Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Writers — William Shakespeare

Essays on William Shakespeare

What makes a good william shakespeare essay topic.

When it comes to crafting an exceptional essay on the works of William Shakespeare, the choice of topic is paramount. The right topic can breathe life into your essay, making it captivating, unique, and unforgettable. Here are some innovative tips to help you brainstorm and select an essay topic that will mesmerize your readers:

- Research and Immerse Yourself: Begin by immersing yourself in the vast repertoire of William Shakespeare's works. Dive into his plays, poems, and sonnets. This deep exploration will provide you with invaluable insights into his themes, characters, and writing style.

- Personal Passion: Opt for a topic that ignites a genuine spark of interest within you. When you are truly passionate about the subject matter, it will shine through in your writing, captivating your readers and making your essay more compelling.

- Unveiling the Unexplored: Seek out uncharted territory and lesser-known aspects of Shakespeare's works. Instead of treading the well-worn path of common themes or characters, venture into the hidden gems that lie within his literature.

- Contemporary Connections: Explore the relevance of Shakespeare's works in today's society and connect them to modern-day issues. Examining the timeless themes and their impact on the present can render your essay thought-provoking and engaging.

- Characters and Relationships Under the Microscope: Shakespeare's characters are multifaceted and intricate. Choose a topic that allows you to analyze their motivations, relationships, or character development within his plays.

- Comparative Analysis: Engage in a comparative exploration of Shakespeare's works alongside other literary pieces, historical events, or even contemporary movies or plays. This fresh perspective will make your essay stand out from the crowd.

- Social and Cultural Context: Delve into the social and cultural milieu that shaped Shakespeare's plays. Discuss how his works were influenced by the Elizabethan era and how they mirror the society of that time.

- Unveiling Symbolism and Imagery: Shakespeare's works are a treasure trove of symbolism and vivid imagery. Select a topic that allows you to analyze and interpret these literary devices, offering profound insights into the text.

- Controversial Contemplations: Shakespeare fearlessly explored contentious themes such as power, love, and morality. Choose a topic that tackles these provocative issues, sparking a lively debate among your readers.

- Unconventional Interpretations: Present a fresh and unconventional interpretation of a particular play, scene, or character. Challenge conventional ideas and encourage critical thinking with your unique perspective.

Remember, a remarkable Shakespeare essay topic should be captivating, original, and thought-provoking. By considering these recommendations, you will be able to select a topic that will enrapture your readers and showcase your exceptional analytical skills.

Essay Topic Ideas for William Shakespeare

Prepare to be dazzled by these outstanding essay topics on William Shakespeare:

- The Empowerment of Women in Shakespeare's Tragedies

- Fate and Its Grip on Romeo and Juliet

- The Fine Line Between Madness and Sanity in Hamlet

- Love's Intricacies and Deception in Much Ado About Nothing

- Unraveling the Allure of Power and Ambition in Macbeth

- Exploring the Dark Depths of Evil in Othello

- Shakespeare's Brave Confrontation of Racism in The Merchant of Venice

- The Mighty Influence of Language and Wordplay in A Midsummer Night's Dream

- Revenge and Justice Collide in Titus Andronicus

- The Greek Mythology Odyssey within Shakespeare's Plays

- The Symbolic Tapestry of Nature in King Lear

- Gender Roles and Identity in Twelfth Night

- Time's Elusive Spell in The Tempest

- The Supernatural's Sinister Dance in Macbeth

- The Illusion of Appearance versus the Reality of Truth in Measure for Measure

- The Complexities of Love's Dominion in Antony and Cleopatra

- The Intricate Weaving of Politics in Julius Caesar

- Jealousy's Venomous Touch in Othello

- The Struggle between Duty and Desire in Hamlet

- A Profound Exploration of Human Nature in Troilus and Cressida

Provocative Questions for Your William Shakespeare Essay

Prepare to embark on an intellectual journey with these thought-provoking essay questions on William Shakespeare:

- How does Shakespeare challenge traditional gender roles in his plays?

- What is the significance of the supernatural elements in Macbeth?

- How does Shakespeare explore the theme of power and its corrupting influence in his tragedies?

- Analyze the portrayal of love and relationships in Shakespeare's comedies.

- To what extent does fate play a role in Romeo and Juliet, and are the characters responsible for their own destinies?

- Discuss the concept of madness and its impact on the characters in Hamlet.

- How does Shakespeare employ symbolism and imagery to convey his themes in The Tempest?

- Analyze the role of loyalty and betrayal in Julius Caesar.

- How does Othello's race affect the outcome of the play?

- Discuss the portrayal of revenge in Shakespeare's plays.

Creative William Shakespeare Essay Prompts

Ignite your creativity with these captivating essay prompts on William Shakespeare:

- Imagine you are a director staging a modern adaptation of one of Shakespeare's plays. How would you interpret the setting, costumes, and overall production to make it relevant to a contemporary audience?

- Write a heartfelt letter from one of Shakespeare's characters to another, expressing their deepest desires, fears, or regrets.

- Create a powerful monologue from the perspective of a minor character in any of Shakespeare's plays, unveiling their untold story or hidden emotions.

- Write a riveting dialogue between Shakespeare and a modern-day playwright, discussing the enduring appeal and relevance of his works.

- Imagine you are a literary critic tasked with analyzing a previously undiscovered Shakespearean sonnet. Interpret its meaning and discuss its significance within the context of his other works.

William Shakespeare Essay FAQ

Q: How should I begin my essay on William Shakespeare?

A: Commence with a captivating introduction that sets the stage for your essay and introduces your thesis statement. You can start with a compelling quote, an intriguing fact, or a thought-provoking question.

Q: Can I choose a lesser-known play by Shakespeare as my essay topic?

A: Absolutely! Exploring lesser-known plays can provide a fresh perspective, allowing you to delve into unexplored themes and characters. Just ensure that you provide enough context and background information for your readers.

Q: Should I include direct quotes from Shakespeare's works in my essay?

A: Including quotes can enhance your analysis and provide evidence to support your arguments. However, make sure to seamlessly integrate and analyze the quotes, rather than using them as mere filler.

Q: Can I incorporate modern examples or references in my essay on Shakespeare?

A: Yes, incorporating modern examples or references can help readers connect with the themes and relevance of Shakespeare's works. Just ensure that the examples are relevant and enhance your analysis, rather than overshadowing it.

Q: How can I make my Shakespeare essay stand out from others?

A: To make your essay shine, choose a unique and thought-provoking topic, offer fresh interpretations, and employ engaging language and writing style. Support your arguments with evidence and provide a well-structured analysis.

Remember, writing a Shakespeare essay is an opportunity to showcase your critical thinking and analytical skills. Embark on a thrilling journey through the world of Shakespeare and let your creativity illuminate your writing!

Diction in Macbeth

Iago’s motive in william shakespeare’s othello, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Double Toil and Trouble in Macbeth

"romeo and juliet" by william shakespeare: fate and destiny, the biography of william shakespeare - plays & wife, analysis of the role of women in shakespeare's plays, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

"As You Like It" and "A Midsummer Night"s Dream": Feminine Homoeroticism

Analysis of the theme of love and deceit in twelfth nigh, love and gender roles in romeo and juliet, how william shakespeare is still relevant today, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

Racial Discrimination and Sexism in William Shakespeare's Plays

Analysis of the use of literary devices in sonnet 18 by william shakespeare, analysis of the influence of english renaissance on william shakespeare, william shakespeare and his contribution to the renaissance, the role of fate in "romeo & juliet" by william shakespeare, the power of love in william shakespeare’s play the tempest, nature of man by william shakespeare's othello, william shakespeare and the importance of his literary works, why william shakespeare’s plays are no longer relevant, analysis of macbeth by william shakespeare, family theme in william shakespeare's works, catharsis in william shakespeare’s king lear, an analysis of william shakespeare’s othello, research on much ado about nothing, shakespeare is a creator of drama, analysis of the important aspects and measures covered in the shakespeare’s play "taming of the shrew", analysis of self-deluded characters in the tragedy of julius caesar, the role of the three witches in shakespearean play macbeth, love as a source of life shakespeare's sonnet 29, the structural and symbolic elements of mythology in many of shakespeare's plays.

April 1564, Stratford-upon-Avon, United Kingdom - April 23, 1616, Stratford-upon-Avon, United Kingdom

Playwright, Poet, Actor

English Renaissance

Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, Macbeth, Othello, A Midsummer Night's Dream, Julius Caesar, The Tempest, Much Ado About Nothing,Twelfth Night, Macbeth, etc.

William Shakespeare, widely regarded as one of the greatest playwrights in history, possessed a unique and influential style of writing. His works demonstrate a mastery of language, poetic devices, and dramatic techniques that continue to captivate audiences centuries later. Shakespeare's writing style can be characterized by several distinctive features. Firstly, his use of language is rich and vibrant. He employed a vast vocabulary and crafted elaborate sentences, often employing complex wordplay and puns to create layers of meaning. Shakespeare's writing is renowned for its poetic beauty, rhythmic verse, and memorable lines that have become ingrained in the English language. Secondly, Shakespeare excelled in character development. His characters are multidimensional, with complex emotions and motivations. Through their soliloquies and dialogues, he explores the depths of human nature, delving into themes of love, jealousy, ambition, and morality. Each character's speech and mannerisms reflect their unique personality, contributing to the depth and realism of his plays. Lastly, Shakespeare's dramatic structure and storytelling techniques are unparalleled. He skillfully weaves together intricate plots, incorporating elements of comedy, tragedy, romance, and history. His plays feature dramatic tension, unexpected twists, and powerful climaxes that keep audiences engaged and emotionally invested.

One of Shakespeare's major contributions was his ability to delve into the depths of human emotions and the complexities of the human condition. Through his plays, he explored themes such as love, jealousy, ambition, revenge, and moral dilemmas, offering profound insights into the human psyche. His characters, like Hamlet, Macbeth, Juliet, and Othello, are iconic and have become archetypes in literature. Shakespeare's language and wordplay revolutionized English literature. He introduced new words, phrases, and expressions that have become an integral part of the English lexicon. His plays are a testament to his mastery of language, employing poetic techniques such as metaphors, similes, alliteration, and iambic pentameter to create rhythm, beauty, and depth in his writing. Moreover, Shakespeare's plays transcended the boundaries of time and place, showcasing universal themes and resonating with audiences across cultures and generations. His works continue to be performed and adapted in various forms, including stage productions, films, and literary adaptations, further solidifying his contribution to the world of literature.

Film Adaptations: Many of Shakespeare's plays have been adapted into films, bringing his stories to life on the silver screen. Notable examples include Franco Zeffirelli's "Romeo and Juliet" (1968), Kenneth Branagh's "Henry V" (1989), and Baz Luhrmann's modernized version of "Romeo + Juliet" (1996). TV Series and Episodes: Shakespeare's works have been featured in TV series and episodes, either through direct adaptations or by incorporating his themes and characters. For instance, the popular TV show "The Simpsons" has parodied Shakespeare in episodes like "A Midsummer's Nice Dream" and "Tales from the Public Domain." Shakespearean-Inspired Films: Some films draw inspiration from Shakespeare's works without being direct adaptations. Examples include "Shakespeare in Love" (1998), which explores the fictionalized romance between Shakespeare and a noblewoman, and "10 Things I Hate About You" (1999), a modern-day adaptation of "The Taming of the Shrew." Literary References: Shakespeare is often referenced in literature, showcasing his enduring influence. For instance, Aldous Huxley's dystopian novel "Brave New World" features characters who quote Shakespeare, and Margaret Atwood's "The Handmaid's Tale" includes a clandestine resistance group called "Mayday," derived from "May Day" in Shakespeare's "The Tempest."

1. Shakespeare is known for writing 39 plays, including tragedies like "Hamlet," comedies like "A Midsummer Night's Dream," and histories like "Henry V." 2. Shakespeare is credited with introducing over 1,700 words to the English language, including popular terms such as "eyeball," "fashionable," and "lonely." 3. Shakespeare's works have been translated into more than 80 languages, making him one of the most widely translated playwrights in history. 4. Shakespeare's plays continue to be performed and studied worldwide, with an estimated 17,000 performances of his works every year. 5. Despite his literary fame, little is known about Shakespeare's personal life. There are gaps and uncertainties surrounding his birthdate, education, and even the authorship of his works. 6. The Globe Theatre: Shakespeare's plays were performed at the famous Globe Theatre in London, which he co-owned. The reconstructed Globe Theatre stands in London today and offers modern audiences a glimpse into the world of Elizabethan theatre. 7. In addition to his plays, Shakespeare wrote 154 sonnets, which are celebrated for their lyrical beauty and exploration of themes such as love, time, and mortality.

William Shakespeare is an essential topic for essay writing due to his immense significance in the world of literature and his enduring influence on various aspects of human culture. Exploring Shakespeare's works provides a rich opportunity to delve into themes of love, tragedy, power, and human nature. His plays and sonnets continue to captivate readers and audiences with their universal themes and timeless relevance. Studying Shakespeare allows us to gain a deeper understanding of the English language itself, as he contributed numerous words and phrases that are still in use today. Additionally, his innovative use of language, poetic techniques, and complex characterizations showcase his unparalleled mastery as a playwright. Furthermore, Shakespeare's impact extends beyond literature. His works have been adapted into numerous films, theater productions, and other art forms, making him a cultural icon. His plays also provide a valuable lens through which to analyze historical and social contexts, as they reflect the values, beliefs, and conflicts of the Elizabethan era.

"All that glitters is not gold." "By the pricking of my thumbs, Something wicked this way comes. Open, locks, Whoever knocks!" In William Shakespeare's Hamlet, "to be, or not to be, that is the question." In the 21st century, "to code, or not to code, that is the challenge.

1. Shakespeare, W., Shakespeare, W., & Kaplan, M. L. (2002). The merchant of Venice (pp. 25-120). Palgrave Macmillan US. (https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-137-07784-4_2) 2. Shakespeare, W. (2019). The tempest. In One-Hour Shakespeare (pp. 137-194). Routledge. (https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780429262647-9/tempest-william-shakespeare) 3. Johnson, S. (2020). The Preface to The Plays of William Shakespeare (1765). In Samuel Johnson (pp. 423-462). Yale University Press. (https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.12987/9780300258004-040/html?lang=de) 4. Denvir, J. (1986). William Shakespeare and the Jurisprudence of Comedy. Stan. L. Rev., 39, 825. (https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/stflr39&div=38&id=&page=) 5. Demmen, J. (2020). Issues and challenges in compiling a corpus of early modern English plays for comparison with those of William Shakespeare. ICAME Journal, 44(1), 37-68. (https://sciendo.com/article/10.2478/icame-2020-0002) 6. Liu, X., Xu, A., Liu, Z., Guo, Y., & Akkiraju, R. (2019, May). Cognitive learning: How to become william shakespeare. In Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-6). (https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3290607.3312844) 7. Xu, W., Ritter, A., Dolan, W. B., Grishman, R., & Cherry, C. (2012, December). Paraphrasing for style. In Proceedings of COLING 2012 (pp. 2899-2914). (https://aclanthology.org/C12-1177.pdf) 8. Craig, H. (2012). George Chapman, John Davies of Hereford, William Shakespeare, and" A Lover's Complaint". Shakespeare Quarterly, 63(2), 147-174. (https://www.jstor.org/stable/41679745) 9. Zhao, Y., & Zobel, J. (2007, January). Searching with style: Authorship attribution in classic literature. In Proceedings of the thirtieth Australasian conference on Computer science-Volume 62 (pp. 59-68). (https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=3973ff27eb173412ce532c8684b950f4cd9b0dc8)

Relevant topics

- Frankenstein

- Catcher in The Rye

- Of Mice and Men

- Thank You Ma Am

- Marxist Criticism

- The Crucible

- The Alchemist

- The Things They Carried

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Bibliography

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Literary Theory and Criticism

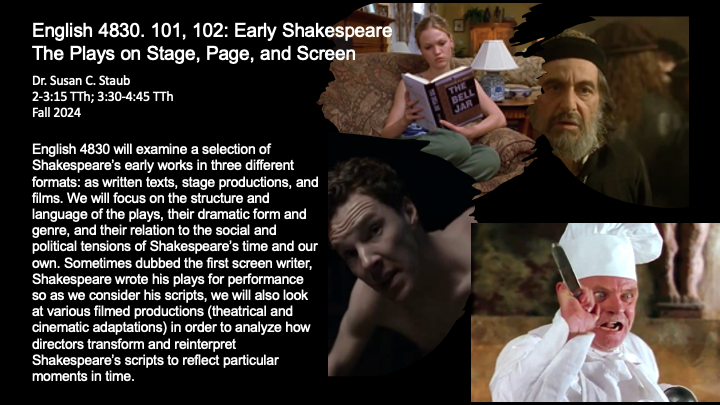

Home › Drama Criticism › Analysis of William Shakespeare’s Plays

Analysis of William Shakespeare’s Plays

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on May 19, 2019 • ( 5 )

Few dramatists can lay claim to the universal reputation achieved by William Shakespeare. His plays have been translated into many languages and performed on amateur and professional stages throughout the world. Radio, television, and film versions of the plays in English, German, Russian, French, and Japanese have been heard and seen by millions of people. The plays have been revived and reworked by many prominent producers and playwrights, and they have directly influenced the work of others. Novelists and dramatists such as Charles Dickens , Bertolt Brecht , William Faulkner , and Tom Stoppard , inspired by Shakespeare’s plots, characters, and poetry, have composed works that attempt to re-create the spirit and style of the originals and to interpret the plays in the light of their own ages. A large and flourishing Shakespeare industry exists in England, America, Japan, and Germany, giving evidence of the playwright’s popularity among scholars and the general public alike.

Evidence of the widespread and deep effect of Shakespeare’s plays on English and American culture can be found in the number of words and phrases from them that have become embedded in everyday usage: Expressions such as “star-crossed lovers” are used by speakers of English with no consciousness of their Shakespearean source. It is difficult to imagine what the landscape of the English language would be like without the mountain of neologisms and aphorisms contributed by the playwright.Writing at a time when English was quite pliable, Shakespeare’s linguistic facility and poetic sense transformed English into a richly metaphoric tongue.

Working as a popular playwright, Shakespeare was also instrumental in fusing the materials of native and classical drama in his work. Hamlet, Prince of Denmark , with its revenge theme, its ghost, and its bombastic set speeches, appears to be a tragedy based on the style of the Roman playwright Seneca, who lived in the first century c.e. Yet the hero’s struggle with his conscience and his deep concern over the disposition of his soul reveal the play’s roots in the native soil of English miracle and mystery dramas, which grew out of Christian rituals and depicted Christian legends. The product of this fusion is a tragedy that compels spectators and readers to examine their own deepest emotions as they ponder the effects of treacherous murder on individuals and the state. Except for Christopher Marlowe, the predecessor to whom Shakespeare owes a considerable debt, no other Elizabethan playwright was so successful in combining native and classical strains.

Shakespearean characters, many of whom are hybrids, are so vividly realized that they seem to have achieved a life independent of the worlds they inhabit. Hamlet stands as the symbol of a man who, in the words of the famous actor Sir Laurence Olivier, “could not make up his mind.” Hamlet’s name has become synonymous with excessive rationalizing and idealism. Othello’s jealousy, Lear’s madness, Macbeth’s ambition, Romeo and Juliet’s star-crossed love, Shylock’s flinty heart—all of these psychic states and the characters who represent them have become familiar landmarks in Western culture. Their lifelikeness can be attributed to Shakespeare’s talent for creating the illusion of reality in mannerisms and styles of speech. His use of the soliloquy is especially important in fashioning this illusion; the characters are made to seem fully rounded human beings in the representation of their inner as well as outer nature. Shakespeare’s keen ear for conversational rhythms and his ability to reproduce believable speech between figures of high and low social rank also contribute to the liveliness of action and characters.

In addition, Shakespeare excels in the art of grasping the essence of relationships between husbands and wives, lovers, parents and children, and friends. Innocence and youthful exuberance are aptly represented in the fatal love of Romeo and Juliet; the destructive spirit of mature and intensely emotional love is caught in the affair between Antony and Cleopatra. Other relationships reveal the psychic control of one person by another (of Macbeth by Lady Macbeth), the corrupt soul of a seducer (Angelo in Measure for Measure ), the twisted mind of a vengeful officer (Iago in Othello ), and the warm fellowship of simple men (Bottom and his followers in A Midsummer Night’s Dream ). The range of emotional states manifested in Shakespeare’s characters has never been equaled by succeeding dramatists.

These memorable characters have also been given memorable poetry to speak. In fact, one of the main strengths of Shakespearean drama is its synthesis of action and poetry. Although Shakespeare’s poetic style is marked by the bombast and hyperbole that characterize much of Elizabethan drama, it also has a richness and concreteness that make it memorable and quotable. One need think only of Hamlet’s “sea of troubles” or Macbeth’s daggers “unmannerly breech’d with gore” to substantiate the imagistic power of Shakespearean verse. Such images are also worked into compelling patterns in the major plays, giving them greater structural unity than the plots alone provide. Disease imagery in Hamlet, Prince of Denmark , repeated references to blood in Macbeth , and allusions to myths of children devouring parents in King Lear represent only a few of the many instances of what has been called “reiterated imagery” in Shakespearean drama.Wordplay, puns, songs, and a variety of verse forms, from blank verse to tetrameter couplets—these features, too, contribute to the “movable feast” of Shakespeare’s style.

In a more general sense, Shakespeare’s achievement can be traced to the skill with which he used his medium—the stage. He created certain characters to fit the abilities of certain actors, as the role of Falstaff in the Henry IV and Henry V plays so vividly demonstrates. He made use of every facet of the physical stage—the trapdoor, the second level, the inner stage, the “heavens”—to create special effects or illusions. He kept always before him the purpose of entertaining his audience, staying one step ahead of changes in taste among theatergoers. That both kings and tinkers were able to find in a Shakespearean play something to delight and instruct them is testimony to the wide appeal of the playwright. No doubt the universality of his themes and his deep understanding of human nature combined to make his plays so popular. These same strengths generate the magnetic power that brings large audiences into theaters to see the plays today.

Analysis of Shakespearean Plays

The two portraits of Shakespeare portray the two parts of his nature. On one hand, he possessed immense intellectual curiosity about the motives and actions of people. This curiosity, plus his facility with language, enabled him to write his masterpieces and to create characters who are better known than some important figures in world history. On the other hand, reflecting his middle-class background, Shakespeare was himself motivated by strictly bourgeois instincts; he was more concerned with acquiring property and cementing his social position in Stratford than he was with preserving his plays for posterity. If his partners had not published the First Folio, there would be no Shakespeare as he is known today: still acted and enjoyed, the most widely studied and translated writer, the greatest poet and dramatist in the English and perhaps any language.

Besides his ability to create a variety of unforgettable characters, there are at least two other qualities that account for Shakespeare’s achievement. One of these is his love of play with language, ranging from the lowest pun to some of the world’s best poetry. His love of language sometimes makes him difficult to read, particularly for young students, but frequently the meaning becomes clear in a well-acted version. The second quality is his openness, his lack of any restrictive point of view, ideology, or morality. Shakespeare was able to embrace, identify with, and depict an enormous range of human behavior, from the good to the bad to the indifferent. The capaciousness of his language and vision thus help account for the universality of his appeal.

Shakespeare’s lack of commitment to any didactic point of view has often been deplored. Yet he is not entirely uncommitted; rather, he is committed to what is human. Underlying his broad outlook is Renaissance Humanism, a synthesis of Christianity and classicism that is perhaps the best development of the Western mind and finds its best expression in his work. This same generous outlook was apparently expressed in Shakespeare’s personality, which, like his bourgeois instincts, defies the Romantic myth of the artist. He was often praised by his fellows, but friendly rival and ferocious satirist Ben Jonson said it best: “He was, indeed, honest, and of an open and free nature,” and “He was not of an age, but for all time.”

The History Plays

William Shakespeare began his career as a playwright by experimenting with plays in the three genres—comedy, history, and tragedy—that he would perfect as his career matured. The genre that dominated his attention throughout his early career, however, was history. Interest in the subject as proper stuff for drama was no doubt aroused by England’s startling victory over Spain’s vaunted navy, the Armada, in 1588. This victory fed the growing popular desire to see depictions of the critical intrigues and battles that had shaped England’s destiny as the foremost Protestant power in Europe.

This position of power had been buttressed by the shrewd and ambitious Elizabeth I, England’s “Virgin Queen,” who, in the popular view, was the flower of the Tudor line. Many critics believe that Shakespeare composed the histories to trace the course of destiny that had led to the emergence of the Tudors as England’s greatest kings and queens. The strength of character and patriotic spirit exhibited by Elizabeth seem to be foreshadowed by the personality of Henry V, the Lancastrian monarch who was instrumental in building an English empire in France. Because the Tudors traced their line back to the Lancastrians, it was an easy step for Shakespeare to flatter his monarch and please his audiences with nationalistic spectacles that reinforced the belief that England was a promised land.

Whatever his reasons for composing the history plays, Shakespeare certainly must be seen as an innovator of the form, for which there was no model in classical or medieval drama. Undoubtedly, he learned much from his immediate predecessors, however— most notably from Christopher Marlowe, whose Edward II (pr. c. 1592) treated the subject of a weak king nearly destroying the kingdom through his selfish and indulgent behavior. From Marlowe, Shakespeare also inherited the idea that the purpose of the history play was to vivify the moral dilemmas of power politics and to apply those lessons to contemporary government. Such lessons were heeded by contemporaries, as is amply illustrated by Elizabeth’s remark on reading about the life of one of her predecessors: “I am Richard II.”

Shakespeare’s contribution to the history-play genre is represented by two tetralogies (that is, two series of four plays), each covering a period of English history. He wrote two other plays dealing with English kings, King John and Henry VIII, but they are not specifically connected to the tetralogies in theme or structure. Edward III, written sometime between 1589 and 1595, is, on the other hand, closely related to the second tetralogy in theme, structure, and history. Edward III is the grandfather of Richard II, and his victories in France are repeated by Henry V. Muriel Bradbrook has pointed out the structural similarities between Edward III and Henry V. Like the second tetralogy as a whole, Edward III deals with the education of the prince. King Edward, like Prince Hal, at first neglects his duties and endangers the realm by placing personal pleasure above his country’s needs. The Countess of Salisbury begins his education in responsibility, and Queen Philippa completes the process by teaching him compassion. By the end of the play, Edward has become what Shakespeare callsHenry V, “the mirror of all Christian kings.”

Henry VI, Part I

The first tetralogy concerns the period from the death of Henry V in 1422 to the death of Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485. Although he probably began this ambitious project in 1588, Shakespeare apparently did not compose the plays according to a strict chronological schedule. Henry VI , Part I is generally considered to have been written after the second and third parts of the Henry story; it may also have been a revision of another play. Using details from Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland (1577) and Edward Hall’s The Union of the Two Noble and Illustre Families of Lancaster and York (1548)—his chief chronicle sources for the plays in both tetralogies—Shakespeare created in Henry VI, Part I an episodic story of the adventures of Lord Talbot, the patriotic soldier who fought bravely to retain England’s empire in France. Talbot fails and is defeated primarily because of a combination of intrigues by men such as the Bishop of Winchester and the indecisiveness of young King Henry VI.

Here, as in the other history plays, England appears as the central victim of these human actions, betrayed and abandoned by men attempting to satisfy personal desires at the expense of the kingdom. The characters are generally two-dimensional, and their speeches reveal the excesses of Senecan bombast and hyperbole. Although a few of the scenes involving Talbot and Joan of Arc—as well as Talbot’s death scene, in which his demise is made more painful by his having to witness a procession bearing his son’s corpse—aspire to the level of high drama, the play’s characters lack psychological depth, and the plot fails to demonstrate the unity of design that would mark Shakespeare’s later history plays. Joan’s nature as a strumpet-witch signals the role of other women characters in this tetralogy; Margaret, who will become England’s queen, helps to solidify the victory that Joan cleverly achieves at the close of Henry VI, Part I . Henry V’s French empire is in ruins and England’s very soul seems threatened.

Henry VI, Part II

Henry VI, Part II represents that threat in the form of what might be called “civil-war clouds.” The play focuses on the further degeneration of rule under Henry, whose ill-considered marriage to the French Margaret precipitates a power struggle involving the two houses of York and Lancaster. By eliminating wise Duke Humphrey as the chief protector of the king, Margaret in effect seizes control of the throne. In the meantime, however, a rebellion is broached by Jack Cade, the leader of a group of anarchist commoners.

This rebellion lends occasion for action and spectacle of the kind that is lacking in Henry VI, Part I . It also teaches a favorite Shakespearean lesson: The kingdom’s “children” cannot be expected to behave when their “parents” do not. Scenes involving witchcraft, a false miracle, and single combat seem to prove that the country is reverting to a primitive, chaotic state. Though the uprising is finally put down, it provides the excuse for Richard, duke of York, and his ambitious sons to seize power. York precipitates a vengeful struggle with young Clifford by killing his father; in response, Clifford murders York’s youngest son, the earl of Rutland. These murders introduce the theme of familial destruction, of fathers killing sons and sons killing fathers, which culminates in the brutal assassination of Prince Edward.

Henry VI, Part III

As Henry VI, Part III begins, England’s hopes for a strong successor to weak King Henry are dashed on the rocks of ambition and civil war. When Henry himself is murdered, one witnesses the birth of one of Shakespeare’s most fascinating villain-heroes, Richard, duke of Gloucester. Although Richard’s brother Edward becomes king and restores an uneasy peace, Shakespeare makes it clear that Richard will emerge as the political force of the future. Richard’s driving ambition also appears to characterize the Yorkist cause, which, by contrast with the Lancastrian, can be described as self-destructive on the biblical model of the Cain and Abel story. While one is made to see Richard’s wolfish disposition, however, Shakespeare also gives him a superior intellect and wit, which help to attract one’s attention and interest. Displaying touches of the irony and cruelty that will mark his behavior in Richard III, Richard declares at the close of Henry VI, Part III : “See how my sword weeps for the poor king’s death.”

Richard III

In order to present Richard as an arch-villain, Shakespeare was obliged to follow a description of him that was based on a strongly prejudiced biographical portrait written by Sir ThomasMore.More painted Richard as a hunchback with fangs, a beast so cruel that he did not flinch at the prospect of murdering the young princes. To More—and to Shakespeare—Richard must be viewed as another Herod; the imagery of the play also regularly compares him to a boar or hedgehog, beasts that know no restraint. Despite these repulsive features, Richard proves to be a consummate actor, outwitting and outperforming those whom he regards as victims. The most theatrical scene in the play is his wooing of the Lady Anne, who is drawn to him despite the knowledge that he has killed her husband (Prince Edward) and fatherin- law, whose corpse she is in the process of accompanying to its grave. Many of the audacious wooing tricks used in this scene suggest that one of the sources for Richard’s character is the Vice figure from medieval drama.

Richard III documents the breakneck pace and mounting viciousness of Richard’s course to the throne. (Steeplechase imagery recurs throughout, culminating in the picture of Richard as an unseated rider trying desperately to find a mount.) He arranges for the murder of his brother Clarence, turns on former supporters such as Hastings and Buckingham, whom he seemed to be grooming for office, and eventually destroys the innocent princes standing in his path. This latter act of barbarism qualifies as a turning point, since Richard’s victories, which have been numerous and easily won, now begin to evaporate at almost the same rate of speed.

While Richard moves with freedom and abandon from one bloody deed to another, he is hounded by the former Queen Margaret, who delivers curses and prophecies against him in the hope of satisfying her vengeful desires. She plays the role of a Senecan fury, even though her words prove feeble against her Machiavellian foe. Retribution finally comes, however, in the character of the Lancastrian Earl of Richmond, who defeats Richard at Bosworth Field. On the eve of the battle, Richard’s victims visit his sleep to announce his fall, and for the first time in the play, he experiences a twinge of conscience. Unable to respond by confessing and asking forgiveness, Richard fights fiercely, dying like a wounded animal that is finally cornered. With Richmond’s marriage to Elizabeth York, theWars of the Roses end, and England looks forward to a prosperous and peaceful future under Henry Richmond, founder of the Tudor line.

Whether Shakespeare wrote King John in the period between the first and second tetralogies is not known, but there is considerable support for the theory that he did. In the play, he depicts the career of a monarch who reigned into the thirteenth century and who defied papal authority, behavior that made him into something of a Protestant hero for Elizabethans. Shakespeare’s John, however, lacks both the dynamism and the charisma of Henry V; he is also guilty of usurping the throne and arranging for the death of the true heir, Arthur.

This clouded picture complicates the action and transforms John into a man plagued by guilt. Despite his desire to strengthen England and challenge the supremacy of Rome, John does not achieve either the dimensions of a tragic hero or the sinister quality of a consummate villain; indeed, his death seems anticlimactic. The strongest personality in the play belongs to Faulconbridge the Bastard, whose satiric commentary on the king’s maneuvering gives way to patriotic speeches at the close. Faulconbridge speaks out for Anglo-Saxon pride in the face of foreign challenge, but he has also played the part of satirist-onstage throughout much of the action. Something of the same complexity of character will be seen in Prince Hal, the model fighter and king of the second tetralogy.

In King John, Shakespeare managed only this one touch of brilliant characterization in an otherwise uninteresting and poorly constructed play. He may have been attempting an adaptation of an earlier chronicle drama.

Shakespeare began writing the second tetralogy, which covers the historical period from 1398 to 1422, in 1595. The first play in this group was Richard II , a drama which, like the Henry VI series, recounts the follies of a weak king and the consequences of these actions for England. Unlike Henry, however, Richard is a personage with tragic potential; he speaks the language of a poet and possesses a self-dramatizing talent. Richard invites his fall—the fall of princes, or de casibus virorum illustrium , being a favorite Elizabethan topic that was well represented in the popular A Mirror for Magistrates (first published under Elizabeth I in 1559, although printed earlier under Queen Mary)—by seizing the land of the deceased John of Gaunt to pay for his war preparations against Ireland. This dubious act brings Henry Bolingbroke, Gaunt’s son, rushing back from France, where he had been exiled by Richard, for a confrontation with the king. The result of their meeting is Richard’s sudden deposition—he gives up the crown almost before he is asked for it—and eventual death, which is so movingly rendered that many critics have been led to describe this as a tragedy rather than a political play.

Such a reading must overlook the self-pitying quality in Richard; his actions rarely correspond to the quality of his speech. Yet there has been little disagreement about Shakespeare’s achievement in advancing the history-play form by forging a world in which two personalities, one vacillating, the other resourceful, oppose each other in open conflict. Richard II likewise qualifies as the first play in which Shakespeare realizes the theme of the fall by means of repeated images comparing England to a garden. Richard, the gardener-king, has failed to attend to pruning; rebels, like choking weeds, grow tall and threaten to blot out the sun. Because Bolingbroke usurps the crown and later arranges for Richard’s death, however, he is guilty of watering the garden with the blood of England’s rightful—if foolish—ruler. The result must inevitably be civil war, which is stirringly prophesied by the Bishop of Carlisle as the play draws to a close: “The blood of English shall manure the ground,/ And future ages groan for this foul act.”

Henry IV, Part I

The civil strife that Carlisle predicted escalates in Henry IV, Part I. Bolingbroke, now King Henry IV, is planning a crusade in the midst of a serious battle involving rebels in the north and west of Britain. This obliviousness to responsibility is clearly motivated by Henry’s guilt over the seizing of the crown and Richard’s murder. It will take the courage and ingenuity of his son, Prince Hal, the future Henry V, to save England and to restore the order of succession that Shakespeare and his contemporaries saw as the only guarantee of peaceful rule. Thus, Henry IV, Part I is really a study of the rise of Hal, who in the opening of the play appears to be a carefree time waster, content with drinking, gambling, and carousing with a motley group of thieves and braggarts led by the infamous coward Sir John Falstaff. Using a kind of Aristotelian mode of characterization, Shakespeare reveals Hal as a balanced hero who possesses the wit and humanity of Falstaff, without the debilitating drunkenness and ego, and the physical courage and ambition of Henry Hotspur, the son of the earl of Northumberland and chief rebel, without his destructive choler and impatience.

The plot of Henry IV, Part I advances by means of comparison and contrast of the court, tavern, and rebel worlds, all of which are shown to be in states of disorder. Hal leaves the tavern world at the end of the second act with an explicit rejection of Falstaff’s fleshly indulgence; he rejoins his true father and leads the army in battle against the rebels, who are unable to organize the English,Welsh, and Scottish factions of which they are formed. They seem to be leaderless—and “fatherless.” Above all, Hal proves capable of surprising both his own family and the rebels, using his reputation as a madcap to fullest advantage until he is ready to throw off his disguise and defeat the bold but foolish Hotspur at Shrewsbury. This emergence is nicely depicted in imagery associated by Hal himself with the sun (punning on “son”) breaking through the clouds when least suspected. Falstaff demonstrates consistency of character in the battle by feigning death; even though Hal allows his old friend to claim the prize of Hotspur’s body, one can see the utter bankruptcy of the Falstaffian philosophy of selfpreservation.

Henry IV, Part II

In Henry IV, Part II, the struggle against the rebels continues. Northumberland, who failed to appear for the Battle of Shrewsbury because of illness, proves unable to call up the spirit of courage demonstrated by his dead son. Glendower, too, seems to fade quickly from the picture, like a dying patient. The main portion of the drama concerns what appears to be a replay of Prince Hal’s reformation. Apparently Shakespeare meant to depict Hal’s acquisition of honor and valor at the close of Henry IV, Part I, while Part II traces his education in the virtues of justice and rule. Falstaff is again the humorous but negative example, although he lacks the robustness in sin that marked his character in Part I. The positive example or model is the Lord Chief Justice, whose sobriety and sense of responsibility eventually attract Hal to his side.

As in Part I, Shakespeare adopts the structure of a medieval morality play to depict the rejection of the “bad” angel (or false father) and the embracing of the “good” one (or spiritual father) by the hero. The banishment of Falstaff and his corrupt code takes place during the coronation procession. It is a particularly poignant moment—to which many critics object, since Hal’s harshness seems so uncharacteristic and overdone— but this scene is well prepared for by Hal’s promise, at the end of act 2 in Part I, that he would renounce the world and the flesh at the proper time. The example of Hal’s father, whose crown Hal rashly takes from his pillow before his death, demonstrates that for the king there can be no escape from care, no freedom to enjoy the fruits of life. With the Lord Chief Justice at his side, Hal prepares to enter the almost monklike role that the kingship requires him to play.

It is this strong and isolated figure that dominates Henry V , the play that may have been written for the opening of the Globe Theatre. Appropriately enough, the Chorus speaker who opens the play asks if “this wooden O” can “hold the vasty fields of France,” the scene of much of the epic and episodic action. Hal shows himself to be an astute politician—he outwits and traps the rebels Scroop, Cambridge, and Grey—and a heroic leader of men in the battle scenes. His rejection of Falstaff, whose death is recounted here in tragicomic fashion by Mistress Quickly, has transformed Hal’s character into something cold and unattractive. There is little or no humor in the play. Yet when Hal moves among his troops on the eve of the Battle of Agincourt, he reveals a depth of understanding and compassion that helps to humanize his character. His speeches are masterpieces of political rhetoric, even though Pistol, the braggart soldier, tries to parody them. “Once more into the breach, dear friends, once more . . .” introduces one of the best-known prebattle scenes in the language.

With the defeat of the French at Agincourt, Hal wins an empire for England, strengthening the kingdom that had been so sorely threatened by the weakness of Richard II. Both tetralogies depict in sharp outline the pattern of suffering and destruction that results from ineffective leadership. In Henry VII and Henry V, one sees the promise of peace and empire realized through the force of their strong, patriotic identities. At the close of Henry V , the hero’s wooing of Katherine of France, with its comic touches resulting from her inability to speak English, promises a wedding that will take place in a new garden from which it is hoped humankind will not again fall. The lesson for the audience seems to be that under Elizabeth, the last Tudor monarch, England has achieved stability and glory, and that this role of European power was foreshadowed by the victories of these earlier heroes. Another clear lesson is that England cannot afford another civil war; some capable and clearly designated successor to Elizabeth must be chosen.

Shakespeare’s last drama dealing with English history, a probable collaboration with Henry Fletcher, is Henry VIII, which is normally classed with romances such as The Tempest and Cymbeline. It features none of the military battles typical of earlier history plays, turning instead for its material to the intrigues of Henry’s court. The play traces the falls of three famous personages, the duke of Buckingham, Katherine of Aragon, and Cardinal Wolsey. Both Buckingham and Queen Katherine are innocent victims of fortune, while Wolsey proves to be an ambitious man whose scheming is justly punished. Henry seems blind and self-satisfied through much of the play, which is dominated by pageantry and spectacle, but in his judgment against Wolsey and his salvation of Cranmer, he emerges as something of a force for divine justice. The plot ends with the christening of Elizabeth and a prophecy about England’s glorious future under her reign. Shakespeare’s audience knew, however, that those atop Fortune’s wheel at the close—Cranmer and Anne Bullen, in particular—would soon be brought down like the others. This last of Shakespeare’s English history plays, then, sounds a patriotic but also an ironic note.

The Comedies

Of the plays that are wholly or partly attributed to Shakespeare, nearly half have been classified as comedies. In addition, many scenes in plays such as Henry IV, Part I and Romeo and Juliet feature comic characters and situations. Even in the major tragedies, one finds scenes of comic relief: the Porter scene in Macbeth , the encounters between the Fool and Lear in King Lear, Hamlet’s inventive punning and lugubrious satire. There can be little doubt that Shakespeare enjoyed creating comic situations and characters and that audiences came to expect such fare on a regular basis from the playwright. The

Comedy of Errors

In his first attempt in the form, The Comedy of Errors , Shakespeare turned to a source—Plautus, the Roman playwright—with which he would have become familiar at Stratford’s grammar school. Based on Plautus’s Menaechmi ( The Twin Menaechmi, 1595), the comedy depicts the misadventures of twins who, after several incidents involving mistaken identity, finally meet and are reunited. The twin brothers are attended by twin servants, compounding the possibilities for humor growing out of mistaken identity.

Considerable buffoonery and slapstick characterize the main action involving the twins—both named Antipholus—and their servants. In one hilarious scene, Antipholus of Ephesus is turned away from his own house by a wife who believes he is an impostor. This somewhat frivolous mood is tempered by the presence of the twins’ father in the opening and closing scenes. At the play’s opening, Egeon is sentenced to death by the Duke of Ephesus; the sentence will be carried out unless someone can pay a ransom set at one thousand marks. Egeon believes that his wife and sons are dead, which casts him deep into the pit of despair. By the play’s close, Egeon has been saved from the duke’s sentence and has been reunited with his wife, who has spent the many years of their separation as an abbess. This happy scene of reunion and regeneration strikes a note that will come to typify the resolutions of later Shakespearean comedy. Providence appears to smile on those who suffer yet remain true to the principle of family.

Shakespeare also unites the act of unmasking with the concept of winning a new life in the fifth act of The Comedy of Errors . Both Antipholus of Syracuse, who in marrying Luciana is transformed into a “new man,” and Dromio of Ephesus, who is freed to find a new life, acquire new identities at the conclusion. The characters are, however, largely interchangeable and lacking in individualizing traits. Types rather than fullblown human beings people the world of the play, thus underscoring the theme of supposing or masking.

Shakespeare offers a gallery of familiar figures—young lovers, a pedantic doctor, a kitchen maid, merchants, and a courtesan—all of whom are identified by external traits. They are comic because they behave in predictably mechanical ways. Dr. Pinch, the mountebank based on Plautus’s medicus type, is a good example of this puppetlike caricaturing. The verse is designed to suit the speaker and occasion, but it also reveals Shakespeare’s range of styles; blank verse, prose, rhymed stanzas, and alternating rhymed lines can be found throughout the play. This first effort in dramatic comedy was an experiment using numerous Plautine elements, but it also reveals, in the characters Egeon and Emilia, the playwright’s talent for humanizing even the most typical of characters and for creating life and vigor in stock situations.

The Taming of the Shrew

In The Taming of the Shrew , Shakespeare turned to another favorite source for the theme of transformation: Ovid’s Metamorphoses (c. 8 c.e.; English translation, 1567). He had already used this collection for his erotic poems Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece ; now he plundered it for stories about pairs of lovers and the changes effected in their natures by the power of love. In The Taming of the Shrew, he was also improving on an earlier play that dealt with the theme of taming as a means of modifying human behavior.

Petruchio changes Kate’s conduct by regularly praising her “pleasant, gamesome” nature. By the end of the play, she has been tamed into behaving like a dutiful wife. (Her sister Bianca, on the other hand, has many suitors, but her father will not allow Bianca to marry until Kate has found a husband.) The process of taming sometimes involves rough and boisterous treatment—Petruchio withholds food from his pupil, for example—as well as feigned madness: Petruchio whisks his bride away from the wedding site as if she were a damsel in distress and he were playing the role of her rescuer. In the end, Kate turns out to be more pliant than her sister, suggesting that an ideal wife, like a bird trained for the hunt, must be instructed in the rules of the game.

Shakespeare reinforces the theme of transformation by fashioning a subplot featuring a drunken tinker named Christopher Sly, who believes he has been made into a lord during a ruse performed by a fun-loving noble and his fellows. The Sly episode is not resolved because this interlude ends with the play’s first scene, yet by employing this framing device, Shakespeare invites a comparison between Kate and Sly, both of whom are urged to be “better” than they thought they were.

The Two Gentlemen of Verona

The Two Gentlemen of Verona takes a comic tack that depends less on supposing than on actual disguise. Employing a device he would later perfect in As You Like It and Twelfth Night , Shakespeare put his heroine Julia in a page’s outfit in order to woo her beloved Proteus.

The main theme of the comedy is the rocky nature of love as revealed in male friendship and romantic contest. Valentine, Proteus’s friend, finds him to be fickle and untrue to the courtly code when Proteus tries to force his affections on Silvia, Valentine’s love. Although Proteus deserves worse punishment than he receives, he is allowed to find in Julia the true source of the romantic love that he has been seeking throughout the play. These pairs of lovers and their clownish servants, who engage in frequent bouts of punning and of horseplay, perform their rituals—anatomizing lovers, trusting false companions—in a forest world that seems to work its magic on them by bringing about a happy ending.

As in the other festive comedies, The Two Gentlemen of Verona concludes with multiple marriages and a mood of inclusiveness that gives even the clowns their proper place in the celebration. The passion of love has led Proteus (whose name, signifying “changeable,” symbolizes fickleness) to break oaths and threaten friendships, but in the end, it has also forged a constant love.

Love’s Labour’s Lost

After this experiment in romantic or festive (as opposed to bourgeois) comedy, Shakespeare next turned his hand to themes and characters that reflect the madness and magic of love. Love’s Labour’s Lost pokes fun at florid poetry, the “taffeta phrases [and] silken terms precise” that typified Elizabethan love verses. There is also a satiric strain in this play, which depicts the foiled attempt of male characters to create a Platonic utopia free of women. The King of Navarre and his court appear ludicrous as, one by one, they violate their vows of abstinence in conceits that gush with sentiment. Even Berowne, the skeptic-onstage, proves unable to resist the temptations of Cupid.

As if to underscore the foolishness of their betters, the clowns and fops of this comic world produce an interlude featuring the NineWorthies, all of whom overdo or distort their roles in the same way as the lover-courtiers have distorted theirs. (This interlude was also the playwright’s first attempt at a play-within-a-play.) When every Jack presumes to claim his Jill at the close, however, Shakespeare deputizes the princess to postpone the weddings for one year while the men do penance for breaking their vows. The women here are victorious over the men, but only for the purpose of forcing them to recognize the seriousness of their contracts. Presumably the marriages to come will prove constant and fulfilling, but at the end of this otherwise lighthearted piece, Shakespeare interjects a surprising note of qualification. Perhaps this note represents his commentary on the weight of words, which the courtiers have so carelessly— and sometimes badly—handled.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream , Shakespeare demonstrates consummate skill in the use of words to create illusion and dreams. Although he again presents pairs of young lovers whose fickleness causes them to fall out of, and then back into, love, these characters display human dimensions that are missing in the character types found in the earlier comedies. The multiple plots concern not only the lovers’ misadventures but also the marriage of Duke Theseus and Hippolyta, the quarrel between Oberon and Titania, king and queen of the fairy band, and the bumbling rehearsal and performance of the play-within-a-play Pyramus and Thisbe by Bottom and his companions. All of these actions illustrate the themes of love’s errant course and of the power of illusion to deceive the senses.

The main action, as in The Two Gentlemen of Verona, takes place in a wood, this time outside Athens and at night. The fairy powers are given free rein to deceive the mortals who chase one another there. Puck, Oberon’s servant, effects deception of the lovers by mistakenly pouring a potion in the wrong Athenian’s eyes. By the end of the play, however, the young lovers have found their proper partners, Oberon and Titania have patched up their quarrel, and Bottom, whose head was changed into that of an ass and who was wooed by the enchanted Titania while he was under this spell, rejoins his fellows to perform their tragic and comic interlude at the wedding reception. This afterpiece is a burlesque rendition of the story of Pyramus and Thisbe, whose tale of misfortune bears a striking resemblance to that of Romeo and Juliet . Through the device of the badly acted play-within-the-play, Shakespeare instructs his audience in the absurdity of lovers’ Petrarchan vows and in the power of imagination to transform the bestial or the godlike into human form. In design and execution, A Midsummer Night’s Dream , with its variety of plots and range of rhyme and blank verse, stands out as Shakespeare’s most sophisticated early comedy.

The Merchant of Venice

The Merchant of Venice shares bourgeois features with The Taming of the Shrew and The Two Gentlemen of Verona , but it has a much darker, neartragic side, too. Shylock’s attempt to carve a pound of flesh from the merchant Antonio’s heart has all the ingredients of tragedy: deception, hate, ingenuity, and revenge. His scheme is frustrated only by the superior wit of the heroine Portia during a trial scene in which she is disguised as a young boy judge. Requiring Shylock to take nothing more than is specified in his bond, while at the same time lecturing him on the quality of mercy, Portia’s speeches create the elements of tension and confrontation that will come to epitomize the playwright’s mature tragedies.With the defeat and conversion of Shylock, the pairs of lovers can escape the threatening world of Venice and hope for uninterrupted happiness in Belmont, Portia’s home.

Venice, the scene of business, materialism, and religious hatred, is contrasted with Belmont (or “beautiful world”), the fairy-tale kingdom to which Bassanio, Antonio’s friend, has come to win a fair bride and fortune by entering into a game of choice involving golden, silver, and leaden caskets. Though the settings are contrasted and the action of the play alternates between the two societies, Shakespeare makes his audience realize that Portia, like Antonio, is bound to a contract (set by her dead father) which threatens to destroy her happiness. When Bassanio chooses the leaden casket, she is freed to marry the man whom she would have chosen for her own. Thus “converted” (a metaphor that refers one back to Shylock’s conversion), Portia then elects to help Antonio, placing herself in jeopardy once again. Portia emerges as Shakespeare’s first major heroine-in-disguise, a character-type central to his most stageworthy and mature comedies , Twelfth Night and As You Like It.

Much Ado About Nothing

Much Ado About Nothing likewise has a dark side. The main plot represents the love of Claudio and Hero. Hero’s reputation is sullied by the melodramatic villain Don Juan. Claudio confronts his supposedly unfaithful partner in the middle of their wedding ceremony, his tirade causing her to faint and apparently expire. The lovers are later reunited, however, after Claudio recognizes his error. This plot is paralleled by one involving Beatrice and Benedick, two witty characters who in the play’s beginning are set against each other in verbal combat. Like Claudio and Hero, they are converted into lovers who overcome selfishness and pride to gain a degree of freedom in their new relationships. The comedy ends with the marriage of Claudio and Hero and the promise of union between Beatrice and Benedick.

A central comic figure in the play is Dogberry, the watchman whose blundering contributes to Don Juan’s plot but is also the instrument by which his villainy is revealed. His behavior, especially his hilariously inept handling of legal language, is funny in itself, but it also illustrates a favorite Shakespearean theme: Clownish errors often lead to happy consequences. Like Bottom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream , Dogberry and his men are made an important part of the newly transformed society at the end of the play.

As You Like It

As You Like It and Twelfth Night are widely recognized as Shakespeare’s wittiest and most stageworthy comedies; they also qualify as masterpieces of design and construction. In As You Like It, the action shifts from the court of Duke Frederick, a usurper, to the forest world of Arden, the new “court” of ousted Duke Senior. His daughter Rosalind enters the forest world in disguise, along with her friend Celia, to woo and win the young hero Orlando, forced to wander by his brother Oliver, another usurping figure. Although his florid verses expressing undying love for Rosalind are the object of considerable ridicule, Orlando earns the title of true lover worthy of Rosalind’s hand. She proves successful in winning the support of the audience by means of her clever manipulation of Orlando from behind her mask. His inept poetry and her witty commentary can be taken “as we like it,” as can the improbable conversions of Oliver and Duke Frederick that allow for a happy ending.

Two characters—Touchstone, the clown, and Jacques (pronounced JAYK weez), the cynical courtier—represent extreme attitudes on the subjects of love and human nature. Touchstone serves as Rosalind’s protector and as a sentimental observer, commenting wistfully and sometimes wittily on his own early days as a lover of milkmaids. Jacques, the trenchant commentator on the “Seven Ages of Man,” sees all this foolery as further evidence, along with political corruption and ambition, of humankind’s fallen state. He remains outside the circle of happy couples at the end of the play, a poignant, melancholy figure. His state of self-centeredness, it might be argued, is also “as we like it” when our moods do not identify so strongly with youthful exuberance.

Twelfth Night

Twelfth Night also deals with the themes of love and self-knowledge. Like As You Like It, it features a disguised woman, Viola, as its central figure. Motifs from other earlier Shakespearean comedies are also evident in Twelfth Night . Viola and Sebastian are twins (a motif found in The Comedy of Errors ) who have been separated in a shipwreck but, unknown to each other, have landed in the same country, Illyria. From The Two Gentlemen of Verona , Shakespeare took the motif of the disguised figure serving as page to the man she loves (Duke Orsino) and even playing the wooer’s role with the woman (Olivia) whom the duke wishes to marry. Complications arise when Olivia falls in love with Viola, and the dilemma is brought to a head when Orsino threatens to kill his page in a fit of revenge. Sebastian provides the ready solution to this dilemma, but Shakespeare holds off introducing the twins to each other until the last possible moment, creating effective comic tension.

The play’s subplot involves an ambitious and vain steward, Malvolio, who, by means of a counterfeited letter (the work of a clever servant named Maria), is made to believe that Olivia loves him. The scene in which Malvolio finds the letter and responds to its hints, while being observed not only by the theater audience but also by an audience onstage, is one of the funniest stretches of comic pantomime in drama. When Malvolio attempts to woo his mistress, he is thought mad and is cast in prison. Although he is finally released (not before being tormented by Feste the clown in disguise), Malvolio does not join the circle of lovers in the close, vowing instead to be revenged on all those who deceived him. In fact, both Feste and Malvolio stand apart from the happy company, representing the dark, somewhat melancholy clouds that cannot be dispelled in actual human experience. By this stage in his career, Shakespeare had acquired a vision of comedy crowded by elements and characters that would be fully developed in the tragedies.

The Merry Wives of Windsor

The Merry Wives of Windsor was probably composed before Shakespeare reached the level of maturity reflected in As You Like It and Twelfth Night . Legend suggests that he interrupted his work on the second history cycle to compose the play in two weeks for Queen Elizabeth, who wished to see Falstaff (by then familiar from the history plays) portrayed as a lover. What Shakespeare ended up writing was not a romantic but instead a bourgeois comedy that depicts Falstaff attempting to seduce Mistress Ford and Mistress Page, both wives of Windsor citizens. He fails, but in failing he manages to entertain the audience with his bragging and his boldness. Shakespeare may have been reworking an old play based on a Plautine model; in one of Plautus’s plays, there is a subplot in which a clever young man (Fenton) and his beloved manage to deceive her parents in order to get married. This is the only strain of romance in the comedy, whose major event is the punishment of Falstaff: He is tossed into the river, then singed with candles and pinched by citizens disguised as fairies. Critics who see Falstaff as the embodiment of Vice argue that this punishment has symbolic weight; his attempted seduction of honest citizens’ wives makes him a threat to orderly society. Regardless of whether this act has a ritual purpose, the character of Falstaff, and the characters of Bardolph, Pistol, and Justice Shallow, bear little resemblance to the comic band of Henry IV, Part I. In fact, T he Merry Wives of Windsor might be legitimately seen as an interlude rather than a fully developed comedy, and it is a long distance from the more serious, probing dramas Shakespeare would soon create.

All’s Well That Ends Well

All’s Well That Ends Well and Measure for Measure were composed during a period when Shakespeare was also writing his major tragedies. Because they pose questions about sin and guilt that are not satisfactorily resolved, many critics have used the terms “dark comedies” or “problem plays” to describe them. All’s Well That Ends Well features the familiar disguised heroine (Helena) who pursues the man she loves (Bertram) with skill and determination.

The play differs from the earlier romantic comedies, however, because the hero rejects the heroine, preferring instead to win honor and fame in battle. Even though Helena is “awarded” the prize of Bertram by the King of France, whom she has cured of a near-fatal disease, she must don her disguise and pursue him while undergoing considerable suffering and hardship. In order to trap him, moreover, she must resort to a “bed trick,” substituting her body for that of another woman whom Bertram plans to seduce. When Bertram finally assents to the union he bears little resemblance to comic heroes such as Orlando or Sebastian; he could be seen in fact as more a villain (or perhaps a cad) than a deserving lover. The forced resolution makes the play a “problem” for many critics, but for Shakespeare and his audience, the ingenuity ofHelena and the multiple marriages at the close probably satisfied the demands of romantic comedy.

Measure for Measure

Measure for Measure has at the center of its plot another bed trick, by which a patient and determined woman (Mariana) manages to capture the man she desires. That man, Angelo, is put in the position of deputy by Duke Vincentio at the opening of the action.He determines to punish a sinful Vienna by strictly enforcing its laws against fornication; his first act is to arrest Claudio for impregnating his betrothed Juliet. When Isabella, Claudio’s sister, who is about to take vows as a nun, comes to plead for his life, Angelo attempts to seduce her. He asks for a measure of her body in return for a measure of mercy for her brother. Isabella strongly resists Angelo’s advances, although her principled behavior most certainly means her brother will die. Aided by Vincentio, disguised as a holy father, Isabella arranges for Mariana to take her place, since this woman is in fact Angelo’s promised partner. Thus, Angelo commits the deed that he would punish Claudio for performing. (Instead of freeing Claudio, moreover, he sends word to have him killed even after seducing his “sister.”)

Through another substitution, however, Claudio is saved. In an elaborate judgment scene, in which Vincentio plays both duke and holy father, Angelo is forgiven— Isabella being required by the duke to beg for Angelo’s life—and marries Mariana. Here, as in All’s Well That Ends Well , the hero proves to be an unpunished scoundrel who seems to be in fact rewarded for his sin, but the biblical “Judge not lest ye be judged” motivates much of the action, with characters finding themselves in the place of those who would judge them and being forced to display mercy. Some critics have argued that this interpretation transforms Duke Vincentio into a Christ figure, curing the sins of the people while disguised as one of them. Whether or not this interpretation is valid, Measure for Measure compels its audience to explore serious questions concerning moral conduct; practically no touches of humor in the play are untainted by satire and irony.

The Tragedies

For about four years following the writing of Measure for Measure , Shakespeare was busy producing his major tragedies. It is probably accurate to say that the problem comedies were, to a degree, testing grounds for the situations and characters he would perfect in the tragedies. These tragedies include the famous Romeo and Juliet, Julius Caesar, Hamlet, Prince of Denmark , Othello, the Moor of Venice , King Lear, and Antony and Cleopatra . His earliest—and clumsiest—attempt at tragedy was Titus Andronicus .

Titus Andronicus

The plot of Titus Andronicus no doubt came from the Roman poet Ovid, a school subject and one of the playwright’s favorite Roman authors. From Seneca, the Roman playwright whose ten plays had been translated into English in 1559, Shakespeare took the theme of revenge: The inflexible, honor-bound hero seeks satisfaction against a queen who has murdered or maimed his children. She was acting in retaliation, however, because Titus had killed her son. Titus’s rage, which is exacerbated by the rape and mutilation of his daughter Lavinia, helps to classify him as a typical Senecan tragic hero. He and the wicked queen Tamora are oversimplified characters who declaim set speeches rather than engaging in realistic dialogue. Tamora’s lover and accomplice, the Moor Aaron, is the prototype of the Machiavellian practitioner that Shakespeare would perfect in such villains as Iago and Edmund. While this caricature proves intriguing, and while the play’s structure is more balanced and coherent than those of the early history plays, Titus’s character lacks the kind of agonizing introspection shown by the heroes of the major tragedies. He never comes to terms with the destructive code of honor that convulses his personal life and that of Rome.

Romeo and Juliet

With Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare reached a level of success in characterization and design far above the bombastic and chaotic world of Titus Andronicus . Based on a long narrative and heavily moralized poem by Arthur Brooke, this tragedy of “star-crossed lovers” excites the imagination by depicting the fatal consequences of a feud between the Veronese families of Montague and Capulet. Distinguished by some of Shakespeare’s most beautiful poetry, the style bears a strong resemblance to that of the sonnets: elaborate conceits, classical allusions, witty paradoxes, and observations on the sad consequences of sudden changes of fortune. Some critics have in fact faulted the tragedy because its plot lacks the integrity of its poetry; Romeo and Juliet come to their fates by a series of accidents and coincidences that strain credulity. The play also features abundant comic touches provided by the remarks of Romeo’s bawdy, quick-witted friendMercutio and the sage but humorous observations of Juliet’s nurse. Both of these “humor” characters (character types whose personalities are determined by one trait, or “humor”) remark frequently, and often bawdily, on the innocent lovers’ dreamy pronouncements about their passion for each other.

With the accidental murder of Mercutio, whose last words are “A plague on both your houses!” (referring to the feuding families), the plot accelerates rapidly toward the catastrophe, showing no further touches of humor or satire. The tireless Friar Lawrence attempts, through the use of a potion, to save Juliet from marrying Paris, the nobleman to whom she is betrothed, but the friar proves powerless against the force of fate that seems to be working against the lovers. Although it lacks the compelling power of the mature tragedies, whose heroes are clearly responsible for their fate, Romeo and Juliet remains a popular play on the subject of youthful love. The success of various film versions, including Franco Zeffirelli’s 1968 feature film, with its teenage hero and heroine and its romantically moving score, proved that the play has a timeless appeal.

Julius Caesar

At least three years passed before Shakespeare again turned his attention to the tragic form. Instead of treating the subject of fatal love, however, he explored Roman history for a political story centering on the tragic dilemma of one man. In Julius Caesar, he could have dealt with the tale of the assassination of Caesar, taken from Plutarch’s Bioi paralleloi (c. 105-115 c.e.; Parallel Lives , 1579), as he did with material from English history in the chronicle dramas he had been writing in the 1590’s. That is, he might have presented the issue of the republic versus the monarchy as a purely political question, portraying Caesar, Brutus, Cassius, and Antony as pawns in a predestined game. Instead, Shakespeare chose to explore the character of Brutus in detail, revealing the workings of his conscience through moving and incisive soliloquies. By depicting his hero as a man who believes his terrible act is in the best interest of the country, Shakespeare establishes the precedent for later tragic heroes who likewise justify their destructive deeds as having righteous purposes.