- Guides & Resources

How To Write an Op-ed: A Step By Step Guide

There’s a formula that we call the “ABCs” that can be used to write compelling op-eds, columns, or blogs. The same formula can also be used to write almost any document that offers up an argument or gives advice. This is a “news flash lede,” a comment that will make sense in a moment .

The ABC Formula

This formula for writing op-eds is based on our experience and our op-eds that appeared in the New York Times , the Wall Street Journal , and the Washington Post . I first came across a version of this formula while I was at US News and World Report . It was called “FLUCK,” and we have tweaked it a bit since then.

This is probably obvious, but this ABC formula is meant to guide writers rather than restrict them. In other words, these are recommendations, not a rigid set of instructions.

Better yet, think of the formula as a flexible template for making an effective argument in print—one that you personalize with your specific style, topic, and intended audience in mind.

This guide is divided into five parts.

Part I: Introduction: In this section, we give a brief overview of the approach and discuss the importance of writing and opinion.

Part II: The ABCs: Here we cover the important steps in writing for your audience: Attention, Billboard, and Context.

PART III: The ABCS in Example: In this section, we give you different examples of the ABCs in action and how to effectively use them.

PART IV: Pitching: Here we will go over how to effectively pitch ideas and submit ideas to an editor for publication.

PART V: Final tips and FAQs: Here we go over a few more key things to do and answer the most commonly asked questions.

Part I: Introduction To Op-Eds

Op-eds are one of the most powerful tools in communications today. They can make a career. They can break a career.

But there’s often lots of mystery around editorials and op-eds. I mean: What does op-ed even stand for?

Well, let’s start with editorials. Editorials are columns written by a member of a publication’s board or editors, and they are meant to represent the view of the publication. While reporting has the main purpose of informing the public, editorials can serve a large number of purposes. But typically editorials aim to persuade an audience on a controversial issue.

Op-eds, on the other hand, are “opposite the editorial” page columns. They began as a way for an author to present an opinion that opposed the one on the editorial board. Note that an op-ed is different than a letter to the editor, which is when someone writes a note to complain about an article, and that note is published. Think of a letter to the editor as an old, more stodgy form of the comments section of an article.

The New York Times produced the first modern op-ed in 1970, and over time, op-eds became a way for people to simply express their opinions in the media. They tend to be written by experts, observers, or someone passionate about a topic, and as media in general becomes more partisan, op-eds have become more and more common.

How to start . The first step for writing an op-ed is to be sure to: Make. An. Argument.

Many op-eds fail because they just summarize key details. But, wrong or right, op-eds need to advance a strong contention. They need to assert something, and the first step is to write down your argument.

Here are some examples:

- I want to write an op-ed on the plague that are drinks that overflow with ice cubes. This op-ed would argue that restaurants serve drinks with too many ice cubes.

- Superman is clearly better than Batman. In this op-ed, I would convince readers why Superman is a better superhero than Batman.

- My op-ed is on lowering the voting age in America. An op-ed on this topic would list reasons why Congress should pass a law to allow those who are 14 years old like me to be able to vote in elections.

How to write. So you have yourself an argument. It’s now time to write the op-ed. When it comes to writing, this guide assumes a decent command of the English language; we’re not going to cover the basics of nouns and verbs. However, keep in mind a few things:

- Blogs, op-eds, and columns are short. Less than 1,000 words. Usually between 500 and 700 words. Many blogs are just a few hundred words, basically a few graphs and a pull quote often does the job.

- Simplicity, logic, and clarity are your best friends when it comes to writing op-eds and blogs. In other words, write like a middle schooler. Use short sentences and clear words. Paragraphs should be less than four sentences. Please take a look at Strunk and White for more information. I used to work with John Podesta, who has written many great op-eds, and he was rumored to have given his staff a copy of Strunk and White on their first day of employment.

- Love yourself topic sentences. The first sentence of each paragraph needs to be strong, and your topic sentences should give an overall idea of what’s to follow. In other words, a reader should be able to grasp your article’s argument by reading the first sentence of each paragraph.

How to make an argument. This guide is not for reporters or news writers. That’s journalism. This guide is for people who make arguments. So keep in mind the following:

- Evidence . This might be obvious, but you need evidence to support your argument. This means data in the forms of published studies, government statistics, and anything that offers cold facts. Stories are good and can support your argument. But try and go beyond a good anecdote.

- Tone . Check out the bloggers and columnists that are in the publications that you’re aiming for, and try to emulate them when it comes to their argumentative tone . Is their tone critical? Humorous? Breezy? Your tone largely hinges on what type of outlet you are writing for, which brings us to…

- Audience . Almost everything in your article — from what type of language you use to your tone — depends on your audience. A piece for a children’s magazine is going to read differently than, say, an op-ed in the Washington Post. The best way to familiarize yourself with your audience is to read pieces that have already been published in the outlet you are writing for, or hoping to write for. Take note of how the author presents her argument and then adjust yours accordingly.

Sidebar: Advice vs Argument. Offering advice in the form of a how-to article — like what you’re reading right now — is different than putting forth an argument in an actual op-ed piece.

That said, advice pieces, like this one by Lifehacker or this one by Hubspot, follow much of the same ABC formula. For instance, advice pieces will still often begin with an attention-grabbing opener and contextualize their subject matter.

However, instead of trying to make an argument in the body of the article, the advice pieces will typically list five to ten ways of “how to do” something. For example, “How to cook chicken quesadillas” or “How to ask someone out on a date.”

The primary purpose of an advice piece is to inform rather than to convince. In other words, advice pieces describe what you could do, while op-ed pieces show us what we should do.

Part II: Dissecting The ABC Approach

Formula. Six steps make up the ABC method, and yes, that means it should be called the ABCDEF method. Either way, here are the steps:

Attention (sometimes called the lede): Here’s your chance to grab the reader’s attention. The opening of an opinion piece should bring the reader into the article quickly. This is also sometimes referred to as the flash or the lede, and there are two types of flash introductions. They are: Option 1. Narrative flash . A narrative flash is a story that brings readers into the article. It should be some sort of narrative hook that grabs attention and entices the reader to delve further into the piece. A brief and descriptive anecdote often works well as a narrative flash. It simultaneously catches the reader’s attention and hints at the weightier argument and evidence yet to come.

When I first started writing for US News, I wrote a flash lede to introduce an article about paddling school children. Here’s that text:

Ben Line didn’t think the assistant principal had the strength or the gumption. But he was wrong. The 13-year-old alleges that the educator hit him twice with a paddle in January, so hard it left scarlet lines across his buttocks. Ben’s crime? He says he talked back to a teacher in class, calling a math problem “dumb.”

Option 2. News flash . Some pieces — especially those tied to the news — can have a lede without a narrative start. Other pieces, including many op-eds, are simply too short to begin with a narrative flash. In either of these instances, using the news flash as your lede is likely your best bet.

If I were writing a news flash lede for the paddling piece, I might start with something as simple as: Congress again is considering legislation to outlaw paddling.

- Billboard (also often called the nut graph): The billboard portion of the lede should do two things:

First, the “billboard” section should make an argument that elevates the stakes and begins to introduce general evidence and context for the argument. So start to introduce some general evidence to support your argument in the nut portion of the lede.

For an example of a nut graph for a longer piece on say, sibling-on-sibling rivalry, consider the following: The Smith sisters exemplify a disturbing trend. Research indicates that violence between siblings—defined as the physical, emotional, or sexual abuse of one sibling by another, ranging from mild to highly violent—is likely more common than child abuse by parents. A new report from the University of Michigan Health System indicates the most violent members of American families are indeed the children. Data suggests that three out of 100 children are considered dangerously violent toward a brother or sister, and nine-year-old Kayla Smith is one of those victims: “My sister used to get mad and hit me every once in a while, but now it happens at least twice a week. She just goes crazy sometimes. She’s broken my nose, kicked out two teeth, and dislocated my shoulder.”

Second, the billboard should begin to lay the framework of the piece and flush out important details—with important story components like Who, What, When, Where, How, Why, etc. A good billboard graph often ends with a quote or call to action. Think of it like this: if someone reads only your “billboard” section, she should be able to grasp your argument and the basic details. If you use a narrative flash lede, then the nut paragraph often starts with something like: They are not alone. So in the padding article, for instance, the nut might have been: “Ben is not alone. In fact, 160,000 students are subject to corporal punishment in U.S. schools each year, according to a 2016 social policy report.”

For another example, here’s a history graph from a recent op-ed by John Podesta that ran in the Washington Post :

“To give some context: On Oct. 7, 2016, WikiLeaks began leaking emails from my personal inbox that had been hacked by Russian intelligence operatives. A few days earlier, Stone — a longtime Republican operative and close confidant of then-candidate Donald Trump — had mysteriously predicted that the organization would reveal damaging information about the Clinton campaign. And weeks before that, he’d even tweeted: ‘Trust me, it will soon [be] Podesta’s time in the barrel.’”

If you’re writing an advice piece, then similar advice applies. A how-to guide for Photoshop, for example, might include recent changes to the program and information on the many ways that Photoshop can be used to edit pictures.

- Demonstrate: In this section, you must offer specific details to support your argument. If writing an op-ed, this section can be three or four paragraphs long. If writing a column, this section can be six or ten paragraphs long. Either way, the section should outline the most compelling evidence to support your thesis. For my paddling article, for instance, I offered this argument paragraph: The problem with corporal punishment, Straus stresses, is that it has lasting effects that include increased aggression and social difficulties. Specifically, Straus studied more than 800 mothers over a period from 1988 to 1992 and found that children who were spanked were more rebellious after four years, even after controlling for their initial behaviors. Groups that advocate for children, like the American Academy of Pediatrics and the National Education Association, oppose the practice in schools for those reasons.

While narrative can be vital when capturing a reader’s attention, it’s equally important to offer hard facts in the evidence section. When demonstrating the details of your argument, be sure to present accurate facts from reputable sources. Studies published in established journals are a good source of evidence, for instance, but blogs with unverified claims are not.

Also, when providing supporting details, you should think about using what the Ancient Greeks called ethos, pathos, and logos. To explain, ethos refers to appeals based on your credibility, that you’re someone worth listening to. For example, if you are arguing why steroids should be banned in baseball, you might talk about how you once used steroids and their terrible impact on your health.

Pathos refers to using evidence that plays to the emotions. For example, if you are trying to show why people should evacuate during hurricanes, you might describe a family who lost their seven-year-old child during a hurricane.

Logos refers to logical statements, typically based on facts and statistics. For example, if you are trying to convince the audience why they should join the military when they are young, provide statistics on their income when they retire and the benefits they receive while in the military.

- Equivocate : You should strengthen your argument by including at least one graph that briefly describes—and then discounts—the strongest counterargument to your point. This is often called the “to be sure” paragraph, and it hedges your bets about the clarity of your piece with phrases such as “to be sure” or “in other words.”Here’s an example from a recent op-ed in Bloomberg: Of course, that doesn’t mean that Hispanics simply change while other Americans stay the same. In his 2017 book “The Other Side of Assimilation: How Immigrants Are Changing American Life,” Jimenez recounts how more established American groups change their culture and broaden their horizons based on their personal relationships with more recently arrived immigrant groups. Assimilation isn’t slavish conformity to white norms, but a two-way process where the U.S. is changed by each new group that arrives.

- Forward : This is where you wrap up your piece. It carries greater impact, though, if you can write an ending that has some oomph to it and really looks forward. So try to provide some parting thoughts and, when appropriate to the topic, draw your readers to look toward the future. If you began with a narrative flash lede, it’s optimal whenever possible to find a way to tie back into that introductory story. It allows you to simultaneously finalize the premise of your argument and neatly conclude your article. In an op-ed about gun violence that ran last year, minister Jeff Blattner looks toward the future and seamlessly ties the end of his piece back to his lede with this simple but effective kicker: If we don’t commit ourselves to solving them together—to seeing one another as part of a bigger “us”—we may reap a whirlwind of ever-widening division. Let Pittsburgh, in its grief, show us the way.

An op-ed needs to advance a strong contention. It needs to assert something, and and the first step is write down your argument.

Part III: The ABCs In Example

Now that we have gone over the basic ABC formula, let’s examine a recent blog item and identify the six ABC steps.

Written by E.A. Crunden, the piece appeared in ThinkProgress and is titled, “ Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke is embroiled in more than one scandal .”

- Attention : “A controversial contract benefiting a small company based in his hometown is only the latest possible corruption scandal linked to Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke…” This opening sentence introduces the most recent news on Zinke while also signaling that other scandals might be discussed in the article.

- Billboard : “On Monday, nonprofit watchdog group the Campaign Legal Center (CLC) accused Zinke’s dormant congressional campaign of dodging rules prohibiting individuals from converting political donations into individual revenue.” The second paragraph adds more information about Zinke’s alleged missteps.

- Context : “Zinke’s other ethical close-calls, as the CLC noted, are plentiful.” This provides some background to the main argument and lets the reader know that Zinke has a long history of questionable ethics, which the author expands upon in the following paragraphs.

- Demonstrate : “As a Montana congressman, Zinke took thousands of dollars in campaign contributions from oil and gas companies, many of whom drill on the same public lands he now oversees…” Here the author gives specific evidence of Zinke’s actions that some believe to be unethical. This fortifies the argument. The following few paragraphs continue in this vein.

- Equivocate : “I had absolutely nothing to do with Whitefish Energy receiving a contract in Puerto Rico,” the interior secretary wrote in a statement on Friday.” In this case, the equivocation appears in the form of a counterargument. The writer goes on to dismiss it by presenting additional clarifying evidence to support his point.

- Forward: “Monday’s complaint comes amid a Special Counsel investigation into Zinke’s spending habits, as well as a separate investigation opened by the Interior Department’s inspector general. Audits into Puerto Rico’s canceled contract with Whitefish Energy Holdings are also ongoing.” These final two sentences “zoom out” from the specifics of the article, showing that the main news item (i.e., Zinke’s poor ethics) will continue to be relevant in the future. These forward-looking sentences also circle back neatly to the point of the flash news lede by reiterating that “Monday’s complaint” is yet another in a growing list against Zinke.

Part IV: Pitching

When it comes to op-eds, most outlets want to review a finished article. In other words, you write the op-ed and then shop it around to different editors. In some cases, the outlet might want a pitch — or brief summary— of the op-ed before you write it.

Either way, you’ll need a short summary, even just a few sentences that describe your argument. Here is an example of the pitch that I wrote that landed me on the front page of the Washington Post’s Outlook section. Note that this pitch is long, but I was aiming for a more feature-like op-ed.

I wanted to pitch a first-person piece looking at Neurocore, the questionable brain-training program that’s funded by Betsy DeVos.

DeVos just got confirmed as Secretary of Education, and for years, she’s been one of the major investors in Neurocore. Located in Michigan and Florida, the company makes some outlandish promises about brain-based training. The firm has argued, for instance, that its neuro-feedback programs can increase a person’s IQ by up to 12 points.

I was going to take Neurocore’s diagnostic program to get a better sense of the company’s claims. As part of the story, I was also going to discuss the research on neuro-feedback, which is pretty weak. Insurance companies are also skeptical, and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan recently refused to reimburse for Neurocore’s treatments. I’d also discuss some of my research in this area and talk about some of the dangers of spreading myths about learning.

There’s been some recent coverage of Neurocore. But the articles have typically focused on the conflict of interest posed by the company since DeVos herself has refused to disinvest. What’s more, no one appears to have written a first-person piece describing the experience of attending one of their brain training diagnostic sessions.

A few bits of advice:

- Newsy. Whenever possible, build off the news. A good way to drum up interest in your piece is to connect it to current events. People naturally are interested in reading op-eds that are linked to recent news pieces — so, an op-ed on Electoral College reform will be more relevant around election season, for instance. It’s often effective to pitch your piece following a major news event. Even better if you can pitch your op-ed in advance; for example, a piece on voter suppression in the United States might be pitched in advance of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. Here’s an article from McGill University that has some advice on this idea.

- Tailor. Again, in this step of the process, it’s worth considering the audience of the publication. For example, if you’re writing in the business section of a newspaper, you’ll want to frame the article around business. If you are writing for a sports magazine, you’ll want to write about topics like “Who is the greatest golfer of all time, Tiger Woods or Jack Nicklaus?”

Also, websites sometimes have information on pitching their editors. Be sure to follow whatever specific advice they give — this will improve your chances of catching an editor’s eye.

Advice pieces describe what you could do, while op-ed pieces show us what we should do.

Part V: FAQs And Tips

I have lots to say. Can I write a 3,000-word op-ed?

Not really. Most blog articles, op-eds, and columns are short. What’s more, your idea is more likely to gain traction if it’s clear and simple. Take the Bible. It can be broken down to a simple idea: Love one another as you love yourself. Or take the Bill of Rights. It can be shortened to: Individuals have protections.

I want to tell a story. Can I do that?

Maybe. If you do, keep it short and reference the story at the top and maybe again at the bottom. But again, the key to an op-ed is that it makes an argument.

What should do before I hit submit?

We could suggest two things:

- Make sure you cite all your sources. Avoid plagiarism of any kind. If you’re in doubt, provide a citation via a link or include endnotes citing your sources.

- Check your facts. The New York Times op-ed columnist Bret Stephens says it this way: “Sweat the small stuff. Read over each sentence—read it aloud—and ask yourself: Is this true? Can I defend every single word of it? Did I get the facts, quotes, dates, and spellings exactly right? Yes, sometimes those spellings are hard: the president of Turkmenistan is Gurbanguly Malikguliyevich Berdymukhammedov. But, believe me, nothing’s worse than having to run a correction.” For more guidance, see Stephen’s list of tips for aspiring op-ed writers .

- Read it out loud. Before I submit something, I’ll read it out loud. It helps me catch typos and other errors. For more on talking out loud as a tool, see this article that I pulled together some time ago.

What’s the difference between a blog article and an op-ed?

A blog article can be about anything such as “What I had for lunch today” or “Why I love Disney World.” An op-ed typically revolves around something in the news and is meant to be persuasive. It typically runs in a news outlet of some kind.

What if no one takes my op-ed?

Be patient. You might need to offer your op-ed to multiple outlets before someone decides to publish it, and you can always tweak the op-ed to make it more news-y, tying the article to something that happened in the news that day or week.

Also, look for ways to improve the op-ed. You might, for instance, focus on changing the “attention” section to make it more creative and interesting or try to improve the context section.

What is the best way to start writing an op-ed?

Before writing, make sure to create an outline. I will often write out my topic sentences and make sure that I’m making a strong, evidence-based argument. Then I’ll focus on a creative way to open my op-ed.

Don’t worry if you get writer’s block while writing the “attention” step. You can always come back and make it more interesting. Really, the most important step is having an outline.

Should I hyperlink?

Yes, include hyperlinks in your articles to provide your readers with easy access to additional information.

–Ulrich Boser

16 thoughts on “How To Write an Op-ed: A Step By Step Guide”

Thanks for this excellent refresher!

I am writing this with the hope that the leasing of the port of Haifa will not come to fruition,It will give the Chinese a strong foothold in the middle east. No longer will the United States 6th fleet have a home away from home..May i remind those who are in command that NO OTHER COUNTRY in the world has helped Israel more than the US.and it would be a slap in the face of our best friend and cause many , many consequences in the future for the state of Israel. I pray to G-D that those in charge will come to their senses and hopefully cancel the agreement. M A, Modiin

Excellent piece of writing ideas, Thanks a lot for sharing these amazing tricks.

INTERESABTE TODA LA INFORMACION

Gracias, Julio!

Good information

So glad you enjoyed it!

Glad it was helpful. Did I miss something in your comment?

Well done, But it’s needs practice!! Hands on!

Write with is one of the most critical steps of the writing process and is probably relevant to the first point. If you want to get your blood pumping and give it your best, you might want to write with passion, and give it all you got. How do you do this? Make sure that you have the right mindset whenever you are writing.

Create a five-paragraph editorial about a topic that matters to you.

Reading this I realized I should get some more information on this subject. I feel like there’s a gap in my knowledge. Anyway, thanks.

Thank you very much for your really helpful tips. I’m currently writing a lesson plan to help students write better opinion pieces and your hands-on approach, if a bit too detailed for my needs, is truly valuable. I hope my students will see it the same way 😉

Great article! Will implement these own steps in my own top 10 website!

Thank you for sharing your expertise. Your advice on incorporating storytelling, providing evidence, and addressing counterarguments is invaluable for ensuring the effectiveness and persuasiveness of op-eds.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

More Insights

How Investment In Education R&D By Texas Policy Leaders Could Spur Economic Growth

Texas has a rich history as a leader in innovation. State policy leaders could help it have an even richer future as a leader in R&D education.

5 Questions With Alvin Irby of Barbershop Books

Alvin Irby of Barbershop Books discusses how adults can help children from underrepresented communities build their reading identity and develop a love of reading that can translate into academic gains.

Assessing ChatGPT’s Writing Evaluation Skills Using Benchmark Data

We tested ChatGPT’s default model’s performance for providing summative and formative feedback on student writing using two benchmarks for automated writing evaluation.

Stay up-to-date by signing up for our weekly newsletter

clock This article was published more than 1 year ago

Opinion The Washington Post guide to writing an opinion article

The Washington Post is providing this news free to all readers as a public service.

Follow this story and more by signing up for national breaking news email alerts.

Each month, The Washington Post publishes dozens of op-eds from guest authors. These articles — written by subject-matter experts, politicians, journalists and other people with something interesting to say — provide a diversity of voices and perspectives for our readers.

The information and tips below are meant to demystify our selection and editing process, and to help you sharpen your argument before submitting an op-ed of your own.

Op-Ed? Editorial? What do all these terms really mean?

Terms like op-ed can be confusing. let us explain them for you..

You've probably heard the term op-ed a lot recently. The New York Times' decision to publish an anonymous op-ed from a "senior official" in the Trump administration pulled the term into the national spotlight.

The op-ed has left people, including the president, asking who wrote this? What was the author's motive? Why would the Times agree to withhold the author's name? They're all valid questions, and ones we may never get answers to.

But we know from social media and data from search providers that it also left many people asking, what is an op-ed? As journalists, we have a responsibility to ensure our readers understand the terms we use.

Opinion sections publish several different types of content in the spirit of presenting a wide range of viewpoints and to encourage thoughtful debate. All of the different terms can get confusing. Here's a primer on all of the terms we use to describe content appearing in the Register's Opinion section.

What is an op-ed?

An op-ed, short for opposite editorial, is an opinionated article submitted to a newspaper for publication. They are written by members of the community, not newspaper employees.

Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines them as "an essay in a newspaper or magazine that gives the opinion of the writer and that is written by someone who is not employed by the newspaper or magazine."

In the Register, most op-eds are labeled as "Your Turn" or "Iowa View." They can also be called guest columns. Op-eds can range from public policy debates to first-person experiences.

SUPPORT LOCAL JOURNALISM: Start a Des Moines Register subscription today

HOW TO: Submit a guest essay

In recent weeks, we've published op-eds from Rob Tibbetts about how he didn't want his daughter Mollie's name used in immigration debates , advocates worried about how the Monsanto-Bayer merger will hurt farmers , a working mother on the need for the FAMILY Act to pass the U.S. Senate and Vice President Mike Pence touting the country's economic success before a visit to Des Moines.

Op-eds give the Register's opinion pages the opportunity to present views we wouldn't normally be able to publish. Opinion Editor Kathie Obradovich and planning editor James Kramer sift through dozens of submissions each week to decide which op-eds are published.

What's an editorial?

An editorial is an opinion article that states the position of a publication's editorial board, which usually consists of top editors and opinion writers. At the Register, that board includes Obradovich, Executive Editor Carol Hunter, Editorial Writer Andie Dominick and retired Register staffers Richard Doak and Rox Laird.

Recent editorials have questioned why Iowa's schools are suspending an increasing number of elementary students , advocated for making E-Verify mandatory as part of larger immigration reform and challenged lawmakers to ensure the war against opioids didn't leave cancer patients in pain .

Andie Dominick was awarded the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for editorial writing for a selection of editorials on health care and the state's decision to privatize Medicaid. The Pulitzer Prize citation states that Dominick won "for examining in a clear, indignant voice, free of cliché or sentimentality, the damaging consequences for poor Iowa residents of privatizing the state’s administration of Medicaid."

Dominick was a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2014 for a series of editorials challenging Iowa's licensing laws that regulate occupations ranging from cosmetologists to dentists and often protect practitioners more than the public. The Register also won Pulitzer Prizes for editorial writing in 1956, 1943 and 1938.

RELATED: Why do newspapers still have editorials?

Here's how the New York Times describes its editorial board : "Their primary responsibility is to write The Times’s editorials, which represent the voice of the board, its editor and the publisher. The board is part of the Opinion department, which is operated separately from The Times’s newsroom, and includes the Letters to the Editor and Op-Ed sections."

The Register uses the same separation in its newsroom.

What's a column?

A column is an article that often — but not always — contains opinions. Op-eds can be a type of column.

Columnists are often some of the most well-known names at a news organization. The Register's columnists include Rekha Basu (opinion), Iowa Columnist Courtney Crowder , Randy Peterson (Iowa State athletics), Chad Leistikow (Iowa athletics), Reader's Watchdog Lee Rood and Metro Columnist Daniel P. Finney . Obradovich was a political columnist before becoming opinion editor and continues to write columns .

Though uncommon, reporters occasionally express opinions by writing columns about topics on their beat.

Columns can be personal stories, like when Crowder wrote about crying at an "American Idol" concert , or calls to action, like when Obradovich wrote about the need for politicians to address mental health care in Iowa .

In addition to its staff columnists, the Register publishes columns from contributor Joel Kurtinitis and syndicated columns from writers like Leonard Pitts, Marc A. Thiessen and John Kass.

What's a letter to the editor?

A letter to the editor is a shorter, usually opinionated article written by a reader who wants to share an opinion about something they've just read or seen.

You can submit your own letter at DesMoinesRegister.com/Letters .

Submissions should be short — 200 words or less is ideal — but they can be about the topic of a reader's choosing. They can share a political opinion, criticize something the Register published or thank a helpful stranger.

All of these different types of content can be found on Opinion pages both online and in print of publications across the country.

Still left with questions?

As I wrote at the start of this article, it's up to journalists to ensure our readers understand the terms we use. If you're still unsure or you see another journalism term you don't understand, reach out to me and let's chat about it.

Brian Smith is the Register's engagement editor and served as a member of its editorial board from 2014-2017. He's a native Iowan and graduate of Iowa State University. Brian works with Register journalists to help them connect with Iowans through social media, events and more. Reach him at [email protected] , 515-284-8214, @SmithBM12 on Twitter or at Facebook.com/SmithBM12

— USA TODAY NETWORK's Ethan May contributed to this report.

How to write an Op-Ed or Guest Opinion Essay

Unlike a standard academic essay where you are required to strictly maintain an academic tone, not to use first-person (or at least use it only in some essays), and use certain academic phrases , writing an opinion article or Op-Ed allows you the freedom but your writing skills must be top-notch. This is why we have written this comprehensive guide to guide you through writing an Op-Ed essay.

If you are a professional, student, or layperson who wants someone to write your Op-Ed, guest opinion, or guest essay for publication, you can hire a ghostwriter on our website. They are adaptable, flexible, and knowledgeable enough.

However, if you intend to learn how to write an Op-Ed and do it yourself, flip through these few headings and subheadings to find what can help you hone your skills. These insights have been sought and compiled from our editorial team, researchers, and top writers who have produced world-class Op-Eds for different individuals.

These guidelines also borrow ideas from top Op-Ed writers and resources over the internet. In addition, we have condensed information to make it easier for you to plan, craft, and submit a top-of-the-grade Op-Ed.

Let's dig deep and see what we have here. In a nutshell, the article covers the contents displayed below.

Table of Contents

What is an op-ed essay, what is the purpose of the op-ed essay, how long is an op-ed essay, who writes an op-ed essay.

- Steps to writing an Op-Ed Essay

Tips and tricks when writing an Op-Ed Essay

Dos and don'ts when writing an op-ed essay, format of an op-ed essay, having trouble with your op-ed or guest essay paper.

When you think Op-Ed , the names Herbert Bayard Swope and Michael Socolow come into mind. These were the brilliant minds behind what would today be known as Op-Ed, although recently a retired label by The New York Times, and henceforth known as Guest Essays .

An Op-Ed, a short name for opposite the editorial page refers to a written piece of prose published in a magazine or a newspaper where the author expresses their opinion on a given issue. The author, in this case, is never affiliated with the editorial board of the publication.

In this opinion piece from contributors not affiliated with the editorial board, you must show that your writing skills are worth the salt. Being published in a top national paper or at least scoring the entire total grade in a class-assigned Op-Ed essay is no joke.

When you understand how to write and actually write a strong Op-Ed essay, you will have proven that you have mastered a real-world writing skill that you need to succeed anywhere in this age of competition : it's a unique competitive advantage.

Op-Ed or guest essays are meant to help the readers of a publication to understand the world. It enables people who are not journalists or have no affiliation to the editorial boards to speak directly to the readers without the mediation of the reporters. These Op-Eds often present arguments and voices that either dissent or diverge from the editorials ( opinion pieces submitted by the editorial board members) or columnists.

The pieces are meant to give the readers robust, distinctive, and wide-ranging arguments and ideas on specific issues. They are also intended to sway public opinion and change minds by presenting convincing arguments in a concise, clear, and readable format.

As an assignment, an Op-Ed reflects the real-world applications outside the classroom. So, for instance, you can use the critical race theory or any other theory to diffuse inequalities in society.

They are also used to assess the accomplishment of learning outcomes at any level of the cognitive domain of Bloom's Taxonomy. So, for instance, you can be evaluated based on how you defend your position on the budget crisis or how you explain your thoughts on using innovative technologies in higher education.

Most newspaper outlets limit Op-Eds to 700-1200 words, four pages double-spaced in an academic format. As per the new guidelines by The New York Times, the word count should be between 800 and 1200 words. Nevertheless, shorter or longer essays are sometimes published. When writing an Op-Ed for publication, strive to reach at least 750 or 800 words.

Op-Eds are written by members of the public not affiliated with the publishing institution. They are printed opposite the editorials written by the newspaper staff. The modern Op-Ed is published online thanks to the advancement in technology.

In many cases, when submitting your work for consideration, you are required to declare your professional, personal, or academic background that connects you to the idea or arguments in your essay.

Steps on how to write an Op-Ed Essay

So, you are now ready to take it to a higher notch and write an A-grade or noteworthy Op-Ed? First, let's set you up with some of the seven easy steps to writing an opinion editorial article in any niche and nail it properly.

Step 1: Conduct thorough research

When writing an Op-Ed, you need to begin by researching to find out what is recent happening around the niche you've chosen. Consider the hot topic, general perspective of the public, any changes in legislation or laws in the marketplace, and pretty much new occurrences.

It would help if you did research on high-profile websites in your chosen niche, check social media pages, or check forums. But, equally, focus on the scholarly resources that support what you are writing about.

Good research puts you on a pedestal towards writing a convincing Op-Ed that attracts readership and gets you good grades.

Step 2: Choose a workable position

When researching, you will notice that you will develop a thesis or a central claim. Choosing a position on an issue helps you grow your voice, choose your words, and resonate with the readers. So instead of being on the fence, choose a side and stand by it. It is either you like it or totally don't. It is either relevant or irrelevant.

Choosing a position also helps you to own an opinion. Our ghostwriters are so keen because this is the point where the problem sets in. however, as long as you tell your writer what perspective to take, you are good to go. They are so good at adopting the role of the opinion until the work is over.

When you own an idea off the bat, you will be able to nail the call-to-action or call for further thought over an issue and win the trust of your readers.

Step 3: Draft your Op-Ed

Once you have chosen your position, you need to carefully choose your title, hook, thesis statement , body paragraphs, and the call-to-action.

Begin writing your Op-Ed with a sound hook that relates to the issue alongside a story that personalizes it to the readers and yourself. As you make the hook, be very brief. For instance, if a shooting was reported in the news, and your Op-Ed supports measures to control gun ownership, briefly cover the gun death statistics or make a relatable story to it.

Focus on what each paragraph will entail and how you plan to end the essay with a call-to-action.

Step 4: Include supporting facts and examples

When writing your personal opinions, you need evidence and support to make them relevant, believable, and insightful. Use the data, facts, and statistics from scholarly sources to reinforce points in your Op-Ed. In addition, you can use historical facts, figures, and quotes to bolster the case that you are making.

Remember, when writing an opinion article, you might be tempted to leave out the sources. However, using external sources helps you stand out as a credible, deep, and insightful expert. Mostly, the body paragraphs are solutions you propose to be implemented.

Step 5: Avoid generalizations and overdoing it

When writing, avoid generalizing issues. Instead, be as direct and specific as possible lest you confuse your readers. On the same tone, write the paper in simple terms and let it attract attention, drive traffic, or whatever its intention is. In the case of a classroom assignment, write an Op-Ed that meets the requirements for a top grade on your rubric. Having a perfectionist mindset and approach can ruin the happiness and sweetness in writing an Op-Ed.

Step 6: Have a call to action

The call to action is usually your concluding paragraph. It should remind the reader that solving the problem or addressing the issue might take time, dedication, and cooperation, but it is worth all the efforts. Finally, invite the readers to become part of the solution from their own angle.

Step 7: Proofread, Edit, and Polish

Avoid jargon or industry-speak to ensure that your audience is not confused or limited. Make sure that the concepts, theories, and any complex terms are explained to broaden the understanding of the readers and encourage them to think. An Op-Ed should be devoid of grammar, stylistic, formatting, and spelling mistakes. Therefore, ensure that your essay is well-polished.

When assigned to write an opinion over an interesting issue, it is a chance to persuasively and clearly express your opinion in an Op-Ed article. You are going to reach a mammoth of people, change minds, reshape public opinion or policy, and sway hearts. If your institution is publishing the Op-Ed, you would probably win accolades, recognition, and significant publicity compared to the sweat and tears it takes to be published in a professional journal article. To nail it and leave everything else to chance, of course with higher success chances, here are some tips and tricks to guide your writing process:

Look, listen, and think around the news

The timing of your Op-Ed is usually very critical. Therefore, choose to write when an issue is dominating the news. For instance, check news relating to innovation, wars, diseases, pandemics, stock markets, economies, or controversial celebrity news from a reality show. Also, ensure that it is an issue that you can link to your area of study.

Avoid Jargon

By any chance, avoid using technical terms of jargon as they have no place in your arguments. Instead, make it as easy as possible for the audience to resonate with your ideas. If you are in doubt about a given vocabulary, leave it out. Using simple language means that you are considerate of the lay readers : you're simply taking care of anyone.

Embrace your personal voice

When assigned to write an Op-Ed, write it in your personal voice. It is easier to resonate with the readers if you are speaking from experience. Technically, this means that your hook must be strong enough and founded on your personal experiences with the issue or problem. While academics tend to avoid first-person in professional journals, you have the freedom to incorporate your ideas here. Doing so helps you connect with the reader to care to read and understand what you are saying attentively. Even more important, the personal voice gives you as a student or a person with no fancy title or degree leverage to capture the attention of the readers.

Put your main point on top

Since you are not writing scientific journals that require a systematic approach, reveal your punchline off the bat. An Op-Ed is technically the opposite of a scholarly article; you have 10 seconds or less to hook the busy reader, so put aside the witticism and the historical facts. Instead, penetrate the mind of your reader by getting directly to the point, convincing them, and giving them a reason to even read past the first few lines.

Focus on a single point or issue

You have between 600 and 1200 words to handle an issue. So, the shorter your Op-Ed is, the better. On the other hand, it is impossible to solve all the problems in the world in around 750 words. Therefore, cut down your lengthy opinion article to size : it helps you get published without rejection.

Let your audience know why they should care

When you dawn the shoes of a busy reader looking at your article, you will most likely want yourself to know what's going on. Therefore, every few paragraphs remind the readers about why they should care (so what? Why now? Who care? Why should I care?) and whatnots. Appeal to self-interest instead of having some abstract punditry.

Use shorter sentences

Be concise, clear, and coherent when writing your opinion article. Some publications count characters, words, and sentences. Therefore, use shorter sentences, mainly declarative sentences, to ease the reading for your audience. If possible, cut the long paragraphs into two or more balanced paragraphs.

Offer specific recommendations

An op-ed is an opinion about how to improve a situation. Therefore, make it live up to its name. Do not just stick to a mere classroom analysis. Instead, extend your argument by providing specific recommendations to specific bodies, organs, and people. For example, you can suggest that opposing parties reconcile their differences or need more collaborative research.

Use Active Voice

Active voice is better than passive voice. It improves the reading with ease ratings, which makes your Op-Ed readable and relatable. With such easy-to-read pieces, the audience can resonate with the whole point of the Op-Ed. Besides, you leave no doubt about recommending action or proposing a solution.

Make a killer ending

The ending of your Op-ed should be a winner in the aspect that you summarize your argument strongly. Let it reflect how the thesis of the op-ed has been supported. Most casual readers will skim through the conclusion to gauge if the op-ed is worth their time. Mostly, concluding with a thought or phrase that appeared in your strong opening closes the circle, which is a plus for a keen reader.

Acknowledge the other side of the debate

Instead of piling one reason after the other, why you are wrong, and the opponent is wrong. Instead, appeal to the readers concerning the other side of the debate. That way, you intellectually bring the debate to the table and leave your readers to decide which works for them.

Use examples to show rather than discuss

Humans have a short memory that can be jogged by examples that paint colorful details compared to dry facts. You can leverage this when writing your Op-ed essay. Include great examples that breathe life into your arguments.

Here are some dos and taboos when writing an Op-ed either as a school assignment or for newspaper/magazine publication.

- Think of a topic based on an issue that interests you. In most cases, you can use your interests or focus on a topic assigned from class based on the theories covered. For instance, you can focus on student athletics or gender bias in politics.

- Ground your opinions on the specific subject or your Major. You should ensure that you back up your arguments with a credible scholarly study from your field. It helps you prove your thesis statement.

- Hook your piece to a recent occurrence in the world. For instance, you can focus on the global pandemic, exodus from Afghanistan, drought, climate change, and any other recent occurrences. Make your hook very recent, national, local, or international.

- Use short sentences and paragraphs

- Have a reasonable, concise, and clear title

Don'ts

- Avoid unnecessary rebuttals. Do not do a point-by-point rebuttal when writing in response to an earlier piece that chilled your blood. Such pettiness is unwelcomed and uncalled for in the op-ed world.

- Avoid using jargon and industry-speak

- Avoid using passive voice

- Avoid using long paragraphs and long sentences

- Do not worry too much about the headline if it is for newspaper publication; the newspaper staff consistently crafts the best.

Examples of Professionally Written Op-Ed (Guest Opinion)

Here are some excellent examples of Op-Eds written and published in Newspapers and Magazines

- Sheryl Sandberg on the Myth of the Catty Woman

- Why the internet should win a Nobel prize

- Stop Hate influencers

- How changeable is gender?

- Bring back high school librarians

- LAUSD's students need better libraries, not iPads

- Closing School Libraries and Cutting Certified Librarians Does Not Make Sense

- Betrayed by Obama

- Stop playing defense on Hate crimes

Op-Eds take many formats, including:

- Communication from influencers/ public figures - written by public officials to explain their position or tell stories. These personalities are already famous on many platforms, and their essays are held with high regard and standards as they offer readers valuable insights.

- Communication from Experts : experts can use the Op-Eds to highlight problems, propose solutions, present findings to the public and other experts. In this case, such essays possess in-depth expertise, robust scholarly rigor, and original arguments. Such essays are written by economists, doctors, lawyers, plumbers, researchers, teachers, librarians, playwrights, producers, psychologists, and any experts in a given field.

- First-Person Accounts : these are written by the public or anybody concerning daily experiences in their own words to compel the readers to see the world or at least reflect on their personal experiences from a different angle or perspective.

In class, you can be asked to write from either perspective. The goal is to test whether you have mastered writing skills that can place you better in the writing world.

As long as you challenge and engage the audience, you will consistently score the best grade. There are guidelines given in the Op-Ed essay prompts concerning the formatting styles.

Most Op-Eds that our essay writers have helped students like yourself write are in APA or MLA formats . Well, there are always a few required in Chicago/Turabian, Oxford, and Harvard formats.

Thus far, we hope that this guide has been elaborative, practical, and nothing short of a whole lecture on writing an Op-Ed and scoring the best grade for it. You need to have the lion or bear type of confidence when attacking your opinion article. Consult your rubric and prompt for formatting style and general approach.

As a student or professional, you may have too much workload or too little time in your hands. Well, if that is the case with you, rather than procrastinating, you can hire someone to help you write an Op-Ed from our essay website.

We work with professionals who understand how to plan, draft, and write better papers, whether with academic or professional tones. So do not let that deadline pass because you can use our urgent essay service to beat approaching deadlines. When you buy an essay from us, we write it from scratch within the deadline.

Paying for an essay on our website means you commit that a professional writer with the right experience and qualifications handles your piece of writing task. We are accomplished, decorated, and always ready to help anybody who is stuck : at a relatively affordable fee. Talk to us!

Gradecrest is a professional writing service that provides original model papers. We offer personalized services along with research materials for assistance purposes only. All the materials from our website should be used with proper references. See our Terms of Use Page for proper details.

What Is an Op-Ed Article? Op-Ed Examples, Guidelines, and More

Have you ever wondered the name of those articles in newspapers or online that seem to be more conversational in style than standard news stories?

These are called op-ed articles, and they are an entirely different style and format of writing that is typically found in the opinion section of a newspaper, magazine, or website.

In this article, I’m going to answer the question what is an op-ed article by digging into exactly what an op-ed article is as well as looking at some op-ed examples, how to write an op-ed, and how (and where) to submit an op-ed.

What Is an Op-Ed Article?

Op-ed stands for “opposite the editorial page,” and an op-ed article is an article in which the author states their opinion about a given topic, often with a view to persuade the reader toward their way of thinking.

Despite the “op” in “op-ed” not standing for “opinion,” op-eds are often called opinion pieces because, unlike standard news articles, the authors of op-eds are encouraged to give their opinions on a certain topic, as opposed to simply reporting the news.

Op-eds are sometimes written by a ghostwriter, which means somebody writes the op-ed on behalf of someone else (such as a businessperson or politician), then the intended author makes some tweaks, with the final version being attributed—bylined—to the intended author instead of the ghostwriter.

Anonymous Op-Eds

Op-eds can also be anonymous, although for larger publications, such as the New York Times , Wall Street Journal , and Washington Post , an anonymous op-ed is typically only allowed when the writer’s job (or in extreme cases, their life) would be jeopardized if their name or other distinguishing details were disclosed. In cases when an anonymous op-ed is allowed to go ahead, the author’s true identity is known by the publisher.

Whether or not anonymous op-eds should be allowed to be published comes up for frequent scrutiny, the most recent episode of which being in September 2018 after the New York Times published an anonymous opinion piece by a senior official working in the Trump administration. (In October 2020, former chief of staff in the Department of Homeland Security, Miles Taylor, publicly confirmed that he had authored the article.)

Op-Ed Responses

Often, op-ed articles are written in response to something that is happening in the news at a particular time; such as during a climate change summit or election cycle, or they are written as a response to another op-ed, whether the first opinion piece was published in the same newspaper or, for example, somebody decided to write an op-ed in the New York Times in response to an op-ed that appeared in the Wall Street Journal .

While there is no generalized word limit for an op-ed, most published op-eds run under 1,000 words. The New York Times notes that:

Written essays typically run from 800 to 1,200 words, although we sometimes publish essays that are shorter or longer.

Op-Ed Examples

For an article to be an op-ed it must, as noted above, appear in an opinion column. As many people find themselves reading op-eds after clicking a link online, op-ed columns typically also have the words ‘Opinion’ or ‘Guest Essay’ displayed above or close to the column’s headline.

If you’re looking for op-ed examples, look no further than the opinion pages of three of the largest newspapers in the United States, namely the New York Times , Wall Street Journal , and Washington Post opinion pages (for a longer list, see the How (and Where) to Submit an Op-Ed section below).

The Difference Between Op-Eds and Regular Articles

Some columns that look like a good op-ed article example are in fact lifestyle articles that, while not being timely in relation to the news of the day, aren’t defined as op-ed articles because they are purely factual, with no opinion being given.

Articles I have personally written for the New York Times , New York Observer , Quwartz , and similar publications had to be meticulously sourced and fact-checked before publication; and my opinion surrounding any of the topics in question was not taken into consideration, unlike for an op-ed.

That’s not to say you can simply make up facts when writing an op-ed. You can’t have your own opinion about the year Queen Elizabeth II was born (1926), the height of the Empire State Building (1,454 ft.), or the length of the Great Wall of China (21,196 km). Depending on what your op-ed is discussing, you can sprinkle your opinion in around facts, but those facts must be deep-rooted in order for your audience to get on board with your argument—and for a reputable source to choose to print your article.

How to Write an Op-Ed

Of course, knowing what an op-ed is and knowing how to write an op-ed are two different things entirely.

Here are my top five tips on how to write an op-ed:

- Get to the point: The moment a reader (or your potential editor) starts reading your op-ed article they need to know what it is about, and why it matters to them.

- Have a clear thesis: Submitting a meandering opinion column is a surefire way to ensure you do not hear back from the editor. Outline your entire op-ed before sitting down to write, and keep a clear thesis in mind.

- Write what you know: While many factors go into the op-ed selection process, having authority in the topic you’re writing about, as well as a persuasive argument, is required above all else.

- Write for the publication you’re pitching: Don’t use technical phrases if it is a non-technical publication. Look into what they have published on your topic in the past. How can you advance this discussion?

- Stick to the rules: Most op-ed sections list their rules for publication. These often include information on how to source your facts, a well as the house style.

How (and Where) to Submit an Op-Ed

It’s easy to submit an op-ed to either a national or local newspaper, or to a trade publication in your field. Assuming you’ve read my advice on how to write an op-ed above, here are the links you’ll need to submit an op-ed to the following newspapers:

- New York Times

- Wall Street Journal

- Washington Post

- Los Angeles Times

- Houston Chronicle

- Chicago Tribune

- San Francisco Chronicle

- Tampa Bay Times

- Dallas Morning News

- Denver Post

- Seattle Times

If you want to submit an op-ed to your local newspaper or a trade publication, look in their opinion columns for information on how to send in your submission, or search for their name alongside the word “submissions” online.

I hope this article on what an op-ed article is will help you on your journey toward writing and submitting your first op-ed to a major newspaper or publication.

If you’re interested in hearing more from me, be sure to subscribe to my free email newsletter , and if you enjoyed this article, please share it on social media, link to it from your website, or bookmark it so you can come back to it often. ∎

Benjamin Spall

You might also like....

Introducing Acne Club

Nature-Deficit Disorder: What It Is, and How to Overcome It

How to Feel Less Anxious About the Coronavirus (COVID-19)

How We Redesigned the New York Times Opinion Essay

When a team of editors, designers and strategists teamed up to talk about how times opinion coverage is presented and packaged to readers, they thought of a dinner party..

The NYT Open Team

By Dalit Shalom

Picture a dinner party. The table is set with a festive meal, glasses full of your favorite drink. A group of your friends gather around to talk and share stories. The conversation swings from topic to topic and everyone is engaged in a lively discussion, excited to share ideas and stories with one another.

This is what we imagined when we — a group of New York Times editors, strategists and designers — teamed up last summer to talk about how to think about how our Opinion coverage is presented and packaged to our readers. We envisioned a forum that facilitated thoughtful discussion and would invite people to participate in vibrant debates.

The team was established after a wave of feedback from our readers showed that many people found it difficult to tell whether a story was an Opinion piece or hard news. This feedback was concerning. The Times publishes fact-based journalism both in our newsroom and on our Opinion desk, but it is very important to our mission that the distinction between the two is clear.

The type of Opinion journalism our group was tasked with rethinking was the Op-Ed, which was first introduced in the Times newspaper in 1970. The Op-Ed was short for “opposite the Editorial Page,” and it contained essays written by both Times columnists and external contributors from across the political, cultural and global spectrum who shared their viewpoints on numerous topics and current events. Because of the Op-Ed’s proximity to the Editorial Page in the printed newspaper, it was clear that published essays were Opinion journalism.

Then The Times began publishing online. Today, most of our readers find our journalism across many different media channels. The Op-Ed lost its clear proximity to the Editorial Page, and the term has been used broadly as a catch-all phrase for Opinion pieces, leaving the definition of what an Op-Ed is unclear.

To learn more about the friction our readership was describing, we held several research sessions with various types of Times readers, including subscribers and non-subscribers. Over the course of these sessions, we learned that readers genuinely crave a diversity of viewpoints. They turn to the Opinion section for a curated conversation that introduces them to ideologies different than their own.

In the divided nature of politics today, many readers are looking for structured arguments that prepare them to converse thoughtfully about complicated topics. Some readers said they want to challenge and interrogate their own beliefs. Others worry that they exist in their own bubbles and they need to understand how the “other side” thinks.

And across the board, readers said they are aware that social media platforms can be echo chambers that help validate their beliefs rather than illuminate different perspectives. They believe The Times can help them look outside those echo chambers.

Considering this feedback, we took a close look at the anatomy of an Op-Ed piece. At a glance, Opinion pieces shared similar, but not necessarily cohesive, properties. They had an “Opinion” label at the top of the page that was sometimes followed by a descriptive sub-label (for example, “The Argument”), as a way to indicate a story belonged to a column. That would be a headline, a summary and a byline, often accompanied by an image or video before the actual text of the story.

By looking at those visual cues, it became clear to us that they could be reconfigured to better communicate the difference between news and opinion.

We created several design provocations and conducted user testing sessions with readers to see how this approach and a new layout might resonate. Some noticeable changes we made include center-aligning the Opinion label and header, labeling the section in red and providing more intentional guidance and art direction for visuals that accommodate Opinion pieces.

While many readers could tell the difference between news and opinion stories, they didn’t understand why certain voices were featured in the Opinion section. They wanted more clarity about the Op-Ed, such as who wrote it and whether the writer was Times staff or an external voice. In the case of external contributors, readers wanted to know why the desk chose to feature their voice.

These questions took our team back to the drawing board. We began to realize that the challenge at hand was not solely a design problem, but a framing issue, as well.

We had long philosophical conversations about the meaning of Op-Ed pieces. We talked about the importance of hosting external voices and how those voices should be presented to our readers. The metaphor of a dinner party figured prominently in our conversations: the Opinion section should be a place where guests gather to engage in an environment that is civil and respectful.

We began to sharpen how we might convey the difference between an endorsement of a particular voice and hosting a guest — one of many who might contribute to a lively debate around a current event.

The more we thought about the Opinion section as a dinner party, the more we felt how crucial it was to communicate this idea to readers.

As we approached the designs, we set out to create an atmosphere for open dialogue and conversation. Two significant editorial changes came out of our group conversations.

After many iterations, we decided to introduce a two-tiered labeling system, so that readers could understand unequivocally the type of Opinion piece they were about to engage with. For external voices, we added the label “ Guest Essay ,” alongside other labels that indicate staff contributors and internal editorials. The label “Guest Essay” not only shifts the tone of a piece — a guest that we are hosting to share their point of view — but it also helps readers distinguish between opinions coming from the voice of The Times and opinions coming from external voices.

The second important editorial change is a more detailed bio about the author whose opinion we are sharing. With the dinner party metaphor in mind, this kind of intentional introduction can be seen as a toast, providing context, clarity and relevance around who someone is and why we chose them to write an essay.

Some of these changes may seem subtle, but sometimes the best dinner conversations are nuanced. This body of work signals an important moment for The New York Times in how we think about expressing opinions on our platform. We believe that one of the things that makes for a healthy society and a functioning democracy is a space for numerous perspectives to be honored and celebrated. We are confident these improvements will help further Times Opinion’s mission of curating debate and discussion around the world’s most pressing issues.

Dalit Shalom is the Design Lead for the Story Formats team at The New York Times, focusing on crafting new storytelling vehicles for Times journalism. Dalit teaches classes on creative thinking and news products at NYU and Columbia, and in her free time you can find her baking tremendous amounts of babka.

Written by The NYT Open Team

We’re New York Times employees writing about workplace culture, and how we design and build digital products for journalism.

More from The NYT Open Team and NYT Open

How to Dox Yourself on the Internet

A step-by-step guide to finding and removing your personal information from the internet..

CJ Robinson

How the New York Times Games Data Team Revamped Its Reporting

Huge amounts of data from wordle and connections changed the way our team approached data infrastructure and design.

Rethinking How We Evaluate The New York Times Subscription Performance

An exploration into the growth data team’s process of designing and building a new subscription reporting model..

Estimation Isn’t for Everyone

The evolution of agility in software development, recommended from medium.

Bringing Dark Mode to our News Apps

How teams across the new york times launched the dark mode feature to our news apps..

Matej Latin

UX Collective

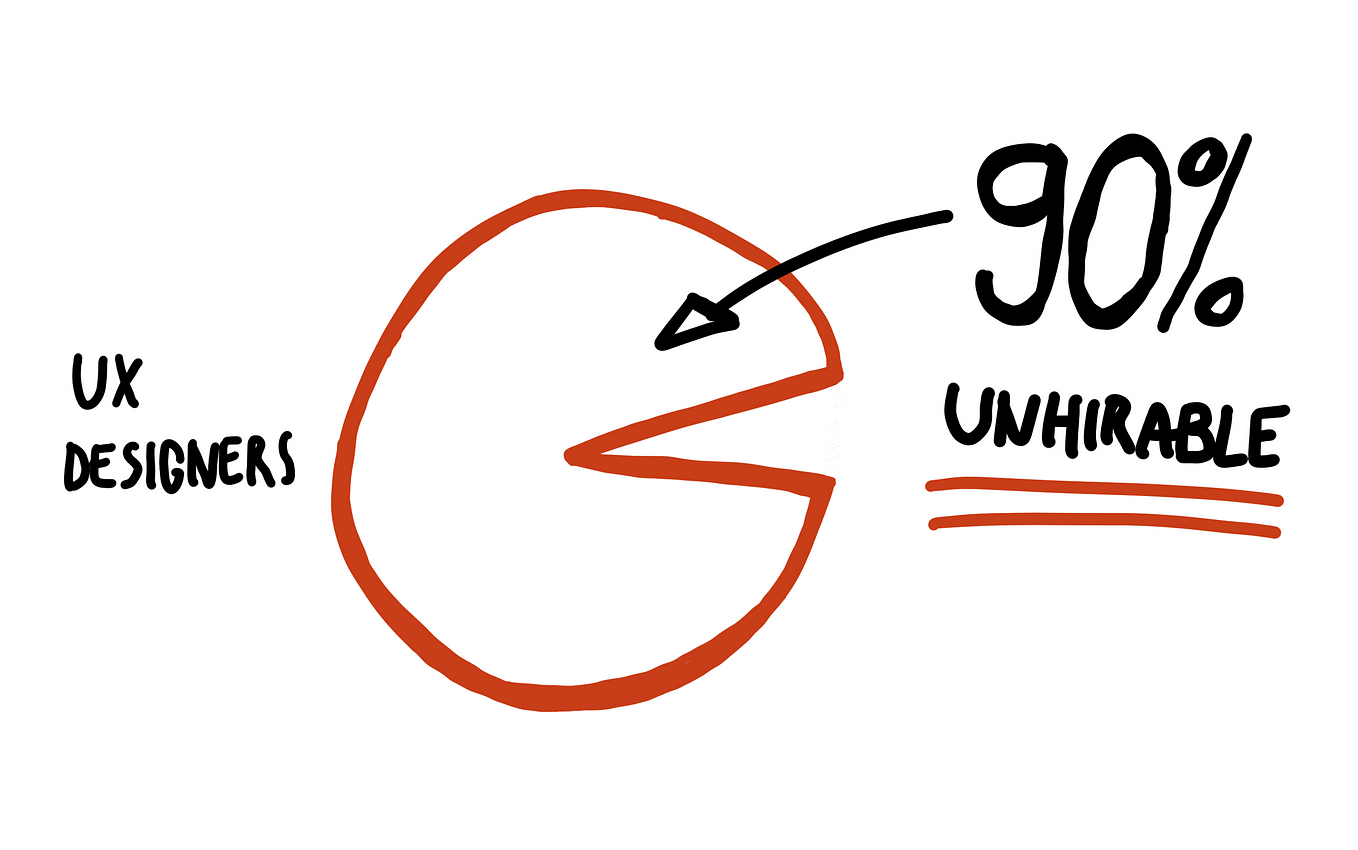

90% of designers are unhirable?

Or why your cookie-cutter portfolio doesn’t cut it and how to fix it.

Stories to Help You Grow as a Designer

Interesting Design Topics

Icon Design

Ameer Omidvar

Apple’s all new design language

My name is ameer, currently the designer of sigma. i’ve been in love with design since i was a kid. it was just my thing. to make things….

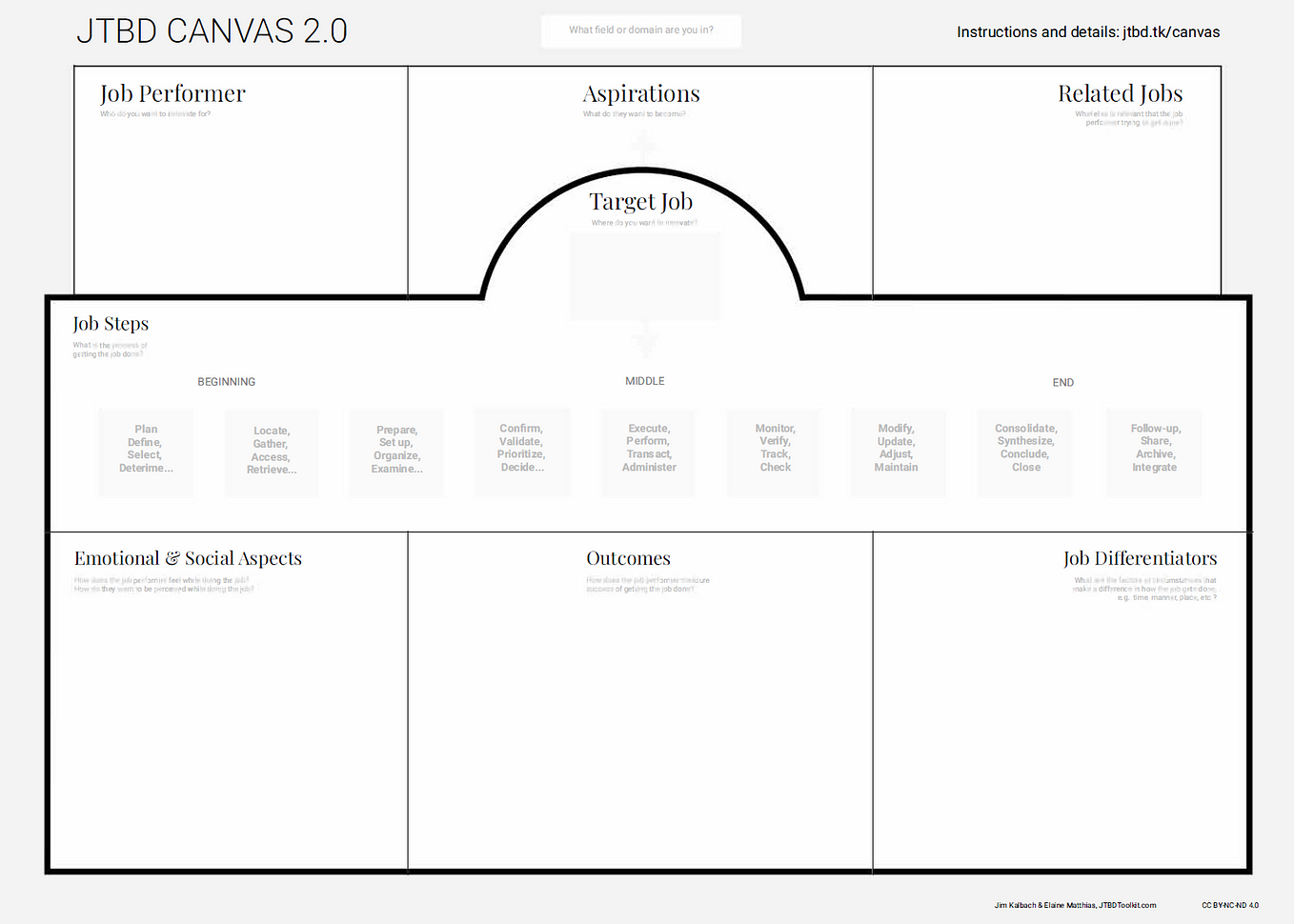

JTBD Toolkit

Accelerating JTBD Research with AI

By jim kalbach (feb 2024).

Fredrick Royster

A UX Design “Influencer” Tried To Get Me Fired From Teaching

It is illegal to try to get someone fired using false claims.

Punit Chawla

How Airbnb Became a Leader in UX Design

From a small bed & breakfast to a leader in ux/ui design, this billion dollar startup is a leader in innovation and design thinking.

Text to speech

Writing Studio

How to write an op-ed.

These tips are based on an “ On Writing ” panel hosted by the Writing Studio and the Russell G. Hamilton Graduate Leadership Institute on November 20, 2019 that included Professor of Communications Bonnie Dow, Assistant Vice Chancellor of Strategic Communications Ian Morrison, Professor of History Moses Ochonu, and Associate Professor of Earth and Environmental Science Jonathan Gilligan.

Why Write an Op-Ed in Graduate School?

As our panelists pointed out, writing op-eds can be a useful exercise, even an important piece of academic training.

It can be a way for you to take your research, your expertise, and communicate to the public and make an engagement with people who aren’t in the academic world, regardless of where the op-ed is placed.

Writing an op-ed, in other words, is a way of practicing, or putting your effort into saying, “My work matters.”

Know Your Audience

“Really take the time to think about, where am I trying to place this? Who are their readers? How do they want to hear this? What is going to grab their attention?” – Ian Morrison

As an op-ed writer your audience is twofold: you need to think about both the publisher’s attention—for which you will be competing with thousands of other submissions—as well as the reader’s. For this reason, an attention-grabbing first paragraph, if not first sentence, is paramount.

It also helps to think about the role of opinion pages: as a forum for opinion, they create conversations that live beyond the pages of the publication in which they originally appear. In other words, op-eds seek to amplify the discussion.

Really take the time to think about where you are trying to place the op-ed, who the readers are, what and how do they want to hear this, and what is going to grab their attention. At the same time, aim to be interesting and relevant. You need to address issues in the public conversation.

Organization and Style

“Examples and anecdotes engage readers. Opening with an example, an anecdote, or with a startling statistic works really well at the top of an op-ed.” – Bonnie Dow

Short paragraphs—two to three sentences, maybe four—are a must. If you submit traditional academic paragraphs, you risk having them shortened by the publisher in ways you don’t like. You might end up with something that doesn’t make sense to you. So keep your paragraphs short.

Use structure to build to your point. In other words, make the paragraphs do the work of transitions and previews for you. Instead of saying “first,” “second,” or “third” in op-eds, start a new paragraph when you want to say something.

Use short, punchy, declarative sentences. This will help you stick to the word limit and avoid a situation in which the publisher chops up the piece for you. You absolutely want to maintain control of your own message. Be wary of semicolons or colons; if you need the latter, your sentences are probably too long. Use active rather than passive writing.

Content and Accuracy

“If you’re looking for places to have an impact, look at all the media that you can engage with. The op-ed is one specific thing, and it is one specific writing style, and one specific medium.” –Jonathan Gilligan

Think about your goals and your narrative. Ask yourself, does it fit with other op-eds I’ve read? Can I accomplish my goals using this structure of writing? Remember: don’t under-qualify things. Factual accuracy is incredibly important. If you write an op-ed and you oversimplify, your words are out there permanently.

Avoid giving the wrong impression of too much certainty that comes from blunting nuance or veering close to misrepresentation (even if there is wiggle-room for justification). That’s part of the struggle: strive for simplicity, be punchy, but make sure that you are willing to stand behind exactly what you said the way you said it with your reputation as a scholar.

And remember: Always proofread, proofread, proofread!

My Timetable

LOG IN to show content

My Quick Links

Op-Ed Writing

Op-ed articles were originally named because they appeared opposite the editorial page in a newspaper. Like a persuasive essay, an op-ed article attempts to convince the reader of a particular perspective. Although op-ed articles are often written by newspaper and magazine columnists, academics are increasingly writing op-eds to share their general research with a broader audience.

Op-eds range in length but are often between 600-800 words.

Taking a Position

As an argumentative piece of writing, an op-ed takes a clear position on an issue (i.e., it contains a thesis).

Since op-eds are intended for a broader readership, the thesis often includes both a theoretical position and a practical position. The theoretical position makes a contestable claim about a particular issue. The practical position, meanwhile, provides a policy recommendation or a solution to a real-world problem.

The following theoretical and practical positions are taken from the op-ed, " Getting active is the closest thing we have to a ‘magic pill’ for good health ":

Theoretical position

Getting active is the closest thing we have to a “magic pill.” Even just a little bit of exercise per day can provide broad benefits to our physical and mental health, and in many settings can also enhance our sense of belonging and inclusion. That’s why regular physical activity is so much more than a nice-to-have hobby for those who can afford it – it is a necessity of life.

Practical position

A new comprehensive and well resourced physical-activity strategy is urgently needed. We need to rediscover the value of school-based physical education programs, the importance of enlightened urban-planning policies, the significance of active transportation plans, and to apply the lessons learned in other jurisdictions. Our new federal Minister of Health, Jean-Yves Duclos, could convene a physical-activity summit to kickstart the development of such a strategy.

Argumentation and Evidence

Much like a persuasive academic essay, the op-ed writer needs to support their thesis by making an evidence-based argument. This can include discussing sources, such as reports, and including evidence. However, op-eds do not include citations (unless specified by your assignment guidelines). Instead, you can hyperlink sources within the text.

Unlike a persuasive academic essay, the op-ed writer can use other argumentative tools to make an emotional connection with the reader. This can include discussing a personal experience or anecdote or using inclusive language such as “we” and “us.”

Structuring an Op-Ed

The first few sentences are critical to an effective op-ed. Readers of op-eds will not be as patient as academic readers. You need to capture their interest right away. Here are some ways to develop an effective hook:

- Connect your topic to an event in the news.

- Ask an interesting question or make a provocative statement.

- Draw upon a personal experience.

Unlike a persuasive academic essay, an op-ed thesis (both the theoretical and practical position) is usually found towards the middle or end of the article. This convention helps build intrigue as the author leads the reader to their position.

A Variation on Counterarguments

It is standard practice in a persuasive essay to consider and respond to counterarguments. Op-ed writers often adapt this traditional counterargument structure by:

- Posing a question/debate.

- Discussing a possible position and then refuting that position.

- Presenting their thesis.