- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Argument and Argumentation

Argument is a central concept for philosophy. Philosophers rely heavily on arguments to justify claims, and these practices have been motivating reflections on what arguments and argumentation are for millennia. Moreover, argumentative practices are also pervasive elsewhere; they permeate scientific inquiry, legal procedures, education, and political institutions. The study of argumentation is an inter-disciplinary field of inquiry, involving philosophers, language theorists, legal scholars, cognitive scientists, computer scientists, and political scientists, among many others. This entry provides an overview of the literature on argumentation drawing primarily on philosophical sources, but also engaging extensively with relevant sources from other disciplines.

1. Terminological Clarifications

2.1 deduction, 2.2 induction, 2.3 abduction, 2.4 analogy, 2.5 fallacies, 3.1 adversarial and cooperative argumentation, 3.2 argumentation as an epistemic practice, 3.3 consensus-oriented argumentation, 3.4 argumentation and conflict management, 3.5 conclusion, 4.1 argumentation theory, 4.2 artificial intelligence and computer science, 4.3 cognitive science and psychology, 4.4 language and communication, 4.5 argumentation in specific social practices, 5.1 argumentative injustice and virtuous argumentation, 5.2 emotions and argumentation, 5.3 cross-cultural perspectives on argumentation, 5.4 argumentation and the internet, 6. conclusion, references for the main text, references for the historical supplement, other internet resources, related entries.

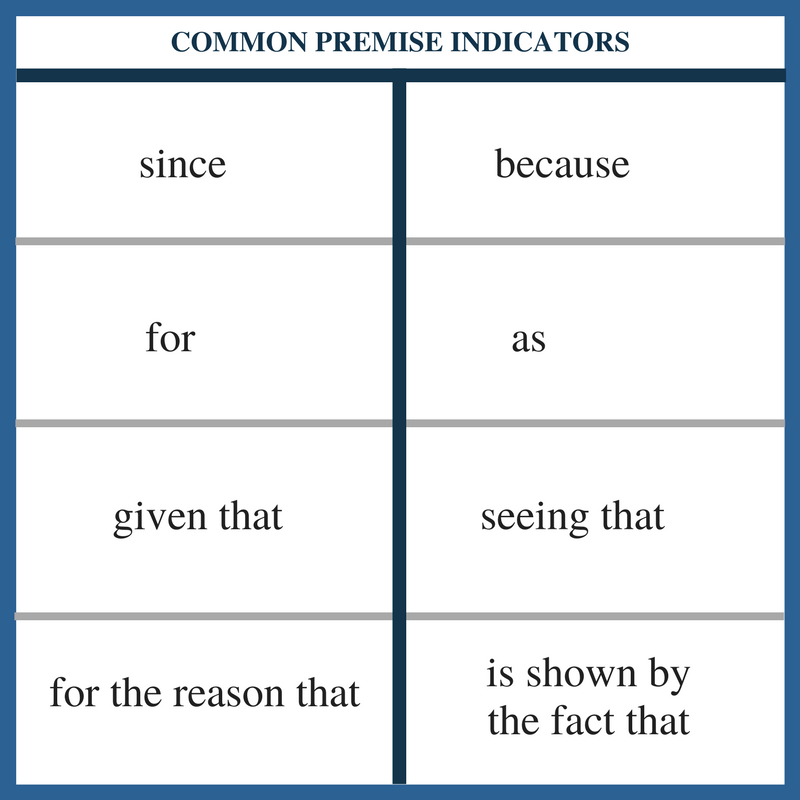

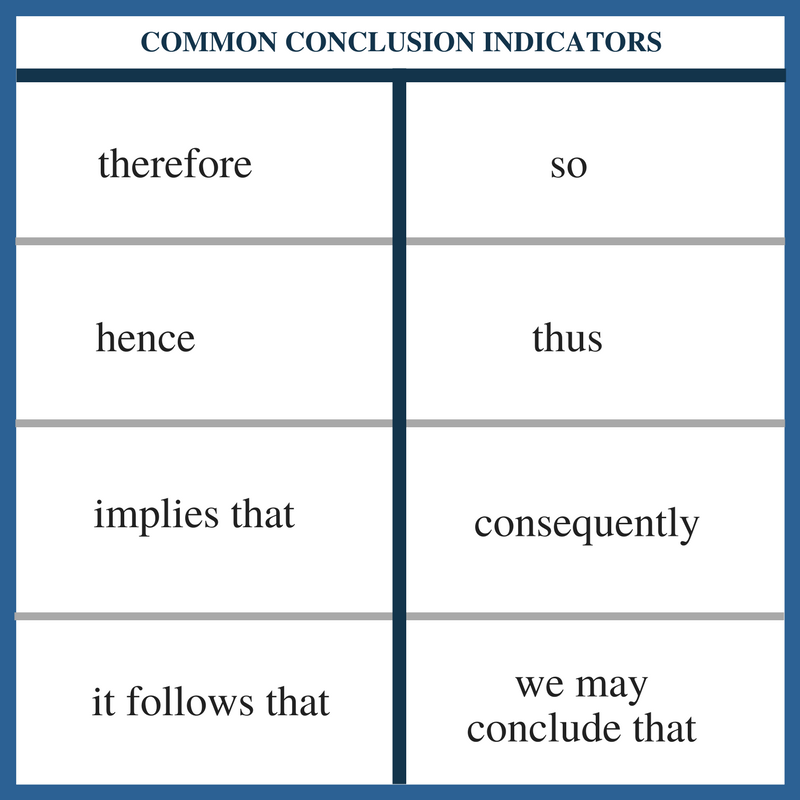

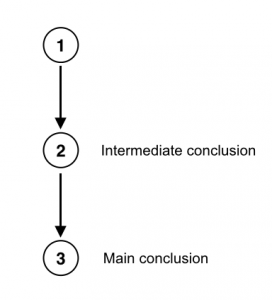

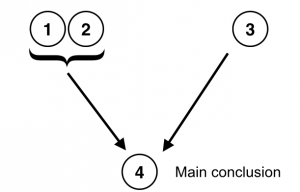

An argument can be defined as a complex symbolic structure where some parts, known as the premises, offer support to another part, the conclusion. Alternatively, an argument can be viewed as a complex speech act consisting of one or more acts of premising (which assert propositions in favor of the conclusion), an act of concluding, and a stated or implicit marker (“hence”, “therefore”) that indicates that the conclusion follows from the premises (Hitchcock 2007). [ 1 ] The relation of support between premises and conclusion can be cashed out in different ways: the premises may guarantee the truth of the conclusion, or make its truth more probable; the premises may imply the conclusion; the premises may make the conclusion more acceptable (or assertible).

For theoretical purposes, arguments may be considered as freestanding entities, abstracted from their contexts of use in actual human activities. But depending on one’s explanatory goals, there is also much to be gained from considering arguments as they in fact occur in human communicative practices. The term generally used for instances of exchange of arguments is argumentation . In what follows, the convention of using “argument” to refer to structures of premises and conclusion, and “argumentation” to refer to human practices and activities where arguments occur as communicative actions will be adopted.

Argumentation can be defined as the communicative activity of producing and exchanging reasons in order to support claims or defend/challenge positions, especially in situations of doubt or disagreement (Lewiński & Mohammed 2016). It is arguably best conceived as a kind of dialogue , even if one can also “argue” with oneself, in long speeches or in writing (in articles or books) for an intended but silent audience, or in groups rather than in dyads (Lewiński & Aakhus 2014). But argumentation is a special kind of dialogue: indeed, most of the dialogues we engage in are not instances of argumentation, for example when asking someone if they know what time it is, or when someone shares details about their vacation. Argumentation only occurs when, upon making a claim, someone receives a request for further support for the claim in the form of reasons, or estimates herself that further justification is required (Jackson & Jacobs 1980; Jackson, 2019). In such cases, dialogues of “giving and asking for reasons” ensue (Brandom, 1994; Bermejo Luque 2011). Since most of what we know we learn from others, argumentation seems to be an important mechanism to filter the information we receive, instead of accepting what others tell us uncritically (Sperber, Clément, et al. 2010).

The study of arguments and argumentation is also closely connected to the study of reasoning , understood as the process of reaching conclusions on the basis of careful, reflective consideration of the available information, i.e., by an examination of reasons . According to a widespread view, reasoning and argumentation are related (as both concern reasons) but fundamentally different phenomena: reasoning would belong to the mental realm of thinking—an individual inferring new information from the available information by means of careful consideration of reasons—whereas argumentation would belong to the public realm of the exchange of reasons, expressed in language or other symbolic media and intended for an audience. However, a number of authors have argued for a different view, namely that reasoning and argumentation are in fact two sides of the same coin, and that what is known as reasoning is by and large the internalization of practices of argumentation (MacKenzie 1989; Mercier & Sperber 2017; Mercier 2018). For the purposes of this entry, we can assume a close connection between reasoning and argumentation so that relevant research on reasoning can be suitably included in the discussions to come.

2. Types of Arguments

Arguments come in many kinds. In some of them, the truth of the premises is supposed to guarantee the truth of the conclusion, and these are known as deductive arguments. In others, the truth of the premises should make the truth of the conclusion more likely while not ensuring complete certainty; two well-known classes of such arguments are inductive and abductive arguments (a distinction introduced by Peirce, see entry on C.S. Peirce ). Unlike deduction, induction and abduction are thought to be ampliative: the conclusion goes beyond what is (logically) contained in the premises. Moreover, a type of argument that features prominently across different philosophical traditions, and yet does not fit neatly into any of the categories so far discussed, are analogical arguments. In this section, these four kinds of arguments are presented. The section closes with a discussion of fallacious arguments, that is, arguments that seem legitimate and “good”, but in fact are not. [ 2 ]

Valid deductive arguments are those where the truth of the premises necessitates the truth of the conclusion: the conclusion cannot but be true if the premises are true. Arguments having this property are said to be deductively valid . A valid argument whose premises are also true is said to be sound . Examples of valid deductive arguments are the familiar syllogisms, such as:

All humans are living beings. All living beings are mortal. Therefore, all humans are mortal.

In a deductively valid argument, the conclusion will be true in all situations where the premises are true, with no exceptions. A slightly more technical gloss of this idea goes as follows: in all possible worlds where the premises hold, the conclusion will also hold. This means that, if I know the premises of a deductively valid argument to be true of a given situation, then I can conclude with absolute certainty that the conclusion is also true of that situation. An important property typically associated with deductive arguments (but with exceptions, such as in relevant logic), and which differentiates them from inductive and abductive arguments, is the property of monotonicity : if premises A and B deductively imply conclusion C , then the addition of any arbitrary premise D will not invalidate the argument. In other words, if the argument “ A and B ; therefore C ” is deductively valid, then the argument “ A , B and D ; therefore C ” is equally deductively valid.

Deductive arguments are the objects of study of familiar logical systems such as (classical) propositional and predicate logic, as well as of subclassical systems such as intuitionistic and relevant logics (although in relevant logic the property of monotonicity does not hold, as it may lead to violations of criteria of relevance between premises and conclusion—see entry on relevance logic ). In each of these systems, the relation of logical consequence in question satisfies the property of necessary truth-preservation (see entry on logical consequence ). This is not surprising, as these systems were originally designed to capture arguments of a very specific kind, namely mathematical arguments (proofs), in the pioneering work of Frege, Russell, Hilbert, Gentzen, and others. Following a paradigm established in ancient Greek mathematics and famously captured in Euclid’s Elements , argumentative steps in mathematical proofs (in this tradition at least) must have the property of necessary truth preservation (Netz 1999). This paradigm remained influential for millennia, and still codifies what can be described as the “classical” conception of mathematical proof (Dutilh Novaes 2020a), even if practices of proof are ultimately also quite diverse. (In fact, there is much more to argumentation in mathematics than just deductive argumentation [Aberdein & Dove 2013].)

However, a number of philosophers have argued that deductive validity and necessary truth preservation in fact come apart. Some have reached this conclusion motivated by the familiar logical paradoxes such as the Liar or Curry’s paradox (Beall 2009; Field 2008; see entries on the Liar paradox and on Curry’s paradox ). Others have defended the idea that there are such things as contingent logical truths (Kaplan 1989; Nelson & Zalta 2012), which thus challenge the idea of necessary truth preservation. It has also been suggested that what is preserved in the transition from premises to conclusions in deductive arguments is in fact warrant or assertibility rather than truth (Restall 2004). Yet others, such as proponents of preservationist approaches to paraconsistent logic, posit that what is preserved by the deductive consequence relation is the coherence, or incoherence, of a set of premises (Schotch, Brown, & Jennings 2009; see entry on paraconsistent logic ). Nevertheless, it is fair to say that the view that deductive validity is to be understood primarily in terms of necessary truth preservation is still the received view.

Relatedly, there are a number of pressing philosophical issues pertaining to the justification of deduction, such as the exact nature of the necessity involved in deduction (metaphysical, logical, linguistic, epistemic; Shapiro 2005), and the possibility of offering a non-circular foundation for deduction (Dummett 1978). Furthermore, it is often remarked that the fact that a deductive argument is not ampliative may entail that it cannot be informative, which in turn would mean that its usefulness is quite limited; this problem has been described as “the scandal of deduction” (Sequoiah-Grayson 2008).

Be that as it may, deductive arguments have occupied a special place in philosophy and the sciences, ever since Aristotle presented the first fully-fledged theory of deductive argumentation and reasoning in the Prior Analytics (and the corresponding theory of scientific demonstration in the Posterior Analytics ; see Historical Supplement ). The fascination for deductive arguments is understandable, given their allure of certainty and indubitability. The more geometrico (a phrase introduced by Spinoza to describe the argumentative structure of his Ethics as following “a geometrical style”—see entry on Spinoza ) has been influential in many fields other than mathematics. However, the focus on deductive arguments at the expense of other types of arguments has arguably skewed investigations on argument and argumentation too much in one specific direction (see (Bermejo-Luque 2020) for a critique of deductivism in the study of argumentation).

In recent decades, the view that everyday reasoning and argumentation by and large do not follow the canons of deductive argumentation has been gaining traction. In psychology of reasoning, Oaksford and Chater were the first to argue already in the 1980s that human reasoning “in the wild” is essentially probabilistic, following the basic canons of Bayesian probabilities (Oaksford & Chater 2018; Elqayam 2018; see section 5.3 below). Computer scientists and artificial intelligence researchers have also developed a strong interest in non-monotonic reasoning and argumentation (Reiter 1980), recognizing that, outside specific scientific contexts, human reasoning tends to be deeply defeasible (Pollock 1987; see entries on non-monotonic logic and defeasible reasoning ). Thus seen, deductive argumentation might be considered as the exception rather than the rule in human argumentative practices taken as a whole (Dutilh Novaes 2020a). But there are others, especially philosophers, who still maintain that the use of deductive reasoning and argumentation is widespread and extends beyond niches of specialists (Shapiro 2014; Williamson 2018).

Inductive arguments are arguments where observations about past instances and regularities lead to conclusions about future instances and general principles. For example, the observation that the sun has risen in the east every single day until now leads to the conclusion that it will rise in the east tomorrow, and to the general principle “the sun always rises in the east”. Generally speaking, inductive arguments are based on statistical frequencies, which then lead to generalizations beyond the sample of cases initially under consideration: from the observed to the unobserved. In a good, i.e., cogent , inductive argument, the truth of the premises provides some degree of support for the truth of the conclusion. In contrast with a deductively valid argument, in an inductive argument the degree of support will never be maximal, as there is always the possibility of the conclusion being false given the truth of the premises. A gloss in terms of possible worlds might be that, while in a deductively valid argument the conclusion will hold in all possible worlds where the premises hold, in a good inductive argument the conclusion will hold in a significant proportion of the possible worlds where the premises hold. The proportion of such worlds may give a measure of the strength of support of the premises for the conclusion (see entry on inductive logic ).

Inductive arguments have been recognized and used in science and elsewhere for millennia. The concept of induction ( epagoge in Greek) was understood by Aristotle as a progression from particulars to a universal, and figured prominently both in his conception of the scientific method and in dialectical practices (see entry on Aristotle’s logic, section 3.1 ). However, a deductivist conception of the scientific method remained overall more influential in Aristotelian traditions, inspired by the theory of scientific demonstration of the Posterior Analytics . It is only with the so-called “scientific revolution” of the early modern period that experiments and observation of individual cases became one of the pillars of scientific methodology, a transition that is strongly associated with the figure of Francis Bacon (1561–1626; see entry on Francis Bacon ).

Inductive inferences/arguments are ubiquitous both in science and in everyday life, and for the most part quite reliable. The functioning of the world around us seems to display a fair amount of statistical regularity, and this is referred to as the “Uniformity Principle” in the literature on the problem of induction (to be discussed shortly). Moreover, it has been argued that generalizing from previously observed frequencies is the most basic principle of human cognition (Clark 2016).

However, it has long been recognized that inductive inferences/arguments are not unproblematic. Hume famously offered the first influential formulation of what became known as “the problem of induction” in his Treatise of Human Nature (see entries on David Hume and on the problem of induction ; Howson 2000). Hume raises the question of what grounds the correctness of inductive inferences/arguments, and posits that there must be an argument establishing the validity of the Uniformity Principle for inductive inferences to be truly justified. He goes on to argue that this argument cannot be deductive, as it is not inconceivable that the course of nature may change. But it cannot be probable either, as probable arguments already presuppose the validity of the Uniformity Principle; circularity would ensue. Since these are the only two options, he concludes that the Uniformity Principle cannot be established by rational argument, and hence that induction cannot be justified.

A more recent influential critique of inductive arguments is the one offered in (Harman 1965). Harman argues that either enumerative induction is not always warranted, or it is always warranted but constitutes an uninteresting special case of the more general category of inference to the best explanation (see next section). The upshot is that, for Harman, induction should not be considered a warranted form of inference in its own right.

Given the centrality of induction for scientific practice, there have been numerous attempts to respond to the critics of induction, with various degrees of success. Among those, an influential recent response to the problem of induction is Norton’s material theory of induction (Norton 2003). But the problem has not prevented scientists and laypeople alike from continuing to use induction widely. More recently, the use of statistical frequencies for social categories to draw conclusions about specific individuals has become a matter of contention, both at the individual level (see entry on implicit bias ) and at the institutional level (e.g., the use of predictive algorithms for law enforcement [Jorgensen Bolinger 2021]). These debates can be seen as reoccurrences of Hume’s problem of induction, now in the domain of social rather than of natural phenomena.

An abductive argument is one where, from the observation of a few relevant facts, a conclusion is drawn as to what could possibly explain the occurrence of these facts (see entry on abduction ). Abduction is widely thought to be ubiquitous both in science and in everyday life, as well as in other specific domains such as the law, medical diagnosis, and explainable artificial intelligence (Josephson & Josephson 1994). Indeed, a good example of abduction is the closing argument by a prosecutor in a court of law who, after summarizing the available evidence, concludes that the most plausible explanation for it is that the defendant must have committed the crime they are accused of.

Like induction, and unlike deduction, abduction is not necessarily truth-preserving: in the example above, it is still possible that the defendant is not guilty after all, and that some other, unexpected phenomena caused the evidence to emerge. But abduction is significantly different from induction in that it does not only concern the generalization of prior observation for prediction (though it may also involve statistical data): rather, abduction is often backward-looking in that it seeks to explain something that has already happened. The key notion is that of bringing together apparently independent phenomena or events as explanatorily and/or causally connected to each other, something that is absent from a purely inductive argument that only appeals to observed frequencies. Cognitively, abduction taps into the well-known human tendency to seek (causal) explanations for phenomena (Keil 2006).

As noted, deduction and induction have been recognized as important classes of arguments for millennia; the concept of abduction is by comparison a latecomer. It is important to notice though that explanatory arguments as such are not latecomers; indeed, Aristotle’s very conception of scientific demonstration is based on the concept of explaining causes (see entry on Aristotle ). What is recent is the conceptualization of abduction as a special class of arguments, and the term itself. The term was introduced by Peirce as a third class of inferences distinct from deduction and induction: for Peirce, abduction is understood as the process of forming explanatory hypotheses, thus leading to new ideas and concepts (whereas for him deduction and induction could not lead to new ideas or theories; see the entry on Peirce ). Thus seen, abduction pertains to contexts of discovery , in which case it is not clear that it corresponds to instances of arguments, properly speaking. In its modern meaning, however, abduction pertains to contexts of justification , and thus to speak of abductive arguments becomes appropriate. An abductive argument is now typically understood as an inference to the best explanation (Lipton 1971 [2003]), although some authors contend that there are good reasons to distinguish the two concepts (Campos 2011).

While the main ideas behind abduction may seem simple enough, cashing out more precisely how exactly abduction works is a complex matter (see entry on abduction ). Moreover, it is not clear that abductive arguments are always or even generally reliable and cogent. Humans seem to have a tendency to overshoot in their quest for causal explanations, and often look for simplicity where there is none to be found (Lombrozo 2007; but see Sober 2015 on the significance of parsimony in scientific reasoning). There are also a number of philosophical worries pertaining to the justification of abduction, especially in scientific contexts; one influential critique of abduction/inference to the best explanation is the one articulated by van Fraassen (Fraassen 1989). A frequent concern pertains to the connection between explanatory superiority and truth: are we entitled to conclude that the conclusion of an abductive argument is true solely on the basis of it being a good (or even the best) explanation for the phenomena in question? It seems that no amount of philosophical a priori theorizing will provide justification for the leap from explanatory superiority to truth. Instead, defenders of abduction tend to offer empirical arguments showing that abduction tends to be a reliable rule of inference. In this sense, abduction and induction are comparable: they are widely used, grounded in very basic human cognitive tendencies, but they give rise to a number of difficult philosophical problems.

Arguments by analogy are based on the idea that, if two things are similar, what is true of one of them is likely to be true of the other as well (see entry on analogy and analogical reasoning ). Analogical arguments are widely used across different domains of human activity, for example in legal contexts (see entry on precedent and analogy in legal reasoning ). As an example, take an argument for the wrongness of farming non-human animals for food consumption: if an alien species farmed humans for food, that would be wrong; so, by analogy, it is wrong for us humans to farm non-human animals for food. The general idea is captured in the following schema (adapted from the entry on analogy and analogical reasoning ; S is the source domain and T the target domain of the analogy):

- S is similar to T in certain (known) respects.

- S has some further feature Q .

- Therefore, T also has the feature Q , or some feature Q * similar to Q .

The first premise establishes the analogy between two situations, objects, phenomena etc. The second premise states that the source domain has a given property. The conclusion is then that the target domain also has this property, or a suitable counterpart thereof. While informative, this schema does not differentiate between good and bad analogical arguments, and so does not offer much by way of explaining what grounds (good) analogical arguments. Indeed, contentious cases usually pertain to premise 1, and in particular to whether S and T are sufficiently similar in a way that is relevant for having or not having feature Q .

Analogical arguments are widely present in all known philosophical traditions, including three major ancient traditions: Greek, Chinese, and Indian (see Historical Supplement ). Analogies abound in ancient Greek philosophical texts, for example in Plato’s dialogues. In the Gorgias , for instance, the knack of rhetoric is compared to pastry-baking—seductive but ultimately unhealthy—whereas philosophy would correspond to medicine—potentially painful and unpleasant but good for the soul/body (Irani 2017). Aristotle discussed analogy extensively in the Prior Analytics and in the Topics (see section 3.2 of the entry on analogy and analogical reasoning ). In ancient Chinese philosophy, analogy occupies a very prominent position; indeed, it is perhaps the main form of argumentation for Chinese thinkers. Mohist thinkers were particularly interested in analogical arguments (see entries on logic and language in early Chinese philosophy , Mohism and the Mohist canons ). In the Latin medieval tradition too analogy received sustained attention, in particular in the domains of logic, theology and metaphysics (see entry on medieval theories of analogy ).

Analogical arguments continue to occupy a central position in philosophical discussions, and a number of the most prominent philosophical arguments of the last decades are analogical arguments, e.g., Jarvis Thomson’s violinist argument purportedly showing the permissibility of abortion (Thomson 1971), and Searle’s Chinese Room argument purportedly showing that computers cannot display real understanding (see entry on the Chinese Room argument ). (Notice that these two arguments are often described as thought experiments [see entry on thought experiments ], but thought experiments are often based on analogical principles when seeking to make a point that transcends the thought experiment as such.) The Achilles’ heel of analogical arguments can be illustrated by these two examples: both arguments have been criticized on the grounds that the purported similarity between the source and the target domains is not sufficient to extrapolate the property of the source domain (the permissibility of disconnecting from the violinist; the absence of understanding in the Chinese room) to the target domain (abortion; digital computers and artificial intelligence).

In sum, while analogical arguments in general perhaps confer a lesser degree of conviction than the other three kinds of arguments discussed, they are widely used both in professional circles and in everyday life. They have rightly attracted a fair amount of attention from scholars in different disciplines, and remain an important object of study (see entry on analogy and analogical reasoning ).

One of the most extensively studied types of arguments throughout the centuries are, perhaps surprisingly, arguments that appear legitimate but are not, known as fallacious arguments . From early on, the investigation of such arguments occupied a prominent position in Aristotelian logical traditions, inspired in particular by his book Sophistical Refutations (see Historical Supplement ). The thought is that, to argue well, it is not sufficient to be able to produce and recognize good arguments; it is equally (or perhaps even more) important to be able to recognize bad arguments by others, and to avoid producing bad arguments oneself. This is particularly true of the tricky cases, namely arguments that appear legitimate but are not, i.e., fallacies.

Some well-know types of fallacies include (see entry on fallacies for a more extensive discussion):

- The fallacy of equivocation, which occurs when an arguer exploits the ambiguity of a term or phrase which has occurred at least twice in an argument to draw an unwarranted conclusion.

- The fallacy of begging the question, when one of the premises and the conclusion of an argument are the same proposition, but differently formulated.

- The fallacy of appeal to authority, when a claim is supported by reference to an authority instead of offering reasons to support it.

- The ad hominem fallacy, which involves bringing negative aspects of an arguer, or their situation, to argue against the view they are advancing.

- The fallacy of faulty analogy, when an analogy is used as an argument but there is not sufficient relevant similarity between the source domain and the target domain (as discussed above).

Beyond their (presumed?) usefulness in teaching argumentative skills, the literature on fallacies raises a number of important philosophical discussions, such as: What determines when an argument is fallacious or rather a legitimate argument? (See section 4.3 below on Bayesian accounts of fallacies) What causes certain arguments to be fallacious? Is the focus on fallacies a useful approach to arguments at all? (Massey 1981) Despite the occasional criticism, the concept of fallacies remains central in the study of arguments and argumentation.

3. Types of Argumentation

Just as there are different types of arguments, there are different types of argumentative situations, depending on the communicative goals of the persons involved and background conditions. Argumentation may occur when people are trying to reach consensus in a situation of dissent, but it may also occur when scientists discuss their findings with each other (to name but two examples). Specific rules of argumentative engagement may vary depending on these different types of argumentation.

A related point extensively discussed in the recent literature pertains to the function(s) of argumentation. [ 3 ] What’s the point of arguing? While it is often recognized that argumentation may have multiple functions, different authors tend to emphasize specific functions for argumentation at the expense of others. This section offers an overview of discussions on types of argumentation and its functions, demonstrating that argumentation is a multifaceted phenomenon that has different applications in different circumstances.

A question that has received much attention in the literature of the past decades pertains to whether the activity of argumentation is primarily adversarial or primarily cooperative. This question in fact corresponds to two sub-questions: the descriptive question of whether instances of argumentation are on the whole primarily adversarial or cooperative; and the normative question of whether argumentation should be (primarily) adversarial or cooperative. A number of authors have answered “adversarial” to the descriptive question and “cooperative” to the normative question, thus identifying a discrepancy between practices and normative ideals that must be remedied (or so they claim; Cohen 1995).

A case in point: recently, a number of far-right Internet personalities have advocated the idea that argumentation can be used to overpower one’s opponents, as described in the book The Art of the Argument: Western Civilization’s Last Stand (2017) by the white supremacist S. Molyneux. Such aggressive practices reflect a vision of argumentation as a kind of competition or battle, where the goal is to “score points” and “beat the opponent”. Authors who have criticized (overly) adversarial practices of argumentation include (Moulton 1983; Gilbert 1994; Rooney 2012; Hundleby 2013; Bailin & Battersby 2016). Many (but not all) of these authors formulated their criticism specifically from a feminist perspective (see entry on feminist perspectives on argumentation ).

Feminist critiques of adversarial argumentation challenge ideals of argumentation as a form of competition, where masculine-coded values of aggression and violence prevail (Kidd 2020). For these authors, such ideals encourage argumentative performances where excessive use of forcefulness is on display. Instances of aggressive argumentation in turn have a number of problematic consequences: epistemic consequences—the pursuit of truth is not best served by adversarial argumentation—as well as moral/ethical/political consequences—these practices exclude a number of people from participating in argumentative encounters, namely those for whom displays of aggression do not constitute socially acceptable behavior (women and other socially disadvantaged groups in particular). These authors defend alternative conceptions of argumentation as a cooperative, nurturing activity (Gilbert 1994; Bailin & Battersby 2016), which are traditionally feminine-coded values. Crucially, they view adversarial conceptions of argumentation as optional , maintaining that the alternatives are equally legitimate and that cooperative conceptions should be adopted and cultivated.

By contrast, others have argued that adversariality, when suitably understood, can be seen as an integral and in fact desirable component of argumentation (Govier 1999; Aikin 2011; Casey 2020; but notice that these authors each develop different accounts of adversariality in argumentation). Such authors answer “adversarial” both to the descriptive and to the normative questions stated above. One overall theme is the need to draw a distinction between (excessive) aggressiveness and adversariality as such. Govier, for example, distinguishes between ancillary (negative) adversariality and minimal adversariality (Govier 1999). The thought is that, while the feminist critique of excessive aggression in argumentation is well taken, adversariality conceived and practiced in different ways need not have the detrimental consequences of more extreme versions of belligerent argumentation. Moreover, for these authors, adversariality in argumentation is simply not optional: it is an intrinsic feature of argumentative practices, but these practices also require a background of cooperation and agreement regarding, e.g., the accepted rules of inference.

But ultimately, the presumed opposition between adversarial and cooperative conceptions of argumentation may well be merely apparent. It may be argued for example that actual argumentative encounters ought to be adversarial or cooperative to different degrees, as different types of argumentation are required for different situations (Dutilh Novaes forthcoming). Indeed, perhaps we should not look for a one-fits-all model of how argumentation ought to be conducted across different contexts and situation, given the diversity of uses of argumentation.

We speak of argumentation as an epistemic practice when we take its primary purpose to be that of improving our beliefs and increasing knowledge, or of fostering understanding. To engage in argumentation can be a way to acquire more accurate beliefs: by examining critically reasons for and against a given position, we would be able to weed out weaker, poorly justified beliefs (likely to be false) and end up with stronger, suitably justified beliefs (likely to be true). From this perspective, the goal of engaging in argumentation is to learn , i.e., to improve one’s epistemic position (as opposed to argumentation “to win” (Fisher & Keil 2016)). Indeed, argumentation is often said to be truth-conducive (Betz 2013).

The idea that argumentation can be an epistemically beneficial process is as old as philosophy itself. In every major historical philosophical tradition, argumentation is viewed as an essential component of philosophical reflection precisely because it may be used to aim at the truth (indeed this is the core of Plato’s critique of the Sophists and their excessive focus on persuasion at the expense of truth (Irani 2017; see Historical Supplement ). Recent proponents of an epistemological approach to argumentation include (Goldman 2004; Lumer 2005; Biro & Siegel 2006). Alvin Goldman captures this general idea in the following terms:

Norms of good argumentation are substantially dedicated to the promotion of truthful speech and the exposure of falsehood, whether intentional or unintentional. […] Norms of good argumentation are part of a practice to encourage the exchange of truths through sincere, non-negligent, and mutually corrective speech. (Goldman 1994: 30)

Of course, it is at least in theory possible to engage in argumentation with oneself along these lines, solitarily weighing the pros and cons of a position. But a number of philosophers, most notably John Stuart Mill, maintain that interpersonal argumentative situations, involving people who truly disagree with each other, work best to realize the epistemic potential of argumentation to improve our beliefs (a point he developed in On Liberty (1859; see entry on John Stuart Mill ). When our ideas are challenged by engagement with those who disagree with us, we are forced to consider our own beliefs more thoroughly and critically. The result is that the remaining beliefs, those that have survived critical challenge, will be better grounded than those we held before such encounters. Dissenters thus force us to stay epistemically alert instead of becoming too comfortable with existing, entrenched beliefs. On this conception, arguers cooperate with each other precisely by being adversarial, i.e., by adopting a critical stance towards the positions one disagrees with.

The view that argumentation aims at epistemic improvement is in many senses appealing, but it is doubtful that it reflects the actual outcomes of argumentation in many real-life situations. Indeed, it seems that, more often than not, we are not Millians when arguing: we do not tend to engage with dissenting opinions with an open mind. Indeed, there is quite some evidence suggesting that arguments are in fact not a very efficient means to change minds in most real-life situations (Gordon-Smith 2019). People typically do not like to change their minds about firmly entrenched beliefs, and so when confronted with arguments or evidence that contradict these beliefs, they tend to either look away or to discredit the source of the argument as unreliable (Dutilh Novaes 2020c)—a phenomenon also known as “confirmation bias” (Nickerson 1998).

In particular, arguments that threaten our core beliefs and our sense of belonging to a group (e.g., political beliefs) typically trigger all kinds of motivated reasoning (Taber & Lodge 2006; Kahan 2017) whereby one outright rejects those arguments without properly engaging with their content. Relatedly, when choosing among a vast supply of options, people tend to gravitate towards content and sources that confirm their existing opinions, thus giving rise to so-called “echo chambers” and “epistemic bubbles” (Nguyen 2020). Furthermore, some arguments can be deceptively convincing in that they look valid but are not (Tindale 2007; see entry on fallacies ). Because most of us are arguably not very good at spotting fallacious arguments, especially if they are arguments that lend support to the beliefs we already hold, engaging in argumentation may in fact decrease the accuracy of our beliefs by persuading us of false conclusions with incorrect arguments (Fantl 2018).

In sum, despite the optimism of Mill and many others, it seems that engaging in argumentation will not automatically improve our beliefs (even if this may occur in some circumstances). [ 4 ] However, it may still be argued that an epistemological approach to argumentation can serve the purpose of providing a normative ideal for argumentative practices, even if it is not always a descriptively accurate account of these practices in the messy real world. Moreover, at least some concrete instances of argumentation, in particular argumentation in science (see section 4.5 below) seem to offer successful examples of epistemic-oriented argumentative practices.

Another important strand in the literature on argumentation are theories that view consensus as the primary goal of argumentative processes: to eliminate or resolve a difference of (expressed) opinion. The tradition of pragma-dialectics is a prominent recent exponent of this strand (Eemeren & Grootendorst 2004). These consensus-oriented approaches are motivated by the social complexity of human life, and the attribution of a role of social coordination to argumentation. Because humans are social animals who must often cooperate with other humans to successfully accomplish certain tasks, they must have mechanisms to align their beliefs and intentions, and subsequently their actions (Tomasello 2014). The thought is that argumentation would be a particularly suitable mechanism for such alignment, as an exchange of reasons would make it more likely that differences of opinion would decrease (Norman 2016). This may happen precisely because argumentation would be a good way to track truths and avoid falsehoods, as discussed in the previous section; by being involved in the same epistemic process of exchanging reasons, the participants in an argumentative situation would all come to converge towards the truth, and thus the upshot would be that they also come to agree with each other. However, consensus-oriented views need not presuppose that argumentation is truth-conducive: the ultimate goal of such instances of argumentation is that of social coordination, and for this tracking truth is not a requirement (Patterson 2011).

In particular, the very notion of deliberative democracy is viewed as resting crucially on argumentative practices that aim for consensus (Fishkin 2016; see entry on democracy ). (For present purposes, “deliberation” and “argumentation” can be treated as roughly synonymous). In a deliberative democracy, for a decision to be legitimate, it must be preceded by authentic public deliberation—a discussion of the pros and cons of the different options—not merely the aggregation of preferences that occurs in voting. Moreover, in democratic deliberation, when full consensus does not emerge, the parties involved may opt for a compromise solution, e.g., a coalition-based political system.

A prominent theorist of deliberative democracy thus understood is Jürgen Habermas, whose “discourse theory of law and democracy” relies heavily on practices of political justification and argumentation taking place in what he calls “the public sphere” (Habermas 1992 [1996]; 1981 [1984]; see entry on Habermas ). He starts from the idea that politics allows for the collective organization of people’s lives, including the common rules they will live by. Political argumentation is a form of communicative practice, so general assumptions for communicative practices in general apply. However, additional assumptions apply as well (Olson 2011 [2014]). In particular, deliberating participants must accept that anyone can participate in these discursive practices (democratic deliberation should be inclusive), and that anyone can introduce and challenge claims that are made in the public sphere (democratic deliberation should be free). They must also see one another as having equal status, at least for the purposes of deliberation (democratic deliberation should be equal). In turn, critics of Habermas’s account view it as unrealistic, as it presupposes an ideal situation where all citizens are treated equally and engage in public debates in good faith (Mouffe 1999; Geuss 2019).

More generally, it seems that it is only under quite specific conditions that argumentation reliably leads to consensus (as also suggested by formal modeling of argumentative situations (Betz 2013; Olsson 2013; Mäs & Flache 2013)). Consensus-oriented argumentation seems to work well in cooperative contexts, but not so much in situations of conflict (Dutilh Novaes forthcoming). In particular, the discussing parties must already have a significant amount of background agreement—especially agreement on what counts as a legitimate argument or compelling evidence—for argumentation and deliberation to lead to consensus. Especially in situations of deep disagreement (Fogelin 1985), it seems that the potential of argumentation to lead to consensus is quite limited. Instead, in many real-life situations, argumentation often leads to the opposite result; people disagree with each other even more after engaging in argumentation (Sunstein 2002). This is the well-documented phenomenon of group polarization , which occurs when an initial position or tendency of individual members of a group becomes more extreme after group discussion (Isenberg 1986).

In fact, it may be argued that argumentation will often create or exacerbate conflict and adversariality, rather than leading to the resolution of differences of opinions. Furthermore, a focus on consensus may end up reinforcing and perpetuating existing unequal power relations in a society.

In an unjust society, what purports to be a cooperative exchange of reasons really perpetuates patterns of oppression. (Goodwin 2007: 77)

This general point has been made by a number of political thinkers (e.g., Young 2000), who have highlighted the exclusionary implications of consensus-oriented political deliberation. The upshot is that consensus may not only be an unrealistic goal for argumentation; it may not even be a desirable goal for argumentation in a number of situations (e.g., when there is great power imbalance). Despite these concerns, the view that the primary goal of argumentation is to aim for consensus remains influential in the literature.

Finally, a number of authors have attributed to argumentation the potential to manage (pre-existing) conflict. In a sense, the consensus-oriented view of argumentation just discussed is a special case of conflict management argumentation, based on the assumption that the best way to manage conflict and disagreement is to aim for consensus and thus eliminate conflict. But conflict can be managed in different ways, not all of them leading to consensus; indeed, some authors maintain that argumentation may help mitigate conflict even when the explicit aim is not that of reaching consensus. Importantly, authors who identify conflict management (or variations thereof) as a function for argumentation differ in their overall appreciation of the value of argumentation: some take it to be at best futile and at worst destructive, [ 5 ] while others attribute a more positive role to argumentation in conflict management.

To this category also belong the conceptualizations of argumentation-as-war discussed (and criticized) by a number of authors (Cohen 1995; Bailin & Battersby 2016); in such cases, conflict is not so much managed but rather enacted (and possibly exacerbated) by means of argumentation. Thus seen, the function of argumentation would not be fundamentally different from the function of organized competitive activities such as sports or even war (with suitable rules of engagement; Aikin 2011).

When conflict emerges, people have various options: they may choose not to engage and instead prefer to flee; they may go into full-blown fighting mode, which may include physical aggression; or they may opt for approaches somewhere in between the fight-or-flee extremes of the spectrum. Argumentation can be plausibly classified as an intermediary response:

[A]rgument literally is a form of pacifism—we are using words instead of swords to settle our disputes. With argument, we settle our disputes in ways that are most respectful of those who disagree—we do not buy them off, we do not threaten them, and we do not beat them into submission. Instead, we give them reasons that bear on the truth or falsity of their beliefs. However adversarial argument may be, it isn’t bombing. […] argument is a pacifistic replacement for truly violent solutions to disagreements…. (Aikin 2011: 256)

This is not to say that argumentation will always or even typically be the best approach to handle conflict and disagreement; the point is rather that argumentation at least has the potential to do so, provided that the background conditions are suitable and that provisions to mitigate escalation are in place (Aikin 2011). Versions of this view can be found in the work of proponents of agonistic conceptions of democracy and political deliberation (Wenman 2013; see entry on feminist political philosophy ). For agonist thinkers, conflict and strife are inevitable features of human lives, and so cannot be eliminated; but they can be managed. One of them is Chantal Mouffe (Mouffe 2000), for whom democratic practices, including argumentation/deliberation, can serve to contain hostility and transform it into more constructive forms of contest. However, it is far from obvious that argumentation by itself will suffice to manage conflict; typically, other kinds of intervention must be involved (Young 2000), as the risk of argumentation being used to exercise power rather than as a tool to manage conflict always looms large (van Laar & Krabbe 2019).

From these observations on different types of argumentation, a pluralistic picture emerges: argumentation, understood as the exchange of reasons to justify claims, seems to have different applications in different situations. However, it is not clear that some of the goals often attributed to argumentation such as epistemic improvement and reaching consensus can in fact be reliably achieved in many real life situations. Does this mean that argumentation is useless and futile? Not necessarily, but it may mean that engaging in argumentation will not always be the optimal response in a number of contexts.

4. Argumentation Across Fields of Inquiry and Social Practices

Argumentation is practiced and studied in many fields of inquiry; philosophers interested in argumentation have much to benefit from engaging with these bodies of research as well.

To understand the emergence of argumentation theory as a specific field of research in the twentieth century, a brief discussion of preceding events is necessary. In the nineteenth century, a number of textbooks aiming to improve everyday reasoning via public education emphasized logical and rhetorical concerns, such as those by Richard Whately (see entry on fallacies ). As noted in section 3.2 , John Stuart Mill also had a keen interest in argumentation and its role in public discourse (Mill 1859), as well as an interest in logic and reasoning (see entries on Mill and on fallacies ). But with the advent of mathematical logic in the final decades of the nineteenth century, logic and the study of ordinary, everyday argumentation came apart, as logicians such as Frege, Hilbert, Russell etc. were primarily interested in mathematical reasoning and argumentation. As a result, their logical systems are not particularly suitable to study everyday argumentation, as this is simply not what they were designed to do. [ 6 ]

Nevertheless, in the twentieth century a number of authors took inspiration from developments in formal logic and expanded the use of logical tools to the analysis of ordinary argumentation. A pioneer in this tradition is Susan Stebbing, who wrote what can be seen as the first textbook in analytic philosophy, and then went on to write a number of books aimed at a general audience addressing everyday and public discourse from a philosophical/logical perspective (see entry on Susan Stebbing ). Her 1939 book Thinking to Some Purpose , which can be considered as one of the first textbooks in critical thinking, was widely read at the time, but did not become particularly influential for the development of argumentation theory in the decades to follow.

By contrast, Stephen Toulmin’s 1958 book The Uses of Argument has been tremendously influential in a wide range of fields, including critical thinking education, rhetoric, speech communication, and computer science (perhaps even more so than in Toulmin’s own original field, philosophy). Toulmin’s aim was to criticize the assumption (widely held by Anglo-American philosophers at the time) that any significant argument can be formulated in purely formal, deductive terms, using the formal logical systems that had emerged in the preceding decades (see (Eemeren, Garssen, et al. 2014: ch. 4). While this critique was met with much hostility among fellow philosophers, it eventually gave rise to an alternative way of approaching argumentation, which is often described as “informal logic” (see entry on informal logic ). This approach seeks to engage and analyze instances of argumentation in everyday life; it recognizes that, while useful, the tools of deductive logic alone do not suffice to investigate argumentation in all its complexity and pragmatic import. In a similar vein, Charles Hamblin’s 1970 book Fallacies reinvigorated the study of fallacies in the context of argumentation by re-emphasizing (following Aristotle) the importance of a dialectical-dialogical background when reflecting on fallacies in argumentation (see entry on fallacies ).

Around the same time as Toulmin, Chaïm Perelman and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca were developing an approach to argumentation that emphasized its persuasive component. To this end, they turned to classical theories of rhetoric, and adapted them to give rise to what they described as the “New Rhetoric”. Their book Traité de l’argumentation: La nouvelle rhétorique was published in 1958 in French, and translated into English in 1969. Its key idea:

since argumentation aims at securing the adherence of those to whom it is addressed, it is, in its entirety, relative to the audience to be influenced. (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca 1958 [1969: 19])

They introduced the influential distinction between universal and particular audiences: while every argument is directed at a specific individual or group, the concept of a universal audience serves as a normative ideal encapsulating shared standards of agreement on what counts as legitimate argumentation (see Eemeren, Garssen, et al. 2014: ch. 5).

The work of these pioneers provided the foundations for subsequent research in argumentation theory. One approach that became influential in the following decades is the pragma-dialectics tradition developed by Frans van Eemeren and Rob Grootendorst (Eemeren & Grootendorst 1984, 2004). They also founded the journal Argumentation , one of the flagship journals in argumentation theory. Pragma-dialectics was developed to study argumentation as a discourse activity, a complex speech act that occurs as part of interactional linguistic activities with specific communicative goals (“pragma” refers to the functional perspective of goals, and “dialectic” to the interactive component). For these authors, argumentative discourse is primarily directed at the reasonable resolution of a difference of opinion. Pragma-dialectics has a descriptive as well as a normative component, thus offering tools both for the analysis of concrete instances of argumentation and for the evaluation of argumentation correctness and success (see Eemeren, Garssen, et al. 2014: ch. 10).

Another leading author in argumentation theory is Douglas Walton, who pioneered the argument schemes approach to argumentation that borrows tools from formal logic but expands them so as to treat a wider range of arguments than those covered by traditional logical systems (Walton, Reed, & Macagno 2008). Walton also formulated an influential account of argumentation in dialogue in collaboration with Erik Krabbe (Walton & Krabbe 1995). Ralph Johnson and Anthony Blair further helped to consolidate the field of argumentation theory and informal logic by founding the Centre for Research in Reasoning, Argumentation, and Rhetoric in Windsor (Ontario, Canada), and by initiating the journal Informal Logic . Their textbook Logical Self-Defense (Johnson & Blair 1977) has also been particularly influential.

The study of argumentation within computer science and artificial intelligence is a thriving field of research, with dedicated journals such as Argument and Computation and regular conference series such as COMMA (International Conference on Computational Models of Argument; see Rahwan & Simari 2009 and Eemeren, Garssen, et al. 2014: ch. 11 for overviews).

The historical roots of argumentation research in artificial intelligence can be traced back to work on non-monotonic logics (see entry on non-monotonic logics ) and defeasible reasoning (see entry on defeasible reasoning ). Since then, three main different perspectives have emerged (Eemeren, Garssen, et al. 2014: ch. 11): the theoretical systems perspective, where the focus is on theoretical and formal models of argumentation (following the tradition of philosophical and formal logic); the artificial systems perspective, where the aim is to build computer programs that model or support argumentative tasks, for instance, in online dialogue games or in expert systems; the natural systems perspective, which investigates argumentation in its natural form with the help of computational tools (e.g., argumentation mining [Peldszus & Stede 2013; Habernal & Gurevych 2017], where computational methods are used to identify argumentative structures in large corpora of texts).

An influential approach in this research tradition is that of abstract argumentation frameworks , initiated by the pioneering work of Dung (1995). Before that, argumentation in AI was studied mostly under the inspiration of concepts coming from informal logic such as argumentation schemes, context, stages of dialogues and argument moves. By contrast, the key notion in the framework proposed by Dung is that of argument attack , understood as an abstract formal relation roughly intended to capture the idea that it is possible to challenge an argument by means of another argument (assertions are understood as a special case of arguments with zero premises). Arguments can then be represented in networks of attacks and defenses: an argument A can attack an argument B , and B in turn may attack further arguments C and D (the connection with the notion of defeaters is a natural one, which Dung also addresses).

Besides abstract argumentation, three other important lines of research in AI are: the (internal) structure of arguments; argumentation in multi-agent systems; applications to specific tasks and domains (Rahwan & Siwari 2009). The structural approach investigates formally features such as argument strength/force (e.g., a conclusive argument is stronger than a defeasible argument), argument schemes (Bex, Prakken, Reed, & Walton 2003) etc. Argumentation in multi-agent systems is a thriving subfield with its own dedicated conference series (ArgMAS), based on the recognition that argumentation is a particularly suitable vehicle to facilitate interaction in the artificial environments studied by AI researchers working on multi-agent systems (see a special issue of the journal Argument & Computation [Atkinson, Cerutti, et al. 2016]). Finally, computational approaches in argumentation have also thrived with respect to specific domains and applications, such as legal argumentation (Prakken & Sartor 2015). Recently, as a reaction to the machine-learning paradigm, the idea of explainable AI has gotten traction, and the concept of argumentation is thought to play a fundamental role for explainable AI (Sklar & Azhar 2018).

Argumentation is also an important topic of investigation within cognitive science and psychology. Researchers in these fields are predominantly interested in the descriptive question of how people in fact engage in argumentation, rather than in the normative question of how they ought to do it (although some of them have also drawn normative conclusions, e.g., Hahn & Oaksford 2006; Hahn & Hornikx, 2016). Controlled experiments are one of the ways in which the descriptive question can be investigated.

Systematic research specifically on argumentation within cognitive science and psychology has significantly increased over the last 10 years. Before that, there had been extensive research on reasoning conceived as an individual, internal process, much of which had been conducted using task materials such as syllogistic arguments (Dutilh Novaes 2020b). But due to what may be described as an individualist bias in cognitive science and psychology (Mercier 2018), these researchers did not draw explicit connections between their findings and the public acts of “giving and asking for reasons”. It is only somewhat recently that argumentation began to receive sustained attention from these researchers. The investigations of Hugo Mercier and colleagues (Mercier & Sperber 2017; Mercier 2018) and of Ulrike Hahn and colleagues (Hahn & Oaksford 2007; Hornikx & Hahn 2012; Collins & Hahn 2018) have been particularly influential. (See also Paglieri, Bonelli, & Felletti 2016, an edited volume containing a representative overview of research on the psychology of argumentation.) Another interesting line of research has been the study of the development of reasoning and argumentative skills in young children (Köymen, Mammen, & Tomasello 2016; Köymen & Tomasello 2020).

Mercier and Sperber defend an interactionist account of reasoning, according to which the primary function of reasoning is for social interactions, where reasons are exchanged and receivers of reasons decide whether they find them convincing—in other words, for argumentation (Mercier & Sperber 2017). They review a wealth of evidence suggesting that reasoning is rather flawed when it comes to drawing conclusions from premises in order to expand one’s knowledge. From this they conclude, on the basis of evolutionary arguments, that the function of reasoning must be a different one, indeed one that responds to features of human sociality and the need to exercise epistemic vigilance when receiving information from others. This account has inaugurated a rich research program which they have been pursuing with colleagues for over a decade now, and which has delivered some interesting results—for example, that we seem to be better at evaluating the quality of arguments proposed by others than at formulating high-quality arguments ourselves (Mercier 2018).

In the context of the Bayesian (see entry on Bayes’ theorem ) approach to reasoning that was first developed by Mike Oaksford and Nick Chater in the 1980s (Oaksford & Chater 2018), Hahn and colleagues have extended the Bayesian framework to the investigation of argumentation. They claim that Bayesian probabilities offer an accurate descriptive model of how people evaluate the strength of arguments (Hahn & Oaksford 2007) as well as a solid perspective to address normative questions pertaining to argument strength (Hahn & Oaksford 2006; Hahn & Hornikx 2016). The Bayesian approach allows for the formulation of probabilistic measures of argument strength, showing that many so-called “fallacies” may nevertheless be good arguments in the sense that they considerably raise the probability of the conclusion. For example, deductively invalid argument schemes (such as affirming the consequent (AC) and denying the antecedent (DA)) can also provide considerable support for a conclusion, depending on the contents in question. The extent to which this is the case depends primarily on the specific informational context, captured by the prior probability distribution, not on the structure of the argument. This means that some instances of, say, AC, may offer support to a conclusion while others may fail to do so (Eva & Hartmann 2018). Thus seen, Bayesian argumentation represents a significantly different approach to argumentation from those inspired by logic (e.g., argument schemes), but they are not necessarily incompatible; they may well be complementary perspectives (see also [Zenker 2013]).

Argumentation is primarily (though not exclusively) a linguistic phenomenon. Accordingly, argumentation is extensively studied in fields dedicated to the study of language, such as rhetoric, linguistics, discourse analysis, communication, and pragmatics, among others (see Eemeren, Garssen, et al. 2014: chs 8 and 9). Researchers in these areas develop general theoretical models of argumentation and investigate concrete instances of argumentation in specific domains on the basis of linguistic corpora, discourse analysis, and other methods used in the language sciences (see the edited volume Oswald, Herman, & Jacquin [2018] for a sample of the different lines of research). Overall, research on argumentation within the language sciences tends to focus primarily on concrete occurrences of arguments in a variety of domains, adopting a largely descriptive rather than normative perspective (though some of these researchers also tackle normative considerations).

Some of these analyses approach arguments and argumentation primarily as text or self-contained speeches, while others emphasize the interpersonal, communicative nature of “face-to-face” argumentation (see Eemeren, Garssen, et al. 2014: section 8.9). One prominent approach in this tradition is due to communication scholars Sally Jackson and Scott Jacobs. They have drawn on speech act theory and conversation analysis to investigate argumentation as a disagreement-relevant expansion of speech acts that, through mutually recognized reasons, allows us to manage disagreements despite the challenges they pose for communication and coordination of activities (Jackson & Jacobs 1980; Jackson 2019). Moreover, they perceive institutionalized practices of argumentation and concrete “argumentation designs”—such as for example randomized controlled trials in medicine—as interventions aimed at improving methods of disagreement management through argumentation.

Another communication scholar, Dale Hample, has further argued for the importance of approaching argumentation as an essentially interpersonal communicative activity (Hample 2006, 2018). This perspective allows for the consideration of a broader range of factors, not only the arguments themselves but also (and primarily) the people involved in those processes: their motivations, psychological processes, and emotions. It also allows for the formulation of questions pertaining to individual as well as cultural differences in argumentative styles (see section 5.3 below).

Another illuminating perspective views argumentative practices as inherently tied to broader socio-cultural contexts (Amossy 2009). The Journal of Argumentation in Context was founded in 2012 precisely to promote a contextual approach to argumentation. Once argumentation is no longer only considered in abstraction from concrete instances taking place in real-life situations, it becomes imperative to recognize that argumentation does not take place in a vacuum; typically, argumentative practices are embedded in other kinds of practices and institutions, against the background of specific socio-cultural, political structures. The method of discourse analysis is particularly suitable for a broader perspective on argumentation, as shown by the work of Ruth Amossy (2002) and Marianne Doury (2009), among others.

Argumentation is crucial in a number of specific organized social practices, in particular in politics, science, law, and education. The relevant argumentative practices are studied in each of the corresponding knowledge domains; indeed, while some general principles may govern argumentative practices across the board, some may be specific to particular applications and domains.

As already mentioned, argumentation is typically viewed as an essential component of political democratic practices, and as such it is of great interest to political scientists and political theorists (Habermas 1992 [1996]; Young 2000; Landemore 2013; Fishkin 2016; see entry on democracy ). (The term typically used in this context is “deliberation” instead of “argumentation”, but these can be viewed as roughly synonymous for our purposes.) General theories of argumentation such as pragma-dialectic and the Toulmin model can be applied to political argumentation with illuminating results (Wodak 2016; Mohammed 2016). More generally, political discourse seems to have a strong argumentative component, in particular if argumentation is understood more broadly as not only pertaining to rational discourse ( logos ) but as also including what rhetoricians refer to as pathos and ethos (Zarefsky 2014; Amossy 2018). But critics of argumentation and deliberation in political contexts also point out the limitations of the classical deliberative model (Sanders 1997; Talisse 2019).

Moreover, scientific communities seem to offer good examples of (largely) well-functioning argumentative practices. These are disciplined systems of collective epistemic activity, with tacit but widely endorsed norms for argumentative engagement for each domain (which does not mean that there are not disagreements on these very norms). The case of mathematics has already been mentioned above: practices of mathematical proof are quite naturally understood as argumentative practices (Dutilh Novaes 2020a). Furthermore, when a scientist presents a new scientific claim, it must be backed by arguments and evidence that her peers are likely to find convincing, as they follow from the application of widely agreed-upon scientific methods (Longino 1990; Weinstein 1990; Rehg 2008; see entry on the social dimensions of scientific knowledge ). Other scientists will in turn critically examine the evidence and arguments provided, and will voice objections or concerns if they find aspects of the theory to be insufficiently convincing. Thus seen, science may be viewed as a “game of giving and asking for reasons” (Zamora Bonilla 2006). Certain features of scientific argumentation seem to ensure its success: scientists see other scientists as prima facie peers, and so (typically at least) place a fair amount of trust in other scientists by default; science is based on the principle of “organized skepticism” (a term introduced by the pioneer sociologist of science Robert Merton [Merton, 1942]), which means that asking for further reasons should not be perceived as a personal attack. These are arguably aspects that distinguish argumentation in science from argumentation in other domains in virtue of these institutional factors (Mercier & Heintz 2014). But ultimately, scientists are part of society as a whole, and thus the question of how scientific and political argumentation intersect becomes particularly relevant (Kitcher 2001).

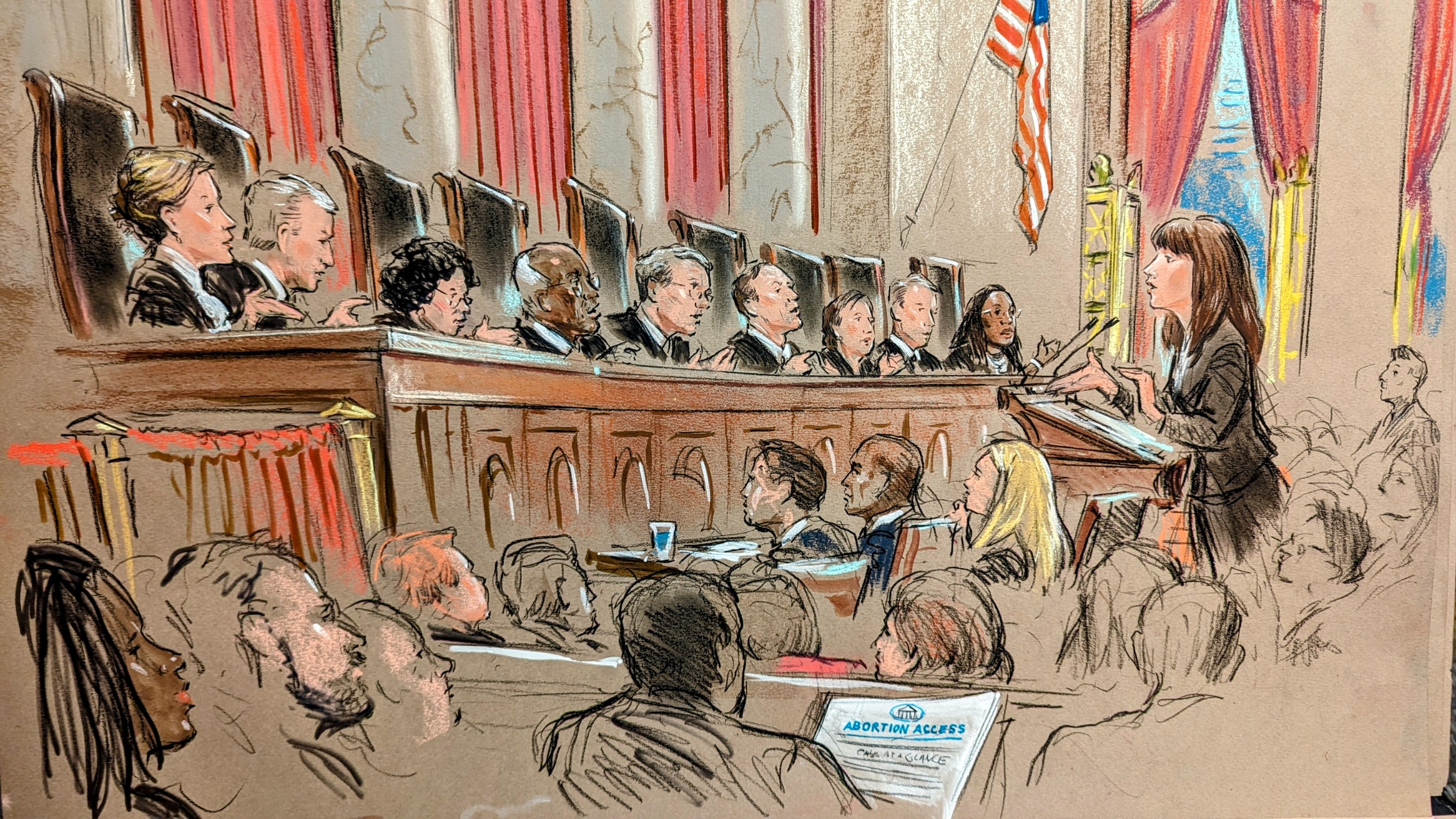

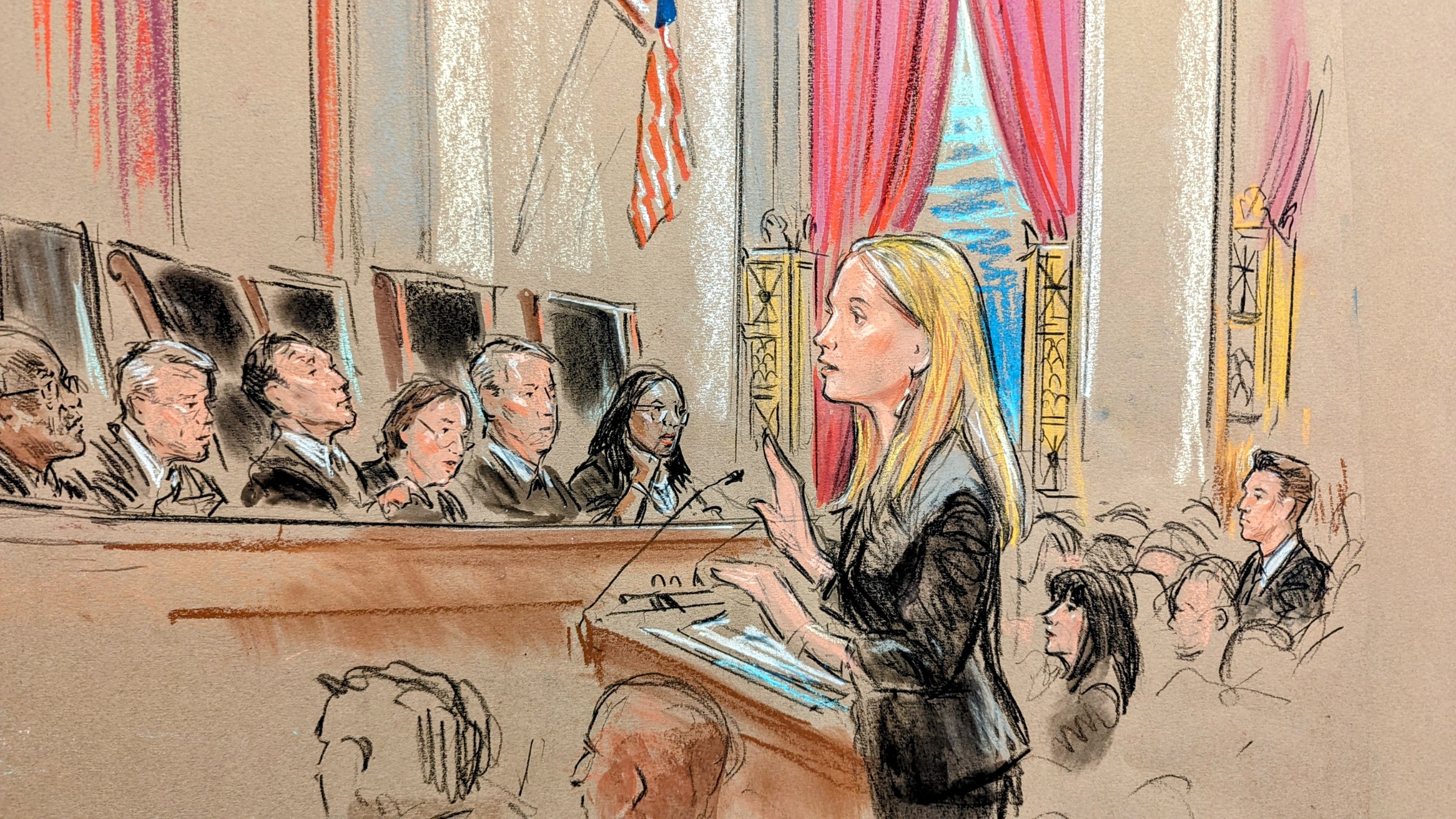

Another area where argumentation is essential is the law, which also corresponds to disciplined systems of collective activity with rules and principles for what counts as acceptable arguments and evidence. legal reasoning ).--> In litigation (in particular in adversarial justice systems), there are typically two sides disagreeing on what is lawful or just, and the basic idea is that each side will present its strongest arguments; it is the comparison between the two sets of arguments that should lead to the best judgment (Walton 2002). Legal reasoning and argumentation have been extensively studied within jurisprudence for decades, in particular since Ronald Dworkin’s (1977) and Neil MacCormick’s (1978) responses to HLA Hart’s highly influential The Concept of Law (1961). A number of other views and approaches have been developed, in particular from the perspectives of natural law theory, legal positivism, common law, and rhetoric (see Feteris 2017 for an overview). Overall, legal argumentation is characterized by extensive uses of analogies (Lamond 2014), abduction (Askeland 2020), and defeasible/non-monotonic reasoning (Bex & Verheij 2013). An interesting question is whether argumentation in law is fundamentally different from argumentation in other domains, or whether it follows the same overall canons and norms but applied to legal topics (Raz 2001).

Finally, the development of argumentative skills is arguably a fundamental aspect of (formal) education (Muller Mirza & Perret-Clermont 2009). Ideally, when presented with arguments, a learner should not simply accept what is being said at face value, but should instead reflect on the reasons offered and come to her own conclusions. Argumentation thus fosters independent, critical thinking, which is viewed as an important goal for education (Siegel 1995; see entry on critical thinking ). A number of education theorists and developmental psychologists have empirically investigated the effects of emphasizing argumentative skills in educational settings, with encouraging results (Kuhn & Crowell 2011). There has been in particular much emphasis on argumentation specifically in science education, based on the assumption that argumentation is a key component of scientific practice (as noted above); the thought is that this feature of scientific practice should be reflected in science education (Driver, Newton, & Osborne 2000; Erduran & Jiménez-Aleixandre 2007).

5. Further Topics

Argumentation is a multi-faceted phenomenon, and the literature on arguments and argumentation is massive and varied. This entry can only scratch the surface of the richness of this material, and many interesting, relevant topics must be left out for reasons of space. In this final section, a selection of topics that are likely to attract considerable interest in future research are discussed.

In recent years, the concept of epistemic injustice has received much attention among philosophers (Fricker 2007; McKinnon 2016). Epistemic injustice occurs when a person is unfairly treated qua knower on the basis of prejudices pertaining to social categories such as gender, race, class, ability etc. (see entry on feminist epistemology and philosophy of science ). One of the main categories of epistemic injustice discussed in the literature pertains to testimony and is known as testimonial injustice : this occurs when a testifier is not given a degree of credibility commensurate to their actual expertise on the relevant topic, as a result of prejudice. (Whether credibility excess is also a form of testimonial injustice is a moot point in the literature [Medina 2011].)

Since argumentation can be viewed as an important mechanism for sharing knowledge and information, i.e., as having significant epistemic import (Goldman 2004), the question arises whether there might be instances of epistemic injustice pertaining specifically to argumentation, which may be described as argumentative injustice , and which would be notably different from other recognized forms of epistemic injustice such as testimonial injustice. Bondy (Bondy 2010) presented a first articulation of the notion of argumentative injustice, modeled after Fricker’s notion of epistemic injustice and relying on a broadly epistemological conception of argumentation. However, Bondy’s analysis does not take into account some of the structural elements that have become central to the analysis of epistemic injustice since Fricker’s influential work, so it seems further discussion of epistemic injustice in argumentation is still needed. For example, in situations of disagreement, epistemic injustice can give rise to further obstacles to rational argumentation, leading to deep disagreement (Lagewaard 2021).

Moreover, as often noted by critics of adversarial approaches, argumentation can also be used as an instrument of domination and oppression used to overpower and denigrate an interlocutor (Nozick 1981), especially an interlocutor of “lower” status in the context in question (Moulton 1983; see entry on feminist approaches to argumentation ). From this perspective, it is clear that argumentation may also be used to reinforce and exacerbate injustice, inequalities and power differentials (Goodwin 2007). Given this possibility, and in response to the perennial risk of excessive aggressiveness in argumentative situations, a normative account of how argumentation ought to be conducted so as to avoid these problematic outcomes seem to be required.

One such approach is virtue argumentation theory . Drawing on virtue ethics and virtue epistemology (see entries on virtue ethics and virtue epistemology ), virtue argumentation theory seeks to theorize how to argue well in terms of the dispositions and character of arguers rather than, for example, in terms of properties of arguments considered in abstraction from arguers (Aberdein & Cohen 2016). Some of the argumentative virtues identified in the literature are: willingness to listen to others (Cohen 2019), willingness to take a novel viewpoint seriously (Kwong 2016), humility (Kidd 2016), and open-mindedness (Tanesini 2020).

By the same token, defective argumentation is conceptualized not (only) in terms of structural properties of arguments (e.g., fallacious argument patterns), but in terms of the vices displayed by arguers such as arrogance and narrow-mindedness, among others (Aberdein 2016). Virtue argumentation theory now constitutes a vibrant research program, as attested by a special issue of Topoi dedicated to the topic (see [Aberdein & Cohen 2016] for its Introduction). It allows for a reconceptualization of classical themes within argumentation theory while also promising to provide concrete recommendations on how to argue better. Whether it can fully counter the risk of epistemic injustice and oppressive uses of argumentation is however debatable, at least as long as broader structural factors related to power dynamics are not sufficiently taken into account (Kukla 2014).

On some idealized construals, argumentation is conceived as a purely rational, emotionless endeavor. But the strong connection between argumentative activities and emotional responses has also long been recognized (in particular in rhetorical analyses of argumentation), and more recently has become the object of extensive research (Walton 1992; Gilbert 2004; Hample 2006: ch. 5). Importantly, the recognition of a role for emotions in argumentation does not entail a complete rejection of the “rationality” of argumentation; rather, it is based on the rejection of a strict dichotomy between reason and emotion (see entry on emotion ), and on a more encompassing conception of argumentation as a multi-layered human activity.