Your web browser is outdated and may be insecure

The RCN recommends using an updated browser such as Microsoft Edge or Google Chrome

Reflective journal writing: how can it help?

Discover the benefits of writing down your thoughts and how to get started

Reflective journal writing is a way of documenting what you’re thinking and feeling in the moment, and can be a useful tool to help manage stress and anxiety.

Dr Christopher Westoby, author of The Fear Talking: The True Story of a Young Man and Anxiety, is a strong believer in the power of stories to educate, improve understanding and benefit the wellbeing of the storyteller.

We spoke to Chris about the benefits of writing for your mental wellbeing.

Can reflective writing help nursing staff?

Absolutely. Regardless of your background, and wherever you work, everyone has this universal need to reflect upon their own experiences and one of the best tools we have for that is writing. It is similar to the process of opening the windows to a room and letting some air in.

Everyone has this universal need to reflect upon their own experiences

We all have so many thoughts and memories whirling round our head at any given time – especially in the current climate. Sometimes the cloud of everything happening at once can be more overwhelming than any one event itself. Reflective journal writing can help with that.

How does it help?

We often struggle to come to terms with whatever it is we’ve been through unless we take a second and address these things head on. And while it may not always be an easy thing to do – or a quick fix – by writing what’s going on internally, what you’re doing is externalising something that has been haunting you or playing on your mind. Once it’s out there on the page, it’s like you can lay it to rest.

You also now have a choice on what you want to do with it. Are you going to delete it or keep it for yourself? Are you going to let someone else read it? As you make those decisions, you’re taking control of your emotions and the clouds may start to clear.

So, what are the benefits?

The sense of control over your own experiences can be empowering and help relieve any stress or anxiety you’re experiencing. You’ve let it be acknowledged that what you’re feeling is something, it’s being validated and now it’s written down, it may no longer feel quite so insurmountable.

Any tips to get started?

My first tip is to use whatever format works best for you – whatever it is that will help get you in the habit of doing it. Don’t use handwriting if you’d rather type, and vice versa.

I’ve worked with students before who have talked about using voice memos. They’ve just hit record and then they either deleted it or transcribed it depending on what they’ve found most beneficial.

My second tip is to think of prompts. Maybe ask yourself questions to help get you started – what am I grateful for? What have I found difficult? Perhaps focus on one part of the day – how did I feel after my shift? On the way to work? Going to bed?

Finally, think about setting yourself some restrictions. Try setting a timer on your phone and then keep writing until it goes off. The more restrictions you set, the less daunting writing can be. You might actually find yourself more inspired.

How often should I write?

It’s a good thing to try and do every day – even if it’s only a few sentences – for as long as you find it useful. I’d suggest giving it a go for two weeks and see how you’re finding it.

What if I find it hard writing about myself?

If it seems too difficult writing about yourself, try writing about someone else or something you observed today – perhaps something you noticed on your journey home or through your window. If you write about something else, you will inevitably find yourself beginning to include elements of yourself.

If you’re finding it too emotionally draining to revisit certain memories, remember this writing is your property – you can change what you need to, you can change the details and you can just talk about a small part of it. The key is to remember that you’re in control and it’s up to you how you document it.

The key is to remember you're in control

There are fewer ways to offload to one another at the moment, to distract ourselves and to blow off steam, so even if journal writing doesn’t work for you, it’s worth a try.

The benefits might surprise you.

About Chris

Chris is Programme Director of the Hull Creative Writing MA (Online). His book The Fear Talking: The True Story of a Young Man and Anxiety was published in December 2020. He led the RCN’s workshop “Time to Write for Yourself” last year.

The power of plants

Good for us, great for patients – here’s why houseplants benefit everyone

‘Patient attack forced me to leave nursing'

How the RCN helped one member get compensation after a shocking workplace incident

5 simple exercises for nursing staff

Tackle back and neck pain with these easy exercises

Tiring, distressing, emotional: the realities of giving CPR

And why debriefs are so important

‘My doodles represent a silent scream’

How art helped this nurse with stress

A second chance at nursing

Hannah's story of hope after mental illness

{{ article.Title }}

{{ article.Summary }}

Chapter 4: Types of Writing

Reflective Writing

What it is.

Have you ever been asked to reflect on a text or an experience?

Reflective writing is used by different healthcare professions in various ways, but all reflective writing requires that you think deeply and critically about an experience or a text. At the centre of reflective writing is the “self” – including a deep analysis of you in relation to the topic. Reflective writing is a process that involves recalling an experience or an event, thinking and deliberating about it, and then writing about it.

You may be asked to engage in reflective writing related to an array of topics: the reading you are doing for a course, your experience working in a group, how you solved a problem, how you prepared for class or for an exam, a healthcare issue or a new theory. You will be expected to reflect on your clinical practice often throughout your nursing studies and for the rest of your nursing career to grow, learn, and demonstrate your continuing competence.

In nursing, reflective writing is part of what is called “ reflective practice . ” Early in your nursing program, you will become familiar with the College of Nurses of Ontario requirements for nurses to engage in reflective practice: this legislated professional expectation involves an intentional process of reflecting to explore and analyze a clinical experience so that you can “identify your strengths and areas for improvement” with the aim of strengthening your practice (College of Nurses of Ontario, 2019).

Figure 4.3: Reflective writing

How to do it?

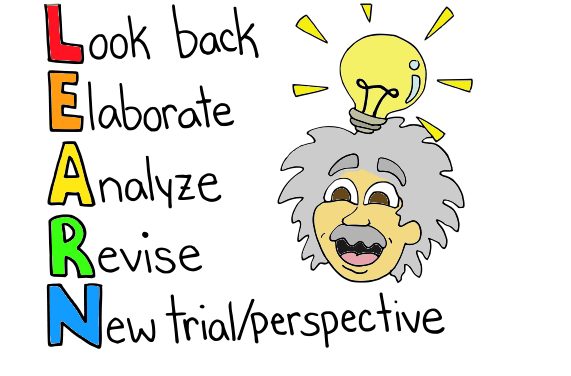

There are many approaches and frameworks to guide reflective writing as related to reflective practice in nursing. These approaches guide you to reflect on an experience, what happened, how you felt, what actions you took, what you learned, and how you might do things differently in the future (Mahon & O’Neill, 2020). One common framework called LEARN was developed by the College of Nurses of Ontario (1996). See Figure 4.4 .

Figure 4.4: Writing reflectively

Variations of this acronym have been taken up, but it essentially stands for:

Look back. Recall a situation that was meaningful to you in your practice.

Elaborate. Describe the situation from both an objective and subjective perspective (e.g., what did you see, hear? Who was involved and what interactions were observed? What did you think and feel?)

Analyze. Examine how and why the situation happened the way it did. Think about it in the context of your nursing courses and the literature.

Revise. Consider how and why your practice should remain the same and how it should be changed.

New trial/perspective. Think and move forward. What will you do differently when a similar situation arises?

More recently, reflective writing has been described in the context of narrative writing in which you engage in personal and professional storytelling. A narrative approach to reflective writing asks you to think about storied elements (e.g., characters, events, setting) of an experience: What happened? How did the situation begin? Who was involved? Where did it take place? What emotions were people feeling? How did the situation end? As you can see, these types of questions can easily be integrated into the LEARN framework too.

What to keep in mind?

You will be expected to engage in reflective writing throughout your nursing program. Sometimes you will be asked to use the LEARN framework or another approach. Here are some tips on good reflective writing:

- If possible, choose a topic or situation that is meaningful to you.

- Be vulnerable in your writing and share your thoughts and feelings (you don’t need to write about a sanitized version of yourself – it’s okay to ponder mistakes or areas for improvement).

- Description is important, but so is analysis so that you can gain new insights.

- Think critically about your experience and be open to new perspectives.

Student Tip

The growth of reflection

Graduates or senior-level students will tell you that reflective writing changes over the course of your program. As you advance, your forms of reflective writing will evolve from descriptive to more analytical. You will be expected to refer to the literature to explain your analysis and support your claims. You should also always engage in reflection in the context of the courses that you are taking. Some courses focus on the personal self; others focus on the professional self, as well as nursing in the community or on a broader societal level.

Activity: Check Your Understanding

Think about a healthcare event that you encountered or a health and illness experience of a friend or relative that is meaningful to you. In reflecting on this experience, how could you apply the LEARN format?

College of Nurses of Ontario (2019). Self-Assessment. Retrieved from: http://www.cno.org/en/myqa/self-assessment/

College of Nurses of Ontario (1996). Professional profile: A reflective portfolio for continuous learning. Toronto: CNO.

Mahon, P., & O’Neill, M. (2020). Through the looking glass: The rabbit hole of reflective practice. British Journal of Nursing , 29 (13), 777-783. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2020.29.13.777

Thinking deeply and critically about an experience.

Exploring and analyzing a clinical experience.

The Scholarship of Writing in Nursing Education: 1st Canadian Edition Copyright © 2019 by Jennifer Lapum; Oona St-Amant; Michelle Hughes; Andy Tan; Arina Bogdan; Frances Dimaranan; Rachel Frantzke; and Nada Savicevic is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

What is reflective writing and why is it important in nursing & other fields?

What is reflective writing?

Reflective writing is the physical act of writing your thoughts, feelings, perceptions, and interactions related to a specific event or situation. Reflective writing can help you learn from events in order to improve your knowledge and skill set as a nurse as it can build critical thinking and reasoning.

What are the benefits of reflective writing?

Reflective writing has many identified benefits:

- Allows you to engage in deeper, longer-lasting learning

- Opens a conversation between you and your instructor

- It helps you learn about concepts instead of just facts

- Self-reflection can help you identify your preconceived thoughts and feelings and allow you to dive deeper into understanding different cultures, values, and behaviors

What are the types of reflective writing?

Reflective writing can generally fit into three categories:

- Highly personal: In this type of reflective writing, the nurse takes the time to reflect on an experience from practice and does not incorporate any research or academics. It is purely all about you and your feelings regarding a situation.

- Mid-ground: Mid-ground reflective writing allows the nurse to reflect upon personal experiences within the context of the course itself such as readings, research, and lecture materials

- Highly academic: Highly academic reflective writing is when you reflect upon the readings, research, and lecture materials without any reference to personal experiences

How do I write reflectively?

Once you identify the type of reflective writing you are asked to complete, you can start the writing process. While there are multiple frameworks for reflective writing, here is a generic framework to help get you started:

- Description: Choose an event and describe what happened chronologically. What happened? Who was involved? Where did it take place? Why were you there? What part did you play? What part did others play?

- Assessment/analysis: This is the time to review the actions and steps taken during the event. What went well? What did not? What were certain actions taken? Were appropriate interventions done?

- Evaluation/Implications: Describe how this event impacted you. What was the outcome of the event? What did you learn from the event? What would you do differently next time?

Do you have any other resources about reflective writing in nursing?

- Reflective Writing: A User-Friendly Guide

- Understanding the Processes of Writing Papers Reflectively

Hamilton, S. (2016). Reflective writing: A user-friendly guide . British Journal of Nursing, 25 (16), 936-937. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=rzh&AN=118066871&site=eds-live&custid=s9076023

Kenninson, M. (2012). Developing reflective writing as effective pedagogy . Nursing Education Perspectives, 33 (5), 306-311. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=rzh&AN=107995069&site=eds-live&custid=s9076023

Regmi, K., & Naidoo, J. (2013). Understanding the processes of writing papers reflectively . Nurse Researcher, 20 (6), 33-39. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1406196680?accountid=40836

Taylor, D.B. (2013). Reflective writing . In S. Worsey (Ed.), Writing skills for nursing and midwifery students (pp. 170-178). https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=nlebk&AN=775782&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s9076023&ebv=EB&ppid=pp_170

- Last Updated Mar 04, 2022

- Views 11836

- Answered By

FAQ Actions

- Share on Facebook

Comments (0)

Hello! We're here to help! Please log in to ask your question.

Need an answer now? Search our FAQs !

How can I find my course textbook?

You can expect a prompt response, Monday through Friday, 8:00 AM-4:00 PM Central Time (by the next business day on weekends and holidays).

Questions may be answered by a Librarian, Learning Services Coordinator, Instructor, or Tutor.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.5: Reflective Writing

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 16518

- Lapum et al.

- Ryerson University (Daphne Cockwell School of Nursing) via Ryerson University Library

What it is?

Have you ever been asked to reflect on a text or an experience?

Reflective writing is used by different healthcare professions in various ways, but all reflective writing requires that you think deeply and critically about an experience or a text. At the centre of reflective writing is the “self” – including a deep analysis of you in relation to the topic. Reflective writing is a process that involves recalling an experience or an event, thinking and deliberating about it, and then writing about it.

You may be asked to engage in reflective writing related to an array of topics: the reading you are doing for a course, your experience working in a group, how you solved a problem, how you prepared for class or for an exam, a healthcare issue or a new theory. You will be expected to reflect on your clinical practice often throughout your nursing studies and for the rest of your nursing career to grow, learn, and demonstrate your continuing competence.

In nursing, reflective writing is part of what is called “ reflective practice. ” Early in your nursing program, you will become familiar with the College of Nurses of Ontario requirements for nurses to engage in reflective practice: this legislated professional expectation involves an intentional process of reflecting to explore and analyze a clinical experience so that you can “identify your strengths and areas for improvement” with the aim of strengthening your practice (College of Nurses of Ontario, 2019).

Figure 4.3: Reflective writing

How to do it?

Although there are many ways to reflect, one common framework called LEARN was developed by the College of Nurses of Ontario (1996). See Figure 4.4 .

Figure 4.4: Writing reflectively

Variations of this acronym have been taken up, but it essentially stands for:

- Look back. Recall a situation that was meaningful to you in your practice.

- Elaborate. Describe the situation from both an objective and subjective perspective (e.g., what did you see, hear? Who was involved and what interactions were observed? What did you think and feel?)

- Analyze. Examine how and why the situation happened the way it did. Think about it in the context of your nursing courses and the literature.

- Revise. Consider how and why your practice should remain the same and how it should be changed.

- New trial/perspective. Think and move forward. What will you do differently when a similar situation arises?

More recently, reflective writing has been described in the context of narrative writing in which you engage in personal and professional storytelling. A narrative approach to reflective writing asks you to think about storied elements (e.g., characters, events, setting) of an experience: What happened? How did the situation begin? Who was involved? Where did it take place? What emotions were people feeling? How did the situation end? As you can see, these types of questions can easily be integrated into the LEARN framework too.

What to keep in mind?

You will be expected to engage in reflective writing throughout your nursing program. Sometimes you will be asked to use the LEARN framework or another approach. Here are some tips on good reflective writing:

- If possible, choose a topic or situation that is meaningful to you.

- Be vulnerable in your writing and share your thoughts and feelings (you don’t need to write about a sanitized version of yourself – it’s okay to ponder mistakes or areas for improvement).

- Description is important, but so is analysis so that you can gain new insights.

- Think critically about your experience and be open to new perspectives.

Student Tip

The growth of reflection

Graduates or senior-level students will tell you that reflective writing changes over the course of your program. As you advance, your forms of reflective writing will evolve from descriptive to more analytical. You will be expected to refer to the literature to explain your analysis and support your claims. You should also always engage in reflection in the context of the courses that you are taking. Some courses focus on the personal self; others focus on the professional self, as well as nursing in the community or on a broader societal level.

Activity: Check Your Understanding

Think about a healthcare event that you encountered or a health and illness experience of a friend or relative that is meaningful to you. In reflecting on this experience, how could you apply the LEARN format?

The original version of this chapter contained H5P content. You may want to remove or replace this element.

College of Nurses of Ontario (2019). Self-Assessment. Retrieved from: www.cno.org/en/myqa/self-assessment/

College of Nurses of Ontario (1996). Professional profile: A reflective portfolio for continuous learning. Toronto: CNO.

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Beginner's Guide to Reflective Practice in Nursing

- Catherine Delves-Yates - University of East Anglia, UK

- Description

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

I have now received this text from SAGE. I would be placing this text on the reading list for MSc students to peruse as a starting point when considering reflection. A times, MSc students (who already possess a first degree) are not au-fait with reflection and its importance within nursing, Therefore, this text is a good start with this process and it gets students to consider what reflection entails and how reflection can be a learning tool in nursing.

Easy to read and well structured. makes no assumptions of previous knowledge or experience.

Preview this book

For instructors, select a purchasing option, related products.

- Cancer Nursing Practice

- Emergency Nurse

- Evidence-Based Nursing

- Learning Disability Practice

- Mental Health Practice

- Nurse Researcher

- Nursing Children and Young People

- Nursing Management

- Nursing Older People

- Nursing Standard

- Primary Health Care

- RCN Nursing Awards

- Nursing Live

- Nursing Careers and Job Fairs

- CPD webinars on-demand

- --> Advanced -->

- Clinical articles

- CPD articles

- CPD Quizzes

- Expert advice

- Clinical placements

- Study skills

- Clinical skills

- University life

- Person-centred care

- Career advice

- Revalidation

CPD Previous Next

Understanding reflective practice, jacqueline sian nicol lecturer, edinburgh napier university, edinburgh, scotland., isabel dosser lecturer, edinburgh napier university, edinburgh, scotland..

The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) requires that nurses and midwives use feedback as an opportunity for reflection and learning, to improve practice. The NMC revalidation process stipulates that practitioners provide examples of how they have achieved this. To reflect in a meaningful way, it is important to understand what is meant by reflection, the skills required, and how reflection can be undertaken successfully. Traditionally, reflection occurs after an event encountered in practice. The authors challenge this perception, suggesting that reflection should be undertaken before, during and after an event. This article provides practical guidance to help practitioners use reflective models to write reflective accounts. It also outlines how the reflective process can be used as a valuable learning tool in preparation for revalidation.

Nursing Standard . 30, 36, 34-42. doi: 10.7748/ns.30.36.34.s44

All articles are subject to external double-blind peer review and checked for plagiarism using automated software.

Received: 28 September 2015

Accepted: 09 January 2016

critical thinking - portfolio - professional development - reflection - reflection models - reflective account - reflective practice - revalidation - self-awareness

User not found

Want to read more?

Already have access log in, 3-month trial offer for £5.25/month.

- Unlimited access to all 10 RCNi Journals

- RCNi Learning featuring over 175 modules to easily earn CPD time

- NMC-compliant RCNi Revalidation Portfolio to stay on track with your progress

- Personalised newsletters tailored to your interests

- A customisable dashboard with over 200 topics

Alternatively, you can purchase access to this article for the next seven days. Buy now

Are you a student? Our student subscription has content especially for you. Find out more

04 May 2016 / Vol 30 issue 36

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DIGITAL EDITION

- LATEST ISSUE

- SIGN UP FOR E-ALERT

- WRITE FOR US

- PERMISSIONS

Share article: Understanding reflective practice

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience.

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Med Educ

Health professionals and students’ experiences of reflective writing in learning: A qualitative meta-synthesis

Giovanna artioli.

1 Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Viale Umberto I, 50, 42123 Reggio Emilia, Italy

Laura Deiana

2 Medical and Surgical Department, University of Parma, Parma, Italy

Francesco De Vincenzo

3 European University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Margherita Raucci

Giovanna amaducci, maria chiara bassi, silvia di leo, mark hayter.

4 Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Hull, Hull, UK

Luca Ghirotto

Associated data.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Reflective writing provides an opportunity for health professionals and students to learn from their mistakes, successes, anxieties, and worries that otherwise would remain disjointed and worthless. This systematic review addresses the following question: “What are the experiences of health professionals and students in applying reflective writing during their education and training?”

We performed a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Our search comprised six electronic databases: MedLine, Embase, Cinahl, PsycINFO, Eric, and Scopus. Our initial search produced 1237 titles, excluding duplicates that we removed. After title and abstract screening, 17 articles met the inclusion criteria. We identified descriptive themes and the conceptual elements explaining the health professionals’ and students’ experience using reflective writing during their academic and in-service training by performing a meta-synthesis.

We identified four main categories (and related sub-categories) through the meta-synthesis: reflection and reflexivity, accomplishing learning potential, building a philosophical and empathic approach, and identifying reflective writing feasibility. We placed the main categories into an interpretative model which explains the users’ experiences of reflective writing during their education and training. Reflective writing triggered reflection and reflexivity that allows, on the one hand, skills development, professional growth, and the ability to act on change; on the other hand, the acquisition of empathic attitudes and sensitivity towards one’s own and others’ emotions. Perceived barriers and impeding factors and facilitating ones, like timing and strategies for using reflective writing, were also identified.

Conclusions

The use of this learning methodology is crucial today because of the recognition of the increasing complexity of healthcare contexts requiring professionals to learn advanced skills beyond their clinical ones. Implementing reflective writing-based courses and training in university curricula and clinical contexts can benefit human and professional development.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-021-02831-4.

Education of healthcare professionals supportstheir transformation into becoming competent professionals [ 1 ] and improves their reasoning skills in clinical situations. In this context, reflective writing (RW) is encouraged by both universities, and healthcare training providersencourage reflective writing (RW) since its utility in helping health students and professionals nurture reflection [ 2 ], which is considered a core element of professionalism. Furthermore, the ability to reflect on one’s performance is now seen to be a crucial skill for personal and professional development [ 3 ]. Writing about experiences to develop learning and growth through reflection is called ‘reflective writing’ (RW). RW involves the process of reconsidering an experience, which is then analyzed in its various components [ 4 , 5 ]. The act of transforming thoughts into words may create new ideas: the recollection of the experience to allow a deeper understanding of it, modifying its original perception, and creating new insights [ 6 ]. RWis the focused and recurrent inspection of thoughts, feelings, and events emerging from practice as applied to healthcare practice [ 7 ].

Reflection may be intended as a form of mental processing or thinking used by learners to fulfill a purpose or achieve some anticipated outcome [ 2 ]. This definition recalls Boud and colleagues’ view of reflection as a purposive activity directed towards goals [ 8 ]. For those authors, reflection involves a three-stage process, including recollection of the experience, attending to own feelings, and re-evaluating the experience. This process can be facilitated by reflective practices, among which RW is one of the main tools [ 9 ].

Between reflection-on-action (leading to adjustments to future learning and actions) and reflection-in-action (where adjustments are made at the moment) [ 10 ], RW can be situated in the former. It involves theprofessional’s reflections and analysis of experiences in clinical practice [ 11 , 12 ]. Mainly,RWinvolves the recurrent introspection ofone’s thoughts, feelings, and events within a particular context [ 13 ]. Several studies highlight how RWinfluencespromoting critical thinking [ 14 ], self-consciousness [ 15 ], and favors the development of personal skills [ 16 ], communication and empathy skills [ 4 , 17 ], and self-knowledge [ 3 ]. Thanks to the writing process, individuals may analyze all the components of their experience and learn something new, giving new meanings [ 5 ]. Indeed, putting down thoughts into words enables the individual to reprocess the experience, build and empower new insights, new learnings, and new ways to conceive reality [ 6 , 18 – 20 ].

Furthermore, RW provides an opportunity to give concrete meaning to one’s inner processes, mistakes, successes, anxieties, and worries that otherwise would remain disjointed and worthless [ 21 , 22 ]. The reflective approach of RW allows oneself to enter the story, becoming aware of our professional path, with both an educational and therapeutic effect [ 23 ].

Reflection as practically sustained by RW commonly overlaps with the process of reflexivity. As noted elsewhere [ 24 ], reflection and reflexivity originate from different philosophical traditionsbut have shared similarities and meanings. In the context of this article, we adopt two different working definitions of reflection and reflexivity. Firstly, we draw from the work of Alexander [ 25 ]: who explains reflection as the deliberation, pondering, or rumination over ideas, circumstances, or experiences yet to be enacted, as well as those presently unfolding or already passed [ 25 ]. Reflexivity at a meta-cognitive level relates to finding strategies to challenge and questionpersonal attitudes, thought processes, values, assumptions, prejudices, and habitual actions to understand the relationships’ underpinning structure with experiences and events [ 26 ]. In other words, reflexivity can be defined as “the self-conscious co-ordination of the observed with existing cognitive structures of meaning” [ 27 ].

Given those definitions,a philosophical framework for helping health trainees and professionals conduct an exercise that can be helpful to them, their practice, and – ultimately – their patients can be identified. There is a growing body of qualitative literature on this topic – which is valuable – but the nature of qualitative research is that it creates transferrable and more generalizableknowledge cumulatively. As such, bodies of qualitative knowledge must besummarized and amalgamated to provide a sound understanding of the issues – to inform practice and generate the future qualitative research agenda. To date, this has not been done for the qualitative work on reflective writing: a gap in the knowledge base our synthesis study intends to address by highlighting what connects students and professionals while using RW.

This systematic review addresses the following question: “What are the experiences of health professionals and students in applyingRWduring their education and training?”

This systematic review and meta-synthesis followed the 4-step procedure outlined by Sandelowski and Barroso [ 28 , 29 ], foreseeing a comprehensive search, appraising reports of qualitative studies, classification of studies, synthesis of the findings. Systematic review and meta-synthesis referto the process of scientific inquiry aimed at systematically reviewing and formally integrating the findings in reports of completed qualitative studies [ 29 ].

The article selection processwas summarized as a PRISMA flowchart [ 30 ]; the search strategy was based on PICo (Population, phenomenon of Interest, and Context),and the study results are reported in agreement with Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) guidelines [ 31 ].

Selection criteria

Inclusion criteria for the meta-synthesis were:

- Primary qualitative studies published in peer-reviewed English journals.

- With health professionals or health studentsas participants.

- UsingRW in learning contexts (both pre-and in-service training).

- Mixed methods where the qualitative part can be separated.

- Articles should report the voice of participants (direct quotations).

Given the meta-synthesis indications, we excluded quantitative studies, non-primary research articles, meta-synthesis of qualitative studies, literature and systematic reviews, abstracts, unpublished reports, grey literature. In addition, we also excluded studies where participants were using RW in association with other learning tools and where the personal experience was not about using RW exclusively.

Data sources and searches

An experienced information specialist (MCB) performed the literature search on Medline, Embase, Cinahl, PsycInfo, Eric, and Scopus for research articles published from Jan 1st, 2008 to September 30th, 2019,to make sure we incorporated studies reflecting contemporary professional health care experience. Additional searchinginvolved reviewing the references or, and citations to, our included studies.

We filled an Excel file with all the titles and authors’ names. A filter for qualitative and mixed methods study was applied. Table 1 shows the general search strategy for all the databases based on PICo.

Search strategy for databases based on PICo

* truncation

Four reviewers (GAr, MR, GAm, LD) independently screened titles and abstracts of all studies, then checked full-text articles based on the selection criteria. We also searched the reference lists of the full-text articles selected for additional potentially relevant studies. Any conflict was solved through discussion with three external reviewers (LG, MCB,SDL, and MH).

Quality appraisal

We used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP): it provides ten simple guiding questions and examples to examine study validity, adequacy, and potential applicability of the results of qualitative studies. Guided by the work of Long and colleagues [ 32 ] and previously used in other meta-synthesis [ 33 ], we created 30 items from the 10 CASP questions on quality to ensure we could provide a detailed appraisal of the studies. FDV and LD independently assessed the quality of included studies with any conflicts solved by consulting a third reviewer (MCB and LG). Researchers scored primary studies weighingthe proposed items and ranking the quality of each included study [ 34 ] on high ( n > 20 items positively assessed), moderate (10 < n < 20), or low quality ( n < 10).

Analysis and synthesis

MCB created a data extraction table, GAr, GAm, and MRdescribed the included articles (Table 2 ). Quotations were extracted manually from the “results/findings” sections of the included studies by GAr, MCB, LDand inserted into adatabase. GAr, GAm, MR, and FDVperformed a thematic analysis of those sections, along with participants’ quotations. Then, they inductively derived sub-themes from the data, performing a first interpretative analysis of participants’ narratives (i.e., highlighting meanings participants interpreted about their experience). The sub-themes were compared and transferred across studies by adding the data into existing sub-themes or creating new sub-themes. Similar sub-themes were then grouped into themes, using taxonomic analysisto conceptually identify the sub-categories and the categories emerging from the participants’ narratives. This procedure allowed us to translate the themes identified from the original studies [ 28 ] into interpretative categories that could amalgamate and refine the experiences of health professionalsor health students on the use of RW [ 29 ]. The final categories are based on the consent of all the authors.

Summary of articles included in meta-synthesis (divided per groups: students and professionals)

Literature search and studies’ characteristics

A total of 1488 articles were retrieved. Duplicates ( n = 251) were removed. Then, articles ( n = 1237) were identified and reviewed by title and abstract. We excluded n = 1152 articles because they did not match the specified inclusion criteria, based on the title and abstract. Consequently, we assessed 85 full-text articles. Sixty-eight records did not meet the inclusion criteria. At the end of the selection process, 17 reportsof qualitative research were selected. Figure 1 illustrates the search process.

PRISMA flow diagram

Table Table2 2 shows the characteristics of the included studies. Eleven studies involved healthcare students (58%, including nurses, midwives, physiotherapists, doctors, dentists, and oral health students), and six (32%, including doctors, occupational and radiation therapists) were referred to health professionals. In thirteen studies, participants were trained on RW before using it: this information could not be retrieved from the remaining articles.

Five articles reported studies conducted in the US, three in Australia, two in Canada, and two in Israel. The other studies were carried out in Italy, UK, Korea, Taiwan, and Sweden.

Critical appraisal results

We critically evaluatedall 17 studies to highlight the methodological strengthsand weaknesses of the selected studies. No article was removed on a quality assessment basis. Results of the quality appraisal are reported in Table Table2 2 .

Meta-synthesis findings

Through the meta-synthesis, we identified four main categories (and related sub-categories): (i) reflection and reflexivity; (ii) accomplishing learning potential; (iii) building a philosophical and empathic approach; (iv) identifying reflective writing feasibility (for the complete dataset, please refer to supplemental material , where we have listed a selection of meaningful quotations of categories and sub-categories).

Given such categories, we developed an interpretative meta-synthesis model (Fig. 2 ) to illustrate the commonalities of the experience of using RW according to both students and professionals: RWas a vehicle for discovering reflection and allowing users to enter personal reflexivity to fulfillone’s learning potential, alongside the building of a philosophical and empathic approach. In their experience, reflection and reflexivity generate different skills and competencies: reflection matures skills such as professional skills and the ability to activate change and innovation. Reflexivity allows students and professionals to reach higher levels of competencyconcerning inner development and empathy reaching. Finally, from our analysis, participants, while recognizing the value of RW, also defined factors that could encourage or limit its use. Differences among participants’ groups are also outlined.

Meta-synthesis model: RW as experienced by health professionals and students

Reflection and reflexivity

Within this category, we collected the users’ narratives about the experience of applying RW and its disclosing capacity. By using RW, participants confronted themselves with both reflection and reflexivity. This category includes two sub-categories we named: discovering reflection and entering personal reflexivity.

Discovering reflection

The sub-category shows that experiencingRW deepened their reflection on experiences, practice, and profession. Thanks to RW, professionals, and students could explore previously unexplored topics and learn more about themselves.

“ Writing initiated me to think about my experiences … ” (professional) [ 46 ]. “ I think it’s good for physicians to reflect on what we’re doing ” (professional) [ 50 ]

“ Helped (me) reflect on positive aspects ” (student) [ 40 ]. “ I don’t usually think too much about what happens to me, but through critical reflective journaling, I was able to think carefully about things happening around me. This activity helped me to look into my mind ” (student) [ 44 ]

This sub-category explains transversal meanings coming from uniformly professionals and students.

Entering personal reflexivity

This sub-category includes data about RW enabling users’reflexivity. In this context, RW was considered training for reflexivity as it enabled participants to question themselves more often [ 48 ], reflect on their experiences [ 35 ], attitudes, actions [ 38 , 45 ], and also reconsider their actions and identify their strengths and weaknesses [ 40 , 44 ].

“ The questions in this study do make me stop and think about things – how I feel about what I’m doing in residency ”(professional) [ 46 ]. “ Helped me ID (identify) my strengths and weaknesses ” (student) [ 40 ] RW also helped eradicate the background noise that my mind does not yet know how to filter out [ 51 ] .

Interesting to note that this sub-category is more present in students’ narratives. While professionals referred to self-reflection practices (probably already acquired in other contexts), students often reported how RW helped them discover reflexivity.

Accomplishing learning potential

Our analysis showed how users RW used the technique to “Accomplish learning potential.”

According to the studies’ participants, RWcan enable a learning performancethat would be difficult to reach otherwise. In this context, participants addressed RW as a tool for“accomplishing learning potential.”Within this category, three sub-categories were highlighted: the improvement of skills, personal and professional growth, and assisting the change and development process.

Improvement of skills

Participants agreed that the development of skills and abilities through RWwas aimed at their clinical skills and –in relevant areas such as question asking – encouraged reflection and research [ 35 , 46 ]. Communication skills were also enhanced, as were their relationship with patients, family,colleagues, and friends [ 35 , 38 , 46 ].

Participants said:

“ Through reflective journal writing, my attitude towards learning has changed. I have been encouraged to be a proactive learner. (...) I have been able to identify necessary places for improvement and through research, question asking, goal-setting (...). I have improved my skills in relevant areas” (student) [ 35 ]. “I feel that it [participation in the study] has been a positive experience by motivating me to improve on my clinical, communication skills, and also my relationships with colleagues, patients, family, and friends ” (professional) [ 46 ]

Participants also reported that,in their experience, RWprovided an opportunity to assess and improve themselves and to enhance their self-confidence [ 38 , 40 ]. Cognitive skills, includinggaining more profoundknowledge and problem-solving, along withtime-management [ 35 , 40 , 46 , 49 ], were also enhanced: RW,therefore,represented a learning mode [ 45 ].

“ Without reflection, I absolutely believe these skills would be more unattainable for me ”(student) [ 35 ]

This sub-category applies more to students’ narratives. Health students mentioned the tools helping them most to develop their skills. Professionals focused principally on what RWcould improve (communication skills or organizational skills).

Personal and professional growth

Participantsidentifiedthat RWhad promoted personal [ 51 ] and professional growth [ 35 , 46 ]. RW meant for participants:an ameliorated attitude towards work [ 46 ]; a development path for one’s job potential [ 38 ]; an enhancement of their introspective knowledge [ 51 ]; an enrichment of their expressive capability [ 38 ];an improvement of their interpersonal relationships with patients and colleagues [ 50 ] and developed their use of critical and reflective thinking [ 38 ].

“ Reflecting introduces a new aspect to clinic that focuses on the individual’s learning experience ” (student) [ 35 ]. “I think that it does change the way that you think about the practice of medicine and your own personal tendencies and your interactions with your patients and colleagues. And I think it can be a really powerful driver of culture change ” (professional) [ 50 ]

This sub-category is more represented among students than professionals. Students are ‘surprised’ at how important RW was to their learning. Professionals still recognized how RW was an essential driver of change for their clinic activities.

Assisting the change and development process

We labeledthe third sub-category“assisting the change and development process.”The changeinvolvedintroducing modifications tothe way of working [ 48 ], assessing what needed to be changed to achieve a work-life balance [ 51 ], understanding elements that did not allow change, and how to act on them in the future, and also considering new and important issues [ 46 ], further information [ 51 ] and new ways of thinking. This sub-category equally explained the meaning given to RW by students and professionals.

“ I think writing answer to some of these questions has allowed me to reflect back on the year and think about specific important topics that I might not have thought about again.” (professional) [ 46 ]. (Reflective journaling encouraged) “Assessing and focusing on the changes that need to be done to achieve the balance in my life and being able to integrate that with my family and in my work as a nurse.” (Student 16/RJ2) [ 51 ]

However, thischange process could not be possible without witnessing change and becoming aware of it [ 38 , 46 ]. This allowedparticipants to ‘see one’slearning history and path of growth,‘have a picture of the problem, handle things differently, and broadening their vision of the problem [ 48 ].

Building a philosophical and empathic approach

The “Reflection and reflexivity” category is closely aligned with the “Building a philosophical and empathic approach” category. Participants defined RW as a means for nurturing an intimate and profound level of learning, i.e., a philosophical and empathic approach towards real-life professional issues. The third category consists of three sub-categories: the ability to find benefits in negativity/adversity, assuming an empathetic attitude, and the awareness of things, experiences,emotions.

Finding benefits in negativity/adversity

According to participants, RWexerted a therapeutic effect by encouraging professionals and students to focus on the present (43)strictly. It seemed that RWeventually reduced their emotional stress [ 44 , 51 ]. Likewise,in the contextofnegative experiences [ 49 ], its practice acted as a catharsis [ 46 ] that could even allow them tolook back at those experiencesafresh – enabling a change in perspective [ 39 ].

“While writing the journal entry, I felt like I was unloading something from inside myself and being set free. This process made me feel better ” (student) [ 44 ]. “It is always good to pause to reflect on my experiences. The most cathartic question was a few months back when I got to describe my really bad experience.” (professional) [ 46 ] “Very therapeutic. I wrote on a bad experience, but at the end, we were laughing at it.” (professional) [ 49 ]

This specific approach allowed the practitioner/trainee to improve their self-care and focus on work objectives [ 51 ]:

“Self-reflection and reflective journaling promote self-understanding and is another part of self-care.” (Student 5/RJ3) [ 51 ]

Even if more emerging from students’ voices, professionals appeared genuinely amazed at how learning can be generated out of negativity.

Assuming an empathetic attitude

Study participants stressed the fact that RWhelped them develop empathetic attitudes. It seems that RWemphasized the importance of sensitivity and empathy by trying ‘to be in someone else’sshoes,’ especially that of patients or colleagues [ 36 , 37 , 44 ].

“How reflecting on patient encounters through field notes allowed her to “take a walk in someone else’s shoes ” (student) [ 36 ]. “It helps you see the humanity... ” (professional) [ 50 ]

This approach also applied in contexts outside of work and helped the practitioner take off his/her‘white coat’ and understand that before being a professional,he/shewas a person and a human being [ 36 , 37 , 46 , 50 ].

“ Which has made me more open to other’s ideas and thoughts ” (professional) [ 46 ]

As previously mentioned, according to the participants’ statements, awareness was the cornerstone to effective personal and professional growth [ 40 , 51 ].

This sub-category is equivalently present among the participants’ groups. Nonetheless, different meaningscould also be highlighted. Students appreciated RWby stressing its value of allowing them to enter deeply ‘into the other’ inner world (mainly patients). Professionals claimed they could recognize the profession’s human and relational aspects, whichcould also be helpful for their extra-professional relationships (family members, friends).

Awareness of things, experiences, emotions

Impartially balanced among professionals and students, awareness was cited in terms of ‘how things have affected me rather than simply continuing to work in a robotic manner’ [ 46 ], the awareness of who one was and who one has become thanks to the process of change [ 51 ]. This professional and relational awareness made it possible to think clearly about one’s practice and the health resources present in the context of belonging [ 50 ].

“Just being aware of what I know now and what I’ll know by the end of the semester … is a great way to learn who I am and what I can change about me for the better.” (Student 9/RJ1) [ 51 ]

The process of awareness that was facilitated by how their RW allowedthem to transform shapeless and straightforward ideasinto words and givethem a specific value and emotional charge [ 36 , 47 , 51 ]: it wasan authentic opportunity to turn emotions and feelings into something tangible –a journey of discovery and personal acceptance [ 43 ].

“ After two years or so, when you look back, it’s like, oh,that’s how I was feeling at the time, and right now, I feel differently. There is also this level of satisfaction. Like you have matured out of this thinking ” (professional) [ 47 ]

Identifying RW feasibility

The fourth category consists of three sub-categories: perceived barriers/impeding factors, facilitating factors, and when and how to use RW. Students and healthcare professionals who had the experience of practicing the RW in their work identified both limitations and facilitating factors and indications about when and how to use RW.

Perceived barriers/impeding factors

Some study participants (almost entirely students) identified several barriers to their activity. Some students could not see the benefits and thought RW was a waste of time [ 35 , 38 , 51 ]. However, others, who did see the potential benefits still felt that they lacked the time needed to devote to RW [ 42 ] or, sufficient mental space to report and describe a work situation, an excessive similarity of this activity to the regular working practice and, consequently, a lack ofmotivation to write [ 47 , 51 ]. In addition, some described the strainthey felt in writing down personal/professional experiences [ 47 ]. A lack of privacy was another problem, both for the concern about sharing the reflection and for the respect of confidentialityin writing itself [ 51 ]. Taken together,it appeared that some study participants did not recognizeRW as an effective means of help [ 39 , 50 ]. Althoughrealizing the potential of RW,others felt that their tutors did not provide noticeably clearexplanations of the aim of RW– which they would have found useful and motivating [ 45 ].

“ To be honest, not a great deal ( … ) it wasn’t really some revelation ” (professional) [ 50 ]. “ I got a hard time referring it [my experience] to citations … I could have sat and cried yesterday when I did my essay … when I actually read it [my essay] I thought, oh I don’t know what it means, myself ” (Female 2 - student) [ 42 ]

Facilitating factors

This sub-category was exclusively interpreted from students’ narratives. They valued the perspectives to use RWin their practice seeing it as a valuable tool to be applied throughout their career [ 35 , 45 ],with many students reporting that they would continue with this technique [ 38 ]. Studentssaw RW as a valuable means of staying focused on their own goals and needs [ 40 , 51 ]. They remarked that it helped them reduce stress, gain clarity in one’s life and practice [ 41 ], and spiritually connect with themselves [ 45 , 51 ]. Furthermore, RW enabled studentsto discover more information about their health and well-being, ‘it also helped me tie in ideas and beliefs from different sources and relate it to my own’ [ 51 ]. RWhelped maintain awareness and recall the medical being/human being dichotomy [ 37 ]. It remindedstudentsof the difference between studying literature and refining manual skills and the ability to learn from experience and mistakes [ 35 ].

“ During the interview, I felt an element of being more like a ‘normal person’ having a ‘normal conversation’ with another human being. This was a strange realization because it reminded me of the dichotomy that physicians may experience, being doctor versus human ” (student) [ 37 ]

When and how to use RW

Health professionals (a few) and many students finally mentioned the time considered most appropriate to use RW, underlining its usefulness primarilywas during hardship rather than daily practice [ 47 ].Moreover,RWshould not be forced onto someone in any given moment but instead left to individual choice based on one’s spirit of the moment [ 40 , 46 ].

“. .. like if you had a patient die; that would be the only time you might write it down ” (professional) [ 47 ]

Otherparticipantsconsidered instructions on RW to be too forceful and notapplicable to their own experience of reflection [ 40 ]. ‘Reflection wasn’t just signing on the line.’ It allowed constructive feedback for the trainee or the professional. Constructive feedback could be positive or negative, but it was a powerful tool for thinking and examining things [ 45 ].

In this meta-synthesis of qualitative studies, we have interpreted the experiences of health professionals and students who used RWduring their education and training. Given the number of studies included, RW users’ experience was predominately investigated in students. This result, although not surprising, raises the question of whether RW in professional training is being used. RW is not used in professional training as often as it is in the academic training of healthcare students.

As to this review’s aim, we could highlight continuities and differences from study participants’ narratives. Our findings offer a conceptualization of usingRW in health care settings. According to the experience of both students (from different disciplines) and health professionals, RW allows its exponents to discover and practice reflectionas a form of cognitive processing [ 2 ] and enablethem to develop a better understanding of their lived situation. We also interpreted that RW allows users to make a ‘reflexive journey’ that involves them practicing meta-cognitive skills to challengetheir attitudes, pre-assumptions, prejudices, and habitual actions [ 24 , 26 ]. This was particularly true for students: “entering personal reflexivity” appears to be newer for them than for the professionals who are likely to acquire reflexivity during academic training. Students seemed more focused on tools than RW-related results. This consideration makes us affirm that reflective capacity is in progress for them.

Challenging pre-assumptions and entering reflexivityenabledRWusers to realize how RW may develop their learning potential to improve skills and personal/professional growth. Skills to be enhanced are quoted mainly by students. Conversely, professionals could comprehend the final purpose of learning, achievable through RW, in terms of communication or organizational abilities. Professionals interpreted skills from RW as abilities to apply in the clinical activities to find new solutions to problems.

The category “Accomplishing learning potential”confirms what many authors highlight: putting thoughts into words not only permits a deeper understanding of events [ 6 ], enhances professionalism [ 52 ] but also improves personal [ 16 ], communication, and empathy skills [ 4 , 17 ]. In this context, RW fulfills its mandate by letting human sciences [ 53 ] and evidence-based health disciplines affect clinical practice. As noted [ 54 ], students and health professionals’RW training allowed integrating scientific knowledge with behavioral and sociological sciences to supporttheir learning [ 55 ].

Users understood that RWcould be a powerful means of developing empathy and developing their philosophy of care: this consideration is in line with a recent study from Ng and colleagues [ 24 ]. Additionally, some authors [ 4 , 17 ] stressed these empathetic skills and “humanistic”competencies as essential to care for patients effectively [ 56 ]. Professionals were amazed how negativity could generate learning through RW. On the other hand, by recognizingand writing experienced negative situations, students could free themselves from feelings impeding empathy.

By employing RW, users reported factors that could encourage or limit its use. These findings further illustrate that RW is not always a tool that is easy to use without adequate training [ 57 ]. Almost exclusively, students reported hindering factors (limited time, difficulty in writing and understanding assignments, privacy issues, feeling bored or forced). As to professionals, few describedRW as a very stressful activity. Although students could identify impeding factors, they also recognized many positive ones. For professionals, RW was not to be used every day but in ‘extreme’ situations, requiring reflection and reflexivity to be applied. In general, enhancing motivation to write reflectively [ 58 ] should be the first goal of any training to make the process acceptable and profitable for trainees. If this first stage is not accomplished, it will reduce RW’sapparent professional and personal effectiveness among health professionals and students substantially.

Strengths, limitations, and research relaunches

This review may enrich our knowledge about providing RW as an educative tool for health students and professionals. However, the findings must be applied,taking into account some limitations. We focused our attention only on recent, primary, peer-reviewed studies within the time and publication limits. Qualitative studies often are available as grey literature: considering it may result in a different interpretation of students’ and professionals’ experience in using RW. Therefore, our conceptualization should be read bearing in mind a publication bias and the need to expand the literature search to other sources. Besides limiting the risk of missing published qualitative studies, we reviewed the reference listsof included studies for additional items. Our meta-synthesis is coherent to the interpretation of the included studies’ findings.

At least two reviewers have conducted each step of this systematic review. We purposely did not exclude studies based on a quality assessment to maintain a robust qualitative study sample size and valuable insights.

During analysis, all possible interpretations were screened by authors, and an agreement was reached. Nonetheless, we did not cover all the possible ways to interpret the voices of students and professionals.

Since RW is not used in professional training as often as it is in the academic training of healthcare students, a research relaunch could be investigatingwhether and to what extent RW is being used in in-service training programs. Moreover, the studies included in this review were conducted within Western countries. Students’ and professionals’ perspectives from Africa and Asia are underrepresented within the qualitative literature about experiences of using RW. Therefore, geographicalgeneralizations from the present meta-synthesis should be avoided, and our paper reveals the necessity for RW research in other cultures and settings. Nonetheless, authors of primary studies have paid little attention to cultural and regionaldiversity. Therefore, we recommend furtherinvestigations exploring the differences between cultural backgrounds and howRW is recognized within training programs in different countries. Finally, additional qualitative and quantitative research is required to deepen our understanding of RW’s clinical and psycho-social outcomes in high complexity health practice contexts.

Our analysis confirms the crucial role of RW in fostering reasoning skills [ 59 ] and awareness in clinical situations. While its utility in helping health students and professionals to nurture reflection [ 2 ] has been widely theorized, this meta-synthesis provide empirical evidence to support and illustrate this theoretical viewpoint. Finally, we argue that RWis even more critical given the increasing complexity of modern healthcare, requiringprofessionals to develop advanced skills beyond their clinical ones.

Practical implications

Two important implications can be highlighted:

- (i) students and professionals can recognize the potential of RW in learning advanced professional skills. ImplementingRW in academic training as well as continuing professional education is desirable.

- (ii) Despite recognizing the effectiveness of RW in healthcare learning, students and professionals may face difficulties in writing reflectively. Trainers should acknowledge and address this.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Silvia Tanzi for her insightful feedback about this work and Manuella Walker for assisting in the final editing of the paper.

Abbreviations

Authors’ contributions.

GArwas responsible for the original concept. MCB performed the literature search on databases. MCB, GAr, GAm, LD, MR were responsible of data curation. GAr, MR, GAm, and LD screened titles and abstracts of all studies. LG, MCB, SDL, and MH served as external auditors. FDV and LD assessed the quality of included studies. MCB and LG gave a third opinion in case of disagreement. GAr, GAm, MR, and FDV derived sub-categories from the data. GAr, LG, MH drafted the first version of the manuscript. FDV, LD composed tables, and figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

38 Reflective Writing

What it is.

Have you ever been asked to reflect on a text or an experience?

Reflective writing is used by different healthcare professions in various ways, but all reflective writing requires that you think deeply and critically about an experience or a text. At the centre of reflective writing is the “self” – including a deep analysis of you in relation to the topic. Reflective writing is a process that involves recalling an experience or an event, thinking and deliberating about it, and then writing about it.

You may be asked to engage in reflective writing related to an array of topics: the reading you are doing for a course, your experience working in a group, how you solved a problem, how you prepared for class or for an exam, a healthcare issue or a new theory. You will be expected to reflect on your clinical practice often throughout your nursing studies and for the rest of your nursing career to grow, learn, and demonstrate your continuing competence.

In nursing, reflective writing is part of what is called “ reflective practice . ” Early in your nursing program, you will become familiar with the College of Nurses of Ontario requirements for nurses to engage in reflective practice: this legislated professional expectation involves an intentional process of reflecting to explore and analyze a clinical experience so that you can “identify your strengths and areas for improvement” with the aim of strengthening your practice (College of Nurses of Ontario, 2019).

Figure 4.3: Reflective writing

How to do it?

Although there are many ways to reflect, one common framework called LEARN was developed by the College of Nurses of Ontario (1996). See Figure 4.4 .

Figure 4.4: Writing reflectively

Variations of this acronym have been taken up, but it essentially stands for:

Look back. Recall a situation that was meaningful to you in your practice.

Elaborate. Describe the situation from both an objective and subjective perspective (e.g., what did you see, hear? Who was involved and what interactions were observed? What did you think and feel?)

Analyze. Examine how and why the situation happened the way it did. Think about it in the context of your nursing courses and the literature.

Revise. Consider how and why your practice should remain the same and how it should be changed.

New trial/perspective. Think and move forward. What will you do differently when a similar situation arises?

More recently, reflective writing has been described in the context of narrative writing in which you engage in personal and professional storytelling. A narrative approach to reflective writing asks you to think about storied elements (e.g., characters, events, setting) of an experience: What happened? How did the situation begin? Who was involved? Where did it take place? What emotions were people feeling? How did the situation end? As you can see, these types of questions can easily be integrated into the LEARN framework too.

What to keep in mind?

You will be expected to engage in reflective writing throughout your nursing program. Sometimes you will be asked to use the LEARN framework or another approach. Here are some tips on good reflective writing:

- If possible, choose a topic or situation that is meaningful to you.

- Be vulnerable in your writing and share your thoughts and feelings (you don’t need to write about a sanitized version of yourself – it’s okay to ponder mistakes or areas for improvement).

- Description is important, but so is analysis so that you can gain new insights.

- Think critically about your experience and be open to new perspectives.

Student Tip

The growth of reflection

Graduates or senior-level students will tell you that reflective writing changes over the course of your program. As you advance, your forms of reflective writing will evolve from descriptive to more analytical. You will be expected to refer to the literature to explain your analysis and support your claims. You should also always engage in reflection in the context of the courses that you are taking. Some courses focus on the personal self; others focus on the professional self, as well as nursing in the community or on a broader societal level.

Activity: Check Your Understanding

Think about a healthcare event that you encountered or a health and illness experience of a friend or relative that is meaningful to you. In reflecting on this experience, how could you apply the LEARN format?

College of Nurses of Ontario (2019). Self-Assessment. Retrieved from: http://www.cno.org/en/myqa/self-assessment/

College of Nurses of Ontario (1996). Professional profile: A reflective portfolio for continuous learning. Toronto: CNO.

Thinking deeply and critically about an experience.

Exploring and analyzing a clinical experience.

The Scholarship of Writing in Nursing Education: 1st Canadian Edition Copyright © 2019 by Jennifer Lapum; Oona St-Amant; Michelle Hughes; Andy Tan; Arina Bogdan; Frances Dimaranan; Rachel Frantzke; and Nada Savicevic is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Reflective writing and nursing education

Affiliation.

- 1 Breast Imaging of Oklahoma, Edmond, Oklahoma, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 15719711

- DOI: 10.3928/01484834-20050201-03

Reflective writing is a valued tool for teaching nursing students and for documentation, support, and generation of nursing knowledge among experienced nurses. Expressive or reflective writing is becoming widely accepted in both professional and lay publications as a mechanism for coping with critical incidents. This article explores reflective writing as a tool for nursing education.

Publication types

- Education, Nursing*

- Cambridge Libraries

Study Skills

Reflective practice toolkit, introduction.

- What is reflective practice?

- Everyday reflection

- Models of reflection

- Barriers to reflection

- Free writing

- Reflective writing exercise

- Bibliography

Many people worry that they will be unable to write reflectively but chances are that you do it more than you think! It's a common task during both work and study from appraisal and planning documents to recording observations at the end of a module. The following pages will guide you through some simple techniques for reflective writing as well as how to avoid some of the most common pitfalls.

What is reflective writing?

Writing reflectively involves critically analysing an experience, recording how it has impacted you and what you plan to do with your new knowledge. It can help you to reflect on a deeper level as the act of getting something down on paper often helps people to think an experience through.

The key to reflective writing is to be analytical rather than descriptive. Always ask why rather than just describing what happened during an experience.

Remember...

Reflective writing is...

- Written in the first person

- Free flowing

- A tool to challenge assumptions

- A time investment

Reflective writing isn't...

- Written in the third person

- Descriptive

- What you think you should write

- A tool to ignore assumptions

- A waste of time

Adapted from The Reflective Practice Guide: an Interdisciplinary Approach / Barbara Bassot.

You can learn more about reflective writing in this handy video from Hull University:

Created by SkillsTeamHullUni

- Hull reflective writing video transcript (Word)

- Hull reflective writing video transcript (PDF)

Where might you use reflective writing?

You can use reflective writing in many aspects of your work, study and even everyday life. The activities below all contain some aspect of reflective writing and are common to many people:

1. Job applications

Both preparing for and writing job applications contain elements of reflective writing. You need to think about the experience that makes you suitable for a role and this means reflection on the skills you have developed and how they might relate to the specification. When writing your application you need to expand on what you have done and explain what you have learnt and why this matters - key elements of reflective writing.

2. Appraisals

In a similar way, undertaking an appraisal is a good time to reflect back on a certain period of time in post. You might be asked to record what went well and why as well as identifying areas for improvement.

3. Written feedback

If you have made a purchase recently you are likely to have received a request for feedback. When you leave a review of a product or service online then you need to think about the pros and cons. You may also have gone into detail about why the product was so good or the service was so bad so other people know how to judge it in the future.

4. Blogging

Blogs are a place to offer your own opinion and can be a really good place to do some reflective writing. Blogger often take a view on something and use their site as a way to share it with the world. They will often talk about the reasons why they like/dislike something - classic reflective writing.

5. During the research process

When researchers are working on a project they will often think about they way they are working and how it could be improved as well as considering different approaches to achieve their research goal. They will often record this in some way such as in a lab book and this questioning approach is a form of reflective writing.

6. In academic writing

Many students will be asked to include some form of reflection in an academic assignment, for example when relating a topic to their real life circumstances. They are also often asked to think about their opinion on or reactions to texts and other research and write about this in their own work.

Think about ... When you reflect

Think about all of the activities you do on a daily basis. Do any of these contain elements of reflective writing? Make a list of all the times you have written something reflective over the last month - it will be longer than you think!

Reflective terminology

A common mistake people make when writing reflectively is to focus too much on describing their experience. Think about some of the phrases below and try to use them when writing reflectively to help you avoid this problem:

- The most important thing was...

- At the time I felt...

- This was likely due to...

- After thinking about it...

- I learned that...

- I need to know more about...

- Later I realised...

- This was because...

- This was like...

- I wonder what would happen if...

- I'm still unsure about...

- My next steps are...

Always try and write in the first person when writing reflectively. This will help you to focus on your thoughts/feelings/experiences rather than just a description of the experience.

Using reflective writing in your academic work

Many courses will also expect you to reflect on your own learning as you progress through a particular programme. You may be asked to keep some type of reflective journal or diary. Depending on the needs of your course this may or may not be assessed but if you are using one it's important to write reflectively. This can help you to look back and see how your thinking has evolved over time - something useful for job applications in the future. Students at all levels may also be asked to reflect on the work of others, either as part of a group project or through peer review of their work. This requires a slightly different approach to reflection as you are not focused on your own work but again this is a useful skill to develop for the workplace.

You can see some useful examples of reflective writing in academia from Monash University , UNSW (the University of New South Wales) and Sage . Several of these examples also include feedback from tutors which you can use to inform your own work.

Laptop/computer/broswer/research by StockSnap via Pixabay licenced under CC0.

Now that you have a better idea of what reflective writing is and how it can be used it's time to practice some techniques.

This page has given you an understanding of what reflective writing is and where it can be used in both work and study. Now that you have a better idea of how reflective writing works the next two pages will guide you through some activities you can use to get started.

- << Previous: Barriers to reflection

- Next: Free writing >>

- Last Updated: Jun 21, 2023 3:24 PM

- URL: https://libguides.cam.ac.uk/reflectivepracticetoolkit

© Cambridge University Libraries | Accessibility | Privacy policy | Log into LibApps

- Latest hearings

- Written reflective accounts

Last Updated 26/05/2021

In this guide

Requirement, meeting the requirement, resources and templates.