British Council Creative Economy

New and changing dynamics, john newbigin, what is the creative economy.

How the term ‘creative industries’ began

The term ‘creative industries’ began to be used about twenty years ago to describe a range of activities, some of which are amongst the oldest in history and some of which only came into existence with the advent of digital technology. Many of these activities had strong cultural roots and the term ‘cultural industries’ was already in use to describe theatre, dance, music, film, the visual arts and the heritage sector, although this term was itself controversial as many artists felt it demeaning to think of what they did as being, in any way, an ‘industry’.

‘Industries’ or not, no one could argue with the fact that these activities – both the narrowly defined cultural industries and the much wider range of new creative industries – were of growing importance to the economy of many countries and gave employment to a large number of people. But no government had attempted to measure their overall economic contribution or think strategically about their importance except, perhaps, the US government which, for almost a hundred years, had protected and fostered its film industry, not just because of its value to the US economy but because it projected US culture and influence around the world. Although they did not constitute an easily identified industrial ‘sector’ in the way that aerospace, pharmaceuticals or automotive are seen as sectors, one thing all these activities had in common was that they depended on the creative talent of individuals and on the generation of intellectual property. In addition, to think of them as a ‘sector’, however arbitrary the definition, drew attention to the fact that they were part of or contributed to a wide range of industries and professions, from advertising to tourism, and there was evidence that the skills and work styles of the creative sector were beginning to impact on other areas of the economy, especially in the use of digital technologies.

The first attempt to measure the value of the creative industries

In 1997, a newly elected Labour government in the UK decided to attempt a definition and assess their direct impact on the British economy. Drawing on a study published in 1994 by the Australian government, Creative Nation , and on the advice of an invited group of leading creative entrepreneurs, the government’s new Department for Culture, Media and Sport published Creative Industries – Mapping Document 1998 that listed 13 areas of activity – advertising, architecture, the arts and antiques market, crafts, design, designer fashion, film, interactive leisure software, music, performing arts, publishing, software, television and radio – which had in common the fact that they “… have their origin in individual creativity, skill and talent and … have a potential for wealth creation through the generation of intellectual property”. The concept of intellectual property (in other words the value of an idea that can be protected by copyright, patents, trade marks or other legal and regulatory mechanisms to stop it being copied or turned to commercial advantage without the permission of the person whose idea it was) was seen as central to any understanding of creative industries – and continues to be so.

Critics argued that the study was creating false distinctions and that individual creativity and talent were at the heart of many other areas of activity, from bio-sciences to engineering. Of course, that is true but the study had deliberately chosen not to include the creative work of scientists and engineers that is built on systematic analysis and enquiry, and to focus instead on the more random drivers of creativity in the social and cultural spheres. Another criticism was that the study failed to acknowledge the difference between businesses that actually generated intellectual property value through the creative talent of individuals, and were typically small, under-capitalised SMEs or micros (‘small or medium enterprises’, meaning they had between 25 and 500 employees, or ‘micro-businesses’, meaning they had 10 or fewer employees), and businesses that benefitted from owning and exploiting that intellectual property that were typically large, heavily-capitalised transnational conglomerates, sometimes with very little evidence of ‘creativity’ in the way they operated. The two kinds of company could not be more different from each other and yet they were both being defined as part of the ‘creative industries’. Despite these and other criticisms the study attracted considerable interest, particularly when a follow-up analysis in 2001 revealed that this arbitrarily defined creative sector was generating jobs at twice the underlying rate of the UK economy as a whole.

How thinking about the creative industries has evolved

Twenty years later, the concept of the ‘creative industries’, and their importance, is recognised by almost every government in the world and is beginning to give way to a much more inclusive idea of a wider ‘creative economy’. Of course, the desire to define specific industries as ‘creative’ persists, and will no doubt continue to be so. In some countries the definitions revolve closely around the arts and culture. Other countries have broader definitions that include, for example, food and gastronomy on the basis that food and cuisine have both economic and cultural significance. Other countries have a definition that includes well-established business-to-business industries such as publishing, software, advertising and design; the 11th Five-Year Plan of the Peoples Republic had as one of its central themes the need to “move from made in China to designed in China” – a classic exposition of the understanding that generating intellectual property is more valuable in the 21st century economy than manufacturing products. Other countries, including the UK, have wrestled with the tricky question of where to locate policy development for ‘creativity’ within their government structures – is it economic policy, industrial policy, cultural policy, education policy, or all four?

The more policy analysts and statisticians around the world thought about how to assess the true impact of the creative industries the more it became apparent that much more fundamental rethinking was necessary. For a start, the fusion of the arts and creative industries with digital technology was spawning whole new industries and skills that were not captured by the internationally recognised templates for measuring economic activity , the so-called ‘SIC’ and ‘SOC’ codes (Standard Industrial Classifications and Standard Occupational Classifications). This had the perverse effect of making important new areas of skill and wealth generation effectively invisible to governments and made international comparisons almost impossible. There were other obvious anomalies – not every job in the creative industries was ‘creative’ and many jobs outside the scope of the creative industries, however one chose to define them, were clearly very creative. The UK organisation Nesta , and others, began to explore this area, coming to the conclusion that the number of creative jobs in ‘non-creative’ industries was probably greater than the number of creative jobs within the creative industries. How could one begin to measure their impact? Moreover, the massive impact of digital technology was transforming every industry, creative or not, while the internet was opening up an ever-changing variety of platforms for new creative expression which, in turn, was generating all kinds of new and very obviously creative businesses. For example, within a decade and a half of its birth the videogames industry had surpassed the hundred year old film industry in value. And if ‘design’ was to be included as a creative industry, which it obviously was, where did that leave process design which was a creative discipline but one whose impact was felt across every other area of economic activity from retail to transport planning and health?

The more policymakers thought about the creative industries the more it became apparent that it made no sense to focus on their economic value in isolation from their social and cultural value. A United Nations survey of the global creative economy, published in 2008, pointed out that far from being a particular phenomenon of advanced and post-industrial nations in Europe and North America, the rapid rate of growth of ‘creative and cultural industries’ was being felt in every continent, North and South. The report concluded “The interface between creativity, culture, economics and technology, as expressed in the ability to create and circulate intellectual capital, has the potential to generate income, jobs and exports while at the same time promoting social inclusion, cultural diversity and human development. This is what the emerging creative economy has begun to do.”

The creative economy has a cultural and social impact that is likely to grow

In a time of rapid globalisation, many countries recognise that the combination of culture and commerce that the creative industries represents is a powerful way of providing a distinctive image of a country or a city, helping it to stand out from its competitors. The value of widely recognised cultural ‘icons’, such as the Eiffel Tower in France, the Taj Mahal in India or the Sydney Opera House in Australia has given way to whole cultural districts that combine arts and commercial activity, from the Shoreditch district of London with its design studios, tech businesses, cafes and clubs to huge prestige projects such as the West Kowloon cultural district in Hong Kong or the cultural hub on Sadiyaat Island in Abu Dhabi that represent billions of dollars of investment.

Awareness of this broader significance was reflected in a UK government publication of 2009, Creative Britain , which argued that effective long-term policies for the creative industries depended on policy initiatives, many of them at city and regional level, that were social as much as economic and that included, for example, the need for radical changes in the way children’s education was being planned, if Britain’s economy was to achieve long-term success as a home of creativity and innovation.

By 2014 staff at Nesta felt the debate had moved on so significantly that a new definition was was called for; a simple definition of the ‘creative economy’, rather than ‘creative industries’, as “…those sectors which specialise in the use of creative talent for commercial purposes”. The same year, in an analysis of the UK’s cultural policy and practice, the writer Robert Hewsion observed in his book Cultural Capital – The Rise and Fall of Creative Britain, “It is the configuration of relationships that gives a system its essential characteristics. Thus, it is less helpful to define the creative economy by what it does, than try to understand how it is organised”.

This, in turn, opens up a whole new arena for discussion. It seems that these industries, especially the thousands of small and micro-businesses that are at the cutting edge of creativity, may not only be of growing economic significance but, in some sense, are a harbinger of a whole new economic order, providing a new paradigm for the way in which businesses are organised, education is understood and provided, value is measured, the working lives and career prospects of millions of people are likely to develop and how the cities they live in will be planned and built. In particular, the rapid growth of automation and the use of artificial intelligence and robotics, which heralds the so-called “Fourth Industrial Revolution”, is certain to have a major impact on employment globally. Researchers at Oxford University estimate that up to 47% of jobs in the US could be replaced by machines in the course of the next 20 years, while their figure for the UK is 35%. But a 2015 study by Nesta, ‘Creativity vs. Robots’ argued that the creative sector was to some extent immune to this threat, with 86% of ‘highly creative’ jobs in the US, and 87% in the UK, having no or low risk of being displaced by automation.

It is sometimes said that where oil was the primary fuel of the 20th century economy, creativity is the fuel of the 21st century. In the same way that energy policy and access to energy was a determinant of geopolitics throughout the 20th century, it may be that policies to promote and protect creativity will be the crucial determinants of success in the 21st. If that is true then we will have to rethink the way governments are organised, the way cities are planned, the way education is delivered, and the way citizens interact with their communities. So, thinking about what we mean by creativity and the creative economy could not be more important!

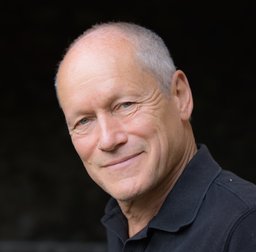

As Special Advisor to the Minister for Culture, Rt Hon Chris Smith MP, he was closely involved in developing the UK government’s first policies for the creative industries in the 1990s. He was Head of Corporate Relations for Channel 4 Television (2000-2005) and executive assistant to Lord Puttnam as the Chairman of the film company Enigma Productions Ltd (1992-97). As a policy advisor to the Leader of the Labour Party and Leader of the Opposition, Rt Hon Neil Kinnock, MP, (1986-92) he had responsibility for environmental and cultural issues, amongst others.

He is a member of the UK government’s Creative Industries Council; Chairman of the British Council’s Advisory Group for Arts and Creative Economy; member of the Advisory Board of the Institute for Creative and Cultural Entrepreneurship at Goldsmiths, University of London; and of the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s Knowledge Exchange Oversight Group. He is a member of the International Board of Advisors of Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology in Bangalore and an Honorary Professor at the University of Hong Kong.

He was a youth worker in East London for 6 years and writer-in-residence for Common Stock Theatre. He has also worked as a journalist and as an illustrator.

He was awarded an OBE for “services to creative industries and the arts” in the 2015 New Years Honours List.

www.creativeengland.co.uk

Related texts

Go on then … what are the creative industries?

Head of School of Creative Arts, James Cook University

Disclosure statement

Peter Murphy receives funding from the Australian Research Council for a project on creativity.

James Cook University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Creativity is the X factor of modern industry. When it slumps, our economy splutters.

Creativity is the source of the unprecedented wealth of the last two centuries. Yet we still understand very little about it.

Ideas create the industries and societies that generate the capital and income that lifts the world up. That is simple to say but difficult to achieve.

In the 1990s we began to talk about creative industries. We bundled fashion, design, advertising, architecture, publishing, software, movies, television and similar enterprises into their own sector. They became a lobby. In major economies, creative industries make up about 3%-5% of employment. As poorer economies develop, the size of their creative industries grows.

The term “creative industries sector”, though, is a bit of misnomer. For any industry can be creative. Conversely, fashion and design industries and their ilk often are lame. Little is creative or even interesting about today’s consumer computer companies.

In 2000, creative industries evangelists promised us a brilliant future. Some 30% of the population would belong to the creative class. The baton of creativity would pass from computing to bio-technology. Broadband networks would revolutionise business. Yet none of this happened.

Instead we ended up with prolonged global stagnation. We are in this pickle because we are less creative today than we were 50 years ago.

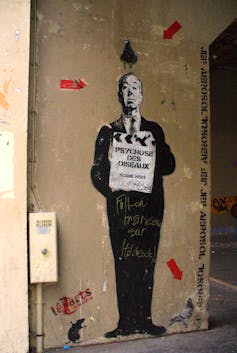

Any industry can be creative. Agriculture is just as important as media. Creativity should not be confused with glamour. Movies are glitzy but today they are also mostly banal. The days of Alfred Hitchcock and John Ford are long behind us.

The same is true of technology. If we compare the period 1930-1969 to 1970-2009, the per-capita number of significant Australian inventions declined.

More lobbies, more policies and more government money won’t fix this. Bio-medical research is a cautionary example. After 1970, research money in real terms exploded. Yet the number of new molecular entities approved for drug use in the United States in the 2000s was barely more than in the 1950s.

The arts are equally miserable. In the 1950s, discussion raged about the relative merits of figurative and abstract art. Tradition was pitched against modernity, ornament against smooth surfaces. Then along came arts council funding.

This was followed by obsequious hyper-ventilating discourses and finally the “neo” and “post” movements. The result was tedium. We can barely recollect the names of the practitioners of this anaemic era, let alone compare them with the monuments of Cubism, De Stijl or Abstract Expressionism.

In the past 40 years, the most interesting work in the arts has been in commercially-minded design and architecture. Works like Rem Koolhaas and OMA’s 2008 China Central Television (CCTV) Headquarters in Beijing are impressive. But these remain the exception.

This suggests that, for all our rhetoric, we still do not understand how creativity works. We try to institutionalise something that defies institutionalisation. There is no document-driven procedure for creativity. It is very hard to nail down. This is because what lies at its heart is very odd.

Creative people do what most people including most clever people do not do. They take what others normally think of as being unrelated and put them together. That is what it means to be creative. It is a very off-putting thought process, not unlike that of an acerbic comedian.

Someone at AT&T had the idea of putting together the concepts of (wired) telephony and (wireless) radio in 1917. Almost a century later we carry in our pockets the fruits of that original thought meld. Very few people think like that.

Creative societies allow those who do the freedom to muse and the room to convince others that their outlier idea will soon enter the mainstream and define the norm.

Creative people look at the exception and see it as the rule. They are not being difficult or outlandish. While often witty, they are not self-consciously wacky. They just see X as Y. That is their gift and their curse.

They see change as continuity not novelty. Creators are innate conservatives born with a wicked sense of irony.

Some societies and some eras go along with this. Some don’t. We pay lots of lip-service to the creative economy. But our time is not very creative. The arts and the sciences are dull. Technology and industry are not very innovative. No new industry sectors are emerging. This is a big problem.

The French economist Jean-Baptiste Say rightly observed in the early 19th century that in a modern dynamic economy supply creates demand. This means that without interesting and exciting products people save their money, and sluggish economies stagnate. That’s where we find ourselves in 2013.

Our larger problem is that we mistake glamour for creation. We think that working in the air-conditioned pastel offices of a designated creative industry makes us creative. It does not. We need to stop mistaking pretty labels for real entities.

We now have to go back to scratch. We need a hard re-think about what creativity is and how we encourage it. We need to de-regulate creativity and let it off the leash. Since the 1970s we have forged a society fixated on petty rules and stern processes. Universities are among the worst offenders.

The result is not creation but enervation. We call our research and development creative but mostly it is not. We are risk-averse and shy of discovery.

One of the few exceptions to this in the past 40 years was Silicon Valley in the 1970s, 1980s and early 1990s. It was truly free-wheeling. It was a place where a young man like Steve Jobs could combine his love of modernist aesthetics and electronic technologies. But that’s long gone.

Silicon Valley in its brief hey-day was philosophically libertarian. Today it is wearisomely left-liberal. Sanctimony has replaced discovery. Moralism has supplanted gusto. The fire of excitement has given way to the same ideology of correctness that haunts the universities today. Big ideas have been replaced by minute rules.

PayPal’s Peter Thiel is right when he observes that the technology and economics of our other key industries such as air travel and energy are stuck in the 1960s and 1970s . American critic and scholar Camille Paglia is right when she observes that, since the early 1970s, the arts have been a wasteland .

And I can’t see much monumental in the sciences since the structure of DNA was discovered in the 1950s. The incidence of classic science papers declines sharply after 1970.

We are not like Germany in the 1890s or California in the 1950s. One produced a stream of great philosophy and science; the other a stream of great technology. Until the tap was switched off – in one case by totalitarianism; in the other case by big government liberalism.

Little of our era will enter the history of ideas. Twittering on about creative industries makes no difference if our industries are not creative.

Our biggest problem today is that we lack ambition, energy and imagination. Our problem is us. Only we can fix that problem.

This is a foundation essay for The Conversation’s new Arts + Culture section. If you are an academic or researcher with relevant expertise and would like to respond to this article, please use our pitch facility .

- Foundation essays

- Creative industries

- Arts + Culture foundation essay

Biocloud Project Manager - Australian Biocommons

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Deputy Editor - Technology

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Communication and Culture

- Communication and Social Change

- Communication and Technology

- Communication Theory

- Critical/Cultural Studies

- Gender (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies)

- Health and Risk Communication

- Intergroup Communication

- International/Global Communication

- Interpersonal Communication

- Journalism Studies

- Language and Social Interaction

- Mass Communication

- Media and Communication Policy

- Organizational Communication

- Political Communication

- Rhetorical Theory

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Cultural and creative industries.

- Vicki Mayer Vicki Mayer Department of Communication, Tulane University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.552

- Published online: 26 September 2018

The critical study of cultural and creative industries involves the interrogation of the ways in which different social forces impact the production of culture, its forms, and its producers as inherently creative creatures. In historical terms, the notion of “the culture industry” may be traced to a series of postwar period theorists whose concerns reflected the industrialization of mass cultural forms and their attendant marketing across public and private spheres. For them, the key terms alienation and reification spoke to the negative impacts of an industrial cycle of production, distribution, and consumption, which controlled workers’ daily lives and distanced them from their own creative expressions. Fears of the culture industry drove a mass culture critique that led social scientists to address the structures of various media industries, the division of labor in the production of culture, and the hegemonic consent between government and culture industries in the military-industrial complex. The crisis of capitalism in the 1970s further directed critical scholars to theorize new dialectics of cultural production, its flexibilization via new communications technologies and transnational capital flows, as well as its capture via new property regimes. Reflecting government discourses for capital accumulation in a post-industrial economy, these theories have generally subsumed cultural industries into a creative economy composed of a variety of extra-industrial workers, consumers, and communicative agents. Although some social theorists have extended cultural industry critiques to the new conjuncture, more critical studies of creative industries focus on middle-range theories of power relations and contradictions within particular industrial sites and organizational settings. Work on immaterial labor, digital enclosures, and production cultures have developed the ways creative industries are both affective and effective structures for the temporal and spatial formation of individuals’ identities.

- consumption

- creative industries

- cultural industries

- intellectual property

- communication and critical studies

Communication studies always have taken an interest in the production of culture as both a universal human feature and a social formation. As a universal, each individual comes into being through the transformation of his or her environment, producing the self via the reproduction of language and symbolic goods. Whereas animals may also construct their environments in collective formations, it was famously Karl Marx who wrote, “what distinguishes the worst of architects from the best of bees is this, that the architect raises his structure in imagination before he erects it in reality” (Marx, 2007 /1967, p. 198). Marx rejected the dualism between the mind and the material, including the body that would be enrolled in labor. Under industrial capitalism, workers exchanged their own resources for wages. In return, those resources were marshaled in the production of goods that workers did not own, as property or as an extension of their imaginations.

The study of cultural and creative industries thus was founded in a concern with the ways historical social forces have impacted the production of culture, its forms, and its producers as inherently creative creatures. This has involved the study of particular industries and their organizational features, as well as overarching relationships between policies and markets in enabling the industrialization of culture and the constitution of labor. Even as the capitalization of culture has intensified and generated new questions around the industrialization of culture, communication scholars nevertheless share a concern about the ways work and the social are mutually constitutive.

The Culture Industry

The initial formulation of “the culture industry” points to the critical concerns among members of the Frankfurt School, in particular Theodore Adorno. A German émigré to the United States during the rise of the Third Reich, Adorno began writing about the culture industry as part of a longer collaboration with fellow émigré Max Horkheimer. Within the Dialectic of Enlightenment ( 1997 / 1944 ), the chapter “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception” outlines the basic concerns around the industrial production of culture.

Set during the rise of mass advertising and media industries, the culture industry encompasses the production, circulation, and consumption of cultural goods. Culture, in other words, could not be separated from the material processes that involve humans as both producers and consumers of its forms and contents. As producers, the culture industry employs workers who must rationalize their labor for the efficient assembly of mass media goods. Much like Henry Ford, whose production model for automobiles brought this product to the consuming masses, the management of the culture industry relied on the scientific control of human inputs in conjunction with new technologies that could better isolate work roles into discrete and measurable processes. The intensification of labor processes within the industrial model not only generates more capital for owners of the culture industry, but it has complementary impacts on the entire cycle of production and consumption. Workers expand the market for culture by creating more and cheaper goods that seem to address the personal needs of the workers and which they not only can afford, but also feel obliged to consume after the exhausting workday. The culture industry thus alienates workers from the holistic fruits of their own creative capacities, at the same time that it reifies the objects of their labor with the mystical ability to communicate personally with consumers. The class consciousness of workers according to their material realities is subsumed by their participation in the seemingly democratic marketplace of goods.

Adorno’s theory of the culture industry reflected critical scholars’ concerns over the rising and concentrated power of mass media industries throughout the mid- 20th century . In the United States, the vertical integration of film and broadcasting industries, along with the horizontal integration of national newspaper chains and newswire services, grew faster than other industries that faced either regulatory capture, such as telecommunications, or “trust-busting,” such as oil and railroads. The integration of domestic film studios with distributors and movie theaters, together with an international policy of technology capture, importation tariffs, and block booking, had ensured the rise of a cartel in global film production. Sociologists and economists working on the through the 1930s and 1940s showed that eight film studios, known as the “majors,” dominated global box offices (Wasko, 2015 ). Similarly, the concentration of commercial broadcast networks, first in radio and then in television, could be attributed both to the interconnectedness of equipment manufacturing, production, and distribution of contents and to the government’s protectionism of these networks’ airwave access over that of other public users. The news industry, in contrast, achieved economies of scale through an oligopoly of national chains served by a select group of international wire services.

Together these trends stoked fears of what C. W. Mills ( 1956 ) called a US “power elite” that could easily manipulate the public through economic, political, and military control. These manipulations could be evidenced through the direct complicity of the culture industry with national state policy objectives in World Wars I and II, the Cold War, and Vietnam. Meanwhile, the US political strategy for emerging from the Great Depression by stimulating consumer demand led to a flood of advertising and marketing designed to sell consumerism, first as an American value, and then as a Western democratic value in postwar and decolonizing societies. Whereas these state–market alliances consolidated the US power elite, they frequently challenged the producerist legal systems internationally, setting the stage for the later dismantling of public media systems and the establishment of consumerist legal systems under the geopolitical banner of the free flow of information and free trade.

Beyond propaganda, however, critical scholars in accordance with Adorno showed how the culture industry altered the relationship between cultural producers and their products. The first anthropological study of Hollywood was notable in concluding that Hollywood was a “dream factory,” not only in making ideology into entertainment, but also in making a compliant workforce that sacrificed creative individuality for corporate hierarchy (Powdermaker, 1950 ). For one, the agglomerated power of the culture industry was leverage against organized labor, which steadily declined in power over the course of the 20th century (Wasko, 2015 ). Time management and the rationalization of labor processes, or taylorization, allowed management in the culture industry to speed the production of goods and further detach workers from any ownership over the finished products (Braverman, 1998 ). This detachment, what the critical theorist Georg Lukács ( 1971 ) called “reification,” was codified in changing US legal definitions of property for cultural workers and their employers. By the mid- 20th century , case law had eroded employees’ rights to control their creative contributions to industrialized production processes. Legal contracts established the rights of corporations to own workers’ knowledge through the mechanisms of independent contracting, or work-for-hire (Fisk, 2010 ). Intellectual property law in the United States defended consumers’ rights to access a marketplace of goods over cultural producers’ rights of ownership in that marketplace, including copyrights, patents, and licenses.

These definitions of property extended to consumers as well when cultural industries, through research and measurement techniques, quantified and sold audiences as commodities to advertisers and sponsors. Through the ratings system, the “audience commodity” became the main profit driver for the US broadcasting industry, according to communications theorist and activist Dallas Smythe (Lent, 1994 ). Following the cycle of national production and consumption presumed in Adorno’s theory of the culture industry, cultural producers were then doubly reified as the tradable cogs in a factory-style production line and as the quantifiable audience on sale to advertisers.

The Turn to Cultural Industries

The critical agenda driving theories of the culture industry ran parallel to the growth of empirical research into the differences between various communication and media industries captured under this umbrella, as well as the differences between commercial and publicly managed frameworks for mass cultural production.

In the United States, Lewis Coser and Richard Peterson sought to develop a “production of culture perspective” in sociological and communication research into the plurality of cultural industries (Peterson & Anand, 2004 ). Influenced by both the administrative techniques and the functionalist sociology developed in the 1950s and 1960s by Paul Lazarsfeld and Robert K. Merton through the Columbia University Bureau of Applied Social Research, Peterson would build a research agenda with others primarily in organizational sociology, such as Paul DiMaggio, Wendy Griswold, and Diana Crane. Peterson theorized that different cultural industries, their structuring and internal organization in terms of workers’ roles and constraints, led to different outcomes in the types of mass culture produced. He thus broke with Adorno and others who claimed capitalism would have more generalizable impacts on cultural contents and their ideological orientations. In doing so, Peterson and his contemporaries developed what Merton ( 1968 ) called “middle-range” theories, which limited their critical scope to the functioning of particular cultural industries and the activities of their employees within legal and regulatory frameworks for the production of culture. To this day, much of the media industries scholarship in the United States invests in middle-range theory building (see Havens, Lotz, & Tinic, 2009 ).

The pluralization of cultural industries research also occurred in the United Kingdom, where public and private political frameworks for the production of mass culture clearly seemed to structure cultural contents in different ways. Beginning with the development of British cultural studies in Birmingham in the 1960s and extending across humanities and social science disciplines, cultural studies scholars argued for the equal stature of producers and consumers in the production of cultural meanings. Richard Johnson ( 1986 ) extended this insight to the study of cultural industries as organizations within a “circuit of culture,” through which cultural producers and consumers shared and altered the meanings of mass media goods and their contents. Unlike the production of culture perspective, which cited the primacy of cultural industries and their organization in producing culture, researchers using the circuit of culture, such as Stuart Hall and Martin Barker, tended to give cultural industries less primacy as the creators of semiotic meanings in cultural texts. This approach also extended Adorno’s cultural industry theory by considering the circulation of global cultural goods between different stages of production and consumption.

Using a combination of the production of culture and the circuit of culture approaches, the study of cultural industries as diverse institutions whose workers are shaped but not determined by social structures has been a dominant strand in communication and media studies globally. These studies are typically limited to the study of media industries as cultural industries and commercial culture, with less attention to either forms or organizations for community or alternative cultural production. 1 Studies in this lineage have addressed particular key roles in cultural industries, especially those with authority over content decisions, such as news editors as gatekeepers, television producers as creators, and a variety of other managerial professionals (Whitney & Ettema, 2003 ). These studies have followed the mantra that cultural industries afford their workers a degree of creativity within constraints, downplaying the forces of reification and exploitation that concerned critical communication scholars. At the same time, these studies have pointed to the variation between cultural industries that have emerged from different historical trajectories within dynamic regulatory and legal structures. New cultural industries invited comparative study of different kinds of cultural products and services. The advent of cable television and satellite pluralized the study of television industries, while the growth of mobile telephony and the Internet diffused the study of communication and cultural production across a variety of digital industries. Even cultural industries that scholars once considered in the singular became pluralized as they integrated more functions. Such was the case for the advertising agency, which came to encompass in-house marketing, branding, public relations, and sales industries.

Meanwhile, cultural industries themselves were restructuring. Starting in the late 1970s, the spread of computer networks and digital technologies allowed many cultural industries to become more mobile in locating different aspects of the production process across many different time zones and geographies. Sponsored by the globalization of financial capital and aided by the liberalization of communications networks, cultural industries that had been largely confined to national circuits of production, distribution, and consumption could now leverage various locations in decentralizing their operations. The national model for cultural production had reached an apex in terms of generating capital as oversaturated consumer markets could not offset noncompetitive sunk costs in labor or materials. Called a “spatio-temporal fix” (Harvey, 1982 ), national political economies looked for ways to allow capitalism to expand instantaneously and to accrue surplus profits transnationally.

Enabled by the new digital technologies themselves together with the policies, media and cultural industries merged outlets and platforms for the distribution of their products. New digital copyright laws offered cultural industries maximalist protections in developing new technologies that would safeguard intellectual properties from piracy, in the language of the industries, and sharing, in the language of consumers (Gillespie, 2007 ). Convergence had broad implications for industrial organizational cultures, which became more porous, allowing more participants into the production process, but also more ephemeral, as organizations started, ended, and recombined. Both copyright regimes and convergence spread globally, enforced first through mandated compliance with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund terms for aid and development, and then through international treaties aimed specifically at the liberalization of cultural trade and copyright protectionism. These changes impacted all industries, their workers, and their consumers based on their unique national histories. The critical communication tradition, which had grown out of the culture industry tradition in the United States and Europe, now expanded to chart the new geography of cultural industries and their complicities with liberalized cultural markets in France (Miege, 1987 ), eastern Europe (Garnham, 1993 ), Latin America (Bolano et al., 2000 ), and Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East (Mowlana, 1996 ).

In summary, the structures that had contained cultural industries within national boundaries were now pushing them centrifugally both in search of new markets and in creating market-driven efficiencies. Cultural industries moved into ever larger and more competitive markets, in which the consumer bases often became more highly specialized, forging niche audiences. Many cultural industries were motivated to seek new markets by concurrent reductions in public funding for culture, including the arts, public service broadcasting, and heritage production. These changes happened unevenly depending both on the industry and its governance within different countries. In many regions with public service broadcasting, such as Europe, Latin America, and Asia, the global spread of cable and satellite technologies accompanied the liberalization of those public markets. In the United States, the near-defunding of the National Endowment for the Arts in the 1990s pressured artists, performers, and other self-employed cultural workers to be more entrepreneurial and rent-seeking in their endeavors (Gibson, 2002 ). Highly commercialized cultural industries, such as film, also transformed. Hollywood production companies could shed the least profitable sectors of their production processes through outsourcing, independent freelance contracts, and location-based film shooting. The latter process has been referred to as “runaway production” because it has meant the dispersal of film labor and locations previously centralized in Southern California to places as far away as New Zealand, the Czech Republic, and Argentina (see Gasher & Elmer, 2005 ).

All of this occurred as social scientists were simultaneously defining more commercial industries as cultural and looking to more noncommercial cultural practices as contributors to urban regeneration. As Stuart Cunningham ( 2002 , p. 58) puts it in a retrospective of the time: “The former took industry in the direction of culture; the latter took culture in the direction of industry.”

Enter the Creative Industries

Many scholars use the modifiers cultural and creative interchangeably when referring to various industries for the production of culture, but to some scholars the distinction is crucial, marking a new orientation. Whereas cultural industries developed as a term in relation to power relations that governed the production and distribution of cultural goods and texts, the emergence of creative industries as a discourse developed within a power center. Creative industries dates to 1997 , when UK Prime Minister Tony Blair established a task force to quantify the economic value of cultural industry sectors to the overall economy. The initiative, which the traditional Left called a “tactical political maneuver” (O’Connor, 2012 , p. 390), itself fit into an overall policy strategy to seek out new centers for revenue generation in the postindustrial economy. The resulting 1998 document defined the creative industries as those whose “activities . . . have their origin in individual creativity, skill and talent and which have the potential for wealth and job creation through generation and exploitation of intellectual property” (DCMS, 2001 , p. 5). In other words, creative industries could be instrumental in staving off the slow declines in tax revenues, employment, and key industrial sectors, most notably manufacturing, while also promoting the creative capacities of their workers. Through the present century, policymakers in various countries sought to seek out their competitive advantages among creative industries in order to quantify and boost their overall impacts at both national and regional scales.

Following a nation-branding campaign in the 1990s called “Cool Britannia,” government agencies under a New Labour government in the United Kingdom increased public funding and started a National Lottery to seed and to incentivize creative industry clusters in 13 sectors. Those industries that the government formerly considered “cultural,” such as publishing and film, were combined with more traditional arts, crafts, and performance sectors as well as new all-digital industries, such as software and games. The government used new public management techniques to assess the value of culture based on consumption metrics and intellectual property receipts. The strategy was based on the economic principle that industries within any particular sector would benefit from the agglomeration and sharing of resources, particularly labor. In turn, the strategy put a premium on the employment of a young, college-educated workforce that could settle in close proximity to businesses offering increasingly shorter-term contracts. Creative industry policies thus touted “creativity” as a valuable job skill while fostering new models for flexible work conditions within and across firms in these geographically located clusters (Oakley, 2004 ). As flexibility inferred the power of employers to casualize workers at will, creative industry growth happened concurrently with the growth of a new social class of creative workers, also called the “precariat” (Standing, 2011 ) or the “cognitariat” (Miller & Ahluwalia, 2012 ).

In Australia, the political approaches to cultural and creative industries intersected directly with communication and media scholars, many of whom had taken an active role in influencing industries via cultural policymaking. Following a trajectory established in the late 1980s among cultural studies scholars, these scholars take up Tony Bennett’s ( 1999 ) adaptation of Michel Foucault’s theory of governmentality to defend a cultural studies that would actively work on policy and resist reducing culture to only its most profitable expression. Located in research institutes, especially the Centre for Creative Industries and Innovation at Queensland University of Technology (CCI), Terry Flew, John Hartley, and Stuart Cunningham, among others, urged researchers of media and popular culture to work within government institutions and their bureaucracies to have a greater impact on the making and circulation of culture and mass media. In more practical terms, these reformers hoped to spur more localized and authentic cultural productions in order to tip the balance both against the heavy importation of foreign-made cultural goods and the use of the country as a filming backlot for cultural representations set elsewhere. The ability of cultural policy enthusiasts to intervene in the stimulation of cultural industries was in part supported by a Labour Party government that allowed scholars to intervene in public broadcast regulation, the production of indigenous and minority programming, and the development of museum and heritage industries.

In contrast, communication and media scholars in the United States have given relatively little attention to the creative industries initiatives that have driven regional development strategies in each state. Informed by Richard Florida’s ( 2002 ) theory of the “creative class,” urban planners have attempted to replicate his high correlations between economic growth and population indices of creative professionals and urban bohemians. These plans have involved redirecting public monies towards public–private partnerships to attract and retain creative industries that can use incentives to leverage the best economic conditions for growth as measured by the numbers of start-ups, placemaking initiatives, and real estate values in “creative cities” (Markusen, 2014 ). Critics of these plans, including Florida himself, have shown that the “race to the bottom” for publicly seeding creative industries has come at the costs of increased social stratification, inner-city gentrification, and a more precarious workforce that lacks a safety net in social services (see Mayer, 2017 ).

Meanwhile, creative industry initiatives in India, China, and many East Asian countries focused on capturing segments of creative industries’ production chains that could synergize with those countries’ strengths in industrial manufacturing and services. Spurred by the liberalization of UK and US markets, and often in consultation with Australian and British universities, these countries pursued the development of creative industries associated with the “knowledge economy” and the concentration of computer literacy, such as animation, video games, and software design (O’Connor & Xin, 2006 ). In particular, Hong Kong, Singapore, Taipei, and Seoul were attracted to creative industry urban policies that fed official aspirations to become “world cities” (Kong et al., 2006 ). Launched often under the auspices of authoritarian or highly centralized forms of government, the policies have promoted the close intertwining of creative production with economic growth, while shedding Eurocentric notions of liberal personhood and autonomy associated with creativity in the original British articulation.

Across the globe, creative industries policies accompanied the international export and coproduction of various forms of national popular culture and their genres. Contrary to previous critiques of the one-way flow of cultural goods from the global North to the South and the global West to the East, export booms in Latin American music and film, Japanese anime and manga, Indian film and fashions, as well as a variety of Asian pop genres demonstrated the complex flows between geographies formerly considered central or peripheral. Three industrial trends have underwritten these booming export markets. First, the expansion of global media conglomerates diversified their products through a variety of localized subsidiaries. This happened particularly in audiovisual industries, such as television and film, which could be distributed through new cable systems and satellite technologies. For example, although News Corporation, an Australian-based company, purchased STAR TV as a satellite network for delivering foreign programming to Asia, the company restructured STAR into several localized companies, including STAR India, STAR China, and STAR Select for the Middle East. Each of these subsidiaries has become a media and entertainment producer for its specific region, leading a cultural marketization process that Daya Thussu ( 2005 ) named “Murdochization” after News Corporation’s media mogul. Second, many global media conglomerates operate in joint ventures which allow new independent companies to secure both financing and distribution outside of the “media capitals” where once-national goods were concentrated (Curtin, 2003 ). These agreements tended to promote the creation of cultural properties that could be deployed across a maximum number of goods that target the most lucrative consumer niches. Thus, international film, comics, video game, fashion, and merchandising industries gravitated towards animated Japanese properties that were “odorless,” or lacking a cultural specificity, which targeted global youth markets with disposable income (Iwabuchi, 2002 ). Finally, the clustering of creative industries in media capitals has led to diasporic and transnational export markets that did not necessarily depend on co-ventures. The expansion of Bollywood entertainment industries transcended film across a variety of South Asian diasporic media (Punathambekar, 2013 ). Similarly, Nollywood’s video film industries have expanded and circulated their products globally with little formal support from either transnational conglomerates or formal government structures (Miller, 2016 ).

In 2008 , the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) identified creative industries as “among the most dynamic sectors in world trade.” Arguing that “every society has its stock of intangible cultural capital articulated by people’s identity and values,” UNESCO defined creative industries in terms of any “knowledge-based activities that produce tangible goods or intangible intellectual or artistic services with creative content, economic value and market objectives” (UNCTAD, 2008 , p. 4). Directed at stimulating the assessment and development of creative economies in developing countries, the UNESCO report pointed to the impacts of creative industries in urban revitalization, in offering attractive jobs, and in promoting social inclusion in advanced societies. At the same time, the report eschewed a singular definition of creative industries, and instead compared different models of classification based on sectoral industries, core and peripheral industries, or types of intellectual properties. The UNESCO recommendations for developing countries included further market liberalization, the protection of domestic and international copyrights, and a strong emphasis on the relationship between creative industries and cultural tourism.

Critical Approaches to Creative Industries

Even as the positive predictions around the formation and expansion of creative industries have grown as part of policy agendas worldwide, communication scholars have questioned their optimism. As with the scope of creative industry policies, so too communication scholars have disagreed about which industries, workers, and economic sectors should be captured under this umbrella term. Critical approaches to creative industries, however, focused on key claims that its policy proponents have made about labor, property, consumption, and the environment.

Some of these critiques developed from the trajectories established by critics of the culture industry in the mid- 20th century . Extending a range of dependency scholars who attributed cultural imperialism to the growth of the culture industry in Latin America in particular, Toby Miller was prominent among a growing chorus of critical scholars who pointed to the unequal distribution of labor processes around the globe. Creative industries, Miller ( 2016 ) theorized as early as 1990 , depended on a New International Division of Cultural Labor (NICL) that doubly degraded the value of labor in advanced and developing countries. In the former countries, creative industry jobs formed a labor force of highly educated workers that would compete for increasingly casualized forms of cultural work. In the latter countries, creative industries relied on an underclass of unprotected laborers who could withstand poor wages and environmental conditions to manufacture the goods that carried the intellectual properties and brands developed by the former workers. Although the people in each labor force would experience their exploitation in different ways, the NICL explained how creative industries could exacerbate social inequalities in the face of eroded labor and environmental laws, the corporate capture of cultural properties, and the diversion of public goods into creative industry incentives.

Subsequent research into workers and working conditions in creative industries revealed both material and symbolic forms of discrimination in creative industries. Sociological researchers working in the United Kingdom and in the Netherlands have done the most extensive analysis of industry workforces, based on both demographics and career trajectories. These studies have shown that while some creative industries were more open to people with working-class backgrounds, for example video gaming, the best-paid jobs overall seemed to be dominated by white men from rather privileged backgrounds. These social inequalities not only reproduced economic disparities but also reinforced cultural power hierarchies in terms of distribution and consumption (Oakley & O’Brien, 2015 ). This social stratification in the labor market was exacerbated in the United Kingdom both by the defunding of public higher education in the arts and humanities, and by the rising importance of social networks and unpaid internships as prerequisites for attaining entry-level jobs. Ongoing scholarship by a number of feminist scholars, such as Roslyn Gill and Angela McRobbie, and critical race scholars, such as Arlene Dávila and Anamik Saha, have demonstrated that creative industry policies have entrenched historical discrimination trends based on gender, sex, and race.

At the same time, research showed that even those with the best jobs faced increasingly precarious conditions across creative industries. Described in positive terms as “boundaryless” or “portfolio” careers, creative industry workers increasingly experienced the anxiety of temp workers as public and private employers moved to contract-based labor forces. Workers across many creative industries operated as “multi-taskers” under time crunch pressures with new requisite forms of sociality, such as teamwork and continuous digital connectivity (Gregg, 2013 ). Associated with the rise of a feminized service labor sector that was paid to perform “emotion work,” in the words of Arlie Hochschild ( 1983 ), creative industry workers depended on social networks to maintain continuous employment while also engaging in a variety of self- and brand-promotional activities through social media. These researchers also drew on an Italian autonomist Marxist tradition that pointed to these instances of immaterial labor as evidence that society had become a “social factory” (Negri, 1983 ), in which there are no longer boundaries between public and private spheres or the use-value and exchange-value of one’s private emotions.

Building from the theory of the social factory, creative industries have also derived profits from what Tiziana Terranova ( 2004 ) identified as free labor. Terranova pointed to how new media uses commodified labor power when corporate owners collect and sell users’ private data. In a debate that has also encompassed Smythe’s conception of the audience commodity, digital labor scholars have theorized the ways that consumers act as producers, or prosumers, when they offer their private data through everyday Web navigation and Internet uses, which has also been called “playbour” in recent times to signify the merging of work and fun (Scholz, 2013 ). This debate has been intersected by feminist scholars of digital labor who have recalled other forms of unwaged work, such as domestic chores and childcare, in order to demonstrate the continuities between creative industries and traditional forms of control over the reproduction of capital within the family unit (Jarrett, 2015 ). Through all of these cross-disciplinary critiques applied to cultural work and creative industries, there have also been threads of optimism as autonomist, feminist, and digital labor scholars have identified new solidarities around work identities and new horizons for resistance to labor conditions.

Interestingly the increased critical attention to creative industry producers and consumers has come at a moment when the popularity of creative industry policies may be declining. Climate change science has put a negative spotlight on creative industries that either encourage unsustainable uses of raw materials or develop new technologies that are planned to be obsolete in order to increase future sales (Maxwell & Miller, 2012 ). Further, the social inequalities found within creative industry labor and consumer bases have been tied to the overall gentrification trends in the cities where they locate. For example, in large metropolises creative industry sectors have shared common interests with the profit motives of real estate and financial sectors, leading to a boom-and-bust cycle that has changed the face of neighborhoods from diverse enclaves to places of high-end “loft living” and leisure consumption (Zukin, 1989 ). Only time will tell if the aura that surrounds creative industries as a more privileged version of the ways all humans produce culture is ebbing, or perhaps simply flowing into another discourse about the relations between human creativity and the production of culture.

Discussion of the Literature

Much of the literature on cultural and creative industries fits into Graham Murdock’s ( 2003 ) taxonomy for research and theorizing, which includes work on:

Analyses of the ways shifts in the political economy impact industrial organizations and the ways culture is produced;

Mappings of the current state of a given industry with its connected sectors and processes;

Trade research into market strategies and trends among industries;

Qualitative investigations of professional or workers’ roles within comparative cultural industry sectors;

Longitudinal studies of the careers of individual cultural and creative workers; and

Ethnographies of the processes of creation, production, and distribution of a particular cultural good or product.

In addition to these topics, which tend to be empirically grounded in particular industries, communication and media scholars in the most recent period have pushed for new research that either hones or broadens the boundaries of cultural and creative industry research. David Hesmondhalgh and Anna Zoellner ( 2013 ), for example, advocate for a normative ethics of what is good work in advanced societies as a means of rescuing the specificity of creative work from other labor sectors. This trajectory further extends to the contemporary formation of creative worker communities (Mayer, Banks, & Caldwell, 2009 ), their moral economies for sharing resources (Banks, 2006 ), and their lay theories that guide work practices (Caldwell, 2008 ). While some of these researchers are embedded in the industries they study, others have made alliances with professional guilds, labor unions, and social movements based around class and work. The entanglements between researchers and their subjects have raised epistemological concerns about the unequal power relations between researchers and their subjects, which Laura Grindstaff ( 2002 ) described as “studying up” or “studying sideways” because of the relative lack of authority that those in the academy have relative to industry professionals. Some of this research is intended to be used for advocacy by improving cultural policy, standards, or work conditions within creative industries, or by supporting creative workers marginalized by those industries.

Conversely, other researchers since 2010 have pushed to deconstruct assumptions that have guided the cultural and creative industry scholarship. Rejecting limiting inquiries about cultural and creative industries as a reaffirmation of US hegemony around property ownership, Jack Qiu ( 2017 ) argues that research should expand to capture broader political economies upon which global cultural and creative industries depend. This expanded focus has opened the terrain of cultural and creative industry research to include the manufacturing and recycling of digital technologies in the Global South (Grossman, 2007 ), the infrastructures for energy, Internet, and broadband distribution (Parks & Starosielski, 2015 ), and the labors of nonwhite and Global South populations in the service of those industries (Nakamura, 2014 ; Shade & Porter, 2008 ). At the same time, theories of cultural and creative industries have involved re-evaluating the ontological biases in terms such as producer and professional (Mayer, 2011 ), as well as in legal definitions of piracy (Pang, 2012 ), formal versus informal media economies (Lobato & Thomas, 2015 ), and media infrastructures (Larkin, 2008 ). As the study of cultural and creative industries continues to incorporate a more transnational focus and broaden to capture more people within its circuits of production and exchange, the object of study more and more resembles its original Marxist imperative to examine the production of culture as both a universal human feature and a social formation.

Further Reading

- Banks, M. , Conor, B. , & Mayer, V. (Eds.). (2015). Production studies, the sequel! Cultural studies of global media industries . London, UK: Routledge.

- Bennett, T. (1998). Culture and policy: Acting on the social. International Journal of Cultural Policy , 4 , 271–289.

- Cantor, M. , & Zollars, C. (Eds.). (1993). Current research on occupations and professions: Vol. 8. Creators of culture . Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Caves, R. (2000). Creative industries: Contracts between art and commerce . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Christopherson, S. , & Clark, J. (2007). Remaking regional economies: Power, labor, and firm strategies in the knowledge economy . New York, NY: Routledge.

- Eikhof, D. , & Warhurst, C. (2013). The promised land? Why social inequalities are systemic in the creative industries. Employee Relations , 35 (5), 495–508.

- Flew, T. (2012). The creative industries: Culture and policy . London, UK: SAGE.

- Gill, R. , & Pratt, A. (2008). In the social factory? Immaterial labour, precariousness, and cultural work. Theory, Culture and Society , 25 , 1–30.

- Hartley, J. (Ed.). (2005). Creative industries . Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Hesmondhalgh, D. (2013). The cultural industries (3rd ed.). London, UK: SAGE.

- Hesmondhalgh, D. , & Saha, A. (2013). Race, ethnicity, and cultural production. Popular Communication , 11 (3), 179–195.

- Hewison, R. (2014). Cultural capital: The rise and fall of creative Britain . London, UK: Verso.

- Hirsch, P. (2000). Cultural industries revisited. Organization Science , 11 , 356–361.

- Hochschild, A. (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling . Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Miège, B. (1989). The capitalization of cultural production . New York, NY: International General.

- Miller, T. , & Yúdice, G. (Eds.). (2002). Cultural policy . London, UK: SAGE.

- Oakley, K. , & O’Connor, J. (2015). The Routledge companion to the cultural industries . New York, NY: Routledge.

- O’ Connor, J. (2010). The cultural and creative industries: A literature review (2nd ed.). Newcastle, UK: Creativity, Culture and Education.

- Power, D. , & Scott, A. J. (Eds.). (2004). Cultural industries and the production of culture . London, UK: Routledge.

- Pratt, A. C. (2008). Creative cities: The cultural industries and the creative class. Geografiska annaler: Series B, Human Geography , 90 (2), 107–117.

- Turow, J. (1992). Media systems in society: Understanding industries, strategies, and power . New York, NY: Longman.

- Banks, M. (2006). Moral economy and cultural work. Sociology , 40 (3), 455–472.

- Bennett, T. (1999). Putting policy into culture. In S. During (Ed.), The cultural studies reader (pp. 479–491). London, UK: Psychology Press.

- Bolaño, C. Mastrini, G. , & Albornoz, L. (2000). Globalización y monopolios en la comunicación en América Latina: hacia una economía política de la comunicación . Buenos Aires, Argentina: Biblos.

- Braverman, H. (1998). Labor and monopoly capital: The degradation of work in the twentieth century . New York: NYU Press. (Original work published 1974.)

- Caldwell, J. (2008). Production culture: Industrial reflexivity and critical practice in film and television . Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Cunningham, S. (2002). From cultural to creative industries: Theory, industry and policy implications. Media International Australia Incorporating Culture and Policy , 102 (1), 54–65.

- Curtin, M. (2003). Media capital: Towards a study of spatial flows. International Journal of Cultural Studies , 6 , 202–228.

- DCMS . (2001). Creative industries mapping document 2001 (2nd ed.). London, UK: Department of Culture, Media and Sport, p. 5.

- Fisk, C. L. (2010). Working knowledge: employee innovation and the rise of corporate intellectual property, 1800–1930 . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative class . New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Garnham, N. (1993). The mass media, cultural identity, and the public sphere in the modern world. Public Culture , 5 (2), 251–265.

- Gasher, M. , & Elmer, G. (2005). Contracting out Hollywood: Runaway productions and foreign location shooting . Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Gibson, L. (2002). Creative industries and cultural development: Still a Janus face? Media International Australia , 102 , 25–34.

- Gillespie, T. (2007). Wired shut: Copyright and the shape of digital culture . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Gregg, M. (2013). Work’s intimacy . London, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Grindstaff, L. (2002). The money shot: Trash, class, and the making of TV talk shows . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Grossman, E. (2007). High tech trash: digital devices, hidden toxics, and human health . Chicago, IL: Island Press.

- Harvey, D. (1982). The limits to capital . London, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Havens, T. , Lotz, A. D. , & Tinic, S. (2009). Critical media industry studies: A research approach. Communication, Culture and Critique , 2 (2), 234–253.

- Hesmondhalgh, D. , & Zoellner, A. (2013). Is media work good work? A case study of television documentary . In V. Mayer (Ed.), The international encyclopedia of media studies: Vol. II. Media production . London, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

- Horkhiemer, M. , & Adorno, T. (1997). Dialectic of enlightenment . New York: Verso. (Original work published 1944.)

- Iwabuchi, K. (2002). Recentering globalization: Popular culture and transnationalism . Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Jarrett, K. (2015). Feminism, labour and digital media: The digital housewife . London, UK: Routledge.

- Johnson, R. (1986). What is cultural studies anyway? Social Text , 16 , 38–80.

- Kong, L. , Gibson, C. , Khoo, L. M. , & Semple, A.-L. (2006). Knowledges of the creative economy: Towards a relational geography of diffusion and adaptation in Asia. Asia Pacific Viewpoint , 47 , 173–194.

- Larkin, B. (2008). Signal and noise: Media, infrastructure, and urban culture in Nigeria . Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Lent, J. (1994). A different road taken: Profiles in critical communication . Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Lobato, R. , & Thomas, J. (2015). The informal media economy . London, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Lukács, G. (1971). History and class consciousness: Studies in Marxist dialectics, Vol. 215 . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Markusen, A. (2014). Creative cities: A 10-year research agenda. Journal of Urban Affairs , 36 (s2), 567–589.

- Marx, K. (2007). Capital: A critique of political economy—The process of capitalist production . New York, NY: Cosimo Classics. (Original work published 1967.)

- Maxwell, R. , & Miller, T. (2012). Greening the media . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Mayer, V. (2011). Below the line: Producers and production studies in the new television economy . Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Mayer, V. (2017). Almost Hollywood, nearly New Orleans: The lure of the local film economy . Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Mayer, V. , Banks, M. J. , & Caldwell, J. T. (Eds.). (2009). Production studies: Cultural studies of media industries . London, UK and New York, NY: Routledge.

- Merton, R. K. (1968). Social theory and social structure . New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

- Miège, B. (1987). The logics at work in the new cultural industries. Media, Culture and Society , 9 (3), 273–289.

- Miller, J. (2016). Nollywood central . London, UK: British Film Institute.

- Miller, T. (2016). Workers of the world, unite, You have nothing to lose but your global (value) chains. In R. Maxwell (Ed.), The Routledge companion to labor and media (pp. 93–106). London, UK: Routledge.

- Miller, T. , & Ahluwalia, P. (2012). The cognitariat. Social Identities , 18 (3), 259–260.

- Mills, C. W. (1956). The power elite . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Mowlana, H. (1996). Global communication in transition: The end of diversity? London, UK: Sage.

- Murdock, G. (2003). Back to work: Cultural labor in altered times. In A. Beck (Ed.), Cultural work: Understanding cultural industries (pp. 15–36). London, UK: Routledge.

- Nakamura, L. (2014). Indigenous circuits: Navajo women and the racialization of early electronic manufacture. American Quarterly , 66 (4), 919–941.

- Negri, A. (1983) Social factory . New York, NY: Autonomedia.

- Oakley, K. (2004). Not so Cool Britannia: The role of creative industries in economic development. International Journal of Cultural Studies , 7 , 67–77.

- Oakley, K. , & O’Brien, D. (2015). Cultural value and inequality: A critical literature review . Report. Arts and Humanities Research Council, United Kingdom.

- O’Connor, J. (2012). Surrender to the void: Life after creative industries. Cultural Studies Review , 18 (3), 388–410.

- O’Connor, J. , & Xin, G. (2006). A new modernity: The arrival of creative industries in China. International Journal of Cultural Studies , 9 , 271–283.

- Ortner, S. (2009). Studying sideways: Ethnographic access in Hollywood. In V. Mayer , M. Banks , & J. Caldwell (Eds.), Production studies: Cultural studies of media industries (pp. 175–189). London, UK: Routledge.

- Pang, L. (2012). China’s creative industries and intellectual property rights offenses . Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Parks, L. , & Starosielski, N. (Eds.). (2015). Signal traffic: Critical studies of media infrastructures . Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Peterson, R. , & Anand, N. (2004). The production of culture perspective. Annual Review of Sociology , 30 , 311–334.

- Powdermaker, H. (1950). Hollywood, the dream factory: An anthropologist looks at the movie-makers . Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

- Punathambekar, A. (2013). From Bombay to Bollywood: The making of a global media industry . New York: NYU Press.

- Qiu, J. L. (2017). Goodbye iSlave: A manifesto for digital abolition . Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Scholz, T. (Ed.). (2013). The Internet as playground and factory . New York, NY: Routledge.

- Shade, L. R. , & Porter, N. (2008). Empire and sweatshop girlhoods: The two faces of the global culture industry. In K. Sarakakis & L. R. Shade (Eds.), Feminist interventions in international communication: Minding the gap (pp. 241–256). Boulder, CO: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Standing, G. (2011). The precariat: The new dangerous class . London, UK: Bloomsbury.

- Terranova, T. (2004). Network culture: Politics for the information age . London, UK: Pluto Press.

- Thussu, D. K. (2005). From MacBride to Murdoch: The marketisation of global communication. Javnost—The Public , 12 (3), 47–60.

- UNCTAD . (2008). Creative economy: Report 2008 .

- Wasko, J. (2015). Learning from the history of the field . Media Industries , 1 .

- Whitney, C. , & Ettema, J. (2003). Media production: Individuals, organizations, institutions. In A. Valdivia (Ed.), A companion to media studies (pp. 157–186). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Zukin, S. (1989). Loft living: Culture and capital in urban change . New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

1. The term media industries typically marks these approaches in the constitution of new interest groups within communication and media studies professional associations.

Related Articles

- Labor Politics in the Neoliberal Global Economy

- Political Economy of the Media

- Popular Culture and Cultural Studies

- Ideology in Marxist Traditions

- Ethics, Rhetoric, and Culture

- Queer Production Studies

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Communication. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 31 March 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.39.149.46]

- 185.39.149.46

Character limit 500 /500

How to Write a Creative Essay: Your Fresh Guide

What Is a Creative Essay

In a world full of logic, facts, and statistics, being able to unleash your true creativity might seem like a fresh breath of air. Sometimes, all we need is to shut our minds, let our thoughts flow through, and immerse ourselves in endless imagination. To think about it, being able to let your imagination run wild yields something genuinely exceptional, an outcome that is not restricted to mundane reality which eventually opens a whole new universe of broadened horizons.

Now, imagine that you can bring together your unique thoughts onto a piece of paper and organize them in a specific format, so when one reads through it, one can easily follow your points while simultaneously being captured by your set of perspectives. Notice how there is an intersection between creativity and organization? These two do not have to be mutually exclusive. That's why in this article we intend to explain how you can put your creative thoughts into words, arrange these words into paragraphs and finally structure these paragraphs in a well-defined creative essay outline.

Now that we have your undivided attention let us briefly explain what is a creative essay and what kind of assignment it represents when you're given one. A creative essay is more than just throwing words on paper to reach a certain character limit. Such an essay assesses your ability to discover and clarify notions to your audience. In academic writing, creative essays can provide you the chance to showcase your research ability together with your vocabulary and composition skills.

Nearly all educational levels, including universities, need students to produce creative essays. When picking creative essay topics, you often have great flexibility. Your professor may give you a subject or category to specialize in, but you are allowed to choose any concept as long as it fits the specified area.