Shortform Books

The World's Best Book Summaries

The Evolution of the English Language: A Brief History

This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Mother Tongue" by Bill Bryson. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What are the origins of English? What are the key events in the evolution of the English language that were most instrumental in shaping it into the version we speak and write today?

English, as we know it today, is very different from its original Anglo-Saxon version. To understand how this came to be, we need to understand the evolution of the English language and the processes by which it transformed into English as we know it today.

Keep reading to learn about the evolution of the English language.

Unfolding the Evolution of English Through Time

The evolution of the English language happened in three phases: 1) the Anglo-Saxon phase, 2) the Medieval or the Middle English phase, 3) and the Modern English phase. Each phase is characterized by distinct influences and their resulting changes to the language’s vocabulary, syntax, grammar, and pronunciation.

1) The Anglo-Saxon Phase

The first evolutionary for the English language began when Germanic peoples known as the Angles and Saxons, hailing from what is now Northern Germany, began migrating to and conquering the Roman province of Britannia in the mid-5th century CE.

These Angles and Saxons brought their North Sea Germanic dialects to their new home . The linguistic linkages between English and the dialects spoken in Northern Germany can still be detected today. They even gave their name to the new country—Angle-land, or England.

Different invading tribes settled in different regions of what is now England, lending their own unique linguistic stamp to different regions of the country. The echoes of this historical process of localized linguistic development can even be seen in the United States today, as different regions of North America were, in their turn, settled by people from different regions of the British Isles.

Old English

The proto-English spoken by the Angles and Saxons morphed over time into Old English . Christian missionaries arrived in 597 and began the process of Christianizing the population (or, at least, the political elite of the country). The rise of a new priestly class that needed to be able to read and write in order to understand and teach the Bible aided in the spread of literacy and helped give Old English a written form.

Old English gradually supplanted the old Latin and Celtic influences in England. These latter linguistic traditions have left very little trace in modern England—astonishingly few English personal or place-names today have Latin or Celtic antecedents.

Old English is largely unintelligible to speakers and readers of Modern English . We can observe this by comparing lines of text. The Old English “Fæder ure şu şe eart on heofonum, si şin nama gehalgod” translates to the Modern English “Our father which art in heaven, hallowed be thy name”—the opening lines of the Lord’s Prayer.

Despite the seemingly alien nature of Old English, it does have some similarities of structure and syntax to the language we speak and write today. Although influences from subsequent linguistic waves over the British Isles displaced much of the Old English language (only about 1 percent of our vocabulary can be traced to it) some of our most fundamental words owe their origins to Old English , particularly words related to family— man , wife , child , brother , and sister , to name a few.

There was a great outpouring of Old English literature during the Anglo-Saxon period of English history. The Venerable Bede, a Northumbrian monk, was the first English historian and chronicler; Caedmon was the first English poet; and Alcuin was the first English scholar of international reputation, a leading figure at the court of Charlemagne. In addition to these, we have a rich trove of Old English letters, charters, and legal texts that point to the vibrancy of the language. Works like Beowulf and Caedmon’s Hymn are the starting points of English literature.

The Vikings and the Scandinavian Influence

From the 8th to the 10th centuries CE, the British Isles suffered a new wave of invasion and settlement . This time, the invaders were Vikings from what are now the Scandinavian countries of Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. Scholars are unclear as to why these invasions started when they did, but they left a profound and lasting influence on the English language. A political settlement with the Anglo-Saxon kings in the mid-9th century granted the Vikings a specified area in Northeastern England in which they could live and settle. This area was known as the Danelaw.

The linguistic stamp of the Danelaw can still be observed in England today, as the Viking invaders infused Old English with new loanwords taken from their Old Norse languages. Important words like husband , sky , and leg can be dated back to the Viking Age.

The importation of Scandinavian words also made the Old English language more flexible , because these words often supplemented words that already existed in Old English instead of completely replacing them. This gave Old English a host of synonyms and doublets that allowed different words to be used to express slightly different ideas. Old English also absorbed syntax and grammatical structure from Old Norse, a testament to the language’s fluidity, even at this early stage in its development.

2) The Middle English Phase

The second phase in the evolution of the English language started roughly at the intersection of the 11th and the 12th century, when the Norman king William I conquered England and displaced the reigning Anglo-Saxon ruling elite. The Normans were people from Normandy, in Northern France, themselves descended from Viking ancestors. The Norman Conquest, unlike the earlier Saxon and Viking invasions, was not a mass migration. Instead, it was a replacement of one set of elites by another—the Old English nobility was dispossessed and replaced by a new Anglo-Norman governing class, but life and language continued on normally for the vast majority of the English population.

Norman French, not English, was the language of the ruling elite in England for centuries after the Norman Conquest—after 1066, no English monarchs spoke English as their primary language until Henry IV’s coronation in 1399. The words imported into today’s English from Norman French distinctly show this social/linguistic split. It is no coincidence that the roughly 10,000 words that owe their origins to the Norman Conquest are disproportionately concentrated in subject matters like court ( duke , baron ) and jurisprudence ( jury , felony ), while words like baker and miller having to do with everyday life or ordinary trades are disproportionately Anglo-Saxon in origin.

Largely left to its own devices, English developed organically during the Middle Ages. The ruling Anglo-Norman elite took little notice of developments in English, because it was the language of commoners.

This was the era when English developed many of its more recognizable features, like uninflected verbs with stable consonants (inflection is a change in the form of a word, often the ending, to reflect different contexts like gender, mood, and tense). In English, however, verbs and other parts of speech tend to be the same regardless of these different contexts. As we shall see later, such developments were to prove greatly advantageous to English as it spread throughout the world.

Medieval Developments

By the mid-14th century, English had reasserted itself as a language of government and law , likely due to the fact that the political links between England and France were severed over the course of the centuries. Moreover, we see a shift in the character of written English—Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales is a clear departure from Old English. It is written in what we call Middle English, a form far more recognizable to modern readers.

The biggest part of this change was the loss of inflection and gender, but other forms of simplification and unification were taking place . For example, Old English had six noun endings to denote a plural, but only two survived into Middle and Modern English (“-s” as in hands and “-en” as in oxen , with the latter being extremely rare and used only for a handful of words). Verb forms were also being reduced, with fewer options to denote the tense of a word.

Although Medieval English dialects could vary widely even across short distances, the language was becoming more standardized in the Late Middle Ages . This had much to do with the influence of London. The relatively simple grammatical structure of the English dialect in this city as compared to other dialects, its large population, its role as the national seat of government and commerce, and its proximity to the universities of Oxford and Cambridge gave London English advantages that ensured its ultimate triumph over other, local forms of the language.

This was a long and uneven historical process—it didn’t happen all at once and it didn’t happen at the same speed everywhere. Vestigial irregular verbs (those whose conjugation does not follow the usual pattern remain in the language like bear/bore and wear/wore . In addition, there are still parts of South Yorkshire in the north of England where archaic pronouns like thee and thou survive to this day. Lastly, non-English Celtic languages for a long time remained the primary mode of speech in the fringes of the British Isles, like Western Ireland, Wales, and Highland Scotland.

3) The Modern English Phase

The Modern English phase extends from the 16th century to the present day. Perhaps the biggest change during this phase was the culmination of the revolution of the phonology of English (the Great Vowel Shift), running roughly from 1400-1600 CE, during which English speakers began pushing vowels closer to the front of their mouths. The word life , for example, was pronounced lafe in Shakespeare’s time, with the vowel lodged further back in the throat.

At this time, English began to be regarded for its potential as a language of literature. No writer took greater advantage of the incredible flexibility and richness of the English language than Shakespeare . The Bard of Avon alone added some 2,000 words to the language, such as mimic , bedroom , lackluster , hobnob . He also introduced a host of new phrases we still use today, like “one fell swoop” and “in my mind’s eye.” Shakespeare greatly elevated and exalted the English language.

For much of the history of the evolution of the English language, however, words defied standard spelling, with even Shakespeare offering a bewildering array of different and inconsistent spellings for the same words throughout his works. The first steps toward standardization only began with the invention of the printing press in the 15th century and the gradual spread of written works (and thus, literacy) throughout England.

By 1640, there were over 20,000 titles available in English, more than there had ever been. As printed works produced by London printers began to spread across the country, local London spelling conventions gradually began to supplant local variations. What this also meant was that old spellings became fixed just as many word pronunciations were shifting because of the Great Vowel Shift. Our inheritance is a written language with many words spelled the way they were pronounced 400 years ago. As a result, English spellings often bedevil non-native speakers, as well as those who’ve spoken the language their whole lives . Pronunciation and spelling are frequently divergent. To take just one example, the sh sound can be spelled sh as in mash ; ti as in ration ; or ss as in session . The troublesome orthography (the set of conventions for writing) of English can be seen in words like debt , know , knead , and colonel , with their silent letters, as well as their hidden, but pronounced letters.

Grammar Police

The organic and sometimes haphazard evolution of English has led some figures to call for the establishment of a central body to create rules about and regulate the usage of the language. Such bodies do exist in other languages. The Académie Française, founded by Cardinal Richelieu in the 17th century, still serves as the official body regulating proper usage of the French language (how seriously its rules are taken by actual Francophones is another matter). English men of letters like John Dryden, Daniel Defoe, and Jonathan Swift believed that English might benefit from the establishment of such an academy.

But this idea was also greeted with hostility by opponents like the great lexicographer Samuel Johnson, US President Thomas Jefferson, and theologian Joseph Priestley, all of whom argued that an “official” authority on English would inhibit the evolution of the language, exert an overly conservative and stodgy influence on usage, and freeze the language at a particular point in time . Ultimately, no “English Academy” was established.

Many celebrate this outcome as a positive development for the language, one that freed it from being saddled with a set of cumbersome and inflexible rules imposed by an elitist and out-of-touch body. In the absence of an official organization, English has relied upon informal and self-appointed grammarians and lexicographers to define its rules.

These figures write books and give lectures on proper or standard usage of the language, but they are usually ignored by the vast majority of the population. Even high-profile elites in the worlds of academia, politics, and culture frequently misuse words (confusing flout with flaunt , as US President Jimmy Carter once did in a televised address) or use technically improper forms of the language (splitting an infinitive as in the Star Trek phrase “to boldly go” instead of the more proper “to go boldly”).

Many of the rules of English we observe today are the arbitrary creations of self-appointed authorities who lived centuries ago and offered little or no rationale for the rules they promulgated . The 18th-century English clergyman and amateur grammarian Robert Lowth is a good example of such a figure. It is to Lowth that we owe many of the arbitrary rules of usage that we see in style guides and textbooks all over the English-speaking world such as not ending a sentence with a preposition, the prohibition against double negatives like “I don’t want no potatoes,” and the subtle, but different meanings of between and among .

Other grammar police of the time and of later ages declared that it was unacceptable to combine Greek and Latin root words into a single new word, and so railed against words like petroleum (combining the Latin petro and the Greek oleum ). These deeply silly and pretentious dictums rested upon no logic or reason and ignored centuries of real-world use in England and her colonies by both ordinary people and the great English writers of the time.

The Creation of Words

We’ve explored the historical forces that shaped the overall structure of the English language. But in our effort to understand how English became the language we speak and write today, we need to delve deeper and understand the processes by which individual words themselves are formed. There are six primary ways words have entered the English language.

- Words are born through accident . Many English words are the product of simple mispronunciation, misspelling, mishearing, or misuse. For instance, sweetheart was once sweetard , but evolved into its present form through persistent misuse. In other cases, words are created through backfilling from plural to singular. For example, the word pease was once the singular form of pea. The word pea didn’t exist, but people mistakenly thought that pease was plural, so pea was created to correct this supposed error.

- Words are adopted from other languages, as we saw with loanwords from Old Norse and Norman French. English has proven to be a remarkably welcome home for “refugee” words. Even in Shakespeare’s time, English had already borrowed words from over 50 languages, a remarkable feat considering the difficulties of travel and communication in the pre-modern era. Indeed, loan words and phrases from other languages live on in English long after they have gone extinct in their native tongues (like nome de plume or double entendres , both of which no longer exist in their original French). Some words like breeze (derived from the Spanish briza ) have become so thoroughly anglicized that we forget they are actually derived from foreign sources.

- Words are invented from nothing, with no known explanation as to their origin. We’ve already seen how Shakespeare single-handedly introduced hundreds of words into the language. Even as ubiquitous a word as dog only began to appear in the late Middle Ages; before this, the word for this animal was hound . Other times, new words come into existence as a by-product of new technologies—in our time, the internet has spawned its own mini-language.

- Existing words shift their meaning over time, even if they retain their spelling and pronunciation. Some words have undergone remarkable changes in definition over the centuries, even coming to mean the exact opposite of what they originally did. This latter phenomenon is called catachresis. Since Chaucer’s time, the word nice has meant everything from foolish to strange to wanton to lascivious. Only in the mid-18th century did it acquire something akin to its present meaning. The word has changed so much that it is sometimes impossible for historians and linguists to divine its precise meaning in antiquated texts.

- Existing words are altered or modified . The rich tapestry of prefixes and suffixes in English gives it a flexibility that makes it easy to modify words into different parts of speech or give them a different tense. An adjective like diverse can easily become a verb like diversify or a noun like diversification . But this leads to the same double-edged sword we’ve seen with English before—its flexibility simultaneously makes it adaptable to non-native speakers, while populating it with a maddening array of exceptions to the rules and irregular forms. For instance, there are eight separate prefixes just to express negation alone (such as non- , ir- , and in- ), but not all words that begin this way are negatives, as anyone familiar with the shared and highly confusing meanings of flammable and inflammable can attest.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of bill bryson's "the mother tongue" at shortform ..

Here's what you'll find in our full The Mother Tongue summary :

- How English became a global language

- How the invention of the printing press led to standardization of written English

- Why English dictionaries are the most comprehensive found in any language

- ← Homo Deus: Meaning and Implications

- Why Having Too Many Options Is a Bad Thing →

Darya Sinusoid

Darya’s love for reading started with fantasy novels (The LOTR trilogy is still her all-time-favorite). Growing up, however, she found herself transitioning to non-fiction, psychological, and self-help books. She has a degree in Psychology and a deep passion for the subject. She likes reading research-informed books that distill the workings of the human brain/mind/consciousness and thinking of ways to apply the insights to her own life. Some of her favorites include Thinking, Fast and Slow, How We Decide, and The Wisdom of the Enneagram.

You May Also Like

How to Get People to Like You: Six Simple Steps

Arlie Hochschild: Strangers in Their Own Land Theories

The Four Stages of an Industrial Revolution

Odysseus Moon Landing & the Future of Space Exploration

System Thinking: Meaning and Purpose

How to Work With a Blue Personality Type

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

A Brief History of the English Language: From Old English to Modern Days

Join us on a journey through the centuries as we trace the evolution of English from the Old and Middle periods to modern times.

What Is the English Language, and Where Did It Come From?

The different periods of the english language, the bottom line.

Today, English is one of the most common languages in the world, spoken by around 1.5 billion people globally. It is the official language of many countries, including the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

English is also the lingua franca of international business and academia and is one of the six official languages of the United Nations.

Despite its widespread use, English is not without its challenges. Because it has borrowed words from so many other languages, it can be difficult to know how to spell or pronounce certain words. And, because there are so many different dialects of English, it can be hard to understand someone from a different region.

But, overall, English is a rich and flexible language that has adapted to the needs of a rapidly changing world. It is truly a global, dominant language – and one that shows no signs of slowing down. Join us as we guide you through the history of the English language.

Discover how to learn words 3x faster

Learn English with Langster

The English language is a West Germanic language that originated in England. It is the third most spoken language in the world after Mandarin Chinese and Spanish. English has been influenced by a number of other languages over the centuries, including Old Norse, Latin, French, and Dutch.

The earliest forms of English were spoken by the Anglo-Saxons, who settled in England in the 5th century. The Anglo-Saxons were a mix of Germanic tribes from Scandinavia and Germany. They brought with them their own language, which was called Old English.

The English language has gone through distinct periods throughout its history. Different aspects of the language have changed throughout time, such as grammar, vocabulary, spelling , etc.

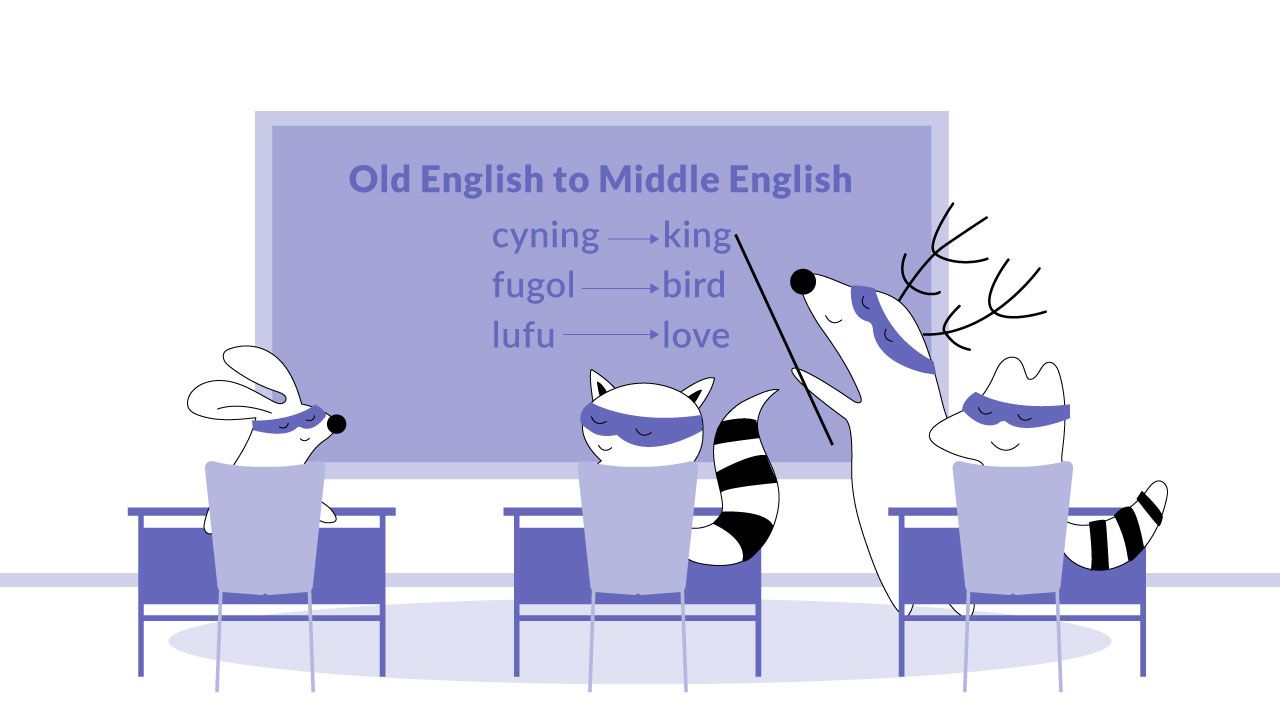

The Old English period (5th-11th centuries), Middle English period (11th-15th centuries), and Modern English period (16th century to present) are the three main divisions in the history of the English language.

Let's take a closer look at each one:

Old English Period (500-1100)

The Old English period began in 449 AD with the arrival of three Germanic tribes from the Continent: the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. They settled in the south and east of Britain, which was then inhabited by the Celts. The Anglo-Saxons had their own language, called Old English, which was spoken from around the 5th century to the 11th century.

Old English was a Germanic language, and as such, it was very different from the Celtic languages spoken by the Britons. It was also a very different language from the English we speak today. It was a highly inflected language, meaning that words could change their form depending on how they were being used in a sentence.

There are four known dialects of the Old English language:

- Northumbrian in northern England and southeastern Scotland,

- Mercian in central England,

- Kentish in southeastern England,

- West Saxon in southern and southwestern England.

Old English grammar also had a complex system, with five main cases (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, instrumental), three genders (masculine, feminine, and neuter), and two numbers (singular and plural).

The Anglo-Saxons also had their own alphabet, which was known as the futhorc . The futhorc consisted of 24 letters, most of which were named after rune symbols. However, they also borrowed the Roman alphabet and eventually started using that instead.

The vocabulary was also quite different, with many words being borrowed from other languages such as Latin, French, and Old Norse. The first account of Anglo-Saxon England ever written is from 731 AD – a document known as the Venerable Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People , which remains the single most valuable source from this period.

Another one of the most famous examples of Old English literature is the epic poem Beowulf , which was written sometime between the 8th and 11th centuries. By the end of the Old English period at the close of the 11th century, West Saxon dominated, resulting in most of the surviving documents from this period being written in the West Saxon dialect.

The Old English period was a time of great change for Britain. In 1066, the Normans invaded England and conquered the Anglo-Saxons. The Normans were originally Viking settlers from Scandinavia who had settled in France in the 10th century. They spoke a form of French, which was the language of the ruling class in England after the Norman Conquest.

The Old English period came to an end in 1066 with the Norman Conquest. However, Old English continued to be spoken in some parts of England until the 12th century. After that, it was replaced by Middle English.

Middle English Period (1100-1500)

The second stage of the English language is known as the Middle English period , which was spoken from around the 12th century to the late 15th century. As mentioned above, Middle English emerged after the Norman Conquest of 1066, when the Normans conquered England.

As a result of the Norman Conquest, French became the language of the ruling class, while English was spoken by the lower classes. This led to a number of changes in the English language, including a reduction in the number of inflections and grammatical rules.

Middle English is often divided into two periods: Early Middle English (11th-13th centuries) and Late Middle English (14th-15th centuries).

Early Middle English (1100-1300)

The Early Middle English period began in 1066 with the Norman Conquest and was greatly influenced by French, as the Normans brought with them many French words that began to replace their Old English equivalents. This process is known as Normanisation.

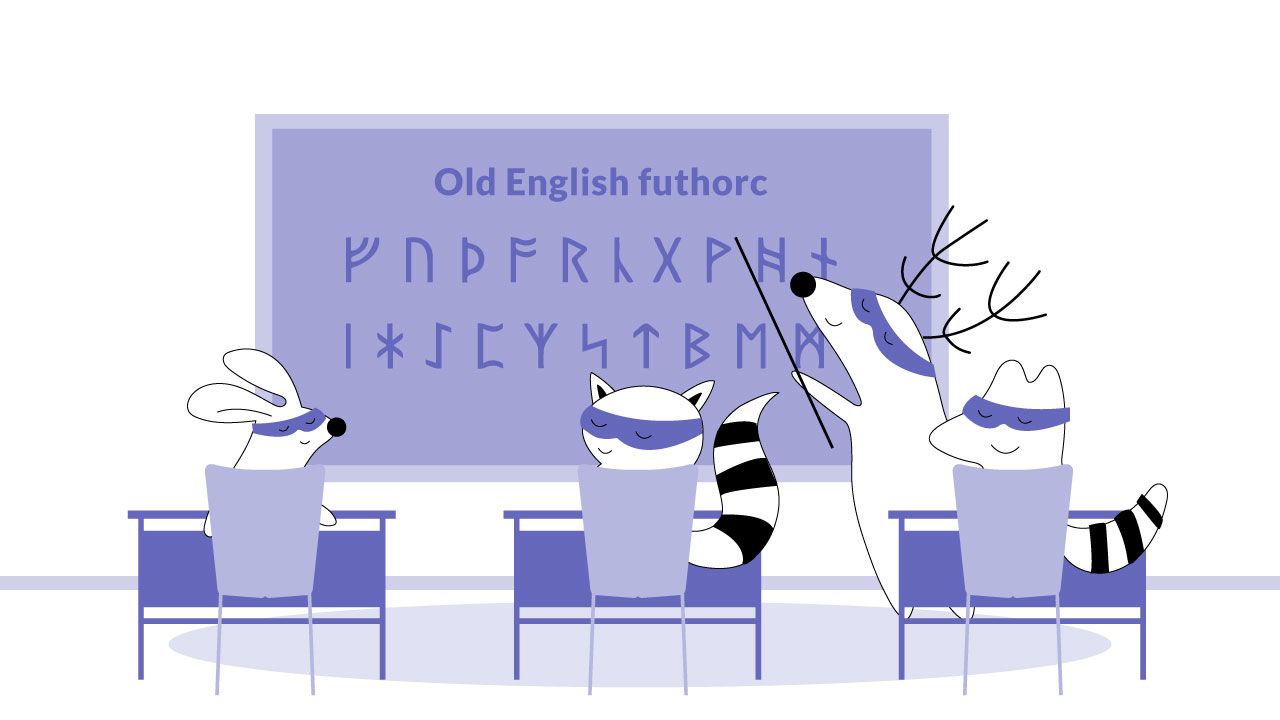

One of the most noticeable changes was in the vocabulary of law and government. Many Old English words related to these concepts were replaced by their French equivalents. For example, the Old English word for a king was cyning or cyng , which was replaced by the Norman word we use today, king .

The Norman Conquest also affected the grammar of Old English. The inflectional system began to break down, and words started to lose their endings. This Scandinavian influence made the English vocabulary simpler and more regular.

Late Middle English (1300-1500)

The Late Middle English period began in the 14th century and lasted until the 15th century. During this time, the English language was further influenced by French.

However, the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453) between England and France meant that English was used more and more in official documents. This helped to standardize the language and make it more uniform.

One of the most famous examples of Middle English literature is The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer, which was written in the late 14th century. Chaucer was the first major writer in English, and he e helped to standardize the language even further. For this reason, Middle English is also frequently referred to as Chaucerian English.

French influence can also be seen in the vocabulary, with many French loanwords being introduced into English during this time. Middle English was also influenced by the introduction of Christianity, with many religious terms being borrowed from Latin.

Modern English Period (1500-present)

After Old and Middle English comes the third stage of the English language, known as Modern English , which began in the 16th century and continues to the present day.

The Early Modern English period, or Early New English, emerged after the introduction of the printing press in England in 1476, which meant that books could be mass-produced, and more people learned to read and write. As a result, the standardization of English continued.

The Renaissance (14th-17th centuries) saw a rediscovery of classical learning, which had a significant impact on English literature. During this time, the English language also borrowed many Greek and Latin words. The first English dictionary , A Table Alphabeticall of Hard Words , was published in 1604.

The King James Bible , which was first published in 1611, also had a significant impact on the development of Early Modern English. The Bible was translated into English from Latin and Greek, introducing many new words into the language.

The rise of the British Empire (16th-20th centuries) also had a significant impact on the English language. English became the language of commerce, science, and politics, and was spread around the world by British colonists. This led to the development of many different varieties of English, known as dialects.

One of the most famous examples of Early Modern English literature is William Shakespeare's play Romeo and Juliet , which was first performed in 1597. To this day, William Shakespeare is considered the greatest writer in the English language.

The final stage of the English language is known as Modern English , which has been spoken from around the 19th century to the present day. Modern English has its roots in Early Modern English, but it has undergone several changes since then.

The most significant change occurred in the 20th century, with the introduction of mass media and technology. For example, new words have been created to keep up with changing technology, and old words have fallen out of use. However, the core grammar and vocabulary of the language have remained relatively stable.

Today, English is spoken by an estimated 1.5 billion people around the world, making it one of the most widely spoken languages in the world. It is the official language of many countries, including the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia. English is also the language of international communication and is used in business, education, and tourism.

English is a fascinating language that has evolved over the centuries, and today it is one of the most commonly spoken languages in the world. The English language has its roots in Anglo-Saxon, a West Germanic language spoken by the Anglo-Saxons who settled in Britain in the 5th century.

The earliest form of English was known as Old English, which was spoken until around the 11th century. Middle English emerged after the Norman Conquest of 1066, and it was spoken until the late 15th century. Modern English began to develop in the 16th century, and it has continued to evolve since then.

If you want to expand your English vocabulary with new, relevant words, make sure to download our Langster app , and learn English with stories! Have fun!

Ellis is a seasoned polyglot and one of the creative minds behind Langster Blog, where she shares effective language learning strategies and insights from her own journey mastering the four languages. Ellis strives to empower learners globally to embrace new languages with confidence and curiosity. Off the blog, she immerses herself in exploring diverse cultures through cinema and contemporary fiction, further fueling her passion for language and connection.

Learn with Langster

Learning English as a Second Language: Why and How?

How to Improve English Writing Skills: 10 Practical Tips

Business English: Vocabulary, Culture, Tips

More Langster

- Why Stories?

- For Educators

- French A1 Grammar

- French A2 Grammar

- German A1 Grammar

- German A2 Grammar

- Spanish Grammar

- English Grammar

Introductory essay

Written by the educator who created What Makes Us Human?, a brief look at the key facts, tough questions and big ideas in his field. Begin this TED Study with a fascinating read that gives context and clarity to the material.

As a biological anthropologist, I never liked drawing sharp distinctions between human and non-human. Such boundaries make little evolutionary sense, as they ignore or grossly underestimate what we humans have in common with our ancestors and other primates. What's more, it's impossible to make sharp distinctions between human and non-human in the paleoanthropological record. Even with a time machine, we couldn't go back to identify one generation of humans and say that the previous generation contained none: one's biological parents, by definition, must be in the same species as their offspring. This notion of continuity is inherent to most evolutionary perspectives and it's reflected in the similarities (homologies) shared among very different species. As a result, I've always been more interested in what makes us similar to, not different from, non-humans.

Evolutionary research has clearly revealed that we share great biological continuity with others in the animal kingdom. Yet humans are truly unique in ways that have not only shaped our own evolution, but have altered the entire planet. Despite great continuity and similarity with our fellow primates, our biocultural evolution has produced significant, profound discontinuities in how we interact with each other and in our environment, where no precedent exists in other animals. Although we share similar underlying evolved traits with other species, we also display uses of those traits that are so novel and extraordinary that they often make us forget about our commonalities. Preparing a twig to fish for termites may seem comparable to preparing a stone to produce a sharp flake—but landing on the moon and being able to return to tell the story is truly out of this non-human world.

Humans are the sole hominin species in existence today. Thus, it's easier than it would have been in the ancient past to distinguish ourselves from our closest living relatives in the animal kingdom. Primatologists such as Jane Goodall and Frans de Waal, however, continue to clarify why the lines dividing human from non-human aren't as distinct as we might think. Goodall's classic observations of chimpanzee behaviors like tool use, warfare and even cannibalism demolished once-cherished views of what separates us from other primates. de Waal has done exceptional work illustrating some continuity in reciprocity and fairness, and in empathy and compassion, with other species. With evolution, it seems, we are always standing on the shoulders of others, our common ancestors.

Primatology—the study of living primates—is only one of several approaches that biological anthropologists use to understand what makes us human. Two others, paleoanthropology (which studies human origins through the fossil record) and molecular anthropology (which studies human origins through genetic analysis), also yield some surprising insights about our hominin relatives. For example, Zeresenay Alemsegad's painstaking field work and analysis of Selam, a 3.3 million-year old fossil of a 3-year-old australopithecine infant from Ethiopia, exemplifies how paleoanthropologists can blur boundaries between living humans and apes.

Selam, if alive today, would not be confused with a three-year-old human—but neither would we mistake her for a living ape. Selam's chimpanzee-like hyoid bone suggests a more ape-like form of vocal communication, rather than human language capability. Overall, she would look chimp-like in many respects—until she walked past you on two feet. In addition, based on Selam's brain development, Alemseged theorizes that Selam and her contemporaries experienced a human-like extended childhood with a complex social organization.

Fast-forward to the time when Neanderthals lived, about 130,000 – 30,000 years ago, and most paleoanthropologists would agree that language capacity among the Neanderthals was far more human-like than ape-like; in the Neanderthal fossil record, hyoids and other possible evidence of language can be found. Moreover, paleogeneticist Svante Pääbo's groundbreaking research in molecular anthropology strongly suggests that Neanderthals interbred with modern humans. Paabo's work informs our genetic understanding of relationships to ancient hominins in ways that one could hardly imagine not long ago—by extracting and comparing DNA from fossils comprised largely of rock in the shape of bones and teeth—and emphasizes the great biological continuity we see, not only within our own species, but with other hominins sometimes classified as different species.

Though genetics has made truly astounding and vital contributions toward biological anthropology by this work, it's important to acknowledge the equally pivotal role paleoanthropology continues to play in its tandem effort to flesh out humanity's roots. Paleoanthropologists like Alemsegad draw on every available source of information to both physically reconstruct hominin bodies and, perhaps more importantly, develop our understanding of how they may have lived, communicated, sustained themselves, and interacted with their environment and with each other. The work of Pääbo and others in his field offers powerful affirmations of paleoanthropological studies that have long investigated the contributions of Neanderthals and other hominins to the lineage of modern humans. Importantly, without paleoanthropology, the continued discovery and recovery of fossil specimens to later undergo genetic analysis would be greatly diminished.

Molecular anthropology and paleoanthropology, though often at odds with each other in the past regarding modern human evolution, now seem to be working together to chip away at theories that portray Neanderthals as inferior offshoots of humanity. Molecular anthropologists and paleoanthropologists also concur that that human evolution did not occur in ladder-like form, with one species leading to the next. Instead, the fossil evidence clearly reveals an evolutionary bush, with numerous hominin species existing at the same time and interacting through migration, some leading to modern humans and others going extinct.

Molecular anthropologist Spencer Wells uses DNA analysis to understand how our biological diversity correlates with ancient migration patterns from Africa into other continents. The study of our genetic evolution reveals that as humans migrated from Africa to all continents of the globe, they developed biological and cultural adaptations that allowed for survival in a variety of new environments. One example is skin color. Biological anthropologist Nina Jablonski uses satellite data to investigate the evolution of skin color, an aspect of human biological variation carrying tremendous social consequences. Jablonski underscores the importance of trying to understand skin color as a single trait affected by natural selection with its own evolutionary history and pressures, not as a tool to grouping humans into artificial races.

For Pääbo, Wells, Jablonski and others, technology affords the chance to investigate our origins in exciting new ways, adding pieces into the human puzzle at a record pace. At the same time, our technologies may well be changing who we are as a species and propelling us into an era of "neo-evolution."

Increasingly over time, human adaptations have been less related to predators, resources, or natural disasters, and more related to environmental and social pressures produced by other humans. Indeed, biological anthropologists have no choice but to consider the cultural components related to human evolutionary changes over time. Hominins have been constructing their own niches for a very long time, and when we make significant changes (such as agricultural subsistence), we must adapt to those changes. Classic examples of this include increases in sickle-cell anemia in new malarial environments, and greater lactose tolerance in regions with a long history of dairy farming.

Today we can, in some ways, evolve ourselves. We can enact biological change through genetic engineering, which operates at an astonishing pace in comparison to natural selection. Medical ethicist Harvey Fineberg calls this "neo-evolution". Fineberg goes beyond asking who we are as a species, to ask who we want to become and what genes we want our offspring to inherit. Depending on one's point of view, the future he envisions is both tantalizing and frightening: to some, it shows the promise of science to eradicate genetic abnormalities, while for others it raises the specter of eugenics. It's also worth remembering that while we may have the potential to influence certain genetic predispositions, changes in genotypes do not guarantee the desired results. Environmental and social pressures like pollution, nutrition or discrimination can trigger "epigenetic" changes which can turn genes on or off, or make them less or more active. This is important to factor in as we consider possible medical benefits from efforts in self-directed evolution. We must also ask: In an era of human-engineered, rapid-rate neo-evolution, who decides what the new human blueprints should be?

Technology figures in our evolutionary future in other ways as well. According to anthropologist Amber Case, many of our modern technologies are changing us into cyborgs: our smart phones, tablets and other tools are "exogenous components" that afford us astonishing and unsettling capabilities. They allow us to travel instantly through time and space and to create second, "digital selves" that represent our "analog selves" and interact with others in virtual environments. This has psychological implications for our analog selves that worry Case: a loss of mental reflection, the "ambient intimacy" of knowing that we can connect to anyone we want to at any time, and the "panic architecture" of managing endless information across multiple devices in virtual and real-world environments.

Despite her concerns, Case believes that our technological future is essentially positive. She suggests that at a fundamental level, much of this technology is focused on the basic concerns all humans share: who am I, where and how do I fit in, what do others think of me, who can I trust, who should I fear? Indeed, I would argue that we've evolved to be obsessed with what other humans are thinking—to be mind-readers in a sense—in a way that most would agree is uniquely human. For even though a baboon can assess those baboons it fears and those it can dominate, it cannot say something to a second baboon about a third baboon in order to trick that baboon into telling a fourth baboon to gang up on a fifth baboon. I think Facebook is a brilliant example of tapping into our evolved human psychology. We can have friends we've never met and let them know who we think we are—while we hope they like us and we try to assess what they're actually thinking and if they can be trusted. It's as if technology has provided an online supply of an addictive drug for a social mind evolved to crave that specific stimulant!

Yet our heightened concern for fairness in reciprocal relationships, in combination with our elevated sense of empathy and compassion, have led to something far greater than online chats: humanism itself. As Jane Goodall notes, chimps and baboons cannot rally together to save themselves from extinction; instead, they must rely on what she references as the "indomitable human spirit" to lessen harm done to the planet and all the living things that share it. As Goodall and other TED speakers in this course ask: will we use our highly evolved capabilities to secure a better future for ourselves and other species?

I hope those reading this essay, watching the TED Talks, and further exploring evolutionary perspectives on what makes us human, will view the continuities and discontinuities of our species as cause for celebration and less discrimination. Our social dependency and our prosocial need to identify ourselves, our friends, and our foes make us human. As a species, we clearly have major relationship problems, ranging from personal to global scales. Yet whenever we expand our levels of compassion and understanding, whenever we increase our feelings of empathy across cultural and even species boundaries, we benefit individually and as a species.

Get started

Zeresenay Alemseged

The search for humanity's roots, relevant talks.

Spencer Wells

A family tree for humanity.

Svante Pääbo

Dna clues to our inner neanderthal.

Nina Jablonski

Skin color is an illusion.

We are all cyborgs now

Harvey Fineberg

Are we ready for neo-evolution.

Frans de Waal

Moral behavior in animals.

Jane Goodall

What separates us from chimpanzees.

'Green-eyed monster' and 'stiff upper lip’: the evolution of the English language

Throughout history, thousands of words have been adopted from around the world into the English vocabulary. Writing for History Extra , Charlie Haylock takes us on a tour of the historical origins of many of the words and phrases we still use today

- Share on facebook

- Share on twitter

- Share on whatsapp

- Email to a friend

The evolution of spoken English began from the fifth century, with waves of attack and eventual occupation by the Angles, Saxons, Jutes and Frisians. They spoke the same West Germanic tongue but with different dialects. Their intermingling created a new Germanic language; now referred to as Anglo-Saxon, or Old English.

During the eighth, ninth and tenth centuries, the Vikings would plunder and settle, bringing with them another version of the same Germanic language, now referred to as Old Norse. The English and Viking amalgamation would become the second step in establishing a spoken English and the basis for the varying English dialects today.

In his book In a Manner of Speaking – The Story of Spoken English , Charlie Haylock, with the help of illustrations from cartoonist Barrie Appleby, explores the language – from the origins of Old English in northern Europe to the abbreviated language of texts used today…

- 10 First World War slang words we still use today

What is the history of English language?

In 1066, the Normans had an eclectic mix of languages: a Frankish influenced northern French dialect; Old Norse from their Viking roots; Flemish from the army supporting William the Conqueror 's wife, Matilda of Flanders; and the Brythonic based language of the mercenary Bretons.

The Normans kept the basic structure of the English language, but during the Middle English period they introduced around 10,000 words of their own into the English tongue. Many words were related to officialdom and are evident in the vocabulary surrounding administration, parliament, government, the legal profession and the crown. Many more words filtered down into everyday matters including food production, such as: beef; pork; herb; juice and poultry. They introduced words beginning with ‘con’, ‘de’, ‘dis’ and ‘en’, such as: conceal; continue; demand; encounter; disengage and engage.

More like this

They also included words ending in ‘age’ and ‘ence’ as in: advantage; courage; language and commence.

- "Damn your blood": Swearing in early modern English

How many words did Shakespeare invent?

The English Renaissance saw thousands of Greek- and Latin-based words enter the language. This occurred via the Italian Renaissance, and was greatly helped by English poets, authors and playwrights, especially Elizabethan-era playwright William Shakespeare who wrote many plays centred in Italy including Romeo and Juliet , The Merchant of Venice , Julius Caesar and Two Gentlemen of Verona .

These wordsmiths also made up and created many thousands of new words, leading to a debate known as the 'Inkhorn Controversy'. ‘Inkhorn’ was the term for an inkwell made out of a small horn and became a nickname for the new words being created by playwrights and poets.

One advocate for inkhorn words was Thomas Elyot, a prolific writer during the English Renaissance. He was well studied in both Latin and Greek, and as such, was able to introduce many new concocted words into the English vocabulary. Those academics and scholars totally against inkhorn words included Thomas Wilson who was not only an academic and scholar, but also as an author, diplomat, judge, privy councilor and Dean of Durham. He is likely best known for two publications, The Rule of Reason, conteinynge the Arte of Logique set forth in Englishe , and his most famous book, The Arte of Rhetorique . He was against the flowery extravagant speech and inkhorns of the English Renaissance and advocated a simpler way of writing, using words derived from Old English rather than from Latin and Greek.

Nevertheless, inkhorn words prevailed and William Shakespeare alone made up an estimated 1,750 words and idioms, many of which are household phrases today.

Overseas imports and the development of the English language

Elizabethan exploration, privateering and piracy was another source for English vocabulary. These came mainly from the Spanish and Portuguese, including many Caribbean and Native American words explorers from the nations had adopted, such as 'tobacco' and 'potato'.

Stuart colonialism on the eastern shores of America saw a great number of words from Native Americans being adopted and entering the English language direct, including 'canoe', and 'hammock'. The Pilgrim Fathers and subsequent English settlements adopted even more.

Britain's share in world trade saw a steady rise during the Tudor and Stuarts' exploration policies through to the Victorian empire building. This increase in trade would see another wave of new words entering the English vocabulary from foreign climes, including words from the Netherlands such as: landscape; scone; booze; schooner; skipper; avast; knapsack; easel; sketch – and a great deal more.

- What is the origin of the phrase ‘Dutch Courage’?

The British empire at its height encompassed one quarter of the Earth's land mass, and ruled over hundreds of millions of different peoples throughout the world. The English language evolved alongside this empire, with words being adopted into the vocabulary. Numerous words from India alone have become common in English today, such as: pyjamas; khaki; bungalow; jodhpurs; juggernaut; curry; chutney; shampoo and thug – to name but a few.

What is the American influence on English?

American influence on English has been profound. American literature became more popular in England, as did films with the advent of the movies and Hollywood, along with songs, music and dance and many American programmes on television. The US was also allies of Britain in two world wars and still use British-based USAF airfields. All these factors together with the age of the computer, means that even more Americanisms and phrases have been adopted into the English vocabulary.

One example is the phrase ‘stiff upper lip’. It’s believed that this originated as the Americans saw the English aristocracy speaking with a strict ‘standard English’, which necessitated an immobile upper lip to pronounce it, no matter what the circumstances.

Other examples of American-influenced phrases include: no axe to grind; sitting on the fence; poker face; stake a claim – and words such as: bedrock; smooch; raincoat; skyscraper; joyride; showdown; cocktail and cookie.

- From candy to diapers: the purity of American English

The evolution of the English language continues…

The English language has never had an official standard. It has evolved through the centuries and adopted many thousands of words through overseas exploration, international trade, and the building of an empire. It has progressed from very humble beginnings as a dialect of Germanic settlers in the 5th century, to a global language in the 21st century. It is a rich language with tens of thousands more words in its vocabulary than any other language and as Maria Legg writes in her foreword to In a Manner of Speaking : “Indeed, a history of the language must necessarily be a history of its people too.”

Charlie Haylock is the author of In a Manner of Speaking – The Story of Spoken English (Amberley Books 2017), which is illustrated by cartoonist Barrie Appleby

This article was first published by HistoryExtra in March 2017

JUMP into SPRING! Get your first 6 issues for £9.99

+ FREE HistoryExtra membership (special offers) - worth £34.99!

Sign up for the weekly HistoryExtra newsletter

Sign up to receive our newsletter!

By entering your details, you are agreeing to our terms and conditions and privacy policy . You can unsubscribe at any time.

JUMP into SPRING! Get your first 6 issues for

USA Subscription offer!

Save 76% on the shop price when you subscribe today - Get 13 issues for just $45 + FREE access to HistoryExtra.com

HistoryExtra podcast

Listen to the latest episodes now

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

How the English Language Conquered the World

By Amy Chua

- Jan. 18, 2022

THE RISE OF ENGLISH Global Politics and the Power of Language By Rosemary Salomone

“Every time the question of language surfaces,” the Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci wrote, “in one way or another a series of other problems are coming to the fore,” like “the enlargement of the governing class,” the “relationships between the governing groups and the national–popular mass” and the fight over “cultural hegemony.” Vindicating Gramsci, Rosemary Salomone’s “The Rise of English” explores the language wars being fought all over the world, revealing the political, economic and cultural stakes behind these wars, and showing that so far English is winning. It is a panoramic, endlessly fascinating and eye-opening book, with an arresting fact on nearly every page.

English is the world’s most widely spoken language, with some 1.5 billion speakers even though it’s native for fewer than 400 million. English accounts for 60 percent of world internet content and is the lingua franca of pop culture and the global economy. All 100 of the world’s most influential science journals publish in English. “Across Europe, close to 100 percent of students study English at some point in their education.”

Even in France, where countering the hegemony of English is an official obsession, English is winning. French bureaucrats constantly try to ban Anglicisms “such as gamer , dark web and fake news ,” Salomone writes, but their edicts are “quietly ignored.” Although a French statute called the Toubon Law “requires radio stations to play 35 percent French songs,” “the remaining 65 percent is flooded with American music.” Many young French artists sing in English. By law, French schoolchildren must study a foreign language, and while eight languages are available, 90 percent choose English.

Salomone, the Kenneth Wang professor of law at St. John’s University School of Law, tends to glide over why English won, simply stating that English is the language of neoliberalism and globalization, which seems to beg the question. But she is meticulous and nuanced in chronicling the battles being fought over language policy in countries ranging from Italy to Congo, and analyzing the unexpected winners and losers.

Exactly whom English benefits is complicated. Obviously it benefits native Anglophones. Americans, with what Salomone calls their “smug monolingualism,” are often blissfully unaware of the advantage they have because of the worldwide dominance of their native tongue. English also benefits globally connected market-dominant minorities in non-Western countries, like English-speaking whites in South Africa or the Anglophone Tutsi elite in Rwanda. In former French colonies like Algeria and Morocco, shifting from French to English is seen not just as the key to modernization, but as a form of resistance against their colonial past.

In India, the role of English is spectacularly complex. The ruling Hindu nationalist Indian People’s Party prefers to depict English as the colonizers’ language, impeding the vision of an India unified by Hindu culture and Hindi. By contrast, for speakers of non-Hindi languages and members of lower castes, English is often seen as a shield against majority domination. Some reformers see English as an “egalitarian language” in contrast to Indian languages, which carry “the legacy of caste.” English is also a symbol of social status. As a character in a recent Bollywood hit says: “English isn’t just a language in this country. It’s a class.” Meanwhile, Indian tiger parents, “from the wealthiest to the poorest,” press for their children to be taught in English, seeing it as the ticket to upward mobility.

Salomone’s South Africa chapter is among the most interesting in the book. Along with Afrikaans, English is one of South Africa’s 11 official languages, and even though only 9.6 percent of the population speak English as their first language, it “dominates every sector,” including government, the internet, business, broadcasting, the press, street signs and popular music. But English is not only the language of South Africa’s commercial and political elite. It was also the language of Black resistance to the Afrikaner-dominated apartheid regime, giving it enormous symbolic importance. Thus, recent years have seen poor and working-class Black activists pushing for English-only instruction in universities, even though many of them are not proficient in the language. Opponents of English, however, argue that shifting away from Afrikaans instruction disproportionately hurts the poor of all races, including lower-income Blacks, whites and mixed-race “colored” South Africans. Meanwhile, younger “colored activists are challenging the English-Afrikaans binary and exploring alternate forms of expression, like AfriKaaps,” a form of Afrikaans promoted by hip-hop artists. For now, though, “the constitutional commitment to language equality in South Africa is aspirational at best,” and “English reigns supreme for its economic power.”

Learning English pays, with “positive labor market returns across the globe.” Throughout academia today, even in Europe and Asia, “the rule no longer is ‘Publish or perish’ but rather ‘Publish in English … or perish.’” In the Middle East, “employees who were more proficient in English earned salaries from 5 percent (Tunisia) to a stunning 200 percent (Iraq) more than their non-English-speaking counterparts.” In Argentina, 90 percent of employers “believed that English was an indispensable skill for managers and directors.” In every country she surveys, higher income is correlated with English proficiency.

Salomone concludes with a brief discussion of American monolingualism, describing the waves of political angst over threats to English as the national language, while advocating for more multilingualism in Anglophone countries. Beyond the economic benefits of speaking multiple languages in a globalized world, Salomone cites studies that show learning new languages improves overall cognitive function. In addition, she argues, “observing life through a wide linguistic and cultural lens leads to greater creativity and innovation.”

“The Rise of English” has its weaknesses. Most important, the book lacks any clear thesis beyond suggesting “language is political; it’s complicated.” In addition, the book doesn’t tie together or reflect on the divergence of its case studies; I frequently found myself wondering why the experiences of (say) France or Italy or Denmark were different, and what we should take from that fact.

Finally, the book offers no clear evaluative framework. Salomone focuses primarily on straightforward economic factors (which often boil down to the same thing: access to global markets), but there is a smattering of underdeveloped discussion of other, more elusive themes too, like race, equity, colonialism and imperialism. This hodgepodge of incommensurables may trace back to the book’s origins. In her preface, Salomone writes, “My initial plan was to write a book on the value of language in the global economy.” But “the deeper I dug … the more I viewed the issues through a wider global lens and the clearer the connections to educational equity, identity and democratic participation appeared.” Unfortunately, she never quite gets a handle on these deeper issues.

Will Mandarin, with its 1.11 billion speakers, eventually replace English as the world’s lingua franca? Will Google or Microsoft Translate moot the issue? Salomone’s painstakingly thorough book addresses these questions too (concluding probably not).

The justifications for English — or any language — as a global lingua franca are based primarily in economic efficiency. By contrast, the reasons to protect local languages mostly sound in different registers — the importance of cultural heritage; the geopolitics of resistance to great powers; the value of Indigenous art; the beauty of idiosyncratic words in other languages that describe all the different types of snow or the different flavors of melancholia. As Gramsci reminded us, the question of who speaks what language invariably puts all this on the table.

Amy Chua is the John M. Duff Jr. professor of law at Yale Law School and the author of “World on Fire: How Exporting Free Market Democracy Breeds Ethnic Hatred and Global Instability” and “Political Tribes: Group Instinct and the Fate of Nations.”

THE RISE OF ENGLISH Global Politics and the Power of Language By Rosemary Salomone 488 pp. Oxford University Press. $35.

Evolution in the English Language Essay (Article)

English is now indisputably an international language. It even has a new acronym: ELF, or English as a Lingua Franca . However, unlike French or Latin, the original LFs only of the European world, English is literally everywhere, and is the default language for many industries and fields of study and employment.

Whether you are travelling, living abroad in an Anglophone country, or studying English in school, you will find that there is not just one variant of English. If you are not careful, you can run afoul of regional differences in word usage that can embarrass or inconvenience you, and may detract from the clarity of your writing.

Because of the mix of ethnicities that makes up the USA, American English has evolved along different lines. Thus, a British speaker and an American speaker can find themselves talking at cross purposes unless they understand the idiomatic differences between the two regional forms of the language. The following are some examples from personal experience:

Consider the classic error made by a British hotel guest when suggesting to an attractive young person that they sightsee together the following day. “Shall I come round and knock you up in the morning?” asks the Brit, and the American wonders why this ill-mannered lout wishes to get her with child.

The phrase “to knock up” is US slang for getting someone pregnant. He could have said, “Shall I knock on your door in the morning?” and this international incident would have been averted entirely. And by the way, the phrase “young person” is another Briticism, albeit one that may be a bit vintage. Americans would speak of a “young lady” if they have any manners.

Another classic mistake can occur in a “pub” (known to Yanks as a “bar”), when someone offers “cider”. In the USA, almost without exception, “cider” is unfiltered apple juice. It is served as an eco-friendly and often locally sourced alternative to less healthy “soft” (non-alcoholic) beverages such as Coke, Pepsi, Dr. Pepper or other overpriced mixtures of sugar water, caramel coloring, and marketing.

In Britain, on the other hand, the term “cider” refers to a fairly potent (and tasty) fermented version of apple juice that can set the unwary imbiber reeling. Cider was once fermented enthusiastically everywhere in the colonies, as was Perry, or pear cider, but Prohibition nearly wiped that industry out. It making a comeback as an alcoholic drink, along with locally made sausage, and boutique beers, but it will be reliably referred to as “hard cider”.

As long as we are on the topic of embarrassing mistakes, consider the word “rubber”. In the USA, this refers to the substance derived from latex, but also to male contraceptives, or condoms, which protect the male reproductive organ, or “pecker” (USA). In the UK, the word “rubber” refers to an eraser, and the “pecker” is the chin, meaning that “keeping one’s pecker up” is a phrase to use with care. Another pitfall phrase is “on the job”. In the USA, this means literally while working – as in “managerial training on the job”.

In British English, on the other hand, this can refer to that most intimate of consensual interpersonal activities, so avoid this phrase unless you are sure of your audience! “Fannies” in the USA are what a lady sits upon, but in Britain, the word refers to her most female of parts. This is another word to avoid!

Now that we are all thoroughly embarrassed, consider the word that, in Britain, is used to refer to cigarettes, or at least used to be; “f*g”. In the USA, this pejorative and offensive term for a homosexual should really be avoided entirely. Another explosive word, ni**er, seems to be used in the UK to apply to all people with dark skin. In the USA, this is called the n-word, and refers usually to those whose African ancestors were enslaved. These words have such hurtful connotations that the best strategy is to just find different ways to describe others.

Moving on to happier topics, and remembering the popular modern adage, “Life is short; eat dessert first”, take note that the traveler who asks for “pudding” in the UK will be served a sweet ending to a meal of almost any type.

In the USA, however, “pudding” means a very specific sweet; a soft composition of milk and eggs (or the modern food chemist’s equivalent thereof), cooked to a consistency that sticks to the spoon. A baked mixture of milk, eggs, and sugar, with bread cubes, cooked rice, pasta, or tapioca, generates a nearly endless ethnic and regional variety of “puddings” (bread pudding, noodle kugel , etc.). They can all be yummy in the hands of a deft cook.

Likewise, “biscuits” in the UK are a “cookie” in the USA. American “biscuits” are actually a quick bread, not made with yeast, but with baking powder and a great deal of shortening (butter, lard, or vegetable fat).

They are not sweet, but serve as a magnificent transport mechanism for gravy, drippings, butter, honey, maple syrup, sorghum syrup, or fruit preserves. A specialized American use of biscuits is strawberry shortcake, which originally meant a biscuit (salty) topped with fresh berries (sweet and tart) and whipped cream (richly unctuous and perhaps sweet).

This is all fun, but there are additionally serious differences that anyone trying to live, work, or study internationally needs to remember. These divergences in practice are extensive and keeping a reference list at hand or bookmarked on the computer is a good idea. Here is a sampling:

- In American English, teams and corporations usually take singular forms of verbs (e.g., Apple Corporation has brought out a new model), whereas in the UK, they often take plural forms (e.g., Manchester United are the winners. This is an instant signal indicating where one’s English was learned.

- British English uses shall more often than will .

- In British English, the preposition from is used to indicate start times (e.g., Classes start from Monday), whereas in American English, the word “starting” or the preposition “on” is used instead (e.g., Classes start on Monday”, or “It will run six weeks, starting Monday”).

- Americans enroll in courses, go to addresses on streets, and enroll in courses, while Brits use the other preposition.

As English is used more and more widely and by peoples all over the world, there will be inevitable evolution in the language. What will “correct English” mean in 10, or 50 years? This subject is much too large for this article, but is the subject of serious academic consideration. In the meantime, try to use local variants but don’t let worry keep you from trying out your English in every possible situation.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, August 20). Evolution in the English Language. https://ivypanda.com/essays/english-language/

"Evolution in the English Language." IvyPanda , 20 Aug. 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/english-language/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Evolution in the English Language'. 20 August.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Evolution in the English Language." August 20, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/english-language/.

1. IvyPanda . "Evolution in the English Language." August 20, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/english-language/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Evolution in the English Language." August 20, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/english-language/.

- English as a Lingua Franca

- English as a Lingua Franca and Its Implications

- English as a Lingua Franca in Modern Interpretation

- Bioethics in the Film “The Cider House Rules”

- Cider House Rules Movie and Abortion

- Comparative Of A Widow For One Year And The Cider House Rules

- Conflicts in Anglophone and Francophone Africa

- Do ethical flaws in an artwork detract from its aesthetic value?

- Avocado Production - Alligator Pear

- Managing a Sausage Production Enterprise

- Getting Tongue-Tied: When the English Language Starts Dominating

- Language Development Analysis

- Conservative and Liberal Languages

- English as a Global Language Essay

- Does Global English Mean Linguistic Holocaust?

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Evolution

- About the Society for the Study of Evolution

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

Editor-in-Chief

Hélène Morlon

Tim Connallon

Managing Editor

Melinda Modrell

About the journal

Evolution , the flagship journal of the Society for the Study of Evolution, publishes articles in evolutionary biology focused on evolutionary phenomena and processes at all levels of biological organisation.

Latest articles

Latest posts on x, virtual issues.

Genetics of adaptation & fitness landscapes

Extending microevolutionary theory to a macroevolutionary theory of complex adaptations

Women in Speciation

More from sse.

EELS program

The Evolution English Language Support (EELS) Program from SSE offers free, light touch editing for authors submitting to Evolution for whom English is not their preferred language.

Find out more

2023 Evolution Meeting

The Evolution conference is the joint annual meeting of the American Society of Naturalists, the Society for the Study of Evolution, and the Society of Systematic Biologists. Recordings from the virtual and in-person portions are now available. Watch now

Become an SSE member

Join the Society for the Study of Evolution today and benefit from:

Free traditional publication in Evolution

Free online access to Evolution

50% discount on open access publication fees for SSE members when publishing in Evolution

30% discount on open access publication fees for SSE members when publishing in Evolution Letters

Find out more

International Symposia Series

Connect with local evolutionary biologists in our International Symposia Series. Each symposium is geared toward an evolutionary biology community in a particular region of the world and features local early career researchers and senior researchers.

Student Research Grants

SSE offers research grants for early and advanced PhD students. Deadlines are in the spring and fall. Awards are up to $2500 for early PhD students and $3500 for advanced PhD students.

SSE Presidents' Award for Outstanding Dissertation Paper in Evolution

Congratulations to Michael Itgen for his winning paper, “Genome size drives morphological evolution in organ-specific ways."

Meet the Editorial Board

Learn more about the team behind the journal. Editorial board

Evolution Highlights

The Evolution Highlights series highlights some of the interesting and varied papers published within the last few years in Evolution . Explore the collection

Submit your work

Submit your manuscript for consideration to be included in a 2023 issue of Evolution .

Review Author Guidelines Submission Site

Read and Publish deals

Authors interested in publishing in Evolution may be able to publish their paper Open Access using funds available through their institution’s agreement with OUP.

Find out if your institution is participating .

Email alerts

Register to receive table of contents email alerts as soon as new issues of Evolution are published online.

Discover a more complete picture of how readers engage with research in Evolution through Altmetric data. Now available on article pages.

Recommend to your library

Fill out our simple online form to recommend Evolution to your library.

Recommend now

Related Titles

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1558-5646

- Print ISSN 0014-3820

- Copyright © 2024 Society for the Study of Evolution

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Ideas on Human Evolution

Selected essays, 1949–1961.

- Edited by: William Howells

- X / Twitter

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

- Language: English

- Publisher: Harvard University Press

- Copyright year: 1962

- Edition: Reprint 2014

- Audience: Professional and scholarly;

- Front matter: 13

- Main content: 555

- Other: Zahlr. Abb.

- Keywords: Human beings -- Origin. ; Biological Evolution.

- Published: October 1, 2013

- ISBN: 9780674592971

- Published: February 5, 1962

- ISBN: 9780674592957

Country/region

- Afghanistan AFN ؋

- Armenia AMD դր.

- Australia AUD $

- Austria EUR €

- Azerbaijan AZN ₼

- Bahrain AUD $

- Bangladesh BDT ৳

- Belgium EUR €

- Bhutan AUD $

- Canada CAD $

- China CNY ¥

- Czechia CZK Kč

- Denmark DKK kr.

- Finland EUR €

- France EUR €

- Germany EUR €

- Hong Kong SAR HKD $

- India INR ₹

- Indonesia IDR Rp

- Ireland EUR €

- Israel ILS ₪

- Italy EUR €

- Japan JPY ¥

- Jordan AUD $

- Kazakhstan KZT 〒

- Kuwait AUD $

- Kyrgyzstan KGS som

- Lebanon LBP ل.ل

- Macao SAR MOP P

- Malaysia MYR RM

- Maldives MVR MVR

- Mongolia MNT ₮

- Myanmar (Burma) MMK K

- Nepal NPR ₨

- Netherlands EUR €

- New Zealand NZD $

- Norway AUD $

- Pakistan PKR ₨

- Palestinian Territories ILS ₪

- Philippines PHP ₱

- Poland PLN zł

- Portugal EUR €

- Russia RUB ₽

- Singapore SGD $

- South Korea KRW ₩

- Spain EUR €

- Sri Lanka LKR ₨

- Sweden SEK kr

- Switzerland CHF CHF

- Tajikistan TJS ЅМ

- Thailand THB ฿

- Timor-Leste USD $

- Türkiye TRY ₺

- Turkmenistan AUD $

- United Arab Emirates AED د.إ

- United Kingdom GBP £

- United States USD $

- Uzbekistan UZS

- Vietnam VND ₫

- Yemen YER ﷼

The English Evolution

Essay Evolution

(1) 1 total reviews

Couldn't load pickup availability