Slavery, Abolition, Emancipation and Freedom

- Explore the Collection

- Collections in Context

- Teaching the Collection

- Advanced Collection Research

Reconstruction, 1865-1877

Donald Brown, Harvard University, G6, English PhD Candidate

No period in American history has had more wide-reaching implications than Reconstruction. However, white supremacist mythologies about those contentious years from 1865-1877 reigned supreme both inside and outside the academy until the 1960s. Columbia University’s now-infamous Dunning School (1900-1930) epitomizes the dominant narrative regarding Reconstruction for over half of the twentieth century. From their point of view, Reconstruction was a tragic period of American history in which vengeful White Northern radicals took over the South. In order to punish the White Southerners they had just defeated in the Civil War, these Radical Republicans gave ignorant freedmen the right to vote. This resulted in at least 2,000 elected Black officeholders, including two United States senators and 21 representatives. In order to discredit the sweeping changes taking place across the American South, conservative historians argued this period was full of corruption and disorder and proved that Black Americans were not fit to leadership or citizenship.

Thanks to the work of a number of Black and leftist historians—most notably John Roy Lynch, W.E.B. Du Bois, Willie Lee Rose, and Eric Foner—that negative depiction of Reconstruction is being overturned. As Du Bois famously wrote in Black Reconstruction in America (1935), this was a time in which “the slave went free; stood for a brief moment in the sun; and then moved back again toward slavery.” During that short time in the sun, underfunded biracial state governments taxed big planters to pay for education, healthcare, and roads that benefited everyone. There is still much more to be unpacked from this rich period of American history, and Houghton Library contains a wealth of material to further buttress new narratives of that era.

Reconstructing Reconstruction

While some academics, like those of the Dunning School, interpreted Reconstruction as doomed to failure, in the years immediately following the Civil War there were many Americans, Black and White, who saw the radical reforms as being sabotaged from the outset. Writer and civil rights activist Albion W. Tourgée published his best selling novel Bricks Without Straw in 1880. Unlike most White authors at the time, Tourgée centered Black characters in his novel, showing how the recently emancipated were faced with violence and political oppression in spite of their attempts to be equal citizens.

In this period, two of the most iconic amendments were implemented. The Fourteenth Amendment ratified several crucial civil rights clauses. The natural born citizenship clause overturned the 1857 supreme court case, Dred Scott v. Sandford , which stated that descendants of African slaves could not be citizens of the United States. The equal protection clause ensured formerly enslaved persons crucial legal rights and validated the equality provisions contained in the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Even though many of these clauses were cleverly disregarded by numerous states once Reconstruction ended, particularly in the Deep South, the equal protection clause was the basis of the NAACP’s victory in the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). The Fifteenth Amendment guaranteed another important civil right: the right to vote. No longer could any state discriminate on the basis of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. At Houghton, we have proof of the exhilarating response Black Americans had to the momentous progress they worked so hard to bring about: Nashvillians organized a Fifteenth Amendment Celebration on May 4, 1870. And once again, during the classical period of the Civil Rights Movement, leaders appealed to this amendment to make their case for what became the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The Reign of Kings Alpha and Abadon

Lorenzo D. Blackson's fantastical allegory novel, The Rise and Progress of the Kingdoms of Light & Darkness ; Reign of Kings Alpha and Abadon (1867), is one of the most ambitious creative efforts of Black authors during Reconstruction. A Protestant religious allegory in the lineage of John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress , Blackson's novel follows his vision of a holy war between good and evil, showing slavery and racial oppression on the side of evil King Abadon and Protestant abolitionists and freemen on the side of good King Alpha. The combination of fantasy holy war, religious pedagogy, and Reconstruction era optimism provide a unique insight to one contemporary Black perspective on the time.

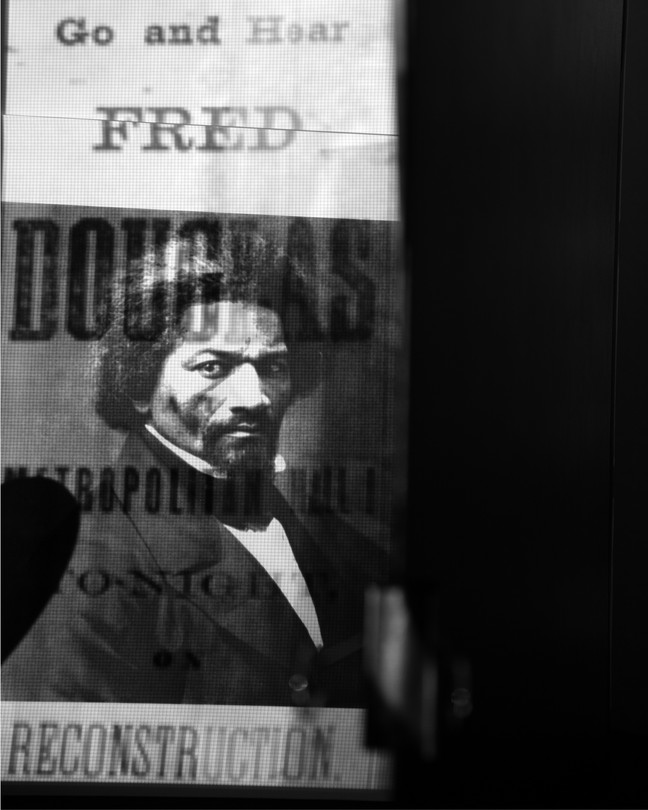

It is important to emphasize that these radical policy initiatives were set by Black Americans themselves. It was, in fact, from formerly enslaved persons, not those who formerly enslaved them, that the most robust notions of freedom were imagined and enacted. With the help of the nation’s first civil rights president, Ulysses S. Grant (1869-1877), and Radical Republicans, such as Benjamin Franklin Wade and Thaddeus Stevens, substantial strides in racial advancement were made in those short twelve years. Houghton Library is home to a wide array of examples of said advancement, such as a letter written in 1855 by Frederick Douglass to Charles Sumner, the nation’s leading abolitionist. In it, he argues that Black Americans, not White abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison, founded the antislavery movement. That being said, Douglass was appreciative of allies, such as President Grant, of whom he said: “in him the Negro found a protector, the Indian a friend, a vanquished foe a brother, an imperiled nation a savior.” Houghton Library also houses an extraordinary letter dated December 1, 1876 from Sojourner Truth , famous abolitionist and women’s rights activist, who could neither read nor write. She had someone help steady her hand so she could provide a signed letter to a fan, and promised to also send her supporter an autobiography, Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Bondswoman of Olden Time, Emancipated by the New York Legislature in the Early Part of the Present Century: with a History of Her Labors and Correspondence.

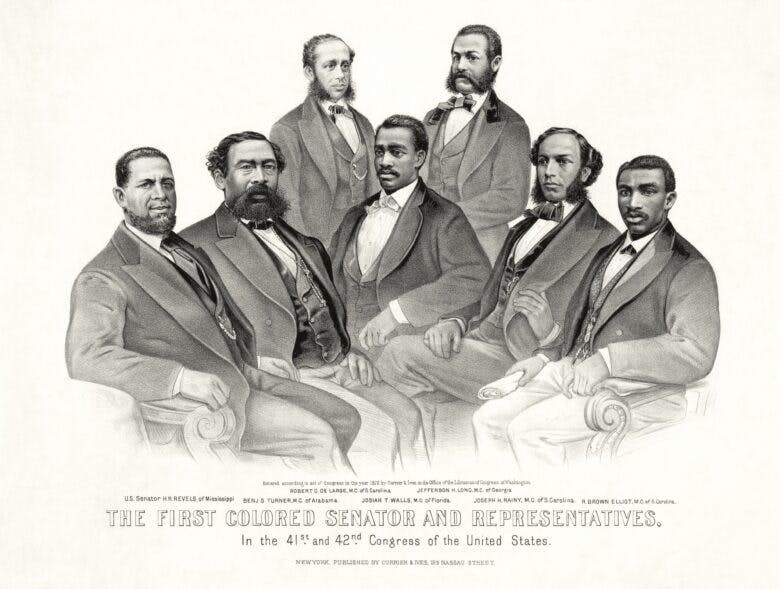

In this hopeful time, Black Americans, primarily located in the South, were determined to use their demographic power to demand their right to a portion of the wealth and property their labor had created. In states like South Carolina and Mississippi, which were majority Black at the time, and Louisiana , Alabama, and Georgia , with Black Americans consisting of nearly half of the population, the United States elected its first Black U.S. congressmen. Now that Black Southern men had the power to vote, they eagerly elected Black men to represent their best interests. Jefferson Franklin Long (U.S. congressman from Georgia), Joseph Hayne Rainey (U.S. congressman from South Carolina), and Hiram Rhodes Revels (Mississippi U.S. Senator) all took office in the 41st Congress (1869-1871). These elected officials were memorialized in a lithograph by popular firm Currier and Ives. Other federal agencies, such as the Freedmen’s Bureau , also assisted Black Americans build businesses, churches, and schools; own land and cultivate crops; and more generally establish cultural and economic autonomy. As Frederick Douglass wrote in 1870, “at last, at last the black man has a future.”

Black Americans quickly took full advantage of their newfound freedom in a myriad of ways. Alfred Islay Walden’s story is a particularly remarkable example of this. Born a slave in Randolph County, North Carolina, he only gained freedom after Emancipation. He traveled by foot to Washington, D.C. and made a living selling poems and giving lectures across the Northeast. He also attended school at Howard University on scholarship, graduating in 1876, and used that formal education to establish a mission school and become one of the first Black graduates of New Brunswick Theological Seminary. Walden’s Miscellaneous Poems, Which The Author Desires to Dedicate to The Cause of Education and Humanity (1872) celebrates the “Impeachment of President Johnson,” one of the most racist presidents in American history; “The Election of Mayor Bowen,” a Radical Republican mayor of Washington, D.C. (Sayles Jenks Bowen); and Walden’s own religious convictions, such as in “Jesus my Friend;” among other topics.

Black newspapers quickly emerged during Reconstruction as well, such as the Colored Representative , a Black newspaper based in Lexington, KY in the 1870s. As editor George B. Thomas wrote in an “Extra,” dated May 25, 1871 : “We want all the arts and fashions of the North, East and Western states, for the benefit of the colored people. They cannot know what is going on, unless they read our paper.... Now, we want everything that is a benefit to our colored people. Speeches, debates, and sermons will be published.”

Reconstruction proves that Black people, when not impeded by structural barriers, are enthusiastic civic participants. Houghton houses rich archival material on Black Americans advocating for civil rights in Vicksburg, Mississippi , Little Rock, Arkansas , and Atlanta, Georgia , among other states, in the forms of state Colored Conventions and powerful political speeches . For anyone interested in the long history of the Civil Rights Movement, these holdings are a treasure trove waiting to be mined. Though the moment in the sun was brief, the heat exuded during Reconstruction left a deep impact on progressive Americans and will continue to provide an exemplary political model for generations to come.

In short, the South was effectively brought into a national system of credit and labor as a result of Reconstruction. “Free” labor, rather than some system of coerced labor would prevail in the region. Neither serfdom nor peasantry would replace slavery. And southern landowners and freedmen, whether they wanted to or not, were incorporated into the national credit markets.

Let us now take stock of the answers to the questions that we began with. On what terms would the nation be reunited? In short, on national terms. Property was not expropriated or redistributed in the South. Reforms that were imposed on the South—the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, for example—applied to the entire nation.

What implications did the Civil War have for citizenship? The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments represented stunning expansions of the rights of citizenship to former slaves. Even during the depths of the Jim Crow era in the early twentieth century, white supremacists never succeeded in returning citizenship to its pre-Civil War boundaries. African Americans especially insisted that they may have been deprived of their rights after the Civil War but they had neither surrendered nor lost their claim to those rights.

What would be the future of the restored nation’s economy? In simplest terms, Abraham Lincoln’s famous observation that a house divided cannot stand was translated into policy. However impoverished and credit starved, the former Confederacy was integrated back into the national economy , laying the foundation for the future emergence of the most dynamic industrial economy in the world. African Americans would not be enslaved or assigned to a separate economic status. But nor would African Americans as a group be provided with any resources with which to compete.

Guiding Student Discussion

Possible student perceptions of Reconstruction Aside from the challenge of organizing the complex events of the Reconstruction era into a narrative accessible to students, the biggest challenge is to help students understand what was possible and what was not possible after the Civil War. Students, for example, may be inclined to believe that white Americans were never committed to racial equality in the first place so Reconstruction was doomed to failure. Some students may fixate on northern white hypocrisy; many white Republicans pressured southern voters to pass the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments even while they opposed its passage in the North. Yet others may emphasize that citizenship rights for blacks were hollow because blacks had no economic resources; blacks in postwar America could not easily escape an economic system that was slavery by another name. Each of these positions is worth discussion, but each tends to flatten out the motivations and behavior of the actors in the drama of Reconstruction. And virtually all of these interpretations presumed that the outcome of Reconstruction was both inevitable and wholly outside the hands of African Americans.

Ask students to design their own version of Reconstruction. One approach that I have adopted in hopes of countering these tendencies is to ask students to state their “first principles” that they think Reconstruction should have pursued and established. If your students are like mine, many will propose that Reconstruction should have guaranteed equal rights for all Americans. I then ask them to define what those rights should have been. At this point, even students who are in broad agreement about the principle of equal rights for all Americans may differ on the specific content of those rights. For example, some may stress economic equality whereas others may emphasize equality of opportunity. In any case, the next step is to ask the students to think about how they would have turned their principle into policy. Those students who may have stressed economic equality may then sketch out a plan for “forty acres and mule” for each former slave. Those who stress the need for equal opportunity may sketch out the need for public education for freed people and other southerners. I next ask students where the requisite resources for these policies would come from. For example, where would the federal government have gotten the land and money to provide former slaves with land and livestock? If the federal government had expropriated land and resources from former slave masters, what consequences would that policy have had for private property elsewhere in the United States? (If the government could take lake and property from former slave masters, would it then have had precedent to later take land and property from former slaves?) What would the consequences of this policy have been for the production of cotton, the nation’s most important export? In response to students who propose universal public education, I ask them about the funding for these new schools. Who would pay for them? If taxes needed to be raised, what and whom should have been taxed? Should the schools have been integrated? If so, how would the resistance of white southerners to integrated schools be overcome? If not, would separate schools for blacks and white have legitimized segregation ?

Through this exercise, students gain a better sense of how all of the facets of Reconstruction were interrelated and how any broad principle was shaped by the circumstances, constraints, and traditions of the age. Equally important, students will better appreciate how astute African Americans were in pursuing their goals during the Reconstruction era. They recognized that the Civil War had ended slavery and destroyed the antebellum South, but it had not created a clean slate on which they had a free hand to write their future. Instead, black Americans were constantly gauging what was possible and who they might ally with to translate their long-suppressed hopes into a secure and rewarding future in American society.

The role of African Americans in Reconstruction The search by African Americans for allies during Reconstruction is the focus of another worthwhile exercise. It is essential for students to understand that African Americans were active participants in Reconstruction. They were not the dupes of northern politicians. Nor were they cowed by southern whites. This said, African Americans never had decisive control over Reconstruction. Whatever their goals, they needed allies. With that fundamental reality in mind, Ask students to identify the major stakeholders in Reconstruction. I ask students to draw up a list of the groups in American society who had a major stake/role in Reconstruction. Typically, students will identify the major actors as white northerners, white southerners and blacks. I then press the students to break those groups down further. Were all white northerners alike in their attitudes toward blacks? Were all white southerners? And were there any sub-groups of African Americans that should be distinguished? After this revision, my students typically distinguish between pro- and anti-black white northerners, elite white southerners, middling white southerners, blacks who were free before the Civil War, and recently freed slaves .

Once we have identified the actors in Reconstruction, we then systematically work thorough this list and consider what interests each of these groups might have shared. Put another way, on what grounds could each (any) of these groups found common cause with African Americans? Take middling whites for example. Many students may wonder why poor white southerners did not forge an alliance with former slaves. After all, they had poverty in common. Some students might suggest that poor whites refused to acknowledge their common condition with African Americans because of racism; a poor white man, in short, may have been poor but he could insist that at least he was a member of the “superior” white race. I also point out that poor whites and poor blacks may both have been poor, but they were poor in very different ways so that they were at best tentative allies. Poor whites typically were land poor; that is, they owned land but usually not the other resources that would have allowed them to exploit their land intensively. Black southerners were poor and landless; most had no significant holding of land to exploit. Consequently, when blacks called for expanded social services such as schools to meet their needs, they were implicitly calling for additional taxes to fund the services. What would be taxed to fund these new schools and services? In the nineteenth century, tangible property, and specifically land, was the principal taxed property. Taxes on the land of poor whites, then, helped to underwrite new schools in the Reconstruction South. These taxes, in the end, drove a wedge between poor whites and African Americans and ensured that black southerners could not take for granted the support of poor white southerners who bridled at paying taxes on their land to fund new schools. Or take the example of white northerners. Even some white Republicans who were unsettled by calls for racial equality could be allies of former slaves. Republicans believed that without the support of black voters in the South their party might surrender national power to the Democratic Party. Expediency alone, then, coaxed some white Republicans to support political rights for blacks. But as soon as the Republican Party garnered a sufficient national majority so that the support of southern blacks was no longer essential, these same northern Republicans urged the party to jettison its pledge to defend African American rights.

This exercise helps students see African Americans as actors in Reconstruction, but actors constrained by the actions of other actors. This exercise turns Reconstruction into a dynamic process of contestation, negotiation, and compromise, which, of course, is precisely what Reconstruction was.

What resources did the formerly enslaved bring to freedom? Finally, another possible approach is to focus students’ attention on the resources that African Americans could tap as they made the transition from slavery to freedom. I ask students to consider the needs that African Americans, as free Americans, had in 1865 and the resources they had at their disposal to allow them to survive as free Americans. This exercise prompts students to consider the resources and institutions that blacks already possessed in 1865 as well as those that blacks would subsequently need to build. In other words, many slaves possessed skills (some could read, some were skilled artisans) and had built institutions (particularly religious institutions ) that were foundations for black communities after emancipation. Taking these into account, students can then consider what additional resources former slaves needed and how they might have acquired these resources. This approach to Reconstruction inevitably leads to discussion of the possibilities and limits of black self-help as well as the prospects for meaningful assistance to blacks from white Americans. It also often leads to valuable discussions of the merits and drawbacks of the racially exclusive institutions that emerged during Reconstruction, such as schools and churches. Students gain a better appreciation, for example, of why blacks preferred schools taught by black teachers and black denominations even while students also recognize the subsequent vulnerability of these institutions.

Historians Debate

No era of American history has produced hotter scholarly debates than Reconstruction. Historians may have written more about the Civil War but they have argued louder and longer about Reconstruction. With a few notable exceptions, however, most of the scholarship on Reconstruction from the late nineteenth century to the 1960s ignored or denied the prominent role of African Americans in the era’s events. Blacks were rendered as the pawns and playthings of whites, whether they be white northerners or southerners. The most notable exception to this willful silence about blacks and Reconstruction was W. E. B. Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction (1935). Du Bois dissented from the then current interpretation of Reconstruction as a failed experiment in social engineering by placing the former slaves and the battle over the control of their labor at the center of his story. For him, Reconstruction was a failure not because blacks were unworthy of it but because white southerners and their northern allies sabotaged it. Not until the 1960s did a new generation of professional historians begin to reach similar conclusions. Spurred on by the civil rights struggle , which was commonly referred to as the “Second Reconstruction,” historians systematically studied all phases of Reconstruction. In the process, they fundamentally revised the portrait of African Americans. John Hope Franklin, in Reconstruction , Kenneth Stampp, in Era of Reconstruction , and others recast African Americans and their Republican allies as principled and progressive minded. By the 1970s, a subsequent wave of scholarship began to revise the largely positive take on the Reconstruction offered by Franklin, Stampp, et. al. Now Reconstruction was seen as an era marked by muddled policies, inadequate resources, and faltering commitment. William Gillette’s Retreat from Reconstruction (1979) was the fullest expression of this interpretation. Eric Foner’s Reconstruction synthesized the previous quarter century of scholarship on the period and offered the richest account yet of the role of African Americans in shaping Reconstruction. Foner also placed the accomplishments of Reconstruction in a comparative framework and concluded that the rights that the former slaves acquired during the era were exceptional when compared to those in any other post-emancipation society in the western hemisphere. Reconstruction may have left the former slaves with “nothing but freedom” but that freedom, Foner stressed, was written into the Constitution and was never completely compromised.

Since the publication of Foner’s work, most scholarship on Reconstruction has been devoted to topics that had previously been ignored by scholars. For example, the roles of black women , the struggle to develop a system of labor to replace slavery, and the emergence of black institutions have all been the focus of recent scholarly monographs. Two recent works that build on these works and suggest new directions for scholarship on Reconstruction are Heather Cox Richardson’s West From Appomattox: The Reconstruction of America after the Civil War (2007) and Steve Hahn’s A Nation Under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South, From Slavery to the Great Migration . Richardson highlights the importance of the Trans-Mississippi West in the political machinations and economic visions of the architects of Reconstruction while Hahn highlights the shared ideological values and cultural resources that sustained southern blacks in their struggle for economic and political power in the postbellum South.

W. Fitzhugh Brundage was a Fellow at the National Humanities Center in 1995-96. He is the William B. Umstead Professor of History at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Illustration credits

To cite this essay: Brundage, W. Fitzhugh. “Reconstruction and the Formerly Enslaved.” Freedom’s Story, TeacherServe©. National Humanities Center. DATE YOU ACCESSED ESSAY. <https://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/freedom/1865-1917/essays/reconstruction.htm>

NHC Home | TeacherServe | Divining America | Nature Transformed | Freedom’s Story About Us | Site Guide | Contact | Search

TeacherServe® Home Page National Humanities Center 7 Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256 Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709 Phone: (919) 549-0661 Fax: (919) 990-8535 Copyright © National Humanities Center. All rights reserved. Revised: May 2010 nationalhumanitiescenter.org

Introductory Essay: The Lost Promise of Reconstruction and Rise of Jim Crow, 1860-1896

To what extent did Founding principles of liberty, equality, and justice become a reality for African Americans from Reconstruction to the end of the nineteenth century?

- I can explain how the Reconstruction Amendments and federal laws sought to protect the rights of African Americans after the Civil War.

- I can identify examples of Jim Crow laws and explain how these laws undermined the rights of African Americans.

- I can explain how violence and intimidation were used to threaten African Americans from exercising their political and civil rights.

- I can analyze Reconstruction’s effectiveness in ensuring the faithful application of Founding principles of liberty, equality, and justice to African Americans.

- I can explain the various ways that African American leaders and intellectuals supported their communities and worked to end segregation and racism.

Essential Vocabulary

The lost promise of reconstruction and rise of jim crow, 1860-1896.

After more than two centuries, race-based chattel slavery was abolished during the Civil War. The long struggle for emancipation finally ended thanks to constitutional reform and the joint efforts of Black and white Americans fighting for Black freedom. The next 30 years, however, were a constant struggle to preserve the freedom achieved through emancipation and to ensure for Blacks the equality and justice of U.S. citizens in the face of opposition, violence, and various forms of discrimination.

The Civil War created conditions for the demise of slavery. Early in the war, Congress passed two Confiscation Acts that allowed the federal government to seize and later free enslaved persons in conquered Confederate territory. On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln used his wartime executive powers to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. Enslaved persons ran away from their owners and joined free Blacks enlisting in the Union Army to fight for freedom and human equality. The 54th Massachusetts Regiment was the most famous Black unit to fight in the war, but almost 200,000 Black soldiers fought for the Union. Black abolitionists joined the cause, with Harriet Tubman joining Union raids that helped liberate enslaved persons and Frederick Douglass recruiting Black troops. By the end of 1865, the requisite number of states had ratified the Thirteenth Amendment to confirm the end of slavery.

Slavery may have been banned, but Black Americans faced an uncertain future during the process of restoring the Union, called Reconstruction . The Civil Rights Act of 1866 protected basic rights of citizenship, and the Fourteenth Amendment (1868) provided for Black U.S. citizenship and equal protection under the law. Congress established the Freedmen’s Bureau as a federal agency in order to give practical help to freed people in the form of immediate aid and economic and educational opportunities. The efforts of the Freedmen’s Bureau to grant Blacks confiscated land and open Black schools in the South were frustrated by President Andrew Johnson’s vetoes of the Bureau bill and by the opposition of white supremacists.

Storming Fort Wagner by Kurz & Allison, 1890

This print shows soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment attacking the walls of Fort Wagner on Morris Island, South Carolina. The Massachusetts 54th was one of the first African American Union regiments formed in the Civil War. The regiment fought valiantly during the attack on Fort Wagner while suffering nearly 40 percent casualties. The bravery and sacrifice of the 54th became one of the most famous and inspirational parts of the Civil War.

Johnson succeeded Lincoln, and while he supported the restoration of the national union, he impeded the protection of equal rights for Black Americans. He vetoed numerous laws intended to promote Black equality, including the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the extension of the Freedmen’s Bureau, the Reconstruction Acts, and the Tenure of Office Act, among several others. While Congress overrode most of his vetoes, Johnson proved himself a consistent opponent of Black rights. In his third annual message in December 1867, he asserted, “Negroes have shown less capacity for government than any other race of people. No independent government of any form has ever been successful in their hands.” When he fired Secretary of War Edwin Stanton for resisting his policies, Congress impeached President Johnson, but the vote to remove him from office failed by one vote.

Initial protections for Blacks were also weakened by restrictions and opposition to equal civil rights. The new constitutions of former Confederate states did not protect Black citizenship or suffrage. Indeed, the states passed Black Codes that severely curtailed the legal and economic rights of Black citizens. Moreover, the codes penalized Blacks unfairly for committing the same crimes as whites.

The Union As It Was by Thomas Nast, 1874

Klan violence was documented in the press. “The Union as It Was,” an 1874 Harper’s Weekly cartoon by Thomas Nast, shows a Klan member and a White League member shaking hands over an African American family huddled together in fear. A schoolhouse burns and a man is lynched in the background.

Black Americans were also the victims of horrific violence perpetrated by white mobs and local authorities. White supremacists killed thousands of Blacks to intimidate them, prevent them from voting, and stop them from exercising their rights. The Ku Klux Klan and other groups such as the White League were organized to terrorize Blacks and keep them in a constant state of fear. The Colfax Massacre of 1873 and mass killings in places like Memphis and New Orleans were only a few examples of the wave of violence Black Americans suffered. Black and white leaders wrote to state and national officials about the violence in their communities. Congress, with the support of President Ulysses S. Grant, passed several acts aimed at protecting freed people from politically motivated violence. Such enforcement legislation was quickly challenged in the courts, and the withdrawal of all federal troops from the South in 1876 effectively ended federal intervention on behalf of the rights of freed people.

The first Black senator and representatives – in the 41st and 42nd Congress of the United States by Currier and Ives, 1872

This 1872 lithograph by Currier and Ives depicts several of the African American men who served in Congress.

Left to right: Senator Hiram Revels (MS), Representatives Benjamin Turner (AL), Robert DeLarge (SC), Josiah Walls (FL), Jefferson Long (GA), Joseph Rainey (SC), and Robert Elliott (SC).

In 1870, the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment protected the right of Black male suffrage when it banned states from denying voting rights on the basis of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Despite violence and intimidation, Blacks exercised their right to vote and served in local offices, state legislatures, and Congress. During Reconstruction, 14 African Americans served in the House of Representatives and 2 in the Senate. Nine of these leaders had been born enslaved. Local governments, however, increasingly found ways to subvert the exercise of the constitutional right to vote. Grandfather clauses , poll taxes , and literacy tests were applied to prevent Blacks from voting.

Many southern Blacks were farmers who lived under the crushing economic burdens of the sharecropping system, which forced them into a state of peonage in which they had little control over their economic destinies. In this system, white landowners rented land, tools, seed, livestock, and housing to laborers in exchange for a significant portion of the crop. As a result, Blacks barely earned a living and suffered perpetual debt that limited their economic prospects for the future.

In the later decades of the nineteenth century, Blacks also lived under confining social constraints that effectively made them second-class citizens. Segregation laws legally separated the races in public facilities, including trains, schools, churches, and hotels. These “ Jim Crow ” laws humiliated Blacks with a public badge of inferiority. Black members of Congress Robert B. Elliott and James T. Rapier made eloquent speeches in support of legislation to protect African Americans’ civil rights. Congress passed a Civil Rights Act in 1875 that protected equal access to public facilities, but the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional in the Civil Rights Cases (1883), arguing that while states could not engage in discriminatory actions, the law incorrectly tried to regulate private acts. Frederick Douglass called the decision an “utter and flagrant disregard of the objects and intentions of the National legislature by which it was enacted, and of the rights plainly secured by the Constitution.” In 1896, however, the Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that segregation laws were constitutional if local and state governments provided Blacks with “separate but equal” facilities. Separate was never equal, particularly in the eyes of Black Americans.

Watch this BRI Homework Help video for a review of the Plessy v. Ferguson case.

Blacks endured escalating violence in the Jim Crow era of the 1890s. White mobs of the time lynched more than 100 Blacks a year. Lynching was summary execution by angry mobs in which the victim was tortured and killed and the body mutilated. Ida B. Wells was a courageous Black journalist who cataloged the horrors of almost 250 lynchings in two pamphlets, A Red Record: Lynchings in the United States and Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases . Despite her efforts, lynching of Black Americans continued into the twentieth century.

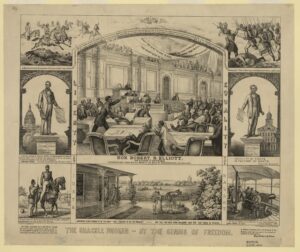

The shackle broken by the genius of freedom by E. Sachse & Co., 1874

This 1874 lithograph, “The shackle broken by the genius of freedom,” memorialized Congressional representative Robert B. Elliott’s famous speech in favor of the 1875 Civil Rights Act. Elliott is shown in the center of the image, while the banner at the top contains a quotation from his speech: “What you give to one class you must give to all. What you deny to one you deny to all.”

Black leaders and intellectuals like Wells, Douglass, Booker T. Washington, and W. E. B. Du Bois advocated for education as the means to achieve advancement and equality. Black newspapers and citizens’ groups supported their communities and fought back against segregation and racism. Though their strategies differed, their goal was the same: a fuller realization of the Founding principles of equality and justice for all.

W. E. B. Du Bois summed up the Black experience after the Civil War when he stated, “The slave went free, stood a brief moment in the sun; and then moved back again toward slavery.” Du Bois points to the fact that whatever constitutional amendments were intended to protect the natural and civil rights of Blacks, and however determined Blacks were to fight to preserve those rights, they struggled to overcome the numerous legal, political, economic, and social obstacles that white supremacists erected to keep them in a subordinate position. Slavery had distorted republicanism and American ideals before the Civil War, and segregation continued to undermine republican government and equal rights after the conflict had ended.

Black leaders such as Ida B. Wells, Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, and W. E. B. Du Bois worked for Black rights in a variety of ways.

Reading Comprehension Questions

- How did the Reconstruction Amendments and federal laws protect the natural and civil rights of African Americans during the Civil War and Reconstruction?

- Despite constitutional and legal protections, how were Blacks’ constitutional rights restricted during Reconstruction?

- Reflecting on Reconstruction, W. E. B. Du Bois stated: “The slave went free, stood a brief moment in the sun; and then moved back again toward slavery.” In what ways do you think this conclusion was accurate? In what ways might have Du Bois been wrong?

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Reconstruction

By: History.com Editors

Updated: January 24, 2024 | Original: October 29, 2009

Reconstruction (1865-1877), the turbulent era following the Civil War, was the effort to reintegrate Southern states from the Confederacy and 4 million newly-freed people into the United States. Under the administration of President Andrew Johnson in 1865 and 1866, new southern state legislatures passed restrictive “ Black Codes ” to control the labor and behavior of former enslaved people and other African Americans.

Outrage in the North over these codes eroded support for the approach known as Presidential Reconstruction and led to the triumph of the more radical wing of the Republican Party. During Radical Reconstruction, which began with the passage of the Reconstruction Act of 1867, newly enfranchised Black people gained a voice in government for the first time in American history, winning election to southern state legislatures and even to the U.S. Congress. In less than a decade, however, reactionary forces—including the Ku Klux Klan —would reverse the changes wrought by Radical Reconstruction in a violent backlash that restored white supremacy in the South.

Emancipation and Reconstruction

At the outset of the Civil War , to the dismay of the more radical abolitionists in the North, President Abraham Lincoln did not make abolition of slavery a goal of the Union war effort. To do so, he feared, would drive the border slave states still loyal to the Union into the Confederacy and anger more conservative northerners. By the summer of 1862, however, enslaved people, themselves had pushed the issue, heading by the thousands to the Union lines as Lincoln’s troops marched through the South.

Their actions debunked one of the strongest myths underlying Southern devotion to the “peculiar institution”—that many enslaved people were truly content in bondage—and convinced Lincoln that emancipation had become a political and military necessity. In response to Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation , which freed more than 3 million enslaved people in the Confederate states by January 1, 1863, Black people enlisted in the Union Army in large numbers, reaching some 180,000 by war’s end.

Did you know? During Reconstruction, the Republican Party in the South represented a coalition of Black people (who made up the overwhelming majority of Republican voters in the region) along with "carpetbaggers" and "scalawags," as white Republicans from the North and South, respectively, were known.

Emancipation changed the stakes of the Civil War, ensuring that a Union victory would mean large-scale social revolution in the South. It was still very unclear, however, what form this revolution would take. Over the next several years, Lincoln considered ideas about how to welcome the devastated South back into the Union, but as the war drew to a close in early 1865, he still had no clear plan.

In a speech delivered on April 11, while referring to plans for Reconstruction in Louisiana, Lincoln proposed that some Black people–including free Black people and those who had enlisted in the military –deserved the right to vote. He was assassinated three days later, however, and it would fall to his successor to put plans for Reconstruction in place.

Andrew Johnson and Presidential Reconstruction

At the end of May 1865, President Andrew Johnson announced his plans for Reconstruction, which reflected both his staunch Unionism and his firm belief in states’ rights. In Johnson’s view, the southern states had never given up their right to govern themselves, and the federal government had no right to determine voting requirements or other questions at the state level.

Under Johnson’s Presidential Reconstruction, all land that had been confiscated by the Union Army and distributed to the formerly enslaved people by the army or the Freedmen’s Bureau (established by Congress in 1865) reverted to its prewar owners. Apart from being required to uphold the abolition of slavery (in compliance with the 13th Amendment to the Constitution ), swear loyalty to the Union and pay off war debt, southern state governments were given free rein to rebuild themselves.

As a result of Johnson’s leniency, many southern states in 1865 and 1866 successfully enacted a series of laws known as the “ black codes ,” which were designed to restrict freed Black peoples’ activity and ensure their availability as a labor force. These repressive codes enraged many in the North, including numerous members of Congress, which refused to seat congressmen and senators elected from the southern states.

In early 1866, Congress passed the Freedmen’s Bureau and Civil Rights Bills and sent them to Johnson for his signature. The first bill extended the life of the bureau, originally established as a temporary organization charged with assisting refugees and formerly enslaved people, while the second defined all persons born in the United States as national citizens who were to enjoy equality before the law. After Johnson vetoed the bills—causing a permanent rupture in his relationship with Congress that would culminate in his impeachment in 1868—the Civil Rights Act became the first major bill to become law over presidential veto.

Radical Reconstruction

After northern voters rejected Johnson’s policies in the congressional elections in late 1866, Radical Republicans in Congress took firm hold of Reconstruction in the South. The following March, again over Johnson’s veto, Congress passed the Reconstruction Act of 1867, which temporarily divided the South into five military districts and outlined how governments based on universal (male) suffrage were to be organized. The law also required southern states to ratify the 14th Amendment , which broadened the definition of citizenship, granting “equal protection” of the Constitution to formerly enslaved people, before they could rejoin the Union. In February 1869, Congress approved the 15th Amendment (adopted in 1870), which guaranteed that a citizen’s right to vote would not be denied “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

By 1870, all of the former Confederate states had been admitted to the Union, and the state constitutions during the years of Radical Reconstruction were the most progressive in the region’s history. The participation of African Americans in southern public life after 1867 would be by far the most radical development of Reconstruction, which was essentially a large-scale experiment in interracial democracy unlike that of any other society following the abolition of slavery.

Southern Black people won election to southern state governments and even to the U.S. Congress during this period. Among the other achievements of Reconstruction were the South’s first state-funded public school systems, more equitable taxation legislation, laws against racial discrimination in public transport and accommodations and ambitious economic development programs (including aid to railroads and other enterprises).

Reconstruction Comes to an End

After 1867, an increasing number of southern whites turned to violence in response to the revolutionary changes of Radical Reconstruction. The Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist organizations targeted local Republican leaders, white and Black, and other African Americans who challenged white authority. Though federal legislation passed during the administration of President Ulysses S. Grant in 1871 took aim at the Klan and others who attempted to interfere with Black suffrage and other political rights, white supremacy gradually reasserted its hold on the South after the early 1870s as support for Reconstruction waned.

Racism was still a potent force in both South and North, and Republicans became more conservative and less egalitarian as the decade continued. In 1874—after an economic depression plunged much of the South into poverty—the Democratic Party won control of the House of Representatives for the first time since the Civil War.

When Democrats waged a campaign of violence to take control of Mississippi in 1875, Grant refused to send federal troops, marking the end of federal support for Reconstruction-era state governments in the South. By 1876, only Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina were still in Republican hands. In the contested presidential election that year, Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes reached a compromise with Democrats in Congress: In exchange for certification of his election, he acknowledged Democratic control of the entire South.

The Compromise of 1876 marked the end of Reconstruction as a distinct period, but the struggle to deal with the revolution ushered in by slavery’s eradication would continue in the South and elsewhere long after that date.

A century later, the legacy of Reconstruction would be revived during the civil rights movement of the 1960s, as African Americans fought for the political, economic and social equality that had long been denied them.

HISTORY Vault: The Secret History of the Civil War

The American Civil War is one of the most studied and dissected events in our history—but what you don't know may surprise you.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Essays on the civil war and reconstruction and related topics

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

"Of the essays included in this volume all but one--that on 'The process of reconstruction'--have been published before during the last eleven years: four in the Political Science Quarterly, one in the Yale Review, and one in the 'Papers of the American Historical Association.'"--Pref.

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

3 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

For users with print-disabilities

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by Unknown on March 2, 2009

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

The Annotated

Frederick douglass, introduction and annotations by david w. blight, in 1866, the famous abolitionist laid out his vision for radically reshaping america in the pages of the atlantic ..

In his third autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass , while reflecting on the end of the Civil War, Douglass admitted that “a strange and, perhaps, perverse feeling came over me.” Great joy over the ending of slavery, he wrote, was at times “tinged with a feeling of sadness. I felt I had reached the end of the noblest and best part of my life; my school was broken up, my church disbanded, and the beloved congregation dispersed, never to come together again.” In recalling the postwar years, Douglass drew from a scene in a Shakespearean tragedy to express his memory of that moment: “ ‘Othello’s occupation was gone.’ ” In Othello, Douglass perceived a character, the former high-ranking general and “moor of Venice,” who had lost authority and professional purpose. Douglass harbored a special affinity for this most famous Black character in Western literature, whose mental collapse and horrible end lingered as a warning in a famous speech: “O, now, for ever / Farewell the tranquil mind! Farewell content!”

In 1866, Douglass took up his pen to try to capture this moment of transformation, both for himself and for the United States. For the December issue of this magazine that year, in an essay simply titled “ Reconstruction ,” Douglass observed that “questions of vast moment” lay before Congress and the nation. Nothing less than the essential results of the “tremendous war,” he writes, were at stake. Would the war become “a miserable failure … a scandalous and shocking waste of blood and treasure,” or a “victory over treason,” resulting in a newly reimagined nation “delivered from all contradictions and … based upon loyalty, liberty, and equality”? In this inquiry, Douglass’s new role as a conscience of the country became clarified. His leadership had always been through words and persuasion, written and oratorical. How, now that the war was over, would he employ his incomparable voice?

From the beginning, Reconstruction had faced three paramount questions: Who would rule in the South (defeated ex-Confederates or the victorious North?); who would rule in Washington, D.C. (Congress or the president?); and what were the meanings and dimensions of Black freedom? As of his writing in December, Douglass declared that nothing could yet be “considered final.” After ferocious debates, Congress had enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and passed the Fourteenth Amendment, the latter still subject to ratification by three-quarters of the state legislatures. Violent anti-Black riots had occurred in Memphis and New Orleans that spring and summer, killing at least 48 people in the first city and at least 38 in the second. Much had been done to secure emancipation, but all remained in abeyance, awaiting legislation, human persuasion, and acts of political will.

As Douglass was writing, two visions of Reconstruction vied for national dominance in the fall elections. President Andrew Johnson, a Democrat from Tennessee, favored a policy of a lenient restoration, a plan that allowed for no Black civil and political rights and admitted the southern states back into the Union as quickly as possible. The Republican leadership of the House and the Senate, however, demanded a slower, harsher, and more transformative Reconstruction, a process that would establish state governments in the South that were more democratic. Black civil and political rights and enforcement mechanisms in federal law formed the backbone of these “Radical Republican” regimes.

Douglass was at this juncture a Radical Republican in the spirit of Thaddeus Stevens , the congressman from Pennsylvania who led the effort to impeach Johnson. Like Stevens, Douglass argued vehemently that Johnson had to be countered and thwarted by any legal means necessary or the promise of emancipation would fail. Douglass believed at the end of 1866 that, though only at its vulnerable beginning, the United States had been reinvented by war and by new egalitarian impulses rooted in emancipation. His essay is, therefore, full of radical brimstone, cautious hope, and a thoroughly new vision of constitutional authority. In careful but clear terms, he described Reconstruction as a revolution that would “cause Northern industry, Northern capital, and Northern civilization to flow into the South, and make a man from New England as much at home in Carolina as elsewhere in the Republic.” In short, he sought an overturning of history, the expansion of human rights forged from the fact of African American freedom—and from an idealism that soon would be sorely tested. Revolutions may or may not go backwards, but they surely give no rest to those who lead them.

David W. Blight is the Sterling Professor of American History at Yale and the author, most recently, of Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom .

RECONSTRUCTION by FREDERICK DOUGLASS

The assembling of the Second Session of the Thirty-ninth Congress may very properly be made the occasion of a few earnest words on the already much-worn topic of reconstruction.

Seldom has any legislative body been the subject of a solicitude more intense, or of aspirations more sincere and ardent. There are the best of reasons for this profound interest. Questions of vast moment, left undecided by the last session of Congress, must be manfully grappled with by this. No political skirmishing will avail. The occasion demands statesmanship. 1

Whether the tremendous war so heroically fought and so victoriously ended shall pass into history a miserable failure, barren of permanent results,—a scandalous and shocking waste of blood and treasure,—a strife for empire, as Earl Russell characterized it, of no value to liberty or civilization,—an attempt to re-establish a Union by force, which must be the merest mockery of a Union,—an effort to bring under Federal authority States into which no loyal man from the North may safely enter, and to bring men into the national councils who deliberate with daggers and vote with revolvers, and who do not even conceal their deadly hate of the country that conquered them; or whether, on the other hand, we shall, as the rightful reward of victory over treason, 2 have a solid nation, entirely delivered from all contradictions and social antagonisms, based upon loyalty, liberty, and equality, must be determined one way or the other by the present session of Congress.

The last session really did nothing which can be considered final as to these questions. The Civil Rights Bill and the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill and the proposed constitutional amendments, with the amendment already adopted and recognized as the law of the land, do not reach the difficulty, and cannot, unless the whole structure of the government is changed from a government by States to something like a despotic central government, with power to control even the municipal regulations of States, and to make them conform to its own despotic will. While there remains such an idea as the right of each State to control its own local affairs,—an idea, by the way, more deeply rooted in the minds of men of all sections of the country than perhaps any one other political idea,—no general assertion of human rights can be of any practical value. To change the character of the government at this point is neither possible nor desirable. All that is necessary to be done is to make the government consistent with itself, and render the rights of the States compatible with the sacred rights of human nature. 3

The arm of the Federal government is long, but it is far too short to protect the rights of individuals in the interior of distant States. They must have the power to protect themselves, or they will go unprotected, spite of all the laws the Federal government can put upon the national statute-book.

Slavery, like all other great systems of wrong, founded in the depths of human selfishness, and existing for ages, has not neglected its own conservation. It has steadily exerted an influence upon all around it favorable to its own continuance. And to-day it is so strong that it could exist, not only without law, but even against law. Custom, manners, morals, religion, are all on its side everywhere in the South; and when you add the ignorance and servility of the ex-slave to the intelligence and accustomed authority of the master, you have the conditions, not out of which slavery will again grow, but under which it is impossible for the Federal government to wholly destroy it, unless the Federal government be armed with despotic power, to blot out State authority, and to station a Federal officer at every cross-road. This, of course, cannot be done, and ought not even if it could. The true way and the easiest way is to make our government entirely consistent with itself, and give to every loyal citizen the elective franchise,—a right and power which will be ever present, and will form a wall of fire for his protection. 4

One of the invaluable compensations of the late Rebellion is the highly instructive disclosure it made of the true source of danger to republican government. Whatever may be tolerated in monarchical and despotic governments, no republic is safe that tolerates a privileged class, or denies to any of its citizens equal rights and equal means to maintain them. What was theory before the war has been made fact by the war.

There is cause to be thankful even for rebellion. It is an impressive teacher, though a stern and terrible one. In both characters it has come to us, and it was perhaps needed in both. It is an instructor never a day before its time, for it comes only when all other means of progress and enlightenment have failed. Whether the oppressed and despairing bondman, no longer able to repress his deep yearnings for manhood, or the tyrant, in his pride and impatience, takes the initiative, and strikes the blow for a firmer hold and a longer lease of oppression, the result is the same,—society is instructed, or may be. 5

Such are the limitations of the common mind, and so thoroughly engrossing are the cares of common life, that only the few among men can discern through the glitter and dazzle of present prosperity the dark outlines of approaching disasters, even though they may have come up to our very gates, and are already within striking distance. The yawning seam and corroded bolt conceal their defects from the mariner until the storm calls all hands to the pumps. Prophets, indeed, were abundant before the war; but who cares for prophets while their predictions remain unfulfilled, and the calamities of which they tell are masked behind a blinding blaze of national prosperity? 6

It is asked, said Henry Clay, on a memorable occasion, Will slavery never come to an end? That question, said he, was asked fifty years ago, and it has been answered by fifty years of unprecedented prosperity. Spite of the eloquence of the earnest Abolitionists,—poured out against slavery during thirty years,—even they must confess, that, in all the probabilities of the case, that system of barbarism would have continued its horrors far beyond the limits of the nineteenth century but for the Rebellion, and perhaps only have disappeared at last in a fiery conflict, even more fierce and bloody than that which has now been suppressed.

It is no disparagement to truth, that it can only prevail where reason prevails. War begins where reason ends. The thing worse than rebellion is the thing that causes rebellion. What that thing is, we have been taught to our cost. It remains now to be seen whether we have the needed courage to have that cause entirely removed from the Republic. At any rate, to this grand work of national regeneration and entire purification Congress must now address itself, with full purpose that the work shall this time be thoroughly done. 7 The deadly upas, root and branch, leaf and fibre, body and sap, must be utterly destroyed. The country is evidently not in a condition to listen patiently to pleas for postponement, however plausible, nor will it permit the responsibility to be shifted to other shoulders. Authority and power are here commensurate with the duty imposed. There are no cloud-flung shadows to obscure the way. Truth shines with brighter light and intenser heat at every moment, and a country torn and rent and bleeding implores relief from its distress and agony.

If time was at first needed, Congress has now had time. All the requisite materials from which to form an intelligent judgment are now before it. Whether its members look at the origin, the progress, the termination of the war, or at the mockery of a peace now existing, they will find only one unbroken chain of argument in favor of a radical policy of reconstruction. For the omissions of the last session, some excuses may be allowed. A treacherous President stood in the way; and it can be easily seen how reluctant good men might be to admit an apostasy which involved so much of baseness and ingratitude. 8 It was natural that they should seek to save him by bending to him even when he leaned to the side of error. But all is changed now. Congress knows now that it must go on without his aid, and even against his machinations. The advantage of the present session over the last is immense. Where that investigated, this has the facts. Where that walked by faith, this may walk by sight. Where that halted, this must go forward, and where that failed, this must succeed, giving the country whole measures where that gave us half-measures, merely as a means of saving the elections in a few doubtful districts. That Congress saw what was right, but distrusted the enlightenment of the loyal masses; but what was forborne in distrust of the people must now be done with a full knowledge that the people expect and require it. The members go to Washington fresh from the inspiring presence of the people. In every considerable public meeting, and in almost every conceivable way, whether at court-house, school-house, or cross-roads, in doors and out, the subject has been discussed, and the people have emphatically pronounced in favor of a radical policy. Listening to the doctrines of expediency and compromise with pity, impatience, and disgust, they have everywhere broken into demonstrations of the wildest enthusiasm when a brave word has been spoken in favor of equal rights and impartial suffrage. Radicalism, so far from being odious, is now the popular passport to power. The men most bitterly charged with it go to Congress with the largest majorities, while the timid and doubtful are sent by lean majorities, or else left at home. The strange controversy between the President and Congress, at one time so threatening, is disposed of by the people. The high reconstructive powers which he so confidently, ostentatiously, and haughtily claimed, have been disallowed, denounced, and utterly repudiated; while those claimed by Congress have been confirmed.

Of the spirit and magnitude of the canvass nothing need be said. The appeal was to the people, and the verdict was worthy of the tribunal. Upon an occasion of his own selection, with the advice and approval of his astute Secretary, soon after the members of Congress had returned to their constituents, the President quitted the executive mansion, sandwiched himself between two recognized heroes,—men whom the whole country delighted to honor,—and, with all the advantage which such company could give him, stumped the country from the Atlantic to the Mississippi, 9 advocating everywhere his policy as against that of Congress. It was a strange sight, and perhaps the most disgraceful exhibition ever made by any President; but, as no evil is entirely unmixed, good has come of this, as from many others. Ambitious, unscrupulous, energetic, indefatigable, voluble, and plausible,—a political gladiator, ready for a “set-to” in any crowd,—he is beaten in his own chosen field, and stands to-day before the country as a convicted usurper, a political criminal, guilty of a bold and persistent attempt to possess himself of the legislative powers solemnly secured to Congress by the Constitution. No vindication could be more complete, no condemnation could be more absolute and humiliating. Unless reopened by the sword, as recklessly threatened in some circles, this question is now closed for all time.

Without attempting to settle here the metaphysical and somewhat theological question (about which so much has already been said and written), whether once in the Union means always in the Union,—agreeably to the formula, Once in grace always in grace,—it is obvious to common sense that the rebellious States stand to-day, in point of law, precisely where they stood when, exhausted, beaten, conquered, they fell powerless at the feet of Federal authority. 10 Their State governments were overthrown, and the lives and property of the leaders of the Rebellion were forfeited. In reconstructing the institutions of these shattered and overthrown States, Congress should begin with a clean slate, and make clean work of it. Let there be no hesitation. It would be a cowardly deference to a defeated and treacherous President, if any account were made of the illegitimate, one-sided, sham governments hurried into existence for a malign purpose in the absence of Congress. These pretended governments, which were never submitted to the people, and from participation in which four millions of the loyal people were excluded by Presidential order, should now be treated according to their true character, as shams and impositions, and supplanted by true and legitimate governments, in the formation of which loyal men, black and white, shall participate.

It is not, however, within the scope of this paper to point out the precise steps to be taken, and the means to be employed. The people are less concerned about these than the grand end to be attained. They demand such a reconstruction as shall put an end to the present anarchical state of things in the late rebellious States,—where frightful murders and wholesale massacres are perpetrated in the very presence of Federal soldiers. This horrible business they require shall cease. 11 They want a reconstruction such as will protect loyal men, black and white, in their persons and property; such a one as will cause Northern industry, Northern capital, and Northern civilization to flow into the South, and make a man from New England as much at home in Carolina as elsewhere in the Republic. No Chinese wall can now be tolerated. The South must be opened to the light of law and liberty, and this session of Congress is relied upon to accomplish this important work.

The plain, common-sense way of doing this work, as intimated at the beginning, is simply to establish in the South one law, one government, one administration of justice, one condition to the exercise of the elective franchise, for men of all races and colors alike. This great measure is sought as earnestly by loyal white men as by loyal blacks, and is needed alike by both. Let sound political prescience but take the place of an unreasoning prejudice, and this will be done.

Men denounce the negro for his prominence in this discussion; but it is no fault of his that in peace as in war, that in conquering Rebel armies as in reconstructing the rebellious States, the right of the negro is the true solution of our national troubles. The stern logic of events, which goes directly to the point, disdaining all concern for the color or features of men, has determined the interests of the country as identical with and inseparable from those of the negro.

The policy that emancipated and armed the negro—now seen to have been wise and proper by the dullest—was not certainly more sternly demanded than is now the policy of enfranchisement. If with the negro was success in war, and without him failure, so in peace it will be found that the nation must fall or flourish with the negro. 12

Fortunately, the Constitution of the United States knows no distinction between citizens on account of color. Neither does it know any difference between a citizen of a State and a citizen of the United States. Citizenship evidently includes all the rights of citizens, whether State or national. If the Constitution knows none, it is clearly no part of the duty of a Republican Congress now to institute one. The mistake of the last session was the attempt to do this very thing, by a renunciation of its power to secure political rights to any class of citizens, with the obvious purpose to allow the rebellious States to disfranchise, if they should see fit, their colored citizens. This unfortunate blunder must now be retrieved, and the emasculated citizenship given to the negro supplanted by that contemplated in the Constitution of the United States, which declares that the citizens of each State shall enjoy all the rights and immunities of citizens of the several States,—so that a legal voter in any State shall be a legal voter in all the States.

This article appears in the December 2023 print edition with the headline “The Annotated Frederick Douglass.”

Essay on Reconstruction

Students are often asked to write an essay on Reconstruction in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Reconstruction

Introduction.

Reconstruction refers to the period following the American Civil War. It was a time of significant changes and efforts to reintegrate the Southern states and ensure rights for former slaves.

The Process

Reconstruction began in 1865. The government introduced laws and amendments to protect the rights of African Americans, like the 14th amendment granting citizenship.

Resistance and Impact

Despite these efforts, many Southern states resisted. They passed “Black Codes” limiting African American rights. However, Reconstruction left a lasting impact on American society, shaping the fight for civil rights.

250 Words Essay on Reconstruction

Reconstruction, a pivotal period in American history, was the attempt to rebuild and reform the South politically, economically, and socially after the Civil War. It was a time of great promise, pain, and turmoil.

Political Reconstruction

Politically, Reconstruction was marked by the efforts of the federal government to reintegrate the Southern states and to define the status of freedmen. The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, collectively known as the Reconstruction Amendments, abolished slavery, granted equal protection under the law, and extended voting rights to African American men.

Social and Economic Reconstruction

Socially and economically, Reconstruction was a time of great change. The abolition of slavery marked a significant shift in the Southern labor system, leading to the rise of sharecropping. African Americans also sought to establish their own churches, schools, and social institutions.

End of Reconstruction

The end of Reconstruction in 1877, often attributed to the Compromise of 1877, saw the withdrawal of federal troops from the South. This led to the rise of the “Jim Crow” era, characterized by racial segregation and disenfranchisement of African Americans.

The Reconstruction era was a time of profound change and conflict. It brought about significant legal and social changes, but also left a legacy of unresolved issues that continue to shape American society and politics. As we study this period, we are reminded of the complexity of the process of rebuilding and reforming society after a major conflict.

500 Words Essay on Reconstruction

The period following the American Civil War, known as Reconstruction, was a time of significant political, social, and economic change. From 1865 to 1877, the United States grappled with the challenges of reintegrating the Southern states and providing civil rights to the freed slaves. This period, marked by both progress and setbacks, had profound implications for the nation’s future.

The Political Landscape of Reconstruction

Reconstruction was characterized by a struggle for power between the President and Congress. Initially, President Lincoln proposed a lenient plan to restore the Union, requiring only 10% of voters in each Southern state to swear loyalty to the Union. However, Radical Republicans in Congress sought stricter terms, culminating in the passage of the Reconstruction Acts in 1867, which divided the South into military districts and required states to draft new constitutions providing for black male suffrage.

The Social Impact of Reconstruction

Reconstruction brought significant social change, primarily through the abolition of slavery and the introduction of civil rights for African Americans. The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, known collectively as the Reconstruction Amendments, were ratified, abolishing slavery, granting citizenship to all born or naturalized in the U.S., and prohibiting the denial of voting rights based on race, respectively. However, these advancements were met with resistance, leading to the rise of white supremacist groups and the implementation of Black Codes and later Jim Crow laws, aimed at subverting African American rights.

Economic Changes During Reconstruction

The South’s economy, heavily reliant on slavery, was devastated by the Civil War. Reconstruction efforts sought to rebuild the Southern economy through the introduction of free labor. The Freedmen’s Bureau was established to assist former slaves in negotiating labor contracts, and the Southern Homestead Act was passed to provide land to poor Southerners. However, sharecropping and tenant farming systems often replicated conditions of servitude, trapping African Americans in cycles of debt and poverty.

The End of Reconstruction and Its Legacy

Reconstruction officially ended in 1877 with the Compromise of 1877, which resolved the disputed 1876 presidential election in favor of Republican Rutherford B. Hayes in exchange for the withdrawal of federal troops from the South. This marked the beginning of the ‘Jim Crow’ era, characterized by segregation and disenfranchisement of African Americans.

The legacy of Reconstruction is complex. It was a period of significant progress in civil rights, yet also a time of missed opportunities and unfulfilled promises. The struggle for racial equality continued long after Reconstruction ended, and the period’s lessons continue to resonate in contemporary discussions about race, rights, and justice.

Reconstruction was a pivotal period in American history, shaping the nation’s political, social, and economic landscape. While it marked a significant step towards racial equality, its successes were marred by persistent racism and economic inequality. Understanding Reconstruction is crucial in comprehending the enduring issues of race and equality in America.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Raymond’s Run

- Essay on Racism

- Essay on Quitting Smoking

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Reconstruction in the US After the Civil War Essay

After the Civil War that ended in 1865, the situation in the US has greatly changed, as the Southern states got an opportunity to come back (Oakes et al. 621). Realizing that the country needs rehabilitation after the war, President Lincoln and Republicans started to implement changes aimed to keep the nation together, improve infrastructure and supply people with basic needs. Trying to rebuild the South, they started the Reconstruction, which faced a range of problems.