Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Racial Discrimination — The Impact of Racism on the Society

Racism in Society, Its Effects and Ways to Overcome

- Categories: Racial Discrimination

About this sample

Words: 2796 |

14 min read

Published: Jun 10, 2020

Words: 2796 | Pages: 6 | 14 min read

Table of contents

Executive summary, the effects of racism in today’s world (essay), works cited.

- The current platform of social media has given many of the minorities their voice; they can make sure that the world can hear them and their opinions are made clear. This phenomenon is only going to rise with the rise of social media in the coming years.

- The diversity of race, culture and ethnicity that has been seen as a cause of rift and disrupt in the society in the past, will act as a catalyst for social development sooner rather than later, with the decrease in racism.

- Racist view of an individual are not inherited, they are learned. With that in mind, it is fair to assume that the coming generations will not be as critical of an individual’s race as the older generations have been.

- If people dismiss the concept of racial/ethnical evaluations and instead, evaluate an individual on one’s abilities and capabilities, the economic development will definitely have a rise.

- A lot of intra-society grievances and mishaps that are caused due to misconceptions of an ethnic group can be reduced as social interaction increases.

- As people from different ethnic backgrounds, coming from humble beginnings, discriminated throughout their careers, manage to emerge successful to the public platform, the racist train of thought is being exposed and will continue to do so. This will inspire people from any and every background, race, language, ethnicity to step forward and compete on the large scale.

- Racism and prejudice are at the root of racial profiling and that racial bias has been interweaved into the culture of most societies. However, these chains have grown much weaker as time has passed, to the point that they are in a fragile state.

- Another ray of hope that can be witnessed nowadays that people are no longer ashamed of their cultural identity. People now believe that their cultural background is in no way or form inferior to another and thus, worth defending. This will turn out to be a major factor in minimizing racism in the future.

- Because of the strong activism against racism, a new phenomenon has emerged that is color blindness, which is the complete disregard of racial characteristics in any kind of social situation.

- The world is definitely going in the right direction concerning the curse that is Racism; however, it is far too early to claim that humankind will completely rid itself of this vile malignance. PrescriptionsRacism is a curse that has plagued humanity since long. It has been responsible for multitudes of nefarious acts in the past and is causing a lot of harm even now, therefore care must be taken that this problem is brought under control as soon as possible so as not to hinder the growth of human societies. The following are some of the precautions, so to say, that will help tremendously in tackling this problem.

- The first and foremost step is to take this problem seriously both on an individual and on community level. Racism is something that can not be termed as a minor issue and dismissed. History books dictate that racism is responsible for countless deaths and will continue to claim the lives of more innocents unless it is brought under control with a firm hand. The first step to controlling it is to accept racism as a serious problem.

- Another problem is that many misconceptions or rumors that are dismissed by most people as a trivial detail are sometimes a big deal for other people, which might push them over the edge to commit a crime or some other injustice. So whenever there is an anomaly, a misconception or a misrepresentation of an individual’s, a group’s or a society’s ideas or beliefs, try to be the voice of reason rather than staying quiet about it. Decades of staying silent over crucial issues has caused us much harm and brought us to this point, staying silent now can only lead us to annihilation.

- One of most radical and effective solution to racial diversity is to turn it from something negative to something positive. Where previously, one does not talk to someone because of his or her cultural differences, now talk to them exactly because of that. If different cultures and races start taking steps, baby steps even, towards the goal of acquiring mutual respect and trust, racism can be held in check.

- On the national level, contingencies can be introduced and laws can be made that support cultural diversity and preach against anything that puts it in harm’s way. Taking such measures will make every single member of the society well aware of the scale of this problem and people will take it more seriously rather than ridiculing it.

- Finally, just as being racist was a part of the culture in the older generations, we need to make being anti-racist a part of our cultures. If our children, our youth grew up watching their elders and their role models dissing and undermining racism at every point of life, they will definitely adopt a lifestyle that will allow no racial discriminations in their life.

Methodology

Findings and results.

- Is racism justifiable?

- Is the current trend of racism increasing in your country?

- Do you have any acquaintances or friends that belong to a different ethnical background?

- Would you ever use someone’s race against them to win an argument?

- Would you agree to work in a diverse racial environment?

- Will humankind ever rid itself of racism?

- Have you ever taken any measures to abate racism?

- Racism has changed the relationship between people?

- Racial discriminations are apparent in our everyday life.

- One racial/ethnic group can be superior to another

- Racial/ethnic factors can change your perception of a person.

- Racial diversity can cause problems in one’s society.

- Racial or Ethnical conflict should be in cooperated into the laws of one’s society.

- Are you satisfied with the way different ethnic groups are treated in your society?

- ABC News. (2021). The legacy of racism in America. https://abcnews.go.com/US/legacy-racism-america/story?id=77223885

- British Broadcasting Corporation. (2021). Racism: What is it? https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/53498245

- Chetty, R., Hendren, N., & Jones, M. R. (2020). Racism and the American economy. Harvard University.

- Gibson, K. L., & Oberg, K. (2019). What does racism look like today? National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2019/04/what-does-racism-look-like-today-feature/

- Hughey, M. W. (2021). White supremacy. The Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Sociology.

- Jones, M. T., & Janson, C. (2020). Racism and health: Evidence and needed research. Annual Review of Public Health, 41, 1-16.

- Krieger, N. (2019). Discrimination and racial inequities in health : A commentary and a research agenda. American Journal of Public Health, 109(S1), S82-S85.

- Kteily, N., Bruneau, E., Waytz, A., & Cotterill, S. (2021). The psychology of racism: A review of theory and research. Annual Review of Psychology, 72, 479-514.

- Schmitt, M. T., Branscombe, N. R., Postmes, T., & Garcia, A. (2014). The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 921-948.

- Williams, D. R., & Mohammed, S. A. (2013). Racism and health I: Pathways and scientific evidence. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(8), 1152-1173.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

7 pages / 3045 words

3 pages / 1420 words

3 pages / 1314 words

3 pages / 1257 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Racial Discrimination

The Black Student Alliance (BSA), along with other student groups, partnered together and held a protest on the steps of the campus’s central building, Mary Graydon Center. Consisting of 200 people, the protest was done to [...]

Obama's presence as the President of the United States is largely focused on the color of his skin. When he first ran, even the option of having a non-white president was seen as progress for America and its history of racism. [...]

These are a set of literature that is produced in the United States by authors of African descent. This literature is very significant in that they depict various important themes that are important in the modern day world. This [...]

The issue of racial injustice has persisted for decades, deeply rooted in the fabric of society. As readers seek to engage with literature that addresses these pressing concerns, "The Hate U Give" emerges as a powerful fictional [...]

In Black No More, by George Schuyler, the main character, Max Disher, experiences a scientific procedure that changes his skin from black to white. Originally very proud of his African-American descent, he finds himself [...]

In “The Woman Question,” Stephen Leacock uses empty stereotypes that he cannot support with evidence to argue why women are unable to progress in society. He does not have any evidence because women have never been given the [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Racism: What it is, how it affects us and why it’s everyone’s job to do something about it

Bray lecturer Camara Jones addresses racism as a public health crisis

- Post author By Kathryn

- Post date October 5, 2020

By Kathryn Stroppel

In 2018, the CDC found a 16% difference in the mortality rates of Blacks versus whites across all ages and causes of death. This means that white Americans can sometimes live more than a decade longer than Blacks.

In 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the discrepancy in health outcomes has only grown. Michigan’s population, for instance, is 14% Black, yet near the start of the pandemic, African Americans made up 35% of cases and 40% of deaths.

Because of this discrepancy in health outcomes, many scientists and government officials, including former American Public Health Association President Camara Jones, MD, PhD, MPH ; more than 50 municipalities nationwide; and a handful of legislators are attempting to root out this inequality and call it what it is: A public health crisis.

Dr. Jones, a nationally sought-after speaker and the college’s 2020 Bray Health Leadership Lecturer, has been engaged in this work for decades and says the time to act is now.

“The seductiveness of racism denial is so strong that if people just say a thing, six months from now they may forget why they said it. But if we start acting, we won’t forget why we’re acting,” she says. “That’s why it’s important right now to move beyond just naming something or putting out a statement making a declaration, but to actually engage in some kind of action.”

Synergies editor Kathryn Stroppel talked with Dr. Jones about this unique time in history, her work, racism’s effects on health and well-being, and what we can all do about it.

Let’s start with definitions. What is racism and why is important to acknowledge ‘systemic’ racism in particular?

“Racism is a system of structuring opportunity and assigning value based on the social interpretation of how one looks, which is what we call race, that unfairly disadvantages some individuals and communities, unfairly advantages other individuals and communities and saps the strength of the whole society through the waste of human resources.

“The reason that people are using those words ‘systemic’ or ‘structural racism’ is that sometimes if you say the word racism, people think you’re talking about an individual character flaw, or a personal moral failing, when in fact racism is a system.

“It’s not about trying to divide the room into who’s racist and who’s not. I am clear that the most profound impacts of racism happen without bias.

“The most profound impacts of racism are because structural racism has been institutionalized in our laws, customs and background norms. It does not require an identifiable perpetrator. And it most often manifests as inaction in the face of need.”

Why did you want to give the 2020 Bray Lecture?

“I’ve been doing this work for decades, and all of a sudden, now that we are recognizing the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color, and after the murder of George Floyd and all of the other highly publicized murders that have been happening, more and more people are interested in naming racism and asking how is racism is operating here and organizing and strategizing to act. I wish I could accept every invitation.”

What do you hope people take away from your lecture?

“When I was president of the American Public Health Association in 2016, I launched a national campaign against racism with three tasks: To name racism; to ask, ‘how is racism operating here?’; and then to organize and strategize to act.

“Naming racism is urgently important, especially in the context of widespread denial that racism exists. We have to say the word ‘racism’ to acknowledge that it exists, that it’s real and that it has profoundly negative impacts on the health and well-being of the nation.

“We have to be able to put together the words ‘systemic racism’ and ‘structural racism’ to able to be able to affirm that Black lives matter. That’s important and necessary, but insufficient.

“I then equip people with tools to address how racism operates by looking at the elements of decision making, which are in our structures, policies, practices, norms and values, and the who, what, when and where of decision making, especially who’s at the table and who’s not.

“After you have acknowledged that the problem exists, after you have some kind of understanding of what piece of it is in your wheelhouse and what lever you can pull, or who you know, you organize, strategize and collectively act.”

You’re known for using allegory to explain racism. Why is that?

“I use allegory because that’s how I see the world. There are two parts to it. One is that I’m observant. If I see something and if it makes me go, ‘Hmm,’ I just sort of store that away. And the second part is that I am a teacher. I’ve been telling a gardening allegory since before I started teaching at Harvard, but I later expanded that in order to help people understand how to contextualize the three levels of racism.

“As an assistant professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, I developed its first course on race and racism. As I’m teaching students and trying to help them understand different elements, different aspects of race, racism and anti-racism, I found myself using these images naturally just to explain things, and then I recognized that allegory is sort of a superpower.

“It makes conversations that might be otherwise difficult more accessible because we’re not talking about racism between you and me, we’re talking about these two flower pots and the pink and red seed, or we’re talking about an open or closed sign, or we’re talking about a conveyor belt or a cement factory. And so I put the image out there to suggest the ways that it can help us understand issues of race and racism. And then other people add to it or question certain parts and it becomes our collective image and our tool, not just mine.”

What should white people in particular see as their role and responsibility in this system?

“All of us need to recognize that racism exists, that it’s a system, that it saps the strength of the whole society through the waste of human resources, and that we can do something about it. White people in particular have to recognize that acknowledging their privilege is important – that your very being gives you the benefit of the doubt.

“White people who don’t want to walk around oblivious to their privilege or benefit from a racist society need to understand how to use their white privilege for the struggle.”

“An example: About six years ago now, in McKinney, Texas, outside of Dallas, we came to know that there was a group of pre-teens who wanted to celebrate a birthday at a neighborhood swimming pool. The people who were at the pool objected to them being there and called the police. And what we saw was a white police officer dragging a young Black girl by her hair, and then he sat on her, and the young Black boys were handcuffed sitting on the curb.

“The next day on TV, I heard a young white boy who was part of the friend group saying it was almost as if he were invisible to the police. He saw what was happening to his friends and he could have run home for safety, but instead, he recognized his white skin privilege. He stood up and videotaped all that was going on.

“So, the thing is not to deny your white skin privilege or try to shed it, the thing is to recognize it and use it. Then as you’re using it, don’t think of yourself as an ally. Think of yourself as a compatriot in the struggle to dismantle racism. We have to recognize that if you’re white, your anti-racist struggle is not for ‘them.’ It’s for all of us.”

Why did you transition from medicine to public health?

“Because there’s a difference between a narrow focus on the individual and a population-based approach. I started as a family physician, but then wanted to do public health because it made me sad to fix my patients up and then send them back out into the conditions that made them sick.

“I wanted to broaden my approach and really understand those conditions that make people sick or keep them well. From there, the data doesn’t necessarily turn into policy. So, I sort of went into the policy aspect of things. And then you recognize that you can have all the policy you want, but sometimes the policy is not enacted by politicians. So now I am considering maybe moving into politics.”

Speaking of politics, when engaging in discussions around racism and privilege, people will sometimes try to shut down the conversation for being ‘political.’ Is racism political?

“Racism exists. It’s foundational in our nation’s history. It continues to have profoundly negative impacts on the health and well-being of the nation. To describe what is happening is not political. If people want to deny what exists, then maybe they have political reasons for doing that.”

What are your thoughts on COVID-19 and our country’s approach to dealing with the virus?

“The way we’ve dealt with COVID-19 is a very medical care approach. We need to have a population view where you do random samples of people you identify as asymptomatic as well as symptomatic.

“When you have a narrow medical approach to testing, you can document the course of the pandemic, but you can’t do anything to change it.

“With a population-based approach we already know how to stop this pandemic: It’s stay-at-home orders, mask wearing, hand washing and social distancing.

“This very seductive, narrow focus on the individual is making us scoff at public health strategies that we could put in place and is hamstringing us in terms of appropriate responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“In terms of race, COVID-19 is unmasking the deep disinvestment in our communities, the historical injustices and the impact of residential segregation. This is the time to name racism as the cause of those things. The overrepresentation of people of color in poverty and white people in wealth is not happenstance.”

We have work to do. Learn how the college is transforming academia for equity .

- Tags COVID , Public Health

Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Black americans have a clear vision for reducing racism but little hope it will happen, many say key u.s. institutions should be rebuilt to ensure fair treatment.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to understand the nuances among Black people on issues of racial inequality and social change in the United States. This in-depth survey explores differences among Black Americans in their views on the social status of the Black population in the U.S.; their assessments of racial inequality; their visions for institutional and social change; and their outlook on the chances that these improvements will be made. The analysis is the latest in the Center’s series of in-depth surveys of public opinion among Black Americans (read the first, “ Faith Among Black Americans ” and “ Race Is Central to Identity for Black Americans and Affects How They Connect With Each Other ”).

The online survey of 3,912 Black U.S. adults was conducted Oct. 4-17, 2021. Black U.S. adults include those who are single-race, non-Hispanic Black Americans; multiracial non-Hispanic Black Americans; and adults who indicate they are Black and Hispanic. The survey includes 1,025 Black adults on Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP) and 2,887 Black adults on Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel. Respondents on both panels are recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses.

Recruiting panelists by phone or mail ensures that nearly all U.S. Black adults have a chance of selection. This gives us confidence that any sample can represent the whole population (see our Methods 101 explainer on random sampling). Here are the questions used for the survey of Black adults, along with its responses and methodology .

The terms “Black Americans,” “Black people” and “Black adults” are used interchangeably throughout this report to refer to U.S. adults who self-identify as Black, either alone or in combination with other races or Hispanic identity.

Throughout this report, “Black, non-Hispanic” respondents are those who identify as single-race Black and say they have no Hispanic background. “Black Hispanic” respondents are those who identify as Black and say they have Hispanic background. We use the terms “Black Hispanic” and “Hispanic Black” interchangeably. “Multiracial” respondents are those who indicate two or more racial backgrounds (one of which is Black) and say they are not Hispanic.

Respondents were asked a question about how important being Black was to how they think about themselves. In this report, we use the term “being Black” when referencing responses to this question.

In this report, “immigrant” refers to people who were not U.S. citizens at birth – in other words, those born outside the U.S., Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories to parents who were not U.S. citizens. We use the terms “immigrant,” “born abroad” and “foreign-born” interchangeably.

Throughout this report, “Democrats and Democratic leaners” and just “Democrats” both refer to respondents who identify politically with the Democratic Party or who are independent or some other party but lean toward the Democratic Party. “Republicans and Republican leaners” and just “Republicans” both refer to respondents who identify politically with the Republican Party or are independent or some other party but lean toward the Republican Party.

Respondents were asked a question about their voter registration status. In this report, respondents are considered registered to vote if they self-report being absolutely certain they are registered at their current address. Respondents are considered not registered to vote if they report not being registered or express uncertainty about their registration.

To create the upper-, middle- and lower-income tiers, respondents’ 2020 family incomes were adjusted for differences in purchasing power by geographic region and household size. Respondents were then placed into income tiers: “Middle income” is defined as two-thirds to double the median annual income for the entire survey sample. “Lower income” falls below that range, and “upper income” lies above it. For more information about how the income tiers were created, read the methodology .

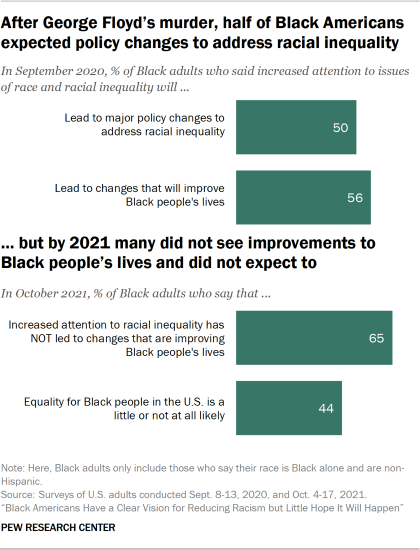

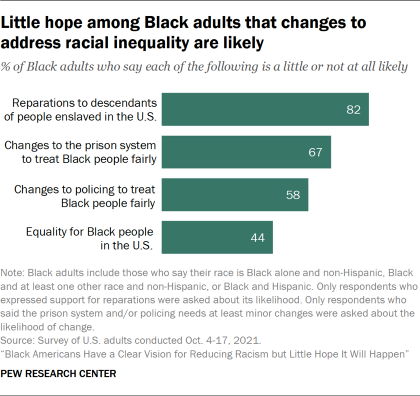

More than a year after the murder of George Floyd and the national protests, debate and political promises that ensued, 65% of Black Americans say the increased national attention on racial inequality has not led to changes that improved their lives. 1 And 44% say equality for Black people in the United States is not likely to be achieved, according to newly released findings from an October 2021 survey of Black Americans by Pew Research Center.

This is somewhat of a reversal in views from September 2020, when half of Black adults said the increased national focus on issues of race would lead to major policy changes to address racial inequality in the country and 56% expected changes that would make their lives better.

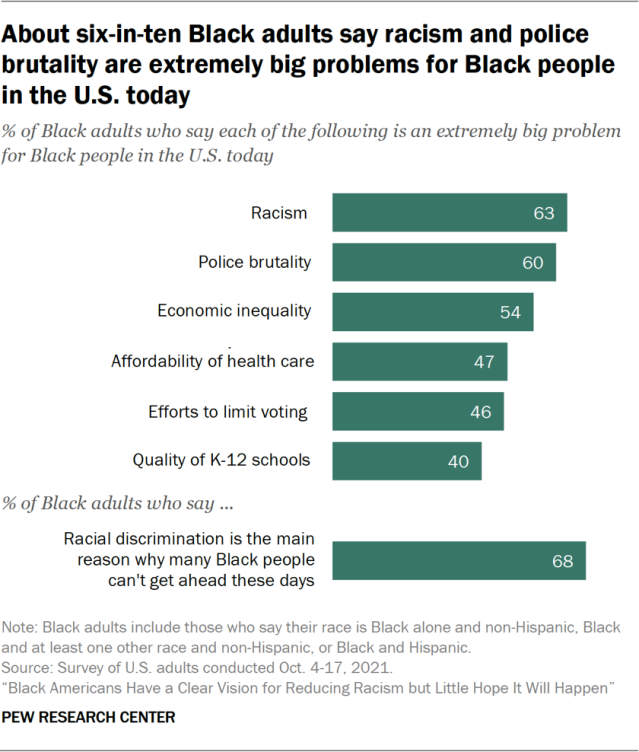

At the same time, many Black Americans are concerned about racial discrimination and its impact. Roughly eight-in-ten say they have personally experienced discrimination because of their race or ethnicity (79%), and most also say discrimination is the main reason many Black people cannot get ahead (68%).

Even so, Black Americans have a clear vision for how to achieve change when it comes to racial inequality. This includes support for significant reforms to or complete overhauls of several U.S. institutions to ensure fair treatment, particularly the criminal justice system; political engagement, primarily in the form of voting; support for Black businesses to advance Black communities; and reparations in the forms of educational, business and homeownership assistance. Yet alongside their assessments of inequality and ideas about progress exists pessimism about whether U.S. society and its institutions will change in ways that would reduce racism.

These findings emerge from an extensive Pew Research Center survey of 3,912 Black Americans conducted online Oct. 4-17, 2021. The survey explores how Black Americans assess their position in U.S. society and their ideas about social change. Overall, Black Americans are clear on what they think the problems are facing the country and how to remedy them. However, they are skeptical that meaningful changes will take place in their lifetime.

Black Americans see racism in our laws as a big problem and discrimination as a roadblock to progress

Black adults were asked in the survey to assess the current nature of racism in the United States and whether structural or individual sources of this racism are a bigger problem for Black people. About half of Black adults (52%) say racism in our laws is a bigger problem than racism by individual people, while four-in-ten (43%) say acts of racism committed by individual people is the bigger problem. Only 3% of Black adults say that Black people do not experience discrimination in the U.S. today.

In assessing the magnitude of problems that they face, the majority of Black Americans say racism (63%), police brutality (60%) and economic inequality (54%) are extremely or very big problems for Black people living in the U.S. Slightly smaller shares say the same about the affordability of health care (47%), limitations on voting (46%), and the quality of K-12 schools (40%).

Aside from their critiques of U.S. institutions, Black adults also feel the impact of racial inequality personally. Most Black adults say they occasionally or frequently experience unfair treatment because of their race or ethnicity (79%), and two-thirds (68%) cite racial discrimination as the main reason many Black people cannot get ahead today.

Black Americans’ views on reducing racial inequality

Black Americans are clear on the challenges they face because of racism. They are also clear on the solutions. These range from overhauls of policing practices and the criminal justice system to civic engagement and reparations to descendants of people enslaved in the United States.

Changing U.S. institutions such as policing, courts and prison systems

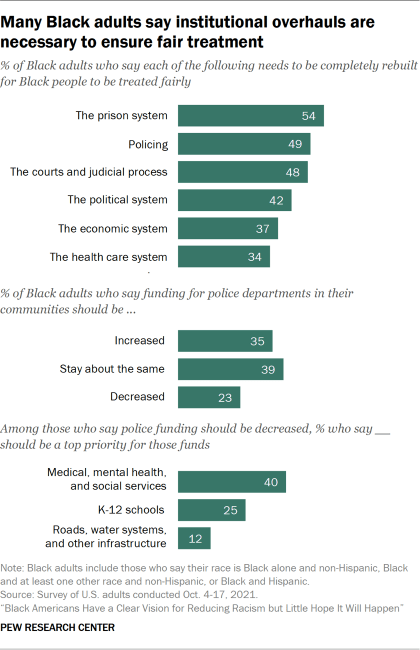

About nine-in-ten Black adults say multiple aspects of the criminal justice system need some kind of change (minor, major or a complete overhaul) to ensure fair treatment, with nearly all saying so about policing (95%), the courts and judicial process (95%), and the prison system (94%).

Roughly half of Black adults say policing (49%), the courts and judicial process (48%), and the prison system (54%) need to be completely rebuilt for Black people to be treated fairly. Smaller shares say the same about the political system (42%), the economic system (37%) and the health care system (34%), according to the October survey.

While Black Americans are in favor of significant changes to policing, most want spending on police departments in their communities to stay the same (39%) or increase (35%). A little more than one-in-five (23%) think spending on police departments in their area should be decreased.

Black adults who favor decreases in police spending are most likely to name medical, mental health and social services (40%) as the top priority for those reappropriated funds. Smaller shares say K-12 schools (25%), roads, water systems and other infrastructure (12%), and reducing taxes (13%) should be the top priority.

Voting and ‘buying Black’ viewed as important strategies for Black community advancement

Black Americans also have clear views on the types of political and civic engagement they believe will move Black communities forward. About six-in-ten Black adults say voting (63%) and supporting Black businesses or “buying Black” (58%) are extremely or very effective strategies for moving Black people toward equality in the U.S. Smaller though still significant shares say the same about volunteering with organizations dedicated to Black equality (48%), protesting (42%) and contacting elected officials (40%).

Black adults were also asked about the effectiveness of Black economic and political independence in moving them toward equality. About four-in-ten (39%) say Black ownership of all businesses in Black neighborhoods would be an extremely or very effective strategy for moving toward racial equality, while roughly three-in-ten (31%) say the same about establishing a national Black political party. And about a quarter of Black adults (27%) say having Black neighborhoods governed entirely by Black elected officials would be extremely or very effective in moving Black people toward equality.

Most Black Americans support repayment for slavery

Discussions about atonement for slavery predate the founding of the United States. As early as 1672 , Quaker abolitionists advocated for enslaved people to be paid for their labor once they were free. And in recent years, some U.S. cities and institutions have implemented reparations policies to do just that.

Most Black Americans say the legacy of slavery affects the position of Black people in the U.S. either a great deal (55%) or a fair amount (30%), according to the survey. And roughly three-quarters (77%) say descendants of people enslaved in the U.S. should be repaid in some way.

Black adults who say descendants of the enslaved should be repaid support doing so in different ways. About eight-in-ten say repayment in the forms of educational scholarships (80%), financial assistance for starting or improving a business (77%), and financial assistance for buying or remodeling a home (76%) would be extremely or very helpful. A slightly smaller share (69%) say cash payments would be extremely or very helpful forms of repayment for the descendants of enslaved people.

Where the responsibility for repayment lies is also clear for Black Americans. Among those who say the descendants of enslaved people should be repaid, 81% say the U.S. federal government should have all or most of the responsibility for repayment. About three-quarters (76%) say businesses and banks that profited from slavery should bear all or most of the responsibility for repayment. And roughly six-in-ten say the same about colleges and universities that benefited from slavery (63%) and descendants of families who engaged in the slave trade (60%).

Black Americans are skeptical change will happen

Even though Black Americans’ visions for social change are clear, very few expect them to be implemented. Overall, 44% of Black adults say equality for Black people in the U.S. is a little or not at all likely. A little over a third (38%) say it is somewhat likely and only 13% say it is extremely or very likely.

They also do not think specific institutions will change. Two-thirds of Black adults say changes to the prison system (67%) and the courts and judicial process (65%) that would ensure fair treatment for Black people are a little or not at all likely in their lifetime. About six-in-ten (58%) say the same about policing. Only about one-in-ten say changes to policing (13%), the courts and judicial process (12%), and the prison system (11%) are extremely or very likely.

This pessimism is not only about the criminal justice system. The majority of Black adults say the political (63%), economic (62%) and health care (51%) systems are also unlikely to change in their lifetime.

Black Americans’ vision for social change includes reparations. However, much like their pessimism about institutional change, very few think they will see reparations in their lifetime. Among Black adults who say the descendants of people enslaved in the U.S. should be repaid, 82% say reparations for slavery are unlikely to occur in their lifetime. About one-in-ten (11%) say repayment is somewhat likely, while only 7% say repayment is extremely or very likely to happen in their lifetime.

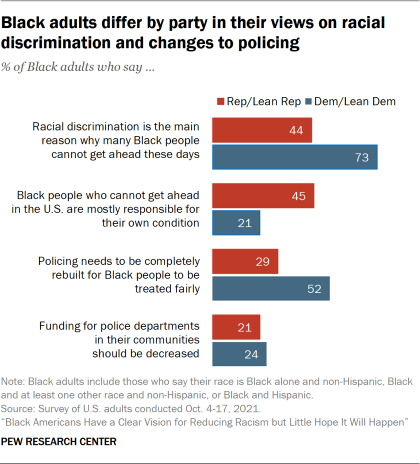

Black Democrats, Republicans differ on assessments of inequality and visions for social change

Party affiliation is one key point of difference among Black Americans in their assessments of racial inequality and their visions for social change. Black Republicans and Republican leaners are more likely than Black Democrats and Democratic leaners to focus on the acts of individuals. For example, when summarizing the nature of racism against Black people in the U.S., the majority of Black Republicans (59%) say racist acts committed by individual people is a bigger problem for Black people than racism in our laws. Black Democrats (41%) are less likely to hold this view.

Black Republicans (45%) are also more likely than Black Democrats (21%) to say that Black people who cannot get ahead in the U.S. are mostly responsible for their own condition. And while similar shares of Black Republicans (79%) and Democrats (80%) say they experience racial discrimination on a regular basis, Republicans (64%) are more likely than Democrats (36%) to say that most Black people who want to get ahead can make it if they are willing to work hard.

On the other hand, Black Democrats are more likely than Black Republicans to focus on the impact that racial inequality has on Black Americans. Seven-in-ten Black Democrats (73%) say racial discrimination is the main reason many Black people cannot get ahead in the U.S, while about four-in-ten Black Republicans (44%) say the same. And Black Democrats are more likely than Black Republicans to say racism (67% vs. 46%) and police brutality (65% vs. 44%) are extremely big problems for Black people today.

Black Democrats are also more critical of U.S. institutions than Black Republicans are. For example, Black Democrats are more likely than Black Republicans to say the prison system (57% vs. 35%), policing (52% vs. 29%) and the courts and judicial process (50% vs. 35%) should be completely rebuilt for Black people to be treated fairly.

While the share of Black Democrats who want to see large-scale changes to the criminal justice system exceeds that of Black Republicans, they share similar views on police funding. Four-in-ten each of Black Democrats and Black Republicans say funding for police departments in their communities should remain the same, while around a third of each partisan coalition (36% and 37%, respectively) says funding should increase. Only about one-in-four Black Democrats (24%) and one-in-five Black Republicans (21%) say funding for police departments in their communities should decrease.

Among the survey’s other findings:

Black adults differ by age in their views on political strategies. Black adults ages 65 and older (77%) are most likely to say voting is an extremely or very effective strategy for moving Black people toward equality. They are significantly more likely than Black adults ages 18 to 29 (48%) and 30 to 49 (60%) to say this. Black adults 65 and older (48%) are also more likely than those ages 30 to 49 (38%) and 50 to 64 (42%) to say protesting is an extremely or very effective strategy. Roughly four-in-ten Black adults ages 18 to 29 say this (44%).

Gender plays a role in how Black adults view policing. Though majorities of Black women (65%) and men (56%) say police brutality is an extremely big problem for Black people living in the U.S. today, Black women are more likely than Black men to hold this view. When it comes to criminal justice, Black women (56%) and men (51%) are about equally likely to share the view that the prison system should be completely rebuilt to ensure fair treatment of Black people. However, Black women (52%) are slightly more likely than Black men (45%) to say this about policing. On the matter of police funding, Black women (39%) are slightly more likely than Black men (31%) to say police funding in their communities should be increased. On the other hand, Black men are more likely than Black women to prefer that funding stay the same (44% vs. 36%). Smaller shares of both Black men (23%) and women (22%) would like to see police funding decreased.

Income impacts Black adults’ views on reparations. Roughly eight-in-ten Black adults with lower (78%), middle (77%) and upper incomes (79%) say the descendants of people enslaved in the U.S. should receive reparations. Among those who support reparations, Black adults with upper and middle incomes (both 84%) are more likely than those with lower incomes (75%) to say educational scholarships would be an extremely or very helpful form of repayment. However, of those who support reparations, Black adults with lower (72%) and middle incomes (68%) are more likely than those with higher incomes (57%) to say cash payments would be an extremely or very helpful form of repayment for slavery.

- Black adults in the September 2020 survey only include those who say their race is Black alone and are non-Hispanic. The same is true only for the questions of improvements to Black people’s lives and equality in the United States in the October 2021 survey. Throughout the rest of this report, Black adults include those who say their race is Black alone and non-Hispanic; those who say their race is Black and at least one other race and non-Hispanic; or Black and Hispanic, unless otherwise noted. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

Report Materials

Table of contents, race is central to identity for black americans and affects how they connect with each other, black americans’ views of and engagement with science, black catholics in america, facts about the u.s. black population, the growing diversity of black america, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Systemic racism and America today

Subscribe to how we rise, john r. allen john r. allen.

June 11, 2020

Unaddressed systemic racism is, in my mind, the most important issue in the United States today. And it has been so since before the founding of our nation.

Slavery was America’s “original sin.” It was not solved by the framers of the U.S. Constitution, nor was it resolved by the horrendous conflict that was of the American Civil War. It simply changed its odious form and continued the generational enslavement of an entire strata of American society. In turn, the Civil Rights Movement struck a mighty blow against racism in America, and our souls soared when Dr. King told us he had a dream. But we were and still are far from the “promised land.” And even when America rose up to elect its first Black President, Barack Obama, we may indeed have lost ground as a collective nation along the way.

That is our legacy as Americans, and in many ways, the most hateful remnants of slavery persist in the U.S. today in the form of systemic racism baked into nearly every aspect of our society and who we are as a people. Indeed, for those tracing their heritage to countries outside of Western Europe, or for those with a non-Christian belief system, that undeniable truth often impacts every aspect of who you are as a person, in one form or another.

The reality of this history has been on stark display in recent weeks. From the terrible killings of George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery, to the countless, untold acts of racism that take place every day across America, these are the issues that are defining the moment—just as our response will define who we are and will be in the 21st century and beyond. Truly, the very nature of our “national soul” is at stake, and we all have a deep responsibility to be a part of the solution.

For us at Brookings, race, racism, equality, and equity are now matters of presidential priority. Addressing systemic racism is a key component of those efforts, with research also focusing on the Latino and Native American communities; faith-based communities, including our Jewish and Muslim communities; and the threat of white supremacy and domestic terrorism also playing a major role. It will also include work on the important need for comprehensive police reform, to include reform rooted in local community engagement and empowerment. We will not solve systemic racism and inequality over-night, and we have so much work ahead. But in a world where we often spend more time debating the nature of our problems than taking meaningful action, we must find ways to contribute however we can and to move forward as a community.

I firmly believe that we as Americans cannot remain silent about injustice. Inaction is simply unacceptable, and we have to stand up and speak out. And if our elected representatives and our elected leadership deny the problem, and refuse to act, then we must take on the responsibility of reform from the bottom up with special attention at the ballot box.

And especially for those Americans who may look like me – a white American male – or come from a similar background, action begins with reflection, and most importantly listening. It’s also about elevating and supporting the voices of those traditionally underrepresented, or even silenced, throughout society. How We Rise is an absolutely critical part of that solution.

U.S. Democracy

Race, Prosperity, and Inclusion Initiative

Gabriel R. Sanchez, A-dae Romero-Briones, Raymond Foxworth

February 15, 2024

Online Only

2:00 pm - 3:00 pm EST

Rashawn Ray

September 8, 2023

Share this via Facebook Share this via X Share this via WhatsApp Share this via Email Other ways to share Share this via LinkedIn Share this via Reddit Share this via Telegram Share this via Printer

Download the full report in English

Racial Discrimination in the United States

Human Rights Watch / ACLU Joint Submission Regarding the United States’ Record Under the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

Protesters at a rally in Minneapolis call for justice for George Floyd after closing arguments in the Derek Chauvin trial ended on April 19, 2021. © 2021 Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Introduction

The United States signed the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (“ICERD” or “Convention”) in 1966. President Lyndon Johnson’s administration noted at the time that the United States “has not always measured up to its constitutional heritage of equality for all” but that it was “on the march” toward compliance. [1] The United States finally ratified the Convention in 1994 and first reported on its progress in implementing the Convention to the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (“CERD” or “Committee”) in 2000. In August 2022, the Committee will examine the combined 10 th – 12 th periodic reports by the United States on compliance with the Convention. This report supplements the submission of the government with additional information in key areas and offers recommendations that will, if adopted, enhance the government’s ability to comply with ICERD.

In its 2000 report, the United States stated that “overt discrimination” is “less pervasive than it was thirty years ago” but admitted it continued due to “subtle forms of discrimination” that “persist[ed] in American society.” [2] The forms of discrimination reported to the United Nations by the United States included “inadequate enforcement of existing anti-discrimination laws”; “ineffective use and dissemination of data”; economic disadvantage experienced by minority groups; “persistent discrimination in employment and labour relations”; “segregation and discrimination in housing” leading to diminished educational opportunities for minorities; lack of equal access to capital, credit markets and technology; discrimination in the criminal legal system; lack of adequate access to health insurance and health care; and discrimination against immigrants, among other harmful effects. [3] The United States also noted the heightened impact of racism on women and children.

It has now been more than 50 years since the US signed the ICERD, nearly 30 years since it ratified the Convention, and more than 20 since it identified the extensive foregoing list of impediments to its effective implementation. Yet progress toward compliance remains elusive—indeed, grossly inadequate—in numerous key areas including reparative justice; discrimination in the US criminal legal system; use of force by law enforcement officials; discrimination in the regulation and enforcement of migration control; and stark disparities in the areas of economic opportunity and health care. Structural racism and xenophobia persist as powerful and pervasive forces in American society.

During his first days in office, President Joseph Biden called for urgent action to advance equity for all, calling this a “battle for the soul of [the] nation” because “systemic racism” is “corrosive,” “destructive” and “costly.” [4] As this report and its annex, jointly authored by the American Civil Liberties Union and Human Rights Watch, demonstrate, the US has a great deal of work ahead to realize the promises of the ICERD. [5] This report therefore includes important recommendations in areas in which our organizations have specialized expertise, for addressing some of the US’s most flagrant violations of the Convention. Additionally, although we recognize the political challenges facing the Biden Administration as it seeks to promote racial equity, we note that its recent declarations on racial justice are disconnected from the government’s longstanding human rights obligations under the ICERD. The attached annex therefore identifies additional, more targeted measures to align President Biden’s commitments with the ICERD. These measures are both fully within the control of the executive branch of the federal government and powerful enough to give life to the President’s stated commitment to put “every branch of the White House and the federal government” to work in the effort to “eliminate systemic racism” in the United States. [6]

President Biden has declared that racism, xenophobia, nativism, and other forms of intolerance are “global problems.” [7] The ICERD is an important part of the solution and to confront these global problems effectively, the US should fulfill its obligations under the treaty. [8] This report and its detailed annex offer an initial roadmap for the US to do exactly that.

Reparative Justice for the Legacy of Enslavement

Article 6 of the ICERD establishes the right to remedy and to seek just and adequate reparation for acts of racial discrimination such as enslavement, the many post-emancipation crimes against Black people in the United States, and the insufficiently remediated ongoing discriminatory structures. The US government has never adequately addressed the gross human rights violations perpetrated against Black people as part of chattel slavery or the exploitation, segregation, and violence unleashed on Black people that followed. The discrimination against Black people that is a legacy of enslavement persists and is perpetuated by economic, health, education, law enforcement, and housing, and other policies and practices that fail to adequately address racial disparities—part of the ongoing structural racism and racial subjugation that prevents many Black people from advancing, and facilitates police violence, housing segregation, and a lack of access to education and employment opportunities, among other things. States are obligated under the ICERD to overcome such structural discrimination, both through effective remedies—such as reparations and “special measures”—and through the Convention’s obligation to “[t]ake steps to remove all obstacles that prevent the enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights by people of African descent especially in the areas of education, housing, employment and health.” [9]

The ICERD requires States Parties to “assure to everyone within their jurisdiction effective protection and remedies, through the competent national tribunals and other State institutions, against any acts of racial discrimination” and to ensure “the right to seek from such tribunals just and adequate reparation or satisfaction for any damage suffered as a result of such discrimination.” [10] The CERD has noted that the right to seek just and adequate reparation “is not necessarily secured by the punishment of the perpetrator of the discrimination” and that “the courts and other competent authorities should consider awarding financial compensation for damage, material or moral, suffered by a victim, whenever appropriate.” [11] The UN has also established principles on the right of victims to remedies and reparations, and specifically set forth the right to reparations for people of African descent. [12] Although States generally only incur international responsibility for acts that are both internationally wrongful and attributable to the State, this principle does not apply to slavery and its legacy. [13] While the US has enacted civil rights statutes since the 1950s, such legislation has been largely ineffective at curbing structural discrimination and racial inequality because of judicial decisions that significantly undermined their scope and meager government enforcement and investment, as well as the onerous requirements of discriminatory intent instead of discriminatory effect. Further, the US has consistently indicated in its ICERD reporting that “inadequate funding” is one of the central reasons for insufficient federal enforcement. [14] The failure of the US to expand enforcement efforts and resources while acknowledging these widespread disparities over the last twenty-two years since it became a party to ICERD requires immediate redress.

Reparative intervention for historical and contemporary racial injustice is urgent and required by ICERD. [15] The deep racial harms and unequal structures that are inextricably rooted in chattel slavery remain unremedied, perpetuating systemic inequality. Scholars have estimated that the US benefited from 222,505,049 hours of forced labor between 1619 and the end of slavery in 1865, which would be valued at $97 trillion today. [16] In 1860 alone, there were four million enslaved Africans whose labor is valued at least $3 billion , [17] which was more than all the capital invested in railroads and factories in the United States combined . [18] Enslaved people were subjected to brutal forced labor as well as formal and informal state-sanctioned discrimination that resulted in severe economic damage, in addition to psychological, social and political harm. [19]

Black people in the US continue to endure severe economic disadvantages in wealth [20] and income [21] and suffer from discriminatory policies in land and home ownership, [22] denial of health care, [23] and segregation in education. [24] The resulting disparities are staggering: The average white family has roughly ten times the wealth of the average Black family and white college graduates have over seven times more wealth than Black college graduates. [25] With the current pace of growth in wealth among Black families, it will take an estimated 230 years for Black families to obtain the same amount of wealth that white families currently have. [26] About 21 percent of Black people in the United States live in poverty, more than double the rate for white people (8.8 percent). [27] Although “these wealth disparities are rooted in historic injustices and carried forward by recent and ongoing practices and policies that fail to reverse inequitable trends,” [28] to date the US government has not done nearly enough to address the lasting and contemporary racially discriminatory effects of structures of inequality and racial subordination. It has also openly admitted to failing to provide sufficient resources for civil rights enforcement even though ICERD requires restitution, compensation, and restoration. [29]

While the CERD has not yet made specific recommendations to the US with regard to reparative justice, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, in her 2021 report on systemic racism in law enforcement, urged the US (alongside other governments) to initiate reparations. [30] Although some localities have implemented reparation initiatives or commissions to address past racially motivated harms, [31] there remains no formal nationwide federal initiative to advance reparations. Neither US courts nor other tribunals have provided reliable remedies for the descendants of enslaved people. [32] H.R. 40 - Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act, a bill currently before the House of Representatives, would establish a commission to study the effects of slavery and recommend appropriate remedies. [33] But no progress has been reported as of this writing. [34] In sum, the US federal government continues to neglect its ICERD commitments to remedy the systemic, longstanding and grave legacy of enslavement and racial discrimination.

To address ongoing structural racism and legacies of enslavement, the US should:

- Establish a federal commission by legislative action or executive order to study and develop reparations proposals for the descendants of enslaved people.

- Appropriate effective resources for federal economic and civil rights programs to address long-term structural racism and provide assistance to low-wealth and low-income Black communities.

Racial Discrimination in the Criminal Legal System

Mass incarceration.

Article 2(1) of ICERD states that States Parties need to pursue the elimination of racial discrimination in all its forms. ICERD prohibits discriminatory practices and requires that States Parties “take effective measures to review governmental, national and local policies, and to amend, rescind or nullify any laws which have the effect of creating or perpetuating discrimination.” [35] Additionally, Article 5 guarantees equality before the law, including “the right to equal treatment before tribunals and all other organs administering justice”; [36] and article 6 requires states to guarantee “effective protection and remedies, through competent national tribunals,” against acts of racial discrimination. [37]

The CERD has broadly articulated that “the mere fact of belonging to a racial or ethnic group . . . is not a sufficient reason, de jure or de facto, to place a person in pretrial detention” [38] and that States should “ensure that the courts do not apply harsher punishments solely because of an accused person’s membership of a specific racial or ethnic group.” [39] Additionally, the UN, in its 2021 common position on incarceration, stated that “incarceration should be used as a last resort,” and recommended shifting to non-custodial alternatives. [40]

The CERD has repeatedly emphasized profound concerns with the US criminal legal system, first articulated in its 2001 Concluding Observations to the US, in which it noted that “the incarceration rate is particularly high with regard to African-Americans and Hispanics.” [41] It thus recommended that the US take “firm action to guarantee the right of everyone, without distinction as to race, colour, or national or ethnic origin,” to equal treatment before all organs administering justice. [42] In its most recent review, the Committee went further, expressing its concern that “members of racial and ethnic minorities, particularly African Americans, continue to be disproportionately arrested, incarcerated and subjected to harsher sentences, including life imprisonment without parole and the death penalty.” [43] It specifically recommended that the US amend “laws and policies leading to racially disparate impacts in the criminal justice system” at all levels of government and implement “effective national strategies or plans of action aimed at eliminating structural discrimination.” [44] In its 2021 submission, the US reported that the federal prison population had dropped to its lowest level since 2000, “declining almost 31% since 2013,” [45] though it is worth noting that the federal prison population only represents about 10 percent of the total US prison population. [46] Further, the federal prison population has grown under President Biden. [47] The US also cited the First Step Act, enacted by Congress in December 2018, [48] as central in making reductions possible. In its 2021 submission the US reported that of the total number of people who received reduced sentences as a result of the First Step Act, 91 percent were Black , which is consistent with the historic over-policing and overcharging of Black communities. [49] At the same time, the US failed to mention that its own Department of Justice (DOJ) found the risk assessment tool the Prisoner Assessment Tool Targeting Estimated Risk and Needs (PATTERN) created by DOJ in connection with the First Step Act, resulted in racial disparities. [50] Despite repeated attempts at reform, the tool continues to overestimate the number of Black women who will engage in recidivism, compared to white women, and produces other racial disparities. [51]

While some reforms have taken effect over the last decade, the US has failed to systematically address the immense breadth and depth of harm caused by its criminal legal system–harms that are the product of deliberate legal and policy choices created by a dominant white population supported by a culture of white supremacy. [52]

US authorities hold almost two million people in detention and correctional facilities across the United States , [53] and they imprison Black people at a rate three times higher than white people . [54] Black women are imprisoned at a rate that is 1.7 times the rate of white women. [55] While systemic discrimination against Black people is particularly blatant, the US also disproportionately punishes Indigenous [56] and Latinx [57] people.

Racial discrimination is also deeply woven into the policing and charging practices that harass, target, and subject Black people and other people of color to the most severe punishments available. One out of seven people in prison are serving a life sentence , [58] and nearly half of that group is Black. [59] US authorities continue to apply the death penalty both discriminatorily and arbitrarily.

In 2021, more than half of people executed were Black, and approximately 60% of people sentenced to death were Black or Latinx . [60] Nearly 200 people on death row have been exonerated since 1972—1 for every 8.3 people executed. [61] In fact, both death-row exonerees in 2021 were Black men imprisoned in Mississippi for nearly three decades because of false forensic testimony . [62]

Mass incarceration harms not only those incarcerated, disproportionately people of color, but entire communities. About half of adults in the US have had an immediate family member incarcerated in jail or prison. [63] Black people are 50 percent more likely to have experienced familial incarceration than whites, and they are three times as likely to have had a family member incarcerated for a year or longer . [64] Research also shows that nearly half of incarcerated people in state prisons and almost 60 percent in federal prisons are parents with minor children, [65] and Black children are six times more likely than their white peers to have had a parent behind bars . [66]

One of the most damaging aspects of mass incarceration in the United States is the harm caused to incarcerated people by dangerous and degrading conditions in prisons, jails, and other places of detention. Practices such as solitary confinement , [67] denial of adequate medical and mental healthcare , [68] and sexual and other violence [69] cause lasting injury, and sometimes death, to those exposed to them. Because of space limitations, this report does not discuss these conditions of confinement in detail, but they are an inseparable element of the harm caused by mass incarceration.

To address the discriminatory impact of mass incarceration, the US should:

- Reduce the role of police in addressing societal problems (including homelessness, mental health, and poverty) and invest instead in community-based non-carceral solutions to such societal problems.

- Abolish the death penalty and consider the elimination of life, and virtual life, sentences; eliminate sentence enhancements and minimum-time-served requirements; and expand access to early-release mechanisms such as good-time credits, parole, and clemency. These legal changes should be extended to offenses classified as violent and applied retroactively.

- Invest in crime prevention programs and alternatives to incarceration including community-based crisis intervention services that are trauma-informed, culturally competent, and do not exclude offenses classified as violent.

- Record, maintain, track, and publicly disseminate data on convictions, sentencing, and incarceration including racial and ethnic demographics.

Youth/Juvenile Justice

The ICERD requires States to “pay the greatest attention possible with a view to ensuring that [children from racial minorities] benefit from the special regime to which they are entitled in relation to the execution of sentences.” [70] Other prominent human rights bodies have reinforced this message. The Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) has stated that “particular attention must be paid to de facto discrimination and [racial] disparities” [71] and urged states to provide “appropriate support and assistance” to reintegrate young people who commit crimes. [72] In its most recent recommendations to the US, the CERD urged the US to intensify efforts to address the “school-to-prison pipeline,” ensure that young people are not placed in adult criminal settings, and abolish life-without-parole sentences for people under eighteen. [73]

Racial inequities pervade every stage of the juvenile legal system. Black and brown young people are more likely than their white peers to be stopped and harassed by the police. [74] This increases the likelihood of future arrest: Black young people who come into contact with the police by eighth grade have eleven times greater odds of being arrested in young adulthood. [75] Once arrested, Black young people are four times as likely to be detained as white young people. [76] Black young people comprise just fifteen percent of the US youth population, but forty-one percent of those confined in juvenile facilities. [77] Black children are also disproportionately likely to be charged as adults. [78] Indeed, eighty percent of young people serving life sentences are children of color, and more than fifty percent are Black. [79] The traumas of incarceration—which are especially acute for children in adult prisons and include sexual abuse, solitary confinement, and death by suicide—therefore fall too often on children of color, especially Black youth. [80]

To address the discriminatory impact of policies criminalizing youth:

- Provide supportive services for and investment in child-centered, trauma informed youth programs, education, and mental health care.

- Refrain from prosecuting children in adult court, utilizing incarceration as a last resort after other interventions have been tried, and instead treat them as children, with a focus on opportunities for education, healing, and healthy development instead of punishment.

Criminalization of Poverty – Homelessness, Bail, Fines, and Fees

Beyond the general requirement that “all public authorities and public institutions, national and local” eschew racial discrimination, [81] the ICERD contains provisions that bear specifically on homelessness and poverty. Article 5(e) of the Convention addresses discrimination in protections against unemployment and the provision of social security and social services. [82] Additionally, Article 5(f) articulates a “right of access to any place or service intended for use by the general public.” [83] In 2014, the CERD expressed concern over the “high number of homeless persons, who are disproportionately from racial and ethnic minorities,” and the “criminalization of homelessness through laws that prohibit activities such as loitering, camping, begging and lying down in public spaces.” [84] The Committee recommended abolishing laws criminalizing homelessness, and “intensify[ing] efforts to find solutions for the homeless, in accordance with human rights standards.” [85]

Although the US has previously acknowledged the CERD’s concerns, [86] the criminalization of homelessness remains a pressing social problem across the United States—and one that continues to burden people of color disproportionately. In 2020, there were an estimated 580,000 unhoused people in the United States, 39 percent of whom were Black, despite only being 12 percent of the US total population. [87] Fifty-three percent of unhoused families with children were Black. Native American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander people made up 1 percent of the US population, but 5 percent of the unhoused. [88] Many localities persist in criminalizing the presence of homeless persons in public places [89] —in essence, punishing people for lacking a home by prohibiting sleeping outside, loitering, or requesting assistance from others. [90] For instance, in one town near Los Angeles, California, only 1.3 percent of the population is homeless, but that group received a staggering 26% of all citations issued in the town by the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department. [91] Zealous targeting of homeless populations essentially for being homeless inexorably feeds a vicious cycle of escalating enforcement, generating misdemeanors, warrants, unpayable fines, and incarceration. [92] The criminalization of homelessness now includes arrests, citations, and forced banishment of people through encampment clearances and property destruction by sanitation workers and police. [93] In cities like Los Angeles as well as elsewhere in the US, a long history of racial discrimination in housing, lending, employment, policing, and other factors (government policies like “urban renewal” and freeway construction included) have led to high levels of Black homelessness. [94]

Poverty implicates issues of concern to CERD outside the context of homelessness as well. The US has conceded that, within the criminal legal system, some rights are contingent upon ability to pay. Although variation occurs across US states, the US has noted that “persons with felony convictions may … have to pay any outstanding fees, fines, or restitution before [voting] rights are restored” upon release from incarceration. [95] While this statement indicates some recognition of the problem, the federal government’s current actions are inadequate to remedy the immense harm to poor individuals stemming from the criminal legal system, a system that keeps the already marginalized in poverty. [96] In its most recent response to the CERD, the US fails to address the crushing effects of fines and fees accompanying low-level infractions, the accumulation of which affect the poorest in society, who pay the vast majority of these penalties. [97] A study in Tulsa, Oklahoma found that Black residents were disproportionately subject to county-based warrants that are often issued for minor infractions such as failure to pay court costs, fines, and fees. [98] The threat of rearrest for one’s inability to afford mounting debt keeps people in a cycle of incarceration and forces families to decide between paying fines and fees and purchasing necessities such as diapers and formula for their children. [99] Mothers are separated for lengthy periods of time from their children as a result of being held in custody, sometimes lengthened due to the fines and fees. [100]

Furthermore, pretrial incarceration, often ordered by judges setting unaffordable money bail, disproportionately harms low-income and low-wealth people of color. In the case of bail, wealthy defendants are more able to secure their freedom while poor ones are forced to remain incarcerated, affecting their livelihoods and family ties. [101] Pretrial incarceration leads to increased likelihood of convictions and harsher sentences. [102] People held in jail pretrial are pressured to plead guilty to secure their release, regardless of their actual guilt or innocence. [103] Additionally, pretrial incarceration can result in even more fines and fees, as some jails bill detained people for each day of their detention. [104] These inequalities have troubling racial implications, as Black people are 2.5 times more likely than white people to live in poverty and face much higher arrest rates. [105]

To address the criminalization of poverty, US states should:

- Stop criminalizing homelessness and its inevitable consequences, which only further serves to penalize disadvantaged individuals already suffering from inadequate allocation of governmental resources.

- Reduce the circumstances in which courts can order pretrial incarceration, through bail setting or other means, only to those in which there is strong evidence of imminent harm if a person is released pretrial, and only following a rigorous hearing to evaluate that evidence.

- Invest in pretrial services programs providing court date reminders, transportation, and other support to ensure court appearances.

- Drastically reduce the number and amounts of fines and fees in the US criminal legal system. Further, establish national standards for criminal-legal system debt, including guidelines on ability- to- pay determinations and collection practices.

Probation and Parole

Probation and parole are portrayed as alternatives to incarceration, but in reality they drive high numbers of people—particularly Black and brown people—into jail and prison. [106] About 4 million people in the US are on probation or parole, [107] and nearly half of all state prison admissions stem from violations of the conditions of probation or parole. [108] Black people are 4.15 times more likely to be under supervision than white people, and remain on supervision longer than similarly situated whites. [109]

Black people are also more likely to be incarcerated for supervision violations. Due to generations of structural racism, Black and brown people are less likely to have resources, such as housing, wealth, reliable transportation, and jobs, that make it feasible to complete the onerous requirements of supervision. [110] Meanwhile, they are disproportionately stopped, searched, and arrested by police—making them more likely to be incarcerated for probation or parole violations. [111] And some supervision conditions—such as requirements to stay away from people with felony records—disproportionately burden Black men, one in three of whom have a felony conviction. [112]

To address racial disparities in probation and parole, US authorities should:

- Drastically reduce the use of supervision sentences for youth and adults and instead utilize real alternatives to incarceration.

- Where supervision is used, shorten supervision periods, narrowly tailor conditions, and stop incarcerating people for violations that would not otherwise be a crime.

Reentry Issues – Impact of Criminal Records on Housing and Unemployment

The ICERD requires States to take “special and concrete measures to ensure the adequate development and protection of certain racial groups or individuals belonging to them, for the purpose of guaranteeing them the full and equal enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms,” [113] including the right to work and the right to housing. [114] The Committee has raised concerns about persistent housing and employment racial disparities in the US. [115]

The United States imposes more than 48,000 legal restrictions on people with criminal records—barring them from work, housing, jobs, and civic engagement. [116] These barriers disproportionately impact Black and brown people, who are more likely to have criminal records [117] and to face discrimination when attempting to access housing and employment. [118] Sixty-four percent of unemployed men in their thirties have criminal records, and Black men are almost twice as likely as white men to be unemployed. [119]

Additionally, the high rate at which the US subjects Black people to correctional control results in their underrepresentation in the US electorate, as many US jurisdictions deny voting rights to people on probation and parole, and nearly all deny those rights to people in prison. [120]

To address racial discrimination in re-entry, US jurisdictions should:

- Repeal US laws allowing and facilitating discrimination and/or exclusions based solely on an individual’s arrest or conviction, including restrictions or exclusions from employment, housing, access to social benefits, and voting.

Racist Drug Laws and Racism in Public Health Approaches

The ICERD guarantees the right to equal treatment generally and, under Article 2(c), requires States Parties to “take effective measures to review governmental, national and local policies, and to amend, rescind or nullify any laws and regulations that have the effect of creating or perpetuating racial discrimination wherever it exists.” [121] In its General Recommendation XXXI, the CERD recommended that States “pay the greatest attention” to “proportionately higher crime rates attributed to persons belonging to [racial minorities], particularly as regards petty street crime and offenses related to drugs” as an indication of the “non-integration of such persons into society.” [122] Additionally, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) has called for the “decriminalization of drug possession for personal use” and the “elimination of stigma and discrimination against people who use drugs.” [123] In its 2014 concluding observations to the US, the CERD expressed concern over “the application of mandatory minimum drug-offense sentencing policies” that exacerbate racial disparities in the criminal legal system. [124] Additionally, the UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights highlighted the “confused and counterproductive drug policies” in the US in his 2018 country report. The report described how, in the context of drug addiction in the US, the “main responses have been punitive,” rather than the appropriate response of “increased funding and improved access to vital care and support.” [125] The report further suggested that this “urge to punish” has “racial undertones,” noting the disparities in sentencing between Black users of crack cocaine and white users of opioids. [126] Similarly, the UN Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent has urged the US to amend any judicial policies that disproportionately target Black people, stating that “the war on drugs has operated more effectively as a system of racial control than as a mechanism for combating the use or trafficking of narcotics.” [127]

In its 2021 report to the CERD, the US pointed to the 2018 enactment of the First Step Act, a law that reduced racial disparities in sentences for certain drug crimes. [128] While these reforms are helpful, they do not do nearly enough to remedy past discriminatory treatment or change laws, policies and practices in ways that would prevent it in the future.