Transtext(e)s Transcultures 跨文本跨文化

Journal of Global Cultural Studies

Accueil Numéros 4 Why do Cultures Change? The Chall...

Why do Cultures Change? The Challenges of Globalization

This essay explores cultural change in the context of the economic globalization currently underway. It aims at analysing the role that theoretical inventiveness and ethical value play in fashioning broader cultural representation and responsibility, and shall explore issues of cultural disunity and conflict, while assessing the influence that leading intellectuals may have in promoting a finer perception of value worldwide. The role of higher education as an asset in the defence of democracy and individual self-development shall be discussed with a view to evaluating its potential for an altered course of globalization.

Texte intégral

- 1 Ralph Waldo Emerson “Napoleon; or, the man of the world” in Joel Porte, Essays and Lectures , New Y (...)

2 Emerson, p. 731.

1 We are always in need of definitions whenever we want to explore why cultures change. We are pressed to come up with answers as to what culture might be and how the idea of culture might fit into a nutshell. The general applicability of the answer we struggle to devise invites theoretical formulas and abstraction from specific historical developments. It also, as a result, cautions us to choose fields from which to cull situations and conflicts that may help deliver the concepts we want to grasp, and invites to understand the theory of culture as shaped by how events unfold, and how society moves along. In particular, one may have in mind what the American philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote about Napoleon (our favourite dictator, to us French people) in a book he devoted to figures of historical importance ( Representative Men ): “Such a man was wanted, and such a man was born” 1 . This strikes a negative note, as does a quote from Napoleon himself that Emerson has unearthed from the vast body of memoirs the Napoleon era has handed down to us. Emerson is reported to have once declared: “My hand of iron […] was not at the extremity of my arm; it was immediately connected with my head” 2 . The remark and the quote hold a tentative definition of culture. Culture begins when sheer force is mitigated by intellect, intellect itself being shaped by a response to facts, and, we hope, as Emerson hopes, abstracted from fact by ethical imperative. On top of this, we feel Emerson’s attempt at rationality is run through by doubt: what if one might never discriminate between intellect and action? What if one might never grasp how ethics can disengage us from the cogs of history and were incapable of controlling an ongoing process that leads to disaster and apocalypse? Whenever one tries to define culture, culture breaks down into its many components: it splinters into action and responsibility, and we feel there might never be a connection between them. There lies Emerson’s historical pessimism, which it is hard to tone down.

- 3 Hubert Damisch, “A Crisis of Values, or Crisis Value ?”, in Daniel S. Hamilton (ed.), Which Values (...)

2 In recent years, a debate has been brought to the foreground, for reasons that have to do with our increasingly globalized world. Are there any values left? If such a thing as culture exists, then, there might be precise contents of an ethical sort that we want to pin down. Might not this sense of emptiness be the result of a crisis of value, as if the very idea of value had been swept away? This is what the French cultural critic Hubert Damisch thinks has happened, in a recent contribution to a volume aptly titled Which Values for our Time , published by the Gulbenkian Foundation of Lisbon. Damisch rounds up his interrogation as follows: “Crisis of values, or crisis value?” 3 The suggestion is of course that value is no longer visible on the horizon of our history to be, that the trend should be resisted, and that intellectual resistance is what we need. It is by no means new to be aware, among philosophers and cultural critics alike, that values are hard to come by. In Plato’s Republic , book seven, humankind is looking at the walls of a cave, noting the shadows dancing there, and being taught that our poor sight precludes the perception of good and evil, and the difference between them. Now that the walls of the cave have turned into television screens, one image is chased away by the next one, while our sense of global responsibility dissolves into thin air even though all the fields of human action hold perspectives of responsibility within them. Culture, like values, is a plenum and a void, a constant expectation and in the end something impossible when one looks at results and facts.

- 4 Peter Fenves, (ed.), Raising the Tone of Philosophy ; Late Essays by Immanuel Kant, Transformative (...)

3 We should keep in mind Jacques Derrida’s anthropology of culture, and the degree to which it identifies conflict as the prime-mover within our cultural narratives. In a major contribution at a Cerisy conference in Normandy in 1980, titled “On a Newly Arisen Superior Tone in Philosophy” 4 , Jacques Derrida opposes two sets of attitudes: seeking rationality, and seeking mystery. Derrida views culture as the competition between the Aüfklarer and the mystics, and suggests there are possibilities that the two trends in cultural discourse might eventually reach some kind of truce achieved as a result of an interaction between them. No doubt he was trying to hold historical pessimism at a distance by suggesting gain might be reached in the historical development of cultures if rationality were capable of reading through the language of mysticism, and curb the influence of those he chose to call the mystagogues, in whom he saw a danger for democracy and human dignity. Cultures change, and when they do, they are pulled in opposite directions if we abide by Derrida’s critical thinking. They change to eliminate reason, even, as Derrida puts it, to emasculate it, and we must, as a result, apply pressure to preserve amity, and to uphold the values of democracy. To be sure, Derrida’s onslaught upon mystery is no onslaught upon religious values: there are many other targets we might think of in the current context of globalized liberal economies and environmental overuse, such as religious fundamentalism, terrorism, and the emergence of a global self-appointed elite, although Derrida’s inquiry was started some thirty years ago, and he never gets that precise about what should be indicted.

Disaster and Apocalypse

- 5 See in particular Making Globalization Work , New York, Norton, 2007, chapter 7, “The Multinational (...)

- 6 Richard Rorty, “Globalization, the politics of identity and Social Hope” in Philosophy and Social (...)

4 Our globalizing societies offer alternatives to an ideal world. In particular, market mechanisms and the rise of global capital have impoverished some non-European nations, while Europe has, in recent years, worked to thin the immigration flux while downsizing out of their jobs the low-skilled workers of a once predominantly industrial economy that has now turned to services. As a result, local communities have been struck, either in Europe or the United States, by being impoverished within the more glitzy context of affluence. In China as elsewhere, industrial activity has surged, while working conditions have never been worse among the former peasants driven to urban areas. Globalization may well pass for an agenda of disaster and social apocalypse, as Joseph Stiglitz has demonstrated 5 . Welfare and human rights have hardly benefited from the promise economic liberalism keeps harping on, and human development has been restricted to the rising middle-classes of China, or India, if we look at the most significant examples. Richard Rorty, meditating on social hope, has brought home the idea that globalization has been a blow to democracy. He wrote the following in an essay published in 1993: “We now have a global overclass which makes all the major economic decisions, and makes them entirely independently from the legislatures, and a fortiori of the will of the voters, of any given country” 6 . Rorty’s remark comes as an apposite reminder that there is no such thing as a world government, a fact that we all tend to overlook. The ideology of economic growth heralds human development, but delivers little in terms of the strengthening of local communities, both in rising nations as well as in Western ones. Might not this ideology form the most recent embodiment of some pseudo-thinking the mystagogues parade as rationality for us to kneel to?

5 Communities, we hear, have gone global, which means they are now glocal. The portmanteau word means more than it seems to say. On the one hand, the buzzword suggests that local communities may be strengthened by globalization; on the other, it suggests that local communities are shaped, in ways that cannot all be positive, by the advance of global liberalism. However, one of the unsought effects of glocalization may well be that cultural interference with distant or unknown communities might emerge from the pressure of global liberalism, by dissolving national, or even nationalist perspectives, and favouring international contacts. Let us be cautious in this: international interaction, in the context of globalizing economic exchange, may well be no other than buying and selling, and one more version of materialism without national values being cross-fertilized.

- 7 Jürgen Habermas, The New Conservatism: Cultural Criticism and the Historian’s debate , Cambridge, M (...)

6 Globalization cannot control the rise of a new conservatism, in spite of the surge in optimism that comes with it in some areas, if we look at the poor condition of welfare systems across developed countries and elsewhere. As Habermas has pointed out, “modernity sees itself as dependent exclusively upon itself” 7 , and utopian ideals are increasingly wiped out of the Zeitgeist. Globalization is in dire need of strengthening, not exhausting, utopian energies. If it proves incapable of effecting this, renewing utopian energies, the road down globalization may well be what one supposes it to be from recent evidence: a hurdle-race, with one winner, a few good athletes, and vast crowds of anonymous losers. Jacques Derrida has pointed out that we need peace in culture, and that peace can be achieved when the mystagogues accept to interact with rationality. Rationality however, to him, is not an empty bottle, or an instrument by which societies may solve practical questions. Rationality involves moral choice, and one may well suggest that the Habermas notion that utopian ideals have to be upheld is the best way to reorder, and refashion global liberalism. No doubt, the culture wars must go on, to stay the current backlash and its related traumas, terrorism East and West, the political violence within national borders and without, the religious fundamentalism which has found in globalization its ecotope, in Israel, in the Arab world, in the United States, and elsewhere, while environmental disasters from North to South take their toll upon communities. Cultures, as a result of globalization, change, for reasons that have to do with the innate systemic risks that globalization runs through them, risks which are supra-human, but which, for that very reason, have to be identified, deconstructed, and eliminated, although we do know that this process cannot be the work of one sole generation. Indifference as well as naïveté ought to be avoided. If, as Habermas thinks they are, utopian values are used-up, because they are targeted, then, they must be invigorated.

- 8 Emery Roe and Michel J.G. Van Eeten, “Three – Not Two – Major Environmental Counternarratives to G (...)

7 No doubt any such invigoration, if we want it to have pragmatic efficiency, we need specific measures, and precautions. Intellectual clarity can help. And meditation upon what is and what is not scientific can be an asset. It is true odium has been cast on the precautionary principle by some scholars of environmental studies. In a fairly recent issue (2004) of the M.I.T. Press quarterly Global Environmental Politics, scholars Emery Roe and Michel Van Eeten have condemned the precautionary principle in matters of environmental policy on the grounds that scientific evidence is not sufficient, calling for empirical knowledge, supposed to be an index to what is and what is not scientific 8 . Is it that globalization has reshaped the image of science in academia, making us wistful once again, and inviting us to find peace of mind in a belated version of science which is reminiscent of the nineteenth century, when science was largely considered to rely on empirical observation, whatever this might mean? Empiricism and dogmatic thinking are birds of a feather flocking together. More open intellectual attitudes are necessary to face the risks of globalization upon our environment. Doubt, in particular, may be protective, in this respect. Without it, scientific thinking can be stultified. Science cannot be independent of general interest and social respect, and requires critical detachment to shelter us from the systemic dangers inherent in its objects of inquiry and the applicability of its fundamental findings. In scientific knowledge as well, the culture wars loom large, though they tend to be overlooked. These wars may lead both ways: to cultural changes that will crush social hope, and to cultural changes that will uplift a sense of community and cooperation.

The Secularization of Value

9 Jean-Pierre Dupuy, Petite Métaphysique des Tsunamis , Paris, Seuil, 2005, p. 85.

8 The values of science, therefore, should be secularized, and scientists should avoid generating systems which hold dangers in them that might express their potential for destruction. The French philosopher and Stanford scholar Jean-Pierre Dupuy has pointed out that the atomic bombing of Japan was the result of systemic danger, in an amazing remark: “Why was the bomb ever used? Because it existed, quite simply” 9 . The implication of what he says is that science too, and what was at one point presented as an advance of the civilized mind, may lead to pragmatic consequences that reshape thinking and emasculate it, if we want to harp on the Derrida proposition that the mystagogues are able to emasculate rationality (let us pardon Derrida’s male chauvinism if we can). Human thinking involves systemic dangers, and one therefore has to rethink thinking in different terms, which has been the task of modern philosophy. Perhaps we might suggest at this point that cultural change involves the thinking of rationality in secularized terms. This means that technology may well lead us astray, tethered as it is to scientific knowledge which we tend to view as total, whereas any inquiry into the results of science tends to demonstrate that science is provisional, and that its propositions will sooner or later be refined, or redefined, and that intellectual inquiry, whatever its field, rarely comes to conclusions that will never be reworded, or revised. Knowledge is an ongoing process, and if we keep this in mind, we secularize science, instead of projecting it onto the higher plane of superior frozen truths. Science, like any other human adventure, unfolds through time, and taking this into consideration helps science respond to social needs.

9 Political scientists are struggling for secular views, as John Rawls has amply demonstrated. Behind his eulogy of democracy as a condition and an effect of economic and political liberalism, one finds an attempt to define the nature of rationality as the mainspring of social hope. It is striking, when reading John Rawls, to realize the extent to which rationality is assessed in conjunction with its effects upon social organization, which yields workable political conceptions of justice. John Rawls, in his second major opus, Political Liberalism , defines political rationality as outcome-centered, and this leads to a list of primary goods, which reads as follows:

basic rights and liberties […];

freedom of movement and free choice of occupation against a background of diverse opportunities;

powers and prerogatives of offices and positions of responsibility in the political and economic institutions of the basic structure;

income and wealth;

- 10 John Rawls, Political Liberalism , New York, Columbia University Press, 1993, p. 181. Joseph Stigli (...)

and finally, the social bases of self-respect. 10

- 11 Slavoj Zizek, “Le Tibet pris dans le rêve de l’autre”, Le Monde Diplomatique , n° 650, mai 2008, p. (...)

10 Rawls’ agenda relies on the traditions of the common-sense philosophy of the English-speaking world and the theoretical culture of pragmatism, which he found ready for use in his New-England intellectual environment. Nowhere do we find perspectives that would be disconnected from and independent from day-to-day preoccupations. Rawls wants to harness human development to democracy, to wring democracy out of economic growth, while there is an increasing belief, in this century, that our globalized economies hold a promise of democracy as an expectation which will always be contradicted by fact. Just recently, in a major contribution to the debate, the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek has pointed out that China allies a vicious use of the Asian bludgeon in Tibet with the logics of the European stock-market, and that this betrays the belief that democracy is an obstacle to economic growth. As a result of this, Zizek’s assumption is that our global culture might be brought to understand that democracy is no longer needed to back human development, which might lead global cultural change in the wrong direction 11 . Democracy has to be maintained as a horizon of belief, and as the sole teleology worthy of respect. Rawls helps us understand that teleology should be one version of practicality, though we tend to think that any political teleology is an empty promise. His contribution to political philosophy views rationality not just as a belated version of theology, but as a tool that may help deliver collective results, following in the footsteps of American intellectual traditions which assess value in terms of their pragmatic consequences rather than in terms of otherworldly conceptual exploration.

- 12 Samuel Huntington, “Foreword” in Lawrence E. Harrison & Samuel Huntington (eds.), Culture Matters: (...)

11 What if, beyond this sound conception of political values, and the organic laws that go to frame them, human culture was unresponsive, thus precluding cultural change, and sustainable development? It is this situation that Samuel Huntington examines, leaving little room for hope, suggesting that cultures cannot change, or will change slowly or with difficulty, on the grounds that society will not change and that there is no connection between assumptions, beliefs, and the economic and political opportunities that the modern liberal state offers if we are willing to grasp them. Huntington’s dream is to get rid of cultural obstacles to economic development, while it is yet unclear whether there is any strong belief in the virtues of democracy in what he has to say. Huntington’s answer does not intend to demonstrate that it is democracy which has to be left out of his global picture. In his case, if progress is not fast enough, it is because those cultures which resist progress as seen from Massachusetts are obstacles which one must remove, but Huntington is no clear analyst of how culture and democracy might hinge. “[…] We define culture, Huntington writes, in purely subjective terms as the values, attitudes, beliefs, orientations, and underlying assumptions prevalent among people in a society” 12 . His vision of culture has left one notion unmentioned: what about solidarity, the cornerstone of Richard Rorty’s vision of social hope? It may well be that this is one value that the modern liberal state has eroded, and that solidarity is a basic asset to those communities forming the lesser developed countries of Africa, Latin America and parts of the Asian world, where welfare is weak, and institutionalized education poorly developed, where, for political reasons, states are not ready to reach out to populations and areas left to their own resources and inventiveness in terms of welfare. Huntington’s discourse, as a result, is a perfect illustration of the New Conservatism that Habermas has targeted. Modernity, in Huntington’s world-view, is seen as totally dependent on itself. Beliefs, in particular, are taken to task, in Huntington’s definition of culture. What if beliefs were an adequate instrument of the progress Huntington has in mind, one notion which is empty enough, and which Huntington parades to conceal his conservative views? Inherited ideas and attitudes are more of a survival-kit than an obstacle to social cohesiveness. One hardly knows, when reading Huntington, whether progress, the norm of his perspective, is one serious academic case of mystagogic thinking, or whether it may have practical applicability. It is arguable that progress, with Samuel Huntington, is an abstract notion.

13 Lucian W. Pye, “’Asian Values’: from dynamos to dominoes?”, Culture Matters , p. 249 .

- 14 On this consider Françoise Lemoine, L’Economie de la Chine , Paris, La Découverte, 2006, esp. pp. 6 (...)

12 Asian culture turns out to be an epistemological obstacle to many political scientists. Once considered incapable of generating economic growth, Asian values are seen as an asset in the ongoing economic race, with growth rates that belittle Europe and the United States alike in some quarters of the Asian world. Can one blame economic stagnation on them yesterday, and now say that some basic values of Asian cultures are the leverage of change helping those so-called miracle economies make some headway? There may well be an emphasis on hard work in Chinese culture, but one cannot see how this is specifically Chinese, or American, or British. Lucian Pye, one prominent M.I.T. scholar in Chinese studies, has suggested that Taoism and the belief in good fortune, supposed to be specific to Chinese culture (although I am aware this might be challenged), has produced outgoing dynamic character in the Chinese people, which makes them ready to grasp any opportunity likely to turn to their advantage. Pye’s view of Chinese culture may easily be taken to task, as he implies that Chinese culture leaves no room for introspection. This is most probably a typical misconception such as New-England protestant culture wants to bring home. Lucian Pye, in particular, writes the following when considering the reasons for China’s rapid expansion: “This stress of the role of fortune makes for an outward-looking and highly reality-oriented approach to life, not an introspective one” 13 . This is, we guess, one academic version of prejudice insisting that the Chinese have no soul, and no interest for an inner life. Economists, on the other hand, go for a more mundane vision of China’s development, insisting on the capacity to attract foreign investors 14 . This is also quite true of many other rising Asian economies besides China.

13 However, these observations lead us to want to extend our definition of culture. Culture is not just simply a cluster of beliefs and attitudes outside the realm of economic and political development. Culture is probably much more than beliefs and attitudes. It encompasses what we might call material culture, in the sense that attitudes matter in economic development, which is no big news, if we refer to Max Weber’s understanding of the ethic of capitalism, shaped as it is by the sense of insecurity that goes with the necessity to devise for oneself advancement in this world, the better to advance in the next one, or the higher or more sophisticated one in the rich oriental spiritual heritage. No wonder then that Derrida should suggest that between rationality and mystery, there is one connection to be established. And, in Derrida’s view of how rationality and mystery interact, one finds an abiding agreement occurring, and this is of course desirable to establish peace in what he calls culture, which to him is more of a socially encompassing substance than a mere individual determinant of behaviour.

15 Pye, “’Asian Values’: from dynamos to dominoes?”, p. 250.

16 Pye, p. 250.

14 Lucian Pye is interesting as an analyst of Chinese social development, not for what certainties he may have in store for us, but for the scepticism which his propositions will cause in most areas of the academic world, and across disciplines. Examining the reasons for China’s economic advance, he writes that “[...] the driving force in Chinese capitalism has always been to find out who needs what and to satisfy that market need” 15 . One might meditate for quite a while to determine whether markets are out there for anyone to grab, or whether one should shape markets, create needs, and respond to one’s ambition to grow by being inventive. Nevertheless, Lucian Pye views Chinese economy as a simplistic answer to world needs, and the capacity to adapt to them, whereas the West is seen as technology-driven, and culturally more sophisticated: “Western firms seek to improve their products, strengthen their organizational structures, and work hard to achieve name recognition” 16 . We wonder whether Chinese firms have not always tried to do precisely this, which can only be generalized with a vast highly educated workforce, which China is trying to obtain by adequate investment in higher education. This path is promising, from what we can judge when considering our Chinese students in our higher learning European institutions.

Cultural Change and Universities

17 Habermas, The New Conservatism , p. 104.

18 Jacques Derrida, L’Université sans condition , Paris, Galilée, 2001, p. 16.

19 See “The Idea of the University”, The New Conservatism , pp. 100-127.

15 If therefore, cultures change, not just private cultures, but also public ones, as we increasingly suspect cultures to be collective assets, university education has a major role to play in this process. We, as academics, either experienced or aspiring ones, must address the issue of what a university education ought to be like. So far in this discussion, we have acknowledged that academics should avoid voicing social prejudice, and this has not always been accomplished, to say the least. Jacques Derrida has meditated extensively on this, with a view to promoting the role education might play in defending the values of democracy, no doubt because Derrida’s understanding of the effects of academic training is combined with the idea of a political education for youth. This may be easily understood when one looks at the moral paralysis of the German university system and its many graduates embracing Nazism and providing the Nazi regime with its most destructive propagandists and functionaries. However, Habermas is clear on this point. German universities cannot be blamed for what befell. Habermas, in particular, points out that the number of students was halved during Nazism in Germany, dropping from 121 000 in 1933 to below 60 000 right before the Second World War 17 . One reason why this happened, although Derrida is not explicit on this point, is that universities tend to over-specialize knowledge. This has caused the decline of humanistic study. Habermas offers similar views, though they are cast in a more sociological mould. To Derrida, higher education should be critical of whatever rationality wants to assess. He calls this “the university without conditions”, which to him involves an ambitious agenda thus defined: “the primal right to say anything, be it in the name of fiction and of knowledge as experiment, and the right to speak publicly, and to publish this” 18 . Habermas offers a more accurate version of what ought to be done, and has been insufficiently accomplished so far: integrating humanistic study and technical expertise to curb the specialization of knowledge 19 .

20 Derrida, L’Université sans condition , p. 69.

16 This may sound vague enough, and we wonder where it might lead, because one doubts whether knowledge, in various disciplines, might efficiently refrain from becoming specialized. This is why Derrida comes up with more practical propositions as to the contents and orientations of higher education in the book he published in 2001, L’Université sans condition . There are seven such propositions, all having to do with what one might call the architecture of knowledge, all answering the need to redefine humanistic study, which should come alongside more specialized training, either in established scholarly disciplines, or the training of students towards professions outside the academic world. The new humanities should, according to Derrida, deal with what he calls “the history of man”, which calls us to devote more attention than has so far been devoted to human rights, be they for men or women. To him, these rights are “legal performatives” 20 , which sounds otherworldly owing to the weight of abstraction in the phrase. However, this might basically mean that these rights are to be upheld because they can be applied to the various fields of human activity. Furthermore we must bear in mind that these so-called “legal performatives” are performatives because they hold within them an applicability that may be constantly expanded, in practical terms, to various areas of cultural practice, among which of course science and business, two areas of higher education that are growing to meet the social needs of human development.

17 The idea of democracy comes second in Derrida’s architecture of the new humanities. It comes second for reasons of clarity in the presentation of the programme he has in mind. Yet the idea of democracy is not a second-thought, because it runs, let us be reminded, through all his oeuvre as a philosopher. Let us note that democracy, as far as what Derrida has to say about it, is not tethered to nationhood. Nationhood is dangerous, and one may easily understand this in the light of European history, and also of Asia. From this, we can easily infer that cultural change in the future should not rely on national traditions, and that, in this respect, globalization offers opportunities for positive cross-fertilization. Derrida’s meditation on this hinges on the concept of sovereignty. While sovereignty is a desirable goal for each and every one of us; the idea is viewed as misleading, as it has often been a concept without practical consequences, while we may still hope that sovereignty will remain a horizon of belief for individuals, and a value that will guide collective decisions. Yet, if Derrida invites us to abide by this concept (sovereignty), he also believes that any collective formalization of the idea of sovereignty should avoid reliance on the nation-state, which may too easily lead to a betrayal of individual dignity.

21 Derrida, p. 72.

18 Derrida then focuses on the necessity to recuperate the authority of teaching, and of literature, whose proposals cannot be easily understood. One suspects, when reading Derrida’s proposals, that teaching as well as literature have to do with amity, a concept that emerges from Derrida’s body of works. This is not a norm, neither is it prescriptive, nor can it be strictly defined as a doctrine or a set of mandatory rules. We gather this is to be understood as an opening to otherness on the part of the teacher, and a eulogy of respect for the other person, which involves inventiveness and the by-passing of any sort of regulation that defines the other person in some way or other that might lead to a position of authority of a colonial or exploitative nature. It certainly is an attitude of respect, which elbows aside the very notion of authority, “routs it”, as Derrida says 21 . Universities, therefore, should constitute an idea that transcends any specialized discourse on the technicalities of education; it consists in letting the other reach out for his or her potential towards self-development. The institutional strength of higher education springs, in Derrida’s view of it, from the interaction of the person who teaches and the one being taught, to live to the full his or her aspirations. Derrida’s ideal is so elevated that it transcends any definition one might come up with. It certainly is a call to confront the normative nature of higher education in order to recuperate a lost sense of human warmth that has been eliminated by the technocratic complexities of institutions seeking intellectual identity in the measurement of student skills and their willingness to comply to them. One also cannot rule out that a backlash has been underway in higher education itself owing to the rising number of first-generation graduates from the less educated groups of our national cultures. This has been more of an opportunity for universities to fulfil their cultural mission from the sixties onwards than a serious obstacle to the growth of higher education, and one can argue that Derrida was balking away from the pessimistic discourse one hears in most academic circles today – ill-grounded as it is on the relative accessibility to higher education.

- 22 On this, consider Daniel Parrochia, La Forme des crises : logique et épistémologie , Seyssel, Champ (...)

19 The challenges that higher education has to face, in the context of an ever-increasing cross-fertilization of cultures, points to one underlying question that surfaces from an examination of current economic and social trends. Is what we call culture tethered to social and economic factors? The question is by no means new, and was handed down to us by the industrial revolutions of the nineteenth century, and by Marxist theory. We now tend to believe that culture is one mode of collective representation that one may disengage from submission to social and economic facts. On this point, the French sociologist Emile Durkheim referred to real structures , that he saw as disconnected from institutions or working facts . 22 There is still much thought to be devoted to whether the degree of autonomy of culture as collective representation involves radical or relative autonomy from economic factors. We are also hard pressed to determine whether, in this framework of analytical thinking, autonomy is or is not hampered by the necessities of those real structures and the institutions that shape them, and even perhaps discreetly justify them. Hence, Stiglitz’s view that one must respond to a democratic deficit, and Derrida’s view that one must face the serious issue of a democratic deficit in higher education. The question is not benign, and it calls forth an autonomy of the mind to bend social realities and economic factors to purposes that do not derive from them.

1 Ralph Waldo Emerson “Napoleon; or, the man of the world” in Joel Porte, Essays and Lectures , New York, The Library of America, 1983, p. 731.

3 Hubert Damisch, “A Crisis of Values, or Crisis Value ?”, in Daniel S. Hamilton (ed.), Which Values for our Time, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Center for Transatlantic Relations, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007, p. 57.

4 Peter Fenves, (ed.), Raising the Tone of Philosophy ; Late Essays by Immanuel Kant, Transformative Critique by Jacques Derrida , Baltimore and London, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993, pp. 117-171; French edition : « D’un ton apocalyptique adopté naguère en philosophie » in Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe et Jean-Luc Nancy (ed.), Les Fins de l’Homme: à partir du travail de Jacques Derrida , Paris, Galilée, 1981, pp. 445-479.

5 See in particular Making Globalization Work , New York, Norton, 2007, chapter 7, “The Multinational Corporation”.

6 Richard Rorty, “Globalization, the politics of identity and Social Hope” in Philosophy and Social Hope , London, Penguin, 1999, p. 233.

7 Jürgen Habermas, The New Conservatism: Cultural Criticism and the Historian’s debate , Cambridge, Mass., The M.I.T. Press, (1989) 1997, p. 48.

8 Emery Roe and Michel J.G. Van Eeten, “Three – Not Two – Major Environmental Counternarratives to Globalization”, Global Environmental Politics , 4:4, November 2004; see in particular pp. 36-39.

10 John Rawls, Political Liberalism , New York, Columbia University Press, 1993, p. 181. Joseph Stiglitz follows suits with a set of more technical criteria in Making Globalization Work; s ee the section“Responding to the Democratic Deficit”, pp. 280-285.

11 Slavoj Zizek, “Le Tibet pris dans le rêve de l’autre”, Le Monde Diplomatique , n° 650, mai 2008, p. 32.

12 Samuel Huntington, “Foreword” in Lawrence E. Harrison & Samuel Huntington (eds.), Culture Matters: How Values Shape Human Progress , New York, Basic Books, 2000, XV.

14 On this consider Françoise Lemoine, L’Economie de la Chine , Paris, La Découverte, 2006, esp. pp. 67-68.

22 On this, consider Daniel Parrochia, La Forme des crises : logique et épistémologie , Seyssel, Champ Vallon, 2008, esp. pp. 104-128.

Pour citer cet article

Référence papier.

Alain Suberchicot , « Why do Cultures Change? The Challenges of Globalization » , Transtext(e)s Transcultures 跨文本跨文化 , 4 | 2008, 5-17.

Référence électronique

Alain Suberchicot , « Why do Cultures Change? The Challenges of Globalization » , Transtext(e)s Transcultures 跨文本跨文化 [En ligne], 4 | 2008, mis en ligne le 20 septembre 2009 , consulté le 08 avril 2024 . URL : http://journals.openedition.org/transtexts/237 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/transtexts.237

Alain Suberchicot

Professor , American Studies, University of Lyon (Jean-Moulin)

Droits d’auteur

Le texte et les autres éléments (illustrations, fichiers annexes importés), sont « Tous droits réservés », sauf mention contraire.

Numéros en texte intégral

- 17 | 2022 Im/mobilités cinématographiques et planétarités contemporaines

- 16 | 2021 La liberté académique en contexte global : défis et perspectives

- 15 | 2020 Censure et productions culturelles postcoloniales

- 14 | 2019 Re-thinking Latin America: Challenges and Possibilities

- 13 | 2018 Représentations de la nature à l'âge de l'anthropocène

- 12 | 2017 The Other’s Imagined Diseases. Transcultural Representations of Health

- 11 | 2016 Le genre de la maladie : pratiques, discours, textes et représentations

- 10 | 2015 Manger, Représenter: Approches transculturelles des pratiques alimentaires

- 9 | 2014 Géopolitique de la connaissance et transferts culturels

- 8 | 2013 Genre et filiation : pratiques et représentations

- 7 | 2012 Transcultural Identity and Circulation of Imaginaries

- 6 | 2011 Debating China

- 5 | 2009

- 4 | 2008 Cultures in Transit

- Hors série | 2008 Poésie et insularité

- 3 | 2007 Global Cities

- 2 | 2007

- 1 | 2006

Tous les numéros

- Présentation

- Comité de rédaction

- Instructions for Authors

Informations

- Politiques de publication

Suivez-nous

Lettres d’information

- La Lettre d’OpenEdition

Affiliations/partenaires

ISSN électronique 2105-2549

Voir la notice dans le catalogue OpenEdition

Plan du site – Crédits – Flux de syndication

Politique de confidentialité – Gestion des cookies – Signaler un problème

Nous adhérons à OpenEdition – Édité avec Lodel – Accès réservé

Vous allez être redirigé vers OpenEdition Search

- Frontiers in Psychology

- Cultural Psychology

- Research Topics

Cultural change: Adapting to it, coping with it, resisting it, and driving it.

Total Downloads

Total Views and Downloads

About this Research Topic

With rapid social and economic changes, there is an increased interest in understanding the psychological impact of being in a society in transition, whether those changes are due primarily to internal pressures (e.g., cultural revolution, modernization, etc.) or due primarily to external pressures ...

Important Note : All contributions to this Research Topic must be within the scope of the section and journal to which they are submitted, as defined in their mission statements. Frontiers reserves the right to guide an out-of-scope manuscript to a more suitable section or journal at any stage of peer review.

Topic Editors

Topic coordinators, recent articles, submission deadlines.

Submission closed.

Participating Journals

Total views.

- Demographics

No records found

total views article views downloads topic views

About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets & Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Social Impact

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Services

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

How to Get Beyond Talk of “Culture Change” and Make It Happen

Experts outline their roadmap for intentionally changing the culture of businesses, social networks, and beyond.

February 20, 2024

Calls for cultural transformation have become ubiquitous in the past few years, encompassing everything from advancing racial justice and questioning gender roles to rethinking the American workplace. Hazel Rose Markus recalls the summer of 2020 as a watershed for those conversations. “Everybody was saying, ‘Oh, the culture has to change,’” says Markus, a professor of psychology at Stanford. “It was just rolling off everybody’s lips in every domain.” Yet no one seemed to know what exactly that might entail or how to get started.

As they followed these discussions, Markus and her colleagues Jennifer Eberhardt and MarYam Hamedani wondered what they could contribute at this moment as experts with years of experience studying how communities and organizations can turn the desire for change into something real. “Culture is all around us, but at the same time, it feels out of reach for a lot of people,” says Eberhardt, a professor of organizational behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business and of psychology in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

Markus and Eberhardt are the faculty co-directors of Stanford SPARQ , a “do tank” that brings researchers and practitioners together to apply the lessons of behavioral science to combating bias and disparities; Hamedani is its executive director and senior research scientist. Recently, along with associate director of criminal justice partnerships Rebecca Hetey , they published an evidence-based roadmap to intentional cultural change in American Psychologist . They hope, Hamedani says, to illustrate “a path forward and to make the claim that culture change is possible.”

Stanford Business spoke with Eberhardt, Hamedani, and Markus to discuss the complexities of changing a culture and how leaders and readers who are committed to doing things differently can get started.

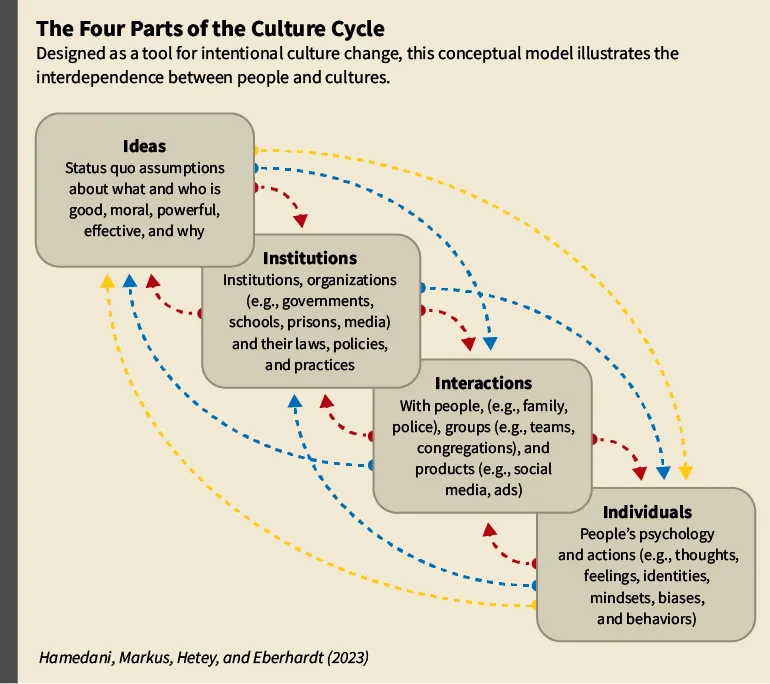

You start the paper with the “four I’s,” categories you believe can help people map their cultures and see where there might be tensions or mismatches. Using organizational cultures as an example, can you take us through those?

Hazel Rose Markus: There are the ideas , the big ideologies that are foundational for any organization: This is how we do things, what’s good, and what we value. Then the institutional parts, which are the everyday policies and practices that people use to do their work. Often, those have been in place for a long time and people tend to follow them as if they were the natural order of things. Another I is the interactions, which have to do with what’s going on in the office every day, in your relationships with your colleagues, with the people you supervise, with those you answer to. And finally, the fourth part is your own individual attitudes, feelings, and actions.

Is there a way to sum up your roadmap for changing culture?

MarYam Hamedani: The first key idea is because we built it, we can change it. There are many forces out there that are out of our control, but the societies we build and pass on — the organizations, the institutions, the way we live our lives — those are things that are human-made. And so we should feel empowered by that inheritance because that’s the thing that gives us the ability to make change.

The second part is that culture change usually involves a series of power struggles and clashes and divides. You have different groups that feel like they’re winning and losing. There’s a lot at stake for people. It’s important to try to have strategies to deal with that.

Finally, culture change can be unpredictable and have unintended consequences. Yet the dynamics can also follow patterns — for example, backlash happens. Timing matters. So you have to be nimble; you have to realize that cultural change never ends. It’s a sustainable process that you have to stay on top of, and that’s OK.

Markus: Yes, changemakers can’t be discouraged when they see backlash. Also, we want to help people remember that yes, they are individuals, but they are also making culture through their actions. How our everyday actions can contribute to a larger culture and to its change is something I think we are less likely to think about in our individualistic system.

Hamedani: Right. We are individuals and in charge of our own behavior, but then we are powerful as a group.

Markus: With each other, what are we modeling? What are we putting our efforts behind? What’s the impact on the workplace?

Your paper was written with the problem of social inequality in mind. What message does it have for business leaders?

Jennifer Eberhardt: As business leaders, you have both a lot of power and, I think, a lot of obligation to understand the workings of culture. You have the power to pull the levers of change. You dictate what the social environment is like for everyone else. So you have a heavy hand in creating and sustaining the culture that is there — but you can also have a heavy hand in changing that culture for the better.

Markus: When culture change is on the agenda, you often hear leaders — like those in the tech industry — and the first thing they often say is, “OK, I’m going on a listening tour.” But you rarely hear about what they’re going to listen for or what they heard from those who report to them or how they’re going to put that into action.

Listening is valuable because it conveys empathy, but it is useful to listen specifically for what people understand as the important values of our organization, the undergirding ideas. What are we about? What are we trying to be as an organization? And, very importantly, do our policies and practices reflect these ideas and values and our mission? We can say we’re about one thing or another, but how is it materialized? How does it show up in our everyday work? Is there a general alignment across the four I’s of the culture?

You worked with Nextdoor on a project to change its culture. How did that go?

Eberhardt: They reached out to me and other researchers trying to figure out how to curb racial profiling on their platform. In the tech industry, people are focused on building products that are easy to use, products that are intuitive, so that users don’t really have to think too hard. But those are also conditions under which racial bias might thrive. So we encouraged them to slow users down, to increase friction rather than trying to take friction away.

Quote As business leaders, you have both a lot of power and, I think, a lot of obligation to understand the workings of culture. You have the power to pull the levers of change. Attribution Jennifer Eberhardt

They accomplished this by creating a checklist for users to review before posting on a Nextdoor forum. The first thing they ask people to consider is that a person’s race is not an indication of their criminal activity. And also when they describe a person, you don’t just describe their race, you describe their behavior. What are they doing that seems suspicious? Nextdoor found that just simply slowing people down in this way, based on these social psychological principles, they were able to reduce profiling by over 75%.

They were trying to solve for something at the interaction level. What they could change was what the experience was like for users at the institutional level. Just by making these simple tweaks to the platform itself and how they presented information, they changed these negative interactions that were taking place that then could also shape people’s ideas about race.

You also talk in the paper about the example of investment firms struggling to become more diverse.

Markus: Typically this has been the territory of white men with economics degrees from Harvard, Yale, Stanford, Princeton. It was a closed and locked world. In studies we did in the investing domain, we found that race can influence professional investors’ financial judgments. Many people in the industry would like to create a culture that is more open and inclusive, but there is a powerful default assumption at work that acts as a barrier. In a lot of these firms, the default is still, “I know in my gut what a successful idea is and who is likely to build a company that can grow. I can see it and feel it, and either you match or you don’t match.”

It seems like a point of tension where the institutional level says it wants change, but at the interaction level, this is still a relationship-driven industry. So what do you do about that?

Hamedani: It depends where in the culture map you want to start. Let’s say you diversify the students coming in and getting MBAs. Then you have to look at how are they’re being mentored and supported through their schooling experience, through the internships and job opportunities that they have. Are you simply assuming that they should assimilate to the default? Are you training a new, exciting, and diverse group of people to act like those that have been there all along? Or are you incorporating their ideas and diverse ways of being that might look or sound different and affording them the same respect and status? Are you teaching them how to do a pitch a certain way because there’s only one right way to do a pitch? Or might they have other styles of communication or ways of selling an idea?

At the GSB, Jennifer has a class, Racial Bias and Structural Inequality , where she brings in all these amazing CEOs who are women and people of color. Most of the students, they’ve never seen it before. And that’s what happens to people in these investment firms: They haven’t seen it before. Even that intervention of seeing, week after week, these leaders coming in and the students get to ask them questions and have a conversation with them — that’s an interaction .

Eberhardt: I had Sarah Friar , MBA ’00, the CEO of Nextdoor, come in. I had the president of Black Entertainment Television, Scott Mills , come in; I had the police chief of San Francisco, William Scott , come in — they are both African American.

And the hope is that these students who will go on to work in the business world will have a broader definition of what is a “culture fit”?

Hamedani: Exactly right. And more specifically, a “leader fit.” And for women and students of color, that they can also see themselves as leaders. But it takes things happening at all levels in the culture map to make that happen. You’re seeding this change and then the levels are reinforcing each other to help it grow.

What would you recommend as a starting place for readers who are thinking that they want to spark intentional cultural change wherever they are?

Markus: It would begin with mapping the culture: What matters to us, what do we value? And then, to the extent that there’s some consensus about our culture, reflecting on whether our ways of doing things reflect this. In so many organizations we’re working with now, there’s really a gap between what leaders feel their values are, what they care about, and what the employees are experiencing. What we see is that it’s important to give the employees chances to get together to talk about this and have some company time, some paid time, to discuss these issues —

Hamedani: — to vision the future. Because there’s that virtue signaling, “OK, we care about that, but really we’re so busy and we have all these things to do. We have to hit our targets for the quarter or for the year.” Of course, those things are important, but are people — employees and leaders alike — participating in visioning that future and laying out the goals and objectives together? Can you make some small or even larger changes such that people feel empowered that they’re part of building that culture together?

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom .

Explore More

Conflict among hospital staff could compromise care, hardwired for hierarchy: our relationship with power, taking a stand with your brand: genderless fashion in africa, editor’s picks.

We Built This Culture (so We Can Change It): Seven Principles for Intentional Culture Change MarYam G. Hamedani Hazel Rose Markus Rebecca C. Hetey Jennifer Eberhardt

May 30, 2023 Will a Police Stop End in Arrest? Listen to Its First 27 Seconds. Researchers have identified a linguistic signature that can predict whether encounters with cops will escalate. Black drivers hear this pattern as well.

August 01, 2023 Follow the Leader: How a CEO’s Personality Is Reflected in Their Company’s Culture There’s no ideal personality type for executives — but businesses need the right one for success.

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Business Transformation

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships and Prizes

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Get Involved

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- Career Advancement

- Career Change

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- Information for Recommenders

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- After You’re Admitted

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- Videos, Code & Data

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Reading Materials

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

- Founding Donors

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Program Contacts

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Firsthand (Vault)

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Review of Revitalizations & Mazeways: Essays on Culture Change, Vol. 1. (Anthony Wallace), 2005

2005, American Anthropologist 107(3): 549

Related Papers

Nomadic Societies in the Middle East and North Africa

Mariella Villasante Cervello

ilias sabbir

American Anthropologist

Matthew Liebmann

ABSTRACT Although Wallace's revitalization movement model has been successfully utilized in scores of ethnographic and ethnohistorical studies of societies throughout the world, revitalization is considerably less well documented in archaeological contexts. An examination of the materiality of revitalization movements affords an opportunity to redress this lack by investigating how material culture creates and constrains revitalization phenomena. In this article, I reconsider the revitalization model through a case study focusing on the archaeology of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, emphasizing the central role of materiality in the formation and mediation of these movements. In doing so, I examine the archaeological signatures of revitalization movements, concluding that they are highly negotiated and heterogeneous phenomena and that the materiality of these episodes cultivates cultural innovation. I also seek to demonstrate that the distinctive types of material culture produced through revitalization are not epiphenomenal but, rather, are crucially constitutive of revitalizing processes.

Anna Marie O'Leary

Quetzil Castañeda

Abstract. This essay explores the history of the political structure of town and municipal authority in a specific case study of a Yucatec Maya community. The town is Pisté, a community that has become a significant tourist center that provides services for the nearby archaeological and tourist site of Chichén Itzá. A descriptive history of the town, mostly based in secondary literature and key primary sources from archives, is presented with two goals in mind. The first objective is to address ethnographically specific questions regarding the politics of this community, including the 1989 attempt to redefine itself as a ‘‘new’’ county according to Mexico’s 1917 Revolutionary Constitution. The second objective is to raise questions and broader issues regarding new social movements, state formation analyzed from the ‘‘bottom-up,’’ the importance of the authority structure of the town/county as a governmental strategy of theMexican state, and the ethnographic and historical study of the 1980s’ crises in Yucatán. The case study contributes to Yucatec studies by pointing attention away from the political-economic core of Mérida, the usual institutions (church, hacienda, and highly capitalized economic sectors), and typical topics (e.g., party politics, elite factionalism) that have been the focus of Yucatec historiography. By directing attention to areas (communities in the milpa zone) and topics (the political and cultural forms of rural communities) that have been marginalized by Yucatec historians but that have been a favored topic of U.S.-based cultural anthropologists seeking idealized Maya culture, this essay raises new research questions for which yet another rapprochement is necessary in Yucatec studies between the fields of history and cultural ethnography.

The Americas

Dan La Botz

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute

lamont lindstrom

Kimberly Theidon

Journal of Political Ecology

Political ecology has expanded in multiple new directions since Piers Blaikie's explanation of the manifestations of political economy and ecology in the "problem" of soil erosion in the 1980s. In this article, I try to extend political ecology to engage with ethnic studies literature on coloniality, and indigenous perspectives on intergenerational trauma and healing. Drawing on historic and contemporary examples of Maidu governance and resource development in the Maidu homeland, California, USA, I extend the concept of intergenerational trauma in Native American communities from the individual and ethnic group levels to include the community's relationship with the land, and the concept of itself as a sovereign civic, governing body. I place specific manifestations of trauma, de-colonizing, and healing, as exemplified by Maidu natural resource activism, in dialogue with political ecology approaches to better understand the relationships between historically colonized people, governance, and land. I argue that the relationships between people and resources that political ecology focuses on cannot be adequately understood in historically colonized communities dealing with neo-colonial resource and political policies, without attention to perspectives on coloniality/de-coloniality, and trauma/healing. These perspectives come from both survivors of colonialism, and from ethnic studies and indigeneity scholars. Desde que Piers Blaikie explicó la importancia de combinar la economía política y ecología para explicar el "problema" de la degradación del suelo, la ecología política se ha expandido en múltiples direcciones. En este articulo combino la ecología política con las áreas de derechos ambientales, epistemologías, y la historia ambiental, a través de un dialogo entre estudios étnicos sobre colonialidad y perspectivas indígenas sobre trauma intergeneracional y curación. Para ello, utilizo ejemplos históricos y actuales de cómo los Maidu de California, USA gobiernan y desarrollan a sus recursos naturales, extendiendo el concepto de trauma intergeneracional para discutir la relación entre comunidad y tierra, y la formación de la consciencia de que el pueblo Maidu es un grupo soberano. Así mismo analizo, desde la ecología política, manifestaciones de trauma y curación encontrados en el activismo Maidu, para explicar a un nivel más general las relaciones entre tierra, gobernanza y descolonización. "Political ecology" a augmenté dans de multiples directions de nouveau depuis les explications de Piers Blaikie de l'érosion des sols dans les années 1980. J'encourage l'approche d'examiner aussi les droits environnementaux, de l'épistémologie, et l'économie politique historique. "Political ecologists" doivent apprendre à partir d'études ethniques et colonialité. Je tire sur des exemples du développement des ressources et gouvernance dans la patrie Maidu, Californie, USA. La notion de traumatisme intergénérationnel dans les communautés amérindiennes est pertinente pour les individus, ainsi que pour la relation de la communauté avec la terre. Je discute aussi des réflexions de la communauté Maidu sur son rôle en tant que souverain, institution d'administration. L'étude des traumatismes et la guérison nous aider à comprendre les souffrances d'un peuple historiquement colonisés et leur retrait de terres coutumières. La documentation pertinente qui "political ecology" doit prendre en compte vient de survivants du colonialisme, et d'études ethniques et de l'indigénéité.

Journal of the Anthropology of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology

Aaron Ansell

RELATED PAPERS

Sztuka Edycji

Beata Dorosz

International Journal Of Community Medicine And Public Health

ritu rochwani

IEEE Transactions on Image Processing

Raul Serapioni

ASIAN JOURNAL OF HOME SCIENCE

sadhana Kulloli

Luís Fontes

Abdulkadir Ozden

Jurnal Teknik Elektro ITP

yefriadi yefriadi

Jurnal Pendidikan Bahasa dan Sastra

Muhammad Sukarno

Sexualidad, Salud y Sociedad (Rio de Janeiro)

Carlos Eduardo Henning

alvaro contreras

Revista Competitividade e Sustentabilidade

Edson Neves

International Journal of Food Science

budi sustriawan

Creon Levit

Digestive and Liver Disease

Rosa Liotta

pedro granados

Aquaculture

Kenneth Cain

Environmental Science and Pollution Research

Slobodan Gadžurić

Ahmet Kayabaşı

Journal of Marriage and the Family

Haematologica

Marta Morado

Health Benefits Of Dry Sauna

Miracle H E A L T H Secrets

Review of Scientific Instruments

Heebum Chun

Digital Rights and Inclusion Report

Yohannes Eneyew Ayalew

The Journal of Pediatric Research

Ozlem Erdede

Revista Eletrônica de Enfermagem

REGIANE APARECIDA DOS SANTOS SOARES BARRETO

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essay Examples >

- Essays Topics >

- Essay on Culture

Free Essay On Cultural Change

Type of paper: Essay