CIPPET Study Support: Writing at level 7

- University jargon-buster

- 2. Library resources

- 3. Literature searching

- University policy and penalties

- How to avoid plagiarism

- Using EndNote

- Developing your ideas and argument

- Structuring your work and paragraphing

- Writing at level 7

- Writing at level 6

- Reflective models and language

- 8. Understanding feedback

- 9. Preparing for exams and OSCEs

- 10. Presentations

Introduction

When at studying level 7 ( Masters Level ), your academic writing must reflect the level of critical analysis, synthesis and application to practice commensurate with this level of study.

Studying at level 7 means developing your studying practices from those suited to being an independent learner to those suited to being an independent practitioner . You will be working at a more complex and sophisticated level, with a need for broader and more independently sourced resources. You will need not only to evaluate what other people have found but also to put your own knowledge and research into context. You will be expected to be meticulous and professional and show higher standards of scholarship. The advice on this page aims to explain some of the differences between undergraduate and Masters level study.

The full marking criteria for taught postgraduate study can be found at the link below, the information in this section of the guide interprets this information to the context in which you are doing your studies.

- Assessment handbook See the section on Marking. In particular Annex 2 of this section for detailed marking and assessment criteria for postgraduate work.

Tips for writing coursework at Masters level

Guidance on the requirements for assessments are included in the individual module handbooks. Some overarching principles will apply across all the assessments for all practitioners:

- Consider how you can analyse what you are writing to critique your role, the evidence and/or the outcome to show self-awareness of the implications to your practice

- Avoid simple descriptions and presentation of ideas; try questioning each step in the process, and then use these questions to challenge your practice

- When analysing situations ensure you consider the opinions of others, either through your workplace-based learning communication and/or the available evidence to produce an outcome i.e. an argument for what you perceive happened/should happen

- Consider the accuracy, relevance, validity and contribution of evidence i.e. critically appraise the evidence

- Ensure you bring in reflective elements to your writing, especially in your reflective accounts, remembering these sections should usually be written in the first person

- When writing reflectively consider how your history/experiences have shaped your career and professional values i.e. how have you been influenced by the circumstances you are describing

- Think about how you can show critical awareness of current problems and/or new insights in professional practice

Key concepts of level 7 writing

Achievement of level 7 study includes:

- ability to deal with complex problems, integrating theory to professional practice

- make sound judgements and communicating your conclusions clearly

- demonstrating self-direction in problem-solving

- acting autonomously, using own initiative and taking personal responsibility for professional practice

- critical awareness of professional practice, including self-reflection

A focused approach to your evidence

Not only are your assignments longer, but you are also expected to refer to a wider range of reading; it takes practice to integrate more sources and refer to them skillfully in your writing. You may find that even with a higher word count it is difficult to fit all you want to say in. Itis important to make every source work for you in backing up your points, and not waste words in describing unnecessary parts of the source.

You do not have to refer to each piece of evidence in the same depth. Sometimes you need to show that you understand the wider context of the issue, and a short summary of the key issue and key researchers is all that is needed.

For example:

A significant amount of reading and in-depth understanding of the field is demonstrated in those sentences above. The summary maps out the state of current research and the positions taken by the key researchers.

Sometimes you need to go into greater depth and refer to some sources in more detail in order to interrogate the methods and standpoints expressed by these researchers. For example:

Even in this more analytical piece of writing, only the relevant points of the study and the theory are mentioned briefly - but you need a confident and thorough understanding to refer to them so concisely.

- Academic Phrasebank Use this site for examples of linking phrases and ways to refer to sources.

Accuracy and awareness of complexity

If English is not your first language, there is more specialised support and advice available: see the International Study and Language Institute website for more details (link below).

At level 7 you cannot get away with writing about something that you only vaguely understand, or squeezing in a theory in the hope it will gain extra marks - your markers will be able to tell, and this does not demonstrate the accuracy or professionalism of a researcher.

Imagine you write the sentence: "Freudian psychoanalysis demonstrates how our personalities are developed from our childhood experiences."

At level 7, the word 'demonstrates' becomes very loaded and potentially inaccurate. This is because you are expected to interrogate the assumptions, boundaries, and way in which knowledge is constructed in your subject. With this in mind, the sentence above raises a lot of contextual questions: To what extent could Freud's theory of psychoanalysis really be said to 'demonstrate' the origins of our personalities? What part of Freud's many theories are you referring to when you write 'psychoanalysis'? What about the developments in psychoanalysis that have happened since Freud, and the many arguments against his theories? Your writing needs to take these questions into account, and at least be aware of them, even if you don't address all of them.

Do not just stop at discussing the pros and cons of a debate; academics rarely agree on interpretations of theories or ideas, so academic knowledge is more like a complex network of views than two clear sides.

- International Study and Language Institute Courses and resources to support the learning of English as a second language.

- << Previous: Structuring your work and paragraphing

- Next: Writing at level 6 >>

- Last Updated: Mar 13, 2024 3:53 PM

- URL: https://libguides.reading.ac.uk/cippet

Academic Phrasebank

- GENERAL LANGUAGE FUNCTIONS

- Being cautious

- Being critical

- Classifying and listing

- Compare and contrast

- Defining terms

- Describing trends

- Describing quantities

- Explaining causality

- Giving examples

- Signalling transition

- Writing about the past

The Academic Phrasebank is a general resource for academic writers. It aims to provide you with examples of some of the phraseological ‘nuts and bolts’ of writing organised according to the main sections of a research paper or dissertation (see the top menu ). Other phrases are listed under the more general communicative functions of academic writing (see the menu on the left). The resource should be particularly useful for writers who need to report their research work. The phrases, and the headings under which they are listed, can be used simply to assist you in thinking about the content and organisation of your own writing, or the phrases can be incorporated into your writing where this is appropriate. In most cases, a certain amount of creativity and adaptation will be necessary when a phrase is used. The items in the Academic Phrasebank are mostly content neutral and generic in nature; in using them, therefore, you are not stealing other people’s ideas and this does not constitute plagiarism. For some of the entries, specific content words have been included for illustrative purposes, and these should be substituted when the phrases are used. The resource was designed primarily for academic and scientific writers who are non-native speakers of English. However, native speaker writers may still find much of the material helpful. In fact, recent data suggest that the majority of users are native speakers of English. More about Academic Phrasebank .

This site was created by John Morley .

Academic Phrasebank is the Intellectual Property of the University of Manchester.

Copyright © 2023 The University of Manchester

+44 (0) 161 306 6000

The University of Manchester Oxford Rd Manchester M13 9PL UK

Connect With Us

The University of Manchester

Introduction to Level 7 writing

- No categories

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.org

Word Choice

What this handout is about.

This handout can help you revise your papers for word-level clarity, eliminate wordiness and avoid clichés, find the words that best express your ideas, and choose words that suit an academic audience.

Introduction

Writing is a series of choices. As you work on a paper, you choose your topic, your approach, your sources, and your thesis; when it’s time to write, you have to choose the words you will use to express your ideas and decide how you will arrange those words into sentences and paragraphs. As you revise your draft, you make more choices. You might ask yourself, “Is this really what I mean?” or “Will readers understand this?” or “Does this sound good?” Finding words that capture your meaning and convey that meaning to your readers is challenging. When your instructors write things like “awkward,” “vague,” or “wordy” on your draft, they are letting you know that they want you to work on word choice. This handout will explain some common issues related to word choice and give you strategies for choosing the best words as you revise your drafts.

As you read further into the handout, keep in mind that it can sometimes take more time to “save” words from your original sentence than to write a brand new sentence to convey the same meaning or idea. Don’t be too attached to what you’ve already written; if you are willing to start a sentence fresh, you may be able to choose words with greater clarity.

For tips on making more substantial revisions, take a look at our handouts on reorganizing drafts and revising drafts .

“Awkward,” “vague,” and “unclear” word choice

So: you write a paper that makes perfect sense to you, but it comes back with “awkward” scribbled throughout the margins. Why, you wonder, are instructors so fond of terms like “awkward”? Most instructors use terms like this to draw your attention to sentences they had trouble understanding and to encourage you to rewrite those sentences more clearly.

Difficulties with word choice aren’t the only cause of awkwardness, vagueness, or other problems with clarity. Sometimes a sentence is hard to follow because there is a grammatical problem with it or because of the syntax (the way the words and phrases are put together). Here’s an example: “Having finished with studying, the pizza was quickly eaten.” This sentence isn’t hard to understand because of the words I chose—everybody knows what studying, pizza, and eating are. The problem here is that readers will naturally assume that first bit of the sentence “(Having finished with studying”) goes with the next noun that follows it—which, in this case, is “the pizza”! It doesn’t make a lot of sense to imply that the pizza was studying. What I was actually trying to express was something more like this: “Having finished with studying, the students quickly ate the pizza.” If you have a sentence that has been marked “awkward,” “vague,” or “unclear,” try to think about it from a reader’s point of view—see if you can tell where it changes direction or leaves out important information.

Sometimes, though, problems with clarity are a matter of word choice. See if you recognize any of these issues:

- Misused words —the word doesn’t actually mean what the writer thinks it does. Example : Cree Indians were a monotonous culture until French and British settlers arrived. Revision: Cree Indians were a homogenous culture.

- Words with unwanted connotations or meanings. Example : I sprayed the ants in their private places. Revision: I sprayed the ants in their hiding places.

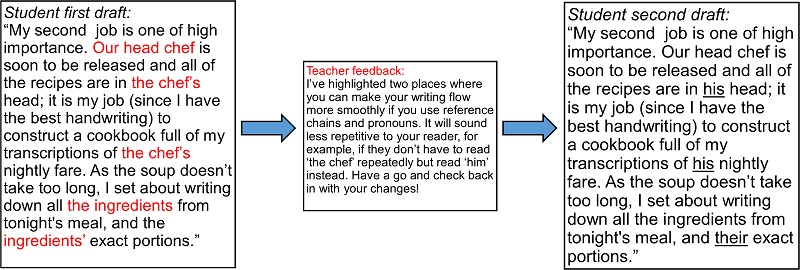

- Using a pronoun when readers can’t tell whom/what it refers to. Example : My cousin Jake hugged my brother Trey, even though he didn’t like him very much. Revision: My cousin Jake hugged my brother Trey, even though Jake doesn’t like Trey very much.

- Jargon or technical terms that make readers work unnecessarily hard. Maybe you need to use some of these words because they are important terms in your field, but don’t throw them in just to “sound smart.” Example : The dialectical interface between neo-Platonists and anti-disestablishment Catholics offers an algorithm for deontological thought. Revision : The dialogue between neo-Platonists and certain Catholic thinkers is a model for deontological thought.

- Loaded language. Sometimes we as writers know what we mean by a certain word, but we haven’t ever spelled that out for readers. We rely too heavily on that word, perhaps repeating it often, without clarifying what we are talking about. Example : Society teaches young girls that beauty is their most important quality. In order to prevent eating disorders and other health problems, we must change society. Revision : Contemporary American popular media, like magazines and movies, teach young girls that beauty is their most important quality. In order to prevent eating disorders and other health problems, we must change the images and role models girls are offered.

Sometimes the problem isn’t choosing exactly the right word to express an idea—it’s being “wordy,” or using words that your reader may regard as “extra” or inefficient. Take a look at the following list for some examples. On the left are some phrases that use three, four, or more words where fewer will do; on the right are some shorter substitutes:

Keep an eye out for wordy constructions in your writing and see if you can replace them with more concise words or phrases.

In academic writing, it’s a good idea to limit your use of clichés. Clichés are catchy little phrases so frequently used that they have become trite, corny, or annoying. They are problematic because their overuse has diminished their impact and because they require several words where just one would do.

The main way to avoid clichés is first to recognize them and then to create shorter, fresher equivalents. Ask yourself if there is one word that means the same thing as the cliché. If there isn’t, can you use two or three words to state the idea your own way? Below you will see five common clichés, with some alternatives to their right. As a challenge, see how many alternatives you can create for the final two examples.

Try these yourself:

Writing for an academic audience

When you choose words to express your ideas, you have to think not only about what makes sense and sounds best to you, but what will make sense and sound best to your readers. Thinking about your audience and their expectations will help you make decisions about word choice.

Some writers think that academic audiences expect them to “sound smart” by using big or technical words. But the most important goal of academic writing is not to sound smart—it is to communicate an argument or information clearly and convincingly. It is true that academic writing has a certain style of its own and that you, as a student, are beginning to learn to read and write in that style. You may find yourself using words and grammatical constructions that you didn’t use in your high school writing. The danger is that if you consciously set out to “sound smart” and use words or structures that are very unfamiliar to you, you may produce sentences that your readers can’t understand.

When writing for your professors, think simplicity. Using simple words does not indicate simple thoughts. In an academic argument paper, what makes the thesis and argument sophisticated are the connections presented in simple, clear language.

Keep in mind, though, that simple and clear doesn’t necessarily mean casual. Most instructors will not be pleased if your paper looks like an instant message or an email to a friend. It’s usually best to avoid slang and colloquialisms. Take a look at this example and ask yourself how a professor would probably respond to it if it were the thesis statement of a paper: “Moulin Rouge really bit because the singing sucked and the costume colors were nasty, KWIM?”

Selecting and using key terms

When writing academic papers, it is often helpful to find key terms and use them within your paper as well as in your thesis. This section comments on the crucial difference between repetition and redundancy of terms and works through an example of using key terms in a thesis statement.

Repetition vs. redundancy

These two phenomena are not necessarily the same. Repetition can be a good thing. Sometimes we have to use our key terms several times within a paper, especially in topic sentences. Sometimes there is simply no substitute for the key terms, and selecting a weaker term as a synonym can do more harm than good. Repeating key terms emphasizes important points and signals to the reader that the argument is still being supported. This kind of repetition can give your paper cohesion and is done by conscious choice.

In contrast, if you find yourself frustrated, tiredly repeating the same nouns, verbs, or adjectives, or making the same point over and over, you are probably being redundant. In this case, you are swimming aimlessly around the same points because you have not decided what your argument really is or because you are truly fatigued and clarity escapes you. Refer to the “Strategies” section below for ideas on revising for redundancy.

Building clear thesis statements

Writing clear sentences is important throughout your writing. For the purposes of this handout, let’s focus on the thesis statement—one of the most important sentences in academic argument papers. You can apply these ideas to other sentences in your papers.

A common problem with writing good thesis statements is finding the words that best capture both the important elements and the significance of the essay’s argument. It is not always easy to condense several paragraphs or several pages into concise key terms that, when combined in one sentence, can effectively describe the argument.

However, taking the time to find the right words offers writers a significant edge. Concise and appropriate terms will help both the writer and the reader keep track of what the essay will show and how it will show it. Graders, in particular, like to see clearly stated thesis statements. (For more on thesis statements in general, please refer to our handout .)

Example : You’ve been assigned to write an essay that contrasts the river and shore scenes in Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. You work on it for several days, producing three versions of your thesis:

Version 1 : There are many important river and shore scenes in Huckleberry Finn.

Version 2 : The contrasting river and shore scenes in Huckleberry Finn suggest a return to nature.

Version 3 : Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

Let’s consider the word choice issues in these statements. In Version 1, the word “important”—like “interesting”—is both overused and vague; it suggests that the author has an opinion but gives very little indication about the framework of that opinion. As a result, your reader knows only that you’re going to talk about river and shore scenes, but not what you’re going to say. Version 2 is an improvement: the words “return to nature” give your reader a better idea where the paper is headed. On the other hand, they still do not know how this return to nature is crucial to your understanding of the novel.

Finally, you come up with Version 3, which is a stronger thesis because it offers a sophisticated argument and the key terms used to make this argument are clear. At least three key terms or concepts are evident: the contrast between river and shore scenes, a return to nature, and American democratic ideals.

By itself, a key term is merely a topic—an element of the argument but not the argument itself. The argument, then, becomes clear to the reader through the way in which you combine key terms.

Strategies for successful word choice

- Be careful when using words you are unfamiliar with. Look at how they are used in context and check their dictionary definitions.

- Be careful when using the thesaurus. Each word listed as a synonym for the word you’re looking up may have its own unique connotations or shades of meaning. Use a dictionary to be sure the synonym you are considering really fits what you are trying to say.

- Under the present conditions of our society, marriage practices generally demonstrate a high degree of homogeneity.

- In our culture, people tend to marry others who are like themselves. (Longman, p. 452)

- Before you revise for accurate and strong adjectives, make sure you are first using accurate and strong nouns and verbs. For example, if you were revising the sentence “This is a good book that tells about the Revolutionary War,” think about whether “book” and “tells” are as strong as they could be before you worry about “good.” (A stronger sentence might read “The novel describes the experiences of a soldier during the Revolutionary War.” “Novel” tells us what kind of book it is, and “describes” tells us more about how the book communicates information.)

- Try the slash/option technique, which is like brainstorming as you write. When you get stuck, write out two or more choices for a questionable word or a confusing sentence, e.g., “questionable/inaccurate/vague/inappropriate.” Pick the word that best indicates your meaning or combine different terms to say what you mean.

- Look for repetition. When you find it, decide if it is “good” repetition (using key terms that are crucial and helpful to meaning) or “bad” repetition (redundancy or laziness in reusing words).

- Write your thesis in five different ways. Make five different versions of your thesis sentence. Compose five sentences that express your argument. Try to come up with four alternatives to the thesis sentence you’ve already written. Find five possible ways to communicate your argument in one sentence to your reader. (We’ve just used this technique—which of the last five sentences do you prefer?)Whenever we write a sentence we make choices. Some are less obvious than others, so that it can often feel like we’ve written the sentence the only way we know how. By writing out five different versions of your thesis, you can begin to see your range of choices. The final version may be a combination of phrasings and words from all five versions, or the one version that says it best. By literally spelling out some possibilities for yourself, you will be able to make better decisions.

- Read your paper out loud and at… a… slow… pace. You can do this alone or with a friend, roommate, TA, etc. When read out loud, your written words should make sense to both you and other listeners. If a sentence seems confusing, rewrite it to make the meaning clear.

- Instead of reading the paper itself, put it down and just talk through your argument as concisely as you can. If your listener quickly and easily comprehends your essay’s main point and significance, you should then make sure that your written words are as clear as your oral presentation was. If, on the other hand, your listener keeps asking for clarification, you will need to work on finding the right terms for your essay. If you do this in exchange with a friend or classmate, rest assured that whether you are the talker or the listener, your articulation skills will develop.

- Have someone not familiar with the issue read the paper and point out words or sentences they find confusing. Do not brush off this reader’s confusion by assuming they simply doesn’t know enough about the topic. Instead, rewrite the sentences so that your “outsider” reader can follow along at all times.

- Check out the Writing Center’s handouts on style , passive voice , and proofreading for more tips.

Questions to ask yourself

- Am I sure what each word I use really means? Am I positive, or should I look it up?

- Have I found the best word or just settled for the most obvious, or the easiest, one?

- Am I trying too hard to impress my reader?

- What’s the easiest way to write this sentence? (Sometimes it helps to answer this question by trying it out loud. How would you say it to someone?)

- What are the key terms of my argument?

- Can I outline out my argument using only these key terms? What others do I need? Which do I not need?

- Have I created my own terms, or have I simply borrowed what looked like key ones from the assignment? If I’ve borrowed the terms, can I find better ones in my own vocabulary, the texts, my notes, the dictionary, or the thesaurus to make myself clearer?

- Are my key terms too specific? (Do they cover the entire range of my argument?) Can I think of specific examples from my sources that fall under the key term?

- Are my key terms too vague? (Do they cover more than the range of my argument?)

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Cook, Claire Kehrwald. 1985. Line by Line: How to Improve Your Own Writing . Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Grossman, Ellie. 1997. The Grammatically Correct Handbook: A Lively and Unorthodox Review of Common English for the Linguistically Challenged . New York: Hyperion.

Houghton Mifflin. 1996. The American Heritage Book of English Usage: A Practical and Authoritative Guide to Contemporary English . Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

O’Conner, Patricia. 2010. Woe Is I: The Grammarphobe’s Guide to Better English in Plain English , 3rd ed. New York: Penguin Publishing Group.

Tarshis, Barry. 1998. How to Be Your Own Best Editor: The Toolkit for Everyone Who Writes . New York: Three Rivers Press.

Williams, Joseph, and Joseph Bizup. 2017. Style: Lessons in Clarity and Grace , 12th ed. Boston: Pearson.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

IELTS Updates And Recent Exams

IELTS Updates And Recent Exams provide complete, efficient and intensive IELTS preparation material to help you achieve the dream score you need. IELTS Updates And Recent Exams upload all Recent IELTS Exam Questions across the globe.

Vocabulary For IELTS: Band 7, Words Lists, Topic Vocab | IELTS Vocabulary PDF

"vocabulary for ielts".

Vocabulary for IELTS is a place that every examinee must master in order to crack the higher IELTS band 7. Learn vocabulary for IELTS in an easy way because you can use words and phrases in the IELTS Speaking and Writing exam. At the end of each lesson, try to use vocabulary in the IELTS practice test. So, what else should you look for in IELTS Vocabulary to reach your dream band score in your IELTS exam.

The Vocabulary for IELTS band score level 7 is given in these topics.

Vocabulary for IELTS Topic 1 : People

1. Adolescent - teenager

2. Characteristic typical feature

3. Individual - person

4. Reliable - can be trusted

5. Conscious - aware

6. Sibling - brother or sister

7. Responsibility - duty

8. Resemble - look like

9. Bond - close tie or link

10. Inherent - natural or instinctive

Vocabulary for IELTS Topic 2 : Health & Fitness

1. Allergic - react badly to

2. Harmful - unsafe

3. Appetite - desire for food

4. Lifestyle - the way you live

5. Ingredients - contents of food

6. Recovery - getting better ( from illness)

7. Hunger - need for food

8. Treatment - medical care

9. Nutritious - full of Vitamins

10. Suffer - feel pain

Vocabulary for IELTS Topic 3 : Science

1. Elementary - basic

2. Combine - mix together

3. Analyze - examine in detail

4. Exposure - in contact with

5. Detergent - soap

6. Side effects - unwanted reaction

7. Basis - the principal idea

8. Toxic - poisonous

9. Fertilizer - plant food

10. Contaminated - polluted

Vocabulary for IELTS Topic 4 : Community

1. Antisocial - against society

2. Conform - follow the rules

3. Cooperate - work together

4. Mindset - attitude

5. Minority - small percentage

6. Shun - avoid

7. Conventional - traditional

8. Interaction - communication

9. Pressure - stress

10. Conduct - behavior

Vocabulary for IELTS Topic 5 : Study

1.Theoretical - academic or not proven

2. Educational - academic / educative

3. Acquire - gain or get

4. Compulsory - must be done

5. Valid - reasonable

6. Determine - discover or find out

7. Establish - prove

8. Significant - important

9. Review - check or go over

10. Concentrate - think very hard

Vocabulary for IELTS Topic 6 : Advertising

1. Persuade - get to agree

2. Convinced - assure

3. Unavoidable - certain to happen

4. Commercialized - focused on profit

5. Effective - achieving its aims

6. Ploy - trick or gimmick

7. Visualize - mentally picture

8. Intrusive - not welcome

9. Promote - advertise

10. Exaggerate - magnify the truth

Vocabulary for IELTS Topic 7 : Travel & Places

1. Memorable - unforgettable

2. Inhabitants - people living in a place

3. Custom - local tradition

4. Attract - act like a magnet

5. Remote - distant/ far away

6. Spectacular - amazing

7. Landscape - large area of countryside

8. Outweigh - be more important than

9. Basic - simple/ not luxurious

10. Barren - without plants

Vocabulary for IELTS Topic 8 : Government

1. Blame - accuse

2. Childcare - care for children

3. Govern - control a place

4. Provide - give/ make/ available

5. Regulation - official rule

6. Depend - need help support

7. Entitlement - right or privilege

8. Healthcare - care for the sick

9. Oppose - be against

10. Assistance - help / aid

Vocabulary for IELTS Topic 9 : Animals

1. Endangered - dying out

2. Venomous - poisonous

3. Domesticates - tame / not wild

4. Thrive - grow/ be successful

5. Predator - animals that hunt another

6. Vulnerable - easily hurt

7. Nocturnal - active at night

8. Dwindle - become smaller or fewer

9. Habitat - A natural environment

10. Prey - hunt / catch

Vocabulary for IELTS Topic 10 : Space

1. Explode - break up violently

2. Explore - search for a new area

3. Risky - dangerous

4. Debris - large broken pieces of satellite or space craft

5. Frightening - makes you afraid

6. Infinite - without end

7. Acclimatize - adjust / adapt / get used to

8. Fascinating - extremely interesting

9. Surface - top layer

10. Astronauts - working in space

Vocabulary for IELTS Topic 11 : Technology & Computer

1. Virtual - not real

2. Digital - computerized

3. Embrace - accept eagerly

4. Online - via the internet

5. Addicted - obsessed

6. Secure - safe

7. Cutting-edge - the very latest

8. Cyber-bullying - attacking online

9. Technological - relate to tech

10. Dated - old-fashioned

Vocabulary for IELTS Topic 12 : Fashion

1. Consumer - user of goods

2. Passing - short-lived

3. Trendy - fashionable

4. Lasting - long-term

5. Impulsive - acts without thinking

6. Consumerism - buying and owning goods

7. Purchase - something bought

8. Impractical - unsuitable for a situation

9. Discard - through away

10. Mass-produced - made on large scale

Vocabulary for IELTS Topic 13 : City

1. Inadequate - not good enough

2. Transportation - means of travel

3. Pedestrian - person walking

4. Commute - journey to work

5. Pavement - service in an area

6. Overpopulated - having too many people

7. Slums - poor quality housing

8. Infrastructure - service in an area

9. Outskirts - edge of the city

10. Isolated - alone / separate

Vocabulary for IELTS Topic 14 : Environment

1. Agricultural - agarian

2. Cultivate - make something grow

3. Disaster - terrible event or accident

4. Erosion - loss of soil

5. Environmental - circumambient

6. Logging - cutting down trees

7. Vital - very important

8. Irrigation - watering system

9. Impact - effect

10. Pesticide - insect killer

Vocabulary for IELTS Topic 15 : Energy

1. Generate - produce

2. Alternative - not traditional

3. Harness - capture and use

4. Mining - digging up coal etc.

5. Renewable - can be made again

6. Sustainable - will not run out

7. Maximize - make the most of

8. Consumption - use / utilization

9. Curb - limit the use of

10. Emission - gases released

"Vocabulary For IELTS Band 8 or 9"

Related Posts

Leave a comment, no comments.

Please do not enter any spam link in the comment box.

Search This Blog

- General Reading

- Recent Exams

- Tips & Tricks

- Writing Task 1

- Writing Task 2

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Payments & Refund Policy

Recent Posts

Random posts, popular posts.

Copyright (c) 2019-2022 IELTS Updates And Recent Exams (IUARE) And Hardeep Singh

- Reader Profiles

Writing for 7th Grade Readers — Syntactic Stats

Sentence Length:

- Average Sentence Length : 15-20 words

- Range : A mix of shorter sentences ( 5-10 words ) and longer, more complex sentences ( 20-30 words )

Sentence Complexity:

- Simple Sentences : About 30-40% of sentences

- Compound Sentences : About 25-35% of sentences

- Complex Sentences : About 20-30% of sentences

- Compound-Complex Sentences : About 5-15% of sentences

Paragraph Structure:

- Average Paragraph Length: 4-6 sentences

7th Grade Reading Rate:

Average reading rate is 150-200 words per minute , though this will vary based on individual differences and text complexity.

Word Length

Word length, measured by the number of letters in a word, also adds to text complexity. For 7th graders, you can see a variety of word lengths. Here’s a general breakdown:

Short Words (1-4 Letters) :

- These make up a large portion of the text, around 50-60% .

- Examples include “the,” “and,” “is,” “cat,” “jump.”

Medium-Length Words ( 5-7 Letters ):

- These common words make up 30-40% of the text.

- Examples include “brother,” “running,” “quickly.”

Long Words ( 8+ Letters ):

- Roughly 5-10% may be longer, more complex words.

- Examples include “community,” “entertainment,” “organization.”

Content-Specific Long Words :

- In texts about subjects like science, history, or literature, students may encounter longer words specific to the content. These words may be explained or defined within the text.

Complexity of Themes and Topics :

- The length of words may vary based on themes or topics. More advanced texts may include a higher proportion of longer words.

Impact on Readability :

- Texts with a higher proportion of longer words may be more challenging to read. Be mindful of word length, sentence structure, and vocabulary to match texts to the appropriate reading level.

Vocabulary Development :

- Educators may provide support for understanding and using longer words through instruction, context clues, and other strategies.

Correlation with Syllables :

- Longer words often correlate with a higher number of syllables, adding to the phonetic complexity of the text.

Punctuation:

- Commas, Periods, Question Marks : Regularly used

- Colons, Semicolons : Introduced but less frequent

- Parentheses, Dashes : Used sparingly for bonus information or emphasis

Vocabulary:

- Tier 2 Vocabulary : High-utility, academic words that are sophisticated but not overly specialized

- Some Tier 3 Vocabulary : Subject-specific or specialized words with explanation or context

Grammar and Syntax :

- Varied Sentence Starters : Different ways to begin sentences (adverbs, conjunctions, prepositional phrases)

- Subordination and Coordination : Use of subordinating and coordinating conjunctions to join clauses

- Active and Passive Voice : Primarily active voice but with some passive constructions

Dialogue and Quotations :

- Proper Use of Quotation Marks : For dialogues and direct quotations

- Internal Dialogue Representation : May include characters’ thoughts or internal dialogues

Use of Figurative Language:

- Similes and Metaphors : Commonly used for imagery

- Personification, Onomatopoeia, Alliteration : Introduced and used to create literary effects

Narrative Techniques:

- Varied Point of View : First person, third person limited, or omniscient point of view

- Flashbacks or Foreshadowing : May be introduced for complex storytelling

Repeat Words vs. Unique Words

The ratio of unique words to repeat words in a text is known as lexical diversity , and it is an important aspect of text complexity. This ratio can vary widely based on the type of text, the subject matter, and the author’s style.

Unique Words :

- Expect 20-30% of unique words in a text . This percentage might be higher in texts that cover specialized topics or use a rich and varied vocabulary.

Repeat Words :

- The remaining 70-80% of words are repetitions previously used in the text. These repeat words include common function words (e.g., “the,” “and,” “is”) and content words essential to the text’s main themes or concepts.

Impact on Readability and Engagement :

- A higher percentage of unique words might make a text engaging and intellectually stimulating, but could also make it challenging to read. Conversely, a higher percentage of repeat words can reinforce understanding but might make a text less engaging.

Content-Specific Vocabulary :

- In subject-specific texts, such as science or history, you may find a higher percentage of unique words related to the subject. The author might repeat these words to reinforce understanding.

Literary Texts :

- Literary texts, such as novels and poems, may have more unique words to create imagery, mood, and character. The repetition of words or phrases may also be used deliberately for effect.

Abbreviated Words

The percentage of abbreviations can vary significantly. Here are some general guidelines:

Fiction Texts :

- Percentage : Approx. 1-3% .

- Usage : Abbreviations in fiction are limited to dialogue or specific contexts where they would naturally occur.

- Example : Common titles like “Mr.” or “Dr.,” or colloquial expressions.

Non-Fiction Texts :

- Percentage : Approx. 3-5% .

- Usage : In non-fiction, especially in subject areas like science or history, abbreviations and acronyms might be used more frequently.

- Example : “U.S.” for United States, “WWII” for World War II, “DNA” for deoxyribonucleic acid.

Textbooks or Educational Materials :

- Percentage : Varies, could be up to 5-10% .

- Usage : Textbooks might use abbreviations for terms frequently repeated or when introducing specific concepts.

- Example : “e.g.” for example, “i.e.” for that is, or subject-specific abbreviations like “kg” for kilograms.

Syllables also determine reading complexity and accessibility. Here’s a breakdown of what you might expect:

Average Syllables per Word :

- Around 1.4 to 1.6 syllables. This reflects a mix of monosyllabic and multisyllabic words suitable for this grade level.

Use of Monosyllabic Words :

- Around 60-70% of the words may be monosyllabic. These words form the core of English and are more familiar to students.

Use of Multisyllabic Words :

- Roughly 30-40% of the words may have two or more syllables.

Within this category, you may find:

- 2-syllable words : 15-20%

- 3-syllable words : 8-12%

- 4 or more syllable words : 3-5%

Challenging Vocabulary :

Challenging words with three or more syllables may be introduced to stretch students’ vocabulary and reading comprehension. Words like: “unforgettable,” “disappointment,” or “entertainment.”

Content-specific Multisyllabic Words :

In subject-specific texts, such as science or history, students encounter multisyllabic terms like “photosynthesis” or “Constitution.” Definitions and explanations are often provided for these terms.

Poetic and Literary Texts :

In poetry or literary prose, syllables are varied to create rhythm, imagery, or emotional effect. These texts have more multisyllabic words and require more guidance and discussion to understand fully.

Reading Aloud and Phonics Support :

Reading aloud and phonics activities can assist 7th graders in tackling multisyllabic words by breaking them down into manageable parts.

The syllable structure helps strike a balance between readability and challenge. The blend of simpler and more complex words encourages students to expand their vocabulary and comprehension while providing accessible and engaging reading material.

Active Voice vs. Passive Voice

The balance between active and passive voice can affect its readability and engagement. Here’s a general guideline for what you might expect:

Active Voice :

- Percentage : Around 70-90% .

- Usage : Active voice is more direct and engaging. It’s preferred in storytelling and most non-fiction texts.

- Example : “The scientist conducted the experiment,” instead of “The experiment was conducted by the scientist.”

Passive Voice :

- Percentage : Around 20-30% .

- Usage : Passive voice can be used to emphasize the action rather than the doer of the action. It might be more common in scientific writing or formal reports, where the focus is on the result or process.

Subject-Specific Considerations :

- In science or formal academic writing, the passive voice might be used more frequently to create an objective tone.

- In literature or general non-fiction, active voice is likely to predominate to create a more engaging and accessible style.

Teaching Considerations :

- In 7th grade, students begin to distinct between active and passive voice and how to use each. They might be encouraged to use active voice in their writing but also to recognize situations where passive voice is appropriate.

Impact on Reading Comprehension :

- Excessive use of passive voice can make a text more challenging to read, as it often requires more cognitive processing. However, some passive constructions are better for conveying specific meanings or adhering to a writing style.

Parts of Speech:

- Nouns : 20-25% .

- Verbs : 15-20% .

- Adjectives : 10-15% .

- Adverbs : 5-10% .

- Conjunctions, Prepositions, Interjections : Varying percentages depending on writing style.

Proper Nouns:

The percentage of proper nouns in a text for 7th graders also varies depending on the genre, subject matter, and context of the text.

- Percentage: 5-8% .

- Use: This includes the names of characters, locations, specific events, etc.

- Example: In a novel set in a real-world location, names of cities, landmarks, and people are common.

- Percentage: 3-6% .

- Use: historical names, brand names, scientific terminology, and so on.

- Example: A history text might include names of significant individuals, places, and events.

- Percentage: Varies, around 4-7% .

- Use: Specific terms, names of theories, scientists, historical figures, and geographical locations.

- Example: In a science textbook, names of scientists, theories, and specific terminologies are considered proper nouns.

Cultural and Contextual Considerations :

- The frequency of proper nouns might influence cultural references and the subject matter.

Reading Comprehension and Engagement :

- Too many unfamiliar proper nouns without context or explanation can hinder reading comprehension.

- Percentage : 1-3% .

- Length : Shorter numbers like dates, ages, or quantities.

- Use : Numbers in fiction might relate to time, age, quantity, or other basic numerical information.

- Percentage : 2-5% .

- Length : Varies depending on the topic. Short numbers for general information, longer numbers for scientific or mathematical content.

- Use : This could include dates, statistics, measurements, etc.

Textbooks or Educational Materials:

- Percentage : Varies widely, from 5-15% or more, especially in mathematics or science texts.

- Length : Can vary from simple, single-digit numbers to more complex numbers, including decimals, fractions, or large quantities.

- Use : Numbers in educational texts could represent anything from simple counting to complex mathematical or scientific data.

General Considerations:

- Comprehension : The complexity and frequency of numbers should match the readers’ numerical literacy. Long and complex numbers may be challenging for some 7th graders, depending on their math background.

- Contextual Clues : Providing context or explanation for numbers, especially if they are central to understanding the content, is essential.

- Subject-Specific Texts : In subjects like mathematics, physics, or economics, numbers will be more prevalent and can be more complex.

- Cultural Considerations : Numbers might be influenced by cultural norms, such as the use of commas or periods in large numbers.

Dialogue vs. Description (for Fiction):

- Dialogue : 40-60% (can vary widely based on author’s style and genre).

- Description/Narration : 40-60% .

Text Cohesion:

- Transition Words : Approximately 3-5% .

Vocabulary Stats

Here’s a breakdown of vocabulary for 7th-grade readers.

- Vocabulary Size : Student know around 20,000 to 25,000 English words.

- Lexile Range : Texts align with a Lexile measure 950L to 1075L , a measure of text complexity.

- Academic Vocabulary : Students can understand and use 700-900 academic words across various subjects. Roughly, this could consist of:

- Science : 150-200 words

- Mathematics : 100-150 words

- History : 150-200 words

- Literature : 100-150 words

- Reading Comprehension : 60-80% for age-appropriate material.

- Words per Minute (WPM) : The average reading rate ranges from 150-200 WPM.

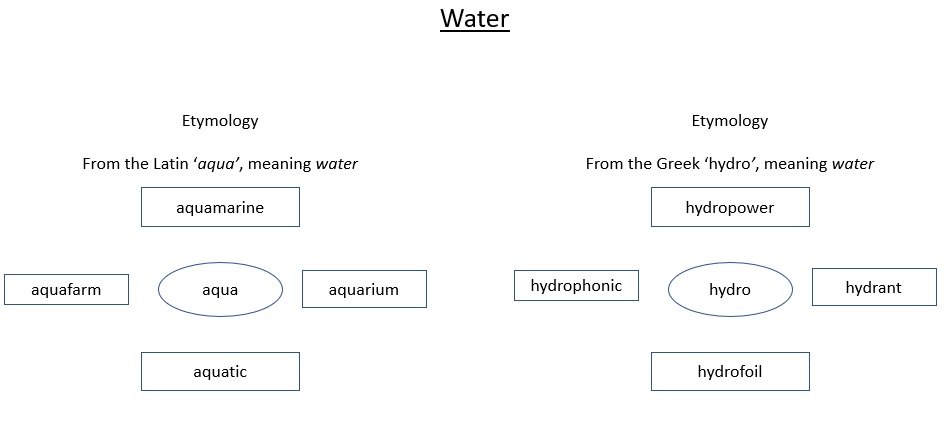

- Morphological Understanding : Understanding complex words through Latin and Greek roots might cover around 300-500 common roots and affixes.

What is a 7th Grade Reading Level?

The reading level for 7th graders uses texts that contain sophisticated language, themes, and structures.

- Sentence Structures : Sentences may include multiple clauses and higher-level punctuation. For example, “ While she studied for her history test, her brother, who had already finished his homework, played his favorite video game .”

- Multifaceted Plotlines : Books may contain several intertwining plotlines or themes. An example is “ Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix ” by J.K. Rowling , where she introduces various storylines involving friendship, politics, magical education, and personal growth.

- Abstract Ideas and Themes : Themes like moral ambiguity, identity, and self-discovery are explored. A novel like “ The Giver ” by Lois Lowry introduces concepts of utopia, memory, and societal control that provoke deeper thinking.

- Use of Figurative Language : 7th graders are exposed to metaphors, similes, allegories, and symbolism. For instance, in “ A Wrinkle in Time ” by Madeleine L’Engle , the concept of the “tesseract” is used as a symbol to connect dimensions of space and time.

- Vocabulary : Words outside of everyday language begin to appear in their reading. In “ The Hobbit ” by J.R.R. Tolkien , words like “flummoxed” and “beseech” are included, which may require the reader to use context clues or a dictionary.

- Non-Fiction and Varied Genres : They might read historical accounts, scientific explanations, or biographical texts that require comprehension of factual information and more formal language. For example, “ Diary of a Young Girl ” by Anne Frank provides historical insight into World War II from a teenager’s viewpoint.

- Author’s Craft : Readers in 7th grade start to identify literary devices such as irony, foreshadowing, or unreliable narrators. Edgar Allan Poe’s short stories, like “ The Tell-Tale Heart ,” exemplifies these techniques.

Teachers and caregivers might use a mix of classical literature, contemporary novels, and non-fiction texts to create a well-rounded reading experience.

7th Grade Vocabulary Overview

Word Recognition :

- Complex Words : They can recognize and understand more complicated words that might be subject-specific or related to themes in literature, such as “democracy,” “metabolism,” or “foreshadowing.”

- Multisyllabic Decoding : They can decode multisyllabic words by recognizing syllable patterns and using phonics skills.

Context Clues :

- Inferencing Meaning : 7th grade readers can infer the meaning of unknown words by examining the surrounding text, looking for synonyms, antonyms, explanations, or examples in the context.

Word Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes :

- Morphological Awareness : Readers begin to understand common word roots and affixes (prefixes and suffixes), enabling them to deduce the meanings of unfamiliar words. For example, knowing that “tele” means distant can help with words like “telescope” or “telecommunication.”

Domain-Specific Vocabulary :

- Subject-Related Terms : They can comprehend vocabulary specific to subjects like science, history, or literature. For example, in science, words like “photosynthesis” or “ecosystem” become part of their vocabulary.

Synonyms and Antonyms :

- Expression : They can identify synonyms and antonyms, allowing for expression and understanding of nuances in meaning. They might recognize that “benevolent” is a synonym for “kind,” but with a slightly different connotation.

Figurative Language :

- Idioms and Metaphors : They begin to understand figurative expressions, such as idioms, metaphors, and similes. They can interpret phrases like “break a leg” or understand metaphorical comparisons like “the world is a stage.”

Writing and Speaking :

- Expressive Vocabulary : They can apply new vocabulary in their writing and speaking, enhancing their ability to communicate ideas more precisely and creatively.

Reference Materials :

- Dictionary and Thesaurus Skills : They are adept at using dictionaries, thesauruses, and online tools to look up unfamiliar words, understand multiple meanings, and find synonyms and antonyms.

Vocabulary in Different Contexts :

- Adapting Language : They can adjust their language based on the context, recognizing the difference between formal and informal language, and choosing words accordingly.

Cultural and Global Awareness :

- Exposure to diverse reading materials can help them understand words and expressions from various cultural backgrounds, fostering global awareness.

Overall, 7th-grade readers’ vocabulary skills reflect a move towards greater complexity, nuance, and adaptability. This development supports their ability to comprehend more sophisticated texts, engage in critical thinking, and express themselves with greater clarity and creativity.

7th Grade Word Usage

The word usage reflects a growing command of language that allows for more nuanced and expressive communication.

Complex Sentence Structure :

- Compound and Complex Sentences : They are beginning to use more compound and complex sentences, combining ideas using conjunctions like “although,” “however,” and “therefore.”

- Varied Sentence Openings : They can vary sentence beginnings to create interest and rhythm in their writing.

Descriptive Language :

- Adjectives and Adverbs : They can use adjectives and adverbs to provide more detailed descriptions, such as “ The swiftly flowing river wound through the lush, green valley .”

- Sensory Details : They are developing the ability to use sensory details to create vivid imagery in their writing.

- Similes and Metaphors : They may use similes and metaphors to add depth to their writing, such as comparing ideas or feelings to something tangible. E.g., “Her smile was as bright as the sun.”

- Idiomatic Expressions : They can begin to use idioms in their speech and writing, understanding their figurative meanings.

Formal vs. Informal Language :

- Understanding Register : They can recognize when to use formal language in academic or professional settings and informal language with friends or family. For example, using “cannot” instead of “can’t” in a formal essay.

Subject-Specific Vocabulary :

- Appropriate Usage : They are learning to use subject-specific vocabulary in subjects like science, history, or mathematics, understanding when and how to use these terms accurately.

Persuasive Language :

- Rhetorical Devices : They may begin to experiment with rhetorical devices like rhetorical questions, repetition, or parallel structure to persuade or engage their audience.

Transition Words and Phrases :

- Cohesiveness : They use transition words and phrases to guide the reader through their ideas and show connections between thoughts, such as “in addition,” “on the other hand,” or “as a result.”

Pronoun Consistency :

- Proper Use of Pronouns : They usually demonstrate an understanding of pronoun-antecedent agreement, ensuring that pronouns match in number and gender with the nouns they refer to.

Connotation and Tone :

- Word Choice for Effect : They can choose words for their connotative meanings, understanding how word choice can affect the tone and mood of a piece. For example, using “slim” instead of “skinny” to convey a more positive tone.

7th Grade Word Usage Challenges

Complex Multisyllabic Words :

- Examples : “Photosynthesis,” “apprehension,” “circumference.”

- Challenge : The length and complexity of these words can make pronunciation and understanding difficult.

Homonyms, Homophones, and Homographs:

Words that sound or look the same but have different meanings can be confusing in both reading and writing.

- Examples : “lead” (to guide) vs. “lead” (a type of metal), “two” vs. “too” vs. “to.”

Technical and Subject-Specific Vocabulary:

These terms are often new and specific to subjects such as science, literature, or mathematics, requiring context and background knowledge.

- Examples : “mitosis,” “allegory,” “quadratic.”

Words with Uncommon or Irregular Spellings:

Unusual or non-phonetic spelling can make these words difficult to read, spell, and remember.

- Examples : “pneumonia,” “rhythm,” “colonel.”

Advanced Abstract Concepts:

Words that represent complex, abstract ideas may require higher-level thinking and context to fully grasp.

- Examples : “existential,” “philosophy,” “dichotomy.”

Idiomatic Expressions and Figurative Language:

These phrases often cannot be understood literally, and understanding them requires familiarity with cultural context.

- Examples : “Bite the bullet,” “the ball is in your court.”

Background Knowledge or Cultural Awareness:

Without prior knowledge or context, these words might be challenging to comprehend.

- Examples : Names of historical events, cultural terms like “samurai” or “Renaissance.”

Words with Multiple Meanings:

Choosing the correct meaning based on context requires careful reading and understanding.

- Examples : “light” (not heavy vs. illumination), “bark” (of a tree vs. a dog’s sound).

Formal and Archaic Language:

Readers will see these confusing words in classical literature.

- Examples : “thou,” “whence,” “heretofore.”

Language with Emotional or Social Nuance:

Words that convey subtle social or emotional nuances might require maturity and social awareness to fully understand.

- Examples : “sarcasm,” “empathy,” “prejudice.”

Foreign Words and Phrases:

Words and phrases borrowed from other languages may be unfamiliar and require explanation.

- Examples : “déjà vu,” “cliché,” “tsunami.”

Words that Break Standard Phonics Rules:

These words don’t follow typical sound-letter correspondence, making them tricky to read and spell.

- Examples : “through,” “though,” “knight.”

The best syntactic writing style for 7th graders strikes a balance between complexity and clarity. It challenges readers to grow their comprehension and analytical skills without overwhelming them. By using a mix of sentence types, appropriate vocabulary, and clear organization, writers can create engaging and educational texts for this age group.

Related Articles

Writing for 3rd Grade Readers — Syntactic Stats

Writing for 1st Grade Readers — Syntactic Stats

You may have missed.

From Paper to Pixels: Adapting Readability for Today’s Tech-Savvy Readers

What are Lexical Density and Lexical Diversity?

Readability vs. SEO: Striking the Perfect Balance for Online Content

Improve Your Writing Style with Cognitive Load Theory

Readability Formulas: The Science Behind Reading Scales and Grade Scores

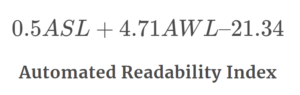

How to Use the Automated Readability Index (ARI) for Clearer Communication

Creating texts: word and sentence level

Creating sentences (writing).

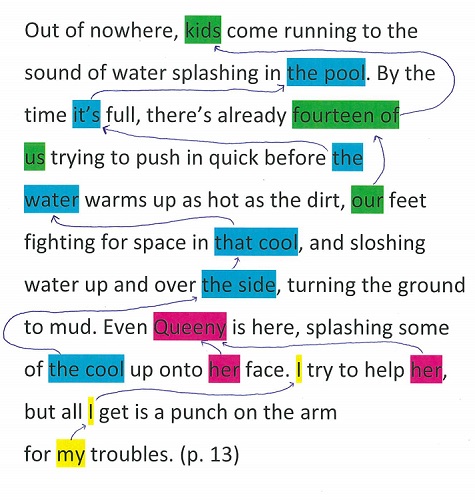

Often the focus in classrooms is on producing whole texts; however, it is important to give students explicit opportunity to pay attention to writing at the text, sentence and word levels (Rose and Martin 2012).

Text level requires attention to patterns that are evident in different genres (e.g. passive voice in an explanation, abstract nouns in an argument) as well as to the ways in which the parts of the text are linked (e.g. through the use of connectives) (Derewianka, 2011).

Sentence level requires examination of the ways in which clauses are combined or how clauses relate to each other (e.g. relationships of time, place, causality) (Derewianka, 2011). Word level attends to the individual words or groups of words such as nouns/ noun groups. (Derewianka, 2011).

The following strategies support students to focus on the construction of sentences and to develop confidence in talking about their writing. Both also offer students the experience of exploring articulating both the language choices they have made and exploring the effect of their writing on others ( VCELY395 and VCELY396 ).

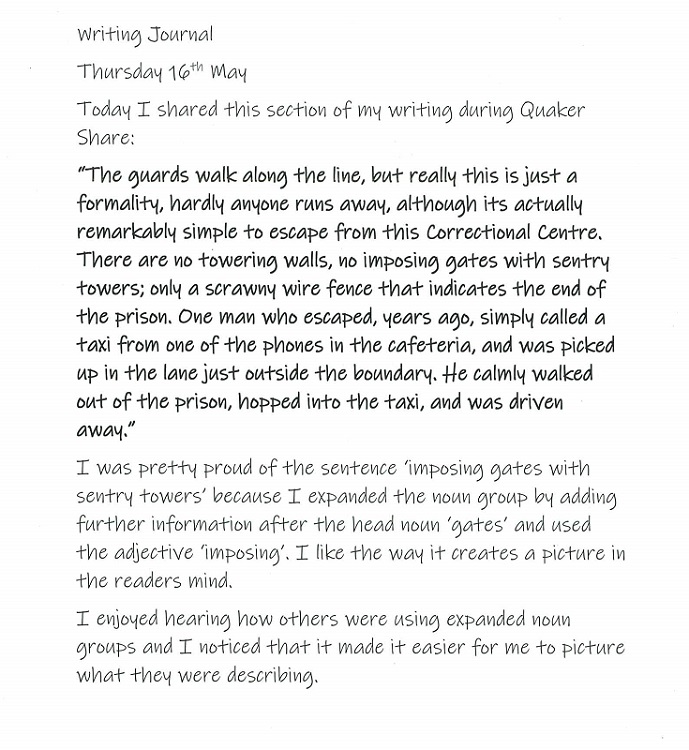

Quaker share

A Quaker Share (Dawson 2009) is used to support students to share their own writing in a group, to build confidence about reading aloud, and to provide them with opportunities to explore the impact of their writing on others.

A traditional Quaker Share is loosely structured in the following ways:

- Students read aloud a few of their sentences to the group.

- The reading moves around the group, but no comments are made about what is read.

- Students can be encouraged to record things they hear that they find enjoyable or particularly interesting.

- Once each member of the group has shared some of their writing, they discuss how it felt to read to a group who is quiet and listens.

This activity can be adapted and focused in in many ways, depending upon the context of the group and purpose of learning. Always consider the ways that you may employ this strategy so that your students feel comfortable to share their writing. The teacher may decide that on the first occasion students share with a small group but then progress to a larger group as confidence is developed.

In the context of narrative writing, the teacher might ask for students to share a paragraph that includes 2-3 sentences that use expanded noun groups well (for example, ‘a kind-hearted soul in the shape of a lonely old man leaning on the window’) or employs particular types of figurative language such as metaphor or simile (for example, ‘like a hungry lion grabbing free meat’).

Students can be led in a sharing time once the reading has completed, where they reflect on their experiences reading their work aloud, and experiences of listening to others. What did they learn about language and their own writing through this process?

Supports and scaffolds can be adjusted for differing student abilities and confidence, particularly for students for whom English is an additional language/dialect.

If the activity is done regularly through writing units, students can build up reflections on the writing process in a writing journal.

Celebrating sentences

Hattie and Timperley (2007) remind us of the vital role of feedback on student learning.

Building on the Quaker Share strategies, Celebrating Sentences is designed to:

- support the sharing of writing at the level of sentences in the classroom

- to draw attention to the way language creates meaning and effect

- to encourage students to feel empowered as writers.

This strategy is used when students are peer conferencing a piece of writing, such as an argumentative text.

They are asked to highlight two to three sentences in the paragraph, or paragraphs they are reading that they find convincing. Both students (writer and reader) are then tasked with identifying what makes these sentences convincing, and then applying this learning to another part of the text.

For example, the following sentence from a Year 8 persuasive essay on compulsory sport might be highlighted by the student writer’s peer:

Secondly, compulsory sport is a negative experience for students who are not good at sport. Some students feel embarrassed, degraded, and belittled about their skill levels and might be bullied by their team mates because they aren’t very good at sport.

16% of students in America are overweight, they need to do some activity but compulsory sport is not the solution. A school psychologist called Emma says that for some students, sport is an ‘uncomfortable experience’. If students feel bad about themselves then they might quit sport as adults which will be bad for their health. This means that compulsory sport can have a bad impact on students’ wellbeing.

The questions students might ask each other are:

- Which words have an impact on the reader? They might notice the sensing verb ‘feel’ and evaluative adjectives embarrassed, degraded, and belittled which present negative feelings .

- What might this mean for other sentences that are not as persuasive? They might notice will be bad and might be bullied to consider more effective use of modal verbs and intensifying or modal adverbs (for example, possibly, probably, certainly, definitely) to suggest the degree of likelihood or probability of the occurrence of feelings. The table below assists student to build verb groups in this and other activities.

Experimenting with modal verbs and modal adverbs (intensifiers)

Students can write the sentences they are celebrating on a shared digital space (such as a word document or padlet.com). The teacher can then lead a discussion of the characteristics of the celebratory sentences. This can provide opportunities for the class to see and understand what makes successful writing in the particular genre being studied, such as the examples detailed below that explore the use of modality in persuasive texts.

Discussion of the example sentences could include discussion points such as the following:

- Modal verbs of different strength such as might, will, must can modulate the writer’s stance or position.

- Modal adverbs or intensifiers of different strength such as possibly, probably, certainly can also modulate the writer’s stance or position.

- More precise language choices such as ‘experience’ instead of ‘feel’, ‘discomfort’ or ‘embarrassment’ instead of ‘bad’ suggest a stronger sense of negative attitudes or feelings.

- Including a noun group such as ‘a significant impact on student confidence’ is more ‘written like’ or academic language and provides a sense of the author’s authority or expertise on the topic.

Identifying key vocabulary (writing)

Helping students to identify key words about their topic before they commence the writing process is an important way to build vocabulary.

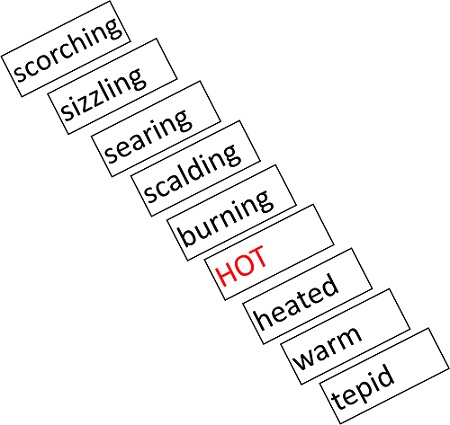

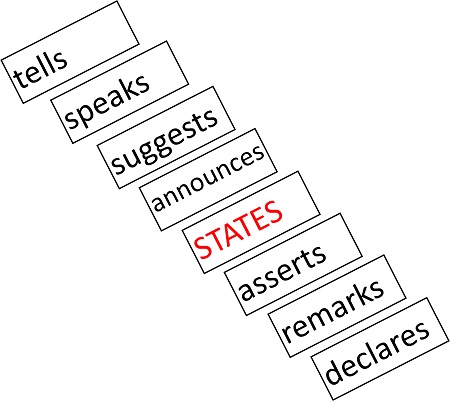

A word cline is an effective strategy that helps students to reinforce their understanding of the meaning of words and to extend their vocabularies. The word cline comes from the Greek word clino – to slope.

A word cline, therefore, is a graded sequence of words whose meanings are arranged in a continuum that is usually shown on a sloping line. The purpose of the activity is to have students discuss and explore the subtle shifts in meaning that occur when language is arranged in a graduated manner. This strategy can be used in all forms of writing, including, narratives, imaginative and persuasive texts.

Word cline for the adjective ‘hot’

Word cline for the verb ‘states’

At the Year 7 level, word clines help students investigate how language works and prepare students for their own writing ( VCELA371 , VCELY387 ).

Word clines for verbs are helpful scaffolds that assist students’ discussion of word choices and shades of meaning, setting them up well for textual analysis in the later secondary years ( VCELA474 ).

Sentence starters (writing)

When students begin to write more sustained pieces of written work, one of the challenges they often face is being able to vary the language used to open new paragraphs.

Teachers can help students to experiment with their language, through the explicit teaching ( HITS Strategy 3 ) of sentence starters. This strategy supports students to build their repertoire of text connectives so that they develop cohesion in their writing.

Using sentence starter lists

A useful way for students to learn to build sentence starters into their own work is to provide them with a list of words that relate specifically to the text type or genre they are creating.

The most appropriate text connectives to use are the ones that fit the purpose of the writing. For example, the text connectives in a narrative indication time are used to sequence events chronologically, often at the beginning of the sentence. For example, after that, after a while, then.

In an exposition, a range of text connectives might be used for different purposes. For example:

- additive, also, moreover; causative

- as a result, consequently, conditional/concessional

- otherwise, in that case, however, sequential

- to begin with, in conclusion; clarifying

For the purposes of this activity, focus on the text connectives that can be used at the beginning of sentences.

- in other words

- to put it another way

- for example

- for instance

- in particular

- as a matter of fact

- consequently

- as a consequence

- as a result

- accordingly

- in that case

- for that reason

- at this point

- furthermore

(Adapted from Derewianka, Beverly. (2011) A New Grammar Companion for Teachers. NSW, PETA.)

In addition to highlighting text connectives, students can be taught about the ways in which dependent clauses and prepositional phrases are used at the beginning of sentences to create particular narrative effect.

For example, after a second of wondering, they ran through the door… In the enchanted forest on a magical land far, far away, three pixies were sleeping under a tree …In an exposition, passive voice might be used to foreground the object e.g. When the rainforests are burnt to make way for palm oil plantations, the orangutans’ habitat is destroyed.

Curriculum link for the above example: VCELA414 .

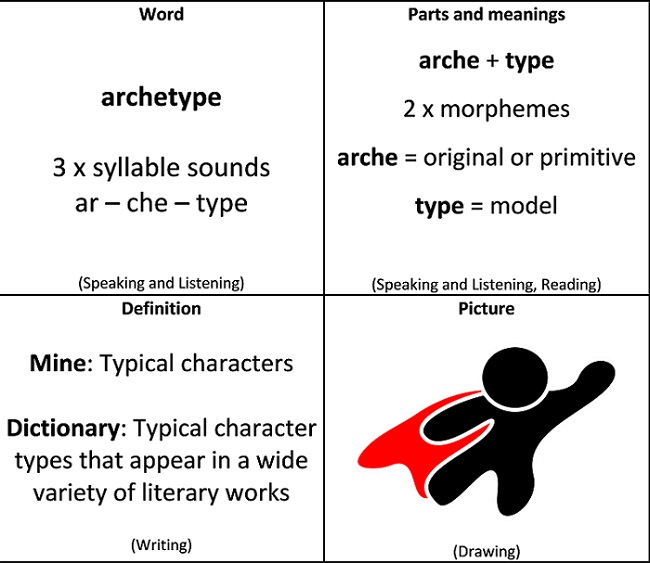

Supporting student spelling (reading and viewing, writing)

Developing spelling knowledge is best undertaken contextually, through the production of texts. The spelling strategies below, conducted in the context of meaningful interaction with texts, take a number of forms that increase in complexity, including strategies which develop knowledge at four levels:

- Phonological knowledge - knowledge of the sound structure of language.

- Visual knowledge - knowledge of the system of written symbols used to represent spoken language.

- Morphological knowledge - knowledge of the smallest parts of words that carry meaning.

- Etymological knowledge - knowledge of the origins of words (Oakley & Fellowes, 2016, p.6).

We might also translate this knowledge into simpler terms:

- Phonological strategies: how words sound.

- Visual strategies: how words look.

- Morphological strategies: how to find meaningful parts within words.

- Etymological strategies: how the origin of words determine spellings.

Teachers should consider how to incorporate these spelling strategies into the teaching of genre and text types, as a way of building and extending vocabulary.

While the Look, Say, Cover Write, Check (LSCWC) approach has dominated English classrooms for decades as the primary strategy for teaching spelling, research has found that this approach provides minimal transfer to later independent writing and that students lack the ability to use this strategy to generalise (Beckham-Hungler et al, 2003).

The memorisation of whole words from lists that are then assessed through weekly spelling tests does not represent best practice, and research has shown that successful spellers use a greater variety of strategies compared to poor spellers (Critten, Connelly, Dockrell & Walter, 2014).

Systematic instruction in spelling is important, however, it should take place in the context of general principles and sound policy towards writing.

In addition to inquiry-based approaches to teach spelling , Winch et al. (2012) describe the following principles which should be kept in mind when supporting students to develop connections between spoken and written words:

- The language skills of reading, writing, listening and speaking are inextricably linked.

- The main responsibility of a teacher is to motivate students to write clearly over a wide range of text-types.

- Shared, guided and independent writing activities will help students to write more confidently.

- The teacher should assist where advice is most likely to be noticed and acted upon, namely at the individual student’s point of need.

- The teacher should encourage a habit of self-correcting when students write (p.329).

Phonological knowledge refers to knowledge about the sounds in language. It is an important part of learning to write (and read). As part of learning to spell, students need to develop phonological awareness, that is, the ability to hear, identify, and manipulate syllables, rhymes and individual sounds (phonemes) in increasingly complex words ( VCELA475 ).

One way to improve spelling is through segmenting activities. Segmenting is the ability to split words into their separate speech sounds. Segmenting advances in complexity, from:

- sentence segmentation

- to syllable segmenting and blending

- to blending and segmenting individual sounds (phonemes).

It cannot be assumed that all students in the secondary years have successfully developed phonological knowledge, and secondary English teachers may find it useful to introduce sentence segmenting activities (below) before moving onto to more complex segmenting approaches.

Segmenting at the word level begins with an emphasis on syllables. Teachers should begin with one and two syllable words, asking students to sound-out aloud each syllable in a word (as in ‘to-pic’, ‘no-vel’, ‘po-em’). Students can be encouraged to clap as they complete this activity which will allow them to make stronger connections between individual sounds and syllables. Progression can be made by adding two-three syllable words, and so on.

For some students in secondary school, there might be a need to identify individual sounds (phonemes) in words and to provide support in blending sounds or using onset-rime activities to decode words.

Onset-rime activities involve breaking words into their onsets (consonants before the consonants), and the rime (everything left in the word).

For example, the rime "own" as in "down" could have different onsets to make words such as:

This use of segmenting, from the sentence to syllable to phoneme, will help develop phonological awareness and an understanding of the relationship between sounds and the alphabetic symbols that represent them in writing (phonics).

Visualisation

Visual, or orthographic, knowledge is the awareness of the symbols (letters or groups of letters) used to represent the individual sounds of spoken language in written form. To spell fluently, students also need to know about how written letters are arranged in English ( VCELA384 ).

Two visual strategies which represent variations of Look, Say, Cover, Write, Check, have been devised by Westwood (1994) and develop visual knowledge. They are:

Variation 1:

- Look at the word.

- Say – make sure you know how to pronounce the word.

- Break the word into syllables.

- Write the word without copying.

- Check what you have written.

Variation 2:

- Select a difficult word.

- Pronounce the word slowly and clearly.

- Say each syllable of the word.

- Name the letters in the word.

- Write the word, naming each letter as you write.

These visual strategies can help students remember specific written words and word parts.

Grouping common morphemes

Morphemes represent the smallest meaningful units of language. Morphemes come in two forms.

Free morphemes that can stand alone with a specific meaning. For example, Catch, Cook, or Strong.

Bound morphemes cannot stand on their own and can only appear as part of another word. Prefixes and suffixes are examples of bound morphemes. Prefixes are bolted on to the front of a word to add specific meaning.

Prefixes can give a sense of order in time. For example, the prefix [fore-] in the words

Fore- indicates a sense of something happening before the action described in the base word. To foresee is to see something before it happens.

Other English prefixes like [dis-] [de-] [mis-] and [un-] signal the opposite meaning to the word it is attached to (Hamawand, 2011).

We can see negative prefixes in words like:

- de stabilise

- de construct

- dis similar

- mis interpret

- mis shapen.

English spelling rule for adding prefixes

When you add a prefix to a base or root word, you can always just bolt it straight on. No need to change the spelling of the word it attaches to.

Dis + similar = dissimilar mis + shapen = misshapen un + necessary = unnecessary

Suffixes carry meaning and are bolted on to the end of a word where the combination of the base and the suffix forms a new word.

Suffixes also play an important role in the nominalisation of English words. Nominalisation refers to the process of turning a verb into a noun form.

Example, ‘Consideration of this issue is vital’ instead of ‘You should consider this issue’.

Nominal suffixes

Nominal suffixes are attached to the end of verbs or adjectives to form nouns.

For example, we can form nouns when we add the suffixes:

We can see how verbs are nominalised by adding a nominal suffix in these word sums:

- celebrate + ion = celebration

- modulate + ion = modulation

- enjoy + ment = enjoyment.

We can see how adjectives are nominalised by adding a nominal suffix in these word sums:

- aware + ness = awareness

- appear + ance = appearance.

English spelling rule for adding suffixes

When you add a suffix to a word, you need to change the spelling if the word it attaches to ends in a vowel letter and the suffix also begins with a vowel letter.

For example, the verb ‘regulate’ can be nominalised by adding the suffix [-ion]. The spelling rule for adding suffixes determines that the final letter ‘e’ must be dropped before adding ‘ion’ as it begins with a vowel letter (a, e, I, o, u or y).