This story is over 5 years old.

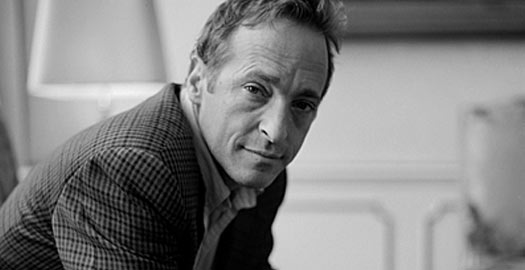

David sedaris talks about surviving the suicide of a sibling.

ORIGINAL REPORTING ON EVERYTHING THAT MATTERS IN YOUR INBOX.

By signing up, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy & to receive electronic communications from Vice Media Group, which may include marketing promotions, advertisements and sponsored content.

MPR News Reflections and observations on the news

David sedaris on his sister’s suicide.

Author David Sedaris has been relatively quiet about the suicide of his sister, Tiffany, since penning a New Yorker essay about it in 2013 that elicited a rebuke from his sister’s friend, and revealed the difficulty that families have trying to reach loved ones with mental illness.

But this week Sedaris opened up again in an interview in Vice magazine.

Anyone with a loved one with mental illness — I had an older brother, who died several years ago, who struggled — will recognize the pain that Sedaris tenderly describes. Loved ones reach out to help but are rebuffed and they’re left struggling with their own feelings of anger, continually trying to focus their anger on the illness, not the person with the illness. Sometimes you succeed; sometimes you don’t.

Even as a child I looked at my sister and wondered what that would be like, not to feel the warmth of my mother’s love. Tiffany didn’t. There was always a nervous quality about her, a tentativeness, a desperate urge to be in your good graces. While the rest of us had eyes in the front of our heads, she had eyes on the sides, like a rabbit or a deer, like prey, always on the lookout for danger. Even when there wasn’t any danger. You’d see her trembling and think, You want danger? I’ll give you some danger…

“We never knew what was going on with Tiffany and thought, at one point, of hiring a private detective to find out what her life was like,” he says.

They found out later she had been diagnosed as bipolar, though she described it as PTSD, and the trauma was her childhood.

He touches — too briefly — on the way his ill sister was treated.

There never seemed to be an innocent period with her, a period of dating or having a crush. She was sent away to a kind of reform school, a place called Élan [in Maine], when she was 14. Maybe she was innocent there and because we weren’t allowed to visit we missed it. It’s like she went in as a child and came out a hardened vamp.

Sedaris and Tiffany hadn’t talked for more than eight years up to her death.

He acknowledges he could try to learn more about who his sister was, but he can’t.

I would love to find out who she was. But I don’t have your skill, the skill to go out and talk to her friends, to hunt down people she went to Élan with and construct a concise portrait of her. We all wonder, my family and I. We talk about it all the time. We’d like to know how she survived. For close to 20 years Tiffany had a good deal on an apartment in Somerville. Her landlady was from China, Mrs. Yip, and for years my sister sang her praises. “Mrs. Yip, she’s the greatest. She’s teaching me tai chi!” Little by little Tiffany destroyed the apartment: pulled up the linoleum in the kitchen, overturned buckets of paint on the living-room floor, wrote on the walls. The tub was black, and the spare room was crowded floor to ceiling with junk. It became a complete wreck. This rental unit was Mrs. Yip’s retirement account. Somerville is full of students, and instead of renting to Tiffany for $1,000 a month, she could have been getting at least twice that, and having tenants who didn’t destroy the place. I don’t know what happened between my sister and Mrs. Yip, but at some point she stopped paying rent and claimed she’d put $25,000 worth of work into the apartment. There was an eviction notice. Tiffany took out a restraining order. It got ugly, and eventually she moved into a single room in a much worse part of town, and then into another single room.

After the New Yorker essay, it was easy to criticize Sedaris, as if there’s something he or the family could have done to help someone who didn’t want their help; as if they hadn’t constantly wondered if there’s something they hadn’t thought of. Sometimes the answer is “no.”

In order for things to be different, Tiffany would have had to be a completely different person. I mean, why not say, “Well, if she were four inches tall, and her name were Thumbelina, everything would have been fine.” I could not have saved Tiffany. If you don’t want to take your medication, there’s nothing anyone can do. There’s not a single day that I don’t think about her, though. She was a remarkable person.

There’s no indication in the piece that time has presented the Sedaris family with any new perspective on Tiffany’s life and death.

(h/t: Nikki Tundel)

About the blogger

Bob Collins

Bob Collins retired from Minnesota Public Radio in 2019 after 12 years of writing NewsCut and pointing out to complainants that posts weren’t news stories. A son of Massachusetts, he was a news editor 1992-1998, created the MPR News regional website in 1999, invented the popular Select A Candidate, started several blogs, and every day lamented that his Minnesota Fantasy Legislature project never caught on.

Latest from MPR News Blogs

Good night and good news, capitol view® - mpr news, politics friday: should we stop trusting pre-election polling.

Read This: David Sedaris on his sister’s suicide

David Sedaris’ self-deprecating humor has a poignant bent, especially when he’s talking about family: his long-time partner, Hugh; his younger brother, the Rooster; growing up in a large family in North Carolina. In May 2013, his younger sister Tiffany killed herself, and later that year, Sedaris published an essay in The New Yorker called “ Now We Are Five ,” addressing Tiffany’s bipolar disorder, their childhood together, and how, in many ways, he barely knew her.

Now, Sedaris has given an interview to Blake Bailey of Vice , who wrote a memoir featuring his own brother, Scott, who also killed himself. (That book, The Splendid Things We Planned , came out last March.) The two authors speak candidly about what it’s like to grow up with a sibling who has mental illness and what it means to write about deceased family members.

In Tiffany’s will, she stipulated that her family could not have her remains or come to her memorial service. Sedaris says:

Tiffany left all her belongings to a woman she once worked for who lives in New York State. Lisa called about maybe getting a cupful of ashes, and the woman said no. She was furious about this Dutch interview I gave. A couple months after Tiffany died, this Dutch film crew came to Sussex. They followed me around for several days, and toward the end of it, the interviewer kind of pulled up very close to me and said, “I know your sister recently committed suicide. So if you could say one thing to her, if she was here right now, what question would you ask?” And I said, “Can I have back that $6,000 that I loaned you?” I said it because the moment felt so cheesy: the lowered voice, the closeness. Certain people got bent out of shape over it, but come on. Tiffany was nothing if not funny. She would have been the first one to say something like that.

You can read the full interview at Vice .

- Out Newsletter

Search form

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use .

David Sedaris On His Sister's Suicide

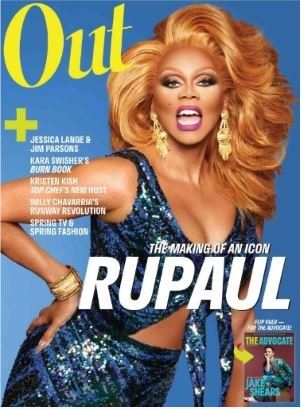

In a New Yorker essay, out essayist David Sedaris remembers his sister Tiffany while at the beach with his siblings

"The day before we arrived at the beach, Tiffany's obituary ran in the Raleigh News & Observer. It was submitted by Gretchen, who stated that our sister had passed away peacefully at her home. This made it sound as if she were very old, and had a house. But what else could you do? People were leaving responses on the paper's Web site, and one fellow wrote that Tiffany used to come into the video store where he worked in Somerville. When his glasses broke, she offered him a pair she had found while foraging for art supplies in somebody's trash can. He said that she also gave him a Playboy magazine from the nineteen-sixties that included a photo spread titled 'The Ass Menagerie.'"

Read the rest of the essay from The New Yorker here .

Want more breaking equality news & trending entertainment stories?

Check out our NEW 24/7 streaming service: the Advocate Channel!

Download the Advocate Channel App for your mobile phone and your favorite streaming device!

APPLE STORE - GOOGLE PLAY

ROKU - APPLE TV - FIRE TV - GOOGLE TV

From our Sponsors

Most popular.

38 Male Celebs Who Did Full Frontal Scenes

These are all the celebrities who came out as lgbtq+ in 2023, these pics prove maluma has always been a certified daddy, 32 lgbtq+ celebs you can follow on onlyfans, 26 actors who showed bare ass in movies & tv shows, 16 times celebrity men had to say they weren't gay, 21 lgbtq+ reality dating shows & where to watch them, 15 unforgettable gay kissing scenes from tv & movies, 14 queens who quit or retired from drag after 'rupaul's drag race', 40 steamy celebrity calvin klein ads we'll always be thirsty for, latest stories, did buck just have his first gay kiss on '9-1-1's 100th episode, orville peck opens up about why he changed up his mask for the new 'stampede' era, 'mary & george's nicholas galitzine loves his connection with lgbtq+ fans, celebrate 40 days of pride on west hollywood’s 40th anniversary, cute gay couples are sharing their love stories to beyoncé's 'ii most wanted' on tiktok, this video of omar apollo going absolutely feral on a couch makes us wish we were the couch, omar apollo yearns & jojo siwa officially enters her bad girl era: new music friday, april 5, 2024, 'drag race's tia kofi hard-launches relationship with mystery man, orville peck & willie nelson's new gay af music video is proof the yeehaw agenda is thriving, king tyra thinks beyoncé took his idea for a 'texas hold 'em' remix, which of our fave characters were forced to be in hetero couples here's what the internet thinks, celebrating trans resilience on tdov—and beyond, happy national foreskin day, jan calls out disgraced 'drag race' queen sherry pie's attempts at making a comeback, a timeline of every winner of 'rupaul's drag race' around the world, lizzo opens up about the real meaning behind her 'i quit' insta post, neil partick harris & david burtka just celebrated a milestone anniversary together, gay gym culture has a deadly downside, adult entertainment icons derek kage & cody silver lead fight for free speech, trending stories.

Joe Biden has tied the record for most LGBTQ+ judges confirmed in federal courts

Nashville PD Must Pay HIV-Positive Man Denied a Job

Not to be outdone by Trans Day of Visibility, Trump weirdly declares ‘Christian Visibility Day’

'Drag Race' star Q shares she's living with HIV

Exclusive: Stars shine bright at Elton John's AIDS Foundation Oscars party

Oklahoma voters recall white supremacist, reject supporters of Ryan Walters

EXCLUSIVE: Lady Bunny cutting ties, suing Bianca Del Rio

10 reasons why we STAN Pedro Pascal to celebrate his birthday

Equalpride's CEO on standing together this Transgender Day of Visibility

19 LGBTQ+ movies & TV shows coming in April 2024 & where to watch them

The trailer for this year’s coolest, queerest show is here and we’re already under its spell

Kansas Senate minority leader on recent anti-LGBTQ+ legislation: ‘It’s just filled with hate’

30 steamy pics of out celebrity stylist Johnny Wujek

The incredible ‘sacred’ waterfall you probably never knew existed

Tia Kofi & Hannah Conda dish on 'DRUKvTW' secrets, rivalries & have us CACKLING

France becomes world’s first country to enshrine abortion rights in constitution

'Drag Race's Morphine declares Miami a certified drag capital

Scarlet fever: exploring our fascination with blood

How climate disasters hurt mental health in young people

‘For the Love of DILF’s winners Nigel & Rico open up about their romance after the show (EXCLUSIVE)

United Nations adopts historic, first-ever resolution on rights of intersex people

8 dating tips for gay men from a gay therapist

All 6 rogue Mississippi cops got long prison sentences in 'Goon Squad' torture of 2 Black men

The Fall of the House of Ziegler: Moms for Liberty, a threesome, and a failed political dynasty

Why most GOP women are standing by their man

Most recent.

This iconic hardcore band once helped a trans friend pay for her surgery

The success of Matt Lynch: How a gay basketball coach led his team to victory

Spring into The Pride Store’s top new arrivals for April

Lara Trump awkwardly blames Biden’s support of trans people for high gas prices and Israel-Hamas war

Former Police Chief Among Three Arrested in Connection with Murder of Activist Marielle Franco

Breaking boundaries in gender-free fashion with Stuzo Clothing

16 Republican AGs threaten Maine over protections for trans care and abortion

Trump is no longer dog whistling and the internet is ruthlessly ROASTING him — as they should be

35 burly & beautiful pics from Bear Troop 69's inaugural Bear Jamboree at Gay Disney

Federal judge grants Casa Ruby founder Ruby Corado pre-trial release from D.C. jail

Election season got you down? This crisis line is soothing LGBTQ+ mental health

Common has a message on how to foster self-love

RuPaul reveals which actor should play him in a biopic & we're gagged

Opinion: I'm a climate scientist. If you knew what I know, you'd be terrified too

Find your perfect fit with gender-inclusive fashion from The Pride Store

A Ugandan LGBTQ+ activist was stabbed and left for dead in the street. Now, he recounts his escape to Canada

25 queer actors who should be starring in EVERYTHING

Bud Light boycott likely cost Anheuser-Busch InBev over $1 billion in lost sales

Here's why 'Drag Race' fans think Mistress just came out as nonbinary

LGBTQ+ patients twice as likely to face discrimination: survey

Recommended stories for you, matthew breen.

The Sneaky, Subversive Thrills of David Sedaris

The chronicler of dysfunctional families and oddball enthusiasms returns with a new essay collection, “Happy-Go-Lucky.”

Credit... Vincent Tullo for The New York Times

Supported by

- Share full article

By Henry Alford

- Published May 30, 2022 Updated June 22, 2023

- Apple Books

- Barnes and Noble

- Books-A-Million

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission.

HAPPY-GO-LUCKY , by David Sedaris

Listen to This Article

Open this article in the New York Times Audio app on iOS.

In the past five years, David Sedaris has published seven books — two essay collections; an anthology; two diaries, both more than 500 pages long; a visual compendium to the diaries; and an ebook version of an essay. Can an eponymous fragrance be far in the offing? (“Se- daring. For the imp in you.”)

Depending on your point of view, this onslaught — particularly given that Sedaris likes to revisit scenarios that he’s already written about — may strike you as either overgenerous or delightful. I fall into the latter camp, partly because “retention” is merely a word to me, and partly because I hold that the essential trait of a literary classic is that it is so textured that one can reread it and usually find something new.

Sedaris’s last collection, “Calypso,” practically destroyed me. Between the accounts of his troubled sister Tiffany, who died by suicide, and those of his father, who was begrudging and abusive to Sedaris throughout his life, I welled with tears four times. I chuckled frequently and projectile-laughed once. Most contemporary comic essayists have honed their powers of self-deprecation into excoriating, and sometimes exhausting, laser beams, but Sedaris is often willing to apply this same level of scrutiny to other people as well — and to do it without being nasty. For readers this can be eye-widening, and sometimes exciting, and surely is part of what makes Sedaris’s work such a sneaky, subversive thrill. Whether he’s detailing how his father, Lou, liked to eat food that he’d hidden around the house until it rotted, or he’s going off on homeless people in Portland, Sedaris dispenses with the parameters of You Can’t Say That like a tween boy scorching ants with a magnifying glass.

In my favorite type of Sedaris essay — the kind I’ll keep rereading — the author takes an unusual or taboo topic, such as death or incontinence, and then shows us how a group of flawed characters including himself circle around that topic; but then, in the last paragraph or two, he unleashes a blast of tenderness or humanity that catches you off guard. Take the new collection’s offering “Hurricane Season,” which, mostly set at Sedaris and his boyfriend Hugh’s beach houses in North Carolina, is about how spending time with our families can cause us to re-examine our relationships with our partners. Sedaris knows that his siblings are sometimes put off by Hugh: Each of them, at some point, has asked Sedaris, “What is his problem? ” Hugh, the guardian of manners and tradition among the wild-eyed and heathen Sedarii, is not afraid to snap or dole out punishment when one of them wears a down coat to the dinner table, or calls his chairs rickety, or feeds candy to ants. (Sedaris, the candyman, writes, “Gretchen patted my hand. ‘Don’t listen to Hugh. He doesn’t know [expletive] about being an ant.’”) But by essay’s end we find Hugh, after one of his and Sedaris’s houses is all but destroyed by Hurricane Florence, holed up in the bedroom, sobbing, his face in his hands, his shoulders quaking. We learn that three of the houses Hugh grew up in had also been destroyed. In such moments, Sedaris’s family has no jurisdiction: “They see me getting scolded from time to time, getting locked out of my own house, but where are they in the darkening rooms when a close friend dies or rebels storm the embassy? When the wind picks up and the floodwaters rise? When you realize you’d give anything to make that other person stop hurting, if only so he can tear your head off again?”

“Happy-Go-Lucky” has fewer of these beautifully crafted jewel boxes than “Calypso” did. However, in addition to being consistently funny, it contains some festive Sedaris occasions for all those who celebrate. We get a seeming resolution to Sedaris and his father’s lifelong grudge match when Lou tells David, “You won.” We get vivid moments featuring Lou’s will and Tiffany’s accusations of sexual abuse; Sedaris confesses to offering to pay for a 24-year-old store clerk to have his teeth fixed, and to long ago initiating a bizarre intergenerational family moment while wearing underpants that he’d cut the back out of. We also get the only truly offensive thing, to my knowledge, that Sedaris has ever written: “I cannot bear watching my sisters get old. It just seems cruel. They were all such beauties.”

Some of the pieces in “Happy-Go-Lucky” seem transitional, as if Sedaris, having already secured his place as a chronicler of dysfunctional families and oddball enthusiasms, is casting his net wider by taking on societal issues. This is a promising direction, but I missed Sedaris’s personal connection to the topics of guns and school shootings in an essay about those topics. Similarly, his essentially gothic bent, when applied to an ongoing crisis like the Covid-19 pandemic, can yield statements that whiff faintly of cabbage. (“The terrible shame about the pandemic in the United States is that more than 800,000 people have died to date, and I didn’t get to choose a one of them.”)

But when you’re dealing with a talent as outsize as Sedaris’s, even the missteps are fairly negligible — much like the author’s unusual ideas about how to cover the lower part of the body. I refer not to his artisanal underpants of yore, but rather to his penchant for wearing in public the benighted garment known as culottes. Let’s be honest here: This could be so much worse. It could be jeggings. It could be a merkin . Rather, the lasting impression of “Happy-Go-Lucky” is similar to that of Sedaris’s other books: It’s a neat trick that one writer’s preoccupation with the odd and the inappropriate can have such widespread appeal. As Sedaris once replied to a store employee who’d asked him if he was looking for anything special when gift shopping, “Grotesque is a plus.”

HAPPY-GO-LUCKY, by David Sedaris | 259 pp. | Little, Brown | $29

Henry Alford is the author of six books, including, most recently, “And Then We Danced.”

Audio produced by Tally Abecassis .

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

Stephen King, who has dominated horror fiction for decades , published his first novel, “Carrie,” in 1974. Margaret Atwood explains the book’s enduring appeal .

The actress Rebel Wilson, known for roles in the “Pitch Perfect” movies, gets vulnerable about her weight loss, sexuality and money in her new memoir.

“City in Ruins” is the third novel in Don Winslow’s Danny Ryan trilogy and, he says, his last book. He’s retiring in part to invest more time into political activism .

Jonathan Haidt, the social psychologist and author of “The Anxious Generation,” is “wildly optimistic” about Gen Z. Here’s why .

Do you want to be a better reader? Here’s some helpful advice to show you how to get the most out of your literary endeavor .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

Advertisement

Find anything you save across the site in your account

By David Sedaris

I was in Paris, waiting to undergo what promised to be a pretty disgusting medical procedure, when I got word that my father was dying. The hospital I was in had opened in 2000, but it seemed newer. From our vantage point in the second-floor radiology department, Hugh and I could see the cafés situated side by side in the modern, sun-filled concourse below. “It’s like an airline terminal,” he observed.

“Yes,” I said. “Terminal Illness.”

Under different circumstances, I might have described the place as cheerful. It was the wrong word to use, though, when I’d just had a CT scan and, in a few hours’ time, a doctor was scheduled to snake a multipurpose device up the hole in my penis. It was a sort of wire that took pictures, squirted water, and had little teeth. These would take bites out of my bladder, which would then be sent to a lab and biopsied. So “cheerful”? Not so much, at least for me.

I’d hoped to stick out in the radiology wing, to be too youthful or hale to fit in, but, looking around the waiting area, I saw that everyone was roughly my age, and either was bald or had gray hair. If anybody belonged here, it was me.

The good news was that the urologist I met with later that afternoon was loaded with personality. This made him the opposite of one I’d seen earlier that month, in London, when I’d gone in with an unmistakable urinary-tract infection. The pain was a giveaway, as was the blood that came out when I peed. U.T.I.s are common in women, but in men are usually a sign of something more serious. The London urologist was sullen and Scottish, the first to snake a multipurpose wire up my penis, but, sadly, not the last. The only time he came to life was when the camera started sending images to the monitor he was looking at. “Ah,” he trilled. “There’s your sphincter!”

I’ve always figured there was a reason my insides were on the inside: so I wouldn’t have to look at them. Therefore I said something noncommittal, like “Great!,” and went back to wishing that I were dead, because it really hurts to have a wire shoved up that narrow and uninviting slit.

The urologist we’d come to see in Paris looked over the results of the scan I’d just undergone and announced that they revealed nothing out of the ordinary. He also studied the results of the tests I’d had in London, including one for my prostate. My eyes had been screwed shut while it took place, but I’m fairly certain it involved forcing a Golden Globe Award up my ass. I didn’t cry or hit anyone, though. Thus it annoyed me to see what the English radiologist who’d performed the test had written in the comment section of his report: “Patient tolerated the trans-rectal probe poorly.”

How dare he! I thought.

In the end, a quick prostate check and the CT scan were the worst I had to suffer that day in Paris. After taking everything into consideration, the French doctor, who was young and handsome, like someone who’d play a doctor on TV, decided it wasn’t the right time to take little bites out of my bladder. “Better to give it another month,” he said, adding that I shouldn’t worry too much. “Were you younger, your urinary-tract infection might not have been an issue, but at your age it’s always best to be on the safe side.”

That evening, Hugh and I took the train back to London, and bought next-day plane tickets for the U.S. My father was by then in the intensive-care unit, where doctors were draining great quantities of ale-colored fluid from his lungs. His heart was failing, and he wasn’t expected to live much longer. “This could be it,” my sister Lisa wrote me in an e-mail.

The following morning, as we waited to board our flight, I learned that he’d been taken from intensive care and put in a regular hospital room.

By the time we arrived in Raleigh, my father was back at Springmoor, the assisted-living center he’d been in for the past year. I walked into his room at five in the afternoon and was unnerved by how thin and frail he was. Asleep, he looked long dead, like something unearthed from a pharaoh’s tomb. The head of his bed had been raised, so he was almost in a sitting position, his open mouth a dark, seemingly bottomless hole and his hands stretched out before him. The television was on, as always, but the sound was turned off.

“Are you looking for your sister?” an aide asked. She directed us down the hall, where a dozen people in wheelchairs sat watching “The Andy Griffith Show.” Just beyond them, in a grim, fluorescent-lit room, Lisa and my sister-in-law, Kathy, were talking to a hospice nurse they had recently engaged. “What’s Mr. Sedaris’s age?” the young woman asked, as Hugh and I took seats.

“He’ll be ninety-six in a few weeks,” Kathy said.

Lisa looked through her papers. “Five feet six.”

Really ? I thought. My father was never super-tall, but I’d assumed he was at least five-nine. Had he honestly shrunk that much?

More shuffling of papers.

“One-twenty,” Lisa answered.

“Well now he’s just showing off,” I said.

The hospice nurse needed to record my father’s blood pressure, so we went back to his room, where Kathy gently shook him awake. “Dad, were you napping?”

When he came to, my father focussed on Hugh. The tubes that had been put down his throat in the hospital had left him hoarse. Speaking was a challenge, thus his “Hey!” was hard to make out.

“We just arrived from England,” Hugh said.

My father responded enthusiastically, and I wondered why I couldn’t go over and kiss him, or at least say hello. Unless you count his hitting me, we were never terribly physical with each other, and I wasn’t sure I could begin at this late date.

Link copied

“I figured you’d rally as soon as I spent a fortune on last-minute tickets,” I said, knowing that if the situation were reversed he’d have stayed put, at least until a discount could be worked out. All he’s ever cared about is money, so it had hurt me to learn, a few years earlier, that he’d cut me out of his will. Had he talked it over with me, had he said, for example, that I seemed comfortable enough, it might have been different. But I heard about it secondhand. He’d wanted me to find out after he died. It would be like a scene in a movie, the wealthy man’s children crowded into the lawyer’s office: “And, to my son David, I leave nothing.”

When I confronted him about the will, he said he’d consider leaving me a modest sum, but only if I promised that Hugh would touch none of the money.

Of course I said no.

“Actually, don’t worry,” I said, of the plane tickets. “I’ll just pay for them with part of my inheritance . . . oops.”

“Awww, come on now,” he moaned. His voice was weak and soft, no louder than rustling leaves.

“I’m going to turn him over and examine his backside for bedsores,” the hospice nurse said. “So if any of y’all need to turn away . . .”

I was in the far corner of the room, beneath a painting my father had made in the late sixties of a monk with a mustache. Beside me was the guitar I was given in the fifth grade. “What’s this doing here?” I asked.

“Dad had it restrung a few months ago and said he was going to learn how to play,” Lisa told me. She pointed to a keyboard wedged behind a plaster statue of a joyful girl with her arms spread wide. “The piano, too.”

“ Now ?” I asked. “He’s had all this time but decided to wait until he was connected to tubes?”

After the hospice nurse had finished, my father’s dinner was brought in, all of it puréed, like baby food. Even his water was mixed with a thickener that gave it the consistency of nectar.

“He has a bone that protrudes from the back of his neck and causes food to go down the wrong way,” Lisa explained. “So he can’t have anything solid or liquid.”

As Kathy spooned the mush into my father’s mouth, Hugh picked the can of thickener up off the dinner tray, read the ingredients, and announced that it was just cornstarch.

“So how was your flight?” Lisa asked us.

Time crawled. Amber-colored urine slowly collected in the bag attached to my father’s catheter. The room was sweltering.

“Was that dinner O.K., Dad?” Lisa asked.

He raised a thumb. “Excellent.”

How had she and Paul and Kathy managed to do this day after day? Conversation was pretty much out of the question, so they mainly offered observations in louder than normal voices: “She was nice,” or “It looks like it might start raining again.”

I was relieved when my father got drowsy, and we could all leave and go to dinner. “Do you want me to turn your TV to Fox News?” Lisa asked, as we put our coats on.

“Fox News,” my father mumbled.

Lisa picked up the remote, but when she jabbed it in the direction of the television nothing happened. “I can’t figure out which channel that is, so why don’t you watch ‘ CSI: Miami ’ instead?”

Amy arrived from New York at ten the following morning, wearing a black-and-white polka-dot coat she’d bought on our last trip to Tokyo. Instead of taking her straight to Springmoor, Hugh and I drove her to my father’s place, where we met up with Lisa and Gretchen. Our dad started hoarding in the late eighties: a broken ceiling fan here, an expired can of peaches there, until eventually the stuff overtook him and spread into the yard. I hadn’t been inside the house since before he was moved to Springmoor, and, though Lisa had worked hard at clearing it of junk, the over-all effect was still jaw-dropping. His car, for instance, looked like the one in “ Silence of the Lambs ” that the decapitated head was found in. You’d think it had been made by spiders out of dust and old pollen. It was right outside the front door, and acted as an introduction to the horrors that awaited us.

“Whose turd is this on the floor next to the fireplace?” I called out, a few minutes after descending the filthy carpeted stairs into the basement.

Amy looked over my shoulder at it, as did Hugh and, finally, Lisa, who said, “It could be my dog’s from a few months ago.”

I leaned a bit closer. “Or it could be—”

Before I could finish, Hugh scooped it up with his bare hands and tossed it outside. “You people, my God.” Then he went upstairs to help Gretchen make lunch.

Continuing through the house, I kept asking the same question: “Why would anyone choose to live this way?” It wasn’t just the falling-down ceilings or the ragged spiderwebs draped like bunting over the doorways. It wasn’t the tools and appliances he’d found on various curbs—the vacuum cleaners with frayed cords or the shorted-out hair dryers he’d promised himself he would fix—but the sense of hopelessness they conveyed when heaped into rooms that used to seem so normal, no different in size or design from those of our neighbors, but were now ruined. “Whoever buys this house will just have to throw a match on it and start over,” Gretchen said.

What struck me most were my father’s clothes. Hugh gets after me for having too many, but I’ve got nothing compared with my dad, who must own twenty-five suits and twice as many sports coats. Dozens of them were from Brooks Brothers, when there was just the one store in New York and the name meant something. Others were from long-gone college shops in Ithaca and Syracuse, the sort that sold smart jackets and white bucks. There were sweaters in every shade: the cardigans on hangers, their sleeves folded in a self-embrace to prevent them from stretching; the V-necks and turtlenecks folded in stacks, a few unprotected, but mostly moth-proofed in plastic bags. There were polo shirts and dress shirts and casual shirts from every decade of postwar America. Some hung like rags—buttons missing, great tears in the backs, as if he’d worn them while running too slowly from bears. Others were still in their wrapping, likely bought two or three years ago. I could remember him wearing most of the older stuff—to the club, to work, to the parties he’d attend, always so handsome and stylish.

Though my mother’s clothes had been disposed of—all those shoulder pads moldering in some landfill—my father’s filled seven large closets, one of them a walk-in, and hung off the shower-curtain rods in all three bathrooms. They were crammed into dressers and piled on shelves. Hats and coats and scarves and gloves. Neckties and bow ties, too many to count, all owned by the man who since his retirement seemed to wear nothing but the same jeans and same T-shirt with holes in it he’d worn the day before, and the day before that; the man who’d always found an excuse to skimp on others, but allowed himself only the best. There were clothes from his self-described fat period, from the time he slimmed down, and from the years since my mother died, when he’s been out-and-out skinny: none of them thrown away or donated to Goodwill, and all of them now reeking of mildew.

I nicked a vibrant red button-down shirt from the fifties, noticing later that it had a sizable hole in the back. Then I claimed the camel-colored, moth-eaten beret I’d bought him on a school trip to Madrid in 1975.

“It suits you,” Hugh observed.

“It matches your skin and makes you look bald,” Amy said.

We were all in the dining room, going through boxes with more boxes in them, when I glanced over at the window and saw a doe step out of the woods and approach some of the trash on the lawn near the carport, head lowered, as if she’d followed the scent of fifty-year-old house paint hardened in rusted-through cans. “Look,” we whispered, afraid our voices from inside the house might frighten her off. “Isn’t she beautiful!” We couldn’t remember there being deer in the woods when we were young. Perhaps our dogs had scared them off.

“Oh,” Lisa said, her voice as soft as our father’s. “I hope she doesn’t step on a rusty nail.”

Gretchen served Greek food for lunch, and afterward we drove to Springmoor. It was a Saturday afternoon in late February, cold and raining. Our father was in his reclining chair covered with a blanket when we arrived, not asleep but not exactly awake, either. It was this new state he occasionally drifted into: neither here nor there. After killing the overhead lights, we seated ourselves around his room and continued the conversation we’d been having in the car.

“I asked Marshall to write Dad’s obituary, but he doesn’t feel up to it,” Gretchen said, referring to her boyfriend of nearly thirty years.

The rest of us glanced over at our father.

“He can’t hear us,” Gretchen said. She looked at me. “So will you write it?”

I’ve been writing about my father for ages, but when it comes to the details of his life, the year he graduated from college, etc., I’m worthless. Even his job remains a mystery to me. He was an engineer, and I like to joke that up until my late teens I thought that he drove a train. “I don’t really know all that much about him,” I said, scooting my chair closer to his recliner. He looked twenty years older than he had on my last visit to Raleigh, six months earlier. One change was his nose. The skin covering it was stretched tight, revealing facets I’d never before noticed. His eyes were shaped differently, like the diamonds you’d find on playing cards, and his mouth looked empty, though it was in fact filled with his own teeth. He did this thing now, opening wide and stretching out his lips, as if pantomiming a scream. I kept thinking it was in preparation for speech, but then he’d say nothing.

I was trying to push the obituary off on Lisa when we heard him call for water.

Hugh got a cup, filled it from the tap in the bathroom, and stirred in some cornstarch to thicken it. My father’s oxygen tube had fallen out of his nose, so we summoned a nurse, who showed us how to reattach it. When she left, he half raised his hand, which was purpled with spots and resembled a claw.

“What’s on your . . . mind?” he asked Amy, who had always been his favorite, and was seated a few yards away. His voice couldn’t carry for more than a foot or two, so Hugh repeated the question.

“What’s on your mind?”

“You,” Amy answered. “I’m just thinking of you and wanting you to feel better.”

My father looked up at the ceiling, and then at us. “Am I . . . real to you kids?” I had to lean in close to hear him, especially the last half of his sentences. After three seconds he’d run out of steam, and the rest was just breath. Plus the oxygen machine was loud.

“Are you what?”

“Real.” He gestured to his worn-out body, and the bag on the floor half filled with his urine. “I’m in this new . . . life now.”

“It’ll just take some getting used to,” Hugh said.

My father made a sour face. “I’m a zombie.”

I don’t know why I insisted on contradicting him. “Not really,” I said. “Zombies can walk and eat solid food. You’re actually more like a vegetable.”

“I know you,” my father said to me. He looked over at Amy, and at the spot that Gretchen had occupied until she left. “I know all you kids so well.”

I wanted to say that he knew us superficially at best. It’s how he’d have responded had I said as much to him: “You don’t know me.” Surely my sisters felt the way I did, but something—most likely fatigue—kept them from mentioning it.

As my father struggled to speak, I noticed his fingernails, which were long and dirty.

“If I just . . . dropped out of the sky like this . . . you’d think I was a freak.”

“No,” I said. “ You’d think you were a freak, or at least a loser.”

Amy nodded in agreement, and I plowed ahead. “It’s what you’ve been calling your neighbors here, the ones parked in the hall who can’t walk or feed themselves. It’s what you’ve always called weak people.”

“You’re a hundred per cent right,” he said.

I didn’t expect him to agree with me. “You’re vain,” I continued. “Always were. I was at the house this morning and couldn’t believe all the clothes you own. Now you’re this person, trapped in a chair, but you’re still yourself to us. You’re like . . . like you were a year ago, but drunk.”

“That’s a very astute . . . observation,” my father said. “Still, I’d like to . . . apologize.”

“For being in this condition?” I asked.

He looked over at Amy, as if she had asked the question, and nodded.

Then he turned to me. “David,” he said, as if he’d just realized who I was. “You’ve accomplished so many fantastic things in your life. You’re, well . . . I want to tell you . . . you . . . you won.”

A moment later he asked for more water, and drifted mid-sip into that neither-here-nor-there state. Paul arrived, and I went for a short walk, thinking, of course, about my father, and about the writer Russell Baker, who had died a few weeks earlier. He and I had had the same agent, a man named Don Congdon, who was in his mid-seventies when I met him, in 1994, and who used a lot of outdated slang. “The blower,” for instance, was what he called the phone, as in “Well, let me get off the blower. I’ve been gassing all morning.”

“Russ Baker’s mother was a tough old bird,” Don told me one rainy afternoon, in his office on Fifth Avenue. “A real gorgon to hear him tell it, always insisting that her son was a hack and would never amount to anything. So on her deathbed he goes to her saying, ‘Ma, look, I made it. I’m a successful writer for the New York Times . My last book won the Pulitzer.’ ”

“She looked up at him, her expression blank, and said, ‘Who are you?’ ”

I’ve been told since then that the story may not be true, but still it struck a nerve with me. Seek approval from the one person you desperately want it from, and you’re guaranteed not to get it.

As for my dad, I couldn’t tell if he meant “You won” as in “You won the game of life,” or “You won over me , your father, who told you—assured you when you were small and then kept reassuring you—that you were worthless.” Whichever way he intended those two faint words, I will take them, and, in doing so, throw down this lance I’ve been hoisting for the past sixty years. For I am old myself now, and it is so very, very heavy.

I returned to the room as Kathy was making dinner reservations at a restaurant she’d heard good things about. The menu was updated Southern: fried oysters served with pork belly and collard greens—that kind of thing. The place was full when we arrived, and the diners were dressed up. I was wearing the red shirt I’d taken from my father’s closet, and had grown increasingly self-conscious about how strongly it stank of mildew.

“We all smell like Dad’s house,” Amy noted.

While eating, we returned to the topic of his obituary, and what would follow. A Greek Orthodox funeral is a relatively sober affair, sort of like a Mass. I’d asked if I could speak at my mom’s, just so there’d be a personal touch. If I were to revisit what I read that morning in 1991, I’d no doubt cringe. That said, it was easy to celebrate my mother. Effortless. With my father, I’d have to take a different tone. “I remember the way he used to ram other cars at the grocery store when the drivers—who were always women—took the parking spots he wanted,” I could say. “Oh, and the time he found seventeen-year-old Lisa using his shower, and dragged her out naked.”

How could I reconcile that perpetual human storm cloud with the one I had spent the afternoon with, the one who never mentioned, and has never mentioned, the possibility of dying, who has taken everything life has thrown at him and found a way to deal with it. Me, on the other hand, after half a dozen medical tests involving the two holes below my waist, before even learning whether or not I had cancer, I’d decided I was tired of battling it. “Just let me die in peace,” I said to Hugh, after the French urologist stuck his finger up my ass.

Meanwhile, here was my father, tended to by aides, afforded no privacy whatsoever, and determined to get used to it. Where did that come from? I wondered, looking at my fried chicken as it was set before me. And how is it that none of his children, least of all me, inherited it?

Of all us kids, Paul was the only one to fight the do-not-resuscitate order. He wanted all measures taken to keep our father alive. “You have to understand,” he said over dinner. “Dad is my best friend.” He didn’t say it in a mawkish or dramatic way, but matter-of-factly, the way you might identify your car in a parking lot: “It’s that one there.” The relationship between my brother and my father has always been a mystery to my sisters and me. Is it the thickness of their skin? The fact that they’re both straight men? On the surface, it seems that all they do is yell at each other: “Shut up.” “Go to hell.” “Why don’t you just suck my dick.” It is the vocabulary of conflict, but with none of the hurt feelings or dark intent. While the rest of us may mourn our father’s passing, only Paul will truly grieve.

“Hey,” he said, taking an uneaten waffle off his daughter’s plate. “Did I tell you I just repainted my basement?” He found a picture on his phone and showed me what looked like a Scandinavian preschool, each wall a bold primary color.

“Let me see,” Amy said. I handed her the phone and she, in turn, passed it to Lisa. It then went by the spots where Gretchen and Tiffany would be if Tiffany hadn’t killed herself and Gretchen hadn’t fallen asleep at her boyfriend’s house earlier that evening, and on to Kathy, then to my niece, Maddy, and back to Paul.

We were the last party to leave the restaurant, and were standing out front in a light rain, when Amy pointed at the small brick house across the street. “Look,” she cried, “a naked lady!”

“Oh, my God,” we said, following her finger and lowering our voices the same way we’d done ten hours earlier with the doe on my father’s lawn.

“Where?” Lisa whispered.

“Right there, through the window on the ground floor,” Hugh told her. He and Amy would later remark that the woman, who was middle-aged and buxom and wore her hair in a style I associate with the nineteen-forties, made them think of a Raymond Chandler novel.

“What’s she doing?” I asked, watching as she moved into the kitchen.

“Getting a drink of water?” Lisa guessed.

Paul turned to his daughter. “Look away, Maddy!”

When the light went out, we worried that we had scared the naked woman, but a second later it came back on, and she was joined by a dark-haired man with a towel around his waist. The two of them appeared to speak for a moment. Then he took her by the hand and led her into another room and out of sight.

It was all we talked about as we made our way down the street to our various cars. “Can you believe it? Naked!!” As if we’d seen a flying saucer, or a congregation of pixies. To hear us in a gang like that, the wonder in our voices, the delight and energy, you’d almost think we were children. ♦

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Siddhartha Mukherjee

By Zach Williams

By Souvankham Thammavongsa

The Blood on Our Faces: A Response to David Sedaris

When the Star Tribune published findings from the Minnesota Department of Health showing that suicides had risen 13 percent overall from 2010 to 2011, I paid little notice. When a friend exclaimed, “You’ll never believe this!” before showing me a story of a man found dead in France , eight years after his apparent suicide, I was equally dismissive. But when I decided to read the latest New Yorker article by humorist David Sedaris, my indifference faded. He begins:

In late May of this year, a few weeks shy of her fiftieth birthday, my youngest sister, Tiffany, committed suicide.

This wasn’t the David Sedaris I knew. His essays, though at times infuriating, are always hysterically funny. They usually contain gems such as the following:

After a few months in my parents’ basement, I took an apartment near the state university, where I discovered both crystal methamphetamine and conceptual art. Either one of the these things are dangerous, but in combination they have the potential to destroy entire civilizations. -or- Follow seven beers with a couple of scotches and a thimble of good marijuana, and it’s funny how sleep just sort of comes on its own. Often I never even make it to bed. I’d squat down to pet the cat and wake up on the floor eight hours later, having lost a perfectly good excuse to change my clothes. I’m now told that this is not called “going to sleep” but rather “passing out,” a phrase that carries a distinct hint of judgment.

Sedaris has always tripped over darkness in his works. In an essay on smoking, he describes in careful detail a corpse in a coroner’s office. The coroner, knowing that both Sedaris and the man on the table were fans of cigarettes, hands the man’s blackened lung over, in the hope of creating a “moment.” Sedaris, rather than being inspired to change his smoking habit simply thought: “Damn, this lung is heavy.”

If he could get away with an easy laugh about death before, he doesn’t manage it in ‘ Now We Are Five ‘, the essay here in question. He notes that there will be some awkwardness in trying to explain the make up of his family to strangers;

Now, though, there weren’t six, only five. “And you can’t really say, ‘There used to be six,’ ” I told my sister Lisa. “It just makes people uncomfortable.” I recalled a father and son I’d met in California a few years back. “So are there other children?” I asked. “There are,” the man said. “Three who are living and a daughter, Chloe, who died before she was born, eighteen years ago.” That’s not fair, I remember thinking. Because, I mean, what’s a person supposed to do with that ?

But even this only deserves a grin. What comes through repeatedly as he and his family go on their usual vacation is that his sister’s suicide has fundamentally changed not only how he thinks of his family, but of himself;

A person expects his parents to die. But a sibling? I felt I’d lost the identity I’d enjoyed since 1968, when my younger brother was born.

The dysfunction of the Sedaris family, in David’s previous essays, served as the source of humor. Here, though the same relationships are being examined, Sedaris strikes a more somber tone:

We didn’t really know our sister very well. Each of us had pulled away from the family at some point in our lives—we’d had to in order to forge our own identities, to go from being a Sedaris to being our own specific Sedaris. Tiffany, though, stayed away. She might promise to come home for Christmas, but at the last minute there’d always be some excuse: she missed her plane, she had to work. The same would happen with our summer vacations. “The rest of us managed to make it,” I’d say, aware of how old and guilt-trippy I sounded.

Whether or not he intended this, I began to wonder at the family politics I’ve experienced in my life. What would those little snide comments or broken promises have looked like if a member of my family had killed themselves? I have no reason to think they would, but the hypothetical raises certain questions. Surely, since my family is Catholic and the Sedaris’s aren’t, we would have the spiritual resources to cope. But would we? As I wondered to myself, I was reminded about a dinner discussion I had a few months ago. For almost no reason at all, the question of suicide and God’s mercy came up.

“It is perfectly possible for God to act in the time it takes for a bullet to travel down a barrel.” I said to Dan (not his real name). “Maybe, but let’s ask what suicide actually is. It is a rejection of God’s plan for your life. That’s a mortal sin.” he replied. “Perhaps, but mortal sin needs full knowledge, plus full consent and a grave matter. Suicide is certainly a grave matter, but given what we know about various psychological problems, it seems unlikely that there would be full consent of the will.” “Yes, but John, you’re claiming that you know the whole story about what is going on here. It’s not good to give people, even the friends of people who have committed suicide, false hope. The plain fact is we don’t know what happens to their souls. All we know is God gave them life and they refused the gift.”

I don’t know what Dan’s motivations were in our conversation. I certainly hoped I was after the true nature of God’s mercy, but I couldn’t be sure. In a sense Dan was right, I was claiming to know the whole story. What I knew, and what Dan didn’t, was that one of our mutual friends at the table had attempted suicide a few years previously. With every word Dan spoke, our friend sank a little lower in his chair. I’d like to think I was accurately describing God’s mercy, but I was also trying to ease my friend’s pain as much as possible. I suspected, and later learned, that he was very close to losing it if the discussion had continued much longer.

My questions remain poignant. For his part, Sedaris has his own questions.

“Why do you think she did it?” I asked as we stepped back into the sunlight. For that’s all any of us were thinking, had been thinking since we got the news. Mustn’t Tiffany have hoped that whatever pills she’d taken wouldn’t be strong enough, and that her failed attempt would lead her back into our fold? How could anyone purposefully leave us, us , of all people? This is how I thought of it, for though I’ve often lost faith in myself, I’ve never lost it in my family, in my certainty that we are fundamentally better than everyone else. It’s an archaic belief, one that I haven’t seriously reconsidered since my late teens, but still I hold it. Ours is the only club I’d ever wanted to be a member of, so I couldn’t imagine quitting. Backing off for a year or two was understandable, but to want out so badly that you’d take your own life? “I don’t know that it had anything to do with us,” my father said. But how could it have not? Doesn’t the blood of every suicide splash back on our faces?

The question of suicide, then, is really a bunch of questions bundled together. What is the value of human life? Who is ultimately responsible for it? What does justice demand? What about mercy? Who is responsible? Who isn’t? What could we have done? What are we to do now?

These are questions I cannot answer. They surpass all the wit I can summon and the learning I can recall. Judging by the tone of his essay, they must be weighing heavily on Sedaris as well. But when faced with the insurmountable questions raised by suicide, I end up in a place Sedaris doesn’t. Because the nature of these problems demands an answer, and because neither I nor anyone I’ve found has been able to provide one, I look elsewhere. Thus, David’s essay leads me right back to a place which he himself has (in other writings) rejected, namely, to the truth and necessity of the Christian faith.

No comments yet

Name (required)

Mail (will not be published) (required)

Related Reads

The Advance of Gender Ideology in Europe

Episcopal Church Presiding Bishop Nominees Announced

Methodist Retreat, British & American

Talking Peace, Promoting War

The work of IRD is made possible by your generous contributions.

Receive expert analysis in your inbox.

Institute on Religion and Democracy 1023 15th Street NW, Suite 200 Washington, DC 20005 Contact us | Media requests

© 2024 The Institute on Religion and Democracy. All rights reserved.

- Northern Ireland

- Hurling & Camogie

- GAA Fixtures & Results

- Personal Finance

- Holidays & Travel

- Food & Drink

- Irish Language

- Entertainment

- Opens in new window

David Sedaris: The real tragedy of my sister’s suicide was her mental illness

David Sedaris says writing about his younger sister’s death by suicide was not difficult, and that the real “tragedy” was the mental illness she suffered from.

The US writer and broadcaster said he had thought about his sister, Tiffany, every day since her death, describing her as a “dynamic, beautiful and funny” person.

Sedaris is known for his humorous collections of stories and essays based on his own life.

Speaking on BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs he discussed his turbulent relationships with his family, including his mother’s alcoholism and father’s refusal to accept his sexuality.

Abba thanks fans for ‘steadfast loyalty’ on 50th anniversary of Eurovision win

Yellowstone actor’s nephew who was suspect in police probe is found dead

Following his sister’s death in 2013, he wrote a book, titled Now We Are Five.

Asked by Lauren Laverne if the book had been difficult to write, he replied: “No. The thing is, it was inevitable.

“It was almost something that you had already written, all you needed were the particulars, like the method of suicide and time of year.”

He continued: “It’s so interesting to me, I wrote about it, and then I’ve gotten so many letters from people who have lost a member of their family, and everyone assumes that we’re plagued by guilt.

“I’ve never met anybody who feels guilty. It’s always the same… The tragedy wasn’t my sister’s suicide, it was her mental illness.

“She left behind some notebooks and reading the notebooks you think ‘wow, if that was the inside of my mind’.”

Sedaris and his sister had been estranged for some time before her death, though he still praised her as a “very dynamic person” who he had loved showing off to his friends.

“She could really just say something to you that would just destroy you, reach inside your soul, and find your weak spot… She couldn’t listen to people and then she became combative and became super contradictory,” he said.

“The last time I saw my sister, I was on tour, and she came to the theatre and came to the stage door. I was like, ‘whatever you’re going to throw at me right now. I can’t right now. I can’t carry that right now’.”

He added: “There were times in my life, like when I moved to Chicago, and Tiffany came to visit me there.

“I had that feeling with her like ‘this is my sister’ – (I was) just so proud of her, (she was) just so beautiful and so funny and so vibrant. And then everything fell apart.”

Opening up about his relationship with his father he admitted that he had not felt bad when he had passed away.

“It sounds monstrous,” he said.

“I know that there are a lot of people for whom that’s their attitude… you shouldn’t speak ill of the dead.

“Why not? Is that the rule? You can treat someone however you want, and they can never talk about it – they can’t say ‘thank God, that’s over’ – you kind of get what you pay for.”

The new series of the writer’s own BBC Radio 4 show, Meet David Sedaris, starts on on February 23 at 6.30pm.

Desert Island Discs airs on Sunday on BBC Sounds and BBC Radio 4, at 11.15am.

The Apprentice: Final five to battle it out at gruelling interviews stage

Megan McKenna reveals she is expecting her first child with fiance Oliver Burke

6 new podcasts to listen to this week

Sir Mark Rylance and Damian Lewis return in first look at Wolf Hall sequel

Should you take a break from social media to look after your mental health?

Kiernan Shipka remembers late co-star Chance Perdomo as ‘one-of-a-kind soul’

David Sedaris on his sister’s suicide

Author David Sedaris has been relatively quiet about the suicide of his sister, Tiffany, since penning a New Yorker essay about it in 2013 that elicited a rebuke from his sister's friend, and revealed the difficulty that families have trying to reach loved ones with mental illness.

But this week Sedaris opened up again in an interview in Vice magazine.

Anyone with a loved one with mental illness -- I had an older brother, who died several years ago, who struggled -- will recognize the pain that Sedaris tenderly describes. Loved ones reach out to help but are rebuffed and they're left struggling with their own feelings of anger, continually trying to focus their anger on the illness, not the person with the illness. Sometimes you succeed; sometimes you don't.

Create a More Connected Minnesota

MPR News is your trusted resource for the news you need. With your support, MPR News brings accessible, courageous journalism and authentic conversation to everyone - free of paywalls and barriers. Your gift makes a difference.

Even as a child I looked at my sister and wondered what that would be like, not to feel the warmth of my mother's love. Tiffany didn't. There was always a nervous quality about her, a tentativeness, a desperate urge to be in your good graces. While the rest of us had eyes in the front of our heads, she had eyes on the sides, like a rabbit or a deer, like prey, always on the lookout for danger. Even when there wasn't any danger. You'd see her trembling and think, You want danger? I'll give you some danger...

"We never knew what was going on with Tiffany and thought, at one point, of hiring a private detective to find out what her life was like," he says.

They found out later she had been diagnosed as bipolar, though she described it as PTSD, and the trauma was her childhood.

He touches -- too briefly -- on the way his ill sister was treated.

There never seemed to be an innocent period with her, a period of dating or having a crush. She was sent away to a kind of reform school, a place called Élan [in Maine], when she was 14. Maybe she was innocent there and because we weren't allowed to visit we missed it. It's like she went in as a child and came out a hardened vamp.

Sedaris and Tiffany hadn't talked for more than eight years up to her death.

He acknowledges he could try to learn more about who his sister was, but he can't.

I would love to find out who she was. But I don't have your skill, the skill to go out and talk to her friends, to hunt down people she went to Élan with and construct a concise portrait of her. We all wonder, my family and I. We talk about it all the time. We'd like to know how she survived. For close to 20 years Tiffany had a good deal on an apartment in Somerville. Her landlady was from China, Mrs. Yip, and for years my sister sang her praises. "Mrs. Yip, she's the greatest. She's teaching me tai chi!" Little by little Tiffany destroyed the apartment: pulled up the linoleum in the kitchen, overturned buckets of paint on the living-room floor, wrote on the walls. The tub was black, and the spare room was crowded floor to ceiling with junk. It became a complete wreck. This rental unit was Mrs. Yip's retirement account. Somerville is full of students, and instead of renting to Tiffany for $1,000 a month, she could have been getting at least twice that, and having tenants who didn't destroy the place. I don't know what happened between my sister and Mrs. Yip, but at some point she stopped paying rent and claimed she'd put $25,000 worth of work into the apartment. There was an eviction notice. Tiffany took out a restraining order. It got ugly, and eventually she moved into a single room in a much worse part of town, and then into another single room.

After the New Yorker essay, it was easy to criticize Sedaris, as if there's something he or the family could have done to help someone who didn't want their help; as if they hadn't constantly wondered if there's something they hadn't thought of. Sometimes the answer is "no."

In order for things to be different, Tiffany would have had to be a completely different person. I mean, why not say, "Well, if she were four inches tall, and her name were Thumbelina, everything would have been fine." I could not have saved Tiffany. If you don't want to take your medication, there's nothing anyone can do. There's not a single day that I don't think about her, though. She was a remarkable person.

There's no indication in the piece that time has presented the Sedaris family with any new perspective on Tiffany's life and death.

(h/t: Nikki Tundel)

- The future of NewsCut? We need your thoughts

- Good night and good news

- Storytime with Bob: A treat outside of the blog

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Author Interviews

David sedaris on the 'sea section' and his new book, 'calypso'.

Author David Sedaris speaks to NPR's Lulu Garcia-Navarro about family, love, loss and his new book called Calypso.

LULU GARCIA-NAVARRO, HOST:

David Sedaris bought a beach house. And it's called the Sea Section. This would normally not be a thing to hang a book of personal essays on. But this is David Sedaris, and so it's about a lot more than vacations. In 2013, Sedaris's sister Tiffany committed suicide.

DAVID SEDARIS: (Reading) Why do you think she did it? I asked as we stepped back into the sunlight, for that's all any of us were thinking - had been thinking since we got the news. Mustn't Tiffany have hoped that whatever pills she'd taken wouldn't be strong enough? And that her failed attempt would lead her back into our fold? How could anyone purposefully leave us - us of all people? This is how I thought of it. For though I've often lost faith in myself, I've never lost faith in my family and my certainty that we are fundamentally better than everyone else.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: In his new book "Calypso," he talks about her death, his family, aging and how he picks up trash in his spare time while wearing a Fitbit. Those last two are not unrelated. David Sedaris joins us now from New York. Welcome.

SEDARIS: Thank you for having me, Lulu.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: I guess I'd like to start by saying the Sea Section is a great name for a beach house.

SEDARIS: Well, we just bought the house next to our house because what happens is people tear down the building. And then they build what they called sandcastles. I guess you'd call them McMansions. Anyway, so we bought the house next to our house. And that has a pretty dumb name, too, so we want to change it. And so I came up with some things. And then I was at a reading one day. And I said, what do you think are some good names? And a woman wrote and she suggested Canker Shores...

GARCIA-NAVARRO: (Laughter).

SEDARIS: ...Or the Amniotic Shack...

SEDARIS: ...Both of which are great beach house names.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: Those are great beach house names. Have you chosen which one yet?

SEDARIS: I go back and forth because the beach houses used to all have pun names, like Crabba Dabba Doo and Clamelot, right? And a lot of the new ones - they have names like Dolphin Song or, you know, God's Promise. So I just thought it was much better when they were pun names.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: This book is many things. As I mentioned, it's a meditation on aging and on loss and family. But as we mentioned, hanging over it all is the suicide of your sister. Can you tell me about Tiffany?

SEDARIS: Well, she was my youngest sister. And she committed suicide just before she turned 50. And - but she was the only one in the family really who sort of backed off from the family. And the rest of us - we all came home for Christmas. And we all came home for summer vacations. And - but Tiffany was the only one who - well, I have to work. Well, something came up. I can't come. And, you know, she had a lot of, you know, mental problems. And she didn't want to take her medication, so she didn't. And then her life just got more and more out of control. And then she committed suicide in 2013.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: Were you surprised when you heard?

SEDARIS: I was surprised when I heard. But then she left behind some notebooks. And when I look through the notebooks, I think, well, gosh, if that was my mind, if that's the way that I thought, I can understand wanting to put yourself out of that misery. Her thoughts were so disjointed. And even the note that we eventually found - the suicide note that she left - it was just so convoluted and so - it didn't make any sense. When you thought, well, gosh. Why would a person commit suicide over that? So - and I hadn't - she was a very difficult person. She had a lot of very intense friendships that would end with a restraining order.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: There are some very funny segments in this book, of course. But the one that I really liked was when your sister Amy goes to a psychic and contacts your dead sister. And the message that she brings back struck me so true of siblings. Basically, even from beyond the grave, the message from Tiffany was irritating. She was (laughter) - you were irritated by what apparently the medium had said she was saying.

SEDARIS: Right. The message was basically, I forgive you. When it's like, you forgive me? Like, I'm the one who is supposed to be forgiving you. But then the psychic said - I mean, I don't believe in things like that, right? But Amy has a pretty open mind. So she went to this psychic. And the psychic said that Tiffany had been trying to contact me, right? And she said, have you had a lot of - has your phone been acting up? And I said no. And then she said, have you seen a lot of butterflies? And it was shocking to me because our house that winter was loaded with butterflies in the winter. And what happens is on the second floor of our house in England, there's a big, tall loft ceiling. So butterflies come in at the end of the summer. And they just sort of hibernate up there. And then when you turn the heat on in the winter, they think it's spring. And they come and they bat themselves against the windows. But they were - I don't know. There must have been - there were dozens and dozens and dozens of butterflies in our house. And...

GARCIA-NAVARRO: And a psychic knew that? Or said it?

SEDARIS: The psychic said that that was one of the signs that Tiffany was trying to contact me with these butterflies. And I don't necessarily - I still don't believe in the psychic. And I don't believe in anything that she said. But I hate it when you don't believe in something and then something makes you wonder if maybe you're wrong. I'd just rather...

SEDARIS: ...I would just rather close my mind against something and just have it settled.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: You wrote, though, in your book that your sister and your mother visit you in your sleep.

SEDARIS: I don't believe in ghosts. But I do believe that dead people can visit you when you're asleep. I mean, I have had visits with my mother. And again, I don't believe in ghosts. But - and my sister Tiffany, too. And I have to say it's so comforting. And it just makes you feel like, you know, caught up and makes you feel loved. But I look forward to visiting people after I'm dead. And not to say, where's that money you owe me?

GARCIA-NAVARRO: I was about to say, what were you - you want to visit with them to reminisce? Maybe not...

SEDARIS: Just to catch up.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: Another theme in this book is your own aging. And you write, it's just a matter of time before our luck runs out, and one of us gets cancer. Then we will be picked off like figures in a shooting gallery, easy targets given the lives that we've led. So that's cheery. Do you feel guilty for having had a great life?

SEDARIS: No, I don't, as a matter of fact. I mean, I know people who do feel guilty. And I'm not one of them. So no. I mean, that line, though, pertains to, like, my brother and my sisters. I just - gosh. That's going to be - I don't know how I'll live with that. You know, I - it's odd when a sibling dies. And to this day, people say, oh, how many kids are in your family? And I say, oh, six. And I don't say five - there used to be six - because then you don't want people to feel weird. And in my mind, there are still six. But I can't imagine, like, when I say, oh, two. There are two left. Or, oh, I'm the last. You know, when you meet people, and they're the last of their siblings, I don't know how you carry on. I really don't. But when I look forward like that and I try to conceive of that - of life without my siblings - life without my boyfriend. Yeah, I'll take it. But life without my siblings is just unfathomable to me.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: That's David Sedaris. His new book is "Calypso." Thank you so much.

SEDARIS: Oh, thank you.

Copyright © 2018 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

- Entertainment

Shopping for the Perfect Shirt With Writer David Sedaris

D avid Sedaris is on the hunt for a specific type of shirt. “I’m old now and can’t wear anything too thin,” he explains to a store clerk. “It accentuates my man-breasts.”

Sedaris has led me to 45R, a Japanese boutique he first shopped at in Tokyo before discovering a stateside outpost here on Mercer Street in New York City. The front of the store smells like soothing incense, but toward the back there’s a statue of a naked child clutching a piece of fruit in one hand while throwing the other hand victoriously into the air. It’s just the kind of playfully bizarre decoration that Sedaris loves.

“Is your father still alive?” Sedaris asks the young clerk. Yes, the clerk says. He just turned 58.

“So he has breasts, doesn’t he?” asks the writer. The clerk nods and laughs.

When Sedaris, 61, shares intimate details of his life, he forges a bond with millions of readers and audience members, including now this clerk who busies himself finding a flattering shirt. In his early essay collections, Sedaris wrote about the homophobic speech therapy he was forced to endure as a child, his experimentation with drugs and his stint working as a Santaland elf at Macy’s . He recorded his unusual obsessions with taxidermied owls and foreign swear words. He always carries a notebook with him, and scribbles down observations that he later crafts into humorous stories. (He even tests out the notebook in various shirt pockets during our shopping trip to make sure it will fit.)

Sedaris has mined his past for eight memoirs’ worth of material, including a collection of old diary entries published last year under the title Theft by Finding . But in his newest essay collection, Calypso , out now, he looks to the present and the future. “Though there’s an industry built on telling you otherwise, there are few real joys to middle age,” the book begins. He has found some perks: he spent his 20s broke but now lives in the English countryside with his boyfriend Hugh, in a house with a guest room, the kind Sedaris fantasized about as a younger man.

The couple also recently purchased a cottage by the seaside in North Carolina and named it the Sea Section. Much of Calypso takes place in this new beach home. There, he and his siblings clash with their father over politics, and at one point Sedaris feeds a benign tumor he had removed from his body to a sea turtle—just because. But there are many downsides to growing old. Sedaris’ body is slowly deteriorating, which perhaps has led to his fanatical obsession with his Fitbit.

When Sedaris and I meet in the late morning, he has already logged almost 9,000 of the recommended 10,000 steps for the day. “If I were a lazy person, I would just walk another 1,000 steps and say I’m done,” he says. “But I’m not a lazy person.” His record is 91,000 steps in one day.

At home in England, he meets his goals by wandering through his neighborhood for hours at a time, picking up litter on the side of the road as he goes. Sedaris is the first to admit that he easily becomes consumed by routines. As a student in Chicago, he used to arrive at the same IHOP and sit in the same booth to drink the same cup of coffee at the exact same time every day. Now he has channeled his self-described obsessive-compulsive disorder into a green, if dangerous, project: as we walk alongside busy Houston Street, Sedaris spots a trash bag filled with Styrofoam tumbling into the road. He runs into oncoming traffic to grab it.

Sedaris doesn’t exaggerate his peculiarities on paper to earn a few laughs. In person, he’s the same neurotic and charming guy that his faithful readers know so well. And yet in Calypso, he occasionally drops his trademark humor in favor of meditations on regret and mortality.

Sedaris has previously written about his mother in reverent tones: her six children vied for her attention, and she held court at the dinner table every night. She even coached a young Sedaris on how to tweak his anecdotes to make them funnier. But in the considered and brutally honest Calypso essay “Why Aren’t You Laughing?,” Sedaris admits that he regrets that he never confronted his mother about her alcoholism.

In an essay titled “The Spirit World,” Sedaris remembers his last interaction with his sister Tiffany before she died by suicide. The two had a difficult relationship and had not spoken for four years when she appeared unannounced at one of his readings in Boston. She called to him from the stage door to the theater. Sedaris ignored her, turned to a nearby security guard and asked him to shut the door. He never saw her again.

“I feel the audience giving me the appropriate reaction when I talk about shutting the door in her face,” says Sedaris of reading that essay aloud on his book tour. “They didn’t expect that, and then they have to recalibrate their feeling toward me. When I read that the first time, I thought, Do I really want to admit this? But it seemed false not to. If you try to make yourself look better than you are, that’s bad. Especially if you’re making other people look bad, you have to be up-front about how bad you are.”

Sedaris says he doesn’t regret anything he’s ever written. But he does dislike his early work. Back then, he didn’t have the luxury of reading stories aloud in front of an audience dozens of times and then tweaking the language before publication. “Everything in my first four or five books I would completely rewrite,” he says. “I sign those books sometimes, and I think, Whatever is in here cannot be good.”

Sedaris’ performances are essential to his craft. During his years at the Art Institute of Chicago, he reveled in the laughs he would get from his fellow students during workshops. These days, he reads essays aloud on tour, marks down the audience’s reactions to certain sentences, returns to his hotel room to revise the story and then adjusts the delivery the next night. He read each of the essays in Calypso onstage at least 50 times before the book was published. He loves performing for an audience and even schedules tours when he doesn’t have a new book to promote.