Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

12.1 Creating a Rough Draft for a Research Paper

Learning objectives.

- Apply strategies for drafting an effective introduction and conclusion.

- Identify when and how to summarize, paraphrase, and directly quote information from research sources.

- Apply guidelines for citing sources within the body of the paper and the bibliography.

- Use primary and secondary research to support ideas.

- Identify the purposes for which writers use each type of research.

At last, you are ready to begin writing the rough draft of your research paper. Putting your thinking and research into words is exciting. It can also be challenging. In this section, you will learn strategies for handling the more challenging aspects of writing a research paper, such as integrating material from your sources, citing information correctly, and avoiding any misuse of your sources.

The Structure of a Research Paper

Research papers generally follow the same basic structure: an introduction that presents the writer’s thesis, a body section that develops the thesis with supporting points and evidence, and a conclusion that revisits the thesis and provides additional insights or suggestions for further research.

Your writing voice will come across most strongly in your introduction and conclusion, as you work to attract your readers’ interest and establish your thesis. These sections usually do not cite sources at length. They focus on the big picture, not specific details. In contrast, the body of your paper will cite sources extensively. As you present your ideas, you will support your points with details from your research.

Writing Your Introduction

There are several approaches to writing an introduction, each of which fulfills the same goals. The introduction should get readers’ attention, provide background information, and present the writer’s thesis. Many writers like to begin with one of the following catchy openers:

- A surprising fact

- A thought-provoking question

- An attention-getting quote

- A brief anecdote that illustrates a larger concept

- A connection between your topic and your readers’ experiences

The next few sentences place the opening in context by presenting background information. From there, the writer builds toward a thesis, which is traditionally placed at the end of the introduction. Think of your thesis as a signpost that lets readers know in what direction the paper is headed.

Jorge decided to begin his research paper by connecting his topic to readers’ daily experiences. Read the first draft of his introduction. The thesis is underlined. Note how Jorge progresses from the opening sentences to background information to his thesis.

Beyond the Hype: Evaluating Low-Carb Diets

I. Introduction

Over the past decade, increasing numbers of Americans have jumped on the low-carb bandwagon. Some studies estimate that approximately 40 million Americans, or about 20 percent of the population, are attempting to restrict their intake of food high in carbohydrates (Sanders and Katz, 2004; Hirsch, 2004). Proponents of low-carb diets say they are not only the most effective way to lose weight, but they also yield health benefits such as lower blood pressure and improved cholesterol levels. Meanwhile, some doctors claim that low-carb diets are overrated and caution that their long-term effects are unknown. Although following a low-carbohydrate diet can benefit some people, these diets are not necessarily the best option for everyone who wants to lose weight or improve their health.

Write the introductory paragraph of your research paper. Try using one of the techniques listed in this section to write an engaging introduction. Be sure to include background information about the topic that leads to your thesis.

Writers often work out of sequence when writing a research paper. If you find yourself struggling to write an engaging introduction, you may wish to write the body of your paper first. Writing the body sections first will help you clarify your main points. Writing the introduction should then be easier. You may have a better sense of how to introduce the paper after you have drafted some or all of the body.

Writing Your Conclusion

In your introduction, you tell readers where they are headed. In your conclusion, you recap where they have been. For this reason, some writers prefer to write their conclusions soon after they have written their introduction. However, this method may not work for all writers. Other writers prefer to write their conclusion at the end of the paper, after writing the body paragraphs. No process is absolutely right or absolutely wrong; find the one that best suits you.

No matter when you compose the conclusion, it should sum up your main ideas and revisit your thesis. The conclusion should not simply echo the introduction or rely on bland summary statements, such as “In this paper, I have demonstrated that.…” In fact, avoid repeating your thesis verbatim from the introduction. Restate it in different words that reflect the new perspective gained through your research. That helps keep your ideas fresh for your readers. An effective writer might conclude a paper by asking a new question the research inspired, revisiting an anecdote presented earlier, or reminding readers of how the topic relates to their lives.

Writing at Work

If your job involves writing or reading scientific papers, it helps to understand how professional researchers use the structure described in this section. A scientific paper begins with an abstract that briefly summarizes the entire paper. The introduction explains the purpose of the research, briefly summarizes previous research, and presents the researchers’ hypothesis. The body provides details about the study, such as who participated in it, what the researchers measured, and what results they recorded. The conclusion presents the researchers’ interpretation of the data, or what they learned.

Using Source Material in Your Paper

One of the challenges of writing a research paper is successfully integrating your ideas with material from your sources. Your paper must explain what you think, or it will read like a disconnected string of facts and quotations. However, you also need to support your ideas with research, or they will seem insubstantial. How do you strike the right balance?

You have already taken a step in the right direction by writing your introduction. The introduction and conclusion function like the frame around a picture. They define and limit your topic and place your research in context.

In the body paragraphs of your paper, you will need to integrate ideas carefully at the paragraph level and at the sentence level. You will use topic sentences in your paragraphs to make sure readers understand the significance of any facts, details, or quotations you cite. You will also include sentences that transition between ideas from your research, either within a paragraph or between paragraphs. At the sentence level, you will need to think carefully about how you introduce paraphrased and quoted material.

Earlier you learned about summarizing, paraphrasing, and quoting when taking notes. In the next few sections, you will learn how to use these techniques in the body of your paper to weave in source material to support your ideas.

Summarizing Sources

When you summarize material from a source, you zero in on the main points and restate them concisely in your own words. This technique is appropriate when only the major ideas are relevant to your paper or when you need to simplify complex information into a few key points for your readers.

Be sure to review the source material as you summarize it. Identify the main idea and restate it as concisely as you can—preferably in one sentence. Depending on your purpose, you may also add another sentence or two condensing any important details or examples. Check your summary to make sure it is accurate and complete.

In his draft, Jorge summarized research materials that presented scientists’ findings about low-carbohydrate diets. Read the following passage from a trade magazine article and Jorge’s summary of the article.

Assessing the Efficacy of Low-Carbohydrate Diets

Adrienne Howell, Ph.D.

Over the past few years, a number of clinical studies have explored whether high-protein, low-carbohydrate diets are more effective for weight loss than other frequently recommended diet plans, such as diets that drastically curtail fat intake (Pritikin) or that emphasize consuming lean meats, grains, vegetables, and a moderate amount of unsaturated fats (the Mediterranean diet). A 2009 study found that obese teenagers who followed a low-carbohydrate diet lost an average of 15.6 kilograms over a six-month period, whereas teenagers following a low-fat diet or a Mediterranean diet lost an average of 11.1 kilograms and 9.3 kilograms respectively. Two 2010 studies that measured weight loss for obese adults following these same three diet plans found similar results. Over three months, subjects on the low-carbohydrate diet plan lost anywhere from four to six kilograms more than subjects who followed other diet plans.

In three recent studies, researchers compared outcomes for obese subjects who followed either a low-carbohydrate diet, a low-fat diet, or a Mediterranean diet and found that subjects following a low-carbohydrate diet lost more weight in the same time (Howell, 2010).

A summary restates ideas in your own words—but for specialized or clinical terms, you may need to use terms that appear in the original source. For instance, Jorge used the term obese in his summary because related words such as heavy or overweight have a different clinical meaning.

On a separate sheet of paper, practice summarizing by writing a one-sentence summary of the same passage that Jorge already summarized.

Paraphrasing Sources

When you paraphrase material from a source, restate the information from an entire sentence or passage in your own words, using your own original sentence structure. A paraphrased source differs from a summarized source in that you focus on restating the ideas, not condensing them.

Again, it is important to check your paraphrase against the source material to make sure it is both accurate and original. Inexperienced writers sometimes use the thesaurus method of paraphrasing—that is, they simply rewrite the source material, replacing most of the words with synonyms. This constitutes a misuse of sources. A true paraphrase restates ideas using the writer’s own language and style.

In his draft, Jorge frequently paraphrased details from sources. At times, he needed to rewrite a sentence more than once to ensure he was paraphrasing ideas correctly. Read the passage from a website. Then read Jorge’s initial attempt at paraphrasing it, followed by the final version of his paraphrase.

Dieters nearly always get great results soon after they begin following a low-carbohydrate diet, but these results tend to taper off after the first few months, particularly because many dieters find it difficult to follow a low-carbohydrate diet plan consistently.

People usually see encouraging outcomes shortly after they go on a low-carbohydrate diet, but their progress slows down after a short while, especially because most discover that it is a challenge to adhere to the diet strictly (Heinz, 2009).

After reviewing the paraphrased sentence, Jorge realized he was following the original source too closely. He did not want to quote the full passage verbatim, so he again attempted to restate the idea in his own style.

Because it is hard for dieters to stick to a low-carbohydrate eating plan, the initial success of these diets is short-lived (Heinz, 2009).

On a separate sheet of paper, follow these steps to practice paraphrasing.

- Choose an important idea or detail from your notes.

- Without looking at the original source, restate the idea in your own words.

- Check your paraphrase against the original text in the source. Make sure both your language and your sentence structure are original.

- Revise your paraphrase if necessary.

Quoting Sources Directly

Most of the time, you will summarize or paraphrase source material instead of quoting directly. Doing so shows that you understand your research well enough to write about it confidently in your own words. However, direct quotes can be powerful when used sparingly and with purpose.

Quoting directly can sometimes help you make a point in a colorful way. If an author’s words are especially vivid, memorable, or well phrased, quoting them may help hold your reader’s interest. Direct quotations from an interviewee or an eyewitness may help you personalize an issue for readers. And when you analyze primary sources, such as a historical speech or a work of literature, quoting extensively is often necessary to illustrate your points. These are valid reasons to use quotations.

Less experienced writers, however, sometimes overuse direct quotations in a research paper because it seems easier than paraphrasing. At best, this reduces the effectiveness of the quotations. At worst, it results in a paper that seems haphazardly pasted together from outside sources. Use quotations sparingly for greater impact.

When you do choose to quote directly from a source, follow these guidelines:

- Make sure you have transcribed the original statement accurately.

- Represent the author’s ideas honestly. Quote enough of the original text to reflect the author’s point accurately.

- Never use a stand-alone quotation. Always integrate the quoted material into your own sentence.

- Use ellipses (…) if you need to omit a word or phrase. Use brackets [ ] if you need to replace a word or phrase.

- Make sure any omissions or changed words do not alter the meaning of the original text. Omit or replace words only when absolutely necessary to shorten the text or to make it grammatically correct within your sentence.

- Remember to include correctly formatted citations that follow the assigned style guide.

Jorge interviewed a dietician as part of his research, and he decided to quote her words in his paper. Read an excerpt from the interview and Jorge’s use of it, which follows.

Personally, I don’t really buy into all of the hype about low-carbohydrate miracle diets like Atkins and so on. Sure, for some people, they are great, but for most, any sensible eating and exercise plan would work just as well.

Registered dietician Dana Kwon (2010) admits, “Personally, I don’t really buy into all of the hype.…Sure, for some people, [low-carbohydrate diets] are great, but for most, any sensible eating and exercise plan would work just as well.”

Notice how Jorge smoothly integrated the quoted material by starting the sentence with an introductory phrase. His use of ellipses and brackets did not change the source’s meaning.

Documenting Source Material

Throughout the writing process, be scrupulous about documenting information taken from sources. The purpose of doing so is twofold:

- To give credit to other writers or researchers for their ideas

- To allow your reader to follow up and learn more about the topic if desired

You will cite sources within the body of your paper and at the end of the paper in your bibliography. For this assignment, you will use the citation format used by the American Psychological Association (also known as APA style). For information on the format used by the Modern Language Association (MLA style), see Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” .

Citing Sources in the Body of Your Paper

In-text citations document your sources within the body of your paper. These include two vital pieces of information: the author’s name and the year the source material was published. When quoting a print source, also include in the citation the page number where the quoted material originally appears. The page number will follow the year in the in-text citation. Page numbers are necessary only when content has been directly quoted, not when it has been summarized or paraphrased.

Within a paragraph, this information may appear as part of your introduction to the material or as a parenthetical citation at the end of a sentence. Read the examples that follow. For more information about in-text citations for other source types, see Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” .

Leibowitz (2008) found that low-carbohydrate diets often helped subjects with Type II diabetes maintain a healthy weight and control blood-sugar levels.

The introduction to the source material includes the author’s name followed by the year of publication in parentheses.

Low-carbohydrate diets often help subjects with Type II diabetes maintain a healthy weight and control blood-sugar levels (Leibowitz, 2008).

The parenthetical citation at the end of the sentence includes the author’s name, a comma, and the year the source was published. The period at the end of the sentence comes after the parentheses.

Creating a List of References

Each of the sources you cite in the body text will appear in a references list at the end of your paper. While in-text citations provide the most basic information about the source, your references section will include additional publication details. In general, you will include the following information:

- The author’s last name followed by his or her first (and sometimes middle) initial

- The year the source was published

- The source title

- For articles in periodicals, the full name of the periodical, along with the volume and issue number and the pages where the article appeared

Additional information may be included for different types of sources, such as online sources. For a detailed guide to APA or MLA citations, see Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” . A sample reference list is provided with the final draft of Jorge’s paper later in this chapter.

Using Primary and Secondary Research

As you write your draft, be mindful of how you are using primary and secondary source material to support your points. Recall that primary sources present firsthand information. Secondary sources are one step removed from primary sources. They present a writer’s analysis or interpretation of primary source materials. How you balance primary and secondary source material in your paper will depend on the topic and assignment.

Using Primary Sources Effectively

Some types of research papers must use primary sources extensively to achieve their purpose. Any paper that analyzes a primary text or presents the writer’s own experimental research falls in this category. Here are a few examples:

- A paper for a literature course analyzing several poems by Emily Dickinson

- A paper for a political science course comparing televised speeches delivered by two presidential candidates

- A paper for a communications course discussing gender biases in television commercials

- A paper for a business administration course that discusses the results of a survey the writer conducted with local businesses to gather information about their work-from-home and flextime policies

- A paper for an elementary education course that discusses the results of an experiment the writer conducted to compare the effectiveness of two different methods of mathematics instruction

For these types of papers, primary research is the main focus. If you are writing about a work (including nonprint works, such as a movie or a painting), it is crucial to gather information and ideas from the original work, rather than relying solely on others’ interpretations. And, of course, if you take the time to design and conduct your own field research, such as a survey, a series of interviews, or an experiment, you will want to discuss it in detail. For example, the interviews may provide interesting responses that you want to share with your reader.

Using Secondary Sources Effectively

For some assignments, it makes sense to rely more on secondary sources than primary sources. If you are not analyzing a text or conducting your own field research, you will need to use secondary sources extensively.

As much as possible, use secondary sources that are closely linked to primary research, such as a journal article presenting the results of the authors’ scientific study or a book that cites interviews and case studies. These sources are more reliable and add more value to your paper than sources that are further removed from primary research. For instance, a popular magazine article on junk-food addiction might be several steps removed from the original scientific study on which it is loosely based. As a result, the article may distort, sensationalize, or misinterpret the scientists’ findings.

Even if your paper is largely based on primary sources, you may use secondary sources to develop your ideas. For instance, an analysis of Alfred Hitchcock’s films would focus on the films themselves as a primary source, but might also cite commentary from critics. A paper that presents an original experiment would include some discussion of similar prior research in the field.

Jorge knew he did not have the time, resources, or experience needed to conduct original experimental research for his paper. Because he was relying on secondary sources to support his ideas, he made a point of citing sources that were not far removed from primary research.

Some sources could be considered primary or secondary sources, depending on the writer’s purpose for using them. For instance, if a writer’s purpose is to inform readers about how the No Child Left Behind legislation has affected elementary education, a Time magazine article on the subject would be a secondary source. However, suppose the writer’s purpose is to analyze how the news media has portrayed the effects of the No Child Left Behind legislation. In that case, articles about the legislation in news magazines like Time , Newsweek , and US News & World Report would be primary sources. They provide firsthand examples of the media coverage the writer is analyzing.

Avoiding Plagiarism

Your research paper presents your thinking about a topic, supported and developed by other people’s ideas and information. It is crucial to always distinguish between the two—as you conduct research, as you plan your paper, and as you write. Failure to do so can lead to plagiarism.

Intentional and Accidental Plagiarism

Plagiarism is the act of misrepresenting someone else’s work as your own. Sometimes a writer plagiarizes work on purpose—for instance, by purchasing an essay from a website and submitting it as original course work. In other cases, a writer may commit accidental plagiarism due to carelessness, haste, or misunderstanding. To avoid unintentional plagiarism, follow these guidelines:

- Understand what types of information must be cited.

- Understand what constitutes fair use of a source.

- Keep source materials and notes carefully organized.

- Follow guidelines for summarizing, paraphrasing, and quoting sources.

When to Cite

Any idea or fact taken from an outside source must be cited, in both the body of your paper and the references list. The only exceptions are facts or general statements that are common knowledge. Common-knowledge facts or general statements are commonly supported by and found in multiple sources. For example, a writer would not need to cite the statement that most breads, pastas, and cereals are high in carbohydrates; this is well known and well documented. However, if a writer explained in detail the differences among the chemical structures of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, a citation would be necessary. When in doubt, cite.

In recent years, issues related to the fair use of sources have been prevalent in popular culture. Recording artists, for example, may disagree about the extent to which one has the right to sample another’s music. For academic purposes, however, the guidelines for fair use are reasonably straightforward.

Writers may quote from or paraphrase material from previously published works without formally obtaining the copyright holder’s permission. Fair use means that the writer legitimately uses brief excerpts from source material to support and develop his or her own ideas. For instance, a columnist may excerpt a few sentences from a novel when writing a book review. However, quoting or paraphrasing another’s work at excessive length, to the extent that large sections of the writing are unoriginal, is not fair use.

As he worked on his draft, Jorge was careful to cite his sources correctly and not to rely excessively on any one source. Occasionally, however, he caught himself quoting a source at great length. In those instances, he highlighted the paragraph in question so that he could go back to it later and revise. Read the example, along with Jorge’s revision.

Heinz (2009) found that “subjects in the low-carbohydrate group (30% carbohydrates; 40% protein, 30% fat) had a mean weight loss of 10 kg (22 lbs) over a 4-month period.” These results were “noticeably better than results for subjects on a low-fat diet (45% carbohydrates, 35% protein, 20% fat)” whose average weight loss was only “7 kg (15.4 lbs) in the same period.” From this, it can be concluded that “low-carbohydrate diets obtain more rapid results.” Other researchers agree that “at least in the short term, patients following low-carbohydrate diets enjoy greater success” than those who follow alternative plans (Johnson & Crowe, 2010).

After reviewing the paragraph, Jorge realized that he had drifted into unoriginal writing. Most of the paragraph was taken verbatim from a single article. Although Jorge had enclosed the material in quotation marks, he knew it was not an appropriate way to use the research in his paper.

Low-carbohydrate diets may indeed be superior to other diet plans for short-term weight loss. In a study comparing low-carbohydrate diets and low-fat diets, Heinz (2009) found that subjects who followed a low-carbohydrate plan (30% of total calories) for 4 months lost, on average, about 3 kilograms more than subjects who followed a low-fat diet for the same time. Heinz concluded that these plans yield quick results, an idea supported by a similar study conducted by Johnson and Crowe (2010). What remains to be seen, however, is whether this initial success can be sustained for longer periods.

As Jorge revised the paragraph, he realized he did not need to quote these sources directly. Instead, he paraphrased their most important findings. He also made sure to include a topic sentence stating the main idea of the paragraph and a concluding sentence that transitioned to the next major topic in his essay.

Working with Sources Carefully

Disorganization and carelessness sometimes lead to plagiarism. For instance, a writer may be unable to provide a complete, accurate citation if he didn’t record bibliographical information. A writer may cut and paste a passage from a website into her paper and later forget where the material came from. A writer who procrastinates may rush through a draft, which easily leads to sloppy paraphrasing and inaccurate quotations. Any of these actions can create the appearance of plagiarism and lead to negative consequences.

Carefully organizing your time and notes is the best guard against these forms of plagiarism. Maintain a detailed working bibliography and thorough notes throughout the research process. Check original sources again to clear up any uncertainties. Allow plenty of time for writing your draft so there is no temptation to cut corners.

Citing other people’s work appropriately is just as important in the workplace as it is in school. If you need to consult outside sources to research a document you are creating, follow the general guidelines already discussed, as well as any industry-specific citation guidelines. For more extensive use of others’ work—for instance, requesting permission to link to another company’s website on your own corporate website—always follow your employer’s established procedures.

Academic Integrity

The concepts and strategies discussed in this section of Chapter 12 “Writing a Research Paper” connect to a larger issue—academic integrity. You maintain your integrity as a member of an academic community by representing your work and others’ work honestly and by using other people’s work only in legitimately accepted ways. It is a point of honor taken seriously in every academic discipline and career field.

Academic integrity violations have serious educational and professional consequences. Even when cheating and plagiarism go undetected, they still result in a student’s failure to learn necessary research and writing skills. Students who are found guilty of academic integrity violations face consequences ranging from a failing grade to expulsion from the university. Employees may be fired for plagiarism and do irreparable damage to their professional reputation. In short, it is never worth the risk.

Key Takeaways

- An effective research paper focuses on the writer’s ideas. The introduction and conclusion present and revisit the writer’s thesis. The body of the paper develops the thesis and related points with information from research.

- Ideas and information taken from outside sources must be cited in the body of the paper and in the references section.

- Material taken from sources should be used to develop the writer’s ideas. Summarizing and paraphrasing are usually most effective for this purpose.

- A summary concisely restates the main ideas of a source in the writer’s own words.

- A paraphrase restates ideas from a source using the writer’s own words and sentence structures.

- Direct quotations should be used sparingly. Ellipses and brackets must be used to indicate words that were omitted or changed for conciseness or grammatical correctness.

- Always represent material from outside sources accurately.

- Plagiarism has serious academic and professional consequences. To avoid accidental plagiarism, keep research materials organized, understand guidelines for fair use and appropriate citation of sources, and review the paper to make sure these guidelines are followed.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

The Writing Process

Making expository writing less stressful, more efficient, and more enlightening, search form, step 3: draft.

“It is an unnecessary burden to try to think of words and also worry at the same time whether they’re the right words.” — Peter Elbow

There are many reasons that people (including native speakers) find writing difficult, but one of the biggest is that when we write our papers, we are often trying to do two things at once:

- To say them in the best possible way (i.e., perfectly), with correct grammar and elegant wording

These are two complex but very different mental processes. No wonder writing can seem difficult. Add to this a third obstacle ,

- To write in a foreign language

and you might think it’s a wonder that you can write at all!

There is a simple solution, however, namley to separate these processes into distinct steps. Namely, when writing your first draft, just focus on getting the ideas roughly into sentences . Don't worry too much about grammar, spelling, or even ideal vocabulary. You can not worry for three reasons :

- If you are writing expository papers, your English is probably now at a fairly high level, so it will actually be difficult for you to make too many mistakes;

- You have already outlined your ideas, working with the language and finding much accurate vocabulary there, meaning that you're not working from scratch but rather building on something you are already familiar with . Now you're just putting it in sentence and paragraph form;

And the third and biggest reason:

- The term “Draft” (instead of “Write”) implicitly contains the awareness that you will have other drafts in the future , meaning that you know that this one will be revised and edited in later steps.

Just let the ideas flow into sentences as though you are pouring concrete into wooden frame; you'll smooth it out later.

Thus when drafting, simpy do the following:

- Either print out your detailed outline and have it in front of you, or have it on the left side of your computer screen and your draft document on the right.

- Do write complete sentences and paragraphs, and try moderately to use proper grammar, accurate wording, and transition words to link your ideas as necessary.

- However, almost as in freewriting, don't let yourself get stuck . You may pause for a few seconds, but don't labor over sentences. Just get them down and move on.

- Even without worrying excessively about grammar, putting your ideas in sentence form will not always be easy. Ideas can be complex and difficult to express, and even native English speakers must struggle sometimes to say (or even know!) exactly what they mean, so don't expect yourself to be able to do it the first time.

- Let yourself write freely and feel the satisfaction of 1) getting a draft done, and then 2) crafting it to say what you want to say the way you want say it.

Click to watch a short video modeling how to write a draft.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Yale J Biol Med

- v.84(3); 2011 Sep

Focus: Education — Career Advice

How to write your first research paper.

Writing a research manuscript is an intimidating process for many novice writers in the sciences. One of the stumbling blocks is the beginning of the process and creating the first draft. This paper presents guidelines on how to initiate the writing process and draft each section of a research manuscript. The paper discusses seven rules that allow the writer to prepare a well-structured and comprehensive manuscript for a publication submission. In addition, the author lists different strategies for successful revision. Each of those strategies represents a step in the revision process and should help the writer improve the quality of the manuscript. The paper could be considered a brief manual for publication.

It is late at night. You have been struggling with your project for a year. You generated an enormous amount of interesting data. Your pipette feels like an extension of your hand, and running western blots has become part of your daily routine, similar to brushing your teeth. Your colleagues think you are ready to write a paper, and your lab mates tease you about your “slow” writing progress. Yet days pass, and you cannot force yourself to sit down to write. You have not written anything for a while (lab reports do not count), and you feel you have lost your stamina. How does the writing process work? How can you fit your writing into a daily schedule packed with experiments? What section should you start with? What distinguishes a good research paper from a bad one? How should you revise your paper? These and many other questions buzz in your head and keep you stressed. As a result, you procrastinate. In this paper, I will discuss the issues related to the writing process of a scientific paper. Specifically, I will focus on the best approaches to start a scientific paper, tips for writing each section, and the best revision strategies.

1. Schedule your writing time in Outlook

Whether you have written 100 papers or you are struggling with your first, starting the process is the most difficult part unless you have a rigid writing schedule. Writing is hard. It is a very difficult process of intense concentration and brain work. As stated in Hayes’ framework for the study of writing: “It is a generative activity requiring motivation, and it is an intellectual activity requiring cognitive processes and memory” [ 1 ]. In his book How to Write a Lot: A Practical Guide to Productive Academic Writing , Paul Silvia says that for some, “it’s easier to embalm the dead than to write an article about it” [ 2 ]. Just as with any type of hard work, you will not succeed unless you practice regularly. If you have not done physical exercises for a year, only regular workouts can get you into good shape again. The same kind of regular exercises, or I call them “writing sessions,” are required to be a productive author. Choose from 1- to 2-hour blocks in your daily work schedule and consider them as non-cancellable appointments. When figuring out which blocks of time will be set for writing, you should select the time that works best for this type of work. For many people, mornings are more productive. One Yale University graduate student spent a semester writing from 8 a.m. to 9 a.m. when her lab was empty. At the end of the semester, she was amazed at how much she accomplished without even interrupting her regular lab hours. In addition, doing the hardest task first thing in the morning contributes to the sense of accomplishment during the rest of the day. This positive feeling spills over into our work and life and has a very positive effect on our overall attitude.

Rule 1: Create regular time blocks for writing as appointments in your calendar and keep these appointments.

2. start with an outline.

Now that you have scheduled time, you need to decide how to start writing. The best strategy is to start with an outline. This will not be an outline that you are used to, with Roman numerals for each section and neat parallel listing of topic sentences and supporting points. This outline will be similar to a template for your paper. Initially, the outline will form a structure for your paper; it will help generate ideas and formulate hypotheses. Following the advice of George M. Whitesides, “. . . start with a blank piece of paper, and write down, in any order, all important ideas that occur to you concerning the paper” [ 3 ]. Use Table 1 as a starting point for your outline. Include your visuals (figures, tables, formulas, equations, and algorithms), and list your findings. These will constitute the first level of your outline, which will eventually expand as you elaborate.

The next stage is to add context and structure. Here you will group all your ideas into sections: Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion/Conclusion ( Table 2 ). This step will help add coherence to your work and sift your ideas.

Now that you have expanded your outline, you are ready for the next step: discussing the ideas for your paper with your colleagues and mentor. Many universities have a writing center where graduate students can schedule individual consultations and receive assistance with their paper drafts. Getting feedback during early stages of your draft can save a lot of time. Talking through ideas allows people to conceptualize and organize thoughts to find their direction without wasting time on unnecessary writing. Outlining is the most effective way of communicating your ideas and exchanging thoughts. Moreover, it is also the best stage to decide to which publication you will submit the paper. Many people come up with three choices and discuss them with their mentors and colleagues. Having a list of journal priorities can help you quickly resubmit your paper if your paper is rejected.

Rule 2: Create a detailed outline and discuss it with your mentor and peers.

3. continue with drafts.

After you get enough feedback and decide on the journal you will submit to, the process of real writing begins. Copy your outline into a separate file and expand on each of the points, adding data and elaborating on the details. When you create the first draft, do not succumb to the temptation of editing. Do not slow down to choose a better word or better phrase; do not halt to improve your sentence structure. Pour your ideas into the paper and leave revision and editing for later. As Paul Silvia explains, “Revising while you generate text is like drinking decaffeinated coffee in the early morning: noble idea, wrong time” [ 2 ].

Many students complain that they are not productive writers because they experience writer’s block. Staring at an empty screen is frustrating, but your screen is not really empty: You have a template of your article, and all you need to do is fill in the blanks. Indeed, writer’s block is a logical fallacy for a scientist ― it is just an excuse to procrastinate. When scientists start writing a research paper, they already have their files with data, lab notes with materials and experimental designs, some visuals, and tables with results. All they need to do is scrutinize these pieces and put them together into a comprehensive paper.

3.1. Starting with Materials and Methods

If you still struggle with starting a paper, then write the Materials and Methods section first. Since you have all your notes, it should not be problematic for you to describe the experimental design and procedures. Your most important goal in this section is to be as explicit as possible by providing enough detail and references. In the end, the purpose of this section is to allow other researchers to evaluate and repeat your work. So do not run into the same problems as the writers of the sentences in (1):

1a. Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation. 1b. To isolate T cells, lymph nodes were collected.

As you can see, crucial pieces of information are missing: the speed of centrifuging your bacteria, the time, and the temperature in (1a); the source of lymph nodes for collection in (b). The sentences can be improved when information is added, as in (2a) and (2b), respectfully:

2a. Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation at 3000g for 15 min at 25°C. 2b. To isolate T cells, mediastinal and mesenteric lymph nodes from Balb/c mice were collected at day 7 after immunization with ovabumin.

If your method has previously been published and is well-known, then you should provide only the literature reference, as in (3a). If your method is unpublished, then you need to make sure you provide all essential details, as in (3b).

3a. Stem cells were isolated, according to Johnson [23]. 3b. Stem cells were isolated using biotinylated carbon nanotubes coated with anti-CD34 antibodies.

Furthermore, cohesion and fluency are crucial in this section. One of the malpractices resulting in disrupted fluency is switching from passive voice to active and vice versa within the same paragraph, as shown in (4). This switching misleads and distracts the reader.

4. Behavioral computer-based experiments of Study 1 were programmed by using E-Prime. We took ratings of enjoyment, mood, and arousal as the patients listened to preferred pleasant music and unpreferred music by using Visual Analogue Scales (SI Methods). The preferred and unpreferred status of the music was operationalized along a continuum of pleasantness [ 4 ].

The problem with (4) is that the reader has to switch from the point of view of the experiment (passive voice) to the point of view of the experimenter (active voice). This switch causes confusion about the performer of the actions in the first and the third sentences. To improve the coherence and fluency of the paragraph above, you should be consistent in choosing the point of view: first person “we” or passive voice [ 5 ]. Let’s consider two revised examples in (5).

5a. We programmed behavioral computer-based experiments of Study 1 by using E-Prime. We took ratings of enjoyment, mood, and arousal by using Visual Analogue Scales (SI Methods) as the patients listened to preferred pleasant music and unpreferred music. We operationalized the preferred and unpreferred status of the music along a continuum of pleasantness. 5b. Behavioral computer-based experiments of Study 1 were programmed by using E-Prime. Ratings of enjoyment, mood, and arousal were taken as the patients listened to preferred pleasant music and unpreferred music by using Visual Analogue Scales (SI Methods). The preferred and unpreferred status of the music was operationalized along a continuum of pleasantness.

If you choose the point of view of the experimenter, then you may end up with repetitive “we did this” sentences. For many readers, paragraphs with sentences all beginning with “we” may also sound disruptive. So if you choose active sentences, you need to keep the number of “we” subjects to a minimum and vary the beginnings of the sentences [ 6 ].

Interestingly, recent studies have reported that the Materials and Methods section is the only section in research papers in which passive voice predominantly overrides the use of the active voice [ 5 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. For example, Martínez shows a significant drop in active voice use in the Methods sections based on the corpus of 1 million words of experimental full text research articles in the biological sciences [ 7 ]. According to the author, the active voice patterned with “we” is used only as a tool to reveal personal responsibility for the procedural decisions in designing and performing experimental work. This means that while all other sections of the research paper use active voice, passive voice is still the most predominant in Materials and Methods sections.

Writing Materials and Methods sections is a meticulous and time consuming task requiring extreme accuracy and clarity. This is why when you complete your draft, you should ask for as much feedback from your colleagues as possible. Numerous readers of this section will help you identify the missing links and improve the technical style of this section.

Rule 3: Be meticulous and accurate in describing the Materials and Methods. Do not change the point of view within one paragraph.

3.2. writing results section.

For many authors, writing the Results section is more intimidating than writing the Materials and Methods section . If people are interested in your paper, they are interested in your results. That is why it is vital to use all your writing skills to objectively present your key findings in an orderly and logical sequence using illustrative materials and text.

Your Results should be organized into different segments or subsections where each one presents the purpose of the experiment, your experimental approach, data including text and visuals (tables, figures, schematics, algorithms, and formulas), and data commentary. For most journals, your data commentary will include a meaningful summary of the data presented in the visuals and an explanation of the most significant findings. This data presentation should not repeat the data in the visuals, but rather highlight the most important points. In the “standard” research paper approach, your Results section should exclude data interpretation, leaving it for the Discussion section. However, interpretations gradually and secretly creep into research papers: “Reducing the data, generalizing from the data, and highlighting scientific cases are all highly interpretive processes. It should be clear by now that we do not let the data speak for themselves in research reports; in summarizing our results, we interpret them for the reader” [ 10 ]. As a result, many journals including the Journal of Experimental Medicine and the Journal of Clinical Investigation use joint Results/Discussion sections, where results are immediately followed by interpretations.

Another important aspect of this section is to create a comprehensive and supported argument or a well-researched case. This means that you should be selective in presenting data and choose only those experimental details that are essential for your reader to understand your findings. You might have conducted an experiment 20 times and collected numerous records, but this does not mean that you should present all those records in your paper. You need to distinguish your results from your data and be able to discard excessive experimental details that could distract and confuse the reader. However, creating a picture or an argument should not be confused with data manipulation or falsification, which is a willful distortion of data and results. If some of your findings contradict your ideas, you have to mention this and find a plausible explanation for the contradiction.

In addition, your text should not include irrelevant and peripheral information, including overview sentences, as in (6).

6. To show our results, we first introduce all components of experimental system and then describe the outcome of infections.

Indeed, wordiness convolutes your sentences and conceals your ideas from readers. One common source of wordiness is unnecessary intensifiers. Adverbial intensifiers such as “clearly,” “essential,” “quite,” “basically,” “rather,” “fairly,” “really,” and “virtually” not only add verbosity to your sentences, but also lower your results’ credibility. They appeal to the reader’s emotions but lower objectivity, as in the common examples in (7):

7a. Table 3 clearly shows that … 7b. It is obvious from figure 4 that …

Another source of wordiness is nominalizations, i.e., nouns derived from verbs and adjectives paired with weak verbs including “be,” “have,” “do,” “make,” “cause,” “provide,” and “get” and constructions such as “there is/are.”

8a. We tested the hypothesis that there is a disruption of membrane asymmetry. 8b. In this paper we provide an argument that stem cells repopulate injured organs.

In the sentences above, the abstract nominalizations “disruption” and “argument” do not contribute to the clarity of the sentences, but rather clutter them with useless vocabulary that distracts from the meaning. To improve your sentences, avoid unnecessary nominalizations and change passive verbs and constructions into active and direct sentences.

9a. We tested the hypothesis that the membrane asymmetry is disrupted. 9b. In this paper we argue that stem cells repopulate injured organs.

Your Results section is the heart of your paper, representing a year or more of your daily research. So lead your reader through your story by writing direct, concise, and clear sentences.

Rule 4: Be clear, concise, and objective in describing your Results.

3.3. now it is time for your introduction.

Now that you are almost half through drafting your research paper, it is time to update your outline. While describing your Methods and Results, many of you diverged from the original outline and re-focused your ideas. So before you move on to create your Introduction, re-read your Methods and Results sections and change your outline to match your research focus. The updated outline will help you review the general picture of your paper, the topic, the main idea, and the purpose, which are all important for writing your introduction.

The best way to structure your introduction is to follow the three-move approach shown in Table 3 .

Adapted from Swales and Feak [ 11 ].

The moves and information from your outline can help to create your Introduction efficiently and without missing steps. These moves are traffic signs that lead the reader through the road of your ideas. Each move plays an important role in your paper and should be presented with deep thought and care. When you establish the territory, you place your research in context and highlight the importance of your research topic. By finding the niche, you outline the scope of your research problem and enter the scientific dialogue. The final move, “occupying the niche,” is where you explain your research in a nutshell and highlight your paper’s significance. The three moves allow your readers to evaluate their interest in your paper and play a significant role in the paper review process, determining your paper reviewers.

Some academic writers assume that the reader “should follow the paper” to find the answers about your methodology and your findings. As a result, many novice writers do not present their experimental approach and the major findings, wrongly believing that the reader will locate the necessary information later while reading the subsequent sections [ 5 ]. However, this “suspense” approach is not appropriate for scientific writing. To interest the reader, scientific authors should be direct and straightforward and present informative one-sentence summaries of the results and the approach.

Another problem is that writers understate the significance of the Introduction. Many new researchers mistakenly think that all their readers understand the importance of the research question and omit this part. However, this assumption is faulty because the purpose of the section is not to evaluate the importance of the research question in general. The goal is to present the importance of your research contribution and your findings. Therefore, you should be explicit and clear in describing the benefit of the paper.

The Introduction should not be long. Indeed, for most journals, this is a very brief section of about 250 to 600 words, but it might be the most difficult section due to its importance.

Rule 5: Interest your reader in the Introduction section by signalling all its elements and stating the novelty of the work.

3.4. discussion of the results.

For many scientists, writing a Discussion section is as scary as starting a paper. Most of the fear comes from the variation in the section. Since every paper has its unique results and findings, the Discussion section differs in its length, shape, and structure. However, some general principles of writing this section still exist. Knowing these rules, or “moves,” can change your attitude about this section and help you create a comprehensive interpretation of your results.

The purpose of the Discussion section is to place your findings in the research context and “to explain the meaning of the findings and why they are important, without appearing arrogant, condescending, or patronizing” [ 11 ]. The structure of the first two moves is almost a mirror reflection of the one in the Introduction. In the Introduction, you zoom in from general to specific and from the background to your research question; in the Discussion section, you zoom out from the summary of your findings to the research context, as shown in Table 4 .

Adapted from Swales and Feak and Hess [ 11 , 12 ].

The biggest challenge for many writers is the opening paragraph of the Discussion section. Following the moves in Table 1 , the best choice is to start with the study’s major findings that provide the answer to the research question in your Introduction. The most common starting phrases are “Our findings demonstrate . . .,” or “In this study, we have shown that . . .,” or “Our results suggest . . .” In some cases, however, reminding the reader about the research question or even providing a brief context and then stating the answer would make more sense. This is important in those cases where the researcher presents a number of findings or where more than one research question was presented. Your summary of the study’s major findings should be followed by your presentation of the importance of these findings. One of the most frequent mistakes of the novice writer is to assume the importance of his findings. Even if the importance is clear to you, it may not be obvious to your reader. Digesting the findings and their importance to your reader is as crucial as stating your research question.

Another useful strategy is to be proactive in the first move by predicting and commenting on the alternative explanations of the results. Addressing potential doubts will save you from painful comments about the wrong interpretation of your results and will present you as a thoughtful and considerate researcher. Moreover, the evaluation of the alternative explanations might help you create a logical step to the next move of the discussion section: the research context.

The goal of the research context move is to show how your findings fit into the general picture of the current research and how you contribute to the existing knowledge on the topic. This is also the place to discuss any discrepancies and unexpected findings that may otherwise distort the general picture of your paper. Moreover, outlining the scope of your research by showing the limitations, weaknesses, and assumptions is essential and adds modesty to your image as a scientist. However, make sure that you do not end your paper with the problems that override your findings. Try to suggest feasible explanations and solutions.

If your submission does not require a separate Conclusion section, then adding another paragraph about the “take-home message” is a must. This should be a general statement reiterating your answer to the research question and adding its scientific implications, practical application, or advice.

Just as in all other sections of your paper, the clear and precise language and concise comprehensive sentences are vital. However, in addition to that, your writing should convey confidence and authority. The easiest way to illustrate your tone is to use the active voice and the first person pronouns. Accompanied by clarity and succinctness, these tools are the best to convince your readers of your point and your ideas.

Rule 6: Present the principles, relationships, and generalizations in a concise and convincing tone.

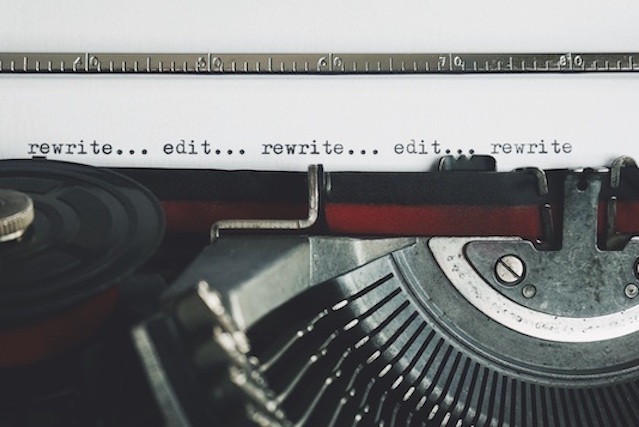

4. choosing the best working revision strategies.

Now that you have created the first draft, your attitude toward your writing should have improved. Moreover, you should feel more confident that you are able to accomplish your project and submit your paper within a reasonable timeframe. You also have worked out your writing schedule and followed it precisely. Do not stop ― you are only at the midpoint from your destination. Just as the best and most precious diamond is no more than an unattractive stone recognized only by trained professionals, your ideas and your results may go unnoticed if they are not polished and brushed. Despite your attempts to present your ideas in a logical and comprehensive way, first drafts are frequently a mess. Use the advice of Paul Silvia: “Your first drafts should sound like they were hastily translated from Icelandic by a non-native speaker” [ 2 ]. The degree of your success will depend on how you are able to revise and edit your paper.

The revision can be done at the macrostructure and the microstructure levels [ 13 ]. The macrostructure revision includes the revision of the organization, content, and flow. The microstructure level includes individual words, sentence structure, grammar, punctuation, and spelling.

The best way to approach the macrostructure revision is through the outline of the ideas in your paper. The last time you updated your outline was before writing the Introduction and the Discussion. Now that you have the beginning and the conclusion, you can take a bird’s-eye view of the whole paper. The outline will allow you to see if the ideas of your paper are coherently structured, if your results are logically built, and if the discussion is linked to the research question in the Introduction. You will be able to see if something is missing in any of the sections or if you need to rearrange your information to make your point.

The next step is to revise each of the sections starting from the beginning. Ideally, you should limit yourself to working on small sections of about five pages at a time [ 14 ]. After these short sections, your eyes get used to your writing and your efficiency in spotting problems decreases. When reading for content and organization, you should control your urge to edit your paper for sentence structure and grammar and focus only on the flow of your ideas and logic of your presentation. Experienced researchers tend to make almost three times the number of changes to meaning than novice writers [ 15 , 16 ]. Revising is a difficult but useful skill, which academic writers obtain with years of practice.

In contrast to the macrostructure revision, which is a linear process and is done usually through a detailed outline and by sections, microstructure revision is a non-linear process. While the goal of the macrostructure revision is to analyze your ideas and their logic, the goal of the microstructure editing is to scrutinize the form of your ideas: your paragraphs, sentences, and words. You do not need and are not recommended to follow the order of the paper to perform this type of revision. You can start from the end or from different sections. You can even revise by reading sentences backward, sentence by sentence and word by word.

One of the microstructure revision strategies frequently used during writing center consultations is to read the paper aloud [ 17 ]. You may read aloud to yourself, to a tape recorder, or to a colleague or friend. When reading and listening to your paper, you are more likely to notice the places where the fluency is disrupted and where you stumble because of a very long and unclear sentence or a wrong connector.

Another revision strategy is to learn your common errors and to do a targeted search for them [ 13 ]. All writers have a set of problems that are specific to them, i.e., their writing idiosyncrasies. Remembering these problems is as important for an academic writer as remembering your friends’ birthdays. Create a list of these idiosyncrasies and run a search for these problems using your word processor. If your problem is demonstrative pronouns without summary words, then search for “this/these/those” in your text and check if you used the word appropriately. If you have a problem with intensifiers, then search for “really” or “very” and delete them from the text. The same targeted search can be done to eliminate wordiness. Searching for “there is/are” or “and” can help you avoid the bulky sentences.

The final strategy is working with a hard copy and a pencil. Print a double space copy with font size 14 and re-read your paper in several steps. Try reading your paper line by line with the rest of the text covered with a piece of paper. When you are forced to see only a small portion of your writing, you are less likely to get distracted and are more likely to notice problems. You will end up spotting more unnecessary words, wrongly worded phrases, or unparallel constructions.

After you apply all these strategies, you are ready to share your writing with your friends, colleagues, and a writing advisor in the writing center. Get as much feedback as you can, especially from non-specialists in your field. Patiently listen to what others say to you ― you are not expected to defend your writing or explain what you wanted to say. You may decide what you want to change and how after you receive the feedback and sort it in your head. Even though some researchers make the revision an endless process and can hardly stop after a 14th draft; having from five to seven drafts of your paper is a norm in the sciences. If you can’t stop revising, then set a deadline for yourself and stick to it. Deadlines always help.

Rule 7: Revise your paper at the macrostructure and the microstructure level using different strategies and techniques. Receive feedback and revise again.

5. it is time to submit.

It is late at night again. You are still in your lab finishing revisions and getting ready to submit your paper. You feel happy ― you have finally finished a year’s worth of work. You will submit your paper tomorrow, and regardless of the outcome, you know that you can do it. If one journal does not take your paper, you will take advantage of the feedback and resubmit again. You will have a publication, and this is the most important achievement.

What is even more important is that you have your scheduled writing time that you are going to keep for your future publications, for reading and taking notes, for writing grants, and for reviewing papers. You are not going to lose stamina this time, and you will become a productive scientist. But for now, let’s celebrate the end of the paper.

- Hayes JR. In: The Science of Writing: Theories, Methods, Individual Differences, and Applications. Levy CM, Ransdell SE, editors. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1996. A new framework for understanding cognition and affect in writing; pp. 1–28. [ Google Scholar ]

- Silvia PJ. How to Write a Lot. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Whitesides GM. Whitesides’ Group: Writing a Paper. Adv Mater. 2004; 16 (15):1375–1377. [ Google Scholar ]

- Soto D, Funes MJ, Guzmán-García A, Warbrick T, Rotshtein T, Humphreys GW. Pleasant music overcomes the loss of awareness in patients with visual neglect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009; 106 (14):6011–6016. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hofmann AH. Scientific Writing and Communication. Papers, Proposals, and Presentations. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zeiger M. Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers. 2nd edition. San Francisco, CA: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Martínez I. Native and non-native writers’ use of first person pronouns in the different sections of biology research articles in English. Journal of Second Language Writing. 2005; 14 (3):174–190. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodman L. The Active Voice In Scientific Articles: Frequency And Discourse Functions. Journal Of Technical Writing And Communication. 1994; 24 (3):309–331. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tarone LE, Dwyer S, Gillette S, Icke V. On the use of the passive in two astrophysics journal papers with extensions to other languages and other fields. English for Specific Purposes. 1998; 17 :113–132. [ Google Scholar ]

- Penrose AM, Katz SB. Writing in the sciences: Exploring conventions of scientific discourse. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Swales JM, Feak CB. Academic Writing for Graduate Students. 2nd edition. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hess DR. How to Write an Effective Discussion. Respiratory Care. 2004; 29 (10):1238–1241. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Belcher WL. Writing Your Journal Article in 12 Weeks: a guide to academic publishing success. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Single PB. Demystifying Dissertation Writing: A Streamlined Process of Choice of Topic to Final Text. Virginia: Stylus Publishing LLC; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Faigley L, Witte SP. Analyzing revision. Composition and Communication. 1981; 32 :400–414. [ Google Scholar ]

- Flower LS, Hayes JR, Carey L, Schriver KS, Stratman J. Detection, diagnosis, and the strategies of revision. College Composition and Communication. 1986; 37 (1):16–55. [ Google Scholar ]

- Young BR. In: A Tutor’s Guide: Helping Writers One to One. Rafoth B, editor. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook Publishers; 2005. Can You Proofread This? pp. 140–158. [ Google Scholar ]

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

How to Write a Research Paper | A Beginner's Guide

A research paper is a piece of academic writing that provides analysis, interpretation, and argument based on in-depth independent research.

Research papers are similar to academic essays , but they are usually longer and more detailed assignments, designed to assess not only your writing skills but also your skills in scholarly research. Writing a research paper requires you to demonstrate a strong knowledge of your topic, engage with a variety of sources, and make an original contribution to the debate.

This step-by-step guide takes you through the entire writing process, from understanding your assignment to proofreading your final draft.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Understand the assignment, choose a research paper topic, conduct preliminary research, develop a thesis statement, create a research paper outline, write a first draft of the research paper, write the introduction, write a compelling body of text, write the conclusion, the second draft, the revision process, research paper checklist, free lecture slides.

Completing a research paper successfully means accomplishing the specific tasks set out for you. Before you start, make sure you thoroughly understanding the assignment task sheet:

- Read it carefully, looking for anything confusing you might need to clarify with your professor.

- Identify the assignment goal, deadline, length specifications, formatting, and submission method.

- Make a bulleted list of the key points, then go back and cross completed items off as you’re writing.

Carefully consider your timeframe and word limit: be realistic, and plan enough time to research, write, and edit.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

There are many ways to generate an idea for a research paper, from brainstorming with pen and paper to talking it through with a fellow student or professor.

You can try free writing, which involves taking a broad topic and writing continuously for two or three minutes to identify absolutely anything relevant that could be interesting.

You can also gain inspiration from other research. The discussion or recommendations sections of research papers often include ideas for other specific topics that require further examination.

Once you have a broad subject area, narrow it down to choose a topic that interests you, m eets the criteria of your assignment, and i s possible to research. Aim for ideas that are both original and specific:

- A paper following the chronology of World War II would not be original or specific enough.

- A paper on the experience of Danish citizens living close to the German border during World War II would be specific and could be original enough.

Note any discussions that seem important to the topic, and try to find an issue that you can focus your paper around. Use a variety of sources , including journals, books, and reliable websites, to ensure you do not miss anything glaring.

Do not only verify the ideas you have in mind, but look for sources that contradict your point of view.

- Is there anything people seem to overlook in the sources you research?

- Are there any heated debates you can address?

- Do you have a unique take on your topic?

- Have there been some recent developments that build on the extant research?

In this stage, you might find it helpful to formulate some research questions to help guide you. To write research questions, try to finish the following sentence: “I want to know how/what/why…”

A thesis statement is a statement of your central argument — it establishes the purpose and position of your paper. If you started with a research question, the thesis statement should answer it. It should also show what evidence and reasoning you’ll use to support that answer.

The thesis statement should be concise, contentious, and coherent. That means it should briefly summarize your argument in a sentence or two, make a claim that requires further evidence or analysis, and make a coherent point that relates to every part of the paper.

You will probably revise and refine the thesis statement as you do more research, but it can serve as a guide throughout the writing process. Every paragraph should aim to support and develop this central claim.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

A research paper outline is essentially a list of the key topics, arguments, and evidence you want to include, divided into sections with headings so that you know roughly what the paper will look like before you start writing.

A structure outline can help make the writing process much more efficient, so it’s worth dedicating some time to create one.

Your first draft won’t be perfect — you can polish later on. Your priorities at this stage are as follows:

- Maintaining forward momentum — write now, perfect later.

- Paying attention to clear organization and logical ordering of paragraphs and sentences, which will help when you come to the second draft.

- Expressing your ideas as clearly as possible, so you know what you were trying to say when you come back to the text.

You do not need to start by writing the introduction. Begin where it feels most natural for you — some prefer to finish the most difficult sections first, while others choose to start with the easiest part. If you created an outline, use it as a map while you work.

Do not delete large sections of text. If you begin to dislike something you have written or find it doesn’t quite fit, move it to a different document, but don’t lose it completely — you never know if it might come in useful later.

Paragraph structure

Paragraphs are the basic building blocks of research papers. Each one should focus on a single claim or idea that helps to establish the overall argument or purpose of the paper.

Example paragraph

George Orwell’s 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language” has had an enduring impact on thought about the relationship between politics and language. This impact is particularly obvious in light of the various critical review articles that have recently referenced the essay. For example, consider Mark Falcoff’s 2009 article in The National Review Online, “The Perversion of Language; or, Orwell Revisited,” in which he analyzes several common words (“activist,” “civil-rights leader,” “diversity,” and more). Falcoff’s close analysis of the ambiguity built into political language intentionally mirrors Orwell’s own point-by-point analysis of the political language of his day. Even 63 years after its publication, Orwell’s essay is emulated by contemporary thinkers.

Citing sources

It’s also important to keep track of citations at this stage to avoid accidental plagiarism . Each time you use a source, make sure to take note of where the information came from.

You can use our free citation generators to automatically create citations and save your reference list as you go.

APA Citation Generator MLA Citation Generator

The research paper introduction should address three questions: What, why, and how? After finishing the introduction, the reader should know what the paper is about, why it is worth reading, and how you’ll build your arguments.

What? Be specific about the topic of the paper, introduce the background, and define key terms or concepts.

Why? This is the most important, but also the most difficult, part of the introduction. Try to provide brief answers to the following questions: What new material or insight are you offering? What important issues does your essay help define or answer?

How? To let the reader know what to expect from the rest of the paper, the introduction should include a “map” of what will be discussed, briefly presenting the key elements of the paper in chronological order.

The major struggle faced by most writers is how to organize the information presented in the paper, which is one reason an outline is so useful. However, remember that the outline is only a guide and, when writing, you can be flexible with the order in which the information and arguments are presented.

One way to stay on track is to use your thesis statement and topic sentences . Check:

- topic sentences against the thesis statement;

- topic sentences against each other, for similarities and logical ordering;

- and each sentence against the topic sentence of that paragraph.

Be aware of paragraphs that seem to cover the same things. If two paragraphs discuss something similar, they must approach that topic in different ways. Aim to create smooth transitions between sentences, paragraphs, and sections.

The research paper conclusion is designed to help your reader out of the paper’s argument, giving them a sense of finality.

Trace the course of the paper, emphasizing how it all comes together to prove your thesis statement. Give the paper a sense of finality by making sure the reader understands how you’ve settled the issues raised in the introduction.

You might also discuss the more general consequences of the argument, outline what the paper offers to future students of the topic, and suggest any questions the paper’s argument raises but cannot or does not try to answer.

You should not :

- Offer new arguments or essential information

- Take up any more space than necessary

- Begin with stock phrases that signal you are ending the paper (e.g. “In conclusion”)

There are four main considerations when it comes to the second draft.

- Check how your vision of the paper lines up with the first draft and, more importantly, that your paper still answers the assignment.

- Identify any assumptions that might require (more substantial) justification, keeping your reader’s perspective foremost in mind. Remove these points if you cannot substantiate them further.

- Be open to rearranging your ideas. Check whether any sections feel out of place and whether your ideas could be better organized.

- If you find that old ideas do not fit as well as you anticipated, you should cut them out or condense them. You might also find that new and well-suited ideas occurred to you during the writing of the first draft — now is the time to make them part of the paper.