National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Plan Your Visit

- Group Visits

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Accessibility Options

- Sweet Home Café

- Museum Store

- Museum Maps

- Our Mobile App

- Search the Collection

- Exhibitions

- Initiatives

- Museum Centers

- Publications

- Digital Resource Guide

- The Searchable Museum

- Freedmen's Bureau Search Portal

- Early Childhood

- Talking About Race

- Digital Learning

- Strategic Partnerships

- Ways to Give

- Internships & Fellowships

- Today at the Museum

- Upcoming Events

- Ongoing Tours & Activities

- Past Events

- Host an Event at NMAAHC

- About the Museum

- The Building

- Meet Our Curators

- Founding Donors

- Corporate Leadership Councils

- NMAAHC Annual Reports

Black is Beautiful: The Emergence of Black Culture and Identity in the 60s and 70s

The phrase “black is beautiful” referred to a broad embrace of black culture and identity. It called for an appreciation of the black past as a worthy legacy, and it inspired cultural pride in contemporary black achievements.

Pride and Power Black Americans donned styles connected to African heritage. Using a grooming tool like an Afro pick customized with a black fist was a way to proudly assert political and cultural allegiance to the Black Power movement.

(left) A wooden Afro-pick comb from Ghana, 1950. G ift of the Family of William & Mattye Reed. 2014.182.99 (right) Afro-pick manufactured by Eden Enterprise, Inc. The pick has a black molded plastic handle shaped like a raised fist. G ift of Elaine Nichols . 2014.125.1

A Cultural Revolution “Black is beautiful” also manifested itself in the arts and scholarship. Black writers used their creativity to support a black cultural revolution. Scholars urged black Americans to regain connections to the African continent. Some studied Swahili, a language spoken in Kenya, Tanzania and the southeastern regions of Africa.

Publication cover of "Negro Digest," July 1969. 2014.154.11

Across this country, young black men and women have been infected with a fever of affirmation. They are saying, ‘We are black and beautiful.’ Hoyt Fuller 1968

“I’m So Pretty” Muhammad Ali’s style of boxing boasted its own brand of beauty. His graceful footwork and charismatic confidence attracted audiences to his moves and his message.

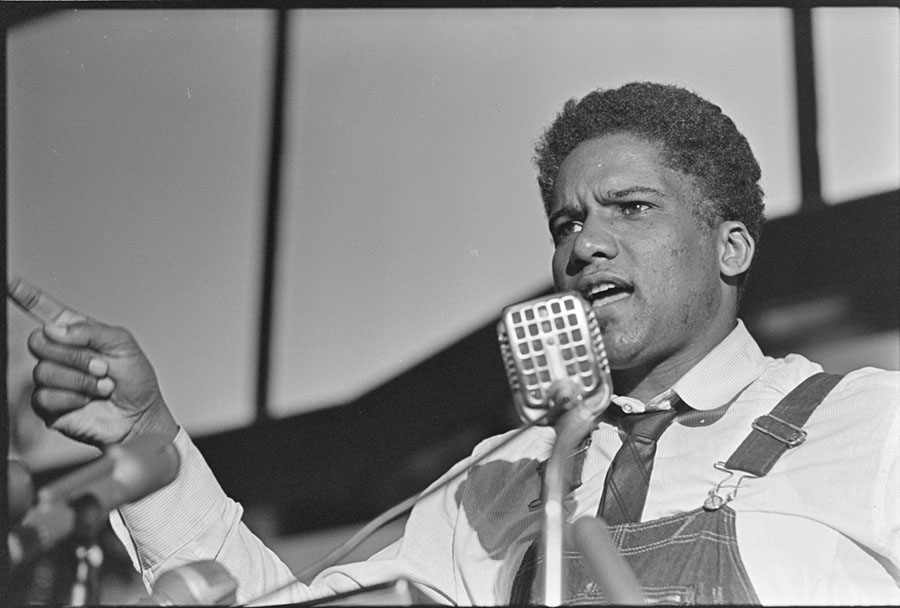

Icons of the Black Arts Movement The beginnings of the Black Arts Movement solidified around the arts-activism of Amiri Baraka (formerly LeRoi Jones) in the mid-1960s. A poet, playwright and publisher, Baraka was a founder of the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School in Harlem and Spirit House in Newark, N.J., his hometown. Baraka’s initiatives on the East Coast were paralleled by black arts organizations in Atlanta, Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, New Orleans and San Francisco, leading to a national movement.

Poet, playwright and political activist Amiri Baraka addresses the 1972 National Black Political Convention in Gary, Ind.

"Some people say we got a lot of malice Some say it's a lotta nerve But I say we won't quit movin' Until we get what we deserve ... Say it loud - I'm black and I'm proud!"

JAMES BROWN Lyrics from "Say It Loud - I'm Black and I'm Proud," 1968. © Warner Chappell Music, Inc.

Negro Es Bello II, by Elizabeth Catlett, 1969 Negro Es Bello translates from Spanish as “black is beautiful.” Placing those words alongside panther imagery, the artist connects black pride with Black Power.

"The Black Aesthetic" (Doubleday, 1971), by scholar Addison Gayle, are essays that call for black artists to create and evaluate their works based on criteria relevant to black life and culture. Their aesthetics, or the values of beauty associated with the works of art, should be a reflection of their African heritage and worldview, not European dogma, the contributors stated. A black aesthetic would embolden black people to honor their own beauty and power.

"The Black Aesthetic," by Addison Gayle

Race and Representation Problems of race and representation emerged in popular entertainment as well as in politics. In the 1967 film "Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner," audiences were encouraged to identify positively with Sidney Poitier’s portrayal of a well-mannered black doctor with a white fiancée, only six months after interracial marriage was made legal in all states. In Alex Haley's "Roots", the ground-breaking 1977 television mini-series, viewers were unapologetically confronted with the brutality and rupture of American slavery, and the horrors African Americans experienced at the hands of white slaveholders.

Shifting the Lens In 1967, interracial marriage gets a feel-good treatment in the film "Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner." 2013.108.9.1

(left) Lobby card for the film.

Popular Culture Prior to the mid-1960s, African Americans appeared in popular culture as musical entertainers, sports figures, and in stereotypical servant roles on screen. Empowered by the black cultural movement, African Americans increasingly demanded more roles and more realistic images of their lives, both in mainstream and black media. Black journalists used the talk-show format to air community concerns. Television programs featuring black actors attracted advertisers who tapped into a growing black consumer base.

"The Flip Wilson Show" This popular, one-hour variety shown ran on NBC from 1970-74.

(left) Time magazine (Vol. 99, No. 5) cover from 1972 featuring a drawing of Flip Wilson. 2014.183.4

"Julia" Diahann Carroll won a Golden Globe Award for Best TV Actress, Musical/Comedy in 1969 for "Julia" where she starred as a nurse, widow, and single mother in this situation comedy. Her role was one of the first portrayals of a black professional woman on television.

Lunchbox printed with illustrations of actors from the sitcom "Julia," 1969. 2013.108.13ab

Having a Say Black journalists and filmmakers produced public affairs television programs in major cities. Community concerns and international affairs guided the shows, including "Say Brother" in Boston and "Right On!" in Cincinnati. "Soul!" and "Black Journal" were broadcast nationally. Their topics ranged from the Black Power Movement to women’s roles, religion, homosexuality and family values. Radio programs similarly focused on agenda items important for sustaining and empowering black communities.

The TV show "Like It Is" focused on issues relevant to the African American community, produced and aired on WABC-TV in New York City between 1968 and 2011. Gil Noble hosts this special episode (below) from 1983 which explores the life and legacy of Malcolm X and the CIA's covert war to destroy him, featuring interviews with confidants Earl Grant and Robert Haggins.

We use the video player Able Player to provide captions and audio descriptions. Able Player performs best using web browsers Google Chrome, Firefox, and Edge. If you are using Safari as your browser, use the play button to continue the video after each audio description. We apologize for the inconvenience.

"Like It Is" was a public affairs television program, WABC-TV in New York.

Television is on the brink of a revolutionary change ... The stations are changing - not because they like black people but because black people, too, own the airwaves and are forcing them to change. Tony Brown 1970

Soul Train This televised musical program featured in-studio dancers showcasing the latest moves. The show brought African American cultural expression into millions of non-black households. Photo circa 1970.

Diana Ross and Billy Dee Williams Star in "Mahogany" Released in 1975, Mahogany was a romantic drama that also explored the serious issue of gentrification through William’s character, a political activist in Chicago.

Subtitle here for the credits modal.

Our Favorite Essays by Black Writers About Race and Identity

Books & Culture

A personal and critical lens to blackness in america from our archives.

It’s fitting that two of the first three essays in this roundup are centered on examining the Black American experience as one of horror. In a year when radical right-wing activists are truly leaning in, we’ve already seen record numbers of anti-LGBTQ legislation, the very real possibility of the end of Roe v. Wade, and more fervent redlining measures to keep Black people (and other marginalized communities) from voting. Gun violence is at an all time high, in particular mass shootings.

Since the success of Jordan Peele’s runaway hit film Get Out , there has been a steady rise in films depicting the Black American experience for the fraught, nuanced, dangerous life that it can be. This narrative isn’t entirely new, but this is the first time these films have gained critical acclaim and commercial attention. The reason is simple. Whatever the cause—social media, an increasingly diverse population—America can’t run from itself anymore. Our entertainment is finally asking the question that Black people have been asking for generations: In America, who is the real boogeyman?

Naturally, the discourse and critical analyses must follow suit. But it doesn’t stop there: the essays on this list span far and wide when it comes to subject matter, critical lens, and personal narrative. There are essays about Black friendship, the radical nature of Black people taking rest, and the affirmation of Black women writing for themselves, telling their own stories. Icons like Michelle Obama, Toni Morrison, and Gayle Jones get a deep dive, and we learn that we should always have been listening to Octavia Butler. This Juneteenth, I hope you’re taking a moment to reflect, on America’s troubled legacy, and to celebrate the ways that Black people continue to thrive.

Modern Horror Is the Perfect Genre for Capturing the Black Experience

Cree Myles writes about the contemporary Black creators rewriting the horror genre and growing the canon:

“Racism is a horror and should be explored as such. White folks have made it clear that they don’t think that’s true. Someone else needs to tell the story.”

Modern Narratives of Black Love and Friendship Are Centering Iconic Trios

Darise Jeanbaptiste writes about how Insecure and Nobody’s Magic illustrate the intricacy of evolving Black relationships:

“The power of the triptych is that it offers three experiences in addition to the fourth, which emerges when all three are viewed or read together.”

I Was Surrounded by “Final Girls” in School, Knowing I’d Never Be One

Whitney Washington writes that the erasure of Black women in slasher films has larger implications about race in America:

“Long before the realities of American life, it was slasher movies that taught me how invisible, ignored, and ultimately expendable Black women are. There was no list of rules long enough to keep me safe from the insidiousness of white supremacy… More than anything, slasher movies showed me that my role was to always be a supporting character, risking my life to be the voice of reason ensuring that the white girl makes it to the finish line.”

“Palmares” Is An Example of What Grows When Black Women Choose Silence

Deesha Philyaw, author of The Secret Lives of Church Ladies , writes that Gayl Jones’ decades-long absence from public life illuminates the power of restorative quiet:

“These women’s silences should not be interpreted as a lack of understanding or awareness, but rather as an abundance of both, most especially the knowledge of what to keep close to the vest, and the implications for failing to do so. They know better than to explain themselves, their powers and their origins, their beliefs and reasons, their magic. These women are silent not because they don’t know anything. They are silent because they know better.”

Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye” Showed Me How Race and Gender Are Intertwined

For the 50th anniversary of Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye , Koritha Mitchell writes how the novel taught her that being a Black woman is more than just Blackness or womanhood:

“I didn’t have the gift of Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of ‘intersectionality,’ but The Bluest Eye revealed how, in my presence, racism and sexism would always collide to produce negative experiences that others could dodge. It was not simply being Black or being dark-skinned that mattered; it was being those things while also being female.”

The Delicate Balancing Act of Black Women’s Memoir

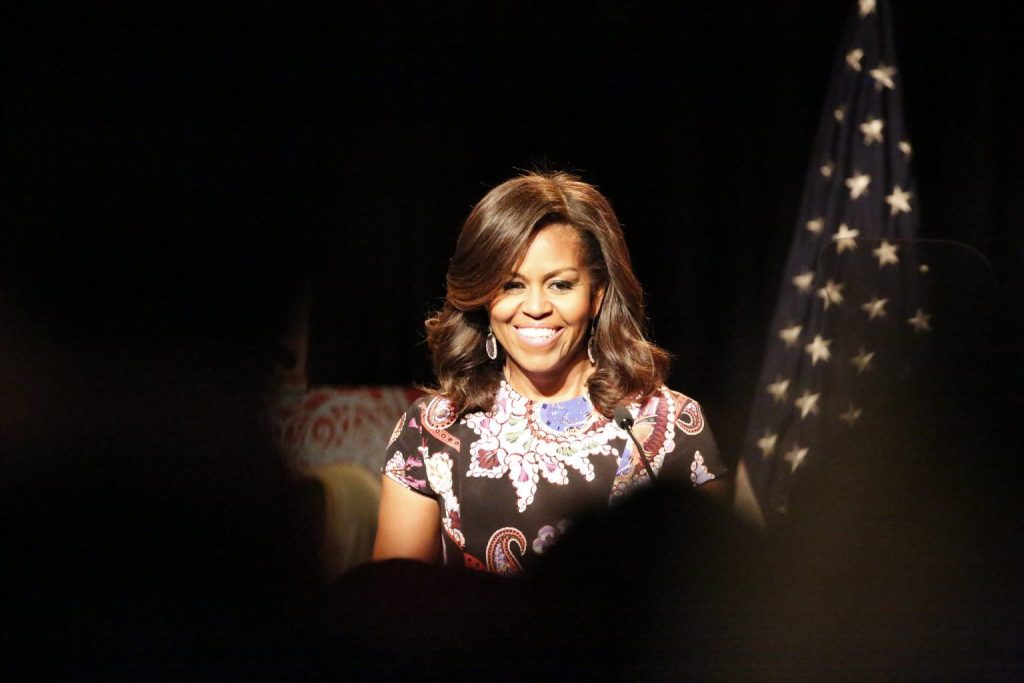

Koritha Mitchell writes about how Michelle Obama’s Becoming illustrates larger tensions for Black women writing about themselves:

“In other words, when Black women remain enigmas while seeming to share so much, they create proxies at a distance from their psychic and spiritual realities because they are so rarely safe in public. Despite the release of her memoir, audiences will never be privy to who Michelle Obama actually knows herself to be, and that is more than appropriate.”

50 Years Later, the Demands of “The Black Manifesto” Are Still Unmet

Carla Bell writes about James Forman’s famous 1969 address, The Black Manifesto , and its contemporary resonances:

“But the Manifesto is as vital a roadmap in our marches and protests today as the day it was first delivered. We, black people in America, remain compelled by the power and purpose of The Black Manifesto, and we continue to demand our full rights as a people of this decadent society.”

You Should Have Been Listening to Octavia Butler This Whole Time

Alicia A. Wallace writes that Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower isn’t just a prescient dystopia—it’s a monument to the wisdom of Black women and girls:

Through her protagonist Lauren Olamina, Butler has been telling the world for decades that it was not going to last in its capitalist, racist, sexist, homophobic form for much longer. She showed us the way injustice would cause the earth to burn, and the importance of community building for survival and revolution. Through Parable of the Sowe r, we had a better future in our hands, but we did not listen.

The Book You Need to Fully Understand How Racism Operates in America

Darryl Robertson writes about Ibram X. Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning and its examination of the history of overt and covert bigotry:

“While How to Be an Antiracist is an informative and necessary read, it is his National Book Award-winning, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America that deserves extra attention. If we want to uproot the current racist system, it’s mandatory that we understand how racism was constructed. Stamped does just that.”

I Reject the Imaginary White Man Judging My Work

Tracey Michae’l Lewis-Giggetts turns to Black writers as inspiration for resisting white expectations:

“…it doesn’t only matter that I’m a Black woman telling my story. What matters is the lens through which I’m telling it. And sometimes, many times, that lens, if we’re not careful, can be tainted by the ever-present consciousness of Whiteness as the default.”

Toni Morrison Gave My Own Story Back to Me

The incomparable literary powerhouse showed Brandon Taylor how to stop letting white people dictate the shape of his narrative:

“That’s the magic of Toni Morrison. Once you read her, the world is never the same. It’s deeper, brighter, darker, more beautiful and terrible than you could ever imagine. Her work opens the world and ushers you out into it. She resurfaced the very texture and nature of my imagination and what I could conceive of as possible for writing and for art, for life.”

Art Must Engage With Black Vitality, Not Just Black Pain

Jennifer Baker writes that books like The Fire This Time give depth and nuance to a reflection of Blackness in America:

“These essays provided a deeper connection because Black pain was part of the story; Black identity, self-recognition, our own awareness brokered every page. Black pain was not the sole criterion for the anthology’s existence.”

When Black Characters Wear White Masks

Jennifer Baker writes that whiteface in literature isn’t a disavowal of Blackness, but a commentary on privilege:

“Whiteface stories interrogate the mentality that it’s better to be white while examining how societal gains as well as societal “norms” inflict this way of thinking on Black people. Being white isn’t better, but, for some of these characters, it seems a hell of a lot easier, or at least preferable to dealing with racism.”

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven't read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.

ARTICLE CONTINUES AFTER ADVERTISEMENT

Traveling South to Understand the Soul of America

Imani Perry examines how the history of slavery, racism, and activism in the South has shaped the entire country

Jun 17 - Deirdre Sugiuchi Read

More like this.

In “James,” Percival Everett Does More than Reimagine “Huck Finn”

The author discusses writing from the perspective of Jim and language as a tool of oppression

Mar 19 - Bareerah Ghani

The Stakes of Driving While Black Are Unconscionably High

"Wedding Season (A Nocturne for Sandra Bland)," excerpted from the essay collection "You Get What You Pay For"

Mar 12 - Morgan Parker

10 Memoirs and Essay Collections by Black Women

These contemporary books illuminate the realities of the world for Black women in America

Nov 29 - Alicia Simba

DON’T MISS OUT

Sign up for our newsletter to get submission announcements and stay on top of our best work.

Morning Edition

Listen live.

BBC Newshour

In-depth analysis and commentary on today's biggest news stories as only the BBC can deliver. BBC "Newshour" covers everything from the growth of democracy to the threat of terrorism with a fresh, clear perspective from across the globe.

- Race & Ethnicity

The triple weight of being Black, American, and a woman

While we have always shared many of the concerns championed by the mainstream women’s movement, we have never had the luxury of fighting a singular fight..

- Sara Lomax-Reese

Sara Lomax-Reese is shown with her mother, Beverly Lomax, who she says instilled in her a sense of pride and love of self. (Image courtesy of Laura Elam)

At times this three-ness has felt like a weight — having to navigate racism, sexism, implicit bias, and all the limitations that come when you’re placed in these tiny little boxes, often ignored or underestimated and told to wait your turn.

- “The unemployment rate for African Americans in 2017 (the last full year of data) was 7.5 percent, 0.8 percentage points higher than it was in 1968 (6.7 percent). The unemployment rate for whites was 3.8 percent in 2017 and 3.2 percent in 1968.

- “In 2015, the Black homeownership rate was just over 40 percent, virtually unchanged since 1968, and trailing a full 30 points behind the white homeownership rate, which saw modest gains over the same period.

- “The share of African-Americans in prison or jail almost tripled between 1968 (604 of every 100,000 in the total population) and 2016 (1,730 per 100,000). In 1968, African-Americans were about 5.4 times as likely as whites to be in prison or jail. Today, African-Americans are 6.4 times as likely as whites to be incarcerated.”

Deeply disturbing is the reality that, in 2018, Black people still suffer the brunt of systemic racism and inequality.

The last election laid bare the distance and disconnect between Black and white women. What could be more blatant than 94 percent of African-American women voting for Hillary Clinton, and 52 percent of white women — the majority — voting for Donald Trump? While I still haven’t recovered from this betrayal, it is sadly consistent with a long history in this country that shows, for white women, race often eclipses gender (and sanity).

As I look through my personal and professional lens as a Black woman CEO, I see WURD as an important part of the solution to the challenges facing us in this moment. The media is extremely powerful. It shapes and perpetuates perceptions. It creates thought leaders and opinion makers. It holds the powerful accountable to the people. And when done well, it can unify our community — regardless of the double- or triple-consciousness that shapes our world view — to empower us to fight the constructs and institutions designed to contain, destroy, or silence us.

Whether we like everyone on the air or everything that is said is not the point. In today’s world, we need a place where the Black community can be strengthened and fortified. Black Lives Matter. #MeToo matters. And right now, WURD is the only place that allows us to speak each and every day about the issues that matter most to our community: in our own voice, in an interactive format that’s hyperlocal and in real time.

So, as we celebrate Women’s History Month, and honor all of the women who have paved this path for us, I invite you to continue to listen, call in, tweet, attend our events, and be an active part of this community. That, in my mind, is something worth protecting and preserving.

Sara Lomax-Reese is the president and general manager of WURD Radio, LLC , Pennsylvania’s only African-American owned talk radio station.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

Brought to you by Speak Easy

Thoughtful essays, commentaries, and opinions on current events, ideas, and life in the Philadelphia region.

Part of the series

Mlk legacy conversations.

Philadelphia thought leaders examine the life, death, and legacy of Martin Luther King from January to April.

You may also like

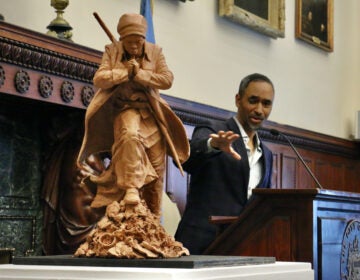

Philadelphia Art Commission approves work to begin on Harriet Tubman statue

Alvin Pettit’s statue design, “A Higher Power: The Call of a Freedom Fighter,” was selected from five finalists in a year-long process.

3 months ago

WURD’s ‘Radio XALAAT’ gives Philly’s African diaspora ‘a home on the radio dial’

A weekly radio program has served Philadelphia’s African diaspora for decades. As ‘Africatown’ comes into force, Radio XALAAT’s host looks back.

4 months ago

City of Philadelphia asking for artist submissions for permanent Harriet Tubman statue

The project, with a budget of $500,000, will be the first statue of an African American historic female figure in the city’s public art collection.

Want a digest of WHYY’s programs, events & stories? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Together we can reach 100% of WHYY’s fiscal year goal

In Dialogue: What is misunderstood about Blackness?

February 27, 2023

For decades, ‘Blackness’ has been a crucial political and cultural category that grounds a public discourse on cherishing a robust historical tradition and systemically uprooting white supremacy. As the term popularizes as a catch-all, however, so proliferate assumptions, narratives, and stereotypes that obscure the diversity of Black lived experiences. This month, we asked a few of our authors the following question: What do you find is commonly misunderstood about Blackness in America? Our authors brought together a wealth of experience and research from the worlds of literature, higher education, art, and criminal justice to illuminate shades and contradictions within Blackness and to offer paths out of reductive generalizations. In honor of Black History Month, we present this composite of perspectives that invites us to embrace a complex and heterogenous understanding of Black life, culture, and politics.

Korey Garibaldi ( Impermanent Blackness: The Making and Unmaking of Interracial Literary Culture in Modern America , 2023)

This is an exciting time to be reading and researching Black history and culture. Afrodiasporic authors that I study, including Alexandre Dumas père and Alexander Pushkin, monitored the arduous struggle for freedom in the antebellum U.S. and the global dimensions of Blackness. (Indeed, both mixed-race writers were fans of one another, and Dumas père wrote about Pushkin’s African great-grandfather, Abram Petrovich Gannibal, in the 1850s.) Several decades later, in 1936, Black scholar and diplomat Mercer Cook translated Dumas père ’s biographical writing on Pushkin for the Afro-American , a piece of literary history that is little remembered in our own time. My research sheds new light on the sheer scale and impermanence of cultural interracialism, which has deep, transnational resonances in the twenty-first century.

In 1891, Pushkin’s granddaughter Countess Sophie of Merenberg married Russia’s Grand Duke Michael, the cousin of the tsar at that time. That year, scores of American newspapers reported, disparagingly, that there was now “Negro Blood in the Royal Court.” Other papers, such as Norfolk’s Virginian and Carolinian , described Merenberg as Grand Duke Michael’s “Negro wife,” despite how white her (immediate) ancestry was. After the Grand Duke’s mother discovered that her son had married Pushkin’s granddaughter, she suffered a heart attack, passing away soon thereafter. Grand Duke Michael was blamed for his mother’s death, and the tsar banished the newlyweds from Russia, for life. They settled abroad permanently, even after the tsar’s banishment was lifted.

Several years later, Grand Duke Michael penned a novel, Never Say Die (1908), based on the story of his courtship of, and marriage to, Pushkin’s granddaughter. This semi-fictional tale, which he dedicated to his wife, followed the exploits of a “clever” but “very lazy” prince who is nevertheless trained to become “an exceptionally good soldier.” Fittingly, this young prince finds himself smitten with a general’s daughter, who is neither royal nor aristocratic. Moreover, the Grand Duke Michael’s protagonist, styled after himself, leads a “quiet, studious life of a man fond of his military profession,” who disavows “the gaieties of his father’s court.”

The visibility of race is a myth. And yet it remains common for Americans to ignore, overlook, or forget that Black identity (and African ancestry) comes in all shades.

In real life, the Russian Grand Duke’s contemporaries had long fixated on his marital dynamic with Merenberg, who was labeled a commoner despite her noble ancestry. “As is always the case in love affairs,” Grand Duke Michael noted in his lightly veiled account of their marriage, “society was exceedingly interested, and a great deal of gossip ensued.” Paradoxically, in the Grand Duke’s fictionalized memoir, the young prince’s father assured his son that he “would dearly love” his newest muse, “for his daughter-in-law, even in spite of the fact that the marriage would not receive recognition at the court.” Such vignettes are poignant. But it is not surprising that Grand Duke Michael’s melodramatic novel has been forgotten. At the time, some critics questioned how appropriate this book was, given the highly publicized controversy surrounding his unsanctioned marriage to Gannibal’s great-great-great-granddaughter.

For decades, Countess Sophie of Merenberg and her heirs were subject to racially motivated attacks. What is striking is that African American writers and publications—including the NAACP’s Crisis magazine, James Weldon Johnson, and numerous others—were consistent in defending Pushkin’s aristocratic descendants from “scientific” racism. The erasure of this cultural history from our collective memory is emblematic of broader misunderstandings about Blackness. The visibility of race is a myth. And yet it remains common for Americans to ignore, overlook, or forget that Black identity (and African ancestry) comes in all shades. Too often, people are taught that European heritage is synonymous with whiteness. We need more narratives of the past that defy tenacious stereotypes and pernicious biases like these that haunt the present.

Douglas S. Massey, Rory Kramer, & Camille Z. Charles ( Young, Gifted and Diverse: Origins of the New Black Elite , 2022)

In the US, Blackness was historically constructed as what sociologists call a “master status,” one in which any evidence of African ancestry defined one as “Black” and inferior, overriding all other individual traits and characteristics, erasing all differences between people labeled as Black. Black inferiority was built into the formal and informal structure of U.S. society and American social cognition, both implicitly and explicitly. African Americans, of course, contested this status, as did some White people. Little progress was made until the Civil Rights era of the 1960s and 1970s, and by most measures we still have quite a way to go.

The US Black population has always been diverse, even while enslaved, and that diversity has only grown in recent decades. As Blacks entered into sectors of American society from which they had long been excluded, they sought to redefine their place in the emerging post-Civil Rights social order. The Black middle class grew, and a new Black elite expanded. More recently, immigration from Africa and the Caribbean increased, as did rates of interracial partnering. There have also been modest steps toward the integration of schools and neighborhoods.

These sociodemographic shifts have increased and intensified intraracial diversity along the lines of race, class and gender, and also with respect to origins (mixed versus monoracial), immigrant generation (first, second, or multigenerational native), region of origin (parents from Africa, the Caribbean, or the US), segregation (childhood spent in Black, Mixed, or predominantly White settings), skin tone, and degree of exposure to disadvantaged circumstances.

Given the diversity among Black Americans today, any assumptions we make about the origins, experiences, and characteristics of someone you perceive as Black are likely to be wrong.

The increasing diversity of the Black population in the US—and the manifold intersectionalities that result—is the subject of our research. Drawing on a representative, longitudinal survey of Black students at selective colleges and universities and dozens of in-depth interviews, we show how diversity along these lines conditions experiences and outcomes with respect to identity, upbringing, academics, social life, prejudice and discrimination, attitudes, stress and mental health, and ultimately academic achievement and attainment.

Despite all the foregoing diversity—far more, in fact, than amongst students of other races—respondents lamented a singular, static image of “Blackness” replete with negative stereotypes against which they were constantly judged, not only by faculty, strangers and their institutions, but by their peers as well. Our findings emphasize that there is no single, “authentic” Black identity or experience. Nonetheless, a true sense of racial solidarity exists in spite of great intragroup diversity, resulting from a shared experience of being reduced to outdated notions of Blackness.

If there is one thing we’d like to impress upon people, it is that, given the diversity among Black Americans today, any assumptions we make about the origins, experiences, and characteristics of someone we perceive as Black are likely to be wrong. This is true not only in our day-to-day interactions, but also for the design and execution of programs within and outside of higher education needed to promote and support today’s manifold diversities.

Janet Dees ( A Site of Struggle: American Art against Anti-Black Violence , 2022)

As an art historian and a curator, I am interested in the role of the arts in the conversation surrounding racial justice. In my most recent project, I focused on excavating and presenting a historical perspective on artistic production that grappled with the issue of anti-Black violence in the United States. Focusing on the period between the rise of anti-lynching activism in the late 19 th century and the founding of Black Lives Matter in 2013, a portion of my research explores creative counterpoints to the assault of images of anti-Black violence that have been an enduring part of the American cultural landscape.

Art has not only been a vehicle for overtly supporting activism through protest-oriented work. It has additionally engaged in the conversation around racial justice in more subtle and complex ways, as an expression of mourning and memorialization and as a mode of processing the emotional and psychological impacts of racism. Art can serve as both an example and an embrace for those of us whose lives are impacted daily by racial injustice, as well as a catalyst for sustained action. Art does not necessarily directly change things, but art can change people, and people change things. In providing a window unto perspectives that may be different from our own, it cultivates empathy; by being a mirror of our own or similar experiences, it provides solace.

Another misunderstanding about “Blackness” in America is that the histories, struggles, and concerns of Black people should be “contained” rather than being seen as integral to the understanding of American history, culture, and society writ large.

An engagement with art and art history can illuminate the diversity and complexity of identities, interests, viewpoints, and contexts (gendered, geographical, social, religious, cultural, political, economic, etc.) that can be obscured by a mono-dimensional understanding of “Blackness” in America. In the realm of art, this can be as straightforward as understanding that artists who identify as Black have practiced and developed a range of artistic approaches from conceptualism to non-objective abstraction to figuration. Artists are shaped by various aspects of their identity, intellectual interests, and creative commitments. “Blackness,” however construed, may or may not be the best primary lens through which to engage their work.

Another misunderstanding about “Blackness” in America is that the histories, struggles, and concerns of Black people should be “contained” rather than being seen as integral to the understanding of American history, culture, and society writ large. In my research on art against anti-Black violence for example, I explored how artists from different cultural and racialized backgrounds—African American, Euro-American, Mexican American, Japanese American—took up this issue. Several works by artists as diverse as Reginald Marsh and Kerry James Marshall explore how perpetrators and bystanders are socialized into attitudes of anti-Blackness that are shared and passed down.

Art also can penetrate spaces and places that activist messages may not reach. This was what the NAACP’s Walter White hoped for in 1935 when he organized the exhibition An Art Commentary on Lynching to build awareness and support for anti-lynching legislation. It is also what I and my colleagues bore witness to at the Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University and Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, when the exhibition A Site of Struggle was on view in 2022.

Art is a space of creativity and imagination and, as such, offers fertile ground to envision what a just future society would like. Writer and meditation teacher Kate Johnson has put it this way: “The artists within and amongst us know how to make that vision of liberation visible so we can share it.” Art can give form to what we are fighting for, as well as deconstruct what we are fighting against.

Matthew Clair ( Privilege and Punishment: How Race and Class Matter in Criminal Court , 2022)

In the United States, a persistent cultural stereotype has long conflated Blackness with criminality. Writing at the end of the nineteenth century, W. E. B. Du Bois remarked that the study of the “Negro problem” for many White Southerners was really an investigation into what they perceived to be the problems of “ignorance, crime, and social degradation.” Today, the stereotype persists, with deadly consequences. Jennifer Eberhardt, a social psychologist, has conducted several experimental studies showing not only that Blackness is associated with criminality but also that the concept of crime triggers an association with Black people. In one experimental study, she and her colleagues showed how being primed with crime-relevant words, such as “violent,” caused police officers to attend more closely to Black men’s faces; police officers were also more likely to suggest that Black men’s faces appeared more “criminal” than those of White men.

People from all racial and class backgrounds engage in criminalizable behaviors; the difference is that anti-Black stereotypes about criminality and worthiness structure crime’s meaning and the way it is policed.

The stereotype of Black criminality is also perpetuated through academic knowledge and stylized facts. In the Condemnation of Blackness , historian Khalil Gibran Muhammad writes that “crime statistics became an innovative and scientific way of communicating the inferiority and pathologies of Black people after slavery.” Even the work of well-meaning academics today can perpetuate the myth. So much social science research on crime and inequality begins from the assumption of Black criminality, seeking, for instance, to locate the causes of observed Black-White disparities in crime rates in the pathologies of Black neighborhoods and communities. My work on criminalization begins from a different assumption. I examine how social and cultural processes within state institutions, rather than Black communities, disproportionately criminalize certain groups and manufacture crime statistics.

For example, in the first chapter of my book Privilege and Punishment , I argue that people from all racial and class backgrounds engage in criminalizable behaviors; the difference is that anti-Black stereotypes about criminality and worthiness structure crime’s meaning and the way it is policed. Black and Latino people in the study who grew up in working-class and poor homes often recounted the constant presence of police in their neighborhoods. Meanwhile, middle-class and White working-class people in the study described a lack of police surveillance, and when they were stopped by the police, many reported being viewed as credible (even when they were engaged in criminalizable acts). Some benefited from social ties with police officers in their community that allowed them to avoid arrests and investigations. Still, White and privileged people in my study engaged in substance use behaviors and physical violence that often harmed themselves, loved ones, and strangers. The myth of Black criminality not only perpetuates state violence against Black communities but also leaves social problems in White communities uninterrogated.

This exchange was facilitated by Akhil Jonnalagadda as part of the Princeton University Press Publishing Fellowship program .

Stay connected for new books and special offers. Subscribe to receive a welcome discount for your next order.

- ebook & Audiobook Cart

Get the latest news and stories from Tufts delivered right to your inbox.

Most popular.

- Activism & Social Justice

- Animal Health & Medicine

- Arts & Humanities

- Business & Economics

- Campus Life

- Climate & Sustainability

- Food & Nutrition

- Global Affairs

- Points of View

- Politics & Voting

- Science & Technology

- Alzheimer’s Disease

- Artificial Intelligence

- Biomedical Science

- Cellular Agriculture

- Cognitive Science

- Computer Science

- Cybersecurity

- Entrepreneurship

- Farming & Agriculture

- Film & Media

- Health Care

- Heart Disease

- Humanitarian Aid

- Immigration

- Infectious Disease

- Life Science

- Lyme Disease

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Oral Health

- Performing Arts

- Public Health

- University News

- Urban Planning

- Visual Arts

- Youth Voting

- Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine

- Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy

- The Fletcher School

- Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences

- Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging

- Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life

- School of Arts and Sciences

- School of Dental Medicine

- School of Engineering

- School of Medicine

- School of the Museum of Fine Arts

- University College

- Australia & Oceania

- Canada, Mexico, & Caribbean

- Central & South America

- Middle East

Black Identity and America’s Lingering Racism

Sociologist Orly Clerge says that the time is ripe for all blacks—from poor to rich—to unite to create political change in the U.S.

What it means to be black in America today lies at the complex intersection of race, class and space, says Tufts sociologist Orly Clerge, who is working on a book about the diversity of black identity in the United States. It compares the black immigrant experience to that of the African American middle class.

Clerge, an assistant professor of sociology and Africana studies in the School of Arts and Sciences, says she is trying to gain a better understanding of the meanings attached to blackness. How it’s defined by blacks themselves has important political and social ramifications, she says. For example, greater cooperation between an increasingly socioeconomically and ethnically diverse black community will help create political change in the face of contemporary racial inequality, as happened during the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

The increased stratification of the black community in large part came in the wake of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which helped give rise to the black middle class, Clerge says. At the same time, the foreign-born black population was also on the rise. In 1960, just 13.4 percent of black Americans were middle class, earning between $35,000 and $100,000 annually, according to a 2005 report by the U.S. Civil Rights Commission. By 2009, that number had grown to nearly 50 percent of the 14.7 million all-black households, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Clerge talked with Tufts Now about how demographic transformation in the African-American community has changed black identity in the last 40 years and what that means politically.

Tufts Now: How would you define black identity in America today?

Orly Clerge: The legacy of the transatlantic slave trade and colonialism has left an enduring mark on how race is defined today. Being of African origins automatically relegates blacks in America to a lower social status, which is facilitated by white racial attitudes and systematic policies barring their full participation in American society.

My research focuses on how everyday middle-class people manage and negotiate being black within these confining structural arrangements. I find that foreign- and native-born blacks define their black identities in various ways. Some are strongly attached to their black racial identity, while others participate in contextual and situational racial identity work, regardless of how the outside world perceives their skin color. Attachments to “blackness” are related to a host of competing identities such as gender, generation, age, sexuality, place of residence and exposure to non-blacks.

How does this affect the ability of black Americans to advance political and social change?

While various social movements organized and executed by blacks in the U.S. and abroad, such as Brazil and South Africa, have brought about significant ruptures in totalitarian white control, social change will only be systematic and effective if white Americans release their dominance over political and economic resources.

That said, blacks play a role in this process as well. Many members of the black community don’t have a fair shot in the U.S., and there is data that backs up that contention: lower homeownership rates, wages, educational attainment, marriage rates, even infant mortality—black women are twice as likely to have children who die in infancy than white women.

But if all blacks, including black immigrants and the black middle class, don’t see this inequality as a common struggle—as they did when overcoming segregation and discrimination during the civil rights movement—I don’t see that the necessary conditions will be in place to disrupt and transform the current racial and class inequalities.

You participated in protests following the shooting deaths by white police of unarmed black citizens Michael Brown in Ferguson and Eric Garner in New York. What did you find most significant in terms of these political actions?

What was interesting about these protests was that despite generational, economic, ethnic and educational differences, all classes of the black community came together to confront and denounce discrimination and brutality against their black children. We see the ways in which class and ethnic differences melt away in the face of common racial struggle. Many middle-class black families—foreign- and native-born—noted that their neighborhoods are just as hyper-policed as low-income black neighborhoods.

This common social problem gives rise to what political scientists call linked fate among a complex and sometimes divided black population. The shootings and ensuing protests compelled the black middle class to reflect on what it is doing—and what it can do—to ensure the inclusion and protection of their children.

You remind us that a black middle class has existed for centuries in America, but that the black middle class has always had a more tenuous economic footing than the white middle class.

Since the inception of the slavery-based economic system in the U.S., there have been classes of blacks, defined by skin color as well as the nature of the work they did—house slaves were considered to have a higher status than slaves who worked in the plantation fields, for example. In 1899, W.E.B. DuBois described the residential distribution and social standing of the black business-owning class in Philadelphia’s seventh ward.

But the black middle class has grown in unprecedented numbers since the civil rights movement in the 1960s, primarily through affirmative action and other government mandates to integrate predominantly white spaces and end the exclusion of blacks.

Yet the black middle class has been undermined through the recent national housing crisis, which ravaged many urban and suburban black communities. The famous saying “When America gets a cold, black America get the flu” hit home for the black middle class, whose homeownership, and therefore wealth, was undercut during the recent recession. By 2009 the median net worth of all black Americans—holdings such as real estate, stocks, business equity and vehicles, minus liabilities—was $11,000. The median net worth of white Americans, by contrast, was $141,009, according to the Pew Research Center.

The black middle class often works and lives in predominantly white spaces. Are they experiencing the same racial discrimination as blacks who are economically less well off?

Because of increased integration into white spaces, today’s black middle class experiences significant racial hostility and discrimination compared to their low-income counterparts. Before the mid-1960s, middle-class blacks were strategically segregated into black areas of cities and suburbs by larger white society through social intimidation tactics and violence.

The shift from overt to covert forms of racism means that black middle-class families are interacting with whites who may not be comfortable with them being in the same economic and social space as them. For my book project, I am exploring how they negotiate and manage being economically and physically integrated, yet racially excluded in diverse racial environments.

And what are you discovering?

While African Americans and black immigrants in the middle class spend a significant amount of time navigating racially problematic or hostile situations, black identity is not simply seen as an imposed racial category, but one that is positively internally defined and transmitted across generations. There were also various iterations of expressing blackness.

Respondents who had strong attachments to the being black in my study often noted that participating in what they saw as black life was a social, cultural, spiritual and economic resource that was valuable and central to who they were as people, a reality that is often overlooked in mass media and the social sciences.

Gail Bambrick can be reached at [email protected] .

Lights, Camera, Activism

A Life of ‘Empathy, Pragmatism, and Leadership’: Forrester Blanchard Washington

Reducing Inequitable Health Outcomes Requires Reducing Residential Segregation

Staff & Students

- Staff Email

- Semester Dates

- Parking (SOUPS)

- For Students

- Student Email

- SurreyLearn

Surrey English Blog

The blog for english literature and creative writing at the university of surrey, isolation insight: black identity in james baldwin.

This week’s blog is slightly different. I feel it would be wrong not to address the Black Lives Matter movement that has so rightly been occupying media attention over the past few weeks. Addressing and contextualising literature in the light of our current socio-political climate is an integral part of this blog. But even more so, I feel that it is essential to amplify and elevate black voices and stories, and I wish to use this platform to do so. Therefore, I have asked my fellow student from Surrey and good friend, Joel Weller, to write this week’s feature. Joel has written an incredibly insightful and compelling piece about black identity in James Baldwin’s literature. I’d like to thank Joel for his time, and hand over to him for this week’s instalment of Isolation Insight.

“Know whence you came. If you know whence you came, there is really no limit to where you can go.”

The Fire Next Time is a non-fiction book from American novelist James Baldwin. It contains two essays: ‘My Dungeon Shook — Letter to my Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation’ and ‘Down at the Cross — Letter from a Region of My Mind’. Published at the peak of the Civil Rights Movement, the two essays explore the varying nationwide response to racial discrimination and injustice throughout the United States of America. Baldwin himself was a writer and activist, his writing often concerned with matters of the sex, class and race distinctions that exist in Western society.

My name is Joel Weller, and I am an English Literature and Creative Writing graduate at The University of Surrey. For the past year, I have spent my time working as the Social Media Manager of the Stag Newspaper, and as a Part Time Officer of the Student Union’s Voice Zone. The current news cycle is a story that is familiar to both myself and thousands of others who are often racially profiled in the same way as I am. We are profiled in a way that race becomes a discriminating factor in our identities. Just acting as yourself and simply being, regardless of how you speak or present yourself, is not enough. The same was for George Floyd. When it came to the actual story of George Floyd’s death, I could not bring myself to watch the full footage. I could not watch a man die for something that should never deserve a death sentence. There have been various other viral videos, like the death of George Floyd, in which power has been exercised over black people. To me, having to deal with this, alongside the stress of a global pandemic has often become too much. Even after having acclimated to the quarantine, witnessing this kind of mindset – a mindset that favours white supremacy and targets an innocent demographic of people – is harder to forget. It is the reality for many, including myself.

I was surprised at the extent of the public reaction to videos such as these. It feels as if the floodgates of black trauma have opened, along with all its various intersections. The discourse on race has opened up. The way in which we uphold social imbalance as a normative thing, alongside the way in which historical racism and the Slave Trade has long been downplayed in Britain – all of it is now being re-evaluated. Recent events have forced us into a transitional state, with much of the nation having to face a new reality, as opposed to going back to ‘how things were’. Recent events, in which injustice have been so common yet so often overlooked, have proved that being vocal and getting involved is just as important as establishing good coping mechanisms and routine for the Coronavirus Lockdown.

Throughout the duration of the Black Lives Matter uprising and protests across the USA and UK, I have been listening to audiobook of James Baldwin’s ‘My Dungeon Shook — Letter to my Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation’. The UK protests have been to address the unjust treatment of Black people across the world, focusing in particular on the way in which Colonialism and British Black History is downplayed in school curriculums. Especially, it has been to show solidarity with the American Black Lives Matter movement and the need for justice for black identity. In the audiobook, James Baldwin addresses a nephew of his about the realities of dealing with one’s identity in a climate that imposes racism. Baldwin discusses the very concept of existing, and the way in which identity is shaped by other’s predisposed views of you. During our current period, it struck me as a powerful essay which highlights black identity struggles and the importance of establishing yourself and your pride before you face the world. Baldwin’s essay, especially the way that it is written, spoke to me. It was grounding. The essay navigates how one should deal with one’s own identity and place in the world, in a way that feels distinctly humanising. After seeing so many dismiss the biases and behaviours of people that enforce racism, and after seeing so many tragedies inflicted upon black people featured in the news, it was comforting.

Another Baldwin novel, If Beale Street Could Talk, deals with similar themes, in particular the current issue of police brutality. The 1974 novel depicts how authoritarian figures utilise racism to profile citizens and exercise their harsh, underlying prejudices. In recent news, I have often seen the mainstream media shift the narrative to negatively skew black people, reducing them to being “criminal” or “disruptive”. Set in 1970s Harlem, If Beale Street Could Talk follows Tish and Alonzo, childhood lovers who are separated by a system of oppression. Alonzo is arrested and imprisoned for a crime he doesn’t commit by a white police officer, leaving a pregnant Tish to fend for herself. To me, the novel depicts the harshness of reality for black people in America, exploring the social repercussions on yourself and your loved ones that come with ‘fitting a description’. The novel reflects on the process of profiling. I feel that, even now, the negativity of profiling seems like a norm in our society. It is often seen in the media and around us. Tish’s belief that something will change and her attempts to push on through her whole situation were familiar to me. I felt it echoed the same optimism for people like myself. Baldwin’s writing struck a chord with me, during a year in which acclimating to negativity has become the norm.

The quote at the beginning of this blog is from Baldwin. I believe that the sense of ‘knowing whence you came’ has given me more courage in my place and identity in the world. I now consider things such as the history of Windrush within this country and the culture that they brought and manifested within the UK as part of my identity. I consider the way in which the different accomplishments of black writers, artists, and musicians have birthed important cultural aspects within the UK and the world. Acknowledging these things and their significance in the world motivates to make a significant difference myself. I want to be empowered, as opposed to succumbing to the trauma brought by injustice and hatred. When listening and reading, it felt like Baldwin’s writing was directed at me. I saw similarities in his writing to my experiences. Even though I sometimes may be in environments where I feel, in myself, that there is a glaring difference between myself and others, the sense of knowing one’s self is grounding. It provides direction and strength, in a world where people have the capacity to subconsciously think less of you for your race, despite their public civility.

I believe that working towards a future that can move away from both overt and covert discrimination would be a worthy feat. But Baldwin’s literature has taught me that my identity and sense of self is key to reaching that future. That sense of self, the idea that you are who you are. Perhaps, because of your skin tone or based on how you talk, people may jump to conclusions, but Baldwin’s literature is reassuring in the idea that if that self-security is there, you will always have the upper hand.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Isolation Insight: Fight Club

Top 5 tips to kick-start your creative writing journey.

Accessibility | Contact the University | Privacy | Cookies | Disclaimer | Freedom of Information

© University of Surrey, Guildford, Surrey, GU2 7XH, United Kingdom. +44 (0)1483 300800

Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

1. personal identity and intra-racial connections.

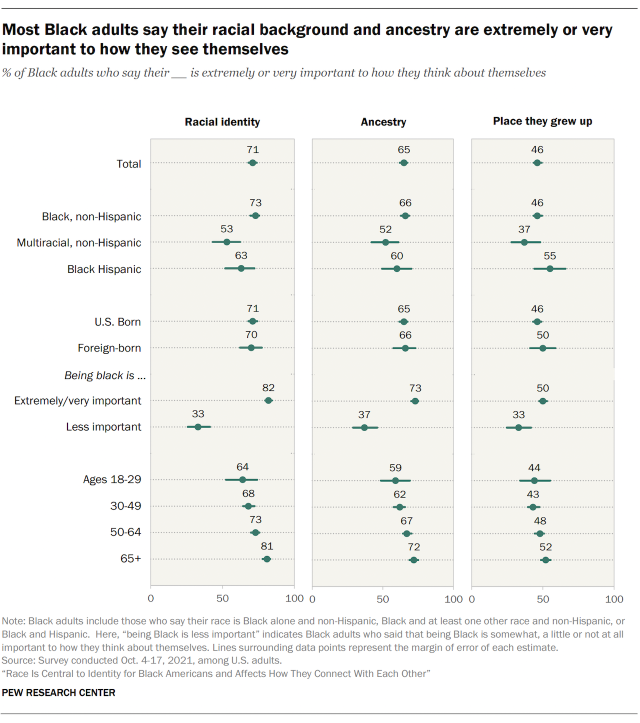

The personal identities of Black Americans are tied to many different characteristics, some of which are more important than others in shaping how they see themselves. In the new Pew Research Center survey, Black adults were asked about the importance of their racial background, ancestry, the place where they grew up, gender and sexuality to how they think about themselves. In addition to personal identity, the survey explored Black Americans’ views of how much they have in common with Black people who are U.S. born, immigrants, wealthy, poor and LGBTQ. It also asked Black Americans about how much what happens to Black people locally, nationally and globally affects what happens in their own lives.

The importance of race, ancestry and place to personal identity

Race and personal identity.

The majority of Black Americans identify as Black alone and non-Hispanic . However, 8% of Black adults identify as multiracial , that is Black and some other race, and 5% as Black Hispanic . Between 2000 and 2019, the share of Black Americans who identified as either multiracial or Black Hispanic had grown by roughly 145%. To capture this growing complexity in Black racial identity, Black adults were asked both a general question about the importance of their racial background and a more specific question about the importance of being Black .

About seven-in-ten Black Americans (71%) say their racial background is very or extremely important to how they think of themselves, according to the survey. While U.S.-born (71%) and immigrant (70%) Black Americans are equally likely to hold this view, there are differences among Black adults of different racial backgrounds and ethnicities. About seven-in-ten (73%) of those who identify solely as Black say their racial background is very or extremely important to how they think of themselves. Meanwhile, smaller shares of Black adults who identify as multiracial (53%) say the same.

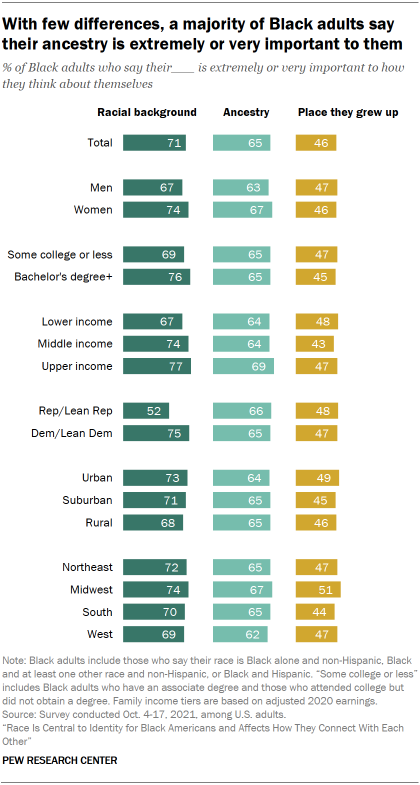

Gender, age, education, income and party are also key points of departure among Black adults when it comes to the importance of their racial backgrounds to their personal identity. Black women (74%) are more likely than Black men (67%) to say their race is an important part of how they think of themselves. When it comes to age groups, 81% of Black adults 65 and older say this, while 73% of those who are 50 to 64, 68% of those 30 to 49 and 64% of those under 30 say this.

There are also some differences by level of educational attainment. Black adults with at least a bachelor’s degree (76%) are more likely than those with lower levels of education (69%) to say that their racial identity is very or extremely important to them.

The importance of racial background to personal identity among Black Americans also differs by income. 2 Black adults with middle incomes (74%) and those with upper incomes (77%) are more likely than those with lower incomes (67%) to share this view.

Black Democrats and those who lean toward the Democratic Party (75%) are more likely than Black Republicans and Republican leaners (52%) to cite their racial identity as a very or extremely important part of how they think of themselves.

The survey also finds about three-quarters (76%) of Black adults say specifically that being Black is important to how they see themselves. This is a view widely shared across most major demographic subgroups of Black Americans, as clear majorities of each say being Black is a very or extremely important part of how they think of themselves.

Ancestry and personal identity

Like racial identity and the importance of being Black, the majority (65%) of Black Americans say their ancestry is an important part of how they think about themselves.

While U.S.-born (65%) and foreign-born (66%) Black adults hold similar views on this question, non-Hispanic Black adults (66%) are more likely than multiracial Black adults (52%) to say their ancestry is very or extremely important to their personal identity.

Black adults ages 65 and older (72%) are more likely than those who are 30 to 49 (62%) and slightly more likely than those under 30 (59%) to say that ancestry is very or extremely important to how they think about themselves. Meanwhile, the share of Black adults in the upper-income tier (69%) who hold this view is about the same as the shares of in the middle (64%) and lower tiers (64%). Looking at gender, nearly two-thirds of both Black women (67%) and Black men (63%) say that their ancestry is a very or extremely important part of their personal identity. There were no significant differences by education or by party affiliation among Black adults on this question.

The places where Black Americans grew up and personal identity

Black Americans were also asked how important the places where they grew up are to their personal identities. Nearly half of Black Americans (46%) say the location where they grew up is very or extremely important to how they think about themselves. Like racial identity and ancestry, this question differs somewhat for Black Americans of different ethnicities. Black Hispanic adults (55%) are more likely than multiracial Black adults (37%) to say that where they grew up is very or extremely important to their identity. Similar shares of Black Americans who were born in (46%) or outside (50%) of the United States hold this view.

There are only slight regional differences in the share of Black adults who say where they grew up is very or extremely important to their personal identity. While 51% of Black Americans who live in the Midwest say this, 47% of those living in the Northeast or West and 44% of those who live in the South say this. Black adults who live in urban (49%), suburban (45%) or rural (46%) areas are also about as likely to say that where they grew up is very or extremely important to their personal identity.

Black Americans differ only slightly by age in views on the importance of where they grew up. Black adults who are 65 and older (52%) are more likely than those 30 to 49 (43%) to say that the location where they grew up is a very or extremely important part of how they view themselves.

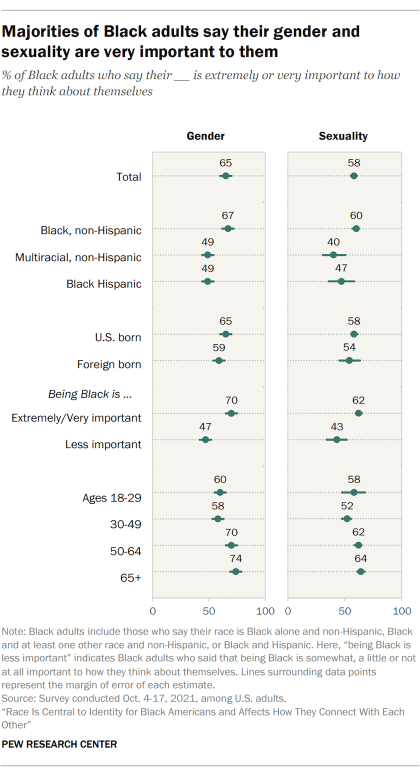

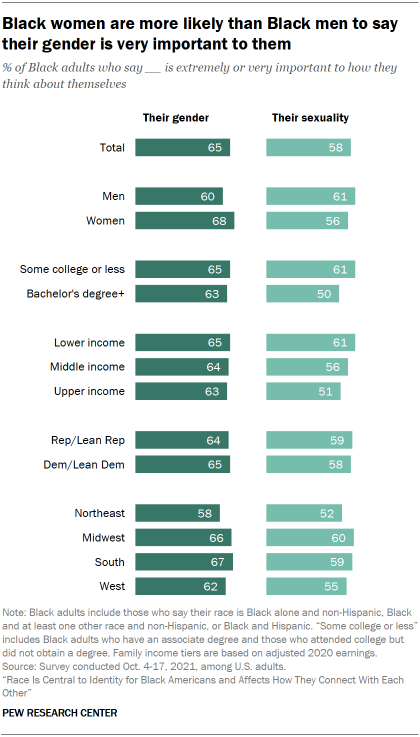

The importance of gender and sexuality to personal identity

Gender and sexuality are also important components of how Black Americans think about themselves.

Nearly two-thirds (65%) of Black adults say their gender is a very or extremely important part of how they think of themselves. Black women (68%) are more likely than Black men (60%) to say this, though clear majorities of each do.

Older Black Americans are more likely than younger ones to hold this view as well. Black adults who are 65 and older (74%) are more likely than those under 30 (60%) to say that their gender is a very or extremely important part of their identity.

Although there are no significant differences in the share who say this among U.S.-born (65%) or immigrant (59%) Black adults, there are differences by race and ethnicity. Non-Hispanic Black adults (67%) are more likely than multiracial Black adults (49%) or Black Hispanic adults (49%) to say their gender plays a significant role in how they think about themselves.

Black adults who say that being Black is a very or extremely important part of how they think about themselves (70%) are much more likely than those for whom being Black is less important (47%) to say their gender is an important part of their personal identity.

Relatedly, nearly six-in-ten Black Americans (58%) say their sexuality is very or extremely important to them. The majority of Black men (61%) and Black women (56%) share this view. Meanwhile, Black adults 65 and older (64%) and 50 to 64 (62%) are more likely than those 30 to 49 (51%) to say their sexuality is a very or extremely important part of how they think of themselves.

Six-in-ten non-Hispanic Black adults say their sexuality is a very or extremely important part of how they think about themselves, while 40% of multiracial Black adults and 47% of Black Hispanic adults to say this. Much like their views on gender, Black adults who say that being Black is very or extremely important to them (62%) are more likely than those for whom being Black is less important (43%) to say their sexuality is a significant part of their personal identity.

Black Americans who have at least a bachelor’s degree (50%) are less likely than those without one (61%) to say their sexuality is a very or extremely important part of how they think of themselves. And Black Americans with low incomes (61%) are more likely than those with higher incomes (51%) to hold this view.

Black Americans and connectedness to other Black people

Aside from questions about personal identity, Black Americans were asked about how much they have in common with different groups of Black people. They were also asked about how much what happens to other Black people in their local communities, in the United States and around the world affects what happens in their own lives.

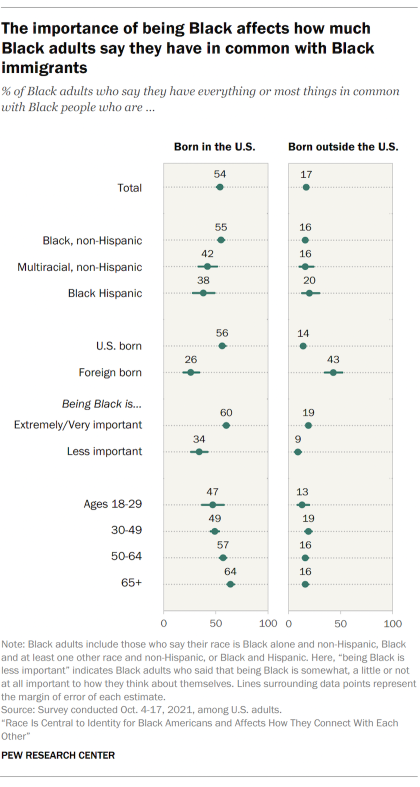

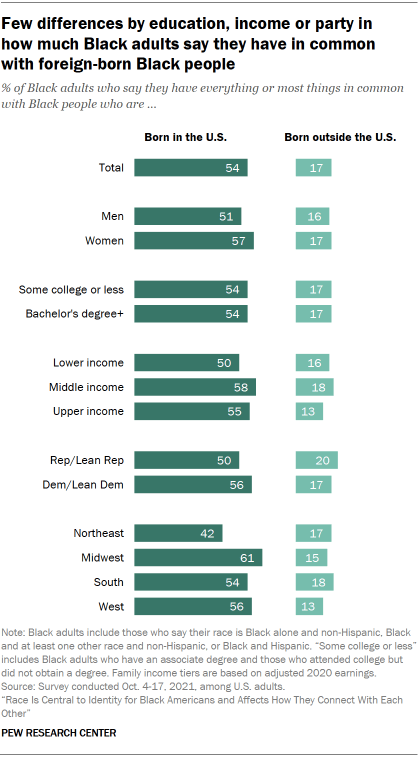

Commonality with U.S.-born Black people

The majority of Black adults say they have everything or most things in common with Black people born in the United States (54%). U.S.-born Black adults are more likely than immigrant Black adults to say they have everything or most things in common with Black people born in the U.S. 3 Over half (56%) of U.S.-born Black adults say they have everything or most things in common with other Black people born in the U.S, with about a quarter (23%) saying they have everything in common.

Conversely, only about a quarter (26%) of Black adults who were born outside the U.S. say they have everything or most things in common with Black people born in the U.S.; 43% say they only have some things in common and 31% say they have few things or nothing in common in Black people born in the U.S.

More than half of non-Hispanic Black adults (55%) say they have all or most things in common with U.S.-born Black people, including 23% who say they have everything in common. A smaller share of multiracial Black adults (42%) say they have everything or most things in common with U.S.-born Black people.

Black adults who say being Black is very or extremely important to them (60%) are more likely than those for whom being Black is less important (34%) to say they have everything or most things in common with Black people born in the United States.

Commonality with Black immigrants

Black Americans also shared how much they felt they had in common with Black people who were born outside of the United States, a group that makes up 12% of all Black Americans and is growing. The nation’s Black immigrant population is diverse, with just under half tracing their roots to the Caribbean and just under half to Africa .

Overall, just 17% of all Black adults say they have everything or most things in common with Black immigrants. Instead, a greater share said that they have some things in common with them (39%), rather than everything (5%) or most things (11%). In fact, about a quarter (24%) of all Black Americans say they have few things in common and 19% say they have nothing in common with Black immigrants.

Black immigrants (43%) are more likely than U.S.-born Black adults (14%) to say they have everything or most things in common with other Black immigrants. Meanwhile, 39% of U.S.-born Black adults say they have some things in common with Black immigrants, and nearly half (46%) say they have few things or nothing in common.

Black Americans also differ on this question along identity and ethnic lines. Black adults for whom being Black is a significant part of their identity (19%) are more likely than those for whom being Black is less important (9%) to say they have everything or most things in common with Black immigrants. Meanwhile, nearly half of Black Hispanic adults (47%) say they have some things in common with Black immigrants. This is more than the shares of non-Hispanic (39%) or multiracial (32%) Black adults saying the same. In fact, non-Hispanic (43%) and multiracial (47%) Black Americans are most likely to say that they have few things or nothing in common with Black immigrants. According to the survey, Black Hispanic adults (29%) are significantly more likely than non-Hispanic (7%) and multiracial (5%) Black adults to be immigrants themselves.

Black Americans’ sense of commonality with Black immigrants differs somewhat based on region, education and income. Though there are no significant differences in the shares who say they have everything or most things in common with Black immigrants, Black adults from the Midwest (50%) are more likely than those from the Northeast (38%) or South (42%) to say they have few things or nothing in common with Black immigrants.

When it comes to education and income, nearly half of Black adults with a bachelor’s degree (46%) say they have some things in common with Black immigrants, compared with 36% of Black adults with lower levels of education. Meanwhile, the share of Black adults in the upper-income tier (50%) who hold this view is higher than those in the middle- (40%) and lower-income tiers (36%).

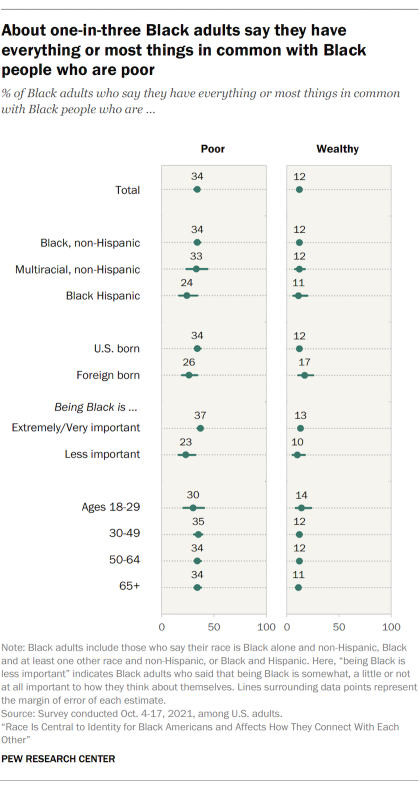

Commonality across social classes

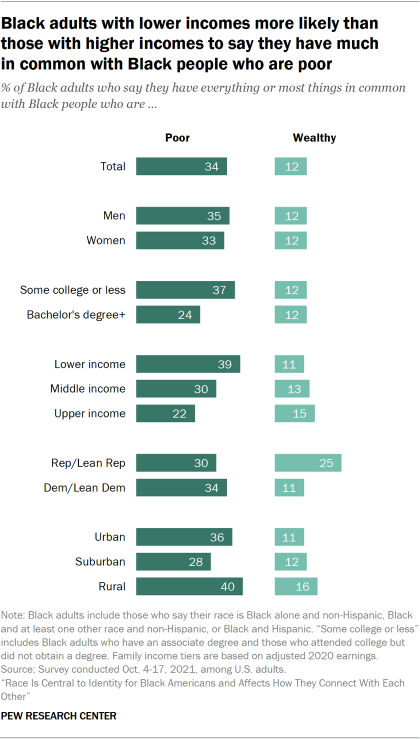

About one-in-three Black Americans say they have everything or most things in common with Black people who are poor (34%). Another 43% of Black Americans say they have some things in common with Black people who are poor, while 22% say they have few things or nothing in common.

Nearly four-in-ten Black adults with lower incomes (39%) say that they have everything or most things in common with Black people who are poor, more than the share of middle (30%) or upper (22%) earners who say the same. However, about half of middle- (46%) and upper-income earners (51%) say they have at least some things in common with Black people who are poor.

Likewise, Black adults who earned a bachelor’s degree (24%) are less likely than those with lower levels of education (37%) to say they have everything or most things in common with Black people who are poor. But half of Black college graduates (51%) say they have some things in common.

Black Americans who live in rural (40%) and urban (36%) areas are more likely than those who live in the suburbs (28%) to say they have everything or most things in common with Black people who are poor. However, like the patterns above, about half of suburban Black people (47%) say they have some things in common.

When asked how much they have in common with Black people who are wealthy, few Black Americans say they have everything or most things in common (12%) with the group. Many more say they have some things in common (36%). However, half of Black Americans (50%) say they have few things or nothing in common with Black people who are wealthy.

The shares of Black adults who say that they have few things or nothing in common with wealthy Black people vary based on education, income and community type. Only 12% of Black adults with or without a college degree say that they have much in common with Black people who are wealthy. Far more said the opposite. Black adults without a bachelor’s degree (53%) are more likely to say they have few things or nothing in common with Black people who are wealthy than Black adults with at least a bachelor’s degree (42%).

Few Black Americans with lower (11%), middle (13%) or even upper (15%) incomes indicate they have everything or most things in common with Black people who are wealthy. Conversely, about six-in-ten Black lower-income earners (59%) say they have few things or nothing in common with Black people who are wealthy. This makes them more likely than Black middle- (46%) and upper-income earners (32%) to say the same. Finally, Black adults who live in urban areas (54%) are more likely than those living in rural (46%) or suburban (48%) areas to say that they have few things or nothing in common with Black people who are wealthy.

Commonality with LGBTQ Black Americans

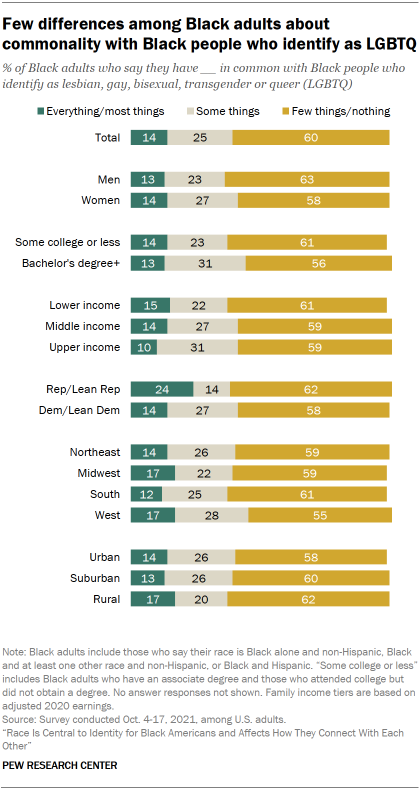

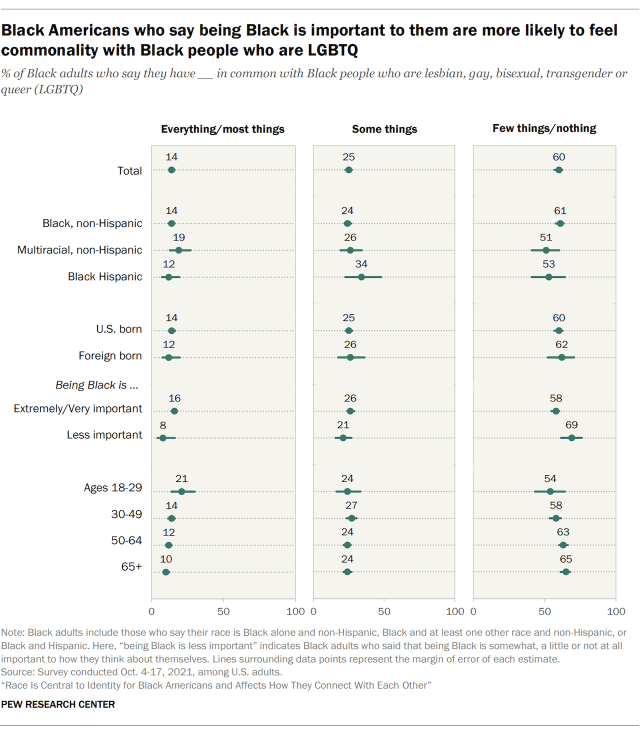

A small share (14%) of Black Americans say they have everything or most things in common with Black people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or queer (LGBTQ). The majority of Black Americans say they have few things or nothing in common (60%) with LGBTQ Black people.

Black Americans’ sense of commonality with Black people who have LGBTQ identities vary by age, gender, ethnicity, education, income and party. Black adults who are under 30 (21%) and those ages 30 to 49 (14%) are more likely than those 65 and older (10%) to say they have everything or most things in common with Black people who have LGBTQ identities.

Conversely, Black adults who are 50 to 64 (63%) and 65 and older (65%) are more likely than those who are 30 to 49 (58%) to say that they have few things or nothing in common with Black people who identify as LGBTQ.

Equal shares of Black men (13%) and women (14%) say they have all or most things in common with Black people who identify as LGBTQ. However, Black men (42%) are more likely than Black women (34%) to say they have nothing in common. Small shares of non-Hispanic Black adults (14%), multiracial Black adults (19%), and Black Hispanic adults (12%) say they have all or most things in common with Black people who are LGBTQ. However, non-Hispanic Black adults (38%) are more likely than Black Hispanic adults (26%) to say that they have nothing in common.

Four-in-ten Black adults who have not attained a bachelor’s degree (40%) say that they have nothing in common with Black people who are LGBTQ, compared with 28% of Black college graduates. Similarly, Black adults in the lower-income tier (40%) are more likely than those in the upper-income tier (31%) to hold this view. Among Black Republicans and those who lean toward the Republican Party, 44% say they have nothing in common with Black people who have LGBTQ identities – higher than the share of Black Democrats and leaners (35%) who say the same.

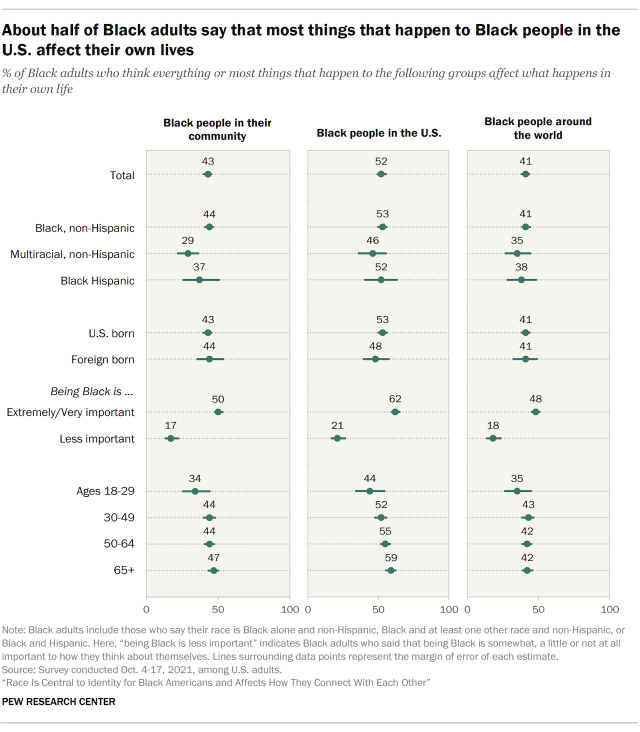

Intra-racial connections locally, nationally and globally

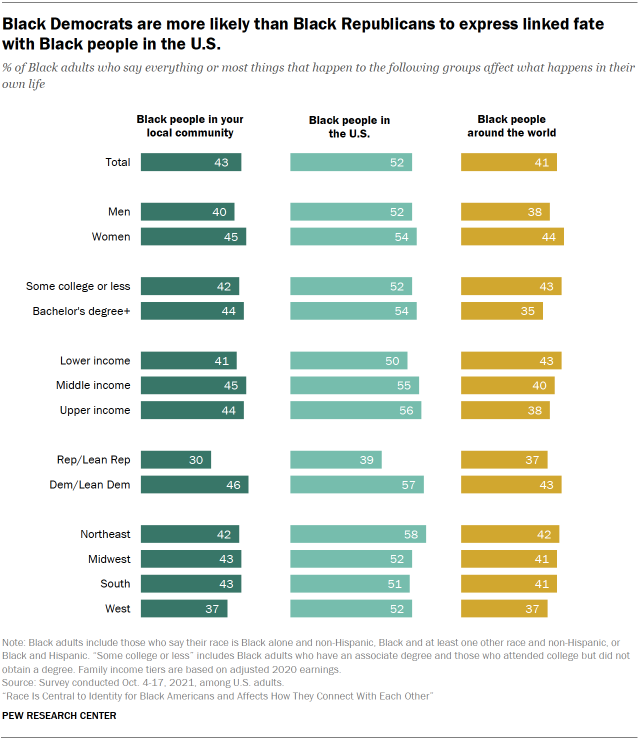

While many Black adults feel a sense of connection and common fate with other Black people, nearly as many do not. Overall, they were most likely to say that everything or most things that happen to Black people in the United States (52%), rather than those in their local communities (43%) or around the world (41%), affect what happens in their own lives.

Local intra-racial connections

Similar patterns hold when Black Americans were asked about how connected they felt to Black people in their local communities. Non-Hispanic Black adults (44%) are more likely than multiracial Black adults (29%) to say that what happens to Black people in their local communities affects what happens in their own lives. And Black adults who say that being Black is a very or extremely important part of their identity (50%) are far more likely than those for whom being Black is less important (17%) to hold this view.

U.S.-born (43%) and immigrant (44%) Black adults are about as likely to say everything or most things that happen to Black people in their local areas impact their own lives. Black adults also do not differ by community type on this question. Those who live in urban (42%), suburban (41%) or rural (47%) areas are equally likely to say everything or most things that happen to Black people in their local communities affect their lives.

While nearly half of Black Americans ages 30 to 49 (44%), 50 to 64 (44%) and 65 and older (47%) say that everything or most things that happen to Black people in their communities impact them, Black young adults (34%) stand apart as being less likely than those 65 and older to say this. In fact, Black adults under 30 are more likely than all other age groups to say few things or nothing that happens to Black people in their local communities impacts their own lives. When it comes to education and income, Black Americans’ views on this question are mixed. While 44% of Black college graduates say everything or most things that happen to Black people in their local communities impact their own lives, a similar share (42%) say that only some things affect them. Among Black adults without a college degree, 42% say everything or most things that happen to Black people in their communities affect them, and 32% say only some things would affect them.