Christianity vs. Judaism

Christianity and Judaism are two Abrahamic religions that have similar origins but have varying beliefs, practices, and teachings.

Comparison chart

About Judaism and Christianity

The definition of Christianity varies among different Christian groups. Roman Catholics, Protestants and Eastern Orthodox define a Christian as one who is the member of the Church and the one who enters through the sacrament of baptism . Infants and adults who are baptized are considered as Christians. Jesus's Jewish group became labeled 'Christian' because his followers claimed he was 'Christ' the Greek equivalent of the Hebrew and Aramaic word for ' Messiah .' Judaism is the religion of the Jewish people, based on principles and ethics embodied in the Hebrew Bible ( Tanakh ) and the Talmud .

Christianity began in 1st century AD Jerusalem as a Jewish sect and spread throughout the Roman Empire and beyond to countries such as Ethiopia, Armenia, Georgia, Assyria, Iran, India, and China. The first known usage of the term Christians can be found in the New Testament of the Bible . The term was thus first used to denote those known or perceived to be disciples of Jesus. The history of early Christian groups is told in Acts in the New Testament. The early days of Christianity witnessed the desert Fathers in Egypt, sects of hermits and Gnostic ascetics.

Jesus gave the New Law by summing up the Ten Commandments. Many of the Jews did not accept Jesus. For traditional Jews, the commandments and Jewish law are still binding. For Christians, Jesus replaced Jewish law. As Jesus began teaching the twelve Apostles some Jews began to follow Him and others did not. Those who believed the teachings of Jesus became known as Christians and those who didn't remained Jews.

Differences in Beliefs

The Religion of Mary and Joseph was the Jewish religion . Judaism's central belief is the people of all religions are children of God , and therefore equal before God. Judaism accepts the worth of all people regardless of religion, it allows people who are not Jewish and wish to voluntarily join the Jewish people. While the Jews believe in the unity of God, Christians believe in the Trinity. A Jew believes in divine revelation through the prophets and Christians believe it to be through Jesus and the prophets.

The Christian Religion encompasses all churches as well as believers without churches, as many modern practitioners may be believers in Christ but not active church goers. A Christian will study the Bible , attend church, seek ways to introduce the teachings of Jesus into his or her life, and engage in prayer. A Christian seeks forgiveness for his or her personal sins through faith in Jesus Christ . The goal of the Christian is both the manifestation of the Kingdom of God on Earth and the attainment of Heaven in the after-life.

In the following video, Christian apologist Lee Strobel interviews Rabbi Tovia Singer and fellow evangelical Christian apologist William Lane Craig about the Trinity of God:

Scriptures of Christianity and Judaism

Judaism has considered belief in the divine revelation and acceptance of the Written and Oral Torah as its fundamental core belief. The Jewish Bible is called Tanakh which is the dictating religious dogma. Christianity regards the Holy Bible, a collection of canonical books in two parts (the Old Testament and the New Testament) as authoritative: written by human authors under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, and therefore the inerrant Word of God.

Jewish vs. Christian Practices

Traditionally, Jews recite prayers three times daily, with a fourth prayer added on Shabbat and holidays. Most of the prayers in a traditional Jewish service can be said in solitary prayer, although communal prayer is preferred. Jews also have certain religious clothing which a traditional Jew wears.Christians believe that all people should strive to follow Christ's commands and example in their everyday actions. For many, this includes obedience to the Ten Commandments . Other Christian practices include acts of piety such as prayer and Bible reading. Christians assemble for communal worship on Sunday, the day of the resurrection, though other liturgical practices often occur outside this setting. Scripture readings are drawn from the Old and New Testaments, but especially the Gospels .

Comparing Jewish and Christian Religious Teachings/Principles

Judaism teaches Jews to believe in one God and direct all prayers towards Him alone while Christians are taught about the Trinity of God - The Father, the Son and Holy Spirit. Jews generally consider actions and behavior to be of primary importance; beliefs come out of actions. This conflicts with conservative Christians for whom belief is of primary importance and actions tend to be derivative from beliefs.

Another universal teaching of Christianity is following the concept of family values, helping the powerless and promoting peace which Jews also believe in.

The View of Jesus in Christianity and Judaism

To Jews, Jesus was a wonderful teacher and storyteller. He was just a human, not the son of God. Jews do not think of Jesus as a prophet . Also, Jews believe that Jesus cannot save souls, and only God can. In the Jewish view, Jesus did not rise from the dead. Judaism in general does not recognize Jesus as the Messiah.

Christians believe in Jesus as a messiah and as the giver of salvation. Christians believe that all people should strive to follow Christ's commands and example in their everyday actions.

Geographical Distribution of Jews vs. Christians

The Jews have suffered a long history of persecution in many different lands, and their population and distribution per region has fluctuated throughout the centuries. Today, most authorities place the number of Jews between 12 and 14 million. Predominantly, Jews today live in Israel, Europe and the United States .

Data suggest that there are around 2.1 billion Christians in the world all around the globe inlcuding South and North America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Oceania.

Groups/Sects

Jews include three groups: people who practice Judaism and have a Jewish ethnic background (sometimes including those who do not have strictly matrilineal descent), people without Jewish parents who have converted to Judaism; and those Jews who, while not practicing Judaism as a religion, still identify themselves as Jewish by virtue of their family's Jewish descent and their own cultural and historical identification with the Jewish people.

There are many people who follow christianity and have divided themselves into various groups/ sects depending upon varying beliefs. The types of Christians include Catholic , Protestant , Anglican , Lutheran , Presbyterian , Baptist, Episcopalian , Greek Orthodox , Russian Orthodox , Coptic .

- Jews and Christians: Exploring the past, present and Future by Various Contributors and edited by James H. Charlesworth

- Wikipedia: Jewish history

- Wikipedia: Jew#Who is a Jew

- Wikipedia: Christian

- Wikipedia: Christianity

Related Comparisons

Share this comparison via:

If you read this far, you should follow us:

"Christianity vs Judaism." Diffen.com. Diffen LLC, n.d. Web. 27 Mar 2024. < >

Comments: Christianity vs Judaism

Anonymous comments (5).

January 10, 2012, 7:53pm A rather poor and static account of Judaisim with no distinction between the period of Temple worship and the evolution of Judaism after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, which involved innovations such as synagougue worship and the codification of the Oral Law. Halakha is merely a term for law or legaly study (see the Penguin Dictionary of Judaims by Nicholas De Lange). No mention of the fact that Judaism deals with how to bevave ethically in a divinely create world whose permissible pleasures and benefits which are enjoined to enjoy. Likwise, no mention of the seven basic Noachic Commandments, the observance of which places non-Jews and Jews on a equal footing. Therefore, I do not stop Christians in the street and try to convert them to Judaism. I wish that they would accord me the same courtesy. Judaism today covers a wide range of groups, some of whom, such as the Chassidim, have beliefs that are coloured by Christian thought such as original sin and the existence of Satan. In traditonal Jewish thought, everything is created by the Almighty and there is no supernatural source of evil. Every human being has an inclination towards good and towards evil and we are all indiviudally rsponsible for our own actions. Human beings therefore are capable of change and no Redeemer who died for our sins is required. I resent the historical treatment of Jews by Christians and their belief that theirs is the one truth faith, despite Christ's statement about the many mansions in my Father's house. I aslo resent Christians' sometimes deliberate misinterpretation of passages in the Old Testament such as "eye for eye" in a literal manner, in order to portray Judaism as a brutal religion that has been supersed by Christianity, the religion of love, although throught the ages we Jews have seen percious little of this virture. Even today, the indifference of most Christians towards animal welfare and animal cruelty is striking. In Judasim, all living beings are part of the divine creation and are to be respected accordingly. I suggest that you do more reading to deepen your knowledge and understanding of our religion, without which Christianity would not have been possible. — 82.✗.✗.178

December 1, 2012, 9:41am Are you talking a out a religion that came years after the Hebrews stopped using the name of God when he told you to keep it and remember it for it is his name forever? If I recall most jews don't even utter or even try to pronounce the name anymore. Jesus the rebel had to come along and use the name,lol, Jesus said Ehyah has sent me, and said he is one with Ehyah and most jews wanted to stone him and if possible kill all his followers or mess with there teachings due to the fact Gentiles after being exposed to Messiah and his culture were being taught that they needed to be circumcised and of that other such. I didn't come to say all jews are bad, in fact there are as many good as there are bad, we are all humans. What I am saying is Judaism formed over the years compared to there predecessors. I mean lets be rash No prophet in the bible was claiming to be apart of Judaism, what they claimed was there tribe and the God. If you ask Moses what's Judaism he wouldn't know what to say because its a religion and if I go to the nearest synagogue over a year I can possibly be called a Jew too. Does that make me Judah's descendant NO. Big difference between tribes and religion — 71.✗.✗.160

December 14, 2011, 3:04am I am a little late for the discussion here. I find it interesting that with the similar beliefs in the Old testament and the Torah that the two diverge as much as they do. I have yet to find one mention of the trinity in either the Old or New Testament (if I missed it please enlighten me). To me is seems both religions claim to worship the same G-d. One teaches redemption while the other preaches salvation. To me this are a lot alike it is where man is removed from his own sin and evil. I know on a social scale there is much difference. A person is Jewish by birth and or choice. In almost any event they will be Jewish even if they choose not to believe in g-d. In Christianity you are a Christian by choice , you must ask g-d to accept you. You must apologize for a sinful nature that is part of the human condition. You must live the best you can to G-d standards and the 10 commandments. However there were a number of restrictions lifted most notably diet. I am trying to get to the root of the differences myself as I sit and look at the two religions. I know that G-d's people are to be tormented and the Jews have had that throughout history. I see this happening with the Christians now as well. I will keep digging and hope somewhere someone can help me by shedding light on the Jews and Christians. Untill then may G-d bless every one of you as he does. — 71.✗.✗.121

May 2, 2014, 3:33pm no that is a hole different religion that that the cover their hair if you thought that because of the movie gods not dead her family was islamic — 209.✗.✗.254

August 16, 2013, 5:21am Start writing down how many times your prayer have been answered and how they were answered. So next time some one tells you there's no god show 'em the list. They may say that's just a coincidence but they are probably going to start wondering if what they've been told is true and start looking into it. And for those of you who say your prayers haven't been answered, here's some advice. APPRECIATE THE little THINGS. — 72.✗.✗.10

- New Testament vs Old Testament

- Catholicism vs Christianity

- Catholic vs Protestant

- Mormonism vs Christianity

- Christianity vs Islam

- Sunni vs Shia

- Christianity vs Protestantism

- Islam vs Shia

Edit or create new comparisons in your area of expertise.

Stay connected

© All rights reserved.

Il Blog di Holyart.com

Homepage | Religion | The differences between Judaism and Christianity

The differences between Judaism and Christianity

What are the differences between Judaism and Christianity? Is the God of the Jews the same as the Christians? Let’s try to discover together what divides (and unites) two of the most widespread religions in the world.

- 1 Judaism and Christianity differences

- 2 The Jewish religion in brief and the Jewish sacred texts

- 3 What the Jews call God

We will surely have asked ourselves what are the differences between Judaism and Christianity. It may seem like a trivial question, but the truth is that there is still a lot of confusion about it, at least in the mainstream.

This confusion, in the past, has had very serious, often dramatic, consequences. There have been those who, throughout history, have not hesitated to exploit the lack of knowledge of Christians regarding the Jewish religion, to foment hatred and persecution against the Jewish people, to whom unforgivable sins have been attributed, deserving of exile. and death.

The truth is that the God of the Jews is the same one worshipped by Christians, and no difference between Catholic and Christian could ever justify all the bloodshed over the centuries, in the name of true or presumed beliefs.

Today the Catholic Christian Church admits and recognises its inescapable bond with the Jewish people and with its faith, considering the due differences, but starting from a profound religious identity and common values that are equally important for both professions of faith.

But what are the specific differences between Judaism and Christianity?

Judaism and Christianity differences

Let’s start with the definition of Christian and Jew . A Christian believes that Jesus is the son of God , crucified, died and resurrected three days later. For this, the Christian is baptised in the name of the Father, of the Son and the Holy Spirit .

A Jew, on the other hand, is a descendant of the Jewish people and, more generally, one who follows the dictates of the Jewish religion and culture.

Central to understanding the difference between Jews and Christians is the consideration of the figure of Christ .

Christians recognise Jesus as the Messiah who came among men to announce the Kingdom of Heaven and died on the cross to cleanse the whole of humanity from its sins.

For the Jews , however, Jesus was merely a prophet , and they still await the arrival of the true Messiah, who will come to Earth to save the Jewish people and usher in a new era of peace, harmony and happiness, where righteous men will be able to prosper for the eternity. Since they do not recognise the importance of the passion of Jesus’ death, the symbol of the cross has no particular religious value for the Jews.

The places destined for prayer and the celebration of religious ceremonies also distinguish Jews and Christians. Christians practise their worship in the Church , which is indeed a physical place but is above all a community of people gathered in faith in Christ. The Jews instead gather in the Synagogue , a word whose meaning is “meeting house”.

Jews and Christians also differ in their relationship with the Holy Scriptures .

The Jews make references above all to the Old Testament , and in particular, to the Torah, the 5 books that make up the first part of the Bible , namely Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, and which tell the foundation of the Jewish people and the history of the Covenant with God. They do not recognise the New Testament, as it is centred on Jesus, which they do not accept as the Messiah.

The sacred text for Christians instead is the Bible , composed of the Old Testament and above all the New Testament.

The dimension of the Christian faith is more individual than the Jewish one, as Christians profess personal redemption through Jesus Christ , who saves from sin and elevates man above his fallacious nature, in the name of a New Covenant with God, while the Jews see salvation in the perpetuation of tradition, of the dialogue between God and the Chosen People, of the ancient covenant between God and Abraham, and then God and Moses.

Again, Christians worship God as One and Triune ; the Jews claim the unity and singularity of God .

Even the sacraments are different between the two professions of faith. Catholic Christians celebrate the Eucharist and preach the importance of Confession, which is completely lacking in the Jewish religion while sharing the Sacrament of Baptism with it.

There are also further differences in what Jews believe compared to Christians. The latter venerate the saints and the Virgin Mary , so much so that they dedicate sanctuaries and celebrations to them, while the Jews venerate only God , Yahvé , whose name cannot be pronounced.

The Jewish religion in brief and the Jewish sacred texts

Abraham can be considered the first Jew , or the first man to whom God, the only creator of all things, addressed. God promised Abraham and his descendants that they would dwell forever in the land of Canaan, as long as they lived according to his dictates. As the first sign of this covenant, God ordered that every Jewish male be circumcised at birth.

Subsequently, with Moses, this covenant was enriched with the delivery by God of the Ten Commandments, and with the codification of the Torah , which contains the history of the covenant between God and the Jewish people, and which provides a guide of life and faith of every Jew. All Jews are required to respect a series of precepts ( mitzvoth ) which includes 613 obligations (248 positive actions to be performed, 365 prohibited actions) which govern life, work, relationships with the community, and dialogue with God. Among them is the study of religious texts, for oneself and one’s descendants, the sacredness of the family, but also dietary rules ( kashrut ), the obligation to do charity ( zedakà ) and many other rules of human and social mercy. Every man must honour and pursue his relationship with God through study and prayer, as done by the fathers before him.

We have already mentioned the importance reserved by the Jews to the figure of the Messiah , the chosen one who in the name of God will save the Chosen People and bring to Earth a kingdom of peace and happiness for all devoted men.

Traditions related to particular sacred objects, such as the menorah , the 7-armed oil lamp, one of the main symbols of the Jewish world, is also of great importance.

The Menorah: history and meaning of the Jewish candelabra The Menorah is one of the main symbols of the Jewish world. It is a seven-branched oil lamp. In ancient times, it was lit in the Temple…

Essential for the Jews is the concept of Zedaqah , a term that means “ justice “, and which is often associated and accompanied by “ charity ” since for the Jewish tradition an upright and just man must help the needy . So moral help is combined with material help, with often anonymous donations, which depend on the financial situation of those who donate it, and, more generally, with the offer of care, time and energy.

As for the books sacred to the Hebrews, in addition to the aforementioned Torah, we mention the Mishna , one of the fundamental texts of Judaism, collects all the commandments, the teachings delivered on Sinai by God to Moses and perfected over time by the rabbinic tradition. The Talmud instead contains the discussions and teachings of the Masters.

What the Jews call God

The Jews never utter God’s name, referring to him as Hashem , “the Name”, or, when they pray, with Adonai , “the Lord”. The term YHWH , the Tetragrammaton, defines God in the sacred texts .

What’s the Future of Religion?

A Beginner’s Guide to Christianity

Mind-Blowing Statistics About Christianity You Need to Know

Holyart Shop

Enter the Holyart world: $20 discount voucher valid on over 60,000 items

Come and discover Holyart, the largest e-commerce of religious articles in Europe and immediately receive a $20 voucher to use with your first purchase.

Check your mailbox: you will receive your discount within 5 minutes

- CERC español

- Guardians of Truth

- Ways To Give

- Religion & Philosophy

- Apologetics

Comparing Christianity and Judaism

- Written by Super User

- PETER KREEFT

Kreeft outlines the main theological and practical differences, as well as the important common elements, between Christianity and Judaism.

This is surely Jesus' point of view too, for He said He came not to destroy the Law and the Prophets but to fulfill them. From His point of view, Christianity is more Jewish than modern Judaism. Pre-Christian Judaism is like a virgin: post-Christian Judaism is like a spinster. In Christ, God consummates the marriage to His people and through them to the world.

What have Christians inherited from the Jews? Everything in the Old Testament. The knowledge of the true God. Comparing that with all the other religions of the ancient world, six crucial, distinctive teachings stand out: monotheism, creation, law, redemption, sin and faith.

Only rarely did a few gentiles like Socrates and Akenaton ever reach to the heights and simplicity of monotheism. A world of many forces seemed to most pagans to point to many gods. A world of good and evil seemed to indicate good and evil gods. Polytheism seems eminently reasonable; in fact, I wonder why it is not much more popular today.

There are only two possible explanations for the Jews' unique idea of a single, all-powerful and all-good God: Either they were the most brilliant philosophers in the world, or else they were "the Chosen People" — i.e., God told them. The latter explanation, which is their traditional claim, is just the opposite of arrogant. It is the humblest possible interpretation of the data.

With a unique idea of God came the unique idea of creation of the universe out of nothing. The so-called "creation myths" of other religions are really only formation myths, for their gods always fashion the world out of some pre-existing stuff, some primal glop the gods were stuck with and on which you can blame things: matter, fate, darkness, etc. But a Jew can't blame evil on matter, for God created it; nor on God, since He is all-good. The idea of human free will, therefore, as the only possible origin of evil, is correlative to the idea of creation.

The Hebrew word "to create" ( bara ) is used only three times in the Genesis account: for the creation of the universe (1:1), life (1:21) and man (1:27). Everything else was not "created" (out of nothing) but "formed" (out of something).

The consequences of the idea of creation are immense. A world created by God is real, not a dream either of God or of man. And that world is rational. Finally, it is good. Christianity is a realistic, rational and world-affirming religion, rather than a mythical, mystical, or world-denying religion because of its Jewish source.

The essence of Judaism, which is above all a practical religion, is the Law. The Law binds the human will to the divine will. For the God of the Jews is not just a Being or a Force, or even just a Mind, but a Will and a person. His will is that our will should conform to His: "Be holy, for I am holy" (Lev. 11:44).

The Law has levels of intimacy ranging from the multifarious external civil and ceremonial laws, through the Ten Commandments of the moral law, to the single heart of the Law. This is expressed in the central prayer of Judaism, the shma (from its first word, "hear"): "Hear O Israel: the Lord, the Lord our God is one Lord; and you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might" Deut. 6:4).

Thus, the essence of Judaism is the same as the essence of Christianity: the love of God. Only the way of fulfilling that essence — Christ — is different. Judaism knows the Truth and the Life, but not the Way. As the song says: "Two out of three ain't bad."

Even the Way is foreshadowed in Judaism, of course. The act brought dramatically before the Jews every time they worshiped in the temple was an act of sacrifice, the blood of bulls and goats and lambs foretelling forgiveness. To Christians, every detail of Old Testament Judaism was a line or a dot in the portrait of Christ. That is why it was so tragic and ironic that "He came to what was His own, but his own people did not accept Him" (John 1:11). Scripture is His picture, but most Jews preferred the picture to the person.

Thus the irony of His Saying:

You search the Scriptures, because you think you have eternal life through them; even they testify on my behalf" (John 5:39-40).

No religion outside Judaism and Christianity ever knew of such an intimate relationship with God as "faith." Faith means not just belief but fidelity to the covenant, like a marriage covenant. Sin is the opposite of faith, for sin means not just vice but divorce, breaking the covenant.

In Judaism, as in Christianity, sin is not just moral and faith is not just intellectual; both are spiritual, i.e., from the heart. Rabbi Martin Buber's little classic "I and Thou" lays bare the essence of Judaism and of its essential oneness with Christianity.

Christians are often asked by Jews to agree not to "proselytize." They cannot comply, of course, since their Lord has commanded them otherwise (Matt. 28:18-20). But the request is understandable, for Judaism does not proselytize. Originally this was because Jews believed that only when the Messiah came was the Jewish revelation to spread to the gentiles. Orthodox Jews still believe this, but modern Judaism does not proselytize for other reasons, often relativistic ones.

Christianity and Judaism are both closer and farther apart than any two other religions. On the one hand, Christians are completed Jews; but on the other, while dialogue between any two other religions may always fall back on the idea that they do not really contradict each other because they are talking about different things, Jews and Christians both know who Jesus is, and fundamentally differ about who He is. He is the stumbling stone (Is. 8:14).

Additional Info

- Author: Peter Kreeft

Kreeft, Peter. "Comparing Christianity & Judaism." National Catholic Register . (May, 1987).

Reprinted by permission of the author. To subscribe to the National Catholic Register call 1-800-421-3230.

- Publisher: National Catholic Register

- Alternate: http://catholiceducation.org/articles/apologetics/ap0007.html

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation . CERC is entirely reader supported.

Meaghen Gonzalez Editor

Acknowledgement

Interested in keeping Up to date?

Sign up for our weekly e-letter, find this article helpful.

Our apostolate relies on your donations. Your gifts are tax deductible in the United States and Canada.

Donate $5.00 (USD)

Donate Monthly $5.00 (USD)

Donate Monthly $13.00 (USD)

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

Christianity and Judaism

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 20257

Isabella D’Aquila

16 April 2019

It has long been asserted that Christianity arose from Judaism, which began with the covenant that God made with Abraham, promising him the gift of many offspring and the land of Israel. Moses was presented the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai, and the law of the Torah was born. When Jesus Christ died and rose from the dead, there were some that believed he was the messiah and some who did not, which created the modern-day distinction we see between Judaism and Christianity. However, there are some who dispute this connection. Marcion was one of those who rejected this connection, and he did not accept the Hebrew Bible and certain books of the New Testament for its distinct ties to the Jewish faith. While Marcion rejected the letter to the Hebrews for it being “too Jewish,” it can be seen that when compared to Luke-Acts and Galatians, texts revered by Marcion, the arguments made are the same, using the proof of Abraham’s faith, sin, and sacrifice, and the rejection of Moses is why the Jews should have faith in Jesus.

Both Hebrews and Galatians both use the evidence of Abraham having faith in God to show that having faith in Jesus will reap many benefits, and this use of the patriarch of Judaism is what allows Marcion to label Hebrews as “too Jewish.” Both of these letters were written to established communities that had some Jews for Jesus, but the basis of the letter shows that their faith in him, since he had not yet returned, was waning. The Galatians were continuing to circumcise, as this was part of the Jewish covenant with God, but Paul wanted them to understand that they could not have faith and law working together. They either needed to have faith in God and God’s son, or continue to follow the laws of the covenant, which would distinguish them as either Jews for Jesus or Jews not for Jesus. These letters, and the evidence of faith, are being used to show the Hebrews and the Galatians that they should continue to have faith in Jesus, because people before have had continued faith in God and were rewarded for it. In Galatians 3, Paul writes, “Just as Abraham ‘believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness,’ so, you see. . . the scripture, foreseeing that God would justify the Gentiles by faith, declared the gospel beforehand to Abraham, saying, ‘All the Gentiles shall be blessed in you.’ For this reason, those who believe are blessed with Abraham who believed” (Galatians 3:6-9). The argument that Paul is making here is that God justified Abraham on the basis of faith, so they do not need to circumcise themselves any longer. This argument is repeated in Hebrews, where it is written, “By faith Abraham obeyed when he was called to set out for a place that he was to receive as an inheritance; and he set out, not knowing where he was going . . . By faith he received the power of procreation, even though he was too old -- and Sarah herself was barren -- because he considered himself faithful who had promised” (Hebrews 11: 8, 11). Galatians and Hebrews both contain the argument that the patriarch of Judaism did not have law to lean on, so he trusted in God and had faith, and he received many rewards. While faith in Jesus might have been waning at the time, Paul and the author of the letter to the Hebrews both want the Jews for Jesus to remember the message, as having faith in Jesus will benefit them greatly in the future, showing that both books contain the same message.

Both the letter to the Hebrews and the Gospel of Luke assert the fact that Jesus is the only one who can heal sins, as the animal sacrifices seen in Judaism made by the priests on a daily basis do not hold the power to save someone from his or her sins, as they need to be performed repeatedly. While Judaism does not have the same teachings of sin as Christianity, in biblical times sacrifices were a common way to ask God for forgiveness for any sinful behaviors. The sacrifice of Jesus’ life on the cross is considered the ultimate sacrifice. In Hebrews 10, the author writes, “But in these sacrifices there is a reminder of sin year after year. For it is impossible for the blood of bulls and goats to take away sins” (Hebrews 10: 3-4). The author is referring to the animal sacrifices made in synagogues, specifically the Temple, regularly, arguing that if they need to be repeated then they are not truly taking away sin. When Jesus died on the cross, he made the final and ultimate sacrifice that saved humankind from their sins, which is something that sacrificial animals cannot do. This argument is repeated in the gospel of Luke, by Jesus himself. When Jesus encounters a paralytic and heals them, he says, “‘Which is easier to say, ‘Your sins are forgiven you,’ or to say, ‘Stand up and walk’? But so that you may know that the Son of Man has authority on earth to forgive sins” (Luke 5: 23-24). Coming from the lips of Jesus himself, he tells the formerly paralytic man that he has the power to forgive sins, which is something only he can do. Both Hebrews and the Gospel of Luke repeat the idea that Jesus is the only being, human or animal, who has the power to save humankind from their sins, showing that a text labeled “too Jewish” by Marcion has the same lesson as another text.

Hebrews and the gospel of Luke assert that the new covenant made through the life and death of Jesus Christ is superior to the covenant made between God and Abraham, which establishes a superiority of Christianity over Judaism. This is first seen in Hebrews 8, where the author writes, “But Jesus has now obtained a more excellent ministry, and to that degree he is the mediator of a better covenant, which has been enacted through better promises. For if that first covenant had been faultless, there would have been no need to look for a second one” (Hebrews 8: 6-7). This establishes that the author believes the new covenant created through Jesus is superior to the covenant created between Abraham and God. Where the similarity between Hebrews and Luke is created is in what the sign of the new covenant is. In Hebrews 9, it is written, “But when Christ came as a high priest of the good things that have come. . . not with the blood of goats and calves, but with his own blood, thus obtaining eternal redemption” (Hebrews 9: 11-12). The sacrifice of Jesus’ life and his blood is the sign of the new covenant, which is superior to the sacrificial blood of goats and calves. In the Gospel of Luke, Luke writes, “And he did the same with the cup after supper, saying, ‘This cup that is poured out for you is the new covenant in my blood’” (Luke 22:20). These words are coming from Jesus’ lips, telling his disciples at the final supper that his blood, the sacrifice of his life, is the sign of the new covenant created with God and will allow all those who believe in him to receive eternal redemption. The idea that there has been a new, superior covenant created between God and his people and the sign of that covenant is the blood of Jesus Christ is paralleled in the gospel of Luke and in Hebrews.

The letter to the Hebrews and Stephen’s sermon in Acts use the initial rejection of Moses as proof to show that Jesus should not be rejected. At this time there was still a distinct separation between Jews for Jesus and Jews not for Jesus, so using the proof of a common figure known by both parties was a way to urge those who did not yet have faith in Jesus to have faith. In Acts, Stephen says, “It was this Moses whom they rejected when they said, ‘Who made you a ruler and a judge?’. . . He led them out, having performed wonders and signs in Egypt, at the Red Sea, and in the wilderness for forty years. . . Our ancestors were unwilling to obey him . . . But God turned away from them and handed them over to worship the host of heaven” (Acts 7: 35-36, 39, 42). Moses performed many miracles in helping the Jews escape Egypt, just as Jesus performed numerous miracles. However, Moses was rejected just as some are continuing to reject Jesus. Stephen parallels Jesus to Moses to show those who have not yet accepted him that they should, because God turned away from those who did not accept Moses. This is seen again in Hebrews 12, where the author says, “See that you do not refuse the one who is speaking, for if they did not escape when they refused the one who warned them on earth, how much less will we escape if we reject the one who warns from heaven!” (Hebrews 12:25). The author of Hebrews is telling the people those who did not accept Moses were unable to escape divine punishment, and those who did not accept Jesus will likely experience the same fate. The same argument is used in both Hebrews and Acts, that those who do not accept Jesus will be punished by God, just as those who did not accept Moses.

Now, while Marcion believed that the letter written to the Hebrews is “too Jewish,” it can be seen that the author of Hebrews uses many of the same arguments as the authors of Galatians and Luke-Acts. There is use of Old Testament figures, such as Abraham and Moses, to show Jews for Jesus that having faith in the Son of God will prove to be beneficial. Marcion’s rejection of texts that used Judaism or Jewish figures to support the idea that Jesus was the messiah does not get rid of the history of Christianity and Judaism. Marcion might not like the use of the Jewish patriarchs in the New Testament, but it cannot be said that Hebrews is “too Jewish” because the same arguments are made in the Gospel of Luke and Galatians, which are texts that Marcion revered.

- Help & FAQ

Christianity's Jewish Origins Rediscovered: The Roles of Comparison in Early Modern Ecclesiastical Scholarship

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review

The history of early Christianity began in comparison: comparison of Christian practices with what was known about the practices of ancient Roman priests, and with what was known-or thought to be known-about the practices of Jews in the Second Temple. These comparisons helped to inspire the larger enterprise of comparative study of religion in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. But they also helped to inspire ecclesiastical historians to look directly and seriously at the Jewish world in which Jesus lived and worked. As knowledge of rabbinical Judaism grew, comparison also led to a growing awareness that Christianity grew from Jewish roots, and that it had incorporated into its core practices many elements of Jewish worship.

All Science Journal Classification (ASJC) codes

- History and Philosophy of Science

- antiquarianism

- Christian Hebraism

- comparative study of religion

- Last Supper

Access to Document

- 10.1163/24055069-00101002

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

- Link to the citations in Scopus

Fingerprint

- Jewish Christianity Arts & Humanities 100%

- Judaism Arts & Humanities 25%

- Jewish Root Arts & Humanities 23%

- Jewish World Arts & Humanities 21%

- Second Temple Arts & Humanities 20%

- Christian Practice Arts & Humanities 19%

- Early Christianity Arts & Humanities 17%

- Worship Arts & Humanities 13%

T1 - Christianity's Jewish Origins Rediscovered

T2 - The Roles of Comparison in Early Modern Ecclesiastical Scholarship

AU - Grafton, Anthony

N1 - Publisher Copyright: © 2016 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands.

N2 - The history of early Christianity began in comparison: comparison of Christian practices with what was known about the practices of ancient Roman priests, and with what was known-or thought to be known-about the practices of Jews in the Second Temple. These comparisons helped to inspire the larger enterprise of comparative study of religion in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. But they also helped to inspire ecclesiastical historians to look directly and seriously at the Jewish world in which Jesus lived and worked. As knowledge of rabbinical Judaism grew, comparison also led to a growing awareness that Christianity grew from Jewish roots, and that it had incorporated into its core practices many elements of Jewish worship.

AB - The history of early Christianity began in comparison: comparison of Christian practices with what was known about the practices of ancient Roman priests, and with what was known-or thought to be known-about the practices of Jews in the Second Temple. These comparisons helped to inspire the larger enterprise of comparative study of religion in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. But they also helped to inspire ecclesiastical historians to look directly and seriously at the Jewish world in which Jesus lived and worked. As knowledge of rabbinical Judaism grew, comparison also led to a growing awareness that Christianity grew from Jewish roots, and that it had incorporated into its core practices many elements of Jewish worship.

KW - antiquarianism

KW - Christian Hebraism

KW - comparative study of religion

KW - Last Supper

KW - Mishnah

KW - Passover

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=85049709388&partnerID=8YFLogxK

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/citedby.url?scp=85049709388&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1163/24055069-00101002

DO - 10.1163/24055069-00101002

M3 - Article

AN - SCOPUS:85049709388

SN - 2405-5050

JO - Erudition and the Republic of Letters

JF - Erudition and the Republic of Letters

Trending Topics:

- Say Kaddish Daily

- Passover 2024

Jewish-Christian Relations Today

Though Jews and Christians have had a complicated and tense relationship, relations today are better than ever.

By Michael Kress

While differences between the two faith communities still exist, for the first time in history Jews today have a reasonable expectation that these differences will be addressed through interfaith dialogue rather than the violence of the past.

The state of Jewish-Christian relations varies from group to group, but some general trends do emerge from examining the ways that Jews and Christians interact today:

– The Holocaust profoundly affected the ways that Christians from across the theological spectrum think about and interact with Jews. After World War II, Christians were forced to confront their religion’s role in helping make possible the demonization of Jews to such a great degree that slaughtering Jews en-masse could take place. Anti-Jewish theology, which had for two millennia pervaded Christian thought, has been largely eliminated, such as the belief that Jews are responsible for the death of Jesus (known as deicide). In addition, the role of Christian rescuers–people whose faith led them to risk their lives by hiding or otherwise saving Jews–provides a meaningful link between Jews and Christians. However, the role of Christians and Christianity in perpetuating the Holocaust remains a point of contention between the two religions.

– Israel — specifically, different Christian groups’ stances toward the Jewish state and its policies — is a major factor in interfaith relations. This is straining old friendships between Jews and liberal Christians while drawing Jews closer to conservative Christians with whom they have historically been at odds.

– As Jews and Christians intermarry with increasing frequency, especially in the United States, families are becoming more familiar with the religions to which their relatives adhere. Although intermarriage produces tensions and conflicts, anecdotal evidence suggests it also produces learning opportunities: When Christians join Jewish families, they get to know Jewish people and Judaism in a more personal way that often helps shatter stereotypes or anti-Jewish feelings they may have had. Jews, of course, have the same experience vis-à-vis their new Christian families.

– Christians in recent years have become increasingly interested in exploring the life of Jesus, which has led many Christians to a more profound and heartfelt respect for the religion of Jesus, Judaism. Learning about Jesus, for many Christians, inherently involves learning about Judaism, for Jesus was a practicing Jew. Christian theologians today tend to emphasize the close relationship between Judaism and Christianity. The centuries-old belief in supercessionism–that Christianity superceded, or replaced, Judaism–has been rejected by theologians from across the Christian spectrum .

Jews, for their part, have not ignored the changes in Christianity. In 2000, a transdenominational group of Jewish rabbinic and academic leaders issued a statement called Dabru Emet , “Speak the Truth.” In it, they acknowledged the efforts of Christians to improve interfaith relations and called on Jews to learn about and likewise affirm the positive changes. The statement listed eight points on which Jews and Christians could base dialogue, including “Jews and Christians worship the same God,” and “a new relationship between Jews and Christians will not weaken Jewish practice.” Tellingly, though, it was a statement about the Holocaust that generated the most controversy from the Jewish community: “Nazism was not a Christian phenomenon.”

Catholic-Jewish Relations

Among the many changes instituted in Catholicism as part of the monumental Second Vatican Council in the 1960s was the declaration Nostra Aetate (“In Our Time”), which formally rejects the charge of deicide, “decries hatred, persecution, displays of anti-Semitism directed against Jews at any time and by any one,” and calls for “mutual respect and knowledge” between Catholics and Jews.

It was, however, John Paul II’s papacy that redefined the relationship between Catholics and Jews. John Paul II (who was elected pontiff in 1978) became the first pope since ancient times to visit a synagogue; established diplomatic relations between the Vatican and Israel; visited Israel in 2000; and issued a sweeping apology for past Church “sins.” He has spoken often of the kinship he sees between the two religions, saying that without Judaism, Christianity could not have come into being.

Many lingering Catholic-Jewish tensions revolve around the Holocaust. In his apology, many Jews were upset that the pope failed to mention the Holocaust specifically. The pope also has taken steps to make the wartime Pope Pius XII into a saint; many Jewish leaders and scholars believe Pius XII could have–but chose not to–do much more to save Jews and stop the genocide.

Sainthood has also been a point of tension in other cases. In one instance the pope named as saint Edith Stein, a Jewish convert who died in the Holocaust, angering Jews who felt that Stein died because she was a Jew, not a Catholic Tension also centers around the limited access Jewish leaders and scholars have had to Vatican archives which may contain records shedding light on the Church’s role in the Holocaust. Jewish leaders and scholars are seeking permission to delve into the vast Vatican archives to shed light on the Church’s role in the Holocaust and more generally in Jewish-Catholic relations throughout the centuries. The Vatican has resisted such broad access to its historical records, but negotiations are continuing.

Mainline Protestants and Jews

For much of the 20th century, Jewish-Christian relations in the United States were defined mostly as the growing affinity between Reform Jews and liberal “mainline” Protestants, which includes, among others, Presbyterians and Episcopalians. Mainline Protestants and liberal Jews alike adhered to liberal religious, social, and political values and embraced modernist belief in human progress. Closer relations with Jews were part of mainline Protestants’ growing acceptance of what would later be known as “multiculturalism” and their redefinition of America as a more than just a Christian nation. The relationship between mainline Protestants and liberal Jews remains strong today, especially when it comes to domestic political lobbying and social action issues.

But in recent years, the ties have been strained over the issue of Israel. Liberal Protestants tend to condemn Israel’s policies toward the Palestinians; though they also condemn terrorism, many Jews feel that Protestant critics of Israel do not understand or sympathize with the big-picture political issues or the suffering of Israeli civilians. Protestant opposition to Israeli policies has been especially sharp in Europe, where there is greater support for movements seen as anti-colonial, including the Palestinian cause.

Evangelical Protestants

Over the last two decades of the 20th century, conservative Protestants became the culturally and politically dominant force in American Protestantism. It is with these evangelicals that today’s Jews have the most complicated and surprising relationship.

There are sharp points of disagreement between Jews and conservative Christians. Though evangelical theologians have rejected deicide and supercessionism charges, long-held beliefs die hard, and the writings of theologians don’t always trickle down to the pews, leading to occasional conflicts. In one period of 2001, the issue was repeatedly in the news when various public personalities were denounced by Jewish leaders for anti-Jewish statements; among those in the midst of the furor were a basketball player and a comic-strip creator, neither of them, of course, theologians or spokespeople for Christianity.

Evangelicals’ belief that Christ provides the only way to salvation leads to what is perhaps the sharpest and most emotional wedge between them and Jews: proselytism.

In the 1990s, tensions flared between Jews and Southern Baptists–the largest Protestant denomination in the United States–when the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) announced plans for renewed evangelism of Jews. The SBC later issued a booklet with advice on proselytizing to Jews during the High Holiday period. Organizations such as the Anti-Defamation League denounced the booklet and the idea that any religion can have a monopoly on truth and salvation

More troublesome to many Jews is the growth of so-called Messianic Jewish communities. Messianic Jews observe Jewish customs and rituals but believe in “Yeshua” (Jesus) as the Messiah, a belief anathema to mainstream Judaism. Most Jews do not consider Messianic Jews to be Jewish, while the evangelical world embraces them, often referring to them as Jewish Christians. The establishment of Messianic synagogues/churches in heavily Jewish cities and neighborhoods, such as Brooklyn, N.Y., and those groups’ proselytism directly to Jews has inflamed tensions.

However, despite strains like these, evangelicals and Jews have forged an alliance over the issue of Israel. Because of their theological beliefs and conservative political leanings, evangelicals are strongly and vocally supportive of Israel, and are in many cases more hawkish than American Jewish Zionists. In evangelical eschatological theology, Jews are to establish a Jewish state in Israel as a precursor to the end-times; those Jews will then convert to Christianity, though that eventuality is less remarked upon publicly by Jews or Christians.

Given evangelicals’ power within the Republican party and flagging support for Israel among political and religious liberals, conservative Christians’ support for the Jewish state has proven valuable to the American-Israeli alliance. In addition, as Orthodox Jewish institutions increasingly emphasize political lobbying and other public roles, they often find themselves in synch with evangelical Christians on other political and social issues as well.

None of the issues that have separated Jews and Christians have disappeared entirely; change is evolutionary, especially when dealing with age-old religious beliefs. But the changes in the Jewish-Christian relationship since the postwar years bode well for a future in which these religious “cousins” can live together peacefully, with a level of mutual respect unknown until now.

Join Our Newsletter

Empower your Jewish discovery, daily

Discover More

Jewish Languages

Am Yisrael Chai: The Meaning and History of this Jewish Rallying Cry

This slogan of Jewish resilience was popularized by the legendary songwriter Shlomo Carlebach.

Jewish Culture

Eight Jewish Nobel Laureates You Should Know

These eight lesser-known Jewish Nobel laureates made groundbreaking contributions to science, culture and more.

These Nine Tombs Have Attracted Jewish Pilgrims for Centuries

Take a look inside the places that Abraham, King David, Queen Esther and other biblical characters are said to have been buried.

Parallel Histories of Early Christianity and Judaism

How contemporaneous religions influenced one another.

By Jacob Neusner

Everyone knows that Judaism gave birth to Christianity. But the formative centuries of Christianity also tell us much about the development of Judaism. As formative Christianity demands to be studied in the setting of formative Judaism, so formative Judaism must be studied in the context of formative Christianity.

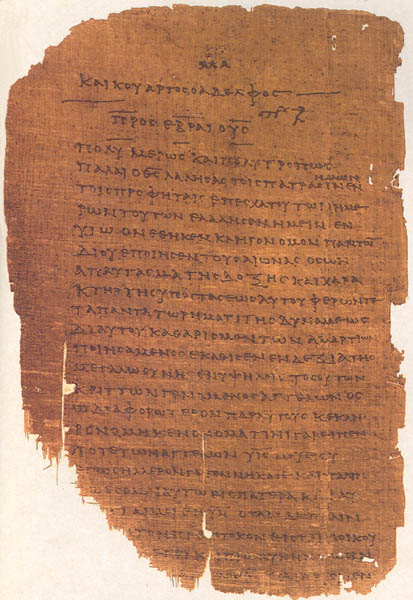

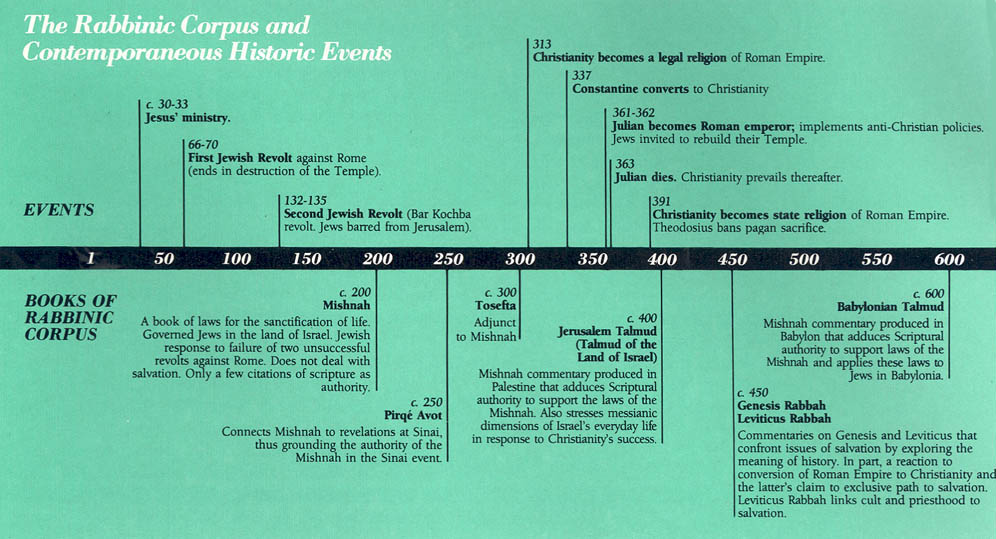

Both Judaism and Christianity rightly claim to be the heirs and products of the Hebrew Scriptures—Tanakh a to the Jews, Old Testament to the Christians. Yet both great religious tradition derive not solely or directly from the authority and teachings of those Scriptures. They reach us, rather, from the ways in which that scriptural authority has been mediated, and those biblical teachings interpreted, through other holy books. The New Testament is the prism through which the light of the Old comes to Christianity. For Judaism, the rabbinic corpus serves the same function. The corpus of the New Testament is well known.

The distinctive corpus of rabbinical Judaism, the so-called oral Torah, is less well known, but it is the star that guides Jews to the revelation of Sinai, the Torah.

The rabbinic corpus—what we might think of as the historical parallel to the New Testament— consists of the Mishnah, a law code compiled in about 200 -->A.D. --> supplemented by the partly contemporaneous Tosefta; b the Talmud of the Land of Israel, c a systematic exegesis of the Mishnah, compiled about 400 -->A.D. -->; Midrashim (singular, Midrash), various collections of exe geses of Scriptures, compiled between 400 and 600 -->A.D. -->; biblical commentaries of the fourth and fifth centuries, such as Genesis Rabbah, Leviticus Rabbah and the Talmud of Babylonia, also a systematic explanation of the Mishnah, compiled about 500–600 -->A.D. --> All together, these writings 044 constitute “the oral Torah,” that is, the body of tradition which, although originally oral, is nevertheless in principle assigned to the authority of God’s revelation to Moses at Mt. Sinai. d

The claim of these two great Western religious traditions, in all their rich variety, is the veracity not merely of Scripture, but also of Scripture as interpreted by the New Testament or by the oral Torah.

Thus, the Hebrew Scriptures produced two interrelated, yet quite separate, groups of religious societies that developed along lines established during late antiquity, culminating in the fourth century -->A.D. -->

As Christians looked to the figure of Christ, as reflected in the pages. of the New Testament, Jews looked to Torah as understood to include the rabbinic corpus. Torah means revelation: first, the five books of Moses; later, the whole Hebrew Scripture. But still later it referred to both the Written and Oral Revelation of Sinai, embodied in the Mishnah, the Talmuds and other rabbinical writings. Finally, Torah came to stand for, to symbolize, what in modern language is called “Judaism”: the whole body of belief, doctrine, practice, patterns of piety and behavior, and moral and intellectual commitments that constitute the Judaic version of reality.

While the Christ-event stands at the beginning the tradition of Christianity, the rabbinic corpus on the other hand, comes at the end of the formation of the Judaism that is contained within it. The rabbinic corpus is the written record of the constitution of the life of Israel, the Jewish people. The actual writing down of the rabbinic corpus occurred long after the principles and guidelines of that constitution had been worked out and effected in everyday life.

The early years of Christianity were dominated first by the figure of the Master, then his disciples and their followers, bringing the gospel to the nations. The formative years of rabbinic Judaism saw a small group of men who were not dominated by a single leader but who effected an equally far-reaching revolution in the life of the Jewish people.

Both the apostles and the rabbis thus reshaped the antecedent religion of Israel, and each in its own way claimed to be Israel. Initially, Christians sought their adherents from Jews. The Christian Jews proclaimed that the Messiah had come in Jesus. The rabbinic Jews proclaimed that only through the full realization of the imperatives of the Hebrew Scriptures, as interpreted and applied by the rabbis, would the people merit the coming of the Messiah. The rabbis, moreover, claimed that Moses had revealed not only the message now written down in his books, but also an oral Torah, that was formulated and transmitted to his successors, and they to theirs, through Joshua, the prophets, the sages, scribes and other holy men and, finally, to the rabbis of their day. For the Christian, therefore, the issue of the Messiah predominated; for the rabbinic Jew, the issue of Torah; and for both, as we shall see, the question of salvation became crucial.

Behind the immense varieties of Christian life stand the evocative teachings and theological and moral convictions assigned by Christian belief to the figure of Christ. To be a Christian in some measure meant, and means, to seek to be like him, in one of the many ways in which Christians envisaged him.

To be a Jew may similarly be reduced to the single, pervasive symbol of Judaism: Torah. To be a Jew meant to live the life of Torah, in one of the many ways in which the masters of Torah taught.

We now what the figure of Christ has meant to the art, music and literature of the West; the Church to its politics, history and piety; Christian faith to its values and ideals. It is harder to say what Torah would have meant to creative arts, the 045 course of relations among nations and people, hopes and aspirations of ordinary folk, if it had come to predominate. For between Christ, universally known and triumphant, and Torah, the spiritual treasure of a tiny, harassed, abused people, seldom fully known and never long victorious, stands the abyss: mastery of the world on the one side, and that same world’s sacrifice on the other.

Perhaps the difference comes at the very start when the Christians, despite horrendous suffering, determined to conquer and save the world and to create the new Israel. The rabbis of Israel, unmolested and unimpeded, set forth to trans form and regenerate the old Israel. For the former, the arena of salvation was all humankind, actor was a single man. For the latter, the course of salvation began with Israel, God’s first love, the stage was that singular but paradigmatic society, the Jewish people.

To save the world the apostle had to suffer and for it, appear before magistrates, subvert empires. To redeem the Jewish people the rabbi had to enter into, share and reshape the life the community, deliberately eschew the politics nations and patiently submit to empires.

The vision of the apostle extended to all nations and peoples; immediate suffering therefore was the welcome penalty to be paid eventual universal dominion. The rabbi’s eye looked upon Israel, and, in his love for Jews, sought not to achieve domination or to risk martyrdom, but rather to labor for social spiritual transformation that was to be accomplished through the complete union of his life with that of the community. The one was prophet to the nations; the other, priest to the people. No wonder then that the apostle earned the crown of martyrdom, but prevailed in history; while rabbi received martyrdom, when it came, only as one of, and wholly within, his people. The rabbi gave up the world and its conversion in favor of his people and its regeneration. In the end people hoped that through its regeneration, need be through its suffering, the world would be redeemed. But the people would be instrument, not the craftsmen, of redemption, which God alone would bring.

That is how things look when we turn backward, from the present. But what do we see when we place ourselves squarely into the formative centuries of Christianity and of Judaism, the first four centuries of the Common Era? Let us look first at the religious world-view before 70 -->A.D. -->, when the Romans destroyed Jerusalem and burned the Jewish Temple. This is the world in which Jesus lived, the last common world shared by both traditions, Judaism and Christianity.

At the center of the Jewish world of the first century -->A.D. --> was Jerusalem and the Temple. From near and far pilgrims climbed the paths to Jerusalem. Distant lands sent their annual tribute, taxes imposed by a spiritual rather than a worldly sovereignty. Everywhere Jews turned to the Temple Mount when they prayed. Although Jews differed about matters of law and theology, the meaning history and the timing of the Messiah’s arrival, 046 most affirmed the holiness of the city Isaiah called Ariel, Jerusalem, the faithful city. It was here that the sacred drama of the day must be enacted. And looking backward, we know they were right. It was indeed the fate of Jerusalem which in the end shaped the faith of Judaism and Christianity for endless generations to come—but not quite in the ways that most people expected before 70 -->A.D. -->

For centuries Israel had sung with the psalmist, “Pray for the peace of Jerusalem! May all prosper who seek your welfare!” ( Psalm 122:6 ). Jews long contemplated the lessons of the old destruction of Jerusalem—by the Babylonians in 586 -->B.C. --> They were sure that by learning the lessons taught by the great prophets Jeremiah, Ezekiel and (Second) Isaiah, they had ensured the city’s eternity.

Even then the Jews were a very old people. Their records, translated into the language of all civilized people (Greek), testified to their antiquity. They could look back upon ancient disasters, the spiritual lessons of which illumined current times.

In the Temple precincts, priests hurried to and fro, important because of their tribe, sacred because of their task, officiating at the sacrifices morning and eventide, busying themselves through the day with the Temple’s needs. In the Temple’s outer courts Jews from all parts of the world, speaking many languages, changed their foreign money for the Temple coin. They brought up their shekel , together with the free will, or peace, or sin, or other offerings they were liable to give. Outside, in the city beyond, artisans 047 created the necessary vessels or repaired broken ones. Incense makers mixed spices. Animal dealers selected the most perfect beasts sacrifice. In the schools young priests were taught the ancient law, to which in time they would conform as had their ancestors before them, exactly as did their fathers that very day. All the population either directly or indirectly was engaged in some way in the work of the Temple. The city lived for it, by it and on its revenues. In modern terms, Jerusalem was a center of pilgrimage, and its economy was based upon tourism.

But no one saw things in such a light. Jerusalem had an industry, to be sure, but if a Jew were asked, “What is the business of this city?” he would have replied without guile, “It is a holy city, and its work is the service of God on high.” The Temple was the center of the world. To it, in time, would come the anointed of God. In the meantime, the Temple sacrifice was the way to serve God, a way he himself in remotest times had decreed. True, there were other ways believed to be more important, for the prophets had emphasized that sacrifice alone was not enough to reconcile the sinner to a God made angry by unethical or immoral behavior. Morality, ethics, humility, good faith—these, too, he required. But good faith meant loyalty to the covenant which had specified, among other things, that the priests do just what they were doing. The animal sacrifices, the incense, the oil, wine and bread were to be arrayed in the service of the Most High.

Later, people condemned this generation of the first Christian century. Christians and Jews alike reflected upon the Roman destruction of the great sanctuary in 70 -->A.D. --> They looked to the alleged misdeeds of those who lived at the time for reasons to account for the destruction. No generation in the history of Jewry had been so roundly, universally condemned by posterity.

Christians remembered, in the tradition of the Church, that Jesus wept over the city and said a bitter, sorrowing sentence:

“O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, killing the prophets and stoning those who are sent to you! How often would I have gathered your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you would not! Behold, your house is forsaken and desolate. For I tell you, you will not see me again, until you say, ‘Blessed is the who comes in the name of the Lord’ ” ( Matthew 23:37–39 ). “And when the disciples pointed out the Temple buildings from a distance, he said to them, ‘You see all these, do you not? Truly, I say to you, there will not be left here one stone upon another, that will not be thrown down’ ” ( Matthew 24:2 ; cf. Luke 21:6 ).

So for 20 centuries, Jerusalem was seen through the eye of Christian faith as a faithless city, killing prophets, and therefore desolated by the righteous act of a wrathful God.

But Jews said no less. From the time of Roman destruction, they prayed:

“On account of our sins we have been exiled from our land, and we have been removed far from our country. We cannot go up to appear and bow down before you, to carry out our duties in your chosen Sanctuary, in the great and holy house upon which your name was called” ( Siddur, Musaf for the Sabbath that coincides with the new moon).

It is not a great step from “our sins” to “the sins of the generation in whose time the Temple was destroyed.” It is not a difficult conclusion, and more than a few have reached it. The Temple was destroyed mainly because of the sins of the Jews of that time, particularly, according to the tradition, the sin of “causeless hatred.” Whether the sins were those specified by Christians or by talmudic rabbis hardly matters. This was a sinning generation.

In fact, it was not a sinning generation, but one deeply faithful to the covenant and to the Scripture that set forth its terms, perhaps more so than many who have since condemned it. First-century Israelites sinned only by their failure. Had they overcome Rome, even in the circles of the rabbis they would have found high praise, for success reflects the will of Providence. On what grounds are they to be judged sinners? The Temple was destroyed, but it was destroyed because of a brave and courageous, if hopeless, war against the Romans. That war was waged not for the glory a king or for the aggrandizement of a people, but in the hope that at its successful conclusion, pagan rule would be extirpated from the holy land. This was the articulated motive of the Jewish revolt that began in 66 -->A.D. --> It was a war fought explicitly for the sake of, and in the name of, God. The struggle called forth prophets and holy men, whom the people courageously followed past all hope of success. The Jews were not demoralized or cowardly, afraid to die because they had no faith in what they were doing. The 048 Jerusalemites fought with amazing courage, despite unbelievable odds. Since they lost, later generations looked for their sin, for none could believe that the omnipotent God would permit his Temple to be destroyed for no reason. As after 586 -->B.C. -->, so after 70 -->A.D. -->, the alternative was this, we might imagine the words of the time: “Either our fathers greatly sinned, or God is not just.” The choice thus represented no choice at all.

“God is just; we have sinned—we, yes, but mostly our fathers before us. That is why all this has come upon us—the famine, the exile, the slavery to pagans—these are just recompense for our own deeds.”

During the period just before the destruction of the Temple, the period when Jesus lived, there was no such thing as “normative Judaism” from which one or another “heretical” group might diverge. Not only in the great center of the faith, Jerusalem, do we find numerous competing groups, but throughout the country and abroad we may discern a religious tradition in the midst of great flux. It was full of vitality, but in the end without a clear and widely accepted view of what was required of each individual, apart from acceptance of Mosaic revelation. And this could mean whatever you wanted. People would ask one teacher after another, “What must I do to enter the kingdom of heaven?” precisely because no authoritative answer existed.

In the period before the Roman destruction of the Temple, some Jews withdrew completely. The monastic commune at Qumran near the shores of the Dead Sea where the famous scrolls were found was one such group. To the barren heights overlooking the barren Rift Valley came people seeking purity and hoping for eternity. The purity they sought was not from common dirt, but from the uncleanness of this world. In their minds, this age was impure and therefore would soon be coming to an end. Those who wanted to do the Lord’s service should prepare themselves for a holy war at the end of time. Men and women came to Qumran with their property, which they contributed to the common fund. There they prepared for a fateful day, not too long to be postponed, scarcely looking backward at those remaining in the corruption of this world. These Jews would be the last, smallest, “saving remnant” of all. Yet, through them, all humankind would come to know the truth. Strikingly, they held that God himself had revealed to Moses the very laws they now obeyed.

Pharisees, probably meaning Separatists, also believed that all was not in order with the world. But they chose another way, likewise attributed to Mosaic legislation. They remained within the common society in accordance with the teaching of their leading sage Hillel: “Do not separate yourself from the community.” The Pharisaic community therefore sought to rebuild society on its own ruins with its own mortar and brick. The Pharisees actively fostered their opinions on tradition and religion among the whole people. According to the first-century Jewish historian Josephus, the Pharisees “are able greatly to influence the masses of people. Whatever the people do about divine worship, prayers, and sacrifices, they perform according to their direction. The cities give great praise to them on account of their virtuous conduct, both in the actions of their lives and their teachings also” (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 13:171–173).

Though Josephus exaggerated the extent of their power, the Pharisees certainly exerted considerable influence in the religious life of Israel before they finally came to power in 70 -->A.D. -->

Among those sympathetic to the Pharisaic cause were some who entered into an urban religious communion, a mostly unorganized society known as the fellowship ( havurah ). The basis of this society was meticulous observance of laws of tithing and other priestly offerings, as well as the rules of ritual purity outside the Temple where the observance of such laws was not mandatory. Even profane foods (not sacred tithes or other offerings) the members undertook to eat in a state of rigorous levitical cleanness. At table, they compared themselves to Temple priests at the altar. These rules tended to segregate the members of the fellowship, for they ate only with those who kept the law as they thought proper. The fellows thus mediated between the obligation to observe religious precepts and the injunction to remain within the common society. By keeping the rules of purity, the fellow separated from the common man, but by remaining within the towns and cities of the land, he preserved the possibility of teaching others by example.

Upper-class opinion was expressed in the viewpoint of still another group, the Sadducees. They stood for strict adherence to the written word in religious matters, conservatism in both ritual and belief. Their name probably derived from the priesthood of Zaddoq, established by King David ten centuries earlier. They acknowledged Scripture as the only authority, themselves 049 as its sole arbiters. They denied that its meaning might be elucidated by the Pharisees’ allegedly ancient oral traditions attributed to Moses or by the Pharisaic devices of exegesis and scholarship. The Pharisees claimed that Scripture and the traditional oral interpretation were one. To the Sadducees, such a claim of unity was spurious and masked innovation. The two factions differed also on the eternity of the soul. The Pharisees believed in the survival of the soul, the revival of the body, the day of judgment and life in the world to come. The Sadducees found nothing in Scripture that to their way of thinking supported such doctrines. They ridiculed both these ideas and the exegesis that made them possible. They won over the main body of officiating priests and wealthier men. With the destruction of the Temple their ranks were, however, decimated. Very little literature later remained to preserve their viewpoint. In their day, however, the Sadducees claimed to be the legitimate heirs of Israel’s faith. Holding positions of power and authority, they succeeded in leaving so deep an impression on society that even their Pharisaic, Essenian and Christian opponents did not wholly wipe out their memory.

The Sadducees were most influential among land holders and merchants, the Pharisees among the middle and lower urban classes, the Essenes among the disenchanted of both these classes. These classes and sectarian divisions manifested a vigorous inner life, with politics revolving about peculiarly Jewish issues such as matters of exegesis, law, doctrine and the meaning of history. The vitality of Israel would have astonished the Roman administration, and when it burst forth, it did.

The rich variety of Jewish religious expression in this period ought not to obscure the fact that for much of Jewish Palestine, Judaism was a relatively new phenomenon. Herod, who was of Idumean stock, was the grandson of pagans. Similarly, the entire Galilee had been converted to Judaism only 120 years before the Common Era. In the later expansion of the Hasmonean kingdom that preceded Herod’s rule, outlying regions were forcibly brought within the Jewish fold. The Hasmoneans used Judaism imperially, as a means of winning the loyalty of the pagan Semites in the regions of Palestine they conquered. But in a brief period of three or four generations the deeply rooted pagan practices of the Semitic natives of Galilee, ldumea and other areas could not have been wiped out. They were rather covered over with a veneer of monotheism. Hence the newly converted territories, though vigorously loyal to their new faith, were no more Judaized in so short a time than were the later Russians, Poles, Celts or Saxons Christianized within a century. It took a great effort to transform an act of circumcision of the flesh, joined with a mere verbal affirmation of one God, made under severe duress, into a deepening commitment of faith. Only after many generations was the full implication of conversion realized in the lives of the people in Galilee, and then mainly because great centers of tannaitic law e and teaching had been established among them.

In the end, two groups emerged—the Christians and the rabbis, the latter the heirs of the Pharisaic sages. Each offered an all-encompassing interpretation of Scripture, explaining what it did and did not mean. Each promised salvation for individuals and for Israel as a whole.

Of the two, the rabbis achieved somewhat greater success among the Jews. Wherever the rabbis’ view of Scripture was propagated, the Christian view of the meaning of biblical, especially prophetic, revelation and its fulfillment, made relatively little progress. This was true, not only in Jewish Palestine itself, but in certain cities in Mesopotamia, and in central Babylonia. Where the rabbis were not to be found, as in Egyptian Alexandria, Syria, Asia Minor, Greece and in the West, Christian biblical interpretation and salvation through Christ risen from the dead found a ready audience among the Jews. It was not without good reason that the gospel tradition of Matthew saw in the “scribes and Pharisees” the chief opponents of Jesus’ ministry. Whatever the historical facts of that ministry, the rabbis proved afterward to be the greatest stumbling block for the Christian mission to the Jews.