisão de Artigos Científicos

- Revisão de Trabalhos Academicos

- Serviços de Revisão de Inglês

- Revisão de Dissertação

- Revisão de Textos Precos

- Corrección de Textos en Ingles

- Corrección de Tesis

- Corrección de Tesis Precio

- Corrección Medica en Ingles

- Corrector ingles

Select Page

How To Use Appendices in Research Papers

Posted by Rene Tetzner | Apr 11, 2021 | Referencing & Bibliographies | 0 |

How To Use Appendices in Research Papers Scholarly books often make good use of appendices (also called appendixes or annexes) and although it is rarer for appendices to be included in academic and scientific articles, many journal guidelines allow them. An appendix can present subsidiary or supplementary material that is directly related to the main argument in a book or paper and therefore potentially helpful to the reader, but which might prove distracting or inappropriate or simply too space consuming were it included in the main text. Often such material is relegated to footnotes, but if this would result in a footnote (or footnotes) too long and complex to be effective on the page, moving that material to an appendix is a good solution. An appendix is also a good format for material that is mentioned or discussed in more than one place in a long document, for it allows the author to avoid repetition while rendering the necessary information readily available to readers. In all three cases, using an appendix to provide the supporting information will streamline your argument without sacrificing helpful material.

Appendices can contain a wide variety of material, such as texts, translations, chronologies, genealogies, examples of principles and procedures, descriptions of complex pieces of equipment, survey questionnaires, participant responses, detailed demographics for a population or sample, lists (particularly long ones), tables and figures, explanations or elaborations of certain aspects of a study and any other supplementary information relevant to a book or article. However, as the Chicago Manual of Style warns, an ‘appendix should not be a repository for odds and ends that the author could not work into the text’ (2003, p.27). Ideally, each appendix should have a specific theme, focus or function and gather together materials of a particular type or relating to a particular topic. If more than one theme or topic requires this sort of treatment, additional appendices should be preferred to subdividing a single long appendix, although appendices can certainly make use of internal headings and subheadings.

It is best if appendices can stand on their own, so all abbreviations, symbols and specialised or technical terminology should be briefly defined or explained in the appendix itself, enabling the reader to understand the material without recourse to definitions and explanations elsewhere in the document. All information in appendices that overlaps material in the main body of a book or paper should also correspond with that material precisely in both content and format. If only one appendix is used, it can simply be called ‘Appendix,’ but if more than one is included, all appendices should be clearly labelled in an order representative of the order in which they are first mentioned in the main text. Letters or numbers can be used (e.g., ‘Appendix A’ or ‘Appendix 1’), and topic-specific headings can be added as well (Appendix A: Questionnaire 3 in German and English), but each appendix should be clearly referred to by its label when it is discussed in the text. Following these simple procedures will enable your appendices to meet the needs of your readers effectively.

You might be interested in Services offered by Proof-Reading-Service.com

Journal editing.

Journal article editing services

PhD thesis editing services

Scientific Editing

Manuscript editing.

Manuscript editing services

Expert Editing

Expert editing for all papers

Research Editing

Research paper editing services

Professional book editing services

Related Posts

How To Cite ISO, ANSI, CFR & Other Industry Standards & Guidelines

September 12, 2021

How To Write an Annotated Bibliography

August 3, 2021

Abbreviating References to Specific Pages in Source Texts

August 1, 2021

How To Cite a Research Paper & Provide a Bibliographical Reference

July 29, 2021

Our Recent Posts

Our review ratings

- Examples of Research Paper Topics in Different Study Areas Score: 98%

- Dealing with Language Problems – Journal Editor’s Feedback Score: 95%

- Making Good Use of a Professional Proofreader Score: 92%

- How To Format Your Journal Paper Using Published Articles Score: 95%

- Journal Rejection as Inspiration for a New Perspective Score: 95%

Explore our Categories

- Abbreviation in Academic Writing (4)

- Career Advice for Academics (5)

- Dealing with Paper Rejection (11)

- Grammar in Academic Writing (5)

- Help with Peer Review (7)

- How To Get Published (146)

- Paper Writing Advice (17)

- Referencing & Bibliographies (16)

Organizing Academic Research Papers: Appendices

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Executive Summary

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tertiary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Annotated Bibliography

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- How to Manage Group Projects

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Essays

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Acknowledgements

An appendix contains supplementary material that is not an essential part of the text itself but which may be helpful in providing a more comprehensive understanding of the research problem and/or is information which is too cumbersome to be included in the body of the paper. A separate appendix should be used for each distinct topic or set of data and always have a title descriptive of its contents .

Importance of...

Your research paper must be complete without the appendices, and it must contain all information including tables, diagrams, and results necessary to address the research problem. The key point to remember when you are writing an appendix is that the information is non-essential; if it were removed, the paper would still be understandable.

It is appropriate to include appendices...

- When the incorporation of material in the body of the work would make it poorly structured or it would be too long and detailed and

- To ensure inclusion of helpful, supporting, or essential material that would otherwise clutter or break up the narrative flow of the paper, or it would be distracting to the reader.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Points to Consider

When considering whether to include content in an appendix, keep in mind the following points:

- It is usually good practice to include your raw data in an appendix, laying it out in a clear format so the reader can re-check your results. Another option if you have a large amount of raw data is to consider placing it online and note this as the appendix to your research paper.

- Any tables and figures included in the appendix should be numbered as a separate sequence from the main paper . Remember that appendices contain non-essential information that, if removed, would not diminish a reader's understanding of the overall research problem being investigated. This is why non-textual elements should not carry over the sequential numbering of elements in the paper.

- If you have more than three appendices, consider listing them on a separate page at the beginning of your paper . This will help the reader know before reading the paper what information is included in the appendices [always list the appendix or appendices in a table of contents].